Squaring the Circle of Alternative Assessment in Distance Language Education: A Focus on the Young Learner

Abstract

:1. Introduction

- To collect data via digital tools that focus on vocabulary and spelling in a meaningful context.

- To collect data via digital feedback.

- To observe the students’ progress and learning approach to the newly introduced tools and mode of learning.

- To analyze findings during a child-friendly assessment process.

- RQ1.

- To what extent do YLs progress in addition to mastering the core challenges of spelling skills and vocabulary development through online learning environments?

- RQ2.

- How can the process of alternative assessment facilitate assessment and evaluation in the YL’s online environment?

- RQ3.

- What are children’s attitudes toward alternative forms of assessment during unprecedented times and lockdown?

1.1. Background Review

1.2. Emergency Remote Teaching and Assessment

1.3. Alternative Assessment Online

1.4. The Context

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Participants

2.2. Data Collection Tools

2.3. Data Collection Process

- Step 1:

- The researcher created an observation scheme for the study.

- Step 2:

- There was a selection of the participants of the research.

- Step 3:

- The researcher visited the online class, sitting from the beginning to the end of the session, taking notes of the assessment process. The classes were observed as carefully as possible. The researcher was given permission to record the sessions. The researcher’s camera and microphone were switched off to avoid validity threats.

- Step 4:

- The students were interviewed.

- Step 5:

- After the preliminary data collection from both observation and interview, the data was analyzed.

