German Noun Plurals in Simultaneous Bilingual vs. Successive Bilingual vs. Monolingual Kindergarten Children: The Role of Linguistic and Extralinguistic Variables

Abstract

1. Introduction

1.1. German Noun Plurals

- Monosyllabic, final stop, article der or das (a prototypical singular of masculine or neuter gender, e.g., der Hund ‘the-MASC dog’);

- Polysyllabic, final -er (usually pronounced as [ɐ]), article der or das (probably a singular of masculine or neuter gender, e.g., der Teller ‘the-SG:MASC plate’, but rarely also a genitive plural ([der Stapel] der Teller ‘[the stack of] the-PL:GEN plates’);

- Polysyllabic, final -e, article die (with equal probability either a feminine singular or a plural of any gender, i.e., neither a prototypical singular nor a prototypical plural, e.g., the rhyming words die Schleuse ‘the-SG:FEM sluice’ vs. die Mäuse ‘the-PL mice’, but also the examples die Katze ‘the-SG:FEM cat’ vs. die Hunde ‘the-PL dogs’ in Table 1).

- Polysyllabic, final -er, article die (probably a plural of masculine or neuter gender, e.g., die Teller ‘the-PL plates’, and less probably a feminine singular, e.g., die Mauer ‘the-SG:FEM wall’);

- Polysyllabic, final -en, article die (a prototypical plural, e.g., die Katzen ‘the-PL cats’ from the feminine Singular die Katze ‘the cat’, but also die Daumen ‘the-PL thumbs’, a zero plural from the masculine singular der Daumen ‘the-SG:MASC thumb’).

| (1) | a. | ich | mag | die | Fühler. | (L2_02Hf, 2;11) |

| I | like-1SG | the-PL | feeler-0PL | |||

| ‘I like the feelers/antennae.’ | ||||||

| b. | mach~ma | noch | Anhänger? | (1L1_05Lm, 3;1) | ||

| make~we | still | trailer-0PL | ||||

| ‘Do we still make trailers?’ | ||||||

| c. | dick+e | blau+e | Streifen. | (1L1_25Lm, 3;0) | ||

| thick-PL-INDEF | blue-PL-INDEF | stripe-0PL | ||||

| ‘Thick blue stripes.’ | ||||||

| d | das | sind | Kuchen. | (1L1_22Lf, 2;11) | ||

| this | be-3PL | cake-0PL | ||||

| ‘These are cakes.’ | ||||||

1.2. Croatian Noun Plurals

1.3. Turkish Noun Plurals

1.4. Research Questions

2. Methodology

2.1. Participants

2.2. Methods

- A plural elicitation test in German (conducted twice by the researchers with all children) using a procedure similar to Berko’s (1958) famous wug test was administered; however, real words were used instead of pseudowords because the results should be comparable to actual plurals produced in spontaneous speech (for details on the procedure and the materials see Appendix A);

- One-hour-long spontaneous speech audio and video recordings of teacher–child interaction in kindergarten were conducted and the “best” 30 minutes, i.e., the ones with the most direct verbal interaction between the teacher5 and the target child, were selected by the researchers to be transcribed by advanced students. For German kindergarten recordings, we analyzed all recordings available (4 recordings of 30 minutes for 58 children, and 3 recordings of 30 minutes for one LSES L2 girl who entered kindergarten only before the second datapoint), while for one HSES L1 girl, we had no permission to make recordings in her kindergarten, and thus, only her plural test was included.

