5.1. A Few Considerations on the Uses of já and mais

As was mentioned before, jamais results from the frequent combination of two different adverbs inherited from Latin: já ‘now/already’ (<iam Lat.), a temporal–aspectual adverb, and mais ‘more’ (<magis Lat.), an intensity adverb.

In early texts, these two items occurred in multiple contexts (negative, modal or affirmative) and independently from one another. They were both preserved in the language until nowadays, along with the negative temporal adverb jamais.

The adverb

já ‘now/already’ had a larger spectrum of occurrence in earlier stages. Examples (8) to (11) illustrate its use in association with other adverbs, as a sort of reinforcement strategy, with aspectual reading.

| (8) | Mas, | pois | ja | assi | he | que | elles |

| | but | then | now | this.way | be.3sg.Pres | that | they |

| | saben | per | vos | o | que | lhe | eu |

| | know.3pl.Pres | by | you.2pl | the | what | him.3sg.dat | I |

| | queria | dizer […] | | | | |

| | want.1sg.Imp | say | | | | | |

| | ‘But, they already know from you what I wanted to tell them.’ |

| | (Pedrosa, 2012 & Miranda, 2013, Crónica Geral de Espanha, 14th cent.) |

| (9) | […] | e | quero | ja | sempre | servuir | a | Deos | por |

| | […] | and | want.1sg.Pres | now | always | serve | to | God | by |

| | elles | e | por | mỹ. | | | | |

| | they | and | by | me | | | | |

| | ‘and I want to serve God forever, for them and for me.’ |

| | (Toledo Neto, 2012–2015, Demanda do Santo Graal, 13th cent.) |

| (10) | Ca, | como | quer | que | o | filho | de | Deus |

| | because | how | want | that | the | son | of | God |

| | resurgisse | da | morte | aa | vida | e | ja | nunca |

| | return.3sg.Imp.Subj | of.the | death | to.the | life | and | now | never |

| | possa | morrer | | | | | | |

| | can | die | | | | | | |

| | ‘Because, however the son of God came back to life and he can never die.’ |

| | (A. F. Machado, 2013, Diálogos de São Gregório, 14th cent.) |

| (11) | […] | quando | os | nossos | chegarão | jaa | nõ |

| | […] | when | the | ours | arrive.3pl.Past | now | neg |

| | poderão | allcãçar | senã | seys | mouros | | |

| | could.3pl.Past | reach | except | six | moors | | |

| | ‘[…] when ours arrived, they could no longer reach more than six moors.’ |

| | (Brocardo, 1997, Crónica do Conde Dom Pedro de Menezes, 15th cent.) |

The examples above illustrate the frequent association of já with the adverbs assim ‘this way’, sempre ‘always’ and nunca ‘never’ and with the standard sentential negation marker não ‘no’ (as an inchoative strategy). Apart from these adverbs, já also occurred associated with other elements, in the expressions já quanto ‘a little’, já quê ‘a bit/anything’, já que quer ‘something’, among others. These occurrences of já with quanto, quê and que quer are no longer possible in contemporary Portuguese.

As for the adverb

mais ‘more’, apart from the uses in comparative clauses, it was also registered in association with

nunca ‘never’, as in (12), but also as a Verbal Phrase (VP) modifier, in negative sentences with the standard negation marker

não ‘no’, as in (13). In both contexts, it worked as an intensifier. Both occurrences remain possible in contemporary Portuguese.

| (12) | E | assi | o | levárão | pera | sua | casa, |

| | and | this.way | him.3sg.acc | take.3pl.Past | to | his | house |

| | que | nunca | mais | abrio | os | olhos | nem |

| | that | never | more | open.3sg.Past | the | eyes | nor |

| | moveo | pee | nem | mão. | | | |

| | move.3sg.Past | foot | nor | hand | | | |

| | ‘And therefore, they took him home, since he never again opened his eyes nor moved a foot nor a hand.’ |

| | (Castro, 1984, José de Arimateia, 13th cent.) |

| (13) | -Na | demanda, | disse | o | caualeyro, | nom | uos |

| | in.the | quest | say.3sg.Past | the | knight | neg | you.2pl.reflx |

| | metades | mais | […] | | | | |

| | put.2pl.Pres-Subj | more | | | | | |

| | ‘In the quest, said the knight, do not involve yourself anymore.’ |

| | (Toledo Neto, 2012–2015, Demanda do Santo Graal, 13th cent.) |

In early texts, the co-occurrence of both

ja and

mais in the same sentence was frequent and seemed to be a reinforcement strategy to express the continuation or end of a state of events, with a defined starting point. By combining the aspectual feature of

ja with the intensity/reinforcement conveyed by

mais, the interpretation of the sequence

ja mais7 would literally be ‘from now on… more’. In sentence (14), for example,

já sets the moment from which an event (

auera honrra ‘to have honour’) will no longer repeat itself.

| (14) | […] | e | disse | que | jamais | nõ | auera | honrra | |

| | […] | and | say.3sg-Past | that | now.more | neg | will.have | honour | |

| | ‘and he said that from that moment on he will have no more honour’ |

| | (Toledo Neto, 2012–2015, Demanda do Santo Graal, 13th cent.) |

The combination of

ja with

mais does not seem any different from the combination of

já with other adverbs. However, this is the only combination that will acquire the status of a construction and, in due course, of an independent lexical unit.

