1. Introduction

To what extent are native and non-native grammars alike? Non-native learners face similar learning tasks as children: the problem of distributional learning of syntactic categories (where to place the forms) and the semantic mapping problem (what the configurations and forms mean). Adult learners must address these problems with reduced exposure, possibly past the age where their ability to make linguistic generalizations is optimal (

Hudson Kam and Newport 2005;

Schuler et al. 2016), while constantly referencing entrenched L1 representations. Some authors argue that adult learners sometimes fail to fully acquire novel underlying structures.

Earlier work suggests that second language (L2) speakers are limited to surface level learning. An absence of structural dependency is reported in the L2 literature on complex questions and relative clauses (

Cook 2006) and scrambling (

Hopp 2005).

Meisel (

2011) argues that L2 German speakers correctly assign verb-second V2 placement to finite verbs in matrix clauses, while using subject-verb-object SVO order in embedded clauses.

Meisel (

2011) interprets this performance as the result of rightward subject extraposition as opposed to target subject-object-verb (SOV) order with verb raising. He also notes that post-verbal nicht “no” is acquired prior to verbal inflection in L2 German, interpreting this as additional evidence for surface-level word order learning. Further evidence for structural insensitivity to negation comes from English-speaking learners of Spanish who allow the complex predicate formation that licenses clitic climbing over sentence negation (

Thomas 2011).

One response to these claims is to point to other sources of difficulty beyond syntactic structures. Difficulty with tense and agreement may reflect difficulties at morphological insertion (

Prévost and White 2000;

Slabakova 2016); interacting domains may tax processing resources (

Sorace 2011); and, an absence of clitic climbing may be prosodic, not syntactic (

de Garavito 2019). Psycholinguistic work with L2 populations focuses not on representations, but on parsing, proposing that non-native speakers tend to perform surface (shallow) parsing of complex structures (

Clahsen and Felser 2006,

2018).

Sagarra et al. (

2019) find effects of shallow parsing on semantic interpretation; non-native Spanish speakers interpret object-verb-subject (OVS) relative clauses as SVO and have more difficulty recovering from this analysis.

The last two decades of work have placed intense focus on the challenge of acquiring semantic properties in a second language (

Slabakova and Montrul 2003;

Slabakova 2006;

Guijarro-Fuentes 2012;

Cho and Slabakova 2014;

Sánchez Alvarado 2018;

Hopp et al. 2020; to name a few) and semantic learning is often used to assess claims of L2 syntax. We propose that adjective placement in Romance languages offers an important test of whether learners can acquire novel underlying structure. This domain involves learning the interface between a distributional problem (the variable placement of adjectives in Romance) and a mapping problem (how adjective scope is mapped onto word order).

In languages such as Spanish, adjective position is crucially linked to lexical class. Some adjectives are lexically restricted to either pre- or post-nominal positions (1–2). Others may appear in either position with a lexical change in meaning (3) or under certain discourse conditions (4).

| 1 | El | libro | azul |

| the | book | blue |

| “the blue book” |

| 2 | El | próximo | presidente |

| the | next | president |

| “the next president” |

| 3a | El | mal | cocinero (bad as a chef) |

| the | bad | chef |

| 3b | El | cocinero | malo (a chef who may be bad in some other respect) |

| | the | chef | bad |

| | “the bad chef” |

| 4a | El | peligroso | delincuente (one criminal in the context) |

| the | dangerous | criminal |

| 4b | El | delincuente | peligroso (one criminal among others) |

| | the | criminal | dangerous |

| | “the dangerous criminal” |

Word order is associated with interpretation. Adjectives can modify the whole noun (i.e., intersective) or a subpart of the noun (i.e., non-intersective), as illustrated in (3). The pre-nominal adjective in (3a) only has a non-intersective interpretation, where the chef is bad in his role as a chef (i.e., he does not cook well). The post nominal adjective in (3b) has an intersective reading; it identifies someone who is both a chef and bad as a person. Adjective interpretation can also be contingent on the presence or absence of a contrast set, as illustrated by (4) (i.e., restrictive (R)/non-restrictive (NR)). Absent semantic/prosodic focus (see

Demonte 2008), (4a) only has a NR reading where there is one criminal in the context and that criminal is dangerous, whereas (4b) has a R reading (i.e., a context with multiple criminals, only one of which is dangerous).

Before we consider whether L2 speakers are able to learn the association between form and position, we should highlight that there is a division among syntacticians as to the interpretation of the post-nominal position.

Complementary approaches assumes that the post-nominal position is unambiguously intersective and restrictive (

Alexiadou 2001;

Bernstein 1993;

Demonte 2008;

Ticio 2010). Under this approach, ambiguity is only apparent: once context, lexical meaning, and/or the possibility of contrastive stress are accounted for, pre-nominal adjectives have exclusively non-intersective and non-restrictive interpretations, whereas post-nominal adjectives are unambiguously intersective and restrictive. For example, el cocinero malo “the bad chef” has a non-intersective interpretation post-nominally, not because the post-nominal position is ambiguous, but because we generally refer to chefs in their roles as chefs. In contrast,

post-nominal ambiguity approaches allow for both interpretations post-nominally (i.e., non-intersective/intersective, non-restrictive/restrictive) (

Cinque 2010;

Fábregas 2017;

Martín 2009), while attributing a special, marked status to the pre-nominal position. A syntax void of post-nominal ambiguity could not, for example, account for the possibility that all Elena’s classes are boring in las clases aburridas de Elena “Elena’s boring classes” (

Fábregas 2017, p. 28).

Adjectival order and interpretation is not a phenomenon particularly vulnerable to bilingual transfer.

Camacho (

2018) found that heritage Spanish speakers evidenced the same ordering restrictions as baseline speakers; they rated post-nominal adjectives higher than pre-nominal adjectives in restrictive contexts. This was true of color and nationality adjectives, which are lexically restricted to post-nominal position, and adjectives that could, in principle, appear in either position. Nonetheless, for adult learners whose native language has a fixed pre-nominal position, post-nominal adjectives may offer evidence of having learned novel underlying structure, on the common premise that post-nominal adjectives in Romance result from raising of the noun to intermediate functional projections, leaving adjectives behind (

Gess and Herschensohn 2001;

de Garavito and White 2002). A number of L2 studies have found L2 learners possess knowledge of the placement and relative meaning of adjectives in French and Spanish.

Anderson (

2001,

2008) found English-speaking advanced L2 learners of French assigned target lexical meanings according to position. They interpreted pre-nominal adjectives as non-intersective and post-nominal adjectives as intersective (e.g., simple robe/robe simple “mere dress/plain dress”). Intermediate speakers had only learned post-nominal intersective adjective meanings. Although

Anderson (

2001,

2008) concluded that implicit structural knowledge had taken place, inductive learning combined with instruction is also a plausible explanation for these results.

Anderson (

2007a) found that English-speaking intermediate and advanced L2 learners of French differed from native speaker controls when tested on the interaction between word order and NR/R interpretation. Native speakers accepted pre-nominal adjectives well above chance in NR contexts, while L2 speakers preferred post-nominal adjectives. This is an expected result if they have internalized the pedagogical rule (

Anderson 2007b). Nonetheless,

Anderson (

2007a) argues against fundamental differences between native and L2 speakers because both had significantly lower rates of acceptance of pre-nominal adjectives in R contexts. However, methodological issues limit interpretability of the results: relevant trials were not minimal pairs; the uniqueness presupposition of the definite article was not met in the R context, which may have led to lower ratings across speaker groups.

