Abstract

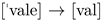

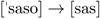

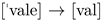

In Brazilian Veneto (a heritage variety of Veneto spoken in several areas of Brazil), a stem alternation targets the plurals of masculine nominals ending in a consonant. While nominals with a word-final rhotic or nasal are pluralized by adding the masculine plural suffix ‘glass’), pluralization in nominals with a final lateral involves deletion of the consonant (e.g., ‘bedsheet’). I argue that these differences stem from word-final laterals having a distinct representation from rhotics and nasals: while the latter are represented as codas, the former are represented as onsets of empty-headed syllables. Based on a corpus analysis, I show that (a) speakers’ productions of these plurals are stable, and (b) other patterns of pluralization (namely, in monosyllables and words with final stress on a CV syllable) are consistent with the proposal. In addition, the behaviour of laterals with respect to resyllabification, metaphony and intervocalic consonant deletion further suggest that laterals are represented as onsets word-finally.

1. Introduction

The representation of word-final consonants has been a topic of investigation in many phonological frameworks. One reason for phonologists’ interest in such consonants is that they often behave differently from word-internal (coda) consonants, in that they may or may not be assigned weight, or in that they may or may not be involved in phonological processes. To account for the dissimilar behaviour between word-internal and word-final consonants, analyses have proposed specific mechanisms to differentiate between the two, such as extrametricality (where the extrametrical consonant is not parsed into foot structure and therefore does not contribute to weight; e.g., Hayes (1995); Ito (1988)), and the sharing of syllabic or weight positions (which may result in the consonant being assigned weight; e.g., Kiparsky (2003); Watson (1997)), as well as distinct syllabic representations. Regarding the latter, it has been proposed that word-internal and word-final consonants are represented differently (e.g., Harris (1997); Kaye (1990)). For example, in Standard Government Phonology (Kaye 1990), word-internal codas are analyzed as such, while word-final codas are regarded as onsets of empty-headed syllables. Alternatively, it has also been argued that word-final consonants may be targeted by specific types of licensing, which allows them to be parsed as either codas or onsets (Piggott 1999).

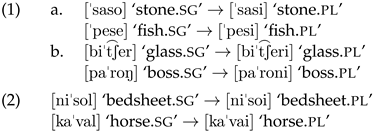

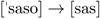

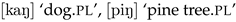

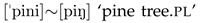

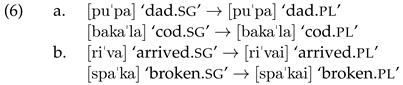

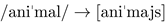

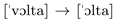

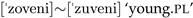

In this paper, I examine the alternation observed in the pluralization of masculine nominals in Brazilian Veneto (henceforth BV), to argue that it is motivated by distinct representations of word-final consonants. Like in other Italo-Romance languages (such as Standard Italian), the pluralization of masculine nominals in Veneto varieties (those in Italy and elsewhere) involves suffix /-i/ (Belloni 2009; Luzzatto 2000; Stawinski 1982; Zamboni 1974). However, in BV (and a subset of other Veneto varieties), the pluralization of these nominals results in an alternation that targets the stem. On the one hand, ‘regular’ pluralization involves either the replacement of a theme vowel (/-o/ or /-e/) by the plural suffix (1-a) or the addition of the plural suffix to nominals ending in a rhotic or nasal consonant (1-b). On the other hand, in nominals ending in a lateral, pluralization yields a VV string, with no lateral on the surface (2)—the VV string may be realized as a diphthong or hiatus (Guzzo 2023).

In what follows, I propose that this alternation can be explained if we assume that word-final rhotics and nasals are represented as codas, while word-final laterals are represented as onsets (of empty-headed syllables). I use corpus data (from the Talian Corpus; Garcia and Guzzo (2023)) to argue that word-final laterals behave differently from other word-final consonants in terms of plural assignment. In addition, I show that (a) the pluralization of other BV nominals (namely, monosyllables and words with final stress on a CV syllable) and (b) the behaviour of laterals with respect to other BV phonological phenomena are consistent with the proposal that word-final laterals are represented differently.

As will be detailed below, the Talian Corpus is a corpus of written texts in BV obtained from newspaper articles and book excerpts. As BV does not have a standardized orthography, the authors of these materials often mark their pronunciations in writing and follow their intuitions about the well-formedness of grammatical constructions. Since BV has developed (and still is) in a contact situation favouring linguistic variation, surface variation that is revealing of phonological structure could be potentially manifested in the writers’ realization of plurals. In this case, examining written corpus data is a useful tool for capturing the patterns that reflect speakers’ representations.

This paper is organized as follows. In the next section, I discuss the properties of BV stress and syllable structure, with a focus on the behaviour of consonants that can appear word-finally. In Section 3, I present the representations for word-final consonants in BV and discuss them based on corpus data. In this section, as well as in subsequent sections that include corpus data, the relevant patterns in the data are quantified and the distributions of such patterns in the writers’ productions are provided. I examine corpus data from the pluralization of other BV structures in Section 4, as well as data from additional phonological phenomena in Section 5, to show that they are all compatible with the proposal. Section 6 discusses the BV representations in view of other approaches in phonological theory, and Section 7 concludes.

2. BV Stress and ‘Coda’ Profile

Brazilian Veneto is a heritage variety of Veneto (Italo-Romance) spoken in several areas of Brazil. BV is usually referred to by its speakers as Talian (the word for Italian in BV, even though BV is not a dialect of Standard Italian). BV was developed in Brazil after the massive wave of Italian immigration that started in the mid-to-late 19th century (De Boni and Costa 1979). A large proportion of these immigrants settled in southern Brazil and spoke a variety of Veneto. Particularly in southern Brazil, the Italian immigrant communities were relatively isolated from Portuguese-speaking communities and communities where the majority language was another immigrant language, which favoured the development of a Veneto-based koine (Frosi and Mioranza 1983, 2009).

Many characteristics of the BV phonology and morphosyntax can be associated with Central Veneto, the variety spoken in the Veneto region where Padova and Verona are situated (Frasson 2021; Guzzo 2023). However, BV also exhibits features of other Veneto dialects, properties from other languages brought by Italian immigrants and properties resulting from contact with Portuguese (Frosi and Mioranza 1983). As expected in situations of language contact, many processes observed in BV are variable, as is the use of certain lexical items (including borrowings from Portuguese). Still, although BV can be considered some sort of lingua franca in most Italian immigrant communities in southern Brazil (see e.g., Pertile (2009)), some immigration areas correspond to linguistic islands where mostly one Italian immigration language or Veneto variety is spoken (see e.g., Bonatti (1974)).

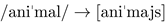

Like other Romance languages and Veneto dialects, BV has a trisyllabic window for stress assignment. Stress is mostly penultimate, unless the final syllable is CVC, in which case stress is final (Guzzo 2023). This pattern is almost exceptionless, as the few items that deviate from it (and thus display penultimate stress when there is a final CVC syllable) seem to be loanwords that entered through Portuguese (e.g.,  ‘revolver’,

‘revolver’,  ‘virus’) and verbs ending in -er (e.g., compare

‘virus’) and verbs ending in -er (e.g., compare  ‘to see’,

‘to see’,  ‘to drink’ with

‘to drink’ with  ‘to work’,

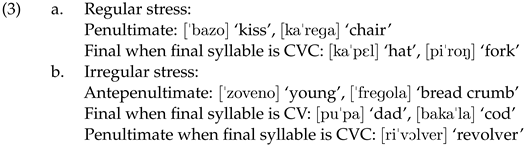

‘to work’,  ‘to depart’; Dal Castel et al. (2021)). Antepenultimate stress and final stress on a final CV syllable are also possible, albeit infrequent. The examples in (3) summarize the stress patterns found in BV.

‘to depart’; Dal Castel et al. (2021)). Antepenultimate stress and final stress on a final CV syllable are also possible, albeit infrequent. The examples in (3) summarize the stress patterns found in BV.

‘revolver’,

‘revolver’,  ‘virus’) and verbs ending in -er (e.g., compare

‘virus’) and verbs ending in -er (e.g., compare  ‘to see’,

‘to see’,  ‘to drink’ with

‘to drink’ with  ‘to work’,

‘to work’,  ‘to depart’; Dal Castel et al. (2021)). Antepenultimate stress and final stress on a final CV syllable are also possible, albeit infrequent. The examples in (3) summarize the stress patterns found in BV.

‘to depart’; Dal Castel et al. (2021)). Antepenultimate stress and final stress on a final CV syllable are also possible, albeit infrequent. The examples in (3) summarize the stress patterns found in BV.

