Effects of Recasts, Metalinguistic Feedback, and Students’ Proficiency on the Acquisition of Greek Perfective Past Tense

Abstract

:1. Introduction

1.1. Recasts, Prompts and L2 Development

1.2. Students’ Proficiency

1.3. Corrective Feedback and Linguistic Target

1.4. The Current Study

- Does interactional CF in the form of recasts and metalinguistic feedback affect L2 learners’ explicit knowledge development of the Greek perfective past tense morphology?

- What is the relationship between the effectiveness of CF type and learners’ proficiency?

- Do recast and metalinguistic feedback have differential effects on L2 learners’ explicit knowledge?

- Does the efficacy of recasts and metalinguistic feedback on the use of the perfective past tense morphology relate to learners’ proficiency?

2. Materials and Methods

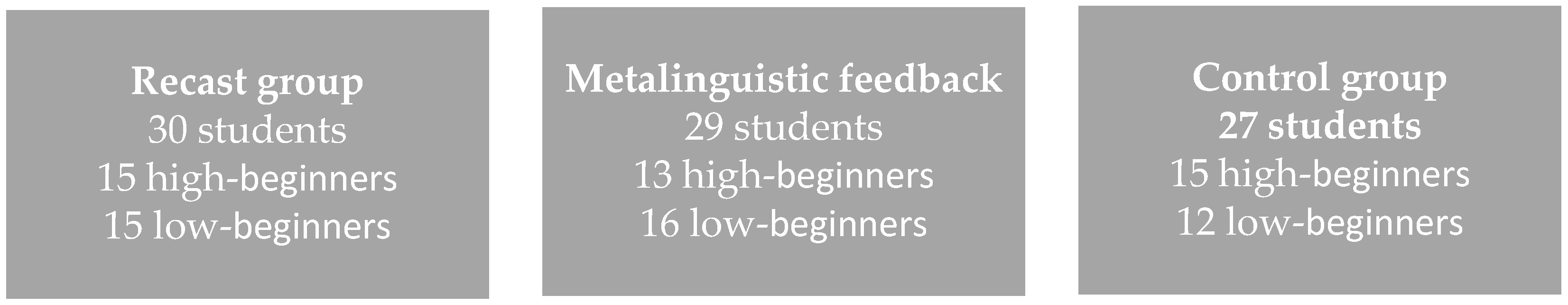

2.1. Participants and Instructional Context

2.2. Feedback Conditions

- (1)L: Όταν πλήρησε*... [error: stem]“When he paid*..”.R: Πλήρωσε. [CF: recast]“Paid”.L: Όταν πλήρωσε το ταξί, το πορτοφόλι του έπεσε στο πάτωμα. [uptake: repair-incorporation]“When he paid for the taxi, his wallet fell on the floor”.

- (2)L: Μετά πάρε* τη σκάλα. [error: stem]‘’Then, he took* the ladder”R: Μετά πήρε τη σκάλα. [CF: recast]‘’Then, he took the ladderL: Και έβαλε κοντά από το τοίχος*. [topic continuation]‘And he put it near the wall’’

- (3)L: O Κώστας βγήκε στο κλαμπ και χόρεψα. [error: person]“Kostas went out to the club and I danced*”.R: Εγώ χόρεψα. Aυτός….; [Metalinguistic feedback: comment and question]“I danced. He…?”L: Χόρεψε. [uptake: self-repair]“He danced”

2.3. Target Structure

- (4) graf-o, e-grap-s-a ‘I wirte’, ‘I wrote’

- (5) agap(a)-o, agapi-s-a ‘I love’, ‘I loved’

- (6) vlep-o, id-a ‘I see’, ‘I saw’

2.4. Treatment Instruments

2.5. Testing Instruments Placement Test

2.6. Grammaticality Judgment Test

2.7. Procedures

2.8. Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Corrective Feedback Types and Explicit Knowledge Development

3.2. The Relationship between the Effectiveness of CF Type and Learners’ Proficiency

3.3. The Effects of Recasts and Metalinguistic Feedback on L2 Learners’ Explicit Knowledge

3.4. The Effect of Students’ Proficiency on the Efficacy of Recasts and Metalinguistic Feedback

4. Discussion

- (7) L: O Γιώργος συναντήσει* τη Σίντι. [error: ending and stress]George meet* CindyT: Συνάντησε; [CF: recast]Met?L: Συνάντησε τον Δημήτρη και Σίντι. [uptake: incorporated]Met Dimitris and Cindy.

