Differential Access: Asymmetries in Accessing Features and Building Representations in Heritage Language Grammars

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Modeling Heritage Speakers’ Grammars

- Stage 1: Transfer or re-assemble of some FFs (formal features) from the L2 grammar to the L1 phonological features (PF) and semantic features which may coincide with the activation of L2 lexical items on a more frequent basis from the standpoint of linguistic production;

- Stage 2: Transfer or re-assemble of massive sets of FFs from the L2 to the L1 PF and semantic features, while concurrently showing significantly higher rates of activation of L2 lexical items than L1 lexical items for production purposes (i.e., they might code-switch more than bilinguals in the previous situation);

- Stage 3: Exhibit difficulties in activating PF and semantic features (as well as other FFs) in the L1 for production purposes but are able to do so for comprehension of some high frequency lexical items; and,

- Stage 4: Have difficulties activating PF features and semantic features (as well as other FFs) in the L1 for both production and comprehension purposes.” (Putnam and Sánchez 2013, pp. 489–90)

3. Differential Access in Heritage Grammars

Operationalizing Activation and Access

- Access, select, and compile the appropriate grammatical information for structures containing obligatory mood selection in Spanish; and,

- Inhibit (i.e., block) competing structures from another co-activated source grammar, such as non-finite constructions and indicative verbal forms (see Section 4.1 for more details)

4. Providing Empirical Evidence: Obligatory and Variable Mood Selection in Spanish HS

The theoretical problems revolve around the question of the universality of TAM categories, which can take either of two forms. First, do the semantic concepts underlying tense, aspect, and modality constitute cross-linguistic universals, and do languages differ only in which categorical distinctions are overtly grammaticalized (Jakobson 1959; von Fintel and Matthewson 2008)? Second, are the relevant TAM concepts universally coded in particular functional positions, which are projected in every language (Ritter and Wiltschko 2004; von Fintel and Matthewson 2008)?

4.1. A Brief Overview of Mood Selection in Spanish and English

- 2

- Juan quiere que hable/*habla menosJuan wants that talk.3SG.SUBJ/*talk.3PL.IND less“Juan wants him/her to talk less.”

- 4 a.

- [Juani quiere [que [pro*i/j hable menos]]]Juaniwants that pro*i/j talk.3SG.SUBJ less“Juan wants him/her to talk less.”

- b.

- [Juani quiere [proi/*j hablar menos]]Juaniwants proi/*j talk.INF less“Juan wants to talk less.”

- 7 a.

- Ii want [PROito talk less]

- b.

- (Yoi) quiero [PROi hablar menos](Ii) want [PROi to talk.INF less]“I want to talk less” (co-referential)

- c.

- I want [(for) him/her to talk less]

- d.

- (Yoi) quiero [que hablej menos](Ii) want [that talk.3SG.SUBJi less]“I want him to talk less” (disjoint reference)

- e.

- *(Yo) quiero [(para) él/ella hablar menos](I) want [(for) him/her to talk.INF less“I want (for) him/her to talk less” (disjoint reference)

4.2. Participants and Methodology

- 8

- Example of disjoint reading condition.Dora: Yo estoy cansada y vuelvo para casa, pero tú quédate a jugar un poco más(“I am tired and I am going home, but you can stay and play a bit more.”)Boots: ¡De acuerdo! Gracias Dora.(“Ok! Thanks Dora.”)Target sentence: Dorai quiere que (pro*i/j) siga jugandoDorai wants that (pro*i/j) keep.3SG.SUBJ playing“Dora wants (Boots) to keep playing.”

- 9

- Condition 1: Disjoint reading.Bob Esponja y Patrick planean viajar a Hawaii, pero Bob piensa que su amigo debe visitar la isla antes que él.(“Sponge Bob and Patrick are planning to travel to Hawaii, but Bob wants his friend to visit the island before him.”)Target sentence: Bob Esponja quiere ____ (viajar) a Hawaii antes que élSponge Bob wants ____ (to travel.INF) to Hawaii before him“Sponge Bob wants (space) to travel to Hawaii before him.”

