Abstract

The main goal of this article is to examine in detail an area of the grammar where standard Romanian, a Balkan Sprachbund language of the Romance phylum, and the Romance dialects of Southern Italy (here we used the dialect of Ragusa, in South-East Sicily) appear to converge, namely differential object marking (DOM). When needed, additional observations from non-Romance Balkan languages were also taken into account. Romanian and Ragusa use a prepositional strategy for differential marking, in a conjunctive system of semantic specifications, of which one is normally humanness/animacy. However, despite these unifying traits, this paper also focuses on important loci of divergence, some of which have generally been ignored in the previous literature. For example, Ragusa does not easily permit clitic doubling and shows differences in terms of binding possibilities and positions of direct objects, two traits that set it aside from both Romanian and non-Romance Balkan languages; additionally, as opposed to Romanian, its prepositional DOM strategy cannot override humanness/animacy. The comparative perspective we adopt allow us to obtain an in-depth picture of differential marking in the Balkan and Romance languages.

1. Introduction

It has long been noticed that various Romance dialects of Southern Italy exhibit, at least on the surface, grammatical features that closely resemble phenomena independently seen in languages from the Balkan Sprachbund (Sandfeld 1930; Schaller 1975; Solta 1980; Manzini and Savoia 2005, 2018; a.o.). The taxonomy and more precise nature of such traits have been under investigation in a variety of approaches, be they descriptive typological or more formally oriented. An important question is whether these commonalities unite Southern Italo-Romance with the Balkan Romance phylum, extend to other language families in the Balkan Sprachbund or are superficial at best.

This paper contributes to this inquiry by examining differential object marking, an area of the grammar where standard Romanian (a Balkan Sprachbund language of the Romance phylum) and the Romance dialects of Southern Italy have been shown to converge, at least at a general level (Ledgeway 2000, 2023; Ledgeway et al. 2019; a.o.). As differential object marking is a phenomenon that gives rise to impressive variation not only cross-linguistically, but also intra-linguistically, the current work focuse on Romanian, as a major representative of Balkan Romance, which is compared to a Romance dialect of Southern Italy, the dialect of Ragusa in South-East Sicily (see Guardiano 2023 for further references).1 The results confirm, on the one hand, similarities between Romanian and Ragusa when it comes to the nature of differential object marking, for example, the use of a prepositional marker and sensitivity to humanness/animacy; on the other hand, various traits in the grammar of objects are present in Ragusa that distinguish it not only from Romanian, but also from non-Romance Balkan languages. Among these are the almost absence of clitic doubling (most instances of reduplication by pronominal reduced elements appear to be resumptive clitics, instead), the (although marginal) possibility to drop the differential marker under dislocation (as opposed to Romanian), or lack of correlation between differential marking and topicality (as opposed to non-Balkan Romance languages such as Albanian, Greek, or Bulgarian). As discussed in this paper, one source of such differences stems from the structural internal makeup of differentially marked objects (DPs with a [humanness] index in Ragusa, KPs in Romanian).

The examination of differential marking at a deep enough level thus reveal important finetuned hints into the nature of this phenomenon, its areal distribution, and its limits of variation; it also provides further insight into the problem of a shared basis between the Balkan Sprachbund and Romance languages of Southern Italy.

The structure of this paper is as follows. Section 2 starts with a brief introduction to differential object marking, narrowing down on its realization in the Balkan languages as well as the distinctions between clitic doubling and clitic resumption. Section 3 focuses on the Romanian strategy for the differential marking of objects and also emphasizes important differences between Romanian and non-Romance languages in the Balkans, which present robust strategies for differential object marking. Section 4 turns to a comparison between Romanian and Ragusa, illustrating their similarities and divergences. Section 5 is dedicated to reduplicating pronominal clitics in Ragusa; the patterns discussed indicate that clitic doubling seems to be non-existent or at most very restricted in the language. What looks like clitic doubling is, instead, more similar to clitic resumption. Section 6 focuses on the major differences observed between the relevant languages (more specifically, variation in the position and licensing of differentially marked objects) and evaluates their consequences at the theoretical level. Section 7 concludes this study.

2. Differential Object Marking: An Overview

It is not uncommon for the grammars of human languages to treat their direct objects in a non-uniform manner at the level of morphosyntax. In fact, many language families tend to organize their direct objects into separate classes, with an overwhelming tendency to signal the ones carrying specifications at the higher end of referentiality hierarchies via dedicated overt means. This split is at the core of the phenomenon known as differential object marking (DOM), which has been at the forefront of descriptive and formal research in modern linguistics (e.g., Silverstein 1976; Bossong 1985, 1991, 1998; Comrie 1989; Aissen 2003; Torrego 1998; Rodríguez-Mondoñedo 2007; López 2012; Baker 2015; Bárány 2018; Irimia 2023c).

A typical exemplification of splits in the class of objects comes from Turkish (Turkic). The direct object in (1)(b), interpreted as definite or specific, is differentially marked on the surface, through a suffix known in traditional grammars as the accusative case. It is contrasted to the direct object in (1)(a), which does not have such a morpheme and cannot refer to a specific entity. Also, it has been demonstrated (e.g., Kornfilt 1984, 1997; Bossong 1991, 1998; Enç 1991; von Heusinger and Kornfilt 2005; Öztürk 2005; Kamali 2015) that marked objects like kitabı in (1)(b) occupy a higher position than unmarked ones like kitap in (1)(a): for example, the differentially marked object can precede an indirect object (e.g., çoguğa in (1)(b), while the unmarked object cannot do so, therefore a sequence like kitap çoguğa would be ungrammatical in (1)(a).

| (1) | a. | Ali | çoguğ-a | kitap | ver-iyor. |

| Ali | child-dat | book | give-impf | ||

| Lit. ‘Ali is book giving to the child.’ | |||||

| b. | Ali | kitab-ı | çoguğ-a | ver-iyor. | |

| Ali | book-dom | child-dat | give-impf | ||

| ‘Ali is giving the book/a specific book to the child.’ | |||||

| (Turkish, Kamali 2015, ex., 4a,b adapted) | |||||

Differential object marking in Turkish appears to respect a broad definiteness/specificity scale as in (2), drawing the cut-off point right at the specific indefinites.

| (2) | Definiteness/specificity scale (adapted from Aissen 2003) |

| Pronoun > name > definite > specific indefinite > non-specific |

The splits seen in Turkish are only one of the possible semantic and morphosyntactic strategies employed by DOM cross-linguistically. The Balkan Sprachbund, a linguistic domain where differential object marking is particularly active (e.g., Bossong 1991; Kallulli 2000; Aissen 2003; Friedman 2008), exhibits various other morphosyntactic settings. Despite contact between Turkish and the Indo-European languages in this areal group, the latter show crucial differentiations. Importantly, the preferred morphosyntactic strategy does not employ an accusative case marker, and is, in fact, not uniform; more than one morphosyntactic mechanism can set aside various classes of direct objects, based on specifications such as givenness, specificity, definiteness, and animacy (see especially the contributions in Kallulli and Tasmowski 2008a). An important split is between non-Romance and Romance languages in the Balkans.

As discussed in the vast literature on the topic (see especially Miklosich 1862; Lopašov 1978; Assenova 1980, 2002; Berent 1980; Anagnostopoulou 1994a, 1994b, 2003, 2017; Leafgren 1997; Dimitrova-Vulchanova and Hellan 1999a, 1999b; Kallulli 2000, 2016; Franks and King 2000; Schick 2000; Schick and Beukema 2001; Tisheva and Dzonova 2002; Jaeger and Gerassimova 2002; Kallulli and Tasmowski 2008a; Tomić 2000, 2008; Friedman 2008; Krapova and Cinque 2008; Harizanov 2014; a.o.), clitic doubling is a robust differential object marking strategy in Balkan languages such as Greek, Albanian, Bulgarian, and Macedonian: these languages normally employ clitic doubling to signal direct objects which are interpreted as specific, [+given], etc.

By contrast, Romanian, as a representative of the Romance family, uses a prepositional strategy for DOM which is highly sensitive to animacy. In the next two subsections, some brief details on non-Romance clitic doubling are provided; they are necessary in order to better frame the Romance pattern, which is the main goal of this paper.

2.1. Clitic Doubling as a DOM Strategy in Non-Romance Balkan Languages

The doubling clitic is a reduced pronominal element, which co-occurs with its associate (e.g., Kayne 1975; Strozer 1976; Rivas 1977; Lopašov 1978; Jaeggli 1982; Borer 1981, 1984; Rivero 1994; van Riemsdijk 1999; Linstedt 2000; Kallulli 2000, et subseq.; Tomić 2004, 2006; Friedman 2008; Kochovska 2010, 2011; Beukema and den Dikken 2000; Preminger 2009); the latter can be a full pronoun, a referential DP, or even a clause. If in languages like Albanian or Macedonian, both direct and indirect objects must be obligatorily clitic doubled in certain contexts (Lopašov 1978; Kallulli 2016), there is also the Greek or Bulgarian type, which is characterized by a higher degree of optionality (Anagnostopoulou 1994a, 1994b, 2003, 2017; Kallulli 1999, 2000; Guentchéva 2008; Krapova and Cinque 2008; a.o.). Given that we are interested in differential object marking (which normally excludes indirect objects), we will restrict our attention just to the general properties of clitic doubling of direct objects.