5. Conclusions and Implications

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

| 1 | Greek is a highly inflected language. Verbs are formed by the combination of the stem and an inflectional ending. Verbs in Modern Greek are morphologically marked for aspect, tense, voice, as well as person and number (Holoton et al. 1997). |

| 2 | For the Greek past tense morphology see (Holoton et al. 1997; Ralli 2005). For the instruction of the simple past tense rules in Greek as L2 for beginners see the beginners coursebooks used by the teachers of the Modern Greek language teaching center (Simopoulos et al. 2010; Gareli et al. 2012). |

| 3 | Fraenkel et al. (2011) suggest that the minimum sample of an experimental study should range from 15 to 30 participants in each experimental group. |

| 4 | At this point we would like to mention that during the process of designing the study it was impossible to find tasks in the instructional material available for teaching Greek as an L2, when the research was conducted (e.g., Simopoulos et al. 2010; Gareli et al. 2012). |

References

- Agathopoulou, Eleni, and Despina Papadopoulou. 2009. Morphological Dissociations in the L2 acquisition of an inflectionally rich language. In EUROSLA Yearbook. Edited by Leah Roberts, Georges Daniel Véronique, Anna Nilsson and Marion Tellier. Amsterdam: John Benjamins, vol. 9, pp. 107–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ammar, Ahlem, and Nina Spada. 2006. One size fits all? Recasts, prompts, and L2 learning. Studies in Second Language Acquisition 28: 543–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anderson, John, R. Byrne, D. Michael, Douglass Scott, Lebiere Christian, and Yulin Qin. 2004. An integrated theory of the mind. Psychological Review 111: 1036–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Antoniou, Maria, Maria Galazoula, Stavroula Dimitrakou, and Anastasia Maggana. 2010. Μαθαίνουμε ελληνικά ακόμα καλύτερα. Athens: Kedros. [Google Scholar]

- Asghar, Amanda. 2010. Reciprocal peer coaching and its use as a formative assessment strategy for first-year students. Assessment & Evaluation in Higher Education 35: 403–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Basturkmen, Helen, and Menxia Fu. 2021. Corrective feedback and the development of second language grammar. In The Cambridge Handbook of Corrective Feedback in Second Language Learning and Teaching. Edited by Hossein Nassaji and Eva Kartchava. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, pp. 367–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bigelow, Martha, Robert Delmas, Kit Hansen, and Elaine Tarone. 2006. Literacy and the Processing of Oral Recasts in SLA. TESOL Quarterly 40: 665–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Black, Paul, and Wiliam Dylan. 1998. Assessment and classroom learning. Assessment in Education: Principles, Policy & Practice 5: 7–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Braidi, Susan. 2002. Reexamining the role of recasts in native-speaker/nonnative-speaker interactions. Language Learning 52: 1–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brookhart, Susan M., Connie M. Moss, and Beverly A. Long. 2010. Teacher inquiry into formative assessment practices in remedial reading classrooms. Assessment in Education: Principles, Policy & Practice 17: 41–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carroll, Susanne, and Merrill Swain. 1993. Explicit and implicit negative feedback: An empirical study of the learning of linguistic generalizations. Studies in Second Language Acquisition 15: 357–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chaudron, Craig. 1977. A descriptive model of discourse in the corrective treatment of learners’ errors. Language Learning 27: 29–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chaudron, Craig. 1988. Second Language Classrooms: Research on Teaching and Learning. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Clahsen, Harald, Maria Martzoukou, and Stavroula Stavrakaki. 2010. The perfective past pense in Greek as a second language. Second Language Research 26: 501–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cohen, Louis, Manion Lawrence, and Morrison Keith. 2011. Research Methods in Education, 7th ed. Oxon: Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Cook, Vivian. 1985. Chomsky’s universal grammar and second language learning. Applied Linguistics 6: 2–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Council of Europe. 2001. Common European Framework of Reference for Languages: Learning, Teaching, Assessment. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- De Boot, Kees. 1996. The psycholinguistics of the output hypothesis. Language Leaning 46: 529–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dekeyser, Robert. 1998. Beyond focus on form: Cognitive perspectives on learning and practicing second language grammar. In Focus on Form in Classoom Second Language Acquisition. Edited by Catherine Doughty and Jessica Williams. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, pp. 42–63. [Google Scholar]

