In this section, we present the results from the questionnaire data and the semi-structured interviews about participants’ beliefs and desires regarding learning Darija as they began their SA in Morocco. Overall findings from questionnaires found that learners evaluated Moroccan Arabic highly in terms of wanting to learn and expecting to learn the variety. Furthermore, learners rated positive ideologies about Darija highly and negative ideologies low. Their positive evaluations of Darija in the questionnaire data were also reflected in the interviews, as learners disagreed with negative ideas about Darija and described a new desire to learn it. Analysis of questionnaire and interview data together, therefore, shows that learners began SA with positive views towards Moroccan Arabic and show shifting beliefs and increasing sociolinguistic competence.

4.1. Questionnaire Data

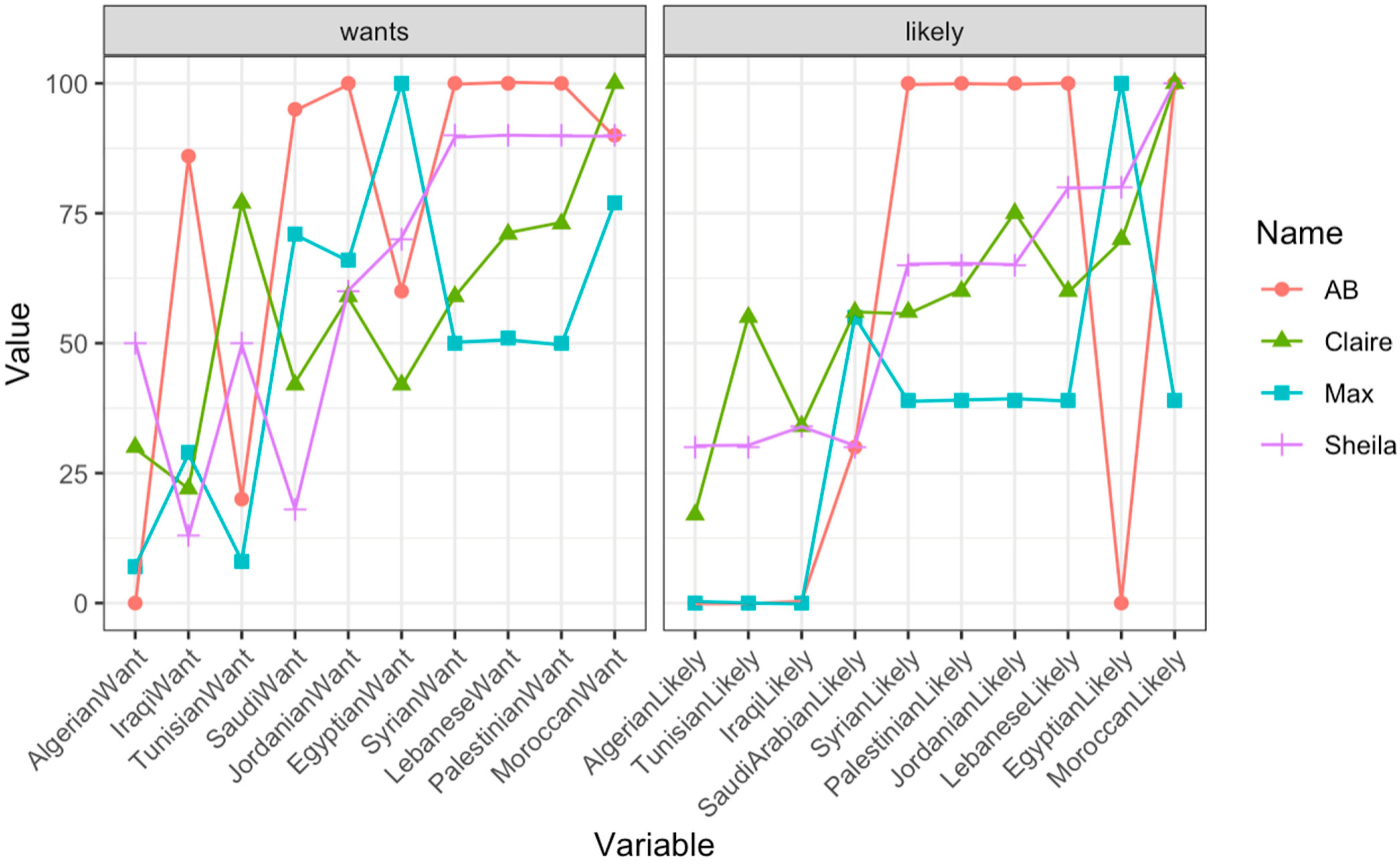

Data presented in

Figure 1 show participants’ responses to two sets of questions. First, they were asked to rate from 0–100 how much they wanted to learn to communicate in the 10 dialects in