An undisputed property of clitic doubling is that it gives rise to various interpretive effects. In the clitic doubling Balkan languages, the vast literature has pointed out numerous correlates on the semantics and pragmatics side; a partial list of features associated with clitic doubled direct objects includes individuation, topic worthiness/topicality, prominence, definiteness (especially for Greek, Anagnostopoulou 1999), or Macedonian (Tomić 2000, 2004, 2008), specificity, familiarity, presuppositionality, referential stability, non-novelty, [+given], and D-linking (Kallulli 1999; Kallulli and Tasmowski 2008b, p. 20). In the example below from Albanian, the definite direct object is doubled by an accusative clitic and would be felicitous only in a context in which the definite inanimate is not novel in the discourse.2

| (3) | E | botoi | librin | më | në | fund. |

| cl.acc.3sg3 | published | book.def.acc | at | long | last | |

| ‘She/published the book (at long last). | (Albanian, Kallulli 2016, 5a, p. 164) | |||||

2.2. Clitic Doubling and Clitic Resumption

Most, if not all, languages that grammaticalize doubling clitics provide evidence that these elements do not act as a uniform category. Importantly, a crucial difference is established between two classes of phenomena, more precisely clitic doubling and clitic resumption. These distinctions encompass, but are not restricted to, the prosody—that is, a heavy intonational break separating the dislocated object that is subsequently resumed by a clitic in the main clause.

To better illustrate the difference between clitic doubling and clitic resumption, we can provide some discussion with respect to Bulgarian (Balkan Slavic); in this language, it has been shown that some types of postverbal direct objects must be obligatorily clitic doubled, despite the otherwise optional nature of clitic doubling in the language. These are mainly accusative experiencers of psych and physical perception predicates or direct objects of various types of modal or existential verbs (see especially Krapova and Cinque 2008 for a complete list and for the relevant examples), which trigger obligatory clitic doubling4, regardless of whether the direct object DP is novel in the discourse, carries nuclear stress (as is characteristic of focus, which normally blocks clitic doubling), and is not separated from the main clause by a heavy intonational break.

When it comes to dislocated objects (to the left or to the right), the doubling clitic appears to have a slightly distinct function, being regulated by constraints related to topicality, specificity, or the presence of a [+given] feature. In these configurations, the clitic functions as resumptive, and when the right conditions are met, it becomes obligatory even with those predicates that do not require clitic doubling on their in situ direct objects.5

It seems, thus, that two important distinctions must be made for Bulgarian: (i) between objects that involve dislocation and presuppose a heavy intonational break under clitic resumption and objects that do not involve dislocation and a heavy intonational break but can still be doubled by a clitic; (ii) in the latter class, there can be objects where a clitic double is obligatory regardless of information structure and contexts where there is a correlation between a doubling clitic and a [+given] feature. These two latter subtypes do not involve dislocation and a sharp intonational break, and thus there can be instances of genuine clitic doubling involving optionality. In any case, the dislocation signaled prosodically presents important differences and must be set aside as it involves a resumptive clitic. In this work, we have taken into consideration the prosodic effects, in the sense of a heavy intonational break, and not the variable of optionality. In fact, as we will also see in Romanian, there can be instances in which clitic doubling is optional, even though they are clearly not contexts of clitic resumption based on dislocation (because, among others, the clitic double is still dependent on humanness, as opposed to clitic resumption which does not have this restriction).6

Differences between clitic doubling and clitic resumption are clear in another Balkan language, namely Greek. As discussed by Anagnostopoulou (1994a, 1994b), clitics resuming left dislocated objects are possible with indefinites and not only with definites; in fact, non-dislocated indefinites might need special conditions to be clitic doubled in Greek (see also Kazazis and Pentheroudakis 1976). In turn, Tomić (2008) and Kochovska (2010, 2011) have discussed important distinctions between clitic doubling and clitic resumption in Macedonian. In Table 1, we include a summary of the most important differences between clitic resumption and clitic doubling.

Table 1.

Clitic resumption and clitic doubling.

3. Differential Object Marking in Romanian

Romanian is well known for its complex patterns of differential object marking (Farkas 1978; Dobrovie-Sorin 1994; Cornilescu 2000; von Heusinger and Onea 2008; Tigău 2010, 2011; Irimia 2020a, 2020b, 2021, 2023b, 2023c; Hill and Mardale 2021; a.o.), which set it aside in the larger Balkan setting, assimilating it to the Romance languages (e.g., Niculescu 1965; Sornicola 1997; Rohlfs 1971, 1973; Roegiest 1979; Bossong 1991, 1998; Torrego 1998; Aissen 2003; Fiorentino 2003; Leonetti 2003, 2008; Ormazabal and Romero 2007, 2013; Rodríguez-Mondoñedo 2007; Escandell-Vidal 2009; Iemmolo 2010; López 2012; Kabatek et al. 2021; Gravely 2021a, 2021b; Irimia and Pineda 2022; Ledgeway 2023; Zdrojewski 2023; a.o.). The differences are not only morphosyntactic but also affect the interpretive side.

First, the primary morphological means is not clitic doubling (as in non-Romance Balkan, see the example in (3) above from Albanian), but a preposition-like element, namely pe, homophonous with the locative ‘on’ in modern Romanian, as shown in (4)7. Secondly, notions related to topicality, definiteness, or specificity that are at work in non-Romance Balkan languages are not the regulating factors for Romanian DOM; humanness/animacy instead plays an important role (Farkas 1978; Dobrovie-Sorin 1994; Cornilescu 2000; von Heusinger and Onea 2008; Tigău 2010, 2011; Irimia 2020a, 2020b, 2021, 2023b, 2023c; Hill and Mardale 2021; a.o.), as evidenced by the contrast between (5)(a) and (b), (6)(a) and (b), and (7)(a) and (b). The inanimate object in (5)(b), (6)(b), and (7)(b) does not permit differential marking, regardless of whether it has a specific or a non-specific interpretation and regardless of whether it is [+given].

| (4) | Ai | lăsat | cărţile | pe | masă. | |

| have.2sg | left | book.f.pl.def.f.pl | on | table | ||

| ‘You left the books on the table.’ | (Romanian) | |||||

| (5) | a. | Au | invitat | *(pe) | cineva | (foarte important) | la | nuntă. | |

| have.3pl | invited | dom | somebody | (very important) | at | wedding | |||

| ‘They have invited somebody very important to the wedding.’ | |||||||||

| b. | Vor | (*pe) | ceva | anume, | mai | precis | diamantul | ||

| want.3pl | dom | something | certain | more | precise | diamond.def.n.sg | |||

| din | vitrină | (de care | ţi-am | zis | deja). | ||||

| from | window | (of which | cl.dat.2sg-have.1 | told | already) | ||||

| ‘The want something precisely, more specifically the diamond in the shop window (which I already told you about).’ | (Romanian) | ||||||||

As another exemplification, the contrast in (6) below shows that the inanimate object in (6)(b) is not grammatical with the pe marker, regardless of whether it is interpreted as given in a context or not.

| (6) | a. | Am | văzut(-o) | pe | fata | frumoasă. | |

| have.1 | seen(-cl.acc.3f.sg) | dom | girl.def.f.sg | beautiful.f.sg | |||

| ‘I saw the beautiful girl.’ | |||||||

| b. | Am | văzut(*-o) | (*pe) | floarea | frumoasă | (pe | |

| have.1 | seen(-cl.acc.3f.sg) | dom | flower.def.f.sg | beautiful.f.sg | (dom | ||

| care | mi-ai | arătat-o | şi | ieri). | |||

| which | me.dat-have.2sg | shown-cl.acc.3f.sg | and | yesterday | |||

| ‘I saw the beautiful flower (that you also showed me yesterday).’ | |||||||

In turn, example (6)(a) shows another property of Romanian grammar, namely clitic doubling of objects; however, only certain types of pe objects can be clitic doubled and only the accusative form of the clitic is admissible. This dependence of clitic doubling on differential marking sets aside Romanian in the larger Balkan Sprachbund.

| (7) | a. | Am | adus-o | pe | fata | colegilor | |

| have.1 | brought-cl.acc.3f.sg | dom | girl.def.f.sg | colleague.m.pl.gen.m.pl | |||

| mei | la | noi. | |||||

| my.m.pl | at | we | |||||

| ‘I brought my colleagues’ daughter to our place.’ | |||||||

| b. | Am | adus(*-o) | (*pe) | cartea | nouă. | ||

| have.1 | brought-cl.acc.3f.sg | dom | book.def.f.sg | new.def.f.sg | |||

| ‘I brought the new book.’ | (Romanian) | ||||||

A non-trivial challenge is that, despite the prominence of animacy, Romanian DOM configurations cannot be unified under this trait. There are numerous contexts where animacy is overridden; moreover, as we will see, there are also many cases where another cross-linguistic correlate of DOM, namely specificity, does not seem to play a role either. What Romanian illustrates instead are patterns that are typical of so-called ‘conjunctive DOM’ systems (Aissen 2003); at a purely descriptive level, the presence of more than one feature appears to be necessary for the special objects to receive dedicated marking. Traditionally, it is assumed that both the animacy and the definiteness/specificity scales are necessary:

| (8) | Conjunctive DOM in Romanian: |

| (i) | Animacy/person: 1/2 > 3 > proper name > human > animate > inanimate (Aissen 2003) |

| (ii) | Specificity/definiteness: pronoun > name > definite > specific indefinite > non-specific (see also (2); Aissen 2003; Comrie 1989; a.o.) |

For expository purposes, the presentation of Romanian prepositional DOM will take into account obligatory, optional, and ungrammatical contexts, following the simplified taxonomy in Irimia (2023b), enriched with various other examples (Niculescu 1965; Gramatica limbii române—Gramatica Academiei 1966; Farkas 1978; Dobrovie-Sorin 1994; Cornilescu 2000; GRL 2005/2006; von Heusinger and Onea 2008; Tigău 2010, 2011; GBRL 2010/2016; Pană Dindelegan 2013; Irimia 2020a, 2020b, 2021, 2023b, 2023c; Hill and Mardale 2021; a.o.). Subsequently, unification will be attempted in terms of configurational traits.

