Abstract

Spanish marks animate and specific direct objects overtly with the preposition a, an instance of Differential Object Marking (DOM). However, in some varieties of Spanish, DOM is advancing to inanimate objects. Language change starts at the individual level, but how does it start? What manifestation of linguistic knowledge does it affect? This study traced this innovative use of DOM in oral production, grammaticality judgments and on-line comprehension (reading task with eye-tracking) in the Spanish of Mexico. Thirty-four native speakers (ages 18–22) from the southeast of Mexico participated in the study. Results showed that the incidence of the innovative use of DOM with inanimate objects varied by task: DOM innovations were detected in on-line processing more than in grammaticality judgments and oral production. Our results support the hypothesis that language variation and change may start with on-line comprehension.

1. Introduction

One of the central goals of linguistic theory is to understand the abstract linguistic knowledge of native speakers (Chomsky 1965). This is complicated by the fact that such knowledge is not always stable: languages are dynamic systems constantly changing and evolving to adapt to speakers’ needs and environments (Aitchison 2001; McMahon 1994; Bauer 1994). Subtle linguistic changes occur at every language level: phonological (Baugh and Cable 1978; Archibald 2000), syntactic (Baugh and Cable 1978), morphological (Fischer et al. 2000), lexical and semantic (Banks 2004). However, linguistic changes are always preceded by a period of language variation (Chambers 2002). During the time that a new form is spreading and becoming more frequently used in a community, speakers use both the “innovative” form and the “old” form for expressing an equivalent meaning. In some situations, there is a free variation on the use of one form over the other one; in other situations, there can be a new functional distinction between the “innovative” and the “old form”, or the old form can cease to be used entirely and the change goes to completion. While all these three contexts can be understood as cases of language change and could be called “change in progress”, only the last can be called a “completed change” (Léglise and Chamoreau 2013).

In order to understand why language variation occurs and why it sometimes, but not always, leads to language change, extensive research has been conducted on language variation from a sociolinguistic perspective (Weinreich et al. 1968; Labov 1972, 1994; Eckert 2005; Shin 2014). Sociolinguistic research on variation usually focuses on the community level, and investigates how new variants correlate with external, social factors, such as age, gender, region, and socioeconomic status, among others. For example, young people may begin using a new variant that is used less by older people, or women may use a new variant that is less frequently used by men, and so on. However, sociolinguists have also analyzed the influence of internal, linguistic factors related to grammar, such as type of verb, word order, animacy, etc. Therefore, sociolinguistic research on variation aims to understand why language variation and language change occur by studying different communities or groups of people. The underlying assumption is that language variation and language change are not random but systematic and rule-governed (Labov 2001). Therefore, whenever speakers have linguistic options available, their choice is influenced by internal and/or external factors (Sankoff 1988).

Sociolinguistic research on language variation has predominantly been based on speakers’ language production, such as small corpora of recorded conversations elicited from sociolinguistic interviews. The interviews are used to analyze whether a specific community or group of people use new forms, and if so, when and why. While informative, sociolinguistic interviews have limitations. Depending on whether the interview is more or less formal, participants may produce individual forms (variants), which may vary from their everyday use of the language. Moreover, if only a few productions of an innovative variety occur in the data, it is hard to tell whether these were one-off occurrences or whether these few productions are more systematic/frequent. Finally, using one variant over another does not necessarily mean that the other variant is not represented in the speaker’s linguistic knowledge or is unacceptable for the speaker. For example, the fact that someone produces Je veux pas “I don’t want” in French does not mean that he or she does not accept or use Je ne veux pas (with negative ne before the verb) in other contexts. Other sociolinguistic studies use written corpora, such as newspapers or magazines. Although such corpora can be useful, newspapers or other written sources tend to use the standard written register.

Controlled elicitation tasks provide a methodological alternative that can circumvent some of the limitations of sociolinguistic interviews, as they elicit the target forms directly and most efficiently from a group of speakers (Schilling 2013). Because all participants are asked to complete the same task with the same variables, it is easier to determine whether only some or almost all of the participants produce the same variants. However, as with the naturalistic data collected in sociolinguistic interviews, controlled elicitation tasks only provide information about what participants actually produce while completing the task, but cannot tell anything about whether alternative forms are acceptable for the speaker. For example, Silva-Corvalán (1994) investigated language variation and change in the Spanish of Los Angeles using a sociolinguistic interview and other oral elicitation measures that involved sentence completion and translation to elicit different verb tenses.

To obtain a more detailed picture of linguistic knowledge, it is common in monolingual and bilingual psycholinguistics to use a variety of complementary productive and receptive measures that tap into processing, comprehension, production and intuitions (Kim et al. 2018; Perez-Cortes et al. 2019). In this study, we advocate for this approach to trace incipient language variation and change in a monolingual variety. Using psycholinguistic tasks together with oral production tasks offers new tools to investigate language variation of subtle and measurable linguistic variation at the individual level, that can then spread to society. Psycholinguistic methodologies may allow us to pinpoint how language variation arises in different language skills (comprehension and production). By focusing on the cognitive and linguistic processing and representations at the individual level, psycholinguistic approaches bring a level of granularity not typically seen in studies of language change and deeper understanding promises to lead to new insights to explain language variation. Since so little is known about the way in which language variation is cognitively represented at the individual level, in this study, we use psycholinguistic methodologies to investigate how Differential Object Marking (DOM) might be spreading to inanimate objects in Mexican Spanish. Previous studies have documented DOM variation in some written and spoken varieties of Spanish (Von Heusinger and Kaiser 2005; Tippets 2010; Bautista Maldonado and Montrul 2019), but our study is unique in looking at DOM variation in native speakers with different but complementary experimental tasks to obtain a more complete picture of DOM. We are able to demonstrate the need to draw on both types of data in assessing linguistic knowledge and change. Therefore, this study contributes to the study of language change from a sociolinguistics perspective by adding psycholinguistics methods.

It must be acknowledged that psycholinguistic methodologies have limitations as well. Judgment tasks have been criticized for being too explicit and procuring answers that may not reflect participants’ everyday use of the language. Explicit knowledge refers to what is learned with awareness and usually with conscious effort (DeKeyser 2003; Hulstijn 2005; Williams 2009). When judging sentences, participants may rely on prescriptive rules rather than on what they would actually say. Other tasks are assumed to tap into speakers’ implicit knowledge learned incidentally and usually without conscious effort (DeKeyser 2003; Hulstijn 2005; Williams 2009). These include methodologies such as event-related brain potentials (ERP), eye-tracking, or self-paced reading that measure speed of responses and can inform how participants process and respond to language variation. For example, we can establish whether the speakers still rely on the old variant, on both the old and new variants, or whether the old variant is no longer part of the speakers’ competence. More importantly, combining production data with on-line comprehension data can reveal discrepancies in usage and comprehension, or how comprehension is affected in relation to production.

Comprehension and production share the computational goals of accessing and building grammatical structure for licensing grammatical requirements, such as case and thematic requirements. However, they rely on independent cognitive mechanisms: predictive processing in parsing in comprehension versus advanced planning in generation in production (Clifton et al. 2013). Assuming that grammar feeds the parser, it is still unclear whether an asymmetry exists between adult native speakers’ oral production, comprehension and processing strategies. While some studies suggest that oral and even comprehension errors are due to processing deficits (Clahsen and Felser 2006), others posit that dissociation can exist between the production and the comprehension system (Perpiñán 2015). In a study of resumptive pronouns in relative clause island constructions, Ferreira and Swets (2005) found that participants judged sentences as unacceptable, while, at the same time, they produced the sentences as if they were correct; different processing channels seem to access different linguistic information. In some cases, the information accessed during sentence comprehension is not yet available for the production system.

Our results will show that native speakers of Mexican Spanish exhibit the innovative uses of DOM with animate objects in on-line sentence comprehension but not yet in oral production, suggesting that language change may manifest first in comprehension, and then in production or other linguistic behavior (Czypionka and Kupisch 2019; Lundquist et al. 2016). Before describing the details of the experiments, we describe Differential Object Marking in Spanish.

1.1. Spanish Differential Object Marking

Differential Object Marking (DOM) is a phenomenon found in a large number of languages (Bossong 1991; Sinnemäki 2014) in which the case marking of the object noun phrase (NP) is determined by certain semantic factors. Concepts such as animacy, definiteness, specificity and topicality, among others, are often cited to explain the semantic contribution of the case marker in languages with DOM. In Spanish, DOM is represented by the marker ‘a’. In most linguistic and normative descriptions of Spanish, the prototypical case of DOM is to mark animate/human specific objects, as in (1a), but not specific and inanmate objects, as in (1b).1