2.4. Data Analysis

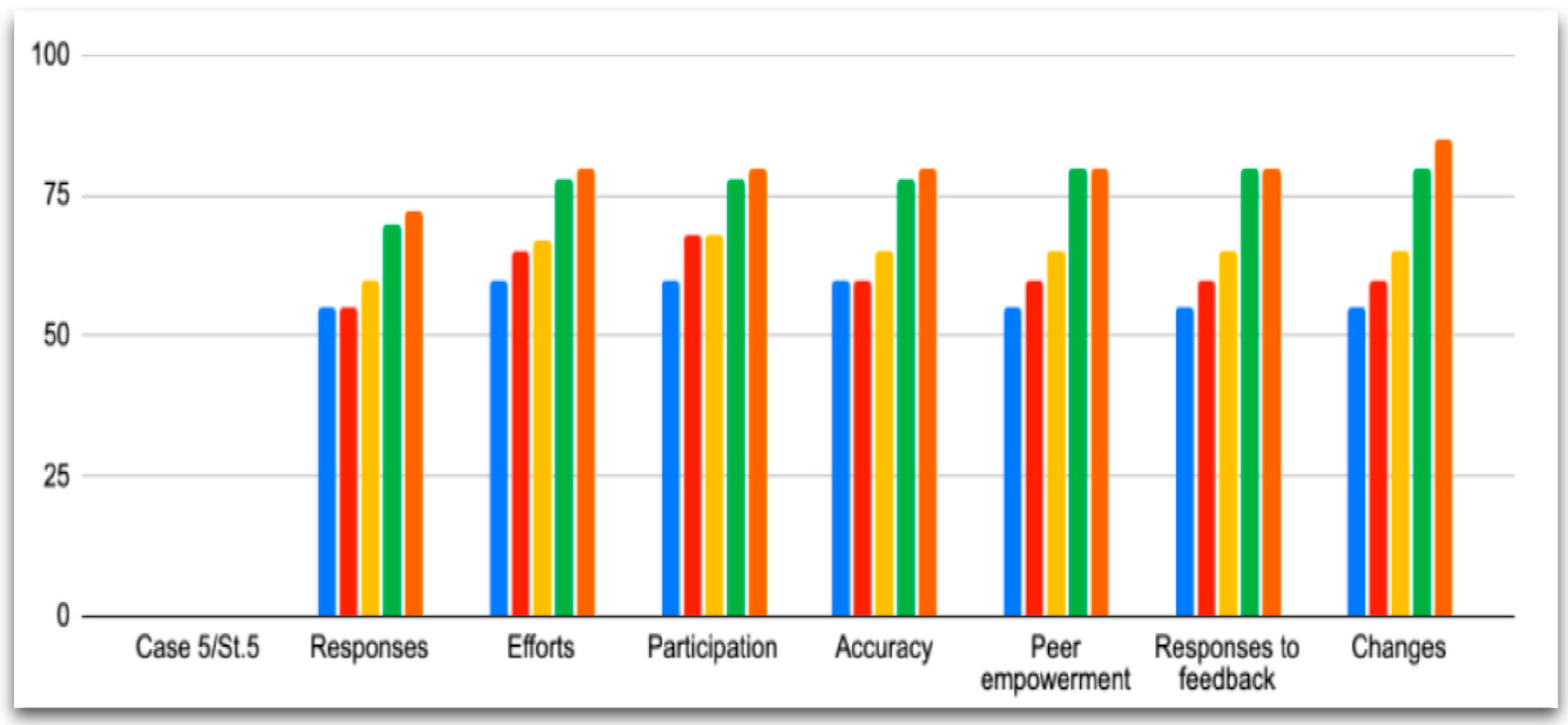

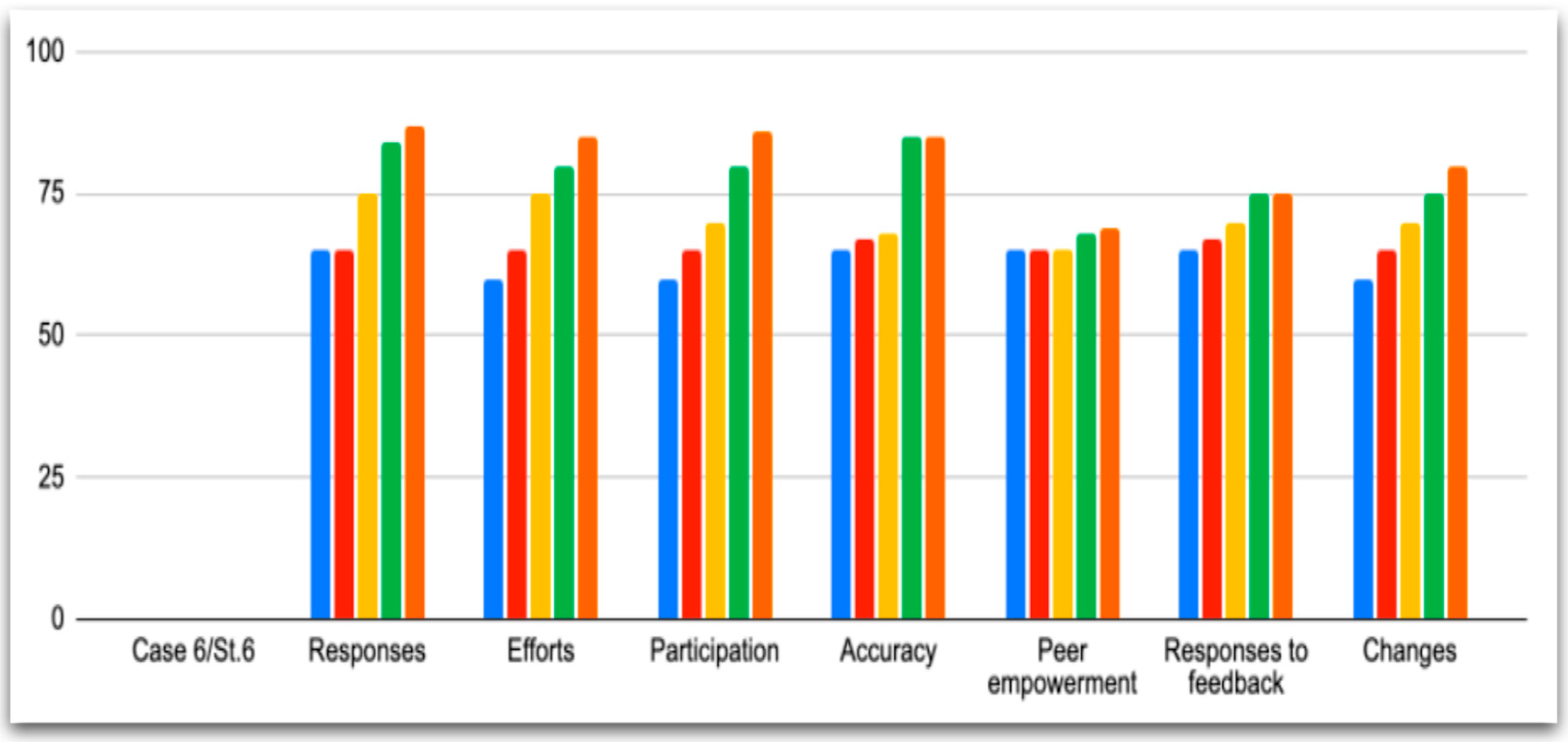

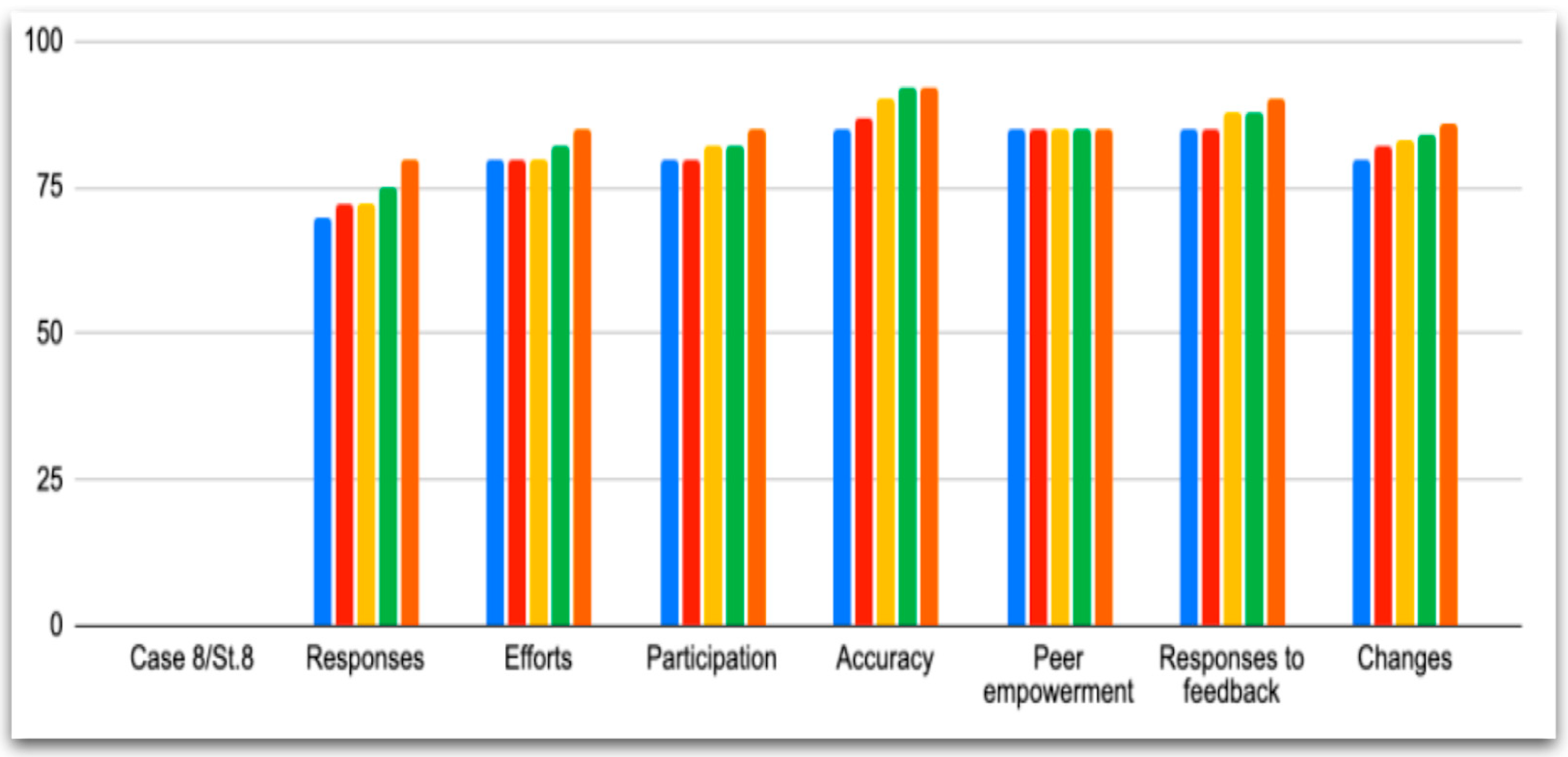

- Responses;

- Efforts;

- Accuracy;

- Participation;

- Peer empowerment;

- Reactions to feedback;

- Changes.

- Impressions and attitude towards online alternative assessment;

- Equipment/digital tools;

- Vocabulary comprehension;

- Feedback needs;

- Spelling logic.