- Dekeyser, Robert. 2015. Skill acquisition theory. In Theories in Second Language Acquisition. Edited by Bill VanPatten and Jessica Williams. New York and London: Routledge, pp. 96–112. [Google Scholar]

- Dilans, Gatis. 2010. Corrective feedback and L2 vocabulary development: Prompts and recasts in the adult ESL Classroom. Canadian Modern Language Review 66: 787–816. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Doughty, Catherine. 2001. Cognitive underpinnings of focus on form. In Cognition and Second Language Instruction. Edited by Peter Robinson. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, pp. 206–57. [Google Scholar]

- Doughty, Catherine, and Elizabeth Varela. 1998. Communicative focus on form. In Focus on Form in Classroom Second Language Acquisition. Edited by Catherine Doughty and Jessica Williams. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, pp. 114–38. [Google Scholar]

- Egi, Takako. 2007. Interpreting recasts as linguistic evidence: The roles of linguistic target, length, and degree of change. Studies in Second Language Acquisition 29: 511–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ellis, Rod. 2001. Introduction: Investigating form-focused production. Language Learning 51: 1–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ellis, Rod. 2007. The differential effects of corrective feedback on two grammatical structures. In Conversational Interaction in Second Language Acquisition: A Collection of Empirical Studies. Edited by Alison Mackey. Oxford: Oxford University Press, pp. 339–60. [Google Scholar]

- Ellis, Rod. 2009. Corrective feedback and teacher development. L2 Journal 1: 3–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Ellis, Rod. 2017. Oral corrective feedback in L2 classrooms: What we know so far. In Corrective Feedback in Second Language Teaching and Learning. Edited by Hossein Nassaji and Eva Kartchava. New York: Routledge, pp. 3–18. [Google Scholar]

- Ellis, Rod. 2021. Explicit and implicit oral corrective feedback. In The Cambridge Handbook of Corrective Feedback in Second Language Learning and Teaching. Edited by Hossein Nassaji and Eva Kartchava. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, pp. 341–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ellis, Rod, and Younghee Sheen. 2006. Re-examining the role of recasts in L2 acquisition. Studies in Second Language Acquisition 28: 575–600. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ellis, Rod, Shawn Loewen, and Rosemary Erlam. 2006. Implicit and explicit corrective feedback and the acquisition of L2 grammar. Studies in Second Language Acquisition 28: 339–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Farrokhi, F. 2007. Teachers’ stated beliefs about corrective feedback in relation to their practices in EFL classes. Research on Foreign Languages Journal of Faculty of Letters and Humanities 49: 91–131. [Google Scholar]

- Fraenkel, Jack, Norman Wallen, and Helen Hyun. 2011. How to Design and Evaluate Research in Education, 8th ed. New York: McGraw-Hill. [Google Scholar]

- Gareli, Efi, Efi Kapoula, Stela Nestoratou, Evaggelia Pritsi, Nikos Roumbis, and Georgia Sikara. 2012. Ταξίδι στην Ελλάδα: Νέα ελληνικά για ξένους, επίπεδα A1 & A2. Athens: Grigoris publications. [Google Scholar]