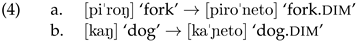

The consonants that can be found in word-final position in BV are  . In the remainder of this section, for the sake of clarity, I will refer to BV word-final (and syllable-final) consonants as codas, even though the analysis that follows will revise this assumption. In derived words where the final nasal is followed by a suffix vowel,

. In the remainder of this section, for the sake of clarity, I will refer to BV word-final (and syllable-final) consonants as codas, even though the analysis that follows will revise this assumption. In derived words where the final nasal is followed by a suffix vowel,  does not surface. What surfaces instead is either

does not surface. What surfaces instead is either  or

or  . This is illustrated in the examples in (4), where the masculine diminutive suffix

. This is illustrated in the examples in (4), where the masculine diminutive suffix  attaches to a stem ending in a nasal. This observation suggests that the word-final velar nasal is not phonemic in the BV system, but rather the result of a neutralization process (Guzzo 2023).

attaches to a stem ending in a nasal. This observation suggests that the word-final velar nasal is not phonemic in the BV system, but rather the result of a neutralization process (Guzzo 2023).

. In the remainder of this section, for the sake of clarity, I will refer to BV word-final (and syllable-final) consonants as codas, even though the analysis that follows will revise this assumption. In derived words where the final nasal is followed by a suffix vowel,

. In the remainder of this section, for the sake of clarity, I will refer to BV word-final (and syllable-final) consonants as codas, even though the analysis that follows will revise this assumption. In derived words where the final nasal is followed by a suffix vowel,  does not surface. What surfaces instead is either

does not surface. What surfaces instead is either  or

or  . This is illustrated in the examples in (4), where the masculine diminutive suffix

. This is illustrated in the examples in (4), where the masculine diminutive suffix  attaches to a stem ending in a nasal. This observation suggests that the word-final velar nasal is not phonemic in the BV system, but rather the result of a neutralization process (Guzzo 2023).

attaches to a stem ending in a nasal. This observation suggests that the word-final velar nasal is not phonemic in the BV system, but rather the result of a neutralization process (Guzzo 2023).

In word-medial coda position,  surfaces as the result of place assimilation with the following consonant. The same is attested with other nasal qualities (e.g.,

surfaces as the result of place assimilation with the following consonant. The same is attested with other nasal qualities (e.g.,  ‘less’,

‘less’,  ‘field’,

‘field’,  ‘large’). The velar nasal is not observed in onset position in BV.

‘large’). The velar nasal is not observed in onset position in BV.

surfaces as the result of place assimilation with the following consonant. The same is attested with other nasal qualities (e.g.,

surfaces as the result of place assimilation with the following consonant. The same is attested with other nasal qualities (e.g.,  ‘less’,

‘less’,  ‘field’,

‘field’,  ‘large’). The velar nasal is not observed in onset position in BV.

‘large’). The velar nasal is not observed in onset position in BV.Like other Veneto dialects, BV has only one rhotic phoneme, which is usually produced as a trill ( ) or a tap (

) or a tap ( ), although additional realizations (approximant, fricative and mixed) have also been reported. Following from the observation that rhotic quality can be correlated with duration (at least in what comes to the distinction between trills and taps; Ladefoged and Maddieson (1996)), Guzzo (2024) has found that rhotics in singleton onsets of stressed syllables (e.g.,

), although additional realizations (approximant, fricative and mixed) have also been reported. Following from the observation that rhotic quality can be correlated with duration (at least in what comes to the distinction between trills and taps; Ladefoged and Maddieson (1996)), Guzzo (2024) has found that rhotics in singleton onsets of stressed syllables (e.g.,  ‘red’) are the longest, which is consistent with trill productions, while rhotics in branching onsets (e.g.,

‘red’) are the longest, which is consistent with trill productions, while rhotics in branching onsets (e.g.,  ‘pants’) are the shortest, which is consistent with tap productions. Coda rhotics (e.g.,

‘pants’) are the shortest, which is consistent with tap productions. Coda rhotics (e.g.,  ‘spoon’,

‘spoon’,  ‘pig’), on the other hand, have an intermediate duration. This intermediate duration seems to stem from the observation that, even though all types of rhotics can appear in all prosodic positions, there is overall more variation in the types of rhotics produced in the coda. In other words, the distribution of rhotic types is more balanced in coda position than in branching onsets (where they are mostly taps or approximants) or singleton onsets of stressed syllables (where they are mostly trills).

‘pig’), on the other hand, have an intermediate duration. This intermediate duration seems to stem from the observation that, even though all types of rhotics can appear in all prosodic positions, there is overall more variation in the types of rhotics produced in the coda. In other words, the distribution of rhotic types is more balanced in coda position than in branching onsets (where they are mostly taps or approximants) or singleton onsets of stressed syllables (where they are mostly trills).

) or a tap (

) or a tap ( ), although additional realizations (approximant, fricative and mixed) have also been reported. Following from the observation that rhotic quality can be correlated with duration (at least in what comes to the distinction between trills and taps; Ladefoged and Maddieson (1996)), Guzzo (2024) has found that rhotics in singleton onsets of stressed syllables (e.g.,

), although additional realizations (approximant, fricative and mixed) have also been reported. Following from the observation that rhotic quality can be correlated with duration (at least in what comes to the distinction between trills and taps; Ladefoged and Maddieson (1996)), Guzzo (2024) has found that rhotics in singleton onsets of stressed syllables (e.g.,  ‘red’) are the longest, which is consistent with trill productions, while rhotics in branching onsets (e.g.,

‘red’) are the longest, which is consistent with trill productions, while rhotics in branching onsets (e.g.,  ‘pants’) are the shortest, which is consistent with tap productions. Coda rhotics (e.g.,

‘pants’) are the shortest, which is consistent with tap productions. Coda rhotics (e.g.,  ‘spoon’,

‘spoon’,  ‘pig’), on the other hand, have an intermediate duration. This intermediate duration seems to stem from the observation that, even though all types of rhotics can appear in all prosodic positions, there is overall more variation in the types of rhotics produced in the coda. In other words, the distribution of rhotic types is more balanced in coda position than in branching onsets (where they are mostly taps or approximants) or singleton onsets of stressed syllables (where they are mostly trills).

‘pig’), on the other hand, have an intermediate duration. This intermediate duration seems to stem from the observation that, even though all types of rhotics can appear in all prosodic positions, there is overall more variation in the types of rhotics produced in the coda. In other words, the distribution of rhotic types is more balanced in coda position than in branching onsets (where they are mostly taps or approximants) or singleton onsets of stressed syllables (where they are mostly trills).The lateral coda is realized with an alveolar place in both word-final and word-medial position (e.g.,  ‘hat’,

‘hat’,  ‘hot’), although descriptions of the effects of contact between BV and southern Brazilian Portuguese indicate that occasional productions with velarization are also possible (Frosi and Mioranza 1983).1 Velarization of the lateral is not reported in other varieties of Veneto (from Italy and Mexico; e.g., MacKay (2002); Zamboni (1974)). In the syllable onset, the lateral is also realized with an alveolar place in all Veneto dialects—but it can be variably targeted, in BV and other Veneto dialects, by a deletion process when in intervocalic position (Canepari 1976; Guzzo 2023; MacKay 2002; Zamboni 1974). I return to this issue in the next section.

‘hot’), although descriptions of the effects of contact between BV and southern Brazilian Portuguese indicate that occasional productions with velarization are also possible (Frosi and Mioranza 1983).1 Velarization of the lateral is not reported in other varieties of Veneto (from Italy and Mexico; e.g., MacKay (2002); Zamboni (1974)). In the syllable onset, the lateral is also realized with an alveolar place in all Veneto dialects—but it can be variably targeted, in BV and other Veneto dialects, by a deletion process when in intervocalic position (Canepari 1976; Guzzo 2023; MacKay 2002; Zamboni 1974). I return to this issue in the next section.

‘hat’,

‘hat’,  ‘hot’), although descriptions of the effects of contact between BV and southern Brazilian Portuguese indicate that occasional productions with velarization are also possible (Frosi and Mioranza 1983).1 Velarization of the lateral is not reported in other varieties of Veneto (from Italy and Mexico; e.g., MacKay (2002); Zamboni (1974)). In the syllable onset, the lateral is also realized with an alveolar place in all Veneto dialects—but it can be variably targeted, in BV and other Veneto dialects, by a deletion process when in intervocalic position (Canepari 1976; Guzzo 2023; MacKay 2002; Zamboni 1974). I return to this issue in the next section.

‘hot’), although descriptions of the effects of contact between BV and southern Brazilian Portuguese indicate that occasional productions with velarization are also possible (Frosi and Mioranza 1983).1 Velarization of the lateral is not reported in other varieties of Veneto (from Italy and Mexico; e.g., MacKay (2002); Zamboni (1974)). In the syllable onset, the lateral is also realized with an alveolar place in all Veneto dialects—but it can be variably targeted, in BV and other Veneto dialects, by a deletion process when in intervocalic position (Canepari 1976; Guzzo 2023; MacKay 2002; Zamboni 1974). I return to this issue in the next section.Similarly to the Feltrino–Bellunese variety of Veneto and the Trentino and Lombard varieties that were brought to Brazil by immigrants, BV also exhibits variable apocope (Frosi and Mioranza (1983); MacKay (2002); see also Alber (2014)). This phenomenon targets mostly unstressed final /o/ (e.g.,  ‘stone’), but word-final /e/ may also be affected (e.g.,

‘stone’), but word-final /e/ may also be affected (e.g.,  ‘valley’). Apocope may result in productions with a final obstruent (e.g.,

‘valley’). Apocope may result in productions with a final obstruent (e.g.,  ‘piece’ and also the word for ‘stone’ above), as well as with a final consonant cluster (e.g.,

‘piece’ and also the word for ‘stone’ above), as well as with a final consonant cluster (e.g.,  ‘pig’).

