Adult New Speakers of Welsh: Accent, Pronunciation and Language Experience in South Wales

Abstract

1. Introduction

1.1. The Welsh Context

1.2. Sounding ‘Native’

1.3. Sounding ‘Welsh’

1.4. Interactions between New and Traditional Speakers

1.5. The Present Study

2. Method

2.1. Participants

2.2. The Questionnaire

2.3. Analysis

3. Results

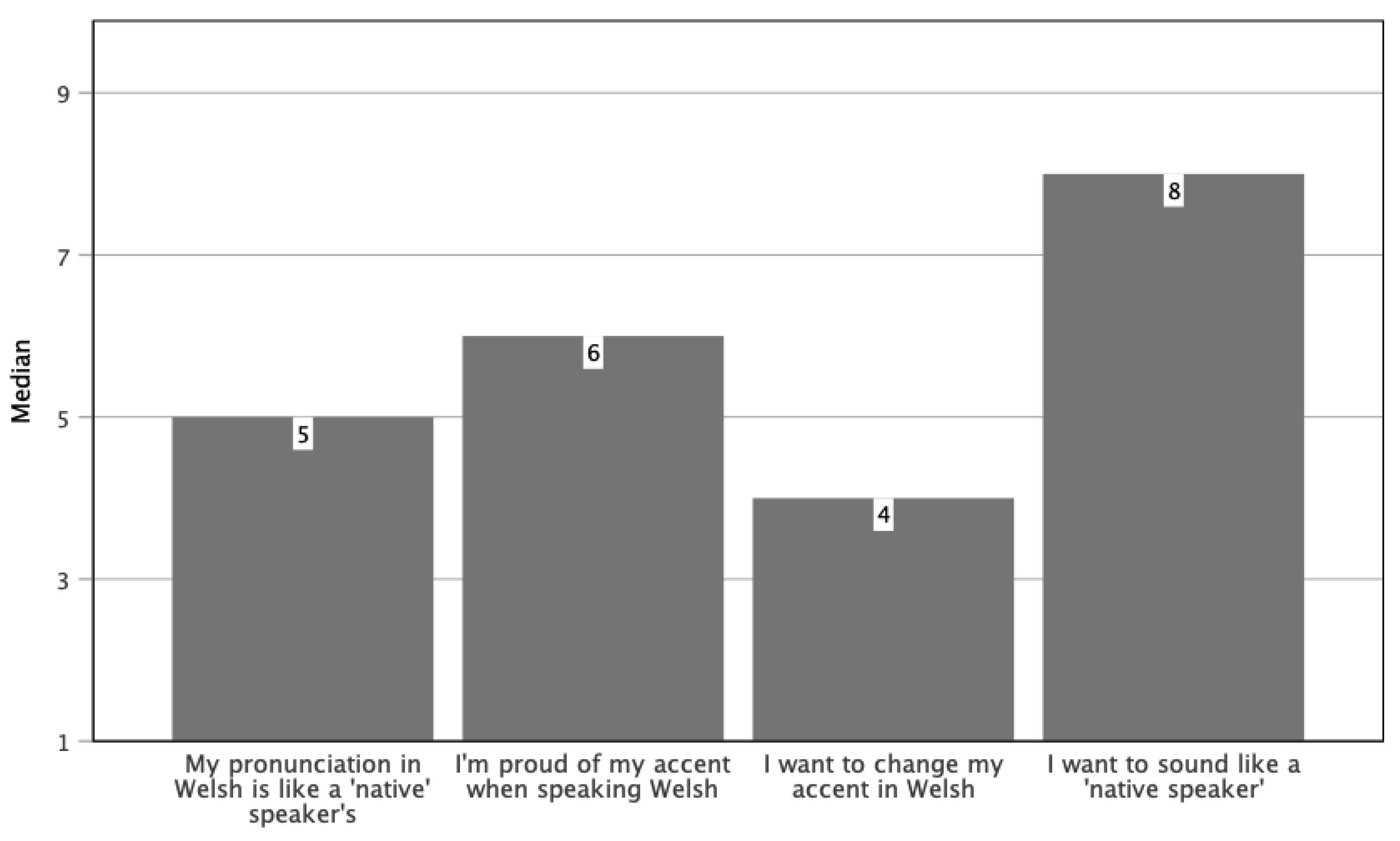

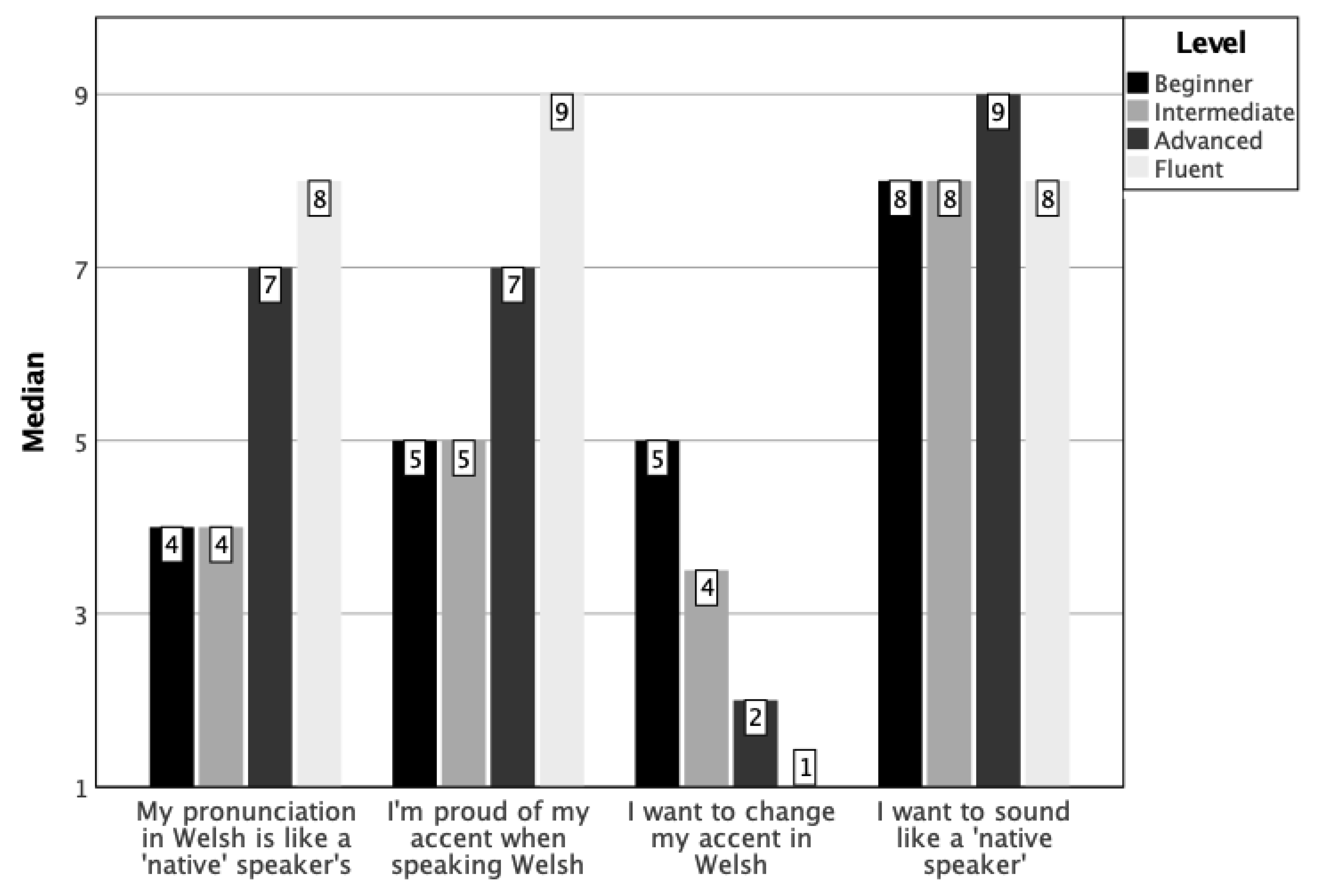

3.1. Accent and Pronunciation

- My pronunciation in Welsh is like a ‘native’ speaker’s.

- I’m proud of my accent when speaking Welsh.