A subsequent study examined L1-French L2-Spanish acquisition, a language pair with both substantial overlap and interlanguage differences. Overall, pre-nominal adjectives are less frequent in Spanish than in French (

Scarano 2005;

Rizzi et al. 2013), but certain lexical classes actually allow for more pre-nominal adjectives (

Androutsopoulou et al. 2008), including adjectives that express a speakers’ evaluation (e.g., una fantástica película/ *un fantastique film “a fantastic film”) and ordinals (la siguiente pregunta/ *la suivante question “the next question”).

Androutsopoulou et al. (

2008) found that French-speaking intermediate and advanced learners judged Spanish pre-nominal evaluative adjectives that were grammatical in French as significantly better than those where the two languages differed. There were less transfer effects for ordinals. Based on the high degree of variability in L2 judgements,

Androutsopoulou et al. (

2008) conclude that acquisition proceeds on an item-by-item basis, and is initially influenced by the L1.

Other studies have found that advanced learners of Spanish interpret and produce pre-nominal and post-nominal adjectives with near-native proficiency (

Judy et al. 2008;

Guijarro-Fuentes et al. 2009;

Rothman et al. 2009,

2010). These studies used various combinations of the following tasks: grammaticality judgement combined with correction tasks (GJCT); context-based collocation tasks (CBCT), where participants read a short context and then fill in the adjective provided in pre- and/or post-nominal position; and preferred gloss tasks (PGT), where participants read sentences containing a pre- or post-nominal adjective and choose between two potential glosses provided. These studies found attainment across the various language pairings, at least for the CBCT and the PGT.

Judy et al. (

2008) found advanced English-speaking learners of Spanish to be native-like in the CBCT, but unable to reject lexically pre-nominal adjectives (2) in post-nominal position in the GJCT.

Guijarro-Fuentes et al. (

2009) found similar results for Italian and English-speaking learners of Spanish in the CBCT and PGT, with L1 Italian speakers converging on the target grammar earlier.

Rothman et al. (

2009) compared performance of a group of Germanic (English, German) speaking and Italian-speaking intermediate and advanced learners of Spanish; neither the advanced Germanic group nor the intermediate and advanced Italian groups differed from native speaker controls on any of the tasks. Lastly,

Rothman et al. (

2010) report L2 convergence for the CBCT and PGT for a population of exclusively English-speaking learners of Spanish and a correlation between these tasks and GJCT performance. Taken together, these studies show success in adult learning of adjective distribution. However, a number of issues with these studies leave the question of interpretation open.

The first issue is that these studies assume a

complementary approach even when the intuitions of their native speaker controls contradict this analysis. Native speakers placed adjectives significantly less pre-nominally in NR contexts than predicted by a

complementary approach in the CBCT data reported in

Judy et al. (

2008),

Rothman et al. (

2009) and

Guijarro-Fuentes et al. (

2009). In

Rothman et al. (

2010) the data appears complementary, as native speakers overwhelmingly interpreted pre-nominal adjectives as NR and post-nominal adjectives as R. One concern is the absence of minimal pairs.

Rothman et al. (

2010) selected 20 lexical items for the two experiments, but used each adjective only once per task. So, for example, estudioso “studious” was used pre- but not post-nominally in the PGT, whereas in the CBCT it was provided in a R, but not a NR context. Given the primacy of the lexical factor in this domain, this is problematic. The pre-nominal use of an adjective like estudioso “studious” regardless of context is quite marked in comparison to an adjective such as valiente “brave”. The acceptability of individual lexical items in pre-nominal position is affected by syllabic weight (adjectives shorter than the nouns they modify are more felicitous in pre-nominal position) and register (written register facilitates pre-nominal use;

File-Muriel 2006;

Centeno-Pulido 2012;

Hoff 2014). These factors may have combined to support complementary performance. For example, a participant who assigned a NR reading to los estudiosos estudiantes “the studious students” in the PGT, might have dispreferred the pre-nominal position in the CBCT regardless of interpretation.

These studies also claim there is an absence of explicit instruction. This assumption is somewhat problematic, because the relationship between adjective position and restrictivity is the target of explicit instruction in various standard textbooks (see

King and Suñer 2008, p. 158;

Salazar et al. 2013, p. 294;

Zayas-Bazán et al. 2014, p. 17;

Bleichmar and Cañón 2016, p. 16). A

complementary approach is presupposed by most pedagogical treatments; intermediate and advanced Spanish textbooks standardly describe the subclass of adjectives that can be pre- or post-nominal in terms of known quality vs. contrast:

“When placed after a noun, adjectives serve to differentiate that particular noun. Adjectives can be placed before a noun to emphasize or intensify a particular characteristic, to suggest that it is inherent or to create a stylistic effect or tone. In some cases, placing an adjective before the noun indicates a value judgement on behalf of the speaker (

Bleichmar and Cañón 2016, p. 16).”

This kind of instructional material may be the source of L2 speakers’ categorical judgements.

Furthermore, the role of the English L1 merits additional consideration. Grammars contain rules that allow for the existence of sub-regularities or idiosyncratic constructions that are lexically triggered (i.e., subgrammars) (

Amaral and Roeper 2014). For example, English participial adjectives and adjectives formed with the modal suffix –able/-ible can appear in both pre- and post-nominal positions, and this alternation also maps into the R–NR contrast (see

Bolinger 1967;

Larson and Marusic 2004;

Cinque 2010,

2014) (5–8).

- 5.

Every blessed person was healed

| 5a | “Every person was healed; they were blessed” | (NR) |

| 5b | “Every person that was blessed was healed” | (R) |

- 6.

Every person blessed was healed

| 6a | #“Every person was healed; they were blessed” | (NR) |

| 6b | “Every person that was blessed was healed” | (R) |

- 7.

Every unsuitable word was deleted

| 7a | “Every word was deleted; they were unsuitable” | (NR) |

| 7b | “Every word that was unsuitable was deleted” | (R) |

- 8.

Every word unsuitable was deleted

| 8a | #“Every word was deleted; they were unsuitable” | (NR) |

| 8b | “Every word that was unsuitable was deleted” | (R) |

Pre-nominal adjectives (5,7) are ambiguous between a NR reading (where the adjective applies to all the nouns in a given context) and a R reading (where it applies to only some of the nouns, i.e., the contrast set). The post-nominal adjective (6,8) on the other hand may only be interpreted restrictively. This is exactly what

Rothman et al. (

2010) find for some intermediate speakers in the PGT. The target-deviant group performed significantly worse when asked to provide preferred glosses for pre-nominal vs. post-nominal adjectives.

Rothman et al. (

2010) attributes this performance to the effect of repeated instruction presenting the post-nominal position as the default in Spanish. However, reliance on the L1 subgrammar can predict precisely these results.

The relationship between word order and restrictivity

complementary approaches assume can be at least partially derived from the English subgrammar. To arrive at

post-nominal ambiguity a learner referencing the English subgrammar only has to (1) recognize the parallels between the pre-nominal in English and post-nominal in Spanish, and (2) identify the pre-nominal as expressing subjective speaker judgements in Spanish. As soon as the subjective use of the pre-nominal is identified, non-restrictivity comes for free; cross-linguistically subjective adjectives are not used restrictively (see

Martin 2014;

Umbach 2006,

2016). The first acquisition step is straightforward considering (a) the cumulative effect of explicit instruction of the post-nominal (i.e., more classes of adjectives are either optionally obligatorily post-nominal than pre-nominal), as suggested by Rothman, and (b) the free use of lexically post-nominal adjectives with restrictive and non-restrictive interpretations (e.g.,

el cometa azul ‘the blue kite’). The second step is supported by pedagogical treatments of the Spanish pre-nominal as subjective (see

Bleichmar and Cañón 2016;

Finnemann and Carbón 2001). All of these factors can support learners’ mapping of the restrictivity contrast in Spanish, without appealing to underlying restructuring of the grammar. If this reasoning is correct, additional experimental evidence is needed. We propose that evidence on single adjective position be augmented with evidence on what learners know about the position of adjectives in two-adjective sequences.