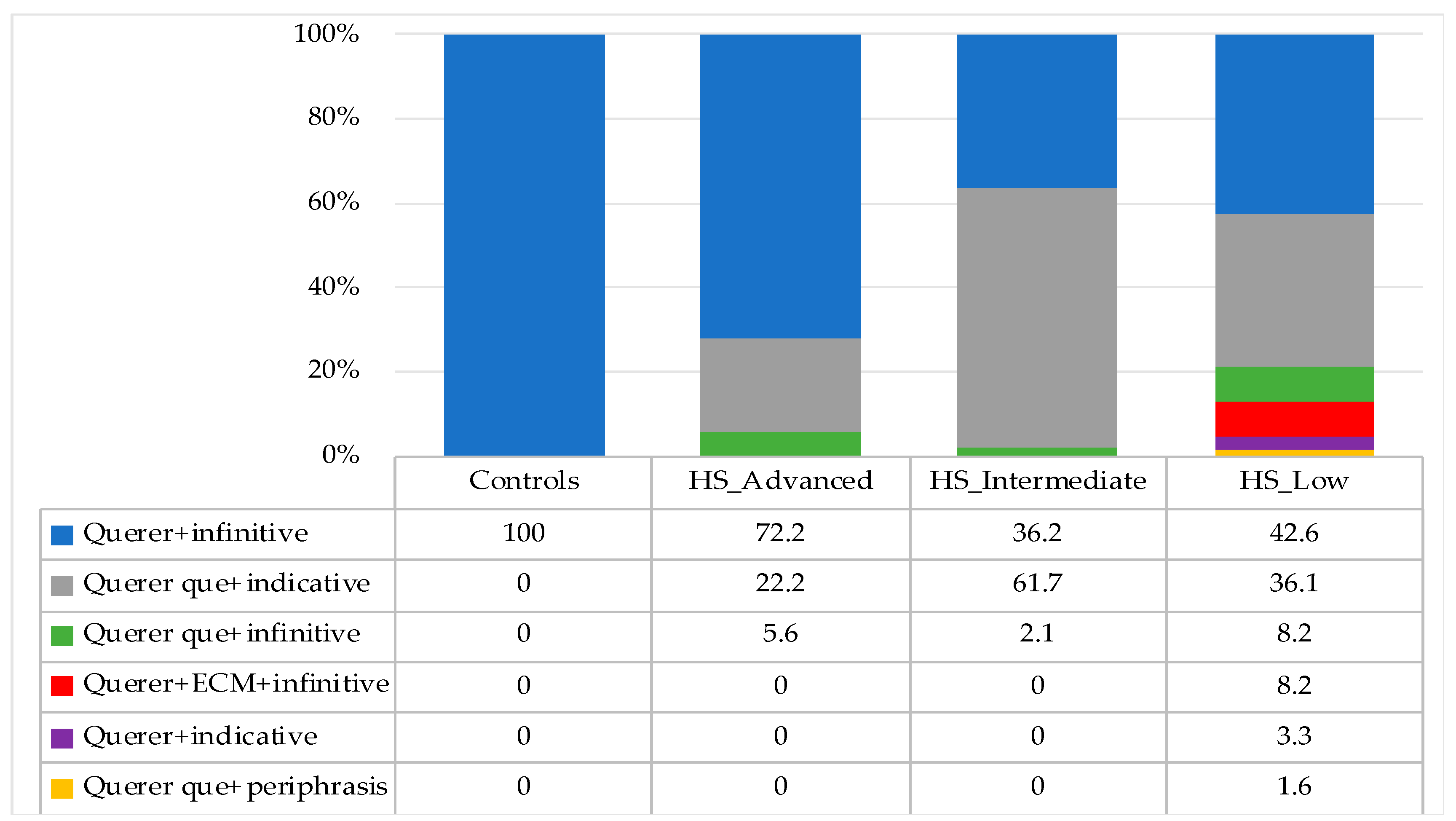

5. Reanalysis of the Data from the Tasks

- 10

- Bob Esponja quiere que Patrick *viajar a Hawaii antesBob Sponge wants that Patrick travel.INF to Hawaii before“Sponge Bob wants Patrick to travel to Hawaii before.”

- 11

- El jefe quiere *María pone canciones más modernasThe boss wants María put.3SG.IND songs more modern“The boss wants María to play more modern songs.”

- 12

- La mama quiere *los niños caminar más rápidoThe mother wants the children walk.inf more fast“The mother wants the children to walk faster.”

6. Further Discussion and Theoretical Analysis

Q1: Is a particular instance of morphological optionality a reflection of a representational deficit/restructuring or a result of missing surface inflection?

Q2: What is the role of proficiency in HS’ performance? More specifically: how can we explain inter-speaker differences within a particular proficiency group as well as similarities between bilinguals with different linguistic abilities?

Q3: Is there a way to reconcile these results in a single model?

- 14

- Quiere que las secretarias hablen[W] menosWants that the secretary talk.3pl.SUBJ less“He wants the secretaries to talk less.”

- 15

- *Quiere que las secretarias hablan[W] menosWants that the secretaries talk3.pl.IND less“He wants the secretaries to talk less.”

- 16 a.

- *Quiere que las secretarias hablar[W] menosWants that the secretaries talk.lNF less“He wants the secretaries to talk less.”

- b.

- * Quiere (para) las secretarias/ellas hablar[W] menosWants (for) the secretaries/ they to talk.lNF less“He wants the secretaries to talk less.”

- 17

- *Quiere que las secretarias tienen que hablar[W] menosWants that the secretaries have to talk.3PL.INF less“He wants the secretaries to talk less.”

- 18

- *Quiere (para)[w] los niños caminar más rápidoWants (for) the children to walk.INF more fast“He wants the children to walk faster.”

7. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Aalberse, Susan, and Pieter Muysken. 2013. Language contact in heritage languages in the Netherlands. In Linguistic Superdiversity in Urban Areas: Research approaches. Edited by Joana Duarte and Ingrid Gogolin. Amsterdam and Philadelphia: John Benjamins, pp. 253–74. [Google Scholar]

- Aarts, Bas. 2012. The subjunctive conundrum in English. Folia Linguistica 46: 1–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abutalebi, Jubin, and David Green. 2007. Bilingual language production: The neurocognition of language representation and control. Journal of Neurolinguistics 20: 242–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berman, Ruth. 2004. Between emergence and mastery: The long developmental route of language acquisition. In Language Development across Childhood and Adolescence. Trends in Language Acquisition Research. Edited by Ruth Berman. Amsterdam: John Benjamins, pp. 9–34. [Google Scholar]

- Bianchi, Valentina. 2001. On Person agreement. Unpublished manuscript, last modified 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Błaszczack, Joanna, Anastasia Giannakidou, Dorota Klimek–Jankowska, and Krzysztof Migdalski. 2016. Mood, Aspect, Modality Revisited: New Answers to Old Questions. Chicago: University of Chicago Press. [Google Scholar]

- Bookhamer, Kevin. 2013. The Variable Grammar of the Spanish Subjunctive in Second—Generation Bilinguals in New York City. Ph.D. dissertation, City University of New York (CUNY), New York, NY, USA. [Google Scholar]

- Bowles, Melissa. 2011. Measuring implicit and explicit linguistic knowledge: What can heritage language learners contribute? Studies in Second Language Acquisition 33: 247–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carando, Agustina. 2008. The Subjunctive in the Spanish of New York. New York: Graduate Center, CUNY, Unpublished manuscript. [Google Scholar]

- Chater, Nick, Alexander Clark, John Goldsmith, and Amy Perfors. 2015. Empiricism and Language Learnability. Oxford: Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Chater, Nick, Stewart McCauley, and Morten Christiansen. 2016. Language as skill: Intertwining comprehension and production. Journal of Memory and Language 89: 244–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Christiansen, Morten, and Nick Chater. 2016. Creating Language: Integrating Evolution, Acquisition, and Processing. Cambridge: MIT Press. [Google Scholar]

- Correa, Maite. 2011. Heritage Language Learners of Spanish: What role does metalinguistic knowledge play in their acquisition of the subjunctive? In Selected Proceedings of the 13th Hispanic Linguistics Symposium. Edited by Luis Ortiz-López. Somerville: Cascadilla Proceedings Project, pp. 128–38. [Google Scholar]

- Cuevas de Jesús, Elizabeth. 2011. La Adquisición del Subjuntivo Factivo-Emotivo en Niños Bilingües: ¿ Influencia Translingüística, Adquisición Incompleta o Retraso Lingüístico? Ph.D. dissertation, Universidad de Puerto Rico, San Juan, PR, USA. [Google Scholar]

- Cuza, Alejandro, and Rocio Pérez-Tattam. 2016. Grammatical gender selection and phrasal word order in child heritage Spanish: A feature reassembly approach. Bilingualism: Language and Cognition 19: 50–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cuza, Alejandro. 2013. Crosslinguistic influence at the syntax proper: Interrogative subject-verb inversion in heritage Spanish. International Journal of Bilingualism 17: 71–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dąbrowska, Ewa. 2012. Different speakers, different grammars: Individual differences in native language attainment. Linguistic Approaches to Bilingualism 2: 219–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dahl, Tove, Curt Rice, Marie Steffensen, and Ludmila Amundsen. 2010. Is it language relearning or language reacquisition? Hints from a young boy’s code-switching during his journal back to his native language. International Journal of Bilingualism 14: 490–510. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Carli, Fabrizio, Barbara Dessi, Manuela Mariani, Nicola Girtler, Alberto Greco, Guido Rodriguez, Laura Salmon, and Mara Morelli. 2015. Language use affects proficiency in Italian–Spanish bilinguals irrespective of age of second language acquisition. Bilingualism: Language and Cognition 18: 324–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dijkstra, Ton. 2005. Bilingual word recognition and lexical access. In Handbook of Bilingualism: Psycholinguistic Approaches. Edited by Judith Kroll and Annette De Groot. New York: Oxford University Press, pp. 179–201. [Google Scholar]

- Fábregas, Antonio. 2014. A guide to subjunctive and modals in Spanish: Questions and analyses. Borealis—An International Journal of Hispanic Linguistics 3: 1–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Favreau, Micheline, and Norman Segalowitz. 1983. Automatic and controlled processes in the first and second-language reading of fluent bilinguals. Memory and Cognition 11: 565–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Flores, Cristina. 2010. The effect of age on language attrition: Evidence from bilingual returnees. Bilingualism: Language and Cognition 13: 533–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Flores, Cristina. 2015. Losing a language in childhood: A longitudinal case study on language attrition. Journal of Child Language 42: 562–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Flores, Cristina. 2019. Attrition and reactivation of a childhood language: The case of returnee heritage speakers. Language Learning. Available online: https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/abs/10.1111/lang.12350. doi:10.111/lang.12350 (accessed on 9 October 2019).