3.1. Obligatory Prepositional DOM

The class of obligatory DOM groups together not only contexts where humanness/animacy is relevant, but also various direct objects where animacy is overridden. As such, in this group, one can find both lexical DPs and various types of quantifiers. For example, tonic personal pronouns are ungrammatical without DOM, regardless of person specification. Moreover, clitic doubling is obligatory too in these contexts, as shown in 9(a). Proper names and kinship nouns with possessors are another category that requires the obligatory presence of the differential marker, and for many speakers, also clitic doubling; some examples are in (9)(b) and (c). DPs that contain highly referential nominals or honorifics, especially if accompanied by demonstratives, are equally ungrammatical without the differential marker (and clitic doubling); an example is in 9(d). Another important category groups together the animate direct objects of various pain and psych predicates, such as hurt, interest, etc., as in (9)(e) and (f).8 The differential objects of pain predicates also need obligatory clitic doubling.

| (9) | a. | *(M)-au | ajutat | *(pe) mine | şi | *(le)-au | |||

| cl.acc.1sg-have.3pl | helped | dom me.acc | and | cl.acc.3f.pl-have.3pl | |||||

| ajutat | şi | *(pe) | ele. | ||||||

| helped | and | dom | they.f | ||||||

| ‘They helped me and they helped them too.’ | |||||||||

| b. | (O) | apreciez | foarte | mult | *(pe) | Adriana. | |||

| cl.acc.3f.sg | appreciate | very | much | cl.acc.3f.sg | Adriana | ||||

| ‘I appreciate Adriana very much.’ | |||||||||

| c. | (O) | ador | *(pe) | mama/sora/ | |||||

| cl.acc.3f.sg | adore | dom | mother.def.f.sg/sister.def.f.sg/ | ||||||

| bunica | mea. | ||||||||

| grandmother.def.f.sg | my.f.sg | ||||||||

| ‘I adore my mother/sister/grandmother.’ | |||||||||

| d. | Preşedintele | (ȋl) | va | invita | *(pe) | ||||

| president.def.m.sg | cl.acc.3m.sg | fut.3sg | invite.inf | dom | |||||

| domnul | acela | la | recepţie. | ||||||

| gentleman.def.m.sg | that.def.m.sg.aug9 | at | reception | ||||||

| ‘The president will invite that gentleman to the reception.’ | |||||||||

| e. | *(O) | doare | mâna | *(pe) | fată. | ||||

| cl.acc.3f.sg | hurt.3sg | hand.def.f.sg | dom | girl | |||||

| ‘The girl’s hand hurts.’ (Lit. ‘The hand hurts the girl.’) | |||||||||

| f. | Aceste | rezultate | (ȋi) | interesează | pe | politiceni. | |||

| this.n.pl | result.n.pl | cl.acc.3m.pl | interest.3 | dom | politician.pl | ||||

| ‘These results interest politicians.’ | (Romanian) | ||||||||

Let us turn now to the quantifiers. On the one hand, there are quantificational elements with a humanness/animacy restriction, for example wh-words, such as cine ‘who’, illustrated in (10), the negative [+human] nimeni ‘nobody’ in (10)(b), or cineva (‘somebody’) with its variants, as in (10)(c) or (5)(a). These quantifiers, even if requiring obligatory differential marking, are not possible with clitic doubling.

| (10) | a. | *(Pe) | cine | (*l-)ai | auzit? | |

| dom | who | cl.acc.3m.sg-have.2sg | heard | |||

| ‘Who have you heard?’ | ||||||

| b. | Nu | (*l-)au | salutat | pe | nimeni. | |

| neg | cl.acc.3m.sg-have.3pl | greeted | dom | nobody | ||

| ‘They haven’t greeted anybody.’ | ||||||

| c. | Trebuie să | (*ȋl) | angajăm | pe | altcineva. | |

| must | sbjv cl.acc.3m.sg | hire.1pl | dom | other somebody | ||

| ‘We must hire somebody else.’ | (Romanian) | |||||

The other subclass encompasses the quantifiers that require obligatory DOM, irrespective of animacy. The D-linked element care (‘which’) fits here, together with various nominal ellipsis contexts headed by demonstratives, possessors, the universal quantifier, etc. Some relevant examples are in (11)(a)–(e). The relative pronoun, when tracking direct objects, also falls into this group; it is considered obligatory in descriptive grammars, and dropping the differential marker is strongly frowned upon. As opposed to the quantifiers in (10), DOM categories that are insensitive to animacy normally need clitic doubling or are definitely better with clitic doubling for most speakers.

| (11) | a. | *(Pe) | care | (bărbat/autobuz) | *(l)-ai | văzut? | ||

| dom | which | man/bus | cl.acc.3m/n.sg-have.2sg | seen | ||||

| ‘Which man/bus did you see?’ | ||||||||

| b. | (L)-au | examinat | pe | acela. | ||||

| cl.acc.3m.sg-have.3pl | examined | dom | that.m/n.sg.aug | |||||

| ‘They examined that one.’ | [animate or inanimate] | |||||||

| c. | (Le) | acceptăm | pe | toate. | ||||

| cl.acc.3f/n.pl | accept.1pl | dom | all.f/n.pl | |||||

| ‘We accept them all.’ | [animate or inanimate] | |||||||

| d. | (L-)au | furat | (pe) | al meu. | ||||

| cl.acc.m/n.sg-have.3pl | stolen | dom | lk.def.m/n.sg | |||||

| ‘They have stolen mine.’ | [animate or inanimate] | |||||||

| e. | (L)-aş | prefera | (pe) | cel10 | ȋnalt. | |||

| cl.acc.m/n.sg-cond.1sg | prefer.inf | dom | cel.m/n.sg | tall.m/n.sg | ||||

| ‘I’d prefer the tall one.’ | [animate or inanimate] | |||||||

| f. | Fata | *(pe) | care | ai | ajutat-*(o). | |||

| girl.def.f.sg | dom | which | have.2sg | helped-cl.acc.3f.sg | ||||

| ‘the girl that/whom you helped.’ | (Romanian) | |||||||

When it comes to DPs with overt lexical material (as opposed to elliptical DPs), the prepositional marker is, if not obligatory, at least strongly preferred in certain types of comparative constructions (generally equatives) or when numerals and other categories need to be individuated under citation. More recently, the use of the differential marker has been extended to sports teams in object position. Some examples are in (12).

| (12) | a. | Îşi | preţuieşte | prietenul | ca *(pe) | un | dar. | ||||

| cl.dat.poss.3sg | value.3sg | friend.def.m.sg | as dom | a.n.sg | gift | ||||||

| ‘She/he values his/her friend as a (she/he values a gift).’ | |||||||||||

| b. | O | găină ȋngrijeşte | trei | pisoi | abandonaţi | ||||||

| a.f.sg | hen | care for.3sg | three | kitten.m.pl | abandoned.m.pl | ca *(pe) | proprii | pui. | |||

| as | dom | own.m.pl | chick.m.pl | ||||||||

| ‘A hen takes care of three abandoned kittens as of her own chicks.’11 | |||||||||||

| b. | L-ai | uitat | *(pe) | trei/a. | |||||||

| cl.acc.3m.sg-have.2sg | forgotten | dom | three/a | ||||||||

| ‘You forgot the three/the a.’ (for example, in a text) | |||||||||||

| c. | Au | reuşit | să | o | bată | *(pe) | Lazio Roma. | ||||

| have.3pl | succeeded | sbjv | cl.acc.3sg.f | beat.sbjv3 | dom | Lazio Roma | |||||

| ‘They managed to beat Lazio.’ | (Romanian) | ||||||||||

3.2. Optional Prepositional DOM

There are also various contexts in which differential marking has been traditionally described as optional. Animate definites are found in this class; in Romanian, both the sentence in (13)(a) containing an unmarked definite, and the sentence in (13)(b) with a differentially marked object interpreted as a definite, are grammatical. It is moreover not clear whether the two sentences differ in terms of specificity or whether there are (deep) interpretive distinctions between them.

| (13) | a. | Am | văzut | fetele. | ||

| have.1 | seen | girl.f.pl.def.f.pl | ||||

| ‘I saw the girls.’ | ||||||

| b. | (Le)-am | văzut | pe | fete(*le). | ||

| cl.acc.f.pl-have.1 | seen | dom | girl.f.pl | |||

| ‘I saw the girls.’ | (Romanian) | |||||

Note that in modern Romanian, there is a co-occurrence restriction between the differential marker and the overt definite suffix on unmodified objects (see the extensive bibliography in Irimia 2023a or Hill and Mardale 2021). As a result of this restriction, the overt definite suffix is not possible in (13)(b); however, the object must be interpreted as a definite and cannot obtain the reading of a bare nominal. In fact, as can be seen in (19)(a), bare nominals, which in Romanian are restricted to existential interpretations, are not grammatical under differential marking.

Another context of optionality comes from the quantifier domain, and it appears to signal the more precise distinction between weak and strong quantifiers. When the differential marker is present, a specific interpretation is obtained; in turn, the unmarked quantified object gets an existential reading. This is seen in the contrast in (14). Other quantifiers in this class are niciun/niciuna ‘no.m/f.sg’, vreun/vreuna (‘any.m/f.sg’, polarity sensitive)12, puţini/puţine (‘few.m/f.pl’).

| (14) | a. | Cunosc | mulţi | scriitori. | ||

| know.1sg | many.m.pl | writer.m.pl | ||||

| ‘I know many writers.’ | ||||||

| b. | Îi | cunosc | pe | mulţi | scriitori. | |

| cl.acc.3m.pl | many.m.pl | dom | many.m.pl | writer.m.pl | ||

| ‘I know many specific writers.’ | (Romanian) | |||||

The alternation seen with the numerals is related to partitivity. In 0, when the differential marker is present, the two books are interpreted as specific, and the set is presupposed to be known. The unmarked numeral is interpreted as an existential.

| (15) | Nu | (le)-am | citit | decât | (pe) | două | dintre | aceste | lucrări. |

| neg | cl.acc.3f.pl-have.1 | read | only | dom | two | from | this.f.pl | work.f.pl | |

| ‘I have read only two of these works.’ | (Romanian) | ||||||||

The contrast in specificity is also salient with indefinites. As such, an interpretive difference is clear between (16)(a) and (16)(b); the latter, which contains a differentially marked object, can refer to a specific woman.

| (16) | a. | Ion | iubeşte | o | femeie. | ||

| Ion | love.3sg | a.f.sg | woman | ||||

| ‘Ion loves a woman.’ | |||||||

| b. | Ion o | iubeşte | pe | o | femeie | anume | |

| Ion cl.acc.3f.sg | love.3sg | dom | a.f.sg | woman | certain | ||

| ‘Ion loves a certain woman.’ | (Romanian) | ||||||

However, despite this contrast, there are contexts in which a differentially marked indefinite can be associated to a non-specific reading. This is, in fact, not surprising, given the numerous exceptions seen with marked objects in Romanian and cross-linguistically. A relevant example is given in (17).

| (17) | Poţi | să | îl | rogi | pe | un | om | oarecare |

| can.2sg | sbjv | cl.acc.3m.sg | ask.2sg | dom | a.m.sg | man | no-matter-who | |

| de pe stradă. | ||||||||

| of on street | ||||||||

| ‘You can ask any random man/person on the street.’ | (Romanian) | |||||||

This indicates not only that a better understanding of the composition of specificity is necessary but also that differential marking is regulated by more abstract constraints, going beyond specificity, referentiality, and animacy. Also, it has been noticed in a variety of languages that DOM cannot be unified under purely semantic features (see especially López 2012). Romanian DOM is, thus, no exception.