3. Results

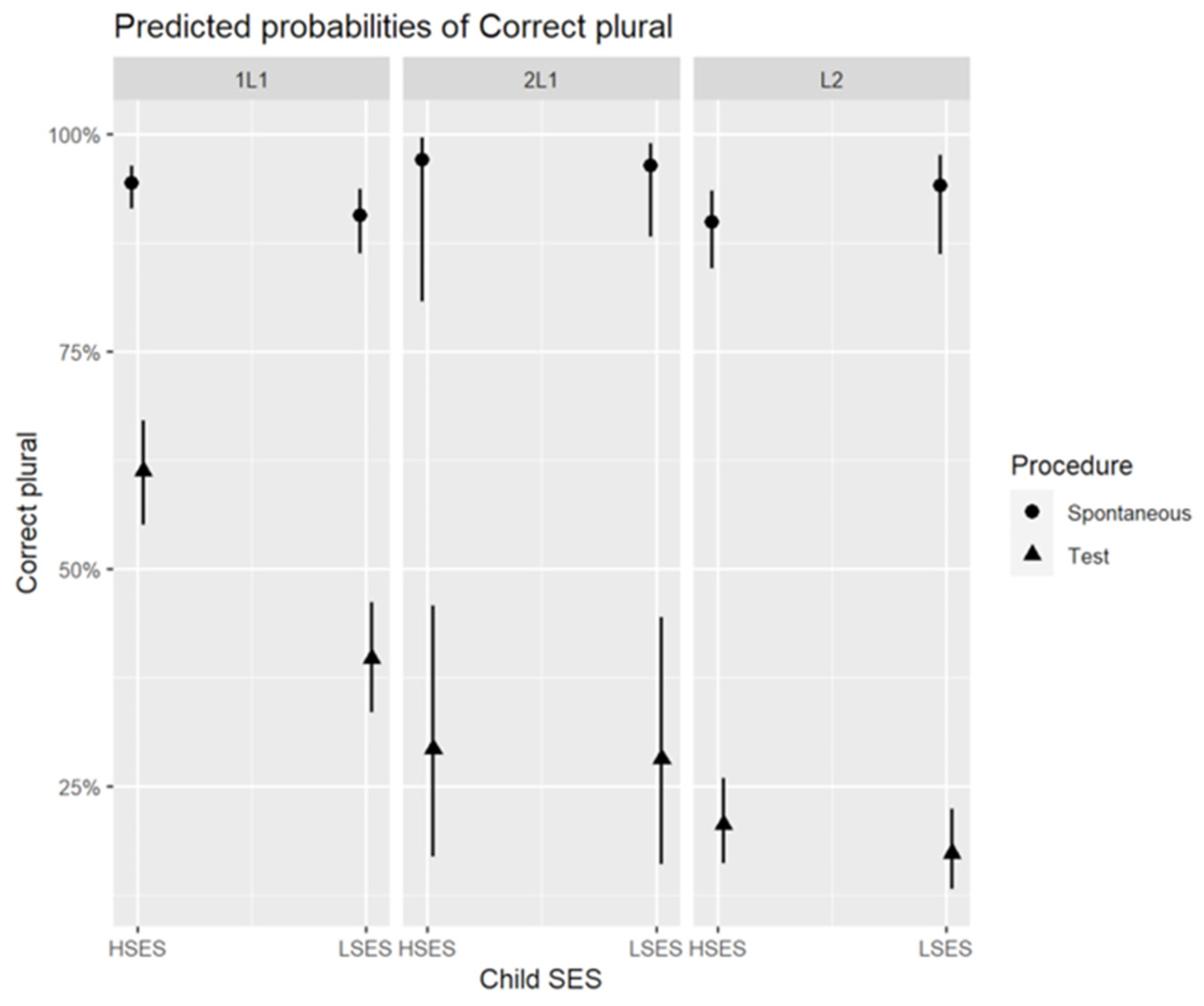

3.1. All Children: Effects of Language Background, SES and the Procedure on German Plural Production

3.2. German Plural Test Results in the Three Groups of Children

3.2.1. Correct Plurals in the Plural Test

3.2.2. Incorrect Zero Plurals in the Plural Test

3.2.3. Overt Overgeneralizations in the Plural Test

3.3. German Spontaneous Speech Results in the Three Groups of Children

3.3.1. Correct Plurals in Spontaneous Speech

3.3.2. Incorrect Zero Plurals in Spontaneous Speech

3.3.3. Overt Overgeneralizations in Spontaneous Speech

4. Discussion

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

- At what age did your child start to attend a German-speaking daycare?

- How is a typical (week)day of your child structured?

- Which languages does your child speak and understand?

- How important is it for you that your child speaks these languages?

- Which languages do you speak and since when?

- Which languages do you speak to which persons in your family?

- To which persons does your child regularly talk to and in which language?

- (For bilingual parents:) How do you decide which language you speak to your child?

- For how many years did you/your partner attend school?

- What is your/your partner’s highest educational level?

- What is your/your partner’s profession?

- How do you consider the economic situation of your family?

- Experimenter (showing a picture card with one item,, e.g., one rabbit, to the child): “This is a rabbit.”

- Experimenter (showing another picture card with three of the same items,, e.g., three rabbits, to the child): “And these are three…?”

- Child (completing the sentence): “… rabbits.”

| No. | Singular (Stimulus) | Plural (Target) | Plural Marker (Target) | Grammatical Gender | English Plural |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| A | Auto | Autos | -s | neuter | cars |

| B | Baum | Bäume | umlaut + -e | masculine | trees |

| C | Banane | Bananen | -(e)n | feminine | bananas |

| 1 | Bett | Betten | -(e)n | neuter | beds |

| 2 | Mädchen | Mädchen | zero | neuter | girls |

| 3 | Haus | Häuser | umlaut + -er [ɐ] | neuter | houses |

| 4 | Pyjama | Pyjamas | -s | masculine | pyjamas |

| 5 | Fenster | Fenster | zero | neuter | windows |

| 6 | Schiff | Schiffe | -e | neuter | ships |

| 7 | Mantel | Mäntel | umlaut | masculine | coats |

| 8 | Katze | Katzen | -(e)n | feminine | cats |

| 9 | Zug | Züge | umlaut + -e | masculine | trains |

| 10 | Kuh | Kühe | umlaut + -e | feminine | cows |

| 11 | Apfel | Äpfel | umlaut | masculine | apples |

| 12 | Oma | Omas | -s | feminine | grandmas |

| 13 | Hase | Hasen | -(e)n | masculine | rabbits/hares |

| 14 | Maus | Mäuse | umlaut + -e | feminine | mice |

| 15 | Teller | Teller | zero | masculine | plates |

| 16 | Stift | Stifte | -e | masculine | pencils |

| 17 | Bild | Bilder | -er [ɐ] | neuter | pictures |

| 18 | Schneemann | Schneemänner | umlaut + -er [ɐ] | masculine | snowmen |

| 19 | Vogel | Vögel | umlaut | masculine | birds |

| 20 | Baby | Babys | -s | neuter | babies |

| 21 | Ball | Bälle | umlaut + -e | masculine | balls |

Appendix B

| Procedure | (1) 1L1 | (2) 2L1 | (3) L2 | Total Tokens | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Test | Correct plurals | 605 | 49 | 186 | 840 |

| Incorrect zero plurals | 320 | 95 | 608 | 1023 | |

| Overt overgeneralizations | 205 | 15 | 81 | 301 | |

| Other non-target plurals | 56 | 10 | 72 | 138 | |

| Spontaneous | Correct plurals | 682 | 114 | 288 | 1084 |

| Incorrect zero plurals | 22 | 2 | 14 | 38 | |

| Overt overgeneralizations | 26 | 2 | 13 | 41 | |

| Other non-target plurals | 6 | 1 | 7 | ||

| Total tokens | 1954 | 286 | 1450 | 3690 |

| 1 | The data of this study have already been analyzed in previous studies (L1 and L2 German in Korecky-Kröll et al. 2018; 2L1 Croatian and German in Camber (2020) as well as in Camber and Dressler (2022)), but with different foci: a type analysis comparing the method of test vs. spontaneous speech in L1 and L2 German of different sociodemographic groups in Korecky-Kröll et al. (2018) and a comparison between plural types and tokens produced in 2L1 German vs. Croatian in Camber (2020) as well as Camber and Dressler (2022), whereas the focus of the present study is a token analysis of monolingual vs. simultaneous vs. successive bilingual acquisition. |

| 2 | Köpcke (1993, pp. 82–83) defined cue strength as a composite variable of salience, type and token frequency and cue validity, and cue validity is “the frequency with which a particular marker occurs in the category which contrasts with the target category” (Köpcke 1998, p. 300). For example, the English plural marker [ız] has high cue validity for plural because there are almost no singular nouns ending in [ız], whereas [s] has low cue validity for plural because many singular nouns end in [s] (Köpcke 1998, pp. 300–1). |

| 3 | While 0 means a monosyllabic noun without any specific ending, the other forms with the endings listed in the scale are all disyllabic. |

| 4 | In German dialects using more zero plural variants than Standard German, adult dialect speakers were shown to produce more zero plurals in clearly disambiguated syntactic contexts, whereas they used more suffixed and/or umlaut plurals in syntactically ambiguous contexts (Nickel and Werth 2022). |

