Where Are the Goalposts? Generational Change in the Use of Grammatical Gender in Irish

Abstract

1. Introduction

1.1. Interaction of Input, Experience and Formal Complexity

1.2. Language Contact and Change in Indigenous Minority Languages

1.3. Irish: Rapid Sociolinguistic Changes

1.4. Grammatical Gender as an Area of Tension between Irish and English

1.4.1. Gender Marking Following the Definite Article

| 1. | a. | Teach ‘house’ (masc.) | → | an teach ‘the house’ (Det N masc.) |

| b. | Máthair ‘mother’ (fem.) | → | an mháthair ‘the mother’ (Det N fem.-lenited) |

| 2. | a. | Sionnach ‘fox’ (masc.) | → | an sionnach ‘the fox’ (Det N masc.) |

| b. | Srón ‘nose’ (fem.) | → | an tsrón ‘the nose’ (Det N fem.-/t-/prefixed) |

| 3. | a. | Asal ‘donkey’ (masc.) | → | an t-asal ‘the donkey’ (Det N masc.-/t-/prefixed) |

| b. | Ubh ‘egg’ (fem.) | → | an ubh ‘the egg’ (Det N fem.) |

1.4.2. Noun Adjective Agreement

| 4. | a. | Teach ‘house’ (masc.) + bán ‘white’ | → | an teach bán ‘the white house’ (Det N (masc.) Adj) |

| b. | Máthair ‘mother’ (fem.) + deas ‘nice’ | → | an mháthair dheas ‘the nice mother’ (Det N (fem.) Adj-lenited) |

1.4.3. Third-Person Possession

| 5. | a. | Seán (masc.) + cóta (coat) | → | a chóta (masc possessive + N-lenited) ‘his coat’ |

| b. | Máire (fem.) + cóta (coat) | → | a cóta (fem possessive + N) ‘her coat’ |

| 5. | a. | anam ‘soul’ + Seán (Nom. Masc.) | → | a anam (masc-possessive + N) ‘his soul’ |

| b. | anam + Máire (Nom. Fem.) | → | a h-anam (fem-poss + N-/h-/prefixed) ‘her soul’ |

1.5. Aims of the Research

2. Sample, Measures and Methods

2.1. Child Participants

2.2. Adult Participants

2.3. Measures

- E-MIM Subtest 1: Grammatical gender following the definite article (28 items)

- E-MIM Subtest 2: Noun–adjective combinations (32 items)

- E-MIM Subtest 3: Third-person possession (28 items)

