Abstract

Three distinct anaphoric functions and one deictic function are, with fair confidence, associated with the Italian Pluperfect in the existing literature. In recent studies, it has been hypothesized that the Italian Pluperfect may also have an aoristic use. The present study attempts to assess the semantics of the Italian Pluperfect, by a corpus-based methodology. It will be shown that the data do not support the hypothesis of an aoristic use of the Pluperfect: rather, they suggest the need to extend the analysis of the Pluperfect’s semantics to domains other than tense and aspect. It will be argued that (inter)subjectification may have a key role in describing the layered semantics of the Italian Pluperfect, especially concerning its possible modal-evidential developments.

1. Introduction

The Italian Pluperfect displays a rather prototypical semantic core, with four distinct temporal–aspectual functions that have been identified by previous research: past-in-the-past; perfect-in-the-past; reversed result; and past temporal frame (Squartini 1999). In recent studies (Bertinetto 2003, 2014; Bertinetto and Squartini 1996; Scarpel 2017), it has also been hypothesized, albeit not specifically dealt with, that the Pluperfect may have an additional aoristic use in spoken Northern Italian. This paper aimed to assess the existence of such a use by analyzing Pluperfect occurrences in ParlaTO (Cerruti and Ballarè 2020), a corpus of spontaneous speech collected in Turin between 2018 and 2020. It will be shown that the data did not support the hypothesis of an aoristic use, but that they suggested that the Italian Pluperfect was developing secondary semantic values that could be explained by taking (inter)subjectification1 paths Traugott (2003, 2010) of grammaticalization into account.

The relationship between grammaticalization and (inter)subjectification has been extensively discussed by Traugott (2010). Having once defined grammaticalization as “[t]he change whereby lexical items and constructions come in certain linguistic contexts to serve grammatical functions, and once grammaticalized, continue to develop new grammatical functions” (Hopper and Traugott 2003), Traugott (2010) states that subjectification is likely to occur in grammaticalization “presumably because grammaticalization by definition involves recruitment of items to mark the speaker’s perspective on [a series of] factors”, among which are tense (“how the proposition (ideational expression) is related to speech time or to the temporality of another proposition”) and aspect (“whether the situation is perspectivized as continuing or not”), i.e., the categories that the present study is mostly concerned with, but also modality (“whether the situation is relativized to the speaker’s beliefs”) and discourse markers (“how utterances are connected to each other”), i.e., those categories that are known to be mostly involved in the Pluperfect’s development of secondary meanings (Plungian and van der Auwera 2006).

In what follows, it will be shown how tense, aspect and modality intertwine in defining the Pluperfect’s semantics. Concerning modality, it will be argued in Section 3 and Section 4 that possible Pluperfect developments include modal-evidential values, for the analysis of which the interplay of subjective and intersubjective values may be especially relevant.

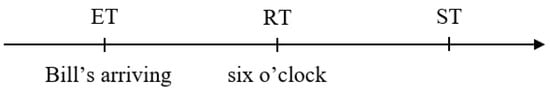

As outlined in the existing literature, the prototypical meaning of the Pluperfect is locating an Event (E) prior to a Reference Time (RT), at which the resulting state of E holds, and which is, in turn, in the past, with respect to the Speech Time (ST), as in:

- (1)

- Bill had arrived at six o’clock (Comrie 1976)

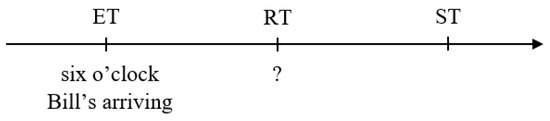

Nevertheless, as Comrie (1976) explains, Figure 1 accounts for just one of the possible readings of the sentence Bill had arrived at six o’clock. It could also be interpreted that Bill arrived precisely at six o’clock, before an unspecified RT.

Figure 1.

Perfect-in-the-past reading.

In the case of Figure 1, the event encoded by the Pluperfect (Bill’s arrival) is related to the state of affairs at six o’clock (Bill still being there), and Comrie (1976) therefore dubs this reading as perfect-in-the-past. In the case of Figure 2, the event encoded by the Pluperfect (Bill’s arrival) is understood to precede another (unknown) past event, but it is not related to it, and Comrie (1976) therefore dubs this reading as past-in-the-past.

Figure 2.

Past-in-the-past reading.

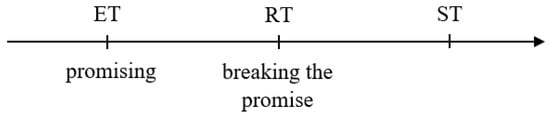

Beyond recognizing both these functions as pertaining to the semantics of the Italian Pluperfect, Squartini (1999) identifies two additional functions that the Italian Pluperfect may have, i.e., reversed result and past temporal frame. The reversed result function emphasizes that the result of the event encoded by the Pluperfect is no longer valid.

- (2)

- Me lo aveva promesso, ma adesso fa finta di non ricordarsene (Squartini 1999)‘(S)He had promised me, but now (s)he acts as if (s)he didn’t’

Given that the event encoded by the Pluperfect is related to the (reversed) state of affairs that holds at a later time, the reversed result function can be interpreted as a subcategory of the perfect-in-the-past function (Squartini 1999), as depicted in Figure 3.

Figure 3.

Reversed result reading.

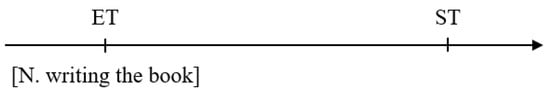

On the other hand, the past temporal frame function stresses the idea that the event encoded by the Pluperfect belongs to a closed temporal section that is grounded in the past.

- (3)

- Su questo argomento tanti anni fa N. ci aveva scritto un libro (Squartini 1999)‘N. wrote a book on this many years ago’

This is the only function, amongst the four functions Squartini (1999) associates with the Italian Pluperfect, that is deictic rather than anaphoric, i.e., its representation does not involve an RT. This distinguishes the past temporal frame function from the past-in-the-past function, in the sense that, whereas a past-in-the-past Pluperfect places the event in the past with respect to an RT, a past-temporal-frame Pluperfect places the event in the past with respect to the ST directly, with no relationship of anteriority being identifiable (see Figure 4).