| 5 | Some children had the same teacher, others changed the group or got a new teacher, as fluctuation of staff in kindergartens is very high. Nevertheless, all children had exposure to teacher input in German, and the frequencies of noun plurals of individual teachers were considered in the cumulative teacher plural type and token frequencies. |

| 6 | For example, the teacher of one child produces eight different plural types at the first recording. However, some plurals are repeated within the same recording—so the teacher uses 15 plural tokens (including repetitions). At the second recording, the teacher produces 19 new plural types corresponding to 34 plural tokens (including repetitions). The cumulative input at the second datapoint thus corresponds to 27 plural types (i.e., 8 types from the first + 19 types from the second recording) or 49 (15 + 34) tokens. In the third and the fourth recordings, the cumulative input will be even higher, as all previous recordings are considered as well. To attenuate effects of potential outliers (i.e., recordings in which teachers used particularly many or few plurals), the cumulative frequencies were log-normalized, i.e., the final value for cumulative teacher type frequency at the second recording of the above example was 1.431 (the decimal logarithm of 27), and the final value for cumulative teacher token frequency at the second recording was 1.690 (the decimal logarithm of 49). Such normalizing of frequency data is a common procedure in psycholinguistic studies (see, e.g., Levshina 2015, p. 66). |

| 7 | As the Viennese variety of Austrian German investigated does not regularly use subtractive plurals, which would be anti-iconic (such as Franconian hon from the singular hond ‘dog’, see Dressler 2000, p. 290), we classified the rare subtractive plurals used by the children (e.g., Zu from the singular Zug ‘train’ as “other forms” and not as overgeneralizations of subtractive plurals. |

| 8 | In the analyses of correct plurals, the target and the actual plural form are the same, and so are the corresponding linguistic variables. Thus, we mention only plural schema reliability, constructional iconicity, morphotactic transparency, productivity and total naturalness when dealing with correct plurals, whereas we differentiate between target and actual plural schema reliability, constructional iconicity, morphotactic transparency, productivity and total naturalness in the analyses of incorrect zero plurals and overt overgeneralizations. |

References

- Aksu-Koç, Ayhan, and Dan I. Slobin. 1985. The acquisition of Turkish. In The Crosslinguistic Study of Language Acquisition. Edited by Dan I. Slobin. London: Psychology Press, pp. 839–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Altan, Aslı, Utku Kaya, and Annette Hohenberger. 2016. Sensitivity of Turkish Infants to Vowel Harmony in Stem-Suffix Sequences: Preference Shift from Familiarity to Novelty. In BUCLD 40 Online Proceedings Supplement. Edited by Jennifer Scott and Deb Waughtal. Available online: https://www.bu.edu/bucld/files/2016/09/BUCLD_Proceedings_2016_01_25_altan1.pdf (accessed on 6 May 2024).

- Berko, Jean. 1958. The Child’s Learning of English Morphology. Word 14: 150–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bialystok, Ellen, and Mythili Viswanathan. 2009. Components of executive control with advantages for bilingual children in two cultures. Cognition 112: 494–500. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Blom, Elma, Aylin C. Küntay, Marielle Messer, Josje Verhagen, and Paul Leseman. 2014. The benefits of being bilingual: Working memory in bilingual Turkish–Dutch children. Journal of Experimental Child Psychology 128: 105–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blom, Elma, Johanne Paradis, and Tamara Sorenson Duncan. 2012. Effects of Input Properties, Vocabulary Size, and L1 on the Development of Third Person Singular -s in Child L2 English. Language Learning 62: 965–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Camber, Marina. 2020. Simultaneous Acquisition of Austrian German and Croatian at Home and in Preschool. Ph.D. dissertation, University of Vienna, Vienna, Austria. Available online: https://utheses.univie.ac.at/detail/57467 (accessed on 6 May 2024).

- Camber, Marina, and Wolfgang U. Dressler. 2022. Simultan-bilingualer Pluralerwerb von Deutsch und Kroatisch. Zagreber Germanistische Beiträge 31: 5–30. [Google Scholar]

- Chee, Melvatha R., Frances V. Jones, Jill P. Morford, and Naomi L. Shin. 2023. Usage-Based Approaches to Child Language Development. In The Handbook of Usage-Based Linguistics. Edited by Manuel Díaz-Campos and Sonia Balasch. Hoboken: Wiley, pp. 379–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clahsen, Harald. 1999. Lexical entries and rules of language: A multidisciplinary study of German inflection. Behavioral and Brain Sciences 22: 991–1013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cole, Molly, and Jenny Dumont. 2023. Usage-Based Theory and Bilingualism. In The Handbook of Usage-Based Linguistics. Edited by Manuel Díaz-Campos and Sonia Balasch. Hoboken: Wiley, pp. 363–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Czinglar, Christine, Katharina Korecky-Kröll, Kumru Uzunkaya-Sharma, and Wolfgang U. Dressler. 2015. Wie beeinflusst der sozioökonomische Status den Erwerb der Erst- und Zweitsprache? Wortschatzerwerb und Geschwindigkeit im NP/DP-Erwerb bei Kindergartenkindern im türkisch-deutschen Kontrast. In Deutsche Grammatik in Kontakt. Deutsch als Zweitsprache in Schule und Unterricht. Edited by Klaus-Michael Köpcke and Arne Ziegler. Berlin: De Gruyter, pp. 207–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Houwer, Annick. 2021. Bilingual Development in Childhood. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dressler, Wolfgang U. 2000. Naturalness. In Morphology. An International Handbook on Inflection and Word-Formation. Edited by Geert Booij, Christian Lehmann, Joachim Mugdan, Wolfgang Kesselheim and Stavros Skopeteas. Berlin: De Gruyter Mouton, vol. 1, pp. 288–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dressler, Wolfgang U. 2003. Degrees of grammatical productivity in inflectional morphology. Italian Journal of Linguistics 15: 31–62. [Google Scholar]

- Dressler, Wolfgang U., Anastasia Christofidou, Natalia Gagarina, Katharina Korecky-Kröll, and Marianne Kilani-Schoch. 2020. Morphological blind-alley developments as a theoretical challenge to both usage-based and nativist acquisition models. Italian Journal of Linguistics 31: 107–40. [Google Scholar]

- Dressler, Wolfgang U., Anastasia Christofidou, Natalia Gagarina, Katharina Korecky-Kröll, and Marianne Kilani-Schoch. 2023. Blind Alley Developments (BADs): In defense of our approach. Italian Journal of Linguistics 35: 231–40. [Google Scholar]