2.4. Procedure

2.4.1. Scoring

2.4.2. Ethical Approval

3. Results

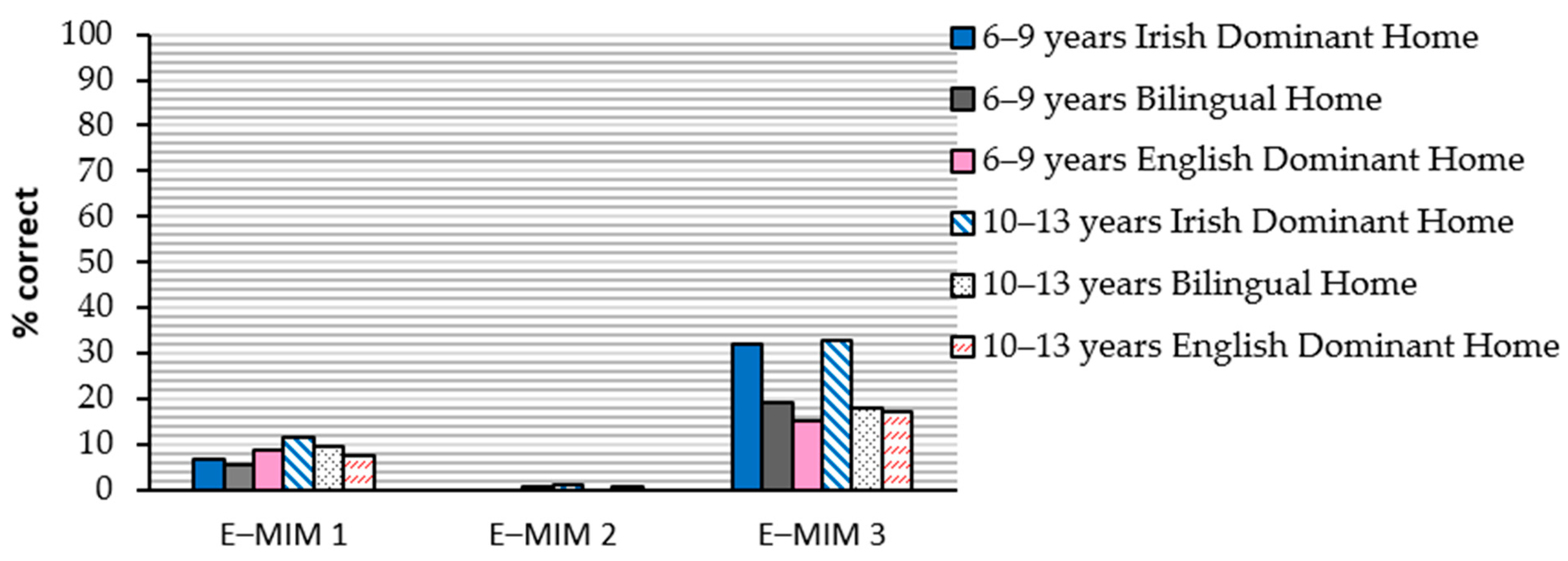

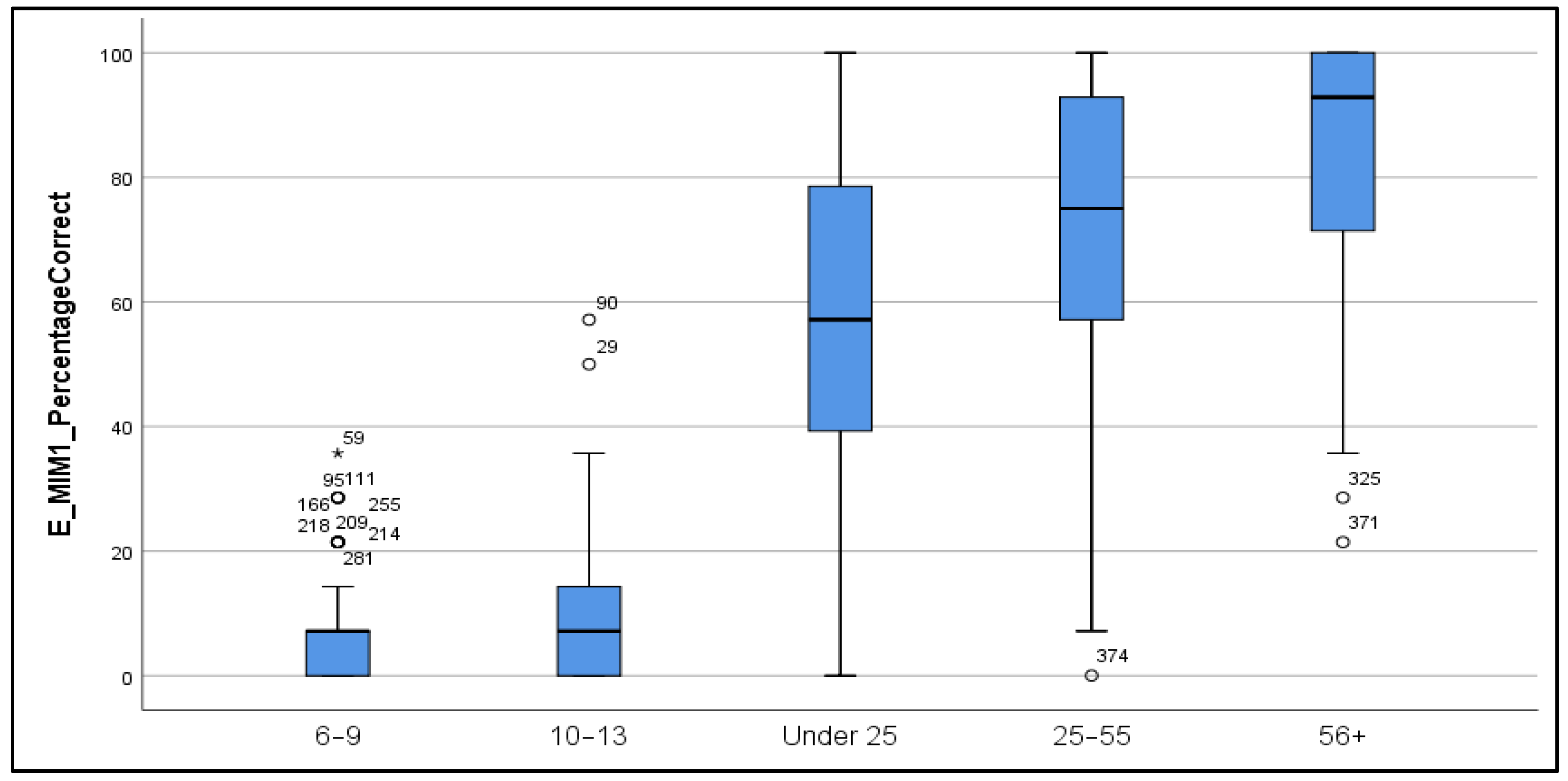

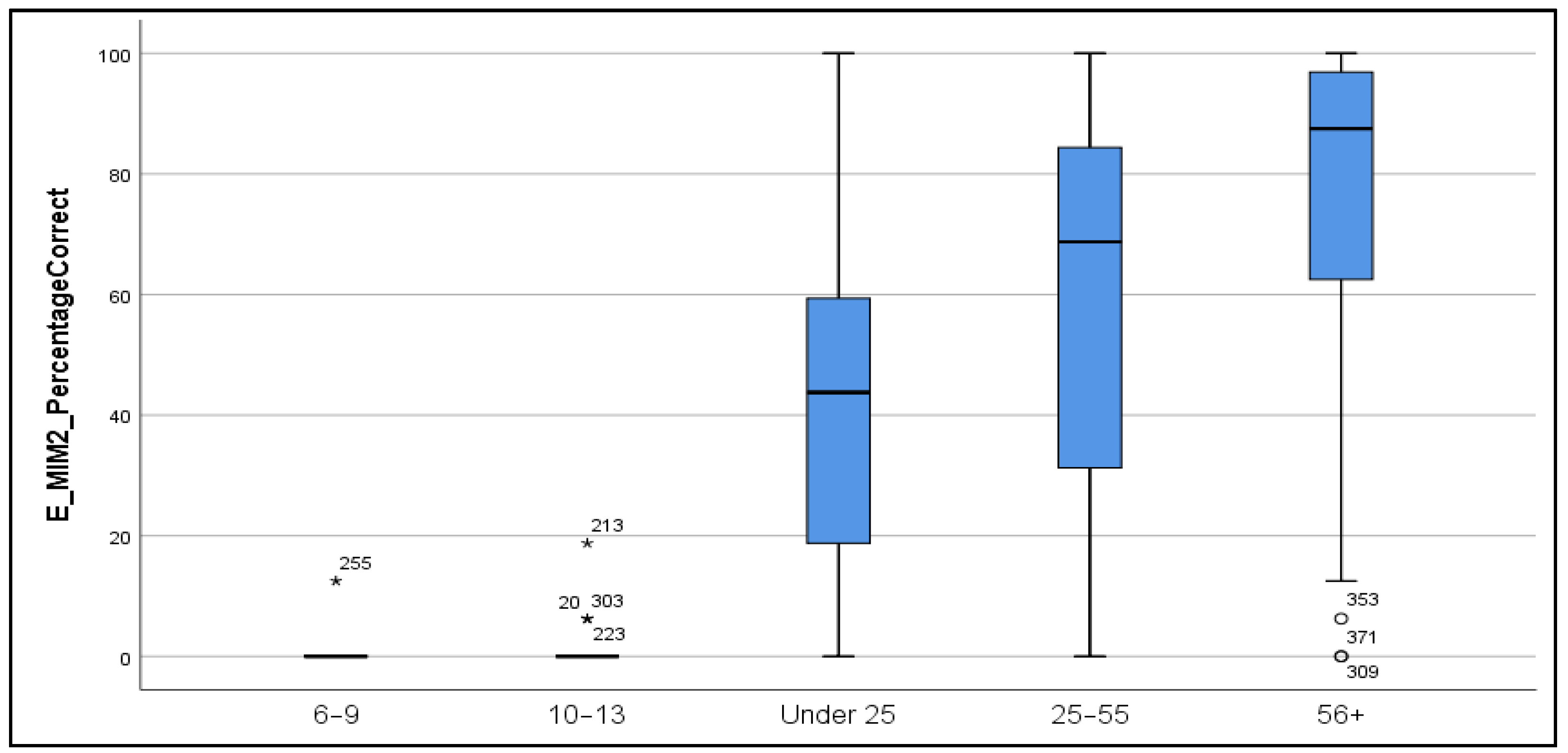

3.1. Irish Grammatical Gender Marking among Child Participants

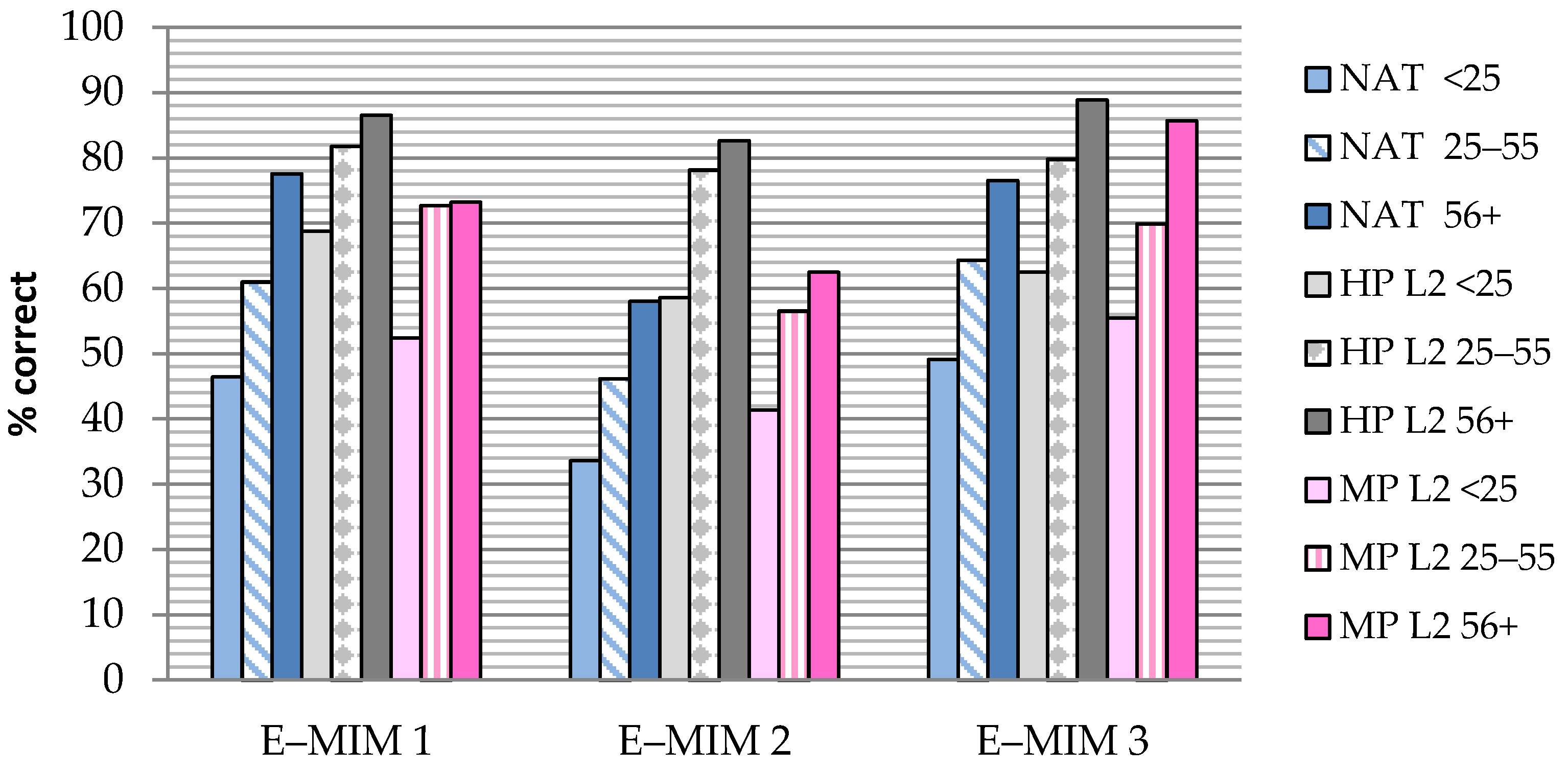

3.2. Irish Productive Grammatical Gender Marking by Adult Participants

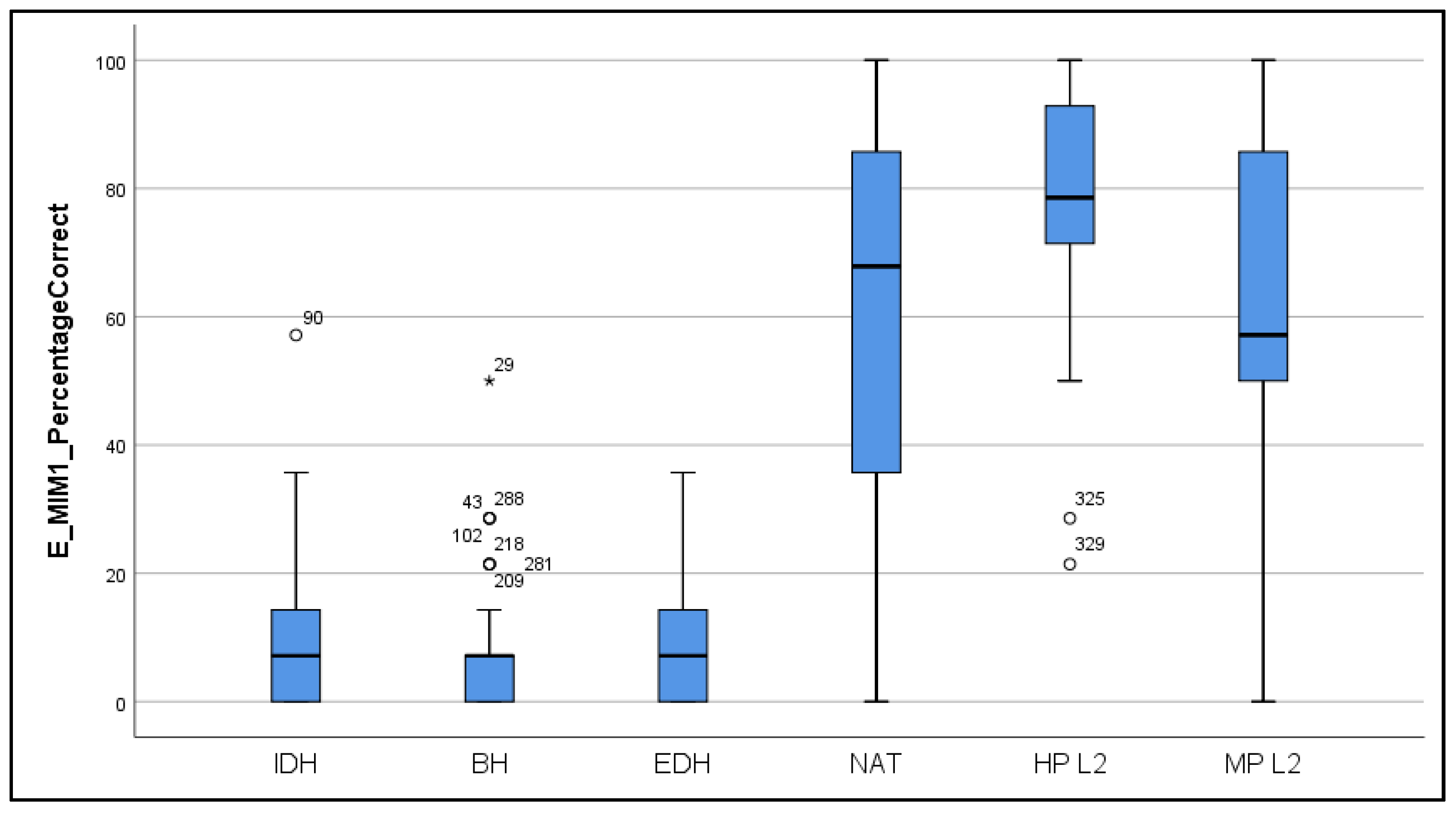

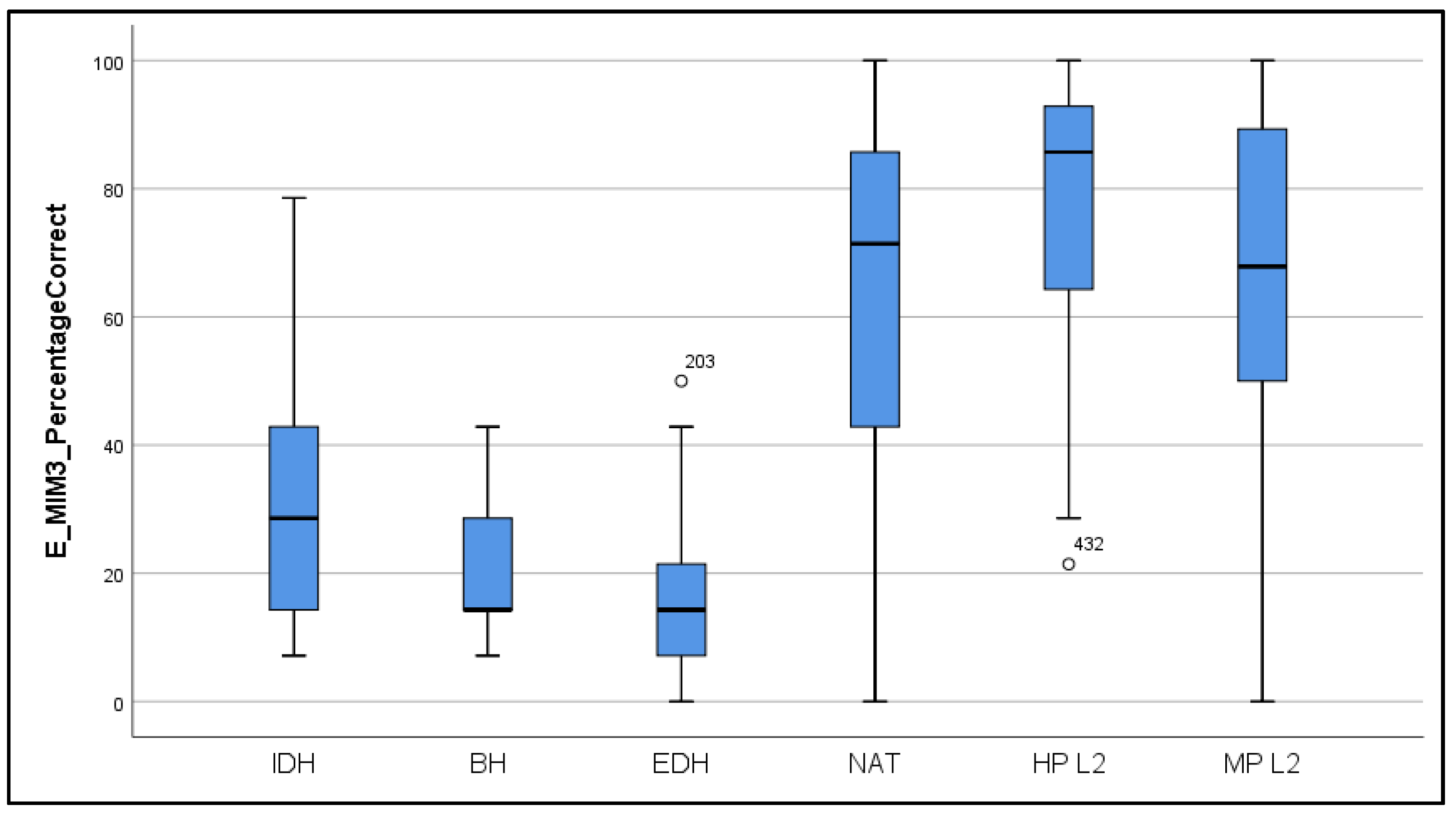

3.3. Comparing the Results from the Adult and Child Participants

4. Discussion

4.1. The Impact of Input Accuracy on Child Acquisition

4.2. Language Environment: Change in Irish across Generations

4.3. Implications: Need for Intensive Support for Mother-Tongue Irish Speakers

4.4. Future Research

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A. E-MIM Practice Items Subtests 1–3

- Subtest 1 Practice items

- Participant is shown a picture of a bed.

- Researcher says: “Chonaic Marcas an leaba.” [Marcas saw the bed.]

- Researcher says: “Céard faoin gceann seo?” [What about this one?]

- Participant is shown a picture of a hand.

- Participant says: “Chonaic Marcas an lámh.” [Marcas saw the hand.]

- Subtest 2 Practice items

- Participant is shown a picture of a grey cat.

- Researcher says: “Chonaic Marcas an cat liath.” [Marcas saw the grey cat.]