Figure 4.

Past temporal frame reading.

In recent studies (Bertinetto 2003, 2014; Bertinetto and Squartini 1996; Scarpel 2017), it has been hypothesized that the Pluperfect can have an aoristic (i.e., deictic) use in spoken Northern Italian. It is important to note that while being deictic, the past temporal frame function cannot be described as aoristic, as it does not concern past events in general, but rather a smaller number of cases, i.e., events whose non-relevance at the ST is stressed2. On the other hand, an alleged aoristic Pluperfect should be able to potentially encode all cases of perfectivity in the past (except for the Perfect type).

Undoubtedly, the two ‘new’ functions identified by Squartini (1999)—reversed result and past temporal frame—have a strong subjective component, given that they encode the speaker’s perspective on the present (ir)relevance of past events. Furthermore, the past temporal frame function can also be understood as subjective, in that deictic grammatical functions “localize the linguistic entity they apply to with respect to the coordinates of the speaker” (Diewald 2011). It will be shown in Section 4 that additional semantic values arising from that data, while not always closely related one to the other, can all be subsumed under the category of (inter)subjectivity.

2. Materials and Methods

The research was carried out on ParlaTO3 (Cerruti and Ballarè 2020), a corpus of spontaneous speech collected through semi-structured interviews in Turin between 2018 and 2020. ParlaTO is designed to account for diastratic variation in the Italian spoken in Turin: it is balanced for the speaker’s age (16–29, 30–59 and 60+ years old), and provides a large set of additional metadata (Cerruti and Ballarè 2020). However, as the bibliography did not suggest that the aoristic use of the Pluperfect was related to a particular diastratic variety, the corpus was queried in its entirety as being simply representative of a variety of Northern Italian. One additional aspect of ParlaTO to consider when discussing the results of the present study is that the interviewees were often encouraged to talk about the past or to share memories: as a result, the corpus presented a high number of contexts relating to personal past experiences.

As the ParlaTO corpus was not POS tagged, the following query was used to extract Pluperfect occurrences:

[word = ”avev.*|er.*”][word = ”.*at.?|.*ut.?|.*it.?|fatto|detto|visto|messo|preso”]

Given that the Italian Pluperfect is formed with the Imperfect of the auxiliary verb and the Past Participle of the lexical verb, the query searched for the Imperfect of one of the possible auxiliary verbs (avere ‘to have’ or essere ‘to be’) followed either by a word ending with regular Past Participle desinences or by one of the most frequent irregular Past Participles (fatto ‘done’, detto ‘said’, visto ‘seen’, messo ‘put’, preso ‘taken’) according to the frequency list of the LIP corpus (De Mauro et al. 1993).

The query, run on 12 April 2021, produced 600 results: given the length of the analysis, it was decided to limit it to the first 300 results, 245 of which were actual Pluperfect occurrences.

3. Results

3.1. Past-in-the-Past

The Pluperfects classified as instances of past-in-the-past numbered 145 (out of a total of 245). The clearest examples displayed adverbial modifiers (underlined in the following example) that clarified the deictic/anaphoric collocation of the events referred to:

- (4)

- TOI052: e quindi stavo facendo fareTOI052: ehmTOI052: dei lavoretti per pasqua e pasquettaTOI051: siTOI052: e invece una volta prima gli avevo fatto [113] fare delle corniciTOR007: che cariniTOI052: e dei quadretti cose cosi’ e poi avevamo fatto [114] proprio la mostra eh ce’TOI052: and so I was having them makeTOI052: uhmTOI052: Easter craftsTOI051: yesTOI052: and one time before I had had [113] them make framesTOR007: how cuteTOI052: and small paintings things like that and then we had done [114] a proper exhibit I mean4

In (4), TOI052 was speaking about her volunteering experiences by showing pictures. The modifier una volta prima ‘one time before’ leaves no doubt about the fact that Pluperfects [113] and [114] preceded the event spoken about in the first lines (i.e., the making of Easter crafts).

In other cases, the anteriority of the Pluperfect was recognizable only because of world knowledge, by which we knew how certain events usually preceded others:

- (5)

- TOR004: si’ ma sai che avevo sentito [22] di uno che aveva fatto [23] causa a starbucks perche’ non aveva scritto che il bicchiere poteva essere bollente quello si era bruciato [24] la manoTOR004: yeah but do you know that I heard (lit. had heard [22]) about someone who had sued [23] Starbucks because they didn’t write (lit. hadn’t written) that the cup could’ve been hot that one had burned [24] his hand

In (5), the only possible collocation of the events was: person burns his hand > person sues Starbucks > TOR004 hears about this. While [23] and [24] were therefore past-in-the-past Pluperfects, [22] seemed to be deictic, and was classified as a past-temporal-frame Pluperfect. In fact, (5) also contained one additional Pluperfect (non aveva scritto ’they hadn’t written’) that was not italicized in the text and was not associated with a number: this was because, being formed with an irregular past participle, it could not be identified by the query. Although only the Pluperfects identified by the query were included in the counts, it could still be observed that non aveva scritto ’they hadn’t written’ in turn displayed anteriority with respect to [24], and was therefore also classified as a past-in-the-past Pluperfect.

For other cases, the anteriority value of the Pluperfect was unquestionable, yet it was not the most salient, as illustrated in example (6):

- (6)

- TOI008: san giovanni che io ho trovato incredibile perche’ eh mhTOI008: appunto io abito vicino al po quindi ci metto cinque minuti ad andare li’TOR001: mh mhTOI008: e tutti gli anni sempre andato tantissima gente sempre strapieno quest’anno eh mh ho detto non vado nemmeno perche’ ci avevano messo [64] i tornelli ilTOR001: no certoTOI008: tutti i vari controlli e ho detto non ci vado nemmenoTOI008: San Giovanni5 which I found incredible because uh uhmTOI008: indeed I live close to the Po so I’m there in five minutesTOR001: uhm uhmTOI008: and every year I always went lots of people always super full this year uh uhm I said I’m not even going because they had put [64] the turnstiles theTOR001: no of courseTOI008: all the controls and I said I’m not even going

Pluperfect [64], for instance, seemed to emphasize the cause/effect relationship between the placement of the turnstiles and the decision not to attend the event, rather than the temporal anteriority of the former with respect to the latter. Nevertheless, in all such cases where an anteriority relationship could still be identified, the Pluperfects under scrutiny were classified as past-in-the-past: this may also explain the numerical prevalence of the Pluperfects categorized as such.

