Heritage Spanish in Montreal: An Analysis of Clitics in Spontaneous Production Data

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Theoretical Background

2.1. Heritage Languages

| (1) | Heritage language (HL): |

| A language qualifies as a heritage language if it is a language spoken at home or otherwise readily available to young children, and crucially this language is not a dominant language of the larger (national) society… [A]n individual qualifies as a heritage speaker if and only if he or she has some command of the heritage language acquired naturalistically… although it is equally expected that such competence will differ from that of native monolinguals of comparable age. (Rothman 2009, p. 156) |

| (2) | Characteristics of HL speakers: | |

| a. | They have been raised in bilingual households and possess linguistic competence in two languages. | |

| b. | Their L1 (or one of their L1s) spoken at home is a minority language. | |

| c. | They are usually proficient in the majority language, usually with native or native-like proficiency. | |

| d. | They tend to be less proficient in the HL, whose level of proficiency ranges from minimal and receptive ability to full fluency and native proficiency. | |

2.2. Clitic Pronouns

- Coordination: Clitic pronouns, unlike strong pronouns, cannot be coordinated, as shown in examples (3a) and (3b).

(3) a. Nosotros y vosotros fuimos al cine We and you-PL go.1.PL.PAST to-the cinema ‘We and you went to the cinema.’ b. *Los y las compramos ayer. 3.ACC.PL.MASC and 3.ACC.PL.FEM buy.1PL.PAST yesterday ‘We bought them yesterday.’ - Modification: Unlike strong pronouns, clitics cannot be modified, as shown in examples (4a) (adjective modification) and (4b) (adverbial modification).

(4) a. *{beau; rapide; …} il (Cardinaletti and Starke 1999, p. 151) *{beautiful; quick; …} il b. *{vraiment; seulement; …} il *{really; only; …} il - Emphasis: Clitics cannot be emphasised, while pronouns can be easily emphasised, as in (5a) and (5b).

(5) a. La saludé en el CINE. 3.ACC.SG.FEM greet.1SG.PAST in the cinema ‘I greeted her at the cinema.’ b. Me encontré con ELLA. 1.REFL.SG meet.1SG.PAST with her ‘I met her.’ - Isolation: Unlike strong pronouns, clitics cannot appear in isolation as a response to a question, as shown in example (6).

(6) ¿A quien llamaste? To who call.2SG.PAST ‘Who did you call?’ a. *La. 3.ACC.SG.FEM ‘Her.’ b. A ella. To she ‘Her.’

2.2.1. Clitics in Spanish

2.2.2. Clitics in French

| (7) | a. | Je | vois | Marie | et | Paul. | |||

| I | see.1SG.PRES | Marie | and | Paul | |||||

| ‘I see Marie and Paul.’ | |||||||||

| b. | *Je | le | vois | et | Marie. | ||||

| I | him | see.1SG.PRES | and | Marie | |||||

| ‘I see him and Marie.’ | |||||||||

| c. | *Je | le | et | la | vois. | ||||

| I | him | and | her | see.1SG.PRES | |||||

| ‘I see him and | |||||||||

| (8) | a. | Il | chante | et | danse. | |||||

| He | sing.3SG.PRES | and | dance.3SG.PRES | |||||||

| ‘He sings and dances.’ | ||||||||||

| b. | *Chante-t-il | et | danse? | |||||||

| Sing.3SG.PRES-he | and | dance.3.SG.PRES | ||||||||

| ‘Does he sing and dance?’ | ||||||||||

2.2.3. Contrasting Clitic Systems: Spanish vs. French

| (9) | Je | parlerai, | moi | (Fernández Soriano 1989, p. 178) | ||

| I | speak.1SG.FUT, | 1.SG | ||||

| ‘I | will | speak’ | ||||

| (10) | a. | Juan | lo | quiso | decir. | (clitic climbing) | ||

| Juan | 3.SG.ACC.MASC | want.3.SG.PAST | say.INF | |||||

| ‘Juan wanted to say it.’ | ||||||||

| b. | Juan | quiso | decirlo. | (no clitic climbing) | ||||

| Juan | want.3SG.PAST | say.INF-3.SG.ACC.MASC | ||||||

| ‘Juan wanted to say it.’ | ||||||||

| (11) | a. | Jean | a voulu | le | dire | (no clitic climbing) | ||

| Jean | want.3SG.PAST | 3.SG.ACC.MASC | say.INF | |||||

| ‘Jean wanted to say it.’ | ||||||||

| b. | *Jean | le | a voulu | dire. | (clitic climbing) | |||

| Juan | 3.SG.ACC.MASC | want.3SG.PAST | say.INF | |||||

| ‘Jean wanted to say it.’ | ||||||||

| (12) | a. | Él | se | lo | da. |

| He | 3SG.DAT | 3SG.ACC | give.3.SG.PRES | ||

| ‘He gives it to her.’ | |||||

| b. | Il | le | lui | donne. | |

| He | 3SG.ACC | 3SG.DAT | give.3.SG.PRES | ||

| ‘He gives it to her.’ | |||||

| (13) | En | France, | on | aime | bien | manger. | |

| In | France, | on | like.3SG.PRES | well | eat.INF | ||

| ‘In France, people like to eat well.’ | |||||||

2.3. Clitic Acquisition by Heritage Speakers

| (14) | Rosa | no | gasta | mucho | dinero | (López Otero et al. 2023a, p. 174) | ||||||||||

| Rosa | not | spend.3SG.PRES | much | money | ||||||||||||

| en | ropa, | pero | zapatos | sí | los | compra. | ||||||||||

| in | clothes | but | shoes | yes | 3SG.ACC.MASC | buy.3SG.PRES | ||||||||||

| ‘Rosa does not spend much money on clothes, but shoes she buys.’ | ||||||||||||||||

3. Materials and Methods

3.1. Goals of the Study

3.2. Sample

- HL Speakers of Spanish Group (N = 10): This group comprised adult speakers of Spanish as their HL, all of whom were second-generation immigrants. Within this group, there were the following:

- Simultaneous bilingual participants (N = 4) (balanced gender distribution; age range 21–25, mean age: 22.5 years): participants exposed to both French and Spanish from birth.

- Sequential bilingual participants (N = 6) (2 males and 4 females; age range 18–26, mean age: 22 years): participants exposed to Spanish first and then to French between the ages of 4 and 7.

- 2.

- Speakers of Spanish as L1 (N = 10; balanced gender distribution; age range 24–70, mean age: 47): This group consisted of adult L1 speakers of Spanish, representing different dialects. Participants in this group had been living in Montreal for 5 years or less. They may have had French, English, or another Romance language as their L2, but all participants in this group were born and raised as monolingual speakers of Spanish in their respective countries of origin, and Spanish remains their dominant language.

3.3. Data Collection

3.3.1. Elicitation Tasks

3.3.2. Corpora

3.3.3. Procedure

- Alternating inherent pronominal verbs:4 These verbs can occur with or without the pronominal particle and do not participate in the causative alternation. They may function as either transitive or intransitive verbs and the presence of the particle may involve changes in the argument structure of the predicate.5 Examples include encontrar(se) (to find) and llevar(se) (to take).

- Non-alternating inherent pronominal verbs: These verbs necessitate the pronominal particle and do not undergo causative alternation. For example, desmayarse (to faint) and ponerse (a hacer algo) (to start).

- Movement pronominal verbs: These verbs, except ir(se) (to go), which changes meaning, exhibit alternation and imply movement. For instance, salir(se) (to get out).

- Anticausative pronominal verbs: These verbs may undergo causative alternation, and in the resulting structures, the presence of the pronominal particle is obligatory. For example, derretirse (to melt) and romper(se) (to break).

- Non-anticausative pronominal verbs: These are intransitive verbs that do not undergo causative alternation and can occur with or without the pronominal particle without any change in the argument structure of the predicate.6 Examples include caer(se) (to fall) and morir(se) (to die).

- Consumption pronominal verbs: These verbs alternate and entail either material or psychological consumption. For instance, comer(se) (to eat) and fumar(se) (to smoke).

- Reflexive and reciprocal verbs: These are agentive verbs whose argument structure involves co-referentiality between subject and object. For example, lavarse (wash oneself) and saludarse (greet each other).

