Mahdia Dialect: An Urban Vernacular in the Tunisian Sahel Context

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

- ∗

- Menara Fm (http://www.menarafm.net/ accessed on 19 August 2021) is a radio station based in Mahdia since 2019 whose editorial line is based on independence and freedom of expression. It offers many interviews with Tunisian artists and craftsmen and those from other countries in the Arab world, as well as reports, news and live radio broadcasts focused on debates on topical issues chosen by the radio speakers. It also broadcasts some fixed radio programs, such as Nahārek zīn, i.e., “Have a nice day”, in which every morning some presenters give the weather forecasts and the main news of the day.

- ∗

- Radio MFM Tunisie (http://www.mfmtunisie.net/ accessed on 19 August 2021) is a generalist radio station that broadcasts in the regions of Mahdia, Sousse and Sfax and offers programs on sport, news, music and society. It also has daily news programs such as Hadret l-youm, i.e., “Conversation of the day”, and Mid Mag, broadcasted at midday.

- ∗

- Radio Mahdia (https://www.radio-mahdia.info/ accessed on 19 August 2021) broadcasts almost exclusively news programs.

- ∗

- Radio Mahdia 1 (http://www.radiomahdia1.com/ accessed on 19 August 2021) is specialised in tourism and cultural issues. It offers news programs, interviews of the citizens made on the road and interviews of local artists taken in the radio studio, and has a program devoted to children, called Matinal children.

- ∗

- Dār al-šabāb Ražīš (https://tinyurl.com/2fmb88fx accessed on 19 August 2021) is a web radio based in Mahdia, and particularly in Rajiche, a small coastal town in the Mahdia Governorate, created under the patronage of the Ministry of Youth and Sports of the Tunisian Republic. Among the programs broadcast, Mahdia taḥkī, that is “Mahdia speaks”, is interesting since it often brings together people from different generations who discuss a cultural or social topic. This helps analyse the language of speakers of different ages and sex.

- ∗

- Radio Monastir (http://www.radiomonastir.tn/ accessed on 19 August 2021) not only provides news from Wilāyat al-Monastir, but also from all Tunisia, and was very useful for analysing the speech of natives of Monastir and Mahdia. It offers news programs, reportages and topical talk shows.

- ∗

- I also analysed videos taken from the Facebook pages:

- ∗

- Revolution Mahdia, which is a page open to all the inhabitants of Mahdia region whose mission is to foster and promote the freedom of expression and circulation of information in the zone. This is often done through the broadcasting of interviews of the citizen taken on the road.

- ∗

- News Mahdia and Ville de Mahdia, both broadcasting news, social and entertainment programs.