3.2. Perfect-in-the-Past

The Pluperfects classified as instances of perfect-in-the-past numbered 28, which was likely an undervaluation of the actual occurrence of this category, since the query could only identify Pluperfects if no word(s) occurred between the auxiliary and the lexical verb, which meant that Pluperfects combined with the adverb già ‘already’ (highly compatible with a perfect reading)—as in avevo già mangiato ‘I had already eaten’—were excluded from the analysis. Nevertheless, the potential compatibility of the Pluperfects under scrutiny with the adverb già ‘already’ was an important clue to guiding their classification as perfect-in-the-past, as exemplified in (7).

- (7)

- TOI065: eravamo frutto di una mhTOI065: di una riformaTOR001: mh mhTOI065: e non potevamo passare al secondo biennio era ancora quadriennaleTOI065: se non avevamo dato [60] quattro obbligatori del primoTOR001: okayTOI065: ma ehTOI065: io ce n’era ne avevo dati [61] due gli altri due erano enormiTOI065: we were the result of a uhmTOI065: of a reformTOR001: uhm uhmTOI065: and we couldn’t move to the third and fourth years it was still four years longTOI065: if we hadn’t passed [60] four mandatory [exams] of the first two yearsTOR001: okayTOI065: but uhTOI065: I there was I had passed [61] two the other two were huge

It was not only Pluperfects [60] and [61] that were undoubtedly compatible with the adverb già ‘already’6—given that the students needed to have already passed four exams to continue their course of study—but also the resultative value of the Pluperfect, which was evident from the fact that having (not) passed four exams was extremely relevant at the RT (i.e., the start of the second half of the course of study).

In other cases, the compatibility of the Pluperfect with the adverb già ‘already’, seemed to depend on matters of interpretation, as in the following case:

- (8)

- TOI077: le parole testuali aveva fattoTOR004: fai occhioTOI077: han fatto effetto evidentementeTOR004: quanto te le sei preparateTOI077: no niente perche’ non e’TOI077: non avevo intenzioneTOR004: non era neache previstoTOI076: non volevaTOI077: si’ avevo capito [31] che x vabbe’ questa7TOI077: vuol8 che io x che la accompagnoTOI077: he said those literal wordsTOR004: watch outTOI077: clearly they workedTOR004: how much did you prepare themTOI077: no nothing because it’s notTOI077: I had no intentionTOR004: it wasn’t even plannedTOI076: he didn’t wantTOI077: yes I had understood [31] that well this oneTOI077: she wants me to give her a ride

In the part of the conversation preceding (8), TOI076 talked about when TOI077 (who was her boss at the time) finally agreed to give her a ride, and confessed to reciprocating her feelings. As its object was not expressed, Pluperfect [31] could have had two readings: either TOI077 already understood that TOI076 wished to get a ride from him because she had feelings for him (perfect-in-the-past, compatible with già ‘already’), or TOI077 initially (mis)understood that TOI076 simply had a genuine need for a ride (reversed result)9. In such cases, reading the entire conversation was essential to determining which interpretation was the most likely (e.g., the perfect-in-the-past reading for (8), as confirmed by the audio track, given that TOI077 speaks with a mocking tone).

There were also cases where clues others than compatibility with già ‘already’ had to be taken into account:

- (9)

- TOI051: perche’ l l la sua mamma era podalica e’ stato un parto bruttissimoTOR007: mh anch’io sono nata podalicaTOI051: ehTOI051: mahTOR007: eh ha sofferto molto mia mammaTOI051: ma io da una parte era solo un un anno e mezzo che avevo avuto [118] il primo figlioTOI052: mh mhTOI051: e allora le ossa erano ancoraTOI051: ehTOR007: si’ si’TOI051: abbastanza aperteTOI051: because her mom was podalic it was a terrible deliveryTOR007: uhm I was born podalic tooTOI051: uhmTOI051: bahTOR007: uhm she suffered a lot my momTOI051: well on one hand for me it had been just a year and a half since I had had [118] my first childTOI052: uhm uhmTOI051: and so the bones were stillTOI051: uhmTOR007: yes yesTOI051: pretty open

Pluperfect [118] was not really compatible with già ‘already’; nevertheless, the expression era solo un anno e mezzo che ’it had been just a year and a half since’ measured the temporal distance of Pluperfect [118] from the RT, and therefore suggested a perfect reading.

3.3. Reversed Result

The Pluperfects classified as instances of reversed result numbered 16. In many cases, these Pluperfects conveyed exactly the opposite meaning of an Italian Present Perfect10.

- (10)

- TOI003: ha perso tantissime cose torinoTOR001: mhTOI003: se uno pensaTOI002: no pero’ si e’ arricchita parecchio con le olimpiadi a pa guarda prima non c’eraTOI003: a partire da esperimentaTOI003: a partire da un macello di cose che io mi ricordo quando andavo a scuola potevi fareTOI003: un casi era diventata [187] la citta’ delle delle mhTOI002: mado’ ma prima tu vede mado’ ma tu prima vedevi turismo a torinoTOI003: del libro e poi l’ha spostata a milanoTOI003: Torino lost a lot of thingsTOR001: uhmTOI003: if one thinksTOI002: no but it developed a lot with the Olympics look before there wasn’tTOI003: starting from EsperimentaTOI003: starting from a lot of things that I remember when I still went to school you could doTOI003: a lot it became (lit. had become [187]) the city of of uhmTOI002: God but before you saw God but before you saw tourism in TorinoTOI003: of books and then they moved it to Milano

In (10), not only did TOI003 explicitly provide a motivation for the results of the event (i.e., Turin becoming the city of books) being considered as reversed (the city of books was now Milan), but also Pluperfect [187] itself encoded this semantic. Had a Present Perfect replaced Pluperfect [187], it would likely have been inferred that Turin was still the city of books11.