4. Results

4.1. Native Speakers

| (15) | a. | […] | que | él | lo | pagaría | |||||

| that | he | 3SG.ACC.MASC | pay.3SG.COND | ||||||||

| me | imagino. | […] | |||||||||

| 1SG.REFL | imagine.1SG.PRES | ||||||||||

| ‘[…] that he would pay for it, I imagine’ [ESL1011_Oral:32] | |||||||||||

| b. | […] | aprovecha | y | escápate | ahora. | ||||||

| seize.2SG.PRES | and | escape.2SG.PRES-2SG.REFL | now | ||||||||

| ‘[…] seize the opportunity and escape now […]’ [ESL1016_Oral:23] | |||||||||||

| (16) | […] | se | fumó | uno | y | le | dio | ||

| 3.REFL | smoke.3SG.PAST | one | and | 3SG.DAT | give.1SG.PAST | ||||

| el | resto | a | unos | niños. | |||||

| the | rest | to | Indef.PLURAL | kids | |||||

| ‘[…] he smoked one and gave the rest to some kids.’ [ESL1001_ESC:11] | |||||||||

| (17) | a. | […] | vio | lo | ocurrido | y | Ø = le | ||||||||||

| see.3SG.PAST | the | happen.PARTICIPLE | and | Ø = 3SG.DAT | |||||||||||||

| alertó | del | robo | al | dueño. | |||||||||||||

| alert.3SG.PAST | of-the | theft | to-the | Owner | |||||||||||||

| ‘[…] she saw what happened and alerted the owner of the theft.’ [ESL1010_ESC:3] | |||||||||||||||||

| b. | […] | y | una | mujer | que | pasó | por | allí | |||||||||

| and | one | woman | that | pass.3SG.PAST | by | there | |||||||||||

| Ø = lo | vio | todo. | |||||||||||||||

| Ø = 3SG.ACC.MASC | see.3SG.PAST | all. | |||||||||||||||

| ‘[…]and a woman passing by saw it all.’ [ESL1010_ORA:8] | |||||||||||||||||

| (18) | […] | enseguida | lo | record | y | |

| inmmediatly | 3SG.ACC.MASC | remember.3SG.PAST | and | |||

| Ø = se | quedó | pensativa. | ||||

| Ø = 3.REFL | stay.3SG.PAST | Thoughtful | ||||

| ‘[…] she immediately remembered and thought about it.’ [ESL1002_ORA:39] | ||||||

| (19) | […] | en | eso | llegó | el | camión | y | Ø = se |

| in | that | arrive.2SG.PAST | the | truch | and | Ø = 3SG.REFL | ||

| subió. | ||||||||

| get.3SG.PAST-in | ||||||||

| ‘[…] then the truck arrived and he got in.’ [ESL1011_ORA:36] | ||||||||

| (20) | […] | y | los | dos | Ø = se | cayeron | al | suelo. |

| and | the | two | Ø = 3.REFL | fall.3PL.PAST | to-the | ground | ||

| ‘[…] and both of them fell on the ground [ESL1008_ESC:2].’ | ||||||||

| (21) | […] | le | encendió | y | Ø = se | lo | ||

| 3SG.DAT | lit.3SG.PAST | and | Ø = 3.REFL | 3SG.ACC.MASC | ||||

| fumó | exhalando | bastante | humo. | |||||

| smoke.3SG.PAST | exhale.GERUND | quite | smoke | |||||

| ‘[…] he lit it and smoked it, exhaling a lot of smoke.’ [ESL1008_ESC:12] | ||||||||

4.2. Heritage Speakers

| (22) | […] | y, | caballerosamente, | dijo: | «yo | me | |||||

| and, | chivalrously, | say.3SG.PAST | «I | 1SG.REFL | |||||||

| robé | el | pan, | no | ella.» | |||||||

| steal.1SG.PAST | the | bread, | not | her» | |||||||

| ‘[…] and, chivalrously, he said: «I stole the bread, not her»’ [SEQ007_ESC:11] | |||||||||||

| (23) | […] | tú | también | te | puedes | escapar. |

| you | too | 2SG.REFL | can.3SG.PRES | escape.INF | ||

| ‘[…] you too can escape.’ [SIM003_ORA:32] | ||||||

| (24) | […] | empezó | a | mirar | cosas, | le | |||||

| start.3SG.PAST | to | loo.INF | things, | 3SG.DAT | |||||||

| regaló | a | unos | niños | también | |||||||

| gift.3SG.PAST | to | ones | kids | too | |||||||

| ‘[…] he started looking at things, he also gifted some children’ [SIM001_ORA:17] | |||||||||||

| (25) | […] | y | comenzó | a | regalár-Ø = se-los | |

| and | start.3SG.PAST | to | gift-Ø = 3.REFL-3PL.ACC.MASC | |||

| a | unos | niños. | ||||

| to | ones | kids | ||||

| ‘[…] and he started to gift them to some children.’ [SEQ001_ORA:16] | ||||||

| (26) | […] | para | que | ella | pudiera | escapar-Ø = se. |

| for | that | she | can.3SG.PAST.SUBJ | escape.INF-Ø = 3.REFL | ||

| ‘[…] so that she could escape.’ [SEQ006_ESC:18] | ||||||

| (27) | […] | la | chica | también | Ø = se | subió | al | carro |

| the | girl | too | Ø = 3.REFL | get in.3SG.PAST | to-the | wagon | ||

| ‘[…] the girl also got on the wagon.’ [SEQ005_ESSC:10] | ||||||||

| (28) | Entonces, | los | dos | Ø = se | cayeron | del | auto. |

| Then, | the | two | Ø = 3.REFL | fall.3PL.PAST | of-the | car | |

| ‘Then, both fell out of the car’ [SEQ003_ORA:25] | |||||||

| (29) | […] | para | fumar-Ø = se | un | cigarro. |

| to | smoke.INF-Ø = 3.REFL | one | cigarrete | ||

| ‘[…] to smoke a cigarette.’ [SEQ006_ESC:12] | |||||

| (30) | […] | intenta | arrestar-Ø = los | a | los | dos. |

| try.3SG.PRES | arrest.INF-Ø = 3PL.ACC.MASC | to | the | two | ||

| ‘[…] tries to arrest them both.’ [SIM002_ORA:14] | ||||||

| (31) | […] | y | Ø = se | lo | dijo | al | señor. |

| and | Ø = 3.REFL | 3.SG.ACC.MASC | say-3SG.PAST | to-the | man | ||

| ‘[…] and he told the man.’ [SIM001_ESC:2] | |||||||

| (32) | Entonces, | el | policía | Ø = se | llevó | al | señor |

| Then, | the | policeman | Ø = 3.REFL | take.3SG.PAST | to-the | man | |

| en | lugar | de | La | mujer. | |||

| in | place | of | the | woman | |||

| ‘Then, the policeman took the man instead of the woman.’ [SEQ001_ES:8] | |||||||

5. Discussion

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A. Written and Oral Clitic Production of L1 and HL Speakers

| Words | Acc | Dat | Refl | VP.IN.AL | VP.IN. NONAL | Mov | Antic | Nonantic | Consump | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| grammatical productions | 6207 | 111 | 90 | 25 | 41 | 98 | 8 | 10 | 0 | 11 |

| ungrammatical productions | 6207 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| grammatical omissions | 6207 | 2 | 4 | 0 | 38 | 0 | 6 | 4 | 8 | 2 |

| ungrammatical omissions | 6207 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Words | Accusative Doubling | Dative Doubling | |

|---|---|---|---|

| grammatical productions | 6207 | 4 | 22 |

| ungrammatical productions | 6207 | 0 | 1 |

| grammatical omissions | 6207 | 2 | 4 |

| ungrammatical omissions | 6207 | 0 | 0 |

| Words | Acc | Dat | Refl | VP.IN.AL | VP.IN. NONAL | Mov | Antic | Nonantic | Consump | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| grammatical productions | 4644 | 75 | 67 | 15 | 31 | 65 | 6 | 3 | 4 | 1 |

| ungrammatical productions | 4644 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| grammatical omissions | 4644 | 0 | 3 | 0 | 24 | 0 | 5 | 0 | 13 | 3 |

| ungrammatical omissions | 4644 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 |

| Words | Accusative Doubling | Dative Doubling | |

|---|---|---|---|

| grammatical productions | 4644 | 1 | 13 |

| ungrammatical productions | 4644 | 0 | 2 |

| grammatical omissions | 4644 | 0 | 3 |

| ungrammatical omissions | 4644 | 0 | 0 |

| Words | Acc | Dat | Refl | VP.IN.AL | VP.IN. NONAL | Mov | Antic | Nonantic | Consump | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| grammatical productions | 1846 | 32 | 24 | 0 | 15 | 30 | 4 | 5 | 5 | 1 |

| ungrammatical productions | 1846 | 0 | 3 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| grammatical omissions | 1846 | 0 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 2 |

| ungrammatical omissions | 1846 | 1 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Words | Accusative Doubling | Dative Doubling | |

|---|---|---|---|

| grammatical productions | 1846 | 6 | 11 |

| ungrammatical productions | 1846 | 0 | 3 |

| grammatical omissions | 1846 | 0 | 1 |

| ungrammatical omissions | 1846 | 1 | 1 |

| Words | Acc | Dat | Refl | VP.IN.AL | VP.IN. NONAL | Mov | Antic | Nonantic | Consump | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| grammatical productions | 971 | 16 | 11 | 1 | 11 | 9 | 1 | 1 | 3 | 0 |

| ungrammatical productions | 971 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| grammatical omissions | 971 | 1 | 2 | 0 | 6 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 |

| ungrammatical omissions | 971 | 2.00 | 1.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 |

| Words | Accusative Doubling | Dative Doubling | |

|---|---|---|---|

| grammatical productions | 971 | 2 | 4 |

| ungrammatical productions | 971 | 0 | 0 |

| grammatical omissions | 971 | 0 | 2 |

| ungrammatical omissions | 971 | 2 | 1 |

| Words | Acc | Dat | Refl | VP.IN.AL | VP.IN. NONAL | Mov | Antic | Nonantic | Consump | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| grammatical productions | 2572 | 36 | 31 | 4 | 31 | 35 | 7 | 4 | 9 | 5 |