Our approach is as follows: we first ask whether native speakers of Spanish show patterns of interpretation along the lines of the complementary approach or the post-nominal ambiguity approach. We then compare them to non-native speakers, arguing that the complementary pattern is compatible with an effect of explicit instruction. After categorizing native and non-native Spanish grammars with respect to single adjective placement, we evaluate non-native Spanish speakers’ capacity for structure building by examining how they perform with two-adjective sequences. These contexts can provide key information on how learners map the hierarchical structure of the Spanish noun phrase. To show how, we first need to explain how the pre-nominal position in Spanish relates to the orders observed in adjectival sequences.

In Spanish, like in other languages, adjective sequences obey ordering restrictions (AORs), which have been described in various ways in the literature. The

unified base hypothesis (

Cinque 2010) holds that across languages, adjectives are ordered according to the same hierarchical structure, with certain classes of adjectives merged closer to the noun. According to this view, direct modifier adjectives—adjectives that directly attribute a characteristic to the noun—are strictly ordered amongst themselves via a notionally based hierarchy, where nationality adjectives appear closest to the noun followed by color, then shape, then size and, finally, value adjectives (for similar typologies see

Tribushinina et al. 2014 and references therein). This proposal accounts for the seeming mirror image distribution of adjectives across languages (cf. English

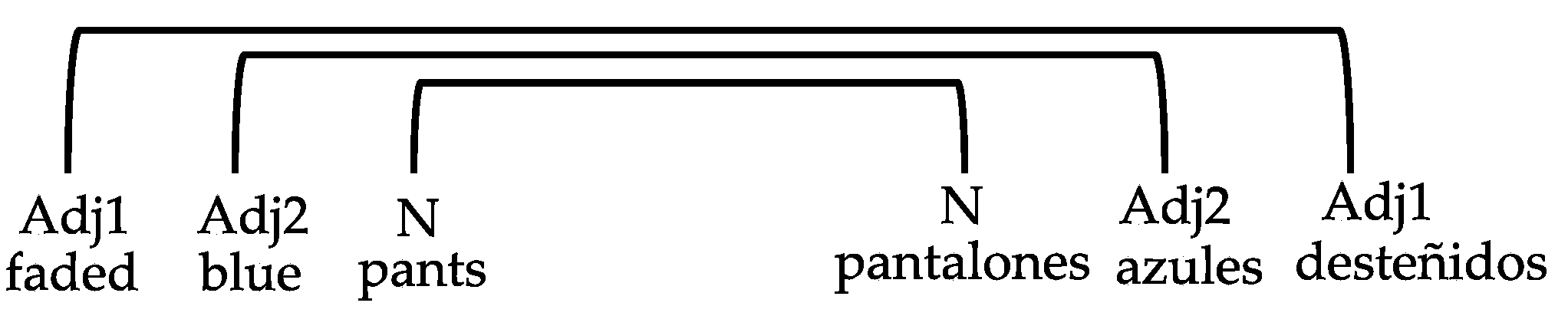

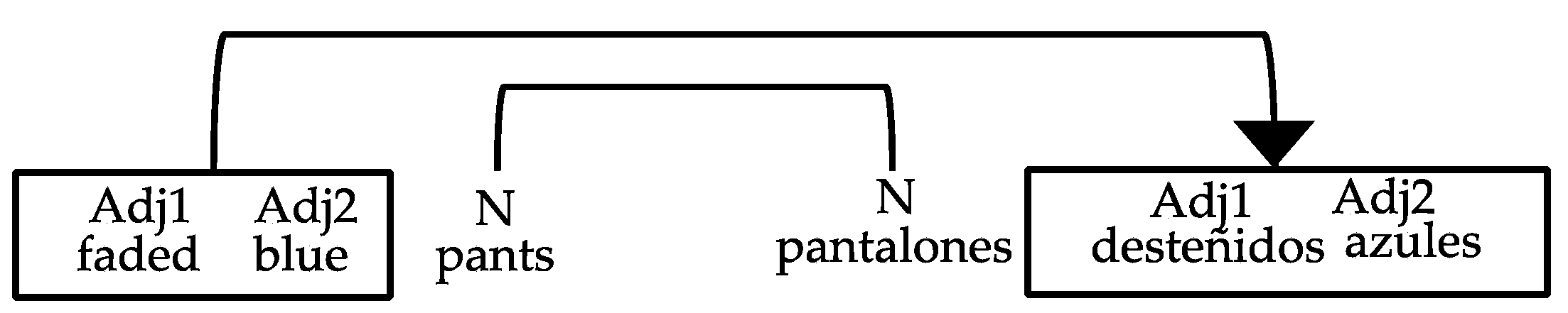

faded blue pants and Spanish

pantalones azules desteñidos, where, in both cases, the size adjective is always closest to the noun).