Figure 1. Then they were asked to rate how likely they were to learn to communicate in the same dialects. Data below are organized to show responses ranging from lowest to highest based on the median of participants’ ratings. Dialects were originally presented in alphabetical order.

The responses to wanting to learn a dialect showed the lowest evaluations were given to Algerian, Iraqi, Tunisian, and Saudi. The highest responses were for Syrian, Lebanese, Palestinian, and Moroccan, with Moroccan being the highest (all ratings over 75). Egyptian was classified as a moderate response. Although evaluations to “wanting to learn a dialect” scales were relatively similar to the likeliness evaluations, participants evaluated Egyptian (as opposed to Levantine) higher. Moroccan was rated as 100 by AB, Claire, and Sheila. Throughout the data as a whole, AB evaluated both want and likely highly. Max, on the other hand, evaluated them more conservatively. Numeric data are available in

Appendix A.

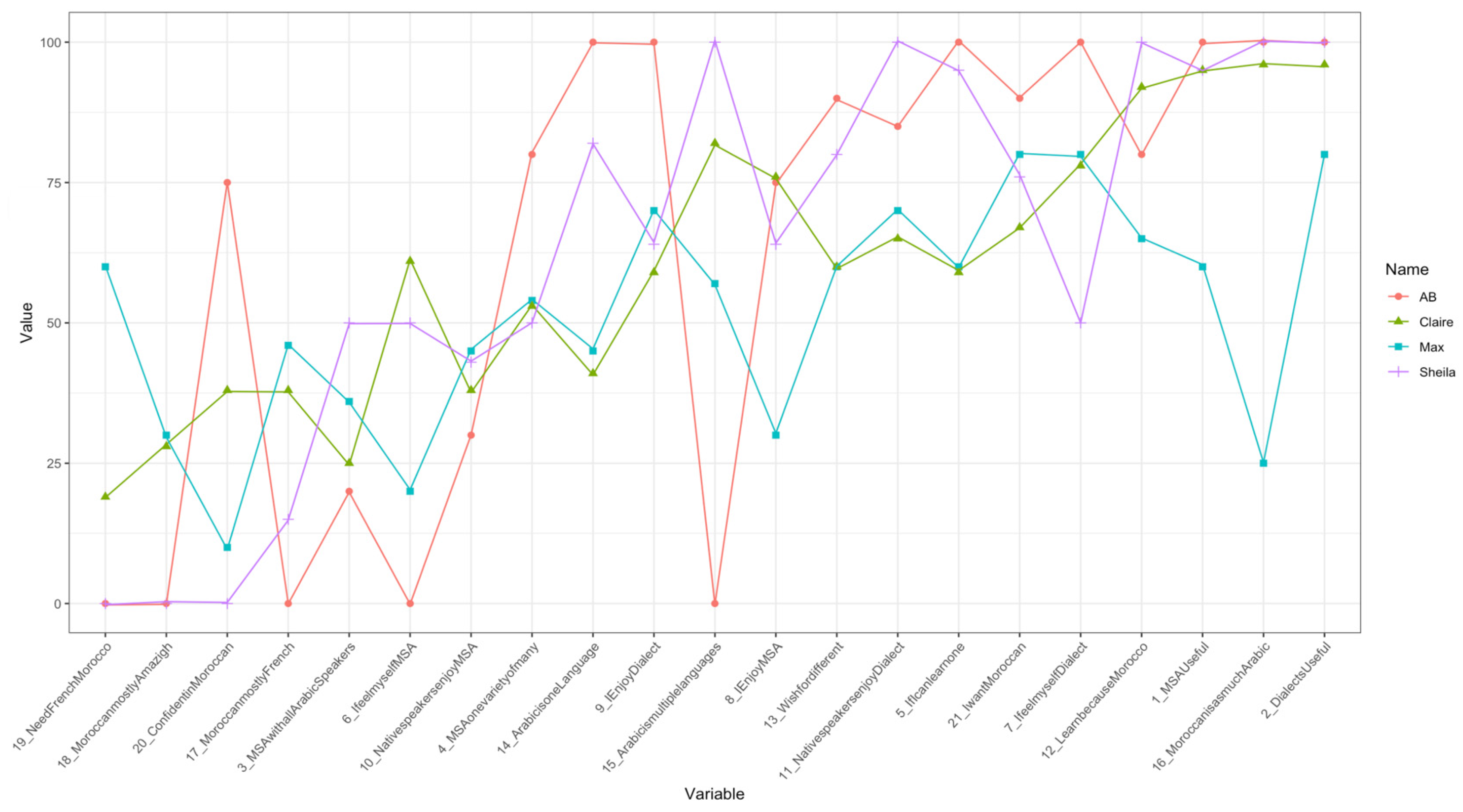

As for beliefs, students were asked to respond to 21 scales with ratings from 0–100. The 21 statements are presented in a table in

Appendix C. Reference to each statement is made through the number found in the table. For example, the statement “Modern Standard Arabic is useful” is listed first and with “1.” Therefore, each number found in

Appendix C and

Figure 2 below corresponds to one of the 21 belief statements listed in the table. For visualization, we present participants’ responses below organized from lowest to highest ratings based on the median values in

Figure 2. Participant responses varied extensively throughout the scales, but general results show the lowest evaluations for statements 17, 18, 19, and 20. Three of these statements corresponded to statements of Moroccan Arabic being mostly French / Amazigh or that French was needed to live in Morocco. The overall lowest evaluation was given to statement 19: “I need to know French to live in Morocco”. Claire, Sheila, and AB gave this a rating below 25, however, Max was an outlier with an evaluation well above 50.

Positive evaluations were given to statements 12, 1, 16, and 2. Statement 12 relates to a desire to learn Darija because of SA in Morocco, while statements 1 and 2 address the usefulness of MSA and Dialects. Looking at the total numeric data found in

