The Emergence of a Mixed Type Dialect: The Example of the Dialect of the Bani ˁAbbād Tribe (Jordan)

Abstract

:1. Introduction

The Traditional Classification of Jordanian Dialects in the Light of Recent Developments

- The urban Palestinian dialects (biˀūl), which typologically belong to the Levantine urban dialects;

- The rural dialects, which are in turn grouped into:

- the Galilean dialects (biqūl);

- the central Palestinian dialects (biḳūl), more conservative than the Galilean dialects;

- the south Palestinian dialects (bigūl), closely related to the previous ones, they have some features that show a greater Bedouin (especially Negev) influence;

- the north and central Transjordanian dialects (bigūl), closely related to the Horan dialects;

- the south Transjordanian dialects (bigūl), that are influenced by the Hijazi Bedouin dialects of Arabia Petraea and represent a mixed dialect type;

- The Bedouin dialects, which are in turn divided into:

- The dialects of Negev (bigūl), which show some features typical of the sedentary dialects (namely the b-imperfect). The dialects of this group typologically belong to the Sinai type, and they exhibit some similarities with the Bedouin dialects of Arabia Petraea;

- The dialects of Arabia Petraea (yigūl), they display some affinities with the Hijazi dialects;

- The dialects of the Syro-Mesopotamian sheep-rearing tribes (yigūl), spoken in Transjordan, “(they) belong to the same type as the rest of the dialects of the sheep-rearing tribes in the Syrian and Mesopotamian peripheries of the Syrian Desert” (Palva 1984, p. 372).

- The dialects of the North Arabian Bedouin type, yigūl, spoken in Transjordan by the Sirḥān, the Bani Ṣaxar and the Bani Xālid.

- (I)

- Sedentary bigūlu: Muʔābi and Balgāwi-Ḥōrāni;

- (II)

- Southern Bedouin ygūlu (Ḥwēṭāt, Bdūl, Zawāyda, etc…);

- (III)

- Southern Bedouin bigūlu (mostly Nagab and Sinai);

- (IV)

- Central Bedouin ygūlu (ʕAǧārma, ʕAdwān, ʕAbābīd, etc…);

- (V)

- Northern Bedouin ygūlūn: ʕNizi, Šammari, Bc (Misāʕīd), Šāwi, Ca (Bū ʕĪd et ʕĪdīn in Lebanon, so far unattested in Jordan)