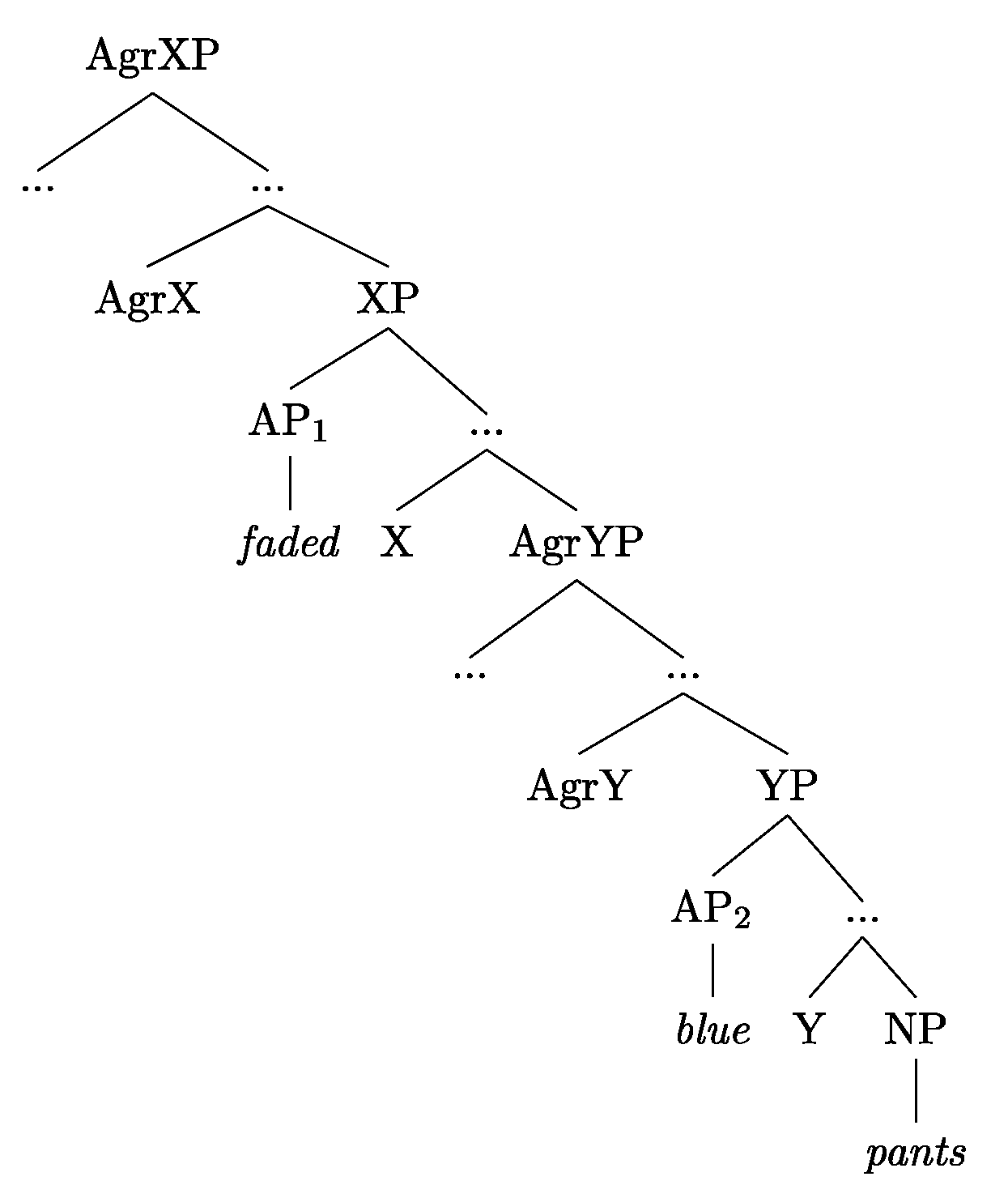

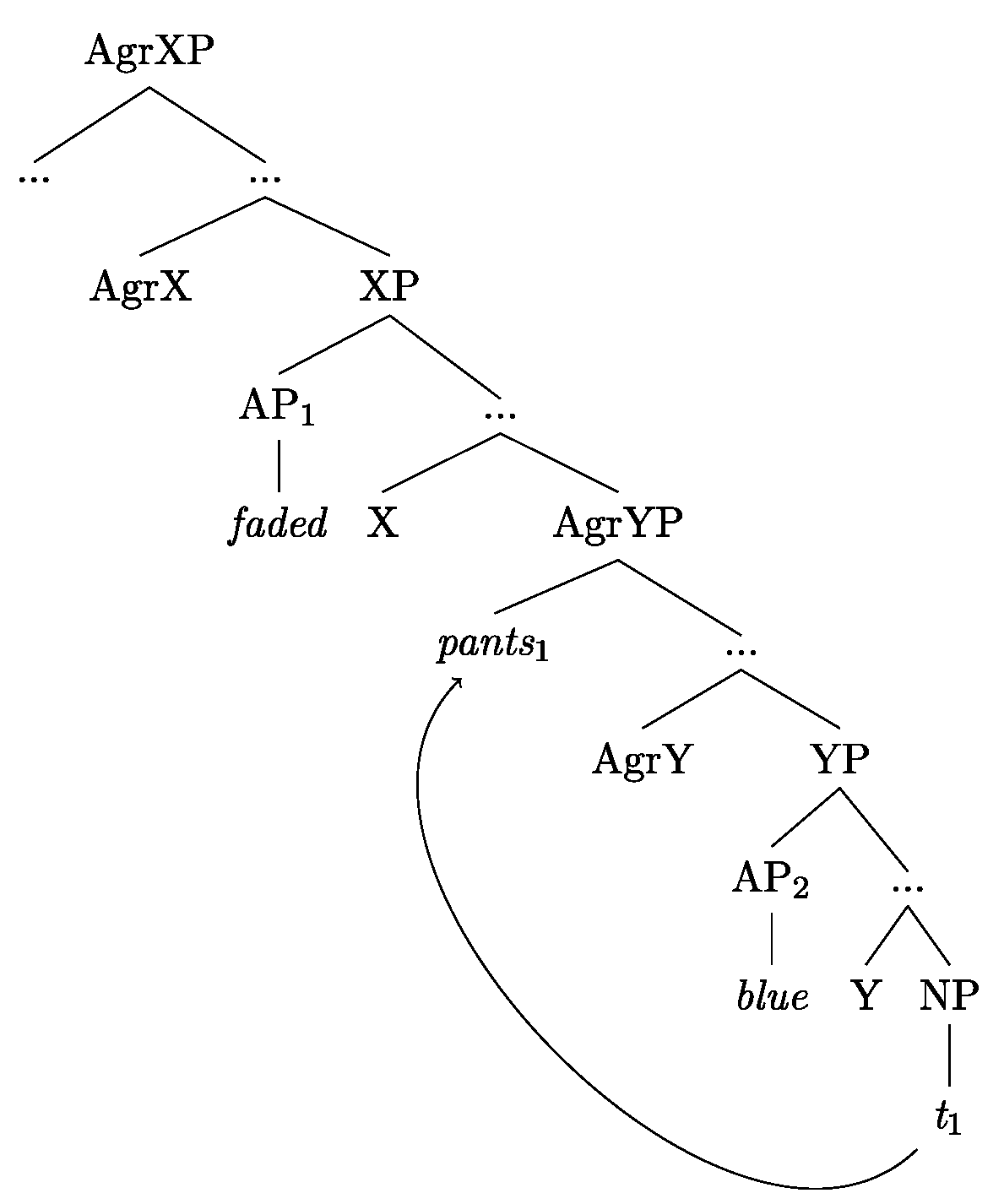

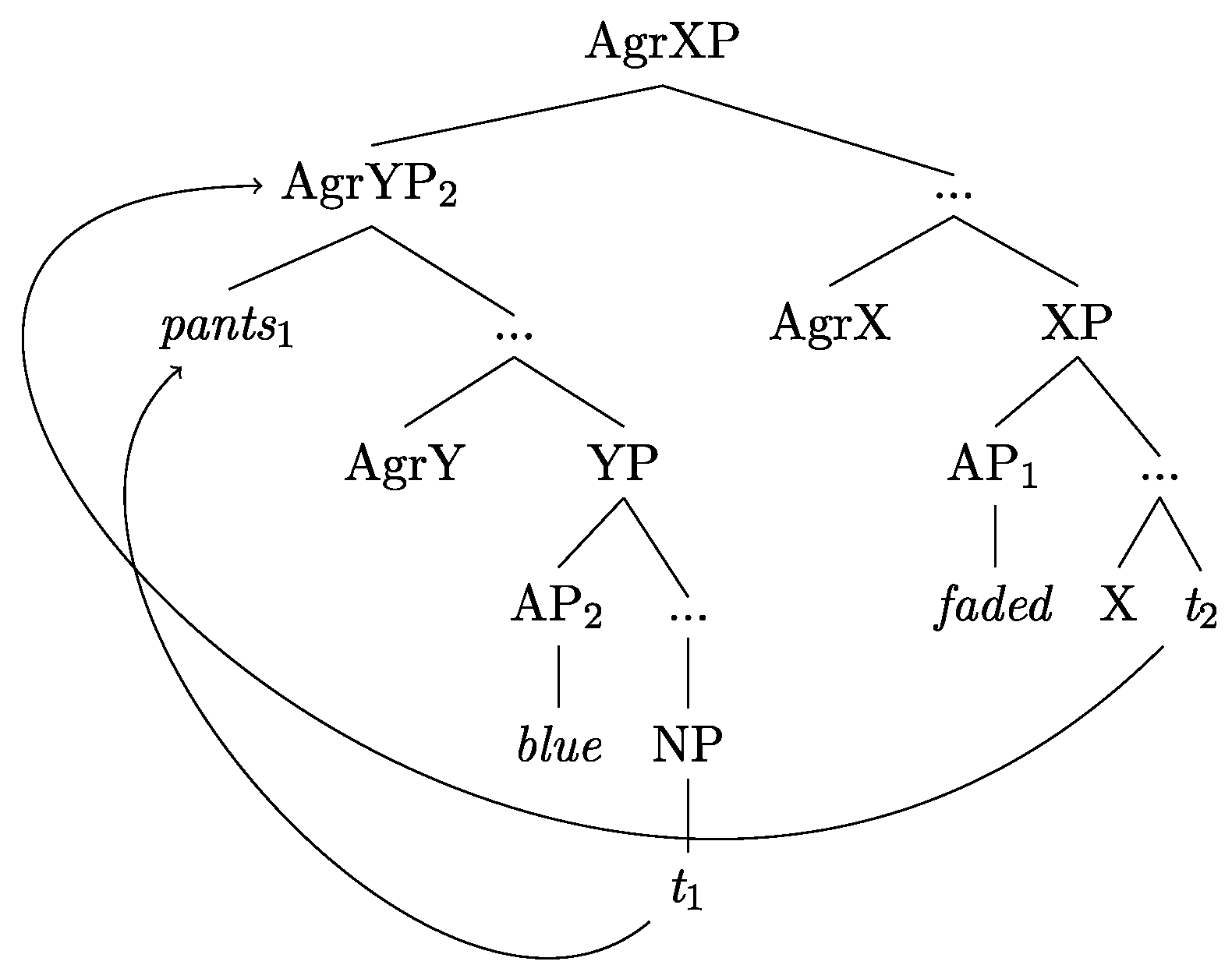

Cinque (

2010) derives the Spanish order from an English linear base order via (9a) cyclic movement, where the noun moves and left adjoins to the closest adjective, i.e.,

blue (9b), and in a subsequent movement the noun (N) – adjective (Adj) sequence (i.e., N + Adj2) rolls up and left adjoins to the furthest adjective from the noun, i.e., faded (9c).

- 9.

English Order: Adj1 Adj2 N “faded blue pants”

Interpolated Sequence: Adj1 N Adj2 desteñidos pantalones azules “faded pants blue”

Spanish Mirror Image Order: N Adj2 Adj1 pantalones desteñidos azules “pants blue faded”

AORs can be broken if one or both adjectives is an indirect modifier. These are adjectives whose modification relationship to the noun is mediated by an intervening (reduced) relative clause. They are further from the noun than direct modification adjectives, but freely ordered amongst themselves (see

Sproat and Shih 1991 for a detailed account of the indirect-direct modifier distinction) (10).

- 10.

| 10 | pantalones | desteñidosdirect/indirect | azulesindirect |

| pants | faded | blue |

Despite the possibility of alternative, marked orders, such as in (10), Spanish is supposed to adhere to AORs both within and across lexical semantic classes (i.e., N > intersective {nationality > color > shape} > non-intersective {size > value}). The picture is however, more complex. Counterarguments include the reduced number of possible pre-nominal adjectives in Spanish and the relative freedom of adjective order, both pre-nominal and post-nominal (

Sánchez 1996,

2018;

Demonte 1999a,

1999b). The

intersective > non-intersective hypothesis claims that adjectives interpreted intersectively (e.g., color and shape) are closer to the noun than: (a) those with non-intersective interpretations (e.g., value) and (b) those whose interpretation is context dependent (e.g., size) (see

Kamp and Partee 1995) (

Demonte 1999a,

1999b). This hypothesis makes the same macro-level distinction that the

