Education and Input as Predictors of Second Language Attainment in Naturalistic Contexts

Abstract

1. Introduction

- -

- adding the prefix e- (added to monosyllabic stems beginning with a consonant);

- -

- a stem change (f > p);

- -

- insertion of the suffix -s-;

- -

- addition of the first person singular perfective past tense ending -a.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Participants

2.2. Instruments

2.2.1. Agreement Tasks

2.2.2. Spontaneous Speech

2.2.3. Past Tense Production Task

2.3. Procedure

2.4. Data Coding

- Pauses to fluent speech ratio: this is a measure of fluency computed by dividing the number of pauses by the number of fluent segments and multiplying by 100. A fluent segment was defined as intonational unit.

- Speech rate: this was a second measure of fluency and was computed by dividing the total number of words by the total speech time in seconds and multiplying the result by 60 (Grosjean 1980; in Götz 2013), which yields the mean number of words per minute.

- Mean length of T-unit (MLTU): this is a global measure of syntactic complexity. A ‘Terminable unit’ (T-unit) is a unit consisting of an independent clause and any subordinate clauses or non-finite fragments that are attached to it (Hunt 1970; Götz 2013). Thus, the utterance I started learning English when I was 11 consists of one T-unit, while I am supposed to meet my friends this evening but the weather is very bad consists of two T-units. MLTU, the mean length of a T-unit in words, is widely used as a measure of syntactic complexity beyond the preschool years (see, for example, Götz 2013; Nippold et al. 2005; Scott 1988).

- Clausal density (also known as subordination index): this measures the amount of subordination in a sample. It is computed by dividing the number of clauses by the number of T-units (Götz 2013; Nippold et al. 2005; Scott 1988).

- Type to token ratio (TTR): this is a widely used measure of lexical diversity computed by dividing the number of word types in the sample by the number of word tokens (Johansson 2008). A higher ratio means that fewer word types are repeated, and hence that the sample is more lexically diverse.

- Lexical density: this measures the density of information. It is calculated by dividing the number of content words by the total number of words and multiplying the result by 100.

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Descriptives

3.2. Regression Analyses

4. General Discussion and Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A. Stimuli Used in the Agreement Tasks

| Masculine | Feminine | Neuter |

|---|---|---|

| O prásin-os vátrah-os ‘The green frog’ | I kókin-i bál-a ‘The red ball’ | To kókin-o louloúð-i ‘The red flower’ |

| O kítrin-os solín-as ‘The yellow pipe’ | I prásin-i bloúz-a ‘The green blouse’ | To kókin-o spít-i ‘The red house’ |

| O kókin-os píravl-os ‘The red rocket’ | I kítrin-i vrís-i ‘The yellow tap’ | To prásin-o tiléfon-o ‘The green telephone’ |

| O kítrin-os niptír-as ‘The yellow sink’ | I prásin-i klost-í ‘The green thread’ | To kítrin-o piát-o ‘The yellow dish’ |