2. Materials and Methods

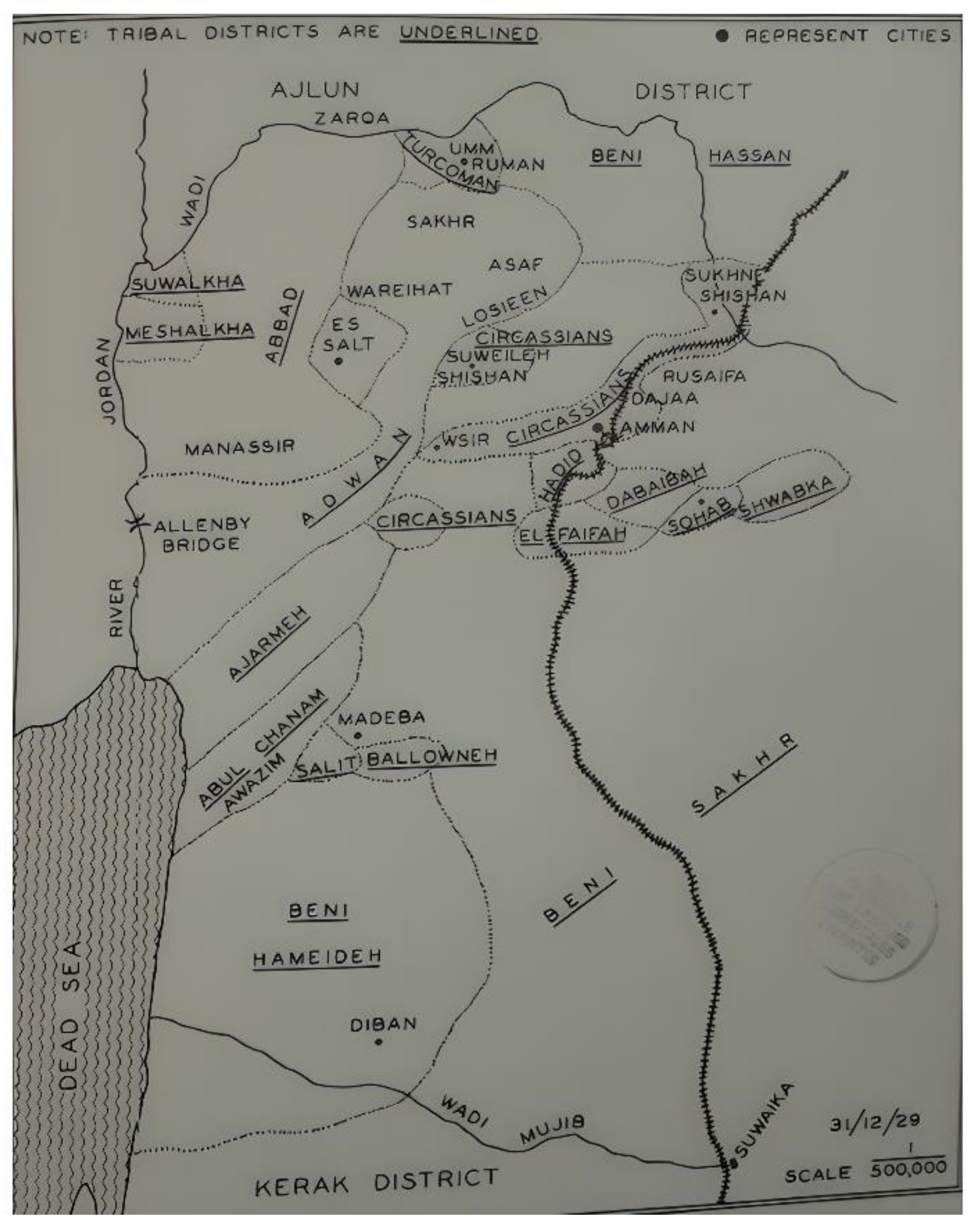

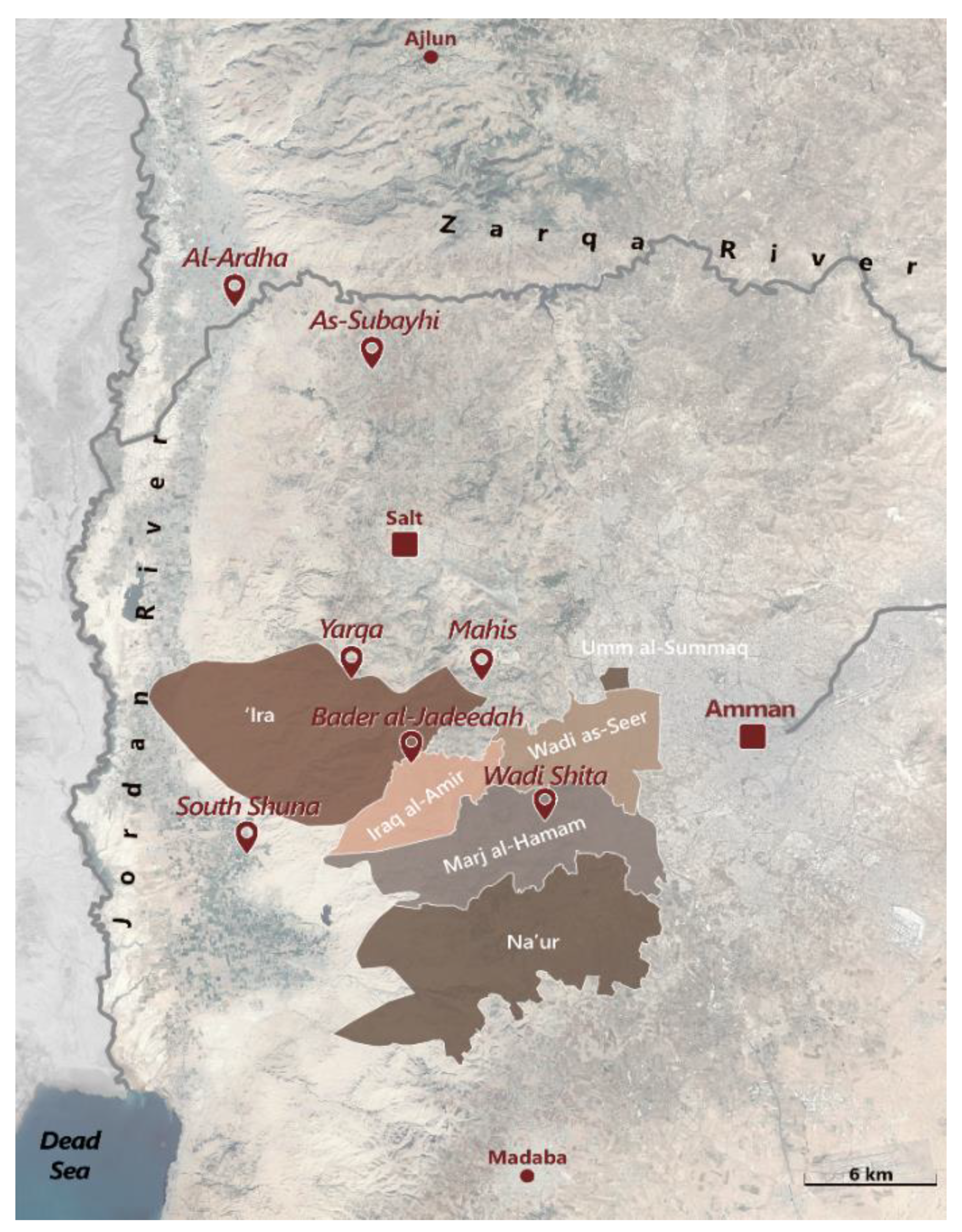

2.1. The Tribe

2.2. Functional Framework

3. Linguistic Analysis

3.1. Contact Induced Changes in the Contemporary Dialect of the Bani ˁAbbād

3.1.1. Phonology and Phonotactics

Reflexes of OA /q/

Reflexes of OA /k/

- The grandmother regularly uses it in the contiguity of a front vowel, and she uses čān even to express the verb ‘to be’.