- I want to change my accent in Welsh.

- I want to sound like a ‘native speaker’.

3.1.1. My Pronunciation in Welsh Is Like a ‘Native’ Speaker’s

3.1.2. I’m Proud of My Accent When Speaking Welsh

3.1.3. I Want to Change My Accent in Welsh

3.1.4. I Want to Sound Like a ‘Native Speaker’

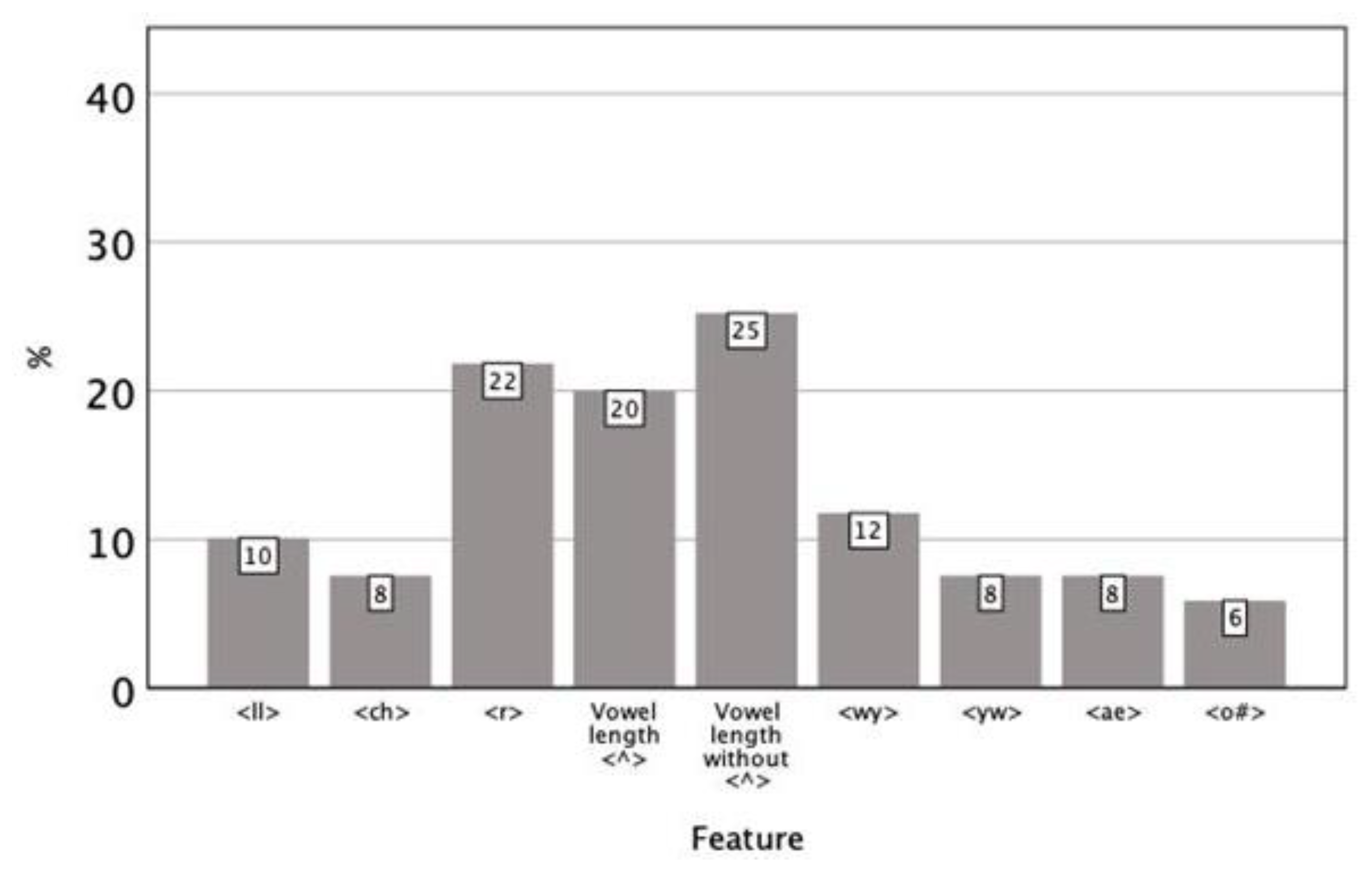

3.2. Questions About Specific Speech Sounds

3.3. Responses of Traditional ‘Native’ Speakers

4. Discussion

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

| I ba raddau mae’r datganiadau isod yn wir i chi? | To What Extent Are the Following Statements True for You 1 = Ddim o gwbl/Not at all 9 = Yn llwyr/Completely | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | |

| Mae fy ynganiad wrth siarad Cymraeg yr un peth â siaradwyr ‘brodorol’ | My pronunciation in Welsh is like a ‘native’ speaker’s | □ | □ | □ | □ | □ | □ | □ | □ | □ |

| Rydw i’n falch o fy acen wrth siarad Cymraeg | I’m proud of my accent when speaking Welsh | □ | □ | □ | □ | □ | □ | □ | □ | □ |

| Rydw i eisiau newid fy acen yn Gymraeg | I want to change my accent in Welsh | □ | □ | □ | □ | □ | □ | □ | □ | □ |

| Rydw i eisiau swnio fel ‘siaradwr brodorol’ | I want to sound like a ‘native speaker | □ | □ | □ | □ | □ | □ | □ | □ | □ |

| Pa mor heriol ydi’r rhain i unigolion sy’n dysgu Cymraeg? | How Challenging Are the Following for Individuals Learning Welsh? | |

|---|---|

| Heriol i fi/Challenging for me | |

| Ynganu/pronouncing ‘ll’ e.e. lle, pell | □ |

| Ynganu/pronouncing ‘ch’ e.e. chi, cwch | □ |

| Rolio/rolling ‘r’ e.e. oren, dŵr | □ |

| Ynganu ‘o’ ar ddiwedd geiriau/pronouncing ‘o’ at the end of words e.e. nofio, eto | □ |

| Ynganu/pronouncing ‘ae’ e.e. mae | □ |

| Ynganu/pronouncing ‘wy’ e.e. mwy | □ |

| Ynganu/pronouncing ‘yw’ e.e. byw | □ |

| Gwahaniaethu rhwng llafariaid hir a byr gyda to bach/Distinguishing between long and short vowels with a circumflex e.e. tân/tan | □ |

| Gwahaniaethu rhwng llafariaid hir a byr heb do bach/Distinguishing between long and short vowels without a circumflex e.e. bys/byr | □ |

| Sut mae siaradwyr ‘brodorol’ yn ymateb i’ch acen/ynganiad? | How Do ‘Native’ Speakers React to Your Accent/Pronunciation? | |

|---|---|

| Dydyn nhw ddim yn ymateb/They don’t react | □ |

| Mae nhw’n siarad yn arafach/They speak more slowly | □ |

| Mae nhw’n troi i’r Saesneg/They switch to English | □ |

| Mae nhw’n ‘cywirio’/They ‘correct’ me | □ |

| Arall/Other | □ |

| Os dewisoch chi Arall, rhowch fanylion os gwelwch yn dda | If other, please give details: | |

Appendix B

| Factor | Coef | S.E. | Wald | p-Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| [LikeNative = 1] | −4.925 | 0.862 | 32.683 | <0.001 |

| [LikeNative = 2] | −4.166 | 0.843 | 24.446 | <0.001 |

| [LikeNative = 3] | −3.203 | 0.830 | 14.902 | <0.001 |

| [LikeNative = 4] | −2.833 | 0.826 | 11.747 | 0.001 |

| [LikeNative = 5] | −1.862 | 0.817 | 5.190 | 0.023 |

| [LikeNative = 6] | −1.477 | 0.812 | 3.307 | 0.069 |

| [LikeNative = 7] | −0.378 | 0.791 | 0.229 | 0.632 |

| [LikeNative = 8] | 1.549 | 0.775 | 3.997 | 0.046 |

| [Origin = Welsh] | 1.634 | 0.362 | 20.412 | <0.001 |

| [Level = Beginner] | −3.987 | 0.850 | 22.031 | <0.001 |

| [Level = Intermediate] | −3.464 | 0.852 | 16.539 | <0.001 |

| [Level = Advanced] | −2.284 | 0.880 | 6.730 | 0.009 |

| Factor | Coef | S.E. | Wald | p-Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| [ProudAccent = 1] | −3.652 | 0.796 | 21.052 | <0.001 |

