Abstract

The current study investigates whether there is variation among different types of control stimuli in code-switching (CS) research, how such stimuli can be used to accommodate heterogeneity, and how they can also be used as a baseline comparison of acceptability. A group of native Spanish–English bilinguals (n = 20) completed a written acceptability judgment task with a 7-point Likert scale. Five different types of control stimuli were included, with three types considered to be completely acceptable (complex-sentence switches, direct-object switches, and subject–predicate switches) and two types considered to be completely unacceptable (pronoun switches and present–perfect switches). Additionally, a set of present–progressive switches were included as a comparison, as their acceptability status is still actively debated. The participants as a whole exhibited the expected grammatical distinctions among the control stimuli, but with a high degree of individual variability. Pronoun switches and auxiliary verb switches were rated significantly lower than the complex-sentence switches, direct-object switches, and subject–predicate switches. These results show that control stimuli can also establish a baseline comparison of acceptability, and recommendations for inclusion in experimental CS research are provided.

1. Introduction

Research on the structural constraints of intra-sentential code-switching (CS), the simultaneous use of two languages within a sentence by bilingual speakers, has consistently revealed it to be a rule-governed phenomenon. Despite general findings in the literature, specific intuitions regarding CS can be quite heterogeneous among a group of bilinguals. It is not always clear to what extent this heterogeneity is an artifact of the methods employed, as there are methodological concerns specific to research on bilinguals (De Houwer 1998; Grosjean 1998; among others), as well as CS specifically (González-Vilbazo et al. 2013; Gullberg et al. 2009; MacSwan and McAlister 2010; among others). Further muddling the issue is the operationalization of acceptability, as it is not clear whether the heterogeneity encountered in such research could also be explained by refining the measurements and definitions of acceptability used in CS experiments.

In the spirit of Grosjean (1998), who suggests that “some of the difficulties encountered by [bilingual] researchers, and some of the conflicting results they have obtained, could perhaps have been lessened, if not avoided, had close attention been paid to methodological and conceptual issues” (p. 132), this study hopes to better inform the collection of experimental CS data by detailing the inclusion of control stimuli in an acceptability judgment task (AJT) targeting code-switched Spanish–English sentences. There are three different aspects analyzed. First, different types of control stimuli are compared to ascertain whether there is variation among them. The results show that participants treated all commonly attested acceptable switches—complex-sentence switches, subject–predicate-switches, and direct-object switches—equally, as they did generally unacceptable ones—pronoun switches and present–perfect switches. Next, I look at how control stimuli can be used effectively to better understand heterogeneity in bilingual CS intuitions. The results show that the participants are able to be divided into two broad groups: those who found the grammatical distinction between the control stimuli types and those who did not. Finally, this study looks at how control stimuli can be used as a baseline of acceptability. For this step, a comparison set of stimuli involving present–progressive switches are included. The results show that the control stimuli can indeed be used to understand how participants are quantifying their acceptability on the Likert scale. By directly comparing the present–progressive switches to the acceptable and unacceptable switches, three different participant groups were identified: those who accepted present–progressive switches, those who did not, and those whose ratings were somewhere in between. I conclude by recommending a procedure for inclusion of control stimuli in experimental CS research.

2. Background

2.1. Code-Switching as a Data Source and a Linguistic Tool

Refinement of the methods of experimental CS research is contingent upon why such research is worthy of pursuit in the first place. There are many reasons that the formal study of syntactic restrictions on CS merits continued investigation, two of which I highlight here. First, CS data in general can and should be considered relevant data to syntactic theory. Study of the grammatical aspects of CS first attempted formalization with Poplack’s (1980) Equivalence Constraint. Since that time, considerable work has been done, with many researchers agreeing that CS is simply another form of expression of a bilingual speaker’s I-language (Chomsky 1986). This notion is central to one of the prominent frameworks in the field, the Minimalist approach to CS, whether it be lexicalist in nature (MacSwan 1999, 2014) or an exoskeletal analysis (Grimstad et al. 2018). Arguing that there are no restrictions that are specific to CS (i.e., no third grammar), the adoption of a generativist framework entails various assumptions. One of the most central assumptions, as argued by González-Vilbazo et al. (2013), is that if one of the goals of linguistics is to model the human language faculty by formulating language models that can generate all (and only) grammatical sentences native to a language, then such models “should also account for, and draw from, CS data” (p. 120).

CS data is not only a relevant data source, but it can be a uniquely useful one. Because CS data is an expression of I-language just like monolingual data, it can and should also be used to inform syntactic theory. What is intriguing about CS is that this source of linguistic data can include combinations of linguistic features that either do not exist or are obscured in monolingual data. Taking advantage of this distinctive quality, syntactic research using CS data has been used to advance our understanding of all sorts of linguistic phenomena: adjective placement (Cantone and MacSwan 2009; de Nicolás and Robledo 2018), classifiers (Bartlett and González-Vilbazo 2010), gender assignment (Badiola and Sande 2018; Delgado 2018; Liceras et al. 2008), that-trace effects (Ebert and Hoot 2018), wh-movement (Ebert 2014), and word order (Finer 2014; González-Vilbazo and López 2011, 2012; Jansen et al. 2012), to name a few. The data used in such research has complemented the monolingual data related to the phenomena in question, resulting in a more robust dataset, which in turn has been able to support or negate various claims, or in some cases even develop new ones. For example, the pronoun typology proposed by Cardinaletti and Starke (1999) is supported by the Spanish–English code-switched pronouns discussed by Koronkiewicz (2014) and González-Vilbazo and Koronkiewicz (2016), non-structural (i.e., semantics-based) proposals of sluicing are put into question by the Spanish–German CS data of González-Vilbazo and Ramos (2018), and the C and T Hypothesis was developed using the Spanish–English and Spanish–German pro-drop CS data in Sande (2018).