unified base hypothesis does for direct modifiers (i.e., N > intersective > non-intersective), but predicts optionality at the micro-level (i.e., N > nationality/color/shape > size/value). For example, un niño pequeño lindo “a boy small sweet” and un niño lindo pequeño “a boy sweet small” should be equally possible. Finally, the

free ordering hypothesis suggests that adjective ordering is (at least partially) free of lexical-semantic restrictions (

Sánchez 2018). Adjectives of at least color, shape, and nationality are shown to be freely ordered in a manner comparable to indirect modifiers in the

unified base hypothesis.

There is not much empirical work on adjective sequences. A recent corpus study by Pérez

Leroux et al. (

2020) suggest that some degree of ordering restrictions appear if one considers interpolated adjective–noun–adjective (Adj–N–Adj) sequences. These authors extracted post-nominal sequences of adjectives (N–Adj–Adj) and interpolated Adj–N–Adj sequences from the Google Ngram Corpus and the Corpus del Español, arguing that interpolated sequences can be used to enrich the data on AORs in Spanish. The

unified base hypothesis analyzes the pre-nominal adjective in interpolated sequences, which is further from the nominal head in terms of scope, as corresponding to the second adjective in post-nominal sequences (9b,c). Their data show an ordering asymmetry between relational adjectives—denominal adjectives that attribute to the noun they modify a relationship with a class described by their nominal root (un mandato parlamentario “a parliamentary mandate” is a mandate by/for parliament) and qualifying adjectives—adjectives that denote qualities or properties of entities (el carro azul “the blue car”, la manzana podrida “the rotten apple”) (see

Demonte 1999a;

McNally 2016). Relational adjectives were hierarchically closer, relative to qualifying adjectives, and other classes. Value adjectives, a subset of qualifying adjectives appeared further from the noun than qualifying color adjectives (hermoso color negro “beautiful color black”), and other types. While the data was too sparse to assess key combinations (such as value and size) (9), it was sufficient to clearly support the

intersective > non-intersective hypothesis.