| ungrammatical productions | 2572 | 0 | 3 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| grammatical omissions | 2572 | 0 | 2 | 0 | 12 | 0 | 2 | 0 | 3 | 1 |

| ungrammatical omissions | 2572 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Words | Accusative Doubling | Dative Doubling | |

|---|---|---|---|

| grammatical productions | 2572 | 1 | 6 |

| ungrammatical productions | 2572 | 0 | 1 |

| grammatical omissions | 2572 | 0 | 1 |

| ungrammatical omissions | 2572 | 0 | 1 |

| Words | Acc | Dat | Refl | VP.IN.AL | VP.IN. NONAL | Mov | Antic | Nonantic | Consump | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| grammatical productions | 2642 | 30 | 36 | 6 | 34 | 37 | 12 | 10 | 7 | 2 |

| ungrammatical productions | 2642 | 0 | 4 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| grammatical omissions | 2642 | 0 | 2 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 4 | 0 | 3 | 3 |

| ungrammatical omissions | 2642 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 1.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 1.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 |

| Words | Accusative Doubling | Dative Doubling | |

|---|---|---|---|

| grammatical productions | 2642 | 0 | 11 |

| ungrammatical productions | 2642 | 0 | 2 |

| grammatical omissions | 2642 | 0 | 3 |

| ungrammatical omissions | 2642 | 0 | 1 |

| 1 | In this paper, we adopt Hakuta’s (2009) definition of bilingualism (and multilingualism) as the coexistence of more than one linguistic system within an individual, in contrast to monolingualism. However, for adult acquisition of a non-native language, we speak of L2. This exclusion is crucial because L2 learners acquire their additional language later in life, typically lacking the same naturalistic, immersive exposure that early bilinguals experience. Consequently, their proficiency and the cognitive processes involved differ significantly from those of individuals who are exposed to and acquire two languages from a young age. |

| 2 | The label L1 does not imply that HL speakers are not native speakers of Spanish. The term L1 simply refers to the first language acquired, which, for HL speakers, can be (and often is) their HL. |

| 3 | In our codification, third-person dative included cases of so-called spurious se, which refers to the replacement of le for se in sentences like Se lo doy (I give it to her) in contrast with the ungrammatical *Le lo doy (I give it to her). No cases of the le and lo combination were found in the data. |

| 4 | Inherent pronominal verbs are pronominal regardless of the syntactic configuration in which they appear (e.g., desmayarse [faint]), versus other verbs, whose pronominality depends on structural factors, such as anticausatives (e.g., derretirse [melt]), reflexives (e.g., peinarse [comb oneself]), and reciprocals [e.g., saludarse [greet each other]). |

| 5 | For instance, the verb reirse (to laugh) accepts a prepositional complement when accompanied by the pronominal particle reirse de algo (to laugh at something). Conversely, the verb reir (to laugh), without the pronominal particle se, does not admit such a prepositional complement: reir *de algo (to laugh at something). |

| 6 | For example, the verb caer [fall] admits a prepositional phrase headed by the preposition de (e.g., caer del piso primero [fall from the first floor]), and so does the verb caerse [fall], with the pronominal particle se (caerse del piso primero [fall from the first floor]). |

| 7 | Dialectal variation was considered in the encoding of data; however, no relevant findings were encountered in this regard. Therefore, it has not been considered as a variable for analysis. |

