Ghosting, Breadcrumbing, Catfishing: A Corpus Analysis of English Borrowings in the Spanish Speaking World

Abstract

:1. Introduction

- According to the number of occurrences of the borrowings, to what extent are these loanwords used in the Spanish language?

- In terms of their graphic representation, how assimilated and adapted are these words?

- When did these words (with their new romantic meaning) first appear in the Corpus NOW?

- How often are these terms implemented in each of the 21 Spanish-speaking countries?

2. Review of Literature

2.1. English as a Universal Language and Language Contact

2.2. Linguistic Borrowings

2.3. Borrowings in Online Resources

2.4. Corpus Linguistics

3. Methodology

3.1. The Data

- Ghosting: Ignoring the person until they become aware that things have ended

- Haunting: Disappearing like ghosting, but still watching activity on social media

- Caspering: Rejecting someone politely (the friendly form of ghosting)

- Zombieing: Someone who has ghosted you and then suddenly returns to your life through social media.

- Gaslighting: Making a person doubt their own sanity in order to control them.

- Catfishing: Creating a completely new identity (often referring to online environments) to start a relationship.

- Kittenfishing: Emphasizing the good and understating the bad to start a relationship

- Cockfishing: Sending a photo of a penis that is not yours, altering it in Photoshop or taking a photo that does not accurately portray reality, (derivative of Catfishing)

- Cookie-jarring: Going out with a person only because you are bored

- Cuffing: Going out with someone because it is Winter, and you miss having someone to curl up and watch Netflix with or someone to ease the stress of Christmas dinner with Grandma

- Fielding: Analyzing the field to see who the best players are, or playing the field (opposite of cuffing)

- Pocketing: Your partner is good to you when you are alone, but they keep you hidden away from friends or family.

- Fleabagging: Going out with people who are not good for you over and over again. This comes from the show Fleabag (2016), where the main character repeatedly makes bad relationship choices.

- Orbiting: Dedicating yourself to giving likes to all of someone’s posts and seeing all of their stories without ever talking directly to them.

- Curving: Veering away from romantic interest and advances (similar to ghosting)

- Breadcrumbing: Sending messages and flirting with someone but without the intention of developing anything.

- Benching: Maintaining interest of someone knowing that you will never end up together

- Cushioning: Entertaining options with other people when you have a partner with the idea that once your relationship ends you can cushion the fall.

- Paperclipping: Your ex returns to your life without the intention of anything happening, only to let you know that they are there. This concept is based on the animated icon from Word, “Clippy”, who appears at certain times to communicate a message from the program.

- Situationship: When you find yourself with the feeling of being in a relationship, but it is not official.

3.2. Instrument and Procedure

(1) Aunque por convenio social se sobreentiende que lo de ghostear solo se le puede hacer a alguien con quien nunca tuviste una relación sin compromiso.(Playground Magazine 23 January 2018)

4. Results

(1) El ghosting no es más que una manera cobarde de salir de una relación…(De10, México, 2017)

‘Ghosting is just a cowardly way of breaking up…’

(2) Es frecuente encontrar situaciones de gaslighting en relaciones tóxicas…(Wapa, Perú, 2019)

‘Gaslighting is a frequent practice in toxic relationships…’

(3) El punto de partida de el benching es el egoísmo, pues quien textea…(El Periódico Digital, Bolivia, 2018)

‘Benching is based on selfishness, since the one who texts…’

(4) Términos como “ghosting” o “zombing” remiten a nuevas estrategias…(La Prensa, Argentina, 2017)

‘Terms like “ghosting” or “zombing” refer to new strategies…’

(5) “Orbiting”, la nueva tendencia de relaciones en la red…(Meganoticias, Chile, 2018)

‘Orbiting, the new online love trend…’

(6) Los mensajes desaparecen y las llamadas sólo quedan en recuerdos, el “Ghosting” es conocido como una de las peores maneras de terminar una relación.(La Tribuna, Honduras, 2018)

(7) …estos comportamientos cobardes (el ghosting) y sádicos (el breadcrumbing)…(El Confidencial, España, 2017)

(8) También conocido como “Cuffing Season” (temporada de las esposas)…(El Nuevo Diario, Nicaragua, 2017)

‘Also known as “Cuffing Season” (the season of handcuffs)…’

(9) …el catfishing, que básicamente es crear perfiles falsos en redes sociales para enamorar…(BioBioChile, Chile, 2018)

‘…catfishing, which is basically creating fake profiles on social media to make someone fall in love with you…’

(10) …y ‘gaslighting’ (volver loco a alguien).(Noticia al Día, Venezuela, 2018)

‘…and “gaslighting” (drive somebody crazy).’