- Gass, Susan. 1997. Input, Interaction, and the Second Language Learner. Mahwah: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates. [Google Scholar]

- Gass, Susan, and Evangeline Marlos Varonis. 1994. Input, interaction, and second language production. Studies in Second Language Acquisition 16: 283–302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Goo, Jaemyung. 2012. Corrective feedback and working memory capacity in interaction-driven L2 learning. Studies in Second Language Acquisition 34: 445–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goo, Jaemyung, and Alison Mackey. 2013. The case against the case against recasts. Studies in Second Language Acquisition 35: 127–165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Guchte, Marrit, Martine Braaksma, Gert Rijlaarsdam, and Peter Bimmel. 2015. The effects of recasts and prompts. The Modern Language Journal 99: 246–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, Zhaohong. 2002. A study of the impact of recasts on tense consistency in L2 output. TESOL Quarterly 36: 543–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, Zhaohong, and Jihyun H. Kim. 2008. Corrective recasts: What teachers might want to know. Journal of Language Learning 36: 35–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harmer, Jeremy. 2007. The practice of English Language Teaching. Harlow: Longman. [Google Scholar]

- Havranek, Gertraud. 2002. When Is corrective feedback most likely to succeed? International Journal of Educational Research 37: 255–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holoton, David, Peter Mackridge, and Irene Philippaki-Warburton. 1997. Greek: A Comprehensive Grammar of the Modern Language. London: Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Hume, Anne, and Richard K. Coll. 2009. Assessment of learning, for learning, and as learning: New Zealand case studies. Assessment in Education: Principles, Policy & Practice 16: 269–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ioannou, Sophia. 2020. Corrective Feedback in Greek as a Second Language Beginners’ Classrooms. Ph.D. dissertation, University of Athens, Athens, Greece. [Google Scholar]

- Ioannou, Sophia, and Dina Tsagari. 2022. Interactional corrective feedback in beginner level classrooms of Greek as a second language: Teachers’ practices. Research Papers in Language Teaching and Learning 12: 7–25. [Google Scholar]

- Ishida, Midori. 2004. Effects of recasts on the acquisition of the aspectual form -te I-(Ru) by learners of Japanese as a foreign language. Language Learning 54: 311–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kartchava, Eva. 2019. Noticing Oral Corrective Feedback in Second Language Classroom. Background end Evidence. London: Lexington books. [Google Scholar]

- Kartchava, Eva, and Ahlem Ammar. 2014. The noticeability and effectiveness of corrective feedback in relation to target Type. Language Teaching Research 18: 428–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, He-Rim, and Gienn Mathes. 2001. Explicit vs. implicit corrective feedback. The Korea TESOL Journal 4: 1–15. [Google Scholar]

- Lantolf, James, Steven Thorne, and M. Poehner. 2015. Sociocultural theory and second language development. In Theories in Second Language Acquisition: An Introduction, 2nd ed. Edited by Bill Van Patten and Jessica Williams. New York and London: Routledge, pp. 207–19. [Google Scholar]

- Lardiere, Donna. 1998. Dissociating syntax from morphology in a divergent L2 End-State grammar. Second Language Research 14: 359–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leeman, Jennifer. 2003. Recasts and second language development: Beyond negative evidence. Studies in Second Language Acquisition 25: 37–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Huifang. 2018. Recasts and output-only prompts, individual learner factors and short-term EFL Learning. System 76: 103–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Shaofeng. 2009. The differential effects of implicit and explicit feedback on second language (L2) learners at different proficiency levels. Applied Language Learning 19: 53–79. [Google Scholar]

- Li, Shaofeng. 2010. Feedback in Perspective: The Interface between Feedback Type, Proficiency, the Choice of the Target Structure, and Learners’ Individual Differences in Working Memory and Language Analytic Ability. Ph.D. dissertation, Michigan State University, East Lansing, MI, USA. [Google Scholar]