‘pig’).

‘stone’), but word-final /e/ may also be affected (e.g.,

‘stone’), but word-final /e/ may also be affected (e.g.,  ‘valley’). Apocope may result in productions with a final obstruent (e.g.,

‘valley’). Apocope may result in productions with a final obstruent (e.g.,  ‘piece’ and also the word for ‘stone’ above), as well as with a final consonant cluster (e.g.,

‘piece’ and also the word for ‘stone’ above), as well as with a final consonant cluster (e.g.,  ‘pig’).

‘pig’).As seen above, nasals, rhotics and laterals can also be found in word-medial coda position. Another coda consonant that can be found in word-medial position in BV and other Veneto varieties is  , whose voicing assimilates to the voicing of the following consonant (e.g.,

, whose voicing assimilates to the voicing of the following consonant (e.g.,  ‘footprint’,

‘footprint’,  ‘to buzz’). In addition,

‘to buzz’). In addition,  also exhibits coda-like behaviour in word-initial s+consonant clusters, as it may assimilate to the voicing of the following consonant (e.g.,

also exhibits coda-like behaviour in word-initial s+consonant clusters, as it may assimilate to the voicing of the following consonant (e.g.,  ‘to break’,

‘to break’,  ‘to shine’; see Goad (2012) for an analysis of s+consonant clusters where /s/ is represented as a coda). S+consonant clusters may also be preceded by an epenthetic vowel, similarly to what is observed in Brazilian Portuguese (e.g.,

‘to shine’; see Goad (2012) for an analysis of s+consonant clusters where /s/ is represented as a coda). S+consonant clusters may also be preceded by an epenthetic vowel, similarly to what is observed in Brazilian Portuguese (e.g.,  ‘to break; Guzzo (2023)). Word-finally,

‘to break; Guzzo (2023)). Word-finally,  is only a coda when apocope applies.

is only a coda when apocope applies.

, whose voicing assimilates to the voicing of the following consonant (e.g.,

, whose voicing assimilates to the voicing of the following consonant (e.g.,  ‘footprint’,

‘footprint’,  ‘to buzz’). In addition,

‘to buzz’). In addition,  also exhibits coda-like behaviour in word-initial s+consonant clusters, as it may assimilate to the voicing of the following consonant (e.g.,

also exhibits coda-like behaviour in word-initial s+consonant clusters, as it may assimilate to the voicing of the following consonant (e.g.,  ‘to break’,

‘to break’,  ‘to shine’; see Goad (2012) for an analysis of s+consonant clusters where /s/ is represented as a coda). S+consonant clusters may also be preceded by an epenthetic vowel, similarly to what is observed in Brazilian Portuguese (e.g.,

‘to shine’; see Goad (2012) for an analysis of s+consonant clusters where /s/ is represented as a coda). S+consonant clusters may also be preceded by an epenthetic vowel, similarly to what is observed in Brazilian Portuguese (e.g.,  ‘to break; Guzzo (2023)). Word-finally,

‘to break; Guzzo (2023)). Word-finally,  is only a coda when apocope applies.

is only a coda when apocope applies.Importantly, the alternation targeting masculine plurals examined in this paper is not exclusive of BV. Many examples in Zamboni (1974) and MacKay (2002) indicate that lateral deletion following pluralization (e.g.,  ) is also found in some Veneto varieties spoken in Italy (including Central Veneto) and in the Chipilo Veneto dialect spoken in Mexico. The analysis proposed here, however, applies only to BV, as it is unclear whether other varieties of Veneto behave similarly to BV with respect to all aspects of pluralization and the related phenomena discussed in what follows.

) is also found in some Veneto varieties spoken in Italy (including Central Veneto) and in the Chipilo Veneto dialect spoken in Mexico. The analysis proposed here, however, applies only to BV, as it is unclear whether other varieties of Veneto behave similarly to BV with respect to all aspects of pluralization and the related phenomena discussed in what follows.

) is also found in some Veneto varieties spoken in Italy (including Central Veneto) and in the Chipilo Veneto dialect spoken in Mexico. The analysis proposed here, however, applies only to BV, as it is unclear whether other varieties of Veneto behave similarly to BV with respect to all aspects of pluralization and the related phenomena discussed in what follows.

) is also found in some Veneto varieties spoken in Italy (including Central Veneto) and in the Chipilo Veneto dialect spoken in Mexico. The analysis proposed here, however, applies only to BV, as it is unclear whether other varieties of Veneto behave similarly to BV with respect to all aspects of pluralization and the related phenomena discussed in what follows.In addition, as will be detailed in Section 6, the plural alternation observed in BV does not stem from contact with Brazilian Portuguese. As will be seen, although the pluralization of word-final laterals in Portuguese involves replacing the lateral with the front semivowel  (e.g.,

(e.g.,  ), the pluralization processes observed in BV and Brazilian Portuguese are independent.

), the pluralization processes observed in BV and Brazilian Portuguese are independent.

(e.g.,

(e.g.,  ), the pluralization processes observed in BV and Brazilian Portuguese are independent.

), the pluralization processes observed in BV and Brazilian Portuguese are independent.The next section discusses the representation of word-final consonants in light of their behaviour in BV phonology.

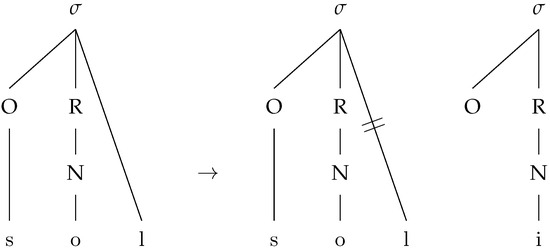

3. The Representation of Word-Final Consonants in BV

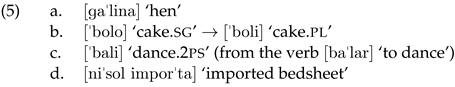

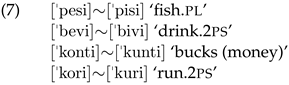

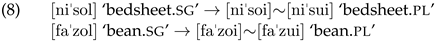

As the examples in (1) and (2) show, masculine nominals ending in a lateral behave differently from nominals ending in a nasal or rhotic consonant. One possible explanation for this alternation is that BV avoids /li/ strings, which would result in the lateral being dropped. However, this does not seem to be the case, as /li/ is allowed in all other phonological contexts, namely, word-internally (5-a), in plurals where /l/ is the onset of a final CV syllable (5-b), in second person singular present verbs where the stem ends in a lateral (5-c) and across words (5-d). The observation that /li/ strings are allowed across word boundaries suggests that different constraints regulate the resyllabification of /l/ within and outside the word domain. We return to this in the discussion section.

An alternative way to account for the data is to propose a phonological mechanism that applies either to the word-final lateral or to the other word-final consonants. In traditional prosodic phonology (building on, e.g., Nespor and Vogel (1986a) and Selkirk (1980)), such a mechanism could be extrametricality, mora assignment (or mora delinking) and mora sharing, and it would target one set of consonants but not the other. However, neither of these possibilities seems applicable to the case of BV. The reason for this is that words with a word-final consonant behave similarly with respect to stress assignment, regardless of the word-final consonant they exhibit. That is, words that end in a nasal, rhotic or lateral all exhibit stress on the final vowel. If any of these final consonants were extrametrical, were assigned (or lost) a mora, or shared a mora with an adjacent vowel, stress assignment in items with such consonants would require a specific form of lexical marking. I further discuss alternative accounts in Section 6.