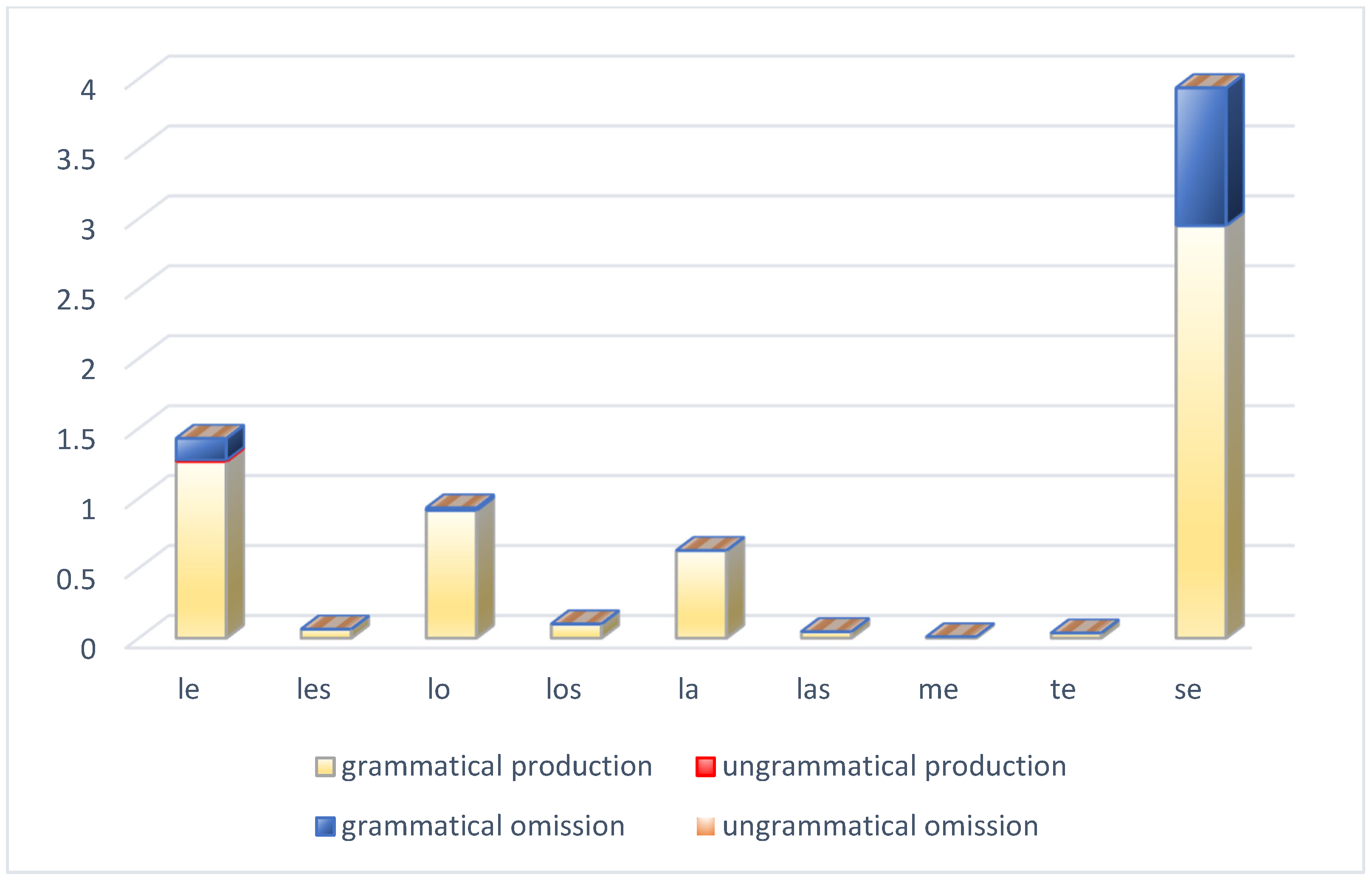

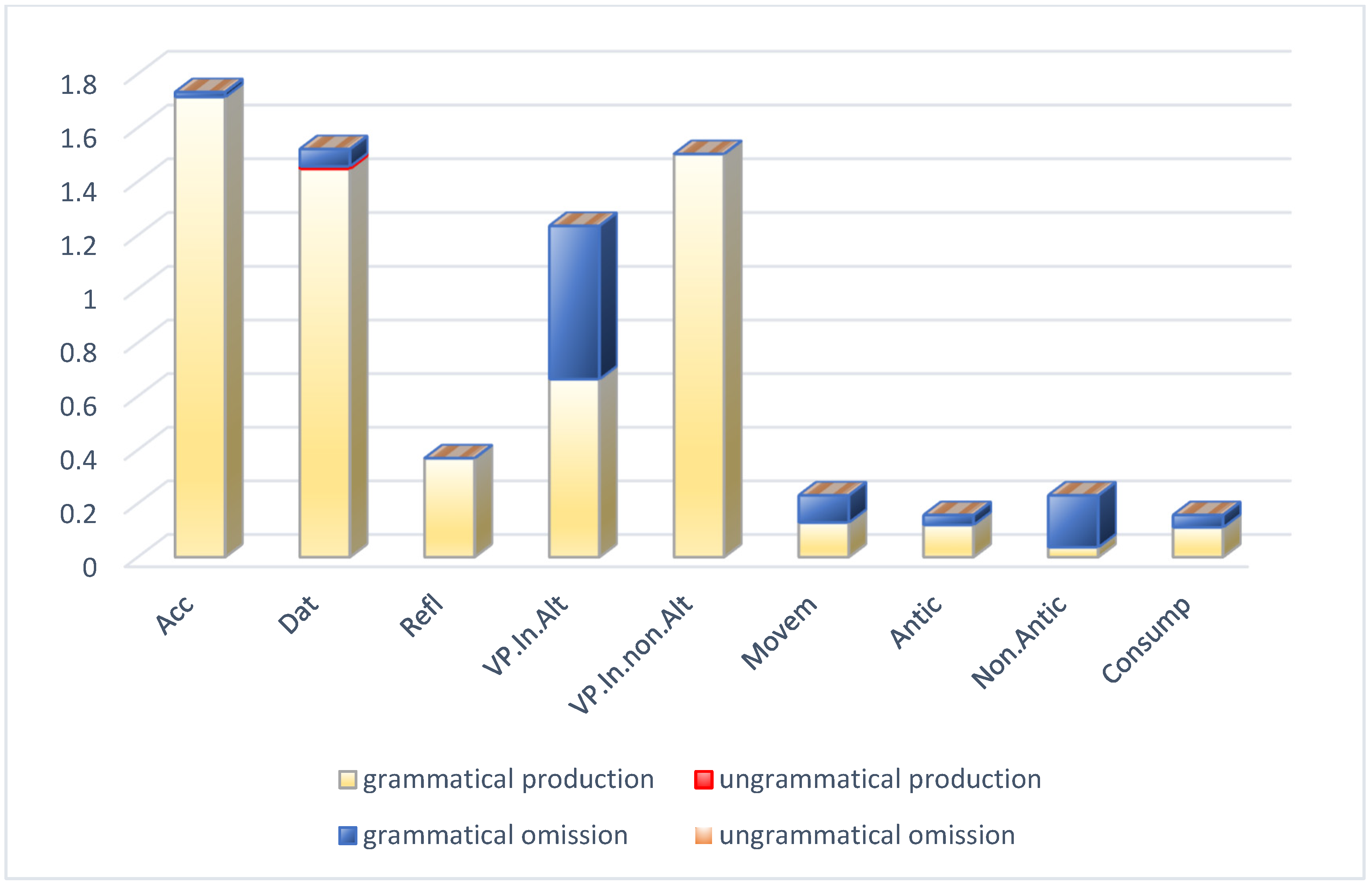

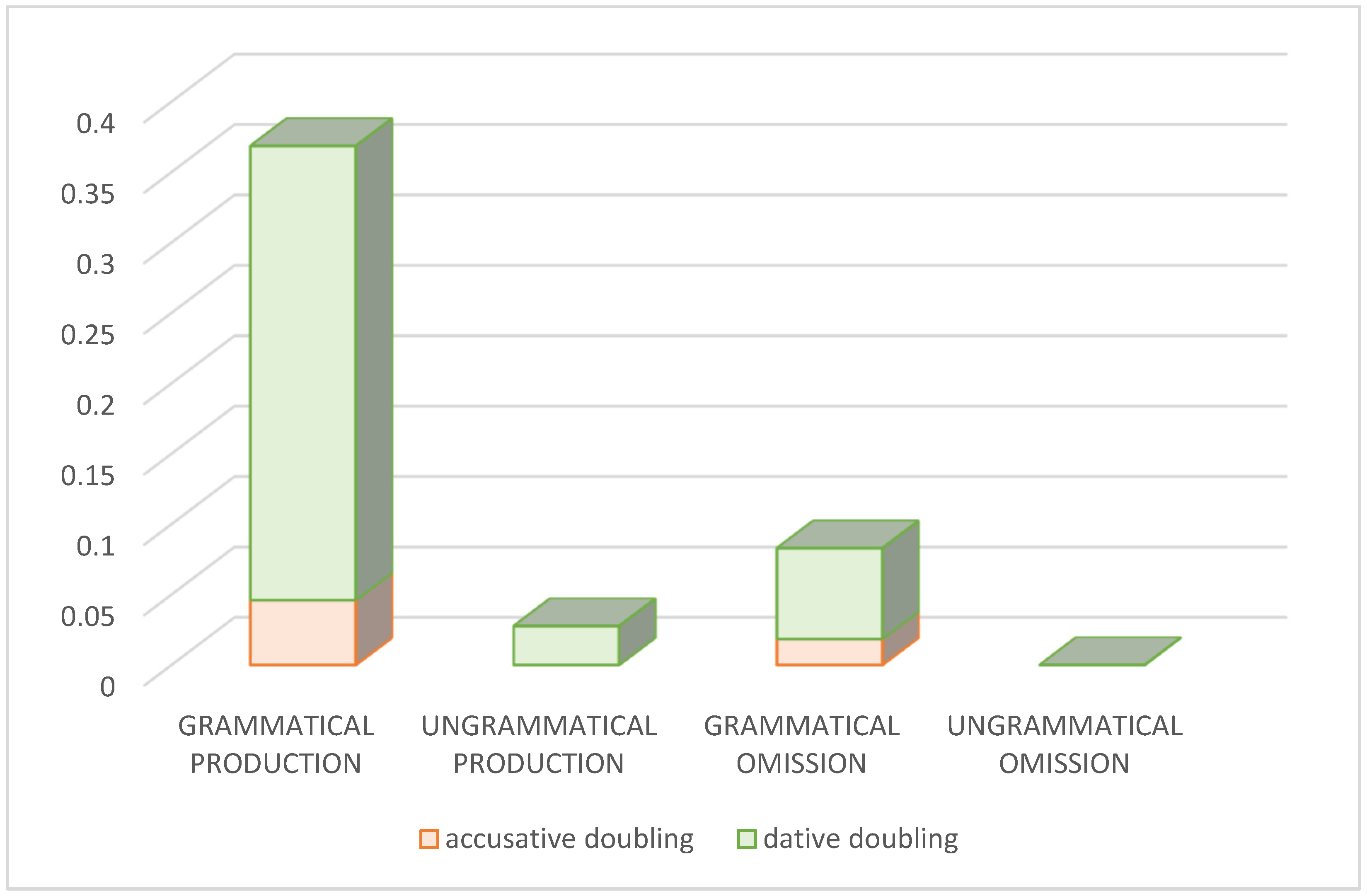

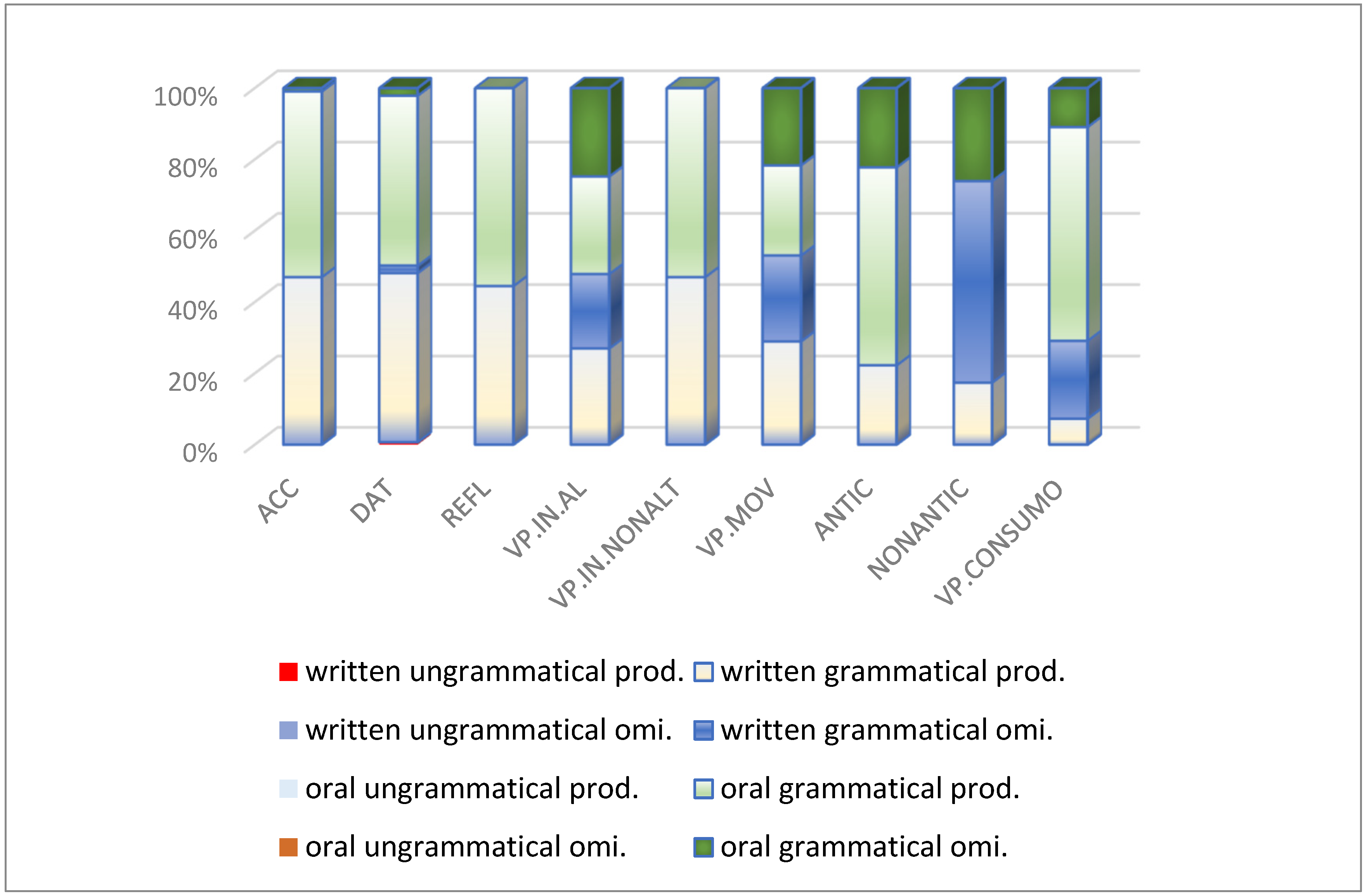

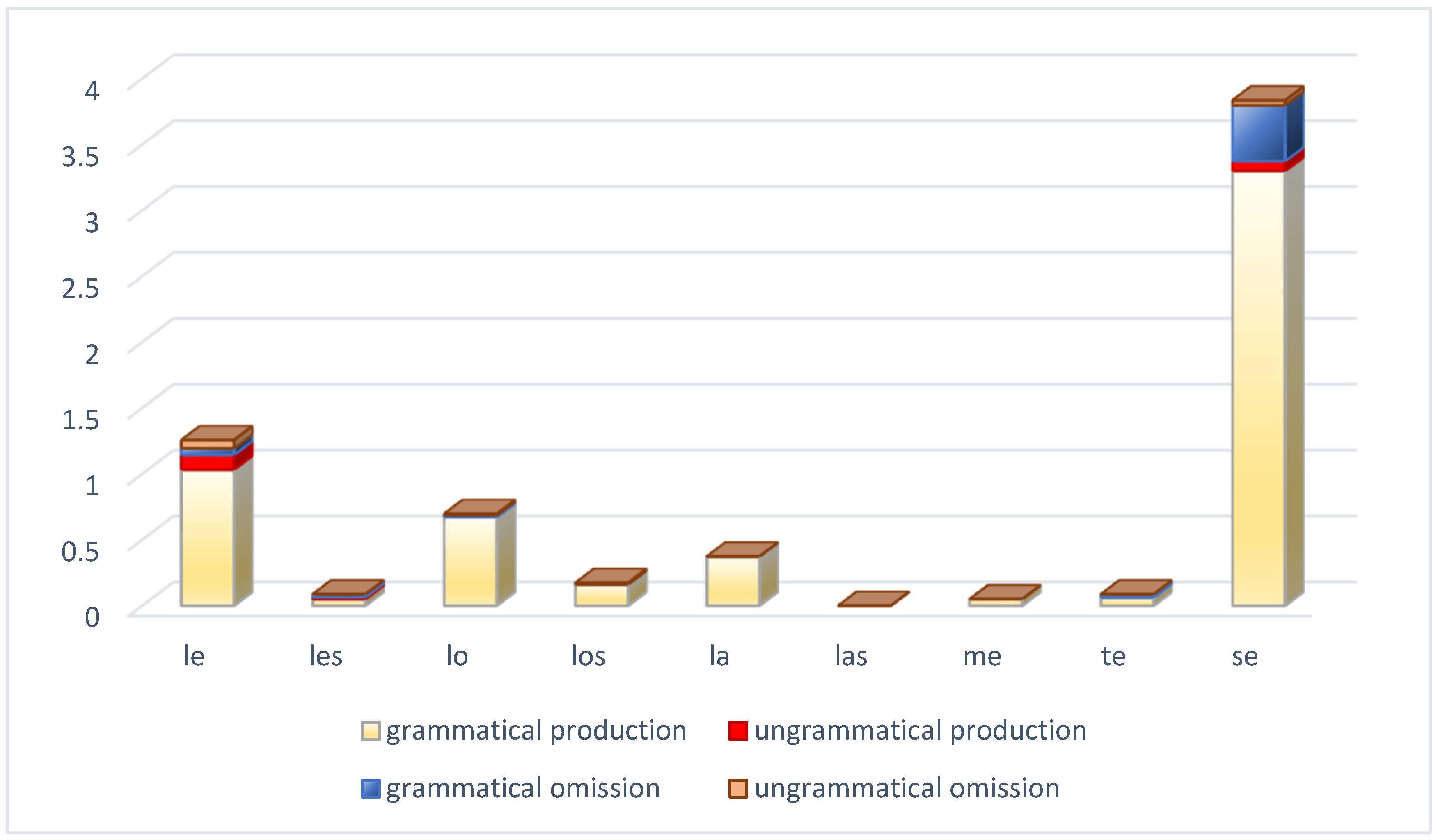

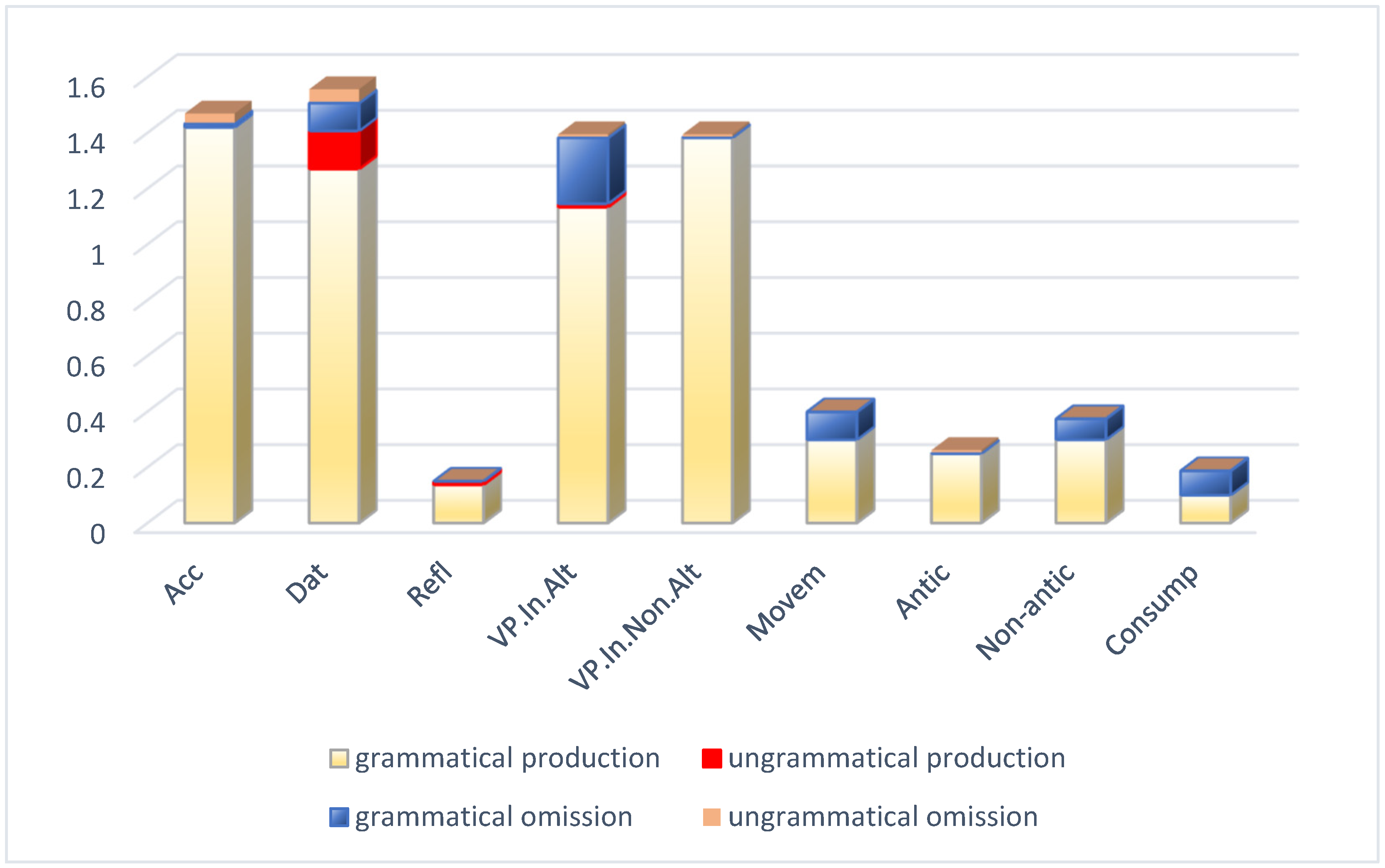

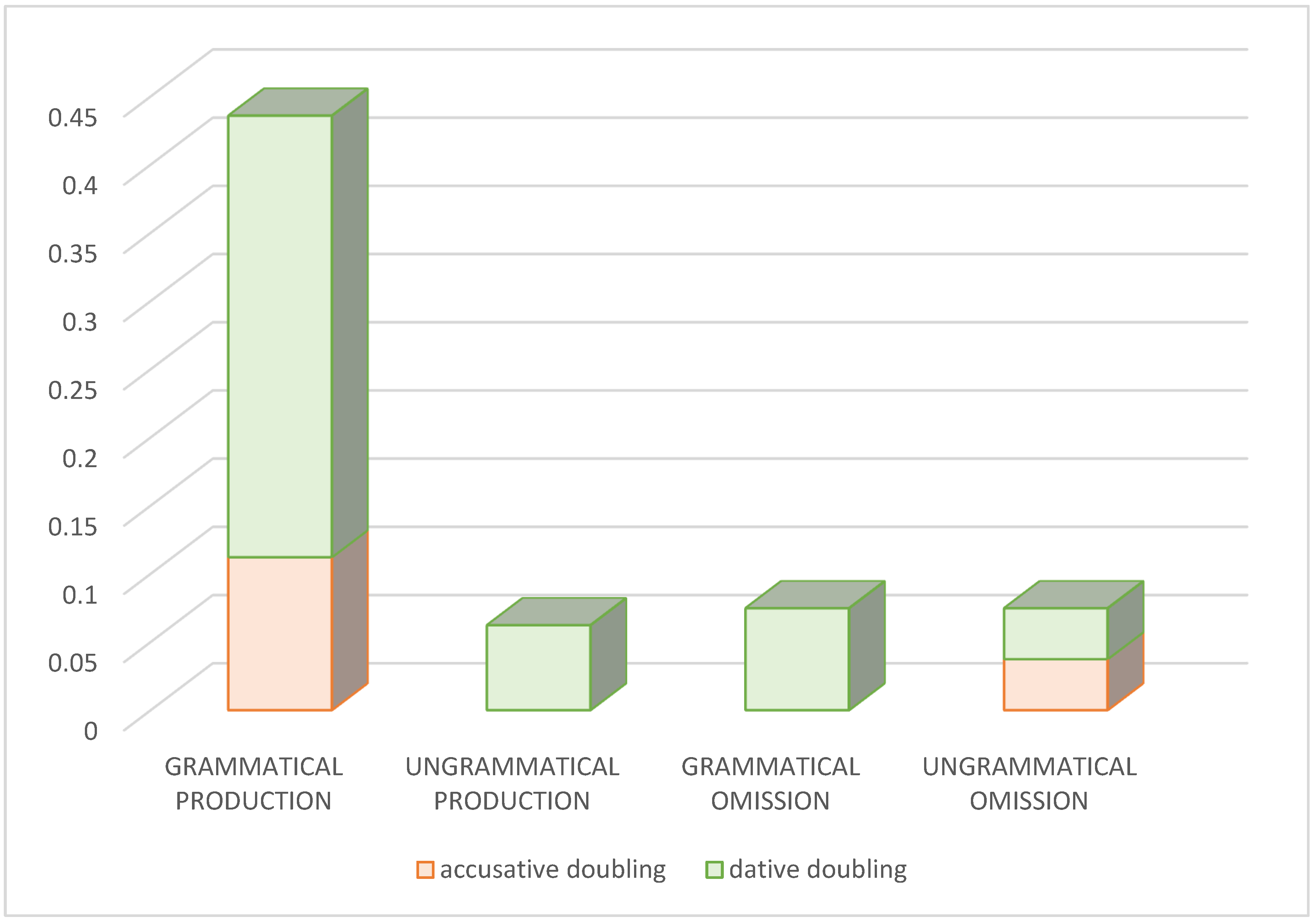

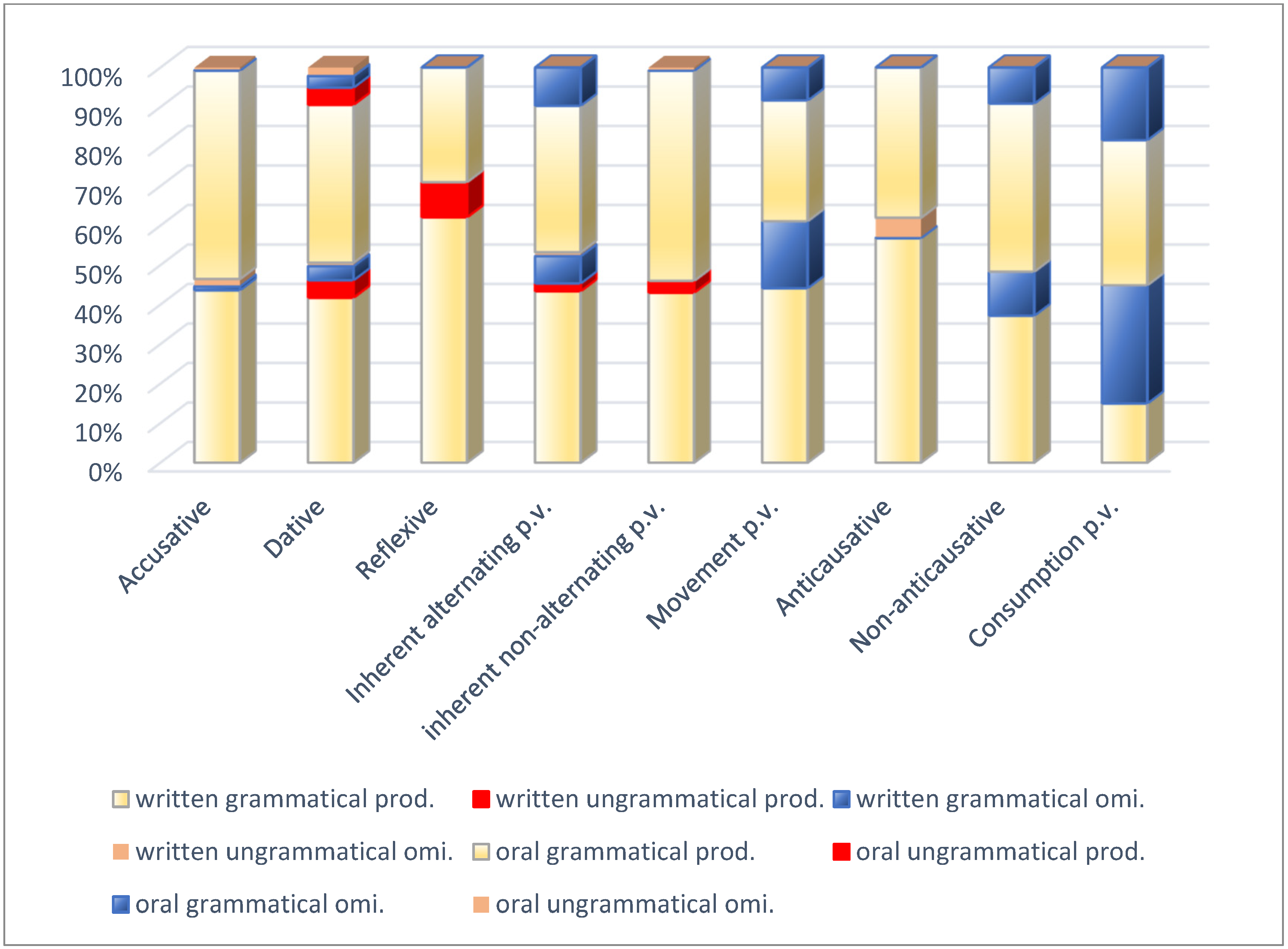

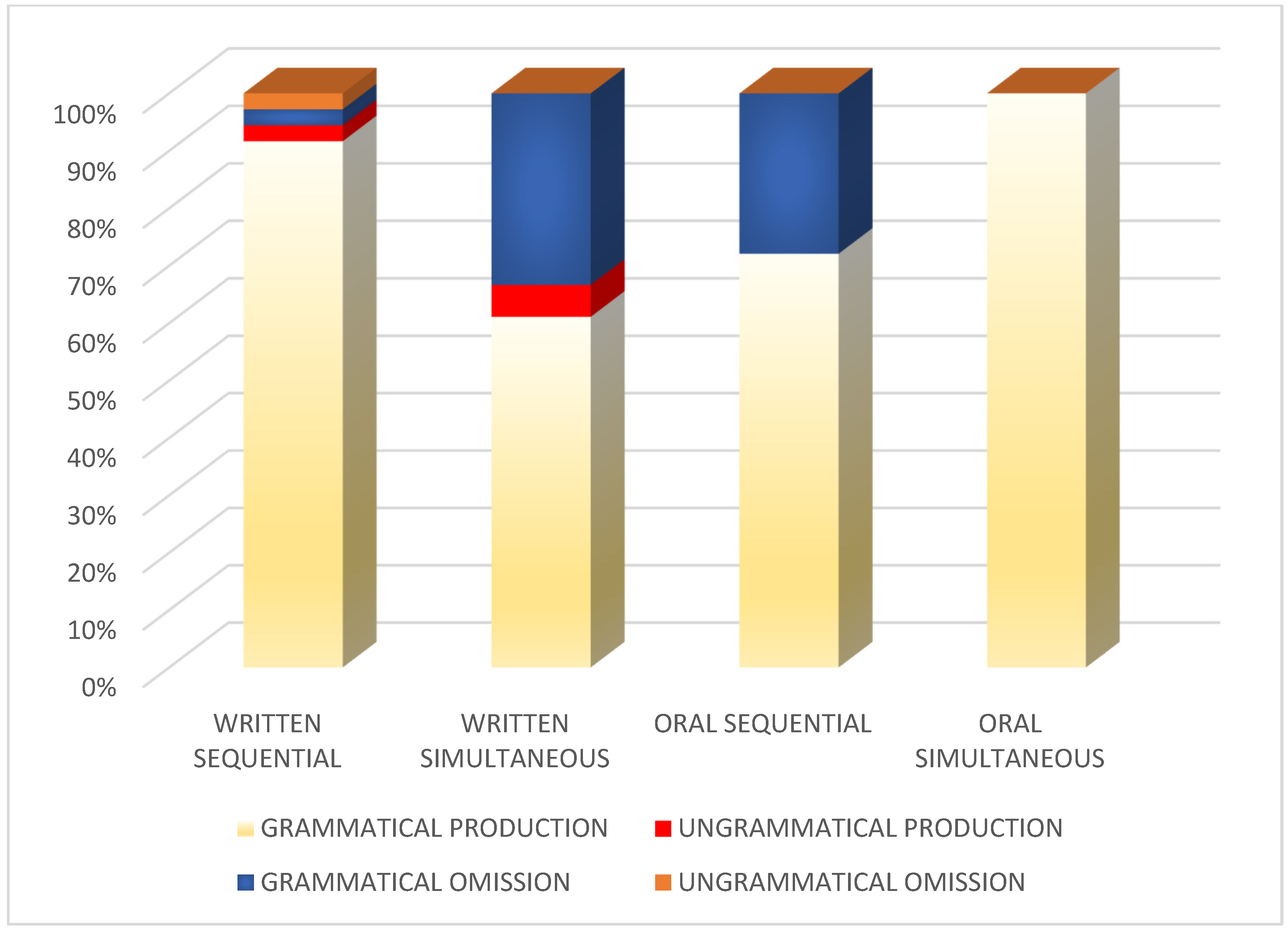

| 8 | The data can be consulted in Appendix A. |

| 9 | The figure presents weighted data rather than raw figures. Specifically, we calculated the frequency of clitics relative to the total number of words. For instance, an occurrence rate of 1.26 for le indicates that 1.26% of the total words were the clitic le. Raw data can be found in Appendix A. |

| 10 | One anonymous reviewer wondered if participants may have avoided clitic clusters by just producing one of the clitics. We considered this possibility in a preliminary analysis of the data. However, we discarded it as we questioned the viability of this exercise. It implied that we would have to code avoidance strategies, which typically include choosing a simpler structure over a more complex one. In practice, the participant simply produced a grammatical structure with one clitic, which is an acceptable linguistic choice. We considered that deciding whether these structures were—or were not—intentionally used to avoid a cluster involved making subjective assumptions about the speaker’s cognitive processes. Given the speculative nature of this kind of analysis, we did not proceed any further. |

References

- Alba de la Fuente, Anahí, Maura Cruz Enríquez, and Hugues Lacroix. 2018. Mood Selection in Relative Clauses by French–Spanish Bilinguals: Contrasts and Similarities between L2 and Heritage Speakers. Languages 3: 31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baal, Yvone, and David Natvig. 2021. Introduction to the Special Issue on Heritage Languages & Bilingualism. Nordic Journal of Linguistics 44: 99–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benmamoun, Elabbas, Silvina Montrul, and Maria Polinsky. 