Abstract

Kunbarlang shows considerable variation in the word order patterns of nominal expressions. This paper investigates these patterns, concentrating on the distribution of noun markers (articles) and on attributive modification. Based on examination of spontaneous discourse and elicitation, I identify two main contributions of the noun marker: definiteness and predicative reading of modifiers. Furthermore, the order of adjectives with respect to the head noun is shown to correlate with information-structural effects. Taken together, these facts strongly support a hierarchical structure analysis of the NP in Kunbarlang. In the second part of the paper, Kunbarlang data are compared to the typology of determiner spreading phenomena. Finally, I entertain the prospects of a more formal analysis of the data presented and indicate their theoretical and typological relevance, including expression of information structure below the clausal level, typology of adnominal elements, and architecture of attributive modification.

1. Introduction

1.1. Kunbarlang

This paper deals with some aspects of nominal expressions in Kunbarlang, a polysynthetic Gunwinyguan language of northern Australia. Kunbarlang is currently spoken by fewer than 40 speakers in the age range of 30 to 70 years old, residing primarily in Warruwi (South Goulburn Island) and Maningrida. The present study is based on texts collected by Isabel O’Keeffe, Aung Si, and Ruth Singer in 2006–2015 as well as in the author’s original field work. The semantic characteristics of nominal expressions that I discuss here (e.g., familiarity, novelty, and restrictive readings) critically rely on the context in which those nominal expressions occur. For that reason, I confine my attention to the tokens that occur in narrations and dialogues; elicited examples are pointed out on the rare occasion when they are cited. Elicitation data would be useful for negative evidence, but at the present stage, such negative data are scarce.

Kunbarlang, like all Gunwinyguan languages, features rich verbal morphology (polypersonal agreement, argument derivation, and noun and adverb incorporation) that contrasts sharply with the extremely economical nominal morphology. Nouns do not have any inflectional morphology, but they are lexically specified for one of the four noun classes (grammatical genders). Noun class is an agreement category: all modifying and determining components of a nominal expression agree in noun class with the head noun (indicated in the gloss with roman numerals).1 It is a covert system, in the sense that a noun’s class only becomes apparent in the presence of agreeing dependents. This is not a noun classifier system, and there are no noun class markers in Kunbarlang.

The focus of attention is on the dual functioning of noun markers, which are a type of determiner, and on attributive modification, primarily that involving adjectives. It is shown that these two areas are tightly interconnected, and their interaction provides strong support for a hierarchical noun phrase in Kunbarlang, which is particularly important given the scarcity of other evidence in favour of NP constituency.

Kunbarlang is a discourse-configurational language, where the order of constituents in the clause does not encode their grammatical roles. Nominal expressions also boast a variety of orderings of their constituent parts, although they tend to be very short.2 Adjectives, possessors, and noun markers can occur before or after the noun (some elicited permutations of possessor and noun marker are shown in (1)). These word order facts raise questions about the structure of nominal expressions in this language. Indeed, given the genetic background of Kunbarlang, even the validity of the NP as a unit of analysis cannot be taken for granted: other Gunwinyguan languages, including the close relative Bininj Kun-wok (Evans 2003, pp. 229–31), show little evidence for the NP. Another Gunwinyguan language Wubuy (Heath 1986) played an important role in the discussion of nonconfigurationality phenomena in the 1980s, along with unrelated dependent-marking languages Warlpiri (Hale 1983) and Kalkatungu (Blake 1983), which also have free ordering within strings of nominals (apparently unconstrained in Kalkatungu, but with certain ordering preferences in Warlpiri; see Simpson 1991, pp. 130–34).3

- (1)

- IK1-180601_1SY1/38:21–43:22

- Nga-djarrang [mayi man-rnungu kandiddjawa].1sg.nf-eat.pst nm.iii iii-he.gen bread(iii)‘I ate his biscuit.’

- Nga-djarrang [mayi kandiddjawa man-rnungu].

- Nga-djarrang [kandiddjawa mayi man-rnungu].

Kapitonov (2021, pp. 106–7) argues that case marking provides one piece of evidence for NP constituency in Kunbarlang. Nouns in this language do not have case morphology but, in certain case positions, must be case-marked with the help of free pronouns, illustrated for a dative possessor in (2). In such constructions, it is argued that the noun must form a constituent with the pronoun, supporting the NP construal in Kunbarlang.

- (2)

- Nga-nguddu-wuy lerrk bi-rnungu Ngabbard.1sg.nf-2pl.obj-give.pst word dat-he.gen father‘I gave you the Father’s word.’ [IK1-160430_0001/04:13–16]

Determining personal pronouns (which are related but not identical to the case marking constructions) and demonstratives have a strong association with the left edge of nominal expressions (Kapitonov 2021, pp. 283–84)—a word order feature that is used as another piece of evidence for NP constituency (Louagie 2020, pp. 131–33).

In this paper, I further show that the Kunbarlang noun phrase warrants a hierarchical configurational analysis, its underlying structure betrayed by the seemingly disparate variety of surface patterns (cf. Louagie 2020, p. 132).4 This conclusion is arrived at by close observation of the various orderings and the associated semantic-pragmatic effects. Two main aspects under scrutiny are adjectives and noun markers. Noun marker is an established term (cf. Coleman n.d.) for the determining element in Kunbarlang that has a double function. One of its functions is the (adnominal) article in the sense of Himmelmann (2001), more precisely the definite article, as I show below. The other function is the linking article (henceforth linker; Gelenkartikel in Himmelmann 1997, §5.1), often occurring between a noun and its modifier. I adhere to the convention of calling these elements noun markers but frequently refer to their (definite adnominal) article and linker functions.

The primary aim of this paper is to establish structural facts about the organisation of the Kunbarlang nominal expressions, arguing for a hierarchical analysis instead of an appositional or flat structure. However, the issues treated here bear on some topics of current theoretical research, and in Section 5.2, I highlight these points of connection.

1.2. Determiners in Australian Languages

Articles, as a category dedicated to the determining function, are extremely rare in Australian languages.5 In a recent typological study, Louagie found two languages in her 100-language sample for which a category labeled ‘article’ was posited in the description (Louagie 2020, pp. 184–85), viz. Marra and Mawng, Kunbarlang’s close neighbour from the Iwaidjan family. The Mawng article is particularly interesting for the present study, as it bears a number of similarities to the Kunbarlang article. It can occur preceding the head noun (initial article) as well as preceding every other constituent of the noun phrase (linker). Forrester (2015, chp. 5) in a quantitative study shows that there is no difference in their obligatoriness and both the initial and the linker article can be omitted (contra Singer 2006, 2016). The conditions of its (non-)occurrence remain elusive, yet it has been observed that the article prevails in the post-verbal NPs but not in the ones in the pre-verbal position. Forrester suggested that it may be related to information structure sensitivity, potentially an avoidance of non-discourse neutral positions in front of the verb (e.g., p. 12).

Apart from Marra and Mawng, Baker (2008) argued that noun class prefixes in the Gunwinyguan languages Ngalakgan and Wubuy (similarly to Marra) function as articles that indicate topicality of the referent and the scope of clausal operators (rather than categories like definiteness or specificity). A handful of other languages in Louagie’s sample feature strongly grammaticalised adnominal personal pronouns (as in Nyulnyul) or demonstratives (as in Worrorra) that function similar to articles.

Indeed, in the absence of dedicated articles, the determining functions in the languages of Australia are typically carried out by a range of other elements: adnominal personal pronouns, demonstratives, possessives, interrogatives/indefinites, quantifiers, and comparative qualifiers (such as ‘same’ or ‘other’; Louagie 2020, §7.3). There are two notable characteristics in the use patterns of these determining elements, which are of immediate relevance for the coming discussion of Kunbarlang. One is their optionality: only three languages in Louagie’s sample have obligatory determiners, “in the sense that its absence also marks the feature it encodes” (2020, p. 182). The other is the absence of competition, meaning that more than one such determining element can occur within a single nominal expression.

To give a brief preview of what follows: against this Australian background, Kunbarlang is unusual in that it has a category of articles yet is very typical in that its determiners (which include adnominal personal pronouns and demonstratives, along with the articles) neither compete for the “determiner slot” nor are strictly obligatory, as will be detailed below.

The paper is organised as follows. In Section 2 I show that the Kunbarlang noun marker has the definite article function. Ordering patterns that form the core of the constituency argument are explored in Section 3. The discussion then extends to nominal expressions with several modifiers and the ‘compulsory indirect modification’ patterns that they incur. They are given a language-internal characterisation as well as a comparison with ‘overdetermination’ or ‘determiner spreading’ phenomena (Section 4). In Section 5, I discuss prospects for a formal analysis of these facts and indicate points of contact of this research with relevant issues in linguistic theory and typology. Section 6 concludes with a summary.