While Pluperfect [187] (and most of the other reversed-result Pluperfects analyzed) displayed exactly the opposite semantic of a Perfect result (see Comrie (1976) for a description of types of Perfect, and Bertinetto (1986) for Italian), there were also instances of reversed-result Pluperfects functioning as the opposite of a Perfect of persistent situation:

- (11)

- TOI054: e quello mi aveva fatto [88] mi aveva un po’ pero’TOI054: poi mi e’ passatoTOI054: and that did (lit. had done [88]) me a little butTOI054: then it went away

TOI054 was referring to an alarming road trip that she had experienced, and likely meant to say that it scared her (mi aveva fatto paura ’it scared (lit. had scared) me’). While in (10) the Pluperfect reversed the result of the event, in (11) the Pluperfect reversed the state of affairs itself, given that it stopped taking place. In other words, Pluperfect [88]’s meaning could be understood as it scared me, but it doesn’t anymore, while the meaning of Pluperfect [187] was Turin became the city of books but it isn’t anymore, rather than *Turin became the city of books, but it doesn’t become anymore. This will be further discussed in Section 4.

In other cases where ’anti-Perfect’ semantics were not particularly evident, contextual and cotextual clues played an important role in guiding the classification of the Pluperfects. An example thereof is the following:

- (12)

- TOI077: ci hanno proposto il viaggio al cairo in pullman abbiam detto vabbe’ quando ci ricapitaTOR004: perche’ era organizzatoTOI077: si’TOR004: okayTOI076: e c avevano detto [44]TOI076: meno ore e invece poi alla fine siam stati sei ore in quelTOI077: si’TOI077: cinque sei oreTOI076: sei oreTOI077: they proposed us the trip to Cairo by bus we said well this won’t happen a second timeTOR004: because it was organizedTOI077: yesTOR004: okayTOI076: and they told (lit. had told [44]) usTOI076: less hours and instead then in the end we’ve stayed six hours in thatTOI077: yesTOI077: five six hoursTOI076: six hours

Given that receiving information about the flight’s length must have preceded the landing, Pluperfect [44] could be understood as having been a past-in-the-past. Nevertheless, as TOI076 clearly stated that the results of the event encoded Pluperfect [44] had been reversed (the information turned out to be wrong), it was classified as an instance of reversed result.

3.4. Past Temporal Frame

The Pluperfects classified as instances of past temporal frame numbered 63. It was not surprising that many past-temporal-frame Pluperfects occurred in contexts of remembering, and were often signaled as such by the speakers themselves:

- (13)

- TOR004: eh ma tortoli’ eh mizzeca e’ bellissimaTOR004: c’e’ la spiaggia del saraceno quello con la torre ti ricordi eravamo andati [48] anche insieme l’anno che sei venutaTOR004: uh but Tortolì uh my goodness is really beautifulTOR004: there is the Saraceno beach that with the tower do you remember we also went (lit. had gone [48]) together the year you came

By asking the addressee whether she remembered, TOR004 implicitly assigned the event encoded by Pluperfect [48] to a temporal frame (that of the memory) past and closed, further specified by the temporal indication l’anno che sei venuta ’the year you came’. It is worth clarifying that Pluperfect [48] was indeed deictic: even by analyzing a broader section of the conversation, it was not possible to retrieve any RT, and the sentence would also have been acceptable if a Present Perfect (in its aoristic function) had replaced Pluperfect [48] (siamo andati ‘we went’, lit. ‘we have gone’).

In other cases, the belonging of the event encoded by the Pluperfect to a past temporal frame could be signaled by expressions with the noun volta ‘time’ (e.g., la volta ‘the time (that)’, la prima volta ‘the first time (that)’, etc.) or simply inferable from context:

- (14)

- TOR004: avevi degli amici nel paese dove viveviTOI054: no io tantissimi amiciTOI054: sempre avuto tante c tante conoscenze ma tanti amici anche tanta gente che le piaceva stare con meTOR004: e ma organizzavate delle feste facevate delle coseTOI054: perche’ comunqueTOI054: si’ anche a casa mio padre per i miei sedices e il mio sedicesimo annoTOR004: compleannoTOI054: compleannoTOI054: e mhTOI054: mhTOI054: sopra il mio al nostro alloggio dove avevamo la casaTOI054: e avev c’era una mansardaTOI054: to tutta unica e luiTOI054: e per un po’ di tempo ha diviso tutte ha fatte delle stanze poi aveva messo [80] la moquette avevamo messo [81] addirittura la tappezzeriaTOI054: e io per il mio sedicesimo annoTOI054: avevo tutto e poi mi aveva comprato [82] lo stereoTOI054: e avevam fatto [83] la festaTOR004: did you have friends in the town you lived inTOI054: no me lots of friendsTOI054: I always had lots lots of connections but lots of friends too lots of people that liked being with meTOR004: well but did you organize parties do thingsTOI054: because howeverTOI054: yeah also at home my dad for my 16th for my 16th yearTOR004: birthdayTOI054: birthdayTOI054: and uhmTOI054: uhmTOI054: over mine our flat were we had the houseTOI054: and we had there was an atticTOI054: all open and heTOI054: for a while he divided all he made rooms then he put (lit. had put [80]) the carpet we even put (lit. had put [81]) the wallpaperTOI054: and I for my 16th yearTOI054: I had it all and then he bought (lit. had bought [82]) me the stereoTOI054: and we made (lit. had made [83]) the party

While the action of remembering was not mentioned in (14), it is clear that TOR004’s questions encouraged TOI054 to share memories. The adverbs poi (‘then’) could be interpreted as having had a listing function rather than a temporal one: indeed, while Pluperfects [80]–[82] necessarily preceded Pluperfect [83], the focus did not seem to be on the temporal collocation of each event with respect to the others, but rather on the totality of the elements that made up the memory of the party.