3. Results

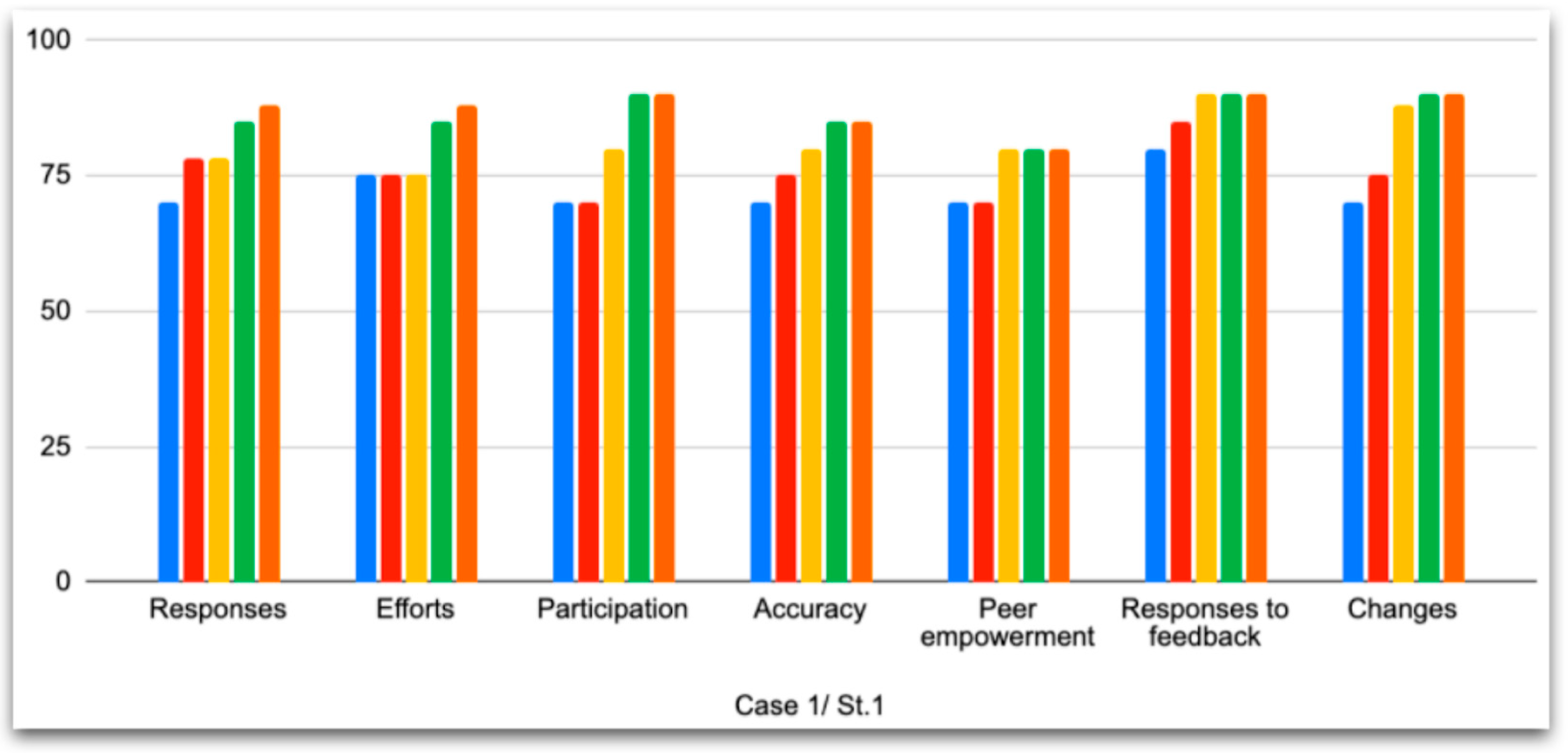

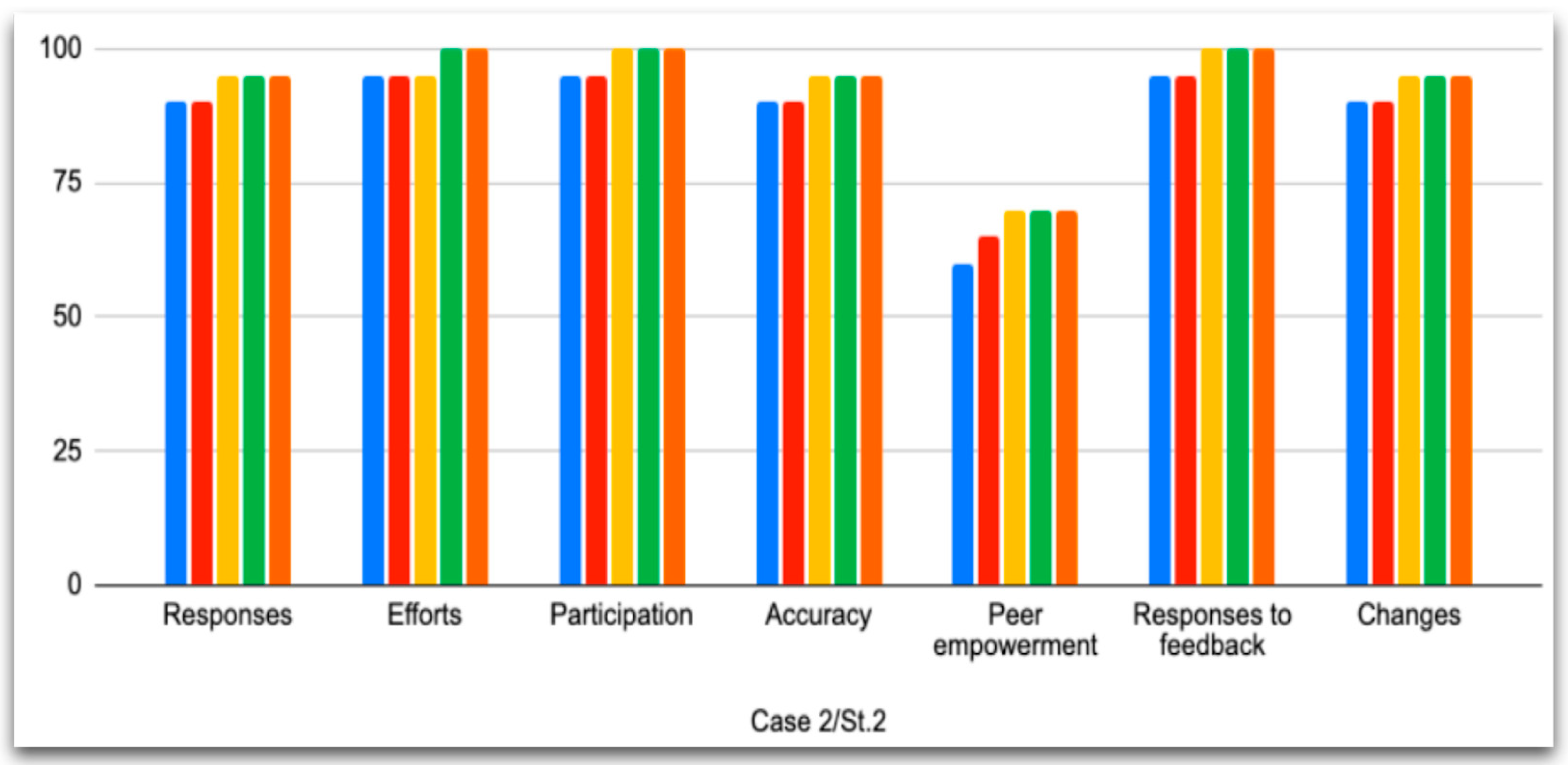

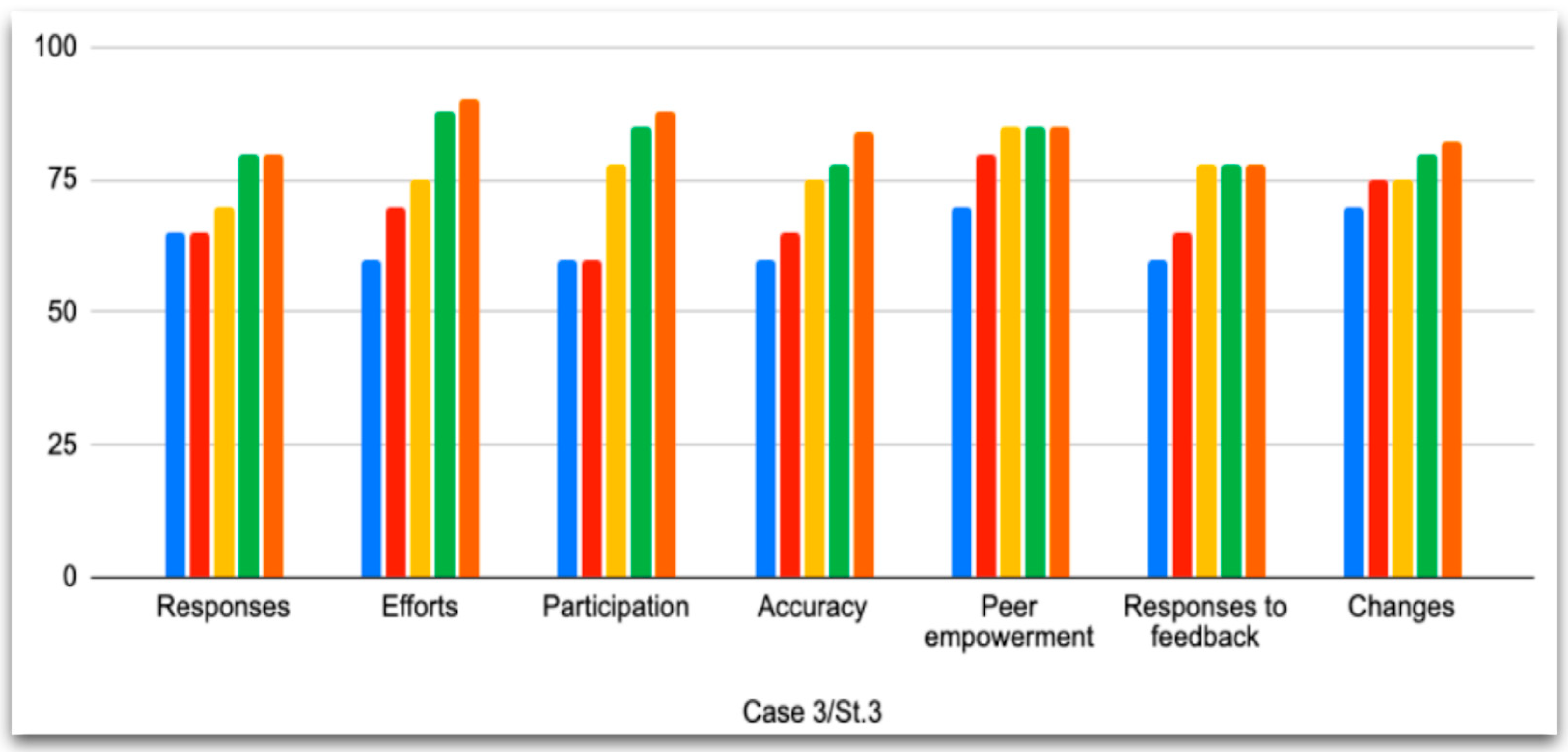

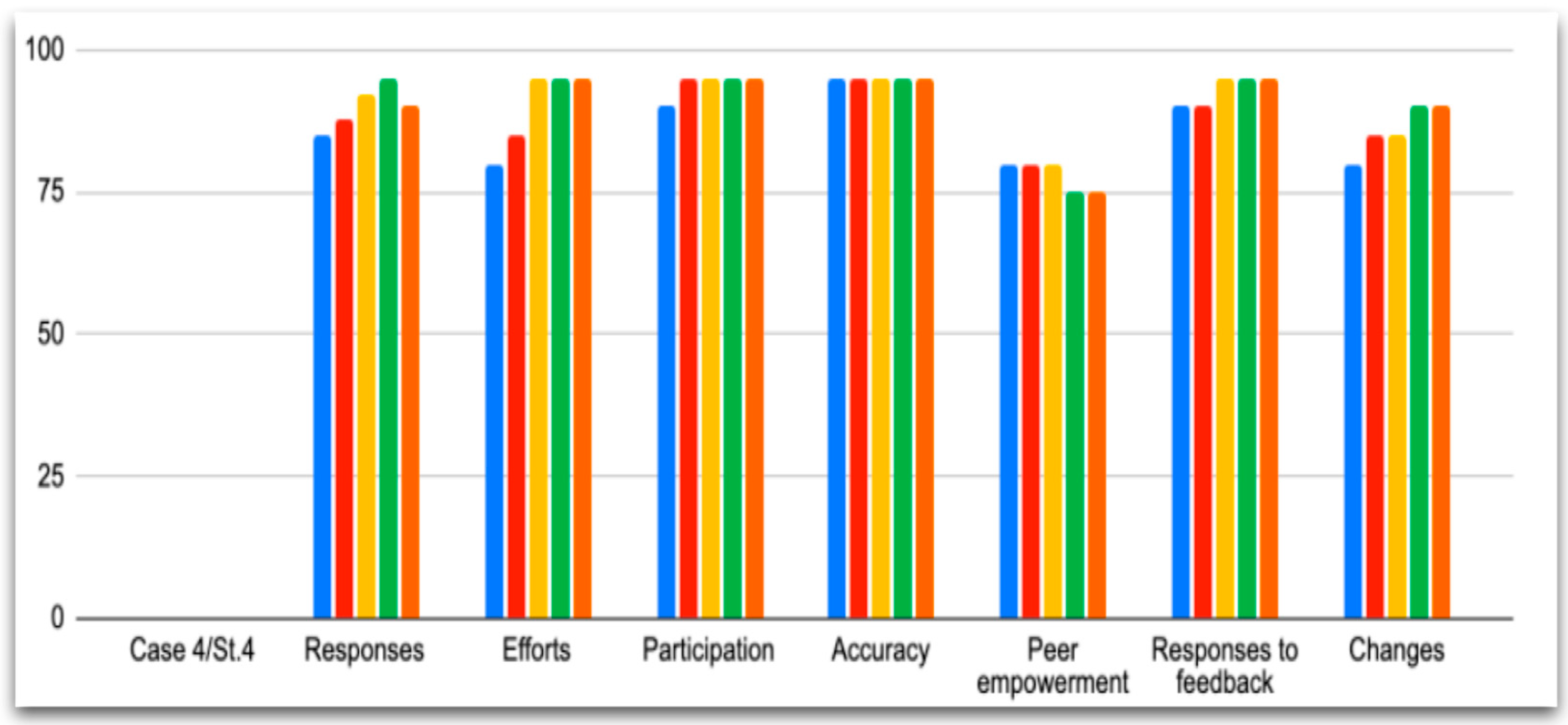

3.1. Observation Findings

3.2. Interview Findings

3.2.1. Impressions and Attitude towards Online Alternative Assessment

3.2.2. Equipment/Digital Tools

3.2.3. Vocabulary Comprehension

3.2.4. Feedback Needs

3.2.5. Spelling Logic

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

- How do you feel about learning English online?

- Do you have the equipment to learn English online?

- Do you like the spelling and vocabulary activities you do?

- Does it feel like you are being assessed?

- Which activities were your favorite?

- Can you spell the words: lucky, ice-cream, friends, helicopter, tunnel, out of, London, tourist

- Why do you think you did so well?/didn’t do so well?

References