8It should be noted that the two adverbs can still co-occur in the same sentence, but, in such cases, they are associated with negation and to the combination of inchoative and comparative strategies (as in

van der Auwera, 1998).

5.2. Jamais and Its Relation with Polarity

In the previous section, it became clear that both adverbs já and mais could occur in any context alone, without polarity constraints. However, when we look at the construction ja mais, we see that polarity plays an important role in its behaviour and interpretation.

Let us first start by looking at the distribution of the 321 examples found in our corpus, in terms of the polarity context in which jamais appears.

Table 2 clearly shows that there is a predominance of examples of

jamais in the 13th century (as mentioned in the introduction), when compared to the following centuries. In fact, the frequency found in the 13th century drops drastically in the 14th century data and is residual in the next two centuries. This may be due to text typology, but it does not fully explain the scarcity of cases of

jamais from the 14th century onwards. We can hypothesize that two other factors may have influenced this outcome: i) the progressive disappearance of

jamais from affirmative and modal contexts narrowed down its occurrence to negative sentences only; ii) after the 15th century

jamais will become intrinsically negative, facing competition from

nunca, which was already a strong NPI in the 13th century.

Another particularity of the data collected is related to the strong association of

jamais with negative contexts. These are the most frequent contexts of occurrence of

jamais in all centuries, even in the earlier attestations. Despite that, and contrary to contemporary data,

jamais was actually found in all polarity contexts, as exemplified from (15) to (17), where we find

jamais in modal, affirmative–assertive and negative contexts, respectively.

| (15) | cujdades | uos | que | jamais | eu | possa |

| | think.2pl.Pres | you.2pl | that | now.more | I | can |

| | ueer | a | companha | da | messa | terreal |

| | see | the | company | of.the | table | earthly |

| | redõda | assi | asuada | como | uy | em |

| | round | this.way | reunited | as | see.1sg.Past | in |

| | dia | de | Pitecostes? | | | |

| | day | of | Pentecost | | | |

| | ‘Do you believe that I will ever see again the company of the round table reunited just like I did on Pentecost day?’ |

| | (Toledo Neto, 2012–2015, Demanda do Santo Graal, 13th cent.) |

| (16) | Mais | sempre | seiã | firmes | e | estaues | pera | sempre |

| | But | always | be.3pl.Pres-Sub | firm | and | stable | for | always |

| | ia | mays. | | | | | | |

| | now | more | | | | | | |

| | ‘But always be firm and stable for ever and ever.’ |

| | (Xavier, n.d., Corpus CIPM, Documentos da Chancelaria de Afonso II, 13th cent.) |

| (17) | Vem | aca | amíga | que | jamais | nom | sofrerás |

| | come.2sg.Imp | here | friend | that | now.more | neg | suffer.2sg.Fut |

| | desta | pena. | | | | | |

| | of.this | punishment | | | | | |

| | ‘Come here friend, as you will never suffer such punishment’ |

| | (Xavier, n.d., Corpus CIPM, Vidas de Santos, 14th cent.) |

I start by looking at example (15), which is not possible in contemporary Portuguese, but is still attested in Spanish (cf.

Arboleas et al., 2020, p. 82).

In (15),

jamais is in the scope of an interrogative clause,

9 which is considered a modal (or nonveridical) context capable of licensing weak NPIs and modal polarity items (MPIs). As the term suggests, MPIs are only licensed in modal contexts.

The meaning conveyed by

jamais in such cases is equivalent to ‘ever’. There are only 15 examples of

jamais in a modal context with existential interpretation, the majority found in texts from the 13th century.

10 They all correspond to contexts that have been identified as licensers of weak NPIs in Old Portuguese (cf.

Martins, 2000;

Pinto, 2021,

2024), with interrogative, completive and conditional clauses being the most frequent cases.

Contexts as the one in (15) also occur with the MPI

nunca ‘never’ in Old Portuguese. According to

Pinto (

2024), the MPI

nunca was licensed in modal contexts and had an ‘ever’ reading, but it disappeared from the language, being replaced by the expression

alguma vez ‘any time/ever’. If we compare the use of

jamais in (15) with

nunca in (18), we see that the interpretation is equivalent. In fact, none of the 15 modal contexts displays

jamais co-occurring with the MPI

nunca, which suggests that they competed for the same function in such cases (but this is not true in negative contexts until

jamais becomes a strong NPI).

| (18) | Quẽ | crerya | nuca | a | mỹ | sẽ |

| | who | believe.3sg.Cond | never | to | me | without |

| | testemoynha | de | Jhesu | Christo, | se | eu |

| | witness | of | Jesus | Christ | if | I |

| | quisesse | dizer | que | as | espinhas | eră |

| | want.1sg.Pres.Sub | say | that | the | fishbones | be.3pl.Imp |

| | riquezas | | | | | |

| | riches | | | | | |

| | ‘Who would ever believe me without a Christian witness if I wanted to say that the fishbones were riches? |

| | (A. F. Machado, 2013, Diálogos de São Gregório, 14th cent.) |

Against expectations, jamais only appears once in a superlative construction. Given its marginal acceptance in such contexts in Contemporary Portuguese, we would expect to find more occurrences of jamais with an existential reading in a superlative clause. Nevertheless, the overall number of modal contexts is low, so we cannot draw solid conclusions from here.