- The mother uses the affricate /č/ especially to contrast the pronominal suffix of the 2nd m. sing. person and the pronominal suffix of the 2nd f. sing. person; she never uses čān to express the verb ‘to be’, and the only word where she employs / č / is čänna ‘daughter-in-law’, while reciting a poem.

- The daughter never uses the affricate /č/.

Reflexes of the Old Diphthongs /ay/ and /aw/

| (1) | Ygūl-lak | awwal | finǧān | la- ḏ̣- ḏ̣īf |

| to _say.IPFV.3msg-DAT.2msg | first | cup | for-ART-guest | |

| ṯāni | la-s-sīf | aṯ- ṯāliṯ | la-l- ḥīf | |

| second | for-ART-sword | ART-third | for-ART-injustice | |

| One says: the first cup is for the guest, the second to talk about war, and the third to discuss injustice. | ||||

Cases of Trochaism

3.1.2. Morphology

Personal Pronouns

- -

- in the negative copula māni ´I am not´ (6)9;

- -

- in the expression: māni ʕārif ´not knowing´(1), ʔana, māni sāmiʕ ´not listening´(1), ʔani ma ḥibbo al-gatū ´I don´t like the cake´ (1).

Interrogative Pronouns

Verbs C1=ˀ

| (2) | ʕalwēh ani min ʕarab | I wish I was of the people |

| Hadla u la min xaḏa garāyibha | of Hadla and not of those who took her relatives | |

| La (a)ḥuṭṭ ʔana min aḏ- ḏahab ganṭār | so I [could] put a quintal of gold | |

| W aṭlaʕ min al-lōm ʔaxṭobha | and get rid of the blame and betroth her | |

| (3) | rāḥ ʕand aš-šēx ṭalabha, iši ḥabbha al-muhimm, banāt garāybo w an-nās illi yagrabūlo mā ḥabbu inno yḥibbha laʔanno ṯāri u mrattab ḥabbu inno yōxiḏ minhum u mā xaḏa minhum. | |

| (4) | axaḏu | humma | al-ǧanūb | kāmel |

| to_take.PFV.3mpl | they.m | ART-south | complete | |

| They took over the whole South. | ||||

| (5) | gabel | al-ʕeǧib | bass | yākol | xobez |

| before | ART-children | but | to_eat. IPFV.3msg | bread | |

| min | ʕa- ṣ- ṣayǧān | maʕa | šāy | ||

| from | on-ART-ṣayǧān | with | tea | ||

| Before the children only ate bread made on the ṣāǧ10 with tea. | |||||

| (6) | al-aġnām | yōklu | min-ha | akṯar | xuḏār | mā | fi |

| ART-sheep | to_eat.IPFV.3mpl | of.3fsg | most | vegetables | NEG | there were | |

| They ate mostly sheep (meat), there were no vegetables. | |||||||

Prepositions

| (7) | hāḏ̣ | faddān | ad-darrāsāt | ʕugub | |

| DEM.msg | pair of oxen | ART-harvester | after | ||

| gabel | yudrusu | ʕa-l-ḥamīr | w | al-bugar | |

| Before | to_thresh.IPFV.3mpl | on-ART-donkeys | and | ART-cows | |

| After one threshed with a pair of oxen, [but] before with some donkeys and cows. | |||||

| (8) | Mīn | ḥakam | ʕugubu-hum | al-inglīz |

| who | to_rule.PFV.3msg | after-3mpl | ART-English | |

| Who ruled after them? The English. | ||||

Conditional Conjunctions

| (9) | ʔiḏa | ʔiǧa | ḏ̣ēf | min | barra |

| if | to_come.PFV.3msg | guest | from | outside | |

| ma | ysawwū-lo | akel | ˁādi | yiḏbaḥū-lo | |

| NEG | to_make.IPFV.3mpl-for-3msg | food | simple | to_slaughter.IPFV. 3mpl-for-3msg | |

| xarūf | yiḏbaḥū-lo | naʕǧe | ʕanz | ||

| ram | to_slaughter.IPFV. 3mpl-for-3msg | sheep | goat | ||

| If a guest comes from far away, one does not prepare for him a normal meal, one slaughters for him a ram or a sheep or a goat. | |||||