- Li, Shaofeng. 2013. The Interface between Feedback Type, L2 Proficiency, and the Nature of the Linguistic Target. Language Teaching Research 18: 373–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Shaofeng. 2018. Data collection in the research on the effectiveness of corrective feedback: A synthetic and critical review. In Critical Reflections on Data in Second Language Acquisition. Edited by Aarnes Gudmestad and Amanda Edmonds. Amsterdam: John Benjamins, pp. 33–61. [Google Scholar]

- Li, Shaofeng, Zhu Yan, and Rod Ellis. 2016. The effects of the timing of corrective feedback on the acquisition of a new linguistic structure. The Modern Language Lournal 100: 276–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Loewen, Shawn. 2004. Uptake in incidental focus on form in meaning-focused ESL lessons. Language Learning 54: 153–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Loewen, Shawn. 2009. Grammaticality judgment tests and the measurement of implicit and explicit L2 knowledge. In Implicit and Explicit Knowledge in Second Language Learning, Testing and Teaching. Edited by Rod Ellis, Shawn Loewen, Catherine Erlam, Jenefer Philp and Hayo Reinders. Bristol: Blue Ridge Summit: Multilingual Matters, pp. 94–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Loewen, Shawn, and Toshiyo Nabei. 2007. Measuring the effects of oral corrective feedback on L2 knowledge. In Conversational Interaction in Second Language Acquisition: A Collection of Empirical Studies. Edited by Alison Mackey. Oxford: Oxford University Press, pp. 361–78. [Google Scholar]

- Loewen, Shawn, and Jenefer Philp. 2006. Recasts in the adult English L2 classroom: Characteristics, explictness and effectiveness. Modern Language Journal 90: 536–556. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Long, Michael. 1996. The role of the linguistic environment in second language acquisition. In Handbook of Language Acquisition. Edited by William C. Ritchie and Tej K. Bhatia. San Diego: Academic Press, pp. 413–68. [Google Scholar]

- Long, Michael H. 2007. Problems in SLA. New Work: Lawrence Erlbaum. [Google Scholar]

- Lyster, Roy. 1998. Negotiation of form, recasts, and explicit correction in relation to error types and learner repair in immersion classrooms. Language Learning 48: 183–218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Lyster, Roy. 2004. Differential effects of prompts and recasts in form-focused instruction. Studies in Second Language Acquisition 26: 399–432. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Lyster, Roy, and Hirohide Mori. 2006. Interactional feedback and instructional counterbalance. Studies in Second Language Acquisition 2: 269–300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Lyster, Roy, and Jesus Izquierdo. 2009. Prompts versus recasts in dyadic Interaction. Language Learning 59: 453–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lyster, Roy, and Kazuya Saito. 2010. Oral feedback in classroom SLA: A meta-analysis. Studies in Second Language Acquisition 32: 265–302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Lyster, Roy, and Leila Ranta. 1997. Corrective feedback and learner uptake negotiation of form in communicative classrooms. Studies in Second Language Acquisition 19: 37–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lyster, Roy, and Leila Ranta. 2013. Counterpoint piece: The case for variety in corrective feedback research. Studies in Second Language Acquisition 35: 167–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Lyster, Roy, Kazuya Saito, and Masatoshi Sato. 2013. Oral corrective feedback in second language classrooms. Language Teaching 46: 1–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Mackey, Alison. 2020. Interaction, Feedback and Task Research in Second Language Learning: Methods and Design. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mackey, Alison, and Jaemyung Goo. 2007. Interaction research in SLA: A meta-analysis and research synthesis. In Conversational Interaction in Second Language Acquisition. Edited by Alison Mackey. New York: Oxford, pp. 407–52. [Google Scholar]

- Mackey, Alison, and Jaemyung Goo. 2012. Interaction approach in second language acquisition. In The Encyclopedia of Applied Linguistics. Edited by Carol Chapelle. Chichester: Wiley-Blackwell, pp. 2748–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mackey, Alison, and Jeneffer Philp. 1998. Conversational interaction and second language development: Recasts, responses and red herringf? The Modern Language Journal 82: 338–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mackey, Alison, and Sussan Gass. 2015. Interaction approaches. In Theories in Second Language Acquisition: An Introduction, 2nd ed. Edited by Bill VanPatten and Jessica Williams. London: Routledge, pp. 180–206. [Google Scholar]