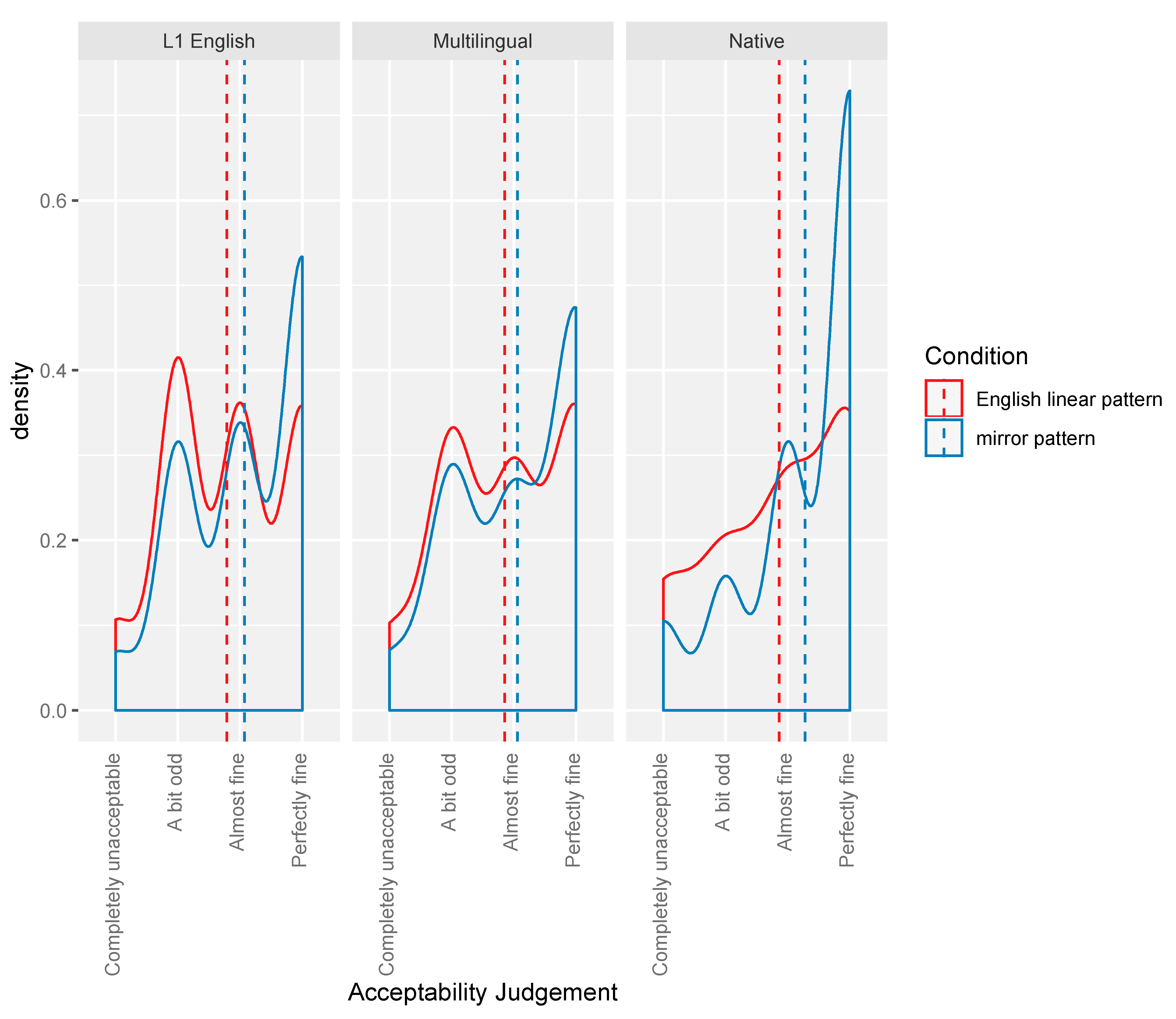

Under the assumption that Spanish interpolated Adj–N–Adj sequences are derived via movement of the N past direct modification adjectives (whose order is at least color/shape>size/value), and that two post-nominal adjectives are derived by an additional application of roll-up movement, the evidence supports that (at least) the macro structure for direct modifiers is the result of a unified base. Despite the flexibility in adjective ordering, native Spanish speakers are likely to judge the mirror pattern (11a) as the acceptable, unmarked option, and should prefer it to the order shown in (11b), which is the marked order. Note that this order is surface-equivalent to a post-nominal version of the English linear pattern.

- 11.

Mirror pattern

English linear pattern

Now, for non-native learners, the question is, do they pattern similarly? If we assume that when they learn that Spanish adjectives are post-nominal, they also employ a cyclic derivation to derive such post-nominal orders, we predict that they too should prefer the mirror pattern to the English linear pattern. As the structure in English corresponds to the base structure before roll-up movement, English-speaking learners of Spanish would have to access this structural operation in order to converge on the target grammar (11a). Alternatively, if learners are limited to surface level learning, they should prefer the English linear pattern (11b).

Importantly, if we find convergence for two-adjective sequences, explicit learning cannot explain why learners have acquired it.

1 Two-adjective sequences are fairly rare, and most of the two-adjective sequences attested in the corpus study discussed above were sequences of relational adjectives, the most frequent category. Most of the remainder involved at least one relational adjective. Only interpolated sequences offer evidence of other combinations. For this input to be informative, learners would need to recognize these alternative sequences as arising from a roll-up derivation. Because adjective sequences are both infrequent and nearly absent in explicit instruction, we hypothesize that sensitivity to word order is indicative of learner’s underlying syntactic derivations. Conversely, lack of sensitivity suggests a lack of underlying structural reanalysis.

The present study has two overarching goals. The first goal is to evaluate whether native and non-native speakers evidence

complementarity or

post-nominal ambiguity when the noun is modified by a single adjective. The second is to evaluate whether L2 speaker’s post-nominal adjectives result from underlying structural reanalysis. Given the limited use of pre-nominal adjectives in Spanish (

Scarano 2005;

Rizzi et al. 2013;

Pettibone 2021), we hypothesize that native speaker results will support

post-nominal ambiguity, but we remain neutral as to whether learners evidence

complementarity as predicted by explicit instruction or

post-nominal ambiguity. To evaluate Spanish learner’s structure-building abilities we turn to comparing two-adjective sequences in learners and native speakers. Our research questions are:

Question 1: Single adjective modification in context

- (a)

Do native Spanish-speaker intuitions point to complementarity or post-nominal ambiguity?

- (b)

Are Spanish learners sensitive to the interactions between position and interpretation? If so, do their intuitions align with complementarity or post-nominal ambiguity?

Question 2: Two-adjective sequences and structural reanalysis

- (a)

Do native Spanish speakers judge the mirror pattern as more acceptable than the English linear pattern?

- (b)

Do Spanish learners show sensitivity to lexical classes and their preferred placement?; and

- (c)

Do Spanish learners have intuitions about preferred orderings of two-adjective sequences? If so, do they favor the mirror image pattern, or do they prefer English-linear sequences as predicted by surface level learning accounts?