3. Results

3.1. Phonological Remarks

3.1.1. Interdentals

/ṯ/

/ ḏ /

3.1.2. /q/

Free Variants

3.1.3. /ṛ/

3.1.4. De-Emphasisation

3.1.5. Dropping of Final /n/

3.1.6. Vowels

3.1.7. Diphthongs

3.1.8. Imāla

3.1.9. Raising of Final—a

3.2. Nominal Morpho-Syntax

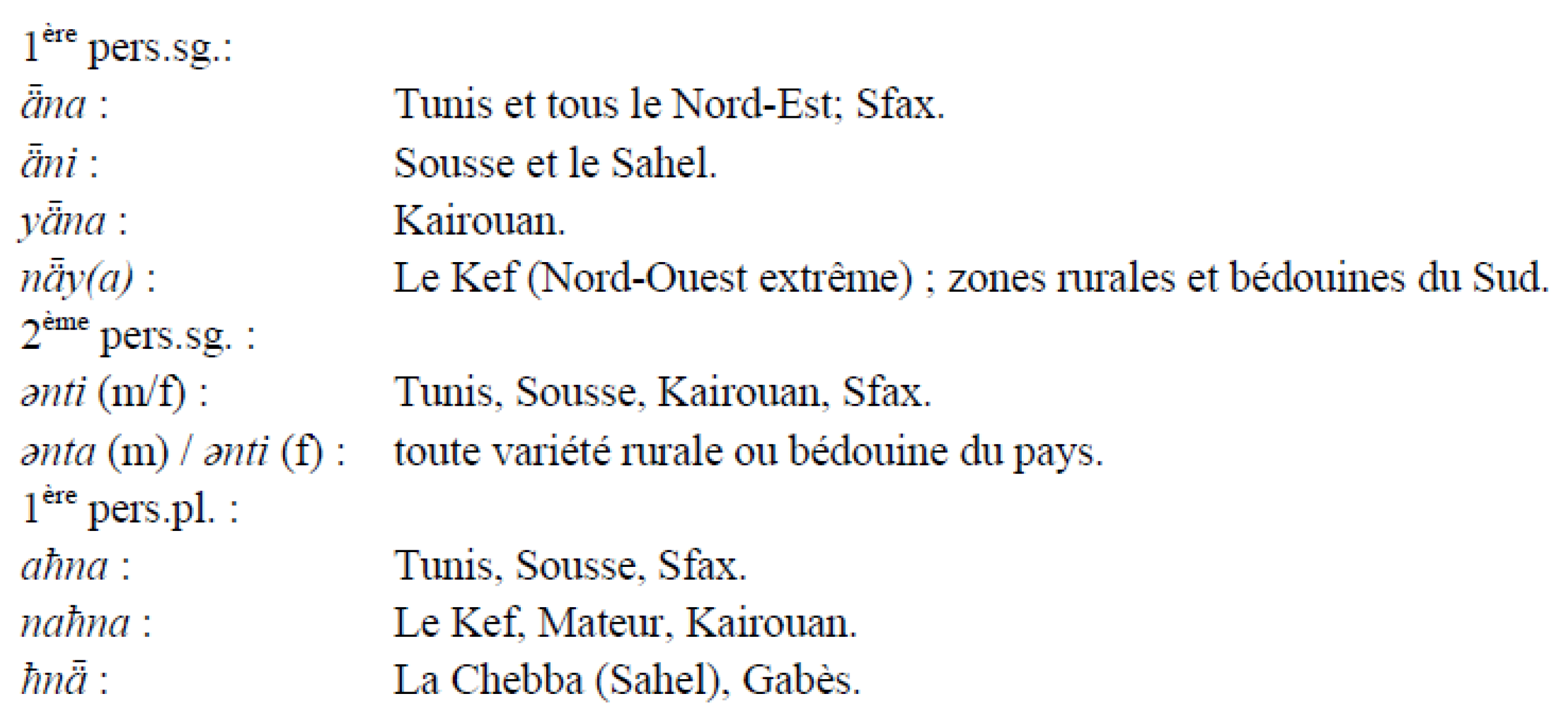

3.2.1. Personal Pronouns

3.2.2. Relative Pronouns

3.2.3. Numerals

3.3. Verbal Morpho-Syntax

3.3.1. An Urban Conjugation

3.3.2. Feminine Third Person Singular of Weak-Final Verbs

3.3.3. Perfect Tense Pattern

3.3.4. Use of the Verb rā

3.3.5. Passive

4. Discussion and Conclusions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

| 1 | “We consider here those of the towns and small cities of the Sahel […] which have not yet been investigated”. English translation is mine. |

| 2 | “The Arabic language of Takroûna is generally consistent with that of the agricultural centres, towns and villages that dot the coastal region of central Tunisia, commonly called Sâḥel […] since the Middle Ages. Separated from each other by differences in detail, these varieties belong, as far as phonetics and grammar are concerned, to the same general type of which takroûni is only a particular variety”. English translation is mine. |

| 3 | I would like to thank Giuliano Mion for reading these pages and for giving me some precious suggestions. I am also grateful to the anonymous reviewers for their suggestions that allowed me to enrich this paper. Any possible imprecision or mistake is, of course, my responsibility. |

| 4 | For an analysis and classification of the urban dialects in the Arab world, see (Vicente 2019, p. 106). |

| 5 | It is what Marçais called “différences de detail” among the dialects of Sahel that we need to describe better, of course, through a team work which will need future studies and the joint commitment of different scholars. |

| 6 | On the use of this term, see (Benkato 2019, p. 9). |

| 7 | http://www.commune-mahdia.gov.tn/en accessed on 1 August 2021. |

| 8 | During the Turkish domination in Tunisia (but also in Algeria), this term, originally meaning ‘son of a slave’ or ‘son of a Janissary’, indicated the population deriving from the marriage of Turks and local women. Many of them were occupied in agriculture or in the local army. Afterwards, they merged with the local population. See Ed. Kul-Oghlu, in (Bearman et al. 1986, vol. 5, p. 366). |

| 9 | Regarding the narration of historical sources on Banū Hilāl as destroyers of the Maghrib, see (Benkato 2019, pp. 5–6, n. 8). |

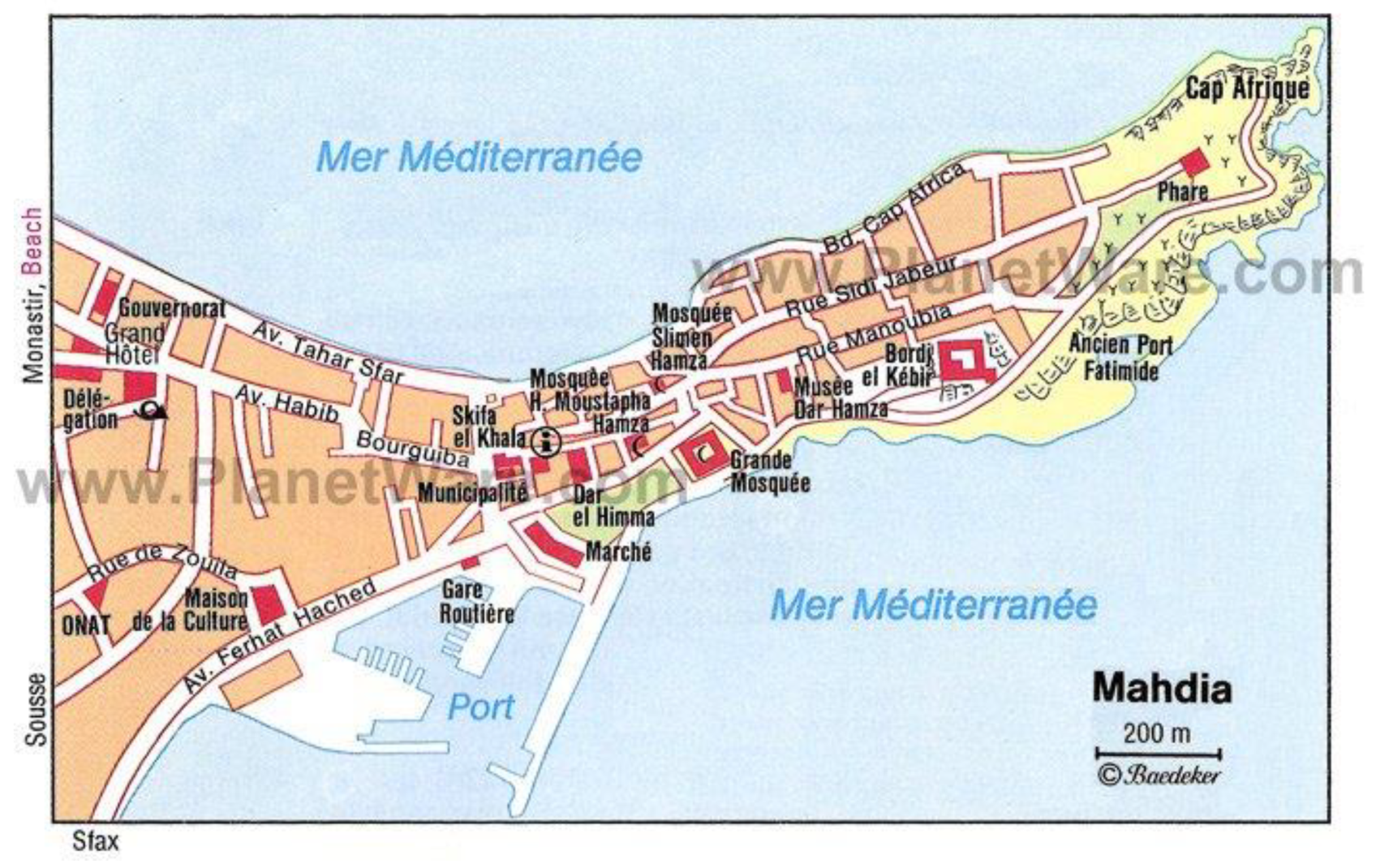

| 10 | https://www.planetware.com/tourist-attractions-/mahdia-tun-md-md.htm accessed on 1 August 2021. |