- Mackey, Alison, Rebekha Abbhul, and Susan Gass. 2012. Interactionist Approach. In The Routledge Handbook of Second Language Acquisition. Edited by Susan Gass and Alison Mackey. London: Routledg, pp. 7–23. [Google Scholar]

- Mackey, Alison, Susan Gass, and Kim Mcdonough. 2000. How do learners pervcive interactional feedback? Studies in Second Language Acquisition 22: 471–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- McDonough, Kim. 2007. Interactional feedback and the emergence of simple past activity verbs in L2 English. In Conversational Interaction in Second Language Acquisition: A Collection of Empirical Studies. Edited by Alison Mackey. Oxford: Oxford University Press, pp. 323–38. [Google Scholar]

- McDonough, Kim, and Alison Mackey. 2006. Responses to recasts. Repetitions, primed production, and linguistic development. Language Learning 56: 693–720. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nassaji, Hossein. 2007. Elicitation and reformulation and their relationship with learner repair in dyadic interaction. Language Learning 57: 511–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nassaji, Hossein. 2009. Effects of recasts and elicitations in dyadic Interaction and the role of feedback explicitness. Language Learning 59: 411–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nassaji, Hossein. 2015. The Interactional Feedback Dimension in Instructed Second Language Learning. London: Bloomsbury. [Google Scholar]

- Nassaji, Hossein. 2017. The effectiveness of extensive versus intensive recasts for learning L2 Grammar. Modern Language Journal 101: 353–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Nassaji, Hossein. 2019. The effects of recasts versus prompts on immediate uptake and learning of a complex target structure. In Language Learning & Language Teaching. Edited by Robert M. DeKeyser and Goretti Prieto Botana. Amsterdam: John Benjamins Publishing Company, pp. 107–26. [Google Scholar]

- Nassaji, Hossein. 2020. Assessing the effectiveness of interactional feedback for L2 acquisition: Issues and Challenges. Language Teaching 53: 3–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nassaji, Hossein, and Eva Kartchava, eds. 2021. The Cambridge Handbook of Corrective Feedback in Second Language Learning and Teaching. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nicholas, Howard, Patsy Lightbown, and Nina Spada. 2001. Recasts as feedback to language learners. Language Learning 51: 719–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Philp, Jenefer. 2003. Constraints on ‘noticing the gap’: Nonnative speakers’ noticing of recasts in NS-NNS Interaction. Studies in Second Language Acquisition 25: 99–126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pica, T. 1994. Research on negotiation: What does It reveal about second-language learning conditions, processes, and outcomes? Language Learning 44: 493–527. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pienemann, Manfried, and Anke Lenzing. 2015. Processability theory. In Theories in Second Language Acquisition. Edited by Bill VanPatten and Jessica Williams. New York and London: Routledge, pp. 159–79. [Google Scholar]

- Ralli, Angela. 2003. Review article: Morphology in Greek linguistics: The State of the Art. Journal of Greek Linguistics 4: 77–129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Ralli, Angela. 2005. Morphology. Athens: Pataki. [Google Scholar]

- Ranta, Leila, and Roy Lyster. 2017. Form-Focused Instruction. In The Routledge Handbook of Language Awareness. Edited by Peter Garrett and Joseph Cots. London: Routledge. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rea-Dickins, Pauline. 2004. Understanding teachers as agents of assessment. Language Testing 2: 249–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Rea-Dickins, Pauline. 2008. Classroom-based language assessment. Encyclopedia of Language and Education 7: 257–72. [Google Scholar]