- Ellis, Nick C., and Stefanie Wulff. 2020. Usage-based approaches to L2 acquisition. In Theories in Second Language Acquisition. An Introduction, 3rd ed. Edited by Bill VanPatten, Gregory D. Keating and Stefanie Wulff. New York and London: Routledge, pp. 63–82. [Google Scholar]

- Ganzeboom, Harry B. G., and Donald J. Treiman. 1996. Internationally Comparable Measures of Occupational Status for the 1988 International Standard Classification of Occupations. Social Science Research 25: 201–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gathercole, Virginia C. M., and Erika Hoff. 2007. Input and the acquisition of language: Three questions. In Blackwell Handbook of Language Development. Edited by Erika Hoff and Marilyn Shatz. Malden: Blackwell, pp. 107–27. [Google Scholar]

- Geeslin, Kimberly L., Danielle Daidone, Avizia Y. Long, and Megan Solon. 2023. Usage-Based Models of Second Language Acquisition. In The Handbook of Usage-Based Linguistics. Edited by Manuel Díaz-Campos and Sonia Balasch. Hoboken: Wiley, pp. 345–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goebel, Rainer, and Peter Indefrey. 2000. A recurrent network with short-term memory capacity learning the German -s plural. In Models of Language Acquisition. Edited by Peter Broeder and Jaap Murre. Oxford: Oxford University Press, pp. 177–200. [Google Scholar]

- Hahn, Ulrike, and Ramin C. Nakisa. 2000. German inflection: Single route or dual route? Cognitive Psychology 41: 313–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ketrez, F. Nihan. 2023. Are Turkish non-case-marked objects with and without bir interpreted and acquired differently? Languages 8: 229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ketrez, F. Nihan, and Ayhan Aksu-Koç. 2009. Early nominal morphology in Turkish: Emergence of case and number. In Development of Nominal Inflection in First Language Acquisition. Edited by Ursula Stephany and Maria D. Voeikova. Berlin and New York: De Gruyter Mouton, pp. 15–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kidd, Evan, and Seamus Donnelly. 2020. Individual differences in first language acquisition. Annual Review of Linguistics 6: 319–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klampfer, Sabine, Katharina Korecky-Kröll, and Wolfgang U. Dressler. 2001. Morphological potentiality in children’s overgeneralization patterns: Evidence from Austrian German noun plurals. Wiener Linguistische Gazette 67: 25–43. [Google Scholar]

- Korecky-Kröll, Katharina. 2011. Der Erwerb der Nominalmorphologie bei zwei Wiener Kindern: Eine Untersuchung im Rahmen der Natürlichkeitstheorie. Ph.D. dissertation, University of Vienna, Vienna, Austria. Available online: https://utheses.univie.ac.at/detail/16983 (accessed on 13 September 2024).

- Korecky-Kröll, Katharina, Neriman Dobek, Verena Blaschitz, Sabine Sommer-Lolei, Monika Boniecki, Kumru Uzunkaya-Sharma, and Wolfgang U. Dressler. 2019. Vocabulary as a central link between phonological working memory and narrative competence: Evidence from monolingual and bilingual 4-year olds from different socioeconomic backgrounds. Language and Speech 62: 546–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Korecky-Kröll, Katharina, Sabine Sommer-Lolei, Viktoria Templ, Maria Weichselbaum, Kumru Uzunkaya-Sharma, and Wolfgang U. Dressler. 2018. Plural variation in L1 and early L2 acquisition of German: Social, dialectal and methodological factors. CogniTextes 17: 974. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kornfilt, Jaklin. 1997. Turkish. London and New York: Routledge (Descriptive Grammars). [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kovačević, Melita, Marijan Palmović, and Gordana Hržica. 2009. The acquisition of case, number, and gender in Croatian. In Development of Nominal Inflection in First Language Acquisition. Edited by Ursula Stephany and Maria D. Voeikova. Berlin and New York: De Gruyter Mouton, pp. 153–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Köpcke, Klaus-Michael. 1993. Schemata bei der Pluralbildung im Deutschen: Versuch einer kognitiven Morphologie. Tübingen: Narr. [Google Scholar]

- Köpcke, Klaus-Michael. 1998. The acquisition of plural marking in English and German revisited: Schemata versus rules. Journal of Child Language 25: 293–319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Köpcke, Klaus-Michael, and Verena Wecker. 2017. Source- and product-oriented strategies in L2 acquisition of plural marking in German. Morphology 27: 77–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laaha, Sabine, and Wolfgang U. Dressler. 2012. Suffix predictability and stem transparency in the acquisition of German noun plurals. In Current Issues in Morphological Theory: (Ir)regularity, Analogy and Frequency. Edited by Ferenc Kiefer, Mária Ladányi and Péter Siptár. Amsterdam: Benjamins, pp. 217–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laaha, Sabine, Dorit Ravid, Katharina Korecky-Kröll, Gregor Laaha, and Wolfgang U. Dressler. 2006. Early noun plurals in German: Regularity, productivity or default? Journal of Child Language 33: 271–302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Levshina, Natalia. 2015. How to Do Linguistics with R. Data Exploration and Statistical Analysis. Amsterdam and Philadelphia: Benjamins. [Google Scholar]

- MacWhinney, Brian. 2000. The CHILDES Project: Tools for Analyzing Talk. Volume 1: Transcription Format and Programs. Mahwah: Erlbaum. [Google Scholar]

- Mattiello, Elisa, and Wolfgang U. Dressler. 2022. Dualism and superposition in the analysis of English synthetic compounds ending in -er. Linguistics 60: 395–461. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mayerthaler, Willi. 1981. Morphologische Natürlichkeit. Wiesbaden: Athenaion. [Google Scholar]

- McCurdy, Kate, Adam Lopez, and Sharon Goldwater. 2020. Conditioning, but on Which Distribution? Grammatical Gender in German Plural Inflection. In Workshop on Cognitive Modeling and Computational Linguistics 2020. Edited by Emmanuele Chersoni, Cassandra Jacobs, Yohei Oseki, Laurent Prévot and Enrico Santus. Stroudsburg: Association for Computational Linguistics, pp. 59–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morgenstern, Aliyah. 2022. Children’s multimodal language development from an interactional, usage-based, and cognitive perspective. Wiley Interdisciplinary Reviews: Cognitive Science 14: 2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nickel, Grit, and Alexander Werth. 2022. Zwischen ungebändigter Allomorphie und gesteuertem Deklinationsklassenwandel. Intra- und interindividuelle Variation in der Pluralmarkierung bayerischer und thüringischer Dialekte. In Struktur von Variation zwischen Individuum und Gesellschaft. Akten der 14. Bayerisch-Österreichischen Dialektologietagung 2019. Edited by Philip C. Vergeiner, Stephan Elspaß and Dominik Wallner. Stuttgart: Steiner, pp. 81–102. [Google Scholar]

