Abstract

Some languages make a distinction between formal and informal pronouns of address. When organizations communicate in such a language, they have to choose between the formal and informal form. The goal of this paper is to explore the role of the V-T distinction in organizational communication, specifically in generic job advertisements, through two empirical studies and to obtain a preliminary evidence-based framework for V and T in organizational communication. In a corpus study, we explore which form organizations from different industry types tend to use. We find that the choice of pronoun of address is associated with industry type in Netherlandic Dutch, German, French, and Spanish, but not in Belgian Dutch. In an experimental follow-up study, we explore the effect of pronouns of address on Dutch addressees in light of the perceived personality of the companies using these forms. We find an interaction between the pronoun of address used and the level of competence a company is associated with. Based on these studies and the existing literature, we propose a framework for V and T in organizational communication. In this framework, local linguaculture and industry culture play a role in the organizational choice between V and T. Furthermore, the way in which pronouns of address affect the addressee is determined by an interplay of company characteristics and addressee characteristics.

1. Introduction

In many European languages (e.g., Dutch, German, French, and Spanish), a speaker is required to choose between a formal (or V, from the Latin vos) and informal (or T, from the Latin tu) form when they want to address their interlocutor or reader (Brown and Gilman 1960). When communicating in such a language, multinational companies or organizations also have to choose between V and T in their communications. The sentences in (1) are examples of sentences used by one multinational company to address job seekers on its website in Dutch (a), German (b), French (c), and Spanish (d).

| (1) | a. | Begin je carrière bij Hunkemöller. |

| b. | Starte deine Karriere bei Hunkemöller. | |

| c. | Débutez votre carrière chez Hunkemöller. | |

| d. | Comienza tu carrera en Hunkemöller. | |

| ‘Start your career at Hunkemöller.’ |

In Dutch, German, and Spanish, Hunkemöller uses T-pronouns to address job seekers, while it uses V-pronouns to address job seekers in French. The choice of pronoun of address is an important one, because choosing an inappropriate pronoun of address can lead to negative feelings on behalf of the addressee and “embarrassment potential” for the speaker (Kretzenbacher et al. 2006). For individuals, factors which determine the choice of V or T include the speaker’s and addressee’s gender, age, and social circle (Levshina 2017). For companies, the choice of V or T is also likely to depend on multiple factors, although as of yet forms of address as used by organizations have not been extensively researched (we discuss certain exceptions below). Given the potential for negative feelings on behalf of the addressee that comes with choosing an inappropriate form of address, choosing the right pronoun of address is important for organizations.

To date, much work on pronouns of address has focused on the choice between V and T between individual speakers. However, few factors relevant to the choice between V and T for individuals can be easily applied to organizations. For example, in a study comparing the factors related to the choice of V or T in ten European languages, Levshina (2017) found that the (relative) social circle of the speaker and addressee matters in all languages investigated. However, the concept of a “social circle” is one that does not apply to organizations. Likewise, factors like gender and (relative) age cannot be straightforwardly applied to organizational communication.

Attempts have been made to capture how V and T are used in organizational communication. den Hartog et al. (2022) constructed a corpus of the pronouns of address used by 100 multinational companies on their recruitment websites in Netherlandic Dutch, Belgian Dutch, German, French, and Spanish, and quantitatively investigated the distribution of V vs. T as used in these different languages. The study was based on two previous studies of job recruitment ads in Netherlandic and Belgian Dutch (Vismans 2007; Waterlot 2014). Vismans (2007) found that V is more common than T in Belgian Dutch, while T is more common than V in Netherlandic Dutch. Waterlot (2014), by contrast, found an overall preference for T in both language varieties. den Hartog et al. (2022) found preferences for T in Netherlandic Dutch and Belgian Dutch as well, and in addition they found a preference for T in Spanish and a preference for V in French. There was no clear preference for either V or T in German. While den Hartog et al. (2022) demonstrated that the choice of V or T is language-dependent, they did not investigate the factors which make a particular company choose V or T in any given language with a V-T distinction. The study does suggest that such factors must exist, because in none of the languages was V or T used exclusively. Vismans (2007) did explore a factor potentially influencing the choice between V and T, namely, the industry in which a company operates. He found that industry type more strongly related to the pronoun of address used in Belgian Dutch than in Netherlandic Dutch. Whether this result holds for other languages with a V-T distinction has yet to be investigated.

The goal of this paper is to explore the role of the V-T distinction in organizational communication (more specifically, in generic job advertisements) through two empirical studies and to obtain a preliminary evidence-based framework for V and T in organizational communication. The two studies we report extend the work of den Hartog et al. (2022), Vismans (2007), and Waterlot (2014), demonstrating the importance of address pragmatics in job advertising in two distinct but related ways. First, we investigate whether the industry in which a company operates matters for the choice between V and T. Specifically, we ask:

- Does the choice of formal (V) or informal (T) pronouns of address vary in recruitment ads across different industries in Netherlandic Dutch, Belgian Dutch, German, French, and Spanish?

To answer this question, we report an analysis of the corpus first compiled by den Hartog et al. (2022) with an additional annotation for industry type. Our second research question is:

- 2.

- How does the response of Dutch speakers to formal (V) and informal (T) pronouns of address differ across company personalities?

We answer the second question with an experimental study in which we asked first speakers of Dutch to evaluate fictitious messages from existing companies directed at job seekers. The companies had different types of personalities in terms of competence and excitement (cf. Aaker 1997) and the messages used either V or T to address the job seekers.

Pronouns of address are part of organizational communication, and our two studies will provide insight into how they are employed in this domain. Understanding the impact of pronoun choice on the addressee may enable organizations to communicate more effectively, thus strengthening brand identity and communication with target audiences. Furthermore, understanding the factors relevant to the choice between V and T in organizational communication is of theoretical importance for better understanding pronouns of address, both in terms of their distribution in different communicational contexts and their impact on addressees.

The structure of this article is as follows. In Section 2, we review the current state of research into pronouns of address, specifically highlighting work relevant to organizational communication. The methods and results of our corpus study will be presented in Section 3, and our experimental study will be discussed in Section 4. Section 5 will provide a general discussion of both studies, followed by a general conclusion in Section 6.

2. Theoretical Background

Most work on address thus far has focused on address practices between individual speakers. Brown and Gilman (1960) were the first to create a framework to capture the motivations behind the choice between V and T. They suggested two dimensions which together determine whether V or T is appropriate in a given situation: power and solidarity. They defined power as the capacity “to control the behavior of the other” (Brown and Gilman 1960, p. 255) and solidarity as “the general relationship” (Brown and Gilman 1960, p. 258) between two people. Later work has emphasized that power and solidarity are not always sufficient to explain the choice between V and T. Based on a study of French, German, and Swedish, Clyne et al. (2009) suggested six “pragmatic principles” relevant to the interpersonal choice between V and T: familiarity (whether speaker and addressee know each other), maturity (whether the addressee is an adult), relative age (whether the addressee is younger or older than the speaker), network membership (whether the addressee is a member of the same social group), social identification (whether the addressee is similar to or different from the speaker), and address mode accommodation (whether the addressee uses V or T, and whether the speaker will choose to do the same; Clyne et al. 2009, p. 158).

