1. Introduction

Lexical items are widely accepted to fall into two categories: lexical and functional. Generally, lexical categories, such as nouns, verbs, and adjectives, have specific and concrete semantic content. In contrast, functional categories have abstract meanings and primarily serve grammatical roles, such as definiteness and number for nouns, tense for verbs, and degree for adjectives.

Corver and van Riemsdijk (

2001b, p. 1) describe functional categories as necessary in the surface structure to “glue the content words [i.e., lexical categories] together, to indicate what goes with what and how”. However, the boundary between these two categories remains unclear (see

Corver and van Riemsdijk 2001a). For example, prepositions are considered lexical in some studies (e.g.,

Chomsky 1970;

Stowell 1981) and functional in others (e.g.,

Baker 2003).

Even derivational affixes are no exception in this regard. Derivational affixes are normally considered functional items because, in a typical case, they bear category-changing or category-determining functions and their semantics is systematically limited. In other words, an affix changes or determines the syntactic category of its base, thereby relating the resulting word to the syntactic structure. For example, the English suffixes -

al, -

ance/-

ence, -

ation, -

ment, -

ing, and -

ure systematically produce abstract nouns from verbs, naming a relevant process or event (

Nagano 2011a, p. 95). The lack of either or both of these properties, namely a category-changing function and abstract semantics, can obscure the status of derivational affixes as functional categories. Prefixes clearly demonstrate such a lack: they do not determine the category of the word with them (

Nagano 2011b;

Togano 2022,

2024; contra

Kotowski 2021) and many, if not all, are semantically rich (e.g.,

counter- ‘against X’ and

multi- ‘more than one X’;

Nagano 2011a, p. 97). Given this fact, it is reasonable to classify (some) prefixes as lexical rather than functional categories (see

Nagano 2011a for relevant discussion).

Suffixes also present controversy regarding their morphological status. Previous studies have discussed the status of affixes from the perspective of their category-changing function. Within the framework of Distributed Morphology, for example,

Creemers et al. (

2018) address the issue by considering suffixes that appear to lack intrinsic categorial properties. For instance, -

ian in English can derive both adjectives and nouns, as in

reptile-

ianA and

librar-

ianN; similarly, -

aat in Dutch forms both adjectives and nouns:

accur-

aatA ‘accurate’ and

kandid-

aatN ‘candidate’ (

Creemers et al. 2018, pp. 46–47). These affixes challenge the assumption in Distributed Morphology that derivational affixes are functional as they realize the categorial head in syntax (

Marantz 1997;

Marvin 2003). Such affixes,

Creemers et al. (

2018) summarize, have led recent studies to propose that derivational affixes are generally roots (i.e., lexical morphemes) and that categorizers exist independently from affixes (

Lowenstamm 2015;

De Belder 2011).

Creemers et al. (

2018) themselves propose that while some derivational affixes are functional, others are lexical.

This study examines the status of suffixes from an alternative perspective, specifically based on their

semantic contributions to the words involving them. As stated above, V-to-N suffixes not only systematically derive abstract nouns but can also produce nouns referring to physical objects. In

Grimshaw’s (

1990) terms, they are called

complex event nominals (CENs) and

result nominals (RNs), respectively. The contrasts between CENs and RNs are shown in (1) and (2), where the two types of nominals are categorially identical but semantically different.

| (1) | a. | The examination of the patients took a long time. | |

| | b. | The examination was on the table. | |

| (2) | a. | The assignment of that problem too early in the course always causes problems. | |

| | b. | The assignments were too long. | |

| (Grimshaw 1990, pp. 49, 54, with stylistic modifications) |

The CENs in the (a) examples are like their base verbs in that they inherit argument structures and accept temporal modifiers (cf.

to examine the patients and

to assign that problem too early in the course). Here, the suffixes -

ation and -

ment function as nominalizers and maintain event readings of the relevant verbs. The RNs in the (b) examples are, in contrast, like genuine nouns with referential readings:

examination in (1b) refers to test papers with questions and

assignment in (2b) refers to what is assigned. Since both CENs and RNs can be derived by the same suffix from a single base verb, many studies have sought to address the relationships between CENs, RNs, and their base verbs (e.g.,

Grimshaw 1990;

Ito and Sugioka 2002;

Borer 2003;

Alexiadou and Grimshaw 2008;