Appendix B, median values for statements 16 and 2 were tied at 98. Statement 16 says, “The Moroccan dialect is as much an Arabic dialect as Levantine, Egyptian, or any other regional variety.” AB, Sheila, and Claire gave this a near 100 score. However, Max rated this significantly lower at 25.

Final data from the questionnaire come from participants’ responses to an open-ended statement: “I believe Moroccan Arabic is…” Participants had varying responses. Generally, responses were brief, but the analysis of these statements reveals interesting aspects related to general themes found in the interviews and other questionnaire data. AB’s response described Darija as a “rich” dialect, highlighting how it is mixed with many “influences.” Claire was very concise, stating it is “difficult but useful.” Sheila provided a more negative view, stating that it was “hard to understand” or “communicate with other native Arabic speakers.” Finally, Max made a noteworthy statement as he claimed Moroccan Arabic was “essentially its own language (s).” Therefore, in these brief statements, participants are seen describing Moroccan Arabic in substantially different ways, ranging from a dialect of Arabic to a completely new language or set of languages.

4.2. Semi-Structured Interviews

Analysis of semi-structured interviews found a shift in learners’ attitudes toward learning Darija due to the immediate need of SA in Morocco. Participants were also found to explicitly reject the negative beliefs they previously had due to their lack of experience with Darija or due to what others (professors, fellow students, Arabic speakers) had said about it. Below, we provide some representative excerpts from each participant.

4.2.1. Sheila

Sheila had studied Arabic the longest of all the participants (eight years and 10 months). She began learning Arabic during middle school when she viewed the opportunity to study it as a “once-in-a-lifetime opportunity.” Her ability to study Arabic during her undergraduate studies was a deciding factor in her university choice, but she still claimed that she did not “need” Arabic. She had studied abroad in Jordan previously, but reported facing fatigue due to the program’s language pledge, leading her to take a year off from formal study before this SA sojourn. She described Arabic learning as a journey that requires learners to be confident in themselves. Sheila reported studying under professors from many different backgrounds, for example, Jordanians, Lebanese, Palestinians, Syrians, and Yemenis. She self-evaluated as advanced in MSA and intermediate in Levantine and listed beginner for North African and Egyptian.