The frameworks of Brown and Gilman (1960) and Clyne et al. (2009) cannot be straightforwardly applied to communication coming from an organization. It may be possible to ask whether an addressee is already known to an organization (familiarity) and whether the addressee is an adult (maturity), but the other pragmatic principles described by Clyne et al. (2009) are not as easily transformed to apply to organizational communication. Vismans (2013) qualitatively explored whether the principles of Clyne et al. can be applied to advertisement banners on websites of newspapers in Dutch (including Belgian Dutch). For this, Vismans changed the example questions linked by Clyne et al. to each principle so that they tap into the perspective of the target audience or addressee rather than the speaker. For example, he links social identification to the question of whether the addressee identifies with people shown in the advertisements or users of the advertised product. Vismans found that the principles of maturity and relative age could be related to the pronoun of address used in the banner advertisements, but social identification and network membership did not seem to influence the V-T choice. Thus, it seems that explaining the pronoun choices of organizations may require a different framework.

A number of previous studies have explored the use of pronouns of address in organizational communication and provided insight into the factors which play a role in the choice of V or T as used by an organization. In a Netherlandic Dutch corpus of job advertisements for highly educated job seekers, Vismans (2007) found that job advertisements from the construction industry used a higher proportion of V-forms (48.0%) than job advertisements from nine other industries (mean proportion of V-forms: 27.1%). Furthermore, four out of ten industries (finance and law, health care, research and education, and government) used V-forms more than 50% of the time in Belgian Dutch, while the other six industries used V-forms less than 50% of the time. These findings show that the choice between V and T may be influenced by industry culture. Relatedly, Norrby and Hajek (2011) investigated the impact of language policies promoting informal language applied by the furniture retailer IKEA and the clothing retailer H&M. Both companies promote the use of T-forms across languages with a V-T distinction, regardless of local linguacultural practices. In the case of IKEA, Norrby and Hajek found this to be a deliberate choice to create a youthful brand identity (but see House and Kádár 2020). Similarly to how speaker characteristics in relation to the addressee(e.g., relative age and network membership) play a role in V-T choice, this study shows that organizational characteristics in relation to the target audience (e.g., brand personality) play a role in which form an organization chooses to use. Our first study builds on these initial findings in two ways. First, Vismans (2007) demonstrated the link between industry and pronoun of address in Dutch, but it is unclear whether this link holds for other languages. Second, Vismans investigated a corpus of job advertisements from Belgium and the Netherlands, which would likely have been written mostly by Belgian and Dutch companies. Multinational companies like the companies investigated by Norrby and Hajek (2011) are further removed from the local linguaculture. In multinational companies, the link between industry and pronoun choice may be different, or even absent. Therefore, the goal of our first study is to establish whether there is a link between industry type and pronouns of address used by multinational companies active in Belgium, the Netherlands, Germany, France, and Spain.

Another aspect of pronouns of address that is important in organizational communication is the effect that the choice of V or T has on the addressee. Even when companies make deliberate choices through language policies, as in the case of H&M and IKEA, such efforts may be futile if the chosen pronoun of address impacts the target audience in unpredictable ways (cf. House and Kádár 2020). A number of studies have shown that the organizational choice of pronoun of address can indeed impact audiences. Truan (2022) constructed a corpus of the responses to a Twitter post from Deutsche Bahn (the German national railway company) announcing that it would start using T-forms in German to address its customers online. She found that responses generally fell into two categories: pro-V responses arguing that T-forms are inappropriate in a relationship between a company and its customers, and pro-T responses arguing that T-forms are an appropriate choice in online communications, and on social media in particular. This study shows that the actions of Deutsche Bahn brought on a discussion, and that formal and informal pronouns of address have the potential to impact audiences to such an extent that they argue about a V-T choice online.

Other studies have investigated the impact of pronouns of address in more subtle ways. Kretzenbacher and Hensel-Börner (n.d.) show how the impact of V and T forms on customers can differ between service types. They investigated the effect of V and T pronouns in German sales encounters by eliciting appreciation ratings of a salesperson (a 27-year-old male). Participants watched a video of a simulated sales encounter and their appreciation of the encounter was probed in dimensions such as, friendliness, empathy, liveliness, and competence. The simulated sales encounters took place in a sports shoe store, a bank, or a car dealership, i.e., three different service types representing three different industries. The authors found significant differences based on various factors, including the service type. Crucially for the purposes of our paper, the authors did not find address pronoun-related differences in the sports shoe store scenario, but the salesperson was regarded as more competent in the bank and car dealership scenarios, and as more honest in the car dealership scenario, when he used V. Moreover, in the car dealership scenario, he was considered livelier when he used T. Kretzenbacher and Hensel-Börner relate their findings being limited to the bank and car dealership scenarios to the amount of money involved in potential transactions and to the young and casual image of sports shoe companies.

Moreover, several studies have investigated the impact that address pronouns may have in Dutch. van Zalk and Jansen (2004) tested the impact of V and T in Dutch in an advertisement for a hiking holiday in Ireland. Participants were asked to evaluate the text and its content through Likert scales. van Zalk and Jansen found a main effect of pronoun of address, with participants reporting greater interest in the content and more positive opinions about the subject when V was used. They found no effects of V vs. T on how participants evaluated the quality of the text. Another study that found positive effects of V-forms in Dutch is that of de Hoop et al. (2023). They found that when participants read emails from fictional companies either inviting them to a job interview or rejecting them for a position, the emails were evaluated more positively when written with V-forms.

Not all experimental studies investigating the impact of pronouns of address in Dutch find (implicit) preferences for V-forms. Schoenmakers et al. (2023) found a preference for T-forms in marketing slogans advertising various products (e.g., lipstick, a coffee machine, and health insurance) compared to slogans using V. Specifically, participants found advertisements using T more appealing than advertisements using V. Schoenmakers et al. did not find a difference between V and T as measured through evaluations of the product, purchase intention, or estimated price of the advertised product. Comparing the studies mentioned, the differences in materials used can potentially explain why some studies found a V-preference, while other studies found a T-preference. Schoenmakers et al. (2023) used visual advertisements with a short slogan, while van Zalk and Jansen (2004) used longer texts. de Hoop et al. (2023) used corporate communication as their stimulus material. Another potential explanation of the different outcomes of the studies mentioned above comes from Leung et al. (2022). They found that pronoun preference can interact with perceived company personality. Participants were asked to rate the warmth (i.e., warm, cordial, or friendly) and competence (i.e., competent, skilled, or capable) of 100 brands that are well known in the Netherlands using seven-point Likert scales. Participants were also asked to indicate on a seven-point scale whether they would prefer informal or formal communication from each brand. Leung et al. found a correlation between perceived warmth and preference for informal address, and between perceived competence and preference for formal address. When companies were not rated as particularly warm or competent, address preferences defaulted to T-forms.

Though some of the studies listed here found preferences for V-forms and others found preferences for T-forms in Dutch, most of them drew the same conclusion based on their results: participants will respond more positively to pronouns of address appropriate to the situation, company, or advertised product. de Hoop et al. (2023) argue that the preference for V in their experiment can be explained by the formal character of the corporate communication they investigated. Likewise, Schoenmakers et al. (2023) reason that they found a preference for T because T is the default form in advertisements in Dutch. This is in line with the preference for T found by Leung et al. (2022) for companies with a personality that is not particularly warm or competent. However, Leung et al. asked their participants to indicate an explicit preference for V or T, and implicit and explicit evaluations of constructs are not always exactly the same (Nosek 2005). Therefore, establishing the impact of V and T as used by companies with varying personalities requires further investigation. The goal of our second study is to establish whether a company personality affects the (implicit) impact that pronouns of address have on the addressee.

