Semantic Network Development in L2 Spanish and Its Impact on Processing Skills: A Multisession Eye-Tracking Study

Abstract

1. Introduction

1.1. L2 Anticipatory Processing

1.2. The Present Study

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Participants

2.2. Materials

2.2.1. Visual World Task

2.2.2. Vocabulary Training

- Thematic list condition—this training condition mimics the vocabulary presentation found in L2 textbooks. Traditionally, words are taught in thematic lists in each chapter (food, professions), with a progression in theme complexity. The 180 words selected were classified into themes, using as a guide the Spanish textbooks Mosaicos 2 and Mosaicos 3 (Olivella de Castells et al. 2013, 2015). When a word was not found in these textbooks, other print and online Spanish textbooks were used as a reference to classify each word (Tamariz 2000; Terrell et al. 2001; González-Aguilar and Rosso-O’Laughlin 2005; Potowski et al. 2012; Cubillos 2015; Mir and Bailey de las Heras 2015; Lumen Learning 2018–2019). Then, the themes were organized into an increasing complexity level, using the order from the textbooks Mosaicos 2 and Mosaicos 3 (Olivella de Castells et al. 2013, 2015). For example, words like lápiz ‘pencil’ and reloj ‘clock’ were under the theme ‘classroom items’ in the textbooks, and it is the first topic typically taught at beginner levels. So, they appeared at the beginning of the training. Meanwhile, words such as vidrio ‘glass’ and reciclaje ‘recycling’ belonged to the theme ‘environment’, and they are usually learned at intermediate-low levels. So, they appeared later in the training.

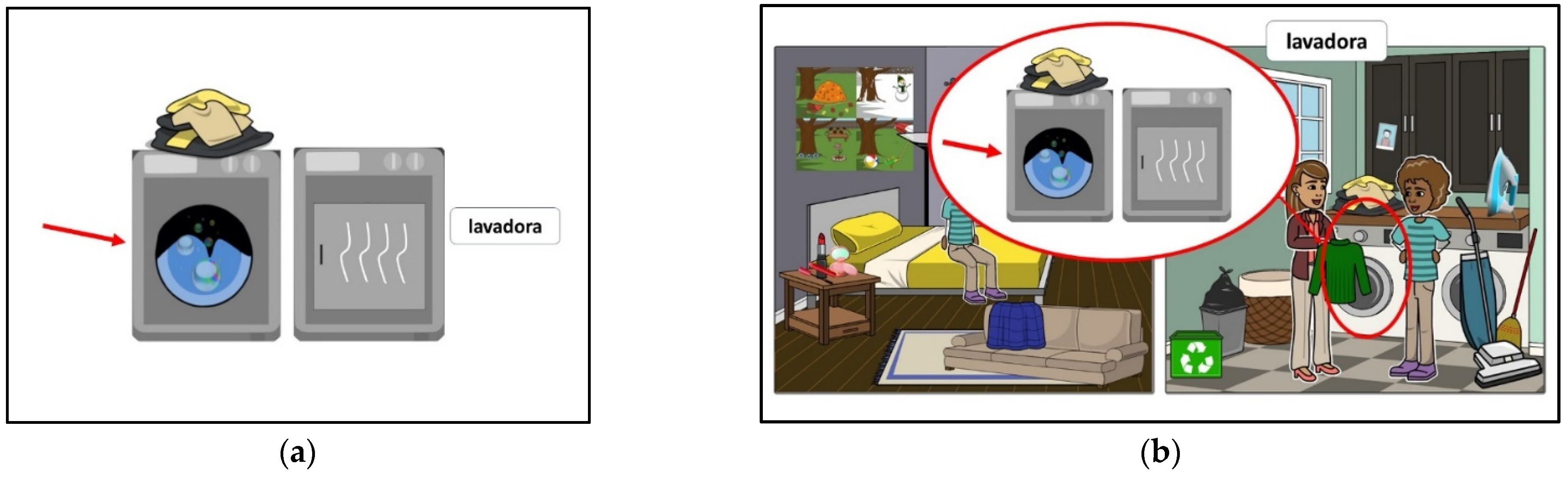

- Visual scene condition—for the visual scene training, six visual scenes were created using the platform Story Board That (Story Board That 2022). Each scene depicted at least two characters in each of these situations: shopping, dinner party, cleaning, sporting event, traveling, and hospital visit. Each scene included 30 vocabulary items for the participants to review, for a total of 180 words as in the list-by-theme training condition. Because of the density of items, each scene was divided into two panels, with 15 items in each one. This allowed for the objects to be spatially distributed, easier to distinguish, and also to show a progression of a story, similar to a comic strip (Figure 2).