2.2. Methods in Code-Switching Research

Experimental research regarding CS data overlaps with monolingual data collection when it comes to many methodological concerns. The same way researchers targeting an individual language may need to decide how to best operationalize acceptability or weigh the merits of lab-based or introspective/consultant data, CS researchers often face the same debates and can rely on the broader research to inform their decisions. The work of Jon Sprouse and colleagues in particular has illuminated much in this regard (Sprouse 2007, 2008; Sprouse and Almeida 2012; Sprouse et al. 2013; among others). This study, however, sets such topics aside, instead focusing attention toward aspects of syntactic research that are particularly problematic when looking at language mixing.

As participants, bilinguals bring with them all sorts of variables that are non-existent in monolingual populations. Grosjean (1998) provides a seminal overview on such issues as they apply to bilingual research in general, as does De Houwer (1998) with regard specifically to Bilingual First Language Acquisition. At the broadest level, such factors include how researchers define the concept of bilingual and how to group different types of individuals within those definitions. But that is just the tip of the iceberg, as researchers must also address the bilingual language mode, the sociolinguistic context of the two languages in question, multi-lingual stimuli/task design, and so on.

Within the study of bilingualism, there are also methodological concerns that pertain specifically to CS. In addition to merely defining the phenomenon, there are a plethora of other issues, including the merits of naturalistic and elicited CS data (MacSwan and McAlister 2010), attitudes toward CS (Badiola et al. 2018), CS grammaticality judgment task design (Stadthagen-González et al. 2018), and experimental-behavioral techniques regarding CS comprehension and production (van Hell et al. 2018), to name a few. Researchers such as Gullberg et al. (2009) and González-Vilbazo et al. (2013) also provide broader overviews, with the latter highlighting three prominent categories when it comes to methodological issues in CS research: project design, experimental procedure, and participant selection.

The current study is a continuation of González-Vilbazo et al.’s (2013) first category, project design, as it centers on the specific needs of code-switched stimuli in experimental research. In their discussion, González-Vilbazo et al. tackle two specific components of stimuli design, lexical item selection and modality of presentation of stimuli, as they wish to “mitigate two potential confounds” (pp. 123–24). In essence, their intention is to design stimuli that will produce ratings in an AJT that are most representative of the participants’ linguistic competence. For example, they state that there is a possibility of a bias against written stimuli due to CS being primarily a spoken phenomenon. Ratings produced by a written AJT may not be an accurate reflection of the grammaticality of such structures.1 González-Vilbazo et al.’s discussion of stimuli design is limited to how the target stimuli can be manipulated to improve the reliability of the results. Unfortunately, their advice does not provide any aid with regard to heterogeneity among the participant results and/or how to operationalize (un)acceptability. By expanding the discussion of stimuli design to look not only at the target stimuli but also control stimuli, both those issues can be better addressed.

2.3. Defining (Un)grammatical Code-Switches

Defining grammaticality in experimental research is no easy task, as researchers must rely on indirect methods to tap into the linguistic competence of individuals. Following Sprouse’s (2007) argument, I assume that grammaticality is a categorical distinction even though research in experimental syntax often results in a spectrum of continuous acceptability. As he states:

In other words, although the results of an AJT may produce different ratings for any number of various types of sentences, as far as syntactic theory is concerned sentences are either well-formed or not. The variation within the results can be derived from any number of extra-grammatical factors, such as plausibility, working memory limitations, etc. It is within the analysis of experimental syntax research that one must use interpretation to determine what such gradated results mean. Nonetheless, the methods employed in such research should aim to help reduce the amount of interpretation needed. Furthermore, within a generativist approach to CS (Grimstad et al. 2018; MacSwan 1999, 2014), if categorical grammaticality applies to monolingual utterances, then it must also do so for mixed utterances. Although experimental CS research may produce a spectrum of acceptability, we should follow the same argument that Sprouse (2007) makes for syntactic research in general.While many sentences are either clearly acceptable or clearly unacceptable, a significant number of sentences fall somewhere in between in a gray area of partial acceptability. This fact has been explicitly admitted by linguists since at least Chomsky 1965. The working assumption adopted by most linguists over the past 40 years has been that these intermediate levels of acceptability are caused by properties other than grammatical knowledge.(Sprouse 2007, p. 123)

If acceptability is continuous as mentioned, then defining a code-switched sentence as (un)acceptable using a specific point on the scale is not possible. A more effective way to operationalize (un)acceptability is to rely on relative acceptability. For example, were one to test two related but distinct structures, if the statistical analysis revealed that the two were different, it would suggest that one is considered more acceptable than the other. To illustrate this point, we can outline one strategy that is already often employed in experimental CS research. Many studies include a strategic design of stimuli so as to position two related sentences as comparable. For example, let’s imagine we want to test whether it is grammatical to switch after the auxiliary verb have/haber in Spanish–English CS. We could develop the following stimuli to be tested, as shown in (1).