| Masculine | Feminine | Neuter |

|---|---|---|

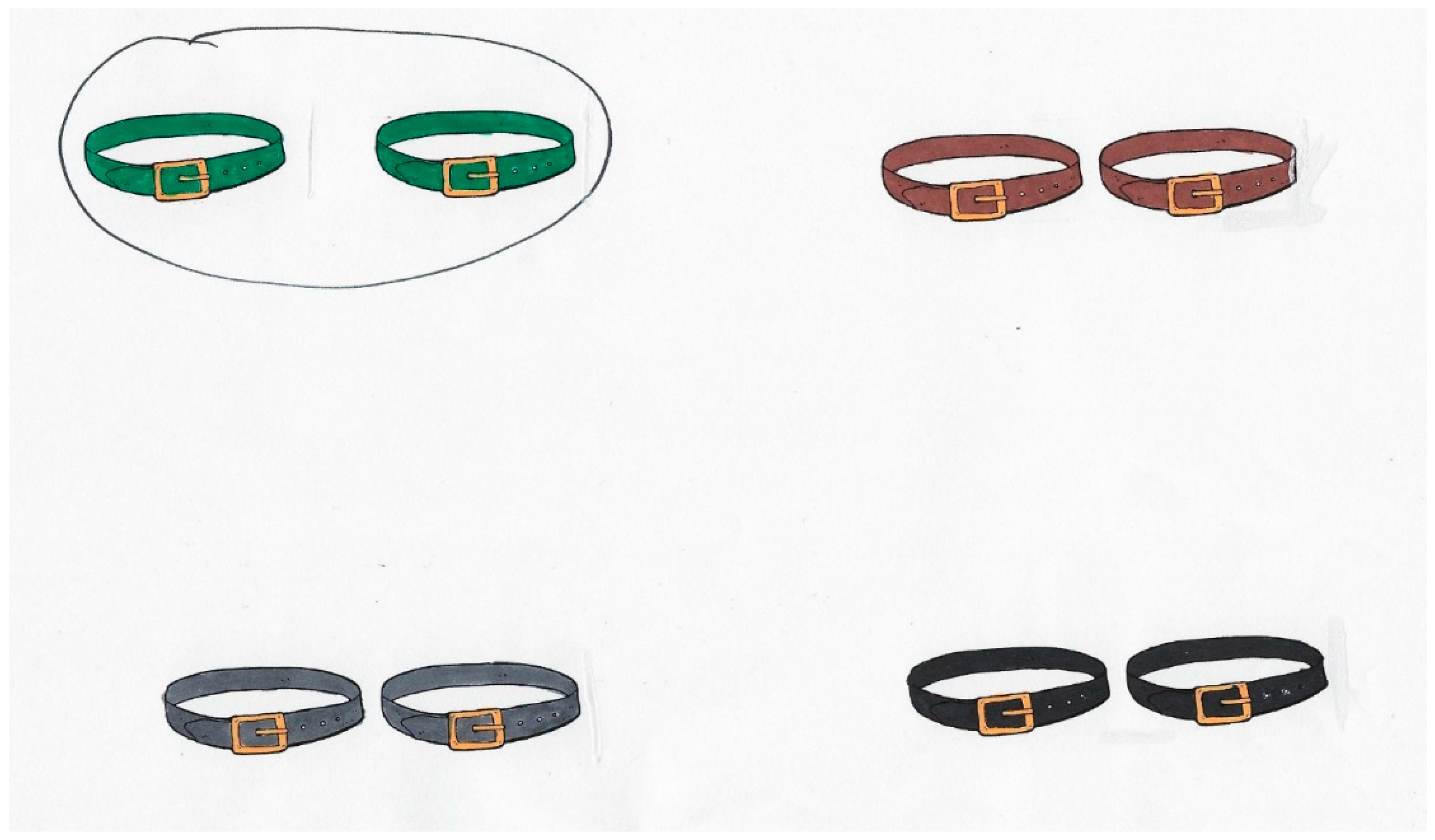

| O kókin-os káð-os ‘The red bin’ | I prásin-i zón-i ‘The green belt’ | To kókin-o balón-i ‘The red balloon’ |

| O prásin-os pínak-as ‘The green board’ | I kókin-i vivlioθíq-i ‘The red bookcase’ | To kókin-o vivlí-o ‘The red book’ |

| O kítrin-os kouv-ás ‘The yellow bucket’ | I prásin-i katsaról-a ‘The green pot’ | To prásin-o ktíri-o ‘The green building’ |

| O kítrin-os fáqel-os ‘The yellow envelope’ | I prásini karékl-a ‘The green chair’ | To kókin-o ráf-i ‘The red shelf’ |

| O kókin-os anaptír-as ‘The red lighter’ | I kókin-i pórt-a ‘The red door’ | To kítrin-o poukámis-o ‘The yellow shirt’ |

| O kítrin-os hárak-as ‘The yellow ruler’ | I kítrin-i lekán-i ‘The yellow toilet seat’ | To prásin-o trapéz-i ‘The green table’ |

| O kítrin-os íli-os ‘The yellow sun’ | I prásin-i tileóras-i ‘The green television’ | To kítrin-o pandelón-i ‘The yellow trousers’ |