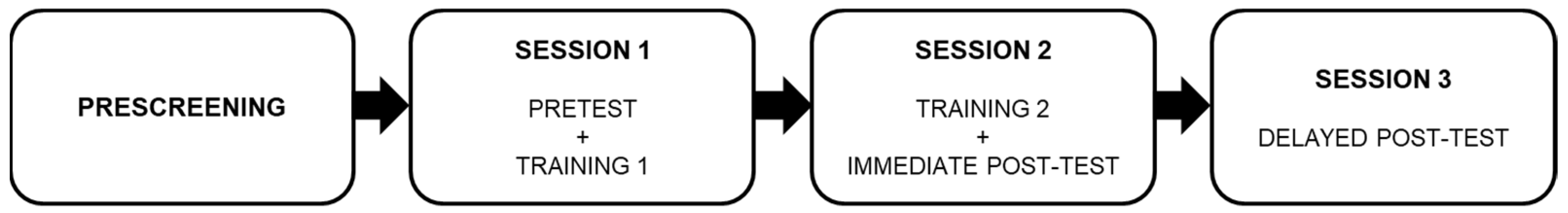

2.3. Procedure

2.3.1. Prescreening

- English category fluency;

- Spanish category fluency;

- Digit span;

- Language history questionnaire.

2.3.2. In-Lab Sessions

- Training—this task was completed on Experiment Builder (SR Research 2004–2015b) using an MH-5 Millikey button box and Sennheiser HD206 over-the-ear headphones. During this task, participants saw either individual pictures on the screen (TL condition) or visual scenes (VS condition) (Figure 4). In the TL condition, participants saw and heard the name of each object in Spanish (Figure 4a), and they were instructed to repeat it aloud and then press any button in the button box to continue to the next object. The images were organized into thematic lists, following the order found in the textbooks Mosaicos 2 and Mosaicos 3 (Olivella de Castells et al. 2013, 2015). In the VS condition, participants saw 6 visual scenes, one at a time, and they were instructed to press any button on the button box, so that one of the objects on the scene was highlighted with a red circle and enlarged in a bubble, as they heard and read the name of the object (in the example, lavadora ‘washer’ in the back of the scene is enlarged, Figure 4b). Participants were also instructed to repeat the name aloud before pressing any button on the button box to move on to the next objects. They repeated this procedure for each of the 6 scenes. In both training conditions, the audio recordings were the same used for the isolated words in the visual world task. In each case, participants were trained in 180 words (30 per scene in the VS condition).