- OECD. 1999. Classifying Educational Programmes. Manual for ISCED-97 Implementation in OECD Countries. Paris: OECD. [Google Scholar]

- Paradis, Johanne, Brian Rusk, Tamara Sorenson Duncan, and Krithika Govindarajan. 2017. Children’s Second Language Acquisition of English Complex Syntax: The Role of Age, Input, and Cognitive Factors. Annual Review of Applied Linguistics 37: 148–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peirce, Charles S. 1965. Collected papers. Cambridge: Harvard University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Ready, Douglas D. 2010. Socioeconomic Disadvantage, School Attendance, and Early Cognitive Development: The Differential Effects of School Exposure. Sociology of Education 83: 271–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rinaldi, Pasquale, Patrizio Pasqualetti, Virginia Volterra, and Maria Cristina Caselli. 2023. Gender differences in early stages of language development. Some evidence and possible explanations. Journal of Neuroscience Research 101: 643–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schielzeth, Holger, Niels J. Dingemanse, Shinichi Nakagawa, David F. Westneat, Hassen Allegue, Céline Teplitsky, Denis Réale, Ned A. Dochtermann, László Zsolt Garamszegi, and Yimen G. Araya-Ajoy. 2020. Robustness of linear mixed-effects models to violations of distributional assumptions. Methods in Ecology and Evolution 11: 1141–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seifert, Katharina. 1988. Ikonizität von Pluralformen: Eine Untersuchung zur psychologischen Realität der linguistischen Theorie der „natürlichen Morphologie“. Vienna: VWGÖ. [Google Scholar]

- Templ, Viktoria, Maria Weichselbaum, Katharina Korecky-Kröll, and Wolfgang U. Dressler. 2018. Deutschspracherwerb ein- und zweisprachiger Wiener Kindergartenkinder: Der Einfluss des sozioökonomischen Status der Familie, des sprachlichen Hintergrunds und der Sprechsituationen. In Migration und Integration—Wissenschaftliche Perspektiven aus Österreich. Jahrbuch 4/2018. Edited by Jennifer Carvill Schellenbacher, Julia Dahlvik, Heinz Fassmann and Christoph Reinprecht. Göttingen: V&R Unipress, Vienna University Press, pp. 195–201. [Google Scholar]

- Titone, Debra A., and Mehrgol Tiv. 2022. Rethinking multilingual experience through a Systems Framework of Bilingualism. Bilingualism: Language and Cognition 26: 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wecker, Verena. 2016. Strategien bei der Pluralbildung im DaZ-Erwerb. Eine Studie mit russisch- und türkischsprachigen Lernern. Berlin and Boston: De Gruyter. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wegener, Heide. 2008. Der Erwerb eines komplexen morphologischen Systems in DaZ: Der Plural deutscher Substantive. In Fortgeschrittene Lernervarietäten: Korpuslinguistik und Zweitspracherwerbsforschung. Edited by Maik Walter and Patrick Grommes. Tübingen: Niemeyer, pp. 93–117. [Google Scholar]

- Weizman, Zehava O., and Catherine E. Snow. 2001. Lexical input as related to children’s vocabulary acquisition: Effects of sophisticated exposure and support for meaning. Developmental Psychology 37: 265–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yamashita, Taichi, and Reza Neiriz. 2024. Why replicate? Systematic review of calls for replication in Language Teaching. Research Methods in Applied Linguistics 3: 100091. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| No. | Plural Marker | Singular | Plural | English Plural |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | +s | Baby | Baby+s | babies |

| 2 | +(e)n | Katze | Katze+n | cats |

| 3 | +e | Hund | Hund+e | dogs |

| 4 | umlaut+e | Zug | Züg+e | trains |

| 5 | zero | Teller | Teller | plates |

| 6 | umlaut | Apfel | Äpfel | apples |

| 7 | +er [ɐ] | Bild | Bild+er | pictures |

| 8 | umlaut+er [ɐ] | Haus | Häus+er | houses |

| A: Plural Reliability (SM) | B: Constructional Iconicity (NM) | C: Morphotactic Transparency (NM) | D: Productivity (NM) | E: Total Naturalness (NM): B+C+D |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0: 0 (Hund) | 0: Teller | 0: Äpfel, Häuser | 0: Äpfel, Häuser | 1: Äpfel |

| 1: -e (Katze, Hunde) | 1: Äpfel | 1: Bilder, Hunde | 1: Züge | 2: Häuser |

| 2: -el (Stapel) | 2: Züge, Häuser | 2: Babys, Katzen, | 2: Hunde, Teller | 3: Züge |

| 3: -er (Teller) | 3: Babys, Katzen, | Teller | 3: Babys, Katzen | 4: Teller, Bilder |

| 4: -s (Babys) | Bilder | 5: Betten, Hunde | ||

| 5: -en (Katzen) | 6: Schuhe | |||

| 7: Stifte | ||||

| 8: Babys, Katzen |

| Prototypical Declension Classes in Croatian | Plural Marking in Turkish | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gender | SG | PL | Vowel harmony | SG | PL |

| feminine | -a | +e | front vowel | – | +ler |

| (e-declension) | djevojčica ‘girl’ | djevojčice ‘girls’ | kedi ‘cat’ | kediler ‘cats’ | |

| masculine | consonant, -o | +a | back vowel | – | +lar |

| (a-declension) | auto ‘car’ | auta ‘cars’ | araba ‘car’ | arabalar ‘cars’ | |

| neuter | -o, -e | +a | |||

| (a-declension) | drvo ‘tree’ | drva ‘trees’ | |||

| Group | Acquisition Setting | Languages | SES | Gender | Total |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| (1) | 1L1 | German | high | 7 boys, 8 girls | 15 |

| 1L1 | German | low | 8 boys, 6 girls | 14 | |

| (2) | L2 | Turkish, German | high | 6 boys, 8 girls | 14 |

| L2 | Turkish, German | low | 7 boys, 6 girls | 13 | |

| (3) | 2L1 | Croatian, German | high | 2 boys | 2 |

| 2L1 | Croatian, German | low | 1 boy, 1 girl | 2 | |

| Total | 60 |

| Fixed Effects | Estimate | Standard Error | z Value | p Value | Significance |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| (Intercept) | 2.8354 | 0.2363 | 12.000 | <0.001 | *** |