2013. Heritage Languages and Their Speakers: Opportunities and Challenges for Linguistics. Theoretical Linguistics 39: 129–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bogard, Sergio. 1999. La Duplicación con Clítico: Una Manifestación de Concordancia Sintáctica en Español. In El Centro de Lingüística Hispánica y la Lengua Española. Edited by F. Colombo Airoldi. Mexico City: Universidad Nacional Autónoma de México, pp. 189–203. [Google Scholar]

- Bogard, Sergio. 2015. Los Clíticos Pronominales del Español. Estructura y Función. Nueva Revista de Filología Hispánica 63: 1–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bowles, Melissa A. 2011. Measuring Implicit and Explicit Linguistic Knowledge: What Can Heritage Language Learners Contribute? Studies in Second Language Acquisition 33: 247–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bruhn de Garavito, Joyce. 1999a. The Se Constructions in Spanish and Near-Native Competence. Spanish Applied Linguistics: A Forum for Theory and Research 3: 247–95. [Google Scholar]

- Bruhn de Garavito, Joyce. 1999b. The Syntax of Spanish Multifunctional Clitics and Near-Native Competence. Doctoral thesis, McGill University, Montreal, QC, Canada. [Google Scholar]

- Bruhn de Garavito, Joyce, and Silvina Montrul. 1996. Verb Movement and Clitic Placement in French and Spanish as a Second Language. In Proceedings of the 20th Annual Boston University Conference on Language Development. Edited by Andy Stringfellow, Dalia Cahana-Amitay, Elizabeth Hughes and Andrea Zukowski. Somerville: Cascadilla Press, pp. 123–34. [Google Scholar]

- Camacho, José, and Alena Kirova. 2018. Adverb placement among heritage speakers of Spanish. Glossa: A Journal of General Linguistics 3: 53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Camacho Taboada, María Victoria. 1998. El concepto de clítico en la teoría gramatical. Interlingüística 9: 81–84. [Google Scholar]