- (15)

- TOR004: e non sei mai andata all’universita’TOI054: noTOI054: si’TOI054: scherzando andavoTOR004: ahTOR004: in che sensoTOI054: del tipoTOI054: che andavo a scuola a ragioneriaTOR004: ehTOI054: a cirie’TOI054: prendevo il treno con la mia amicaTOR004: okayTOI054: e andavamo a torinoTOI054: e poi andavamo all’universita’TOI054: ed e’ successo d ascoltare anche delle lezioniTOR004: delle lezioni di cosaTOI054: e avevamo ascoltato [79] delle lezioni di biologiaTOR004: ahTOI054: e poi prendevamo il quaderno con degli appunti facevamoTOI054: facevamo le le universitarieTOR004: and you never went to universityTOI054: noTOI054: yesTOI054: I went as a jokeTOR004: ohTOR004: what do you meanTOI054: likeTOI054: I went to high schoolTOR004: uhmTOI054: in CirièTOI054: I took the train with my friendTOR004: okayTOI054: and we went to TorinoTOI054: and then we went to the universityTOI054: and it happened that we listened lessons tooTOR004: what lessonsTOI054: well we listened (lit. had listened [79]) biology lessonsTOR004: ohTOI054: and we took the notebook with notes we playedTOI054: we played university students

The event encoded by Pluperfect [79] might be considered a memory too; nevertheless, the main reason why it belongs to a time frame in the past, and closed, is that, as it appears by reading a broader section of the conversation, it did not have any consequence on TOI054’s life (e.g., she did not enroll in a biology course afterwards). Interestingly, had a Present Perfect been used instead, it would have received an experiential interpretation, i.e., it would have been considered to indicate that the situation, of having heard biology lectures, occurred at least once during a period of time extending to the present (Comrie 1976). While there is no doubt that the situation did indeed occur, the use of the Pluperfect seems to suggest (in contrast to the Present Perfect) that it was nonetheless of little significance to the speaker. This will be further discussed in Section 4. In more than one case, the events encoded by the past-temporal-frame Pluperfects displayed quite specific characteristics.

- (16)

- TOR002: pensa che dove c’e’ adesso l’areoporto di caselle mio nonno aveva un terreno che gli hanno espropriatoTOI119: si’TOI119: ehTOR002: quando han costruito l’areoporto nuovoTOI118: mhTOI119: ah si’ ma poi era caduto [17] anche l’aereo la’ nelle caseTOI118: caselleTOR002: eh si’TOR002: think that where there now is the Caselle airport my grandpa had land that they expropriatedTOI119: yesTOI119: uhmTOR002: when they built the new airportTOI118: uhmTOI119: oh well but then even the plan fell (lit. had fallen [17]) there in the housesTOI118: CaselleTOR002: yeah

In (16), the event encoded by Pluperfect [50] had two characteristics: on the one hand, as suggested by the preceding ah sì ma poi ’oh well but then’, it discursively appeared as a digression. On the other hand, given that TOI118 did not comment on the matter, and TOR002 simply answered with eh sì ’yeah’, it was also shared knowledge between the speakers.

- (17)

- TOI077: minchia l’ho portata in camperTOI077: gia’ cheTOI077: saliva in camperTOI077: poi siamo arrivati a sto posto li’TOR004: non eraTOI076: eh eh la racconto ioTOR004: non eri convintaTOI076: noTOI077: ma per niente aveva paura voleva andarsene viaTOI076: ah gia’ e’ vero avevo chiamato [46] mia mammaTOI076: mentre tu eri sceso a parlareTOI077: shit I brought her campingTOI077: alreadyTOI077: getting on the camperTOI077: then we arrived in that place thereTOR004: it wasn’tTOI076: uh uh I tell itTOR004: you weren’t convincedTOI076: noTOI077: not at all she was scared she wanted to leaveTOI076: oh right that’s true I called (lit. had called [46]) my momTOI076: while you had gotten off to talk

The event encoded by Pluperfect [46] seemed to come with a sense of surprise, on the part of the speaker, in recalling the event itself. In Section 4, it will be argued that these findings should be considered by further research addressing the hypothesis of the Pluperfect having additional functions to those analyzed in this paper.

Not all past-temporal-frame Pluperfects belong to a remote past, as one might assume, based on the previous examples (remember that the corpus was unbalanced in favor of remote contexts, as mentioned in Section 2):

- (18)

- TOI051: delle maschere ho fatto tanti di quei vestitiTOI052: treTOR007: anche mia nonna ugualeTOI052: bellissimiTOI052: bellisimi proprioTOI052: davveroTOI052: ancheTOI052: quello che avevi fatto [120] vedere l’altro giorno di quando mamma ha fatto laTOI051: ah la danzatriceTOI051: some masks I made so many dressesTOI052: threeTOR007: also my grandma the sameTOI052: very beautifulTOI052: very beautiful reallyTOI052: for realTOI052: alsoTOI052: the one that you showed (lit. had showed [120]) the other day of when mom wasTOI051: oh the dancer

Indeed, the temporal location of Pluperfect [120] was l’altro giorno ’the other day’, i.e., quite recently in the past. This will be further discussed in Section 4.

3.5. Left-Out Occurrences

Six Pluperfects could not be assigned to either of the four functions: in two of these cases, the events encoded by the Pluperfects seemed to be digressions in discourse:

- (19)

- TOR004: e com’e’ che siete finiti la’TOI054: non lo soTOI054: da questa superstrada che dava la cartinaTOI054: oltretutto ero andata [87] con aldo ehTOR004: pensa teTOI054: e quindi lui era uno cheTOI054: sapeva girare nel senso guardare la cartina non era unTOI054: uno che si perdeva eccoTOR004: and how is it that you ended up thereTOI054: I don’t knowTOI054: from this highway the map saidTOI054: besides I went (lit. had gone [87]) with Aldo uhTOR004: just thinkTOI054: and so he was one thatTOI054: he knew how to travel I mean look at the map he wasn’t aTOI054: one that got lost okay

Note that (19) is from the same conversation as (11). By reading the whole conversation, Pluperfect [87] appears to be deictic, and (19) seems to be a past-temporal-frame prototypical context (TOI054 was recalling the past experience of a road trip). Nevertheless, no other Pluperfects were used in recalling the trip. ’Having gone with Aldo’ does not seem to be a more past-bound element than the others, but rather accessory information, added as it came to TOI054’s mind—not different, in this aspect, from Pluperfect [50] in (16) (the latter, however, still displayed past temporal frame semantics, and had therefore been categorized as such, as explained in the previous section).

