1. Introduction

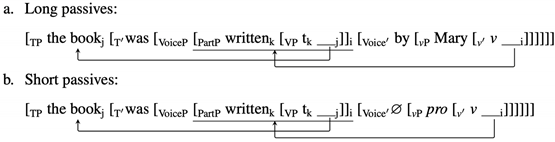

This study presents evidence from Mandarin child language in support of the claim that in this language, the external argument (EA) of passives is not syntactically projected when it is not pronounced (see

Huang 1999). This contrasts analyses of the passive in languages, such as English, where it has been claimed that the EA is always syntactically projected even when phonologically null (e.g.,

Roberts 1987;

Baker et al. 1989;

Collins 2005;

Grillo 2008;

Angelopoulos et al. 2023; cf.

Bruening 2013). Our argument is based on the cross-linguistic examination of children’s performance on passives in English and Mandarin: in English young children exhibit difficulties even when the

by-phrase is not pronounced, while in Mandarin—as we will show—children perform in an adult-like fashion with short passives by age 3 but significantly worse with long passives, those that include an explicit EA, until age 5–6. We interpret this as empirical evidence for a syntactic distinction of the respective adult grammars (see

Angelopoulos et al. 2023) and propose a learning path that addresses the learnability problem posed by implicit EAs in short passives.

1.1. Long and Short Passives in English and Other Child Languages

In many languages, including English and Mandarin, passives may occur with or without a phonologically explicit EA (e.g.,

by-phrase in English), with the two variants conventionally referred to as “long” (1a) and “short” passives (1b), respectively.

| (1) | a. | The dog was bitten by the cat. |

| | b. | The dog was bitten. |

There is a long-standing debate surrounding children’s performance on short and long passives. With regard to production, previous studies show a clear pattern—long passives are much rarer than short passives in both elicited and spontaneous language. For instance,

Horgan (

1978) showed that English-speaking children aged 2 to 13 (

n = 234) produce far more short passives than long passives in picture description tasks. The same short > long passive production asymmetry has been replicated in subsequent studies in child English (e.g.,

Baldie 1976;

Horgan 1978;

Gordon and Chafetz 1990), as well as in many other languages, even those in which the early acquisition of passives is observed. For example, Sesotho-speaking children are reported to acquire passives relatively early (e.g.,

Demuth 1989;

Demuth et al. 2010;

Kline and Demuth 2010; cf.

Crawford 2005). Still, a longitudinal study of the spontaneous production of four Sesotho-speaking children aged 2;1–4;2 showed that long passives are less frequent than short passives in all age intervals; overall only 21% of these children’s passives are long (

Demuth 1989;

Kline and Demuth 2010; see also

Pye and Poz 1988 on K’iche’ and

Allen and Crago 1996 on Inuktitut for similar results).

In terms of comprehension, although some experiments have found slightly better performance on short passives than long passives, these differences have not generally reached statistical significance (see

Table 1 for an overview). For example,

Hirsch and Wexler (

2006) found equal performance with short passives and long passives in 54 out of the 60 English-speaking children that they tested.

Armon-Lotem et al. (

2016) conducted a large-scale cross-linguistic study on 5-year-old children’s comprehension of actional passives in eight languages that have both long and short passives and they found that children performed significantly better on short passives than on long passives in Catalan, Dutch, German, Hebrew, Lithuanian, and Polish, but not in English or Danish. These findings suggest cross-linguistic differences in children’s comprehension of long vs. short passives.

In addition to the mixed results in the literature regarding the earlier acquisition of short passives as compared to long passives, in some languages, short passives are structurally ambiguous between verbal passives and adjectival constructions, making it hard to determine children’s linguistic knowledge of the passive on the basis of their performance on short passives. As we will discuss in more detail below, Mandarin short passives are not ambiguous in this way, providing a clearer window into children’s knowledge of passives that is not available in many other previously examined languages.

1.2. Accounts of the Acquisition of the Passive

Some grammar-based accounts argue that the child’s grammar must mature before the syntactic mechanisms required to derive passives become available. For example,

Borer and Wexler (

1987,

1992), in their seminal A-Chain Deficit Hypothesis (ACDH), proposed that the ability to form A-chains undergoes biological maturation at around age 5 to 6. This explanation raised the question of why children were able to produce short passives at a young age. To address this concern, they posited that children only appear to have an adult-like representation of (actional) short passives, but that they instead adopt an “adjectival strategy”, which involves a simpler structure and leads them to an alternative but closely related interpretation.

1| (2) | The door was closed |

| | a. | Verbal passive interpretation: someone closed the door |

| | b. | Adjectival interpretation: the door was in a closed state |

This strategy relies on the fact that passives are sometimes homophonous with adjectival constructions across languages. Borer and Wexler observe that the presence of a by-phrase is typically only compatible with true passives (e.g., the door was opened by the teacher vs. *the door was open by the teacher), and hence, the use of an adjectival strategy by immature children could explain the apparent earlier production (and comprehension) of short passives.

On the other hand, recent research has demonstrated that young children have no difficulty forming A-chains for various structures, including subject raising to Spec,TP position (e.g.,

Stromswold 1996), raising to object (

Kirby 2010), raising to subject without an intervening experiencer (

Orfitelli 2012;

Mateu and Hyams 2019;

Mateu 2020), and unaccusative constructions (

Snyder et al. 1995;

Friedmann 2007;

Shimada and Sano 2007;

Friedmann and Costa 2010;

Snyder and Hyams 2015;

Mateu et al. 2023; cf.

Babyonyshev et al. 2001). These findings suggest that accounts, such as the ACDH, which predict a similar developmental timeline for passives and other A-movement structures, are no longer tenable.

More recent accounts of the acquisition of the passive have relied on the notion of intervention, specifically featural Relativized Minimality (fRM; e.g.,

Rizzi 1990,

2001,

2018;

Starke 2001), defined in (3).

| (3) | Featural Relativized Minimality (fRM, adapted from Rizzi 2018, p. 347): |

| | In [. . .X . . .Z . . .Y. . . ] a dependency between X and Y is disrupted when: |

| | (i). | X c-commands Z and Z c-commands Y, and |

| | (ii). | Z matches X in terms of relevant syntactic features. |

| | (iii). | The degree of disruption is a function of the featural dis-tinctness of X with respect to Z, in accordance with the distinctness hierarchy. |

This locality constraint was originally postulated to account for the graded judgments of weak

wh-islands in adult grammars. Crucially, according to proponents of fRM, child and adult grammars have different tolerance levels for featural overlap between the target X and an intervener Z (e.g.,

Friedmann et al. 2009;

Belletti et al. 2012). While the adult grammar only completely rules out configurations that involve identity or complete overlap of the relevant morphosyntactic features between X and Z, e.g., [+Q] in

wh-islands, children also have difficulties with inclusion configurations. These inclusion configurations occur when one DP moves past another DP and the set of features of one is properly included in the featural set of the other. Previous child studies have observed such intervention difficulties with overlapping features, such as the NP type (e.g.,

Hebrew:

Friedmann et al. 2009;

English:

Choe 2013) or grammatical number (e.g.,

Italian:

Adani et al. 2010;

English:

Adani et al. 2014;

Spanish:

Mateu 2022). Furthermore, these studies have also found that if the moved element and the intervener mismatch in these features, children’s intervention difficulties decrease, compared to when the set of features fully match. For instance,

Belletti et al. (

2012) found that while object-relative clauses pose severe difficulty to Hebrew-speaking children, when the grammatical gender of the embedded subject mismatched with the relativized object, children’s performance significantly improved.

These results are also compatible with domain-general psycholinguistic approaches to locality, such as Similarity-based Interference, which has been proposed in parallel to fRM for adult language processing (SBI,

Gordon et al. 2001,

2004;

Lewis et al. 2006;

McElree 2000;

Van Dyke and McElree 2006; a.o.) Under this approach, interference arises when the retrieval of an NP is disturbed by another one whose cues are similar, and as with the grammar-based fRM, the more cues are shared between the two elements, the more difficult it is to parse a sentence. However, fRM and SBI are different in two respects: SBI holds that (i) intervention is linearly based, and not only hierarchical in nature and (ii) a broader range of features, including morphosyntactic, e.g., number (

Gordon et al. 2001;

Van Dyke 2007;

Villata et al. 2018;

Villata and Franck 2020), semantic, e.g., occupations (

Lowder and Gordon 2014;

Van Dyke 2007;

Van Dyke and McElree 2011), and possibly phonological features (

Acheson and MacDonald 2011), may lead to interference or working-memory overload. Our study was not designed to adjudicate between these different models. However, in this paper, we will adopt the language and assumptions of fRM, which predicts difficulties establishing a dependency when there is a structurally intervening NP, whether it is pronounced or not.