- Gallego, Muriel, and Emilia Alonso-Marchs. 2014. Degrees of subjunctive vitality among monolingual speakers of Peninsular and Argentinian Spanish. Borealis–An International Journal of Hispanic Linguistics 3: 95–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Gershkoff-Stowe, Lisa, and Erin Hahn. 2013. Word comprehension and production asymmetries in children and adults. Journal of Experimental Child Psychology 114: 489–509. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giancaspro, David. 2017. Heritage Speakers’ Production and Comprehension of Lexically—and Contextually Selected Subjunctive Mood Morphology. Ph.D. dissertation, Rutgers University, New Brunswick, NJ, USA. [Google Scholar]

- Goldrick, Matthew, Michael Putnam, and Lara Schwarz. 2016a. Coactivation in bilingual grammars: A computational account of code mixing. Bilingualism: Language and Cognition 19: 857–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goldrick, Matthew, Michael Putnam, and Lara Schwarz. 2016b. The future of code mixing research: Integrating psycholinguistics and formal grammatical theories. Bilingualism: Language and Cognition 19: 903–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gollan, Tamar, Rosa Montoya, Cynthia Cera, and Tiffany C. Sandoval. 2008. More use almost always means a smaller frequency effect: Aging, bilingualism, and the weaker links hypothesis. Journal of Memory and Language 58: 787–814. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Goral, Mira, Erika Levy, Loraine Obler, and Eyal Cohen. 2006. Cross-language lexical connections in the mental lexicon: Evidence from a case of trilingual aphasia. Brain and Language 98: 235–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grimm, Angela, Anja Müller, Cornelia Hamann, and Esther Ruigendijk, eds. 2011. Production-Comprehension Asymmetries in Child Language. Berlin and Boston: De Gruyter Mouton. [Google Scholar]

- Grosjean, François. 2008. Studying Bilinguals. Oxford: Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Gudmestad, Aarnes. 2006. L2 variation and the Spanish subjunctive: Linguistic features predicting mood selection. In Selected Proceedings of the 7th Conference on the Acquisition of Spanish and Portuguese as First and Second Languages. Edited by Carol Klee and Tomothy Face. Somerville: Cascadilla Proceedings Project, pp. 170–84. [Google Scholar]

- Haverkate, Henk. 2002. The Syntax, Semantics, and Pragmatics of Spanish Mood. Amsterdam and Philadelphia: John Benjamins Publishing Co. [Google Scholar]

- Hendriks, Petra, and Charlotte Koster. 2010. Production/comprehension asymmetries in language acquisition. Lingua 120: 1887–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hendriks, Petra. 2014. Asymmetries between Language Production and Comprehension. Dordrecht: Springer. [Google Scholar]

- Hopp, Holger, and Michael Putnam. 2015. Syntactic restructuring in heritage grammars: Word order variation in Moundridge Schweitzer German. Linguistic Approaches to Bilingualism 5: 180–213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iverson, Michael, Paula Kempchinsky, and Jason Rothman. 2008. Interface vulnerability and knowledge of the subjunctive/indicative distinction with negated epistemic predicates in L2 Spanish. EUROSLA Yearbook 8: 135–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jakobson, Roman. 1959. Boas’ view of grammatical meaning. American Anthropologist 61: 170–78. [Google Scholar]

- Kempchinsky, Paula. 1986. Romance Subjunctive Clauses and Logical Form. Ph.D. dissertation, UCLA, Los Angeles, CA, USA. [Google Scholar]

- Kempchinsky, Paula. 2009. What can the subjunctive disjoint reference effect tell us about the subjunctive? Lingua 119: 1788–810. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kroll, Judith, and Ellen Bialystok. 2013. Understanding the consequences of bilingualism for language processing and cognition. Journal of Cognitive Psychology 25: 497–514. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Kroll, Judith, and Tamar Gollan. 2014. Speech planning in two languages: What bilinguals tell us about language production. In The Oxford Handbook of Language Production. Edited by Matthew Goldrick, Victor Ferreira and Michele Miozzo. Oxford: Oxford University Press, pp. 165–81. [Google Scholar]

- Kroll, Judith, Susan C. Bobb, and Noriko Hoshino. 2014. Two languages in mind: Bilingualism as a tool to investigate language, cognition, and the brain. Current Directions in Psychological Science 23: 159–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lardiere, Donna. 1998. Case and tense in the ‘fossilized’ steady state. Second Language Research 14: 1–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lardiere, Donna. 2000. Mapping features to forms in second language acquisition. Second Language Acquisition and Linguistic Theory 21: 102–29. [Google Scholar]

- Lardiere, Donna. 2005. On morphological competence. In Proceedings of the 7th Generative Approaches to Second Language Acquisition Conference (GASLA 2004). Edited by Laurent Dekydtspotter, Rex Sprouse and Audrey Liljestrand. Somerville: Cascadilla Proceedings Project, pp. 178–92. [Google Scholar]

- Leal, Tania, Jason Rothman, and Roumyana Slabakova. 2014. A rare structure at the syntax-discourse interface: Heritage and Spanish-dominant native speakers weigh in. Language Acquisition 21: 411–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Legendre, Géraldine, Miyata Yoshiro, and Paul Smolensky. 1990. Harmonic Grammar. A formal multi-level connectionist theory of linguistic well-formedness: Theoretical foundations. In Proceedings of the Twelfth Annual Conference of the Cognitive Science Society. Cambridge: Lawrence Erlbaum, pp. 388–95. [Google Scholar]