- Alexiou, Thomaï, and Marina Mattheoudakis. 2011. Bridging the gap: Issues of transition and continuity from primary to secondary schools in Greece. In 23rd International Symposium Papers on Theoretical and Applied Linguistics—Selected Papers. Thessaloniki: School of English, Aristotle University of Thessaloniki. [Google Scholar]

- Allwright, Dick R. 1988. Observation in the Language Classroom. London: Longman. [Google Scholar]

- Bailey, Kathleen. 1998. Learning about Language Assessment: Dilemmas, Decisions, and Directions. Boston: Heinle & Heinle. [Google Scholar]

- Barootchi, Nasrin, and Mohammad Hosein Keshavarz. 2002. Assessment of achievement through portfolios and teacher-made tests. Educational Research 44: 279–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bozkurt, Aras, and Ramesh C. Sharma. 2020. Emergency remote teaching in a time of global crisis due to CoronaVirus pandemic. Asian Journal of Distance Education 15: i–vi. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bray, Mark. 2011. The Challenge of Shadow Education: Private Tutoring and Its Implications for Policy Makers in the European Union. Brussels: European Commission. [Google Scholar]

- Bray, Mark, and Chad Lykins. 2012. Shadow Education: Private Supplementary Tutoring and Its Implications for Policy Makers in Asia. Philippines: Asian Development Bank. [Google Scholar]

- Chung, Sun-Joo, and Lee-Jin Choi. 2021. The development of sustainable assessment during the COVID-19 pandemic: The case of the English language program in South Korea. Sustainability 13: 4499. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coombe, Christine, Vafadar Hossein, and Mohebbi Hassan. 2020. Language assessment literacy: What do we need to learn, unlearn, and relearn? Lang Test Asia 10: 3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Creswell, John W., and Vicki L. Plano-Clark. 2007. Designing and Conducting Mixed Methods Research. Thousand Oaks: SAGE Publications. [Google Scholar]