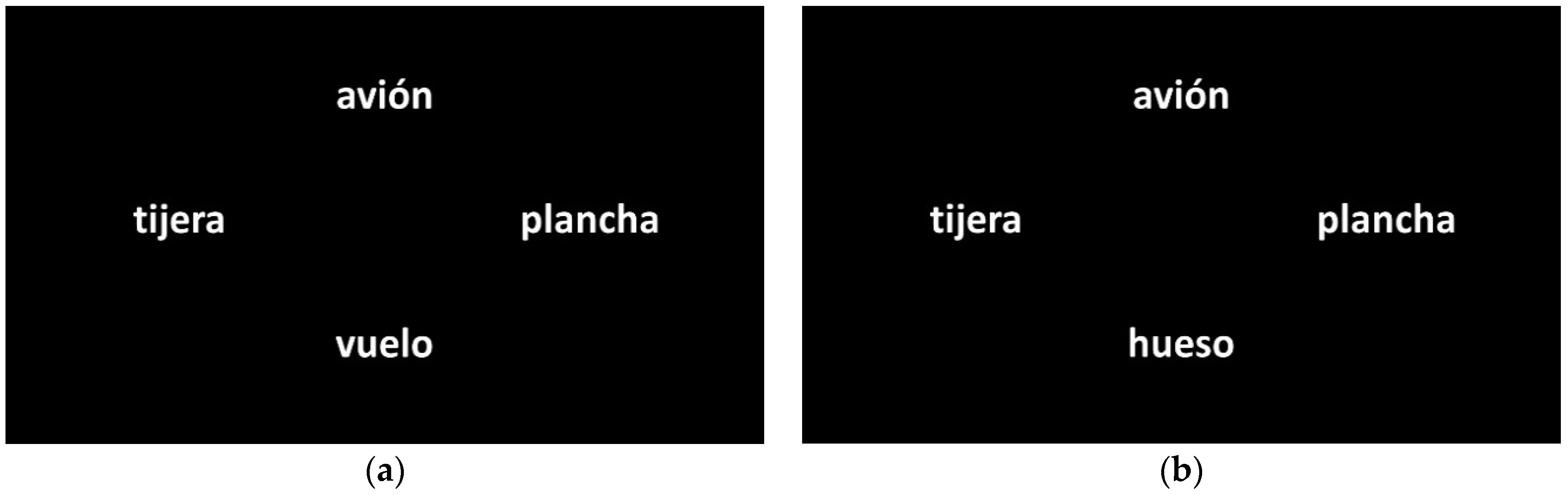

- Visual World–this task was presented on Experiment Builder (SR Research 2004–2015b) using a Dell mouse as an input device and Sennheiser over-the-ear headphones. The participants’ eye movements were recorded using an Eyelink 1000 Portable Duo Eye-Tracker (SR Research 2004–2015b), with a head mount. Participants’ right eyes were tracked at a sampling rate of 1000 samples per second. A 9-point calibration grid was used. The task was divided into 3 blocks of 24 trials each, and they were preceded by a short practice of 4 trials. The eye tracker was recalibrated between blocks if participants decided to take a break and shift their position. During each trial, participants were presented with 4 Spanish words on the screen, in a diamond-shaped array, using a 40-point Times New Roman white font on a black background. The diamond array was chosen rather than the more classic square array to avoid the corners of the screen, which are often the least precise points during calibration. The trials included a preview for participants to familiarize themselves with the words. During the preview, a green rectangle of 400 W × 350 H pixels appeared around each word, and the participants heard it pronounced with an onset delay of 250 ms. The order in which each word was highlighted and pronounced was always the same: top, left, right, bottom. After the preview, a fixation cross appeared on the screen for 500 ms. Then, the words reappeared in the same position, and the sentence was played through the headphones. Participants were instructed to click on the word mentioned in the sentence, and they were asked to wait until the sentence was done playing. The mouse cursor was a small red triangle on the screen, and it did not appear until the preview period was over (i.e., after the fixation cross, Figure 5). The accuracy of the mouse clicks was recorded, as well as eye movements throughout the entire trial.

2.4. Analysis

3. Results

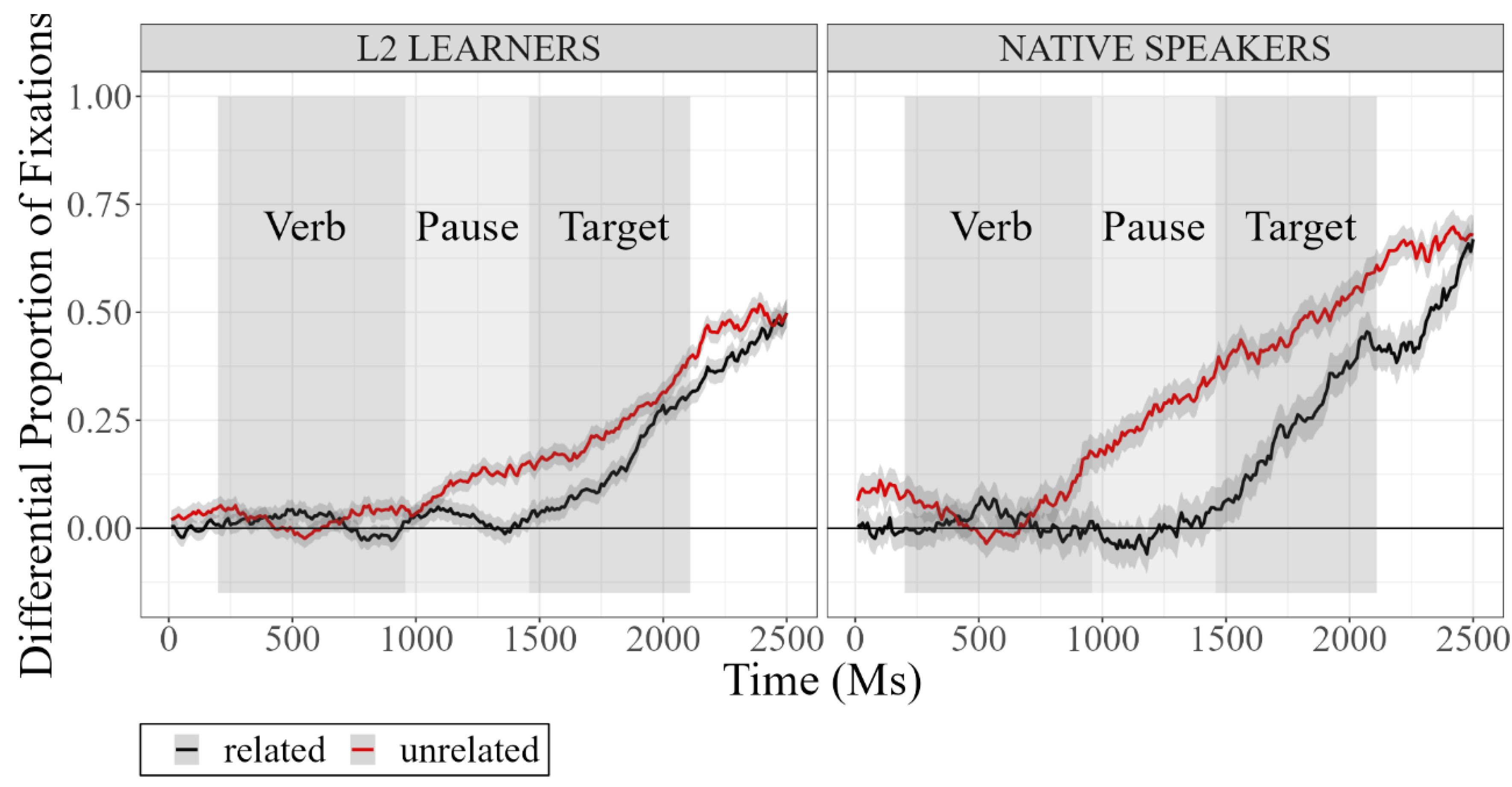

3.1. Comparing Native Speakers and L2 Learners during Pretest

3.2. Comparing L2 across Sessions

- (1)

