Abstract

Grammatical gender presents persistent difficulty for adult learners of Spanish in L2 acquisition; however, there is a literature gap in L3 acquisition of gender, specifically of typologically different languages. In this project, we investigate the acquisition of Spanish gender agreement by Russian (L1)/Mandarin (L1)-English (L2) speakers of Spanish (L3) and compare the findings with English(L1) speakers of Spanish (L2). Studying these languages is particularly interesting because some exhibit an explicit gender system (Spanish and Russian) while others do not (English and Mandarin). In order to examine the effect of L1/L2 influence of these languages on L3 Spanish acquisition, 55 participants completed two tasks: a picture identification task and a grammaticality judgement task. Results indicate that advanced learners of Spanish of all L1 backgrounds performed at or near ceiling. All beginner learners performed better with canonically marked masculine nouns than noncanonical feminine nouns, thus corroborating previous findings. Regarding L1 influence, Russian participants outperformed the other two groups, especially in Task 1 (Picture Identification), thereby indicating that they may be transferring to some degree the grammatical gender system of their L1. Overall, this research provides evidence that multiple factors, including structural typology and L3 proficiency level, play a role in L3 acquisition.

1. Introduction

Living in one of the most multicultural and multilingual countries, Canada presents a great opportunity to study a co-existence and interaction of languages in contact. Many immigrant communities who reside in Canada speak at least two languages; some learn and become proficient in a third language (L3). The main question that remains involves the role of previous languages in L3 acquisition as well as errors that are associated with L3 acquisition. Some linguists argue that the L2 serves as a primary source of cross-linguistic interference/influence (CLI), especially in the initial stages of L3 acquisition (see Bardel and Falk 2007; Cenoz 2003; Falk and Bardel 2011; Hammarberg 2001 for their discussion on “L2 status factor”). Flynn et al. (2004), on the other hand, proposed the Cumulative Enhancement Model (CEM), which posits that a scaffolding effect is observed in L3 acquisition in that any prior language can either enhance (i.e., scaffold) subsequent language acquisition or remain neutral (i.e., no effect). Rothman (2011, 2015) extends Flynn’s proposal and offers the Typological Primacy Model (TPM), which centers on the (psycho)typological congruence (i.e., perceived similarity) of either first language (L1) or L2 as an initial source of transfer. Therefore, building on previous L3 acquisition research, we investigate CLI while focusing on gender concord (e.g., el-masc. chico-masc. alto-masc. ‘the tall boy’) in the acquisition of Spanish as an L3 in learners from distinct linguistic backgrounds: L1 Mandarin and L1 Russian speakers who share a common L2 (English). Studying these languages is interesting because they are typologically different in terms of the grammatical structure examined: Mandarin Chinese is an isolating (analytic) language that lacks inflectional morphology; Russian and Spanish are fusional types (an inflectional morpheme corresponds to multiple syntactic and semantic features), and English is an analytic language (position of the words in a sentence determines their function). Regarding the gender system, some exhibit an explicit gender system (Spanish and Russian) while others do not (English and Mandarin). Given that the gender system is distinct in these languages, our first goal is to investigate to what degree the aforementioned groups of two proficiency levels (beginner vs. advanced learners) have acquired Spanish gender and whether L1 or L2 will lead to a more robust CLI effect on L3 acquisition. Our second goal is to understand the types of errors that learners from these language groups produce (e.g., errors linked to gender agreement vs. gender assignment).

Our paper is organized as follows. Section 1.1 provides background information on grammatical gender and number in Spanish, Russian, Mandarin and English. Section 1.2 introduces major theories on third language acquisition with particular focus on wholesale transfer and partial transfer models. Section 1.3 discusses previous literature on L2–L3 acquisition among adults. Section 2 focuses on the methodology of the project, including participants, methods, and data collection procedure and analysis. Section 3 discusses the results of the two tasks, followed by Section 4, which explains the results of the current project in light of relevant research and L3 acquisition theories and provides suggestions for future research.

1.1. Grammatical Gender and Number

This section provides background information on the four languages examined in the present study: Spanish, Russian, English and Mandarin. Despite being typologically different languages, Spanish and Russian share many morphological universals, specifically gender. In both languages gender is determined by declination classes. Regarding gender acquisition, usually the gender feature is acquired by the age of three in Spanish monolingual children (Hernandez Piña 1984) and as early as age two in Russian monolingual children (Gvozdev 1961). The other two languages lack morphological gender marking on nouns. Regarding number, Spanish, Russian and English all exhibit the number feature, while Mandarin does not. Most of monolingual children in English, Russian, and in Spanish acquire the distinction between singular and plural nouns by around age 2 (Lightbown and Spada 2021 for the discussion on English; Sarnecka et al. 2007 for the discussion on Russian; and Arias-Trejo et al. 2014 for the discussion on Spanish).

In order to better understand how the gender and number features vary in the four languages examined, Section 1.1.1 discusses grammatical gender in Spanish, followed by Section 1.1.2, which focuses on gender in Russian; Section 1.1.3 examines gender in English, followed by Section 1.1.4, which discusses gender and number alternatives in Mandarin.

1.1.1. Grammatical Gender and Number in Spanish

Grammatical gender in Spanish presents a binary system in which all nouns are assigned as masculine or feminine. In their thorough discussion on gender patterns based on phonological rules,1 Teschner and Russell (1984, p. 118) provide four generalizations about grammatical gender in Spanish, which include:

- (1)

- Nouns ending in “-a” and “-d” overwhelmingly tend to be feminine.

- (2)

- Nouns ending in “-n”, “-z”, and “-s” show only a slight preference for one gender over another and can effectively be judged indeterminate with respect to gender.

- (3)

- Nouns ending in “-e” largely tend to be masculine but do not lack a significant feminine component.

- (4)

- Nouns ending in the 18 other word-final letters are overwhelmingly masculine-gendered (of these 18, only “-l”, “-o” and “-r” are represented by a large number of items.

Most of the prototypical or canonical nouns in Spanish that end with “-o” are masculine (e.g., chico ‘boy’), while those that end with an “-a” are feminine (e.g., chica ‘girl’); though exceptions do occur (e.g., mano (fem.) ‘hand’). According to several researchers (Teschner and Russell 1984; Gamboa Rengifo 2012), about 99.4% of nouns which end in “-o” are masculine, and about 96.3% of those which end in “-a” are feminine. Moreover, canonical nouns roughly equal 68% of all Spanish nouns. The other types of Spanish nouns include non-canonical forms, which do not end in ‘o’ or ‘a’ (e.g., lápiz (masc.) ‘pencil’ or chocolate (masc.) ‘chocolate’). According to both Bergen (1978) and Teschner and Russell (1984), words that end in “-l” and “-r” almost invariably are masculine. Specifically, out of 1000 or more words that end in “l” and “-r”, only 2.15% and 1.45% of them are feminine, respectively. Words that end in “-e” are typically masculine (89.35% masculine compared to 10.65% feminine). Most words that end in “-z” are masculine, but a this often depends on the vowel preceding the final “-z”; for example, if the word ends in a front vowel and “-z” (“ez”), as in vejez ‘old age’, the word is feminine, whereas if the word ends in a non-front vowel “-oz”, as in arroz ‘rice’, the word is masculine (Teschner and Russell 1984, p. 122).

In Harris’ (1991) discussion on gender in Spanish, though all Spanish nouns have grammatical gender, assigned as either masculine or feminine, if the gender does not refer to biological/semantic sex, the gender assignment is therefore arbitrary such that “there is no correlation with either meaning or phonological shape of the stem” (Harris 1991, p. 36). Moreover, Harris (1991) argues that the exponence of gender in Spanish is modular, which belong to four domains of linguistic generalizations: biological or semantic sex, syntactic gender (masculine vs. feminine), morphonological form classes (“-o” vs. “-a”), and strictly phonological redundancy relations (p. 59). Based on the above types, only the semantic sex can be easily predicted. Although gender assignment is a lexical property of nouns, grammatical gender is realized at the syntactic level in which there must be agreement between articles and adjectives, thus resulting in two domains of grammatical gender: assignment and agreement (Alarcón 2009). For example, since chico ‘boy’ is a masculine noun, there must be an agreement operation where articles and adjectives are added (e.g., el-masc chico alto ‘a tall boy’), resulting in a masculine gender ending on the other two components.