The sentence in (1a) has the switch occur between the English auxiliary verb have and its complement, the Spanish past participle estudiado ‘studied’. This sentence is the target stimulus as it contains the principle switch under investigation. By including either the sentence(s) in (1b) and/or (1c), we can make a direct comparison. In both comparison sentences, the lexical material is almost identical. What is distinct is where the switch takes place. In (1b), the auxiliary verb is modified from English to Spanish (i.e., han ‘have’), which in turns moves the switch to between the subject and the finite verb. This is a logical comparison sentence to create, as such subject–predicate switches are commonly attested in the literature. In (1c), the past participle is changed from Spanish to English (i.e., studied), moving the switch in the opposite direction so that it is now between the finite verb and its complement, the direct object. Such direct-object switches are also commonly attested. In an AJT, if the ratings produced for (1a) are comparable to those produced for (1b) and/or (1c), we could argue that switching after the auxiliary verb have in Spanish–English CS is acceptable. However, were the ratings for (1a) to be significantly lower than those for (1b) and/or (1c), we can argue that such a switch is unacceptable. Importantly, these distinctions could be made regardless of the exact scale employed in the AJT, and regardless of where the ratings fell on that scale, as the comparison is always relative to the other sentence.

| 1. | a. | * | His friends have | estudiado | español. |

| studied | Spanish | ||||

| ‘His friends have studied Spanish.’ | |||||

| b. | His friends | han | estudiado | español. | |

| have | studied | Spanish | |||

| ‘His friends have studied Spanish.’ | |||||

| c. | His friends have studied | español. | |

| Spanish | |||

| ‘His friends have studied Spanish.’ | |||

A few different issues may arise, however. First, it is possible that the target structure under investigation may not have an obvious comparison sentence that can be easily constructed by moving the switch point. Syntactic phenomena such as wh-movement and preposition stranding come to mind, where word order and other factors would make stimuli construction more complex. In such cases, with no direct comparison available, it would be helpful to have some other sentence type(s) completely removed from the phenomenon under analysis to use as a benchmark of (un)acceptability.

Another possible issue is that of heterogeneity both within and across participants. There is no question that the linguistic competence of a group of bilinguals is not a monolith. As with any group of speakers, individual differences can have an impact on all sorts of factors related to one’s I-language and as a consequence the linguistic intuitions that are derived from that I-language. When it comes to bilinguals in particular, there are countless additional factors at play that discourage homogeneity, including language proficiency, language dominance, manner/age of acquisition for each language, among many others.2

Heterogeneous results, however, cannot automatically be assumed to be reflective of heterogeneity of linguistic competence among a group of speakers. If speakers are found to differ in their performance on an AJT, it is possible that this is a result of divergent linguistic competences. But it also possible that one or more individuals did not complete the task appropriately so as to accurately tap into their intuitions. This is of particular importance to experimental CS research because of how distinct the sentences under analysis are. For whatever reason, bilingual participants are often less sure/consistent when rating code-switched sentences when compared to their monolingual equivalents. Take for example Ebert and Koronkiewicz’s (2018) work on the inclusion of monolingual comparison stimuli in experimental CS research, where it is argued that acceptability can be directly tied to switch point by having participants rate the same sentences in both mixed and non-mixed versions. When looking at pronouns, the standard deviations for the mean ratings range from 1.81 to 4.35 (out of 7) for Spanish–English CS stimuli, but only 0.57 to 2.76 for the monolingual comparison stimuli (Ebert and Koronkiewicz 2018, p. 37). Because of this greater variability, CS researchers must take extra care in interpreting such data. For example, if a participant rated all sentences sporadically with no discernable pattern by type, how can we know for certain that the seemingly random ratings are not arbitrary, but rather in line with their I-language? Or, imagine if a participant rated all sentences equally; how can we know for sure that within their I-language all those sentences are indeed equally (un)grammatical? Going back to our example in (1), assume two participants showed no significant difference between the sentences in (1a) and (1b). As mentioned, this should lead us to assume that these individuals find present–perfect switches completely acceptable. However, what if one of those participants rated both sentences at the extreme top of the scale and the other rated both at the bottom? Should we be treating those results as equal? And how confident can we be that in both cases we are indeed tapping into the linguistic competence of each bilingual? By clearly defining separate control stimuli, we can better understand how effective the methods are at revealing patterns of (un)acceptability in CS.

2.4. Research Questions and Hypotheses

The following research questions are proposed in order to better understand the role control stimuli can play in experimental CS research:

- Is there variation between different types of CS control stimuli?

- How can control stimuli be used to account for CS heterogeneity?

- How can control stimuli be used as a baseline comparison of CS (un)acceptability?

3. Materials and Methods

3.1. Participants

A total of 20 US Spanish–English bilinguals participated in the current study, with ages ranging from 19 to 55 years old (M = 23.5). All subjects gave their informed consent for inclusion before they participated in the study. The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki, and the protocol was approved by the University of Alabama’s Institutional Review Board (Protocol Number 8825). In exchange for participating, most were awarded extra credit in their respective advanced undergraduate Spanish courses; the remainder (n = 3) were financially compensated for their time. All individuals were either born in the US or moved there at a young age (M = 2.7 years old). As 2L1 bilinguals, the participants reported having acquired both Spanish and English as a child, listing either Spanish or both Spanish and English as the home language(s) while growing up. See Table 1 for a quantitative summary of the participants’ language profile. Although an explicit measure of dominance was not administered, given the reported proficiency and exposure, it can be understood that the group is English dominant while still maintaining an intermediate-to-advanced level of Spanish. The most common heritage was Mexican descent, although this was not entirely homogenous among the group. One participant each identified one or both of their parents/caregivers as Argentine, Colombian, Cuban, Dominican, Guatemalan, Peruvian, or Spanish. Importantly, all participants indicated in the background questionnaire that they can and do use both Spanish and English in the same sentence to some degree (i.e., they are code-switchers).

Table 1.

Overview of participants’ language profile.