Empirical acquisition evidence for an implicit EA in English comes from

Orfitelli (

2012), who examined two potential intervention constructions—verbal passives and subject-to-subject raising (StSR). In her experiments with 4- to 6-year-olds (

n = 30), she found that children’s comprehension of English StSR was poor with StSR predicates that select an intervening experiencer (whether overt or not), such as

seem and

appear, but good with “non-experiencer” StSR predicates, such as

(be) about or

(be) likely, which do not. Even when the experiencer is implicit in the sentence, an StSR with an experiencer predicate (5a) was more challenging for children to understand than StSR with a non-experiencer predicate (5b).

2| (5) | a. | The dog seems (to me) to be purple. | (StSR with an experiencer predicate) |

| | b. | The pig is about to roll in the mud. | (StSR with a non-experiencer predicate) |

Orfitelli found a near-perfect within-subject correspondence in the acquisition of StSR experiencer sentences and non-actional verbal passives (i.e., passives which cannot be analyzed as adjectival constructions in English). If a child exhibited delays in one of these structures, they also experienced delays in the other. Conversely, if a child had mastered one of these structures, they had also mastered the other (see

Hirsch 2011 for similar correlated pattern of results). Based on these findings, Orfitelli argued that the implicit, yet structurally present, EA triggers intervention, thus leading to delayed comprehension of both short passives and long passives in English.

1.3. Mandarin Passives

In Mandarin, canonical passives are constructed with the passive marker

bei, and as in English, Mandarin passives can be long, with an expressed EA (6b), or short, lacking an expressed EA, (6c).

| (6) | a. | Lisi | da | le | Zhangsan | | (Active) |

| | | Lisi | hit | PERF | Zhangsan | | |

| | | ‘Lisi hit Zhangsan’ | | |

| | b. | Zhangsani | bei | Lisi | da | le ___i | (Long bei-passive) |

| | | Zhangsan | BEI | Lisi | hit | PERF | |

| | | ‘Zhangsan was hit by Lisi.’ | | |

| | c. | Zhangsani | bei | da | le ___i | | (Short bei-passive) |

| | | Zhangsan | BEI | hit | PERF | | |

| | | ‘Zhangsan was hit.’ | | |

In this paper, we abstract away from the technical details of deriving

bei-passives in Mandarin (see

M. Liu 2023 for a detailed overview). Instead, our analysis of its derivation is based on three important properties of

bei-passives observed in previous literature: firstly, the internal argument (IA) of both long and short

bei-passives undergoes movement to the surface subject position, as diagnosed by island effects (

F. Chen 2023). Secondly, the surface subject in both long and short Mandarin passives is in an A-position, as evidenced by its ability to bind anaphors in the complement of

bei, as well as the fact that long

bei-passives do not show weak crossover (WCO) or reconstruction effects (

M. Liu 2023). Lastly, the EA in long

bei-passives functions as an embedded subject that c-commands the gap of the IA (see 7a below), as evidenced by its binding capabilities (e.g.,

Y.-H. Li 1990;

Chiu 1993;

Ting 1998;

Huang 1999;

Huang et al. 2009; cf.

Ngui 2021). Combining these three points, we now have a clearer picture of the syntactic derivation of

bei-passives: the IA moves to the surface subject position that c-commands the rest of the structure, passing by the EA in long

bei-passives, which is an embedded subject, as shown below in (7a). Important to our acquisition study, this EA in long

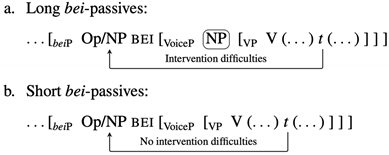

bei-passives could cause intervention difficulties for children’s comprehension, as predicted by fRM.

However, it is not clear yet whether the same movement would also cross an implicit EA in short

bei-passives, triggering the same intervention effects by implicit arguments observed in child English (see

Section 1.2 for a discussion on

Orfitelli (

2012)). Previous literature has hypothesized the lack of a structurally present EA in short passives (e.g.,

Huang 1999), as we discuss in more detail in

Section 2. Consequently, intervention accounts of children’s delays with the passive predict that, all else being equal, Mandarin-speaking children should find long passives more challenging to comprehend than short passives due to the intervention of the EA, as we abstractly represent in (7).

| (7) | Structure of Mandarin long and short bei-passives: |

![Languages 09 00236 i002 Languages 09 00236 i002]() |

Moreover, Mandarin passives, marked by

bei, are never homophones of adjectival constructions, as shown in (8), in contrast to English and many Romance languages.

| (8) | a. | men | bei | guan | le | (Short bei-passive) |

| | | door | BEI | close | PERF | |

| | | ‘The door was closed.’ | |

| | b. | guan(-zhe) | de | men | | (Adjectival construction) |

| | | close-DUR | DE | door | | |

| | | ‘the closed door’ | | |

Therefore, children’s superior performance with short passives over long ones in Mandarin cannot be attributed to an adjectival strategy. In the following section, we provide a brief overview of some previous studies of the acquisition of the Mandarin passive.

1.4. Acquisition of Mandarin Passives

Early studies of child Mandarin passives indicate that

bei-passives emerge early in production, between the ages of 2;06 and 3 (e.g.,

Tse et al. 1991;

Zhou et al. 1992). A more recent, larger-scale study by

Deng et al. (

2018) has further confirmed that young Mandarin-speaking children (range = 0;11–3;5,

n = 86) correctly produce passives from early on. Interestingly, a longitudinal study by

Hu (

2013) found that Mandarin-speaking children (

n = 2) begin producing grammatical long (actional) passives first, at around the age of 3, and short (actional) passives later, at approximately 3;6.

However, the results of experimental studies testing comprehension seem to conflict with the production data.

Xu and Yang (

2008), in a two-choice sentence-picture matching task with Mandarin-speaking children aged 3- to 5-years old (

n = 48), found that although 4-year-olds demonstrated adult-like comprehension of short actional passives, even the oldest group examined (5-year-olds) struggled with long actional passives (see also

Chang 1986). Similarly, in two large-sample experiments with Mandarin-speaking 2- to 6-year-olds (range = 2;00–6;11,

M = 4;03,

n = 812),

H. Liu and Ning (

2009) found a delayed acquisition of Mandarin long passives in both comprehension (compared to active

ba-constructions) and production (compared to unaccusatives). In a two-choice sentence-picture matching task, even the oldest age group (6-year-olds) exhibited below-chance performance with long

bei-passives (41% correct), while their performance with

ba-actives was at the ceiling (94%).

3 Zeng et al.’s (

2016) study, on the other hand, suggests a delayed acquisition of Mandarin short passives as well. In a four-choice sentence-picture matching task, they found that 4-year-olds tended to choose pictures depicting stative readings (46.8%) over eventive readings (34.3%) for eventive short passives. They thus concluded that young children have a non-adultlike interpretation of short passives.

4In summary, the Mandarin literature shows a mixed picture. Corpus studies suggest that bei-passives in general are produced from an early age and that long passives may occur earlier than short passives. Experimental studies, on the other hand, suggest that children exhibit difficulties comprehending passives, possibly both short and long. Given the conflicting results and the methodological concerns in some studies (see endnotes 3 and 4), we seek to provide additional evidence relevant to this research question: do Mandarin-speaking children acquire both short and long verbal passives at the same time, similar to English-speaking children? Or do they show an asymmetry between long and short passives, likely due to a structural difference between short passives in these two languages, viz. the presence vs. absence of a syntactically represented EA in short passives? In the next section, we review the syntactic evidence bearing on this question.

2. On the Syntactic Status of the Implicit External Argument in English and Mandarin

Although it has been argued that the implicit EA in Mandarin is not projected (e.g.,

Huang 1999;

Bruening and Tran 2015;

Z. Chen and Li 2021), there has been no attempt to address this question using established diagnostics. In the following sections, we carefully compare English and Mandarin using diagnostics previously employed to detect syntactically projected null arguments. To anticipate our findings, while the syntactic evidence for the lack of an implicit EA in Mandarin is not conclusive, our acquisition study provides evidence consistent with the hypothesis that there is no syntactically projected EA in Mandarin short passives, in contrast to English. In this section we look at the syntactic evidence and we then turn to our acquisition studies (

Section 3 and

Section 4).

In English short passives, the implicit EA (i) can control PRO subjects of secondary predicates, adjuncts, and purpose clauses, (ii) can license agent-oriented adverbs, and (iii) can bind an anaphor, suggesting that the implicit EA is syntactically represented. However, these diagnostics yield mixed results in Mandarin. We discuss each test individually.

2.1. Secondary Predicates and Control

2.1.1. Evidence from English

In English, stage-level predicates can function as depictive secondary predicates (e.g.,

Simpson 2005), as illustrated in the active sentences in (9).

6| (9) | a. | Mary ate the fishi [PROi raw] | (IA-oriented depictive secondary predicate) |

| | b. | Maryi ate the fish [PROi nude] | (EA-oriented depictive secondary predicate) |

Depictive secondary predicates in English can also modify the implicit EA in short passives (e.g.,

Roeper 1987;

Collins 2005;

Meltzer-Asscher 2012; cf.