- Lidz, Jeffrey, and Annie Gagliardi. 2015. How nature meets nurture: Universal grammar and statistical learning. Annu. Rev. Linguist 1: 333–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lim, Hyojung, and Aline Godfroid. 2015. Automatization in second language sentence processing: A partial, conceptual replication of Hulstijn, Van Gelderen, and Schoonen's 2009 study. Applied Psycholinguistics 36: 1247–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Litcofsky, Kaitlyn, Tanner Darren, and Janet van Hell. 2016. Effects of language experience, use, and cognitive functioning on bilingual word production and comprehension. International Journal of Bilingualism 20: 666–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- López-Otero, Julio. 2018. On the Acceptability of the Spanish DOM among Romanian-Spanish Bilinguals. Master’s thesis, Rutgers University, New Brunswick, NJ, USA. [Google Scholar]

- MacWhinney, Brian. 2015. The Handbook of Language Emergence. Edited by Brian MacWhinney and William O’Grady. Hoboken: John Wiley and Sons, pp. 1–31. [Google Scholar]

- Marian, Viorica, and Michael Spivey. 2003. Competing activation in bilingual language processing: Within—and between-language competition. Bilingualism: Language and Cognition 6: 97–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martinez-Mira, Maria Isabel. 2006. Mood Simplification: Adverbial Clauses in Heritage Spanish. Ph.D. dissertation, University of Illinois at Urbana, Champaign, IL, USA. [Google Scholar]

- Martinez-Mira, Maria Isabel. 2009a. Position and the presence of subjunctive in purpose clauses in US-heritage Spanish. Sociolinguistic Studies 3: 61–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martinez-Mira, Maria Isabel. 2009b. Spanish heritage speakers in the southwest: Factors contributing to the maintenance of the subjunctive in concessive clauses. Spanish in Context 6: 105–26. [Google Scholar]

- McCarthy, John, and Joe Pater, eds. 2016. Harmonic Grammar and Harmonic Serialism. London: Equinox. [Google Scholar]

- McDonald, Janet. 2000. Grammaticality judgments in a second language: Influences of age of acquisition and native language. Applied psycholinguistics 21: 395–423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mikulski, Ariana. 2006. Native Intuitions, Foreign Struggles? Knowledge of the Subjunctive in Volitional Constructions among Heritage and Traditional FL Learners of Spanish. Ph.D. dissertation, University of Iowa, Iowa City, IA, USA. [Google Scholar]

- Mikulski, Ariana. 2010. Receptive volitional subjunctive abilities in heritage and traditional FL learners of Spanish. Modern Language Journal 94: 217–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Montrul, Silvina. 2007. Interpreting mood distinctions in Spanish as a heritage language. In Spanish in Contact: Policy, Social and Linguistic Inquiries. Edited by Kim Potowski and Richard Cameron. Amsterdam: John Benjamins, pp. 23–40. [Google Scholar]

- Montrul, Silvina. 2008. Incomplete Acquisition in Bilingualism: Re-Examining the Age Factor. Amsterdam: John Benjamins. [Google Scholar]

- Montrul, Silvina. 2009. Incomplete acquisition of tense-aspect and mood in Spanish heritage speakers. The International Journal of Bilingualism 13: 239–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Montrul, Silvina. 2011. Morphological errors in Spanish second language learners and heritage speakers. Studies in Second Language Acquisition 33: 163–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Montrul, Silvina. 2012. Is the heritage language like a second language? Eurosla Yearbook 12: 1–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Montrul, Silvina. 2016. The Acquisition of Heritage Languages. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Montrul, Silvina. 2018. The Bottleneck Hypothesis extends to heritage language acquisition. In Meaning and Structure in Second Language Acquisition: In honor of Roumyana Slabakova. Edited by Jacee Choo, Michael Iverson, Tiffany Judy, Tania Leal and Elena Shimanskaya. Amsterdam: John Benjamins, pp. 149–77. [Google Scholar]

- Morales, Amparo. 1999. Anteposición de sujeto en el español del Caribe. In El Caribe hispánico: Perspectivas Lingüísticas Actuales: Homenaje a Manuel Alvarez Nazario. Edited by Luis Ortiz López. Frankfurt am Main: Vervuert, pp. 77–98. [Google Scholar]

- Mucha, Anne, and Malte Zimmermann. 2016. TAM coding and temporal interpretation in West African languages. In Mood, Aspect, Modality Revisited: New Answers to Old Questions. Edited by Joanna Błaszczack, Anastasia Giannakidou, Dorota Klimek-Jankowska and Krzysztof Migdalski. Chicago: University of Chicago Press, pp. 6–45. [Google Scholar]

- Ojea, Ana. 2005. A syntactic approach to logical modality. Atlantis 27: 53–64. [Google Scholar]

- Ojea, Ana. 2008. A Feature Analysis of to-infinitive Sentences. Atlantis 30: 69–83. [Google Scholar]

- Orfitelli, Robyn, and Maria Polinsky. 2017. When performance masquerades as comprehension. In Quantitative Approaches to the Russian Language. Edited by Mikhail Kopotev, Olga Lyashevskaya and Arto Mustajoki. London: Routledge, pp. 197–211. [Google Scholar]

- Paradis, Michel. 1985. On the representation of two languages in one brain. Language Sciences 7: 1–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paradis, Michel. 1993. Linguistic, psycholinguistic, and neurolinguistic aspects of “interference” in bilingual speakers: The activation threshold hypothesis. International Journal of Psycholinguistics 9: 133–45. [Google Scholar]