3. Study 1—The Relationship between Industry and Address Form

3.1. Materials and Methods

We used the corpus of pronouns of address used on the websites of 100 multinational companies compiled by den Hartog et al. (2022) as a basis for this study. The decision to include Dutch, German, French, and Spanish was made to include two languages in which V is used widely (German and French) and two languages in which T is more used more widely (Dutch and Spanish). Furthermore, the distinction between Belgian Dutch and Netherlandic Dutch was added to make a comparison with the studies of Vismans (2007) and Waterlot (2014) possible. We extended the original corpus to include 158 multinationals in total, using the same methods as described by den Hartog et al. (2022). We looked for texts addressing job seekers on the recruitment pages of each multinational. We stored these texts in the corpus and annotated them for pronoun of address. Additionally, we determined the type of industry for each company. The industry classification used by Vismans (2007) was not suitable for our purposes, because many multinationals in our corpus did not fit well into the industry classifications that were used in this study. Therefore, we used the industry type listed on the Wikipedia page of the company and the ‘About Us’ section on company websites. In case of conglomerates or multi-industry companies, we chose the industry type the company is best known for among consumers based on a Google search of the company name. For example, we listed Bosch as part of the Electronics industry rather than ICT or Automotive. Furthermore, we merged some industry types into overarching categories to avoid having industry types with too few companies to make a comparison with other industries. Therefore, Steel, Chemicals, and Cement companies were classified into the industry type Heavy Industry, and any company producing food was listed as part of the Food Industry. Table A1 in Appendix A shows which industries were included in the analysis, and which companies were included in each industry.

To analyze the relationship between industries and pronouns of address, we performed a chi-square test for each language (i.e., Netherlandic Dutch, Belgian Dutch, German, French, and Spanish). To avoid problems with low expected values, we only used industry types represented by at least ten companies in our corpus. There were five possible categories of address pronoun: V, when the texts contained a formal pronoun of address and/or verb form; T, when the text contained an informal pronoun of address and/or verb form; EN, when the recruitment page was only available in English; M, for mixed use of V and T forms (e.g., in Dutch: Voeg Energie toe aan jouw carrière. We kijken uit naar uw sollicitatie! ‘Add Energy to your (T) career. We are looking forward to your (V) application!’); and NA, when the text contained no pronouns of address at all. As in the study of den Hartog et al. (2022), we considered only cases where the pronoun of address was V or T (the majority of cases) in our analysis. In case of a significant association between industry and pronouns of address, standardized residuals were used post hoc to assess which industry or industries contributed most to the chi-squared value. When the value of a standardized residual exceeded the critical z-value of 2.99 (Bonferroni-corrected), we considered an industry as contributing significantly to the chi-squared value.

3.2. Results

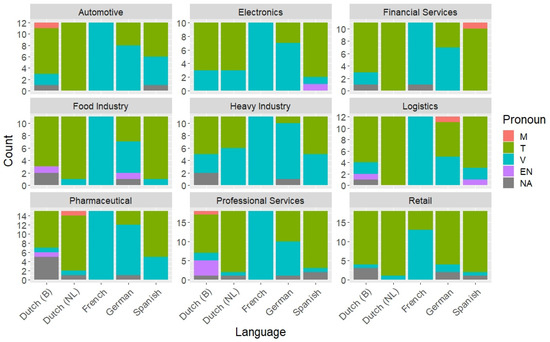

The distribution of address forms used in different industries in different languages is visualized in Figure 1. We found an association between Industry and Pronoun of Address in all languages in the corpus except for Belgian Dutch (χ2(8) = 6.03, p = 0.64). In Netherlandic Dutch, Heavy Industry contributed most to the association between Industry and Pronoun of Address (χ2(8) = 29.78, p < 0.001). The recruitment websites in this industry used more V-forms (50%) than other industries. In German, the Retail Industry influenced the link between Industry and Pronoun of Address (χ2(8) = 22.13, p = 0.004), with T being used more often in Retail than in other industries. The same was true for the association in French (χ2(8) = 28.73, p < 0.001), where Retail companies also used T more often on their recruitment page. Finally, different industries used different pronouns of address in Spanish too (χ2(8) = 19.08, p = 0.01), but no industry in particular contributed significantly to this association.

Figure 1.

A visualization of the distribution of address forms in different industries. A set of bar plots is given per industry, with a bar for each language. Colors represent pronoun of address type. Dutch (B) = Belgian Dutch; Dutch (NL) = Netherlandic Dutch.

3.3. Discussion

The goal of our first study was to establish whether the choice of V or T pronouns of address varies in recruitment ads across different industries in Netherlandic Dutch, Belgian Dutch, French, German, and Spanish. We found that different industries indeed use different pronouns of address in Netherlandic Dutch, French, German, and Spanish, but not in Belgian Dutch. In three of the languages (Netherlandic Dutch, Belgian Dutch, and Spanish), T occurs more frequently in recruitment ads than V (den Hartog et al. 2022). In Netherlandic Dutch and Spanish, we found that influence from industry culture can lead to a pronoun of address choice that differs from the norm, i.e., the use of V instead of T. In Netherlandic Dutch, V is more common in Heavy Industries than in other industries. This association aligns with Vismans’ (2007) observation that industries which can be characterized as conservative, like construction, favor V.

Conversely, Belgian Dutch showed no clear link between industry and pronoun use. As Figure 1 shows, in Belgian Dutch, almost every industry shows a pattern of majority T-use, with some companies opting for V instead. Industry culture thus seems to be decoupled from pronoun choice, but some companies make an individual choice of V. This finding can be explained in several ways. First, it is possible that regional or national preferences (Vandekerckhove 2005) play a larger role in the Belgian Dutch choice of V rather than T than industry preferences. Companies in different parts of Belgium might adhere to local customs or norms, leading to variations in pronoun choice even within the same industry. This may also mean that there is no industry norm to speak of, or that the industry norm is very weak. Second, some companies might consciously opt for V pronouns as a strategic or branding choice, even if it deviates from an industry norm. Further, note that the Belgian Dutch address pronoun system is fundamentally different from the Netherlandic Dutch system when it comes to their perception in that the standard Dutch T-forms je/jij ‘you’ are perceived as rather formal in Flanders, at least in the spoken modality; the endogenous T-pronoun ge ‘you’ is commonly used in informal speech instead (Vandekerckhove 2005; De Decker 2014, §4.2.4.1). While our corpus is composed of more formal texts in the written modality, we consider the possibility that the ambiguous and exogenous status of je/jij forms may thus have troubled the water somewhat in the Belgian Dutch data.

In German and French, languages in which V is more commonly used (den Hartog et al. 2022), we also find associations between pronoun of address and industry type. In German and French, this association is driven by the Retail Industry, which uses T more often even though V is the norm. The decision to use T in Retail recruitment ads may be linked to the type of personnel this industry seeks to attract. T is associated with younger addressees (Vismans 2013), and the deliberate choice of T has previously been associated with efforts to attract younger job seekers and to deter older job seekers in France (Hidri Neys 2021). Furthermore, our result is in line with the insight of Norrby and Hajek (2011) that Retail companies like H&M and IKEA (or sports shoe stores, as in Kretzenbacher and Hensel-Börner n.d.) may use T as a strategy to establish a youthful brand image. Notice, finally, the V-preference in the German automotive and financial service industries. This finding corroborates Kretzenbacher and Hensel-Börner’s (n.d.) observation that German customers view the salesperson in a car dealership or a bank in a more positive light when they use V. We do, however, find a considerable number of T forms in the job advertisements from these industries as well.