| (1) | |||

| (a) | María vio | a | Juan. |

| María | saw | DOM Juan | |

| ‘María saw Juan.’ | |||

| (b) | María | vio | el programa. |

| María | saw | the TV show | |

| ‘María saw the TV show.’ | |||

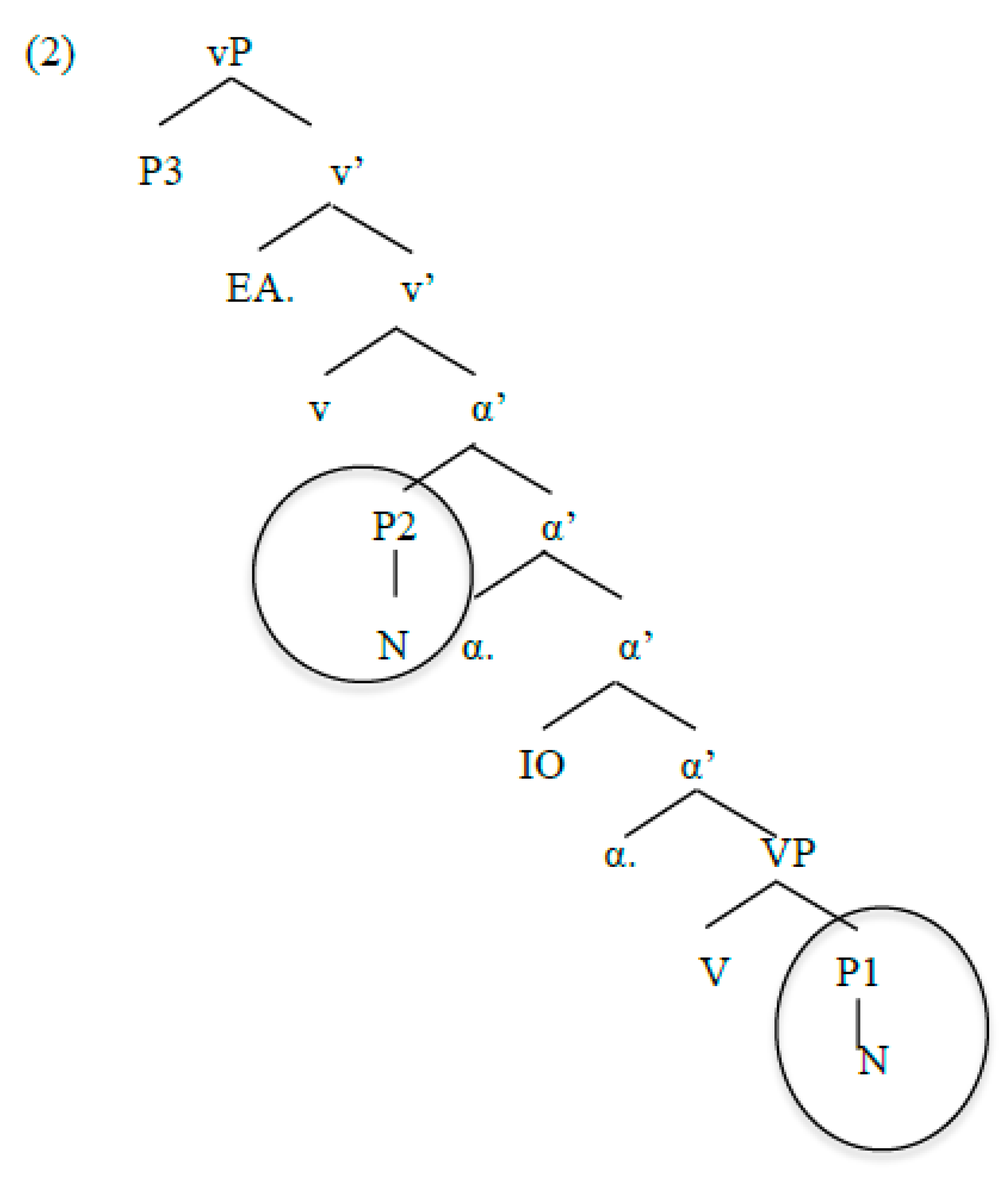

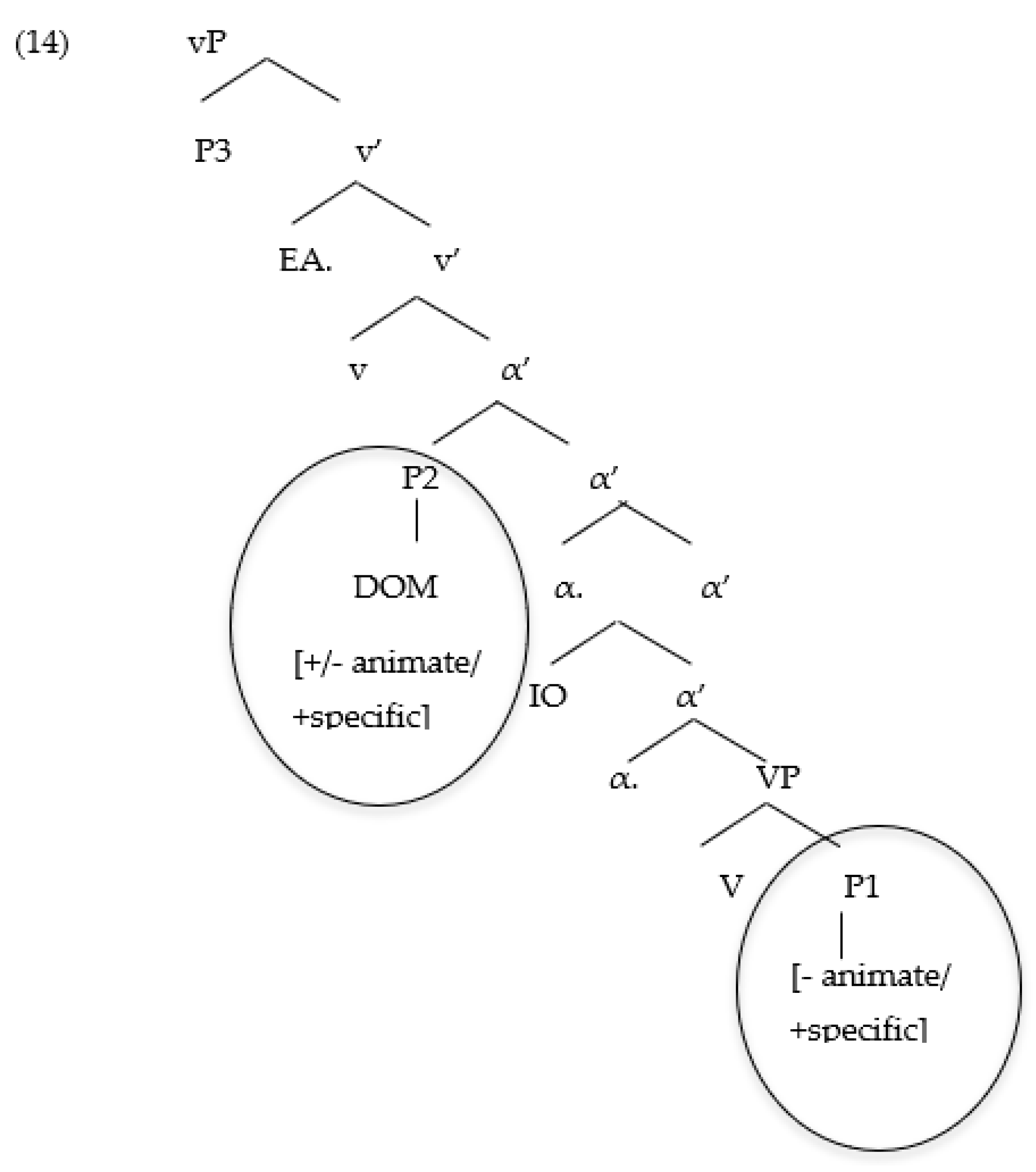

The structure in (2) is what López (2012, p. 45) proposes for the projection of animate and inanimate objects in Spanish: P1 is the position for inanimate objects and P2, above the VP, is the position for marked animate, specific objects.

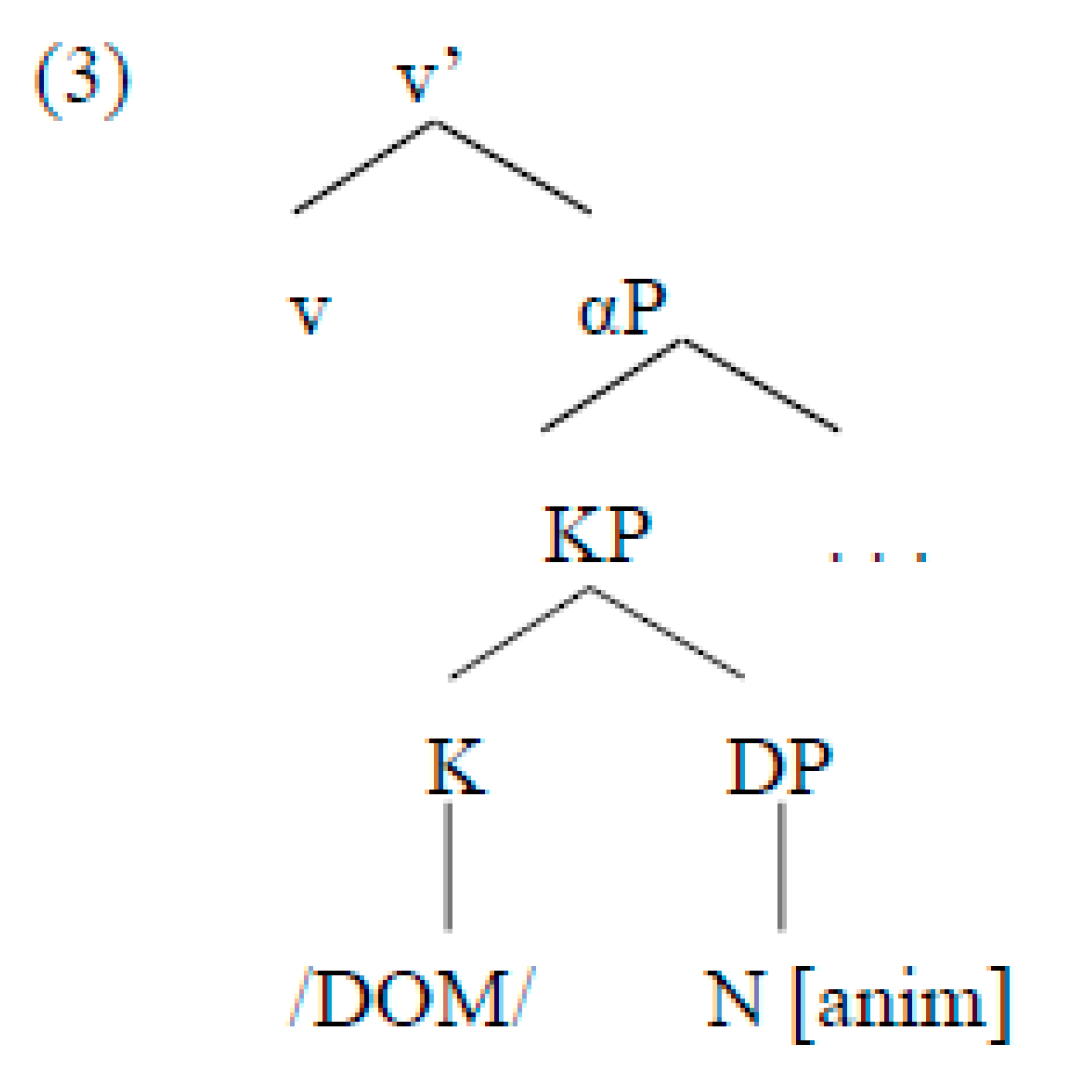

López (2012, p. 64) further proposes that animate specific direct objects in Spanish in P2 are headed by KP, a case phrase as in (3). DOM is the vocabulary item inserted in the K head when v governs K. The spelling out of K can be influenced by the features of NP selected by K (animate), but also by features of v or of α.