| O kítrin-os tíh-os ‘The yellow wall’ | I prásin-i ombrél-a ‘The green umbrella’ | To kókin-o paráθir-o ‘The red window’ |

| Masculine | Feminine | Neuter |

|---|---|---|

| i prásin-i vátrah-i ‘The green frogs’ | i kókin-es bál-es ‘The red balls’ | Ta kókin-a louloúði-a ‘The red flowers’ |

| i kítrin-i solín-es ‘The yellow pipes’ | i prásin-es bloúz-es ‘The green blouses’ | Ta kókin-a spíti-a ‘The red houses’ |

| i kókin-i píravl-i ‘The red rockets’ | i kítrin-es vrís-es ‘The yellow taps’ | Ta prásin-a tiléfon-a ‘The green telephones’ |

| i kítrin-i niptír-es ‘The yellow sinks’ | i prásin-es klost-és ‘The green threads’ | Ta kítrin-a piát-a ‘The yellow dishes’ |

| Masculine | Feminine | Neuter |

|---|---|---|

| i kókin-i káð-i ‘The red bins’ | I prásin-es zón-es ‘The green belts’ | Ta kókin-a balón-ia ‘The red balloons’ |

| i prásin-i pínak-es ‘The green boards’ | I kókin-es vivlioθíq-es ‘The red bookcases’ | Ta kókin-a vivlí-a ‘The red books’ |

| i kítrin-i kouv-áðes ‘The yellow buckets’ | I prásin-es katsaról-es ‘The green pots’ | Ta prásin-a ktíri-a ‘The green buildings’ |

| i kítrin-i fáqel-i ‘The yellow envelopes’ | I prásines karékl-es ‘The green chairs’ | Ta kókin-a ráf-ia ‘The red shelves’ |

| i kókin-i anaptír-es ‘The red lighters’ | I kókin-es pórt-es ‘The red doors’ | Ta kítrin-a poukámis-a ‘The yellow shirts’ |

| i kítrin-i hárak-es ‘The yellow rulers’ | I kítrin-es lekán-es ‘The yellow toilet seats’ | Ta prásin-a trapéz-ia ‘The green tables’ |

| i kítrin-i íli-i ‘The yellow suns’ | I prásin-es tileorás-is ‘The green televisions’ | Ta kítrin-a pandelón-ia ‘The yellow trousers’ |

| i kítrin-i tíh-i ‘The yellow walls’ | I prásin-es ombrél-es ‘The green umbrellas’ | Ta kókin-a paráθir-a ‘The red windows’ |