3.3. Ungrammatical Prepositional DOM

Turning to the contexts in which differential marking results in ungrammaticality, these comprise at least four types. First, there are the inanimate objects that have overt lexical material, as in (7)(b). Then, there are the non-elliptical quantifiers that are restricted to inanimates, such as nimic (‘nothing’) or ceva (‘something’) in (18); these are to be contrasted with nimeni (‘nobody’) or (alt)cineva (‘somebody else’), shown above in (10).

| (18) | a. | Nu | am | văzut | (*pe) nimic | |

| neg | have.1 | seen | dom nothing | |||

| ‘I have seen nothing.’ | ||||||

| b. | Am | văzut | (*pe) ceva/altceva | |||

| have.1 | seen | dom something/other something | ||||

| ‘I saw something/something else.’ | (Romanian) | |||||

Thirdly, bare nominals are excluded from differential marking, regardless of animacy. As such, the existential predicate have in 19(a) that prefers bare nouns is not grammatical with marked objects. If differential marking is added to this context, the existential interpretation is removed, and what is entailed is a momentaneous eventuality of possessing, confined to a certain temporal duration. Moreover, the presupposition of a set of girls known in the discourse is introduced, as in (19)(b).

| (19) | a. | Maria are | (*pe) | fete, | iar | Ion (*pe) | băieţi. |

| Maria have.3sg | dom | girl.f.pl | and | Ion dom | boy.m.pl | ||

| ‘Maria has girls and Ion boys.’ | |||||||

| b. | Maria le | are | pe | fete. | |||

| Maria cl.acc.3f.pl | have.3sg | dom | girl.f.pl | ||||

| ‘Maria has the specific girls.’ (with her, at her place) | (Romanian) | ||||||

Fourthly, certain types of (cognitive and stative) predicates with inanimate subjects are not grammatical with differential marking. We give here two examples modeled after Torrego (1998) and Cornilescu (2000).

| (20) | a. | Opera | (*ȋi) | cunoaşte | (*pe) | mulţi | fani. |

| opera.f.sg | cl.acc.3m.pl | know.3sg | dom | many.m.pl | fan.m.pl | ||

| ‘The opera knows many fans.’ | |||||||

| b. | Situaţia | dificilă | (*ȋl) | cerea | (*pe) | ||

| situation.def.f.sg | difficult.f.sg | cl.acc.3m.pl | demand.impf.3sg | dom | |||

| un | lider | foarte | puternic. | ||||

| a.m.sg | leader | very | strong.m.sg | ||||

| ‘The difficult situation demanded a very strong leader.’ | (Romanian) | ||||||

Lastly, the differential marker is ungrammatical in some types of non-finite predicates; the so-called supine, constructed from a nominalization and preceded by the prepositional marker de, is a case at hand. For many speakers, the differential marker (and thus clitic doubling) are not easily possible in examples such as (21)(a) or (21)(b).

| (21) | a. | (*Îi) | am | de | spălat | (*pe) copii. | |

| cl.acc.3m.pl | have.1sg | sup | wash.nomz | dom | child.m.pl | ||

| ‘I have to wash the children.’ | |||||||

| b. | (*Îi) | am | de | vizitat | (*pe) | părinţi. | |

| cl.acc.3m.pl | have.1sg | sup | visit.nomz | dom | parent.m.pl | ||

| ‘I have to visit the parents.’ | (Romanian) | ||||||

3.4. Romanian DOM: Unifying Traits

As is clear from these examples, using a description of the Romanian differential marker in terms of scales is not the right direction to take. Violations of both the animacy and the referentiality scales are common; in certain contexts, special marking applies regardless of animacy (the nominal ellipsis contexts in (11)), while in others, specificity does not play a role (for example, the animate quantifiers in (10)). This raises the question of how differential marking can be unified; an explanation according to which marked objects are associated with a higher, overt position, as seen in Turkish (and in many other languages of this type, Baker 2015), does not seem to be the answer either, as Romanian differentially marked objects do not raise overtly and, in normal conditions, cannot precede V (see also Hill and Mardale 2021 for other remarks against raising when it comes to Romanian DOM).

Another traditional analysis for differential object marking in Romanian is the one in terms of Kayne’s Generalization (Jaeggli 1982; Dobrovie-Sorin 1994), which links the prepositional marker to the presence of the clitic double.13 In these accounts, the differential marker acts as a last resort Case-assigning mechanism to avoid a violation of the Case Filter (Chomsky 1981)14—as the clitic double ‘absorbs’ Case from V, the lexical nominal would be left caseless. Given that in Romanian there are numerous instances in which clitic doubling is, in fact, ungrammatical with various types of differentially marked objects (for example, differentially marked quantifiers with an animacy restriction as in (10), this analysis does not give the right results.

We can also investigate the hypothesis that links the prepositional differential marker to an anti-incorporation mechanism in the grammar, as assumed in numerous works on DOM (see especially López 2012). It has been conclusively demonstrated for a wide range of language families (e.g., Öztürk 2005; Baker and Vinokurova 2010; Lyutikova and Pereltsvaig 2015; Levy-Forsythe and Kagan 2018; Jenkins 2021 for Altaic; Li 2006; Huang 2018 for Chinese; Bhatt 2005 for Hindi-Urdu; López 2012 or Baker 2015 for a general overview) that another important trait is salient in the analysis of DOM: more specifically, the divide between objects that can, at least semantically, undergo complex predicate formation with the matrix predicate and objects that cannot do so.

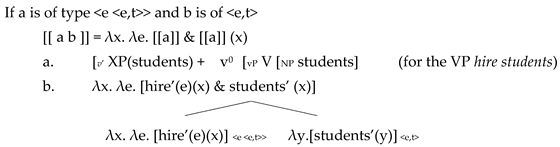

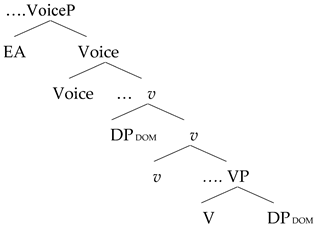

The objects that form a complex with the main predicate are predicates of type <e,t> and as a result cannot saturate the predicate with which they merge. They are rather interpreted as modifiers and are subject to the operation Restrict (Diesing 1992; Chung and Ladusaw 2004; a.o.) or Predicate Modification (Heim and Kratzer 1998), as schematically illustrated in (22). The result is semantic pseudo-incorporation.

| (22) |  |

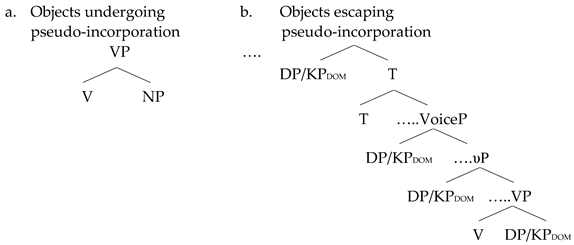

The objects undergoing pseudo-incorporation can stay bare (for example, even in languages that otherwise have overt morphology for (in)definiteness), might not carry case marking (if the language does not allow the licensing of c/Case on predicates), generally tend to be NPs, are not dependent on the discourse setting, and can be interpreted in situ (23)(a). Cross-linguistically, such objects also tend to lack differential marking (Chung and Ladusaw 2004; Levin 2015).

| (23) |  |

On the other hand, there are the direct objects with a more complex internal structure: for example, such objects might contain the D layer or structural Case features in the K layer, as in (23)(b). These categories cannot be correctly licensed and interpreted via the operation Restrict and need special licensing mechanisms. This class contains (among other elements) the differentially marked objects, the reflexes of which can be, on the surface, a higher position than the incorporating objects (as seen in the contrast in (1) from Turkic), the presence of local licensers (e.g., adpositional markers repurposed for DOM, as in Romance), obligatoriness of agreement, clitic doubling (as in non-Romance Balkan languages), or other types of special marking.