- Pascual y Cabo, Diego, Anne Lingwall, and Jason Rothman. 2012. Applying the Interface Hypothesis to Heritage Speaker Acquisition: Evidence from Spanish Mood. In BUCLD 36: Proceedings of the 36th Annual Boston University Conference on Language Development. Edited by Alia Biller, Esther Chung and Amelia Kimball. Somerville: Cascadilla Proceedings Project, pp. 437–48. [Google Scholar]

- Pater, Joe. 2009. Weighted constraints in generative linguistics. Cognitive Science 33: 999–1035. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perez-Cortes, Silvia. 2016. Acquiring Obligatory and Variable Mood Selection: Spanish Heritage Speakers and L2 Learners' Performance in Desideratives and Reported Speech Contexts. Ph.D. dissertation, Rutgers University, New Brunswick, NJ, USA. [Google Scholar]

- Pérez-Tattam, Rocio. 2006. Control in L2 English and Spanish: More on grammar at the syntax-semantic interface. Cahiers Linguistiques d’Ottawa/Ottawa Papers in Linguistics 34: 99–108. [Google Scholar]

- Picallo, Carme. 1984. The Infl Node and the Null Subject Parameter’. Linguistic Inquiry 15: 75–102. [Google Scholar]

- Pierce, Lara, Denise Klein, Jen-Kai Chen, Audrey Delcenserie, and Fred Genesee. 2014. Mapping the unconscious maintenance of a lost first language. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences USA 111: 17314–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Polinsky, Maria. 2011. Reanalysis in adult heritage language. Studies in Second Language Acquisition 33: 305–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Polinsky, Maria. 2018. Heritage Languages and Their Speakers. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Polinsky, Maria, and Greg Scontras. 2019. Understanding heritage languages. Bilingualism: Language and Cognition. Available online: https://doi.org/10.1017/S1366728919000245 (accessed on 9 October 2019).

- Putnam, Michael, and Robert Klosinski. 2019. The good, the bad, and the gradient: The role of losers in code-switching. Linguistic Approaches to Bilingualism. Available online: https://doi.org/10.1075/lab.16008.put (accessed on 9 October 2019).

- Putnam, Michael, and Joseph Salmons. 2013. Losing their (passive) voice: Syntactic neutralization in heritage German. Linguistic Approaches to Bilingualism 3: 233–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Putnam, Michael, and Liliana Sánchez. 2013. How incomplete is incomplete acquisition? - A prolegomenon for modeling heritage grammars. Linguistic Approaches to Bilingualism 3: 478–508. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Putnam, Michael, Matthew Carlson, and David Reitter. 2018. Integrated, not isolated: Defining typological proximity in an integrated multilingual architecture. Frontiers in Psychology 8: 2212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Putnam, Michael, Silvia Perez-Cortes, and Liliana Sánchez. 2019. Language attrition and the Feature Reassembly Hypothesis. In The Oxford Handbook of Language Attrition. Edited by Barbara Köpke and Monika Schmid. Oxford: Oxford University Press, pp. 18–24. [Google Scholar]

- Quer, Joan. 2001. Interpreting mood. Probus 13: 81–111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Quer, Joan. 2009. Twists of mood: The distribution and interpretation of indicative and subjunctive. Lingua 119: 1779–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rinke, Esther, and Cristina Flores. 2014. Morphosyntactic knowledge of clitics by Portuguese heritage bilinguals. Bilingualism: Language and Cognition 17: 681–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ritter, Elizabeth, and Martina Wiltschko. 2004. The lack of tense as a syntactic category: Evidence from Blackfoot and Halkomelem. In Papers from the 39th International Conference on Salish and Neighboring Languages. Working Papers in Linguistics 14. Edited by Jason Brown and Tyler Peterson. Vancouver: University of British Columbia, pp. 341–70. [Google Scholar]

- Roncaglia-Denissen, Paula, and Sonja Kotz. 2015. What does neuroimaging tell us about morphosyntactic processing in the brain of second language learners? Bilingualism, Language and Cognition 19: 665–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rothman, Jason. 2009. Understanding the nature and outcomes of early bilingualism: Romance languages as heritage languages. International Journal of Bilingualism 13: 155–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rothman, Jason, and Jeanine Treffers-Daller. 2014. A prolegomenon to the construct of the native speaker: Heritage speaker bilinguals are natives too! Applied Linguistics 35: 93–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sánchez, Liliana. 2003. Quechua-Spanish Bilingualism: Interference and Convergence in Functional Categories. Amsterdam: John Benjamins, vol. 35. [Google Scholar]

- Sánchez, Liliana. 2004. Functional convergence in the tense, evidentiality and aspectual systems of Quechua Spanish bilinguals. Bilingualism: Language and Cognition 7: 147–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sánchez, Liliana. Forthcoming. Bilingual Alignments. In Special Issue Bilingualism in the Hispanic and Lusophone World (BHL): Current Issues in Spanish and Portuguese Bilingual Settings. Edited by Eduardo Alves Vieira, Antje Muntendam and M. Carmen Parafita Couto. Languages.