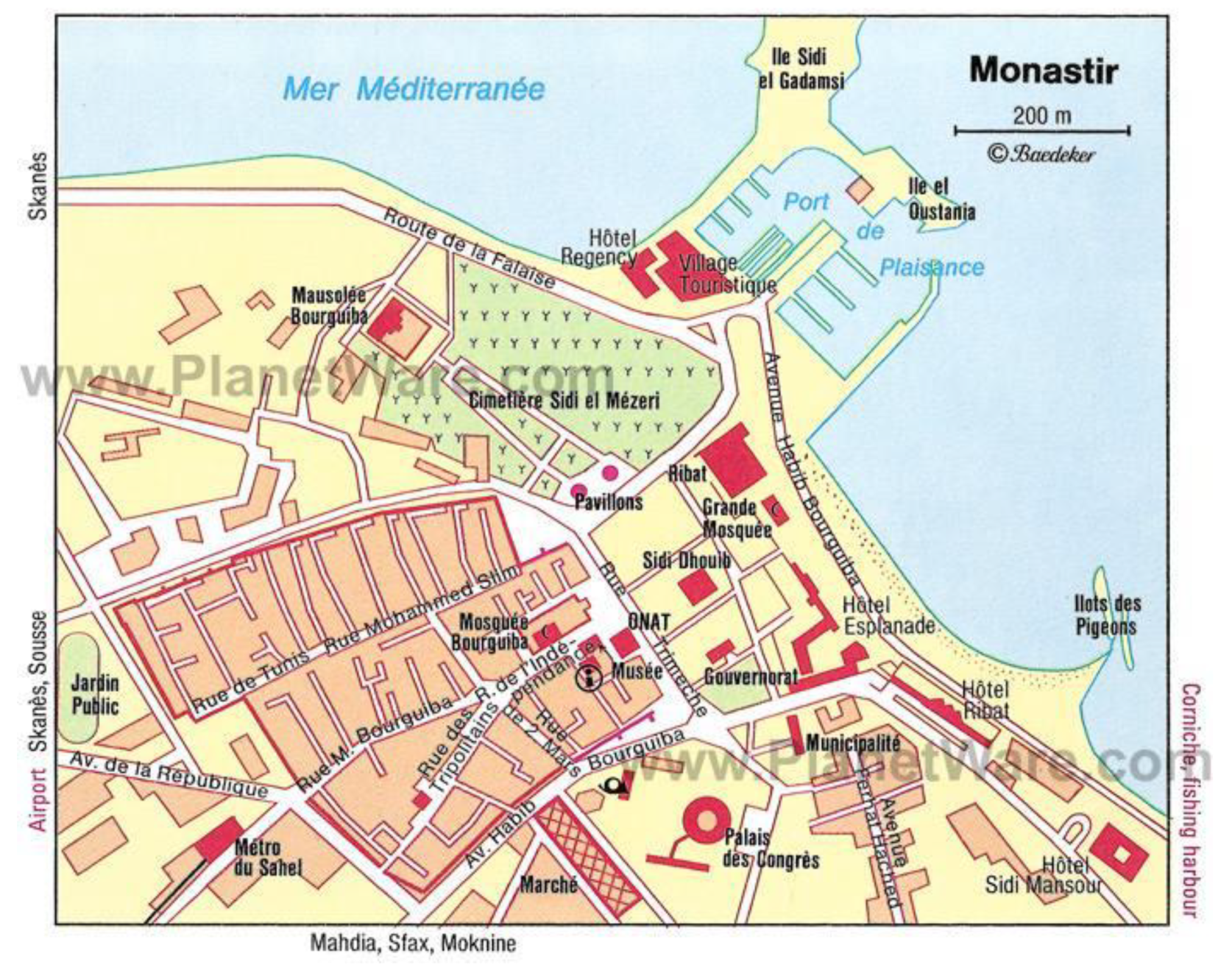

| 11 | http://www.commune-monastir.gov.tn/web/fr/about_ville accessed on 1 August 2021. |

| 12 | http://www.commune-msaken.gov.tn/date.php.html accessed on 1 August 2021. |

| 13 | The few studies available on this town are now dated and no map is available in the website of the Commune de Msaken. Even in Medieval sources, the town is less mentioned than Mahdia or Monastir, when it is not mentioned at all. |

| 14 | It should be noted that for the writing of this contribution I have not included the analysis of speeches performed in a semi-formal style or in mixed Arabic. For Mixed varieties see, among others, (Larcher 2001; Den Heijer 2012), and the Proceedings of the AIMA symposia and relative bibliography: (Lentin and Grand’Henry 2008; Zack and Schippers 2012; Bettini and La Spisa 2012). |

| 15 | These elements will be discussed below. |

| 16 | Baqalṭa, commonly known as Bekalta, is a village 10 km from Mahdia, belonging to the Wilāyat al-Munastīr. |

| 17 | I would like to point out that, in this contribution, my main focus will be Mahdia Arabic and I will only make some brief mentions fo the surrounding varieties. The focus on the latter will be developed in further studies. |

| 18 | See the interesting observations of Van-Mol (2010, pp. 70–77) on satellite tv broadcasts and Nguyen’s (2021) statements on using social media for dialect research which are partially applicable here. |

| 19 | Yoda (2019) defines the appearance of interdentals a classicism. I believe that not only Standard Arabic, but also the Arabic of the capital, Tunis, or of nearby Sousse, influence this realization of interdentals (see (Gibson 2002)). It must be pointed out that Saada (1984, p. 23) stated that the Arabic of Tozeur had “conservation des interdentales à de rares exceptions […] dans les quartiers des Ulǟd el Hǟdef et des Žimaʿ les interdentale sont faibles chez les sujets masculins et féminins” [“retention of interdentals with rare exceptions […] in the Ulǟd el Hǟdef and Žimaʿ districts interdentals are weak in both men and women speakers”. English translation is mine]. See also the note 2 at the same page. |