Appendix B. Stimuli Used in the Past Tense Task

Appendix C. Regression Models for the Linguistic Variables

| Variable | B | SE B | β | t Value | Pr(>|t|) | lmg |

| Intercept | 0.098 | 0.330 | 0.031 | 0.297 | 0.768 | |

| Education | 0.083 | 0.035 | 0.141 | 2.377 | 0.022 | 0.024 |

| LoR | 0.034 | 0.016 | 0.015 | 2.145 | 0.037 | 0.001 |

| Education × LoR | −0.004 | 0.002 | −0.310 | −2.190 | 0.034 | 0.094 |

| Model R2 | 0.120 |

| Variable | B | SE B | β | t Value | Pr(>|t|) | lmg |

| Intercept | 0.560 | 0.082 | 0.000 | 6.829 | <0.001 | |

| Education | 0.024 | 0.008 | 0.387 | 2.877 | 0.006 | 0.150 |

| Model R2 | 0.150 |

| Variable | B | SE B | β | t Value | Pr(>|t|) | lmg |

| Intercept | 0.096 | 0.105 | 0.000 | 0.910 | 0.369 | |

| Education | 0.049 | 0.011 | 0.553 | 4.549 | <0.001 | 0.306 |

| Model R2 | 0.306 |

| Variable | B | SE B | β | t Value | Pr(>|t|) | lmg |

| Intercept | −0.155 | 0.104 | 0.000 | −1.491 | 0.143 | |

| Education | 0.058 | 0.010 | 0.619 | 5.399 | <0.001 | 0.383 |

| Model R2 | 0.383 |

| Variable | B | SE B | β | t Value | Pr(>|t|) | lmg |

| Intercept | −0.194 | 0.083 | 0.000 | −2.327 | 0.024 | |

| Education | 0.046 | 0.009 | 0.616 | 5.358 | <0.001 | 0.379 |

| Model R2 | 0.379 |

| Variable | B | SE B | β | t Value | Pr(>|t|) | lmg |

| Intercept | 47.346 | 3.631 | 0.003 | 12.039 | <0.001 | |

| LoR | 0.338 | 0.171 | −0.277 | 1.973 | 0.0546 | 0.080 |

| Model R2 | 0.080 |

| Variable | B | SE B | β | t Value | Pr(>|t|) | lmg |

| Intercept | 42.488 | 4.188 | 0.005 | 10.144 | <0.001 | |

| LoR | 0.629 | 0.198 | 0.421 | 3.185 | 0.003 | 0.184 |

| Model R2 | 0.184 |

| Variable | B | SE B | β | t Value | Pr(>|t|) | lmg |

| Intercept | 14.803 | 6.338 | −0.033 | 2.235 | 0.024 | |

| Education | −1.067 | 0.670 | 0.274 | −1.592 | 0.119 | |

| LoR | −0.422 | 0.306 | 0.257 | −1.380 | 0.175 | |

| Education × LoR | 0.066 | 0.032 | 0.275 | 2.069 | 0.045 | |

| Model R2 | 0.223 |

| Variable | B | SE B | β | t Value | Pr(>|t|) | lmg |

| Intercept | 0.896 | 0.122 | 0.004 | 7.291 | <0.001 | |

| LoR | 0.016 | 0.006 | 0.367 | 2.707 | 0.010 | 0.140 |

| Model R2 | 0.140 |

| Variable | B | SE B | β | t Value | Pr(>|t|) | lmg |

| Intercept | 22.430 | 24.508 | 0.024 | 0.915 | .365 | |

| Education | 6.359 | 2.590 | 0.334 | 2.455 | .018 | |

| LoR | 1.998 | 1.184 | −0.780 | 1.688 | 0.099 | |

| Education × LoR | −0.241 | 0.124 | 0.136 | −1.945 | 0.058 | |

| Model R2 | 0.196 |

| Variable | B | SE B | β | t Value | Pr(>|t|) | lmg |

| Intercept | 21.752 | 4.898 | −0.007 | 4.441 | <0.001 | |

| Education | 1/001 | 0.303 | 0.422 | 4.301 | 0.002 | |

| LoR | 0.365 | 0.203 | 0.230 | 1.804 | 0.078 | |

| Model R2 | 0.260 |

References

- Adrián, José Antonio, Jesus Alegria, and José Morais. 1995. Metaphonological Abilities of Spanish Illiterate Adults. International Journal of Psychology 30: 329–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Becker, Angelika, Norbert Dittmar, Margit Gutmann, Wolfgang Klein, BO Rieck, Gunter Senft, Ingeborg Senft, Wolfram Steckner, and Elisabeth Thielicke. 1977. Heidelberger Forschungsprojekt’Pidgin-Deutsch Spanischer Und Italienischer Arbeiter in Der Bundesrepublik’: Die Ungesteuerte Erlernung Des Deutschen Durch Spanische Und Italienische Arbeiter; Eine Soziolinguistische Untersuchung. Osnabrücker Beiträge Zur Sprachtheorie, Beihefte 2. Osnabrück: Universität Osnabrück. [Google Scholar]

- Birdsong, David. 2006. Age and Second Language Acquisition and Processing. A Selective Overview. Language Learning 56: 9–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Birdsong, David, and Michelle Molis. 2001. On the Evidence for Maturational Constraints in Second Language Acquisition. Journal of Memory and Language 44: 235–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Castro-Caldas, Alexandre, Karl Magnus Petersson, Alexandra Reis, Sharon Stone-Elander, and Martin Ingvar. 1998. The Illiterate Brain. Learning to Read and Write during Childhood Influences the Functional Organization of the Adult Brain. Brain: A Journal of Neurology 121: 1053–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Clahsen, Harald. 1980. Psycholinguistic Aspects of L2 Acquisition: Word order phenomena in foreign workers’ interlanguage. In Second Language Development: Trends and Issues. Edited by Sascha W. Felix. Tübingen: Narr-Verlag, pp. 57–79. [Google Scholar]