| Lgbg2L1 | 0.6717 | 1.0822 | 0.621 | 0.534812 | |

| LgbgL2 | −0.6449 | 0.3437 | −1.877 | 0.060571 | . |

| SESLSES | −0.5587 | 0.3240 | −1.725 | 0.084609 | . |

| ProcTest | −2.3773 | 0.2299 | −10.340 | <0.001 | *** |

| Lgbg2L1:SESLSES | 0.3400 | 1.2819 | 0.265 | 0.790829 | |

| LgbgL2:SESLSES | 1.1446 | 0.6324 | 1.810 | 0.070331 | . |

| Lgbg2L1:ProcTest | −2.0106 | 1.0730 | −1.874 | 0.060953 | . |

| LgbgL2:ProcTest | −1.1643 | 0.3408 | −3.416 | 0.000634 | *** |

| LSES:ProcTest | −0.3189 | 0.3154 | −1.011 | 0.311941 | |

| Lgbg2L1:SESLSES:ProcTest | 0.4797 | 1.2686 | 0.378 | 0.705368 | |

| LgbgL2:SESLSES:ProcTest | −0.4806 | 0.6315 | −0.761 | 0.446619 | |

| Significance levels: | *** 0.001 | ** 0.01 | * 0.05 | . 0.1 (trend) |

| Models and Variables | (1) 1L1 | (2) 2L1 | (3) L2 |

|---|---|---|---|

| Best overall model (significant variables in bold, asterisk in bold for significant interaction effects) | SES * Datapoint + Productivity + cumulative teacher plural type frequency (log) | Datapoint + Morphotactic transparency | Datapoint + Morphotactic transparency |

| Variables and variants of the best models (z values and significance levels) | SESLSES (−3.664 ***), Datapoint 4 (3.495 ***) Productivity (10.635 ***), cumulative teacher PL type frequency (log) (1.397) SESLSES * Datapoint 4 (−1.966 *) | Datapoint 4 (4.317 ***), Morphotactic transparency (5.471 ***) | Datapoint 4 (2.901 **), Morphotactic transparency (8.994 ***) |

| Variables and Variants | (1) 1L1 | (2) 2L1 | (3) L2 |

|---|---|---|---|

| Datapoint 4 | 5.252 *** | 3.774 *** | 2.588 ** |

| SES LSES | −7.120 *** | −0.170 | −1.40 |

| Gender male (m) | −0.734 | −1.461 | −0.856 |

| Kindergarten exposure hours (log) | 3.124 ** | 4.188 *** | 2.413 * |

| Cumulative teacher PL type frequency (log) | 4.553 *** | 3.765 *** | 1.144 |

| Cumulative teacher PL token frequency (log) | 4.158 *** | 3.921 *** | 2.005 * |

| PL schema reliability | 3.207 ** | 3.196 ** | 7.026 *** |

| Constructional iconicity | 0.952 | −3.096 ** | −12.064 *** |

| Morphotactic transparency | 9.728 *** | 5.197 *** | 8.948 *** |

| Productivity | 10.256 *** | 5.059 *** | 9.757 *** |

| Total PL naturalness | 8.945 *** | 3.623 *** | 4.184 *** |

| Models and Variables | (1) 1L1 | (2) 2L1 | (3) L2 |

|---|---|---|---|

| Best overall model (significant variables in bold, asterisk in bold for significant interaction effects) | SES + Actual PL schema reliability + cumulative teacher PL type frequency (log) | SES * Datapoint + Actual PL productivity | SES * Actual PL total naturalness |

| Variables and variants of the best models (z values and significance levels) | SESLSES (6.167 ***), Actual PL schema reliability (−13.933 ***), cumulative teacher PL type frequency (log) (−2.881 **) | SESLSES (−0.687), Datapoint 4 (−4.275 ***), Actual PL productivity (−5.730 ***) SESLSES * Datapoint 4 (3.043 **) | SESLSES (2.943 **), Actual PL total naturalness (−9.744 ***) SESLSES * Actual PL total naturalness (−2.804 **) |