- Researcher says: “Céard faoin gceann seo?” [What about this one?]

- Participant is shown a picture of an orange lamp.

- Participant says: “Chonaic Marcas an lampa oráiste.” [Marcas saw the orange lamp.]

- Subtest 3 Practice items

- Participant is shown a picture of a girl and a stuffed toy.

- Researcher says: Dearfaidh mise “Áine agus teidí” agus is féidir leat “is maith liom a teidí”, nó “ní maith liom a teidí” a rá.” [I’ll say ‘this is Áine’, and you can say ‘I like her teddy’ or ‘I don’t like her teddy’.]

- Researcher says: “Céard faoin gceann seo? Tógálaí agus teach.” [What about this one? Builder and house.]

- Participant is shown a picture of a builder holding a model house.

- Participant says: “Seo tógálaí, is maith liom a theach.” [This is a builder, I like his house.]

Appendix B

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 | 11 | 12 | 13 | 14 | 15 | 16 | 17 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Child Background | |||||||||||||||||

| 2. Parent Background | 0.74 ** | ||||||||||||||||

| 3. Teacher Background | 0.03 | 0.08 | |||||||||||||||

| 4. Age | −0.23 ** | −0.20 ** | 0.04 | ||||||||||||||

| 5. SES | −0.09 | −0.03 | −0.11 | −0.14 * | |||||||||||||

| 6. % Irish-Dominant pupils in School | 0.62 ** | 0.63 ** | 0.04 | −0.33 ** | 0.23 ** | ||||||||||||

| 7. School Model | 0.44 ** | 0.47 ** | 0.54 ** | −0.22 ** | −0.11 | 0.63 ** | |||||||||||

| 8. Non-Verbal IQ | −0.11 | −0.15 * | 0.01 | 0.28 ** | −0.16 ** | −0.29 ** | −0.08 | ||||||||||

| 9. Irish Vocab | 0.31 ** | 0.21 ** | 0.17 ** | −0.1 | −0.18 ** | 0.19 ** | 0.30 ** | 0.20 ** | |||||||||

| 10. English Vocab | −0.08 | −0.09 | −0.04 | −0.14 * | 0.29 ** | −0.12 * | −0.12 * | 0.30 ** | 0.47 ** | ||||||||

| 11. R-MIM 1 | 0.03 | −0.04 | −0.07 | 0.05 | 0.04 | 0.00 | −0.03 | 0.13 * | 0.08 | 0.07 | |||||||

| 12. R-MIM 2 | 0.05 | 0.03 | −0.11 | 0.05 | −0.06 | 0.01 | 0.02 | 0.01 | 0.05 | −0.04 | 0.06 | ||||||

| 13. R-MIM 3 | 0.05 | 0.01 | 0.09 | 0.27 ** | 0.12 * | −0.01 | 0.09 | 0.20 ** | 0.29 ** | 0.15 * | 0.03 | −0.06 | |||||

| 14. R-MIM 4 | 0.13 * | 0.09 | 0.00 | −0.05 | −0.01 | 0.23 ** | 0.22 ** | 0.00 | 0.11 | −0.04 | 0.10 | 0.11 | 0.06 | ||||

| 15. R-MIM 5 | 0.16 ** | 0.14 * | 0.03 | −0.034 | −0.04 | 0.04 | 0.06 | 0.00 | 0.07 | 0.00 | 0.06 | 0.15 * | −0.05 | −0.03 | |||

| 16. E-MIM 1 | 0.03 | −0.01 | 0.08 | 0.09 | 0.01 | −0.04 | 0.02 | 0.11 | 0.16 * | 0.17 * | 0.06 | −0.04 | 0.24 ** | −0.08 | 0.09 | ||

| 17. E-MIM 2 | 0.03 | −0.01 | 0.07 | −0.03 | −0.07 | 0.08 | 0.01 | 0.01 | −0.01 | 0.01 | 0.03 | 0.06 | 0.00 | 0.06 | 0.10 | 0.28 ** | |

| 18. E-MIM 3 | 0.44 ** | 0.35 ** | −0.06 | −0.20 ** | 0.06 | 0.3 ** | 0.15 * | −0.07 | 0.3 ** | 0.19 ** | 0.05 | 0.00 | 0.18 ** | 0.01 | 0.13 | 0.34 ** | 0.24 ** |

References

- Antonijevic, Stanislava, Sarah-Ann Muckley, and Nicole Müller. 2020. The role of consistency in use of morphosyntactic forms in child-directed speech in the acquisition of Irish, a minority language undergoing rapid language change. Journal of Child Language 47: 267–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Antonijevic-Elliott, Stanislava, Rena Lyons, Mary Pat O’ Malley, Natalia Meir, Ewa Haman, Natalia Banasik, Clare Carroll, Ruth McMenamin, Margaret Rodden, and Yvonne Fitzmaurice Lyons. 2020. Language assessment of monolingual and multilingual children using non-word and sentence repetition tasks. Clinical Linguistics & Phonetics 34: 293–311. [Google Scholar]

- Bialystok, Ellen. 2020. Bilingual effects on cognition in children. In Oxford Research Encyclopedia of Education. Oxford: Oxford University Press. Available online: https://oxfordre.com/education/view/10.1093/acrefore/9780190264093.001.0001/acrefore-9780190264093-e-962 (accessed on 1 December 2020).

- Cameron-Faulkner, Thea, and Tina M. Hickey. 2011. Form and function in Irish child directed speech. Cognitive Linguistics 22: 569–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carroll, Susanne E. 2017. Exposure and input in bilingual development. Bilingualism: Language and Cognition 20: 37–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Central Statistics Office. 2017. Census 2016. The Irish Language. Available online: http://www.cso.ie/en/media/csoie/releasespublications/documents/population/2017/7_The_Irish_language.pdf (accessed on 1 December 2020).

- Department of Education and Skills. 2016. Policy on Gaeltacht Education 2017–2022. Available online: https://www.gov.ie/en/publication/5cfd73-policy-on-Gaeltacht-education-2017-2022/ (accessed on 1 February 2021).

- Dunn, Alexandra L., and Jean E. Fox Tree. 2009. A quick, gradient Bilingual Dominance Scale. Bilingualism: Language & Cognition 12: 273–89. [Google Scholar]

- Frenda, Alessio S. 2011. Gender in Irish between continuity and change. Folia Linguistica 45: 283–316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gaelscoileanna. 2019. Statistics. Online Document. Available online: https://gaeloideachas.ie/i-am-a-researcher/statistics/ (accessed on 2 December 2020).