- Clahsen, Harald. 1984. The Acquisition of German Word Order: A Test Case for Cognitive Approaches to Second Language Development. In Second Languages: A Cross-Linguistic Perspective. Edited by Roger Andersen. Rowley: Newbury House, pp. 219–42. [Google Scholar]

- Clahsen, Harald, Jürgen M. Meisel, and Manfred Pienemann. 1983. Deutsch Als Zweitsprache: Der Spracherwerb Ausländischer Arbeiter. Tubingen: Narr, vol. 3. [Google Scholar]

- Clahsen, Harald, Maria Martzoukou, and Stavroula Stavrakaki. 2010. The Perfective Past Tense in Greek as a Second Language. Second Language Research 26: 501–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dąbrowska, Ewa. Forthcoming. How Writing Changes Language. In Language Change: The Impact of English as a Lingua Franca. Edited by Anna Mauranen and Svetlana Vetchinnikova. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- DeKeyser, Robert, Iris Alfi-Shabtay, and Dorit Ravid. 2010. Cross-Linguistic Evidence for the Nature of Age Effects in Second Language Acquisition. Applied Psycholinguistics 31: 413–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dellatolas, Georges, Lucia Willadino Braga, Ligia Do Nascimento Souza, Gilberto Nunes Filho, Elizabeth Queiroz, and Gerard Deloche. 2003. Cognitive Consequences of Early Phase of Literacy. Journal of the International Neuropsychological Society 9: 771–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Diamanti, Vassiliki, Argyro Benaki, Angeliki Mouzaki, Asimina Ralli, Faye Antoniou, Sophia Papaioannou, and Athanassios Protopapas. 2018. Development of Early Morphological Awareness in Greek: Epilinguistic versus Metalinguistic and Inflectional versus Derivational Awareness. Applied Psycholinguistics 39: 545–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duncan, Lynne G., Séverine Casalis, and Pascale Colé. 2009. Early Metalinguistic Awareness of Derivational Morphology: Observations from a Comparison of English and French. Applied Psycholinguistics 30: 405–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Flege, James Emil. 2009. Give Input a Chance. In Input Matters in SLA. Edited by Thorsten Piske and Martha Young-Scholten. Brisotl: Multilingual Matters, pp. 175–90. [Google Scholar]

- Frizelle, Pauline, Paul A. Thompson, David McDonald, and Dorothy V. M. Bishop. 2018. Growth in Syntactic Complexity between Four Years and Adulthood: Evidence from a Narrative Task. Journal of Child Language 45: 1174–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Götz, Sandra. 2013. Fluency in Native and Nonnative English Speech. Amsterdam: John Benjamins Publishing Company, vol. 53. [Google Scholar]

- Grömping, Ulrike. 2006. Relative Importance for Linear Regression in R: The Package Relaimpo. Journal of Statistical Software 17: 1–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grosjean, François. 1980. Spoken Word Recognition and the Gating Paradigm. Perception and Psychophysics 28: 299–310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Han, ZhaoHong. 2013. Forty Years Later: Updating the Fossilization Hypothesis. Language Teaching 46: 133–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hartshorne, Joshua K., Joshua B. Tenenbaum, and Steven Pinker. 2018. A Critical Period for Second Language Acquisition: Evidence from 2/3 Million English Speakers. Cognition 177: 263–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Havron, Naomi, Limor Raviv, and Inbal Arnon. 2018. Literate and Preliterate Children Show Different Learning Patterns in an Artificial Language Learning Task. Journal of Cultural Cognitive Science 2: 21–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holton, David, Peter Mackridge, and Irene Philippaki-Warburton. 2004. Greek: An Essential Grammar of the Modern Language. London: Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Huettig, Falk, Niharika Singh, and Ramesh Kumar Mishra. 2011. Language-Mediated Visual Orienting Behavior in Low and High Literates. Frontiers in Language Sciences 2: 285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hunt, Kellogg W. 1970. Syntactic Maturity in Schoolchildren and Adults. Monographs of the Society for Research in Child Development 35: 1–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johansson, Victoria. 2008. Lexical Diversity and Lexical Density in Speech and Writing: A Developmental Perspective. Working Papers. Lund, Sweden: Department of Linguistics and Phonetics, Lund University, vol. 53, pp. 61–79. [Google Scholar]