In response to the question, “Before you came to Morocco or this SA experience, did you want to study Moroccan Arabic?” in Excerpt 1 below, Sheila immediately said, “Oh no” (line 4). Continuing, she explained her reluctance as due to most people saying, “It’s so different.” She quoted this in a mimicking deep tone while waving her hands in the air. Furthermore, she explained that L1 Arabic speakers said that they cannot understand Moroccans.

Excerpt 1: Sheila shares her views of Darija before SA.

| 1 | INT | Before you came to Morocco or |

| 2 | | this study abroad experience |

| 3 | | did you wanna study Moroccan Arabic |

| 4 | SH | Oh no - |

| 5 | INT | Why or why not |

| 6 | SH | Ummm (.) no (.) I was scared of it |

| Lines 6–14 omitted |

| 15 | INT | yeah |

| 16 | SH | So I was like |

| 17 | | yeah |

| 18 | | Well that kind of sucks hhhhh ummmhhhh |

| 19 | | Whyyy dooo I |

| 20 | | but yeah, |

| 21 | | So (.) no I did not |

However, as Excerpt 2 shows, beginning the SA experience and after a short period traveling in Morocco, she opposed L1 Arabic speakers’ comments, emphasizing that Darija is “not thaat different” (line 5). She then disagreed with herself immediately, saying, “It is really different” (line 6). Concluding her comments, Sheila stated that the things that are really different are some “daily stuff,” which is similar to differences in Levantine and Egyptian, but the “cherry on the top” is the pronunciation and use of French (lines 7–24). However, she remarked that this experience had already helped her understand Moroccans better and given her a “more versatile … ear to Arabic” (lines 28–39).

Excerpt 2: Sheila explains her shifting views of Darija.

| 1 | INT | how do you feel now |

| 2 | SH | Iii (1) feel (2)((chewing gum)) |

| 3 | | I feel things shifting [a lit]tle bit |

| 4 | INT | [mmmm] |

| 5 | SH | Because (.) to be honest it’s not thaat different |

| 6 | | It is very different like there’s a lot of like |

| 7 | | daily life words |

| 8 | INT | yeahh |

| 9 | SH | but that’s common in most |

| 10 | | like lahajaat ((dialects)) |

| 11 | INT | mhm |

| 12 | SH | You know like fuc- ((trying to find word)) dialects |

| 13 | INT | dialects yeah |

| 14 | SH | umm tsa Umm Like whether it’s um in |

| 15 | | the Levant or you know Egypt or |

| 16 | | wherever like there’s |

| 17 | | a lot of just like |

| 18 | | daily stuff thats thats re(h)ally really |

| 19 | INT | [mhm] |

| 20 | SH | different um. It’s just |

| 21 | | the pronunciation really that |

| 22 | | mak[es] kind of puts the |

| 23 | INT | [yeah] |

| 24 | SH | the cherry on top and the use of French |

| 25 | | and stuff but .hhh I like the fact I do like |

| 26 | | the fact that I can better understand Moroccans- |

| 27 | INT | -ye[ah] |

| 28 | SH | [Now] it feels like I have a little bit more |

| 29 | | versatile of an ear to Arabic |

4.2.2. Max

Max was also an advanced MSA learner who self-evaluated as advanced in MSA, intermediate in Egyptian, and a beginner in North African and Levantine. When asked to report any languages considered a first language or mother tongue, Max wrote that he was a “highly fluent” speaker of Spanish as a second language and that French was his third language. He was the only participant to report an additional language on this question. Max described his experience as starting very well. He had studied abroad previously in Jordan and completed a summer program at the same center in Morocco two years prior. Max was seen as a very outgoing and strategic language learner. He frequently discussed his previous experiences studying romance languages (French and Spanish) and compared those to his experience with Arabic. Furthermore, he often suggested big claims about the nature of language and spoke with a sense of established knowledge based on his experience. He regarded his extroversion as fitting with Arabic society, which allowed him to thrive. Max reported only studying under Egyptian and L2 Arabic-speaking professors.

During the interview (Excerpts 3 and 4), as with the other participants, Max was asked if he wanted to study Moroccan Arabic before this SA experience. He quickly started answering by describing what he called “my philosophy.” He described how he started with Shaami (which he found the easiest) before switching to Masri two years ago because this would allow him to be understood more easily, considering that Masri is “the most understood version” and “of course with Darija that is not really the case” (lines 1–9).