Landau 2010), suggesting that there is a syntactically represented null EA binding the PRO subject in the small clause, as shown in (10).

Furthermore, we note that in English, such EA-oriented secondary predicates are not licensed when there is no EA projection, such as in unaccusatives in (11a/12a), in contrast to short passives (cf. 11b/12b). The grammaticality of small clauses under actives, long passives, and short passives, but not unaccusatives, implies the presence of a projected null EA in English short passives that licenses the PRO subject.

| (11) | a. | *The door opened [PRO kneeling]. |

| | b. | The door was opened EAi [PROi kneeling]. |

| (12) | a. | *The feast could finish [PRO alone]. |

| | b. | The feast could be finished EAi [PROi alone]. |

Control of PRO by the EA is also possible in other adjuncts, such as manner (13a) and temporal (14a) adjunct clauses, in contrast with unaccusatives in both cases (13b/14b). Similarly, control into a purpose clause is possible in English with short passives but not unaccusatives, as shown in (15) (from

Roeper 1987, p. 268).

| (13) | a. | The door was opened EAi [PROi using a stick]. |

| | b. | *The door opened [PRO using a stick]. |

| (14) | a. | The door was locked EAi before [PROi leaving on Friday night]. |

| | b. | *The door locked before [PRO leaving on Friday night] |

| (15) | a. | The boat was sunk EAi to [PROi collect the insurance]. |

| | b. | *The boat sank to [PRO collect the insurance]. |

2.1.2. Evidence from Mandarin

The same control tests show mixed results in Mandarin short passives. With respect to secondary predicates, Mandarin lacks small clauses of the English type exemplified in (9–10) (e.g.,

Paul 2021). Instead, secondary predicates occur as adjunct clauses in Mandarin. Importantly, a PRO subject in an adjunct clause is licensed in actives (16a) and long passives (16b), but not in short passives (16c) or unaccusatives (16d) (see also

Chiu 1993). This contrast potentially suggests the absence of a controlling EA in Mandarin short passives. When the adjunct phrase does not contain a PRO to be controlled, such as the examples in (17), the differences observed in (16) disappear.

| (16) | a. | Lisii [PROi | zhan-zai | waimian] | dakai | le | men | | (Active) |

| | | Lisi | stand-at | outside | open | PERF | door | | |

| | | ‘Lisii opened the door PROi standing outside.’ | | |

| | b. | men | bei | Lisii [PROi | zhan-zai | Waimian] | dakai | le | (Long passive) |

| | | door | BEI | Lisi | stand-at | outside | open | PERF | |

| | | ‘The door was opened by Lisii PROi standing outside.’ | | |

| | c. | *men | bei [PRO | zhan-zai | waimian] | dakai | le | | (Short passive) |

| | | door | BEI | stand-at | outside | open | PERF | | |

| | | Intended: ‘The door was opened standing outside.’ | | |

| | d. | *men | [PRO | zhan-zai | waimian] | dakai | le | | (Unaccusative) |

| | | door | | stand-at | outside | open | PERF | | |

| | | Intended: ‘The door opened standing outside.’ | | |

| (17) | a. | Lisii | [cong | waimian] | dakai | le | men | | (Active) |

| | | Lisi | from | outside | open | PERF | door | | |

| | | ‘Lisii opened the door from the outside.’ | | |

| | b. | men | bei | Lisii | [cong | Waimian] | dakai | le | (Long passive) |

| | | door | BEI | Lisi | from | outside | open | PERF | |

| | | ‘The door was opened by Lisii from the outside.’ | | |

| | c. | men | bei | [cong | waimian] | dakai | le | | (Short passive) |

| | | door | BEI | from | outside | open | PERF | | |

| | | ‘The door was opened from the outside.’ | | |

| | d. | men | | [cong | waimian] | dakai | le | | (Unaccusative) |

| | | door | | from | outside | open | PERF | | |

| | | ‘The door opened from outside.’ | | |

So far, we have seen that in English, but not in Mandarin, the implicit EA of short passives can control into secondary predicates and adjunct clauses. However, in other respects, Mandarin parallels English. For example, Mandarin short

bei-passives can license purpose clauses headed by

lai, which selects a clause with a PRO subject (e.g.,

Liao and Lin 2019) (18a), while unaccusatives cannot (18b) (cf. (15) in English).

| (18) | a. | zhe-sou | chuan | bei | ji-chen | le | lai [PRO | pian | bao] |

| | | this-CLF | ship | BEI | hit-sink | PERF | to | defraud | insurance |

| | | ‘This ship was sunk to defraud the insurance money.’ |

| | b. | *zhe-sou | chuan | | ji-chen | le | lai [PRO | pian | bao] |

| | | this-CLF | ship | | hit-sink | PERF | to | defraud | insurance |

| | | Intended: ‘This ship sunk to defraud the insurance money.’ |

However, this diagnostic is not necessarily informative because purpose clauses allow for non-obligatory control (

Landau 2000,

2021) in both languages, as illustrated in (19), in which there is no possible controller.

| (19) | a. | Grass is green [to promote photosynthesis].

(Williams 1985; cf. Bhatt and Pancheva 2017) |

| | b. | ?fangzi | ai-ai-de | [lai | bimian | daota] |

| | | house | short-short-DE | to | avoid | collapse |

| | | ‘The house is low to avoid collapsing.’ |

2.2. Agent-Oriented Adverbials

Previous studies arguing for a syntactically represented EA in Mandarin short passives have also drawn evidence from “agent-oriented” adverbials (e.g.,

Zhang 2010). The premise is that these adverbials, such as

guyi “intentionally”, need to be associated with a projected agent. These adverbs are allowed in both Mandarin short passives (20) and their English counterparts (translation of (20)). Hence, the argument goes, there is a phonologically null agent represented in both structures and both languages.

| (20) | men | bei | guyi | dakai | le |

| | door | BEI | intentionally | open | PERF |

| | ‘The door was intentionally opened.’ |

However, the presence of these adverbials does not necessarily imply that the agent in short passives is syntactically projected. In the examples below (adapted from

Bruening and Tran 2015, pp. 143–44), the so-called agent-oriented adverbials can modify adjectival and nominal predicates that lack an agent, both in English (21a) and Mandarin (21b). They can also occur in unaccusatives, in both English (22a) and Mandarin (22b).

| (21) | a. | (George is a mutant who can control his own height.) George, are you unusually tall today deliberately/intentionally/on purpose? |

| | b. | ni | jintian | guyi | zheme | gao | ma |

| | | you | today | intentionally | so | tall | Q |

| | | ‘Are you intentionally so tall today?’ (under the same context as (22a)) |

| (22) | a. | The robot broke open deliberately. |

| | b. | men | | guyi | kai-zhe | |

| | | door | | intentionally | open-DUR | |

| | ‘The door is intentionally open.’ |

Furthermore, it should be noted that not all adverbials that are semantically associated with the agent are possible in short passives. Here, we discuss a Mandarin example,

duzi “alone, by oneself”. This adverb is associated with the explicit EA in an active sentence (23a) or the implicit EA in clauses involving a PRO subject (23b, c). It is also grammatical in long passives (23d).

| (23) | a. | Mali | duzi | dakai | le | zhe-shan | men | | |

| | | Mali | alone | open | PERF | this-CLF | door | | |

| | | ‘Mali opened this door alone.’ |

| | b. | [PROArb | duzi | dakai | zhe-shan | men] | shi | hen | nan-de |

| | | | alone | open | This-CLF | door | be | very | difficult-DE |

| | | ‘Opening this door alone is very difficult.’ |

| | c. | Lisi | yao | Malii | [PROi | duzi | dakai | zhe-shan | men] |

| | | Lisi | ask | Mali | | alone | open | this-CLF | door |

| | | ‘Lisi asks Mali to open this door alone.’ |

| | d. | zhe-shan | men | bei | Mali | duzi | dakai | le | |

| | | this-CLF | door | BEI | Mali | alone | open | PERF | |

| | | ‘This door was opend by Mali alone.’ |

However,

duzi is not possible in short passives (24a). In this respect as well, short

bei-passives are parallel to unaccusatives (24b), which also do not contain an EA projection.

| (24) | a. | *zhe-shan | men | bei | duzi | dakai | le |

| | | this-CLF | door | BEI | alone | open | PERF |

| | | Intended: ‘This door was opened alone.’ |

| | b. | *zhe-shan | men | | duzi | kai | le |

| | | this-CLF | door | | alone | open | PERF |

| | | Intended: ‘This door opened alone.’ |

2.3. Binding

Lastly, evidence from Binding Principle A, which requires anaphors to be bound in their domain, also suggests that the EA of short passives in English is syntactically projected. As shown in (25) (Internet examples collected by

Collins 2024), reflexives bound by the EA can take different person features. This suggests that the EA is a silent definite pronoun and not simply an existentially closed variable, which is what is typically assumed under analyses that posit no structurally present EA (e.g.,