Our findings point towards a connection between industry and linguistic choices in recruitment ads. However, we cannot conclude on the basis of these findings how the choice between V and T affects the addressee of a message. Understanding the strategic use of pronouns to attract specific age groups, such as younger job seekers, holds particular relevance in the recruitment process. Therefore, our second study seeks to uncover how the choice of pronouns in recruitment texts, in conjunction with company personalities, influences the attitudes of Dutch-speaking individuals towards the recruitment text, the company, and the salary they expect—knowledge that can provide valuable insights into effective communication strategies and the impact of linguistic choices on the target audience.

We expect that different company personality types will interact with pronouns of address to affect addressees of organizational communication in different ways. Two aspects of brand image that we expect relate to address forms are excitement and competence (Aaker 1997). Companies seen as competent are likely to be associated with maturity and distance, which are characteristics associated with the use of V in individual speakers. In Aaker’s framework, conservativity, which we established to be associated with V use in Study 1, is part of the dimension of competence. Conversely, exciting companies are likely to be associated with youthfulness and familiarity, which are in turn associated with T (Brown and Gilman 1960; Clyne et al. 2009). Addressees will expect a form of address appropriate to the perceived brand personality of a given organization. We expect that if this expectation is violated, addressees will view a company less favorably than when the chosen pronoun is in line with the perceived brand personality.

4. Study 2—The Relationship between Company Personality and Address Form

4.1. Materials and Methods

4.1.1. Materials

To test the response to V and T pronouns of address as used by companies with different personalities, we conducted a questionnaire study. We chose to perform this experiment with Netherlandic speakers of Dutch to allow comparisons with previous studies on the effect of V and T in Netherlandic Dutch (e.g., van Zalk and Jansen 2004; Leung et al. 2022; de Hoop et al. 2023; Schoenmakers et al. 2023). We presented generic recruitment texts to our participants in which the name of a multinational company was randomly incorporated. Six generic recruitment texts were created with the assistance of ChatGPT-3.5 (OpenAI 2023). The prompt used was “schrijf een wervingsadvertentie voor een multinational” (in English: “write a recruitment advertisement for a multinational”). The resulting texts were manually adapted in case they were too long, too short, or there was too much overlap between the texts. All final texts were between 200 and 220 words long. Each text was adapted into a version using the formal ‘u’ you (V), informal je/jij ‘you’ (T), and a version without pronouns of address (C). A mix of the full variant jij ‘you’ and the reduced variant je ‘you’ was used in the T-condition. Examples of each version are given in Table 1. On average, there were 10 pronouns of address in the V and T versions of the texts (SD = 3.68).

Table 1.

Examples from the texts used in Study 2.

The multinational companies were chosen from the corpus used in our first study. To be able to test the relationship between company personality and address form, it was important that the participants were aware of the brand image of our chosen companies and that the companies had a pronounced competent or exciting brand image. Therefore, after an initial selection of 42 companies from the corpus was made, seven informants (three male and four female, aged 20–24, all university students) were asked in an informal procedure to indicate (1) whether they were familiar with the companies on the list, (2) whether they found the companies competent and/or exciting, and (3) which companies they would include that meet these criteria. Eleven companies were chosen based on the above criteria. A twelfth company was added to include at least one company (Dior) from the den Hartog et al. corpus in the experiment which uses V in Netherlandic Dutch in its recruitment advertisement (see Table 2 for an overview of the companies used in the experiment).

Table 2.

Companies in Study 2 ranked by Competence and Excitement, listed in order of most to least Competent (left panel) or Exciting (right panel).

4.1.2. Design and Procedure

Our experiment was conducted in Qualtrics (2020). After obtaining informed consent, the participants were asked demographic questions about their age, gender, education level, and first language. After that, each participant was asked to indicate which companies they were familiar with out of a list of six companies (out of the twelve companies included in the experiment). The participants rated the companies that they indicated being familiar with for Competence and Excitement. As such, each participant contributed to the company personality ratings we used as predictor variables in our models for at most half of the companies. The remaining six companies were then used as part of the experimental stimuli in conjunction with the generic recruitment texts.

In the experimental part of the study, the participants were randomly assigned to condition V, T, or C, following a between-subjects design. The participants were asked to read and assess six company-recruitment text combinations. For each company, the participants had to indicate whether they were familiar with the company. The participants then had to assess each company, recruitment text, and the salary they would expect to receive at the company by indicating their agreement with a total of eleven statements (see Section 4.1.4). Throughout the experiment, pronouns of address were avoided in any texts apart from the stimulus material. At the end of the experiment, the participants were thanked for their participation.

4.1.3. Participants

The participants were recruited via a combination of network sampling and the participant pool of Radboud University. A total of 322 participants filled out our questionnaire. To ensure that the participants were aware of a company’s brand image, we only included ratings in our analysis from the participants who indicated that they were familiar with all of the companies named in the text. Some of our participants did not know any of the companies, and some did not fully complete the questionnaire, meaning our analysis was ultimately based on data from 295 participants (64 male (21.7%)). Of these participants, 63 (21.36%) had completed secondary education, 5 (1.69%) had a vocational degree, 31 (10.51%) had completed at least one year of higher professional education, and 196 (66.44%) had completed at least one year of university education. The average age was 26.08 for the male participants (range: 18–68, SD = 13.83) and 21.22 for the female participants (range: 16–63, SD = 8.17).

4.1.4. Measures

Two types of measures were used in this study: company personality scales and scales assessing the participants’ attitudes towards the companies, recruitment texts, and expected salaries. The participants rated company personality through three items measuring Competence and three items measuring Excitement (both scales based on Aaker 1997). To measure Competence, the participants rated statements of the following form: Ik vind [bedrijf] prestigieus/conservatief/zakelijk. ‘I think [company] is prestigious/conservative/commercial.’ To measure Excitement, the participants were asked to agree or disagree with statements of the following form: Ik vind [bedrijf] dynamisch/jeugdig/energiek. ‘I think [company] is dynamic/youthful/energetic.’ We asked the participants to indicate their position on a scale from ‘fully disagree’ (helemaal mee oneens, coded as 1) to ‘fully agree’ (helemaal mee eens, coded as 7). The Cronbach’s alpha for the items measuring Competence was 0.73, and the Cronbach’s alpha for Excitement was 0.91, meaning both sets of items constituted scales with at least acceptable levels of reliability. Therefore, we averaged the items to obtain scores of company Competence and Excitement, respectively. An overview of the Competence and Excitement scores for each company is shown in Table 2.

In the experimental part of the study, the participants’ attitudes towards the company (six items), recruitment text (four items), and expected salary (one item) were assessed. The measure of expected salary is an analog of the price estimation measure used by Schoenmakers et al. (2023) and serves to give an insight into the perceived value of a product, service, or job presented to participants. An overview of all the items and the constructs they measure can be found in Table A2 in Appendix B.

4.1.5. Statistical Analysis

We constructed a linear mixed effects model for each outcome measure (Attitude towards the Company, Attitude towards the Text, and Salary Expectations) in R (R Core Team 2021) using the packages lme4 (Bates et al. 2015) and lmerTest (Kuznetsova et al. 2017). Each base model consisted of the following fixed effects: an interaction between Condition and Competence, an interaction between Condition and Excitement, and Item (only for Attitude towards the Company and Attitude towards the Text, because Salary Expectations were measured using only one item). The variable Condition was Helmert coded to compare the control condition without pronouns of address (C) to the average of the V and T conditions, and to compare T to V. The fixed effect Item always had a significant effect in the final models, but we do not report this fixed effect further because it is not relevant to our research question. In terms of random structure, each model contained a by-participant intercept. This was the maximal random structure achievable (following Barr et al. 2013).