| 20 | Note that I have chosen to transcribe the article al- with the lateral /l/ also when it is followed by a solar consonant, such as in the cases of al-tēnī (to be read at-tēnī), al-ṯēniya (to be read aṯ- ṯēniya), and al-rās (to be read ar- rās). |

| 21 | Biţuna (2011, p. 28) notes a certain “instability” in the articulation of the interdentals in numerals from 3 to 10. Maura Tarquini gave a paper titled “Le (inter)dentali in arabo tunisino” during the “Prima giornata di dialettologia maghrebina” (Cagliari, 16/05/2019) which has not yet been published. |

| 22 | See also (Vicente 2019, pp. 107–8). |

| 23 | Eventual further information about the occurrence of /q/ and /g/ in Mahdia region will emerge from the interviews that I will carry out as soon as possible, when the sanitary emergency allows it. |

| 24 | For Sfaxi Arabic, see (Lajmi 2009, p. 136). Kerkenna Arabic is a /q/ dialect, except for Mellita variety: see (Herin and Zammit 2017, pp. 140, 142–43). |

| 25 | As underlined also by other scholars, such as Yoda, the Judeo-Arabic of Tunis shares some features with Mahdia Arabic. Therefore, Cohen’s study on this variety will be taken into account in this paper. |

| 26 | See https://tunico.acdh.oeaw.ac.at/dictionary.html?query=flk accessed on 13 August 2021. It is impossible to indicate here all of the videos analyzed for this research, but it may be useful to point out that these data are taken from a documentary realized by Menara Fm in December 2020, dedicated to the quarter of Burž al-rās. It is a 35-min documentary in which examples of many other features described in this paper can be retraced. However, further studies will be needed to clarify the presence and the distribution of the articulation of /k/ as /q/ in Mahdia and the surrounding towns. |

| 27 | It is well known, however, that in Tunisian Arabic the opposition /r/ and /ṛ/ is well established and attested: see (Cohen 1975, vol. 2, pp. 14–15) and (Saada 1984, p. 26). |

| 28 | Out of my own concern for completeness (as far as possible, since a single contribution is far from being an exhaustive study) of information, I have listened to some videos with speakers from Kairouan, taken from Radio Monastir, which have not been inserted in my “official” corpus. |

| 29 | |

| 30 | As far as I know, there are no systematic studies on the degrees of affrication of dental consonants in Tunisian Arabic. Further studies would allow the phenomenon to be described better. |

| 31 | “without any doubt stronger than in Muslim Tunis, which would explain the fact that Muslims who want to imitate Jewish speech exaggerate the emphasis as well as the expressive modulations of the sentence”. English translation is mine. |

| 32 | On the notion of articulatory strength, see for instance (Ladefoged and Maddieson 1996, pp. 95–97). About the influence of the communitarian and identitary dynamics on the Arabic language, see (Mion 2017) on Cypriot Arabic. It should be noticed that in Sicily, which showed a complex cultural and religious situation, according to Lentin (2006/2007, p. 76), “Les «emphatiques» semblent avoir été articulée sans (grande) emphase” [“The ‘emphatics’ seem to have been articulated without (much) emphasis”. English translation is mine]. |

| 33 | What Attia (1969, p. 127) stated about /e/ should be noted: “C’est une voyelle semi-ouverte, avant, brève. Elle représente entre /a/ et /i/ un degré d’aperture absent en Arabe classique. Son absence est distinctive, mais sa longueur ne le semble pas. Allongée, elle tend à se confondre avec le degré d’aperture voisin /i/ ou /a/” [“It is a semi-open, front, short vowel. It represents a degree of aperture between /a/ and /i/ which is absent in classical Arabic. Its absence is distinctive, but its length does not seem to be distinctive. Elongated, it tends to merge with the nearby aperture degree /i/ or /a/”. English translation is mine] and about /o/: “C’est une voyelle semi-ouverte, arrière, brève. Elle représente entre /a/ et /u/ un degré d’aperture absent en Arabe classique. Son absence ne semble pas distinctive. Allongée, elle tend à se confondre avec le degré d’aperture voisin /a/ ou /u/” [“It is a semi-open, back, short vowel. It represents a degree of aperture between /a/ and /u/ which is absent in classical Arabic. Its absence does not seem distinctive. Elongated, it tends to merge with the nearby aperture degree /a/ or /u/”. English translation is mine]. For Attia, these two phonemes in Mahdia Arabic could only be short (see Attia 1969, pp. 128–29). |

| 34 | For the vowel system of Tunisian Judeo-Arabic, see (Cohen 1975, vol. 2, 56–62). |

| 35 | Describing in detail the vowel system of Mahdia Arabic is beyond the scope of this article and will be the subject of future studies. I limit myself to observe that, as shown in the examples given in this paper, in my corpus some cases of /ə/ have been found. On the vocalism of Maghribi Arabic see among others the recent observations of Mion (2018, pp. 112–13) and the relative bibliography. |

| 36 | In fact, Yoda (2019, p. 61, n. 32) states with certainty: “when the preposition fi ‘in’ is followed by the suffix pronoun –ha, the vowels of these two phonemes assimilate to each other: ē > fē-he”. For the phenomenon in the Arabic of Tozeur, see (Saada 1984, pp. 32–33). |

| 37 | For the reduction of etymological diphthongs in Tunis Judeo-Arabic, see (Cohen 1975, vol. 2, p. 68). |

| 38 | “Like the conspecific dialects of Sâḥel, takroûni follows on some points its own paths which, distancing it from the urban dialects of the Regency, bring it closer to certain Bedouin dialects of the eastern Maghreb […]: the old diphthongs ai and au, accented and not in final position, are generally reduced to ē and ō”. English translation is mine. |