However, some speakers omit DOM in required contexts, while others extend DOM to inanimate contexts. Omission of DOM in required contexts has been widely documented in Spanish in contact with English (Montrul 2004; Montrul and Bowles 2009; Montrul and Sánchez-Walker 2013; Cuza et al. 2018) and in Caribbean varieties (Alfaraz 2011). Extension of DOM to inanimate objects has been attested in monolingual varieties (Company 2002; Von Heusinger and Kaiser 2005; Montrul and Sánchez-Walker 2013; Bautista Maldonado and Montrul 2019): a sentence such as El niño vio al carro ‘The child saw the car’ may be acceptable to speakers of Mexican Spanish, while speakers of other dialects (e.g., Peninsular Spanish) may reject that same sentence (Von Heusinger and Kaiser 2007). Moreover, Rodríguez-Ordóñez (2017) showed that DOM can emerge as an innovation in Basque–Spanish bilinguals living in Spain and Yager et al. (2015) found similar results with heritage speakers of German living the United States. All these studies describe that in situations of language contact, we find DOM variation and evolution.

Spanish DOM is a diachronic development. In Latin, direct objects were marked with the accusative case but no preposition. In Medieval Spanish, common noun phrases referring to humans, both definite and indefinite, were not always marked, as shown in (4), whereas today, they must be marked, as in (5) (Aissen 2003).

| (4) quando dexaron mis fijas en el rrobredo de Corpes CMC 3151 | |

| ‘when they left my daughters in the oak-forest of Corpes’ | |

| (5) . . . cuando dejaron a mis hijas en el robledo de Corpes. | |

| ‘when they left DOM my daughters in the oak-forest of Corpes’ | |

Diachronic studies (Laca 2006) show that a-marking is also advancing with inanimate objects in some Spanish varieties, such as Mexican Spanish, as in (6) and (7) (examples from Company 2002, p. 147).

| (6) Después de conocer mucho a la vida, ya no me interesa el teatro. (Proceso, May 1999) | |

| ‘After knowing life too much, I am no longer interested in theater.’ | |

| (7) Para que no nos peleemos, puse a la silla en el medio. (Mexico, spoken Spanish) | |

| ‘So that we do not fight, I put the chair in the middle.’ | |

Von Heusinger and Kaiser (2005) traced the evolution of Spanish DOM in corpora from the Poema de Mio Cid and its contemporary translations, and conducted a synchronic analysis of different varieties of Spanish (Argentina, Uruguay, Peru, Mexico) from written and oral corpora (informal interviews, short stories, and email messages to a newspaper). Their goal was to establish whether the evolution of DOM in Spanish (both old Spanish and different Latin American varieties) followed the Definiteness and Animacy scales. The main finding was that in the transition from Old to Modern Spanish, topicality and specificity were the triggers affecting definite and indefinite NPs, respectively.

The evolution of DOM in Latin American Spanish expanded along the Animacy scale, since inanimate definite objects are specific and can receive DOM marking. What facilitated the marking of specific inanimate objects is the lexical nature of the verb (verbs that seem to be followed by ‘a’, such as seguir or perseguir “follow”), secondary predication (Considera a Juan inteligente “He considers Juan intelligent”), the preverbal or topicalized position of the objects, and clitic doubling, as mentioned earlier. Von Heusinger and Kaiser (2005) also found synchronic variation in the parameters that regulate DOM in Latin American Spanish: definiteness and specificity trigger DOM in Argentina and Uruguay, while, in other varieties, animacy and specificity are the main triggers.

Von Heusinger and Kaiser (2007) analyzed informal interviews with speakers living in Mexico City from the Macrocorpus de la norma lingüística culta de las principales ciudades del mundo hispano and comparable corpora from Argentinian Spanish, Peruvian Spanish and Uruguayan Spanish. Among those Spanish varieties, Mexican Spanish showed the most cases of DOM with inanimate objects. In order to explain the few cases of DOM with inanimate objects found in the data, Von Heusinger and Kaiser, following Pottier (1968) and Delille (1970), proposed that there is a verbal scale with four different verb classes: verbs that are more likely to take animate objects, verbs that are likely to take both animate and inanimate objects and verbs that tend to only take inanimate objects. According to Von Heusinger and Kaiser, the extension of DOM is less likely to happen with verbs that only take inanimate objects than with verbs that take both types of objects2. Moreover, Von Heusinger and Kaiser expected the use of DOM with clitic doubling as it generally triggers DOM. However, they found no examples of DOM with inanimate objects and clitic doubling. Similarly, Tippets (2010) analyzed the use of DOM in Argentinian Spanish, Peninsular Spanish and Mexican Spanish and found that, while DOM with inanimate objects was low overall, Mexican Spanish was the most innovative dialect: 15% of all objects produced were inanimate objects with DOM, compared to only 8% in Argentinian Spanish and 5% in Peninsular Spanish.

In order to further investigate the possible ongoing change of DOM in Mexican Spanish, Bautista Maldonado and Montrul (2019) tested 60 native speakers on their production and acceptability judgments of DOM. Bautista Maldonado and Montrul (2019) included an AJT in addition to an oral task. Their results showed that, while production of DOM with inanimate objects was very low in the oral task, participants’ acceptance of DOM with definite inanimate objects was high in the AJT. These results confirmed that there is a tendency toward DOM marking with specific inanimate objects. Because the tendency was higher in the AJT than in the oral task, the conclusion was that variability may manifest first in judgment data, which may be more representative of unconscious linguistic knowledge, than in production data, which are usually considered more representative of linguistic performance (especially if elicited via a task). However, as stated earlier, off-line grammaticality judgment tasks may also involve metalinguistic reflection. On-line tasks are believed to tap into implicit unconscious linguistic knowledge (Ellis 2005), and are, therefore, perhaps more suitable to detect subtle and incipient language change. This study combines both explicit and implicit methodologies to trace the diachronic extension of DOM to definite inanimate objects in Mexican Spanish speakers at the individual level.

1.2. Research Questions and Hypotheses

Is DOM extension3 to inanimate objects in monolingual speakers of Mexican Spanish reflected in (1) oral production; (2) off-line acceptability judgments; (3) on-line sentence processing while reading? What is the relationship between these measures?

- (1)

- Based on previous studies (Von Heusinger and Kaiser 2005; Bautista Maldonado and Montrul 2019), monolingually raised native speakers of Mexican Spanish were expected to mark categorically animate and specific objects and to show some degree of variation with inanimate objects. Moreover, participants were expected to show more extension of DOM to inanimate objects in the more implicit oral task (narration) than in the more explicit oral task (elicitation).

- (2)

- Participants were expected to show some preference for DOM extension to inanimate objects in the AJT (Bautista Maldonado and Montrul 2019). Therefore, participants were expected to judge sentences with DOM-marked inanimate objects as more acceptable than sentences that omitted DOM with animate objects.

- (3)

- If comprehension precedes production in language variation, as in L1 acquisition (Shipley et al. 1969) and L2 acquisition (Malovrh and Lee 2010), the use of DOM with inanimate objects should be evident in speakers’ sentence processing. Thus, participants were expected to show less grammatical sensitivity with sentences with DOM-marked inanimate objects than with sentences with unmarked animate objects.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Participants

Thirty-four native speakers of Mexican Spanish between the ages of 18 and 22 (average age 19.03) participated in the study (see Table 1). All participants were recruited from Universidad Autónoma del Carmen (UNACAR) in Ciudad del Carmen, Campeche, Mexico. Participants completed a background questionnaire and only participants who (1) were born in Mexico and had lived in Mexico during their childhood; (2) had no knowledge of an indigenous language; and (3) did not have any exposure to a second language before the age of 10 participated in the study. For all the participants, English was their second language. Participants indicated that they had never had exposure to an indigenous language. In Ciudad del Carmen, the indigenous population is very low (Azcorra and Dickinson 2020).

Table 1.

Background questionnaire information.

2.2. Tasks

2.2.1. Oral Tasks

Two oral tasks—an oral narrative task and an elicited production task—measured participants’ oral production of Spanish DOM. For the narrative task, participants narrated the children’s story ‘Little Red Riding Hood’ (from Montrul 2004). Participants were provided with 14 colorful pictures of the story via a PowerPoint slideshow and were asked to narrate the story using the preterite tense while providing as much detail as possible based on the pictures. The pictures contained many animate and inanimate referents as objects. Because participants are usually more concerned with what to say (meaning of the story) rather than how to say it (grammar) when completing narrative tasks, this task provides semi-spontaneous data, perhaps comparable to what one can elicit with sociolinguistic interviews.