- Gathercole, Virginia C. Mueller. 2007. Miami and North Wales, so far and yet so near: A constructivist account of morphosyntactic development in bilingual children. International Journal of Bilingual Education & Bilingualism 10: 224–47. [Google Scholar]

- Gathercole, Virginia C. Mueller. 2014. Bilingualism matters: One size does not fit all. International Journal of Behavioural Development 38: 359–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gathercole, Virginia C. Mueller. 2017. Straw man: Who thought exposure was the ONLY factor? Bilingualism: Language and Cognition 20: 23–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gathercole, Virginia C. Mueller, and Enlli Môn Thomas. 2009. Bilingual first-language development: Dominant language takeover, threatened minority language take-up. Bilingualism: Language & Cognition 12: 213–37. [Google Scholar]

- Gathercole, Virginia C. Mueller, Ivan Kennedy, and Enlli Môn Thomas. 2016. Socioeconomic level & bilinguals’ performance on language & cognitive measures. Bilingualism: Language & Cognition 19: 1057–78. [Google Scholar]

- Government of Ireland. 2010. 20 Year Strategy for the Irish Language 2010–2030. Available online: http://www.ahg.gov.ie/app/uploads/2015/07/20-Year-Strategy-English-version.pdf (accessed on 1 December 2020).

- Gruter, Theres, and Johanne Paradis. 2014. Input & Experience in Bilingual Development. Amsterdam: John Benjamins Publishing Company. [Google Scholar]

- Heller, Monica, and Marilyn Martin-Jones. 2001. Voices of Authority: Education & Linguistic Difference. Westport: Ablex Publishing. [Google Scholar]

- Hickey, Tina M. 1990. The acquisition of Irish: A study of word order development. Journal of Child Language 17: 17–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed][Green Version]

- Hickey, Tina M. 1991. Mean length of utterance & the acquisition of Irish. Journal of Child Language 18: 553–69. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Hickey, Tina M. 1999. Parents & early immersion: Reciprocity between home & immersion preschool. The International Journal of Bilingual Education & Bilingualism 2: 94–113. [Google Scholar]

- Hickey, Tina M. 2001. Mixing beginners & native speakers in Irish immersion: Who is immersing whom? Canadian Modern Language Review 57: 443–74. [Google Scholar]

- Hickey, Tina M. 2007. Children’s language networks in minority language immersion: What goes in man not come out. Language & Education 21: 46–65. [Google Scholar]

- Hickey, Tina M. 2012. ILARSP: A grammatical profile of Irish. In The Languages of LARSP. Edited by Martin J. Ball, David Crystal and Paul Fletcher. Clevedon: Multilingual Matters, pp. 149–66. [Google Scholar]

- Jones, M. C. 1998. Language Obsolescence and Revitalization: Linguistic Change in Two Sociolinguistically Contrasting Welsh Communities. Oxford: Oxord University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Lenoach, Ciarán. 2014. Sealbhú Neamhiomlán na Gaeilge mar Chéad Teanga sa Dátheangachas Dealaitheach [Incomplete Acquisition of Irish as a First Language in Subtractive Bilingualism]. Doctoral Dissertation, Ollscoil na hÉireann, Gaillimh, Ireland. [Google Scholar]

- Lieven, Elena, and Michael Tomasello. 2008. Children’s first language acquisition from a usage-based perspective. In Handbook of Cognitive Linguistics and Second Language Acquisition. Edited by Peter Robinson and Nick C. Ellis. London: Routledge, pp. 168–96. [Google Scholar]

- Montanari, Elke. 2014. Grammatical gender in the discourse of multilingual children’s acquisition of German. Linguistik Online 64: 57–68. [Google Scholar]

- Montrul, Silvina. 2008. Incomplete Acquisition in Bilingualism: Re-Examining the Age Factor. Amsterdam: John Benjamins Publishing Company. [Google Scholar]

- Montrul, Silvina. 2016. The Acquisition of Heritage Languages. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Montrul, Silvina. 2018. Heritage language development: Connecting the dots. International Journal of Bilingualism 22: 530–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Montrul, Silvina, and Carmen Silva-Corvalán. 2019. The social context contributes to the incomplete acquisition of aspects of heritage languages. Studies in Second Language Acquisition 41: 269–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Montrul, Silvina, and Kim Potowski. 2007. Command of gender agreement in school-age Spanish-English bilingual children. International Journal of Bilingualism 11: 301–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Montrul, Silvina, and Noelia Sánchez-Walker. 2013. Differential object marking in child and adult Spanish heritage speakers. Language Acquisition 20: 109–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Montrul, Silvina, and Rebecca Foote. 2014. Age of acquisition interactions in bilingual lexical access: A study of the weaker language of L2 learners & heritage speakers. International Journal of Bilingualism 18: 274–303. [Google Scholar]

- Muckley, Sarah-Ann. 2016. Language Assessment of Native Irish Speaking Children: Towards Developing Diagnostic Testing for Speech and Language Therapy Practice. Doctoral Dissertation, National University of Ireland, Galway, Ireland. [Google Scholar]

- Müller, Nicole, Sarah-Ann Muckley, and Stanislava Antonijevic-Elliott. 2018. Where phonology meets morphology in the context of rapid language change and universal bilingualism: Irish initial mutations in child language. Clinical Linguistics and Phonetics 33: 3–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mutu, Margaret. 2005. In search of the missing Māori links: Maintaining both ethnic identity and linguistic integrity in the revitalization of the Māori language. International Journal of the Sociology of Language 172: 117–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nance, Claire. 2013. Phonetic Variation, Sound Change, & Identity in Scottish Gaelic. Doctoral Dissertation, University of Glasgow, Glasgow, UK. [Google Scholar]

- Nic Fhlannchadha, Siobhán. 2016. Investigating the later stages of Irish acquisition [Iniúchadh ar shealbhú níos déanaí na Gaeilge]. Doctoral Dissertation, University College Dublin, Dublin, Ireland. [Google Scholar]

- Nic Fhlannchadha, Siobhán, and Tina M. Hickey. 2017. Acquiring an opaque gender system in Irish, an endangered indigenous language. First Language 37: 475–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nic Fhlannchadha, Siobhán, and Tina M. Hickey. 2018. Minority language ownership and authority: Perspectives of native speakers and new speakers. International Journal of Bilingual Education and Bilingualism 21: 38–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nic Fhlannchadha, Siobhán, and Tina M. Hickey. 2019. Assessing children’s proficiency in a minority language: Exploring the relationships between home language exposure, test performance and teacher and parent ratings of school-age Irish-English bilinguals. Language and Education 33: 340–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ní Dhiorbháin, Aisling. 2014. Bain Súp As! Treoir nua Maidir le Múineadh na Gramadaí [Give It a Go! A New Direction in the Teaching of Grammar]. Dublin: COGG. [Google Scholar]