| (10) | ʔiḏa | enta | ma | hazzēt |

| if | you | NEG | to_shake.PFV.2msg | |

| al-finǧān | yḏ̣all | yṣubbū-l-ek | ||

| ART-cup | to_keep.IPFV.3msg | to_pour.IPFV.3msg-for-2msg | ||

| If you don’t shake the cup, one keeps pouring you (coffee). | ||||

3.1.3. Syntax

Genitive Exponent

| (11) | kānu | yḥarrkū | haḏ̣ōla |

| to_be.PVF.3mpl | to_stir.IPVF.3mpl-3msg | DET.pl | |

| bi-l-maġrāfe | tabaʕat11 | al-xašab | |

| in-ART-ladle | tabaʕ.fsg | ART-wood | |

| They stirred those with the wooden ladle | |||

| (12) | al-gider | ṭanǧara | kbīra | yḥuṭṭu |

| ART-cauldron | pan | big | to_put.IPVF.3mpl | |

| bī-ha | al-ǧarīša | tabaʕat | al-gameḥ | |

| in-3fsg | ART-grain | tabaʕ.fsg | ART-wheat | |

| The cauldron is a big pan where they put the grain of wheat | ||||

| (13) | Dār gīti dār tabaʕti, hal-kalime kānat mawǧūda, gīti aw šīti, yaʕni mulki w ili, ā zayy hēk ā, al-banāt giyyāti aw ḥalālāti yaʕni ili ḥatta ʕan al-ġanam ygūlu-lo giyyāti, kānat mawǧūde hassāʕʕ bistaʕmalūha at-tuǧǧār ʕenna, maṯalan ygūl lak ʔana gayyāti 3 alāf ʔana gayyāti 10 alāf, yaʕni flūsi. |

Dār gīt13i or dār tabaʕti ‘my house’, gīti or šīti, this word existed, it means of mine, mine, like this yes, al-banāt giyyāti ‘my daughters’ or ḥalālāti ´my cattle´ for example, one also used to say al-ġanam giyyāti ‘my sheep´, this existed but now businessmen use it, to say my 3 or 10 thousand, to indicate my money.

Negation

| (14) | ʕašāʔir | al-ǧanūb | lāʔ | mā |

| tribes | ART-South | NEG | NEG | |

| bēn-na | u | bēn-hum | mašākil | |

| between-1pl | and | between-3mpl | problems | |

| There were no problems between us and the tribes of the South. | ||||

| (15) | gabel | yinsawi | šaḥge | mū | dabka |

| before | to_make.PASS.3msg | šaḥge15 | NEG | dabka | |

| Before one [used to] dance the šaḥge and not the dabka. | |||||

| (16) | hāy | əl-muṣṭalaḥāt | hāy | alān | ixtafat |

| DEM.3fsg | ART-terms | DEM.3fsg | now | to_change.PFV.3fsg | |

| min | ǧīlna | miš | mawǧūde | yaˁni | |

| from | generation-1pl | NEG | present.3fsg | it is to say | |

| These terms here have now disappeared from our generations, they are no more present. | |||||

| (17) | ḏahab | ṭalaʕ | zayy | ḥǧār | miš | ḏahab |

| gold | to_appear.PVF.3msg | like | stones | NEG | gold | |

| The gold appeared in the form of stones not gold. | ||||||

| (18) | muš | al-kull | kwayyis | muš | al-kull | mirtāḥ |

| NEG | ART-all | good | NEG | ART-all | wealthy | |

| We do not all have a good financial situation; we are not all wealthy | ||||||

| (19) | mā | fi-š | maʕo | maṣāri |

| NEG | there is-NEG | with-3msg | money | |

| He has no money. | ||||

| (20) | mā | fi-š | maḥākim | mā | fi-š | muḥāmiyyīn |

| NEG | there were-NEG | tribunals | NEG | there were-NEG | lawyers | |

| [Before] there were no tribunals nor lawyers. | ||||||

b-Imperfect

| (21) | humma | bistagbilu | aḏ̣-ḏ̣yūf |

| they | to_welcome.IPFV.HAB.3mpl | ART-guests | |

| They welcome the guests. | |||

| (22) | bitḥuṭṭi | al-laḥme | w | al-snōbar |

| to_put.IPFV.HAB.2fsg | ART-meat | and | ART-pine nuts | |

| You add the meat and the pine nuts. | ||||

| (23) | ayyām-ha | ən-nās | mā | maʕā-ha |

| days-DEM | ART-people | NEG | with-3fsg | |

| drāsa | mā | btaʕrif | iši | |

| education | NEG | to_know.IPFV.HAB.3fsg | thing | |

| In those days people were not educated, they didn’t know anything. | ||||

| (24) | Fa yitǧawwaz az-zalama…ˀiḏa kān fi ʿindhum dār biskin bi-nafs ad-dār ygullak waladna mā biṭlaʕ barra yaˁni muḥarram inno yiṭlaʕ yiskin xārǧ al-manṭega illi humma sāknīn fīha… bi- ẓ- ẓabṭ... hāy al- ʕāda. |