Regarding the number variable, Spanish marks for singular and plural. Similar to gender agreement, there must be a number agreement between nouns and adjectives (e.g., una chica bonita ‘a beautiful girl’ vs. unas chicas bonitas ‘beautiful girls’), nouns and determiners (una flor ‘a flower’ vs. unas flores ‘some flowers’), and subject and verb (e.g., él va a la fiesta ‘he is going to a party’ vs. ellos van a la fiesta ‘they are going to the party).

1.1.2. Grammatical Gender and Number in Russian

Modern Russian also exhibits inflectional morphology and presents three gender forms (masculine, feminine, and neuter) and two number forms (singular and plural) with gender and number being marked on adjectives, nouns and verbs through gender agreement and subject-verb agreement. Grammatical gender in Russian is assigned by both semantic and formal rules. For animate nouns denoting humans, the gender is given based on the semantic factor, specifically according to a biological sex (e.g., мама [mama] ‘mother’–FEM., брат [brat] ‘brother’–MASC.) (Corbett and Fraser 1999; Corbett 1982, 1991; Wang 2014). Formally, Russian feminine nouns mostly in nominative case end with “-a” or -ya- (e.g., книга–[kniga] ‘book’; свинья–[svin’ya] ‘pig’), neuter nouns generally end with “-o” or-e- (e.g., кинo–[kino] ‘movie’; мoре–[more] ‘sea’), while masculine nouns predominantly end with a consonant (e.g., билет [bilet] ‘ticket’) (e.g., Corbett 1982; Corbett and Fraser 1999; Polinsky 2008). However, some animate nouns end with “-a” or “ya”, as in дядя [djadja] ‘uncle’ and папа [papa] ‘daddy/father’. In that case, the semantic rule applies. In one of her experiments, Wang (2014) tested 10 native speakers of Russian using four nonce words in Russian. Her results indicate that 80% of participants assigned and treated a nonce word that ended with –a as feminine; meanwhile, another nonce word that ended with –o was treated as neuter by 70% of the participants (Wang 2014, pp. 62–63). The other two words that ended with –i and –ju did not have a clear pattern and participants, overall, expressed difficulty assigning gender on these four nonce words since they were not familiar with the words nor their corresponding inflectional suffixes.

Corbett (1991) states that the gender assignment of declinable singular nouns in Russian is based on four declinational patterns or classes:

- (1)

- Declension I: Nouns with zero endings that end on soft or hard consonant (e.g., дoм [dom] ‘house’) are masculine

- (2)

- Declension II: Nouns that end on –a are feminine, but the nouns that are semantically masculine are masculine (e.g., дядя [djadja] ‘uncle’)

- (3)

- Declension III: Nouns that end the –i (soft sign) are feminine (e.g., мазь [maz’] ‘ointment’)

- (4)

- Declension IV: Nouns that are neuter that end on –o or –e (мoре [more] ‘sea’)

In other words, in Russian, all nouns belong to four different declination classes, which include six cases and each of them has its own gender.

It is important to note, that Corbett (1991) proposes the model, in which semantics takes precedence over the morphology. In other words, though a word that ends in –a should be feminine, if the word denotes male sex, it will be considered masculine. Therefore, the gender of the majority of nouns can be easily predicted, either from the semantic information retrieved from the lexical entry or from the formal information, which is either morphological or phonological (Corbett and Fraser 1999, p. 62). Regarding gender agreement, there must be gender agreement between attributive adjectives and nouns (e.g., бoльшая книга–[balshaya kniga] ‘a big book’), demonstrative pronouns (эта книга [eta kniga] ‘this book’, past tense forms (книга лежала на диване [kniga lezhala na divane]‘a/the book laid on the sofa’), and certain numerals (oдна книга [adna kniga] ‘one book’).

Regarding the number variable, Russian exhibits both singular and plural number across three gender forms. According to previous research, Russian-learning children acquire and understand singular versus plural contrast by the age of two (e.g., Sarnecka et al. 2007) and are able to produce singular and plural nouns and pronouns at around 18 months (Leushina [1974] 1991). Similar to gender agreement, number agreement in Russian occurs between nouns and adjectives, nouns and numerals/quantifiers, as well as between subjects and verbs (e.g., SINGULAR: бoльшая книга–[balshaya kniga] ‘a big book’ versus PLURAL бoльшие книги–[balshie knigi] ‘big books’).

1.1.3. Grammatical Gender and Number in English

Gender in modern English is no longer an inflectional category on nouns and therefore English lacks gender agreement with determiners, adjectives, pronouns, etc. (Huddleston and Pullum 2002). However, English retains (limited) features of natural gender categories from Old English namely in the use of nouns and pronouns according to the natural gender of the referent. The use of theses gender categories can be seen in third-person singular pronouns he and she, in reference to people of a particular sex in certain occupations actor/actress, and in word borrowings fiancé/fiancée (Bas and McMahon 2006). Nonetheless, these features of gender are limited to only nouns and are not marked morphologically and exhibit no syntactic gender agreement. For example, determiners and adjectives have only singular and plural forms and do not change form to describe people of a particular gender.

Number in English can be marked morphologically on the noun (books) and lexically with the use of some quantifiers (many, a lot of), with the corresponding noun also marked morphologically. Singular/plural marking is acquired early in L1 English-learning children with comprehension of the distinction occurring between 20 and 24 months of age (Barner et al. 2007; Kouider et al. 2006). Studies of productive speech find that children also produce plural marking on nouns by around their second birthday (Brown 1973; Cazden 1968; Mervis and Johnson 1991; cited in Sarnecka et al. 2007).

1.1.4. Grammatical Gender and Number in Mandarin

Mandarin, another language under study, is an isolating language as it lacks marking for gender and number, so speakers can only semantically differentiate the meaning of sentences. Consider the following examples, (1) and (2):

| (1) | yi | ge | gao | nan | hai |

| one | CL | tall | male | child | |

| “a tall boy” | |||||

| (2) | wu | ge | gao | nü | hai |

| five | CL | tall | female | child | |

| “five tall girls” | |||||

As seen in the above examples (1) and (2), while Mandarin has no grammatical gender, one can introduce a lexical word ‘nan’ (male) or ‘nü’ (female) when wanting to show semantic distinctions in gender (Li and Thompson 1981; Farris 1988). It can also be seen that Mandarin lacks articles and instead requires a classifier before bare nouns, such as the clitic ‘ge’ in examples (1) and (2), the classifier for people and countable nouns, to express the English equivalent of the [article + noun(s)] construction (Huang et al. 2009).

1.2. Theory on L3 Acquisition

In the past two decades, researchers have been investigating L3/Ln acquisition or L3 interlanguage development while focusing specifically on the role of previously acquired languages. Some have advocated for an L1 model; the L1 Status Factor states that transfer from L1 into L3 occurs at the initial stages of acquisition (for more discussion see Hermas 2010; Leung 2005). Directly opposing the primacy of L1 on L3 acquisition, Bardel and Falk (2007, 2012) examined the placement of negation among L1 German-L2 English learners of Dutch/Swedish as L3 and found that, in fact, L2 was preferred as a transfer source in L3 syntax in the initial as well as intermediate stages of L3 acquisition. Bardel and Falk (2007, 2012) and Falk and Bardel (2011) thereby argued for the L2 status factor model based on the psychological and cognitive prominence of the L2 for subsequent language learning among adult learners, particularly during the early stages of L3 morphosyntactic development. Specifically, they draw a distinction between ‘procedural memory’ and ‘declarative memory’ and claim that the grammars of native and non-native languages are sustained by different memory systems: ‘procedural’ for L1 acquisition and ‘declarative’ for L2. As for L3 learners, they also rely heavily on declarative memory, since L2 and L3 are cognitively more similar. When L2 and L3 are acquired after the critical period, Bardel and Falk (2012) argue that non-native systems are fundamentally different from the native system. Contrasting this claim, Schwartz and Sprouse (1994, 1996, 2013, 2017, 2021) believe that L2 grammars are equivalent to L1 grammars, since they “display the same sorts of demonstrations of overcoming poverty –of- the- stimulus phenomena as native language grammars, and it is difficult to imagine how these properties could have been fixed in the minds of adult L2ers unless (adult) L2 acquisition is guided and constrained by UG, just as L1 acquisition” (Schwartz and Sprouse 2021, p. 13). One of the first studies on L3 acquisition and the effect of L1/L2 was conducted by Flynn et al. (2004) examining the use of English restrictive clauses (RC) (e.g., ‘The lawyer who criticised the worker called the policeman’) among L1 Kazakh-L2 Russian children and adults acquiring English (L3). The position of RC differs across the three languages; Russian is similar to English in its word order and right-branching, while Kazakh is a left-branching language. Their results showed that L1 did not have a privileged effect in L3 development, but rather that there was a transfer effect from L2, possibly due to structural similarities. They proposed the Cumulative Enhancement Model (CEM), which states that any prior language, whether it be L1 or L2, can either enhance or have no effect on subsequent language acquisition. In other words, in terms of transfer selection there are two possibilities: (1) if one of the languages, either L1 or L2, contains the target property of L3 but the other does not, the former will transfer or (2) if neither L1 nor L2 has the target property, transfer will not occur and L3 will be acquired the same way as L1 without any interference. Unlike the CEM, Slabakova (2017) proposes the Scalpel Model in which she claims that both facilitative and non-facilitative transfer can occur from any previously acquired grammars on a property-by-property basis, but that there are many additional factors affecting transfer, such as “construction frequency, availability of clear unambiguous input, prevalent use, and structural linguistic complexity, among others” (Slabakova 2017, p. 653). Similar to Slabakova’s model, Westergaard et al. (2017) proposes the Linguistic Proximity Model (LPM), which states that Ln acquisition involves property-by- property learning and transfer can occur from any previously acquired languages. In cases in which two languages are typologically similar (L1 and L3 or L2 and L3), usually surface or lexical transfer will occur at the initial stages. Westergaard (2021) states, however, that even simple syntactic properties can be parsed and transferred at the initial development stage, which contradicts Rothman’s wholesale Typological Primacy Model.