- Scontras, Gregory, Maria Polinsky, and Zusanna Fuchs. 2018. In support of representational economy: Agreement in heritage Spanish. Glossa: A Journal of General Linguistics 3: 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scontras, Gregory, Zuzanna Fuchs, and Maria Polinsky. 2015. Heritage language and linguistic theory. Frontiers in Psychology 6: 1545. Available online: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fpsyg.2015.01545/full (accessed on 9 October 2019). [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Segalowitz, Norman, and Elizabeth Gatbonton. 1995. Automaticity and lexical skills in second language fluency: Implications for computer assisted language learning. Computer Assisted Language Learning 8: 129–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Segalowitz, Norman, and Jan Hulstijn. 2005. Automaticity in second language learning. In Handbook of Bilingualism: Psycholinguistic Approaches. Edited by Judy Kroll and Annette De Groot. Oxford: Oxford University Press, pp. 371–88. [Google Scholar]

- Segalowitz, Sidney, Norman Segalowitz, and Anthony Wood. 1998. Assessing the development of automaticity in second language word recognition. Applied Psycholinguistics 19: 53–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Serrano, María José. 2004. Entre la gramática y el discurso: Las completivas con para + infinitivo/subjuntivo en un contexto socio-comunicativo. Estudios de Sociolingüística 5: 129–50. (In Spanish). [Google Scholar]

- Sherkina-Lieber, Marina. 2011. Comprehension of Labrador Inuttitut Functional Morphology by Receptive Bilinguals. Ph.D. dissertation, University of Toronto, Toronto, ON, USA. [Google Scholar]

- Sherkina-Lieber, Marina. 2015. Tense, aspect, and agreement in heritage Labrador Inuttitut: Do receptive bilinguals understand functional morphology? Linguistic Approaches to Bilingualism 5: 30–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silva-Corvalán, Carmen. 1994. Language Contact and Change. Oxford: Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Slabakova, Roumyana. 2008. Meaning in the Second Language. Berlin: Mouton de Gruyter. [Google Scholar]

- Smolensky, Paul, Matthew Goldrick, and Donald Mathis. 2014. Optimization and quantization in gradient symbol systems: A framework for integrating the continuous and the discrete in cognition. Cognitive Science 38: 1102–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sunderman, Gretchen, and Judith Kroll. 2006. First language activation during second language lexical processing: An investigation of lexical form, meaning, and grammatical class. Studies in Second Language Acquisition 28: 387–422. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Torres, Lourdes. 1989. Mood selection among New York Puerto Ricans. International Journal of the Sociology of Language 79: 67–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van Gelderen, Elly. 2001. The Force of ForceP in English. South West Journal of Linguistics 20: 107–20. [Google Scholar]

- Van Heuven, Walter, Herbert Schriefers, Ton Dijkstra, and Peter Hagoort. 2008. Language conflict in the bilingual brain. Cerebral Cortex 18: 2706–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- von Fintel, Kai, and Lisa Matthewson. 2008. Universals in semantics. The Linguistic Review 25: 139–201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wartenburger, Isabell, Hauke Heekeren, Jubin Abutalebi, Stefano Cappa, Arno Villringer, and Daniela Perani. 2003. Early setting of grammatical processing in the bilingual brain. Neuron 37: 159–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yager, Lisa, Nora Hellmold, Hyoun-A. Joo, Michael T. Putnam, Eleonora Rossi, Catherine Stafford, and Joseph Salmons. 2015. New structural patterns in moribund grammar: Case marking in Heritage German. Available online: https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2015.01716 (accessed on 9 October 2019).

| 1 | The term “relative weight” refers to the relationship between activation and strength of representation in the mind of a bi/multilingual. |

| 2 | Probabilistic models such as Emergent Grammars (MacWhinney 2015), Harmonic Grammar (HG; Legendre et al. 1990; Pater 2009; McCarthy and Pater 2016) and Gradient Symbolic Computation (GSC; Goldrick et al. 2016a, 2016b; Putnam and Klosinski 2019; Smolensky et al. 2014) also acknowledge that the connections between linguistic representations and their various interpretive interfaces are gradient rather than discrete (see also Christiansen and Chater’s (2016) Chunk-and-Pass model), forcing the inevitable restructuring—at least to some degree of linguistic representations. |

| 3 | (Sánchez Forthcoming) proposes the notion of “alignment” as a matrix of features from different language components across languages that emerges as a unit of memory storage. |

| 4 | An Anonymous reviewer asked for clarification on how our model differs from others that account for the fact that some structures are never learned by child heritage bilinguals. In our model, divergence in heritage grammars is not necessarily indicative of restructuring, incomplete acquisition, or attrition, but rather of differential access. The model focuses on comprehension-production mismatches that other models might have previously attributed to other processes. However, we do not believe our proposal is incompatible with the idea that some structures may have not been acquired due to a decreased exposure to the HL during childhood. |

| 5 | While the effects of frequency of language use will not be explored in this article, they can, in principle, be incorporated into the model as factors that further modulate HS’ access. See Perez-Cortes (2016, pp. 251–59) for more details. |

| 6 | For more details about the control group, please refer to Perez-Cortes (2016, pp. 101–3). |