| (25) | zulum | yṭlubu | al-ʕarūs | byaʕṭī-hum |

| men | to_ask.IPFV.HAB.3mpl | ART-bride | to_give.IPFV.HAB.3msg-3mpl | |

| Some men ask for the hand of the bride, he grants it to them. | ||||

| (26) | bitḏakkar | waḥda | barḏ̣o | qiṣṣa | min | al-qiṣaṣ |

| to_remember.IPFV.PROG.1sg | one.f | also | story | between | ART-stories | |

| I also remember another story [now]. | ||||||

Future

| (27) | wədd-ak | trūḥ | ʕ-al-ḥakīm |

| want-2msg | to_go.IPFV.2msg | to-ART-doctor | |

| You will go to the doctor. | |||

| (28) | bidd-i | ōkil | tīn |

| want.1sg | to_eat.IPFV.1sg | figs | |

| I will eat figs. | |||

4. Discussion

4.1. Bedouin or Sedentary?

“When groups in contact need to communicate, they have a number of possible choices. One is to use a lingua franca they both share […]. A second option is for one or more parties to learn the other group’s language(s). In cases involving no substantial imbalances of power between the groups, stable multilingualism may result. However, where bilingualism is asymmetrical and the more powerful group imposes its language on a subordinate group, contact often leads to language shift or loss”.

- -

- Fi al-muṣṭalaḥāt hāḏ̣i yaʕni wlādna alli ʕomrhum ṯalāṯīn sana u xamsa u ʕašrīn sana mā kānu yaʕrifūha liʔannha iltaġat min zamān ā, iltaġat min zamān.

- -

- Ṭabb al-luġa al-ʕabbādiyya ʕam bitrūḥ?

- -

- Muʕḏ̣amha hī trūḥ hassāʕ ṣārat madaniyya maʕḏ̣omha hassāʕ madaniyya… kull iši ʕindana yaʕni al-luġa al-ʕabbādiyya mā ḏ̣all maʕāha galīl ǧiddan.

- -

- There are these terms [that] our children whose age is 30 or 25 years old do not know because they changed a while ago, yes, changed [a lot of] time ago.

- -

- Well, so where is the ʕAbbādi language going?

- -

- Most of it is disappearing, now it has become madani, most of it has become madani…all of our things, I mean there is very little left of the ʕAbbādi language.

4.2. Emergence of a Mixed Dialect Type by Sedentarization

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

| 1 | Herin (2019, p. 96) already introduced those within the yigūl label (Southern Nomadic yigūlu, Central Nomadic yigūlu, and Northern Nomadic yigūlūn), differenciating between the Jordanian Bedouin varieties that display or not the final -n in the imperfective 3. m. pl. form of the verb to “to say”. |

| 2 | This corpus was originally transcribed in 2017 for my master dissertation Le dialecte des Bani ˁAbbād Analyse des traits phonologiques, morphologiques et syntaxiques discriminants. |

| 3 | Elicitations were used in some specific cases in order to obtain complete paradigms and inquire about specific vocabulary. |

| 4 | In order to respect all ethical demands usual in linguistic studies, all the present people were informed about my aims, and they accepted to be recorded for research purposes. |

| 5 | Only the interview recorded in ˁArāg al-ˁAmīr was carried out by Prof. B. Herin, my master supervisor, who at that time was also in Jordan. |

| 6 | The thesis was written under the supervision of Prof. B. Herin and defended at INALCO, Paris, in 2018. |

| 7 | This feature will be treated in detail in the section dedicated to the bound pronouns. |

| 8 | For this example, I refer to the records of three women, members of the same family: the illiterate grandmother of 90 years old, who has always lived in Yarga and who hasn’t had long contacts with Palestinians; the mother of 55 years old, who had access to academic education and who also lives in Yarga; the daughter of 23 years old, a student at The University of Jordan. |

| 9 | This number indicates the number of occurrences of the described phenomenon in the corpus. |

| 10 | Heating plate on which the Bedouins bake the bread. |

| 11 | It is worth mentioning that this genitive exponent is gender variable. |

| 12 | This form is attested in the speech of the old and conservative speakers in Fḥēṣ as reported by Herin (2010, p. 373). |

| 13 | Seemingly used with or without article on the head-noun. |

| 14 | From the manuscript of his lecture for the workshop Machtverhältnisse und Sprachkontakte in der Syrischen Steppe: Die Beziehungen zwischen Beduinen und Sesshaften im Spiegel der Dialekte, FU Berlin, 27 June 2018. |

| 15 | Traditional dance performed by men during weddings. |

| 16 | In the corpus there are 15 occurrences of mā fiš, against 27 instances of mā fi. |

| 17 | This pseudo-verb can be used also to express deontic shade (Younes and Herin 2016, p. 11). |

| 18 | There are 32 instances of bidd- and 31 of widd-. |

| 19 | In this respect, one of the women interviewed told me that during her university years she was talking with other girls of her class, not Bedouin, and she used the expression bi-s-sāʕ ‘quickly’. They did not understand her and pointed out how weird was her way of speaking. Then she added “if you speak like we do to other people, they don’t understand, they laugh at you”. |

| 20 | With this term it is implied that major sedentary linguistic features penetrated in a historical Bedouin dialect. |

References

- Al Tawil, Miriam. 2019. La langue arabe parlée dans le Ḥōrān. Master’s thesis, Università degli Studi di Catania, Catania, Italy. [Google Scholar]

- Al Tawil, Miriam. 2021. Morpho-Syntactic Features of Bedouin Varieties in Northern Jordan. Naples: Maydan, Working Paper in Publication. [Google Scholar]