- Ní Thuairisg, Laoise, and Pádraig Ó Duibhir. 2019. Teacht in Inmhe. Baile Átha Cliath: Lárionad Taighde DCU um Fhoghlaim agus Teagasc na Gaeilge. [Google Scholar]

- Nic Pháidín, Caoilfhionn. 2003. Cén fáth nach?’-Ó chanúint go críól. In Idir Lúibíní. Edited by Róisín Ní Mhianáin. Dublin: Cois Life, pp. 113–30. [Google Scholar]

- Ó Catháin, Brian. 2016. The Irish language in present-day Ireland. In Sociolinguistics in Ireland. Edited by Raymond Hickey. London: Palgrave, pp. 41–59. [Google Scholar]

- Ó Duibhir, Pádraig. 2011. “I thought that we had good Irish”: Irish immersion students’ insights into their target language use. In Immersion Education: Practices, Policies, Possibilities. Edited by Diana J. Tedick, Donna Christian and Tara W. Fortune. Bristol: Multilingual Matters, pp. 145–65. [Google Scholar]

- Ó Duibhir, Pádraig. 2018. Immersion Education: Lessons from a Minority Language Context. Bristol: Multilingual Matters. [Google Scholar]

- Ó Giollagáin, Conchúr, and Martin Charlton. 2015. Nuashonrú ar an Staidéar Cuimsitheach Teangeolaíoch ar Úsáid na Gaeilge sa Ghaeltacht 2006–2011. [Update on the Comprehensive Linguistic Study on the Use of Irish in the Gaeltacht]. Maynooth: NUI Maynooth. [Google Scholar]

- Ó Giollagáin, Conchúr, Seosamh Mac Donnacha, Fiona Ní Chualáin, Aoife Ní Shéaghdha, and Mary O’Brien. 2007. Comprehensive Linguistic Study of the Use of Irish in the Gaeltacht: Complete Report. Report Prepared for the Department of Arts, Heritage and the Gaeltacht by Acadamh na hOllscolaíochta Gaeilge, NUIG, with Institiúid Náisiúnta um Anailís Réigiúnach agus Spásúil. Maynooth: NUI Maynooth. [Google Scholar]

- Ó hÉallaithe, Donncha. 2015. Anailís: Níl scéal na Gaeltachta chomh duairc is a Tuairiscítear sa Nuashonrú. [Analysis: The Story of the Gaeltacht Is Not as Grim as Is Reported in the New Report] Tuairisc. June 12. Available online: http://tuairisc.ie/anailis-nil-sceal-na-Gaeltachta-chomh-duairc-is-a-tuairiscitear-sa-nuashonru-o-heallaithe/ (accessed on 2 February 2021).

- Ó hIfearnáin, Tadhg. 2008. Raising children to be bilingual in the Gaeltacht: Language preference & practise. International Journal of Bilingual Education & Bilingualism 10: 510–28. [Google Scholar]

- Ó hIfearnáin, Tadhg. 2013. Family language policy, first language Irish speaker attitudes and community-based response to language shift. Journal of Multilingual and Multicultural Development 34: 348–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ó Murchadha, Noel. 2010. Standard, standardisation & assessments of standardness in Irish. Proceedings of the Harvard Celtic Colloquium 30: 207–35. [Google Scholar]

- Ó Murchadha, Noel. 2019. Is Furasta locht a Fháil ar Ghaeilgeoirí a Labhraíonn Béarla lena Bpáistí, ach ceist Chasta í [It Is Easy to Find Fault with Irish Speakers Who Speak English to Their Children, but It Is a Complex Issue] Tuairisc. January 29. Available online: https://tuairisc.ie/is-furasta-locht-a-fhail-ar-ghaeilgeoiri-a-labhraionn-bearla-lena-bpaisti-ach-ceist-chasta-i/ (accessed on 3 December 2020).

- Ó Murchadha, Noel, and Colin J. Flynn. 2018. Educators’ target language varieties for language learners: Orientation toward ‘native’ and ‘nonnative’ norms in a minority language context. The Modern Language Journal 102: 797–813. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ó Siadhail, Mícheál. 1989. Modern Irish: Grammatical Structure & Dialectal Variation. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- O’Rourke, Bernadette. 2011. Whose language is it? Struggles for language ownership in an Irish language classroom. Journal of Language, Identity & Education 10: 327–45. [Google Scholar]

- O’Rourke, Bernadette, and John Walsh. 2015. New speakers of Irish: Shifting boundaries across time and space. International Journal of the Sociology of Language 231: 63–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Rourke, Bernadette, and John Walsh. 2020. New Speakers of Irish in the Global Context: New Revival? Abingdon: Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- O’Toole, Ciara, and Tina M. Hickey. 2013. Diagnosing language impairment in bilinguals: Professional experience & perception. Child Language Teaching & Therapy 29: 91–109. [Google Scholar]

- O’Toole, Ciara, and Tina M. Hickey. 2016. Bilingual language acquisition in a minority context: Using the Irish-English Communicative Development Inventory to track acquisition of an endangered language. International Journal of Bilingual Education and Bilingualism 20: 146–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Otheguy, Ricardo. 2016. The linguistic competence of second-generation bilinguals: A critique of ‘incomplete acquisition’. Romance Linguistics 2013: Selected Papers from the 43rd Linguistic Symposium on Romance Languages (LSRL). [Google Scholar]

- Paradis, Johanne. 2011. The impact of input factors on bilingual development: Quantity versus quality. Linguistic Approaches to Bilingualism 1: 67–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paradis, Johanne, Kristyn Emmerzael, and Tamara Sorenson Duncan. 2010. Assessment of English language learners: Using parent report on first language development. Journal of Communication Disorders 43: 474–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Péterváry, Tamás, Brian Ó Curnáin, Conchúr Ó Giollagáin, and Jerome Sheahan. 2014. Analysis of Bilingual Competence: Language Acquisition among Young People in the Gaeltacht. Dublin: An Chomhairle um Oideachas Gaeltachta agus Gaelscolaíochta. [Google Scholar]