2. Noun Markers as Definite Articles

Kunbarlang has one article, called the noun marker here. There are other determiners, namely demonstratives and personal pronouns in determining function, but they do not play a role in the present discussion.6 There are no other article-like elements. Centrally for the ensuing inquiry, noun markers in Kunbarlang have two functions: they are responsible for marking definiteness (discussed in this section) and for adding modifiers to NPs, including formation of relative clauses (linker function; Section 3.1.2 and further). The noun marker agrees with the head of the noun phrase in its noun class, yielding the forms nayi, ngayi, mayi, and kuyi for classes I–IV, respectively, and can take the semantic plural form ngayi with neutralised noun class distinctions. As illustrated above, noun markers show variable placement (1). Indeed, they can recur within a nominal expression under a single intonational contour (3a; elicited), expressing both their functions—a property that takes center stage in Section 4. However, there is an important positional restriction: they cannot be the final element in the nominal expression (3b). A corollary of this is that noun markers do not appear by themselves and are not used as anaphoric devices (which is a typical function of noun classifiers, cf. Sands 1995, p. 248).

- (3)

- Nga-djarrang [mayi man-rnungu mayi kandiddjawa].1sg.nf-eat.pst nm.iii iii-he.gen nm.iii bread(iii)‘I ate his biscuit.’ [IK1-180601_1SY1/38:21]

- *Nga-djarrang [kandiddjawa man-rnungu mayi].

Before we can discuss their multiple occurrence, we need to spend some time on the basic steps of composition. In the present section, I justify the semantic characterisation of NMs as definite articles and then begin the discussion of modification patterns in Section 3.

Starting with the simplest nominal expressions, those consisting of a noun with one or no modifier, we observe that noun markers mark NPs as definite (4). Namely, definiteness in Kunbarlang means that the (discourse) referent of the nominal expression is familiar, either due to an antecedent in the text or else due to existence of some contextually salient referent (Heim 1982).

- (4)

- The speaker recounts her visit to a hospital and conversation with the doctor—the doctor is thus preestablished in the context:Karlu ngayi nga-ngun-wakwanj nga-ngunda.neg.pred I 1sg.nf-2sg.obj-ignorant.np 1sg.nf-do.pstNga-marnanj-ngunda nayi doctor.1sg.nf-ben-do.pst nm.i doctor‘No I don’t know you, I said. I told the doctor.’ [20060901IB02/07:10–14]

To wit, in contexts where the intended referent is novel/non-familiar, such as the de dicto object in (5a; elicited) or the phrase denoting the price (rather than any specific money) in (5b), noun markers do not naturally occur.

- (5)

- Ngayi nga-yawanj doctor la nga-rdukkumi-yinj.I 1sg.nf-seek.np doctor conj 1sg.nf-cut-refl.pst‘I am looking for a doctor because I cut myself.’ [IK1-170620_1SY1/13:41–45]

- Na-wanjak rrubbiya ngana-kalng mayi man-kang Adelaide, cheapi-little money 1du.excl.nf-get.pstnm.iiiiii-from A cheaponeone‘For little money we got the one from Adelaide, a cheap.’[20060901IB03/02:24–30]

As soon as the same nouns are in a context where they have a familiar (definite) referent, they appear with noun markers (4, 6b). The pair in (6) is particularly telling: the first instance of the noun rrubbiya is novel and is a bare noun, but it creates the discourse referent, and so, the second instance is familiar and marked with NM.

- (6)

- 20060620IB03/25:36–46

- Rrubbiya ka-nganj-kanginj, ka-nganj-kidanj ka-ngan-wuy.money 3sg.nf-hith-take.pst 3sg.nf-hith-go.pst 3sg.nf-sg.obj-give.pst‘He brought some money for me, he came and gave it to me.’

- Ka-ngan-marnanj-ngunda nayi kin-nungku rrubbiya nayi Djapani ki-kelkkuyinj.3sg.nf-1sg.obj-ben-do.pst nm.i i/ii-you.gen money nm. i Japaneseki-kelkkuyinj.2sg.nf-work.pst‘He told me, Your money, which you [earned when you] worked for the Japanese.’

The next example (7) further confirms that the relevant semantic feature is definiteness (and not, for instance, specificity). This is the beginning of a short narrative about the tradition of collecting mabudj ‘cheeky yam’. The first mention of mabudj is with a bare noun, as it is novel. The yams themselves remain non-specific throughout the story, i.e., there are no specific yam bulbs that are referred to. However, the first mention of mabudj ‘yam’ in (7a) creates a discourse referent, a discourse entity independent of the real-world referent. It is by virtue of that discourse referent that the topic of the story, the yam, is treated as familiar and from then on is tracked by NMs. Notice that in this, I follow the view, originating from Ihsane and Puskás (2001), that definiteness and specificity are independent of each other.

- (7)

- 20060830IB01/00:09–18

- Kadda-kidanj ngayi mimdom~mimdom kadda-kidanj kadda-bum3pl.nf-go.pst nm.pl rdp~old_person 3pl.nf-go.pst 3pl.nf-hit.pstmabudj kadda-rda-yinj korro djunguyu.cheeky_yam 3pl.nf-put-refl.pst dem.med.loc bush‘People of old used to go gather yams, they entered the bush.’

- Kadda-warrenj kadda-yawang mayi mabudj.3pl.nf-move.pst 3pl.nf-seek.pst nm.iii cheeky_yam‘They browsed around looking for the yam.’

A pilot study of four texts recorded from four different speakers further confirms this analysis. These texts contain 118 NPs with overt noun heads, out of which 32 have a NM immediately preceding the head (the significance of their position is detailed below). Out of these NPs with NMs, 84% are familiar. Conversely, 90% of the nouns without (immediately preceding) noun markers head NPs with novel referents. This indicates that familiarity is indeed the main factor in the distribution of noun markers. The remaining five NPs that have an NM but not a familiar referent will need to be analysed further for the additional factors, ideally within a larger corpus study.7 The same holds for the remaining nine familiar NPs without a noun marker, which may or may not be symptomatic of the “Australian-style” optionality of deteminers.

Having established that Kunbarlang noun marker functions as the definite article, I shall henceforth assume that at least some of the nominal expressions in Kunbarlang are determiner phrases (DPs), viz. those structures where a NM immediately precedes the noun, indicating definiteness.8 I remain agnostic about a null indefinite article and refer to such nominal expressions as noun phrases (NPs) for want of DP evidence currently.

However, not every instance of a noun phrase that contains a noun marker is definite. Consider (8):

- (8)

- [Mulurrmulurr ngayi kin-karrkeyang] la [mulurrmulurr ngayiwading.bird nm.ii ii-clean conj wading.bird nm.iikin-ngongokwarri].ii-dirty‘The white ibis [or spoonbill; Threskiornitidae] and the black ibis.’[20060620IB04/06:46–50]

Recalling various birds that used to be the typical game, the speaker uses the two conjoined nominal expressions in (8) to refer to novel/indefinite kinds (not individuals or pluralities of individuals). I shall argue below that, in examples such as (8), noun markers in their linker function make a different semantic contribution. Configurations in which the noun marker does not convey definiteness are further discussed in the following section.

3. Modification: Adjectives and Other Attributes

Modification with multiple modifiers appears very limited in Kunbarlang. On the one hand, NPs with two modifiers are extremely infrequent and three modifiers have not been attested so far. On the other hand, having more than one modifier requires a certain syntactic configuration involving noun markers (Section 4). In this section, we first look at the more basic patterns of modification, i.e., how a single adjectival modifier is used and what role noun markers play in that. At present, adjectives are better understood than other modifier types, and in this section, I concentrate on them. Quantifiers, possessives, and relative clauses are characterised more briefly in Section 3.2.

Since Australian languages frequently manifest weak distinction between nouns and adjectives (only about one third in Louagie’s (2020, ch. 3) 100-language sample show clear morphosyntactic distinctions), it is worth noting that Kunbarlang has a class of adjectives that is clearly distinguishable from nouns (Kapitonov 2021, §3.2.2). Differences between nouns and adjectives include their relation to noun class (lexically specified for nouns, but an agreement category for adjectives—as well as other modifiers) and the ability of adjectives but not nouns to bear the inchoative suffix and to incorporate nouns.

3.1. Adjectives

Let us first consider a non-elliptical noun phrase with one adjective. Adjectives in Kunbarlang are found both preceding and following nouns, and noun phrases are found with or without noun markers. Given that noun markers are prohibited in NP-final position, in the presence of a noun marker, there are four word-order permutations possible. These are defined by two parameters: the relative order of the noun and the adjective, and whether the noun marker is left-peripheral or medial. In the absence of a NM, there are another two possibilities, viz. the adjective following or preceding the noun.

3.1.1. Position of the Adjective

Now, irrespective of the presence of the noun marker, postnominal attributive adjectives associate with neutral contexts (9) while prenominal ones carry a certain emphatic ‘colouring’ (10).