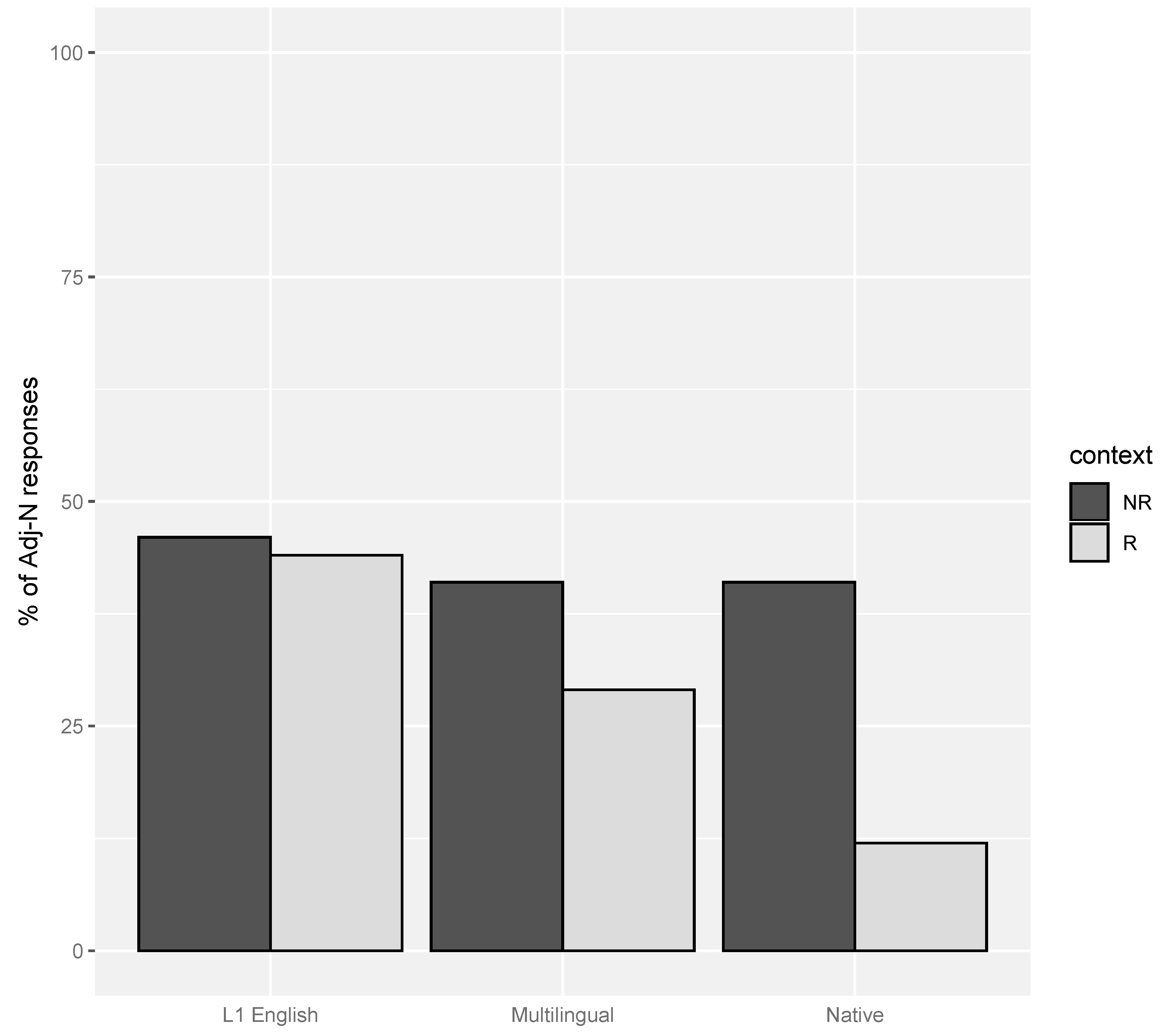

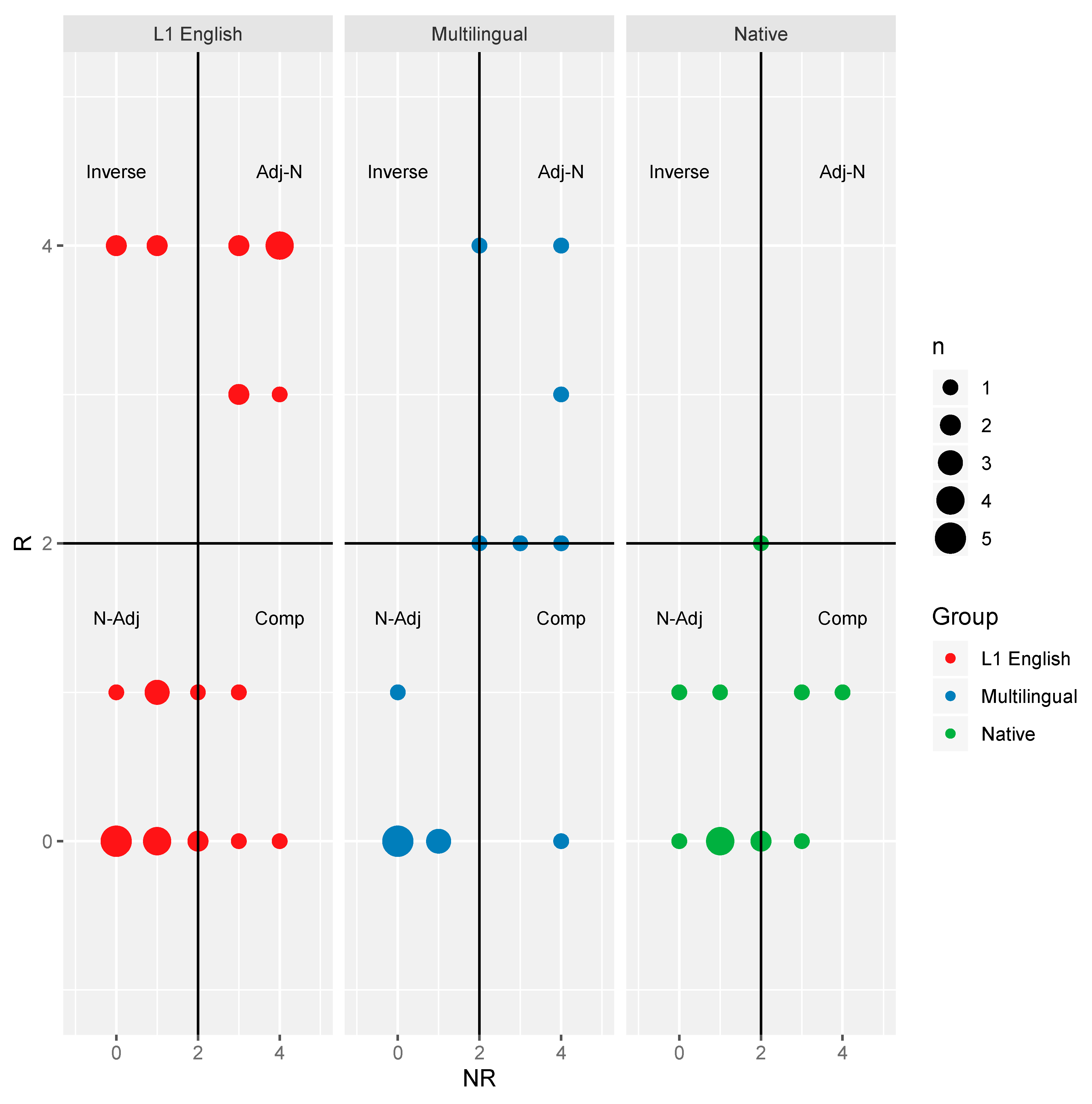

To answer the first set of questions, we designed a preference task inviting speakers to choose between pre-nominal and post-nominal adjectives in restrictive and non-restrictive contexts. To address the second set of questions, we developed an acceptability judgement task to probe which adjective orders were rated as more acceptable.

2. Materials and Methods

Participants completed two tasks run using SuperLab© software. A Preference Task (PT) (

Appendix A) modeled on previous work by

Rothman et al. (

2010), asked participants to choose between minimal pairs of sentences (8 items total, 4 per context) that differed as to the position of the adjective with respect to the noun (i.e., pre- or post-nominal) given a NR (12) or R context (13). For all tasks, a short context was presented on an initial screen. Participants pressed a button on the keypad to continue to the test item. For the PT, a colored button appeared next to each sentence that corresponded to a button on the keypad. For the Acceptability Judgement Task (AJT), an illustration of the keypad along with its corresponding scale (in words) appeared concurrently with the target sentence to be judged.

- 12.

No hay torero que no sea conocido por su coraje; es decir ser torero es enfrentar peligro a diario. “There is not a bullfighter who is not known for their courage, it is to say that to be a bullfighter is to face danger every day.”

| 12a | Los | valientes | toreros | no | tienen | miedo | de |

| the | brave | bullfighters | NEG | have | fear | of |

| arriesgar | la | vida | | | | |

| risk-INF | the | life | | | | |

| 12b | Los | toreros | valientes | no | tienen | miedo | de |

| the | bullfighters | brave | NEG | have | fear | of |

| arriesgar | la | vida | | | | |

| risk-INF | the | life | | | | |

| | “The brave bullfighters are not afraid to risk their lives” |

- 13.