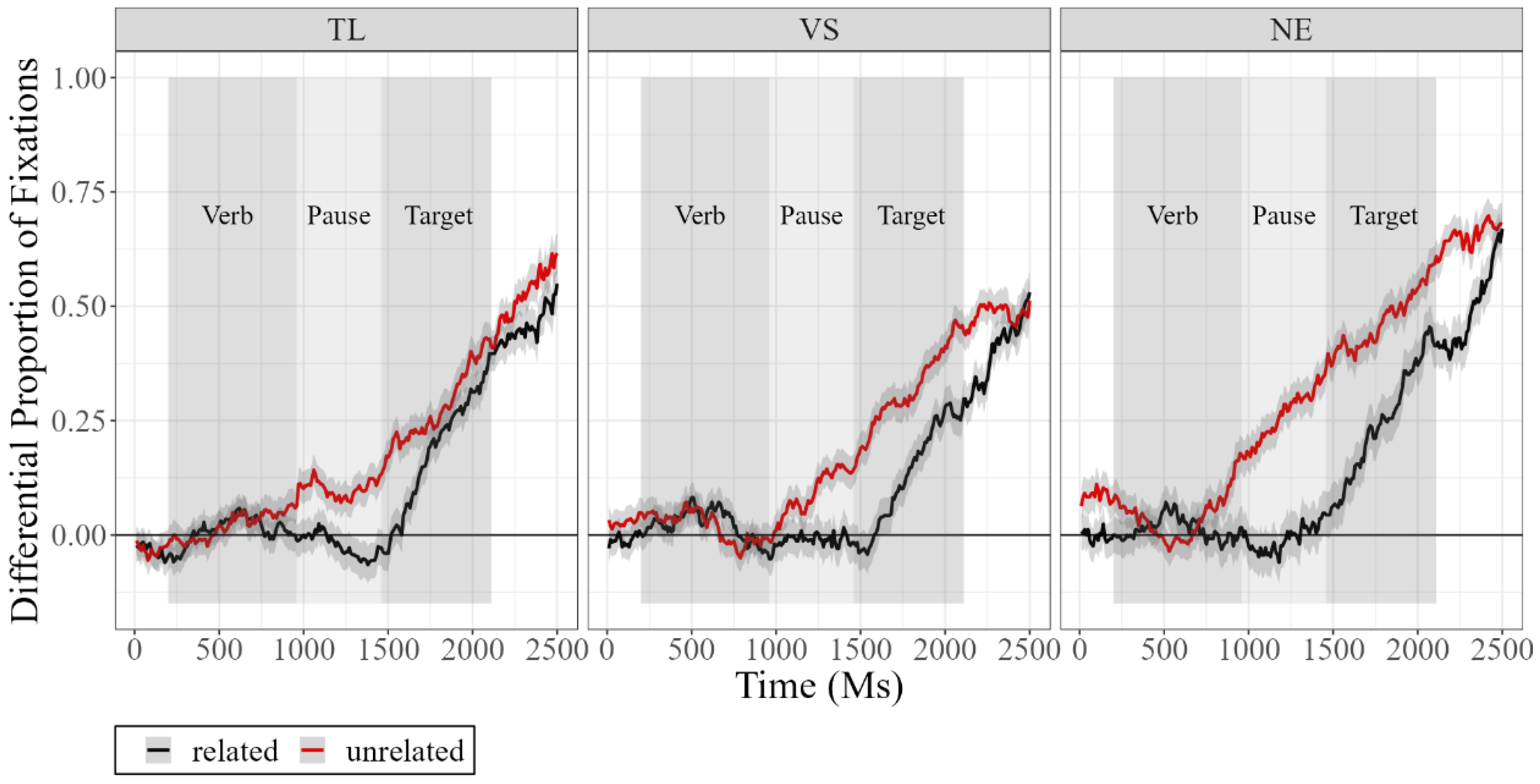

- Native speakers and L2 learners were significantly different at pretest, both in the pause and target regions. Both groups showed more looks to the target in the unrelated condition compared to the related condition, but the magnitude and timing of this effect were significantly different between the two groups;

- (2)

- The L2 learner groups (thematic list training and visual scene training) developed different behaviors after two rounds of training, with the VS group resembling the native speakers more than the TL group in Session 2 (immediate post-test). These differences across TL and VS, however, decreased by Session 3 (delayed post-test) because the VS group’s improvement diminished in the delayed post-test;

- (3)

- The differences between the two groups in Session 2 seem to be driven by the unrelated trials, rather than the related ones, contrary to what was targeted by the manipulations in the experimental design.

4. Discussion

Implications for L2 Instruction: Bringing Immersion to the Classroom

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Altmann, Gerry T. M., and Yuki Kamide. 1999. Incremental interpretation at verbs: Restricting the domain of subsequent reference. Cognition 73: 247–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barr, Dale J., Roger Levy, Christoph Scheepers, and Harry J. Tily. 2013. Random effects structure for confirmatory hypothesis testing: Keep it maximal. Journal of Memory and Language 68: 255–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bates, Douglas, Reinhold Kliegl, Shravan Vasishth, and Harald Baayen. 2015. Parsimonious mixed models. arXiv arXiv:1506.04967. [Google Scholar]

- Baus, Cristina, Albert Costa, and Manuel Carreiras. 2013. On the effects of second language immersion on first language production. Acta Psychologica 142: 402–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beatty-Martínez, Annie L., Paola E. Dussias, Rosa E. Guzzardo Tamargo, Christina A. Navarro-Torres, María Teresa Bajo, and Judith F. Kroll. 2020. Interactional context mediates the consequences of bilingualism for language and cognition. Journal of Experimental Psychology: Learning, Memory, and Cognition 46: 1022–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boersma, Paul, and David Weenink. 2017. Praat: Doing Phonetics by Computer [Computer Program]. Version 6.0.36. Available online: http://www.praat.org (accessed on 23 January 2024).