On the other hand, example (16) presents

jamais co-occurring with the adverb

sempre ‘always’, in an affirmative–assertive context. In Contemporary Portuguese, the sequence ‘sempre jamais’ is no longer possible since these two items—

jamais and

sempre—are semantically incompatible, conveying opposite temporal interpretations. There are 34 examples of

jamais in an affirmative–assertive context in the corpus. Twenty-five of those examples present

jamais in association with

sempre ‘always’, usually in the expression

para (todo) sempre jamais ‘for ever and ever’. This indicates that, not only was

jamais used as a reinforcement strategy of the temporal adverb

sempre, but it was also empty from its contemporary negative semantics associated with ‘no point in time’. In fact, in the remaining nine examples,

jamais occurs in the Prepositional Phrase (PP)

por jamais ‘forever’, displaying the exact same meaning of

sempre ‘always’, as illustrated in (19):

| (19) | […] | et | cum | Judas | otraedor | de | nostro | Senor |

| | […] | and | with | Judas | the.traitor | of | our | Lord |

| | seya | danado | por | ja | mays | no | Infferno | |

| | be.3sg.Pres-Sub | condemned | of | now | more | in.the | hell | |

| | ‘and along with Judas, our Lord’s traitor, may he be condemned forever to hell’ |

| | (Barreiro, 2006–2018, Corpus Xelmírez, 14th cent.) |

In all of these cases, jamais has a purely temporal–aspectual interpretation, being equivalent to ‘forever’ when it occurs in the PP por jamais, or reinforcing the adverb sempre ‘forever’, in para sempre jamais. It should also be noted that, contrary to modal and negative contexts, where jamais appears as the head of an adverbial phrase, in affirmative–assertive contexts, it never occurs on its own. It is always registered as an adverbial inside a PP.

Similar to what happens with

jamais in modal contexts, occurrences of

jamais meaning ‘forever’ in similar expressions are also attested for Old Spanish

jamás (cf.

Rueda Rueda, 1997) and Old French

jamais (cf.

Hansen, 2012). For Old Spanish we find the PP

por jamás, but, contrary to Portuguese data, the use of

jamás alone as an adverbial adjunct is also registered as in the example

[m]i vida será jamás amarga ‘my life will always be bitter’ (cf.

Rueda Rueda, 1997, p. 129, ft. 20). Also,

Hansen (

2012, p. 82) notes the existence of a frozen expression

à/pour jamais with the same meaning of the Portuguese and Spanish counterparts.

The fact that at least these three languages presented a positive item jamais meaning sempre is an argument in favour of the non-negative initial semantics of the construction. It also makes its appearance in a very early stage of Romance languages.

Finally, example (17) shows jamais in a negative context. In such cases, jamais co-occurs with a negative element: the sentential negation marker não ‘no’, the strong NPI nunca ‘never’ or the negative conjunction nem ‘nor’, but in a residual number. There are no occurrences of jamais with a negative indefinite (such as nenhum, ninguém or nada) in negative sentences, which is expected, since these items were not intrinsically negative in early stages and could not convey negation on their own. They were always accompanied by a negative element.

The occurrence of

jamais with the sentential negation marker

não ‘no’ is the default pattern in negative sentences and it is still possible nowadays, when

jamais is postverbal. However, the association of

jamais with

nunca is not productive in contemporary data and is considered marginal or ungrammatical. In contrast,

nunca is present in 24% of the negative sentences with

jamais in the corpus. In these cases,

nunca is the only negative element in the sentence, responsible for sentential negation. Contrary to what we have seen in the combination of

jamais with the adverb

sempre, the word order between the two items is flexible. We find both orders,

nunca jamais and

jamais nunca, and also cases where the two adverbs are not in adjacency. These three scenarios are illustrated in (20) to (22), respectively.