Harley 2009;

Shimamura 2009,

2011;

Bloch-Trojnar 2013;

Lieber 2016;

Alexiadou 2020;

Nishiyama and Nagano 2020, chap. 2; among others) (see also papers in

Alexiadou and Rathert 2010;

Rathert and Alexiadou 2010; and

Alexiadou and Borer 2020). One approach is to attribute the contrasts between CENs and RNs to the nature of the suffixes used therein. Within the framework proposed by

Emonds (

2000), a morpheme-based syntactic approach to morphology,

Naya (

2018) proposes that a single derivational affix can serve both as a functional element, responsible for category changing, and as a lexical element, forming CENs and RNs, respectively. Given this proposal, the suffixes in (1a) and (2a) are functional, whereas those in (1b) and (2b) are lexical. Studying derivational suffixes along this line sheds new light on their morphological status. In fact,

Naya’s (

2018) proposal differs from the aforementioned studies in the framework of Distributed Morphology. Different as they are in details, these studies share the idea that a given affix behaves exclusively as either a functional or lexical morpheme. In contrast,

Naya’s (

2018) proposal allows

a single affix to behave both as a functional and a lexical morpheme, thereby broadening the discussion of the morphological status of derivational affixes.

With this background, this study aims to not only provide new data supporting the idea that a suffix can behave both as a functional and a lexical morpheme but also explore potential factors enabling a suffix to be a lexical morpheme. We focus on new words with -

ment in Present-Day English retrieved from the

Oxford English Dictionary Online (

2023). These words are appropriate for the current purpose for the following three reasons: First, they have not been sufficiently analyzed and thus may provide us with a new perspective on the discussion of the status of derivational affixes.

1 Second, and importantly, -

ment can be contrasted with -

ation: both are Latinate suffixes, and -

ation, but not -

ment, is productive in Present-Day English.

2 This contrast provides a good basis for discussing factors affecting the property of the lexical variant of an affix, as will be discussed in

Section 4.

The remainder of this article is organized as follows.

Section 2 introduces the theoretical framework of this study, the Bifurcated Lexical Model (

Emonds 2000), which allows an affix to behave as a lexical morpheme.

Section 3 examines new -

ment nouns retrieved from

OED (

2023) and reveals that problematic examples can be understood as a natural consequence of the lexical version of -

ment.

Section 4 discusses how productivity affects the behavior of -

ment by considering Japanese productive and non-productive suffixes and comparing -

ment nouns with -

ation nouns. Finally,

Section 5 provides the concluding remarks.

2. Theoretical Framework: The Bifurcated Lexical Model

The Bifurcated Lexical Model, the theoretical framework adopted in this article, was proposed by

Emonds (

2000). This model has two outstanding characteristics, which enable affixes to have a dual nature in principle. First, it hypothesizes that the lexicon consists of two subcomponents:

Dictionary and

Syntacticon. The Dictionary is an inventory of lexical categories, namely nouns, verbs, adjectives, and prepositions. The Syntacticon is an inventory of functional categories including derivational and inflectional affixes. The bifurcation of the lexicon leads to the second distinctive feature: Dictionary items and Syntacticon items are related to syntax in different ways via lexical insertion (

Emonds 2000, chap. 4). Based on

Emonds (

2000),

Section 2.1 demonstrates how this model differentiates between functional and lexical morphemes and how the two subcomponents of the lexicon interact with syntax.

Section 2.2 demonstrates how the model works by focusing on nominal suffixes in English.

2.1. Functional Categories and Lexical Categories in the Bifurcated Lexical Model

The Bifurcated Lexical Model differentiates between functional and lexical categories based on the feature specification in the lexical entry. The model assumes the features in (3), “where F are intrinsic cognitive syntactic features and

f are intrinsic semantic features […] of a selection head @ of category X” (

Emonds 2000, p. 43); +__F represents a subcategorization frame. Among the features in (3), the semantic features

f, which have no role in syntax and are thus purely semantic, are “present

only on the head categories = N, V, A, and P” (

Emonds 2000, p. 12). Thus, the verb

amuse has the

f feature but the agentive suffix -

er does not, as indicated in (4).

| (3) | | @, X, Fi, fj, +__Fk | (Emonds 2000, p. 43) |

| (4) | a. | amuze, V, f, +__ANIMATE | |

| | b. | er, N, ANIMATE, +<[V, ACTIVITY]__> | |

| (Emonds 2000, pp. 47, 157, with slight modifications) |

Importantly, this does not require all nouns, verbs, adjectives, and prepositions to have purely semantic features

f.