(11) …el breadcrumbing es un método de mantener el interés de el otro sin avanzartanto.(El Observador, Uruguay, 2019)

‘…and breadcrumbing is the strategy of keeping someone’s interest without taking any further steps.’

5. Discussion

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Alba, Orlando. 2007. Integración Fonética y Morfológica De Los Préstamos: Datos Del Léxico Dominicano Del Béisbol. RLA. Revista de lingüística teóRica Y Aplicada 45: 89–109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alfonso, Belén. 2020. Pocketing, Fleabagging, Ghosting: Qué significan Las Nuevas Palabras Que Se Usan Para Describir Las Relaciones. GQ España. Available online: https://www.revistagq.com/noticias/articulo/que-significan-palabras-que-definen-relaciones-tecnicismos-ghosting-catfishing-pocketing (accessed on 1 October 2020).

- Amador, María Vázquez, and M. Carmen Lario de Oñate. 2016. Los préstamos lingüísticos en la prensa del corazón: Estudio comparativo. In Beyond the Universe of Languages for Specific Purposes: The 21st Century Perspective. Madrid: Universidad de Alcalá, pp. 95–100. [Google Scholar]

- Bordelois, Ivonne. 2011. El País Que Nos Habla. Buenos Aires: Penguin Random House Grupo Editorial Argentina. [Google Scholar]

- Breva-Claramonte, Manuel. 1999. Pidgin traits in the adaptation process of spanish anglicisms. Cuadernos de Filología Inglesa 8: 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Callahan, Laura. 2004. Spanish/English Codeswitching in a Written Corpus. Amsterdam: John Benjamins Pub. [Google Scholar]

- Carballo, María Auxiliadora Castillo. 2006. El préstamo Lingüístico En La Actualidad. Los anglicismos. Madrid: Liceus, Servicios de Gestió. [Google Scholar]

- Costa, Rebeca Soler. 2009. Anglicismos léxicos en dos corpus. Espéculo Rev Estud Liter 42: 114. [Google Scholar]

- Davies, Mark. 2002. Corpus del Español: 100 Million Words, 1200s–1900s. Available online: http://www.corpusdelespanol.org (accessed on 1 September 2020).

- De la Cruz Cabanillas, Isabel, Guzmán Mancho Barés, and Cristina Tejedor Martínez. 2009. Análisis de un corpus de textos turísticos: La incorporación, difusión e integración de los préstamos ingleses en los textos turísticos. A Survey of Corpus-Based Research, 970–88. [Google Scholar]

- Fadic, Natalia Castillo. 2002. El préstamo léxico y su adaptación: Un problema lingüístico y cultural. Onomázein: Revista de Lingüística, Filología Y Traducción de la Pontificia Universidad Católica de Chile 7: 469–96. [Google Scholar]

- Field, Fredric W., and Bernard Comrie. 2002. Linguistic Borrowing in Bilingual Contexts. Amsterdam: J. Benjamins, vol. 62. [Google Scholar]

- Friginal, Eric, and Jack Hardy. 2014. Corpus-Based Sociolinguistics: A Guide for Students. New York and London: Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Garrido, Joaquín. 2010. Lengua y globalización: Inglés global y español pluricéntrico. Historia Y comunicacióN Social 15: 63–95. [Google Scholar]

- Giammatteo, Mabel, Patricia Gubitosi, and Alejandro Parini. 2018. La comunicación mediada por computadora. In El Español En La Red. Madrid: Iberoamericana Vervuert, pp. 11–26. [Google Scholar]

- González Cruz, María Isabel. 2017. Exploring the Dynamics of English/Spanish Codeswitching in a Written Corpus. Alicante: Revista Alicantina de Estudios Ingleses. [Google Scholar]

- Haspelmath, Martin. 2009. Lexical borrowing: Concepts and issues. In Loanwords in the World’S Languages: A Comparative Handbook. Berlin: Walter de Gruyter GmbH & Co. KG, pp. 35–54. [Google Scholar]

- Jonsson, Carla. 2010. Functions of code-switching in bilingual theater: An analysis of three Chicano plays. Journal of Pragmatics 42: 1296–310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, Carmen. 2016. Multilingual resources and practices in digital communication. In The Routledge Handbook of Language and Digital Communication. Abingdon: Routledge, pp. 118–32. [Google Scholar]

- Levendis, Katharine, and Andreea Calude. 2019. Perception and flagging of loanwords—A diachronic case-study of māori loanwords in new zealand english. Ampersand 6: 100056. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lewandowski, Theodor. 1982. Diccionario De Lingüística. Madrid: Cátedra. [Google Scholar]