- Cardinaletti, Anna, and Michal Starke. 1999. The Typology of Structural Deficiency: A Case Study of Three Classes of Pronouns. In Clitics in the Languages of Europe. Edited by Henk van Riemsdijk. Berlin: Mouton de Gruyter, pp. 145–230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carreira, María, and Olga Kagan. 2018. Heritage language education: A proposal for the next 50 years. Foreign Language Annals 51: 152–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chaplin, Charlie. 1936. Modern Times. Beverly Hills: United Artists. [Google Scholar]

- Choi-Jonin, Injoo, and Véronique Lagae. 2015. Les pronoms personnels clitiques. Encyclopédie Grammaticale du Français. Available online: http://encyclogram.fr/notx/006/006_Notice.php (accessed on 15 November 2024).

- Colomina Samitier, María Pilar. 2016. Aspectos morfosintácticos de la combinación de clíticos en algunas variedades iberorromances. Revista Española de Lingüística 46: 7–37. [Google Scholar]

- Cruz Enríquez, Maura. 2019. Función-Significado-Forma: Un Modelo Para el Estudio de los Tiempos Verbales Del Español. Doctoral thesis, Université de Montréal, Montreal, QC, Canada. Available online: https://papyrus.bib.umontreal.ca/xmlui/handle/1866/22635 (accessed on 15 November 2024).

- Cruz Enríquez, Maura, and Anahí Alba de la Fuente. 2024. Past tenses in narrative productions: How do advanced Spanish second language speakers compare to native speakers? Semas. Revista de Lingüística Teórica y Aplicada 5: 27–46. [Google Scholar]

- Cummins, Jim. 1991. Heritage Languages. The Canadian Modern Language Review 47: 601–5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cummins, Jim. 2005. A Proposal for Action: Strategies for Recognizing Heritage Language Competence as a Learning Resource Within the Mainstream Classroom. The Modern Language Journal 89: 585–92. [Google Scholar]

- DeMelo, Nicole. 2014. ¿Cómo se conserva una lengua de herencia?: El caso del español en Montreal. Master thesis, Université de Montréal, Montreal, QC, Canada. Available online: https://papyrus.bib.umontreal.ca/xmlui/bitstream/handle/1866/11701/DeMelo_Nicole_2014_memoire.pdf?sequence=2&isAllowed=y (accessed on 15 November 2024).