3.2. Task

The experimental procedure consisted of a written AJT3 with a 7-point Likert scale (1 = completely unacceptable/completamente inaceptable, 2 = mostly unacceptable/mayormente inaceptable, 3 = somewhat unacceptable/un poco inaceptable, 4 = unsure/no sé, 5 = somewhat acceptable/un poco aceptable, 6 = mostly acceptable/mayormente aceptable, 7 = completely acceptable/completamente aceptable). The task was presented as an online survey via Qualtrics. Before completing the AJT, participants filled out a background questionnaire regarding their language history and profile, and they went through task training and practice. The training addressed the basics of how to complete an AJT, introducing the rating scale and asking participants to decide if a sentence “sound[ed] strange” or not. The instructions, with the help of a series of sample sentences, told participants that the task is to determine “whether the sentence is possible in English, Spanish or code-switching.” Following González-Vilbazo et al. (2013), the training also served to prime participants into bilingual mode, as the instructions used Spanish–English CS throughout (typically at the sentence or clause level, except for the occasional switched prepositional phrase). See Appendix A for the complete task training text. After the training session, participants had a practice block of a dozen sentences.

Following the training and practice session, the experimental portion of the AJT was divided into three distinct blocks based on language(s). Participants first completed a block that included code-switched Spanish–English sentences (n = 54), followed by a block entirely in Spanish (n = 27) and then another in English (n = 27). For the current investigation, only the data from the first block is included in the dataset, as the monolingual judgments are not relevant to the research questions. Following Ebert and Koronkiewicz (2018), such sentences were included as a comparison to better ensure that any unacceptability found in the mixed sentences was specific to the switch point and not a judgment based on some different linguistic phenomenon. Participants rated the monolingual versions of the sentences under analysis here as completely acceptable, thus confirming that the task did indeed target the (un)acceptability of switching. Immediately prior to the second and third block, participants completed the Spanish proficiency measure (Montrul and Slabakova 2003) and English proficiency measure (O’Neill et al. 1981), respectively. Overall, the entire process took participants about an hour to complete.

3.3. Stimuli

The target stimuli for the current study are those that would be considered effective control stimuli for experimental CS research. Establishing a baseline of (un)acceptability requires code-switched sentences that demarcate both ends of the scale. Ideal acceptable control stimuli would include switches considered completely acceptable by most (if not all) bilingual speakers of a given language pair. Therefore, the acceptable control stimuli were one of three commonly attested (i.e., grammatical) switch types: complex-sentence switches (n = 6), subject–predicate switches (n = 6), and direct-object switches (n = 6). As for the specific lexical content, the acceptable control stimuli included in the AJT were taken or modified from code-switched Spanish–English sentences found in the Bangor Miami corpus (http://www.bangortalk.org.uk). That is to say, these stimuli are examples of code-switched sentences actually produced by Spanish–English bilinguals in the US. Examples of each acceptable control stimulus type are presented in (2):

In (2a), the language changes from English to Spanish at the complementizer si ‘if’, exemplifying a complex-sentence switch. Since the language mixing occurs at (not within) the clausal boundary, such a switch can be considered syntactically equivalent to inter-sentential CS, a commonly reported acceptable switch in the literature. In (2b) and (2c), both sentences include intra-sentential switches occurring immediately before or after the finite verb. The former follows the lexical subject and the latter precedes the direct object, another two commonly reported switches.

| 2. | a. | We’ll hear a sound | si | alguien | toca | el | timbre. |

| if | someone | rings | the | doorbell | |||

| ‘We’ll hear a sound if someone rings the doorbell.’ | |||||||

| b. | My brother | está | pescando. | |

| is | fishing | |||

| ‘My brother is fishing.’ | ||||

| c. | He has | una | mala | reputación. | |

| a | bad | reputation | |||

| ‘He has a bad reputation.’ | |||||

In addition to the acceptable control stimuli, unacceptable control stimuli were included in the AJT as well. It is important to target both ends of (un)acceptability as it ensures that participants are not indiscriminately accepting all sentences, regardless of type. In other words, unacceptable control stimuli should be included to ensure participants are completing the task. Given that such a switch would by definition need to be ungrammatical, such sentences could not be pulled from corpus data4; therefore, the unacceptable control stimuli were created specifically for this study. These stimuli were designed using two commonly reported restrictions (i.e., ungrammatical) in Spanish–English CS, both of which are in line with a generativist approach to CS (Grimstad et al. 2018; MacSwan 1999, 2014): pronoun switches (n = 6) and present–perfect switches (n = 6). An example of each is provided in (3):

The unacceptable control stimulus in (3a) is similar to the acceptable control stimulus in (2b), as both cases involve a switch between the subject and the finite verb. The crucial difference is that although a lexical subject is considered a grammatical switch, it is not when a weak pronoun is in subject position. Although, a strong pronoun can be switched in such a context (González-Vilbazo and Koronkiewicz 2016; Koronkiewicz 2014), all pronoun stimuli created for this study include only weak pronouns, as they lack any of the defining characteristics of strong pronouns (Cardinaletti and Starke 1999), such as prosodic stress, modification, coordination, and so on. In (3b), the switch occurs within the verb phrase, where the auxiliary verb have is in English and its complement, the past participle, is in Spanish. Although there is debate surrounding the availability of auxiliary verb switches more generally as some have argued that they are all restricted (Belazi et al. 1994; Timm 1975), whereas others suggest that progressive-tense switches can and do occur at the auxiliary–participle boundary (Bentahila and Davies 1983; Giancaspro 2015; Guzzardo Tamargo and Dussias 2013; Woolford 1983). Importantly these authors do not disagree when it comes to evidence against switching have/haber in Spanish–English mixed present–perfect sentences.5

| 3. | a. | * | They | compraron | unas | manzanas. |

| bought | some | apples | ||||

| ‘They bought some apples.’ | ||||||

| b. | * | The students have | prestado | atención | a | la | profesora | hoy. | |

| paid | attention | to | the | professor | today | ||||

| ‘The students have paid attention to the professor today.’ | |||||||||

The final set of stimuli included were a set of comparison stimuli of a structure whose grammaticality in Spanish–English CS does not have an officially accepted status in the field (Belazi et al. 1994; Bentahila and Davies 1983; Giancaspro 2015; Guzzardo Tamargo and Dussias 2013; Timm 1975; Woolford 1983), present–progressive switches. The ratings from these stimuli can be used to exemplify the usefulness of established control stimuli. An example is provided in (4):