| 39 | In Sfaxi Arabic, diphthongs are reduced to /ī/, /ū/ or /ō/ and in Sellami (2019)’s sample they were retained. The scholar also shows that there is a generational difference in how youngsters and aged speakers treat diphthongs. In Kerkenna Arabic, diphthongs are reduced to /ē/ and /ō/ (Herin and Zammit 2017, p. 140). |

| 40 | As for Sahel, Sfaxi Arabic is an exception, especially for medial imāla. See (Sellami 2019). The first variety of Arabic of Kerkenna, described by Herin and Zammit, shows some exceptions since medial imāla of /ā/ is not raised, but final imāla is raised only in monosyllabic words. A second variety shows the raising of final /a/ triggered after non-emphatic front consonants and front vowels. The variety of Mellita raises final /a/. See (Herin and Zammit 2017, pp. 140–41). |

| 41 | Sousse Arabic has inti (Talmoudi 1980, p. 143). |

| 42 | See also (Yoda 2019): passim, in which we find āni “I”, aḥna “we” and inti “you”. For Sousse Arabic, see (Talmoudi 1980, p. 143) and for Tunis Judeo-Arabic, which offers a unique form ənti for the second person singular “you”, (Cohen 1975, pp. 210–11). |

| 43 | See in particular p. XXII, n. 3 on the origins of nǟya/nǟy. |

| 44 | Also the Judeo-Arabic of Tunis shares the use of ellī and variants: see (Cohen 1975, pp. 218–21). In Tozeur, ellī, ella and allomorphs alternate (Saada 1984, p. 79). |

| 45 | See also the comparative study of (Taine-Cheikh 1994). |

| 46 | Some other features indicated by Biţuna are present in the variety of Mahdia and Msaken, such as the use of zūz + plural of the noun, feature already used in Medieval Maghribi Arabic (see (La Rosa 2019, pp. 218–19; Corriente et al. 2015, pp. 110–11), for Msaken Arabic see (Bouhlel 2009, p. 128)), the feminine form of the numerals from 3 to 10 when the numeral in question has the function of an isolated substantive. The use of the indefinite numeral wāḥǝd al- has not been attested. |

| 47 | The word ʿaskar, “soldier” or “army” as a collective, is considered by the speakers both as a singular and as a plural. As for the variety of Sousse, (Talmoudi 1980, p. 139) points out that it has a different vowel quantity. The –n form in numerals from 11 to 19 is also present (Talmoudi 1980, p. 140). |

| 48 | The same happens in many Tunisian coastal vernaculars, such as Sfaxi Arabic: see (Sellami 2019), and in Tunis Judeo-Arabic, see (Cohen 1975, p. 104). |

| 49 | In Kairouan, we find nistennu “we wait for”. Information taken from some videos of the page Radio Monastir. |

| 50 | In Bekalta, I found the example nistennēw w-mā nensūhum “we wait and we do not forget them”, so further research on the varieties spoken in the region will be necessary to sketch a more precise map of the distribution of this feature. |

| 51 | The feature, of course, is also shared by Tunis Judeo-Arabic (Cohen 1975, p. 104). |

| 52 | “Labelling a dialect as conservative […] means that it exibits a certain degree of stability over time: certain features are less likely to evolve because there are fewer exogenous factors that could lead to change” (Herin 2019, pp. 94–95). |

| 53 | https://tunico.acdh.oeaw.ac.at/dictionary.html?query=%22to%20see%22 accessed on 13 August 2021. |

| 54 | “created, without any doubt, under the analogical influence of the passive-reflexives with initial t- of forms V and VI, which proceede respectively from forms II and V, this stem proceeds from verbs of the first form generally in use. It constitutes its passive-reflexive”. English translation is mine. |

| 55 | For Sousse, see (Talmoudi 1980, p. 101). See also (Saada 1984, pp. 57–58) who finds the phenomenon in Tozeur. |

| 56 | “It seems that a question remains: the value of the distinction between Hilali vs Sulaymi vs Maʿqili dialects. If there are indeed groups of more or less differentiated varieties and if it is necessary to give them a name, I am not sure that these three designations of socio-historical origin are really precise and of real help”. English translation is mine. |

| 57 | [“While -īw from Morocco to Tunisia should be seen as sedentary and urban, a transversal system with a perfect tense in -/āw/ and an imperfect tense in -/ū/ is in fact much more frequent than the simple methodological opposition pre-Hilalian/Hilalian would suggest. If this system has to be conceived as transitional within a continuum whose two poles would be precisely the pre-Hilalian/hilalian typologies, then much of Tunisia (with the exception of its metropolises and Marāzīg varieties) should paradoxically be considered a transitional zone”. English translation is mine]. The verb nensū attested in Bekalta has to be verified and supported with other occurences to verify whether the varieties near Mahdia have any mixed features. |

| 58 | The critical issues of the application of this criterion of classification have already been underlined in the relative paragraph in the section devoted to phonology. |

| 59 | The already mentioned paper by Maura Tarquini seemed to confirm this trend. |

| 60 | The voiceless realization of /q/ was the norm in Medieval Arab cities and in the recitation of the Koran. For this reason, it must have always been considered a positive element by speakers. This encouraged the spread of the variant in the Arab world via the Maghrib. See (Vicente 2019, p. 109). |

| 61 | I wonder whether the preservation of the monophthongs /ī/ and /ū/ in the Arabic of Mahdia and the surrounding towns must be included in these elements. |

| 62 | An example is Nizar Chaari’s novel Tūnis fī ʿīnayya, in which the author inserts additional texts and materials downloadable on one’s own smartphone through a QR code. His aim was to involve young people in reading and making it attractive to them, by giving them the opportunity to do it wherever and whenever they want through their smartphone. See (La Rosa forthcoming). |

| 63 | Such an analysis on the influence of the medium (radio and video) on the variety of Arabic used by the speakers involved in the videos selected will be the object of future studies. In fact, in the wider framework of the ongoing studies on the features of contemporary Media Arabic, observing how the varieties of Arabic are used in Tunisia could help describe more precisely the complex situation of linguistic variation in the country. On this subject, see for instance the PhD thesis “Arabe Mixte 2.0: la variation syntaxique et stylistique dans les journaux numériques marocains (janvier-décembre 2016)”, defended by Rosa Pennisi in December 2020. |