- Behnstedt, Peter. 1997. Sprachatlas von Syrien. I: Kartenband, Semitica Viva 17. Wiesbaden: Harrassowitz. [Google Scholar]

- Bergsträsser, Gotthelf. 1915. Sprachatlas von Syrien und Palästina. Zeitschrift des Deutschen Palästina-Vereins 38: 169–222. [Google Scholar]

- Bettini, Lidia. 2006. Contes Féminins de La Haute Jézireh Syrienne. Matériaux Ethno-Linguistiques d’un Parler Nomade Oriental. Florence: Dipartimento di Linguistica. [Google Scholar]

- Blanc, Haim. 1970. The Arabic Dialect of the Negev Bedouins. Jerusalem: Academic Press. [Google Scholar]

- Brustad, Kristen. 2000. The Syntax of Spoken Arabic: A Comparative Study of Moroccan, Egyptian, Syrian, and Kuwaiti Dialects. Washington, DC: Georgetown University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Cadora, Frederic J. 1992. Bedouin, Village and Urban Arabic: An Ecolinguistic Study. Leiden: Brill. [Google Scholar]

- Cantineau, Jean. 1936. Études Sur Quelques Parlers de Nomades Arabes d’Orient 1. Annales de l’Institut d’Études Orientales 2: 1–118. [Google Scholar]

- Cantineau, Jean. 1937. Études Sur Quelques Parlers de Nomades Arabes d’Orient 2. Annales de l’Institut d’Études Orientales 3: 119–237. [Google Scholar]

- Cantineau, Jean. 1946. Les Parlers Arabes du Ḥōrân. Paris: Klincksieck. [Google Scholar]

- Cleveland, Ray L. 1963. A Classification of the Arabic Dialects of Jordan. Bulletin of the American Schools of Oriental Research 171: 56–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Creissels, Denis. 1995. Éléments de Syntaxe Générale. Paris: Presses Universitaires de France—PUF. [Google Scholar]

- Creissels, Denis. 2006a. Syntaxe Générale, une Introduction Typologique: Tome 1, Catégories et Constructions. Paris: Hermes Science Publications. [Google Scholar]

- Creissels, Denis. 2006b. Syntaxe Générale, une Introduction Typologique: Tome 2, La Phrase. Paris: HERMES SCIENCE. [Google Scholar]

- De Jong, Rudolf. 2000. A Grammar of the Bedouin Dialects of the Northern Sinai Littoral: Bridging the Linguistic Gap between the Eastern and Western Arab World. Leiden: Brill. [Google Scholar]

- François, Alexandre, and Maïa Ponsonnet. 2013. Descriptive Linguistics. In Theory in Social and Cultural Anthropology: An Encyclopedia. Edited by Jon R. McGee and Richard L. Warms. London: SAGE, vol. 1, pp. 184–87. Available online: https://www.academia.edu/16430720/_Fran%C3%A7ois_and_Ponsonnet_Descriptive_linguistics_encyclopedia_entry_ (accessed on 12 June 2021).

- Giles, Howard, Donald M. Taylor, and Richard Bourhis. 1973. Towards a Theory of Interpersonal Accommodation through Language: Some Canadian Data1. Language in Society 2: 177–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gumperz, John. 1969. Communication in Multilingual Societies. In Cognitive Anthropology. Edited by S. Tyler. New York: Holt, Rinehart and Winston, pp. 435–49. [Google Scholar]

- Haspelmath, Martin, and Andrea D. Sims. 2010. Understanding Morphology, 2nd ed. Understanding Language Series; London: Hodder Education. [Google Scholar]

- Henkin, Roni. 2010. Negev Arabic: Dialectal, Sociolinguistic, and Stylistic Variation. Wiesbaden: Harrassowitz. [Google Scholar]

- Herin, Bruno. 2010. Le Parler Arabe de Salt, Jordanie: Phonologie, Morphologie et Eléments de Syntaxe. Ph.D. thesis, Université libre de Bruxelles, Bruxelles, Belgium. Available online: http://hdl.handle.net/2013/ (accessed on 16 October 2020).

- Herin, Bruno. 2019. Traditional Dialects. In The Routledge Handbook of Arabic Sociolinguistics, 1st ed. Edited by Enam Al-Wer and Uri Horesh. Series: Routledge Language Handbooks: Routledge; New York: Routledge, pp. 93–105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Herin, Bruno, Igor Younes, Enam Al-Wer, and Youssef Al-Sirour. 2022. The Classification of Bedouin Arabic: Insights from Northern Jordan. Languages 7: 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holes, Clive. 1995. Community, Dialect and Urbanization in the Arabic-Speaking Middle East. Bulletin of the School of Oriental and African Studies 58: 270–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Isaksson, Bo. 1999. The Non-Standard First Person Singular Pronoun in the Modern Arabic Dialects. Zeitschrift für arabische Linguistik 37: 54–83. [Google Scholar]

- Lentin, Jérôme. 1994. Classification et Typologie Des Dialectes Du Bilād Al-Šām: Quelques Suggestions Pour Un Réexamen. Matériaux Arabes et Sudarabiques (MAS-Gellas) 6: 11–36. [Google Scholar]

- Giles, Howard, and Tania Ogay. 2007. Communication Accommodation Theory. In Explaining Communication: Contemporary Theories and Exemplars. Edited by Bryan B. Whaley and Wendy Samter. Available online: https://www.academia.edu/35366642/Howard_Giles_et_Tania_Ogay_2007_Communication_Accommodation_Theory (accessed on 10 December 2021).