After constructing a base model, other potentially relevant factors were added. One by one, we added Gender, Age, and Education (Secondary, Vocational, Higher Professional, or University Level) of the participants. After each addition, the new model was compared to the previous model using a likelihood ratio test (LRT) to assess whether adding or removing terms in the models significantly improved or worsened the model fit. This process led to the inclusion of Gender, Age, and Education in the models for Attitude towards the Company and Attitude towards the Text. In the model for Salary Expectations, only Age and Education were added as fixed effects.

4.2. Results

4.2.1. Attitude towards the Company

We found no interactions with and no main effect of Condition (C vs. VT or T vs. V) on Attitude towards the Company. We did find significant effects of Competence (β = 0.45, SE = 0.044, t = 10.25, p < 0.001), Excitement (β = 0.41, SE = 0.031, t = 13.51, p < 0.001), and Age (β = −0.016, SE = 0.0041, t = −3.93, p < 0.001) in our model for Attitude towards the Company. The more Competent or more Exciting a company was rated in our pretest, the more positive the attitudes of our participants towards the company were. Conversely, the higher a participant’s age, the more negative their attitude towards the companies. Full model specifications can be found in Appendix C, Table A3.

4.2.2. Attitude towards the Text

For Attitude towards the Text, we also found no interactions with or main effect of Condition (C vs. VT, or T vs. V). We did find significant effects of Competence (β = 0.26, SE = 0.0037, t = 6.82, p < 0.001), Excitement (β = 0.14, SE = 0.0026, t = 5.32, p < 0.001), Gender (Women vs. Men; β = 0.20, SE = 0.069, t = 2.92, p = 0.004), and Age (β = −0.014, SE = 0.0032, t = −4.32, p < 0.001). The more Competent or more Exciting a company was rated in our pretest, the more positive the attitudes of our participants towards the text were. Women (M = 4.70, SD = 0.85) were overall more positive about the texts than men (M = 4.43, SD = 0.87), and the higher a participant’s age, the more negative their attitude towards the texts. Full model specifications can be found in Appendix C, Table A4.

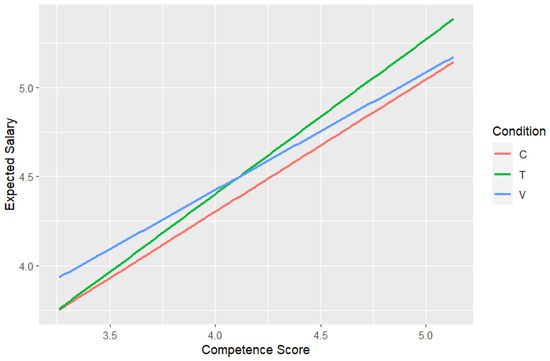

4.2.3. Salary Expectations

The results for Salary Expectations differ somewhat from those for Attitude towards the Company and Attitude Towards the Text. Here, we found an interaction of Condition (T vs. V) with Competence (β = 0.27, SE = 0.098, t = 2.79, p = 0.0054). In both the T and V condition, the Expected Salary increased with ratings of Competence. However, when Competence ratings were on the lower end of the scale, the participants expected a higher salary when V was used compared to T. Conversely, when Competence ratings were high, the participants expected a higher salary when T was used rather than V. This interaction effect is visualized in Figure 2.

Figure 2.

Plot of Expected Salary vs. Competence Score by Condition.

Other outcomes for Salary Expectations were significant main effects of Competence (β = 1.15, SE = 0.080, t = 14.34, p < 0.001), Excitement (β = 0.30, SE = 0.055, t = 5.47, p < 0.001), Age (β = −0.010, SE = 0.0045, t = −1.34, p = 0.020), and Education (Vocational vs. Secondary; β = −0.74, SE = 0.034, t = −2.21, p = 0.028). The more Competent or more Exciting a company was rated in our pretest, the higher the participant estimated the salary. The higher a participant’s age, the lower they estimated the salary. For Education, we found that those who completed a vocational degree estimated lower salaries than those who completed secondary school. Full model specifications can be found in Appendix C, Table A5.

4.3. Discussion

The research question we addressed in our second study was: How does the response of Dutch speakers to V and T pronouns of address differ across company personalities? Although we found no difference in attitudes towards companies and recruitment texts dependent on pronouns of address as used by companies with different personalities, we did find that Dutch speakers estimate differences in salaries dependent on which pronoun of address is used, and that this is linked to the personality of the company using the pronoun of address. Specifically, we found an interaction between the pronoun of address used (V or T) and the level of competence a company appears to have. While we did expect company personality to interact with pronoun of address, the results are not in line with our expectation that competent companies would receive a more positive response when using V in Dutch. Instead, Dutch speakers estimate a higher salary when highly competent companies use T. Below, we explore possible explanations of our findings.

When competence ratings were low, the participants expected a higher salary when V was used compared to T. Since our participants read recruitment texts, they were invited to imagine themselves applying for a job at the company they were reading about. Given that we used existing companies in our stimulus material, and that we only included responses from participants familiar with a given company, the participants will have had preexisting opinions of the companies. These preexisting opinions are reflected in our competence and excitement ratings. In the case of high-competence companies, the participants were already familiar with a company’s worth and potential salaries. Given that the participants may already have been convinced that high-competence companies represent higher salaries, the use of the pronoun T further boosted salary expectations. The effect of T in this case may reflect that T fosters feelings of familiarity and belonging (Clyne et al. 2009).

While competence ratings interacted with pronouns of address, excitement ratings did not. Again, preexisting opinions are likely to have played a major role in the participants’ perceptions of the companies in our experiment. It is possible that the participants’ impressions of brand excitement in particular overshadowed any effect of or interactions with pronouns of address. The amount of excitement generated by a company may be clearer in the mind of the general public than the extent to which a company is competent (e.g., because of targeted commercials that emphasize the exciting features of their products or services), which seems to be reflected in the wider range of scores used in our experiment to rate excitement (range: 2.86 to 5.75) compared to competence (range: 3.26 to 5.13).

Further, the style of T-forms we used may have played a role in the lack of positive effects we found for the T-condition more generally. As our example texts in Table 1 show, our stimuli used mostly full jij ‘you’ rather than reduced je ‘you’ forms. These forms have been shown to differ somewhat in their distribution in spoken Dutch (Plevoets et al. 2008), so they might also have had somewhat different effects on an addressee. Indeed, de Hoop et al. (n.d.) investigated differences between the T-forms je and jij ‘you’, and the V-form u ‘you’ in service advertisements by eliciting participants’ attitudes towards a service advertisement and the service itself, as well as their purchase intention. They found a general preference for je among those participants who reported being involved with the service (je > jij > u) and the reverse pattern among those who reported not being involved with it (u > jij > je). The reduced and full T-forms may thus have had distinct effects on the attitudes of the participants in our study as well, culminating in a neutralization of the expected T-preference (at least for the exciting companies) which has been reported in earlier studies (e.g., Schoenmakers et al. 2023; but see Kretzenbacher and Hensel-Börner n.d., who did not find positive effects of T-use by a salesperson from a young and casual company). Note that we did not measure the participants’ involvement with the current job market or the companies in our study. For future studies on the effect of V vs. T in Dutch, it is advisable to include such involvement measures and to test the effect of full and reduced T-forms separately to further disentangle any differential effect of these forms.