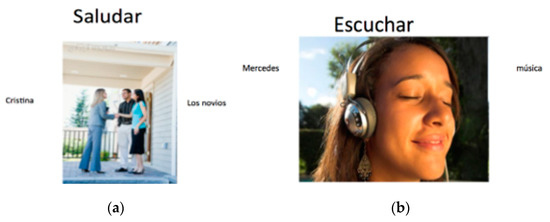

In the elicitation task, participants were presented with a picture with a verb and animate and inanimate NPs as subjects and objects on a computer screen and were asked to produce a sentence describing the picture using the verb and NPs given (see Figure 1). Participants were told to conjugate the verb in the preterite tense, so the presence or absence of DOM could be perceived.4 In total, participants were presented with 24 pictures: 12 with animate objects and 12 with inanimate objects. Another 12 pictures functioned as fillers. The fillers prompted participants to use different constructions (e.g., sentences with gustar-type verbs).

Figure 1.

Sample of items used in the oral elicitation task: (a) shows the picture used for the verb saludar ‘to greet’; (b) shows the picture used for the verb escuchar ‘to listen’.

If DOM is extending to inanimate objects, native speakers should produce DOM categorically with animate and specific objects, but show some degree of variation with inanimate objects. Moreover, more cases of DOM extension to inanimates are expected in a narrative task, which is less controlled (and more implicit) than an oral elicitation task.

2.2.2. Acceptability Judgment Task

The aim of this task was to test participants’ judgments of DOM. Sentences varied by animacy of the object (animate vs. inanimate) and object marking ([+DOM] vs. [−DOM]) as shown in Table 2. A Likert-scale ranging from 1 to 5 followed each sentence so that participants could express different degrees of acceptability (1 = totally unacceptable, 2 = unacceptable, 3 = undecided; 4 = acceptable, 5 = totally acceptable). In total, participants judged 132 sentences: 72 sentences tested DOM (36 grammatical, 36 ungrammatical) and 60 sentences were fillers (30 grammatical, 30 ungrammatical). Fillers contained sentences with different grammatical constructions (e.g., sentences with gustar-type verbs; sentences with different word order; sentences with use of subjunctive, etc.)

Table 2.

Sample sentences used in the AJT.

Speakers will accept sentences with animate objects and DOM (El niño acusó al señor de las gafas azules) as well as sentences with unmarked inanimate objects (La actriz dibujó el carro de sus sueños), and will reject sentences with animate objects and DOM omission (Diego acogió el estudiante de intercambio) categorically. If DOM is extending to definite inanimate objects (Bautista Maldonado and Montrul 2019), speakers will accept sentences with DOM-marked inanimate objects (El joven apreció al esfuerzo económico por parte de sus padres). More specifically, they are expected to rate sentences with DOM-marked inanimate objects (El joven apreció al esfuerzo económico por parte de sus padres) as more acceptable than sentences with unmarked animate and specific objects (Diego acogió el estudiante de intercambio).

2.2.3. Reading Comprehension Task with Eye-Tracking

This task measured participants’ sensitivity to DOM during reading comprehension. The basic assumption in reading tasks with eye-tracking is that participants’ eye movements are slower (fixed on the target longer) or produce more regressions (return to a specific region) when reading something unexpected. For example, when presented with sentences such as Juan vio el policía ‘Juan saw the policeman’ and Juan vio al policía ‘Juan saw DOM-the policeman’, participants are expected to take longer to read the first sentence or produce more regressions if they are aware that animate and specific objects must be marked with DOM.

Participants read sentences that varied by MARKING ([+DOM] vs. [−DOM]) and animacy of the object (animate vs. inanimate). Table 3 shows examples of the sentences used in this task.

Table 3.

Sample sentences used in the eye-tracking task5.

Notice in (8) that all objects (e.g., compañero, sofá) were singular and masculine objects with the case marker merged with the article (a + el = al). In this way, it is possible to compare ‘el’ versus ‘al’ because they are segments of equal length. All sentences were between 8 and 9 words in length and were preceded by a prepositional phrase because it is recommended to avoid having the critical, or even the spillover, region at the beginning of a sentence in eye-tracking with text tasks. Fixations tend to be longer at the beginning of a sentence and people often make corrective saccades (Heller 1982; Rayner 1979). All experimental sentences and fillers were followed by comprehension questions regarding the content of the sentences. The fillers used in this task were very similar to the filler sentences used in the AJT. The comprehension questions had nothing to do with agent/patient relationships so as not to direct the participants’ attention to the experimental manipulation, as in (8).

| (8) El actor liberó al compañero con su llave. | |

| ‘The actor released his partner with his key.’ | |

| ¿Qué usó el actor? | |

| ‘What did the actor use? | |

| A) Una llave (B) Unas tijeras | |

| ‘a key’ ‘a pair of scissors’ | |

If comprehension precedes production in language variation, as in L1 acquisition (Shipley et al. 1969) and in L2 acquisition (Malovrh and Lee 2010), the extension of DOM to definite inanimate objects should be detected in speakers’ sentence processing. Speakers are expected to show sensitivity to the omission of DOM in sentences with animate objects (*El actor liberó el compañero con su llave) but less sensitivity to the ungrammaticality of sentences with DOM-marked inanimate objects (*El joven movió al sofá a la calle para dormir).

2.3. Procedure

Participants arrived at the laboratory where they first read and signed a consent form. Then, they began the study by completing the reading task with eye-tracking, for which a portable eye-tracker (Eye Link SR Research, Ltd.; Ottawa, Canada) with remote desktop camera sampling at 500 Hz was used. Subjects were seated 50 cm from the monitor with their chin on a chinrest. Sentences were presented in 18-point Courier font, left-aligned on the display. Before the task began, a calibration procedure was carried out to accurately track participants’ eye-movements. During this initial process, participants were instructed to fix their gaze on a set of nine fixation points (black dots) displayed on the screen at known locations. While they were doing this, the positions of their eyes were recorded. If there were no errors when the calibration was performed, the computer then “validated” the information before subjects could begin the actual test.

Next, participants completed a practice session, which consisted of 8 trials, following the same procedure as the actual study in order for participants to become familiar with the eye-tracker and the response controller. The structure of each trial was as follows: first, a white screen with a black dot, the central fixation point, appeared in the left middle of the screen. Participants were told to look at this point immediately prior to pressing a button on a controller, which prompted a sentence to appear on the screen. After reading the sentence, participants pressed the button again to continue to a comprehension question related to the sentence they had previously seen. Participants used one of two buttons to respond ‘yes’ or ‘no’ to the comprehension questions after each trial. After the practice session, participants were instructed to move their head as little as possible during the experiment to ensure accurate tracking of their eye movements. Participants were also informed that they would be allowed to take three breaks during the experiment. If participants decided to take a break, and thus, moved their chin, recalibration was performed again. The eye-tracker machine recorded all movements of each participant’s right eye between the appearance of the white screen with the black point, indicating the beginning of a new trial, and the disappearance of the sentence, when a participant pressed the button to proceed to the comprehension question. In total, this task lasted between 30 and 45 min.

After the reading task with eye-tracking, participants completed the oral task in two parts: first the narrative task, then the elicitation task. Participants were seated in front of a laptop computer and their answers were recorded by the same laptop for both portions. For the narrative task, participants were asked to narrate the story in Spanish based on the pictures and to include as many details as possible. They advanced through the presentation at their own pace while their narration was continuously recorded. This task did not take longer than 10 min. The participants then completed the elicited production task, which took less than 10 min.

After the two oral tasks, participants completed the AJT using the same laptop they used for the oral tasks. Before starting the AJT, participants were told to read the sentences as carefully and as quickly as possible and to rely on their first instinct. The sentences were presented visually, and participants had as much time as they wanted to read and judge the sentences. They were instructed to rate the sentences on a scale of 1 to 5 by pressing a button on the computer, with 1 indicating completely unacceptable and 5 totally acceptable. A rating of 3 represented ‘undecided’. Participants completed the task within 30 to 40 min. Finally, participants completed the background questionnaire, which took about 20 to 30 min. In total, it took participants between 1.5 to 2 h to complete all of the tasks. Thus, all participants completed the most implicit tasks first (i.e., the reading task with eye-tracking) and the most explicit tasks last (i.e., the AJT).

3. Results

3.1. The Oral Production Tasks

Participants’ answers were audio-recorded and transcribed. In the narrative task and in the elicitation task, all direct objects were coded for animacy and for the presence/omission of DOM. In the elicitation task, if participants produced something unexpected, those sentences were coded as ‘other’ and were eliminated from the final statistical analyses. An example of the sentences that were coded as ‘other’ were sentences with the passive voice, as in El alumno fue castigado ‘The student was punished’ when the target sentence was La profesora castigó al alumno ‘The teacher punished the student’. In total, only 11 sentences were coded as ‘other’. An individual score was calculated for each participant’s use of DOM in each task. Numerical results were analyzed with a bivariate logistic regression with the framework of glm (generalized linear model) using R (version 1.1.453 for Mac OS X, Development Core Team 2014) with participant and item as random effects and MARKING ([+DOM] vs. [−DOM]) and animacy of the object (animate vs. inanimate) as fixed effects. Participants’ answers and the objects were coded numerically using dummy coding: (DOM: Marked = 1, Unmarked = 0; Animacy of the object: Animate Object = 1, Inanimate Object = 0). These results were then aligned in vertical columns to submit to logistic regression analyses.

3.1.1. Oral Narrative Task

Since the aim of this task was to analyze Mexican native speakers’ production or omission of DOM, all sentences with direct objects were considered for the analysis. In total, participants produced 196 animate objects and 202 inanimate objects (see Table 4). Although some extension of DOM to inanimate objects was expected in the narrative task, the results did not support this prediction. The logistic regression revealed a significant effect of DOM-MARKEDESS, as animate objects were marked with DOM significantly more than inanimate objects (t = (33) = 59.85, p = 0.0001).

Table 4.

Use or omission of DOM with animate and inanimate objects.