References

- Attia, Abdelmajid. 1969. Le parler de Mahdia. In Travaux de Phonologie. Parlers de: Djemmal, Gabes, Mahdia (Tunisie), Treviso (Italie). Edited by Taieb Baccouche, Hichem Skik, Abdelmajid Attia and Mohamed El Habib Ounali. Tunis: Centre d’etudes Économiques et Sociales, pp. 116–38. [Google Scholar]

- Avram, Andrei. 2012. Some phonological changes in Maltese reflected in onomastics. Bucharest Working Papers in Linguistics 14: 99–119. [Google Scholar]

- Bearman, Peri, Thierry Bianquis, Clifford Edmund Bosworth, Emery van Donzel, and Wolfhart P. Heinrichs, eds. 1986. Ḳul-Og̲h̲lu. In Encyclopaedia of Islam, 2nd ed. Consulted online on June 9 2021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benkato, Adam. 2019. From Medieval Tribes to Modern Dialects: On the Afterlives of Colonial Knowledge in Arabic Dialectology. Philological Encounters 4: 2–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bettini, Lidia, and Paolo La Spisa, eds. 2012. Au-delà de l’arabe Standard. Moyen arabe et Arabe mixte dans les Sources Médiévales, Modernes et Contemporaines. Quaderni di Semitistica. Firenze: Università di Firenze, vol. 28. [Google Scholar]

- Biţuna, Gabriel. 2011. The Morpho-Syntax of the Numeral in the Spoken Arabic of Tunis. Romano-Arabica 8–11: 25–42. [Google Scholar]

- Boubakri, Hassan, and Ridha Lamine. 1992. Migrations pendulaires autour de M’saken. Revue Tunisienne de Géographie 19–20: 11–29. [Google Scholar]

- Bresc, Henri, and Annliese Nef. 1999. La première géographie de l’Occident. Présentation, Notes, Index, Chronologie et Bibliographie. Traduction du Chevalier Jaubert, revue par Annliese Nef. Paris: Flammarion. [Google Scholar]

- Bouhlel, Ezzeddine. 2009. Le Parler m’sakenien. Synergies Tunisie 1: 125–34. [Google Scholar]

- Bournand, François. 1893. Tunisie et Tunisiens. Paris: Taffin-Lefort. [Google Scholar]

- Burgaretta, Dario. 2016. Un’elegia in giudeo-arabo di Sicilia per il massacro di Noto e Modica del 1474 (Ms. Parm. 1741 della Biblioteca Palatina di Parma). Sefer Yuḥasin 4: 7–194. [Google Scholar]

- Cantineau, Jean. 1960. Cours de Phonétique Arabe. Notions Générales de Phonétique et Phonologie. Paris: Librairie Kliencksieck. [Google Scholar]

- Carter, Michael G. 2007. Elision. In Encyclopedia of Arabic Languages and Linguistics. Edited by Kees Versteegh. Leiden and Boston: Brill, vol. 2, pp. 16–18. [Google Scholar]

- Cohen, David. 1969. Sur le statut phonologique de l’emphase en arabe. Word 25: 59–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cohen, David. 1975. Le parler arabe des Juifs de Tunis. Tome II. Étude Linguistique. Paris: Mouton. [Google Scholar]

- Corriente, Federico, Christophe Pereira, and Ángeles Vicente. 2015. Aperçu Grammatical Du faisceau Dialectal arabe Andalou. Perspectives Synchroniques, Diachroniques et Panchroniques. Encyclopédie linguistique d’al-Andalus. Berlin and Boston: De Gruyter, vol. 1. [Google Scholar]

- Corriente, Federico, Christophe Pereira, and Ángeles Vicente. 2017. Dictionnaire du Faisceau Dialectal Arabe Andalou. Perspectives Phraséologiques et Étymologique. Encyclopédie Linguistique d’al-Andalus. Berlin and Boston: De Gruyter, vol. 2. [Google Scholar]

- Dallaji, Ines. 2017. Grammatical and Lexical Notes on the Arabic Dialect of Nabeul (Northern Tunisia). In Lisan Al-Arab. Studies in Arabic Dialects. Proceedings of the 10th International Conference of AIDA Qatar University 2013. Edited by Muntasir Fayez Faris Al-Hamad, Rizwan Ahmad and Hafid I. Alaoui. Lit: Zurich, pp. 151–62. [Google Scholar]

- D’Anna, Luca. 2017. Italiano, siciliano e arabo in contatto. Profilo sociolinguistico dela comunità tunisina di Mazara del Vallo. Palermo: Centro di Studi Filologici e Linguistici Siciliani. [Google Scholar]

- D’Anna, Luca. 2020. The Arabic dialect of Chebba: Preliminary data and historical considerations. Zeitschrift für Arabische Linguistik 72: 80–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Decret, François. 2003. Les Invasions Hilaliennes en Ifrîqiya. Office National des Statistiques pour la Population et la Démographie. Available online: https://www.clio.fr/bibliotheque/les_invasions_hilaliennes_en_ifriqiya.asp (accessed on 11 August 2021).

- Den Heijer, Johannes. 2012. Introduction: Middle and Mixed Arabic, A New Trend in Arabic Studies. In Middle Arabic and Mixed Arabic. Diachrony and Synchrony. Edited by Liesbeth Zack and Arie Schippers. Leiden: Brill, pp. 1–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferrando, Ignacio. 1995. El dialecto andalusí de la Marca Media. Los Documentos Mozárabes Toledanos de los Siglos XII y XIII. Zaragoza: Universidad de Zaragoza (Area de estudios Arabes e Islámicos 4). [Google Scholar]

- Ghazeli, Salem. 1981. La Coarticulation de l’Emphase En Arabe. Arabica 28: 251–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gibson, Maik. 2002. Dialect Levelling in Tunisian Arabic: Towards a New Spoken Standard. In Language Contact and Language Conflict in Arabic. Variations on a Sociolinguistic Theme. Edited by Rouchdy Aleya. Oxon and New York: Routledge, pp. 24–40. [Google Scholar]