Emonds (

2000, p. 9) states that “

each [category] has a subset of say up to twenty or so elements fully characterized by cognitive semantic features F and entirely lacking purely semantic features f” (italics original).

3 Such subsets are called

grammatical or

semi-

lexical N, V, A, and P (

Emonds 2000, p. 9;

2001, p. 29). For example, grammatical verbs and nouns are as follows:

| (5) | a. | Grammatical V |

| | | be, have, do, get, go, come, let, make, say |

| | b. | Grammatical N |

| | | one, self, thing, stuff, people, other(s), place, time, way, reason |

| (Emonds 2000, p. 9) |

They are also known as light verbs or nouns. These grammatical subsets of N, V, A, and P are, unlike lexical members, stored in the Syntacticon. Accordingly, it can be said that the Dictionary is a list of items with purely semantic features f and the Syntacticon is a list of items without them.

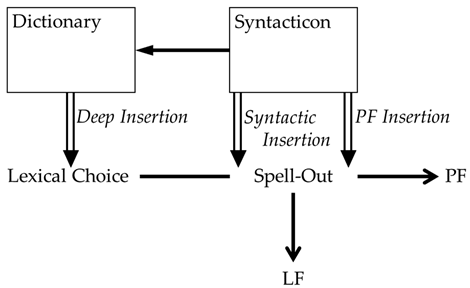

In the Bifurcated Lexical Model, the Dictionary and Syntacticon items also differ in terms of lexical insertion (

Emonds 2000, chap. 4). Whereas the Dictionary items are inserted only before a syntactic derivation, the Syntacticon items can undergo lexical insertion at two other stages. Overall, this system assumes three different types of insertion, as schematically represented in (6) (

Naya 2018, p. 19), which is a simplified version of

Emonds’ (

2000, pp. 117, 437) original representation. This system is called

Multi-

Level Lexical Insertion.

The three levels of lexical insertion can be outlined as follows: First, the Dictionary items undergo Deep Insertion, lexical insertion before a syntactic derivation, as represented by the leftmost downward arrow in (6). The Syntacticon items can also undergo Deep Insertion; they are not directly related to syntax but undergo it via the Dictionary, as indicated by the leftward arrow from the Syntacticon to the Dictionary. The next subsection elaborates how an item in the Syntacticon is inserted by Deep Insertion. In addition to Deep Insertion, Syntacticon items can undergo Syntactic Insertion, which is insertion during a derivation and prior to Spell-Out, and PF Insertion, which is insertion during a phonological derivation. PF Insertion is responsible for the insertion of inflectional suffixes, for example.

Among these three stages, Deep Insertion and Syntactic Insertion are relevant to our concern. The next subsection shows how this model forms CENs and RNs.

2.2. Forming Two Types of Nominals in the Bifurcated Lexical Model

Subsuming morphology under syntax (

Emonds 2000, chap. 3), the Bifurcated Lexical Model successfully captures the fact that suffixes such as -

ation and -

ment can form two types of deverbal nominals, namely CENs and RNs. As briefly described in

Section 1, CENs such as those in (7a) and (8a) are like verbs, whereas RNs like those in (7b) and (8b) can be regarded as genuine nouns.

| (7) | a. | The examination of the patients took a long time. |

| | b. | The examination was on the table. |

| (8) | a. | The assignment of that problem too early in the course always causes problems. |

| | b. | The assignments were too long. |

| | | (= (1), (2)) |

As a reflection of their nouniness, RNs can be pluralized as shown in (8b). The example in (9) indicates that such a plural form does not inherit the argument structure from the verbal base and cannot be the subject of the VP

take a long time due to the lack of the event structure.

To clarify the differences between CENs and RNs more closely, let us observe the following examples from

Emonds (

2000):

| (10) | a. | We protest the city’s constant development into the hills to attract industry. |

| | b. | We protest the city’s three {high-rise/treeless} developments with no schools. |

| | | (Emonds 2000, p. 152) |

The CEN in (10a) has an event reading and accepts the event modifiers

constant and

into the hills. The RN in (10b) refers to a physical entity, namely ‘a site or property that is being or has been developed, esp. into new residential accommodation’ (

OED 2023, s.v. development, sense 1.7.b). Accordingly, it can be pluralized and modified by

high-

rise and

treeless, which refer to physical objects. If these adjectives modify the CEN, the resultant expression is ungrammatical, as shown in (11a). The RN, in turn, cannot be modified by the event modifiers, as indicated in (11b).