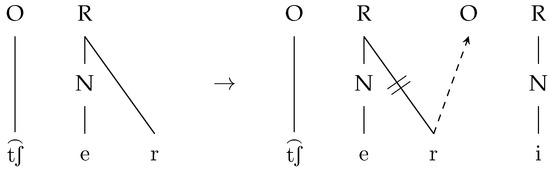

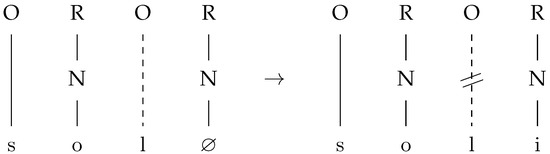

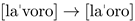

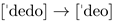

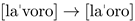

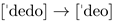

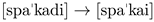

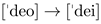

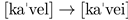

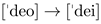

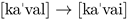

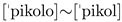

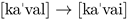

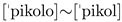

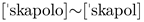

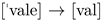

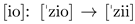

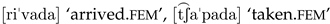

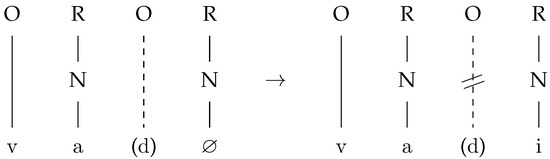

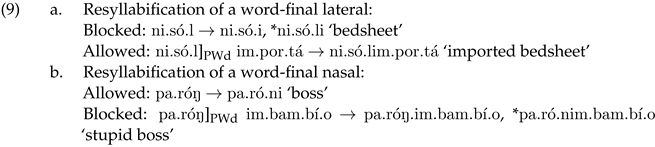

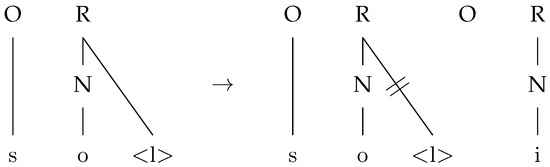

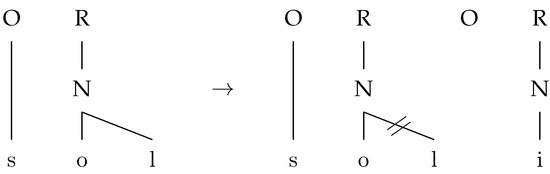

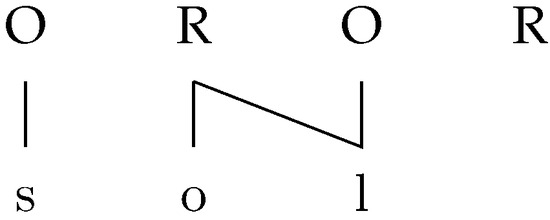

Instead, I propose that the alternation observed in BV plurals can be accounted for if we assume distinct representations for the word-final consonants, in line with Piggott (1999). Specifically, while final nasals and rhotics are represented as codas, final laterals are represented as (weak) onsets of syllables with empty nuclei. These representations are shown in Figure 1 and Figure 2. For the sake of conciseness, these and the representations shown in subsequent sections do not include the syllable node nor the x-skeleton, except when needed.

Figure 1.

The representation of word-final rhotics and nasals.

Figure 2.

The representation of word-final laterals.

In Figure 1 and Figure 2, only the final portion of the words  ‘glass.pl’ and

‘glass.pl’ and  ‘bedsheet.pl’ (from singular

‘bedsheet.pl’ (from singular  ) are shown. In Figure 1, where the final consonant is a coda, resyllabification is allowed. In particular, when the plural suffix is attached, the coda is resyllabified as the onset of the syllable containing the suffix. On the other hand, in Figure 2, the final consonant is an onset, and the the nucleus of its syllable is not filled. The dashed line indicates that it is a weak onset. The attachment of the plural suffix causes the weak lateral onset to be dropped and the result is a VV string. Note that the representation in Figure 2 (as well as some of the subsequent representations) does not make any particular assumption with respect to how the suffix is represented before attaching to the stem (i.e., as the nucleus of a separate syllable or as directly integrated into the empty nucleus).

) are shown. In Figure 1, where the final consonant is a coda, resyllabification is allowed. In particular, when the plural suffix is attached, the coda is resyllabified as the onset of the syllable containing the suffix. On the other hand, in Figure 2, the final consonant is an onset, and the the nucleus of its syllable is not filled. The dashed line indicates that it is a weak onset. The attachment of the plural suffix causes the weak lateral onset to be dropped and the result is a VV string. Note that the representation in Figure 2 (as well as some of the subsequent representations) does not make any particular assumption with respect to how the suffix is represented before attaching to the stem (i.e., as the nucleus of a separate syllable or as directly integrated into the empty nucleus).

‘glass.pl’ and

‘glass.pl’ and  ‘bedsheet.pl’ (from singular

‘bedsheet.pl’ (from singular  ) are shown. In Figure 1, where the final consonant is a coda, resyllabification is allowed. In particular, when the plural suffix is attached, the coda is resyllabified as the onset of the syllable containing the suffix. On the other hand, in Figure 2, the final consonant is an onset, and the the nucleus of its syllable is not filled. The dashed line indicates that it is a weak onset. The attachment of the plural suffix causes the weak lateral onset to be dropped and the result is a VV string. Note that the representation in Figure 2 (as well as some of the subsequent representations) does not make any particular assumption with respect to how the suffix is represented before attaching to the stem (i.e., as the nucleus of a separate syllable or as directly integrated into the empty nucleus).

) are shown. In Figure 1, where the final consonant is a coda, resyllabification is allowed. In particular, when the plural suffix is attached, the coda is resyllabified as the onset of the syllable containing the suffix. On the other hand, in Figure 2, the final consonant is an onset, and the the nucleus of its syllable is not filled. The dashed line indicates that it is a weak onset. The attachment of the plural suffix causes the weak lateral onset to be dropped and the result is a VV string. Note that the representation in Figure 2 (as well as some of the subsequent representations) does not make any particular assumption with respect to how the suffix is represented before attaching to the stem (i.e., as the nucleus of a separate syllable or as directly integrated into the empty nucleus).These representations are able to capture the observation that word-final rhotics and nasals seem to be placeless, which is consistent with their representation as codas (Piggott 1999; Rice 1992). As mentioned previously, coda rhotics can be variably realized in BV (as trills, taps and other forms), word-final nasals are neutralized to  and syllable-final nasals assimilate the place of the following consonant. On the other hand, laterals in all positions are realized as alveolars (with the exception of cases of variable velarization due to contact with Portuguese).

and syllable-final nasals assimilate the place of the following consonant. On the other hand, laterals in all positions are realized as alveolars (with the exception of cases of variable velarization due to contact with Portuguese).

and syllable-final nasals assimilate the place of the following consonant. On the other hand, laterals in all positions are realized as alveolars (with the exception of cases of variable velarization due to contact with Portuguese).

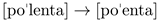

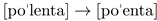

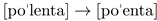

and syllable-final nasals assimilate the place of the following consonant. On the other hand, laterals in all positions are realized as alveolars (with the exception of cases of variable velarization due to contact with Portuguese).Furthermore, the representation of the lateral as a weak onset is consistent with its behaviour in other positions of the word. In BV (and other Veneto varieties), /l/ may be deleted in intervocalic position (e.g.,  ‘polenta’). In some Veneto varieties from Italy (and marginally also in BV; Dal Castel et al. (2021)), intervocalic and word-initial /l/ may also be vocalized (to a semivowel or short vowel) (Belloni 2009; Canepari 1976; Zamboni 1974).2

‘polenta’). In some Veneto varieties from Italy (and marginally also in BV; Dal Castel et al. (2021)), intervocalic and word-initial /l/ may also be vocalized (to a semivowel or short vowel) (Belloni 2009; Canepari 1976; Zamboni 1974).2

‘polenta’). In some Veneto varieties from Italy (and marginally also in BV; Dal Castel et al. (2021)), intervocalic and word-initial /l/ may also be vocalized (to a semivowel or short vowel) (Belloni 2009; Canepari 1976; Zamboni 1974).2

‘polenta’). In some Veneto varieties from Italy (and marginally also in BV; Dal Castel et al. (2021)), intervocalic and word-initial /l/ may also be vocalized (to a semivowel or short vowel) (Belloni 2009; Canepari 1976; Zamboni 1974).2It is important to note that other consonants are also targeted by variable intervocalic deletion in BV, in particular /v/ (e.g.,  ‘work’,

‘work’,  ‘grape’) and /d/ (e.g.,

‘grape’) and /d/ (e.g.,  ‘finger’,

‘finger’,  ‘broken.pl’).3 As these examples and the examples with /l/ suggest, intervocalic consonant deletion may be observed in both stressed and unstressed syllables. I return to this issue in Section 4.2.

‘broken.pl’).3 As these examples and the examples with /l/ suggest, intervocalic consonant deletion may be observed in both stressed and unstressed syllables. I return to this issue in Section 4.2.

‘work’,

‘work’,  ‘grape’) and /d/ (e.g.,

‘grape’) and /d/ (e.g.,  ‘finger’,

‘finger’,  ‘broken.pl’).3 As these examples and the examples with /l/ suggest, intervocalic consonant deletion may be observed in both stressed and unstressed syllables. I return to this issue in Section 4.2.

‘broken.pl’).3 As these examples and the examples with /l/ suggest, intervocalic consonant deletion may be observed in both stressed and unstressed syllables. I return to this issue in Section 4.2.In the following subsection, I explore the patterns of pluralization in BV polysyllabic nominals based on data from the Talian Corpus. We will see that writers’ orthographic forms are very stable, despite the absence of a standardized orthography and the fact that BV is in a contact situation, which provides further support to the representations in Figure 1 and Figure 2.