Excerpt 3: Why Max did not want to study Darija.

| 1 | Max | and so I I chose masri because i was like |

| 2 | | you know what if I’m gonna mess up little things |

| 3 | INT | mhm |

| 4 | Max | I wanna be |

| 5 | | attempting to say the most |

| 6 | | understood version ((Moves hands apart in front of him)) |

| 7 | INT | okay gotcha |

| 8 | Max | uhh and of course with darija |

| 9 | | that’s [not really] the case |

Two summers before, Max was a student in the summer program at the same institution. Max shared that he enjoyed the Darija class previously and even thought, “If I come back and do Capstone, that’s something I really want to get the opportunity to study.” Stating his reasoning for wanting to learn Darija, he associated dialects to his learning of other languages, saying, “For whatever reason, dialect, I just find like it almost makes sense more in the way that romance languages did for me” (lines 1 & 2). Max frequently compared his experience learning Arabic to his time learning French and Spanish. Discussing his learning of Darija and his changing desire to learn it, he shared, “I don’t know how true this is at all, but I was hoping that speaking French and Spanish would help sort of accelerate it a little bit” (line 12–15). Yet, he ended by saying that it is maybe at the lexical level, but “not as much with the grammar or anything.” (lines 18–22). He concluded that the deciding factor in his learning of Darija was “just the practicality of speaking here” (lines 23 & 24), and that “it would be nice to to be able to speak the local dialect well” (lines 31 & 32). Excerpt 4 below displays this interaction and shows how Max’s desire to learn Darija changed.

Excerpt 4: Max explains how his desire to learn Darija changed.

| 1 | Max | for whatever reason dialect I just find |

| 2 | | like it almost makes sense [more] |

| 3 | Int | [yeah] |

| 4 | Max | in the way that romance languages did for me |

| 5 | | and so that’s a little bit more |

| 6 | | even when it’s unfamiliar it feels more familiar |

| 7 | Int | mhmm |

| 8 | Max | and uhhhh so I really like that |

| 9 | | And then you know |

| 10 | | knowing that i’d be here for a while |

| 11 | Int | yeah |

| 12 | Max | of course piques the interest |

| 13 | | And I don’t know how true this is at all |

| 14 | | but I was hoping that speaking French |

| 15 | | and Spanish would help sort of accelerate it= |

| 16 | Int | =yeahh= |

| 17 | Max | #NAME? |

| 18 | | Whi[ch it] |

| 19 | Int | [maybe] |

| 20 | Max | certain vocab words |

| 21 | Int | mhm |

| 22 | Max | not as much with the grammar or anything like that |

| 23 | | But uhhh yeah I would say just the |

| 24 | | practicality of speaking it here |

| 25 | Int | mhm |

| 26 | Max | Because (1) people tend to |

| 27 | | understand masri oka[yyy] and obviously I’m not |

| 28 | Int | [yeah] |

| 29 | Max | perfect at speaking it hhh by any means |

| 30 | Int | For sure yeah |

| 31 | Max | uhhh but it would be nice to |

| 32 | | to be able to speak the local dialect well |

| 33 | Int | mmm yeahh |

| 34 | Max | I’d say that’s probably the biggest reason |

4.2.3. Claire

As with other participants, Claire had studied abroad previously for what she described as “long periods of time.” Nevertheless, she said it was still hard to come to a new place and described a mix of excitement and anxiety. In her self-report on official OPI scores, she listed three different scores, but it is assumed that her highest score (Advanced Low) would be the most recent. In general, Claire was noticed often doubting her abilities in Arabic with remarks about learning things late or not understanding frequently. Claire had studied with professors from Egypt, Jordan, Lebanon, Syria, and L2 Arabic speakers.

As can be seen in Excerpt 5 below, for Claire, learning Darija was something that she “put off” (line 14). She stated that she did not know much about the dialects when she started learning Arabic. However, she described how she thought learning Darija “would happen somewhere along the line” but that “it seemed like Shaami dialect was more useful to [her], or [her] interest in the region” (lines 5–10). Progressing, in lines 16- 23, Claire said, “There is already kind of a joke about it…the joke that it’s like the not useful, um or the harder to learn one.”