Finally, another model, which received much attention, is the Typological Primacy Model (TPM), proposed by Rothman (2011, 2015). In his model, Rothman (2011) states that L1 or L2 can be the source of transfer during the very beginning of L3 development if any of these languages is perceived to be typologically similar to L3. Thus, during the initial stages, the parser assesses and determines true grammatical similarity between languages subconsciously (Muñoz-Liceras and Alba de la Fuente 2015, p. 331). The parser then selects either the full L1 grammar or the full L2-Interlanguage grammar as the basis for the initial grammatical state, depending on which of the two previously acquired languages is (psycho)typologically more similar to L3 (Rothman et al. 2019). When the languages are typologically different, the TPM predicts that some structural similarity will be a decisive factor for transfer to occur. In his study on adjectival pre-nominal and post-nominal interpretation among L1 Italian learners of English (L2) at the low to intermediate proficiency level of L3 Spanish, and L1 English–L2 Spanish and L3 Brazilian Portuguese (BP) learners, Rothman (2011) found that the transfer to BP was favoured from Romance languages (L1 Italian and L2 Spanish), specifically due to the typological structural similarities between Romance languages. In other words, he concluded that it was the language structural typology that took precedence and determined multilingual syntactic transfer. Rothman (2015) proposes a four-level hierarchy of linguistic cues, which a parser processes during L3 acquisition in descending order of prominence: lexicon--> phonology_--> morphology--> syntax. In other words, the parser compares and accesses the degree of structural similarity between L3 and the other acquired languages, leading to transfer. This is evident in his recent study (Rothman et al. 2019), which investigated negative quantifiers (NQs) and negative polarity items (NPIs) among L1 Catalan-L2 advanced Spanish speakers and L1 Spanish-L2 Catalan speakers acquiring English as an L3. Though both Spanish and Catalan exhibit negation, they do not differentiate between NQs and NPIs, and only have one negator, but the position of this negator corresponds to different semantic readings, which pattern with English (e.g., in the preverbal position, Spanish N-words pattern with English NQs, but in the object position of a conditional, Catalan N-words pattern with English NPIs). Using a forced-choice Picture Naming Task, Puig-Mayenco et al. (2020) found that irrespective of the order of acquisition (L1 Catalan or L2 Catalan), the Catalan group chose patterns and interpreted all four types of English sentences using the cues from Catalan, 83–92% of the time, thereby providing evidence in support of the typology model and evidence contradicting the L2/L1 factor, as both groups relied on either L1 or L2.

Though the focus of our study is not to explicitly test all the above models, based on the current findings, we will explain our results and propose suggestions in accordance with these models.

1.3. Research on L2 and L3 Acquisition

To the best of our knowledge, there has been no research to date focusing on the specific language pairings of the present study. In general, there has been limited literature on L1 Mandarin Chinese and L3 Spanish. In a study on null subjects and objects in main and embedded clauses among L1 Chinese-L2 advanced English -L3 novice Spanish/French learners, Kong (2015) found that Cantonese Chinese (L1) was the source of most of the transfer cases. Kong concluded that this was due to its typological similarity to Spanish and French, specifically the structural positions of null/object pronouns in these three languages. In another study by Cai and Cai (2015) on L3 French past tense usage among L1-Chinese/L2-proficient English/L3-intermediate speakers of French, the researchers found that L3 participants generally transferred the past tense marker from English, the language that exhibits tense markers; however, cases of transfer from Chinese were also found. The researchers attributed this to the varying degrees of English dominance. Specifically, those participants who had a lower degree of English proficiency showed a higher rate of transfer from their L1. Therefore, it appears that transfer source is necessarily conditioned by proficiency level in the available languages. Leung (2005) conducted a comparative analysis of two groups (L1 Cantonese-L2 English-L3 French and L1 Vietnamese-L2 French) by studying their production of determiner phrases in French. Her findings showed that the L1 Cantonese group transferred morphosyntactic properties from English (L2) while the L1 Vietnamese group transferred determiner omissions from their L1. Based on these findings of the initial and intermediate stages of L3 development, participants seem to transfer features from their L1, but as their proficiency level increases, the transfer source shifts to their L2 as it becomes available for transfer (i.e., once it is fully acquired) due to the typological similarity between L2 and L3.

Regarding error type, research shows that late L2 learners demonstrate persistent errors, particularly in oral tasks. Possible explanations for persistent errors among late L2 learners include different language learning mechanisms with cognitive maturity which may lead to a fundamental representational deficit in adult mental grammars. According to Bley-Vroman’s Fundamental Difference Hypothesis (FDH: 1989; 1990), adult L2 learners are forced to rely on explicit or general learning mechanisms to acquire another language post-puberty and do not maintain access to the implicit and linguistically specific learning mechanisms of Universal Grammar (UG), which goes against Shwartz’ and Sprouse’s claim on equivalency between L1 and L2 grammars as both have access to UG (refer to Section 1.2). Hawkins and Franceschina (2004) propose the failed functional feature hypothesis (FFFH), which states that adult learners are incapable of acquiring uninterpretable features, as for example gender, in their L2 if this feature is absent in their L1. In other words, English learners of Spanish are unable to acquire the L2 gender system, because English does not morphologically mark gender. In contrast, learners of those languages that do exhibit gender (e.g., Romance, Slavic languages) are able to successfully acquire gender, because this feature is present in their L1 (Sabourin 2001).

With regard to the learning of morphosyntax, McCarthy (2008) proposes the Morphological Underspecification Hypothesis (MUH), which also supports the representational deficit view of SLA, arguing that grammatical gender errors may be more common with one gender (e.g., the feminine in Spanish) than the other (e.g., masculine) due to the overgeneralization of a default form (e.g., masculine). In their study on gender attribution and gender agreement among young French children, aged 4–10, Boloh and Ibernon (2010) note that masculine forms are more frequent and numerous than feminine counterparts. Besides, in the case of noun-adjective gender agreement, the feminine form of the adjective is phonologically heavier and more complex than the masculine one (p. 17), which encourages the learner to opt for the masculine option. In the case of the vocalic endings, Corbett (1991) claims that most of the nouns are biased towards masculine or neutral and not feminine. In Alarcón’s (2009) study comparing the response times of native Spanish speakers (n = 22) and L2 Spanish learners (n = 139) on a sentence-completion task, it was found that L2 learners have difficulties processing gender morphologically during a timed task, whereas other studies (Foote 2009; Montrul et al. 2008) show that L2 learners perform better in untimed comprehension and production tasks with nouns that have overt morphological markings for gender (i.e., canonical nouns). In another study, Montrul et al. (2014) compare L2 intermediate-advanced speakers and heritage speakers of Spanish through an oral elicitation task and found that heritage speakers outperformed L2 learners in assigning gender for both canonical and non-canonical nouns, whereas L2 learners were much more affected by noun morphology, performing significantly better with canonical nouns than non-canonical nouns. Furthermore, among L2 learners, more production errors were found with determiner agreement (i.e., gender congruence between the article and the noun) than with adjective agreement (i.e., gender congruence between the noun and the adjective). More significantly, L2 learners were more accurate with masculine nouns than with feminine nouns. This finding is consistent with other studies demonstrating that L2 learners tend to overgeneralize the masculine and erroneously apply it to feminine inanimate nouns (e.g., Bruhn de Garavito and White 2002; Gamboa Rengifo 2012; Montrul et al. 2008). Given that the masculine form is treated as a default and is therefore overextended to feminine nouns, previous studies show that L2 speakers produce higher error rates with gender agreement on feminine nouns than on their masculine counterparts (Montrul et al. 2008; Gamboa Rengifo 2012).