- Lipski, John M. 1982. Spanish-English language switching in speech and literature: Theories and models. Bilingual Review/La Revista Bilingüe 9.3: 191–212. [Google Scholar]

- McEnery, Tony, and Andrew Hardie. 2012. Corpus Linguistics: Method, Theory and Practice. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Montes-Alcalá, Cecilia. 2015. Code-switching in US Latino Literature: The role of biculturalism. Language and Literature 24: 264–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morin, Regina. 2006. Evidence in the Spanish language press of linguistic borrowings of computer and Internet-related terms. Spanish in Context 3: 161–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mrak, Ariana. 2011. Lexical transfer from English to Spanish: How do bilingual and monolingual communities compare? Southwest Journal of Linguistics 30: 95–115. [Google Scholar]

- Ortego-Antón, María Teresa, and Janine Pimentel. 2019. Interlingual transfer of social media terminology: A case study based on a corpus of English, Spanish and Brazilian newspaper articles. Babel 65: 114–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Otheguy, Ricardo, Ofelia García, and Mariela Fernández. 1989. Transferring, switching, and modeling in West New York Spanish: An intergenerational study. International Journal of the Sociology of Language 79: 41–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Poplack, Shana, and Nathalie Dion. 2012. Myths and facts about loanword development. Language Variation and Change 24: 279–315. [Google Scholar]

- Rodríguez Medina, María Jesús. 2002. Los anglicismos de frecuencia sintácticos en español: Estudio empírico. RAEL. Revista electróNica de lingüíStica Aplicada 15: 149–170. [Google Scholar]

- Sánchez, María F. 1995. Clasificación y análisis de préstamos del inglés en la prensa de España y México. Ph.D. dissertation, University of Massachusetts, Amherst, MA, USA. [Google Scholar]

- Sanou, Rosa María. 2018. Anglicismos y redes sociales. Cuadernos de la ALFAL 10: 176–91. [Google Scholar]

- Silva-Corvalán, Carmen. 2001. Sociolingüística y Pragmática Del Español. Washington, DC: Georgetown University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Stewart, Ian, Diyi Yang, and Jacob Eisenstein. 2021. Tuiteamos o pongamos un tuit? Investigating the Social Constraints of Loanword Integration in Spanish Social Media. Paper presented at Society for Computation in Linguistics, virtually, February 15–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Valdés- Fallis, Guadalupe Valdés. 1976. Code-switching in bilingual Chicano poetry. Hispania 59: 866–77. [Google Scholar]

- Weinreich, Uriel. 1968. Languages in Contact: Findings and Problems. The Hague: Mouton. [Google Scholar]

- Zimmermann, Klaus. 1995. Aspectos teóricos y metodológicos de la investigación sobre el contacto de lenguas en Hispanoamérica. Lenguas en Contacto en Hispanoamérica 9: 34. [Google Scholar]

| Borrowing | Total Occurrences | Filtered Results | Percentage of Total Tokens |

|---|---|---|---|

| Ghosting | 398 | 314 | 57.5% |

| Gaslighting | 74 | 65 | 11.9% |

| Benching | 45 | 45 | 8.2% |

| Catfishing | 30 | 29 | 5.3% |

| Breadcrumbing | 28 | 28 | 5.1% |

| Orbiting | 44 | 20 | 3.7% |

| Cushioning | 19 | 15 | 2.7% |

| Zombieing/ Zombing | 14 | 14 | 2.6% |

| Kittenfishing | 14 | 14 | 2.6% |

| Curving | 4 | 1 | 0.2% |

| Cuffing | 1 | 1 | 0.2% |

| Fielding | 2563 | 0 | 0 |

| Haunting | 434 | 0 | 0 |

| Caspering | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Cockfishing | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Cookie-jarring | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Pocketing | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Fleabagging | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Paperclipping | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Situationship | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Borrowing | Uppercase | Quotation Marks | Upper Letter & Quotation Mark | Parenthesis | No Change |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ghosting N = 314 | 9 2.9% | 83 26.4% | 18 5.7% | 1 0.3% | 203 64.7% |

| Gaslighting N = 65 | 11 16.9% | 17 26.2% | 3 4.6% | 0 | 34 52.3% |

| Benching N = 45 | 1 2.2% | 13 28.9% | 4 8.9% | 0 | 27 60% |

| Catfishing N = 29 | 1 3.5% | 15 51.7% | 0 | 0 | 13 44.8% |

| Breadcrumbing N = 28 | 1 3.6% | 4 14.3% | 0 | 1 3.6% | 22 78.5% |

| Orbiting N = 20 | 0 | 7 35% | 0 | 0 | 13 65% |

| Cushioning N = 15 | 0 | 9 60% | 0 | 0 | 6 40% |

| Zombing N = 14 | 0 | 4 28.6% | 1 7.1% | 0 | 9 64.3% |

| Kittenfishing N = 14 | 1 7.2% | 3 21.4% | 0 | 0 | 10 71.4% |

| Curving N = 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 100% |

| Cuffing N = 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 100% | 0 | 0 |