Although a switch between the auxiliary verb have/haber (3b) has consistently been considered unacceptable, there is evidence that Spanish–English bilinguals are more accepting of a switch that occurs between the auxiliary verb be/estar and its complement, the present participle (4). However, it is not considered unquestionably acceptable, as various researchers categorize it as ungrammatical. As such, present–progressive switches can serve as a worthy set of comparison stimuli to the control stimuli included in this study.

| 4. | Her colleagues are | viendo | muchas | películas | este | mes. | |

| seeing | many | movies | this | month | |||

| ‘Her colleagues are seeing many movies this month.’ | |||||||

All sentences included in the study were balanced for various factors. Half of the sentences were switched from English-to-Spanish, and the other half from Spanish-to-English. The pronoun switches, present–perfect switches, and present–progressive switches included all third person subjects, with half plural and half singular. (The acceptable control stimuli varied more in person and number due to being pulled from corpus data.) In addition to the target stimuli, various filler stimuli were included (n = 18)6. See Appendix B for the complete list of code-switched stimuli used in the study.

4. Results

4.1. General Results

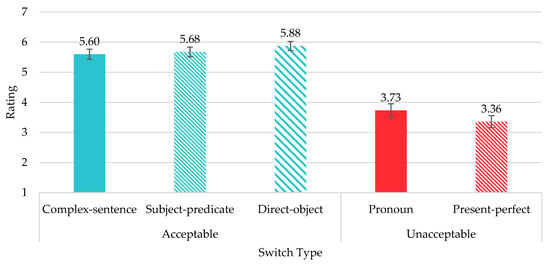

In order to answer the first research question, the comparison present–progressive stimuli are set aside, and the analysis focuses exclusively on the control stimuli. The control stimulus ratings provided during the AJT were averaged across all participants. The results show that the group as a whole exhibited the expected grammatical distinctions based on switch type. The acceptable control stimuli were rated nearer the acceptable end of the scale (M = 5.72, SD = 1.76), whereas the unacceptable control stimuli were rated in the bottom half of the acceptability scale (M = 3.55, SD = 2.30), as shown in Figure 1.7 Interestingly, not only did participants differentiate between the acceptable and unacceptable control stimuli, but there was also uniformity within the two broad groups of control stimuli. The three types of acceptable control stimuli patterned almost identically to each other, within about a quarter of a point; as did both types of unacceptable control stimuli, within about a third of a point.

Figure 1.

Mean rating of control stimuli by switch type.

A one-way ANOVA revealed there was a significant difference based on switch type (F(4,595) = 43.622, p < 0.001), confirming that the acceptable control stimuli were rated higher than the unacceptable control stimuli. Importantly, the Tukey post hoc test revealed no significant difference among the acceptable switch types (p > 0.05) nor between the unacceptable switch types (p = 0.590). Furthermore, an item analysis revealed no significant differences among the lexicalizations within each specific switch type (p > 0.05).

Returning to the first research question, these results show that there does not seem to be any variation between the different types of control stimuli included in this particular CS study. Participants consistently rated complex-sentence, subject–predicate, and direct-object switches as acceptable, while pronoun and present–perfect switches received unacceptable ratings that were parallel to each other. In the subsequent analyses, the switch types will be collapsed into their two broader categories of acceptable and unacceptable switches.

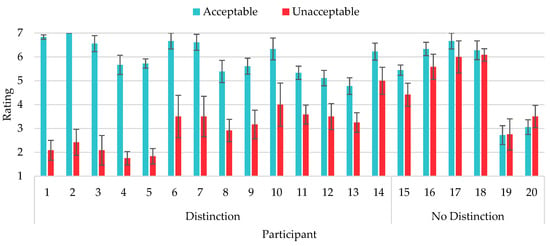

4.2. Heterogeneity Results

To answer the second research question, mean ratings for the control stimuli were calculated for each individual participant. There was a high degree of variability among the participants, as shown in Figure 2. Descriptively, though, almost everyone (Participants 1 through 18) was united in rating the acceptable control stimuli higher than the unacceptable control stimuli. However, within this group, there were those who differentiated the two at the extreme ends of the scale, as well as others who exhibited mean ratings with only a marginal distinction. The difference in mean ratings for these individuals ranges from almost 5 points (i.e., 79.2% of the scale) to less than a quarter of a point (i.e., 3.2% of the scale). Finally, there were two individuals (Participants 19 and 20) who rated the unacceptable control stimuli higher than the acceptable control stimuli, but they did so minimally, within half a point (i.e., 7.4% of the scale).

Figure 2.

Mean rating of control stimuli by participant and stimulus type.

A two-way ANOVA revealed that there was a statistically significant interaction between participant and stimulus type, F (19,560) = 6.781, p < 0.001. Simple main effects analysis showed that Participants 1 through 14 rated the acceptable control stimuli significantly higher than the unacceptable control stimuli (p < 0.05), whereas Participants 15 through 20 rated them equally (p > 0.05). In the subsequent analyses, these groups will be referred to as the Distinction Group and the No Distinction Group, respectively.