4| (11) | a. | We protest the city’s {quick/*high-rise/*treeless} development to attract industry. |

| | b. | We protest the city’s three (*constant) developments (*into the hills). |

| | | (Emonds 2000, p. 152) |

Emonds’ (

2000, sct. 4.6) analysis explains the contrasting properties between CENs and RNs based on the different levels of lexical insertion of nominal suffixes. Specifically, -

ment undergoes Syntactic Insertion to form CENs (see (7a), (8a), (10a)) and Deep Insertion to form RNs (see (7b), (8b), (10b)). The framework of the Multi-Level Lexical Insertion refines the notion of

head(edness).

Emonds (

2000) proposes that the structural head is “entirely inert prior to the derivational moment which associates it with a lexical item” (

Emonds 2000, p. 155; see also

Emonds 2000, p. 128). In (8a), the nominal suffix -

ment, the structural head in

the assignment of that problem too early in the course, is inactive before Syntactic Insertion, and the verb

assign serves substantially as a head during the relevant syntactic computation. As a result,

assign maintains its event interpretation, thus introducing its grammatical argument

that problem and co-occurring with the temporal modifier

too early in the course. In this case, -

ment just changes a verb into a noun as a functional morpheme. In contrast, -

ment in RNs undergoes lexical insertion at the beginning of syntactic derivation (i.e., Deep Insertion) along with lexical morphemes. Accordingly, -

ment in (8b) is active as a nominal head throughout the derivation and thus

assignment behaves as a genuine noun.

To reflect the different levels of lexical insertion of -

ment in CENs and RNs,

Naya (

2018) proposes that -

ment (and other Syntacticon items) inserted at the beginning of the syntactic derivation (i.e., Deep Insertion) has a different status compared with when it is inserted via Syntactic Insertion. The motivation behind his proposal is that the Dictionary is a list of

lexical categories with rich semantic contents, namely those with purely semantic features

f; therefore, it is reasonable to assume that the Syntacticon items inserted via the Dictionary should also acquire some similar properties. In fact,

Emonds (

2000, p. 118) assumes that “a grammatical X

0 may simply take on an additional open class meaning via some feature

f”. For example, whereas

stuff is counted as a grammatical N, as shown in (5b), it can bear the meaning of ‘illegal drugs’, which is attributed to the feature

f assigned in the Dictionary (

Emonds 2000, p. 118). This applies to the other Syntacticon items: “items from the Syntacticon enter the syntactic derivation at an underlying level [i.e., via Deep Insertion] like open class items by virtue of their being linked to items and/or features

f in the open class Dictionary” (

Emonds 2000, p. 118).

Naya (

2018) applies this to derivational suffixes, specifically arguing that the suffix that is inserted via the Dictionary acquires the status of a

lexical morpheme by the assignment of

f features, meaning ‘thing/entity’ (

Naya 2018, pp. 146–47). Given this proposal, the feature specification of -

ment changes from (12a) to (12b) via Deep Insertion.

5| (12) | a. | -ment, N, +ABSTRACT, +<V__> |

| | b. | -ment, N, +ABSTRACT, +<V__>, f |

| | | (Naya 2018, p. 147) |

The noun

assignment in (8b) (RN) has -

ment of the (12b) type. Under the view that -

ment in (8b) (CEN) is a lexical morpheme with the meaning of ‘thing/entity’, this noun is formed by combining two lexical morphemes, which is equivalent to the process of compounding. Accordingly, as with ordinary compounds, the category of the RN as a whole is determined in accordance with the Right-Hand Head Rule. In addition, this noun has the modifier–modifiee relationship between the constituents where the verb

assign modifies the head -

ment. As a result,

assignment in (8b) can be interpreted as expressing ‘thing that is assigned’. This is in parallel with the interpretation of ordinary V-N compounds such as

kick-

ball, which means ‘a ball that is kicked’ (see

Naya 2018, sct. 5.5.2). The parallelism between RNs and V-N compounds is also evident in their incompatibility with the argument of the verbal element involved in the word. For example,

tax man cannot co-occur with the argument of

tax, as in (13).