- Donitsa-Schmidt, Smadar, Ofra Inbar, and Elana Shohamy. 2004. The effects of teaching spoken Arabic on students’ attitudes and motivation in Israel. Modern Language Journal 88: 218–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferri, Fernando, Patrizia Grifoni, and Tiziana Guzzo. 2020. Online Learning and Emergency Remote Teaching: Opportunities and Challenges in Emergency Situations. Societies 10: 86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Forrester, Adam. 2020. Addressing the challenges of group speaking assessments in the time of the Coronavirus. International Journal of TESOL Studies 2: 74–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghanbari, Nasim, and Sima Nowroozi. 2021. The practice of online assessment in an EFL context amidst COVID-19 pandemic: Views from teachers. Language Testing Asia 11: 27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giannikas, Christina N. 2013. The benefits of management and organisation: A case study in a young learners' classroom. CEPS Journal 3: 87–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giannikas, Christina N. 2020. Prioritizing when Education is in Crisis: The language teacher. Humanising Language Teaching 22: 1755–9715. [Google Scholar]

- Hansen, Anders. 1998. Content Analysis. In Mass Communication Research Methods. Edited by Anders Hansen, Simon Cottle, Ralph M. Negrine and Chris Newbold. Thousand Oaks: SAGE Publications, pp. 91–129. [Google Scholar]

- Hasselgreen, Angela. 2005. Assessing the Language of Young Learners. Language Testing 22: 337–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hodges, Charles, Stephanie Moore, Barbara Lockee, Torrey Trust, and Mark Bond. 2020. The Difference Between Emergency Remote Teaching and Online Learning. EDUCAUSE Review. Available online: https://er.educause.edu/articles/2020/3/the-difference-between-emergency-remote-teaching-and-online-learning (accessed on 12 August 2020).

- Holmes, Bryn, and John Gardner. 2006. E-Learning Concepts and Practice. London: SAGE Publications. [Google Scholar]

- International Dyslexia Association. 2011. Spelling [Fact Sheet]. Available online: https://app.box.com/s/phcrmtjl4uncu6c6y4qmzml8r41yc06r (accessed on 6 July 2021).

- Ioannou-Georgiou, Sophie, and Pavlos Pavlou. 2003. Assessing Young Learners. Oxford: Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Janisch, Carole, Xiaoming Liu, and Amma Akrof. 2007. Implementing Alternative Assessment: Opportunities and Obstacles. The Educational Forum 71: 221–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Karavas, Evdokia. 2014. Developing an online distance training programme for primary EFL teachers in Greece: Entering a brave new world. Research Papers in Language Teaching and Learning 5: 70–86. [Google Scholar]

- Mckay, Penny. 2006. Assessing Young Language Learners. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Merriam, Sharan B. 2009. Qualitative Research: A Guide to Design and Implementation. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass. [Google Scholar]

- Mohmmed, Abdallelah O., Basim A. Khidhir, Abdul Nazeer, and Vigil J. Vijayan. 2020. Emergency remote teaching during Coronavirus pandemic: The current trend and future directive at Middle East College Oman. Innovative Infrastructure Solutions 5: 72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ridgway, Jim, Sean Mccusker, and Daniel Pead. 2004. Literature Review of E-Assessment. Bristol: NESTA Futurelab. [Google Scholar]

- Robson, Colin. 2002. Read-World Research, 2nd ed. Oxford: Blackwell. [Google Scholar]

- Schleicher, Andreas. 2020. The Impact of COVID-19 on Education: Insights from Education at a Glance 2020. Paris: OECD, Available online: https://www.oecd.org/education/the-impact-of-covid-19-on-education-insights-education-at-a-glance-2020.pdf (accessed on 10 August 2021).

- Shaaban, A. Karim. 2001. Assessment of Young Learners. FORUM 39: 16–23. [Google Scholar]

- Shepard, Lorrie A. 2000. The Role of Assessment in a Learning Culture. Educational Researcher 29: 4–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simonson, Michael, Sharon E. Smaldino, Michael Albright, and Susan Zvacek. 2000. Assessment for Distance Education. In Teaching and Learning at a Distance: Foundations of Distance Education. Hoboken: Prentice-Hall, chap. 11. [Google Scholar]

- Tarhini, Ali, Kate Hone, and Xiaohui Liu. 2013. Extending the TAM model to empirically investigate the students’ behavioural intention to use e-learning in developing countries. Paper presented at Science and Information Conference, London, UK, October 7–9; pp. 732–37. [Google Scholar]

- Taylor, J. Steven, Robert Bogdan, and Marjorie DeVault. 2015. Introduction to Qualitative Research Methods A Guidebook and Resource, 4th ed. London: John Wiley & Sons. [Google Scholar]

- Tsagari, Dina. 2011. Investigating the ‘assessment literacy’ of EFL state school teachers in Greece. In Classroom-Based Language Assessment. Edited by Dina Tsagari and Ildikó Csépes. Berlin: Peter Lang Verlag, pp. 169–90. [Google Scholar]