- (9)

- Bilem ma-rlengbinbin ngadda-kanginj.bark.canoe iii-big 1pl.excl.nf-take.pst‘We brought a big canoe.’ [20140709IOv05/03:55–57]

- (10)

- Na-warri nginjeng, nga-rlakwang, nga-woh-karrmeng…i-bad thing 1sg.nf-throw.pst 1sg.nf-incp-handle.pst‘Bad thing, I chucked it, I got it by mistake…’ [RS1-140/24:02–05]

- La ma-wanjak mayi welenj?conjiii-little nm.iii road‘The small road?’ [IK1-170610_2SM1/54:04]

For instance, (10b) is uttered as a clarification question during a spot-the-difference game, in the context where there are several paths/roads in the picture and this player’s partner has just asked about a road (Mayi welenj birlinj ka-ngundje? ‘What is the road like?’). Thus, the adjective here is under contrastive focus. Impressionistically, there is a pitch accent on the fronted adjective in such examples. In (11), again, a contrast is drawn between two social groups (which are in the subset relation), and the fronted adjective signals contrastive focus on the ‘bigness’ property of the Mirrangkangu patriclan.9

- (11)

- Ngalngarridj nginda Mandjulngunj, but Mirrangkangu nayi na-rlengbinbin nguya bi-ngadju.N dem.prox.i clan_name but clan_name nm.i i-bignguya bi-ngadju.patriclan dat-she.gen‘Ngalngarridj is Mandjulngunj, but Mirrangkangu is her big nguya (patriclan).’[20150413IOv01/07:46–50]

Thus, I treat the postnominal position of attributive adjectives as the basic order, from which the prenominal adjective order is derived. This idea is elaborated in Section 3.3, after the noun marker patterns have also been introduced.

3.1.2. Position of the Noun Marker

The variation in the position of the noun marker has a different interpretive effect than that of adjectives. In the first approximation, it can be described as in (12).

- (12)

- when the NM immediately precedes the adjective (phrase), this yields a restrictive reading

- when the NM immediately precedes the head noun, this yields a definite reading, by now familiar from Section 2

Let us start with the relevant terms. In languages with large adjectival systems, such as English, adjectives form subclasses with respect to how their meaning composes with that of the modified noun. For the present discussion, it is relevant that they can be divided into intersective (red, wet, and carnivorous) and non-intersective adjectives, with the latter including adjectives such as alleged or (Partee 1995), former. The crux of their compositional distinctions lies in how they combine with the noun: assuming that common nouns denote sets of individuals, only intersective adjectives combine with them by set intersection (whence their name). Thus, a red square denotes something that both is red and is a square. The other types incur more complex interactions: notice, for instance, that a former pilot does not denote someone who is a pilot, and it hardly makes sense to say that it is someone who is former. Such non-intersective adjectives have been argued to modify nouns in a different way, not extensionally as set intersection but intensionally, being functions from noun meanings to noun meanings. It is important for the present discussion that not all modifiers combine with nouns via set intersection.

The second distinction between restrictive and non-restrictive readings is familiar from the typology of relative clauses, but it is relevant for adjectives, too. To borrow an example from Greek (which is also relevant in Section 4), consider the contrast in (13).

- (13)

- Greek (Indo-European; Panagiotidis and Marinis 2011, p. 272)

- i ikani erevnites tha eprepe na apolithun.the competent researchers fut had.to sbjv fired.3pl‘the competent researchers should be fired.’ (restrictive or non-restrictive interpretation)

- i ikani i erevnites tha eprepe na apolithun.the competent researchers fut had.to sbjv fired.3pl‘just the competent researchers should be fired.’ (restrictive interpretation strongly preferred)

The intuition reported for the Greek contrast in (13) is that, in (b), it is understood that a proper subset of researchers would be fired, whereas (a) is ambiguous between this restrictive reading and the other, non-restrictive one, which conveys that all researchers would be fired—and furthermore that they are all competent. In essence, this is the nature of restriction: narrowing the reference, i.e., the set being picked out by the (composite) nominal expression. One further point that is important to highlight here is that, inasmuch as restriction by an adjective concerns set membership, it relies on that adjective being intersective (similarly for relative clauses). Thus, a restrictive reading is available only for intersective adjectives; however, not every use of an intersective adjective is necessarily restrictive and in neutral contexts ambiguity is normal (cf. 13a).

In Kunbarlang, I have so far identified two ways of enforcing the restrictive reading: contrastive focus (as in (10b) above) and a noun marker immediately preceding the adjective (the formal resemblance of this strategy to the Greek construction in (13b) will be taken up in Section 4). Consider an example of the N–NM–AP order in (14). It comes from the beginning of a story, whereby the protagonists are still introduced and gives the first mention of a novel spirit being which is not yet familiar. The adjectival phrase headed by -kang ‘originating; from’ and describing the provenance of the spirit restricts the reference of the NP from among the other possible Djawandji.

- (14)

- La barninda nukka, djawandji nayi [APna-kangkenda], na-kang Kadjirramu.conj ignor he.I spirit nm.i i-from dem.prox.loci-fromKadjirramu.K‘And what’s it called, a Djawandji spirit from here, from Kadjirramu.’[20150212AS01/03:01–07]

This can be contrasted with an example where the reference does not need to be restricted in a similar way, as the referent here only is mentioned in passing and the non-restrictive reading is preferred (15).

- (15)

- Ka-ngunda married na-kang King River.3sg.nf-do.pst marry i-from K.R.‘She married [a man/someone] from King River.’ [20150206AS03/00:19]

The same interpretive effect is found if the adjective in prenominal position is accompanied by a noun marker. Especially illuminating is example (16), albeit the adjective here is an English loan.10

- (16)

- Yoh if ki-karrme nayi [APrealquiet] djarrang, kun-mak.yes if 2sg.nf-handle.np nm.I real quiet horse iv-good‘Yeah if you get a really quiet horse, that’s good.’ [20070108IB01/21:42–46]

The situation described in (16) is hypothetical, and even though horses are an ongoing topic at that moment, this hypothetical horse is a new discourse referent (thus, indefinite). The adjectival phrase that modifies it receives a restrictive reading. In fact, this effect of reference restriction is also found with nouns as modifiers (17b), which are more rare compared to adjectival modifiers.

- (17)

- 20150212AS01/05:12–19

- Ka-rninganj ka-burrun-ngunga::ng man-barrkidbe ka-kalng.3sg.nf-sit.pst 3sg.nf-3du.obj-growl.pst iii-other 3sg.nf-get.pst‘He sat there growling at them, then he got another one.’

- Kundulk mayi mulurr mukka ngorro.tree nm.iii driftwood it.iii dem.med.iv‘A log that was a driftwood, that is.’

Again, in (17b), we see that the phrase mayi mulurr restricts the reference of kundulk, which by itself can be a small stick, a log, a tree.

Insofar as the noun marker immediately preceding an adjective has an effect on that adjective’s interpretation, it partakes in constructing the modification structure. It is in this sense that noun markers have the linker function, in addition to the definite article function. Let us call modifiers with NMs indirect; those without NMs, to which I turn presently, are, accordingly, direct.11 In Section 4, I show that direct modification is limited in Kunbarlang.

Returning to our permutations, when the noun marker immediately precedes the noun (that is, the order NM–N–A), we find the definite reading of the NP. Example (18) from the spot-the-difference game provides a clear contrast to (16) in this respect:12

- (18)

- la manda mayi balabbala man-barrkidbe…conjdem.prox.iiinm.iii platform iii-other‘…and [on] the other platform…’ [IK1-170610_2SM1/56:41–44]

In (18), the reading is definite, referring to the smaller of the two platforms in the picture. However, the adjective is used non-restrictively here and correspondingly is without a noun marker. The referent is indeed contrasted to another one in virtue of the meaning of -barrkidbe, but crucially, this is not because the platform(s) that have the property of “other-ness” are contrasted with platform(s) that do not have it. Furthermore, the adjective here cannot be restrictive, as it is non-intersective. This is a tentative characterisation, as at present, there are no data to unequivocally define a class of non-intersective adjectives in Kunbarlang.13 However, indirect support comes from the quantitative distribution: we compare the adjectives that, on the basis of their meaning, would be expected to be non-intersective (19a–b) to some intersective ones (19c–d) in terms of how often they are found with an immediately preceding noun marker. Here are some counts from the available corpus:

- (19)

- -barrkidbe ‘other’: 1 out of 50 (2%)

- -rleng ‘’: 1 out of 28 (4%)

- -wanjak ‘little’: 14 out of 65 (22%)

- -rlengbinbin ‘big’: 18 out of 56 (32%)

On the view advanced here, viz. that there is a connection between the noun markers and restrictive readings (which rely on set intersection), (19) is exactly the predicted contrast. Non-intersective adjectives cannot appear with noun markers, and intersective ones can (but do not have to, of course).14

Davidse and Breban (2019, pp. 351–57) classify adjectives such as same, different, and (an)other as secondary determiners, explaining that “[s]emantically, adjectives realizing the secondary determiner function do not describe the referent of the NP but have a reference-oriented function”. This echoes the contrast I have drawn above, since restrictive readings rely crucially on description of the referent by the modifier. However, restriction, of course, is but one way of modifying reference. Secondary determiners are another, in that they “convey general grammatical, viz. determining, meanings” such as non-coreferentiality. Davidse and Breban (2019) further pointed out that some of them are polyfunctional and can also function as descriptive adjectives (‘epithet function’), e.g., different as ‘another referent’ (secondary determiner) and as ‘distinguished by some traits’ (epithet). The Kunbarlang -barrkidbe is only found used in the secondary determiner function, whereas the ‘unsimilarity’ meaning is usually conveyed by negating the verb -birrinja ‘to be same’.