- Bolger, Patrick, and Gabriela Zapata. 2011. Semantic categories and context in L2 vocabulary learning. Language Learning 61: 614–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bordag, Denisa, Kira Gor, and Andreas Opitz. 2022. Ontogenesis Model of the L2 lexical representation. Bilingualism: Language and Cognition 25: 185–201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bousfield, W. A. 1953. The occurrence of clustering in the recall of randomly arranged associates. Journal of General Psychology 49: 229–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bybee, Joan. 1998. The emergent lexicon. Chicago Linguistic Society 34: 421–35. [Google Scholar]

- Cancho, Ramón Ferrer i, and Ricard V. Solé. 2001. The small world of human language. Proceedings of the Royal Society of London 268: 2261–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cofer, Charles N. 1966. Some evidence for coding processes derived from clustering in free recall. Journal of Verbal Learning and Verbal Behavior 5: 188–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cohen, Burton H. 1963. Recall of categorized word lists. Journal of Experimental Psychology 66: 227–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Collins, Allan M., and Elizabeth F. Loftus. 1975. A spreading-activation theory of semantic processing. Psychological Review 82: 407–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Connell, Katrina, M. Gabriela Puscama, Joana Pinzon-Coimbra, Julia Rembalsky, Gloria Xu, Jorge R. Valdés Kroff, María Teresa Bajo Molina, and Paola E. Dussias. 2021. Phonologically cued lexical anticipation in L2 English: A visual world eye-tracking study. In Proceedings of the 45th Annual Boston University Conference on Language Development. Boston: Cascadilla Press. [Google Scholar]

- Craik, Fergus I. M., and Endel Tulving. 1975. Depth of processing and the retention of words in episodic memory. Journal of Experimental Psychology: General 104: 268–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Craik, Fergus I. M., and Robert S. Lockhart. 1972. Levels of processing: A framework for memory research. Journal of Verbal Learning & Verbal Behavior 11: 671–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cubillos, Jorge H. 2015. Charlemos: Conversaciones Prácticas. Boston: Pearson. [Google Scholar]

- Davies, Mark. 2016–. Corpus del Español: Two Billion Words, 21 Countries. Available online: http://www.corpusdelespanol.org/web-dial (accessed on 4 August 2021).

- De Deyne, Simon, Daniel J. Navarro, Amy Perfors, Marc Brysbaert, and Gert Storms. 2019. The “small world of words” English word association norms for over 12,000 cue words. Behavior Research Methods 51: 987–1006. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- De Deyne, Simon, Daniel J. Navarro, and Gert Storms. 2013. Better explanations of lexical and semantic cognition using networks derived from continued rather than single-word associations. Behavior Research Methods 45: 480–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- De Deyne, Simon, and Gert Storms. 2008. Word associations: Network and semantic properties. Behavior Research Methods 40: 213–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- De Deyne, Simon, and Gert Storms. 2014. Word associations. In The Oxford Handbook of the Word. Edited by John R. Taylor. Oxford: Oxford University Press, pp. 465–80. [Google Scholar]

- DeLong, Katherine A., Thomas P. Urbach, and Marta Kutas. 2005. Probabilistic word pre-activation during language comprehension inferred from electrical brain activity. Nature Neuroscience 8: 1117–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dijkgraaf, Aster, Robert J. Hartsuiker, and Wouter Duyck. 2017. Predicting upcoming information in native-language and non-native-language auditory word recognition. Bilingualism: Language and Cognition 20: 917–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dijkgraaf, Aster, Robert J. Hartsuiker, and Wouter Duyck. 2019. Prediction and integration of semantics during L2 and L1 listening. Language, Cognition and Neuroscience 34: 881–900. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dubossarsky, Haim, Simon De Deyne, and Thomas T. Hills. 2017. Quantifying the structure of free association networks across the life span. Developmental Psychology 53: 1560–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duchon, Andrew, Manuel Perea, Nuria Sebastián-Gallés, Antonia Martí, and Manuel Carreiras. 2013. EsPal: One-stop shopping for Spanish word properties. Behavioral Research Methods 45: 1246–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dussias, Paola E., Jorge R. Valdés Kroff, Rosa E. Guzzardo Tamargo, and Chip Gerfen. 2013. When gender and looking go hand in hand: Grammatical gender processing in L2 Spanish. Studies in Second Language Acquisition 35: 353–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Finkbeiner, Matthew, and Janet Nicol. 2003. Semantic category effects in second language word learning. Applied Psycholinguistics 24: 369–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gilmore, Alex. 2007. Authentic materials and authenticity in foreign language learning. Language Teaching 40: 97–118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- González-Aguilar, María, and Marta Rosso-O’Laughlin. 2005. Atando Cabos: Curso Intermedio de Español, 2nd ed. Boston: Pearson. [Google Scholar]