| [ProudAccent = 2] | −3.259 | 0.778 | 17.559 | <0.001 |

| [ProudAccent = 3] | −2.209 | 0.752 | 8.641 | 0.003 |

| [ProudAccent = 4] | −1.900 | 0.747 | 6.462 | 0.011 |

| [ProudAccent = 5] | −1.066 | 0.740 | 2.074 | 0.150 |

| [ProudAccent = 6] | −0.559 | 0.737 | 0.575 | 0.448 |

| [ProudAccent = 7] | 0.227 | 0.734 | 0.096 | 0.757 |

| [ProudAccent = 8] | 1.227 | 0.740 | 2.751 | 0.097 |

| [Origin = Welsh] | 1.435 | 0.356 | 16.232 | <0.001 |

| [Level = Beginner] | −2.014 | 0.757 | 7.068 | 0.008 |

| [Level = Intermediate] | −2.015 | 0.771 | 6.824 | 0.009 |

| [Level = Advanced] | −0.757 | 0.821 | 0.848 | 0.357 |

| Factor | Coef | S.E. | Wald | p-Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| [ProudAccent = 1] | 0.018 | 0.838 | 0.000 | 0.983 |

| [ProudAccent = 2] | 0.714 | 0.842 | 0.718 | 0.397 |

| [ProudAccent = 3] | 1.077 | 0.845 | 1.625 | 0.202 |

| [ProudAccent = 4] | 1.588 | 0.849 | 3.497 | 0.061 |

| [ProudAccent = 5] | 2.311 | 0.857 | 7.266 | 0.007 |

| [ProudAccent = 6] | 2.630 | 0.862 | 9.298 | 0.002 |

| [ProudAccent = 7] | 3.297 | 0.8s79 | 14.074 | <0.001 |

| [ProudAccent = 8] | 3.568 | 0.889 | 16.117 | <0.001 |

| [Origin = Welsh] | −1.446 | 0.360 | 16.184 | <0.001 |

| [Level = Beginner] | 2.302 | 0.871 | 6.991 | 0.008 |

| [Level = Intermediate] | 1.831 | 0.879 | 4.340 | 0.037 |

| [Level = Advanced] | 1.420 | 0.935 | 2.306 | 0.129 |

| Factor | Coef | S.E. | Wald | p-Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| [ProudAccent = 1] | −3.391 | 0.861 | 15.513 | <0.001 |

| [ProudAccent = 2] | −2.964 | 0.811 | 13.355 | <0.001 |

| [ProudAccent = 3] | −2.526 | 0.776 | 10.597 | <0.001 |

| [ProudAccent = 4] | −2.207 | 0.758 | 8.479 | 0.004 |

| [ProudAccent = 5] | −1.031 | 0.724 | 2.029 | 0.154 |

| [ProudAccent = 6] | −0.648 | 0.719 | 0.812 | 0.368 |

| [ProudAccent = 7] | −0.452 | 0.718 | 0.396 | 0.529 |

| [ProudAccent = 8] | 0.224 | 0.717 | 0.098 | 0.755 |

| [Origin = Welsh] | −0.227 | 0.348 | 0.425 | 0.514 |

| [Level = Beginner] | 0.017 | 0.731 | 0.001 | 0.982 |

| [Level = Intermediate] | −0.238 | 0.747 | 0.101 | 0.750 |

| [Level = Advanced] | 0.735 | 0.826 | 0.791 | 0.374 |

References

- Andrews, Hunydd. 2011. Llais y Dysgwr: Profiadau Oedolion Sydd Yn Dysgu Cymraeg Yng Ngogledd Cymru. Gwerddon 9: 37–58. [Google Scholar]

- Awbery, Gwen. 2009. Welsh. In The Celtic Languages, 2nd ed. Edited by Martin J. Ball and Nicole Müller. London: Routledge, pp. 359–426. [Google Scholar]