Similar to L2 learners, Tararova’s pilot study in 2012 showed that Russian heritage speakers in Canada seem to over-simplify gender agreement while speaking L3 Spanish, specifically, by overusing masculine forms in place of feminine counterparts, possibly due to speakers’ extensive use of English. In another pilot study of recent Russian newcomers learning Spanish as L3, Tararova (2012) found that most errors were with masculine forms and not their feminine counterparts. A possible explanation for this finding is the inflectional ending resemblance between Russian and Spanish, since in both languages, the feminine forms end in ‘a’ (e.g., hermana ‘sister’ and сестра [sestra] ‘sister’). The errors were found with non-canonical endings and those words that mismatched in the two languages (e.g., fem: книга–[kniga] ‘book’ vs. masc: libro ‘book’). This finding is consistent with Polinsky’s (2008) study on young heritage Russian speakers in the US, where the participants had to assign the gender to the given noun and match it with the corresponding adjective in their feminine, masculine, or neuter forms. Results demonstrate that although Russian learners of L3 Spanish had no problem producing masculine forms and feminine nouns that ended in “-a” and were able to consistently assign correct gender on the adjective, feminine words that ended on a palatalized consonant (пoстель [postel’] ‘bed’) presented more difficulty and resulted in overgeneralized masculine assignment.

Regarding number agreement, previous research shows that, overall, number agreement seems to be less problematic than gender agreement, but that L2 learners nonetheless seem to overgeneralize and produce singular forms instead of plural ones (e.g., McCarthy 2008). In a picture naming elicited production task, McCarthy (2008) tested 24 beginner participants of L2 Spanish at intermediate and advanced levels. Her findings showed that intermediate learners were more accurate with singular number on adjective-noun concord (99.6%) than plural agreement (68%), suggesting that the use of singular agreement is a default overextended to plural contexts. For the advanced speakers, although most of them produced correct responses on both forms, again, plural agreement was more difficult (83% compared to 100% for singular forms), demonstrating that plural number remains problematic even at the advanced level (p. 476).

2. Research Questions and Predictions

Based on the research on L3 acquisition and given the typologically diverse backgrounds of the languages under study, we formulate two research questions followed by the corresponding hypotheses.

- R1: What is the effect of native language morphological typology on performance with grammatical gender and number agreement as well as error type in L3 performance and what may this indicate about the source of transfer in L3 acquisition? In other words, which model of L3 acquisition seems to best fit the performance results of the L3 learners in the present study?

Hypothesis 1.

We extend Sabourin’s (2001) conclusions that the presence of a grammatical gender system in L1, as well as the typological similarity between the systems in L1 and L2, suggested by Muñoz-Liceras and Alba de la Fuente (2015), strongly influence the acquisition of the L2 grammatical gender system. We thereby predict that the Russian group will outperform the other two groups since Russian and Spanish, despite being typologically different languages, are similar with regard to their gender morphology: they both have declination classes which correspond to particular genders. In this case, Russian speakers learning L3 Spanish will likely transfer L1 features to L3 Spanish, specifically at the initial stages (e.g., beginner). If this is true, our findings will align with the TPM, proposed by Rothman (2011), Rothman et al. (2019). We also predict that the English learners will outperform the Mandarin speakers in number agreement because English also exhibits a number agreement system while Mandarin does not. As for the Mandarin group, we predict transfer of number agreement from English, which would corroborate the L2 factor hypothesis.

- R2: What is the effect of grammatical gender (masculine vs. feminine), morphological form (canonical vs. noncanonical), and number (singular vs. plural) on accuracy with gender and number agreement in Spanish for each language group?

- a. Is there a difference according to the participant’s level of proficiency (beginner vs. advanced)?

Hypothesis 2.

The second research question investigates the effect of noun agreement in gender and number for each of the three language groups. In line with previous studies, we expect to observe more errors with feminine nouns than with masculine nouns for all our learner groups, due to the overgeneralization of the masculine form as default, as predicted by the Morphological Underspecification Hypothesis (McCarthy 2008) and supported by previous research (e.g., Foote 2009; Gamboa Rengifo 2012; Montrul et al. 2008; Polinsky 2008). We predict that the Russian group will produce fewer errors with feminine nouns in comparison to the other learner groups, due to morphological resemblance between feminine –a endings on feminine nouns in Russian and Spanish. We also predict that morphologically noncanonical nouns will prove more difficult to acquire for L1 English-L2 Spanish learners and L1 Mandarin-L3 Spanish learners as empirical evidence suggests that learners use overt noun morphology as a cue when processing grammatical gender (e.g., Montrul et al. 2014). Regarding number, we hypothesize that Russian speakers will be able to correctly perform the number agreement operation since Russian also marks number on adjectives and nouns. We expect the plural form to be more problematic for English L2 learners than singular agreement, based on McCarthy’s (2008) findings. In line with Cai and Cai (2015) and Kong’s (2015) conclusions, the beginner Mandarin group will produce the most errors with both gender and number categories, since both of these features are absent in their L1.

Hypothesis 2a.

In line with previous studies (e.g., Montrul et al. 2008), we expect gender to be a grammatical domain in which advanced learners can achieve near-native competence. More specifically, we predict that the Russian L3 advanced group will perform similarly to the Spanish native speaker control group. However, since the gender feature is absent in the prior linguistic repertoire of both Mandarin and English speakers, it is possible that these two groups, even at the advanced level, will not be able to achieve native-like competence in Spanish. If this is true, our findings will align with Hawkins and Franceschina’s (2004) failed functional feature hypothesis (FFFH). Regarding number agreement, Russian and English learners of both beginner and advanced proficiency levels will perform at ceiling, since the number feature is available in their L1. It is expected that the Russian group will outperform the English group, especially at the beginner level, because Russian marks number on both adjectives and nouns, while English only marks number on nouns. As for the Mandarin L3 group, we predict that the advanced proficiency group’s performance will align more with the English L3 group, as a potential indicator of L2 transfer, as these learners will be at a sufficient level of L2 proficiency so as to transfer number agreement from their L2 (English).

3. Materials and Methods

3.1. Participants

A total of 55 adult participants were recruited between December 2020 and October 2022. Our beginner participants were students from the University of Western Ontario who were taking Spanish at the beginner level. Our advanced speakers were either alumni, graduate students, or current students at Western and other universities. The L3 group included L1 Russian (n = 15) and L1 Mandarin speakers (n = 15) who moved to Canada after the age of 15. Based on their self-reports, all the speakers were proficient in their L1 as well as English (L2).2 The criteria for L1 English participants (n = 15) were that they be over the age of 18+, born in Canada, with no knowledge of any other language,3 except taking Spanish at the beginner level. Additionally, a total of 10 controls (native speakers of Spanish who moved to Canada after the age of 16) were included in the study as a baseline for comparison. Table 1 shows the distribution of participants.

Table 1.

Participant profile.

3.2. Methods

This study is part of a larger ongoing project including four tasks that focuses on native and heritage speakers of typologically different languages acquiring L3 Spanish. For this paper, we only present two tasks that were completed online via Zoom in individual sessions with a researcher, including a picture identification task and a grammatically judgment task. For the first task, the participants saw a series of objects with pictures presented in PowerPoint slides; they were asked to describe the picture pairings orally (see example 1). The task included 2 model examples, followed by 2 practice questions, 24 target items (12 masculine and 12 feminine nouns, divided into canonical and non-canonical forms), and 10 distractor questions (questions that included infinitives). We did not include any exceptional noun stimuli that contradict the prototypical pattern; that is, nouns that end in –o yet are feminine (e.g., la mano, ‘the-fem hand’) or that end in –a yet are masculine (e.g., el problema, ‘the-masc. problem’).

| (3) |  |

In Example 1, los ‘the’ refers to a masculine plural definite article. The third option, limones ‘lemons’ is the only grammatical option since it is the only noun of the three that is both masculine and plural.