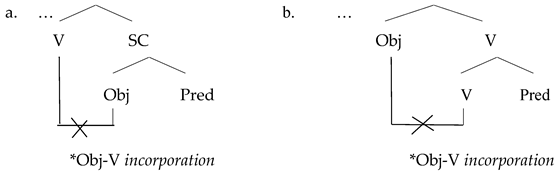

For example, in Albanian and Greek, differential object marking in the form of clitic doubling is obligatory in anti-incorporation contexts, such as clause union. This is so because of configurational restrictions—the shared argument is generated either as a subject that cannot incorporate into its predicate (as in (24)(a)) or, if it is a complement, there is no position available for it to compose with the embedded predicate because the latter must also compose with the main predicate, as seen in (24)(b)). (Semantic) incorporation into the main predicate is not possible either because the shared argument is not the complement of the main predicate.

| (24) | Clause union contexts and lack of incorporation (see López 2012; Irimia 2020a) |

|

Below, we illustrate two configurations from Albanian and Greek; in these two languages, clitic doubling appears with objects in a variety of clause union contexts (see Kallulli 2000 for extensive exemplification), among which are embedded small clauses (as in (25) and (26)). It can be easily observed that specificity or definiteness (taken as the flagging trait for clitic doubling in Greek in Anagnostopoulou’s work) can be easily overridden in such environments. Clitic doubling, thus, flags the presence of an anti-incorporation mechanism.

| (25) | Consider + SC–Albanian | |||||||

| Jan-i | nuk | e | konsideron | një | vajzë | të | tillë/Mer-in | |

| Jan-def | neg | cl.acc.3sg | consider | a | girl | such/Mary-def.acc | ||

| inteligjente. | ||||||||

| intelligent | ||||||||

| ‘John does not consider any such girl/Mary intelligent.’ | ||||||||

| (Albanian, Kallulli 2000, ex. 8a, p. 215) | ||||||||

| (26) | Consider + SC–Greek | |||||||

| O | Yannis | dhen | tin | theori | kamja | tetia | kopela | |

| def.m.sg | John | neg | cl.acc.3f.sg | consider | no | such | girl | |

| /tin | Maria | eksipini. | ||||||

| def.acc.f.sg | Maria | intelligent | ||||||

| ‘John does not consider any such girl/Mary intelligent.’ | ||||||||

| (Greek, Kallulli 2000, ex. 8b, p. 215) | ||||||||

However, even though anti-incorporation is a necessary ingredient for Romanian DOM, it is not sufficient. This is demonstrated by the examples in (27), which show that clause union contexts are possible without DOM. In fact, inanimates must be used without DOM, as in (27)(d); what is not possible in these configurations is the presence of bare nominals, that is nominals without overt definiteness or indefiniteness marking. This restriction holds for both ECM small clauses, as in (27)(c), or embedded subjunctives as in (27)(d). This indicates that,n Romanian, only bare nominals are subject to semantic incorporation. The addition of functional material related to (in)definiteness ensures anti-incorporation; one way to explain this is to assume that the D head contains a Case feature which can only be licensed by functional material at the clausal level and not via complex predicate formation.

| (27) | a. | Consideră | studenţii | foarte | inteligenţi. | |||||

| consider3 | student.m.pl.def.m.pl | very | intelligent.m.pl | |||||||

| ‘They consider the students very intelligent.’ | ||||||||||

| b. | Îi | consideră | pe | studenţi | foarte | inteligenţi. | ||||

| cl.acc.3m.pl | consider.3 | dom | student.m.pl | very | intelligent.m.pl | |||||

| ‘They consider the students very intelligent.’ | ||||||||||

| c. | *Consideră | studenţi | foarte | Inteligenţi. | ||||||

| consider.3 | student.m.pl | very | intelligent.m.pl | |||||||

| Intended: ‘They consider the students very intelligent.’ | ||||||||||

| d. | Consideră | (*pe) | produse*(le) | foarte | scumpe | şi | nu | |||

| consider.3 | dom | product.n.pl.def.n.pl | very | expensive.m.pl | and | neg | ||||

| le | vor | cumpăra. | ||||||||

| cl.acc.3n.pl | want=fut.3.pl | buy.inf | ||||||||

| ‘They consider the products very expensive and won’t buy them.’ | ||||||||||

| e. | Pune | ?studenţi/studenţii | să | îi | ||||||

| put.3sg | student.m.pl/student.m.pl.def.m.pl | sbjv | cl.acc.3m/f.sg | |||||||

| scrie | lucrările. | |||||||||

| write.3sg | paper.f.pl.def.f.pl | |||||||||

| ‘He makes the students write his papers.’15 | (Romanian) | |||||||||

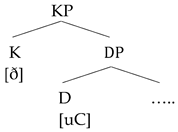

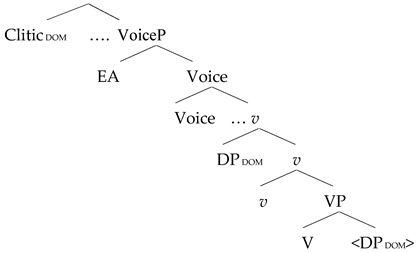

Irimia (2020a) showed that Romanian marked objects can instead be unified structurally. Crucially, the differential marker applies to nominal classes that have a complex internal structure, encompassing two types of features: (i) uninterpretable Case ([uC]), merged in D, and (ii) additional features beyond [uC], for example discourse-related ([ð]) features merged in a functional projection about the D head, for example the K head. As in Romanian the DP acts as a phase (a complete domain for interpretation), the differential marker signals the presence of any additional features beyond the phase boundary. In this line of analysis, a better understanding of the nature of differential marking breaks down to a detailed investigation of various structural realizations in the extended functional structure of nominals and the interpretive correlates they carry.

| (28) |  |

Another salient property of differentially marked objects is that they cannot easily bind into the external argument. This indicates that they are licensed in a position below VoiceP, the structural domain where external arguments are introduced. Note that this, by itself, does not imply that marked objects are not signaled by raising. They might undergo raising, but covertly, and to a position lower than vP (for example, to a position between VP and v; see López (2012), while also keeping in mind problems above with respect to DOM raising in Romanian). Binding into the external argument is made possible when the differentially marked objects are accompanied by clitic doubling. We provide two examples in (29) and (30). Only in (29)(b) and (30)(b) can the direct object be coreferential with the subject; this interpretation is absent in the examples in (29)(a) and (30)(a).

| (29) | a. | Muzica | lor*i | plictiseşte | pe | mulţi i. | |

| music.def.f.sg | their | annoy.3sg | dom | many.m.pl | |||

| ‘Their music annoys many.’ | |||||||

| b. | Muzica | lor | îii | plictiseşte pe | mulţii. | ||

| music.def.f.sg | their | cl.acc.3m.pl | annoy.3sg dom | many.m.pl | |||

| ‘Their (own) music annoys many.’ | |||||||

| (Romanian, Cornilescu 2020, ex., 24, 25, p. 164) | |||||||

| (30) | a. | Părinţii | lor*i | ajută | pe | toţi i | copiii. |

| parent.def.m.pl | their | help.3pl | dom | all.m.pl | child.m.pl.def.m.pl | ||

| ‘Their parents help all the children.’ | |||||||

| b. | Părinţii | lor | ȋii | ajută | pe | toţi i | |

| parent.def.m.pl | their | cl.acc.3m.pl | help.3pl | dom | all.m.pl | ||

| copiii. | |||||||

| child.m.pl.def.m.pl | |||||||

| ‘Their (own) parents help all the children.’ | (Romanian) | ||||||

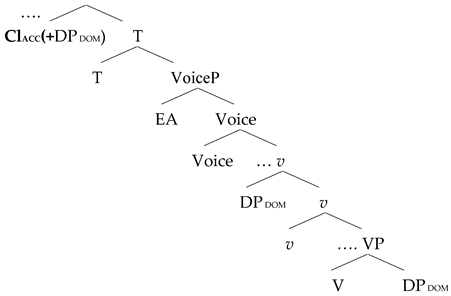

These contrasts indicate that differentially marked objects are licensed below VoiceP, the domain where the subject is introduced. Following López (2012), we assume a position between VP and VoiceP, as represented in (31). The clitic double has access to licensing above VoiceP, thus opening up the possibility of the object binding the pronominal inside the constituent containing the subject.

| (31) |  |

A similar split in binding possibilities is observed in the non-Romance Balkan languages, for example Albanian, which we illustrate here. The sentence in (32)(a) contains a direct object that is not clitic doubled; binding into the external argument is not possible. On the other hand, if the direct object is clitic doubled, it can take scope over the external argument, and thus the sentence in (32)(b) can also get an interpretation in which the pronoun contained in the subject can co-vary with the direct object. This indicates that in Balkan languages, objects that are not clitic doubled cannot raise (covertly) to a position above the external argument. In Section 5 and Section 6, we will see that Ragusa is different in this respect, as unmarked objects do not need clitic doubling in order to bind into the external argument.

| (32) | Cliticless direct objects—no binding into the external argument | |||||||

| a. | Hallet | e | tyre j | dëshpërojnë | shumë *j | njerëz. | ||

| problem.nom.def.m.pl | agr | their | despair.3pl | many | people | |||

| ‘Their problems despair many people.’ | (Albanian) | |||||||

| b. | Hallet | e | tyre j | i | dëshpërojnë | |||

| problem.nom.def.m.pl | agr | their | cl.acc.3m.pl | despair.3pl | ||||

| shumëj | njerëz. | |||||||

| many | people | |||||||

| ‘Their own problems despair many people.’ | ||||||||

| ‘Their problems despair many people.’ | (Albanian, Dalina Kallulli, p.c.) | |||||||

3.5. Romanian DOM and Clitic Doubling

The fact that the clitic double can facilitate binding into the external argument is important when it comes to its unifying traits. Similarly to what we have seen for prepositional DOM, an attempt to link clitic doubled DOM to purely semantic features does not lead to correct results. For example, postulating that clitic doubled DOM entails specificity was contradicted by the existence of non-specific contexts such as those in (33). These direct objects instead carry interpretations related to various types of genericity. Despite this, they were set aside from the partitive generics discussed in (15), when it come to interpretation; in examples similar to (15), specificity is necessary in order to ensure the presence of the differential marker. This strengthens an observation already made above: a more in-depth understanding is needed of the composition of the various internal configurations of nominal categories and, moreover, how they map to various positions in the clausal spine. What is relevant as a starting point in the analysis of examples such as those in (33) is a general internal DP architecture as in (28), and moreover, the observation that certain types of generics are not correctly licensed inside VoiceP (and thus, they need the presence of the clitic double), regardless of superficial features such as specificity. Additionally, another context with clitic doubled DOM linked to a non-specific interpretation is in (17).