Bruening 2013;

Legate 2014).

| (25) | a. | Most of this blog is self-deprecating humor aimed EAi at myselfi as much as others. |

| | b. | I would really appreciate it if any negative feelings you have toward teen mothers were kept EAi to yourselvesi. |

| | c. | Mike Tyson bought over 200 cars throughout his career, totaling at 4.5 million. Many were bought EAi for himselfi and others as gifts for his friends and family. |

In Mandarin, binding diagnostics seem to mirror those of English. Reflexives are allowed in short

bei-passives given the appropriate context. For example, in (26), the choice of reflexive—whether first, second, or third person—arguably depends on the person of the implicit EA, the agent of a sending event. Following Collins’ argument for English, this evidence might suggest that there is an implicit EA binding the reflexive and that this null pronoun has person features.

| (26) Context: I/You/Maryi needed to send out a report to a company but I/you/shei made a mistake and sent it to myself/yourself/herselfi. |

| na-fen | baogao | bei | fa-gei | le | wo-ziji/ni-ziji/ta-ziji |

| that-CLF | report | BEI | send-to | PERF | 1SG-self/2SG-self/3SG-self |

| ‘That report was sent to myself/yourself/herself.’ |

However, Mandarin reflexives can be logophoric, hence do not require a local antecedent (e.g.,

Yu 1996;

Pan 1998;

Y. Liu 2020;

Lyu and Kaiser 2023; cf.

Cole et al. 2006). This is shown in (27), which presents the same sentence and reflexives as (26) but with a different context. In (27), the antecedent of the reflexive is interpreted not as the implicit agent of

send (i.e., the lawyer), but rather as the subject of the previous sentence, (i.e., I/You/She, the writer of the report), which is not in a local or c-commanding position with respect to the reflexive.

| (27) Context: I/You/Maryi wrote a report to a company but a lawyerj took it out. However, the lawyerj made a mistake and sent it back to me/you/heri. |

| na-fen | baogao | bei | fa-gei | le | wo-ziji/ni-ziji/ta-ziji |

| that-CLF | report | BEI | send-to | PERF | 1SG-self/2SG-self/3SG-self |

| ‘That report was sent to myself/yourself/herself.’ |

Given the logophoric option, the reflexives in (26) do not provide conclusive evidence of an implicit EA. Thus, the binding diagnostic remains inconclusive in Mandarin.

2.4. Interim Summary and Goal of Our Study

Summarizing, English exhibits evidence supporting the hypothesis that the unpronounced EA of short passives is syntactically projected. This evidence includes the EA’s ability to control the PRO subject in depictive secondary predicates (9–12) and adjunct clauses (13–15), its association with agent-oriented adverbs (21a/22a), and its capacity to bind reflexive pronouns (25) (e.g.,

Baker et al. 1989;

Roberts 1987;

Collins 2005,

2024;

Grillo 2008;

Angelopoulos et al. 2023). By contrast, in Mandarin, the implicit EA of short passives appears unable to control into manner adjuncts (16–17) or to associate with certain agent-oriented adverbs, such as

duzi “alone” (24), suggesting the lack of a syntactic representation. However, evidence from purpose clauses (18), other agent-oriented adverbs (20, 22), and binding (26) leads to the opposite conclusions (despite some alternative explanations). Taken together, the syntactic diagnostics of a syntactically projected implicit EA in Mandarin short passives are inconclusive.

It has been independently proposed that languages differ in whether they syntactically project an EA in short passives, as in English, or not, as in Greek (see

Angelopoulos et al. 2023). In order to determine whether Mandarin syntactically projects an EA, we present acquisition data examining whether children’s short

bei-passives induce intervention effects. In the following sections, we present two studies—a corpus study, in which we compare Mandarin-speaking children’s productions of short and long passives to those of adults, and a comprehension study testing children’s comprehension of short and long passives. If Mandarin, short passives indeed lack an EA projection, we would expect Mandarin-speaking children to perform worse with long passives than short passives, as the latter would lack any intervening argument (overt or covert) to bypass.

3. Corpus Study

We analyzed data from Mandarin corpora on CHILDES (

MacWhinney 2000) containing the spontaneous productions of 1,182 monolingual Mandarin-speaking children aged 2 to 6, as well as their language input (Child-Directed Speech, CDS) during the recorded sessions.

7 We used CLAN (

MacWhinney 2000) to extract all utterances that contained the passive marker

bei. For each grammatical

bei-passive utterance, we coded whether the structure is a long passive or short passive, using the presence of an overt EA phrase after

bei as the criterion. For the long passives, we annotated the NP types of the two arguments (full NP, pronoun, proper name, or

wh-phrases) and the animacy level of each full NP.

After excluding 19 incomplete sentences, three indistinguishable utterances, and three immediate repetitions, there are a total of 395

bei-passive utterances in the child corpora. Among children’s production of

bei-passives, 39 were ungrammatical constructions and thus excluded.

8 In total, we found 356 grammatical

bei-passives produced by 2- to 6-year-olds, making up 0.166% of their total utterances. In the CDS, there were 1005

bei-passives, 0.295% of the total utterances recorded in our data. Overall, passives are infrequent in both child and child-directed Mandarin, consistent with the low frequencies of passives observed in previous studies on other languages (e.g., 0.36% in English CDS,

Gordon and Chafetz 1990). Therefore, any differences in performance cannot be solely attributed to the preponderance of passive constructions (short or long) in Mandarin.

Our corpus data indicate that Mandarin-speaking children, as young as 2 to 3 years old, already use a range of different verbs in both short (28a) and long (28b) passives, confirming

Hu’s (

2013) previous observation of early passive production in her longitudinal study.

| (28) | a. | ta | bei | zhe-yangzi | zhuan | zhuan | zhuan | zhuan | (2;08) |

| | | 3SG | BEI | this-way | spin | spin | spin | spin | |

| | | ‘He/She/It was spun and spin like this.’ | |

| | b. | Guaiguai | tongtong | bei | xiongxiong | chi-guang | | | (2;06) |

| | | Guaiguai | all | BEI | bear | eat-up | | | |

| | | ‘Guaiguai is all eaten up by the bear.’ |

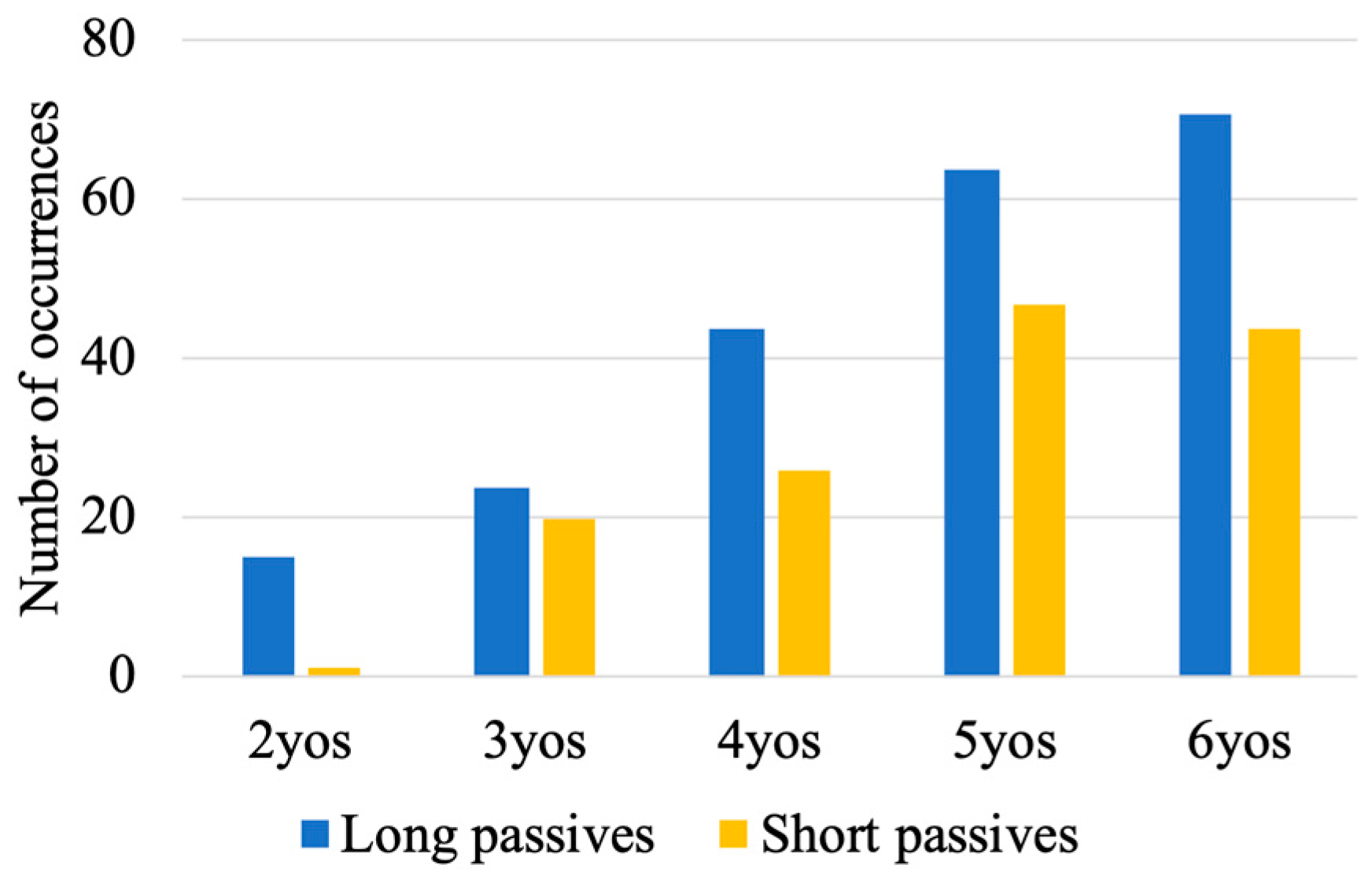

Among the 356 grammatical

bei-passives produced by 2- to 6-year-olds, long passives (61.24%) were significantly more frequent than short passives (38.76%) (