In the second task, participants saw a question followed by four possible answers to choose from (see example 2). Each question with its four options was presented in PowerPoint slides. Participants were asked to select the option that best answered the question. The task included 3 practice items, 24 target items (12 masculine and 12 feminine nouns, separated into canonical and non-canonical forms), and 10 distractor items (e.g., questions that did not include gender concord).

| (4) ¿Qué tomas en la mañana? | |

| What do you drink in the morning? | |

| (a) | *tomo una jugo frío de naranja |

| (b) | *tomo un jugo fría de naranja; |

| (c) | *tomo una jugo fría de naranja; |

| (d) | tomo un jugo frío de naranja |

| ‘I drink a cold orange juice’ | |

In example 2, option ‘d’ is the only grammatical one, since jugo ‘juice’ is a masculine noun; therefore, the article un ‘a’ and frío ‘cold’ must morphologically agree with the noun. All the target noun stimuli were controlled for their relative frequency and familiarity as we included only the most frequent nouns found in recently studied chapters of the beginner Spanish textbook used in the language program at Western University, Canada (Blanco and Donley 2020, Vistas—Volume 1, 1–10).

3.3. Procedure

Prior to the experiment, all interested participants were given a letter of information and consent form to be signed. Prior to their online research session, each participant completed a linguistic profile questionnaire in PDF format, adapted from the Bilingual Language Profile Questionnaire (BLP: Birdsong et al. 2012), which takes into account a variety of sociolinguistic variables including language history, use, proficiency and attitudes, in addition to other personal information such as gender, age, L1 and parents’ L1, education level, other languages known, etc.4 Each participant received their ID code prior to the recording (e.g., a Russian (R) native (N) beginner (B) speaker = RNB01). On the day of the interview, each participant received an invitation link to join an individual Zoom session to complete the experimental tasks with a researcher. The L3 participants were first interviewed in their L1 by a native speaker to ensure their level of proficiency in their L1. Then, they were audio and video recorded while performing four tasks. The whole experiment was conducted in one session and took between 30 to 45 min. The participants were compensated after the experiment in the form of an Amazon gift card.

3.4. Data Analysis

A total of 2640 tokens from two experiments were analyzed. Participant data was recorded and analyzed according to the linguistic variables noun gender classification (masculine/feminine), morphological gender marking (canonical/noncanonical), number (singular/plural), and social/individual variables (type of L1 and self-reported Spanish proficiency level (beginner/advanced)). The accuracy scores for the two tasks were analysed with IBM SPSS Statistics version 28.0.1.1 (14) with the level of significance at 0.05 (IBM Corp. 2021).

4. Results

This section presents the results obtained from 55 participants (2640 tokens).

Overall, advanced learners of all three groups performed at or near ceiling, especially in Task 1, but some differences were detected, according to Table 2.

Table 2.

Accuracy scores among the three advanced language groups in Task 1 and Task 2.

The Russian speakers outperformed the other learner groups in two tasks and were able to converge on native speaker performance. Regarding gender form, Mandarin speakers scored higher on masculine forms than on feminine nouns. As for morphological cues, Mandarin and English learners produced more errors with non-canonical forms, which supports our hypothesis. As for the number variable, Mandarin speakers showed similar patterns to the English learners; specifically, more errors were found with the plural nouns, which again supports our initial hypothesis.

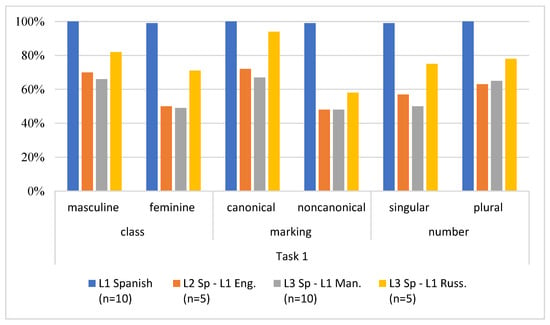

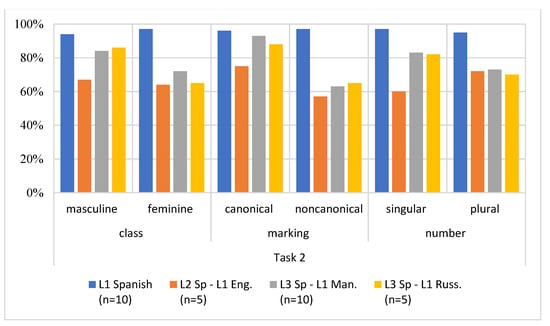

As for the beginner groups, clear distinctions were found. Therefore, for the rest of the paper, we focus on the beginner groups only. To understand better the type of errors and to determine if there is a possible task effect, we present the results for each of the two tasks separately. Figure 1 demonstrates the effect of the linguistic variables analyzed (syntactic gender, form class, and number) on accuracy with gender agreement comparing the three learner groups and controls in Task 1. Figure 2 presents the effect of the linguistic variables analyzed (syntactic gender, form class and number) on accuracy with gender agreement comparing the three learner groups and controls in Task 2.

Figure 1.

Accuracy Scores among three language groups in Task 1.

Figure 2.

Accuracy Scores among three language groups in Task 2.

As seen in Figure 1, in the Picture Identification Task, all three groups produced more errors with the feminine form, by overgeneralizing the masculine form (e.g., los flores instead of las flores ‘the flowers’).

A Kruskal–Wallis H test with all pairwise comparisons as post hoc showed that there was a significant difference of Task 1 accuracy scores, H (3) = 25.554, p < 0.001; while the L1 Russian group performed almost native-like (p = 0.031), L1 English group’s (p = 0.000) and L1 Mandarin group’s (p = 0.000) accuracy scores were significantly different from that of the L1 Spanish control group (Table 3 and Table 4.) The Russian group, hence, outperformed the other two learner groups, roughly by 20%, which may suggest the transfer of the grammatical gender system of their L1. As for the form class, all three groups performed better with canonical nouns than non-canonical forms, which supports our initial hypothesis, but again there were differences observed. Overall, the Russian group outperformed the other two groups, followed by Mandarin’s L3 performance. Regarding the number variable, three groups performed (slightly) better with plural numbers than singular forms, but again, the Russian group produced more correct answers than the other two groups.

Table 3.

Kruskal–Wallis Test result.

Table 4.

Pairwise Comparisons table.

As for Task 2, a Kruskal–Wallis H test with all pairwise comparisons as post hoc revealed that while all learner groups performed statistically less accurately that the L1 Spanish control group, there was no significant differences between these learner groups. Similar to Figure 1, in Figure 2, the three learner groups had more errors with feminine nouns than masculine ones, which was expected as per our initial hypotheses. However, group differences were also detected; unlike in Task 1, in Task 2, the grammaticality judgment task, the findings show a different pattern: the Russian group produced more errors with feminine nouns (34% error), as opposed to the Mandarin group (28%). The English group produced a similar percentage of errors with feminine and masculine nouns. Regarding the effect of class form, all groups performed better with canonical nouns (e.g., prototypical nouns that end in -o for masculine and -a for feminine), but again, the Mandarin group outperformed the other two groups when producing canonical forms. As for non-canonical endings, the Russian group performed slightly better than the Mandarin group. Regarding morphological number, the nouns with plural endings seemed to be easiest for the English bilingual participants across the two Tasks. For the Mandarin speakers, a different pattern for number is observed: in Task 1, they were more accurate with the plural nouns, whereas in Task 2, the participants performed better with singular nouns, indicative of a possible task effect. For the Russian group, the difference in Task 1 was minimal for morphological number, but in Task 2, the Russian participants clearly performed better with the singular nouns. A paired samples t-test confirmed this task effect for beginner learners, that is, a significant difference in accuracy scores was detected between Task 1 and Task 2, t (39) = −2.200, p = 0.034) (Appendix A).

As for the group differences, we predicted that Russians would outperform the other two groups, followed by English outperforming the Mandarin group in number agreement, specifically. Our findings somewhat confirm our predictions.

Based on Table 5, the Russian group outperformed the other two groups on Task 1, followed by the other two groups who showed minimal discrepancy in their scoring. In Task 2, however, the Mandarin learners outperformed the other two groups. The difference between Mandarin and English speakers was noteworthy. Additionally, looking at individual performance of the beginner learners on Task 2, we noticed that the percentage of accuracy varied for all three language groups: for L1 English, 42–83%, for Russian L3 learners, 67–87.5%, for Mandarin L3 learners, 70.83–91.67%. There were 2 Mandarin speakers who scored 83.3% (20/24 target nouns) and 1 speaker 91.67% (22/24 target nouns) but also 6 participants whose accuracy reached only 75%. For Russian speakers, there were 4 participants who scored 81–87.5%, but also 2 other learners who were 66% accurate. Therefore, due to the individual performance differences, future analysis should focus on analyzing individual data in order to attain a deeper understanding of error type.