| (33) | a. | De | parcă | nu | ȋi | cunosc | eu | pe | politicieni | |

| of | if | neg | cl.acc.3m.pl | know.1sg | 1sg,nom | dom | politician.m.pl | |||

| ‘As if I don’t know the politicians.’ (‘As if I do not know what the politicians are like.’) | ||||||||||

| b. | Îi | ştiu | eu | pe | hoţii | ăştia | ||||

| cl.acc.3m.pl | know.1sg | I | dom | thief.m.pl | this.m.pl | |||||

| ‘I know these crooks.’ (‘I know what crooks thieves are like.’) | ||||||||||

| c. | Ce | o | atrage | pe | o | femeie | la un | bărbat? | ||

| what | cl.acc.3f.sg | attract.1sg | dom | a.f.sg | woman | at a.m.sg | man | |||

| ‘What attracts a woman to a man?’ | (Romanian) | |||||||||

An important distinction Romanian clitic doubling exhibits as compared to the non-Romance Balkan languages is its insensitivity to information structure; in Romanian, clitic doubling on DOM applies uniformly regardless of topic or focus structures and regardless of the absence or the presence of a [+given] feature. The context in (34) is an out-of-the-blue one and the sentence in (35) contains a contrastively focused direct object; as we can see, both the prepositional differential marker and clitic doubling are present (the differential marker is obligatory for all speakers, while clitic doubling is preferred, according to what descriptive grammars indicate).

| (34) | a. | Ce | s-a | ȋntâmplat? | |||||

| what | se-have.3sg | happened | |||||||

| ‘What happened?’ | |||||||||

| b. | Un | hoţ | l-a | atacat | pe | Ion. | |||

| a.m.sg | thief | cl.acc.3m.sg-have.3sg | attacked | dom | Ion | ||||

| ‘A thief attacked Ion.’ | (Romanian) | ||||||||

| (35) | L-am | chemat | PE | ION, nu | PE | Marius. | |

| cl.acc.3m.sg-have.1 | called | dom | Ion | neg | dom | Marius | |

| ‘I have called Ion, not Marius.’ | (Romanian) | ||||||

Another difference with respect to non-Romance Balkan languages is that neither the prepositional differential marker nor clitic doubling are possible with clausal material in Romanian, regardless of factivity. The Romanian sentence in (36) is ungrammatical, with or without clitic doubling on DOM, firstly because the prepositional marker pe cannot introduce a clause.

| (36) | *L-am | crezut | pe | că | Ion | a | plecat. |

| cl.acc.3m/n.sg-have1 | believed | dom | that | Ion | have.3sg | left | |

| ‘I believed the fact that Ion left.’ | (Romanian) | ||||||

In some of the non-Romance languages in the Balkans, for example Albanian or Greek, the coreferent of the clitic can also be a full clause, and not only a DP (Tomić 1996; Kallulli 2016). As Kallulli (2016) show, the presence of the clitic double enforces factivity, even with non-factive predicates. Two examples with predicates in the believe class are illustrated below for Albanian; similar contexts have been discussed for other non-Romance Balkan languages such as Greek.

| (37) | a. | Besova | se | Beni | shkoi | (por në fact ai nuk shkoi). | |

| belive.1pst | that | Beni | left | (but in fact he not left) | |||

| ‘I believed that Beni left (but in fact he didn’t).’ | |||||||

| b. | E | besova | se | Beni | shkoi | (*por në fact ai nuk shkoi). | |

| cl.acc.3sg | believe.1pst | that | Beni | left | (but in fact he not left) | ||

| ‘I believed the fact that Ben left (*but in fact he didn’t).’ | |||||||

| (Albanian, Kallulli 2016, p. 212) | |||||||

Factive sentences can be easily assumed to contain an empty D head; when the latter has features that cannot compose with V directly (for example giveness, etc.), anti-incorporation must apply and the D head will be licensed by the clitic above vP. For constituents with a sentential nature, one of the interpretive correlates of giveness is factivity. Kallulli (2016) correctly pointed out that the presence of an empty D head in the makeup of clauses (for example, the pleonastic it in English, the es pronominal marker in German) does correlate with factivity.

However, the restrictions on differential object marking block the clitic doubling of clauses in Romanian. First, given that the clitic double is only possible with differentially marked objects, it is not sensitive just to the presence of a D head (as we saw in (28) where a more complex structure of the co-occurring nominal is needed). As clauses do not have a KP structure, the clitic double will be blocked on them. Second, sensitivity to animacy (for those contexts in which the differential marker is possible only with animates) will similarly filter out clausal projections, as the latter cannot (normally) be specified as animate. And third, full clauses do not have the same internal structure as nominal ellipsis contexts and thus cannot be differentially marked; this, in turn, will prohibit their doubling by a clitic.

As we have already said, another unifying trait of Romanian DOM contexts is that clitic doubling is not possible with objects that do not have the differential marker pronounced overtly. Thus, observe the contrast between (38)(a) and (38)(b):

| (38) | a. | Am | văzut-o | pe | fată. |

| have.1 | seen-cl.acc.3f.sg | dom | girl | ||

| ‘I saw the girl.’ | |||||

| b. | Am | văzut(-*o) | fata. | ||

| have.1 | seen-cl.acc.3f.sg | girl.def.f.sg | |||

| Intended: ‘I saw the girl.’ | (Romanian) | ||||

And lastly, clitic doubling in Romanian is not restricted to objects with a [+topic] feature; as we have seen in the examples in (34) and (35), differential marking and thus clitic doubling are possible on foci or objects that are novel in the discourse. In this respect, Romanian is clearly distinguished from non-Romance Balkan languages, in which clitic doubling has been shown to exclude material signaled as [+focus] or objects that are not given (see Kallulli (2016), who discusses this restriction for Albanian and Greek or the various contributions in Kallulli and Tasmowski (2008a), who mention the same facts for other non-Romance Balkan languages).16

3.6. Clitic Doubling vs. Clitic Resumption

The restriction of clitic doubling to differentially marked objects in Romanian is relevant from yet another respect: it sets aside clitic doubling from clitic resumption. As we mentioned in Section 2.2, the latter flags overtly dislocated nominals, with a heavy prosodic break. Crucially, Romanian clitic resumption is not dependent on animacy and can/must apply regardless of whether the dislocated object is differentially marked or not. In (39)(a), the resumptive clitic is obligatory, irrespective of animacy; what counts instead is the fact that the dislocated object is a definite direct object. In (39)(b), the same inanimate direct object, but this time in situ, is ungrammatical with clitic doubling. Non-dislocated objects are not possible in situ without differential marking, which in the case of nominals with lexical material would require the presence of animacy. As the nominal is inanimate, the addition of the differential marker (to ensure the presence of clitic doubling) results in ungrammaticality. Other important contexts illustrating the differences between clitic doubling and clitic resumption are addressed in Section 4.1.

| (39) | a. | Cartea | nouă, | nu | am | citit-*(o). | ||||

| book.def.f.sg | new.f.sg | neg | have | read-cl.acc.3f.sg | ||||||

| ‘The new book, I haven’t read it.’ | ||||||||||

| b. | Nu | am | citit(*-o) | cartea | nouă. | |||||

| neg | have | read-cl.acc.3f.sg | book.def.f.sg | new.f.sg | ||||||

| Intended: ‘I haven’t read the new book.’ | ||||||||||

| c. | Nu | am | citit(*-o) | (*pe) | cartea | nouă. | ||||

| neg | have | read-cl.acc.3f.sg | dom | book.def.f.sg | new.f.sg | |||||

| Intended: ‘I haven’t read the new book.’ | (Romanian) | |||||||||

3.7. South Danubian Romance

Before concluding this section, it is necessary to say a few words about the South Danubian Balkan area which contains other Romance languages, namely Megleno-Romanian and Aromanian (Capidan 1932; Papatsafa 1997; Friedman 2008; Manzini and Savoia 2018; Hill and Mardale 2021; a.o.), with their varieties. Some of these varieties show differential object marking, traditionally identified as clitic doubling; depending on the more precise variety, the patterns resemble either Macedonian or Greek. In the two Aromanian examples in (40) and in the sentence (41) from Megleno-Romanian, the direct object shows clitic doubling in the absence of a prepositional marker. This type of realization is not possible in Romanian, as seen in the corresponding structures in (42).

| (40) | a. | Auš-lu nu | vrea | s-l’ | u-aspargă | k’efe-(a) | |

| old-def neg wanted.3sg | sbjv-cl.dat.3sg | cl.acc.3sg-spoil | pleasure-def | ||||

| a | fičor-lui. | ||||||

| at | boy-dat.def.m.sg | ||||||

| ‘The old man didn’t want to spoil the child’s pleasure.’ | |||||||

| (Aromanian Kruševo, Friedman 2008, e.g., 42a, p. 55) | |||||||

| b. | U | vădzuj | kas-a | al | aist | om. | |

| cl.acc.3sg | saw.1sg | house-def.f.sg | gen/dat-def.m.sg | this.m.sg | man | ||

| ‘I saw this man’s house.’ | |||||||

| (Aromanian Ohrid, Friedman 2008, e.g., 43a, p. 55) | |||||||

| (41) | Lă | loa | bucium-ul, lă | turi | shi | zisi. | |

| cl.acc.3sg | take.3sg | log-def.sg | cl.acc.3sg | threw.3sg | and | said.3sg | |

| ‘He took the log, threw it (away) and said.’ | |||||||

| (Megleno-Romanian, Papatsafa 1997, p. 15) | |||||||

| (42) | a. | Am | văzut(*-o) | casa | acestui | om. |

| have.1sg | seen-cl.acc.f.3sg | house.def.f.sg | this.m.sg.gen.m.sg | man | ||

| Intended: ‘I saw this man’s house.’ | ||||||

| b. | (*L-)a | luat | buşteanul. | |||

| cl.acc.m.3sg-have.3sg | taken | log-def.sg | ||||

| Intended: ‘He took the log.’ | (Romanian) | |||||

Makarova and Winistörfer (2020), in turn, discuss patterns of prepositional differential object marking characterizing South Danubian Romance in the districts of Struga, Resen, and Bitola (villages of Dolna Belica, Gorna Belica, Malovishte) in Macedonia. While the marking is morphologically similar to Romanian in that the pe preposition is used, differences arise with respect to at least two traits, as illustrated by Makarova and Winistörfer (2020) examples in (43): (i) the clitic doubling strategy is also possible on unmarked objects and (ii) prepositional DOM is possible on in situ lexical inanimates.