- Johnson, Jacqueline S., and Elissa L. Newport. 1989. Critical Period Effects in Second Language Learning: The Influence of Maturational State on the Acquisition of English as a Second Language. Cognitive Psychology 21: 60–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Julien, Manuela, Ineke Van de Craats, and Roeland Van Hout. 2013. There Is a Dummy ‘Is’ in Early First Language Acquisition. Dummy Auxiliaries in First and Second Language Acquisition. Berlin: De Gruyter Mouton, pp. 101–40. [Google Scholar]

- Karanth, Pratibha, Asha Kudva, and Aparna Vijayan. 1995. Literacy and Linguistic Awareness. In Speech and Reading. A Comparative Approach. Edited by Beatrice de Gelder and José Morais. Hove: Erlbaum (UK) Taylor & Francis, pp. 303–16. [Google Scholar]

- Kolinsky, Régine, Luz Cary, and Jose Morais. 1987. Awareness of Words as Phonological Entities: The Role of Literacy. Applied Psycholinguistics 8: 223–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Konta, Irene. 2012a. Gender Assignment and Gender Agreement in Child Greek L2. In Selected Papers of the 10th International Conference of Greek Linguistics. Edited by Zoe Gavriilidou, Angeliki Efthymiou, Evangelia Thomadaki and Penelope Kambakis-Vougiouklis. Komotini: Democritus University of Thrace, pp. 381–89. [Google Scholar]

- Konta, Irene. 2012b. I Apodosi Genous Stin Elliniki Os Defteri Glossa: Endiksis Apo Pedia Me Mitriki Glossa Tin Tourkiki (Gender Assigment in Greek as a Second Language: Evidence from L1 Turkish Children). Meletes Gia Tin Elliniki Glossa 32: 387–99. [Google Scholar]

- Konta, Irene. 2013a. I Simfonia Genous Stin Elliniki Os Defteri Glossa: Endiksis Apo Pedia Me Mitriki Glossa Tin Tourkiki (Gender Agreement in Greek as a Second Language: Evidence from L1 Turkish Children). Meletes Gia Tin Elliniki Glossa 33: 231–43. [Google Scholar]

- Konta, Irene. 2013b. Gender Assignment and Gender Agreement in Advanced Child L2 Greek: The Role of Input. In Advances in Language Acquisition. Edited by Stavroula Stavrakaki, Marina Lalioti and Polyxeni Konstantinopoulou. Newcastle: Cambridge Scholars Publishing, pp. 337–45. [Google Scholar]

- Konta, Irene. 2013c. The Acquisition of Modern Greek by L1 Turkish Children: Evidence from Nominal Agreement and Morphology. Ph.D. Dissertation, Aristotle University of Thessaloniki, Thessaloniki, Greece. [Google Scholar]

- Koromvokis, Patricia-Panagiota, and Ioannis Kalaitzidis. 2013. The Acquisition of Grammatical Gender in Greek. A Journal for Greek Letters 16–17: 307–23. [Google Scholar]

- Kurvers, Jeanne. 2002. Met Ongeletterde Ogen. Kennis van Taal En Schrift van Analfabeten. [With Nonliterate Eyes. Knowledge of Language and Writing of Non-Literates]. Ph.D. Thesis, Tilburg University, Tilburg, The Netherlands. [Google Scholar]

- Kurvers, Jeanne, Ton Vallen, and Roeland van Hout. 2006. Discovering Features of Language: Metalinguistic Awareness of Adult Illiterates. In Low-Educated Second Language and Literacy Acquisition: Proceedings of the Inaugural Symposium Tilburg 2005. Edited by Ineke van de Craats, Jeanne Kurvers and Martha Young-Scholten. Utrecht: LOT, pp. 69–88. [Google Scholar]

- Larson-Hall, Jenifer. 2010. A Guide to Doing Statistics in Second Language Research Using R. Available online: http://cw.routledge.com/textbooks/9780805861853/guide-to-R.asp (accessed on 31 May 2019).