- Pires, Acrisio, and Jason Rothman. 2009. Disentangling sources of incomplete acquisition: An explanation for competence divergence across heritage grammars. International Journal of Bilingualism 13: 211–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rannóg an Aistriúchán. 1958. Gramadach na Gaeilge agus litriú na Gaeilge: An caighdeán oifigiúil [The Grammar and Spelling of Irish: The Official Standard] 1958. Dublin: Government of Ireland. [Google Scholar]

- Rodina, Yulia, and Marit Westergaard. 2017. Grammatical gender in bilingual Norwegian–Russian acquisition: The role of input and transparency. Bilingualism: Language and Cognition 20: 197–214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith-Christmas, Cassie, and Síleas L. NicLeòid. 2020. How to turn the tide: The policy implications emergent from comparing a ‘post-vernacular FLP’ to a ‘pro-Gaelic FLP’. Language Policy 19: 575–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith-Christmas, Cassie, Mari Bergroth, and Irem Bezcioğlu-Göktolga. 2019. A kind of success story: Family language policy in three different sociopolitical contexts. International Multilingual Research Journal 13: 88–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stenson, Nancy. 1981. Studies in Irish Syntax. Tubingen: Gunter Narr, vol. 8. [Google Scholar]

- Stenson, Nancy, and Tina M. Hickey. 2016. When regular is not easy: Cracking the code of Irish orthography. Writing Systems Research 8: 187–217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thomas, Enlli Mon, and Virginia C. Mueller Gathercole. 2007. Children’s productive command of grammatical gender & mutation in Welsh: An alternative to rule-based learning. First Language 27: 251–78. [Google Scholar]

- Thordardottir, Elin. 2014. The typical development of simultaneous bilinguals. In Input & Experience in Bilingual Development. Amsterdam: John Benjamins Publishing Company, pp. 141–60. [Google Scholar]

- Unsworth, Sharon. 2016. Quantity and quality of language input in bilingual language development. In Bilingualism across the Lifespan: Factors Moderating Language Proficiency. Edited by Elena Nicoladis and Simona Montanari. Washington, DC: American Psychological Association, pp. 103–21. [Google Scholar]

| 1 | |

| 2 | Three main dialects (varieties) of Irish exist: the Connemara dialect spoken in Galway and Mayo on the west coast, the Munster/Southern dialect spoken in Kerry and Cork in the south of the country and the Ulster/Northern dialect spoken in Donegal on the north-western coast (Ó Siadhail 1989). |

| 3 | Stenson (1981, p. 20): “a combination of case, gender, definiteness and number interact to determine whether or not an [initial] mutation takes place. For example, feminine nouns in the nominative singular are lenited after the definite article; they are not lenited if the definite article is absent. On the other hand, masculine nouns in the genitive singular are lenited after the definite article, but feminine genitives are not.” |

| 4 | It must be acknowledged that it is possible that some children, if cared for only by their parents in the home, may have periods of Irish dominance or even monolingualism at particular ages, provided their exposure to English media and English-speaking relatives and peers is limited. |

| Age | Irish-Dominant Home IDH | Bilingual Home BH | English-Dominant Home EDH | Total | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 6 | 1 | 0.3% | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0.3% | ||

| 7 | 13 | 4% | 14 | 4.5% | 6 | 2% | 33 | 11% |

| 8 | 25 | 8% | 18 | 6% | 12 | 4% | 55 | 18% |

| 9 | 21 | 7% | 21 | 7% | 37 | 12% | 79 | 26% |

| All 6–9 | 60 | 20% | 53 | 17.3% | 55 | 18% | 168 | 55% |

| 10 | 20 | 6.5% | 19 | 6.2% | 30 | 10% | 69 | 22.5% |

| 11 | 11 | 3.6% | 5 | 1.6% | 27 | 9% | 43 | 14% |

| 12 | 3 | 1% | 3 | 1% | 10 | 3% | 16 | 5% |

| 13 | 1 | 0.3% | 1 | 0.3% | 0 | 2 | 0.6% | |

| All 10–13 | 35 | 11% | 28 | 9% | 67 | 22% | 130 | 42% |

| Missing | 8 | 3% | ||||||

| Total | 95 | 31% | 81 | 26.5% | 122 | 40% | 306 | |

| Age | L1 Speakers | Highly Proficient L2 Speaker | Moderately Proficient L2 Speaker | Total | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| <25 | 9 | 6% | 10 | 8% | 21 | 15.5% | 40 | 30% |

| 25–55 | 28 | 21% | 21 | 15% | 25 | 18.5% | 74 | 55% |

| 56+ | 7 | 5% | 10 | 7% | 4 | 3% | 21 | 15% |

| Total | 44 | 32% | 41 | 30% | 50 | 37% | 135 | 100% |

| Unstandard. Beta | Standard. Beta | p | CI | Part Correlation | Tolerance | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Lower | Upper | ||||||

| Eng-Dom. Home | −15.64 | −0.475 | 0.001 ** | −22.75 | −8.54 | −0.241 | 0.256 |

| Bilingual Home | −14.38 | −0.395 | 0.001 ** | −20.31 | −8.56 | −0.265 | 0.451 |

| E-MIM Subtest 1 | 0.39 | 0.239 | 0.001 ** | 0.192 | 0.586 | 0.251 | 0.816 |

| Age | −1.99 | −0.174 | 0.008 ** | −3.45 | −0.537 | −0.150 | 0.738 |

| E-MIM Subtest 2 | 1.33 | 0.134 | 0.024 * | 0.178 | 2.48 | 0.126 | 0.887 |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Nic Fhlannchadha, S.; Hickey, T.M. Where Are the Goalposts? Generational Change in the Use of Grammatical Gender in Irish. Languages 2021, 6, 33. https://doi.org/10.3390/languages6010033

Nic Fhlannchadha S, Hickey TM. Where Are the Goalposts? Generational Change in the Use of Grammatical Gender in Irish. Languages. 2021; 6(1):33. https://doi.org/10.3390/languages6010033

Chicago/Turabian StyleNic Fhlannchadha, Siobhán, and Tina M. Hickey. 2021. "Where Are the Goalposts? Generational Change in the Use of Grammatical Gender in Irish" Languages 6, no. 1: 33. https://doi.org/10.3390/languages6010033

APA StyleNic Fhlannchadha, S., & Hickey, T. M. (2021). Where Are the Goalposts? Generational Change in the Use of Grammatical Gender in Irish. Languages, 6(1), 33. https://doi.org/10.3390/languages6010033