| (43) | a. | u | mutresc | pi | fata. |

| cl.acc.3sg | see.pres.1sg | dom | girl.def.f.sg | ||

| I see the girl (one of many).’ | |||||

| (Aromanian, Gorna Belica, RaSt, Makarova and Winistörfer 2020, p. 1) | |||||

| b. | u | mutresc | fata. | ||

| cl.acc.3sg | see.pres.1sg | girl.def.f.sg | |||

| ‘I see this girl.’ | |||||

| (Aromanian, Gorna Belica, RaSt, Makarova and Winistörfer 2020, p. 1) | |||||

| c. | u | ved | pi | lemnu. | |

| cl.acc.3sg | see.pres.1sg | dom | tree.def.m.sg | ||

| ‘I see the tree.’ | |||||

| (Aromanian, Dolna Belica, WiCa, Makarova and Winistörfer 2020, p. 2) | |||||

| d. | *Îl | văd | pe | copacul. | |

| cl.acc.m.3sg | see.1sg | dom | tree.def.m.sg | ||

| Intended: ‘I see the tree.’ | (Romanian) | ||||

| e. | Văd | copacul. | |||

| see.1sg | tree.def.m.sg | ||||

| ‘I see the tree.’ | (Romanian) | ||||

Table 2 summarizes the results of this section with respect to the most important correlates of Romanian DOM. Additionally, a summary of salient traits of clitic doubling in the non-Romance Balkan domain discussed in the literature (according to the references cited above and also Assenova 1980; Dimitrova-Vulchanova and Hellan 1999a, 1999b; Leafgren 1997; Schick 2000; Schick and Beukema 2001; Jaeger and Gerassimova 2002; Tisheva and Dzonova 2002; Guentchéva 2008; Krapova and Cinque 2008; Kochovska 2011; Harizanov 2014; among many others), also underlines their differences from Romanian DOM.

Table 2.

DOM strategies: Cl-doubling (Greek, Albanian, Macedonian) vs. prep-DOM (Romanian).

4. Differential Object Marking Ragusa: A Comparison with Romanian

In all the Romance dialects of (Southern) Italy that display instances of DOM, the element that introduces differentially marked objects is a, homophonous with the dative/locative preposition a (Ledgeway 2016, p. 268). Aside from this, the Romance dialects of Italy display a wide array of internal variation concerning the properties of differentially marked objects (Ledgeway 2023). Therefore, no individual dialect can be taken as exhaustively encompassing the whole internal diversity observed in this region: we take the dialect of Ragusa as a starting point. In the future, extending the empirical domain to additional dialects is likely to add further evidence relevant for comparison.

Similarly to Romanian, Ragusa presents a DOM system built on conjunctive features. The two major traits necessary for differential marking are the overt realization of the D area (for example the D head) and the [+human] feature of the object (Guardiano 2023).

As shown in (44), objects introduced by an article ((44)(a) and (44)(b)) or by an item that has raised to the D area (such as a demonstrative in (44)(c), a numeral in (44)(d), a proper name, or a kinship noun with a possessor in (44)(e)) are obligatorily a-marked if the referent is [+human] (Guardiano 1999, 2000; 2023, pp. 196–201).

| (44) | a. | Vitti | *(a) | nu | / | o | piccjuòttu. | ||

| see.1sg.pst | dom | a.m.sg | dom+def.m.sg | young.person.m.sg | |||||

| ‘I saw a/the boy.’ | |||||||||

| b. | Vitti | e | / | *i | surdati. | ||||

| see.1sg.pst | dom+def.pl | def.pl | soldier.pl | ||||||

| ‘I saw the soldiers.’ | |||||||||

| c. | Ciamàu | *(a) | ḍḍu/ssu/ṣṭu | picciuòttu. | |||||

| call.3sg.pst | dom | dem.m.sg | young.person.m.sg | ||||||

| ‘(S)he called that/this guy.’ | |||||||||

| d. | Vitti | *(a) | ṭṭṛi | surdati. | |||||

| see.1sg.pst | dom | three | soldier.pl | ||||||

| ‘I saw three soldiers.’ | |||||||||

| e. | U | prufissuri | ciamàu | *(a) | Ggiovanni | / mmo frati | |||

| def.m.sg | professor | call.3sg.pst | dom | Giovanni | / my brother | ||||

| ‘The teacher called Giovanni/my brother.’ | (Ragusa) | ||||||||

All types of pronominals (e.g., personal pronouns, demonstratives, indefinite, and negative quantifiers used pronominally) with [+human] referents are systematically a-marked, as shown in the examples in (45). This is the exact picture as in Romanian.

| (45) | a. | U | prufissuri | ciamàu | *(a) | mmìa/ tìa / niàuṭṛi / viàuṭṛi / |

| def.m.sg | professor | call.3sg.pst | dom | 1sg / 2sg / 1pl / 2pl / | ||

| iḍu / iḍa / iḍi. | ||||||

| 3sg.m / 3sg.f / 3pl | ||||||

| ‘The teacher called me/you/us/you/him/her/them.’ | ||||||

| b. | U | prufissuri | ciamàu | *(a) | cchiḍu/cchissu/cchistu. | |

| def.m.sg | professor | call.3sg.pst | dom | dem.m.sg | ||

| ‘The teacher called this/that (guy).’ | ||||||

| c. | Vuògghiu | *(a) | quaccarunu. | |||

| want.1sg.pst | dom | somebody | ||||

| ‘I want somebody.’ | ||||||

| d. | Nun | vuògghiu | *(a) | nnuḍu. | ||

| neg | want.1sg.pst | dom | nobody | |||

| I don’t want anybody.’ | (Ragusa) | |||||

The ‘overt D’ condition is a necessary one: objects where the D area is left empty, i.e., where no D item is overtly realized, are never a-marked, as demonstrated by (46), which has a bare nominal. We have seen that Romanian bare nominals, as in (19)(a), are similarly excluded from differential marking; the same restriction appears to hold for clitic doubling Balkan languages, even if various exceptions have been pointed out in the literature (see, among others, Kallulli and Tasmowski 2008b).

| (46) | Vitti | (*a) | surdati | ka | pssàunu. |

| see.1sg.pst | dom | soldier.pl | that | pass-by.3pl.pst | |

| ‘I saw soldiers who passed by.’ | (Ragusa) | ||||

One important difference from Romanian is that [-animate] objects are never a-marked; this can be seen in the examples in (47), where pronominal items ((47)(a–c)) and full nominal phrases (47)(d) tracking a [-animate] referent are incompatible with a-marking. We showed that in Romanian, the [-animate] feature can be overridden in some contexts, especially under nominal ellipsis, for example in sentences such as (11).

| (47) | a. | U | prufissuri | pigghiàu | (*a) | chistu. | |||

| def.m.sg | professor | take.3sg.pst | dom | this | |||||

| ‘The teacher picked up this one (thing).’ | |||||||||

| b. | Vuògghiu | (*a) | quarchiccosa | ||||||

| want.1sg.pst | dom | something | |||||||

| ‘I want something.’ | |||||||||

| c. | Nun | vuògghiu | (*a) | nenti. | |||||

| neg | want.1sg.pst | dom | nothing | ||||||

| ‘I don’t want anything.’ | |||||||||

| d. | Vitti | (*a) | n | / | *o | / | u | tàvulu. | |

| see.1sg.pst | dom | a.m.sg | dom+def.m.sg | def.m.sg | table.m.sg | ||||

| ‘I saw a/the table.’ | |||||||||

| e. | Vitti | i | / | *e | casi. | ||||

| see.1sg.pst | def.pl | dom+def.pl | house.pl | ||||||

| ‘I saw the houses.’ | (Ragusa) | ||||||||

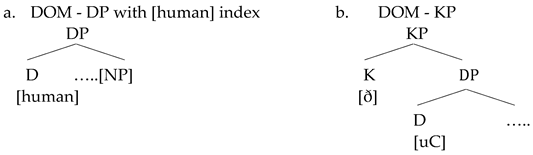

An important difference between the two languages is thus related to the nature of nominal ellipsis and its structure. Nominal ellipsis does not appear to involve functional material above D in Ragusa. This, in turn, has consequences on a distinction in the internal structure of differentially marked objects in Romance: as López (2012) also notices in some languages, differentially marked objects contain the D head with an animacy index ((48)(a)), while others require a lager structure, for example a KP, as in (48)(b). Ragusa falls into the former class, while Romanian is a clear illustration of the latter setting. In the Romanian type, as functional material beyond the DP is needed, and the K head may override animacy; what is relevant for nominal ellipsis in Romanian is a certain kind of anaphoricity, which is constructed from definiteness (and thus requires the D head besides the additional anaphoricity feature in K), and which goes beyond animacy.

| (48) |  |

Some types of [-human] objects are occasionally a-marked in Ragusa if their referent is [+animate], as seen in (49). In this respect, animacy seems to play a role in discriminating between objects that can be a-marked [-human, +animate] and objects that are never a-marked [-animate].