- Baayen, Harald. 2008. Analyzing Linguistic Data: A Practical Introduction to Statistics Using R. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Baker, Colin, Hunydd Andrews, Ifor Gruffydd, and Gwyn Lewis. 2011. Adult Language Learning: A Survey of Welsh for Adults in the Context of Language Planning. Evaluation & Research in Education 24: 41–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ball, Martin J., and Glyn E. Jones. 1984. Welsh Phonology: Selected Readings. Cardiff: University of Wales Press. [Google Scholar]

- Ball, Martin J., and Briony Williams. 2001. Welsh Phonetics. Lampeter: Edwin Mellen Press. [Google Scholar]

- Best, Catherine. 1995. A Direct Realist View of Crosslanugage Speech Perception. In Speech Perception and Linguistic Experience: Issues in Cross-Language Research. Edited by W. Strange. Timonium: York Press, pp. 171–204. [Google Scholar]

- Best, Catherine. T., and Michael. D. Tyler. 2007. Non-Native and Second Language Speech Perception: Commonalities and Complementarities. In Language Experience in Second Language Learning: In Honour of James Emil Flege. Edited by Ocke-Schwen Bohn and Murray J. Munro. Amsterdam: John Benjamins, pp. 13–34. [Google Scholar]

- Birdsong, David. 2003. Authenticité de prononciation en français L2 chez des apprenants tardifs anglophones: Analyses segmentales et globales. Acquisition et Interaction en Langue Étrangère 18: 17–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bucholtz, Mary. 2003. Sociolinguistic nostalgia and the authentication of identity. Journal of Sociolinguistics 7: 398–416. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Derwing, Tracey M., and Murray J. Munro. 2015. Pronunciation Fundamentals: Evidence-Based Perspectives for L2 Teaching and Research. Amsterdam: John Benjamins. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Endresen, Anna, and Laura A. Janda. 2016. Five statistical models for Likert-type experimental data on acceptability judgments. Journal of Research Design and Statistics in Linguistics and Communication Science 3: 217–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Escudero, Paola. 2005. Linguistic Perception and Second Language Acquisition: Explaining the Attainment of Optimal Phonological Categorization. LOT Dissertation Series 113; Utrecht: Utrecht University. [Google Scholar]

- Escudero, Paola, and Paul Boersma. 2004. Bridging the Gap between L2 Speech Perception Research and Phonological Theory. Studies in Second Language Acquisition 26: 551–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Escudero, Paola, and Daniel Williams. 2012. Native dialect influences second-language vowel perception: Peruvian versus Iberian Spanish learners of Dutch. The Journal of the Acoustical Society of America 131: 406–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Flege, James. 1995. Second Language Speech Learning: Theory, Findings and Problems. In Speech Perception and Linguistic Experience: Issues in Cross-Language Research. Edited by W. Strange. Timonium: York Press, pp. 229–73. [Google Scholar]

- Fynes-Clinton, Osbert Henry. 1913. The Welsh Vocabulary of the Bangor District. Oxford: Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Gnevsheva, Ksenia. 2017. Within-speaker variation in passing for a native speaker. International Journal of Bilingualism 21: 213–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hannahs, S. J. 2013. The Phonology of Welsh. Oxford: Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Hewitt, Steve. 2020. The Problem of Neo-Speakers in Language Revitalization: The Example of Breton. Paper presented at FEL24: Teaching and Learning Resources for Endangered Languages, UCL, London, UK, September 23–25. [Google Scholar]

- Hodges, Rhian Siân. 2010. Tua’r Goleuni: Rhesymau Rhieni Dros Ddewis Addysg Gymraeg i’w Plant Yng Nghwm Rhymni. Gwerddon 6: 9–33. [Google Scholar]