Regarding the difference between V and T, in contrast to the current study, other studies on Dutch (e.g., van Zalk and Jansen 2004; Leung et al. 2022; de Hoop et al. 2023; Schoenmakers et al. 2023) have found that the use of V and T influences judgements of advertised products, companies, or texts. As T is the most common choice in Dutch recruitment ads (den Hartog et al. 2022), it is somewhat surprising that T did not lead to overall more positive attitudes towards the company or the text in our experiment. However, as noted, an explanation for this could be that addressee involvement with the recruitment texts was relatively low. Involvement can be defined as “[a] person’s perceived relevance of the object based on inherent needs, values and interests” (Zaichkowsky 1985, p. 342). Schoenmakers et al. (2023) found that when involvement with an advertised product is low, participants show a lower purchase intention and less positive attitudes towards a product, and less positive attitudes towards an advertisement. In the current study, we did not consider whether the participants were currently actively looking for a job or not. Those not on the job market may not have felt involved with the recruitment adverts, and this may have prevented any effect of V and T. Furthermore, our use of existing companies will likely have predisposed participants’ attitudes towards the companies, thus further obscuring any potential effect of T and V.

Also, in contrast to the current study, other studies on the effect of V and T in various languages (e.g., van Zalk and Jansen 2004; Hidri Neys 2021) have established interactions between addressee characteristics and the effect of V and T. Our results do show main effects of age for judgments of acompany, text, and salary, which were all estimated lower as age increased. It should be noted that our participants were mostly younger university students, though, so it is possible that the group we tested was too homogenous to detect an interaction between age and pronoun of address.

5. General Discussion

Our two empirical studies provide insight into what forms of address organizations choose when addressing job seekers and what effect this organizational choice of pronoun of address has on addressees. While there are frameworks for explaining the choice between V and T for individual speakers, no such framework exists yet for V and T in organizational communication. Considering the results from our two studies and the results from the studies reviewed in Section 2, we present a first attempt at creating such a framework in Table 3.

Table 3.

Factors related to the use of pronouns of address in organizational communication, with example questions that serve to illustrate the factors underlying the organizational choice between V and T (cf. Clyne et al. 2009, p. 158).

Table 3 lists four factors which we found to be relevant to the organizational choice between and the effect of V and T in our studies. The first two factors, linguaculture and industry culture, relate strongly to the outcomes of den Hartog et al. (2022) and Study 1. den Hartog et al. established that the language and territory in which a company operates are perhaps the most important factors in determining which form of address will most likely be used. The factor linguaculture taps into broad cultural norms determining the conventions for V and T in the relevant communicative medium (e.g., written or spoken language, an advertisement, or a rejection letter). Furthermore, we found that the narrower cultural norms of industry conventions play an important role in determining the choice of V or T. The second two factors, addressee characteristics and company personality, relate to the impact of pronouns of address. Addressee characteristics such as age have been found to play a role in the choice and effect of V vs. T (e.g., van Zalk and Jansen 2004; Hidri Neys 2021). Therefore, establishing who the addressees of a message are is relevant to determining the appropriate pronoun of address. Finally, the interaction effect between company competence and pronoun of address that we found in Study 2 has shown that organization characteristics such as (desired) brand personality are relevant to the impact of pronouns of address.

The framework in Table 3 is structured in the same way as Clyne et al.’s (2009, p. 158) overview of pragmatic principles of address choice for individuals, but our framework contains the factors relevant to the organizational rather than the individual choice between V and T. The use of T and V by companies shows some parallels and some differences with the use of T and V by individuals. The biggest difference between the framework of Clyne et al. (2009) and the framework in Table 3 stems from the fact that most characteristics of individual addressees, like (relative) age and maturity, network membership, and social status, do not apply to organizations. However, organizations can have a personality, and Study 2 has shown that organizational personality is relevant to the effect of pronoun of address. Furthermore, address in organizational communication often concerns a single choice of pronoun of address rather than a discursive process of address negotiation. Therefore, the factors of local linguaculture and industry culture also have an influence on the choice of pronoun of address. Such factors are absent from the pragmatic principles of Clyne et al. (2009).

While the framework in Table 3 may provide some insight into the factors relevant to the choice between T and V, it also raises additional questions. For example, what happens when an organization’s personality is not clearly defined? Given that we focused on well-known companies in Study 2, established company personalities may have overridden any putative effect of V and T. It is possible that for companies whose personality is less clearly defined, the effect of V vs. T will be more pronounced. In combination with the results of Study 1, where we found that industries may differ in their conventions for the use of V and T, this means that not following industry conventions for V and T may have more impact for new or unknown brands than for established brands. Confirming this would require further research using fictional or unknown brands in addition to known ones. In the same vein, we may ask which form companies choose when their addressee is known (i.e., in other forms of organizational communication; see, e.g., de Hoop et al. 2023 for Dutch, Rosseel et al. 2024 for Belgian Dutch, and Kretzenbacher and Hensel-Börner n.d. for German) or when industry or local linguacultural norms are more or less clearly defined (see, e.g., Norrby and Hajek 2011; House and Kádár 2020). Finally, we stress that the empirical results on which we based our framework mostly concern organizational communication directed at job seekers in a selection of languages. Whether the framework holds for other types of organizational communication in other languages too remains to be verified.

6. Conclusions

Our studies have shown that V and T pronouns of address used by organizations in generic job advertisements must be considered in conjunction with the industry type and brand personality of the organization using the pronoun of address. The effect that a pronoun of address has can depend on the company personality. Based on our results, we proposed a framework in which factors motivating T/V choice in organizational communication are identified, viz. local linguaculture, industry culture, addressee characteristics, and organization characteristics. Practically, our studies show that companies should carefully consider their brand personality when choosing which pronoun of address to use to achieve their communicative goals.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, G.-J.S. and M.d.H.; methodology, G.-J.S. and M.d.H.; formal analysis, S.B. and M.d.H.; investigation, S.B.; writing—original draft preparation, S.B. and M.d.H.; writing—review and editing, G.-J.S.; visualization, S.B. and M.d.H.; supervision, G.-J.S.; project administration, M.d.H. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was supported by the Dutch Research Council (NWO), grant number 406.20.TW.011.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was approved by the Ethics Assessment Committee of the Faculty of Arts and the Faculty of Philosophy, Theology and Religious Studies (EACH) of Radboud University (file number 2021-3221).

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

All corpus and experimental data and analysis scripts are available via https://repository.ubn.ru.nl/.

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank Helen de Hoop and Lotte Hogeweg for their helpful comments on our manuscript.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Appendix A

Table A1.

Overview of the companies in each industry.

Table A1.