Returning to the second research question, these results show that control stimuli can be used to help sort out heterogeneity among CS intuitions. The findings were able to identify participants who did not rate the switch types according to their expected acceptability. Using the control stimuli, participants were able to be grouped based on whether or not they found a categorical distinction.

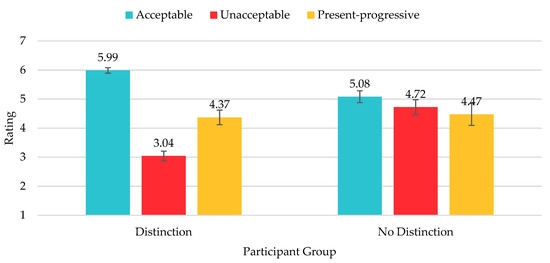

4.3. Comparison Results

To answer the final research question, the comparison present–progressive stimuli were included in the analysis. First, we can again look at the mean ratings for the participants as a whole. Across the board, the participants rated the present–progressive switches in between the two control stimuli types (M = 4.40, SD = 2.30). When these results are separated out into the Distinction Group and the No Distinction Group, the mean average for the present–progressive switches does not change much, but the relative acceptability to the control stimuli does, as shown in Figure 3. Across the board, the No Distinction Group seems to be rating all three stimulus types equally (M = 4.86, SD = 2.16), whereas with the Distinction Group there seems to be a clear hierarchy, with the acceptable switches at the top (M = 5.99, SD = 1.52), unacceptable switches at the bottom (M = 3.04, SD = 2.16), and the present–progressive switches occupying a middle tier (M = 4.37, SD = 2.32).

Figure 3.

Mean rating of all stimuli by participant group and stimulus type.

A two-way ANOVA revealed that there was a statistically significant interaction between participant group and stimulus type, F (2,714) = 25.819, p < 0.001. Simple main effects analysis showed that the Distinction Group rated each stimulus type differently, with the acceptable stimuli significantly higher than both other types (p < 0.001) and the present–progressive stimuli significantly higher than the unacceptable stimuli (p < 0.001). The No Distinction Group, on the other hand, showed no significant differences of any kind, rating all three stimulus types equally (p > 0.05). In other words, the Distinction Group exhibited the expected pattern, with the comparison structure falling in the middle the continuous acceptability spectrum, whereas the No Distinction Group showed no such pattern. Finally, an item analysis revealed a significant difference within the lexicalizations for the present–progressive switch type. Specifically, one item in particular received lower scores (M = 2.75, SD = 1.97) than half of the lexicalizations of that type (p < 0.05): Sus amigas están going shopping with their mothers this weekend ‘His/her/their friends are going shopping with their mothers this weekend’. This reduction is likely an artifact of having the switch occur with the English phrasal verb go shopping, whereas the remaining lexicalizations include non-phrasal verbs. Interestingly, with that item removed, the mean average for the present–progressive switches for the Distinction Group would increase slightly (M = 4.50, SD = 2.32), whereas for the No Distinction Group it would decrease (M = 4.37, SD = 2.32). Given this item was not a clear outlier in that it did not perform significantly different than two of the other items, it was not removed from the dataset.

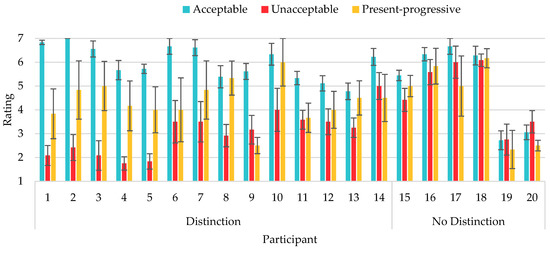

As done previously with the control stimuli, we can also look at the comparison results by individual participant. Again, there seems to be quite a bit of variation, as seen in Figure 4. One trend that carries over from looking at the results by participant group is that the ratings in the No Distinction Group are almost all identical regardless of the specific stimulus type. Although some individuals in this group rated the stimuli nearer the top of the scale (Participants 15 through 18), and others nearer the bottom (Participants 19 and 20), no participant in the No Distinction Group exhibits any clear difference regarding the mean ratings for the acceptable, unacceptable, and present–progressive switches. Within the Distinction Group, however, there is more variety. One commonality is that all but two of the participants (Participants 9 and 14) in this group rated the present–progressive switches in between the acceptable and unacceptable switches. For these participants, though, the difference in mean ratings for the present–progressive switches and the control switches ranges from 3 points (i.e., 50.0% of the scale) to 0.6 of a point (i.e., 0.01% of the scale) in either direction (compared to the acceptable or unacceptable switches). In other words, the proximity of the present–progressive switches’ mean rating to that of either control stimulus type varies substantially from individual to individual. For Participants 9 and 14, although the present–progressive ratings were rated lower than the unacceptable switches, they were within about half a point (i.e., 11.2% of the scale).

Figure 4.

Mean rating of all stimuli by participant group and switch type.