| (20) | -Se | em | esta | lide | entrarmos, | nunca | jamais |

| | -if | in | this | fight | go.in.2pl.Fut.Subj | never | now.more |

| | tornaremos | a | Castella. | | | | |

| | go.back.2pl.Fut | to | Castella | | | | |

| | ‘- If we go into this fight, we will never get back to Castella again.’ |

| | (Pedrosa, 2012 & Miranda, 2013, Crónica Geral de Espanha, 14th cent.) |

| (21) | Jamais | nuca | s(er)am | corrutos | nẽ | desenparados |

| | now.more | never | be.3pl.Fut | corrupted | nor | helpless |

| | ‘They will never again be corrupted nor helpless’ |

| | (Xavier, n.d., Corpus CIPM, Vidas de Santos, 14th cent.) |

| (22) | […] e | porende | juraron | que | nunca | a |

| | and | for.that | swear.3pl.Past | that | never | to |

| | crischãos | jamais | roubas[s]en, | e | se | quitas[s]en |

| | christians | now.more | steal.3pl.Imp.Subj | and | se.Reflx | quit.3pl.Imp.Subj |

| | daquela | folia | | | | |

| | of.that | madness | | | | |

| | ‘and for that they swore they would never steal Christians again and they would quit the madness’ |

| | (Barreiro, 2006–2018, Corpus Xelmírez, Lírica Profana Galego Portuguesa, 13th cent.) |

The frequent combination of jamais with nunca poses a question: was jamais a reinforcement element of the adverb nunca? I argue that it was not. If jamais were a reinforcement particle of nunca, we would expect it to also occur in non-negative contexts. As mentioned before, in Old Portuguese, nunca was also an MPI with existential interpretation. However, there are no attestations of jamais co-occurring with it, in modal contexts. The fact that jamais combined only with the NPI nunca in early texts but stopped occurring with it after becoming a negative item (their combination is ungrammatical nowadays) confirms that the two adverbs had different features. Jamais was still mostly a temporal–aspectual construction that did not compete with the NPI nunca for a similar function yet. In fact, nunca played the role of a sentential negation marker, just like não ‘no’. The apparent reinforcement value of jamais in negative sentences is actually due to the fact that both já and mais were (and still are) phasal adverbs. I will come back to this topic.

At least until the 15th century,

jamais displayed a ‘from this moment on… no longer’ interpretation and was therefore still temporal–aspectual. However, in the 15th century, we find the first occurrences of

jamais with a negative interpretation and as the single negative item in the clause. These contexts are scarce in the corpus, though, with two cases in the 15th and another two in the 16th century. In (23),

jamais occurs in preverbal position, without any other negative item and with the temporal negative reading of ‘never’ it has nowadays.

| (23) | […] e | foram | nossos | corações | tam | quebrados, | que |

| | […] and | be.3pl.Past | our | hearts | so | broken | that |

| | jamais | ousamos | volver | rrosto | comtra | vos. | |

| | never | dare.1pl.Past | turn | face | against | you.2pl | |

| | ‘and our hearts were so broken that we never dare to turn our face against you’ |

| | (Brocardo, 1997, Crónica do Conde D. Pedro de Menezes, 15th cent.) |

The interpretation of

jamais as a negative item meaning

never is also suggested by example (24), where it occurs as the second element of the expression

nunca, jamais, em tempo algum ‘never, never, in no time’, which presents the three negative temporal items available in Portuguese, ordered by emphatic force. This expression is frequently used to reinforce the idea that an action or event will never take place. In (24),

jamais can be understood as an equivalent of

nunca ‘never’ and is therefore not interpreted compositionally.

| (24) | E | derom | ao | dito | Gonçalo | Vaaz, | conprador, |

| | and | give.3pl.Past | to.the | said | Gonçalo | Vaaz | buyer |

| | por | qujte | liure | e | a | ssua | molher |

| | by | exempt | free | and | the | his | wife |

| | e/ | herdeiros | pera | ssenpre | que | nuca, | jamais |

| | and | heirs | for | always | that | never | never |

| | em | tenpo | alguu, | ssejom | demandado | por | ello. |

| | in | time | some | be.3pl.Pres.Sub | asked | by | him |

| | ‘And they considered the aforementioned Gonçalo Vaaz, buyer, his wife and heirs, free of debts forever, and that he shall never, ever, in no moment in time, be charged by him. |

| | (Martins, 2001, Documentos Portugueses do Noroeste e da Região de Lisboa (Chelas), 15th cent.) |

The appearance of the first cases of

jamais apparently as a strong NPI in the 15th century is in line with what is described for Spanish

jamás. Yamada (2023, pp. 11–12) also indicates the same chronology for the first attestations of

jamás with an entirely negative meaning and equivalent to

nunca.

11 Anyway, given the scarcity of the examples of

jamais as the only negative item in the sentence, we can only state that its status as a strong NPI cannot be prior to the 15th or 16th century.

As we have seen so far, the primary value of

jamais is that of a temporal–aspectual adverb, even in negative contexts. Although the primary temporal interpretation is futurity, the use of future tense is more expressive in negative contexts.

Table 3 shows the frequency of the future, past and present tenses, according to polarity.

Although the number of occurrences is quite uneven between affirmative and modal contexts compared to negative ones, it is clear that some tenses are favoured in specific polarity contexts. In negative contexts, jamais is highly associated with the expression of futurity, with future and conditional tenses representing more than half of the cases. On the other hand, affirmative–assertive contexts highly favour the use of present tense, due to the nature of declarative clauses, which are usually associated with the expression of facts, generalizations or axioms. Finally, modal contexts seem to favour both present and past tenses, although the low number of examples prevents us from drawing more solid conclusions. In any case, the subjunctive mood is preferred to the indicative mood, which is expected in modal contexts, since the subjunctive mood can license weak NPIs and MPIs, being associated with irrealis interpretations.