Polysyllabic Nominals in the Talian Corpus

Before discussing the data on the pluralization of polysyllabic nominals, I will briefly present the features of the Talian Corpus (Garcia and Guzzo 2023). As mentioned above, the corpus is a compilation of materials written in BV. The texts that make up the corpus are newspaper articles (from two newspapers from southern Brazil) and book excerpts. The texts were written by a total of 45 different authors, and are mostly narratives about personal experiences, accounts of the historical struggles of immigration and fictional stories.4

At the moment of data analysis, the Talian Corpus had 237,774 words from 18,804 sentences (Garcia and Guzzo 2023). The corpus was compiled in RData format. Each word in the corpus is phonetically transcribed, syllabified and marked for stress assignment. As described in Garcia and Guzzo (2023), the phonetic transcriptions were obtained using R scripts that matched certain letters or orthographic strings to sounds—these scripts were adapted from the R package Fonology (Garcia 2023). For example, the string gn corresponds to the sound  , while the string ch (found before the letters e and i) corresponds to

, while the string ch (found before the letters e and i) corresponds to  . The scripts also accounted for sounds that are positionally conditioned. For example, the word-final nasal is pronounced as

. The scripts also accounted for sounds that are positionally conditioned. For example, the word-final nasal is pronounced as  , but orthographically represented with n (such as in the word can for

, but orthographically represented with n (such as in the word can for  ‘dog’). In this case, all word-final ns were transcribed as the velar nasal.

‘dog’). In this case, all word-final ns were transcribed as the velar nasal.

, while the string ch (found before the letters e and i) corresponds to

, while the string ch (found before the letters e and i) corresponds to  . The scripts also accounted for sounds that are positionally conditioned. For example, the word-final nasal is pronounced as

. The scripts also accounted for sounds that are positionally conditioned. For example, the word-final nasal is pronounced as  , but orthographically represented with n (such as in the word can for

, but orthographically represented with n (such as in the word can for  ‘dog’). In this case, all word-final ns were transcribed as the velar nasal.

‘dog’). In this case, all word-final ns were transcribed as the velar nasal.Regarding syllabification, R scripts accounting for the phonotactic constraints of the language were employed. Stress assignment was also determined based on orthographic patterns. Most words with irregular stress (i.e., antepenultimate stress, final stress on a CV syllable) displayed an orthographic accent, so stress on these words was marked based on the position of the accent. Since the position of stress is predictable in most other words (i.e., penultimate stress with a final CV syllable, final stress on a CVC syllable), specific scripts were employed to assign stress based on the type of final syllable (CV or CVC) they had. Since BV does not have a standardized grammar/orthography and authors may differ slightly in their spelling, the phonetic transcriptions were subsequently checked for accuracy, and the necessary adjustments were made. To avoid confusion, in this section as well as in the following sections, the corpus data are presented with phonetic rather than orthographic transcription, unless the orthographic forms are necessary for clarity.

As previously mentioned, the objective of the corpus analysis was to check which forms were employed by BV speakers (in this case, the writers of the texts included in the corpus) to indicate the pluralization of nominals. In the case of polysyllabic items, it is possible that writers display variation in how they mark the plural of items ending in a lateral consonant (for example, by writing the plural of a word such as  ‘horse’ sometimes as

‘horse’ sometimes as  and sometimes as

and sometimes as  ). A stable alternation between plural forms with and without the lateral could suggest that the deletion of the lateral is simply the effect of a diachronic rule and that, synchronically, speakers do not have a separate representation for the word-final lateral (relative to the other word-final consonants). In what follows, we will see that this does not seem to be the case.

). A stable alternation between plural forms with and without the lateral could suggest that the deletion of the lateral is simply the effect of a diachronic rule and that, synchronically, speakers do not have a separate representation for the word-final lateral (relative to the other word-final consonants). In what follows, we will see that this does not seem to be the case.

‘horse’ sometimes as

‘horse’ sometimes as  and sometimes as

and sometimes as  ). A stable alternation between plural forms with and without the lateral could suggest that the deletion of the lateral is simply the effect of a diachronic rule and that, synchronically, speakers do not have a separate representation for the word-final lateral (relative to the other word-final consonants). In what follows, we will see that this does not seem to be the case.

). A stable alternation between plural forms with and without the lateral could suggest that the deletion of the lateral is simply the effect of a diachronic rule and that, synchronically, speakers do not have a separate representation for the word-final lateral (relative to the other word-final consonants). In what follows, we will see that this does not seem to be the case.For the present corpus analysis, I used additional R scripts (R Core Team 2023) to extract the relevant data points. All words with three or more segments and ending in the following orthographic strings were initially extracted: l, li, ai, ei, ii, oi, ui, r, ri, n, ni. A total of 43,488 words were obtained. Subsequently, the items were examined individually and with the help of R scripts, since some of the strings matched other structures in BV which are of no interest to the present study. For example, the orthographic strings ni, ri, li could be in plural forms where the corresponding singular forms end in n, r, l, but they could also be in plural forms of singulars ending in no, ro, lo or ne, re, le (which are of no interest). Similarly, the endings ai, ei, ii, oi, ui could be in plurals of singular forms ending in a lateral (e.g.,  ‘hair’), but they could also be in plurals of singular forms that end in a VV string (e.g.,

‘hair’), but they could also be in plurals of singular forms that end in a VV string (e.g.,  ‘finger’). The plurals of singular forms with penultimate or antepenultimate stress that do not end in a consonant were also all excluded.

‘finger’). The plurals of singular forms with penultimate or antepenultimate stress that do not end in a consonant were also all excluded.

‘hair’), but they could also be in plurals of singular forms that end in a VV string (e.g.,

‘hair’), but they could also be in plurals of singular forms that end in a VV string (e.g.,  ‘finger’). The plurals of singular forms with penultimate or antepenultimate stress that do not end in a consonant were also all excluded.

‘finger’). The plurals of singular forms with penultimate or antepenultimate stress that do not end in a consonant were also all excluded.The data inspection also led to the exclusion of items with the following profiles: (a) proper names, (b) verbs in the infinitive (all ending in r), (c) verbs ending in a clitic form (e.g.,  ‘to see them’), (d) other verb forms (e.g.,

‘to see them’), (d) other verb forms (e.g.,  ‘to be able.2pl’), (e) clitic or functional forms (e.g.,

‘to be able.2pl’), (e) clitic or functional forms (e.g.,  ‘in the’,

‘in the’,  ‘you.pl’), (f) adverbs (e.g.,

‘you.pl’), (f) adverbs (e.g.,  ‘already’) and (g) onomatopoeia or exclamations (e.g., aaai ‘ouch’). The remaining items (N = 12,774) were then distributed into three separate word lists: (i) one list containing singular and plural forms of monosyllables (N = 3850), (ii) another list containing plurals of words with stress on a final CV syllable (N = 744), and (iii) another list with singular and plural forms of polysyllabic items (N = 8180). In the remainder of this subsection, we focus on the list in (iii). I return to the lists in (i) and (ii) in Section 4.

‘already’) and (g) onomatopoeia or exclamations (e.g., aaai ‘ouch’). The remaining items (N = 12,774) were then distributed into three separate word lists: (i) one list containing singular and plural forms of monosyllables (N = 3850), (ii) another list containing plurals of words with stress on a final CV syllable (N = 744), and (iii) another list with singular and plural forms of polysyllabic items (N = 8180). In the remainder of this subsection, we focus on the list in (iii). I return to the lists in (i) and (ii) in Section 4.

‘to see them’), (d) other verb forms (e.g.,

‘to see them’), (d) other verb forms (e.g.,  ‘to be able.2pl’), (e) clitic or functional forms (e.g.,

‘to be able.2pl’), (e) clitic or functional forms (e.g.,  ‘in the’,

‘in the’,  ‘you.pl’), (f) adverbs (e.g.,

‘you.pl’), (f) adverbs (e.g.,  ‘already’) and (g) onomatopoeia or exclamations (e.g., aaai ‘ouch’). The remaining items (N = 12,774) were then distributed into three separate word lists: (i) one list containing singular and plural forms of monosyllables (N = 3850), (ii) another list containing plurals of words with stress on a final CV syllable (N = 744), and (iii) another list with singular and plural forms of polysyllabic items (N = 8180). In the remainder of this subsection, we focus on the list in (iii). I return to the lists in (i) and (ii) in Section 4.

‘already’) and (g) onomatopoeia or exclamations (e.g., aaai ‘ouch’). The remaining items (N = 12,774) were then distributed into three separate word lists: (i) one list containing singular and plural forms of monosyllables (N = 3850), (ii) another list containing plurals of words with stress on a final CV syllable (N = 744), and (iii) another list with singular and plural forms of polysyllabic items (N = 8180). In the remainder of this subsection, we focus on the list in (iii). I return to the lists in (i) and (ii) in Section 4.As indicated above, the total number of singular and plural forms of polysyllabic items included in the analysis is 8180. These tokens belong to three major categories: (a) singulars/plurals of words ending in a nasal (N = 4682), (b) singulars/plurals of words ending in a rhotic (N = 1533) and (c) singulars/plurals of words ending in a lateral (N = 1965). Table 1 shows the number of tokens in each of these categories.

Table 1.

Distribution of singular and plural forms in the Talian Corpus (polysyllabic nominals).