- Grüter, Theres, Casey Lew-Williams, and Anne Fernald. 2012. Grammatical gender in L2: A production or a real-time processing problem? Second Language Research 28: 191–215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hallett, Peter E. 1986. Eye movements and human visual perception. Handbook of Perception and Human Performance 1: 10–11. [Google Scholar]

- Hart, Betty, and Todd R. Risley. 1992. American parenting of language-learning children: Persisting differences in family-child interactions observed in natural home environments. Developmental Psychology 28: 1096–105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hills, Thomas, Mounir Maouene, Josita Maouene, Adam Sheya, and Linda Smith. 2009. Longitudinal analysis of early semantic networks: Preferential attachment or preferential acquisition? Journal of the Association for Psychological Science 20: 729–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hopp, Holger. 2013. The development of L2 morphology. Second Language Research 29: 3–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hsiao, Indy Y. T., Yu-Ju Lan, Chia-Ling Kao, and Ping Li. 2017. Visualization analytics for second language vocabulary learning in virtual worlds. Educational Technology & Society 20: 161–75. [Google Scholar]

- Huettig, Falk. 2015. Four central questions about prediction in language processing. Brain Research 1626: 118–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Huettig, Falk, and Gerry T. M. Altmann. 2005. Word meaning and the control of eye fixation: Semantic competitor effects and the visual world paradigm. Cognition 96: B23–B32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Huettig, Falk, and Nivedita Mani. 2016. Is prediction necessary to understand language? Probably not. Language, Cognition, and Neuroscience 31: 19–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huttenlocher, Janellen, Heidi Waterfall, Marina Vasilyeva, Jack Vevea, and Larry V. Hedges. 2010. Sources of variability in children’s language growth. Cognitive Psychology 61: 343–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hwang, Jin Kyoung, Jeannette Mancilla-Martinez, Janna Brown McClain, Min Hyun Oh, and Israel Flores. 2020. Spanish-speaking English learners’ English language and literacy skills: The predictive role of conceptually-scored vocabulary. Applied Psycholinguistics 41: 1–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ito, Aine, Martin J. Pickering, and Martin Corley. 2018. Investigating the time-course of phonological prediction in native and non-native speakers of English: A visual world eye-tracking study. Journal of Memory and Language 98: 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jackson, Alice F., and Donald J. Bolger. 2014. Using a high-dimensional graph of semantic space to model relationships among words. Frontiers in Psychology 5: 385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiménez Jiménez, Antonio F. 2010. A comparative study on second language vocabulary development: Study abroad vs. classroom settings. Frontiers: The Interdisciplinary Journal of Study Abroad 19: 105–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaan, Edith. 2014. Predictive sentence processing in L2 and L1: What is different? Linguistic Approaches to Bilingualism 4: 257–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaan, Edith, Andrea Dallas, and Frank Wijnen. 2010. Syntactic predictions in second-language sentence processing. In Structure Preserved: Studies in Syntax for Jan Koster. Edited by C. Jan-Wouter Zwart and Mark de Vries. Amsterdam: John Benjamins, pp. 207–13. [Google Scholar]

- Kaan, Edith, and Theres Grüter. 2021. Prediction in second language processing and learning: Advances and directions. In Prediction in Second Language Processing and Learning. Edited by Edith Kaan and Theres Grüter. Amsterdam: John Benjamins, pp. 1–24. [Google Scholar]

- Koizumi, Rie, and Yo In’nami. 2013. Vocabulary knowledge and speaking proficiency among second language learners from novice to intermediate levels. Journal of Language Teaching and Research 4: 900–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuperberg, Gina R., and T. Florian Jaeger. 2016. What do we mean by prediction in language comprehension? Language, Cognition, and Neuroscience 31: 32–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kuznetsova, Alexandra, Per B. Brockhoff, and Rune H. B. Christensen. 2016. Tests in Linear Mixed Effects Models. Version 2.0.32. Available online: https://cran.r-project.org/web/packages/lmerTest/index.html (accessed on 15 April 2017).

- Lew-Williams, Casey, and Anne Fernald. 2007. Young children learning Spanish make rapid use of grammatical gender in spoken word recognition. Psychological Science 18: 193–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lew-Williams, Casey, and Anne Fernald. 2010. Real-time processing of gender-marked articles by native and non-native Spanish speakers. Journal of Memory and Language 63: 447–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Linck, Jared A., Judith F. Kroll, and Gretchen Sunderman. 2009. Losing access to the native language while immersed in a second language: Evidence for the role of inhibition in second-language learning. Psychological Science 20: 1507–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Llanes, Àngels, and Carmen Muñoz. 2009. A short stay abroad: Does it make a difference? System 37: 353–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- López-Beltrán Forcada, Priscila. 2021. Heritage Speakers’ Online Processing of the Spanish Subjunctive: A Comprehensive Usage-Based Study. Doctoral dissertation, Electronic Thesis and Dissertations for Graduate School, The Pennsylvania State University, State College, PA, USA. [Google Scholar]

- Lumen Learning. 2018–2019. Introductory Spanish II. Available online: https://courses.lumenlearning.com/wm-spanish2 (accessed on 15 April 2022).