Table 5.

Accuracy scores (%) among beginner groups on two tasks.

Overall, on the two tasks, results indicate accuracy scores on masculine nouns were higher for all participants, including Russian speakers, indicating that masculine as default may be a general processing strategy irrespective of L1. Secondly, canonically marked masculine nouns presented the least difficulty while noncanonical feminine nouns were most difficult, thus corroborating previous findings (e.g., Montrul et al. 2008). Finally, as for number, a possible task effect was observed, which will be further discussed in the next section.

5. Discussion and Conclusions

The present study focused on investigating performance with grammatical gender among speakers of typologically different languages, including Russian, Mandarin and English, who have been acquiring Spanish as an L3 in the university setting. In this project, we were interested in observing the possible effect of structural typology on the gender and number variables. We also wanted to highlight the types of errors that the different learner groups demonstrate while acquiring Spanish and examine whether these errors are similar across the three learner groups.

Our first research question investigated whether L1 structural typology plays a role in the acquisition of gender and number concord. All our advanced participants performed similarly, regardless of their L1, which might suggest that typology does not play much of a role at the advanced level of proficiency. In Section 1.2, we also discussed two types of transfer models in L3 acquisition: wholesale models (L1 factor, L2 factor, TPM), which refer to substantial transfer of either L1 or L2 to L3 specifically at the initial stages of acquisition, and piecemeal transfer models (CEM, Scalpel, and LPM), which state that transfer occurs on a property-by-property basis throughout L3 development. Based on the results from our beginner participants, it is difficult to conclude which model best fits our findings due to a relatively small number of participants per category. At the beginner level, we see the results of the Mandarin speakers somewhat align with the English L2 group, but as mentioned in the results section, they obtained higher accuracy scores on the second task. Based on these findings, our L2 Factor prediction is not confirmed, but the results seem to align with the piecemeal transfer Scalpel Model, proposed by Slabakova (2017), corroborating the idea that other possible factors (e.g., structural complexity, frequency of input) may lead to transfer in L3 acquisition. As we mentioned earlier, since the Mandarin L3 group recently moved to Canada, their mode of acquisition of a non-native language is different from the English group (e.g., more explicit focus on grammar through reading, and less on oral skills) and thus might have resulted in their higher accuracy on the second task. Since Slabakova (2017) does not fully describe the conditions of these other factors, it is hard to fully adopt this model to our Mandarin group. Regarding our second L3 group, the Russian group overall did better on both tasks when compared to the other two learner groups, which suggests that knowledge of another gendered language plays a role in language acquisition and transfer. Based on these findings, it seems that at the initial stages, the results of the Russian L3 group could align with the TPM. Another important argument to make is that despite being typologically distant languages, Russian and Spanish are similar in the sense that they share some typological universals, in this case gender, as in both Russian and Spanish gender belongs to declination classes. Therefore, Russian learners have access to its retrieval. Puig-Mayenco et al. (2020) also propose a possibility of a so-called “hybrid transfer”, a term which refers to simultaneous transfer from L1 and L2. This seems to be aligned with the Competing Grammars Hypothesis, which addresses response optionality resulting from the speaker’s access to two different rules or competing grammars, i.e., English (lack of gender, masculine by default) and Russian (masculine or feminine) (Muñoz-Liceras and Alba de la Fuente 2015, p. 335). This, in fact, seems to align with the results of our L3 Russian group, as we find transfer features from both L1 and L2 when it comes to overgeneralization of one form as transfer from English (L2), but we also find enhanced accuracy with feminine nouns, indicative of potential transfer from Russian (L1).

Our second research question investigated the effect of gender (masculine vs. feminine), inflectional forms (canonical and non-canonical endings), and morphological number (singular vs. plural) on performance with Spanish gender and number agreement. Regarding masculine and feminine score differences, our results indicate that feminine noun forms were prone to be more difficult for all beginner learner groups, which corroborates previous research (Montrul et al. 2008; McCarthy 2008). Based on McCarthy’s (2008) MUH hypothesis, the learners seem to overgeneralize and, by default, prefer the masculine form, because it is easier to process (Boloh and Ibernon 2010). This is what we have observed in our results. Despite the gender feature being available to Russian speakers, they still exhibit more errors with the feminine form, by overgeneralizing the masculine form. This difference in performance across masculine and feminine nouns could also be attributable to mismatching gender between Spanish and Russian; in other words, in Russian, the noun might be masculine, so they transfer the masculine assignment to the equivalent noun in Spanish. Our future research will investigate matching versus mismatching forms (i.e., noun gender congruence across languages) in Russian and Spanish in order to determine to what extent gender assignment in Russian may be transferred to the acquisition of grammatical gender in Spanish.

Regarding the gender forms, the learners of all three groups were more accurate with canonical nouns than non-canonical forms, which confirms our hypothesis and corroborates previous research (e.g., Foote 2009; Gamboa Rengifo 2012; Montrul et al. 2008). Again, similar to previous findings, Russian speakers demonstrated greater accuracy, which might indicate that learners of gendered languages which share typological or formal universals (e.g., access to gender) have an advantage when acquiring another gendered language. It is important to note, however, that the results of the Mandarin L3 learners show very interesting patterns. Specifically, in the grammatically judgement task, the Mandarin group slightly outperformed the Russian group with accuracy scores on canonical items, which may be indicative of a task effect. Given the fact that L1 Mandarin participants performed better on Task 2 in which they could see the questions and answers written on the slides and performed less accurately on the picture identification task that focused more on the relationship between the text and a corresponding image, may signal an affinity towards reading tasks for this particular group of learners. This affinity for a reading task could be attributable to the language learning background of the Mandarin participants. These participants recently moved to Canada from China and therefore are habituated to a more traditional type of language teaching methodology (e.g., grammar translation method (Álvarez et al. 2008) that focuses on written and reading proficiency. Another trend noticed with the Mandarin speakers is that they also performed much slower and took more time with their responses compared to the other groups, which could explain their enhanced accuracy scores. Future research should examine task completion times as an explanatory variable to determine how much of the variation in accuracy scores between learner groups may be explained by how much time learners take to complete a task, that is, whether slower times lead to greater response accuracy.

Apart from differences in participant performance potentially related to an affinity towards picture versus more textual tasks, we further consider other possible task effects. We assert that both Task 1 (Picture Identification) and Task 2 (Grammaticality Judgment) assess knowledge of grammatical gender assignment and agreement through the use of stimuli featuring both articles and adjectives. Therefore, the fundamental difference between these two tasks does not lie in the grammatical domain assessed, but rather in the nature of the task itself, that is, the procedural experience for the participants and how they are asked to respond. For Task 1, participants were asked to select the correct image with its corresponding bare noun in response to a written prompt containing the determiner phrase but no adjective. In Task 2, by contrast, the participants were provided with four written variations of a complete sentence containing the target noun and possible determiners and adjectives (only one of which was grammatically correct). Therefore, in this sense, Task 2 could be interpreted as having two possible cues indicating the grammaticality of the prompt: the determiner and the adjective, whereas Task 1 provided participants with only one cue—the determiner—by which to select the noun that fits. Therefore, a possible task effect may have arisen from a difference in the number of cues present in the written linguistic signal of each task, as our data demonstrate enhanced performance on Task 2 among the beginner learner groups even though native speakers did not appear affected by task differences.

Regarding the number variable, overall, the Russian group outperformed the other two learner groups. As recalled from the Introduction, Russian marks number on adjectives and nouns, so we expected this group to be the most accurate. As recalled from the background on languages, Russian and Spanish are similar in gender referring to declination classes, yet this similarity is only detectable in singular forms. In plural forms, the Russian language still exhibits declination classes, while Spanish alternates between two allophones “-s” and “-es”. If we analyze the results, though non-significant in the present sample, we still notice slightly higher accuracy on singular forms than plural forms, which suggests structural typology may play a role in number, as well. Despite our predictions, Mandarin speakers outperformed the English group and showed variation in their responses. Although in the first task they performed slightly better with the plural form, in Task 2, they produced more errors with plurals. Interestingly, the English group performed better with plural forms than singular forms on both tasks, which contradicts our initial hypothesis as we predicted the singular form would be treated as a default.