- Gibson, Micheal Luke. 1998. Dialect Contact in Tunisian Arabic: Sociolinguistic and Structural Aspects. Ph.D. thesis, University of Reading, Reading, UK. [Google Scholar]

- Goitein, Shelomo Dov. 2010. Studies in Islamic History and Institutions. Brill Classics in Islam. With an Introduction by Norman A. Stillman. Leiden and Boston: Brill, vol. 5. [Google Scholar]

- Gouma, Taoufik. 2013. L’emphase en Arabe Marocain: Vers une Analyse Autosegmentale. Ph.D. thesis, Université de Paris 8, Paris, France. [Google Scholar]

- Guerrero, Jairo. 2018. Les parlers Jbala-villageois. Étude grammAticale d’une Typologie rurale de l’arabe Dialectal Maghrébin. Dialectologia 20: 85–105. Available online: https://hal.archives-ouvertes.fr/hal-02095906 (accessed on 1 August 2021).

- Herin, Bruno. 2019. Traditional Dialects. In The Routledge Handbook of Arabic Sociolinguistics. Edited by Enam Al-Wer and Uri Horesh. London and New York: Routledge, pp. 93–105. [Google Scholar]

- Herin, Bruno, and Martin Zammit. 2017. Three for the Price of One: The Dialects of Kerkennah (Tunisia). In Tunisian and Libyan Arabic Dialects. Common Trends—Recent Developments –Diachronic Aspects. Edited by Veronika Ritt-Benmimoun. Zaragoza: Prensas de la Universidad de Zaragoza, pp. 135–46. [Google Scholar]

- Ladefoged, Peter, and Ian Maddieson. 1996. The Sounds of the World’s Languages. Oxford: Blackpowell. [Google Scholar]

- Lajmi, Dhouha. 2009. Spécificités du dialecte Sfaxien. Synergies Tunisie 1: 135–42. [Google Scholar]

- Larcher, Pierre. 2001. Moyen Arabe et Arabe Moyen. Arabica 48: 578–609. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- La Rosa, Cristina. 2018. Alcune strategie retoriche nel discorso politico tunisino: Uso dei deittici e ripetizione lessicale. La rivista di Arablit 15: 67–92. [Google Scholar]

- La Rosa, Cristina. 2019. L’arabo di Sicilia nel Contesto Maghrebino: Nuove Prospettive di Ricerca. La Sicilia Islamica: Testi, Ricerche Letterarie e Linguistiche. Roma: Istituto Per l’Oriente Carlo Alfonso Nallino, vol. 1. [Google Scholar]

- La Rosa, Cristina. Forthcoming. Tūnis fī ʿīnayya by Nizār al-Šaʿarī: Al-Dāriǧa al-Tūnisiyya between Resistance and Hypertextuality. In Studies on Arabic Dialectology and Sociolinguistics. Proceedings of the 13th International Conference of AIDA held in Kutaisi in June 10–13. Edited by GuramGuram Chikovani and Zviad Tskhvediani. Kutaisi: Akaki Tsereteli State University Press, pp. 410–21.

- Lentin, Jérȏme. 2006/2007. L’arabe parlé en Sicile était-il un arabe périphérique? Romano-Arabica 6–7: 71–84. [Google Scholar]

- Lentin, Jérȏme, and Jacques GrandHenry ’, eds. 2008. Moyen Arabe et Variétés Mixtes de l’arabe À travers l’histoire. Actes du Premier colloque International (Louvain-la-Neuve, 10–14 mai 2004). Publications de l’Institut Orientaliste de Louvain. Louvain-la-Neuve: Institut Orientaliste de Louvain, vol. 58. [Google Scholar]

- Maamouri, Mohamed. 1967. The Phonology of Tunisian Arabic. Ph.D. dissertation, Cornell University, Ithaca, NY, USA. [Google Scholar]

- Ma Mung, Emmanuel. 1984. L’impact des transferts migratoires dans la ville de M’saken (Tunisie). Revue Européenne des Migrations Internationals 2: 163–78. Available online: https://www.persee.fr/doc/remi_0765-0752_1986_num_2_1_1001 (accessed on 28 May 2021). [CrossRef]

- Marçais, Philippe. 1977. Esquisse grammaticale de l’arabe maghrébin. Paris: Maisonneuve. [Google Scholar]

- Marçais, William. 1950. Les parlers arabes. In Initiation à la Tunisie. Edited by André Basset. Paris: Maisonneuve, pp. 195–219. [Google Scholar]

- Marçais, William, and Abderrahmâne Guiga. 1925. Textes arabes de Takroûna. Textes, Transcription et Traduction annotée. Paris: Imprimerie Nationale, Leroux. [Google Scholar]

- Marçais, William, and Abderrahmâne Guiga. 1958. Textes Arabes de Takroûna. Contribution à L’étude du Vocabulaire arabe. Glossaire. Paris: Imprimerie Nationale, Librairie Orientaliste Paul Geuthner. [Google Scholar]

- Mion, Giuliano. 2015. Réflexions sur la catégorie des ‘parlers villageois’ en arabe tunisien. Romano-Arabica 15: 269–77. [Google Scholar]

- Mion, Giuliano. 2017. Un arabo cipriota romanizzato? Distacchi e identità fra variazione scrittoria e confessione religiosa. In Aspetti della Variazione Linguistica. Discorso, Sistema, Repertori. Edited by Carlo Consani. Milan: LED, pp. 83–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mion, Giuliano. 2018. Pré-hilalien, hilalien, zones de transition. Relire quelques classiques aujourd’hui. In Mediterranean Contaminations. Middle East, North Africa, and Europe in Contact. Edited by Giuliano Mion. Berlin: Klaus Schwarz Verlag, pp. 102–25. [Google Scholar]

- Nguyen, Dong. 2021. Dialect Variation on Social Media. Pre-print. Forthcoming in Similar Languages, Varieties, and Dialects. (Studies in Natural Language Processing Series); Edited by Marcos Zampieri and Preslav Nakov. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Ritt-Benmimoun, Veronika. 2014. The Tunisian Hilāl and Sulaym Dialects. A Preliminary Comparative Study. In Alf lahǧa wa lahǧa Lit-Verlag Proceedings of the 9th AIDA Conference. Edited by Olivier Durand, Angela Daiana Langone, and Giuliano Mion. Münster and Wien: Lit-Verlag, pp. 351–60. [Google Scholar]