Algunos soldados son valientes; otros son cobardes. “Some soldiers are brave and others are cowards”

| 13a | #Los | valientes | soldados | arriesgan | la | vida |

| the | brave | soldiers | risk | the | life |

| con | frecuencia | | | | |

| with | frequency | | | | |

| 13b | Los | soldados | valientes | arriesgan | la | vida |

| the | soldiers | brave | risk | the | life |

| con | frecuencia | | | | |

| with | frequency | | | | |

| | “The brave soldiers risk their lives frequently” |

Prior to the PT, participants saw three training items–two where they had to choose between grammatical and ungrammatical sentences with either ser and estar “to be”, and one that manipulated the subjunctive/indicative mood following no es una sorpresa que “it is not a surprise that”. The PT contained eight fillers where participants had to choose between two sentences containing either a noun modified by a bare prepositional phrase (PP) or a relative clause (RC). The following adjectives appeared in the experimental items: poderosos “powerful”, altos “tall”, bellas “beautiful”, valientes “brave”, inteligentes “intelligent”, fuertes “strong”, rápidos “fast”, saludables “healthy”, corresponding to the following notionally based semantic classes: behavioral property (poderosos “powerful”, fuertes “strong”), size (altos “tall”), value (bellas “beautiful”, saludables “healthy”), internal state (valientes “brave”, inteligentes “intelligent”) and physical property (rápidos “fast”). As a group, these adjectives are uniformly non-intersective and qualifying. Additionally, all adjectives were of equal or lesser syllabic weight than the nouns they modified with the exception of inteligentes “intelligent” and saludables “healthy”, However, these two exceptions can be used evaluatively (despite only saludables “healthy” having the lexical classification of value), increasing their acceptability in pre-nominal position.

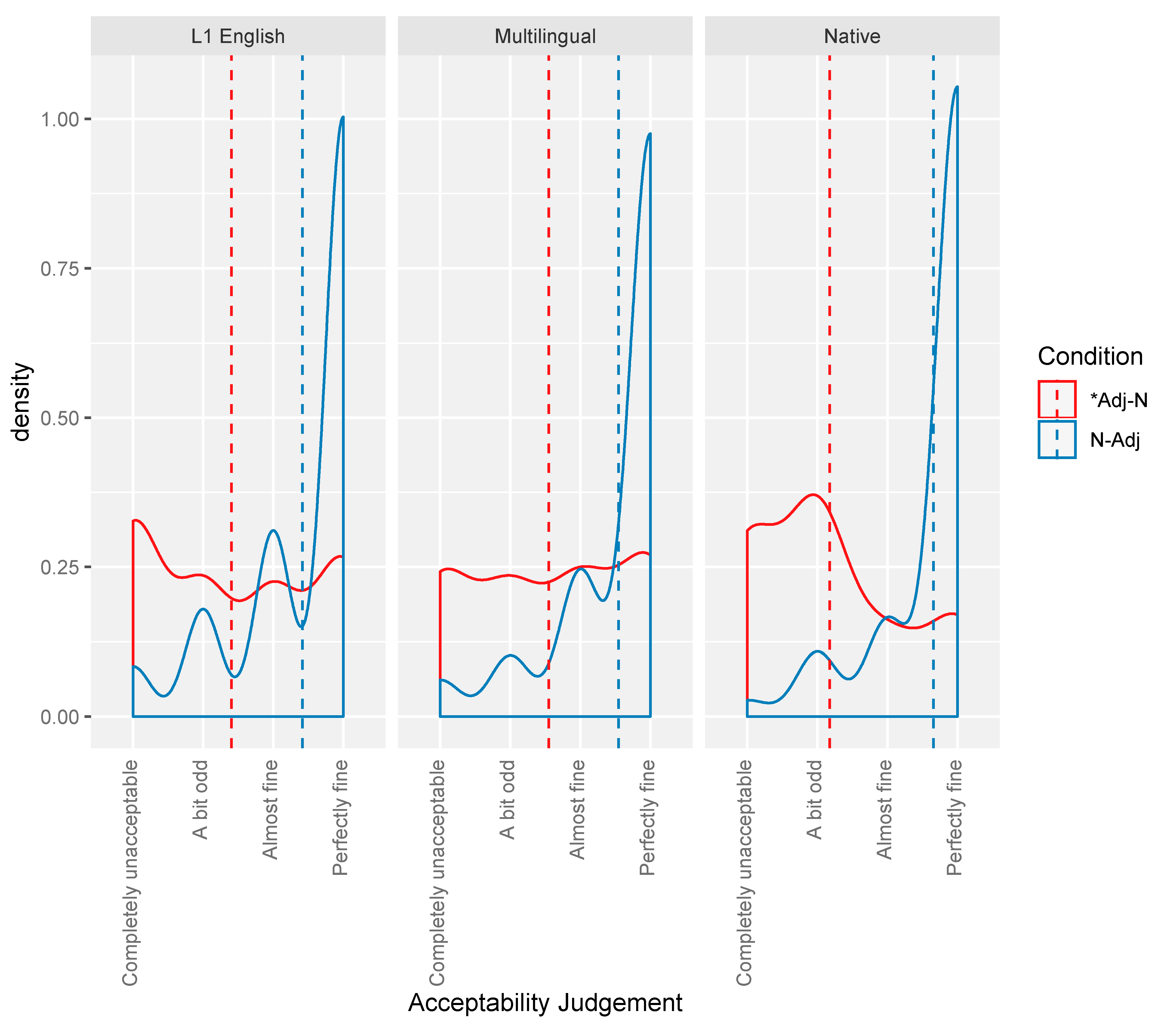

In addition, participants completed an Acceptability Judgement Task (AJT) (

Appendix B) where, after reading a short context, they were asked to provide scalar judgements (i.e., completely unacceptable, a bit odd, almost fine, completely acceptable) of sentences that manipulated the placement of single, obligatorily post-nominal relational adjectives (14) (8 items total, 4 per order), or of multiple adjectives (15) (8 items total, 4 per order):

- 14.

| 14a | El | contrato | legal |

| the | contract | legal |

| 14b | *El | legal | contrato |

| | the | legal | contract |

| | “the legal contract” |

- 15.

| 15a | Mirror pattern | Las | cortinas | amarillas | horribles |

| | the | curtains | yellow | horrible |

| 15b | English linear pattern | Las | cortinas | horribles | amarillas |

| | | the | curtains | horrible | yellow |

| | “the horrible yellow curtains” | |

Prior to the AJT participants saw three training items consisting of a short context followed by a sentence that either followed naturally from the context (

n = 1) or did not (

n = 2). Fillers in the AJT (

n = 15) manipulated the inalienability of a noun and a PP modifier headed by con “with” or sin “without”

(n = 8); and the acceptability of lexical PP modifiers to establish a locative relationship between two nouns (

n = 7). Multiple adjective items consisted of adjective pairs that included one relational and one qualifying adjective (

n = 4) or two qualifying post-nominal adjectives (

n = 4) presented in mirror image or English linear pattern. For single adjectives, the following lexical items appeared in the AJT: legal “legal”, política “political”, mensual “monthly”, industrial “industrial”, metálica “metallic”, solar “solar”, plástico “plastic”, and personal “personal”. Two-qualifying- adjective sequences corresponded to color > extreme degree (cortinas amarillas horribles “horrible yellow curtains”), color > physical property (saco negro desteñido “faded black sweatshirt”), shape > value (mesa redonda cara “expensive round table”), and color > physical property (melón verde podrido “rotten green melon”). Two – relational and qualifying – adjective sequences corresponded to relational > size (el puerto marítimo grande “the big maritime port”), relational > value (un manual escolar confuso “a confusing school manual”), relational > manner (el paseo campestre largo “the long country outing”), and relational > size (una vaca lechera grande “a big milking cow”).

2