| (49) | Vitti | ?e | / | i | cani. |

| see.1sg.pst | dom+def.pl | def.pl | dog.pl | ||

| ‘I saw the dogs’ | |||||

In Ragusa, differences in terms of definite vs. non-definite readings of the object do not have consequences on a-marking. As far as the role of specificity is concerned, ‘the evidence collected so far in Ragusa has not provided any decisive data’ (Guardiano 2023, p. 215). There are dialects of Sicily (for example Mussomeli, Cruschina p.c.) where a, with certain types of objects (e.g., negative quantifiers or pronominal objects), seems to be required with a specific reading: no such evidence has been found in Ragusa, so far. Though, it is not to be excluded that the specific vs. non-specific reading occasionally plays a role in the cases of ‘optional’ DOM, i.e., with objects that show overt D and are [+animate]. In most positions, [+animate] objects freely alternate between the presence and absence of a-marking, as shown in (50)(a), (b), and (c). One exception to free alternation is represented by objects in (contrastive) topic position, that do not accept a-marking, as shown in (50)(d). According to the speakers, the latter is strongly dispreferred (although not impossible).

| (50) | a. | Pòttimi | (a) | ssu | cani. | ||

| bring.1sg.dat.cl | dom | dem.m.sg | dog | ||||

| ‘Bring me that dog!’ | |||||||

| b. | Pottammillu | (a) | ssu | cani. | |||

| bring.1sg.dat.cl.3sg.m.acc.cl | dom | dem.m.sg | dog | ||||

| ‘Bring me that dog!’ | |||||||

| c. | (A) | ssu | cani | pottammillu. | |||

| dom | dem.m.sg | dog | bring.1sg.dat.cl.3sg.m.acc.cl | ||||

| ‘Bring me that dog!’ | |||||||

| d. | Ssu | cani, | pòttimi | (no | l’auṭṛu). | ||

| dem.m.sg | dog | bring.1sg.dat.cl | neg | def-other | |||

| ‘Bring me that dog!’ (with strongly marked intonation on ssu cani) | |||||||

In Ragusa, categories that normally need differential object marking when found in situ can marginally drop the differential marker if dislocated to the left periphery as a result of topicalization (also under focus), as shown by the contrasts between (51)(a) and (b) and (52)(a) and (b). This is another difference from Romanian, which we address in more detail in the next subsection.

| (51) | a. | Nun | vìttimu | *(a) | nnuḍu. |

| neg | see.1pl.pst | dom | nobody | ||

| ‘We didn’t see anybody.’ | |||||

| b. | (A) | nnuḍu | vìttimu. | ||

| dom | nobody | see.1pl.pst | |||

| ‘We didn’t see anybody.’ (with marked intonation on nnuḍu) | (Ragusa) | ||||

| (52) | a. | Am | a | ccircari | *(a) | quarcarunu. | |

| have.1pl | to | look.for | dom | someone | |||

| ‘We need to look for someone.’ | |||||||

| b. | A | quarcarunu | am | a | ccircari | ||

| dom | someone | have.1pl | to | look.for | |||

| ‘Someone, we need to look for him.’ | |||||||

| c. | Quarcarunu, | am | a | ccircari | |||

| someone | have.1pl | to | look.for | ||||

| ‘As for someone, we need to look for him.’ | |||||||

| (with strongly marked intonation on quarcarunu) | (Ragusa) | ||||||

4.1. Dropping the Differential Marker under Dislocation: Back to Romanian

In Romanian, overt displacement to the left periphery in order to signal a familiarity topic or a direct object under contrastive focus does not yield grammaticality if the category normally requires differential marking in situ; if anything, overt displacement to the left periphery enriches differential marking possibilities and does not reduce them. This is seen in (53).

| (53) | a. | Căutăm | *(pe) | cineva. | ||

| look for.1pl | dom | somebody | ||||

| ‘We are looking for somebody.’ | ||||||

| b. | *(Pe) | cineva/*(PE) | CINEVA, | căutăm. | ||

| dom | somebody/dom | somebody | look for.1pl | |||

| Literally: ‘Somebody, we are looking for.’ | (Romanian) | |||||

There is one exception, related to the realization of aboutness topics, which cannot have the differential marker, or for that matter any type of overt case marking. This restriction imposed by aboutness topics is not a quirk of Romanian; it is exhibited by many other languages with overt object marking (see, for example, the discussion about Bulgarian in Krapova and Cinque (2008)). The two sentences in (54) illustrate an honorific animate DP accompanied by a demonstrative (another similar example is in (9)(d)). This type of nominal cannot be used without differential marking as an in situ direct object; the same restriction holds for indirect objects, where dative case morphology is similarly needed.

| (54) | a. | O | voi | invita la | nuntă | *(pe) | doamna | |

| cl.acc.3f.sg fut.1sg | invite.inf at | wedding | dom | lady.def.f.sg | ||||

| aceea | binevoitoare. | |||||||

| that.f.sg.aug | kind.f.sg | |||||||

| ‘I will invite that kind lady to the wedding.’ | ||||||||

| b. | Îi | voi | da | un | cadou | doamnei | ||

| cl.dat.3sg | fut.1sg | give.inf | a.n.sg | gift | lady.dat.f.sg | |||

| aceleia | binevoitoare/*doamna | aceea | binevoitoare | |||||

| that.dat.f.sg.aug | kind.f.sg/lady.def.f.sg | that.f.sg.aug | kind.f.sg | |||||

| ‘I will give a gift to the kind lady.’ | (Romanian) | |||||||

This DP can be dislocated to the right periphery, either as a direct object or an indirect object. Dislocation can be implemented under two morphological realizations. On the one hand, there are various types of foci, and also the familiarity topic, which must preserve the differential marker on the direct object and the dative case on the indirect object.

| (55) | a. | *(Pe) | doamna | aceea | binevoitoare | o | voi | |||

| dom | lady.def.f.sg | that.f.sg.aug | kind.f.sg | cl.acc.3f.sg | fut.1sg | |||||

| invita | la | nuntă. | ||||||||

| invite.inf at | wedding | |||||||||

| ‘That kind lady, I will invite to the wedding.’ | ||||||||||

| b. | Doamnei | aceleia | binevoitoare/*doamna | aceea | ||||||

| lady.dat.f.sg | that.dat.f.sg.aug | kind.f.sg/ lady.def.f.sg | that.f.sg.aug | |||||||

| binevoitoare, îi | voi | da | un | cadou | ||||||

| kind.f.sg | cl.dat.3sg | fut.1sg | give.inf | a.n.sg gift | ||||||

| ‘To that kind lady, I will give a gift.’ | (Romanian) | |||||||||

On the other hand, there is the aboutness topic, a category that does not allow dislocated nominals with overt case marking. The DP must use its unmarked form instead. Examine the difference between the overt morphology of the direct and indirect objects in (55) and the lack of overt morphology on the aboutness topics in (56). The underlying grammatical relation of the unmarked nominal is still revealed by the resumptive clitic; the latter has accusative morphology in (56)(a), while it has dative morphology in (56)(b). Note that the unmarked aboutness topic in (56)(b) is characteristic of informal speech.

| (56) | a. | Doamna | aceea | binevoitoare, | sigur | o | voi | |||

| lady.def.f.sg | that.f.sg.aug | kind.f.sg | certain | cl.acc.3f.sg | fut.1sg | |||||

| Invita | la | nuntă. | ||||||||

| invite.inf | at | wedding | ||||||||

| ‘About that kind lady, I will definitely invite her to the wedding.’ | ||||||||||

| b. | Doamna | aceea | binevoitoare, | sigur | o | să | ||||

| lady.def.f.sg | that.f.sg.aug | kind.f.sg | certain | fut | sbjv | |||||

| îi | dau | un | cadou. | |||||||

| cl.dat.3sg | give.1sg | a.n.sg gift | ||||||||

| ‘About/regarding that kind lady, I will definitely give her a gift.’ | ||||||||||

| (Romanian) | ||||||||||

Despite the availability of aboutness topics in Romanian, not all DPs can fulfill this function. For example, the animate quantifier illustrated in (53) cannot do so and thus cannot be used without the differential marker when realized as a dislocated direct object. This signals another difference between Ragusa and Romanian, first of all related to the nature of hanging topics, and subsequently to differential marking. In general, what the discussion above indicated is that the distinctions in the structural setup and interpretive possibilities in the two languages go beyond the contexts that are traditionally addressed in the literature.

5. Clitic Resumption and Clitic Doubling in Ragusa

As the examples discussed so far show, in Ragusa, a-marked objects do not require clitic doubling. This restriction encompasses not only lexical DPs, but also tonic pronouns used as direct objects. By contrast, animate DPs realized as direct objects normally need clitic doubling in Romanian. The latter is, moreover, obligatory with tonic pronouns (which must also be differentially marked).

| (57) | a. | Profesorul | *(m)-a | chemat | *(pe) mine. | ||

| professor.def.m.sg | cl.acc.1sg-have.3sg | called | dom | 1sg.acc | |||

| ‘The professor called me.’ | |||||||

| b. | Profesorul | *(l)-a | chemat | *(pe) el. | |||

| professor.def.m.sg cl.acc.3m.sg-have.3sg | called | dom | 3sg.m | ||||

| ‘The professor called him.’ | (Romanian) | ||||||

The presence of accusative clitic doubling on objects that are already marked, besides delimitating a typological class (see especially Cornilescu 2006; Cornilescu and Dobrovie-Sorin 2008; Tigău 2011; Hill and Mardale 2021 for Romanian), has various interpretive and structural correlates. For example, as we have seen, clitic doubling opens the possibility for the marked object to take scope over the external argument in Romanian (Cornilescu 2020; a.o.).

In Ragusa, there are a-marked objects that can (or must) exhibit a reduplicating clitic pronoun, as can be seen in (58)(a) and (58)(b).

| (58) | a. | E | picciuòtti | i | vìttimu | (a | ttutti) | |

| dom+def.pl | young.person.pl | cl.acc.pl | see.1pl.pst | dom | all.pl | |||

| ‘As for the boys, we saw them (all).’ | ||||||||

| b. | I | vìttimu | (a | ttutti) | e | picciuòtti. | ||

| cl.acc.3pl see.1pl.pst | dom | all.pl | dom+def.pl | young.person.pl | ||||

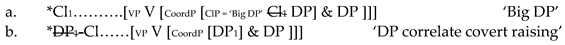

| ‘As for the boys, we saw them (all).’ | (Ragusa) | |||||||