The optionality of determiners, mentioned above, seems to be of relevance for this linker function of the Kunbarlang noun markers. In particular, the linker can be missing when restriction is performed by contrastive focusing (10b), which suggests that the linker is not automatically triggered by the semantic feature of restriction but rather reflects the speaker’s choice to highlight such a reading. At the same time, I have not found a good example yet where an adjective that is clearly to be interpreted restrictively is used in the postnominal position without an accompanying noun marker. It would be very interesting to explore the interaction of linkers and contrastive focusing in the future: Is it predictable which of them is used when? Is it marked to use both of them compared to using either one? At present, however, it is very important to stress that the absence of a linker with an adjective does not necessitate a non-restrictive reading. Rather, when the non-restrictive reading is intended, the adjective is used without a NM. Moreover, non-intersective adjectives may not combine with noun markers, as I tried to show with the example of ‘other’ above.

Bowern (2012, pp. 335–36) observed analogous principles being operational in Bardi, albeit the ordering details differ from Kunbarlang. In Bardi, prenominal adjectives are neutral or restrictive, whereas the postnominal position of adjectives seems marked and associated with the non-restrictive reading.

3.1.3. Towards a Hierarchical Structure

To sum up this section, the striking correlation of different readings with the noun marker placement is an important piece of evidence for hierarchical organisation of Kunbarlang noun phrases. Crucially, if the structure of these NPs was flat or appositional (e.g., [N NM A] or [N] [NM] [A]), there would not be any effect of the order of composition and one would expect fewer contrasts. For instance, any occurrence of a noun marker would yield the definite reading regardless of its position. Instead, the interpretive effect of the observed four orders strongly supports the following bracketing:

- (20)

- [N [NM A]] novel; restrictive; see (14)

- [NM [N A]] familiar; non-restrictive; see (18)

- [[NM A]i N ti] novel; restrictive, focused A; see (16)

- [Ai [NM [N ti]]] familiar; focused A; see (10b)

As indicated by the traces in (20), I claim the two orders with prenominal adjectives to be derived from the postnominal position of the adjective by movement. This idea is developed in Section 3.3. Another tentative argument for a hierarchical analysis comes from nominal expressions without a head noun and is reviewed in Section 4.2.

3.2. Other Modifiers

This paper’s central focus are attributive adjectives, but other modifiers are important for the understanding of the proposed structure of DPs, especially the structures to be discussed in Section 4. In particular, these include quantificational expressions, possessives, and relative clauses.

3.2.1. Quantifiers

Many of the Kunbarlang existential D-quantifiers morphologically are adjectives. Unlike attributive adjectives, however, quantifiers overwhelmingly precede the head noun and, in this prenominal position, may be either neutral (21a) or emphasised (21b).

- (21)

- Mawuludja ngadda-bing. Kaburrk bala man-kudji kubbunj bilem.M 1pl.excl.nf-emerge.pst two and iii-one boatbilem.bark.canoe‘We arrived at Mawuludja, [in] three canoes.’ [20140709IOv05/01:23–30]

- Ngana-mabulunj‘‘ku-rleng lerrk nj-ngarrun-wunj.1du.excl.nf-like.np iv-much word 2sg.fut-1du.obj-give.np‘We two want you to give us lots of words.’ [20150413IOv01/11:52–55]

It is a well-established view in the literature on DP structure that numerals and quantifiers are associated with a projection—call it NumP—above the NP including attributive adjectives (e.g., Borer 2005; Cinque 2005; Heycock and Zamparelli 2005). The data of Kunbarlang numerals are in line with this understanding.

3.2.2. Possessives

In the expression of possession, Kunbarlang has an alienability distinction. In the inalienable construction, the possessor encliticises to the possessed noun, and I do not discuss this construction further. For alienable possessums, there are two constructions (Kapitonov 2021, §4.6.1). In the ‘agreeing’ construction, the genitive possessor bears a prefix indexing the noun class of the possessum and preferentially precedes it (22). In the other, the dative-marked (and non-agreeing) possessor preferentially follows the possessum (23).

- (22)

- Korro kun-rnungu yalbi.dem.med.lociv-he.gen country(iv)‘In his country.’ [20060831IB03/05:20–22]

- (23)

- Ngalngarridj nginda Mandjulngunj, but Mirrangkangu nayi na-rlengbinbin nguya bi-ngadju.N dem.prox.i clan_name but clan_name nm.i i-bignguya bi-ngadju.patriclan dat-she.gen‘Ngalngarridj is Mandjulngunj, but Mirrangkangu is her big nguya (patriclan).’[20150413IOv01/07:46–50]

The genitive or dative pronoun is an obligatory part of the construction and is present both when the possessor is pronominal and when it is nominal (Kapitonov 2021, §4.4.2; see example (2) above for a nominal possessor in construction with a pronoun).

Normally, neither agreeing nor dative possessors use a noun marker. Furthermore, in examples such as (6b), where the order is NM–Poss–N, the possessor is clearly ‘transparent’ for the noun marker: the NP is definite, and no contrast or other marked interpretation is discernible for the possessor.

In Section 4.2, I show that possessors nevertheless participate in indirect modification under the right conditions.

3.2.3. Relative Clauses

Headed relative clauses in Kunbarlang are postnominal and are constructed with a gap and a noun marker (24; elicited). The verb does not carry any special marking. Kapitonov (2021, §8.4) argues that Kunbarlang relatives are interpreted restrictively and that there is no evidence for appositive RC.

- (24)

- Ngayi nganj-kinje nayi kornobolo [RCnayi ngudda ki-djung].I 1sg.fut-cook.np nm.I wallaroo nm.i you.sg 2sg.nf-pierce.pst‘I’ll cook the wallaroo that you speared.’ [IK1-160505_1SM1]

In contrast to adjectival modification, where NPs with just an adjective and a noun are common (see (5b) and (9)), relative clauses overwhelmingly use at least one noun marker, i.e., before the head noun or before the clause (Kapitonov 2021, p. 333). In constructions with multiple modifiers presented below, there is always a NM at the left edge of the clause.

3.3. Information Structure in the Kunbarlang NP

In this section, I make first steps towards an analysis of the noun phrase structure in Kunbarlang. Based on the observations presented in Section 3.1, there are these basic facts that need to be accounted for:

- The adjective can appear on either side of the noun, with the following interpretive difference:

- Preceding the noun, it conveys a sense of emphasis that I identify here as the focus.

- Following the noun, the adjective has a(n information-structurally) neutral reading.

- The noun marker can immediately precede either of the two, whereby (regardless of the mutual order of the noun and the adjective):

- If it immediately precedes the noun, the NP receives the definite reading.

- If it immediately precedes the adjective, the adjective must have the restrictive reading....

Since adjectives receive a neutral reading in the postnominal position, I analyse it as the basic order: [ N [AP]]. The marked order A–N is derived. Displacement is a well-known and widespread correlate of information-structural markedness (Mallinson and Blake 1981, p. 152, Erteschik-Shir 2007), and Kunbarlang seems to be no exception to the rule in this respect. A number of Australian languages are reported to employ such displacement within the noun phrase to information-structural ends (Bardi (Bowern 2012, pp. 273–74), Tiwi (Lee 1987), Warlpiri (Laughren 1984); see Reinöhl 2020, pp. 86–9 for examples and a nice discussion). I follow the standard analysis within the generative framework, where IS-marked constituents move from their thematic position to the specifier of a respective functional head. For example, in the influential “cartographic” approach, the left periphery of the clause (CP) comprises a number of such heads, including the ones dedicated for focus and topic (Rizzi 1997). In Kunbarlang, emphatic adjectives are not associated with a certain position in the clause: they may occur at its left edge (10a) as well as after the verb (16). Thus, a dedicated clausal position is unwarranted. Instead, I assume that a (phonologically null) head Foc takes a noun phrase as its complement and attracts an element of it into its specifier (25). This head provides the focus semantics for the constituent in its specifier (e.g., alternative semantics, Rooth 1992).