As Table 4 shows, on two occasions, two participants omitted DOM with animate and specific objects, as in (9a) and (9b). On one occasion, one participant used DOM with an inanimate object, as in (9c):

| 9 | |||||||

| (a) | Participant 122: | El | lobo | atacó | Caperucita. | ||

| the | wolf | attacked | Little red Riding Hood | ||||

| ‘The wolf attacked Little red Riding Hood.’ | |||||||

| (b) | Participant 130 | Un día | el lobo | al | querer | comerse | Caperucita |

| one day | the wolf | prep | want | eat | Little red Riding Hood | ||

| ‘One day the wolf when wanting to eat Little red Riding Hood.’ | |||||||

| (c) | Participant 110: | El | leñador | metió a | las piedras en el | estomago del lobo | |

| the | woodcutter | put | DOM the rocks | in the stomach of the wolf | |||

| ‘The woodcutter put the rocks in the wolf’s stomach.’ | |||||||

In sum, participants almost categorically produced DOM with animate and specific objects and omitted DOM with inanimate objects. Therefore, contrary to what was expected, native speakers of Mexican Spanish did not show variable extension of DOM to inanimate objects.

3.1.2. Oral Elicitation Task

In the elicitation task, the Mexican native speakers produced a total of 391 animate objects (17 sentences were coded as ‘other’) and a total of 387 inanimate objects (21 sentences were coded as ‘other’) (see Table 5). Some DOM extension to inanimate objects was expected but to a lesser extent than in the narrative task. However, the extension of DOM to inanimate objects was not prominent in this task either, with only seven such examples in total. Logistic regressions revealed a significant effect of DOM-MARKING, as animate objects were marked with DOM significantly more than inanimate objects (t = (33) = 27.16, p = 0.0001).

Table 5.

Use or omission of DOM with animate and inanimate objects.

The speakers of Mexican Spanish also omitted DOM with animate and specific objects on nine occasions in this task. However, more than half of these omissions happened with the same verb, abrazar ‘to hug’. As this verb is more likely to occur with animate objects than inanimate objects (Corpus del Español; Davies 2002), the omission of DOM with this verb was not expected in sentences such as (10a). Thus, the omission may be related to the object bebé ‘baby’. Previous psycholinguistic studies on the semantics of animacy suggest that animacy is a binary property. Thus, an object is either animate or inanimate and never more or less so. However, linguists see animacy as a graded property. Thus, participants may treat certain objects, such as bebé ‘baby’, as less animate than other objects. The other cases of DOM omission occurred with the verb perseguir ‘to follow’, as in (10b). Because this verb is a movement verb and movement verbs tend to favor ‘a’, the omission of DOM was not expected.

| (10) | |

| (a) | Participants 100, 103, 105, 110, 122: La mamá abrazó el bebé. |

| the mother hugged the baby | |

| ‘The mother hugged the baby.’ | |

| (b) | Participants 103, 111, 128, 130: El niño persiguió el otro niño. |

| the boy followed the other boy | |

| ‘The boy followed the other boy.’ | |

However, participants may have omitted DOM with this verb because the picture representing the verb may have been confusing. As Figure 2 shows, the subject and the object were both niño ‘boy’, which may have confused the participants.

Figure 2.

Items used in the oral elicitation task with the verb perseguir ‘to follow’.

As for the sentences with inanimate objects, the extension of DOM to inanimate objects happened primarily with the verb visitar ‘to visit’. The extension of DOM in sentences such as (11a) and (11b) may have occurred because the object was the proper name of a city, in this case. DOM marking with city names is not prescriptively required accordingly to Spanish language academies, but in some varieties, speakers use DOM (Laca 2006).

| 11 | ||||||

| (a) | Participant 103: | Raquel visitó | a | la ciudad | de | Chicago. |

| Raquel visited | DOM | the city | of | Chicago | ||

| ‘Raquel visited the city of Chicago’ | ||||||

| (b) | Participants 120, 124, 125: | Raquel visitó | a | Chicago. | ||

| Raquel visited | DOM | Chicago | ||||

| Raquel visited Chicago.’ | ||||||

Participants also extended DOM to inanimate objects with the verbs tocar ‘to touch’, as in (12a), and with llevar ‘to bring’, as in (12b).

| 12 | |||||

| (a) | Participant 100, 126: | Julián tocó | a | la planta | |

| Julian touched | DOM | the plant | |||

| ‘Julian touched the plant.’ | |||||

| (b) | Participant 128: | El viejo | llevó | al | paraguas. |

| the old man | brought | DOM | the umbrella | ||

| The old man brought the umbrella.’ | |||||

It is difficult to understand why only some speakers extended DOM to inanimate objects with only some verbs. Moreover, the number of cases in which speakers produced this innovative use of DOM was minimal and could be considered speech errors. Therefore, the results from this sample of speakers suggest that Mexican Spanish is not undergoing some type of DOM variation, as most participants omitted DOM with inanimate objects in most cases.

3.2. Acceptability Judgment Task

Results were analyzed using the clmm (cumulative link mixed model) function in the “ordinal” package (Christensen RHB 2015) using R (version 1.1.453 for Mac OS X, Development Core Team 2014). Clmms were performed on the ordinary-scaled data to model both participant- and item-variability (Agresti 2002). The raw scores were entered as primary outcome measures (i.e., item ratings per participant and condition) into the statistical analyses. While the raw scores of the acceptability ratings were the dependent variable, MARKING ([+DOM] vs. [−DOM]) and animacy of the object (animate vs. inanimate) were both fixed effects. Subject and item were included as random effects not standardized because clmms take inter-participant variation into consideration.

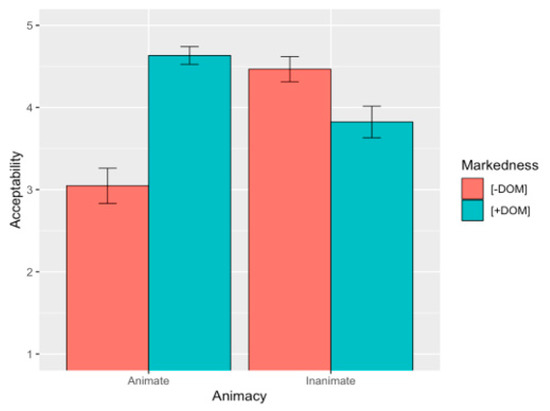

The cumulative mixed model effect revealed a significant effect of MARKING (β = 2.90, SE = 0.25, t = 11.39, p < 0.0001), a significant effect of ANIMACY (β = 2.49, SE = 0.23, t = 10.50, p < 0.0001) and a significant MARKING*ANIMACY interaction (β = −4.23, SE = 0.35, t = −11.88, p < 0.0001). Pairwise comparisons with Tukey’s multiple comparison test revealed a significant difference when comparing sentences with animate objects and DOM to sentences with animate objects and DOM omission (β = −2.90, SE = 0.25, t = −11.39, p < 0.0001). As Figure 3 shows, participants rated the sentences with DOM significantly higher than the sentences with DOM omission. As for sentences with DOM omission, most participants seemed to be indecisive about their acceptability, and there was notable variation among participants’ answers. This shows some difficulty deciding on the acceptability of unmarked animate objects. While this acceptability of unmarked animate objects was not expected, this DOM retraction has been found in other studies, but usually in situations of language contact: Spanish in contact with English (Montrul 2004; Montrul and Sánchez-Walker 2013; Cuza et al. 2016; Alfaraz 2011), when in contact with indigenous languages, for example with Quechua (Sánchez 2003) and with Ashaninka (Mayer and Sánchez 2018).While Tukey’s test also revealed a significant contrast when comparing sentences with inanimate objects and DOM to sentences with inanimate objects and DOM omission (β = 1.33, SE = 0.23, t = 5.66, p < 0. 0001). As Figure 3 shows, participants rated the sentences with DOM omission significantly higher than the sentences with DOM. However, there was variation on the acceptance of DOM with inanimate objects and some participants accepted DOM in this context.

Figure 3.

Mean acceptability scores and errors bars (CI 95%).

Moreover, when comparing ungrammatical sentences with unmarked animate objects and sentences with marked inanimate objects, there was a significant effect (β = −2.49, SE = 0.23, t = −10.49, p < 0.0001), which shows more of a tendency to mark DOM with inanimate objects than to omit DOM with animate objects, as predicted. However, there was not a significant effect when comparing sentences with marked animate objects and sentences with unmarked inanimate objects (β = 0.40, SE = 0.26, t = 1.5, p = 0.43), as participants accepted both types of sentences.

3.3. Reading Comprehension Task with Eye-Tracking

Data for the reading task with eye-tracking were analyzed with the lmer (linear mixed effect regression) function in the lme4 package (Bates et al. 2014) using R (version 1.1.453 for Mac OS X, Development Core Team 2014) for every eye movement measurement. For all analyses, reading times were the dependent variable, while marking ([+DOM] vs. [−DOM]) and animacy of the object (animate vs. inanimate) were fixed effects. Subject and item were both included as random effects. When significant interactions were found, a Tukey’s multiple comparison test was performed with lsmeans package to conduct multiple pairwise comparisons of the fixed variables and their interactions. All sentences used in the reading task with eye-tracking were divided into eight different regions (R) of interest, as shown in (13). While the Critical Region (CR) was Region 3 (the region in which DOM is either used or omitted), processing effects could occur after the Critical Region (spillover effect) (Arechabaleta Regulez 2020). Therefore, not only the CR, but also Region 4 (R4), Region 5 (R5) and Region 6 (R6) were analyzed.

| (13) | ‘Kevin said hi to the father in the park of Chicago’ | |||||||

| Kevin | salu | dó al/el | padre | en | el | parque | de | |

| R 1 | R2 | CR | R4 | R5 | R6 | R7 | R8 | |

Notice that the case marking (DOM) appeared together with the ending of the word preceding it (a + el = al). This was done in order to avoid the problem of the DOM marker not having many direct fixations because it can be processed parafoveally while fixating on the previous word.