We also examined whether proficiency plays a role in the acquisition of gender agreement. Though we had a relatively small pool of participants, our results indicate that as proficiency level increases, accuracy increases as well. A Kruskal–Wallis H test indicated that Test 1 accuracy scores were significantly different between beginner Spanish learners, advanced Spanish learners, and native Spanish speakers (H (2) = 40.554, p < 0.001). A pairwise comparisons revealed that the beginner learners’ accuracy scores were significantly lower than the native Spanish controls (p < 0.01) and the advanced learners (p < 0.01), and that there was no significant difference between the advanced learners and the native controls (p = 1.000). This is also true for Task 2 accuracy scores; the Test 2 accuracy scores are significantly different between beginner Spanish learners, advanced Spanish learners, and native Spanish speakers (H(2) = 34.137, p < 0.001). Pairwise comparisons revealed the beginner learners’ accuracy scores are significantly lower than the native Spanish controls (p < 0.01) and the advanced learners (p < 0.01), and that there was no statistically significant difference between the advanced learners and the native controls (p = 1.000) (Appendix B). Therefore, in our study, our advanced participants performed at or near ceiling, which is similar to the results of the native speaker control group, closely aligning with previous research (e.g., Montrul et al. 2008; McCarthy 2008). All Russian learners aligned closely with the control group, whereas the other two groups produced some errors with more difficult forms, as initially predicted. Mandarin advanced learners showed more errors than the other two groups, with feminine, non-canonical, plural forms, similar to McCarthy’s conclusions that even advanced speakers encounter problems with some forms and by default overgeneralize one form, such as masculine. Nonetheless, L1 Mandarin and L1 English groups exhibited accuracy scores above chance-level, indicating that their acquisition of the grammatical gender feature in L3 Spanish is underway.

Since this project is ongoing, future work will be needed. First, it will be crucial to include a larger pool of participants for inferential analysis in order to determine to what extent the patterns uncovered here may be generalizable to the broader L3 learner population. We also believe it is important to include mirror-image groups, such as L1English-L2Mandarin/L2Russian-L3 Spanish in order to tease apart order of acquisition from other factors (e.g., typology, type of acquisition, etc.) (see Rothman 2011; Puig-Mayenco et al. 2020) In his study on L3 Brazilian Portuguese (BP) word order and relative clause attachment acquisition, Rothman studied and compared mirror-image groups, namely Spanish (L1)–English (L2) learners of BP (L3) and L1 English (L1)–L2 Spanish (L2)–(L3) learners, of BP (L3), and found that L1 and L2 transfer macro-variables were not counted as positive, since Spanish was transferred in both groups, which suggested that L1 or L2 transfer is not an absolute default and, in the case of L3 BP learners, the results suggest the effect of typological primacy rather than the order of acquisition.

Furthermore, an analysis of the effect of noun frequency in the input learners receive would likely yield interesting results as learners may be more likely to acquire–and to a greater degree of accuracy–the grammatical gender assignment of nouns frequently encountered in the linguistic environment. Although for the present study only target nouns found in the studied chapters of the beginner course textbook were included, there is likely to be some differences in their relative frequencies in both the textbook and course lectures and tutorial materials. Finally, it will also be crucial to analyze other individual variables, including language history, use, proficiency (both self-report and through testing), and attitudes, which could potentially influence performance with grammatical gender as well as the degree of transfer from other languages known. These factors constitute important avenues of future research that this ongoing project has uncovered and endeavors to explore further.

In conclusion, this study provides new insights into the L3 acquisition of grammatical gender. To our knowledge, the Mandarin-Russian-English-Spanish language pairing has not been previously studied, and this particular choice of languages both with (Russian, Spanish) and without (Mandarin, English) an explicit grammatical gender system has yielded some interesting results which merit further research. On the one hand, the Russian group performed better than the other two groups, which suggests that participants whose L1 has the gender feature available in their linguistic repertoire will be more accurate as they can transfer to some extent this feature. On the other hand, language environment and L1 and L2 use can also affect performance, which means that it will be important to assess participants’ daily language use to better understand and further explain the results.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, O.T.; methodology, O.T., M.B. and Q.W.; software, Q.W.; validation, O.T., M.B. and Q.W.; formal analysis, O.T., M.B. and Q.W.; investigation, O.T., M.B., Q.W. and K.B.; resources, O.T., M.B., Q.W. and K.B.; data curation, M.B., Q.W., K.B. and O.T.; writing—original draft preparation, O.T.; writing—review and editing, O.T., M.B., Q.W. and K.B.; visualization, Q.W.; supervision, O.T.; project administration, O.T.; funding acquisition, O.T. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by Faculty Research Developmental Fund from Western University and SSHRC–Seed Grant.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki, and approved by the Ethics Committee of Western University, Canada (protocol code: 116433 and date of approval: 5 November 2020).

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

Data of current participants is unavailable due to privacy and ethical restrictions.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Appendix A

Table A1.

Paired Samples Statistics table.

Table A1.

Paired Samples Statistics table.

| Paired Samples Statistics | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean | N | Std. Deviation | Std. Error Mean | ||

| Pair 1 | Task 1 accuracy scores (%) | 72.4997 | 40 | 24.49286 | 3.87266 |

| Task 2 accuracy scores (%) | 79.8952 | 40 | 13.03610 | 2.06119 | |

Table A2.

Paired Samples Test table.

Table A2.

Paired Samples Test table.

| Paired Samples Test | ||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Paired Differences | t | df | Significance | |||||||

| Mean | Std. Deviation | Std. Error Mean | 95% Confidence Interval of the Difference | One-Sided p | Two-Sided p | |||||

| Lower | Upper | |||||||||

| Pair 1 | Task 1 accuracy scores (%)–Task 2 accuracy scores (%) | −7.39550 | 21.25636 | 3.36093 | −14.19361 | −0.59739 | −2.200 | 39 | 0.017 | 0.034 |

Appendix B

Table A3.

Kruskal–Wallis Test result for Task 1.

Table A3.

Kruskal–Wallis Test result for Task 1.

| Independent-Samples Kruskal–Wallis Test Summary | |

|---|---|

| Total N | 55 |

| Test Statistic | 40.554 a |

| Degree Of Freedom | 2 |

| Asymptotic Sig. (2-sided test) | <0.001 |

a. The test statistic is adjusted for ties.

Table A4.

Pairwise Comparisons table for Task 1.

Table A4.

Pairwise Comparisons table for Task 1.

| Pairwise Comparisons of Spanish Proficiency Level | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sample 1-Sample 2 | Test Statistic | Std. Error | Std. Test Statistic | Sig. | Adj. Sig. a |

| Beginner-Advanced | −25.783 | 4.940 | −5.220 | <0.001 | 0.000 |

| Beginner-Native | 28.517 | 5.704 | 5.000 | <0.001 | 0.000 |

| Advanced-Native | 2.733 | 6.377 | 0.429 | 0.668 | 1.000 |

Each row tests the null hypothesis that the Sample 1 and Sample 2 distributions are the same. Asymptotic significances (2-sided tests) are displayed. The significance level is 0.050. a. Significance values have been adjusted by the Bonferroni correction for multiple tests.

Table A5.

Kruskal–Wallis Test result for Task 2.

Table A5.

Kruskal–Wallis Test result for Task 2.

| Independent-Samples Kruskal–Wallis Test Summary | |

|---|---|

| Total N | 55 |

| Test Statistic | 34.137 a |

| Degree Of Freedom | 2 |

| Asymptotic Sig. (2-sided test) | <0.001 |

a. The test statistic is adjusted for ties.

Table A6.

Pairwise Comparisons table for Task 2.

Table A6.

Pairwise Comparisons table for Task 2.

| Pairwise Comparisons of Spanish Proficiency Level | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sample 1-Sample 2 | Test Statistic | Std. Error | Std. Test Statistic | Sig. | Adj. Sig. a |

| Beginner-Advanced | −24.617 | 5.007 | −4.916 | <0.001 | 0.000 |

| Beginner-Native | 25.683 | 5.782 | 4.442 | <0.001 | 0.000 |

| Advanced-Native | 1.067 | 6.464 | 0.165 | 0.869 | 1.000 |

Each row tests the null hypothesis that the Sample 1 and Sample 2 distributions are the same. Asymptotic significances (2-sided tests) are displayed. The significance level is 0.050. a. Significance values have been adjusted by the Bonferroni correction for multiple tests.