Excerpt 5. Claire explains why she did not want to learn Darija initially.

| 1 | C | Okay so back when I first decided to learn Arabic |

| 2 | | I didn’t really know much about the |

| 3 | | dialects |

| 4 | INT | mhm |

| 5 | C | umm and then after that (3) |

| 6 | | it wasn’t necessarily an aversion to learning Moroccan |

| 7 | | Arabic it was just always |

| 8 | | this is going to happen somewhere along the line |

| 9 | INT | yeahh |

| 10 | C | and it seemed like shaami dialect was more uu:se[ful] to me |

| 11 | INT | [mhm] |

| 12 | C | or like my interest in like the region |

| 13 | INT | yeahh |

| 14 | C | umm (.) So I kind of I guess put off learning Darija |

| 15 | INT | yeahh |

| 16 | C | and then it kind of you |

| 17 | | know there’s already kind of a joke |

| 18 | | about it which I guess is part of ( ). |

| 19 | | Anyways |

| 20 | INT | yeahh hh[hhh] |

| 21 | INT | [theres kind] of a joke |

| 22 | C | that it’s like the not as useful ((hands with air quotes)) |

| 23 | | um or harder to learn one |

Excerpt 6 shows how Claire continued her reflection on learning Darija (line 1). She discussed how the experience was interesting because she was able to pick out where words are similar between other dialects and languages. Specifically, she reported finding words that were similar to the Khaliji ((Gulf)) dialect, although someone (unspecified) keeps saying they are not (line 8). After these comments, Claire was asked when she noticed her views changing, and she stated that it was during a class she took to prepare to come to Morocco.

Excerpt 6: Claire explains her shift in the desire to learn Darija.

| 1 | Claire | umm I feel like learning has been really interesting |

| 2 | | because you can pick out where words are similar |

| 3 | INT | mmm |

| 4 | Claire | And there are words that |

| 5 | | are similar to the Kh- Khaliiji dialect th[at I’ve he]ard |

| 6 | INT | [Yeahh] |

| 7 | | Oh really= |

| 8 | Claire | =but keep saying they’re not |

| 9 | | but whatever |

Moreover, Claire explained that she viewed “knowing Darija as very useful” at the beginning of her SA. Explaining why, she added, “especially, because from my experience with people who know Darija [they] can switch between dialects a lot easier,” plus it gives them the ability “to understand what’s happening.” She ended by arguing that “the assumptions or stereotype that it’s not useful comes from the stereotype that it’s so crazy different ((said with a sarcastic tone and quoting hands)) from MSA or other dialects, that nobody will use it and if you speak it people won’t understand you. Which I don’t necessarily think is true. I think that is more of a stereotype.”

4.2.4. AB

AB was an advanced Arabic speaker who evaluated himself as advanced in both MSA and Levantine. He discussed his familiarity with being in a SA experience, as he had studied abroad in Jordan, while also experiencing culture shock. He reported having experience with Arabic professors from different backgrounds, including Egyptian, Lebanese, and Non-Arab. When discussing his identity, he spoke about being a white man (although he stated that it was “such a small thing”) and his identity as a Christian. Each of these aspects was described as affecting his Arabic. AB was also married, and his wife joined him during his SA in Morocco, but she did not speak Arabic. AB reported having to act as a translator with their host family.

AB was the only participant who stated that learners should begin with MSA and dialect at the same time. When answering whether he wanted to learn Darija before studying abroad, he stated that his program only used MSA, and that he had a lot of “misconceptions” coming from “stereotypes” surrounding Darija and what it’s made up of”. When asked directly what the misconceptions that he previously mentioned were, AB first described them as “in the Arab world … there’s common misconceptions that like its oh its basically you know. Just like a big hodgepodge of you know Tamazight and Fransi ((French)) and Arabic you know just all jumbled together”. However, he quickly refuted these thoughts, saying, “and it’s just not how it is.” Conceding slightly, “like certainly there are aspects of of French language… and certain words from Tamazight that make their way… in.”

When answering whether he wanted to learn Darija, knowing that he was going to SA in Morocco, AB explained that “Darija was going to be part of my life” for his year abroad and maybe in the long run as well. Finally, trying to understand how he stopped having those misconceptions, he was asked when he noticed them changing. He responded by saying it was when he “started taking Darija for the first time” and he was “shocked with how easy it was to get started.”