Isolating just the Distinction Group, a two-way ANOVA revealed that there was a statistically significant interaction between participant and stimulus type, F (26,462) = 2.200, p = 0.001. Simple main effects analysis showed that the participants can be divided into four different groups. First, Participants 1, 6 and 9 were the three individuals who rated the present–progressive switches significantly lower than the acceptable switches (p < 0.05) and equivalent to the unacceptable switches (p > 0.05). This group will be referred to henceforth as the No-Switch PrsProg Group, as their ratings of the present–progressive switch can be considered as unacceptable. The opposite is true for Participants 3 through 5 and Participant 8, who rated the present–progressive switches significantly higher than the unacceptable switches (p < 0.05) and equivalent to the acceptable switches (p > 0.05). This group will be referred to as the Switch PrsProg Group, as they considered the present–progressive switch acceptable. The other half of the participants’ mean ratings for the comparison stimuli are less clearly defined in terms of (un)acceptability. Participant 2 was the one individual whose mean ratings for the present–progressive switches occupied a true middle tier, as the ratings were both significantly higher than the unacceptable switches (p < 0.05) and significantly lower than the acceptable switches (p < 0.05). Participant 7 and Participants 10 through 14 also had mean ratings for the present–progressive switches in a middle spot, but in the sense that they were not significantly different than either of the control stimulus types (p > 0.05). These individuals will collectively be referred to as the Questionable PrsProg Group, as in both cases it is unclear if they considered the present–progressive switch truly acceptable or not.

These results show that the heterogeneity of the participant responses regarding present–progressive switches can be accounted for using the control stimuli as a comparison. Specifically, we can say that half of the participants exhibited a clearly defined (un)acceptability regarding present–progressive switches, with about half of that group considering them either acceptable or unacceptable. The remaining half of participants showed present–progressive switches as neither completely acceptable nor unacceptable.

5. Discussion

The first crucial finding of this study is that the specific stimulus types for the acceptable control stimuli were consistently rated, as were the unacceptable control stimuli. The specific type of switch involved was not relevant, as participants found the commonly cited acceptable switches (complex-sentence switches, subject–predicate switches, and direct-object switches) as equal, and they did so as well with the commonly cited unacceptable switches (pronoun switches and present–perfect switches). This finding should not be taken for granted within experimental CS research. First, it confirms previous literature that has stated that such switches are (un)grammatical for bilingual speakers. More importantly, though, as mentioned before bilinguals are often uncertain and/or inconsistent when rating code-switched sentences. However, the fact that participants were able to use the acceptability scale in a consistent manner for these switch types helps validate that reliable results can be gained from an AJT. Moreover, these results show that the particular type of canonical grammatical or ungrammatical switch does not have an effect; participants considered them as two broad types, following the categorical nature of grammaticality proposed by syntactic theory. Of course, the current study is limited in that it only included five types of control stimuli. It remains to be seen whether other types of commonly cited switches or switch restrictions would pattern identically. Future research could include more varied grammatical switches, such as adjuncts like adverbial phrases or prepositional phrases, or ungrammatical switches, such as clitics and negation.

Another important outcome of this study is that it presented a systematic way of isolating heterogeneity among the participants. Recall that a subsection of the participations, the No Distinction Group, rated all of the control stimuli as equal. This result could mean one of two things. The first option is that the I-languages of these individuals in fact includes no grammatical distinction between such switches. It is possible that, for example, these bilingual speakers find a switch at the clausal boundary of a complex-sentence just as acceptable as a switch at the point between the verb have/haber and its past participle. Analyses were conducted regarding the language profiles of the participants in order to determine whether there is something about the linguistic backgrounds of the No Distinction Group that would result in such a difference in I-languages. No significant differences were found between the two participant groups with regard to language exposure, self-rated proficiency, age of acquisition of Spanish, or score on the English proficiency measure. However, the No Distinction Group did score significantly lower on the proficiency measure in Spanish, t(18) = 3.423, p = 0.003, with these participants all being in the intermediate range, compared to the Distinction Group being a mixture of intermediate and advanced. Also, the No Distinction Group started acquiring English significantly earlier, t(18) = 2.658, p = 0.016, as they all did so at birth, whereas the Distinction Group was once again more mixed in this regard. These results underscore the potential impact of proficiency and age of acquisition with regard to CS behavior, and it is possible that these factors are having an impact on the results. Future research could aim to better control for these two specific variables.

A second option, though, is that the participants in the No Distinction Group (or perhaps a subset of them) did not appropriately complete the task. It is impossible to speculate how or why the AJT might have failed to tap into their linguistic competences. However, as an illustrative example, it is not unreasonable to consider Participant 19 and 20′s low rating of complex-sentence switches (M = 2.50, SD = 1.45) as emblematic of some extra-grammatical influence. Recall that such switches are equivalent to inter-sentential CS (i.e., switching at the sentence boundary), so the fact that these two participants did not rate even these switches closer to the acceptable end of the scale could be the result a general depression of ratings across the board. This reduction could be due to a stigmatized bias against CS; however, it is at this point pure conjecture, as no related data was collected from participants to say for sure.8 Importantly, through the use of the control stimuli, these individuals can be justifiably removed or isolated from the rest of the dataset. Moreover, such a decision can be made completely independently of the target stimuli/phenomena under analysis.