| 7 | As pointed out by one of the reviewers, we agree that the modality of the experimental tasks—written instead of aural—as well as the degree of metalinguistic awareness involved in their completion could have affected the processing patterns of heritage speaker group (Bowles 2011; Montrul 2012). While we acknowledge that these factors might have negatively impacted their performance, especially in the case of the AJT, which involves a high level of metalinguistic awareness, we would like to argue that the triangulation of 3 types of data (judgments, interpretation and production) allowed for an understanding of HS’ grammatical representations as well as potential locus of variability that would have otherwise been overlooked. |

| 8 | The data reported in this article focus on half of the structures originally tested by Perez-Cortes (2016). Out of the 64 sentences mentioned in the text, only 12 tested participants’ interpretation of disjoint reference (6 items) as well as co-referential (6 items) desideratives. For more information on Anonymous’ methodology, see (Perez-Cortes 2016, pp. 109–20). |

| 9 | Out of the total, only 10 scenarios were designed to elicit the production of disjoint reference and co-referential desideratives (five items per structure). |

| 10 | As observed in the example provided in (9), the researcher opted to leave out the complementizer que (“that”) from the target sentences in order to allow for a wider and more informative range of responses. |

| 11 | Sociolinguistic research focused on the interpretation and production of these sentences in Spanish monolinguals report that there is a percentage of this population who tends to hypercorrect subjunctive forms in disjoint reference contexts by overextending infinitival forms (Gallego and Alonso-Marchs 2014), although the opposite trend, that is, the overuse of subjunctive in similar contexts, has also been documented (Morales 1999; Serrano 2004). |

| 12 | This type of divergence, which is a grammatical option in Spanish, involved the simplification of a disjoint reference desiderative (i) into an infinitival construction (ii), used to express co-referential readings. As pointed out by Perez-Cortes (2016), this structural change might be the result of a semantic re-interpretation of the context, although this may not always be the case—see alternative glosses for example (ii):

|

| 13 | This is the case, for example, of low proficiency HS, whose low rates of production of ungrammatical querer que + infinitive (8.2%) contrast with the high levels of acceptance reported in the AJT (almost a 98% of these structures were deemed grammatical). |

| 14 | These constructions—ungrammatical in Spanish but possible in English—would involve the reproduction of a specific type of ECM-constructions used in English to express disjoint readings. They would replicate the structure provided below:

|

| 15 | See however Hendriks (2014) and Polinsky (2018, Section 3.2.2) for a discussion of instances where deviations in heritage language comprehension antecede those observed in production. |

| Group | N | Mean Score (Range) | SD |

|---|---|---|---|

| Advanced | 31 | 85% (95–79.5%) | 6.6 |

| Intermediate | 23 | 68% (77–61%) | 5.4 |

| Low | 15 | 47% (56–36%) | 6.6 |

| Groups | Context | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Disjoint Reference (Querer que+ Subjunctive) | Co-Referential (Querer+ Infinitive) | |||

| Interpretation | Production | Interpretation | Production | |

| Controls | 88% | 87.5% | 85.3% | 90.6% |

| Advanced HS | 83% | 84.7% | 77.7% | 94.3% |

| Intermediate HS | 80.8% | 55.7% | 74.3% | 87.8% |

| Low HS | 64.4% | 18.7% | 54.4% | 81.3% |

| Group | *Querer que + Indicative | *Querer que + Infinitive |

|---|---|---|

| Controls | 100% | 100% |

| Advanced | 83% | 91% |

| Intermediate | 53.3% | 60% |

| Low | 10.3% | 2.6% |

| Interpretation (TVJT) * | Production (PBSCT) | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Level | ID | Stage 0 ** | Stage 1 | Stage 2 | Stage 3 | Stage 0 | Stage 1 | Stage 2 | Stage 3 |

| Interm. | HS026 | X (100%/100%) | X (100% querer que + subj.) | ||||||

| HS040 | X (100%/100%) | X (80% querer que + ind.) | |||||||

| HS007 | X (67%/50%) | X (60% querer que+ ind.; 40% querer que+ inf.) | |||||||

| Low | HS064 | X (83.3%/83.3%) | X (60% querer que+subj.; 40% querer que+ind.) | ||||||

| HS027 | X (50%/33.3%) | X (60% querer que+ inf.; 40% Op. control | |||||||

| HS025 | X (50%/33.3%) | X (80% Op. control; 20% querer que+ ind.) | |||||||

© 2019 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Perez-Cortes, S.; Putnam, M.T.; Sánchez, L. Differential Access: Asymmetries in Accessing Features and Building Representations in Heritage Language Grammars. Languages 2019, 4, 81. https://doi.org/10.3390/languages4040081

Perez-Cortes S, Putnam MT, Sánchez L. Differential Access: Asymmetries in Accessing Features and Building Representations in Heritage Language Grammars. Languages. 2019; 4(4):81. https://doi.org/10.3390/languages4040081

Chicago/Turabian StylePerez-Cortes, Silvia, Michael T. Putnam, and Liliana Sánchez. 2019. "Differential Access: Asymmetries in Accessing Features and Building Representations in Heritage Language Grammars" Languages 4, no. 4: 81. https://doi.org/10.3390/languages4040081

APA StylePerez-Cortes, S., Putnam, M. T., & Sánchez, L. (2019). Differential Access: Asymmetries in Accessing Features and Building Representations in Heritage Language Grammars. Languages, 4(4), 81. https://doi.org/10.3390/languages4040081