- (25)

- [ AP [ Foc [ N ]]]

The second phenomenon, concerning the noun marker, is not as typologically robust, although it is not unique either. To the extent that it involves an interaction of a determiner with a modifier, it is related to linkers and, more broadly, to the small but motley family of determiner spreading phenomena (also known as overdetermination). We turn to these, by way of comparison with the NM patterns in Kunbarlang, in Section 4.3.

4. Compulsory Indirect Modification in Kunbarlang

At the end of the previous section the patterns of Kunbarlang NM distribution within the noun phrase (i.e., immediately preceding nouns or adjectives) were provisionally tied to phenomena such as linkers and determiner spreading. Linkers are a type of article that ‘links’ the head and the attribute, frequently occurring between them (Himmelmann 1997, §5.1). Among the languages with linkers, Kunbarlang is closer to the Albanian than to the Tagalog type. In Albanian and in Kunbarlang , the linker forms a unit with the modifier and thus can appear at the left edge of the nominal expression, if the adjective is fronted for emphasis (26). By contrast, in Tagalog, the linker occurs between the head and the modifier regardless of their order.

- (26)

- Albanian (Indo-European; Buchholz and Fiedler 1987, p. 328 via Himmelmann 1997, p. 169)e bukur-a vajzëlnk.nom.sg.f pretty-def.nom.sg.f girl:indf.f‘the pretty girl’

A number of languages that have linkers manifest determiner spreading phenomena, viz. occurrence of determiners with NP modifiers in addition to the ones marking the head (Alexiadou 2014; see also Plank 2003). To the extent that there can be multiple noun markers in a Kunbarlang NP, the determiner spreading typology is relevant for the patterns discussed here. In Section 4.3, I show that there are substantial similarities between the Kunbarlang noun marker patterns and the Greek determiner spreading.

4.1. Multiple Noun Markers with a Single Modifier

The single-modifier nominal expressions with multiple noun markers are in fact just those cases where the two functions of the noun marker discussed in Section 3.1 are combined. The noun marker preceding the noun marks definiteness, and the one grouped with the modifier provides the restrictive reading. The relevant kinds of modifiers here are adjectives (27) and relative clauses (24).

- (27)

- 20160413IOv01/02:22–33

- Nginda Mirrangkangu nguya.dem.prox.ii clan_name patriclanNginda ngayi ngana-rna kikka Mirrangkangu.dem.prox.ii i 1du.excl.nf-sit.np she clan_name‘She is Mirrangkangu patriclan. My wife [kinship verb; lit. ‘we two sit’], she is Mirrangkangu.’

- Mandjulngunj but Mirrangkangu nayi nguya nayi na-rlengbinbin.clan_name but clan_name nm.i patriclan nm.i i-big‘Mandjulngunj, but Mirrangkangu is the big patriclan.’

Here, in (27b), we find two instances of the class I noun marker nayi, each of them fulfilling the appropriate function. That is, the DP is construed as definite (the patriclans are introduced in the preceding context (27a)), hence the NM in front of the noun. The attributive adjective has a restrictive reading (contrasting the big nguya to the smaller one), hence the NM in front of the adjective.

4.2. Multiple Modifiers: Obligatoriness and Interpretation

Nominal expressions with more than one modifier are more unusual: they are rather rare and all include just two modifiers. Example (28) comes from elicitation and includes, besides two modifiers, a demonstrative:15

- (28)

- [Manda mabudj [mayi man-warri] [mayi nabuk man-rnungu]]dem.prox.iii cheeky_yam nm.iii iii-bad nm.iii he iii-he.genka-rna ka-ngarrkun-wunj.3sg.nf-sit.np 3sg.nf-1.incl.obj-give.np‘He keeps giving us these yams of his that are rubbish.’ [the speaker’s comment:‘These yams, it’s belong to him, it’s no good, he’s always giving us.’][IK1-180606_2SY1/01:09:50–55]

The DP in (28) shows the maximal length of nominal expressions in the available corpus of Kunbarlang. If contains the head noun mabudj ‘yam’, two modifiers ‘bad’ and ‘his’, as well as a demonstrative. Notice that each of the two modifiers is preceded by a noun marker. Incidentally, notice also the way the consultant rendered his explanation of the example, parcelling it into small predicative chunks; I return to this in Section 5.1. The noun is not accompanied by a NM, even though the reading is definite—presumably, this is due to the presence of the demonstrative, which suffices to mark this phrase as definite, thus rendering the noun marker redundant and optional. The sentence is modelled on a story in which the adjective ‘bad’ is used restrictively: ‘just those selected bad ones’. This is in accord with the analysis offered above. The possessor, however, can hardly be judged as restrictive.

Recall from Section 3.2 that alienable possessors do not partake in the restriction effect characteristic of adjectives and are ‘transparent’ for preceding noun markers. Interestingly, when in more-than-one-modifier situations, such as (28), they take part in the obligatory syntactic marking with nouns markers, albeit seemingly without the semantic effect. Consider the sequence A–Poss–NM–N in (29), which is rejected.

- (29)

- *manda man-warri man-rnungu mayi mabudjdem.prox.iiiiii-bad iii-he.gennm.iii cheeky_yamintended: ‘this bad yam that belongs to him’ [IK1-180606_2SY1/01:07:50–57]

My account of the issue with (29) is that there are ‘not enough’ noun markers. Considering these and other examples (including (23) above with the order NM–A–N–Poss), I offer the following generalisation that aims to capture the attested patterns and to explicate the vague notion of ‘enough noun markers’:

- (30)

- In Kunbarlang, a modifier can combine with the noun directly (i.e., without a mediating noun marker), but such composition renders the resulting noun phrase inaccessible to further direct modification. NM-modification remains available.

The generalisation in (30) does not specify which modifier is to combine with the noun first; for instance, possessors are not given special status. Example (31) suggests that this is correct, as it is the possessor that has a NM whereas the adjective does not:

- (31)

- [[Mayi nabuk man-rnungu] [mayi mabudj man-warri]] ka-rnanm.iii he iii-he.gen nm.iii cheeky_yam iii-bad 3sg.nf-sit.npka-ngarrkun-wunj.3sg.nf-1.incl.obj-give.np‘He keeps giving us his bad yams.’ [IK1-180606_2SY1/01:15:32–38]

The foregoing focused on the (non-)occurrence of NMs accompanying modifiers. Their occurrence with nouns is regulated by considerations of definiteness, i.e., in the same way as with any noun, whether modified or not. Example (32) illustrates this with a noun phrase referring to a kind, which is not definite and does not have a NM in front of the noun.16 Here, the NP refers to a kind. Moreover, sometimes the NM that would accompany the noun can be left out when definiteness is signaled by another definite determiner, such as the demonstrative in example (28) above.

- (32)

- Mulurrmulurr ngayi kin-karrkeyang [RCngayi ka-karrmi spoon] kikkawading.bird nm.ii ii-clean nm.ii 3sg.nf-handle.np spoon shengorro ngadda-buni.dem.med.iv 1pl.excl.irr.pst-hit.irr.pst‘The white mulurrmulurr, the one with the spoon [i.e., royal spoonbill, Platalea regia], that one we hunted.’ [20060620IB04/07:05]

With the caveat regarding possessors, which do not show the same systematic effect as attributive adjectives, compulsory indirect modification in Kunbarlang preserves the semantic effects of the NMs as discussed in Section 3.1.2. The fact that indefinite and generic NPs lack the NM at their left edge (as in (32)) is the first indication of that. There is further evidence for genuine semantic contribution of NMs in example (32). The head noun, mulurrmulurr, refers to several wading birds that inhabit the area, including several ibises and a spoonbill (Coleman 2010, p. 87). The only spoonbill is white, but ibises can be white (the Australian white ibis) or dark (the Glossy ibis). Thus, arguably, both modifiers increase informativeness by narrowing the reference: first, the adjective restricts the wading bird to a white one, and next, the relative clause picks out the spoonbill rather than the (white) ibis. Thus, we conclude that both modifiers are restrictive in (32).

To give an interim summary, using more than one modifier within the Kunbarlang noun phrase requires a distinct construction: at most one ‘direct’ modifier is allowed, and the others are obligatorily preceded by a NM. In this sense, as a syntactic mechanism for extended attributive modification, indirect modification is obligatory. This raises very interesting questions about the nature of modification, doing justice to which will require substantial further work. Is it the Kunbarlang noun which is responsible for the restriction in (30), being able to track the amount of modifiers and unable to combine ‘directly’ with more than one? Or is it the Kunbarlang adjective which in its bare form is a semantic functor only from nouns to noun phrases—while the ‘indirect’ modification is omnivorous and can take both nouns and NPs as its semantic argument? I return to questions about the analysis in Section 5.

This compulsory indirect modification also raises an interesting question specifically about the adjectives that were tentatively identified as non-intersective above (e.g., -barrkidbe ‘other’ and -rleng ‘much’): can they be used in such constructions, where the ‘predicative configuration’ might be enforced upon it? Or, do they need to be arranged as a separate NP, e.g., as an afterthought? In fact, there is one known example, where the adjective -barrkidbe appears in a separate intonational unit and thus arguably is a separate nominal expression, coreferential with the other multi-word DP. Of course, that in itself does not necessarily reflect inability of such modifiers to occur in a larger phrase, so this remains an issue for future work.