- Saada, Lucienne. 1984. Eléments de Description du Parler arabe de Tozeur (Tunisie). Paris: Geuthner. [Google Scholar]

- Sayahi, Lotfi. 2019. Diglossia and the normalization of the vernacular. Focus on Tunisia. In The Routledge Handbook of Arabic Sociolinguistics. Edited by Enam Al-Wer and Uri Horesh. London and New York: Routledge, pp. 227–39. [Google Scholar]

- Sellami, Zeineb. 2019. The Dialect of Sfax (Tunisia). In Studies on Arabic Dialectology and Sociolinguistics: Proceedings of the 12th International Conference of AIDA held in Marseille from May 30th to June 2nd 2017 [online]. Aix-en-Provence: Institut de Recherches et D’études sur les Mondes Arabes et Musulmans. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Skik, Hichem. 2000. La prononciation de qâf arabe en Tunisie. In Proceedings of the Third International Conference of Aïda. Edited by Manwel Mifsud. Malta: pp. 131–36. [Google Scholar]

- Soucek, Svat. 1993. Monastir. In Encyclopaedia of Islam, 2nd ed. Edited by Clifford Edmund Bosworth, Emery van Donzel, Wolfhart P. Heinrichs and Charles Pellat. Leiden: Brill, vol. 7, pp. 227–29. [Google Scholar]

- Taïeb, Jacques, and Mansour Sayah. 2003. Remarques sur le parler judéo-arabe de Tunisie. Diasporas. Histoire Et Sociétés 2: 5–64. Available online: https://www.persee.fr/doc/diasp_1637-5823_2003_num_2_1_878 (accessed on 5 May 2021).

- Taine-Cheikh, Catherine. 1994. Les numéraux cardinaux de 3 à 10 dans les dialectes arabes. In Actes des Premières Journées Internationales de Dialectologie Arabe de Paris. Edited by Dominique Caubet and Martine Vanhove. Paris: INALCO, pp. 251–66. [Google Scholar]

- Taine-Cheikh, Catherine. 2017. La classification des parlers bédouins du Maghreb: Revisiter le classement traditionnel. In Tunisian and Libyan Arabic Dialects: Common Trends, Recent Developments, Diachronic Aspects. Edited by Prensas Universitarias de Zaragoza. Zaragoza: Prensas de la Universidad de Zaragoza, pp. 15–42. [Google Scholar]

- Talbi, Mohamed. 1986. "al-Mahdiyya". In Encyclopaedia of Islam, 2nd ed. Edited by Clifford Edmund Bosworth, Emery van Donzel, Wolfhart P. Heinrichs and Charles Pellat. Leiden: Brill, vol. 5, pp. 1245–47. [Google Scholar]

- Talmoudi, Fathi. 1980. The Arabic Dialect of Sūsa (Tunisia). Göteborg: Acta Universitatis Gothoburgensis. [Google Scholar]

- Van-Mol, Marc. 2010. Oral Media and Corpus Linguistics: A First Methodological Outline. In Arabic and the Media: Linguistic Analyses and Application. Edited by Reem Bassiouney. Leiden and Boston: Brill, pp. 63–80. [Google Scholar]

- Vicente, Ángeles. 2019. Dialect contact and urban dialects. In The Routledge Handbook of Arabic Sociolinguistics. Edited by Enam Al-Wer and Uri Horesh. London and New York: Routledge, pp. 106–16. [Google Scholar]

- Voisins d’Ambre, Anne Caroline. 1884. Excursions d’une Française dans la Régence de Tunis par Mme de Voisins (Pierre-Coeur). Paris: Dreyfous. [Google Scholar]

- Yoda, Sumikazu. 2008. On the Vowel System of the al-Mahdīyya Dialect of Central Tunisia. In Between the Atlantic and Indian Oceans. Studies on Contemporary Arabic Dialects. Proceedings of the 7th Aida Confer-ence, Held in Vienna from 5–9 September 2006. Edited by Stephan Procházka and Veronika Ritt-Benmimoun. Münster and Wien: Lit-Verlag, pp. 483–90. [Google Scholar]

- Yoda, Sumikazu. 2019. Texts from Mahdīyya. Journal of Arabic and Islamic Studies 17: 55–70. [Google Scholar]

- Zack, Liesbeth, and Arie Schippers. 2012. Middle Arabic and Mixed Arabic. Diachrony and Synchrony. Leiden and Boston: Brill. [Google Scholar]

- Zammit, Martin. 2014. The Sfaxi Tunisian Element in Maltese. In Perspectives on Maltese Lingusitics. Edited by Albert Borg, Sandro Caruana and Alexandra Vella. Berlin: De Gruyter, pp. 23–44. [Google Scholar]

| Pronoun | Mahdia | Monastir | Msaken | Bekalta |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 p. s. | ǟni | ǟni | ǟni | ǟni/āni |

| 1 p. p. | aḥna/naḥna | aḥna | aḥna/naḥna | naḥna |

| 2 p. s. | ǝnti/inti41 | ǝnti | ǝnti | ǝnti/inti |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

La Rosa, C. Mahdia Dialect: An Urban Vernacular in the Tunisian Sahel Context. Languages 2021, 6, 145. https://doi.org/10.3390/languages6030145

La Rosa C. Mahdia Dialect: An Urban Vernacular in the Tunisian Sahel Context. Languages. 2021; 6(3):145. https://doi.org/10.3390/languages6030145

Chicago/Turabian StyleLa Rosa, Cristina. 2021. "Mahdia Dialect: An Urban Vernacular in the Tunisian Sahel Context" Languages 6, no. 3: 145. https://doi.org/10.3390/languages6030145

APA StyleLa Rosa, C. (2021). Mahdia Dialect: An Urban Vernacular in the Tunisian Sahel Context. Languages, 6(3), 145. https://doi.org/10.3390/languages6030145