p < 0.001, binomial test), a trend observed throughout childhood, as depicted in

Figure 1. This finding is surprising, differing notably from results in other languages where short passives are more prevalent in children’s spontaneous production (e.g.,

English:

Horgan 1978;

K’iche’:

Pye and Poz 1988;

Sesotho:

Kline and Demuth 2010). Interestingly, our results also show a similarly high frequency (58.5%) of long passives in the 2- to 6-year-olds’ input data (CDS), in contrast to

Gordon and Chafetz’s (

1990) English corpus study, which found that only 4% of passives in child-directed English are long passives. The high proportion of long passives in the child data is not significantly different from that in the CDS (

χ2(1) = 0.81,

p = 0.37).

On their face, these results seem to challenge our hypothesis that short passives in Mandarin lack an implicit agent. If they were truly short, then they should be easier than long passives, which are constrained by intervention. On the other hand, long passives are also more frequent in the adult input; hence, it is reasonable to assume that children produce long passives for whatever reason(s) adults do or because they are following their input in some sense.

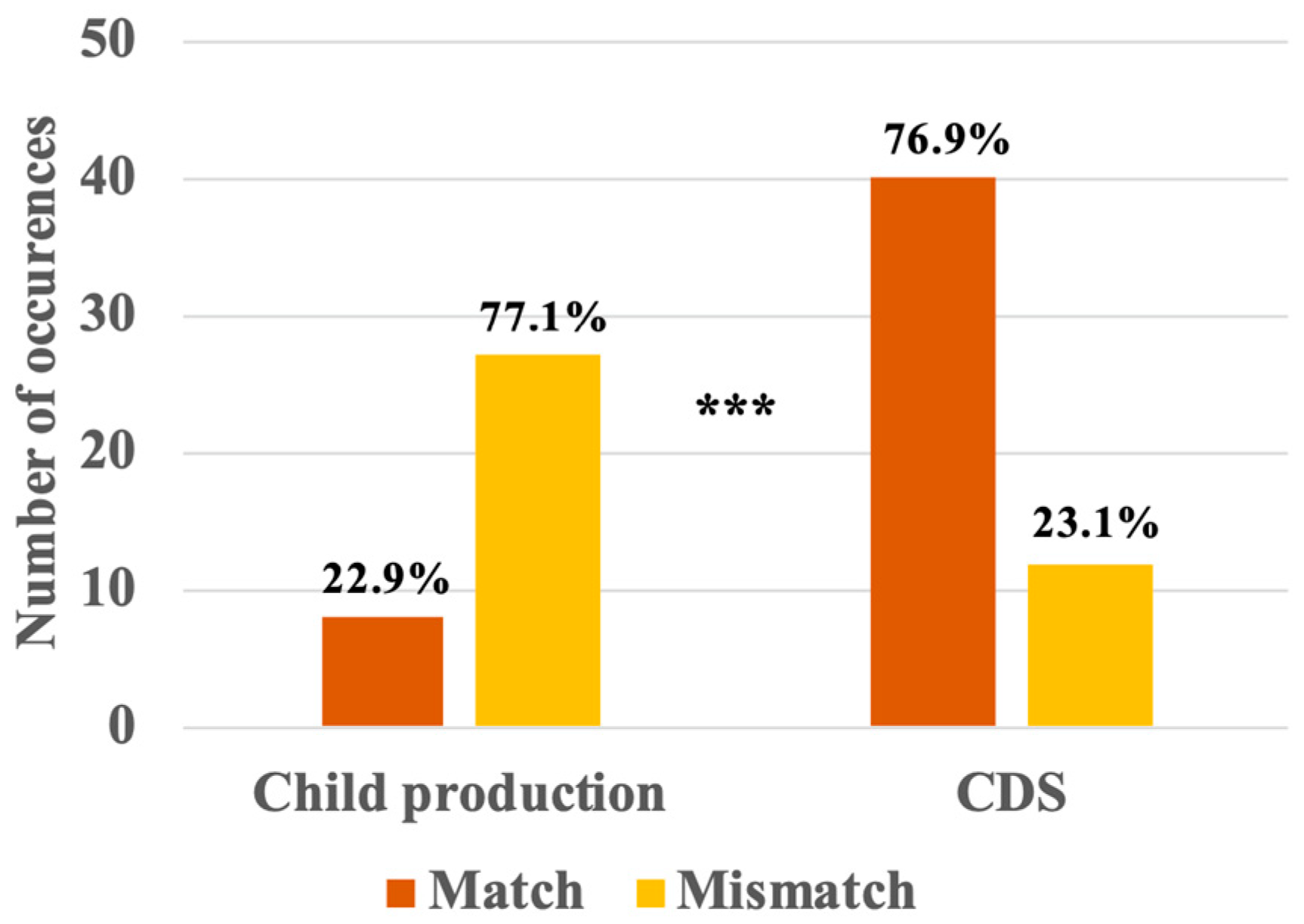

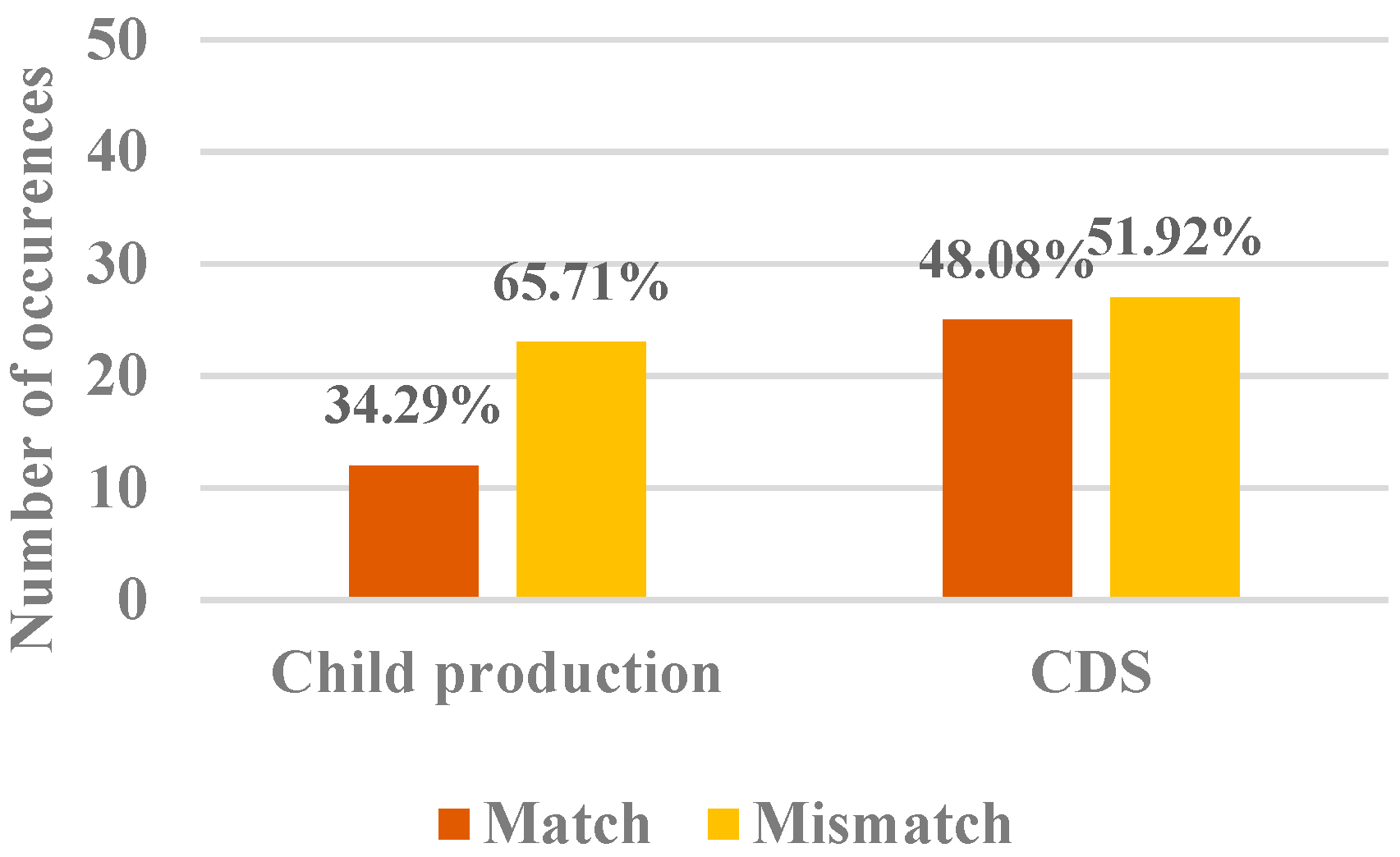

However, further examination of the data reveals an intriguing asymmetry between children’s productions and their input—while adults produce a significantly greater proportion of long passives with NPs that match in animacy features, children seem to avoid those. There were a total of 35 long passives in child speech and 52 in the CDS that had two NP arguments. As shown in