- Hornsby, Michael. 2015a. Revitalizing Minority Languages: New Speakers of Breton, Yiddish and Lemko. London: Palgrave Macmillan. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hornsby, Michael. 2015b. The “New” and “Traditional” Speaker Dichotomy: Bridging the Gap. International Journal of the Sociology of Language 231: 107–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hornsby, Michael. 2019. Positions and Stances in the Hierarchization of Breton Speakerhood. Journal of Multilingual and Multicultural Development 40: 392–403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hornsby, Michael, and Dick Vigers. 2018. “New” Speakers in the Heartlands: Struggles for Speaker Legitimacy in Wales. Journal of Multilingual and Multicultural Development 39: 419–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jaffe, Alexandra. 2013. Minority Language Learning and Communicative Competence: Models of Identity and Participation in Corsican Adult Language Courses. Language & Communication 33: 450–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jenkins, Jennifer. 2002. A Sociolinguistically Based, Empirically Researched Pronunciation Syllabus for English as an International Language. Applied Linguistics 23: 83–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jonsson, Carla, and Mona Rosenfors. 2017. “I Have Struggled Really Hard to Learn Sami”: Claiming and Regaining a Minority Language. International Journal of the Sociology of Language 248: 49–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mac Giolla Chríost, Diarmait, Partick Carlin, Sioned Davies, Tess Fitzpatrick, Anys Prys Jones, Rachel Heath-Davies, and Jennifer Marshall. 2012. Welsh for Adults Teaching and Learning Approaches, Methodologies and Resources: A Comprehensive Research Study and Critical Review of the Way Forward. Cardiff: Welsh Government. [Google Scholar]

- Mayr, Robert, and Hannah Davies. 2011. A Cross-Dialectal Acoustic Study of the Monophthongs and Diphthongs of Welsh. Journal of the International Phonetic Association 41: 1–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mayr, Robert, Jonathan Morris, Ineke Mennen, and Daniel Williams. 2017. Disentangling the effects of long-term language contact and individual bilingualism: The case of monophthongs in Welsh and English. International Journal of Bilingualism 21: 245–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McEwan-Fujita, Emily. 2010. Ideology, Affect, and Socialization in Language Shift and Revitalization: The Experiences of Adults Learning Gaelic in the Western Isles of Scotland. Language in Society 39: 27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McLeod, Wilson, and Bernadette O’Rourke. 2015. “New speakers” of Gaelic: Perceptions of linguistic authenticity and appropriateness. Applied Linguistics Review 6: 151–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McLeod, Wilson, Bernadette O’Rourke, and Stuart Dunmore. 2014. New Speakers of Gaelic in Edinburgh and Glasgow. Soillse: The National Research Network for the Maintenance and Revitalisaton of Gaelic Language and Culture. [Google Scholar]

- Mennen, Ineke, Niamh Kelly, Robert Mayr, and Jonathan Morris. 2020. The Effects of Home Language and Bilingualism on the Realization of Lexical Stress in Welsh and Welsh English. Frontiers in Psychology 10: 3038. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mitterer, Holger, Nikola Anna Eger, and Eva Reinisch. 2020. My English Sounds Better than Yours: Second-Language Learners Perceive Their Own Accent as Better than That of Their Peers. PLoS ONE 15: e0227643. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morris, Jonathan. 2013. Sociolinguistic Variation and Regional Minority Language Bilingualism: An Investigation of Welsh-English Bilinguals in North Wales. Manchester: University of Manchester. [Google Scholar]

- Morris-Jones, John, W. J. Gruffydd, T. Gwynn Jones, J. Lloyd-Jones, T. H. Parry-Williams, Ifor Williams, Robert Williams, and Henry Lewis. 1928. Orgraff yr Iaith Gymraeg. Caerdydd: Gwasg Prifysgol Cymru. [Google Scholar]

- Müller, Nicole, and Martin. J. Ball. 1999. Examining the Acquisition of Welsh Phonology in L1 English Learners. Journal of Celtic Language Learning 4: 16–32. [Google Scholar]

- Nance, Claire, Wilson McLeod, Bernadette O’Rourke, and Stuart Dunmore. 2016. Identity, Accent Aim, and Motivation in Second Language Users: New Scottish Gaelic Speakers’ Use of Phonetic Variation. Journal of Sociolinguistics 20: 164–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- National Centre for Learning Welsh. 2020. Statistics 2018–2019′. Available online: https://learnwelsh.cymru/about-us/statistics-2018-19/ (accessed on 3 March 2021).