- Saito, Kazuya, and Roy Lyster. 2012. Effects of form-focused instruction and corrective feedback on L2 pronunciation development of /ɹ/ by Japanese learners of English. Language Learning 62: 595–633. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schmidt, Richard. 2001. Attention. In Cognition and Second Language Instruction. Edited by Peter Robinson. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, pp. 3–32. [Google Scholar]

- Schütze, Carson. 2016. The Empirical Base of Linguistics Grammaticality Judgments and Linguistic Methodology. Berlin: Language Science Press. [Google Scholar]

- Schwartz, Bonnie. 1993. On explicit and negative data effect in and affecting competence and linguistic behavior. Studies in Second Language Acquisition 15: 147–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scrivener, Jim. 2011. Learning Teaching. The Essential Guide to English Language Teaching. Oxford: Macmillan. [Google Scholar]

- Sheen, Younghee. 2006. Exploring the relationship between characteristics of recasts and learner uptake. Language Teaching Research 10: 361–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sheen, Younghee. 2007. The effects of corrective feedback, language aptitude, and learner attitudes on the acquisition of English articles. In Conversational Interaction in Second Language Acquisition: A Collection of Empirical Studies. Edited by Alison Mackey. Oxford: Oxford University Press, pp. 301–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simopoulos, Georgios, Eirini Pathiaki, Rita Kanellopoulou, and Aglaia Pavlopoulou. 2010. Ελληνικά A’. Μέθοδος εκμάθησης της ελληνικής ως ξένης γλώσσας. Athens: Patakis. [Google Scholar]

- Skehan, Peter. 1998. A Cognitive Approach to Language Learning. Oxford: Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Swain, Merrill. 1993. The output hypothesis: Just speaking and writing aren’t enough. The Canadian Modern Language Review 50: 158–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Swain, Merrill. 2005. The output hypothesis: Theory and Research. In Handbook of Research in Second Language Teaching and Learning. Edited by Eric Hinkel. Mahwa: Lawrence Erlbaum, pp. 471–83. [Google Scholar]

- Swain, Merrill, and Sharon Lapkin. 1995. Problems in output and the cognitive process. They generate: A Step Towards Second Language Learning. Applied Linguistics 16: 371–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taras, Maddalena. 2008. Summative and formative assessment: Perceptions and realities. Active Learning in Higher Education 9: 172–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Tarnanen, Mirja, and Ari Huhta. 2011. Foreign language assessment and feedback practices in Finland. In Classroom-Based Language Assessment. Edited by Dina Tsagari and Ildikó Csépes. Language Testing and Evaluation. Frankfurt: Peter Lang, pp. 129–46. [Google Scholar]

- Trofimovich, Pavel, Ahlem Ammar, and Elizabeth Gatbonton. 2007. How effective are recasts? The role of attention, memory, and analytical ability. In Conversational Interaction in Second Language Acquisition: A Series of Empirical Studies. Edited by Alison Mackey. Oxford: Oxford University Press, pp. 171–96. [Google Scholar]

- Tsagari, Dina. 2020. Language Assessment Literacy. Concepts, Challenges, and Prospects. London: Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Turner, Carolyn. 2012. Classroom assessment. In The Routledge Handbook of Language Testing. Edited by Glenn Fulcher and Fred Davidson. London and New York: Routledge, pp. 65–78. [Google Scholar]

- Ur, Penny. 2012. A Course in English Language Teaching. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Vogt, Karin, Dina Tsagari, Ildikó Csépes, Anthony Green, and Nicos Sifakis. 2020. Linking learners’ perspectives on language assessment practices to teachers’ assessment literacy enhancement (TALE): Insights from four Eurepean countries. Language Assessment Quarterly 17: 410–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Xuefeng. 2008. Teachers’ views on conducting formative assessment in Chinese context. Engineering Letters 16: 231–35. [Google Scholar]