Both early and late eye-tracking measures of comprehension were analyzed for the four different regions. The early measures analyses included first pass reading times and sum of skipped targets. First pass reading times were run to measure the time participants spent in each region the first time they read the sentence. The sum of skipped targets was analyzed for the Critical Region because it is important to analyze how many times participants skipped DOM marking. Later stage measures included second pass reading times, total reading times, number of regressions out and number of regression in. Second pass reading times were analyzed to measure the time participants spend in each region when re-reading the sentence. Total reading times were run to measure the total time participants spent in each region of the sentence. Finally, number of regressions out and number of regressions in were calculated for each sentence. While number of regressions out refers to the number of times a region was exited (with an eye regression) to a previous region, number of regressions in refers to the number of times a region was entered (with an eye regression) from a later region. Table 6 defines each of the reading measures used in this task.

Table 6.

Explanation of the reading times included in the analysis.

As an initial matter, items with inaccurate responses to the post stimulus comprehension questions were excluded from the descriptive and statistical analyses to ensure that the analyses included only sentences that participants understood. Response accuracy was high (95.3% (range 92–100)). Additionally, all fixations shorter than 80ms and longer than 1200ms were excluded (Rayner 1979). This excluded 7.3% of the total data.

Five reading times (total reading times, first pass reading times, second pass reading times, regressions in and regressions out) were statistically analyzed for each region. The sum of skipped targets was analyzed separately and only in the Critical Region. Results for each type of sentence are discussed in the following subsections. Each discussion begins with a table displaying the mean reaction times in milliseconds as well as the standard errors for each of the five reading times and in each of the four regions. Finally, only significant effects are discussed, and all significant interactions were analyzed with Tukey’s multiple comparison test. Table 7 shows the mean reaction times in milliseconds for each of the five reading times and in each of the four regions analyzed for SVO sentences.

Table 7.

Mean reaction times and standard deviations (in parentheses) for sentences with animate and inanimate objects.

Total reading times (TT): In the Critical Region (region 3), there was a significant MARKING effect (β = −120.55, SE = 25.90, t = −4.65, p = 0.0001) and a significant MARKING and ANIMACY interaction (β = 159.78, SE = 36.26, t = 4.46, p = 0.00001). Similarly, in Region 4, there was also a significant MARKING effect (β = −79.24, SE = 20.64, t = −3.89, p = 0.00013) and a significant MARKING and ANIMACY interaction (β = 73.04, SE = 28.72, t = 2.54, p = 0.011). The interactions were followed up with Tukey’s multiple comparison tests. Results showed that there was a significant contrast when comparing sentences with marked animate objects to sentences with unmarked animate objects in the Critical Region (β = 119.20, SE = 25.92, t = 4.59, p = 0.0001) and in Region 4 (β = 80.32, SE = 20.68, t = 3.99, p = 0.0006). In the Critical Region and in Region 4, participants spent significantly more time with sentences with DOM omission. This suggests that participants were sensitive to the omission of DOM with animate objects (see Table 8 and Table 9).

Table 8.

Results obtained in the MARKING and ANIMACY interaction in the Critical Region.

Table 9.

Results obtained in the MARKING and ANIMACY interaction in Region 4.

However, there were no significant effects between sentences with marked inanimate objects and sentences with unmarked inanimate objects in any of the regions. Thus, participants’ reading times were not affected by DOM-marked inanimate objects. While participants took longer to read these regions with sentences with DOM than with sentences with DOM omission, the difference was not significant. There was not a significant MARKING effect (β = 73.04, SE = 28.72, t = 2.54, p = 0.11) or a significant MARKING and ANIMACY interaction (β = 41.99, SE = 30.55, t = 1.37, p = 0.17) in Region 5, nor in Region 6 (β = −5.46, SE = 21.34, t = 15.73, p = 0.79), (β = 14.83, SE = 29.79, t = 0.49, p = 0.61), respectively.

Second pass reading times: In the Critical Region, there was a significant MARKING effect (β = −108.47, SE = 25.60, t = 12.58, p < 0.0001) and a significant MARKING and ANIMACY interaction (β = 147.81 SE = 35.85, t = 4.12, p < 0.0001). Similarly, in Region 4, there was also a significant MARKING effect (β = −61.38, SE = 18.93, t = −3.41, p < 0.001) and a significant MARKING and ANIMACY interaction (β = 56.25, SE = 27.17, t = 2.071, p = 0.03). Tukey’s multiple comparison tests revealed a significant effect when comparing sentences with DOM-marked animate objects to ungrammatical sentences with animate objects and DOM omission. In the Critical Region (β = 110.28, SE = 25.63, t = 4.30, p = 0.0001) and in Region 4 (β = 65.57, SE = 18.96, t = 3.45, p = 0.0032), participants showed sensitivity to DOM omission with animate objects. As Table 10 and Table 11 show, participants produced significantly longer reading times when reading sentences with unmarked animate objects than sentences with DOM-marked objects. However, with inanimate objects, there was not a significant effect when comparing sentences with marked and unmarked inanimate objects. There was not a significant MARKING effect (β = 81.09, SE = 28.72, t = 1.54, p = 0.21) or a significant MARKING and ANIMACY interaction (β = 34.99, SE = 20.57, t = 1.33, p = 0.37) in Region 5, nor in Region 6 (β = −4.64, SE = 20.33, t = 12.73, p = 0.52), (β = 12.66, SE = 22.44, t = 0.69, p = 0.71), respectively.

Table 10.

Results obtained in the MARKING and ANIMACY interaction in Region 4.

Table 11.

Results obtained in the MARKING * ANIMACY interaction in Region 4.

Number of regressions in: In the Critical Region, there was a significant effect for MARKING (β = −0.08, SE = 0.03, t = −2.06, p = 0.03) and a significant MARKING and ANIMACY interaction (β = 0.11, SE = 0.054, t = 2.06, p = 0.03). However, Tukey’s multiple comparison test did not reveal any significant effects. As Table 12 shows, participants produced more regressions with sentences with unmarked than with marked and objects; however, results also show that inanimate objects had slightly more regressions than animate objects. There was not a significant effect for MARKING in the other regions: Region 4 (β = −0.06, SE = 0.03, t = −1.82, p = 0.06), Region 5 (β = −0.05, SE = 0.03, t = 1.25, p = 0.20) and Region 6 (β = 0.25, SE = 0.03, t = 0.71, p = 0.47). The MARKING * ANIMACY interaction was also non-significant for the rest of the regions: Region 4 (β = 0.05, SE = 0.04, t = 1.12, p = 0.25), Region 5 (β = −0.09, SE = 0.05, t = −1.76, p = 0.07) and Region 6 (β = 0.05, SE = 0.04, t = −0.18, p = 0.85).

Table 12.

Results obtained in the MARKING and ANIMACY interaction in the Critical Region.

Number of regressions out: Regressions Out did not show any significant MARKING effects in any of the regions: Critical Region (β = −9.42, SE = 7.20, t = −1.30, p = 0.17), Region 4 (β = −14.24, SE = 7.41, t = −1.85, p = 0.06), Region 5 (β = −3.97, SE = 8.007, t = −0.49, p = 0.61) and Region 6 (β = −0.85, SE = 8.84, t = −0.09, p = 0.92). The MARKING and ANIMACY interaction was also non-significant in: the Critical Region (β = 0.08, SE = 0.04, t = −1.79, p = 0.07), Region 4 (β = 6.88, SE = 4.15, t = 1.65, p = 0.09), Region 5 (β = 0.01, SE = 0.04, t = 0.29, p = 0.76) and Region 6 (β = −0.03, SE = 0.04, t = −0.62, p = 0.53).

To summarize: Reading times suggest that participants were sensitive to the omission of DOM with animate objects, recognizing its ungrammaticality. When reading ungrammatical sentences without DOM, participants produced longer reading times in the Critical Region (Region 3) and in the region immediately following the Critical Region (Region 4). However, this sensitivity was only evident in later processing measurements: total reading times and second pass reading times. As for sentences with inanimate objects, the participants showed no sensitivity to DOM-marked inanimate objects, suggesting that these sentences are not “surprising” or “ungrammatical” to them. Participants’ reading patterns were similar for both sentences with DOM and sentences with DOM omission. This suggests that for some speakers, DOM-marked inanimate specific direct objects are grammatical.

4. Discussion

Previous research has suggested that speakers of Mexican Spanish extend DOM to inanimate objects (Von Heusinger and Kaiser 2005; Tippets 2010). Assuming López’s (2012) syntactic account where animate direct objects in Spanish move to a projection P2 above the VP, as in (14), and inanimate objects stay in the VP in P1, the change we are seeing in some varieties of Spanish is the movement of specific inanimate objects to P2 as well (and marked with DOM). Some non-specific, indefinite direct objects are still projected in the P1 position, as in (14):

To corroborate the strength of this finding, we analyzed the production, acceptability judgments and on-line comprehension of Spanish DOM in speakers of Mexican Spanish. We provided novel data using psycholinguistic methodologies to show how this ongoing extension might start at the individual level. However, the literature on DOM variation is still limited, and most of these studies have only analyzed speakers’ production from a sociolinguistic perspective. While informative, these studies often generate few tokens, making it difficult to confirm whether individual speakers are actually extending DOM to new contexts as well as to understand how these changes occur. Therefore, we applied psycholinguistic measures to identify DOM variation in speakers of Mexican Spanish in order to understand the cognitive processes that may be guiding linguistic variation. In this study, participants completed two oral tasks—an AJT and a reading task with eye-tracking—to measure potential variability of DOM-marking in oral production, grammatical acceptability and implicit sensitivity to the extension and omission of DOM with animate and inanimate objects. The AJT and the reading task both test receptive knowledge, but AJTs are generally off-line tasks, as we cannot analyze the decision-making process in action, but rather, only see the result of a decision; however, reading tasks with eye-tracking are on-line tasks as they measure speakers’ mental representations in real time. Therefore, on-line tasks, but not off-line tasks, measure speakers’ unconscious and/or automatic response (e.g., reacting times) to a linguistic stimulus (e.g., a word) in real time.