On the other hand, the other four left-out occurrences displayed a greater difference from the other Pluperfects analyzed so far (see above), in that they also seemed to be deictic, but did not appear to be digressions, and not even the context they belonged to was past temporal frame.

- (20)

- TOI076: perche’ abbiam fatto ho fatto diverse lampade o anche lampadariTOI076: eh queste si’ ci mi piacciono mi piacciono tantoTOR004: eh come fate per fare i lampada cioe’ dovete farvi tutto lo studio deiTOR004: dei caviTOI076: si’TOI076: so fare collegamenti elettrici io ehTOI077: eh quello che gli avevo insegnato [27] ioTOI076: ho imparato daTOI076: da giulio anche eh dal mio suoceroTOI077: si’ anche mio padreTOI076: because we made I made many lamps or also chandeliersTOI076: uh these yes we I like I like these a lotTOR004: uhm how do you do to make chandeliers I mean you have to study allTOR004: the cablesTOI076: yesTOI076: I know how to make electrical connections duhTOI077: well that that I taught (lit. had taught [27]) herTOI076: I learnt fromTOI076: from Giulio also uhm from my father-in-lawTOI077: yes also from my father

It may have been the case that TOI077 was remembering the time he taught TOI076 how to make electrical connections, but this would not justify a past temporal reading of the event, given that its consequences were still extremely relevant (TOI076 knew how to make electrical connections). The relevance at the ST of the event encoded by the Pluperfect is perhaps more noticeable in (21), where TOI052 was showing TOI051 (her grandmother) videos that she had received:

- (21)

- TOI052: guarda nonna ti faccio vedereTOI052: ehTOI052: marcoTOI051: si’TOI052: la bimba e’ cresciuta guarda eh quiTOI051: uh uhTOI052: gli ha fatto una canzone sai che suona marcoTOI051: certo lo soTOI051: guarda guarda x com’e’ attentaTOI052: guarda qui bellaTOI051: guarda coTOI051: ma che caraTOI052: si’ son e’ bellissimaTOI052: ehTOI052: e invece giulia aveva mandato [125][…] (addressees don’t listen as they are still commenting on the video of the song)TOI052: e invece giuliaTOI052: ha mandatoTOI052: si sente il cuoricino di adele aspettaTOI052: look grandma I’ll show youTOI052: uhTOI052: MarcoTOI051: yesTOI052: the baby has grown look hereTOI051: uh uhTOI052: he wrote her a song you know that Marco playsTOI051: of course I knowTOI051: look look how she’s alertTOI052: look here prettyTOI051: look howTOI051: she’s so sweetTOI052: yes they she’s very beautifulTOI052: uhmTOI052: and Giulia send (lit. had sent [125]) instead[…] (addressees don’t listen as they are still commenting on the video of the song)TOI052: and Giulia insteadTOI052: has sentTOI052: you can hear Adele’s little heart wait

Clearly, the fact that Giulia had sent TOI052 a video was still relevant, given that the video was about to be played. It is interesting to note that when TOI052 repeated the information, she switched to a Present Perfect (ha mandato ’has sent’).

- (22)

- TOI052: e tra l’altro il nonno quandoTOI052: lui non c’e’ quando si fanno i compleanni pero’ se lo chiami la canzoncina te la canta sempreTOI051: no lTOI051: si’ si’ e’ veroTOI051: l lo canta anche per telefono ehTOI052: certo si’ infatti lo chiamiTOI051: eh perche’TOI052: quest’anno tra l’altro vabbe’ quest’anno ci siamo visti quindi alla fine non mi aveva chiamato [111]TOI051: si’ eravamo li’ ehTOI052: and by the way grandpaTOI052: he doesn’t come when we celebrate birthdays but if you call him he always sings you the songTOI051: noTOI051: yes yes it’s trueTOI051: he also sings it over the phone duhTOI052: of course yes you call him indeedTOI051: uhm becauseTOI052: this year by the way well this year we saw each other so in the end he didn’t call (lit. hadn’t called [111])TOI051: yes we were there uh

In (22), the temporal frame to which Pluperfect [111] belongs is undoubtedly still open, i.e., it includes the ST, as signaled by the time indication quest’anno ’this year’. The expression tra l’altro ’by the way’ could indeed suggest that the event encoded by Pluperfect [111] was a digression; nevertheless, it could also be interpreted as shared knowledge between the speakers, given that TOI051 (TOI052’s grandmother) confirmed that her husband (TOI052’s grandfather) and she were with TOI052 on her last birthday.

- (23)

- TOR002: io guido si chiama io guidoTOR001: bravoTOI012: bravissimoTOI013: si’TOI012: e’ veroTOR001: e’ iniziato molto pr perche’ io mi ricordo che quando ero venuta [227] qua a torino c’erano gia’ e a milano noTOR002: Io guido it’s called Io guidoTOR001: bravoTOI012: bravissimoTOI013: yesTOI012: it’s trueTOR001: it began very early because I remember that when I arrived (lit. had arrived [227]) here in Torino there were already but not in Milano

In (23), car sharing services were being discussed. Despite being deictic, Pluperfect [227] encoded an event belonging to a temporal frame still open, given that the adverb qua ’here’ suggests that TOR001 was still in Torino.

4. Discussion

The four temporal–aspectual functions described by Squartini (1999) (past-in-the-past, perfect-in-the-past, reversed result and past temporal frame) have proven to be indeed relevant for a description of spoken Italian, given that they managed to account for 239 of the 245 Pluperfect occurrences. The use of authentic language samples has allowed a further description of the aforementioned categories and of their prototypical context or context of use:

- the past-in-the-past function (145/245) is used to temporally organize events with respect to one other, i.e., to locate the event encoded by the Pluperfect prior to another past event (which can also be a proper consequence of the former). The temporal collocation of the events may be further specified by the presence of adverbial modifiers (e.g., una volta prima ‘one time before’).