In Section 3.1.3, I alluded to evidence from elliptical NPs in favour of the structured analysis of the Kunbarlang NP. Such elliptical nominal expressions may consist of a single attribute only (cf. the quantificational adjective naworrhbam in (33)). However, if such an elliptical nominal expression includes more than one modifier (as the object in the second clause of (33)), then at least one noun marker seems obligatory. No negative evidence is available at the moment, however, so this conjecture is based on the fact that in argument positions no A–A strings have been attested.

- (33)

- Ka-kalng na-worrhbam, la na-barrkidbe nayi nguyuyi ngunda3sg.nf-get.pst i-few conj i-other nm.i many notki-kala.3sg.irr.pst-get.irr.pst‘He caught a few [fish], but many others he didn’t catch.’[IK1-160701_0001/56:21–28; picture description task]

The reasoning is this: If an appositional construal were available in Kunbarlang, then we should expect that two adjectives can be placed appositionally, each in its own phrase, each potentially without a NM. That seems not to be the case, however. The noun marker that occurs here is suggestive of one nominal constituent where the parts enter some relation, one of the adjectives conditioning the occurrence of the NM with the other. Notice that it is not clear that nayi nguyiyi should be interpreted restrictively. Assuming a null noun head, one can analyse this as involving one direct and one indirect modifier, i.e., an instance of compulsory indirect modification. Thus, (33) is naturally accounted for on the current analysis of the Kunbarlang NP. Of course, this remains tentative until the predictions can be verified. Namely, A–A strings under a single intonational contour are predicted to be possible only when preceded by a NM, i.e., in a focus-fronted configuration: [[NM A] A], or somewhat more precisely [[NM A] A].

4.3. Typological Placement

As I mentioned above, some languages have multiple determiner marking phenomena (also known as double articulation, overdetermination, determiner spreading, determiner doubling, polydefiniteness, etc.; some of the terms emphasise slightly different aspects of the phenomenon, or its sub-types, cf. Alexiadou 2014, pp. 3–4). I refrain from identifying Kunbarlang as e.g. a “determiner spreading language”, but the multiple noun markers in the Kunbarlang NPs make it interesting for comparison with that typology. Among such languages, the patterns manifest in Greek determiner spreading (DS) are closest to those found in Kunbarlang. The similarities include:

- Obligatoriness, but only under certain syntactic conditions: in Greek, DS is obligatory for adjectives that appear postnominally (and optional for prenominal ones). In Kunbarlang, indirect modification is obligatory beginning with addition of a second modifier in the NP. In Romanian, by contrast, determiner doubling is genuinely optional (Plank 2003, §2.4.1).

- (Typically) restrictive reading: in both languages, an article that precedes a modifier requires it to be intersective (cf. (13); for examples of non-restrictive readings in Greek, see Panagiotidis and Marinis 2011, p. 273). In Hebrew, by contrast, adjectives preceded by determiners can be non-intersective (see Alexiadou 2014, p. 81 and references therein).

- Number of determiners in the DP: in both languages, there can be determiners in a DP with n modifiers. By contrast, in Romanian, only one is possible (in addition to the affixal article on the noun).

- Word order of noun and modifiers: in both languages, modifiers-with-determiners can both precede and follow the noun. In Maltese, by contrast, adjectives are confined to postnominal position, whether accompanied by determiners or not (Plank 2003, pp. 350–51).

However, there are points of contrast between Kunbarlang and Greek, too:

- Type of modifier: in Greek, only adjectives undergo DS. In Kunbarlang, similar to Romanian, other modifiers participate in the construction.

- Definiteness of the noun: in Greek, the head noun must be marked by the definite article. In Kunbarlang, similar to Albanian (26), the NM immediately preceding the modifier is independent of whether the head is also marked with a NM.

Largely due to these observations and partly due to the fact that Greek has enjoyed most of the theoretical work so far, I draw some inspiration from the existing analyses of Greek DS when I discuss the prospects of an analysis for Kunbarlang in Section 5.

5. Discussion

In this section, I make some provisional observations about a possible analysis of the facts presented in this paper (Section 5.1) and then discuss some further points of connection of this research with the current theoretical and typological context (Section 5.2).

5.1. Perspectives on an Analysis

In Section 4, I argued for the view of Kunbarlang compulsory indirect modification, which holds that (i) it is a syntactic mechanism for extended attributive modification within noun phrases, whereby (ii) the individual instances of NMs have their regular interpretive effects, which depend on the composition: definiteness and set restriction. These facts should be the starting conditions on an adequate analysis of the pattern. Ideally, the analysis would also provide insight into the polyfunctionality of NMs as definite articles and restrictive relators and would be straightforwardly compatible with the information-structural effects of fronting (Section 3.3). Here, I entertain just two possible directions, which at least satisfy (i) and (ii).

One type of analysis takes adjectives with articles to be reduced relative clauses (RRCs; e.g., Alexiadou 2014; Alexiadou and Wilder 1998; Sproat and Shih 1987. Its biggest strength is that it offers a natural account of the semantic interpretation of such adjectives. Moreover, in the languages where it was applied, the parallel is supported by restrictions on non-intersective adjectives both in the DS construction and in relative clauses. The fact that NMs are used both in the adjectival indirect modification and in RC constructions (as well as that RCs are among the modifiers that partake in compulsory indirect modification) makes it very appealing for Kunbarlang, too.

At the same time, such an approach leaves a number of questions, some of which are of a conceptual nature and some relate to the empirical specifics of Kunbarlang. On the conceptual side, the motivation for movement needs to be made precise (assuming the raising analysis of relativisation). For Kunbarlang specifically, the contribution of possessors remains to be understood: Are they intersective? Do they have exactly the same properties with regards to indirect modification and RCs as, say, attributive adjectives? Moreover, a better understanding of the alleged non-intersective adjectives in Kunbarlang (cf. discussion of -barrkidbe above) is crucial for supporting such an analysis (admittedly though, for any alternative analysis as well).

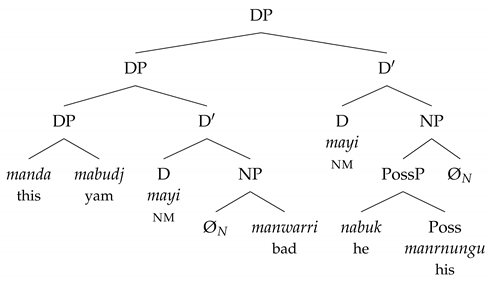

The other possibility is inspired by the DP-Predication analysis, advanced for Greek by Panagiotidis and Marinis (2011). Their proposal is that the specifier of a DP can host another nominal (an NP or a DP). In such a configuration, the complement of the larger DP is predicated of its specifier. This DP-predication can be repeated recursively. That is, a DP with a filled specifier can itself reside in a specifier of a larger DP. Since this analysis is somewhat more idiosyncratic than the RRC one, let me briefly illustrate it for example (28) above with a tree representation in (34).

- (34)

What this intends is that there is a DP comprising Dmayi nabuk manrnungu and a DP in its specifier, with the latter hosting the DP manda mabudj in its own specifier. The predication works in the opposite way or inside out. The deepest embedded DP, manda mabudj ‘this yam’, is the ‘ultimate subject’: its sister D (mayi manwarri ‘bad one’) is the predicate. The sister of the resulting DP, i.e., the D mayi nabuk manrnungu ‘his one’ is the predicate of that. This account is very economical in offering a direct interpretation of the structure built, without reliance on derivations (such as raising from RRC). Note also two other things: the speaker’s comment about this example, as cited in (28), was ‘These yams, it’s belong to him, it’s no good, he’s always giving us.’ This seems to match very well to the proposed predication intution, thus giving it indirect support (however, this is compatible with the RRC approach as well). The other is that, although in such Kunbarlang structures the noun is free to come in different places, it tends to occur in the first DP. Again, this seems to align with the idea that it is the ‘subject-most’ of all DPs, the others being predicated of it.

This kind of approach also raises a number of questions. The nature of the predication relation in this configuration is not entirely clear: while for RCs that is an independently established property, here it might appear stipulated, as this is not a common property of DPs (but see suggestions in Panagiotidis and Marinis 2011, §4). Next, there seems to be a complication with regards to the composition of the definite article, the noun, and the restrictive modifier. Partee (1973) shows that, for restrictive modification, the noun must combine with the modifier before combining with the article. In the DP-predication model, however, a full DP (in the specifier) is the predicate. By way of remark: notice that in terms of syntactic headedness the rightmost of the DPs heads the entire complex structure. Partly due to this fact, this approach relies crucially on using null noun heads in elliptical DPs. By letting the nouns share coreferential indexing, these Ø allow to capture the intuition that semantically, the entire DP describes a certain mabudj ‘yam’.