Overview of the companies in each industry.

| Industry | Companies | n |

|---|---|---|

| Professional Services | PwC, EY, Deloitte, Randstad, Adecco, Sodexo, Arcadis, Aon, KPMG, Alphabet, Manpower, RSM, ISS, PageGroup, Walters People, SThree, ADP, Robert Half | 18 |

| Retail | Action, Lidl, IKEA, H&M, Hunkemöller, JYSK, Inditex, Rituals, Snipes, Dior, Lush, Zeeman, Nike, Esprit, Decathlon, CASA, Aldi, JD Sports | 18 |

| Pharmaceutical | GSK, Merck, AstraZeneca, Pfizer, Roche, Novartis, Bayer, Sanofi, Alliance Healthcare, Johnson and Johnson, Bristol Myers Squibb, Novo Nordisk, Amgen, Eli Lilly, Abbott Laboratories | 15 |

| Automotive | Yamaha Motor, Volkswagen, Mercedes Benz, BMW, Renault, Volvo, Ford, Audi, Mazda, Nissan, LeasePlan, Tesla | 12 |

| Logistics | Postal Service, DHL, Gorillas, UPS, Uber Eats, FedEx, CEVA Logisitcs, Dachser, GLS, DSV, Kuehne+Nagel, DB Schenker | 12 |

| Financial Services | ING, BNP Paribas, Allianz, Santander, FCA Bank, Deutsche Bank, Zurich Insurance group, Rabobank, AXA, BDO, Baker Tilly | 11 |

| Food Industry | Nestle, Coca Cola, Danone, Red Bull, Heineken, Haribo, Bonduelle, Kellogg’s, Refresco, Pepsico, Intertek | 11 |

| Heavy Industry | BASF, ArcelorMittal, ThyssenKrupp, Saint Gobain, LyondellBasell, Schneider Electric, Air Products, DuPont, Dow, SABIC, Yara International | 11 |

| Electronics | Apple Inc., Siemens, Bosch, ABB, Canon, ZEISS, Medtronic, Samsung Group, DigiKey, Toshiba | 10 |

Appendix B

Table A2.

Overview of the items used in the experimental part of Study 2.

Table A2.

Overview of the items used in the experimental part of Study 2.

| Construct | Item in Dutch | English Translation |

|---|---|---|

| Attitude towards the Company * | Ik krijg een positief beeld van dit bedrijf. | I get a positive impression of this company. |

| Ik zie mijzelf werken bij dit bedrijf. | I can see myself working for this company. | |

| Als ik bij dit bedrijf zou gaan werken, verwacht ik dat ik in een prettige werkomgeving terechtkom. | If I would start working at this company, I expect that I would enter a positive environment. | |

| Als ik bij dit bedrijf zou gaan werken, verwacht ik dat ik in een leuk team kom te werken. | If I would start working at this company, I expect that I would join a pleasant team. | |

| Attitude towards the Text * | De wervingstekst straalt professionaliteit uit. | The recruitment text appears professional. |

| Ik voel een afstand tussen het bedrijf waarvan de wervingstekst afkomstig is en mijzelf door de manier van schrijven. 1 | I feel distance between myself and the company which published the recruitment text because of the way the text is written. 1 | |

| De wervingstekst is aantrekkelijk. | The recruitment text is attractive. | |

| De wervingstekst is overtuigend. | The recruitment text is convincing. | |

| Ik voel me serieus genomen door de auteur van de wervingstekst. | I feel taken seriously by the author of the recruitment text. | |

| De auteur van de tekst doet alsof hij mij goed kent. | The author of the recruitment text acts like he knows me well. | |

| Salary Expectations | Het salaris bij dit bedrijf is denk ik [laag (1) … hoog (7)]. | I think the salary at this company is [low (1) … high (7)]. |

* Participants indicated their agreement with the statements measuring Attitude towards the Company and Attitude towards the Text on a 7-point Likert scale ranging from ‘fully disagree’ (1; ‘helemaal mee oneens’) to ‘fully agree’ (7; ‘helemaal mee eens’). 1 This item was reverse coded.

Appendix C

Table A3.

Model specifications for Attitude towards the Company.

Table A3.

Model specifications for Attitude towards the Company.

| Fixed Effects | β | SE | t | p |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| (Intercept) | 1.70 | 0.38 | 4.36 | <0.001 1 |

| C vs. VT | −0.14 | 0.22 | −0.62 | 0.54 |

| T vs. V | −0.20 | 0.38 | −0.52 | 0.61 |

| Competence | 0.45 | 0.044 | 10.25 | <0.001 1 |

| Excitement | 0.41 | 0.031 | 13.51 | <0.001 1 |

| Gender (Women vs. Men) | 0.21 | 0.087 | 2.36 | 0.02 2 |

| Age | −0.016 | 0.0041 | −3.93 | <0.001 1 |

| Education (Vocational vs. Secondary) | −0.42 | 0.30 | −1.42 | 0.16 |

| Education (Higher Professional vs. Secondary) | −0.013 | 0.14 | −0.09 | 0.93 |

| Education (University vs. Secondary) | −0.15 | 0.087 | −1.77 | 0.08 |

| C vs. VT × Competence | −0.0083 | 0.031 | −0.26 | 0.79 |

| T vs. V × Competence | 0.017 | 0.054 | 0.32 | 0.75 |

| C vs. VT × Excitement | 0.026 | 0.022 | 1.18 | 0.24 |

| T vs. V × Excitement | 0.032 | 0.038 | 0.86 | 0.39 |

| Random Effects | Variance | SD | ||

| By-Participant Intercept | 0.30 | 0.54 | ||

| Residual | 0.35 | 1.16 |

1 p < 0.001, 2 p < 0.05. Marginal R2: 0.19, conditional R2: 0.34. Significant effects in bold.

Table A4.

Model specifications for Attitude towards the Text.

Table A4.

Model specifications for Attitude towards the Text.

| Fixed Effects | β | SE | t | p |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| (Intercept) | 3.74 | 0.29 | 13.02 | <0.001 1 |

| C vs. VT | −0.15 | 0.19 | −0.78 | 0.43 |

| T vs. V | −0.18 | 0.32 | −0.55 | 0.58 |

| Competence | 0.26 | 0.0037 | 6.82 | <0.001 1 |

| Excitement | 0.14 | 0.0026 | 5.32 | <0.001 1 |

| Gender (Women vs. Men) | 0.20 | 0.069 | 2.92 | 0.004 2 |

| Age | −0.014 | 0.0032 | −4.32 | <0.001 1 |

| Education (Vocational vs. Secondary) | −0.45 | 0.24 | −1.91 | 0.06 |

| Education (Higher Professional vs. Secondary) | −0.19 | 0.11 | −1.70 | 0.09 |

| Education (University vs. Secondary) | −0.11 | 0.069 | −1.56 | 0.12 |

| C vs. VT × Competence | −0.0042 | 0.026 | −0.16 | 0.88 |

| T vs. V × Competence | 0.031 | 0.046 | 0.67 | 0.50 |

| C vs. VT × Excitement | 0.030 | 0.018 | 1.63 | 0.10 |

| T vs. V × Excitement | 0.022 | 0.032 | 0.69 | 0.49 |

| Random Effects | Variance | SD | ||

| By-Participant Intercept | 0.18 | 0.42 | ||

| Residual | 1.45 | 1.20 |

1 p < 0.001, 2 p < 0.01. Marginal R2: 0.16, conditional R2: 0.25. Significant effects in bold.

Table A5.

Model specifications for Salary Expectations.

Table A5.