| Total Frequency | 25 4.4% | 155 28.4% | 27 5% | 2 0.2% | 338 62% |

| Borrowing | Explanation or Translation | Frequency |

|---|---|---|

| Ghosting N = 314 | 107 | 34.1% |

| Gaslighting N = 65 | 38 | 73.8% |

| Benching N = 45 | 20 | 44.4% |

| Catfishing N = 29 | 25 | 86.2% |

| Breadcrumbing N = 28 | 15 | 53.6% |

| Orbiting N = 20 | 9 | 45% |

| Cushioning N = 15 | 6 | 40% |

| Zombing N = 14 | 3 | 21.4% |

| Kittenfishing N = 14 | 6 | 42.9% |

| Curving N = 1 | 0 | 0 |

| Cuffing N = 1 | 1 | 100% |

| TOTAL 546 | 230 | 42.1% |

| Borrowing | Translation |

|---|---|

| Ghosting | “marcharse” (España, 2013), “desaparición” (Colombia, 2015) “fantasmeo” (México, 2015) “hacerse el fantasma” (Costa Rica, 2015) “desaparecer” (Argentina, 2017) “fantasmear” (Chile, 2017) |

| Gaslighting | “manipular” (Chile, 2018) “volver loco” (Venezuela, 2018) “hacer creer” (Chile, 2019) “hacer luz de gas” (Perú, 2018) |

| Benching | “plan B” (España, 2017) “mantener en el banquillo” (España, 2017) “banqueando” (Chile, 2017) “hacer banco” (Argentina, 2017) “tener como reserva” (Perú, 2018) “dar falsas ilusiones” (Paraguay, 2018) “peor es nada” (Bolivia, 2018) |

| Catfishing | “robo de identidad” (Estados Unidos, 2017) “fingir” (México, 2019) “usurpar” (Hondura, 2019) “perfil falso” (Estados Unidos, 2019) |

| Breadcrumbing | “migajas de pan” (España, 2017) “submarinear” (Chile, 2017) “mantener el interés” (Uruguay, 2019) |

| Orbiting | “mantener en la órbita” (Argentina, 2019) “monitorear” (Argentina, 2019) |