In the next section, I will present syntactic evidence to back up the idea that jamais started as two independent adverbs and its independent status as a lexical unit is coincident with its new negative feature.

5.3. The Status of Jamais: A Construction or an Independent Lexical Unit?

Although jamais is an independent lexical item that behaves as a strong NPI in contemporary data, early attestations show that it started as two non-polar adverbs that occurred in any polarity context with a temporal–aspectual interpretation. In this section, we will try to assess its level of internal syntactic analyzability in order to understand when it became a lexical unit.

Our hypothesis is that, in a first stage, já and mais were a frequent collocation that evolved into a construction, visible in the first texts, and finally it was reinterpreted as a lexical unit.

According to

Jiménez Juliá (

2017, p. 100), a string of words that is not yet a unit may be part of a productive model and will have internally recognizable parts. This means that internal word order can be seen as an argument in favour of the initial independence of the two adverbs.

Looking at the examples, we conclude that the predominant pattern was already the one where

já preceded

mais, as in (25), which is found in all the examples, except in three cases from the 13th century. Example (26), however, shows the possibility of having the order

mais já.| (25) | […] | e | nunca | folgava | senon | quando | a | fraqueza |

| | […] | and | never | rest.3sg.Imp | except | when | the | weakness |

| | era | tamanha | que | non | podia | ja | mais | andar |

| | be.3sg.Imp | such | that | neg | could | already | more | walk |

| | ‘and he never rested except when the weakness was such that he could no longer walk’ |

| | (A. F. Machado, 2013, Diálogos de São Gregório, 14th cent.) |

| (26) | Deffendemos | que | nenhuu | uozeyro | non | seya |

| | defend.2pl.Pres | that | none | attorney | neg | be.3sg.Pres.Subj |

| | ousado | de | auirsse | est | aquel | de |

| | bold | to | conciliate | this | that | of |

| | que | á | de | ter | uoz | nõ | tenha | |

| | who | have.3sg.Fut | voice | neg | have.3sg.Pres.Sub |

| | mays | ya | uoz | por | outro |

| | more | already | voice | for | other |

| | ‘We defend that no attorney should be bold to conciliate this, that whomever he defends should not be defended by any other henceforth.’ |

| | (Xavier, n.d., Corpus CIPM, Foro Real, 13th cent.) |

In (26), the two adverbs co-occur in adjacency, but the internal order is reversed. This corroborates the idea that jamais was not a unit yet and both orders já mais ‘now more’ and mais já ‘more now’ were possible in early attestations. Nevertheless, the order mais já is only found in negative contexts. This may be a consequence of the limited number of examples of modal and affirmative–assertive contexts, but it can also suggest that the construction evolved at a different pace in negative contexts.

Another good indicator of some level of syntactic independence of the two items in the construction is the existence of interpolation (cf.

Jiménez Juliá, 2017). The possibility of having lexical material between the two adverbs of the construction is an argument in favour of the syntactic independence of the parts.

Examples (27) and (28) show the possibility of the two adverbs being split by other constituents in a sentence. These occurrences are, however, infrequent, pointing to an increasing fixed status of the construction with

jamais. From a universe of 321 examples, only 5 exhibited interpolated elements between

já and

mais.

| (27) | Mays | chegado | he | o | día | que | sua | yrmãa |

| | but | arrived | be.3sg.Pres | the | day | that | his | sister |

| | Casandra | aujá | prophetizado, | et | ja | nõ | sse | podía |

| | Casandra | have.3sg.Imp | predicted | and | now | neg | it.reflx | could |

| | mays | perlongar. | | | | | | |

| | more | extend. | | | | | | |

| | ‘But the day his sister Casandra predicted has arrived and it could no longer be extended.’ |

| | (Barreiro, 2006–2018, Corpus Xelmírez, Cronica Troyana, 13th cent.) |

| (28) | […] | e | se | me | non | val | Deus |

| | […] | and | if | me.1sg.Reflx | neg | help.3sg.Pres | God |

| | (que | mi-a | mostre!), | ja | non | guarria | eu |

| | that | me.1sg.dat-her.3sg.acc | show | now | neg | prosper.1sg.Imp | I |

| | mais | no | mundo | | | | |

| | more | in.the | world | | | | |

| | ‘and if God does not help me (by showing her to me!), from now on, I will no longer prosper in the world.’ |

| | (Barreiro, 2006–2018, Corpus Xelmírez, Lírica Profana Galego Portuguesa, 13th cent.) |

In (27) and (28), the two adverbs are separated by lexical material, showing that they were not an independent unit yet. Nevertheless, the scarcity of these examples, which appear only in the 13th and 14th centuries, indicates the progressive loss of independence of the two components. Adjacency and fixed word order were fundamental for the reanalysis of

jamais as a unit since adjacency is required for the merger of the two adverbs.