- Luo, Lin, Gigi Luk, and Ellen Bialystok. 2010. Effect of language proficiency and executive control on verbal fluency performance in bilinguals. Cognition 114: 29–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malt, Barbara C. 2010. Naming artifacts: Patterns and processes. In The Psychology of Learning and Motivation: Advances in Research and Theory. Edited by Brian H. Ross. Amsterdam: Elsevier, pp. 1–38. [Google Scholar]

- Marian, Viorica, and Margarita Kaushanskaya. 2007. Cross-linguistic transfer and borrowing in bilinguals. Applied Psycholinguistics 28: 369–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meara, Paul. 1996. The dimensions of lexical competence. In Performance and Competence in Second Language Acquisition. Edited by Gillian Brown, Kirsten Malmakjaer and John Williams. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, pp. 33–55. [Google Scholar]

- Milton, James, and Paul Meara. 1995. How periods abroad affect vocabulary growth in a foreign language. ITL Review of Applied Linguistics 107: 17–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mir, Montserrat, and Ángela Bailey de las Heras. 2015. ¡Qué me Dices! A Task-Based Approach to Spanish Conversation. Boston: Pearson. [Google Scholar]

- Nagy, William E., and Patricia A. Herman. 1987. Breadth and depth of vocabulary knowledge: Implications for acquisition and instruction. In The Nature of Vocabulary Acquisition. Edited by Margaret G. McKeown and Mary E. Curtis. Mahwah: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates, Inc., pp. 19–35. [Google Scholar]

- Olivella de Castells, Matilde, Elizabeth E. Guzmán, P. Paloma Lapuerta, and Judith E. Liskin-Gasparro. 2013. Mosaicos: Course Materials for Spanish 2, 4th Custom ed. Boston: Pearson. [Google Scholar]

- Olivella de Castells, Matilde, Elizabeth E. Guzmán, P. Paloma Lapuerta, and Judith E. Liskin-Gasparro. 2015. Mosaicos: Course Materials for Spanish 3, 5th Custom ed. Boston: Pearson. [Google Scholar]

- Pizziconi, Barbara. 2017. Japanese vocabulary development in and beyond study abroad: The timing of the year abroad in a language degree curriculum. The Language Learning Journal 45: 133–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Potowski, Kim, S. Silvia Sobral, and Laila M. Dawson. 2012. Dicho y Hecho: Beginning Spanish, 9th ed. Hoboken: John Wiley & Sons. [Google Scholar]

- Prolific. 2014. Available online: https://www.prolific.co (accessed on 18 November 2021).

- Qian, David D. 2002. Investigating the relationship between vocabulary knowledge and academic reading performance: An assessment perspective. Language Learning 52: 513–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qualtrics. 2005. Provo, UT. Available online: https://www.qualtrics.com (accessed on 18 November 2021).

- R Core Team. 2013. R: A Language and Environment for Statistical Computing. Vienna: R Foundation for Statistical Computing. Available online: http://www.R-project.org (accessed on 15 November 2023).

- Recchia, Gabriel, and Michael N. Jones. 2009. More data trumps smarter algorithms: Comparing pointwise mutual information with latent semantic analysis. Behavior Research Methods 41: 647–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- SR Research Data Viewer 3.1.246 [Computer Software]. 2004–2015a. Mississauga: SR Research Ltd.

- SR Research Experiment Builder 2.2.38 [Computer Software]. 2004–2015b. Mississauga: SR Research Ltd.

- Stæhr, Lara S. 2009. Vocabulary knowledge and advanced listening comprehension in English as a foreign language. Studies in Second Language Acquisition 31: 577–607. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Story Board That. 2022. Available online: https://www.storyboardthat.com (accessed on 18 November 2021).

- Tamariz, Mónica. 2000. Oxford Spanish Cartoon-Strip Vocabulary Builder. Oxford: Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Terrell, Tracy, Magdalena Andrade, Jeanne Egasse, and Elías M. Muñoz. 2001. Dos Mundos, 5th ed. New York: McGraw-Hill. [Google Scholar]

- Voeten, Cesko C. 2020. buildmer: Stepwise Elimination and Term Reordering for Mixed-Effects Regression. Available online: https://cran.r-project.org/web/packages/buildmer/index.html (accessed on 1 April 2022).

- Zaytseva, Victoria, Carmen Pérez-Vidal, and Imma Miralpeix. 2018. Vocabulary acquisition during study abroad: A comprehensive review of the research. In The Routledge Handbook of Study Abroad Research and Practice. Edited by Cristina Sanz and Alfonso Morales-Front. New York: Routledge, pp. 210–24. [Google Scholar]

- Zhao, Xiaowei, and Ping Li. 2010. Bilingual lexical interactions in an unsupervised neural network model. International Journal of Bilingual Education and Bilingualism 13: 505–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zoom Video Communications. 2022. Available online: https://zoom.us (accessed on 23 January 2024).