Finally, an interesting question arises for Kunbarlang with respect to the order (NM–)A–NM–N: is it always the result of displacement of the adjective, or can it be base-generated in a specifier of a DP on the DP-predication view? A definitive answer requires further work, but at present, I hypothesise that such orders always arise due to displacement. That is because of the respective semantic nature of nouns and adjectives: the former are primarily referential, whereas the latter are more predicative. Thus, placing an adjective as the subject of a noun predicate would be rather unnatural. Correspondingly, there are no examples in the corpus that favour such an analysis. However, this is not entirely unimaginable; hence, the hypothesis needs further testing.

5.2. General Discussion

Information structure is traditionally thought of as a phenomenon at the clausal level (Lambrecht 1994), but recently several proposals emerged suggesting that IS is also operational at the DP level (in particular, in DP literature, which is largely driven by the hypothesis about CP–DP parallelism; see Bernstein 2001b for the earliest proposal that I am aware of). The present study contributes to the growing body of evidence for IS-syntax at the level of nominal constituents. An important difference, however, is that on the provisional analysis in Section 3.3, IS is not a structural feature of the Kunbarlang DP but is executed by free merge of a functional head F with the nominal expression, triggering displacement. A complete analysis must also take demonstratives and determining personal pronouns into account, and thus is a matter for future work.

For the typology of grammaticalised adnominal D-elements (Himmelmann 1997, ch. 5), Kunbarlang noun marker thus presents an interesting case of an article intermediate between phrasal articles (Phrasenartikel) and linkers (Gelenkartikel). Similar to the former, they can occur at the edge of the single nominal constituent and, in that case, convey definiteness. Similar to the latter, they can occur between two nominal constituents, in which case definiteness is not relevant anymore (that is, unless this linear position is a by-product of adjective fronting, cf. Section 3.1). This seems to resemble D-elements in Paiwan (Himmelmann 1997, pp. 164–65), which are polyfunctional as linkers and specific articles—an interesting parallel to be explored further.

Finally, the data presented here are relevant for the typology and theory of determiner spreading. As is very clear from the detailed investigation in (Alexiadou 2014), the phenomena subsumed under this label are too diverse to warrant a single uniting theory of DS. However, I tried to show in Section 5.1 that Kunbarlang data stimulate a critical perspective on the existing approaches. Specifically, Kunbarlang provides a case which is sufficiently similar to Greek yet adds variation concerning non-adjectival modifiers (viz. possessors and quantifiers) and the pronounced information-structural effects of linear order rearrangement.

6. Conclusions

This paper advances our understanding of the workings of the noun phrase in Kunbarlang, which at first sight may appear unordered but, upon closer inspection, betrays a principled hierarchical structure. More specifically, our investigation focuses on two principal domains: functioning of definite articles/linkers (noun markers) and attributive modification (mainly adjectives, but consideration has also been given to quantifiers, possessors, and relative clauses). In both domains, (very local) ordering effects play a crucial role, giving rise to the overarching architecture of the Kunbarlang NP.

The following picture of Kunbarlang attributive modification reveals itself. Direct modification of nouns is possible in very limited amounts. More specifically, direct adjectival modification is possible, but one iteration of it renders the resulting NP immune to further direct modification. It is an intriguing question why this should be so. There is, however, a strategy to overcome that limitation, which consists in compulsory indirect modification, i.e., repetition of the noun marker with all (or almost all) constituents of the NP. The nature of the observed restrictions, however, presents an important question about the architecture of attributive modification, both in Kunbarlang and generally, and remains a topic for further research.

An investigation of these issues is important as an advancement in description of Gunwinyguan languages and insofar as it informs current research in linguistic theory and typology, including nonconfigurationality and typology of NP structure in Australian languages, typology of determiner spreading, expression of information structure at the noun phrase level, and typology of determiner systems. Hopefully, this research will serve as a step towards a fuller understanding and an explicit analysis of the NP in Kunbarlang and related languages.

Funding

The author’s data collection was supported by ARC CoEDL (Project ID: CE140100041).

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study (University of Melbourne Ethics ID 1544291.1).

Data Availability Statement

Recordings of the format IK1-YYMMDD_XXXN are archived with PARADISEC, see Kapitonov (2016). Recordings of the format YYYYMMDD IB NN (e.g., 20060901IB03) and YYYYMMDD IOv NN (e.g., 20150413IOv01) are made by Isabel O’Keeffe. Recordings 20150212AS01 and 20150206AS03 are made by Aung Si. These are archived with ELAR, see O’Keeffe et al. (2017), or http://hdl.handle.net/2196/00-0000-0000-0002-EF13-E@view and http://hdl.handle.net/2196/00-0000-0000-000F-BF4E-0@view (both accessed on 17 June 2021). The recording RS1-140 is made by Ruth Singer and archived with ELAR at http://hdl.handle.net/2196/00-0000-0000-0013-7C8C-A@view (accessed on 17 June 2021).

Acknowledgments

Thank you to Kunbarlang people, who so generously shared their language with me. I am very grateful to Mary Laughren for inspiring me to explore the structure of the Kunbarlang noun phrase deeper than I have had previously. Ruth Singer and Pavel Rudnev gave me very helpful feedback on an earlier draft. Four anonymous reviewers made numerous insightful suggestions leading to serious improvements of the paper. I am also grateful to the audiences of colloquia at Bamberg and Melbourne for the discussion, especially to Nikolaus Himmelmann and Dana Louagie. Finally, I wish to thank the editors of this Special Issue and, in particular, Jane Simpson for her valuable comments.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Abbreviations

| Notation | Description |

| 1 | first person |

| 2 | second person |

| 3 | third person |

| BEN | benefactive |

| CONJ | conjunction |

| DAT | dative |

| DEF | definite |

| DEM | demonstrative |

| DS | determiner spreading |

| DU | dual |

| EXCL | exclusive |

| F | feminine |

| FUT | future |

| GEN | i |

| HITH | hither |

| I | class I |

| IGNOR | ignorative |

| II | class II |

| III | class III |

| INCL | inclusive |

| INCP | incomplete |

| INDF | indefinite |

| IRR | irrealis |

| IV | class IV |

| LNK | linker |

| LOC | locative |

| LOC | locative |

| MED | medial |

| NEG | negative |

| NF | non-future |

| NM | noun marker |

| NOM | nominative |

| NP | non-past |

| OBJ | object |

| PL | plural |

| PRED | predicative |

| PROX | proximal |

| PST | past |

| RDP | reduplication |

| REFL | reflexive |

| SBJV | subjunctive |

| SG | singular |

Notes

| 1 | Some D-quantifiers are an exception, in that they do not inflect for noun class. |

| 2 | I follow the terminological practice here whereby nominal expression is used in a pretheoretical sense for any grouping of coreferential nominals under a single intonation contour, whereas noun phrase (NP), determiner phrase (DP), and adjective phrase (AP) are used in reference to constituents projected by respective heads. The best evidence for these nominal constituents is from case marking (see below) as well as the NP-internal ordering considerations, in particular the matters treated in this paper. Coreferential but linearly separate nominal expressions also exist in Kunbarlang and typically involve pause/pitch reset and right dislocation but do not correlate with presence/absence of noun markers (see Kapitonov 2021, §4.4.4; §7.1.3 ). Here, I only deal with contiguous nominal expressions. |

| 3 | For a recent overview of nonconfigurationality in Australian languages, see Nordlinger (2014, §6), and for a comprehensive typology of the noun phrase in Australia, see Louagie (2020). |

| 4 | In Baker’s theory of polysynthesis as a macroparameter deriving from the morphological condition on thematic role-assigning heads, the presence of gender marking on nouns is connected to the absence of articles in a language and to broader displacement possibilities, which contribute to surface manifestations of nonconfigurationality (Baker 1996, ch. 6). Superficially, it seems that the (near-)absence of such marking on the Kunbarlang nouns is in line with its having a definite article and its more configurational NP (both compared to the clause level and to the other Gunwinyguan languages). A proper evaluation of such a connection, however, would only be possible within a fuller analysis of the Kunbarlang syntax in terms of Baker’s model. |

| 5 | Cf. also Dixon (2002, p. 66), who stated it more categorically as a complete absence of articles. |

| 6 | These determiners are also found in pairwise combinations (Kapitonov 2021, pp. 108–9). All three possibilities are attested, although, impressionistically, the NM combines with demonstratives and pronouns more often than those two do with each other. Their ordering is pronoun > demonstrative > NM, where > is ‘precedes’. |

| 7 | For one, it appears that plural construal is a significant factor. Since this is not a hard-and-fast effect, however, I refrain from speculations until a larger-scale analysis. |