Figure 2, in the child data, 77.1% of the long passives contained animacy-mismatched NP arguments, while the adult data showed the opposite pattern—76.9% of the passives contained animacy-matched NP arguments (

χ2(1) = 24.7;

p < 0.001). If children are solely mirroring their input, we would predict more animacy-matched long passives in their production, contrary to the fact.

In order to ensure that the difference between children and adults stems from intervention and not a general preference for animate agents and inanimate patients, we ran a second corpus study with active transitive sentences. We extracted the same number of active sentences as we had for passive sentences in which both the subject and the object were full NPs. Across the two studies, we kept constant the number of sentences produced by 2-, 3-, 4-, 5-, 6-year-olds and adults and the number of sentences containing a particular verb. When the same verb that occurred in the passive sentences was not found in an active sentence with two NPs, we searched for a semantically similar one, e.g.,

tou “steal” instead of

qiang “rob”). As shown in

Figure 3, in the child data, 34.29% of the active transitive sentences contained animacy-matched NP arguments. The adult data showed a similar pattern—48.08% of the active transitive sentences contained animacy-matched NP arguments. The difference between the two groups was not significant, (

χ2(1) = 1.628;

p = 0.202).

These results are consistent with a featural intervention effect. Specifically, long passives with two NPs matched in animacy features would involve an “inclusive” configuration (see

Section 1.2), which would disrupt the movement of the internal argument to the subject position.

9 However, no such difficulty is found in active transitive sentences, hence the lack of a difference between children and adults in this case.

In contrast to long passives and actives, the animacy features of the implicit EA in short passives must be determined from context, which is not always possible in a corpus study. Thus, because the corpus data do not allow us to make claims regarding any purported intervention effects in Mandarin short passives, in the following section, we explore this question experimentally.

4. Experimental Study

In our experimental study, we use our intervention diagnostic to investigate whether there is an implicit agent in Mandarin short passives. Our intervention hypothesis predicts the following: if short passives—in contrast to long passives—do not structurally project an EA, we predict that children will find short passives easier to comprehend than long passives, even though the latter are significantly more common in their input and in their own production. On the other hand, if short passives do project an EA, then children should find short passives as difficult as long passives (as English-speaking children do).

Further, if the EA is in fact structurally projected, then we may expect animacy features to affect children’s performance in short passives as they do in long passives. More specifically, given that the implicit EA is animate (as depicted in the experimental pictures), sentences with animate patient subjects (i.e., matching features) should be more difficult than sentences with inanimate patient subjects (i.e., non-matching features).

Finally, if animacy mismatches facilitate children’s computation of intervening configurations, we expect children to do better when there is a mismatch in animacy features in long passives, but this effect is not expected in active sentences.

4.1. Participants

The final sample includes data from 78 monolingual Mandarin-speaking 3- to 6-year-olds. All participants were recruited from Changsha, Hunan Province, China, and surrounding areas, through local daycare centers and kindergartens. None of the participants had a history of language or cognitive impairment. Participant data are given in

Table 2. Nine additional children were tested but excluded due to their chance or below-chance performance on the control trials: three or more errors in the 12 active sentences (binomial test,

p = 0.05).

4.2. Procedure

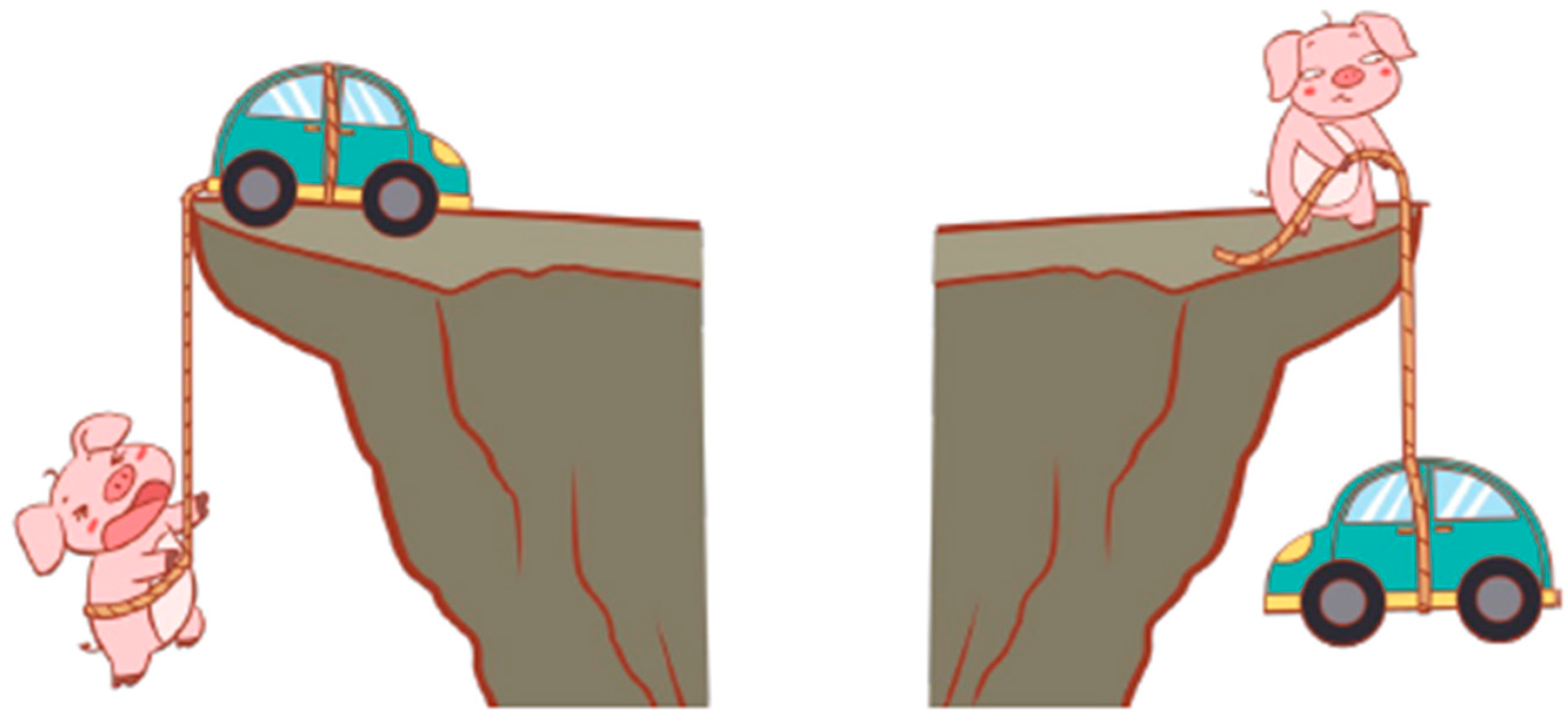

We employed a two-choice sentence-picture matching task with a 3 X 2 design, crossing three Sentence Types (actives, long passives, and short passives) and two Featural Conditions (Animacy match vs. mismatch). In total, there were 36 trials, six per condition. These trials varied among four verbs:

zhuang-dao “bump into”,

lan-zhu “block (the way of)”,

ya-dao “pin down”, and

la-zhu “pull”. We exclusively utilized animate EAs/Agents to ensure that the test scenarios were natural because previous studies indicate that an inanimate EA/Agent independently causes comprehension difficulty in children as it describes a “non-canonical event” (e.g.,

Slobin 1982;

Childers and Echols 2004). In short passives, there is only one NP—the internal argument (IA/surface subject). Nonetheless, the “Match” or “Mismatch” between the Agent and the Patient/Theme of the event was depicted in the test pictures in the same manner as the other two sentence types. The IA/surface subject was animate in half of the short passive trials and inanimate in the other half. The Agent of the event in the images was always animate. Experimental conditions are given in