12I introduce here an additional argument to support the idea that, in early occurrences, jamais was still a construction. While contemporary jamais ‘never’ cannot be interpreted compositionally, early occurrences of jamais could be interpreted by the sum of the parts, with each adverb modifying the VP.

In modal and negative contexts, when

já and

mais co-occured, the adverb

mais can be seen as an optional pseudoargument “indicating the extent or degree to which the predicate holds”, as proposed by

Breitbarth et al. (

2020, p. 50) when looking at optionally transitive verbs and alike. These contexts are usually considered ‘bridging contexts’, since they allow ambiguous readings, leading to the emergence of a more grammaticalized form (cf.

Lucas, 2007).

Sentences (29) and (30) allow

mais to be interpreted as the optional pseudoargument of the verb, expressing extent or degree, despite the adjacency to

já.

| (29) | -Padre | senhor, | nõ | seẏ | se | me | ueeres | iamais. |

| | father | lord | neg | know.1sg.Pres | if | me.1sg.acc | see | now.more |

| | ‘-My father, I don’t know if you will ever see me again.’ |

| | (Toledo Neto, 2012–2015, Demanda do Santo Graal, 13th cent.) |

| (30) | […] e | des | enton | non | braadou | jamais | o | enfermo […] |

| | […] and | since | then | neg | scream.3sg.Past | now.more | the | sick man |

| | ‘and since then, from that moment on, the sick man no longer screamed’ |

| | (A. F. Machado, 2013, Diálogos de São Gregório, 14th cent.) |

In sentence (29) the adverb mais can be interpreted as an extent/degree of the verb ver ‘see’, producing an interpretation equivalent to “ever… again”. Both the modal context and the use of conditional tense contribute to create an irrealis interpretation that eventually translated into ‘ever’. An equivalent scenario can be hypothesized for sentence (30), with mais being the extent/degree of the verb bradar ‘scream’ and translating into an interpretation of the type ‘from this moment on….no longer’.

The possibility of

mais being interpreted as a pseudoargument of the verb also shows that the two parts of the construction were still syntactically independent, but ambiguity tends to disappear with

jamais becoming a less free construction. The so-called ‘bridging contexts’ are said to be involved in the reanalysis of other non-negative items as negative polarity items across Romance languages (cf.

Roberts & Roussou, 2003;

Willis et al., 2013).