| 8 | The ‘DP-hypothesis’ explores the functional structure parallels within nominal and clausal domains (see Bernstein 2001a for an overview). I use it here rather as a convenience label, as it is has become a de facto standard in the GB/Minimalist noun phrase literature. However, it remains to be seen if the DP hypothesis provides the best account for the Kunbarlang data, especially in light of the broader conceptual difficulties it faces (Bruening 2009) or whether an NP analysis can be advanced, with determining elements as dependents and not heads of nominal expressions. |

| 9 | A reviewer wondered if the demonstrative nginda and the noun marker nayi in (11) function as copulas. They do not; copulas are zero in both clauses here. Ngalngarridj is topicalised, nginda is the subject of the first clause. In the second clause, nayi is part of the nominal predicate. On copulas in Kunbarlang see (Kapitonov 2021, §7.7). |

| 10 | Notice that adjectives borrowed from English do not show any special placement: when not emphatic, they occur after the noun. Indeed, in the same recording, we find Kinj-kali djarrang nayi quiet one (2sg.fut.-get.np horse nm.I quiet one) ‘Get a quiet horse’ [23:54]. Valuable diachronic evidence is found in (Kinslow Harris’s 1969) tagmemic sketch grammar of Kunbarlang, as she did field work in 1965–66 with consultants who did not speak English. She cites very few examples but explicitly states that both prenominal and postnominal adjectives are frequently attested (e.g., pp. 24–25). |

| 11 | The distinction between direct and indirect modification is a direct allusion to that of Sproat and Shih (1987), for whom it roughly corresponds to compounding vs. relative clause—yet an allusion only. Their work offers very valuable insight, a systematic testing of which is yet to be completed for Kunbarlang, so at present their technical distinction cannot be applied to Kunbarlang with certainty. See Section 5 for further discussion. |

| 12 | This example also contains a demonstrative. It is chosen for its brevity, and the discussed definiteness effect is found in the absence of the demonstrative just as well. |

| 13 | A standard test would be the impossibility of examples such as The table is another. |

| 14 | As to the question of what are those single instances of -barrkidbe and -rleng: the former is in an elliptical NP (so probably NM––A), and the latter is in a completely unclear example, probably a self-correction. |

| 15 | Demonstratives are not modifiers in the sense intended here. Cf. Himmelmann (1997, p. 13), who classifies demonstratives (together with quantifiers!) as operators, taking cue from Rijkhoff (1992). |

| 16 | I am grateful to Aung Si for his help with identification of the species. |

References

- Alexiadou, Artemis. 2014. Multiple Determiners and the Structure of DPs. Number 211 in Linguistik Aktuell. Amsterdam: John Benjamins Publishing Company. [Google Scholar]

- Alexiadou, Artemis, and Chris Wilder. 1998. Adjectival modification and multiple determiners. In Possessors, Predicates and Movement in the DP. Edited by Artemis Alexiadou and Chris Wilder. Number 22 in Linguistik Aktuell. Amsterdam: John Benjamins, pp. 303–32. [Google Scholar]

- Baker, Brett. 2008. The interpretation of complex nominal expressions in Southeast Arnhem Land languages. In Discourse and Grammar in Australian Languages. Edited by Ilana Mushin and Brett Baker. Number 104 in Studies in Language Companion. Amsterdam: John Benjamins, pp. 135–66. [Google Scholar]

- Baker, Mark C. 1996. The Polysynthesis Parameter. Oxford: Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Bernstein, Judy B. 2001a. The DP hypothesis: Identifying clausal properties in the nominal domain. In The Handbook of Contemporary Syntactic Theory. Edited by Mark Baltin and Chris Collins. Oxford: Blackwell, pp. 536–61. [Google Scholar]

- Bernstein, Judy B. 2001b. Focusing the “right” way in Romance determiner phrases. Probus 13: 1–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blake, Barry J. 1983. Structure and word order in Kalkatungu: The anatomy of a flat language. Australian Journal of Linguistics 3: 143–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Borer, Hagit. 2005. Structuring Sense. vol. 1: In Name Only. Oxford: Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Bowern, Claire. 2012. A Grammar of Bardi. Berlin: de Gruyter Mouton. [Google Scholar]

- Bruening, Benjamin. 2009. Selectional asymmetries between CP and DP suggest that the DP Hypothesis is wrong. In University of Pennsylvania Working Papers in Linguistics. Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania. [Google Scholar]

- Buchholz, Oda, and Wilfried Fiedler. 1987. Albanische Grammatik. Leipzig: Verlag Enzyklopädie. [Google Scholar]

- Cinque, Guglielmo. 2005. Deriving Greenberg’s Universal 20 and its exceptions. Linguistic Inquiry 36: 315–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coleman, Carolyn. n.d. Key Ideas: Kun-Barlang Word Grammar. Ms.

- Coleman, Carolyn. 2010. Kun-Barlang—English Dictionary. Unpublished Draft. [Google Scholar]

- Davidse, Kristin, and Tine Breban. 2019. A cognitive-functional approach to the order of adjectives in the English noun phrase. Linguistics 57: 327–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Dixon, Robert M. W. 2002. Australian Languages: Their Nature and Development. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Erteschik-Shir, Nomi. 2007. Information Structure. Oxford: Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Evans, Nicholas. 2003. Bininj Gun-Wok: A Pandialectal Grammar of Mayali, Kunwinjku and Kune. Canberra: Pacific Linguistics. [Google Scholar]

- Forrester, Katerina. 2015. The Internal Structure of the Mawng Noun Phrase. Honours thesis, University of Melbourne, Melbourne, Australia. [Google Scholar]

- Hale, Kenneth. 1983. Warlpiri and the grammar of non-configurational languages. Natural Language and Linguistic Theory 1: 5–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heath, Jeffrey. 1986. Syntactic and lexical aspects of nonconfigurationality in Nunggubuyu (Australia). Natural Language and Linguistic Theory 4: 375–408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heim, Irene. 1982. The Semantics of Definite and Indefinite Noun Phrases. Ph.D. thesis, University of Massachusetts, Amherst, MA, USA. [Google Scholar]

- Heycock, Caroline, and Roberto Zamparelli. 2005. Friends and colleagues: Plurality, coordination, and the structure of DP. Natural Language Semantics 13: 201–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Himmelmann, Nikolaus P. 1997. Deiktikon, Artikel, Nominalphrase: Zur Emergenz syntaktischer Struktur. Tübingen: Max Niemeyer Verlag. [Google Scholar]

- Himmelmann, Nikolaus P. 2001. Articles. In Language Typology and Language Universals. Edited by Martin Haspelmath, Ekkehard König, Wulf Oesterreicher and Wolfgang Raible. Berlin: de Gruyter, pp. 831–41. [Google Scholar]

- Ihsane, Tabea, and Geneveva Puskás. 2001. Specific is not Definite. Generative Grammar in Geneva 2: 39–54. [Google Scholar]

- Kapitonov, Ivan. 2016. Kunbarlang, central Arnhem Land. Collection IK1 at catalog.paradisec.org.au [Open Access]. Available online: https://catalog.paradisec.org.au/collections/IK1 (accessed on 17 June 2021).

- Kapitonov, Ivan. 2021. A Grammar of Kunbarlang. Number 89 in Mouton Grammar Library. Berlin: de Gruyter. [Google Scholar]

- Kinslow Harris, Joy. 1969. Preliminary grammar of Gunbalang. In Papers in Australian linguistics No. 4. Edited by Joy Kinslow Harris, Stephen A. Wurm and Donald C. Laycock. Number 17 in Pacific Linguistics, Series A; Canberra: Linguistic Circle of Canberra, pp. 1–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lambrecht, Knud. 1994. Information Structure and Sentence Form. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Laughren, Mary. 1984. Some focus strategies in Warlpiri. Paper presented to the Annual Meeting of the ALS, Alice Springs, 30 August–2 September. [Google Scholar]

- Lee, Jennifer. 1987. Tiwi Today: A Study of Language Change in a Contact Situation. Canberra: ANU. [Google Scholar]

- Louagie, Dana. 2020. Noun Phrases in Australian Languages. Number 662 in Pacific Linguistics. Berlin: de Gruyter. [Google Scholar]

- Mallinson, Graham, and Barry J. Blake. 1981. Language Typology: Cross-linguistic Studies in Syntax. Amsterdam: North-Holland Publishing Company. [Google Scholar]

- Nordlinger, Rachel. 2014. Constituency and grammatical relations in Australian languages. In The Languages and Linguistics of Australia. Edited by Harold Koch and Rachel Nordlinger. Berlin/Boston: Walter de Gruyter GmbH, chp. 5. pp. 215–61. [Google Scholar]

- O’Keeffe, Isabel, Carolyn Coleman, Ruth Singer, Aung Si, Linda Barwick, Janet Mardbinda, and Talena Wilton. 2017. Comprehensive Pan-Varietal, Ethnobiological, Anthropological Record of Kun-Barlang. SOAS ELAR ID: MDP0322. Available online: https://elar.soas.ac.uk/Collection/MPI1032014 (accessed on 17 June 2021).