6This depicts exactly the same pattern as the RN assignment in (9).

In this way,

Emonds’ (

2000) hypothesis reveals the possibility that a single affix can behave as a functional morpheme in some respects and as a lexical morpheme in others.

5. Concluding Remarks

This study examined the status of derivational affixes, questioning whether they are functional or lexical morphemes. Among several proposed approaches in previous studies, this study argues for the Bifurcated Lexical Model (

Emonds 2000), which sheds new light on the status of affixes in that it can approach the issue from affixes that coherently form words in a single category.

The distinctive characteristic of the Bifurcated Lexical Model is that it hypothesizes that the lexicon has two subcomponents: the Dictionary, an inventory of lexical morphemes, and the Syntacticon, an inventory of functional morphemes. This bifurcation allows a single affix to behave as a functional and a lexical morpheme (

Naya 2018). This dual status of an affix can successfully account for the behaviors of the new nouns caused by -

ment in Present-Day English. When it works as a functional morpheme with the role of category changing, it forms CENs from verbs. When it works as a lexical morpheme, it yields RNs from verbs. In addition, it forms complex nouns equivalent to nominal compounds by attaching to adjectives, nouns, and converted words. In this case, -

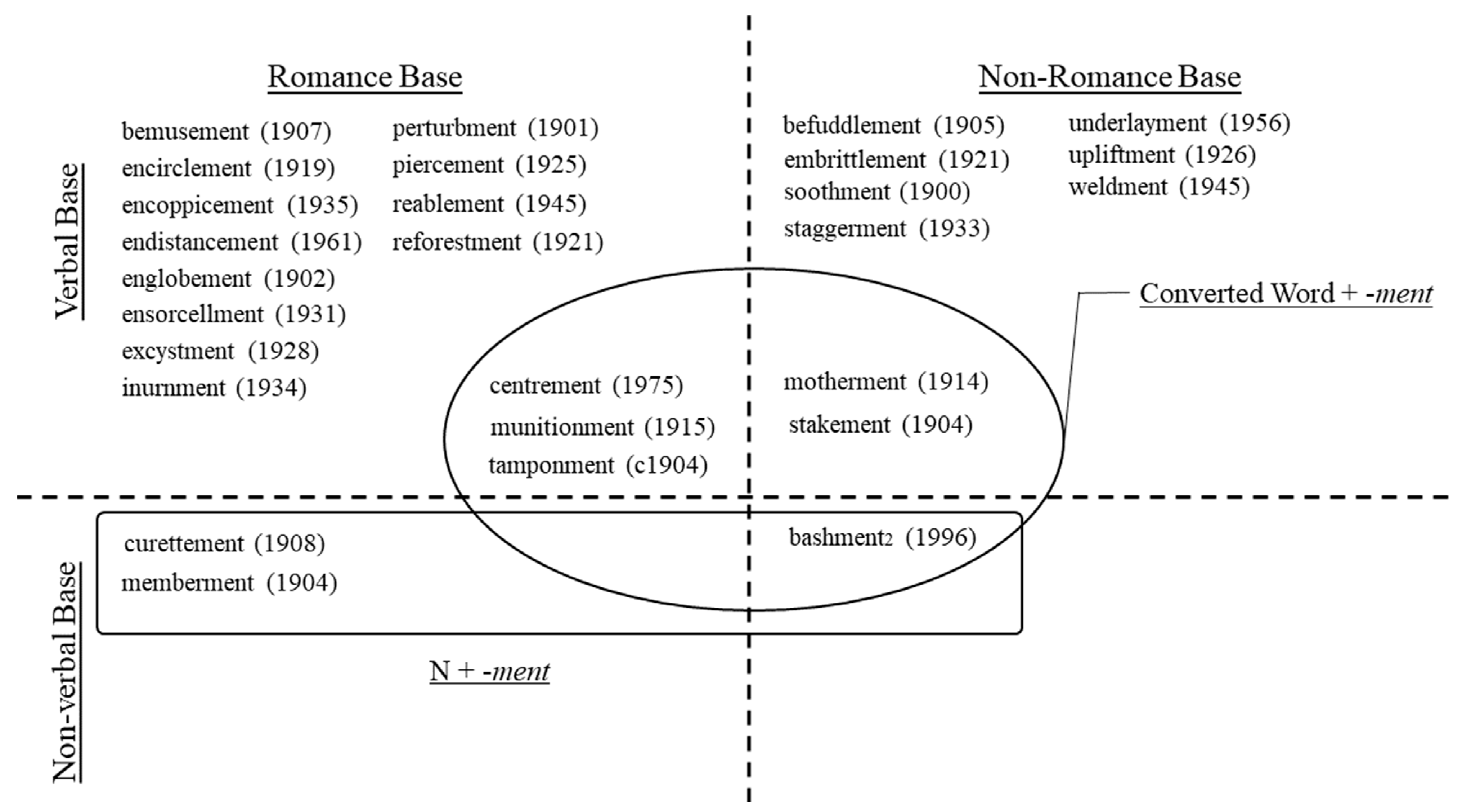

ment is assumed to have undergone the change in the Dictionary, where the subcategorization frame inherited from its original status as a functional morpheme is made optional.

This study also compared new nouns with -

ment and -

ation to examine the effects of their productivity on their selected elements.

Sugioka (

2005a et seq.) states, based on the two pairs of deadjectival noun forming suffixes (i.e., -

mi vs. -

sa in Japanese and -

ity and -

ness in English), that the opposite pattern can be observed in Japanese and English: in Japanese, the less productive suffix -

mi can extend the syntactic category of the base and attach to non-adjectival elements in Japanese, whereas, in English, the more productive suffix -

ness can be combined with non-adjectival elements. If we regard the extension of the base category as an indication of the lexical status of the involved suffix, Sugioka’s statement can be understood as follows: less productive suffixes in Japanese but more productive ones in English are more likely to behave as lexical morphemes. To examine whether this is valid cross-categorially (and cross-linguistically), this study compared nouns with -

ment and -

ation. Data from

OED (

2023) indicate that -