| Speaking Proficiency | Working Memory | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| English | Spanish | ||

| Visual Scene Group | 12.04 (1.44) | 6.04 (1.31) | 9.53 (1.71) |

| Thematic List Group | 12.01 (1.40) | 6.15 (1.41) | 9.70 (1.72) |

| Related | Unrelated | |

|---|---|---|

| Word 1 | avión—vuelo ‘airplane’—‘flight’ | avión—hueso ‘airplane’—‘bone’ |

| Word 2 | vuelo—avión ‘flight’—‘airplane’ | vuelo—hueso ‘flight’—‘bone’ |

| El profesor The professor | se acostó lay down | en la arena on the sand | a leer. to read. | ||

| preverb REGION 1 | 500 ms PAUSE | verb REGION 2 | 500 ms PAUSE | target REGION 3 | postarget REGION 4 |

| Session 1 | Session 2 | Session 3 | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Purpose | Pretest + Training 1 | Training 2 + Immediate Post-Test | Delayed Post-Test (No Training) |

| Task Order | Visual World Training | Training Visual World | Visual World |

| Estimate | Std. Error | t Value | Pr (>|t|) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Intercept | 0.02 | 0.02 | 0.84 | n.s. |

| Condition | 0.08 | 0.02 | 3.24 | <0.01 |

| L1 | −0.03 | 0.05 | −0.71 | n.s. |

| Condition: L1 | 0.19 | 0.05 | 3.81 | <0.001 |

| Estimate | Std. Error | t Value | Pr (>|t|) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Intercept | 0.15 | 0.03 | 4.52 | <0.001 |

| Condition | 0.09 | 0.03 | 3.57 | <0.001 |

| L1 | 0.10 | 0.05 | 2.03 | <0.05 |

| Condition: L1 | 0.12 | 0.05 | 2.37 | <0.05 |

| Estimate | Std. Error | t Value | Pr (>|t|) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Intercept | 0.04 | 0.03 | 1.23 | n.s. |

| Condition | 0.07 | 0.03 | 2.13 | <0.05 |

| Session 2 | −0.07 | 0.03 | −1.89 | n.s. |

| Session 3 | −0.09 | 0.04 | −2.29 | <0.05 |

| Training | −0.03 | 0.04 | −0.81 | n.s. |

| Condition: Session 2 | 0.07 | 0.01 | 6.45 | <0.001 |

| Condition: Session 3 | 0.01 | 0.01 | 13.69 | <0.001 |

| Session 2: Training | 0.03 | 0.04 | 0.84 | n.s. |

| Session 3: Training | 0.12 | 0.04 | 2.67 | <0.05 |

| Condition: Training | 0.04 | 0.04 | 1.00 | n.s. |

| Condition:Session 2: Training | −0.09 | 0.02 | −5.94 | <0.001 |

| Condition:Session 3: Training | −0.16 | 0.02 | −10.58 | <0.001 |

| Estimate | Std. Error | t Value | Pr (>|t|) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Intercept | 0.14 | 0.04 | 3.78 | <0.001 |

| Condition | 0.10 | 0.02 | 3.99 | <0.001 |

| Session 2 | 0.04 | 0.04 | 1.12 | n.s. |

| Session 3 | 0.03 | 0.03 | 0.91 | n.s. |

| Training | 0.03 | 0.04 | 0.68 | n.s. |

| Condition: Session 2 | 0.01 | 0.01 | 1.20 | n.s. |

| Condition: Session 3 | 0.06 | 0.01 | 7.07 | <0.001 |

| Session 2: Training | −0.08 | 0.04 | −1.72 | n.s. |

| Session 3: Training | −0.03 | 0.04 | −0.86 | n.s. |

| Condition: Training | −0.02 | 0.03 | −0.62 | n.s. |

| Condition: Session 2: Training | 0.12 | 0.01 | 9.32 | <0.001 |

| Condition: Session 3: Training | −0.03 | 0.01 | −2.55 | <0.05 |

| Estimate | Std. Error | t Value | Pr (>|t|) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Intercept | 0.25 | 0.05 | 5.39 | <0.001 |

| Condition | 0.21 | 0.04 | 5.45 | <0.001 |

| TL Exposure | −0.06 | 0.06 | −1.04 | n.s. |

| VS Exposure | −0.11 | 0.05 | −2.10 | <0.05 |

| Condition: TL Exposure | −0.12 | 0.05 | −2.36 | <0.05 |

| Condition: VS Exposure | −0.02 | 0.05 | −0.47 | n.s. |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Puscama, M.G. Semantic Network Development in L2 Spanish and Its Impact on Processing Skills: A Multisession Eye-Tracking Study. Languages 2024, 9, 43. https://doi.org/10.3390/languages9020043

Puscama MG. Semantic Network Development in L2 Spanish and Its Impact on Processing Skills: A Multisession Eye-Tracking Study. Languages. 2024; 9(2):43. https://doi.org/10.3390/languages9020043

Chicago/Turabian StylePuscama, M. Gabriela. 2024. "Semantic Network Development in L2 Spanish and Its Impact on Processing Skills: A Multisession Eye-Tracking Study" Languages 9, no. 2: 43. https://doi.org/10.3390/languages9020043

APA StylePuscama, M. G. (2024). Semantic Network Development in L2 Spanish and Its Impact on Processing Skills: A Multisession Eye-Tracking Study. Languages, 9(2), 43. https://doi.org/10.3390/languages9020043