- Mastropavlou, Maria, and Iianthi M. Tsimpli. 2011. The Role of Suffixes in Grammatical Gender Assignment in Modern Greek: A Psycholinguistic Study. Journal of Greek Linguistics 11: 27–55. [Google Scholar]

- Meisel, Jürgen M., Harald Clahsen, and Manfred Pienemann. 1981. On Determining Developmental Stages in Natural Second Language Acquisition. Studies in Second Language Acquisition 3: 109–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morais, José, Luz Cary, Jesus Alegria, and Paul Bertelson. 1979. Does Awareness of Speech as a Sequence of Phones Arise Spontaneously? Cognition 7: 415–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morais, José, Jesus Alegria, and Alain Content. 1986. Literacy Training and Speech Segmentation. Cognition 24: 45–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nippold, Marilyn A., Linda J. Hesketh, Jill K. Duthie, and Tracy C. Mansfield. 2005. Conversational v. Expository Discourse: A Study of Syntactic Development in Children, Adolescents and Adults. Journal of Speech, Language and Hearing Research 48: 1048–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nunes, Terezinha, P. Bryant, and Miriam Bindman. 2006. The Effects of Learning to Spell on Children’s Awareness of Morphology. Reading and Writing 19: 767–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perdue, Clive. 1993. Adult Language Acquisition: Volume 2, the Results: Cross-Linguistic Perspectives. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Pienemann, Manfr. 1980. The Second Language Acquisition of Immigrant Children. In Second Language Development: Trends and Issues. Edited by Sascha W. Felix. Tübingen: Narr-Verlag, pp. 41–56. [Google Scholar]

- Pienemann, Manfr. 2005. Cross-Linguistic Aspects of Processability Theory. Amsterdam: John Benjamins Publishing, vol. 30. [Google Scholar]

- Ravid, Dorit, and Liliana Tolchinsky. 2002. Developing Linguistic Literacy: A Comprehensive Model. Journal of Child Language 29: 417–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Read, Charles A., Yun-Fei Zhang, Hong-Yin Nie, and Bao-Qing Ding. 1986. The Ability to Manipulate Speech Sounds Depends on Knowing Alphabetic Writing. Cognition 24: 31–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reis, Alexandra, and Alexandre Castro-Caldas. 1997. Illiteracy: A Cause for Biased Cognitive Development. Journal of the International Neuropsychological Society 3: 444–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scott, Cheryl M. 1988. Spoken and Written Syntax. In Later Language Development. Ages 9 through 19. Edited by Marilyn A. Nippold. Boston: Little, Brown and Company, pp. 49–95. [Google Scholar]

- Speaking Proficiency English Assessment Kit (SPEAK). 1982. Educational Testing Service. New York: Princeton. [Google Scholar]

- Stavrakaki, Stavroula, and Harald Clahsen. 2009. The Perfective Past Tense in Greek Child Language. Journal of Child Language 36: 113–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tarone, Elaine, Martha Bigelow, and Kit Hansen. 2009. Literacy and Second Language Oracy-Oxford Applied Linguistics. Oxford: Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Van de Craats, Ineke, and Roeland Van Hout. 2010. Dummy Auxiliaries in the Second Language Acquisition of Moroccan Learners of Dutch: Form and Function. Second Language Research 26: 473–500. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van de Craats, Ineke, Jeanne Kurvers, and Martha Young-Sholten. 2006. Research on Low-Educated Second Language and Literacy Acquisition. In Low-Educated Second Language and Literacy Acquisition: Proceedings of the Inaugural Symposium Tilburg 2005. Edited by Ineke van der Craats, Jeanne Kurvers and Martha Young-Sholten. Utrecht: LOT, pp. 7–23. [Google Scholar]