For words ending in a rhotic, all of the plurals are formed by adding suffix /-i/. In the case of words ending in a nasal, most of the plurals display suffix /-i/, although a few do not have any suffix, in which case the singular and the plural forms are identical. Further examination of the data5 reveals that only 13 of the 145 items where no suffix is added to a word ending in a nasal are masculine nominals. All other items in this group are feminine nouns ending in a nasal consonant. In this case, alternation between a word-final nasal and a final /ne/ string may be observed in singular forms (e.g.,  ‘attention’). It thus seems like the writers do not add a plural suffix to these forms to avoid what could be perceived as a morphological mismatch: if the plural suffix that usually replaces the theme vowel /-e/ is added (in this case, /-i/), the word would have the same profile as a masculine item; on the other hand, if the feminine plural suffix is added after a word-final nasal (that is, /-e/), the word might be interpreted as singular. If the feminine forms are excluded from the analysis, only a negligible proportion of all the plural forms of items ending in a nasal are produced without the plural suffix (0.9%).

‘attention’). It thus seems like the writers do not add a plural suffix to these forms to avoid what could be perceived as a morphological mismatch: if the plural suffix that usually replaces the theme vowel /-e/ is added (in this case, /-i/), the word would have the same profile as a masculine item; on the other hand, if the feminine plural suffix is added after a word-final nasal (that is, /-e/), the word might be interpreted as singular. If the feminine forms are excluded from the analysis, only a negligible proportion of all the plural forms of items ending in a nasal are produced without the plural suffix (0.9%).

‘attention’). It thus seems like the writers do not add a plural suffix to these forms to avoid what could be perceived as a morphological mismatch: if the plural suffix that usually replaces the theme vowel /-e/ is added (in this case, /-i/), the word would have the same profile as a masculine item; on the other hand, if the feminine plural suffix is added after a word-final nasal (that is, /-e/), the word might be interpreted as singular. If the feminine forms are excluded from the analysis, only a negligible proportion of all the plural forms of items ending in a nasal are produced without the plural suffix (0.9%).

‘attention’). It thus seems like the writers do not add a plural suffix to these forms to avoid what could be perceived as a morphological mismatch: if the plural suffix that usually replaces the theme vowel /-e/ is added (in this case, /-i/), the word would have the same profile as a masculine item; on the other hand, if the feminine plural suffix is added after a word-final nasal (that is, /-e/), the word might be interpreted as singular. If the feminine forms are excluded from the analysis, only a negligible proportion of all the plural forms of items ending in a nasal are produced without the plural suffix (0.9%).Turning to the items ending in a lateral consonant, Table 1 indicates that most of the plurals of such items end in a /Vi/ string (e.g.,  ‘horse’). However, a considerable proportion of the plurals (N = 100, or 11.9% of all the plurals of words ending in a lateral) are formed by adding suffix /-i/ after the word-final lateral. A closer inspection of these data shows that most of the tokens with this profile (N = 85) correspond to words whose singular form may variably display apocope (e.g.,

‘horse’). However, a considerable proportion of the plurals (N = 100, or 11.9% of all the plurals of words ending in a lateral) are formed by adding suffix /-i/ after the word-final lateral. A closer inspection of these data shows that most of the tokens with this profile (N = 85) correspond to words whose singular form may variably display apocope (e.g.,  ‘small’,

‘small’,  ‘bachelor’). It should be noted that the singular items in the corpus that exhibit alternation between a word-final lateral and a word-final /lV/ string are mostly words with antepenultimate stress. Specifically, in the corpus data, 70 out of the 85 items that display this alternation and are pluralized with suffix /-i/ have antepenultimate stress—the other 15 items have penultimate stress. Therefore, the only true exceptions to the observation that the pluralization of such forms involves the deletion of the lateral are (a) the items that do not exhibit variable word-final deletion in their singular forms, and (b) the items that exhibit no plural suffix despite being in a plural context. There are only 19 items (i.e., 2.3% of the 837 total plural forms) with such profiles (15 items with the profile in (a) above and 4 items with the profile in (b)).

‘bachelor’). It should be noted that the singular items in the corpus that exhibit alternation between a word-final lateral and a word-final /lV/ string are mostly words with antepenultimate stress. Specifically, in the corpus data, 70 out of the 85 items that display this alternation and are pluralized with suffix /-i/ have antepenultimate stress—the other 15 items have penultimate stress. Therefore, the only true exceptions to the observation that the pluralization of such forms involves the deletion of the lateral are (a) the items that do not exhibit variable word-final deletion in their singular forms, and (b) the items that exhibit no plural suffix despite being in a plural context. There are only 19 items (i.e., 2.3% of the 837 total plural forms) with such profiles (15 items with the profile in (a) above and 4 items with the profile in (b)).

‘horse’). However, a considerable proportion of the plurals (N = 100, or 11.9% of all the plurals of words ending in a lateral) are formed by adding suffix /-i/ after the word-final lateral. A closer inspection of these data shows that most of the tokens with this profile (N = 85) correspond to words whose singular form may variably display apocope (e.g.,

‘horse’). However, a considerable proportion of the plurals (N = 100, or 11.9% of all the plurals of words ending in a lateral) are formed by adding suffix /-i/ after the word-final lateral. A closer inspection of these data shows that most of the tokens with this profile (N = 85) correspond to words whose singular form may variably display apocope (e.g.,  ‘small’,

‘small’,  ‘bachelor’). It should be noted that the singular items in the corpus that exhibit alternation between a word-final lateral and a word-final /lV/ string are mostly words with antepenultimate stress. Specifically, in the corpus data, 70 out of the 85 items that display this alternation and are pluralized with suffix /-i/ have antepenultimate stress—the other 15 items have penultimate stress. Therefore, the only true exceptions to the observation that the pluralization of such forms involves the deletion of the lateral are (a) the items that do not exhibit variable word-final deletion in their singular forms, and (b) the items that exhibit no plural suffix despite being in a plural context. There are only 19 items (i.e., 2.3% of the 837 total plural forms) with such profiles (15 items with the profile in (a) above and 4 items with the profile in (b)).

‘bachelor’). It should be noted that the singular items in the corpus that exhibit alternation between a word-final lateral and a word-final /lV/ string are mostly words with antepenultimate stress. Specifically, in the corpus data, 70 out of the 85 items that display this alternation and are pluralized with suffix /-i/ have antepenultimate stress—the other 15 items have penultimate stress. Therefore, the only true exceptions to the observation that the pluralization of such forms involves the deletion of the lateral are (a) the items that do not exhibit variable word-final deletion in their singular forms, and (b) the items that exhibit no plural suffix despite being in a plural context. There are only 19 items (i.e., 2.3% of the 837 total plural forms) with such profiles (15 items with the profile in (a) above and 4 items with the profile in (b)).The patterns of pluralization found in the corpus clearly indicate that polysyllabic masculine nominals with word-final laterals behave differently from nominals with other word-final consonants with respect to pluralization. However, to further support the proposal that word-final laterals have a separate prosodic representation from other word-final consonants, evidence from additional structures in the language is needed. The next section examines the pluralization of monosyllables and words with final stress on a CV syllable, to show that the behaviour of these structures is also compatible with this proposal.

4. Evidence from Other Patterns of Pluralization

If we assume that word-final laterals are represented differently from other word-final consonants, additional evidence for such a distinction should be found in the phonological grammar of BV. This section discusses two phenomena that support the idea that there are two possible representations for word-final consonants in BV. These phenomena are the pluralization of monosyllabic nominals (Section 4.1) and the pluralization of words with final stress on a CV syllable (Section 4.2).

4.1. The Pluralization of Monosyllables

Crosslinguistically, it has been observed that monosyllables often behave distinctly from polysyllables, in that they may be realized more faithfully than polysyllables or even spared from certain phonological processes (Alber 2001; Becker et al. 2012; Beckman 1997, 1998; Steriade 1994). Consequently, in a grammar where words of the same shape (for example, CVC) are not syllabified in the same way, differences may arise in the application of processes that are constrained by syllable structure.

Given the representations for word-final consonants in Figure 1 and Figure 2, only items ending in a rhotic or nasal can be monosyllables in BV. In other words, as word-final rhotics and nasals are represented as codas, items of the shape CVC that end in a rhotic or nasal have only one syllable. On the other hand, since word-final laterals are represented as onsets, items of the shape CVC that end in a lateral actually have two syllables. Therefore, if the BV grammar has distinct faithfulness constraints for monosyllables and polysyllables, CVC words ending in a lateral should behave differently from CVC words ending in a rhotic or nasal.

It has been observed that (certain) monosyllables are invariable in BV. Stawinski (1982) provides a non-exhaustive list of such monosyllables that contains masculine nouns such as bó ‘ox’ and can ‘dog’. On the other hand, for masculine CVC nominals ending in a lateral, Stawinski (1982) provides a plural form that is identical to the form found in polysyllables:  ‘beautiful’. It is thus possible that CVC words ending in a rhotic or nasal (i.e., the true monosyllables given the representations in Figure 1 and Figure 2) are constrained by the BV grammar in that they are immune from morphological processes resulting in resyllabification. CVC words ending a lateral, on the other hand, should be able to pluralize following the same patterns observed in longer words, since they are not in fact monosyllables.