If the extension of DOM to inanimate objects is already frequent in production, it was hypothesized that participants would produce DOM with inanimate objects and that this extension of DOM would be more prominent in the narrative task, as it more closely resembles natural speech. However, results did not support these hypotheses. DOM was produced with an inanimate object on only one occasion in the narrative task. In the elicitation task, it was produced in seven cases. Because most of these productions happened with the same verb, however, it appears that DOM with inanimate objects was not productive in these Mexican Spanish speakers, or at least in speakers from Ciudad del Carmen, Campeche (cf. Bautista Maldonado and Montrul 2019). Although participants were not expected to omit DOM with animate objects, some did omit DOM with animate objects twice in the narrative task and seven times in the elicitation task. However, as in the case of DOM extension, DOM omission was minimal.

Second, participants completed an AJT for which they read sentences that varied by animacy of the object and DOM-marking. Participants were expected to categorically reject sentences with unmarked animate objects and accept sentences with DOM-marked animate objects and unmarked inanimate objects. As for sentences with DOM-marked inanimate objects, participants were expected to show variability. The results, however, did not consistently support these expectations. While participants accepted the use of DOM with animate objects, they did not reject the omission of DOM with animate objects as there was a lot of variability in participants’ answers and results showed some acceptability of unmarked animate objects. Interestingly, previous research on DOM has demonstrated this same pattern, also known as retraction of DOM. For example, a study conducted by Alfaraz (2011) on the use of DOM in Cuban Spanish found that while speakers of Cuban Spanish still use DOM before highly definite animate objects, they do not use it in other contexts. However, these speakers were living in the U.S. at the time of testing. Thus, the retraction of DOM observed in this particular study may have been the result of language contact with English, a non−DOM language, rather than an internal change in the language. However, as we also see some DOM retraction in this study, DOM may be showing more variability than expected in monolingual communities. While this study was conducted in Campeche, an area of contact with Mayan, Ciudad del Carmen has a very small indigenous community and all the participants said that they have never been exposed to an indigenous language. Therefore, restriction of DOM appears to also happen in situations where we do not find language contact. DOM-marked inanimate objects were generally rated unacceptable, but there was also substantial variability in individual responses. Still, acceptance of DOM-marked inanimate objects was higher than that of unmarked animate objects, consistent with our hypothesis.

Finally, participants’ processing was analyzed in the reading task with eye-tracking. Participants read sentences with marked and unmarked animate and inanimate objects. As with the AJT, it was hypothesized that participants would show some acceptance of the extension of DOM to inanimate objects and we found that this hypothesis was largely confirmed, as participants did not seem to reject the use of DOM with inanimate objects and thus, did not produce significantly longer reading times with DOM-marked inanimate objects. As expected, participants were sensitive to the omission of DOM with animate objects as they did produce longer reading times with these sentences than with sentences with marked animate objects. However, it is important to notice that while participants seemed to reject unmarked animate objects in the reading task with eye-tracking, they accepted some of these sentences in the AJT.

Thus, these results emphasize the importance of using experimental methods when analyzing language variation. Results in this study show that incipient language innovations (i.e., variation or language change) are not always observable in spontaneous oral production. Instead, they sometimes manifest only when examining participants’ competence through comprehension and judgment methodologies. This reinforces the notion that it is important to look at languages from new perspectives. In particular, it highlights the benefit of examining language variation from a psycholinguistic perspective. The results showed no overextension of DOM to inanimate objects in the oral production tasks, but acceptance of DOM with inanimate objects in the AJT and no on-line sensitivity to marked inanimate objects in the reading task with eye-tracking. Bautista Maldonado and Montrul 2019, who also tested Mexican speakers from the same region as those tested in our study, found no extension of DOM to inanimate objects in production, but high acceptance of innovative uses of DOM with inanimate objects in the acceptability judgment task. Thus, we can conclude that it takes longer for these new innovations to manifest themselves in speakers’ production and more importantly, that DOM is indeed extending to inanimate objects in Mexican Spanish, but it is in its early stage of language variation. Moreover, results also showed this production–comprehension asymmetry with unmarked animate objects. This time, while participants did not show sensitivity to animate objects with DOM in on-line processing, they rejected some unmarked animate objects in the AJT, but unmarked DOM was not part of speakers’ production. This production–comprehension asymmetry has also been found in previous studies on language variation (Czypionka and Kupisch 2019; Lundquist et al. 2016; Herold 1990). For example, Lundquist et al. (2016) conducted a study on the variation of Norwegian gender where feminine gender agreement is gradually disappearing from some Northern Norwegian dialects. In their study, the researchers used an oral elicitation task to test participants’ gender production and a visual world paradigm study to test participants’ predictive use of grammatical gender. Similar to the results obtained in the present study, Lundquist et al. observed a production–comprehension asymmetry. While speakers retained the use of feminine gender in spoken production, the participants were insensitive to the feminine form during processing, suggesting innovation at the level of comprehension. More recently, Czypionka and Kupisch (2019) found that native speakers of German are undergoing a change in the semantics of definite articles in generic and specific contexts, and this change was also detected in an on-line comprehension task but not in an off-line task. Thus, the remaining question is, how can language variation be more prominent in speakers’ processing than in their production?

Lundquist et al. proposed that comprehension is affected before production in the context of language variation. According to this hypothesis, in situations where language variation is found, such as the extension of DOM in Mexican Spanish or the disappearance of the feminine gender form from some Norwegian dialects, speakers ‘adjust’ their comprehension by paying less attention to linguistic features that are used inconsistently in their environment, before they change their production. Therefore, with respect to language variation, processing is affected early, whereas production, at least oral production, is affected more gradually and slowly. Interestingly, this production–comprehension asymmetry has also been found in studies analyzing phonological variation. In near-merge situations, where a phonemic distinction is about to disappear, speakers continue to produce the distinction even though they are no longer able to hear it (Herold 1990). Studies of language variation and change in Romance and other languages have mostly relied on data from spoken and written corpora. We showed that experimental methods can detect incipient change at the individual level in a monolingual variety of Spanish, demonstrating how combining different experimental methods affords us the possibility to investigate how variation manifests itself in different language skills and modalities.

It is also interesting to note that when analyzing marked inanimate objects, the results suggest that language variation, or at least DOM variation in our study, may begin in speakers’ on-line comprehension before manifesting itself in speakers’ judgements, and finally, in their oral production. However, for unmarked animate objects, we see that DOM retraction is not reflected in the speakers’ processing and our results only showed some acceptance in speakers’ judgements. If unmarked animate objects are an internal change in the language, the change is likely in its early stages and that is why it is less apparent in both the reading task with eye-tracking and the AJT. However, future studies should reexamine this phenomenon to better understand how DOM is developing.

Finally, while we believe that our results are relevant for the understanding of DOM variation, there are some important limitations. First, oral comprehension is only compared to written comprehension and not to aural comprehension. Future studies should also focus on participants’ aural comprehension. Second, only young, educated speakers were tested. In order to better understand DOM variation in Mexican Spanish, it is important to test more diverse participants: different ages, different socioeconomic status, with and without education, etc. Finally, all the participants were born and raised in a small town in Campeche, Mexico. Thus, in order to be able to understand what is possibly happening in Mexican Spanish, speakers from different regions need to also be analyzed.

Author Contributions

B.A.R. and S.M.; methodology, B.A.R. and S.M. formal analysis, B.A.R.; data collection, B.A.R.; writing—original draft preparation, B.A.R.; writing—review and editing, S.M.; supervision, S.M. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was partially funded by the Love Fellowship (UIUC Center for Latin American and Caribbean Studies).

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted according to the guidelines of the Declaration of Helsinki, and approved by the Institutional Review Board of The University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign (IRB# 16637 on 30 March 2017).

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

The data supporting reported results are not available for public but can be obtained upon request from the principal investigators of the project.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Note

| 1 | When both the external and the internal argument are inanimate, there can be a potential ambiguity between the subject and the object of the sentence and therefore, DOM is usually used as in: “El ácido corroe al metal”. |

| 2 | In a previous study (Montrul 2014), we tested verbs that tend to go with animate objects, verbs that tend to go with inanimate objects, and verbs that tend to go with both objects, following Von Heusinger and Kaiser (2007) and no differences in DOM omission were found by type of verb. Therefore, we did not consider different verbs as a variable in the present study. |

| 3 | Extension refers to the use of DOM with inanimate objects in sentences where the subject is animate. |

| 4 | For both oral tasks, participants were instructed to use the preterite tense. For the AJT and the reading task, DOM always appeared with a verb in the preterite tense. The reason for this is that when the DOM preposition ‘a’ appears after a verb of the first conjugation in the present indicative, for example Ella visita a la abuelita ‘She visits the grandmother’, the sequence of two [a] sounds (one from the verbal ending and one for the marker) is reduced to one, possibly somewhat lengthened ([a:]), so that the preposition is practically inaudible in speech. In the preterite tense, as in Ella visitó a la abuelita ‘She visited the grandmother’, the vowel is diphthongized with the vowel of the verb ending (/oa/or/ua/). Thus, it is easier to analyze the use of DOM. |

| 5 | As noted by an anonymous reviewer, some sentences were longer (had more syllables) than others. However, all sentences were between 8 and 9 words in length and were preceded by a prepositional phrase because it is recommended to avoid having the critical, or even the spillover region, at the beginning of a sentence in eyetracking with text tasks. |

| 6 | Estimated marginals means (emmean) uses regression equations to calculate actual means. |

References

- Agresti, Alan. 2002. Categorical Data Analysis, 2nd ed. Hoboken: Wiley. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aissen, Judith. 2003. Differential object marking: Iconicity vs. economy. Natural Language and Linguistic Theory 21: 435–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aitchison, Jean. 2001. Language Change: Progress or Decay? 3rd ed. Cambridge: University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Alfaraz, Gabriela. 2011. Accusative object marking: A change in progress in Cuban Spanish? Spanish in Context 8: 213–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Archibald, John. 2000. Models of L2 phonological acquisition. In Social and Cognitive Factors in Second Language Acquisition: Selected Proceedings of the 1999 Second Language Research Forum. Edited by Bonnie Swierzbin, Frank Morris, Michael E. Anderson, Carol A. Klee and Elaine Tarone. Somerville: Cascadilla Press, pp. 125–57. [Google Scholar]

- Arechabaleta Regulez, Begoña. 2020. The Processing of Differential Object Marking by Heritage Speakers of Spanish. In The Acquisition of Differential Object Marking. Trends in Language Acquisition Research. Edited by Alexandru Mardale and Silvina Montrul. Amsterdam: John Benjamins Publishing Company, vol. 26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Azcorra, Hugo, and Federico Dickinson. 2020. Introduction. In Culture, Environment and Health in the Yucatán Peninsula: A Human Ecology Perspective. Edited by Hugo Azcorra and Federico Dickinson. Cham: Springer, pp. 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Banks, Marva A. 2004. Semantic Changes in Present-Day English (PDE) Thesis. Senior Thesis, Department of English, Langston University, Langston, OK, USA. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Bates, Douglas, Martin Maechler, Ben Bolker, and Steve Walker. 2014. lme4: Linear Mixed-Effects Models Using Eigen and S4. R Package Version 1.1-7. Available online: http://CRAN.R-project.org/package=lme4 (accessed on 15 August 2021).