Model specifications for Salary Expectations.

| Fixed Effects | β | SE | t | p |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| (Intercept) | −1.25 | 0.57 | −2.18 | 0.0302 |

| C vs. VT | −0.42 | 0.40 | −1.06 | 0.29 |

| T vs. V | −1.72 | 0.69 | −2.51 | 0.012 |

| Competence | 1.15 | 0.080 | 14.34 | <0.001 1 |

| Excitement | 0.30 | 0.055 | 5.47 | <0.001 1 |

| Age | −0.010 | 0.0045 | −1.34 | 0.020 3 |

| Education (Vocational vs. Secondary) | −0.74 | 0.034 | −2.21 | 0.028 3 |

| Education (Higher Professional vs. Secondary) | −0.17 | 0.34 | −1.07 | 0.28 |

| Education (University vs. Secondary) | −0.15 | 0.34 | −1.55 | 0.12 |

| C vs. VT × Competence | 0.045 | 0.056 | 0.80 | 0.42 |

| T vs. V × Competence | 0.27 | 0.098 | 2.79 | 0.0054 2 |

| C vs. VT × Excitement | 0.042 | 0.039 | 1.08 | 0.28 |

| T vs. V × Excitement | 0.13 | 0.067 | 1.95 | 0.052 |

| Random Effects | Variance | SD | ||

| By-Participant Intercept | 0.25 | 0.50 | ||

| Residual | 1.11 | 1.05 |

1 p < 0.001, 2 p < 0.01, 3 p < 0.05. Marginal R2: 0.19, conditional R2: 0.34. Significant effects in bold.

References

- Aaker, Jennifer L. 1997. Dimensions of Brand Personality. Journal of Marketing Research 34: 347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barr, Dale J., Roger Levy, Christoph Scheepers, and Harry J. Tily. 2013. Random Effects Structure for Confirmatory Hypothesis Testing: Keep It Maximal. Journal of Memory and Language 68: 255–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bates, Douglas, Martin Mächler, Ben Bolker, and Steve Walker. 2015. Fitting Linear Mixed-Effects Models Using Lme4. Journal of Statistical Software 67: 1–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brown, Roger, and Albert Gilman. 1960. The Pronouns of Power and Solidarity. In Style in Language. Edited by Thomas A. Sebeok. Cambridge: MIT Press, pp. 253–76. [Google Scholar]

- Clyne, Michael, Catrin Norrby, and Jane Warren. 2009. Language and Human Relations: Styles of Address in Contemporary Language. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Decker, Benny. 2014. De Chattaal van Vlaamse Tieners: Een Taalgeografische Analyse van Vlaamse (Sub)Standaardiseringsprocessen Tegen de Achtergrond van de Internationale Chatcultuur. Ph.D. thesis, Universiteit Antwerpen, Antwerpen, Belgium. Available online: https://hdl.handle.net/10067/1173060151162165141 (accessed on 8 March 2024).

- de Hoop, Helen, Natalia Levshina, and Marianne Segers. 2023. The Effect of the Use of T or V Pronouns in Dutch HR Communication. Journal of Pragmatics 203: 96–109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Hoop, Helen, Natalia Levshina, Sebastian Sadowski, and Gert-Jan Schoenmakers. n.d. Generalizing or Personalizing: Effects of Three Types of Second Person Pronouns in Service Ads. in preparation.

- den Hartog, Maria, Marjolein van Hoften, and Gert-Jan Schoenmakers. 2022. Pronouns of Address in Recruitment Advertisements from Multinational Companies. Linguistics in the Netherlands 39: 42–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hidri Neys, Oumaya. 2021. Effet(s) d’annonce. La Construction à Distance d’une Discrimination à l’embauche Selon l’âge. Langage et Société 174: 115–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- House, Juliane, and Dániel Z. Kádár. 2020. T/V Pronouns in Global Communication Practices: The Case of IKEA Catalogues across Linguacultures. Journal of Pragmatics 161: 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kretzenbacher, Heinz L., and Susanne Hensel-Börner. n.d. Pronominal Address in German Sales Talk: Effects on the Perception of the Salesperson. Languages. Submitted.

- Kretzenbacher, Heinz L., Michael Clyne, and Doris Schüpbach. 2006. Pronominal Address in German: Rules, Anarchy and Embarrassment Potential. Australian Review of Applied Linguistics 29: 17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuznetsova, Alexandra, Per B. Brockhoff, and Rune H. B. Christensen. 2017. lmerTest Package: Tests in Linear Mixed Effects Models. Journal of Statistical Software 82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leung, Eugina, Anne-Sophie I. Lenoir, Stefano Puntoni, and Stijn M. J. Van Osselaer. 2022. Consumer Preference for Formal Address and Informal Address from Warm Brands and Competent Brands. Journal of Consumer Psychology 33: 546–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Levshina, Natalia. 2017. A Multivariate Study of T/V Forms in European Languages Based on a Parallel Corpus of Film Subtitles. Research in Language 15: 153–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Norrby, Catrin, and John Hajek. 2011. Language Policy in Practice: What Happens When Swedish IKEA and H&M Take ‘You’ On? In Uniformity and Diversity in Language Policy: Global Perspectives. Edited by Catrin Norrby and John Hajek. Bristol: Multilingual Matters, pp. 242–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nosek, Brian A. 2005. Moderators of the Relationship Between Implicit and Explicit Evaluation. Journal of Experimental Psychology: General 134: 565–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- OpenAI. 2023. ChatGPT. OpenAI. Available online: https://chat.openai.com/. (accessed on 8 March 2024).

- Plevoets, Koen, Dirk Speelman, and Dirk Geeraerts. 2008. The Distribution of T/V Pronouns in Netherlandic and Belgian Dutch. In Variational Pragmatics: A Focus on Regional Varieties in Pluricentric Languages. Edited by Klaus P. Schneider and Anne Barron. Amsterdam and Philadelphia: Benjamins. [Google Scholar]

- Qualtrics. 2020. Windows. Provo: Qualtrics. [Google Scholar]

- R Core Team. 2021. R: A Language and Environment for Statistical Computing. Vienna: R Foundation for Statistical Computing. Available online: https://www.R-project.org/. (accessed on 8 March 2024).

- Rosseel, Laura, Eline Zenner, Fabian Faviana, and Bavo Van Landghem. 2024. The (Lack of) Salience of T/V Pronouns in Professional Communication: Evidence from an Experimental Study for Belgian Dutch. Languages 9: 100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schoenmakers, Gert-Jan, Jihane Hachimi, and Helen De Hoop. 2023. Can You Make a Difference? The Use of (in)Formal Address Pronouns in Advertisement Slogans. Journal of International Consumer Marketing 36: 99–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Truan, Naomi. 2022. (When) Can I Say Du to You? The Metapragmatics of Forms of Address on German-Speaking Twitter. Journal of Pragmatics 191: 227–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van Zalk, Franceina, and Frank Jansen. 2004. ‘Ze Zeggen Nog Je Tegen Me’: Leeftijdgebonden Voorkeur Voor Aanspreekvormen in Een Persuasieve Webtekst. Tijdschrift Voor Taalbeheersing 26: 265–77. [Google Scholar]

- Vandekerckhove, Reinhild. 2005. Belgian Dutch versus Netherlandic Dutch: New Patterns of Divergence? On Pronouns of Address and Diminutives. Multilingua-Journal of Cross-Cultural and Interlanguage Communication 24: 379–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vismans, Roel. 2007. Aanspreekvormen in Nederlandse En Vlaamse Personeelsadvertenties Voor Hoogopgeleiden. Tijdschrift Voor Taalbeheersing 29: 289–313. [Google Scholar]

- Vismans, Roel. 2013. Aanspreekvormen in Nederlandstalige Banneradvertenties. Tijdschrift Voor Taalbeheersing 35: 254–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Waterlot, Muriel. 2014. Aanspreekvormen in Poolse, Nederlandse en Vlaamse onlinepersoneelsadvertenties voor hoogopgeleiden. Neerlandica Wratislaviensia 24: 115–32. [Google Scholar]

- Zaichkowsky, Judith Lynne. 1985. Measuring the Involvement Construct. Journal of Consumer Research 12: 341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).