‘beautiful’. It is thus possible that CVC words ending in a rhotic or nasal (i.e., the true monosyllables given the representations in Figure 1 and Figure 2) are constrained by the BV grammar in that they are immune from morphological processes resulting in resyllabification. CVC words ending a lateral, on the other hand, should be able to pluralize following the same patterns observed in longer words, since they are not in fact monosyllables.

‘beautiful’. It is thus possible that CVC words ending in a rhotic or nasal (i.e., the true monosyllables given the representations in Figure 1 and Figure 2) are constrained by the BV grammar in that they are immune from morphological processes resulting in resyllabification. CVC words ending a lateral, on the other hand, should be able to pluralize following the same patterns observed in longer words, since they are not in fact monosyllables.

‘beautiful’. It is thus possible that CVC words ending in a rhotic or nasal (i.e., the true monosyllables given the representations in Figure 1 and Figure 2) are constrained by the BV grammar in that they are immune from morphological processes resulting in resyllabification. CVC words ending a lateral, on the other hand, should be able to pluralize following the same patterns observed in longer words, since they are not in fact monosyllables.This hypothesis can be tested by examining the corpus data. As previously mentioned, the Talian Corpus contains a total of 3850 monosyllabic items. Their distribution is shown in Table 2.

Table 2.

Distribution of singular and plural forms in the Talian Corpus (monosyllabic nominals).

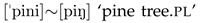

Regarding the CVC nominals ending in a lateral, 32 items have an unexpected plural form: three are formed without a plural suffix, while 29 are formed by adding the plural suffix (without deleting the lateral). However, further examination of the 29 items that have a suffix but no lateral deletion reveals that 24 of such items correspond to words that, in their singular form, can be found with and without a final vowel in the corpus. That is, these 24 items exhibit variable apocope in BV (e.g.,  ‘valley’). The other five items are all plurals of the word

‘valley’). The other five items are all plurals of the word  ‘thread’. In this case, pluralization with the addition of a suffix and lateral dropping would result in an [ii] string. Even though this string is allowed in BV (for example, in the plural of words ending in

‘thread’. In this case, pluralization with the addition of a suffix and lateral dropping would result in an [ii] string. Even though this string is allowed in BV (for example, in the plural of words ending in  ‘uncle’), VV strings where the two vowels are identical are overall marginal in the BV system. Thus, it is possible that this choice of pluralization is simply a way to avoid a sequence of identical vowels.

‘uncle’), VV strings where the two vowels are identical are overall marginal in the BV system. Thus, it is possible that this choice of pluralization is simply a way to avoid a sequence of identical vowels.

‘valley’). The other five items are all plurals of the word

‘valley’). The other five items are all plurals of the word  ‘thread’. In this case, pluralization with the addition of a suffix and lateral dropping would result in an [ii] string. Even though this string is allowed in BV (for example, in the plural of words ending in

‘thread’. In this case, pluralization with the addition of a suffix and lateral dropping would result in an [ii] string. Even though this string is allowed in BV (for example, in the plural of words ending in  ‘uncle’), VV strings where the two vowels are identical are overall marginal in the BV system. Thus, it is possible that this choice of pluralization is simply a way to avoid a sequence of identical vowels.

‘uncle’), VV strings where the two vowels are identical are overall marginal in the BV system. Thus, it is possible that this choice of pluralization is simply a way to avoid a sequence of identical vowels.The overwhelming majority of the CVC nominals ending in a lateral have the expected plural form (N = 412)—that is, they exhibit the plural suffix but no lateral on the surface. Inspection of the data shows that a large portion of these data corresponds to morphologically complex functional items  ‘which.pl’ and

‘which.pl’ and  ‘this.pl’ (from singulars

‘this.pl’ (from singulars  and

and  , respectively). If such items are removed from the analysis, the number of plurals ending in /Vi/ is 92. Still, even if these items are excluded, the vast majority of the CVC items ending in a lateral exhibit the expected plural form: 74.2% are pluralized as /Vi/, while 24.4% are pluralized by adding the suffix (and keeping the lateral) and 0.7% do not have a plural suffix. If

, respectively). If such items are removed from the analysis, the number of plurals ending in /Vi/ is 92. Still, even if these items are excluded, the vast majority of the CVC items ending in a lateral exhibit the expected plural form: 74.2% are pluralized as /Vi/, while 24.4% are pluralized by adding the suffix (and keeping the lateral) and 0.7% do not have a plural suffix. If  and

and  are kept in the analysis, the proportion of CVC items ending in a lateral that exhibit the expected plural form is 92.8%.

are kept in the analysis, the proportion of CVC items ending in a lateral that exhibit the expected plural form is 92.8%.

‘which.pl’ and

‘which.pl’ and  ‘this.pl’ (from singulars

‘this.pl’ (from singulars  and

and  , respectively). If such items are removed from the analysis, the number of plurals ending in /Vi/ is 92. Still, even if these items are excluded, the vast majority of the CVC items ending in a lateral exhibit the expected plural form: 74.2% are pluralized as /Vi/, while 24.4% are pluralized by adding the suffix (and keeping the lateral) and 0.7% do not have a plural suffix. If

, respectively). If such items are removed from the analysis, the number of plurals ending in /Vi/ is 92. Still, even if these items are excluded, the vast majority of the CVC items ending in a lateral exhibit the expected plural form: 74.2% are pluralized as /Vi/, while 24.4% are pluralized by adding the suffix (and keeping the lateral) and 0.7% do not have a plural suffix. If  and

and  are kept in the analysis, the proportion of CVC items ending in a lateral that exhibit the expected plural form is 92.8%.

are kept in the analysis, the proportion of CVC items ending in a lateral that exhibit the expected plural form is 92.8%.Turning to the CVC nominals ending in a rhotic, all the plural forms found in the corpus have a suffix. This observation apparently contradicts the hypothesis that CVC nominals, as monosyllables, should be protected from resyllabification, unlike CVC words ending in a lateral. However, examination of the corpus data shows that all of the items ending in a rhotic and pluralized with a suffix correspond to words that can also be found with a final vowel in their singular form. In other words, similar to what is observed with some of the plurals for CVC items ending in a lateral, all of the plurals of monosyllables ending in a rhotic correspond to words that exhibit variable apocope in BV (e.g.,  ‘iron’.)

‘iron’.)

‘iron’.)

‘iron’.)The patterns for CVC items ending in a rhotic are thus not very elucidative. On the other hand, the pluralization of CVC nominals ending in a nasal is mostly realized without a suffix (e.g.,  ), as expected. Specifically, 238 of the 347 plurals (or 68.6%) exhibit this profile. In addition, variation in the data is observed—for the same lexical item, the plural may be indicated with or without a suffix (e.g.,

), as expected. Specifically, 238 of the 347 plurals (or 68.6%) exhibit this profile. In addition, variation in the data is observed—for the same lexical item, the plural may be indicated with or without a suffix (e.g.,  ). Comparison of the CVC nominals ending in a lateral or in a nasal thus shows that the behaviour of the CVC items ending in a lateral contrasts with the behaviour of the CVC items ending in a nasal. In the case of those ending in a lateral, most items are pluralized by adding a suffix (and deleting the lateral), while, for those ending in a nasal, most items are pluralized with no suffix.

). Comparison of the CVC nominals ending in a lateral or in a nasal thus shows that the behaviour of the CVC items ending in a lateral contrasts with the behaviour of the CVC items ending in a nasal. In the case of those ending in a lateral, most items are pluralized by adding a suffix (and deleting the lateral), while, for those ending in a nasal, most items are pluralized with no suffix.

), as expected. Specifically, 238 of the 347 plurals (or 68.6%) exhibit this profile. In addition, variation in the data is observed—for the same lexical item, the plural may be indicated with or without a suffix (e.g.,

), as expected. Specifically, 238 of the 347 plurals (or 68.6%) exhibit this profile. In addition, variation in the data is observed—for the same lexical item, the plural may be indicated with or without a suffix (e.g.,  ). Comparison of the CVC nominals ending in a lateral or in a nasal thus shows that the behaviour of the CVC items ending in a lateral contrasts with the behaviour of the CVC items ending in a nasal. In the case of those ending in a lateral, most items are pluralized by adding a suffix (and deleting the lateral), while, for those ending in a nasal, most items are pluralized with no suffix.

). Comparison of the CVC nominals ending in a lateral or in a nasal thus shows that the behaviour of the CVC items ending in a lateral contrasts with the behaviour of the CVC items ending in a nasal. In the case of those ending in a lateral, most items are pluralized by adding a suffix (and deleting the lateral), while, for those ending in a nasal, most items are pluralized with no suffix.Therefore, the patterns of pluralization of CVC items are consistent with the proposal that only the CVC items ending in a nasal or rhotic are monosyllables, while those ending in a lateral are instead a string of two syllables. As expected, monosyllables are more resistant to processes with consequences to their phonological structure. With respect to the pluralization of CVC nominals with a final nasal, resyllabification resulting from the addition of the plural suffix is variably blocked. In the case of CVC nominals ending in a lateral, this constraint is not operative, since pluralization does not affect the number of syllables in the word.