- Bauer, Laurie. 1994. Watching English Change. An Introduction to the Study of Linguistic Change in Standard Englishes in the Twentieth Century. London: Longman. [Google Scholar]

- Baugh, Albert C., and Thomas Cable. 1978. A History of the English Language. London: Prentice Hall. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bautista Maldonado, Salvador, and Silvina Montrul. 2019. An experimental investigation of differential object marking in Mexican Spanish. Spanish in Context 16: 22–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bossong, Georg. 1991. Differential object marking in romance and beyond. In New Analyses in Romance Lingusitics. Edited by Douglas A. Kibbee and Dieter Wanner. Amsterdam and Philadelphia: John Benjamins, pp. 143–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chambers, Jack K. 2002. Dialectology. In International Encyclopedia of the Social and Behavioral Sciences. Edited by N. J. Smelser and P. B. Baltes. Amsterdam: Elsevier Science. [Google Scholar]

- Chomsky, Noam. 1965. Aspects of the Theory of Syntax. Cambridge: MIT Press. [Google Scholar]

- Christensen, Rune Haubo B. 2015. Ordinal: Regression Models for Ordinal Data. R Package Version 2015.6-28. Available online: https://CRAN.R-project.org/package=ordinal (accessed on 15 August 2021).

- Clahsen, Harald, and Claudia Felser. 2006. Grammatical processing in language learners. Applied Psycholinguistics 27: 3–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Clifton, Charles, Antje S. Meyer, Lee H. Wurm, and Rebecca Treiman. 2013. Language comprehension and production. In Comprehensive Handbook of Psychology, 2nd ed. Experimental Psychology. Edited by Alice F. Healy and Robert W. Proctor. New York: Wiley, vol. 4, pp. 523–47. [Google Scholar]

- Company, Concepción. 2002. El avance diacrónico de la marcación prepositiva en objetos directos inanimados. In Presente y futuro de la lingüística en España. Edited by Alberto Bernabé, José Antonio Berenguer, Margarita Cantarero and José Carlos de Torres Torres. Madrid: SEL, vol. II, pp. 146–54. [Google Scholar]

- Cuza, Alejandro, Lauren Miller, and Mariluz Ortíz. 2016. On the production of differential object marking and wh-question formation in native and nonnative Spanish. Language Acquisition Beyond Parameters: Studies in Honour of Juana M. Liceras 51: 187. [Google Scholar]

- Cuza, Alejandro, Lauren Miller, Rocio Pérez Tattam, and Mariluz Ortiz. 2018. Structure complexity effects and vulnerable domains in child heritage Spanish: The case of Spanish personal a. International Journal of Bilingual Education and Bilingualism 23: 1333–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Czypionka, Anna, and Tanja Kupisch. 2019. (The) polar bears are pink. How (the) Germans interpret (the) definite articles in plural subject DPs. The Journal of Comparative Germanic Linguistics 22: 247–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davies, Mark. 2002. Un corpus anotado de 100.000.000 palabras del español histórico y moderno. In Revistas - Procesamiento del Lenguaje Natural. Valladolid: Sociedad Española para el Procesamiento del Lenguaje Natural, pp. 21–27. [Google Scholar]

- DeKeyser, Robert. 2003. Implicit and Explicit Learning. In The Handbook of Second Language Acquisition. Edited by Catherine J. Doughty and Micahel H. Long. Oxford: Blackwell Publishers, pp. 312–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Delille, Karl Heinz. 1970. Die Geschichtliche Entwicklung des Präpositionalen Akkusativs im Portugiesischen. Bonn: Romanisches Seminar. [Google Scholar]

- Eckert, Penelope. 2005. Variation, convention, and social meaning. Paper presented at the Annual Meeting of the Linguistic Society of America, Oakland, CA, USA, January 7. [Google Scholar]

- Ellis, Rod. 2005. Instructed language learning and task-based teaching. In Handbook of Research in Second Language Teaching and Learning. Edited by Eli Hinkel. Mahwah: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates. [Google Scholar]

- Ferreira, Fernanda, and Benjamin Swets. 2005. The production and comprehension of resumptive pronouns in relative clause "island" contexts. In Twenty-First Century Psycholinguistics: Four Cornerstones. Edited by Anne Cutler. Mahway: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates, pp. 263–78. [Google Scholar]

- Fischer, Olga, Anette Rosenbach, and Dieter Stein, eds. 2000. Pathways of Change: Grammaticalization in English. Studies in Language Companion Series; Amsterdam: Benjamins, vol. 53. [Google Scholar]

- Heller, Dieter. 1982. Eye movements in reading. In Cognition and Eye Movements. Edited by Rudolf Groner and Paul Fraisse. Amsterdam: North Holland, pp. 139–54. [Google Scholar]

- Herold, Ruth. 1990. Mechanisms of Merger: The Implementation and Distribution of the Low Back Merger in Eastern Pennsylvania. Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Dissertation. [Google Scholar]

- Hulstijn, Jan H. 2005. Theoretical and empirical issues in the study of implicit and explicit second-language learning. Studies in Second Language Acquisition 27: 129–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Kim, Kitaek, William OGrady ’, and Bonnie D. Schwartz. 2018. Case in heritage Korean. Linguistic Approaches to Bilingualism 8: 252–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Labov, William. 1972. Language in the Inner City. Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press. [Google Scholar]

- Labov, William. 1994. Principles of Linguistic Change. Volume 1: Internal Factors. Oxford: Blackwell. [Google Scholar]

- Labov, William. 2001. Principles of Linguistic Change. Volume 2: Social Factors. Oxford: Blackwell. [Google Scholar]

- Laca, Brenda. 2006. El objeto directo. La marcación preposicional. In Sintaxis histórica de la lengua española. Primera parte: La frase verbal. Edited by Concepcion Company Company. México: Fondo de Cultura Económica/UNAM, pp. 423–78. [Google Scholar]

- Léglise, Isabelle, and Claudine Chamoreau, eds. 2013. The Interplay of Variation and Change in Contact Settings. Amsterdam: John Benjamins. [Google Scholar]

- López, Luis. 2012. Indefinite Objects: Scrambling, Choice Functions, and Differential Marking. Cambridge: MIT Press. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lundquist, Björn, Yulia Rodina, Iirina A Sekerina, and Marit Westergaar. 2016. Gender change in Norwegian dialects: Comprehension is affected before production. Linguistics Vanguard 2: 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Malovrh, Paul A., and James F Lee. 2010. Connections between processing, production and placement: Acquiring object pronouns in Spanish as a second language. In Research in Second Language Processing and Parsing. Edited by Bill VanPatten and Jill Jegerski. Philadelphia: John Benjamins, pp. 231–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mayer, Elisabeth, and Liana Sánchez. 2018. Typological differences in morphological patterns, gender features, and thematic structure in the L2 acquisition of Ashaninka Spanish. Languages 3: 21. [Google Scholar]

- McMahon, April. 1994. Understanding Language Change. Cambridge: University Press. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Montrul, Silvina. 2004. Subject and object expression in Spanish heritage speakers. A case of morpho-syntactic convergence. Bilingualism: Language and Cognition 7: 125–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Montrul, Silvina. 2014. Structural changes in Spanish in the United States: Differential object marking in Spanish heritage speakers across generations. Lingua 151B: 177–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Montrul, Silvina, and Melissa Bowles. 2009. Back to basics: Differential Object Marking under incomplete acquisition in Spanish heritage speakers. Bilingualism: Language and Cognition 12: 363–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Montrul, Silvina, and Noelia Sánchez-Walker. 2013. Differential Object Marking in Child and Adult Spanish Heritage Speakers. Language Acquisition 20: 109–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perez-Cortes, Silvia, Michael T Putnam, and Liliana Sánchez. 2019. Differential Access: Asymmetries in Accessing Features and Building Representation in Heritage Language Grammars. Languages 4: 81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Perpiñán, Silvia. 2015. L2 Grammar and L2 Processing in the Acquisition of Spanish Relative Clauses. Bilingualism: Language and Cognition 18: 577–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pottier, Bernard. 1968. L’emploi de la pre’position a devant l’objet en espagnol. Bulletin de la Société de Linguistique 1: 83–95. [Google Scholar]

- Rayner, Keith. 1979. Eye guidance in reading: Fixation locations within words. Perception 8: 21–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodríguez-Ordóñez, Itxaso. 2017. Reexamining differential object marking as a linguistic contact phenomenon in Gernika Basque. Journal of Language Contact 10: 318–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Sánchez, Liliana. 2003. Quechua-Spanish Bilingualism: Interference and Convergence in Functional Categories. Amsterdam: Johns Benjamins. [Google Scholar]