Table 3, example sentences are provided in (29)–(31), and example images are shown in

Figure 4.

| (29) | a. | houzi | lazhu | le | xiao-mao | | (Active; Match) |

| | | monkey | pull | PERF | little-cat | | |

| | | ‘The monkey pulled the cat.’ | | |

| | b. | xiao-zhu | lazhu | le | gongjiaoche | | (Active; Mismatch) |

| | | little-pig | pull | PERF | bus | | |

| | | ‘The pig pulled the bus.’ | | |

| (30) | a. | xiao-niu | bei | daxiang | lazhu | le | (Long passive; Match) |

| | | little-cow | BEI | elephant | pull | PERF | |

| | | ‘The cow was pulled by the elephant.’ |

| | b. | xiao-qiche | bei | xiao-zhu | lazhu | le | (Long passive; Mismatch) |

| | | little-car | BEI | little-pig | pull | PERF | |

| | | ‘The car was pulled by the pig.’ |

| (31) | a. | huli | bei | | lazhu | le | (Short passive; [+ani]) |

| | | fox | BEI | | pull | PERF | |

| | | ‘The fox was pulled.’ |

| | b. | xiao-qiche | bei | | lazhu | le | (Short passive; [−ani]) |

| | | little-car | BEI | | pull | PERF | |

| | | ‘The car was pulled.’ |

Due to the COVID-19 pandemic, the experiment was conducted online via a video call, with the child and their caretaker/teacher on the one end and the experimenter on the other end. The experimenter shared her screen, displaying the materials in a PowerPoint slideshow. During the test, the children communicated their answers by pointing to the selected picture, and the adults accompanying them verbally reported which side of the screen was indicated.

4.3. Results

To determine whether the participants’ performance was significantly different from the chance level (50% correct), we first ran a single sample t-test on the mean rates of correct responses across all participants. Children’s performance with both long passives (t(77) = 11.20; p < 0.001) and short passives (t(77) = 33.21; p < 0.001) were significantly above chance.

We then used a mixed-effects logistic regression model in

R (

R Core Team 2021) to analyze whether children’s performance on short and long passives were nevertheless significantly different from each other. In our model, Age (in months) was considered a continuous variable. The full model includes the Sentence Type (actives, long passives, and short passives), Featural Condition (match/mismatch for long passives and actives; not applicable to short passives), and Age (in months), as well as all their interactions. Additionally, the model includes random intercepts for participants and verbs, to allow for individual differences across children and tested verbs. The significance of each fixed and random effect was tested using step-wise model comparisons with the

anova() function in R.

The random effect of verb was significant (

χ2(1) = 62.904;

p < 0.001) due to the children’s significantly lower performance on the verb

ya-dao “pin down”, which was the only verb that obtained less than 90% accuracy in the active sentences. It is unclear why this verb posed special difficulties. It may be that the images for this event were not clear enough or that the verb was unknown to some children (see

M. Liu 2023). Because we are not interested in lexical-semantic effects, but rather on whether children can comprehend passive sentences given their understanding of the meaning of the verb in active sentences, we excluded this verb from our analysis. The results without this verb are given in

Table 4.

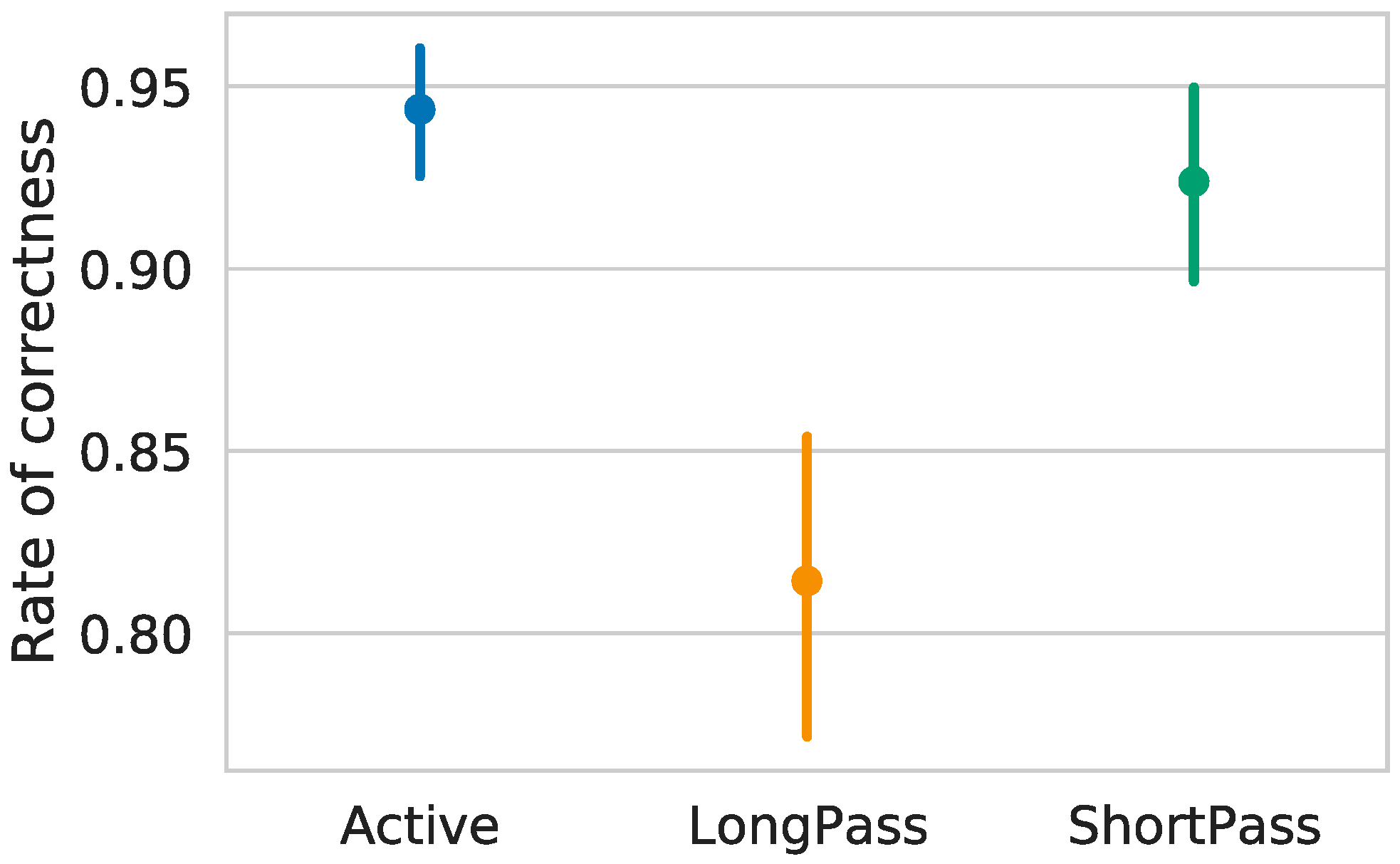

A step-wise model comparison showed that Age (in months) (

χ2(6) = 7.86;

p = 0.25) was not a significant predictor of children’s performance. There were significant effects of the Sentence Type (

χ2(8) = 78.11;

p < 0.001) and Featural Condition (

χ2(6) = 13.09;

p = 0.04). More specifically, as shown in

Figure 5, children performed worse with long passives than actives (

z-value = −6.73;

p < 0.001), while their performance with short passives and actives was not significantly different (

z-value = −0.69;

p = 0.49), consistent with our hypothesis that only long passives, but not short passives, include a syntactically projected EA that triggers intervention.