- Domínguez, Laura. 2009. Charting the route of bilingual development: Contributions from heritage speakers’ early acquisition. International Journal of Bilingualism 13: 271–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Escobar, Linda, and Ismael I. Teomiro. 2016. The Gradual Acquisition of Clitic “Se” in Spanish L2. Topics in Linguistics 17: 17–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fernández Soriano, Olga. 1989. Rección y Ligamiento en Español: Aspectos Del Parámetro Del Sujeto Nulo. Doctoral Thesis, Universidad Autónoma de Madrid, Madrid, Spain. [Google Scholar]

- Fernández Soriano, Olga. 1993. Los Pronombres Átonos. Madrid: Taurus Universitaria. [Google Scholar]

- Fernández Soriano, Olga. 2016. Clíticos. In Enciclopedia de Lingüística Hispánica. Edited by Javier Gutiérrez-Rexach. New York: Routledge, pp. 423–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- García-Tejada, Aída, Alejandro Cuza, and Eduardo Gerardo Lustres Alonso. 2021. The production and comprehension of Spanish se use in L2 and Heritage Spanish. Second Language Research 39: 301–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Granfeldt, Jonas. 2014. Development of Object Clitics in Child L2 French: A Comparison of Developmental Sequences in Different Modes of Acquisition. In Acquisition of French as a Second Language: New Developmental Perspectives. Edited by Christina Lindqvist and Camilla Bardel. Amsterdam: John Benjamins, pp. 143–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grevisse, Maurice, and André Goose. 1995. Nouvelle Grammaire Du Français. Brussels: De Boeck-Duculot. [Google Scholar]

- Hakuta, Kenji. 2009. Bilingualism. In Encyclopedia of Neuroscience. Edited by Larry R. Squire. Oxford: Oxford Academic, pp. 173–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Halpern, Aaron L. 1998. Clitics. In The Handbook of Morphology. Edited by Andrew Spencer and Arnold M. Zwicky. Malden: Blackwell, pp. 101–22. [Google Scholar]