ation, the more productive suffix, attaches to nouns and adjectives more frequently. Combining this result and Sugioka’s observation, we concluded that high productivity enables a suffix to extend its base category, namely to behave as a lexical morpheme, when it originates in a functional morpheme (i.e., the English suffixes -

ity/-

ness and -

ment/-

ation). In contrast, -

mi in Japanese can attach to non-adjectival elements despite its low productivity because it is originally a lexical morpheme.

Having summarized the discussion thus far, it is pertinent to acknowledge the question that requires further inquiry. Given the proposal in

Section 3.1. that -

ment does not have the strict subcategorization frame when it undergoes Deep Insertion, the following question arises: Why are there a very limited number of denominal or deadjectival -

ment nouns? In other words, if it can freely attach to any category, there should be many more -

ment nouns based on nouns and adjectives.

20 However, there are only a few attested examples in

OED (

2023) (see

Table 1). This situation challenges the assumption that -

ment can be free from the subcategorization frame through the Dictionary. Although the optionality of the subcategorization frame indeed increases possible -

ment nouns, they do not necessarily occur as actual words. Whether a possible word actually occurs depends on several factors including extra-systemic ones (

Bauer 2001, p. 42) (see

Naya 2018, p. 145, fn. 9 for a related discussion). Here, it is worth paying attention to the recent phenomena related to -

mi ‘-ity’ in Japanese. As described in

Section 4.1, the nouns with this suffix are very limited in number. This situation also appears to be strange if -

mi is originally a lexical morpheme, as suggested in

Section 4.3. However, recent studies report that in expressions used on social media (e.g., Twitter, renamed X in June 2023), -

mi has come to be creatively attached to the elements with which it previously could not combine (see

Sugioka 2019, p. 51;

Nishiyama and Nagano 2020, p. 113 and studies cited therein). That is, only recently have (some) possible words with -

mi occurred as actual words. A factor behind the occurrence of such new words lies in the need to satisfy communicative requirements in the environment of social media. Likewise, the number of new -

ment nouns will be increased if some extra-systemic factors are given. What is important here is that the system allows -

ment to behave as a lexical morpheme, thereby giving it the potential to attach to various elements other than verbs.

In conclusion, viewed within the framework of the Bifurcated Lexical Model, new -ment nouns shed light on the status of affixes and the effects of their productivity, thereby contributing to a better understanding of word-formation processes in English.