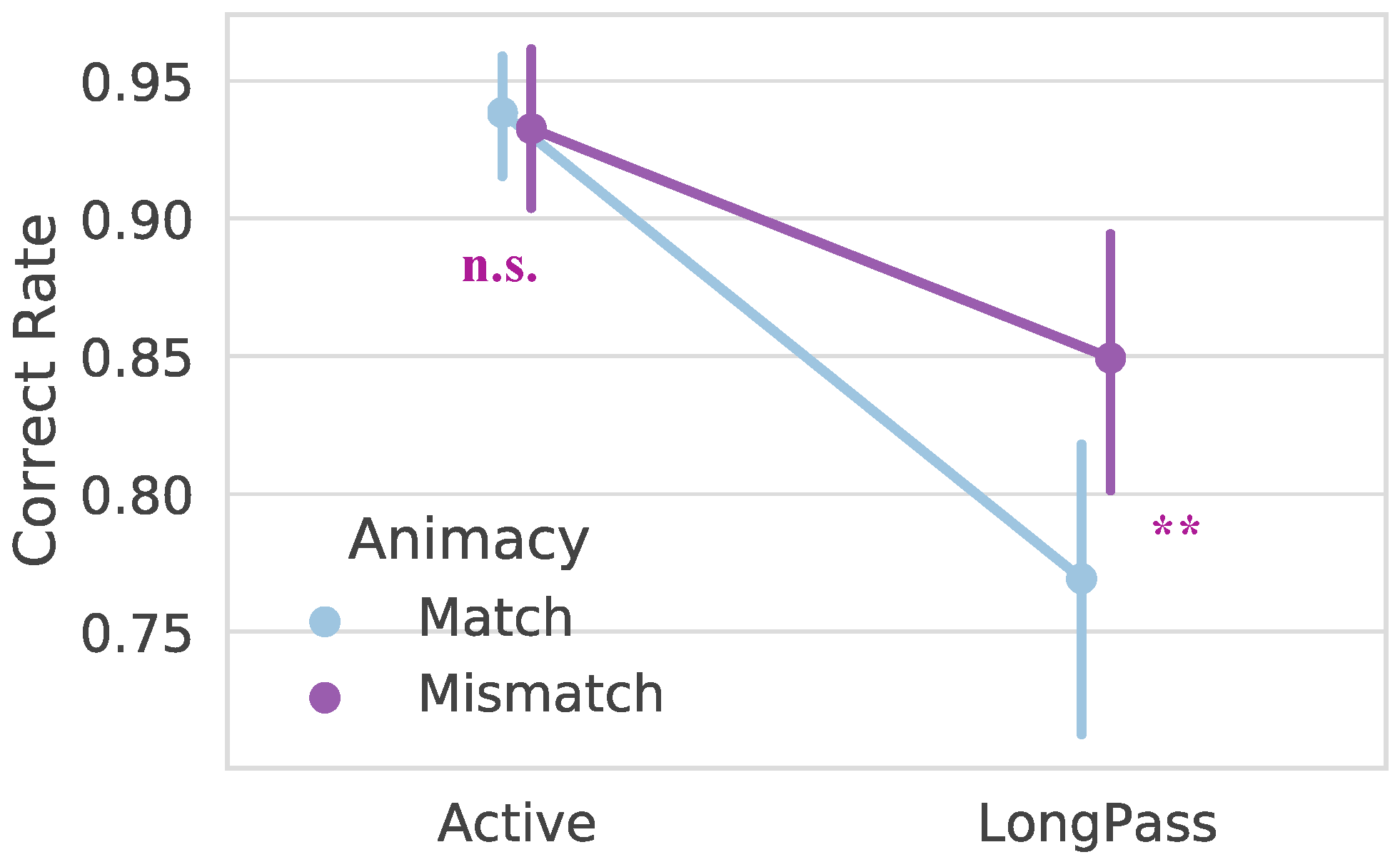

To examine the effect of featural manipulation between the IA and the EA, we focused on trials with sentences with two arguments (i.e., excluding short passives). The interaction between Sentence Type and Featural Condition was significant (

χ2(2) = 6.41;

p = 0.04). The difference between the animacy-matched vs. mismatched trials was only significant in long passives (

χ2(2) = 9.34;

p = 0.01)—with animacy-mismatched trials outperforming the matched ones (

z value = 2.31;

p = 0.02)—but not in actives (

χ2(2) = 0.26;

p = 0.88), as shown in

Figure 6. The manipulation of the animacy level of the only explicit argument in short passives had no significant effects on children’s performance (

χ2(2) = 2;06;

p = 0.36)—children did not find short passives with a [-animate] subject (and a [+animate] implicit agent) easier than those with a [+animate] subject (

z-value = −1.05;

p = 0.30), even for the three-year-olds. This suggests that their poorer performance in matched long passives is unlikely to be related to the low-probability of having an animate NP followed by

bei. These findings further support our hypothesis that short passives in Mandarin do not contain a structurally represented agent.

Summarizing, Mandarin-speaking children as young as 3 were able to comprehend short passives, as well as active sentences, but even the 6-year-olds tested in this study had difficulties comprehending long passives. Recall that Mandarin short passive constructions are not syntactically homophonous with adjectival constructions. Therefore, their improved performance cannot be attributed to an adjectival strategy in Mandarin. Moreover, manipulations of the animacy features of the explicit or implicit arguments (in pictures) only had an effect on their performance with long passives, but not with active sentences or short passives, consistent with featural intervention accounts and our hypothesis that Mandarin short passives (in contrast to English) do not contain a structurally projected implicit agent.

5. Discussion

The goal of our study was to examine whether Mandarin short passives project an implicit EA. While established syntactic diagnostics yield inconclusive results for Mandarin, we utilized intervention effects in children as a diagnostic tool to determine the syntactic representation of the silent external argument in Mandarin: whether it is syntactically projected as in English short passives (e.g.,

Baker et al. 1989;

Roberts 1987;

Collins 2005,

2017,

2024;

Grillo 2008;

Angelopoulos et al. 2023), or not, akin to what has been proposed for Greek (e.g.,

Angelopoulos et al. 2023). If the EA of short passives is syntactically represented in Mandarin, we hypothesized that children would exhibit difficulties with both short and long passives due to intervention, similar to what has been found in child English (

Fox and Grodzinsky 1998;

Hirsch and Wexler 2006;

Orfitelli 2012). Conversely, if the EA is not syntactically represented in Mandarin, we expected children to perform significantly better with short passives compared to long passives.

Our corpus study confirmed previous findings that Mandarin-speaking children produce both long and short bei-passives at a very early age. Interestingly, Mandarin-speaking children produce more long bei-passives than short ones, a phenomenon uncommon in other languages. In this respect Mandarin-speaking children seem to be mirroring their input. However, we observed that the vast majority of their long passives contained NPs mismatched for animacy, which we argued serves as a mechanism to circumvent NP intervention. Adults—who are subject to a less strict version of intervention—did not show this pattern, instead, they produced a relatively larger number of passives with animacy-matched NPs. Thus, the mismatch effect cannot be explained simply as an effect of input matching.

In our experimental study, we found that short

bei-passives were comprehended as accurately as their active counterparts. This indicates that neither the passive marker

bei nor the verbs or images used in the experiment were inherently difficult for the children. Considering the delayed acquisition of passives in many (but not all) languages, the good performance, even for the youngest group tested, on Mandarin short passives might be surprising, especially given that there is no adjectival strategy in Mandarin. However, under fRM (

Rizzi 1990,

2001,

2018), this is expected: in contrast to languages, such as English, in which the EA in short passives is phonologically null but present in the structure (e.g.,

Baker et al. 1989;

Roberts 1987;

Collins 2005,

2017,

2024;

Grillo 2008;

Angelopoulos et al. 2023), our results support the hypothesis that in Mandarin short passives, the EA is not syntactically projected.

It is worth considering whether the locality effects we observe in the acquisition of Mandarin long passives can be accounted for by a domain-general processing account, such as Similarity-based Interference (

Gordon et al. 2001,

2004;

Lewis et al. 2006;

McElree 2000;

Van Dyke and McElree 2006; a.o.), rather than the grammar-based approach we have adopted. The comparison with English short passives is instructive in this regard—in English but not Mandarin, short passives are as difficult as long passives. As far as we know, no domain-general processing account has claimed that unpronounced NPs that are syntactically (and not solely semantically) represented can also trigger interference. To account for our data, current models of sentence comprehension would need to incorporate more detailed formalizations of parsing mechanisms so that they can account for the different effects of unpronounced but syntactically represented NPs (e.g., the implicit EA in English short passives) compared to no syntactic representation at all (e.g., the lack of an EA projection in Mandarin short passives). A grammar-based model, like Relativized Minimality, which provides formal, theoretically-driven explanations for the different status of unpronounced NPs across languages, can inform contemporary psycholinguistic models of sentence comprehension.

A final point to consider is that the difference between English and Mandarin raises a learnability question—how does the child know if s/he is acquiring a language in which passives always contain an EA—either explicit or implicit—or a language in which only long passives contain a structurally represented EA, in other words, a language in which what you see is what you get. Considerations of positive/negative evidence (

Berwick 1985;

Manzini and Wexler 1987) require us to presume that children—all children—begin by assuming that there is no structurally projected EA in short passives. Mandarin-speaking children thus immediately converge on the adult grammar. On the other hand, we assume that English-acquiring children will require some kind of evidence that in their language, there is a structurally projected EA even in short passives. How they learn this, given the limited evidence we pointed out in

Section 2, is a puzzle for future research. But crucially, because we know that very young English-speaking children perform poorly with short passives in comprehension tasks (see

Section 1.1), we must assume that the structurally projected EA is triggered very early, hence that intervention effects show up in short and long passives alike (See

Table 1). Instances of short passives produced by young children prior to this point (e.g.,

Horgan 1978) are likely due to an adjectival strategy, as proposed by

Borer and Wexler (

1987) and

Hirsch and Wexler (

2006) and as demonstrated in experiments that have found that children interpret short passives as stative (adjectival) rather than eventive (verbal) (e.g.,

Gavarró and Parramon 2017;

Oliva and Wexler 2018;

Koring et al. 2024).