- The perfect-in-the-past function (28/245) is used to highlight the relevance of the event encoded by the Pluperfect at a later past time. This reading is naturally compatible with the adverb già ‘already’, and with expressions measuring the temporal distance of the event encoded by the Pluperfect to the RT.

- The reversed result function (16/245) is used to stress that the results of the event encoded by the Pluperfect have been reversed at a later time in the past. This reading can often be confirmed by a following sentence describing the reversed situation that holds at the ST (eventually introduced by adverbs such as invece ‘instead’ or poi ‘then’).

- The past temporal frame function (63/245) is used to stress that the event encoded by the Pluperfect is past-bound. It is often used in contexts of remembering, and may co-occur with expressions with the noun volta ‘time’ (e.g., la volta ‘the time (that)’, la prima volta ‘the first time (that)’, etc.).

The reversed result and past temporal frame functions can be understood as instances of discontinuous past marking. Plungian and van der Auwera (2006) define the meaning of discontinuous past markers as “past with no present relevance” or “past and not present”, and explicitly state that the terms they use to distinguish these two subtypes (i.e., canceled result and framepast) are close to those employed by Squartini (1999) to refer to the Pluperfect’s two derived values. This suggests that the notion of discontinuity (Plungian and van der Auwera 2006) may be relevant for a description of the Italian verb system. Furthermore, it was shown in Section 3 that reversed-result Pluperfects (and past-temporal-frame Pluperfects, occasionally) can shape their meaning in opposition to the main kinds of Perfects (i.e., Perfect of result, Perfect of persistent situation and experiential Perfect). This suggests that discontinuity, while being considered purely temporal by Plungian and van der Auwera (2006), could be researched in the future as a double-faced notion. In fact, while the notion of past temporal frame can easily be interpreted as temporal, the reversed result notion seems to be closely related to aspect in its ‘anti-Perfect’ meaning.

Concerning the hypothesis of the existence of an aoristic use of the Pluperfect, the deictic Pluperfect occurrences that could not be classified as instances of the past temporal frame function (the only deictic function among those analyzed) were not only too small in number to prove the existence of an aoristic use, but also displayed different main connotations (i.e., discourse digression, shared knowledge) that also arose as secondary meanings amongst past-temporal-frame Pluperfects (in addition to surprise on behalf of the speaker). In fact, the typological literature has already highlighted that one of the most common derived uses of the Pluperfect is the marking of background information (e.g., digressions) (Plungian and van der Auwera 2006), and literature on Italian (Bertinetto 1986; Maiden and Robustelli 2007) has confirmed the existence of this use, albeit apparently considering it as arising from the original anaphoric meaning of the Pluperfect, which is considered to be preserved. On the other hand, according to Bermúdez (2011), the Castilian Pluperfect can be used as a marking of evidential distance, which includes shared access to the source of information (i.e., shared knowledge) and mirativity (i.e., surprise on behalf of the speaker). It is possible that a number of Pluperfects in the data encode new functions yet to be identified by exploring the domains of discourse and evidentiality, which have been subsumed under the past temporal frame category—probably also due to ParlaTO displaying a lot of past temporal frame contexts itself.

While further research is needed to identify the precise semantic scope of the Italian Pluperfect, its less prototypical functions (reversed result and past temporal frame), and the semantic values that arise in uncategorized data and/or in the past-temporal-frame Pluperfects, are all, in one way or another, based on the speaker’s perspective and/or on the speaker’s attention to the addressee. In principle, both reversed result and past temporal frame functions can be considered subjective in a proper semantic sense, as they both involve the speaker’s deictic center. In fact, although only the past temporal frame function is properly deictic, the reversed result function expresses a (reversed) resulting state that holds at ST—see (10), repeated in (24):

- (24)

- TOI003: ha perso tantissime cose torinoTOR001: mhTOI003: se uno pensaTOI002: no pero’ si e’ arricchita parecchio con le olimpiadi a pa guarda prima non c’eraTOI003: a partire da esperimentaTOI003: a partire da un macello di cose che io mi ricordo quando andavo a scuola potevi fareTOI003: un casi era diventata [187] la citta’ delle delle mhTOI002: mado’ ma prima tu vede mado’ ma tu prima vedevi turismo a torinoTOI003: del libro e poi l’ha spostata a milanoTOI003: Torino lost a lot of thingsTOR001: uhmTOI003: if one thinksTOI002: no but it developed a lot with the Olympics look before there wasn’tTOI003: starting from EsperimentaTOI003: starting from a lot of things that I remember when I still went to school you could doTOI003: a lot it became (lit. had become [187]) the city of of uhmTOI002: God but before you saw God but before you saw tourism in TorinoTOI003: of books and then they moved it to Milano

In (24) the reversed resulting state of the event encoded by Pluperfect [187] was relevant to the speaker’s deictic center: Turin was not the city of books at the ST. In addition to being deictic, past-temporal-frame Pluperfects often occur in digressions, as in (16), repeated in (25):

- (25)

- TOR002: pensa che dove c’e’ adesso l’areoporto di caselle mio nonno aveva un terreno che gli hanno espropriatoTOI119: si’TOI119: ehTOR002: quando han costruito l’areoporto nuovoTOI118: mhTOI119: ah si’ ma poi era caduto [17] anche l’aereo la’ nelle caseTOI118: caselleTOR002: eh si’TOR002: think that where there now is the Caselle airport my grandpa had land that they expropriatedTOI119: yesTOI119: uhmTOR002: when they built the new airportTOI118: uhmTOI119: oh well but then even the plan fell (lit. had fallen [17]) there in the housesTOI118: CaselleTOR002: yeah

In (25), the speaker’s perspective on the textual relevance of the event was at stake. Subjectivity was then involved, from at least two points of view: a more strictly semantic one and a textual one. The speaker’s perspective was also in focus in cases in which his own surprise was highlighted, as in (17), repeated in (26):

- (26)

- TOI077: minchia l’ho portata in camperTOI077: gia’ cheTOI077: saliva in camperTOI077: poi siamo arrivati a sto posto li’TOR004: non eraTOI076: eh eh la racconto ioTOR004: non eri convintaTOI076: noTOI077: ma per niente aveva paura voleva andarsene viaTOI076: ah gia’ e’ vero avevo chiamato [46] mia mammaTOI076: mentre tu eri sceso a parlareTOI077: shit I brought her campingTOI077: alreadyTOI077: getting on the camperTOI077: then we arrived in that place thereTOR004: it wasn’tTOI076: uh uh I tell itTOR004: you weren’t convincedTOI076: noTOI077: not at all she was scared she wanted to leaveTOI076: oh right that’s true I called (lit. had called [46]) my momTOI076: while you had gotten off to talk

On the other hand, the shared knowledge value that arose in (25) can be understood as intersubjective, given that it required the speaker’s attention to be conveyed towards the (alleged) knowledge of the addressee.