- Iranzo, Vicente. 2022. The Effect of Task Modality in Heritage Bilingualism Research. Revista de Lingüística y Lenguas Aplicadas 17: 59–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lohndal, Terje, Jason Rothman, Tanja Kupisch, and Marit Westergaard. 2019. Heritage language acquisition: What it reveals and why it is important for formal linguistic theories. Language and Linguistics Compass 13: e12357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- López Otero, Julio César, Alejandro Cuza, and Jian Jiao. 2023a. Object Clitic Use and Intuition in the Spanish of Heritage Speakers From Brazil. Second Language Research 39: 161–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- López Otero, Julio César, Esther Hur, and Michele Goldin. 2023b. Syntactic optionality in heritage Spanish: How patterns of exposure and use affect clitic climbing. International Journal of Bilingualism 28: 531–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martín Gómez, Antonio. 2022. The Effects of Age and Experience With Input in the Acquisition of Clitic Climbing in Heritage and L2 Spanish. International Journal of Bilingualism 27: 432–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meisel, J.M. 2009. Second Language Acquisition in Early Childhood. Zeitschrift für Sprachwissenschaft 28: 5–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mendikoetxea, Amaya. 1999. Construcciones con se. Medias, Pasivas e Impersonales. In Gramática de la Lengua Española. Edited by Ignacio Bosque and Violeta Demonte. Madrid: Espasa-Calpe. [Google Scholar]

- Montrul, Silvina. 1999. Causative Errors With Unaccusative Verbs in L2 Spanish. Second Language Research 5: 191–217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Montrul, Silvina. 2010. How similar are adult second language learners and Spanish heritage speakers? Spanish clitics and word order. Applied Psycholinguistics 31: 167–207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Montrul, Silvina. 2012. Is the heritage language like a second language? EUROSLA Yearbook 12: 1–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Montrul, Silvina. 2016. The Acquisition of Heritage Languages. Cambridge, MA: Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Montrul, Silvina. 2020. How Learning Context Shapes Heritage and Second Language Acquisition. In The Handbook of Informal Language Learning. Edited by Mark Dressman and Randall William Sadler. Hoboken: Wiley-Blackwell, pp. 57–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Montrul, Silvina. 2023. Doing Romance Linguistics: A Multilingual Acquisition Perspective. Isogloss. Open Journal of Romance Linguistics 9: 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Montrul, Silvina, Rebecca Foote, and Silvia Perpiñán. 2008. Gender Agreement in Adult Second Language Learners and Spanish Heritage Speakers: The Effects of Age and Context of Acquisition. Language Learning 58: 503–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ordóñez, Francisco. 2012. Clitics in Spanish. In Handbook of Hispanic Linguistics. Edited by José Ignacio Hualde, Antxon Olarrea and Erin O’Rourke. Hoboken: Wiley-Blackwell, pp. 423–52. [Google Scholar]

- Pato, Enrique. 2022. El español como lengua comunitaria y lengua de herencia en Quebec. Lengua y Migración 14: 7–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pérez Arreaza, Laura. 2017. El Lenguaje de los Jóvenes Hispanos de la Ciudad de Montreal. Doctoral thesis, Université de Montréal, Montreal, QC, Canada. [Google Scholar]

- Pérez-Leroux, Ana Teresa, Alejandro Cuza, and Danielle Thomas. 2011. Clitic placement in Spanish-English bilingual children. Bilingualism: Language and Cognition 14: 221–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Polinsky, Maria. 2018. Heritage Languages and their Speakers. Cambridge, MA: Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Polinsky, Maria, and Gregory Scontras. 2020. Understanding heritage languages. Bilingualism: Language and Cognition 23: 4–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Potowski, Kim, and Sarah Shin. 2019. Heritage Language Instruction. In The Cambridge Handbook of Language Learning. Edited by John W. Schwieter and Alessandro Benati. Cambridge, MA: Cambridge University Press, pp. 673–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Real Academia Española, and Asociación de Academias de la Lengua Española (RAE-ASALE). 2009. Nueva Gramática de la Lengua Española. Madrid: Espasa. [Google Scholar]

- Rodriguez Mondoñedo, Miguel, William Snyder, and Koji Sugisak. 2005. Clitic-Climbing in Child Spanish and the Theory of Parameters. Online Proceedings Supplement of the 29th Boston University Conference on Language Development. pp. 1–7. Available online: https://www.bu.edu/bucld/files/2011/05/29-Rodriguez-MondonedoBUCLD2004.pdf (accessed on 15 November 2024).

- Rothman, Jason. 2009. Understanding the Nature and Outcomes of Early Bilingualism: Romance Languages as Heritage Languages. International Journal of Bilingualism 13: 155–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scontras, Gregory, Zuzanna Fuchs, and Maria Polinsky. 2015. Heritage Language and Linguistic Theory. Frontiers in Psychology 6: 155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sequeros-Valle, Jose, Bradley Hoot, and Jennifer Cabrelli. 2020. Clitic-Doubled Left Dislocation in Heritage Spanish: Judgment versus Production Data. Languages 5: 47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Teomiro, Ismael I. 2017. Pronominal Verbs across European Languages: What Spanish Alternating Pronominal Verbs Reveal. In Contrastive Studies in Verbal Valency, 2nd ed. Edited by Lars Hellan, Andrej Malchukov and Michela Cennamo. Amsterdam: John Benjamins, vol. 3, pp. 375–406. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thomas, Danielle L. Thomopoulos. 2012. Grammatical Optionality and Variability in Bilingualism: How Spanish-English Bilinguals Limit Clitic-Climbing. Doctoral thesis, University of Toronto, Toronto, ON, Canada. [Google Scholar]

- Tremblay, Annie. 2006. On the Second Language Acquisition of Spanish Reflexive Passives and Reflexive Impersonals by French- And English-Speaking Adults. Second Language Research 22: 30–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Valdés, Guadalupe. 2000. Introduction. In Spanish for Native Speakers: AATSP Professional Development Series Handbook for Teachers K–16. Edited by Lynn A. Sandstedt. Fort Worth: Harcourt College, vol. 1, pp. 1–20. [Google Scholar]

- White, Lydia, Elena Valenzuela, Martyna Kozlowska-MacGregor, and Yan-Kit Ingrid Leung. 2004. Gender and number agreement in nonnative Spanish. Applied Psycholinguistics 25: 105–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wiese, Heike, Artemis Alexiadou, Shanley Allen, Oliver Bunk, Natalia Gagarina, Kateryna Iefremenko, Maria Martynova, Tatiana Pashkova, Vicky Rizou, Christoph Schroeder, and et al. 2022. Heritage Speakers as Part of the Native Language Continuum. Frontiers in Psychology 12: 717973. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zagona, Karen. 2002. The Syntax of Spanish. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Zwicky, Arnold. 1977. On Clitics. Bloomington: Indiana University Linguistics Club. [Google Scholar]

| Code | Age | AofB | Country | L1 | Heritage Type | Gender | Score DELE |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| SIM001 | 22 | 0 | Argentina | SP/FR | SIMULTANEOUS | F | 46 |

| SIM002 | 21 | 0 | Chile | SP/FR | SIMULTANEOUS | M | 42 |

| SIM003 | 25 | 0 | Mexico | SP/FR | SIMULTANEOUS | F | 43 |

| SIM004 | 22 | 0 | Mexico | SP/FR | SIMULTANEOUS | M | 45 |

| SEC001 | 26 | 4 | Mexico | SP | SEQUENTIAL | M | 40 |

| SEC002 | 18 | 6 | Colombia | SP | SEQUENTIAL | F | 43 |

| SEC003 | 20 | 4 | Mexico | SP | SEQUENTIAL | F | 45 |

| SEC004 | 23 | 5 | Mexico | SP | SEQUENTIAL | F | 45 |

| SEC005 | 21 | 5 | Mexico | SP | SEQUENTIAL | F | 48 |

| SEC006 | 24 | 6 | Chile | SP | SEQUENTIAL | M | 42 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Burdeus-Domingo, N.; Alba de la Fuente, A.; Teomiro, I.I. Heritage Spanish in Montreal: An Analysis of Clitics in Spontaneous Production Data. Languages 2024, 9, 355. https://doi.org/10.3390/languages9110355

Burdeus-Domingo N, Alba de la Fuente A, Teomiro II. Heritage Spanish in Montreal: An Analysis of Clitics in Spontaneous Production Data. Languages. 2024; 9(11):355. https://doi.org/10.3390/languages9110355

Chicago/Turabian StyleBurdeus-Domingo, Noelia, Anahí Alba de la Fuente, and Ismael I. Teomiro. 2024. "Heritage Spanish in Montreal: An Analysis of Clitics in Spontaneous Production Data" Languages 9, no. 11: 355. https://doi.org/10.3390/languages9110355

APA StyleBurdeus-Domingo, N., Alba de la Fuente, A., & Teomiro, I. I. (2024). Heritage Spanish in Montreal: An Analysis of Clitics in Spontaneous Production Data. Languages, 9(11), 355. https://doi.org/10.3390/languages9110355