- O’Rourke, Bernadette, and Joan Pujolar. 2013. From Native Speakers to “New Speakers”-Problematizing Nativeness in Language Revitalization Contexts. Histoire Epistemologie Langage 35: 47–67. [Google Scholar]

- Robert, Elen. 2009. Accommodating “new” speakers? An attitudinal investigation of L2 speakers of Welsh in south-east Wales. International Journal of the Sociology of Language 195: 93–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rees, Iwan Wyn, and Jonathan Morris. 2018. Astudiaeth o Ganfyddiadau Tiwtoriaid Cymraeg i Oedolion o Anawsterau Ynganu Ymhlith Dysgwyr Yr Iaith. Gwerddon 27: 39–66. [Google Scholar]

- Selleck, Charlotte. 2018. We’re Not Fully Welsh: Hierarchies of Belonging and ‘New’ Speakers of Welsh. In New Speakers of Minority Languages: Linguistic Ideologies and Practices. Edited by Cassie Smith-Christmas, Noel P. Ó. Murchadha, Michael Hornsby and Máiréad Moriaty. London: Palgrave Macmillan, pp. 45–65. [Google Scholar]

- Trosset, Carol S. 1986. The Social Identity of Welsh Learners. Language in Society 15: 165–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tyler, Michael D. 2019. PAM-L2 and phonological category acquisition in the foreign language classroom. In A Sound Approach to Language Matters—In Honor of Ocke-Schwen Bohn. Edited by Anne Mette Nyvad, Michaela Hejná, Anders Højen, Anna Bothe Jespersen and Mette Hjortshøj Sørensen. Aarhus: Aarhus University, pp. 607–30. [Google Scholar]

- Van Leussen, Jan-Willem, and Paola Escudero. 2015. Learning to Perceive and Recognize a Second Language: The L2LP Model Revised. Frontiers in Psychology 6: 1000. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Watkins, T. Arwyn. 1961. Ieithyddiaeth. Caerdydd: Gwasg Prifysgol Cymru. [Google Scholar]

- Watkins, Colin. 2020. 2020 Duolingo Language Report: United Kingdom. Duolingo Blog. December 15. Available online: https://blog.duolingo.com/uk-language-report-2020/ (accessed on 3 March 2021).

- Welsh Government. 2011. Welsh Speakers by Local Authority, Gender and Detailed Age Groups, 2011 Census. Cardiff: Welsh Government. Available online: https://statswales.gov.wales/Catalogue/Welsh-Language/Census-Welsh-Language/welshspeakers-by-localauthority-gender-detailedagegroups-2011census (accessed on 1 March 2021).

- Welsh Government. 2017. Cymraeg 2050: A Million Welsh Speakers. Cardiff: Welsh Government. [Google Scholar]

| Northern Welsh | Southern Welsh | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Short vowels | Long vowels | Short vowels | Long vowels |

| i ɨ u | iː ɨː uː | ɪ ʊ | iː uː |

| e ə o | eː oː | ɛ ə ɔ | eː oː |

| a | aː | a | aː |

| 13 diphthongs | 8 diphthongs | ||

| Front closing | Back closing | Front closing | Back closing |

| aɪ ɔɪ eɪ | ɪʊ ɛʊ aʊ əʊ ɨʊ | aɪ ɔɪ ʊɪ eɪ | ɪʊ ɛʊ aʊ əʊ |

| Central closing aɨ ɑɨ ɔɨ ʊɨ əɨ | |||

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Williams, M.; Cooper, S. Adult New Speakers of Welsh: Accent, Pronunciation and Language Experience in South Wales. Languages 2021, 6, 86. https://doi.org/10.3390/languages6020086

Williams M, Cooper S. Adult New Speakers of Welsh: Accent, Pronunciation and Language Experience in South Wales. Languages. 2021; 6(2):86. https://doi.org/10.3390/languages6020086

Chicago/Turabian StyleWilliams, Meinir, and Sarah Cooper. 2021. "Adult New Speakers of Welsh: Accent, Pronunciation and Language Experience in South Wales" Languages 6, no. 2: 86. https://doi.org/10.3390/languages6020086

APA StyleWilliams, M., & Cooper, S. (2021). Adult New Speakers of Welsh: Accent, Pronunciation and Language Experience in South Wales. Languages, 6(2), 86. https://doi.org/10.3390/languages6020086