| Variables and Variants | (1) 1L1 | (2) 2L1 | (3) L2 |

|---|---|---|---|

| Datapoint 4 | −3.422 *** | −4.692 *** | −1.217 |

| SES LSES | 7.769 *** | 1.707 . | 3.548 *** |

| Gender m | −0.048 | 0.628 | −0.251 |

| Kindergarten exposure hours (log) | −1.869 . | −4.863 *** | −3.127 ** |

| Cumulative teacher PL type frequency (log) | −3.292 *** | −4.105 *** | 0.414 |

| Cumulative teacher PL token frequency (log) | −2.402 * | −4.393 *** | −1.291 |

| Target PL schema reliability | −1.441 | −0.414 | −2.926 ** |

| Actual PL schema reliability | −14.443 *** | −6.682 *** | −15.21 *** |

| Target PL constructional iconicity | 2.854 ** | 2.994 ** | 10.913 *** |

| Actual PL constructional iconicity | −0.035 | −0.014 | −0.026 |

| Target PL morphotactic transparency | −6.507 ** | −3.628 *** | −7.679 *** |

| Actual PL morphotactic transparency | 0.039 | 0.019 | 0.036 |

| Target PL productivity | −4.111 *** | −3.165 ** | −5.322 *** |

| Actual PL productivity | −13.761 *** | −7.093 *** | −16.31 *** |

| Target PL total naturalness | −3.252 ** | −1.632 | −0.655 |

| Actual PL total naturalness | −13.78 *** | −0.006 | −12.26 *** |

| Models and Variables | (1) 1L1 | (2) 2L1 | (3) L2 |

|---|---|---|---|

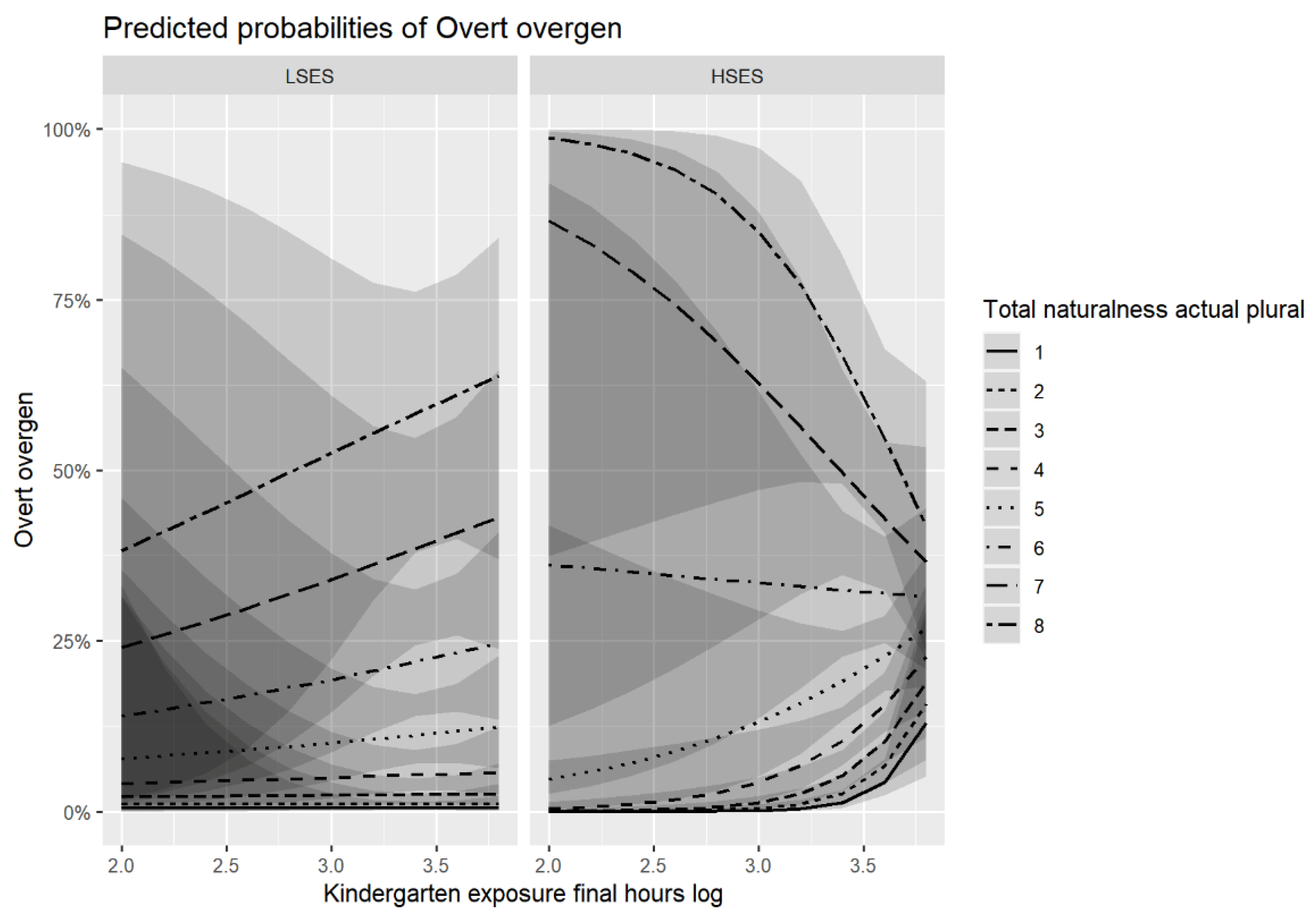

| Best overall model (significant variables in bold, asterisk in bold for significant interaction effects) | Actual PL constructional iconicity | SES * Datapoint + Target PL productivity | SES * Kindergarten exposure hours (log) * Actual PL total naturalness |

| Variables and variants of the best models (z values and significance levels) | Actual PL constructional iconicity (8.924 ***) | SESLSES (0.011), Datapoint 4 (0.012), Target PL productivity (−2.791 **), SESLSES * Datapoint 4 (−0.013) | SESLSES (2.387 *), Kindergarten exposure hours (log) (3.273 **), Actual PL total naturalness (3.286 **) SESLSES * Kindergarten exposure hours (log) (−2.582 *), SESLSES * Actual PL total naturalness (−2.395 *), SESLSES * Kindergarten exposure hours (log) * Actual PL total naturalness (2.542 *) |

| (1) Variables and Variants | (1) 1L1 | (2) 2L1 | (3) L2 |

|---|---|---|---|

| (2) Datapoint 4 | −1.928. | 2.596 ** | 1.397 |

| (3) SES LSES | −1.605 | −2.260 * | −3.619 *** |

| (4) Gender m | 0.022 | 1.066 | −0.826 |

| (5) Kindergarten exposure hours (log) | −1.591 | 2.714 ** | 3.671 *** |

| (6) Cumulative teacher PL type frequency (log) | −1.153 | 1.844. | 1.462 |

| (7) Cumulative teacher PL token frequency (log) | −1.356 | 2.230 * | 2.596 ** |

| (8) Target PL schema reliability | −0.935 | −1.817. | −3.789 *** |

| (9) Actual PL schema reliability | 5.314 *** | 2.857 ** | 7.562 *** |

| (10) Target PL constructional iconicity | −3.160 ** | 0.000 | 0.596 |

| (11) Actual PL constructional iconicity | 8.924 *** | 0.009 | 7.636 *** |

| (12) Target PL morphotactic transparency | −3.39 *** | −2.218 * | −3.638 *** |

| (13) Actual PL morphotactic transparency | 1.575 | −3.332 *** | −6.989 *** |

| (14) Target PL productivity | −7.247 *** | −2.563 * | −4.533 *** |

| (15) Actual PL productivity | −0.74 | −0.880 | 2.747 ** |

| (16) Target PL total naturalness | −6.032 *** | −2.133 * | −3.341 *** |

| (17) Actual PL total naturalness | 8.675 *** | 3.204 ** | 10.85 *** |

| Models and Variables | (1) 1L1 | (2) 2L1 | (3) L2 |

|---|---|---|---|

| Best overall model (significant variables in bold, asterisk in bold for significant interaction effects) | SES + Morphotactic transparency | Total PL naturalness | Constructional iconicity |

| Variables and variants of the best models (z values and significance levels) | SESLSES (−1.969 *), Morphotactic transparency (3.932 ***) | Total PL naturalness (2.165 *) | Constructional iconicity (−1.592) |