- Tsagari, Dina, and Christina Nicole Giannikas. 2017. To L1 or not to L1, that is the question: Research in young learners’ foreign language classroom. English Language Education Policies and Practices in the Mediterranean Countriesand Beyond 11: 131–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsagari, Dina, and Christina Nicole Giannikas. 2018. Re-evaluating the use of L1 in the Second Language Classroom: Students vs. teachers. Applied Linguistics Review 11: 151–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsagari, Dina, and Egli Georgiou. 2016. Use of Mother Tongue in Second Language Learning: Voices and Practices in Private Language Education In Cyprus. Mediterranean Language Review 23: 101–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, Wen. 2021. Pedagogic Practices, Student Engagement and Equity in Chinese as a Foreign Language Education. In Australia and Beyond, 1st ed. London: Routledge. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Jingshun, Eunice Jang, and Saad Chahine. 2021. A systematic review of cognitive diagnostic assessment and modeling through concept mapping. Frontiers of Contemporary Education 2: 10–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Renyi, Yixin Li, Annie L. Zhang, Yuan Wang, and Mario J. Molina. 2020. Identifying airborne transmission as the dominant route for the spread of COVID-19. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America 117: 14857–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Featured Assessed | Assessment Activity | Form of Execution |

|---|---|---|

| Self-Assessment | Quizzes | Synchronous and Asynchronous |

| Review of Vocabulary | Use of surrounding while on online platform | Synchronous |

| Use of Vocabulary | Student recordings | Synchronous and Asynchronous |

| Vocabulary understanding | Misconception checks | Synchronous |

| Developing assessment and providing feedback skills | Peer Assessment | Synchronous |

| Feature Assessed | Assessment Activity | Form of Executions |

|---|---|---|

| Self-assessment and spelling logic | Spelling quizzes | Synchronous and Asynchronous |

| Memory recall and spelling aloud | Spelling online games | Synchronous |

| Word identification and spelling memory | Trace-write-remember | Asynchronous |

| Vocabulary understanding | Sound-it-out | Synchronous |

| Developing assessment and providing feedback skills | Peer assessment | Synchronous |

| Themes | Illustrations | Data Collected |

|---|---|---|

| Responses → | To assessment activities → | -Figures that emerged from automated feedback -Instances noted during observations when automated feedback was not available |

| Efforts → | To complete and succeed during the assessment process → | -Number of questions asked -Number of possible responses -Number of self-correction |

| Accuracy → | In spelling and vocabulary activities → | -Figures that emerged from automated feedback -Instances noted during observations when automated feedback was not available |

| Participation → | Willingness to participate → | -Instances noted during observations when automated feedback was not available |

| Peer empowerment → | Working together/fair and valid peer assessment/peer encouragement → | -Instances noted in Observation Sheets -Instances of requests from students to work together -Instances of requests from students to work alone -Number of activities/content/automated feedback/peer feedback according to teacher guidelines |

| Reactions to feedback → | From teacher and peers → | -Instances noted in Observation Sheets -Figures that emerged from automated feedback -Instances noted during observations when automated feedback was not available |

| Changes → | In the students’ approach to the spelling and vocabulary assessment activities → | -Instances noted in Observation Sheets |

| Cases | Spelling of: ‘Lucky’ | Spelling of: ‘Ice-Cream’ | Spelling of: ‘Friends’ | Spelling of: ‘Helicopter’ | Spelling of: ‘Tunnel’ | Spelling of: ‘Out of’ | Spelling of: ‘London’ | Spelling of: ‘Tourist’ |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| C1 | luky | ice-cream | freinds | helicopter | tunel | Out of | London | tourist |

| C2 | lucky | ice-cream | friends | helicopter | tunel | Out of | London | tourist |

| C3 | lucky | ice-cream | frends | helikopter | tunnel | Out of | London | turist |

| C4 | lucky | ice-cream | friends | helikopter | tunnel | Out of | London | tourist |

| C5 | luky | ice-cream | no response | no response | no response | Out of | Lon | turist |

| C6 | lucky | ice-cream | friends | helicopter | tunnel | Out of | London | turist |

| C7 | lucky | ice-cream | freinds | helicopter | tunel | Aut of | London | tourist |

| C8 | luky | ice-cream | friends | helikopter | tunnel | Out of | London | tourist |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Giannikas, C.N. Squaring the Circle of Alternative Assessment in Distance Language Education: A Focus on the Young Learner. Languages 2022, 7, 121. https://doi.org/10.3390/languages7020121

Giannikas CN. Squaring the Circle of Alternative Assessment in Distance Language Education: A Focus on the Young Learner. Languages. 2022; 7(2):121. https://doi.org/10.3390/languages7020121

Chicago/Turabian StyleGiannikas, Christina Nicole. 2022. "Squaring the Circle of Alternative Assessment in Distance Language Education: A Focus on the Young Learner" Languages 7, no. 2: 121. https://doi.org/10.3390/languages7020121

APA StyleGiannikas, C. N. (2022). Squaring the Circle of Alternative Assessment in Distance Language Education: A Focus on the Young Learner. Languages, 7(2), 121. https://doi.org/10.3390/languages7020121