Notes

| 1 | Please note, for our current project, we are only analyzing the nouns that are neither gender-ambivalent nor gender-ambiguous. We also do not analyze the words that represent homophonous pairs. |

| 2 | Though we did not test proficiency in English, we can confirm that our L3 participants were highly proficient in English. All our Russian advanced participants completed their University degrees in Canada; all five of them hold PhDs in fields, including linguistics, literature, and psychology. Four of our advanced Mandarin participants completed their high school education in Canada; most of them were fourth year students at Western University. Our fifth participant holds Masters in English from China and was completed his Masters in Hispanic Linguistics at the time of the recruitment. Regarding our beginner learners, 9/10 of Russian participants completed high school in Canada and were first year students at Western. One participant was an international student who completed her first year at Western, lived in Canada for 2.5 years and scored highly on IELTS. Regarding our Chinese beginner participants, majority of them were international students who got admitted to Western according to IELTS scoring; they resided in Canada for at least 1.5–2 years and were studying their bachelor degrees in English. |

| 3 | In Canada, French is a mandatory subject until Grade 10. Participants were excluded from the study if they studied in French immersion school, if they took French until Grade 12 or if they were taking French at the time of the recruitment. We included the participants who took French in middle school but never studied it since then. |

| 4 | For this paper, we only examine the two tasks. The other two tasks, as well as the finding from the sociolinguistic questionnaire will be analyzed and presented in the future. |

References

- Alarcón, Irma. 2009. The Processing of Gender Agreement in L1 and L2 Spanish: Evidence from Reaction Time Data. Hispania 92: 814–28. [Google Scholar]

- Álvarez, Martínez, María Ángeles, and Ana Blanco Canales. 2008. Sueña 1. Libro del Alumno. Translated by Lei Wang. Beijing: Foreign Language Teaching and Research Press. [Google Scholar]

- Arias-Trejo, Natalia, Lisa M. Cantrell, Linda B. Smith, and Elda A. Alva Canto. 2014. Early comprehension of the Spanish plural. Journal of Child Language 41: 1356–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bardel, Camilla, and Ylva Falk. 2007. The role of the second language in third language acquisition: The case of Germanic syntax. Second Language Research 23: 459–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bardel, Camilla, and Ylva Falk. 2012. The L2 status factor and the declarative/procedural distinction. In Third Language Acquisition in Adulthood. Edited by J. Cabrelli Amaro, S. Flynn and J. Rothman. Philadelphia: John Benjamins, pp. 61–78. [Google Scholar]

- Barner, David, Thalwitz Dora, Wood Justin, Yang Shu-Ju, and Carey Susan. 2007. On the relation between the acquisition of singular-plural morpho-syntax and the conceptual distinction between one and more than one. Developmental Science 10: 365–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bas, Aarts, and April McMahon. 2006. The Handbook of English Linguistics. Oxford: Blackwell Pub. [Google Scholar]

- Bergen, John J. 1978. A Simplified Approach for Teaching the Gender of Spanish Nouns. Hispania 61: 865. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Birdsong, David, Libby M. Gertken, and Mark Amengual. 2012. Bilingual Language Profile: An Easy-to-Use Instrument to Assess Bilingualism. Austin, TX: COERLL, University of Texas at Austin. Available online: https://sites.la.utexas.edu/bilingual/ (accessed on 1 November 2022).

- Blanco, Jose, and Philip Redwine Donley. 2020. Vista Higher Learning, 6th ed. Boston: Vista Higher Learning. [Google Scholar]

- Boloh, Yves, and Laure Ibernon. 2010. Gender attribution and gender agreement in 4- to 10-year-old French children. Cognitive Development 25: 1–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bruhn de Garavito, Joyce, and Lydia White. 2002. The second language acquisition of Spanish DPs: The status of grammatical features. In The Acquisition of Spanish Morphosyntax. Studies in Theoretical Psycholinguistics. Edited by A. T. Pérez-Leroux and J. M. Liceras. Dordrecht: Springer, vol 31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cai, Hansong, and Luna Jing Cai. 2015. An Exploratory Study of the Role of L1 Chinese and L2 English in the Cross-Linguistic Influence in L3 French. International Journal of Language Studies 9: 1–30. [Google Scholar]

- Cenoz, Jasone. 2003. The Additive Effect of Bilingualism on Third Language Acquisition: A Review. International Journal of Bilingualism 7: 71–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Corbett, Greville. 1982. Gender in Russian: An account of gender specification and its relationship to declension. Russian Linguistics 6: 197–232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Corbett, Greville. 1991. Gender. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Corbett, Greville, and Norman Fraser. 1999. Default genders. In Gender in Grammar and Cognition. Edited by Barbara Unterbeck, Matti Rissanen, Terttu Nevalainen and Mirja Saari. I. Approaches to Gender. Berlin: Mouton de Gruyter, pp. 55–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Falk, Ylva, and Camilla Bardel. 2011. Object pronouns in German L3 syntax: Evidence for the L2 status factor. Second Language Research 27: 59–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farris, Catherine S. 1988. Gender and Grammar in Chinese: With Implications for Language Universals. Modern China 14: 277–308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Flynn, Suzanne, Foley Claire, and Inna Vinnitskaya. 2004. The Cumulative-Enhancement Model for Language Acquisition: Comparing Adults’ and Children’s Patterns of Development in First, Second and Third Language Acquisition of Relative Clauses. International Journal of Multilingualism 1: 3–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Foote, Rebecca. 2009. Transfer in L3 Acquisition: The Role of Typology. In Third Language Acquisition and Universal Grammar. Bristol and Blue Ridge Summit: Multilingual Matters, pp. 89–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gamboa Rengifo, Arnold. 2012. The Acquisition of Grammatical Gender in Spanish by English-Speaking L2 Learners. West Lafayette: Purdue University. [Google Scholar]

- Gvozdev, Aleksandr N. 1961. Formirovanie u Rebenka Grammatičeskogo Stroja Russkogo Jazyka. [Language Development of a Russian Child]. Moscow: APN RSFSR. [Google Scholar]

- Hammarberg, Björn. 2001. Roles of L1 and L2 in L3 Production and Acquisition. In Cross-Linguistic Influence in Third Language Acquisition: Psycholinguistic Perspectives. Edited by J. Cenoz, B. Hufeisen and U. Jessner. Clevedon: Multilingual Matters, pp. 21–41. [Google Scholar]

- Harris, James W. 1991. The exponence of gender in Spanish. Linguistic Inquiry 22: 27–62. [Google Scholar]

- Hawkins, Roger, and Florencia Franceschina. 2004. Explaining the acquisition and non-acquisition of determiner–noun gender concord in French and Spanish. Language Acquisition and Language Disorders 32: 175–206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hermas, Abdelkader. 2010. Language acquisition as computational resetting: Verb movement in L3 initial state. International Journal of Multilingualism 7: 343–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hernandez Piña, Fuensanta. 1984. Teorías psicosociolingüísticas y su aplicación a la adquisición del español como lengua materna. Madrid: Siglo XXI. [Google Scholar]

- Huang, Cheng-Teh James, Yen-hui Audrey Li, and Yafei Li. 2009. The Syntax of Chinese. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, pp. 214–17, 283–84. [Google Scholar]

- Huddleston, Rodney, and Geoffrey Pullum. 2002. The Cambridge Grammar of the English Language. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- IBM Corp. 2021. IBM SPSS Statistics for Windows, Version 28.0. Armonk: IBM Corp. [Google Scholar]

- Kong, Stano. 2015. L3 Initial State: Typological Primacy Driven, L2 Factor Determinded, or L1 Feature Oriented? Taiwan Journal of Linguistics 13: 79–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kouider, Sid, Halberda Justin, Wood Justin, and Susan Caren. 2006. Acquisition of English number marking: The singular-plural distinction. Language Learning and Development 2: 1–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leung, Yan-Kit Ingrid. 2005. L2 Vs. L3 Initial State: A Comparative Study of the Acquisition of French DPs by Vietnamese Monolinguals and Cantonese–English Bilinguals. Bilingualism 8: 39–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leushina, Anna M. 1991. The development of children’s first mathematical knowledge of sets, number, and counting. In The Development of Elementary Mathematical Concepts in Preschool Children. Edited and Translated by L. P. Steffe. Reston and Virginia: National Council of Teachers of Mathematics, pp. 1–50. First published 1974. [Google Scholar]

- Li, Charles, and Sandra Annear Thompson. 1981. Mandarin Chinese: A Functional Reference Grammar. Berkeley: University of California Press, pp. 11–12. [Google Scholar]