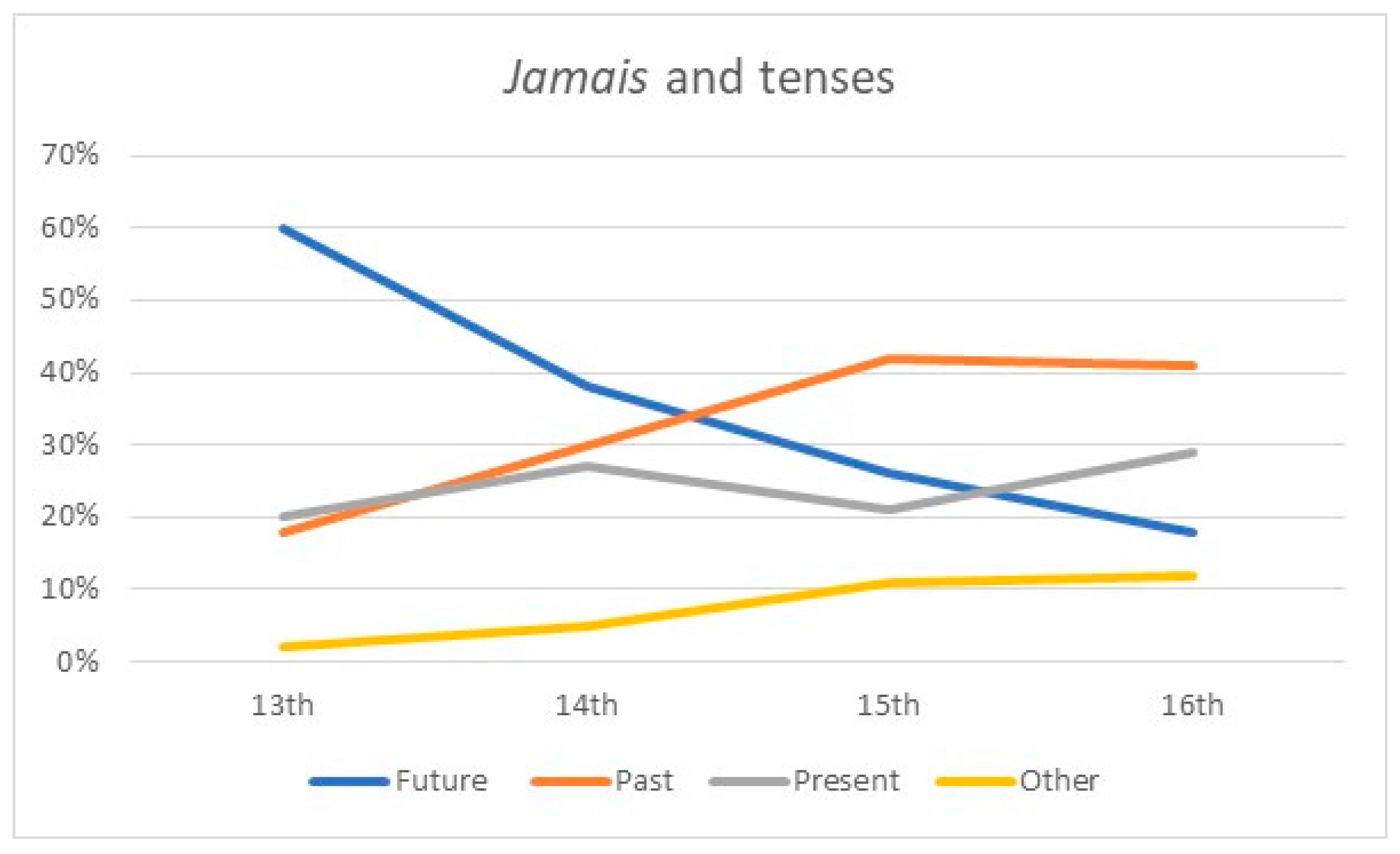

One final remark that shows the gradual loss of independence of the two items is related to tense features. As we have seen in

Table 3,

jamais was favoured in future tense contexts, future and conditional being the most frequent tenses in sentences with the construction. However, when we look at the distribution of future tenses across centuries, we see that the association of

jamais with a future or conditional verb decreases from the 13th century onwards, while past tenses tend to increase, as well as infinitives and gerunds (considered in the category

Other) (cf.

Figure 1). The association with present tenses remains steady, though. This same evolution is reported by

Hansen (

2012) for the French

jamais, which points to a more general tendency of these Romance constructions. The widening of its contexts of use may be seen as an indicator of the evolution of the construction into a unit.

The data seen so far seems to corroborate the idea that, in the 13th century, jamais was a construction with syntactic independence, but its parts did not occur freely. Internal word order was already established and interpolation rarely occurred. Also, although the two adverbs could have their own syntactic function, mostly in relation to the VP, this possibility was available only in modal and negative contexts, since affirmative–assertive sentences never displayed jamais at VP level.

5.4. Phasal Adverbs and No-Longer Expressions: The Origin Source of jamais?

In the previous sections, it became clear that jamais was strongly associated with negative contexts, despite the fact that neither of the adverbs in its formation was a NPI.

However, both adverbs

já and

mais share a particularity: they are considered phasal adverbs (cf.

van der Auwera, 1998) and integrate phasal polarity expressions (cf.

Vaquer, 2021). According to

Vaquer (

2021, p. 2), these expressions “encode the existence or non-existence of a situation in reference time compared to a preceding time, i.e., the situation’s continuation or discontinuation”.

In this section, I will argue that the association of já and mais as phasal adverbs in negative contexts is in the origin of jamais as an NPI.

In his work on phasal adverbs,

van der Auwera (

1998) draws attention to the Latin inchoative adverb

iam associated with

non as a way to express discontinuation, that is to say, a

no-longer reading.

van der Auwera (

1998) considers that languages have basic strategies to form

no-longer expressions (or ‘inchoative discontinuatives’) with a positive element meaning

already (an inchoative element) combined with a negator.

13 However, it is also possible to have a combined strategy involving two positive elements combined together with a negation.

van der Auwera (

1998) puts forth the idea that the evolution of

no-longer expressions is unidirectional and claims that the inchoative strategy inherited from Latin is being replaced by the comparative strategy with forms of

magis in Romance languages. Spanish is said to be the only Romance language to still keep the inchoative adverb to express ‘inchoative discontinuative’ values, while languages such as Portuguese are at an intermediate stage, allowing both inchoative and comparative elements. On the other side of the evolution is French, where only the comparative strategy with

plus is possible. This hypothesis was rejected by

Vaquer (

2021, p. 29), who considers that there is no evidence to conclude that Spanish only uses a purely inchoative strategy or that Portuguese, along with Galician and Catalan, is at an intermediate stage towards the adoption of a comparative strategy. Nevertheless, what is interesting in

van der Auwera (

1998)’s proposal is the fact that he predicts a period of transition from an inchoative to a comparative strategy where the two items combine. This is what is documented for French, Spanish and Portuguese, with

já and

mais being the positive elements co-occurring in negative sentences, with a reinforced

no-longer interpretation.