- Oppenheim, Max Freiherr von. 1943. Die Beduinen 2 Die Beduinenstämme in Palästina, Transjordanien, Sinai, Hedjāz. Leipzig: Harrassowitz. [Google Scholar]

- Palva, Heikki. 1969. Balgāwi Arabic. 2. Texts in the dialect of the Ygūl- group. Studia Orientalia (Helsinki) 40: 1–15. [Google Scholar]

- Palva, Heikki. 1976. Studies in the Arabic Dialect of the Semi-Nomadic Əl-ʕAǧārma Tribe (al-Balqāʔ District, Jordan). Goeteburg: University of Goeteburg. [Google Scholar]

- Palva, Heikki. 1982. Patterns of Koineization in Modern Colloquial Arabic. Acta Orientalia (Copenhagen) 43: 13–32. [Google Scholar]

- Palva, Heikki. 1984. A General Classification for the Arabic Dialects Spoken in Palestine and Transjordan. Studia Orientalia 55: 357–76. [Google Scholar]

- Palva, Heikki. 1992. Typological Problems in the Classification of Jordanian Dialects: Bedouin or Sedentary? In The Middle East Viewed from the North. Papers from the First Nordic Conference of Middle Eastern Studies, Uppsala, 26–27 January 1989. Edited by Bo Utas and Knut S. Vikør. Bergen: Alma Mater Forlag, pp. 53–62. [Google Scholar]

- Palva, Heikki. 1994. Bedouin and Sedentary Elements in the Dialect of es-Salṭ. Diachronic notes on the sociolinguistic development. In Actes des premières journées internationales de dialectologie arabe de Paris. Edited by Dominique Caubet and Martine Vanhove. Paris: Inalco, pp. 459–69. [Google Scholar]

- Peake, Frederick. 1958. A History of Jordan and Its Tribes. Miami: University of Miami Press. [Google Scholar]

- Procházka, Stephan. 2018. Manuscript of his lecture for the workshop. In Machtverhältnisse und Sprachkontakte in der Syrischen Steppe: Die Beziehungen zwischen Beduinen und Sesshaften im Spiegel der Dialekte. Berlin: FU Berlin, June 27. [Google Scholar]

- Romaine, Suzanne. 2010. Contact and Language Death. In The Handbook of Language Contact. Hoboken and Chichester: John Wiley & Sons, Ltd., pp. 320–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rosenhouse, Judith. 1984. The Bedouin Arabic Dialects. General Problems and a Close Analysis of North Israel Bedouin Dialects. Wiesbaden: Harrassowitz. [Google Scholar]

- Rosenhouse, Judith. 2006. Bedouin Arabic. In Encyclopedia of Arabic Language and Linguistics. Edited by Kees Versteegh. Leiden: Brill, pp. 259–69. [Google Scholar]

- Sakarna, Ahmad Khalaf. 1999. Phonological Aspects of 9abady Arabic, a Bedouin Jordanian Dialect. Ph.D. thesis, University of Wisconsin, Madison, WI, USA. [Google Scholar]

- Sawaie, Mohammed. 2011. Jordan. In Encyclopaedia of Arabic Language and Linguistics. Edited by Lutz Edzard and K. De Jong. Leiden: Brill. [Google Scholar]

- Shryock, Andrew. 1997. Nationalism and the Genealogical Imagination: Oral History and Textual Authority in Tribal Jordan, 1st ed. Berkeley: University of California Press. [Google Scholar]

- Torzullo, Antonella. 2018. Le Dialecte des Bani ˁAbbād: Analyse des Traits Phonologiques, Morphologiques et Syntaxiques Discriminants. Master’s thesis, INALCO, Paris, France. [Google Scholar]

- Trudgill, Peter. 1999. New-Dialect Formation and Dedialectalization: Embryonic and Vestigial Variants. Journal of English Linguistics 27: 319–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trudgill, Peter. 2010. Contact and Sociolinguistic Typology. In The Handbook of Language Contact. Hoboken and Chichester: John Wiley & Sons, Ltd., pp. 299–319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Versteegh, Kees. 1984. Pidginization and Creolization: The Case of Arabic. Current Issues in Linguistic Theory, 33. Amsterdam: Benjamins. [Google Scholar]

- Watson, Janet C. E. 2011. Arabic Dialects (General Article). In The Semitic Languages: An International Handbook. Edited by Stefan Weninger. Berlin and Boston: De Gruyter Mouton, pp. 851–96. [Google Scholar]

- Younes, Igor, and Bruno Herin. 2013. Un Parler Bédouin Du Liban Note Sur Le Dialecte Des ʿAtīǧ (Wādī Xālid). Zeitschrift Für Arabische Linguistik 58: 32–65. [Google Scholar]