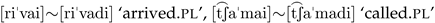

4.2. The Pluralization of Words with Final Stress on a CV Syllable

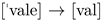

In this subsection, I argue that the pluralization of words with final stress on a CV syllable is also compatible with the representation of word-final laterals as onsets. In general, words that end in a stressed CV syllable are invariable, that is, they are not assigned a plural suffix (6-a) (Dal Castel et al. 2021). However, one specific type of word with final stress on a CV syllable does display plural suffix attachment. This is the case of masculine participles (6-b). As can be noted in (6-b), the plural forms of BV masculine participles are thus very similar on the surface to the plural forms of masculine nominals ending in a lateral.

The behaviour of participles regarding plural assignment is puzzling, as they pattern differently from other words with a final stressed CV syllable, which do not allow the attachment of a plural suffix. Thus, if we assume that the group of words in (6-a) and the group of words in (6-b) have the same syllabification, one of them should be marked somehow, so that it allows (or, instead, blocks) the attachment of the plural suffix. Before positing any special mechanisms that regulate the plural forms in one of these groups, it is necessary to investigate whether they have indeed the same type of syllabification.

One way to do this is to examine the corpus data for participles and plurals involving /Vi/ in BV. In the corpus analysis, all the instances of /Vi/ plurals where the singular form ends in a stressed vowel were placed in a separate list. As mentioned previously, the total number of items on this list is 744. As we will see below, most of these items are participles. In effect, only 30 items are not participles and they correspond to only two types:  (the plural of

(the plural of  ) and

) and  ‘soldier.masc.pl’ (the plural of

‘soldier.masc.pl’ (the plural of  ).

).

(the plural of

(the plural of  ) and

) and  ‘soldier.masc.pl’ (the plural of

‘soldier.masc.pl’ (the plural of  ).

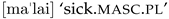

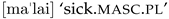

).Further inspection of the corpus data, as well as examination of BV–Portuguese dictionaries (Loregian-Penkal et al. 2023; Luzzatto 2000), indicates that the singular form  ‘soldier’ alternates with

‘soldier’ alternates with  and

and  , and that the feminine form of singular

, and that the feminine form of singular  ‘sick’ is

‘sick’ is  . This suggests that the representation of the words for ‘soldier’ and ‘sick’ has a consonant (/d/) after the stressed vowel.

. This suggests that the representation of the words for ‘soldier’ and ‘sick’ has a consonant (/d/) after the stressed vowel.

‘soldier’ alternates with

‘soldier’ alternates with  and

and  , and that the feminine form of singular

, and that the feminine form of singular  ‘sick’ is

‘sick’ is  . This suggests that the representation of the words for ‘soldier’ and ‘sick’ has a consonant (/d/) after the stressed vowel.

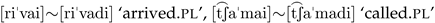

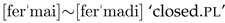

. This suggests that the representation of the words for ‘soldier’ and ‘sick’ has a consonant (/d/) after the stressed vowel.The patterns of pluralization in masculine participles suggests that these items display a similar structure. An additional search of the corpus data has obtained 126 items where the masculine plural participles were written with -adi (and in a few cases -idi, for verbs of the third group)6 instead of /Vi/. For example, alternation was observed in items such as  and

and  .

.

and

and  .

.It should also be noted that feminine participles exhibit a final VCV string where the intervocalic consonant is also /d/ (e.g.,  ) (Stawinski 1982). Furthermore, as previously mentioned, intervocalic /d/ may variably delete in certain lexical items in BV. These observations, as well as the alternation between word-final VCV and /Vi/ strings in masculine participles, indicate that masculine participles, just like the items

) (Stawinski 1982). Furthermore, as previously mentioned, intervocalic /d/ may variably delete in certain lexical items in BV. These observations, as well as the alternation between word-final VCV and /Vi/ strings in masculine participles, indicate that masculine participles, just like the items  and

and  , have an underlying consonant after the stressed vowel. Similar to the word-final lateral, this consonant is the weak onset of a syllable with an empty nucleus. Following from this, plurals such as

, have an underlying consonant after the stressed vowel. Similar to the word-final lateral, this consonant is the weak onset of a syllable with an empty nucleus. Following from this, plurals such as  and participles such as

and participles such as  do not deviate from what is expected for plurals in words with final stress, since they do not actually have stress on the final syllable. Figure 3 shows the representation of a pluralized masculine participle in BV.

do not deviate from what is expected for plurals in words with final stress, since they do not actually have stress on the final syllable. Figure 3 shows the representation of a pluralized masculine participle in BV.

) (Stawinski 1982). Furthermore, as previously mentioned, intervocalic /d/ may variably delete in certain lexical items in BV. These observations, as well as the alternation between word-final VCV and /Vi/ strings in masculine participles, indicate that masculine participles, just like the items

) (Stawinski 1982). Furthermore, as previously mentioned, intervocalic /d/ may variably delete in certain lexical items in BV. These observations, as well as the alternation between word-final VCV and /Vi/ strings in masculine participles, indicate that masculine participles, just like the items  and

and  , have an underlying consonant after the stressed vowel. Similar to the word-final lateral, this consonant is the weak onset of a syllable with an empty nucleus. Following from this, plurals such as

, have an underlying consonant after the stressed vowel. Similar to the word-final lateral, this consonant is the weak onset of a syllable with an empty nucleus. Following from this, plurals such as  and participles such as

and participles such as  do not deviate from what is expected for plurals in words with final stress, since they do not actually have stress on the final syllable. Figure 3 shows the representation of a pluralized masculine participle in BV.

do not deviate from what is expected for plurals in words with final stress, since they do not actually have stress on the final syllable. Figure 3 shows the representation of a pluralized masculine participle in BV.

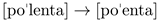

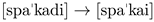

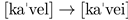

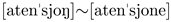

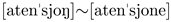

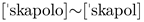

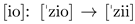

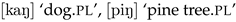

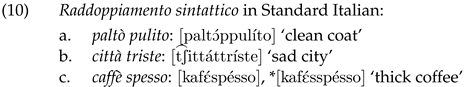

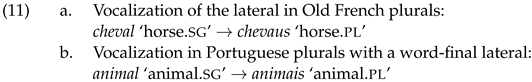

Figure 3.

The representation of the pluralization of masculine participles.

In Figure 3, only the final portion of the word  ‘arrived.pl’ is included. The representation in Figure 3 is almost identical to the representation of word-final laterals shown in Figure 2. These nearly identical representations capture the observation that /d/ and /l/, when in absolute word-final position, are in fact onsets of syllables with empty nuclei. Once material is added to the syllable (such as the masculine plural suffix), this weak onset is deleted, yielding forms with a final /Vi/ string.

‘arrived.pl’ is included. The representation in Figure 3 is almost identical to the representation of word-final laterals shown in Figure 2. These nearly identical representations capture the observation that /d/ and /l/, when in absolute word-final position, are in fact onsets of syllables with empty nuclei. Once material is added to the syllable (such as the masculine plural suffix), this weak onset is deleted, yielding forms with a final /Vi/ string.

‘arrived.pl’ is included. The representation in Figure 3 is almost identical to the representation of word-final laterals shown in Figure 2. These nearly identical representations capture the observation that /d/ and /l/, when in absolute word-final position, are in fact onsets of syllables with empty nuclei. Once material is added to the syllable (such as the masculine plural suffix), this weak onset is deleted, yielding forms with a final /Vi/ string.

‘arrived.pl’ is included. The representation in Figure 3 is almost identical to the representation of word-final laterals shown in Figure 2. These nearly identical representations capture the observation that /d/ and /l/, when in absolute word-final position, are in fact onsets of syllables with empty nuclei. Once material is added to the syllable (such as the masculine plural suffix), this weak onset is deleted, yielding forms with a final /Vi/ string.However, there is one important difference between the singular forms of nominals ending in a lateral and the singular form of masculine participles. In singular words with a word-final lateral, the lateral is always realized on the surface (e.g.,  ‘bedsheet’). On the other hand, the final consonant in singular participles is not present on the surface form (e.g.,

‘bedsheet’). On the other hand, the final consonant in singular participles is not present on the surface form (e.g.,  ‘arrived’). This may be due to a sonority issue: only sonorous consonants may surface at the right word edge in BV. While this requirement allows the realization of laterals, rhotics and nasals at the word edge (despite their different syllabic representations), it blocks word-final /d/ from appearing in this position on the surface form.7

‘arrived’). This may be due to a sonority issue: only sonorous consonants may surface at the right word edge in BV. While this requirement allows the realization of laterals, rhotics and nasals at the word edge (despite their different syllabic representations), it blocks word-final /d/ from appearing in this position on the surface form.7

‘bedsheet’). On the other hand, the final consonant in singular participles is not present on the surface form (e.g.,