| Variables and Variants | (1) 1L1 | (2) 2L1 | (3) L2 |

|---|---|---|---|

| Datapoint 2 | 0.933 | −0.007 | −0.500 |

| Datapoint 3 | 1.893. | −0.006 | −0.012 |

| Datapoint 4 | 1.103 | −0.006 | 0.041 |

| SES LSES | −2.16 * | −0.312 | 1.083 |

| Gender m | −1.848. | 0.642 | 0.056 |

| Kindergarten exposure hours (log) | 0.643 | −0.004 | −0.936 |

| Cumulative teacher PL type frequency (log) | 1.176 | −0.454 | 1.257 |

| Cumulative teacher PL token frequency (log) | 1.114 | −0.776 | 1.706. |

| PL schema reliability | 1.563 | 1.408 | 0.829 |

| Constructional iconicity | 0.968 | 1.721. | −1.592 |

| Morphotactic transparency | 4.045 *** | 0.006 | −0.291 |

| Productivity | 2.384 * | 1.522 | −1.169 |

| Total PL naturalness | 3.118 ** | 2.165 * | −1.073 |

| Models and Variables | (1) 1L1 | (2) 2L1 | (3) L2 |

|---|---|---|---|

| Best overall model (significant variables in bold, asterisk in bold for significant interaction effects) | Actual PL total naturalness | Target PL total naturalness | Actual PL total naturalness |

| Variables and variants of the best models (z values and significance levels) | Actual PL total naturalness (−4.97 ***) | Target PL total naturalness (−1.533) | Actual PL total naturalness (−3.998 ***) |

| Variables and Variants | (1) 1L1 | (2) 2L1 | (3) L2 |

|---|---|---|---|

| Datapoint 2 | −0.427 | 0.003 | −0.017 |

| Datapoint 3 | −1.397 | 0.003 | 0.283 |

| Datapoint 4 | −0.755 | 0.000 | −0.116 |

| SES LSES | 1.253 | −0.531 | 0.172 |

| Gender m | 1.121 | −0.450 | −0.588 |

| Kindergarten exposure hours (log) | −2.125 * | 0.100 | 0.783 |

| Cumulative teacher PL type frequency (log) | −1.826. | −0.031 | −1.871. |

| Cumulative teacher PL token frequency (log) | −1.567 | 0.334 | −1.870. |

| Target PL schema reliability | 0.783 | −0.989 | −0.125 |

| Actual PL schema reliability | −3.909 *** | −0.947 | −4.606 *** |

| Target PL constructional iconicity | 1.764. | −1.515 | 1.375 |

| Actual PL constructional iconicity | −0.011 | −0.005 | −0.007 |

| Target PL morphotactic transparency | 0.147 | −0.005 | 0.264 |

| Actual PL morphotactic transparency | 0.017 | 0.005 | 0.010 |

| Target PL productivity | 1.732. | −1.244 | 2.168 * |

| Actual PL productivity | −3.983 *** | −1.245 | −0.010 |

| Target PL total naturalness | 1.820. | −1.533 | 2.172 * |

| Actual PL total naturalness | −4.97 *** | −1.523 | −3.998 *** |

| Models and Variables | (1) 1L1 | (2) 2L1 | (3) L2 |

|---|---|---|---|

| Best overall model (significant variables in bold, asterisk in bold for significant interaction effects) | SES + Actual PL productivity | Target PL total naturalness | SES + Actual PL productivity |

| Variables and variants of the best models (z values and significance levels) | SESLSES (1.471), Actual PL productivity (−4.611 ***) | Target PL total naturalness (−1.426) | SESLSES (−1.539), Actual PL productivity (−2.266 *) |

| Variables and Variants | (1) 1L1 | (2) 2L1 | (3) L2 |

|---|---|---|---|

| Datapoint 2 | −1.350 | 0.003 | 0.623 |

| Datapoint 3 | −1.663. | 0.000 | −0.662 |

| Datapoint 4 | −1.209 | 0.003 | 0.054 |

| SES LSES | 2.063 * | 0.006 | −1.440 |

| Gender m | 1.328 | −0.450 | 0.774 |

| Kindergarten exposure hours (log) | 0.612 | −0.094 | 0.765 |

| Cumulative teacher PL type frequency (log) | 0.183 | 0.655 | 0.778 |

| Cumulative teacher PL token frequency (log) | 0.097 | 0.738 | 0.183 |

| Target PL schema reliability | −2.515 * | −0.004 | −0.941 |

| Actual PL schema reliability | 0.627 | 0.004 | 0.278 |

| Target PL constructional iconicity | −1.965 * | −0.863 | 1.174 |

| Actual PL constructional iconicity | 0.805 | −0.040 | 1.368 |

| Target PL morphotactic transparency | −5.243 *** | −0.005 | 0.000 |

| Actual PL morphotactic transparency | −3.509 *** | −1.455 | −0.060 |

| Target PL productivity | −4.267 *** | −0.826 | −0.572 |

| Actual PL productivity | −4.673 *** | −0.266 | −2.091 * |

| Target PL total naturalness | −4.845 *** | −1.426 | −0.457 |

| Actual PL total naturalness | −3.915 *** | −0.761 | −1.083 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Korecky-Kröll, K.; Camber, M.; Uzunkaya-Sharma, K.; Dressler, W.U. German Noun Plurals in Simultaneous Bilingual vs. Successive Bilingual vs. Monolingual Kindergarten Children: The Role of Linguistic and Extralinguistic Variables. Languages 2024, 9, 306. https://doi.org/10.3390/languages9090306

Korecky-Kröll K, Camber M, Uzunkaya-Sharma K, Dressler WU. German Noun Plurals in Simultaneous Bilingual vs. Successive Bilingual vs. Monolingual Kindergarten Children: The Role of Linguistic and Extralinguistic Variables. Languages. 2024; 9(9):306. https://doi.org/10.3390/languages9090306

Chicago/Turabian StyleKorecky-Kröll, Katharina, Marina Camber, Kumru Uzunkaya-Sharma, and Wolfgang U. Dressler. 2024. "German Noun Plurals in Simultaneous Bilingual vs. Successive Bilingual vs. Monolingual Kindergarten Children: The Role of Linguistic and Extralinguistic Variables" Languages 9, no. 9: 306. https://doi.org/10.3390/languages9090306

APA StyleKorecky-Kröll, K., Camber, M., Uzunkaya-Sharma, K., & Dressler, W. U. (2024). German Noun Plurals in Simultaneous Bilingual vs. Successive Bilingual vs. Monolingual Kindergarten Children: The Role of Linguistic and Extralinguistic Variables. Languages, 9(9), 306. https://doi.org/10.3390/languages9090306