- Younes, Igor, and Bruno Herin. 2016. Šāwi Arabic. In Encyclopedia of Arabic Language and Linguistics, online ed. Leiden: Brill. [Google Scholar]

- Younes, Igor. 2014. Notes Prélminaires Sur Le Parler Bédouin Des Abu ʿĪd (Vallée de La Békaa). Romano-Arabica 14: 355–87. [Google Scholar]

- Younes, Igor. 2017. Dialect Contact in the Beqaa Valley. Romano-Arabica 17: 131–40. [Google Scholar]

| yčammilen ‘they (f.) finish’ 3 | yġammirin ‘they (f.) collect’ 1 |

| ytālifu ‘they (m.) gathered’ 1 | rākib-u ‘he mounted it’ 2 |

| ahl-a-ha ‘her family’ 6 waǧh-a-ha ‘her face’ 1 geddām-a-na ‘in front of us’ 1 |

| ˁašān-a-ha ‘because of her’1 ˁomr-a-ha ‘her age’ 1 |

| 1. s. | ʔana̴ ʔani | 1. p. | ʔiḥna̴ ʔaḥna ̴ ʔəḥna |

| 2. m. s. | ʔinta̴ ʔinte | 2. m. p. | ʔintu |

| 2. f. s. | ʔinti | 2. f. p. | ʔintin |

| 3. m. s. | huwwa̴ hū | 3. m. p. | humma̴ humm |

| 3. f. s. | hiyya̴ hī | 3. f. p. | hinna̴ hinn ̴ hunna |

| Who…? | mīn; min |

| What…? | šū ̴ šu; wēš; əš ̴ʔēš |

| Which…? | ʔayy(a) |

| How…? | čīf; šlōn; kēf ̴ kīf |

| Where…? | wēn |

| When…? | mata; mita; ʔēmta; waymat |

| Why…? | lēš; lwēš |

| How much…? | gaddēš ̴ geddēš; čam; kam |

| 1. sg. xaḏēt ̴ ʔaxaḏt | kalēt ̴ ʔakalt | 1. pl. xaḏēna ̴ ʔaxaḏna | kalēna ̴ ʔakalna |

| 2. m. sg. xaḏēt ̴ ʔaxaḏet | kalēt ̴ ʔakalet | 2. m. pl. xaḏētu ̴ ʔaxaḏtu | kalētu ̴ ʔakaltu |

| 2. f. sg. xaḏēti ̴ ʔaxaḏti | kalēti ̴ ʔakalti | 2. f. pl. xaḏēten ̴ ʔaxaḏten | kalēten ̴ ʔakalten |

| 3. m. sg. xaḏa ̴ ʔaxaḏ | kala ̴ ʔakal | 3. m. pl. xaḏu ̴ ʔaxaḏu | kalu ̴ ʔakalu |

| 3. f. sg. xaḏat ̴ ʔaxaḏat | kalat ̴ ʔakalat | 3. f. pl. xaḏēn ̴ ʔaxaḏen | kalēn ̴ ʔakalen |

| 1. sg. āxuḏ ̴ ōxuḏ | ākil ̴ ōkil | 1. pl. nāxuḏ ̴ nōxuḏ | nākul ̴ nōkil |

| 2. m. sg. tāxuḏ ̴ tōxuḏ | tākul ̴ tōkil | 2. m. pl. tāxḏu ̴ tōxḏu | tāklu ̴ tōklu |

| 2. f. sg. tāxdi ̴ tōxḏi | tākli ̴ tōkli | 2. f. pl. tāxḏin/en ̴ tōxḏin | tāklin/en ̴ tōklin |

| 3. m. sg. yāxuḏ ̴ yōxuḏ | yākul ̴ yōkil | 3. m. pl. yāxḏu ̴ yōxḏu | yāklu ̴ yōklu |

| 3. f. sg. tāxuḏ ̴ tōxuḏ | tākul ̴ tōkil | 3. f. pl. yāxḏin/en ̴ yōxḏin | yāklin/en ̴ yōklin |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Torzullo, A. The Emergence of a Mixed Type Dialect: The Example of the Dialect of the Bani ˁAbbād Tribe (Jordan). Languages 2022, 7, 9. https://doi.org/10.3390/languages7010009

Torzullo A. The Emergence of a Mixed Type Dialect: The Example of the Dialect of the Bani ˁAbbād Tribe (Jordan). Languages. 2022; 7(1):9. https://doi.org/10.3390/languages7010009

Chicago/Turabian StyleTorzullo, Antonella. 2022. "The Emergence of a Mixed Type Dialect: The Example of the Dialect of the Bani ˁAbbād Tribe (Jordan)" Languages 7, no. 1: 9. https://doi.org/10.3390/languages7010009

APA StyleTorzullo, A. (2022). The Emergence of a Mixed Type Dialect: The Example of the Dialect of the Bani ˁAbbād Tribe (Jordan). Languages, 7(1), 9. https://doi.org/10.3390/languages7010009