It appears that the notion of (inter)subjectification might be crucial in structuring a more integrated description of the less prototypical uses of the Italian Pluperfect, and in explaining its grammaticalization of new functions over time.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The KIParla corpus (of which ParlaTO is a module) is available at https://kiparla.it/, accessed on 12 April 2021.

Conflicts of Interest

The author declares no conflict of interest.

Notes

| 1 | Traugott (2003, 2010) uses the term (inter)subjectification to refer to the semanticization of subjectivity (the expression of the speaker’s perspective and attitudes) and intersubjectivity (the expression of the speaker’s attention to the self of the addressee). |

| 2 | This becomes particularly clear when one considers that a speaker of Northern Italian, referring to a deceased person, would not say è nato (lit. ’he has been born’, i.e., using a present perfect which, in the variety under analysis, also encodes an aorist aspect) but era nato (lit. ’he had been born’). |

| 3 | It is a module of the larger KIParla corpus (Mauri et al. 2019). |

| 4 | An effort has been made to provide translations as close as possible to the Italian texts, preserving the characteristics of the spoken language where possible. |

| 5 | The celebration of Turin’s patron saint, St. John, that usually consists of a firework display on the river Po. |

| 6 | The sentences concerned would look as follows:

|

| 7 | ’x’s stand for incomprehensible text. |

| 8 | The transcription displays vuoi (want.PRS.2.SG), but from listening to the audio track it appears that TOI077 says vuol (want.PRS.3.SG) instead. |

| 9 | One can imagine that the complete sentence resembled either avevo già capito che il passaggio era solo una scusa (‘I had already understood that the ride was just an excuse’) or avevo capito che le servisse davvero un passaggio (‘I had understood that she genuinely needed a ride’). |

| 10 | The original (Perfect) meaning of the Italian Present Perfect is being considered here, albeit it has come to encode an aoristic aspect too, especially in Northern Italy. |

| 11 | The sentence would look as follows:

|

References

- Bermúdez, Fernando Wachtmeister. 2011. El pluscuamperfecto como marcador evidencial en castellano. In Estudios de tiempo y espacio en la gramática española. Edited by Carsten Sinner, Elia Hernández Socas and Gerd Wotjak. Frankfurt am Main: Peter Lang, pp. 43–62. [Google Scholar]

- Bertinetto, Pier Marco. 1986. Tempo, aspetto e azione nel verbo italiano: Il sistema dell’indicativo. Firenze: Accademia della Crusca. [Google Scholar]

- Bertinetto, Pier Marco. 2003. Tempi verbali e narrativa italiana dell’Otto/Novecento: Quattro esercizi di stilistica della lingua. Alessandria: Edizioni dell’Orso. [Google Scholar]

- Bertinetto, Pier Marco. 2014. Non conventional uses of the Pluperfect in Italian (and German) literary prose. In Evolution in Romance Verbal Systems. Edited by Emmanuelle Labeau and Jacques Bres. Bern: Peter Lang, pp. 145–70. [Google Scholar]

- Bertinetto, Pier Marco, and Mario Squartini. 1996. La distribuzione del Perfetto Semplice e del Perfetto Composto nelle diverse varietà di italiano. Romance Philology 49: 383–419. [Google Scholar]

- Cerruti, Massimo, and Silvia Ballarè. 2020. ParlaTO: Corpus del parlato di Torino. Bollettino dell’Atlante Linguistico Italiano (BALI) 44: 171–96. [Google Scholar]

- Comrie, Bernard. 1976. Aspect. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- De Mauro, Tullio, Federico Mancini, Massimo Vedovelli, and Miriam Voghera. 1993. Lessico di Frequenza dell’Italiano Parlato. Milano: Etas. [Google Scholar]

- Diewald, Gabriele. 2011. Grammaticalization and pragmaticalization. In The Oxford Handbook of Grammaticalization. Edited by Bernd Heine and Heiko Narrog. Oxford: Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hopper, Paul J., and Elizabeth Closs Traugott. 2003. Grammaticalization. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Maiden, Martin, and Cecilia Robustelli. 2007. A Reference Grammar of Modern Italian, 2nd ed. London: Hodder Arnold. [Google Scholar]

- Mauri, Caterina, Silvia Ballarè, Eugenio Goria, Massimo Cerruti, and Francesco Suriano. 2019. KIParla corpus: A new resource for spoken Italian. In Paper present at the Proceedings of the 6th Italian Conference on Computational Linguistics CLiC-it, Bari, Italy, November 13–15; Edited by Raffaella Bernardi, Roberto Navigli and Giovanni Semeraro. [Google Scholar]

- Plungian, Vladimir, and Johan van der Auwera. 2006. Towards a typology of discontinuous past marking. Language Typology and Universals 59: 317–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scarpel, Sebastiano. 2017. Considerazioni sull’uso aoristico del trapassato prossimo. Studia de Cultura 9: 121–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Squartini, Mario. 1999. On the semantics of the Pluperfect: Evidence from Germanic and Romance. Linguistic Typology 3: 51–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Traugott, Elizabeth Closs. 2003. From subjectification to intersubjectification. In Motives for Language Change. Edited by Raymond Hickey. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, pp. 124–40. [Google Scholar]

- Traugott, Elizabeth Closs. 2010. (Inter)subjectivity and (Inter)subjectification: A Reassessment. In Subjectification, Intersubjectification and Grammaticalization. Edited by Kristin Davidse, Lieven Vandelanotte and Hubert Cuyckens. Berlin and New York: Mouton de Gruyter, pp. 29–71. [Google Scholar]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).