- White, Lydia. 2003. Second Language Acquisition and Universal Grammar. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Yang, Yingli, and Roy Lyster. 2010. Effects of form-focused practice and feedback on Chinese EFL learners’ acquisition of regular and irregular past tense forms. Studies in Second Language Acquisition 32: 235–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yilmaz, Yucel. 2012. The relative effects of explicit correction and recasts on two target structures via two communication modes. Language Learning 62: 1134–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Stem | Endings | Place of the Stress | Subject Verb Agreement |

|---|---|---|---|

| *έριψε-έριξε | *έφυγουν-έφυγαν | *εχάσαμε-χάσαμε | *ήπιαμε-ήπιαν |

| * éripse–érikse | *éfigan–éfigan | *exásame–xásame | *ípiame-ípian |

| perfective past, 3rd person singular | perfective past, 3rd person plural | perfective past, 2nd person plural | perfective past, 2nd/3rd person plural |

| to throw | to leave | to lose | to drink |

| *έβγασες-έβγαλες | *φορέσουμε-φορέσαμε | *τρομάξα-τρόμαξα | κατέβηκα-κατέβηκε |

| *évgases-évgales | *forsume-forésame | *tromáksa-trόmaksa | *katévika-katévike |

| perfective past, 2nd person singular | perfective past, 1st person plural | perfective past, 1st person singular | perfective past, 1st/3rd person singular |

| To take out | To wear | To be frighten | To get down |

| *χτύπασα-χτύπησα | *γέλασει-γέλασε | *κλέψε-έκλεψε | *έπεσε-έπεσα |

| *xtípasa–xípisa | *ʝélasi-ʝélase | *klépse-éklepse | Épes–épesa |

| perfective past, 1st person singular | perfective past, 3rd person singular | perfective past, 3rd person singular | perfective past, 3rd/1st person singular |

| To hit | To laugh | To steal | To fall |

| Group | Errors | Recasts | Metalinguistic Feedback |

|---|---|---|---|

| Recast | 229 | 226 | 0 |

| Metalinguistic feedback | 163 | 15 | 157 |

| Control | 152 | 1 | 0 |

| Pretest | Posttest | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Group | n | Mean | S.D. | Means | S.D. |

| Recast | 30 | 16.20 | 0.42 | 18.03 | 0.47 |

| Metalinguistic feedback | 29 | 16.46 | 0.43 | 19.33 | 0.43 |

| Control | 27 | 16.88 | 0.45 | 17.24 | 0.44 |

| Pretest | Posttest | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Proficiency | Group | n | Mean | S.D. | Means | S.D. |

| Low-beginners | Recasts | 15 | 14.13 | 2.48 | 16.13 | 2.45 |

| Metalinguistic feedback | 16 | 14.31 | 2.77 | 17.06 | 2.65 | |

| Control | 12 | 15.71 | 2.79 | 15.75 | 2.73 | |

| High-beginners | Recasts | 15 | 18.27 | 2.40 | 20.47 | 2.45 |

| Metalinguistic feedback | 13 | 18.62 | 1.75 | 21.62 | 1.38 | |

| Control | 15 | 18.60 | 1.29 | 18.73 | 1.71 | |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Ioannou, S.; Tsagari, D. Effects of Recasts, Metalinguistic Feedback, and Students’ Proficiency on the Acquisition of Greek Perfective Past Tense. Languages 2022, 7, 40. https://doi.org/10.3390/languages7010040

Ioannou S, Tsagari D. Effects of Recasts, Metalinguistic Feedback, and Students’ Proficiency on the Acquisition of Greek Perfective Past Tense. Languages. 2022; 7(1):40. https://doi.org/10.3390/languages7010040

Chicago/Turabian StyleIoannou, Sophia, and Dina Tsagari. 2022. "Effects of Recasts, Metalinguistic Feedback, and Students’ Proficiency on the Acquisition of Greek Perfective Past Tense" Languages 7, no. 1: 40. https://doi.org/10.3390/languages7010040

APA StyleIoannou, S., & Tsagari, D. (2022). Effects of Recasts, Metalinguistic Feedback, and Students’ Proficiency on the Acquisition of Greek Perfective Past Tense. Languages, 7(1), 40. https://doi.org/10.3390/languages7010040