| Cushioning | “acolchar” (Chile, 2017) |

| Zombing | - |

| Kittenfishing | “engañar” (Chile, 2017) |

| Curving | - |

| Cuffing | “temporada de las esposas” (Nicaragua, 2017). |

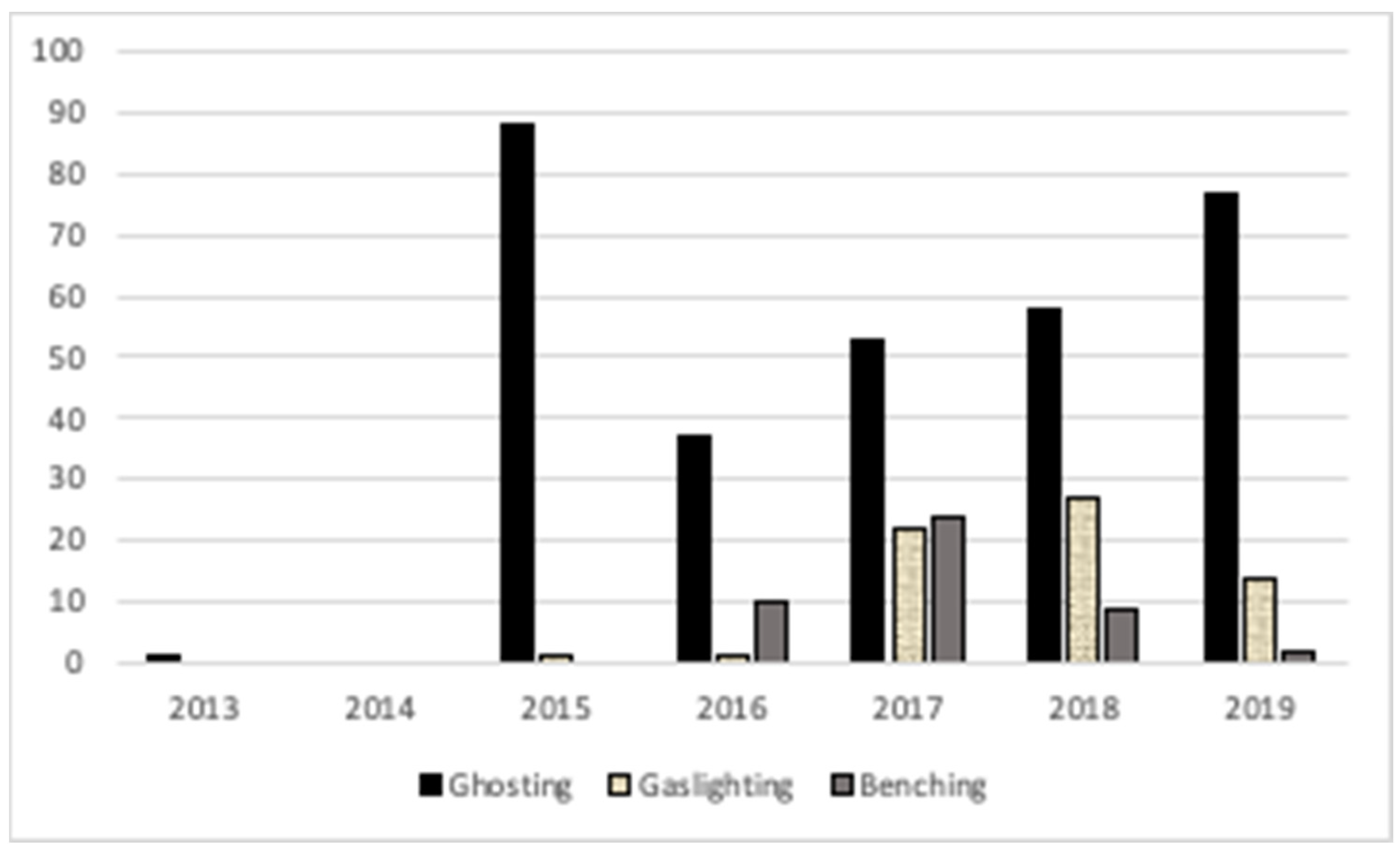

| Borrowing | Date |

|---|---|

| Ghosting | 2013 |

| Gaslighting | 2015 |

| Benching | 2016 |

| Catfishing | 2016 |

| Breadcrumbing | 2017 |

| Orbiting | 2018 |

| Cushioning | 2017 |

| Zombing | 2016 |

| Kittenfishing | 2017 |

| Curving | 2019 |

| Cuffing | 2017 |

| Country | Total (546) | Frequency |

|---|---|---|

| Argentina | 128 | 23.4% |

| Spain | 67 | 12.27% |

| US | 65 | 11.9% |

| Mexico | 53 | 9.7% |

| Chile | 50 | 9.1% |

| Peru | 41 | 7.5% |

| Uruguay | 29 | 5.3% |

| Borrowing | Country | Percent of Total Tokens |

|---|---|---|

| Ghosting N = 314 | Argentina | 25.5% |

| Gaslighting N = 65 | USA | 24.6% |

| Benching N = 45 | Argentina | 24.4% |

| Catfishing N = 29 | Chile | 17.2% |

| Breadcrumbing N = 28 | Uruguay | 32.1% |

| Orbiting N = 20 | Argentina | 40% |

| Cushioning N = 15 | Spain | 60% |

| Zombing N = 14 | Argentina | 64.3% |

| Kittenfishing N = 14 | Chile | 78.6% |

| Curving N = 1 | Cuba | 100% |

| Cuffing N = 1 | Nicaragua | 100% |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Rull García, I.; Bove, K.P. Ghosting, Breadcrumbing, Catfishing: A Corpus Analysis of English Borrowings in the Spanish Speaking World. Languages 2022, 7, 119. https://doi.org/10.3390/languages7020119

Rull García I, Bove KP. Ghosting, Breadcrumbing, Catfishing: A Corpus Analysis of English Borrowings in the Spanish Speaking World. Languages. 2022; 7(2):119. https://doi.org/10.3390/languages7020119

Chicago/Turabian StyleRull García, Irene, and Kathryn P. Bove. 2022. "Ghosting, Breadcrumbing, Catfishing: A Corpus Analysis of English Borrowings in the Spanish Speaking World" Languages 7, no. 2: 119. https://doi.org/10.3390/languages7020119

APA StyleRull García, I., & Bove, K. P. (2022). Ghosting, Breadcrumbing, Catfishing: A Corpus Analysis of English Borrowings in the Spanish Speaking World. Languages, 7(2), 119. https://doi.org/10.3390/languages7020119