- Varlokosta, Spyridoula. 2002. Functional Categories in Greek as a Second Language Evidence for the Full Transfer/Full Access Hypothesis. Glossologia 14: 59–82. [Google Scholar]

- Young-Scholten, Martha. 2013. Low-Educated Immigrants and the Social Relevance of Second Language Acquisition Research. Second Language Research 29: 441–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Young-Scholten, Martha, and Rola Naeb. 2010. Non-Literate L2 Adults’ Small Steps in Mastering the Constellation of Skills Required for Reading. In Low Educated Adult Second Language and Literacy. Banff Calgary: Bow Valley College, pp. 80–91. [Google Scholar]

- Young-Scholten, Martha, and Nancy Strom. 2006. First-Time L2 Readers: Is There a Critical Period? LOT Occasional Series 6: 45–68. [Google Scholar]

| Mean | Median | Range | IQR | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sg Det Agr | 91 | 100 | 66–100 | 78–100 |

| Sg Adj Agr | 87 | 100 | 60–100 | 71–100 |

| Pl Det Agr | 87 | 100 | 44–100 | 73–100 |

| Pl Adj Agr | 78 | 76 | 44–100 | 60–100 |

| Past Sigm | 55 | 60 | 10–90 | 40–80 |

| Past Nonsigm | 38 | 40 | 0–90 | 20–60 |

| Nonce Past | 23 | 20 | 0–60 | 0–50 |

| PausesToFluentSegments | 54 | 55 | 43–68 | 50–58 |

| SpeechRate | 56 | 56 | 33–67 | 52–60 |

| MLTU | 8.96 | 8.40 | 4.11–20.14 | 6.92–9.70 |

| ClausalDensity | 1.22 | 1.19 | 1.00–1.89 | 1.10–1.27 |

| TTR | 0.76 | 0.77 | 0.32–0.96 | 0.69–0.85 |

| LexicalDensity | 38.6 | 37.8 | 25.9–59.7 | 33.2–43.0 |

| Linguistic Measure | Education | LoR | Edu*LoR | Model R2 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sg Det Agr | -- | -- | -- | -- |

| Sg Adj Agr | -- | -- | -- | -- |

| Pl Det Agr | 0.024 | 0.001 | 0.094 | 0.120 |

| Pl Adj Agr | 0.150 | -- | -- | 0.150 |

| Past Sigm | 0.306 | -- | -- | 0.306 |

| Past Nonsigm | 0.383 | -- | -- | 0.383 |

| Past Nonce | 0.379 | -- | -- | 0.379 |

| Pauses To Fluent Segments | -- | 0.080 a | -- | 0.080 a |

| Speech Rate | -- | 0.184 | -- | 0.184 |

| MLTU | (0.078) | (0.069) | 0.77 | 0.223 |

| Clausal Density | -- | 0.140 | -- | 0.140 |

| TTR | 0.122 | 0.003 a | 0.071 a | 0.196 |

| Lexical Density | 0.194 | 0.066 | -- | 0.260 |

© 2019 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Janko, E.; Dąbrowska, E.; Street, J.A. Education and Input as Predictors of Second Language Attainment in Naturalistic Contexts. Languages 2019, 4, 70. https://doi.org/10.3390/languages4030070

Janko E, Dąbrowska E, Street JA. Education and Input as Predictors of Second Language Attainment in Naturalistic Contexts. Languages. 2019; 4(3):70. https://doi.org/10.3390/languages4030070

Chicago/Turabian StyleJanko, Eleni, Ewa Dąbrowska, and James A. Street. 2019. "Education and Input as Predictors of Second Language Attainment in Naturalistic Contexts" Languages 4, no. 3: 70. https://doi.org/10.3390/languages4030070

APA StyleJanko, E., Dąbrowska, E., & Street, J. A. (2019). Education and Input as Predictors of Second Language Attainment in Naturalistic Contexts. Languages, 4(3), 70. https://doi.org/10.3390/languages4030070