A context like the one in (31), where the inchoative and the comparative strategy coexist in association with a negative element, allowed for the formation of a construction that became negative. Although

jamais also occurs in affirmative-assertive and modal contexts, only the presence of negation could have allowed the addition of a negative feature to a purely temporal element.

| (31) | […] e | diserom | que | ja | mais | nom | quedariam | d |

| | and | say.3pl.Past | that | now | more | neg | stop.3pl.Cond | of |

| | andar | ataa | que | ujssem | atal | messa. | | |

| | walk | until | that | see.3pl.Imp.Subj | the.one | table | | |

| | ‘and they said that they, from that moment on, they would not stop walking until they saw the table’ |

| | (Toledo Neto, 2012–2015, Demanda do Santo Graal, 13th cent.) |

The original meaning of a sentence like (31) is that an action will be discontinued, starting in a certain moment, which is signalled by the presence of já. From this idea, there was a widening of the temporal timespan until reaching a ‘no moment in time’ interpretation. On the other hand, being in the scope of a negative element also contributed to the appearance of a [α neg] feature that followed the exact same path of evolution of other Portuguese n-words, becoming intrinsically negative, therefore [+ neg]. This explains the temporary occurrence of jamais in modal contexts and its specialization in negative environments.

Considering Spanish

jamás,

Llorens (

1929, p. 75) stated that it started as a temporal adverb that expressed future temporal negation, with its value sometimes getting mixed up with the perpetuity conveyed by

nunca ‘never’. We can assume that Portuguese

jamais evolution was also favoured by its association with this value of perpetuity.

Data from Portuguese shows that van der Auwera’s prediction on the disappearance of the inchoative strategy is still not visible in today’s data. This may indicate that the change is still in progress, but there is no way of knowing what the future outcome will be. Contemporary Portuguese still keeps both inchoative and comparative strategies with

já and

mais, and also the possibility to combine the two in the same utterance. These three possibilities are illustrated from (32) to (34).

| (32) | - Já | não | fumo. | |

| | now | neg | smoke.1sg.Pres | |

| | ‘I no longer smoke’ |

| (33) | - Não | fumo | mais. | |

| | neg | smoke.1sg.Pres | more | |

| | ‘I don’t smoke anymore’ |

| (34) | - Já | não | fumo | mais. |

| | now | neg | smoke.1sg.Pres | more |

| | ‘I don’t smoke anymore.’ |

Interestingly, configurations as the one in (34) are rare in diachronic data. We only found five cases of

já and

mais occurring separately. There seems to have been a tendency for

já and

mais to start appearing in adjacency, but that frequent collocation resulted in a construction with different temporal and polarity features, that is, the NPI

jamais. The temporal–aspectual reading of

já as meaning ‘from now on’ is progressively lost and is totally absent from the NPI

jamais, as we can see in the contrast between (34) and (35).

| (35) | - Não | fumo | jamais. |

| | neg | smoke.1sg.Pres | never |

| | ‘I don’t ever smoke.’ |

While in (34) it is implied that the person was a smoker before the enunciation moment, and the event of not smoking will only occur from that point onwards, in (35) we assume there was never a time when the person smoked.

At this point, it is clear that

jamais as the result of inchoative + comparative strategy and the strong NPI

jamais are two different elements. However, at least until the 15th century, all the occurrences found for

jamais in negative contexts still correspond to the combination of the inchoative and the comparative elements. The strong NPI

jamais emerges from the 15th century onwards, when we find its first occurrences expressing negation on its own. In the corpus, there are no examples of the combination of the inchoative + comparative strategy apart from the ones where

ja and

mais appear in adjacency (with the five exceptions mentioned before). We hypothesized that the first pattern of combination of the inchoative

já and the comparative

mais started with the two elements being apart. However, they eventually started occurring in adjacency, which allowed for the formation of a new lexical item, the strong NPI

jamais. As soon as

jamais becomes an independent item with different semantic and syntactic features, the old pattern to combine

já and

mais is restored. From the 16th century onwards, we start finding cases again of negative sentences with the adverbs

já and

mais without adjacency, as in (36).

14 This example shows that the strategy to combine inchoative and comparative elements was never abandoned. Both the strong NPI and the combination of

já and

mais to form

no-longer expressions coexist nowadays, but the pattern found in the latter structure does not exhibit adjacency of the elements

já and

mais as seen in Old Portuguese. In (36), the word order found is

já + neg + verb + mais.

| (36) | VM | dá | queixa | de | que | lhe | não |

| | you | give.3sg.Pres | complaint | of | that | you.3sg.Dat | neg |

| | dei | notícias | de | coisa | alguma | da | vida |

| | give.1sg.Past | news | of | thing | some | of.the | life |

| | da | senhora | dona | Joana | se | ir | desta |

| | of.the | lady | miss | Joana | se.Reflx | go | from.this |

| | casa, | por | já | não | se | poder | aturar |

| | house | for | now | neg | se.Impers | can | endure |

| | mais | as | suas | diabruras | | | |

| | more | the | her | devilries | | | |

| | ‘You complaint that I didn’t give you news of anything about miss Joana’s life and the fact that she left this house because no one could endure her devilries any longer.’ |

| | (Marquilhas, 2014, Corpus Post Scriptum, 18th cent.) |

It is necessary to investigate more data from the 16th century in order to confirm this idea. I remit this task to future work.