The identification of heterogeneity also played a key role when using control stimuli to establish a baseline comparison of (un)acceptability. Had the experiment been designed using comparison stimuli that directly modeled the target present–progressive stimuli, they could have looked like the sentence in (5):

The sentence in five is comparable in that it uses almost the exact same lexical material but changes the auxiliary verb from English to Spanish (i.e., están ‘are’), which creates an acceptable subject–predicate switch. However, recall that the No Distinction Group rated all stimulus types the same, including other (non-lexically equivalent) subject–predicate switches. Without the acceptable and unacceptable control stimuli, the findings for these participants would have suggested that they consider present–progressive switches as acceptable as subject–predicate switches, which as discussed above, is the less likely option compared to assuming such individuals did not accurately complete the task. Regardless of which of the two options is true, though, it is with the help of the unrelated control stimuli that such individuals are able to be isolated from the rest of the data set, which would be a necessary action for either scenario.

| 5. | Her colleagues | están | viendo | muchas | películas | este | mes. |

| are | seeing | many | movies | this | month | ||

| ‘Her colleagues are seeing many movies this month.’ | |||||||

As for the Distinction Group, the control stimuli were also effective at establishing a baseline comparison on (un)acceptability for the present–progressive switches. Again, if we were only to include the comparison sentence in (5), interpretation of the data would be quite different. If that were the case, the comparison being made would be solely between the present–progressive switches and the acceptable switches (as there would be no unacceptable switch comparison). The previously identified members of the No-Switch PrsProg Group would not change, having rated the present–progressive switches significantly lower than the acceptable switches. Nor would the members of the the Switch PrsProg Group change, for the opposite reason. However, the Questionable PrsProg Group would no longer exist. Participant 2 would be lumped in with the No-Switch PrsProg Group, as their unacceptable ratings would not be able to define a middle tier for the acceptability of present–progressive switches. The remaining participants would join the Switch PrsProg Group, as their unacceptable ratings would no longer be indistinguishable from their present–progressive switches. This shifting of groups results in literally half of the participants in the Distinction Group changing affiliation. Although the exact status for why these participants exhibited such variability with the present–progressive switches is beyond the scope of this particular study, it is undoubtable that the interpretation of the results and the subsequent analyses that would be derived from the data in each scenario would likely drastically differ. For example, at least at the broadest level, by including the acceptable and unacceptable control stimuli, the results suggest that for many of these bilinguals, the grammaticality/acceptability of present–progressive switches seems nebulous and worthy of more fine-tuned investigation. With just the direct comparison stimuli (of just subject–predicate switches), a researcher could plausibly interpret that there are merely two groups of individuals, those who accept present–progressive switches and those who do not.

Playing devil’s advocate, the inclusion of the acceptable and unacceptable control stimuli does create more complication than using just a direct comparison. In this case, it created a middle tier of individuals whose acceptability of present–progressive switches is hazy. One could argue that this outcome is not ideal, as it becomes unclear how to provide an analysis if we indeed assume acceptability is categorical. How should one proceed in such instances? First, such a middle tier of acceptability does not constitute evidence against its categorical nature. I would argue that such a result merely highlights the need for more fine-tuned examination of the structure in question. Here we only investigated a small sample of switching a present–progressive construction between Spanish and English. It is likely that with a broader set of stimuli that include more variables (e.g., controlling for the potential issue with phrasal verbs), a follow-up study could provide more clearly delineated bilateral results.

It is crucial to point out that, although this paper aims to accommodate heterogeneity, the mixture of participants included can still be considered a limitation. Although various factors were controlled for, including age of acquisition and proficiency, the bilinguals included here come from different linguistic backgrounds and distinct speech communities, which may be having an effect on the results. Future research could repeat this study in a more homogenous group. Nevertheless, as mentioned in the methods, the fact that the monolingual versions of the stimuli tested here showed no variation among the participants is a promising indication that their intuitions regarding the structures being tested here are relatively homogenous in each of the languages. However, as mentioned earlier, age of acquisition and proficiency could be playing a role with regard to CS patterns. A related limitation concerns the statistical analyses used in this study, as they are ANOVAs instead of mixed-effects models. Although not employed here, the latter are an additional way to address differences across individuals, which would further aid in addressing the heterogeneity discussed throughout this paper.

To conclude, I would like to recommend a general procedure for including control stimuli in experimental CS research. First, regardless of the syntactic structure under investigation, it is essential to include at least some form of control stimuli in the AJT. If direct comparison control stimuli can be created (e.g., by merely moving the switch point slightly), they can and should be part of the dataset. However, because such comparisons can only ever provide relative acceptability with no indication of unacceptability, unrelated control stimuli should also be included. I recommend including all the types of control stimuli tested here: complex-sentence switches, subject–predicate switches, direct-object switches, pronoun switches, and present–perfect switches.9 The advantage of using all types is that it creates more variety for the set of stimuli, thus aiding in distracting the participant from deciphering what the target structure is. As for the quantity, the number should be equivalent to each set of target stimuli under investigation. For example, a study could be designed using one quarter target stimuli, one quarter direct-comparison control stimuli, one quarter unrelated control stimuli, and one quarter additional filler stimuli. Or, if no direct comparison can be made of the target, then the sets can be divided into thirds. Once the data has been collected from the AJT, participants should be grouped based on whether they find the expected distinction between the unrelated control stimuli. The individuals who find no distinction between the acceptable and unacceptable control stimuli should be either isolated or removed from the target data analysis. Within said analysis, the acceptable and unacceptable stimuli should be used as a baseline to compare whether the target stimuli (and comparison control stimuli) with regard to acceptability. By following these steps, experimental CS research can more effectively remedy methodological concerns, specifically that of heterogeneity among participants and the operationalization of (un)acceptability.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Conflicts of Interest

The author declares no conflict of interest.

Appendix A

Task Training

In this study we are interested in finding out cómo funciona el code-switching de inglés a español y vice-versa. Partimos de la idea de que el code-switching is a form of linguistic expression like any other and, therefore, it is subject to rules and restrictions like any other. Las reglas y restricciones que nos interesan no tienen nada que ver con lo que hayas aprendido en la escuela, but rather with the linguistic structures that you have in your mind as a native speaker. Let us give you an example in English:

- (1)

- There is likely that John likes Mary.We will ask you to rate sentences from ‘completely unacceptable’ to ‘completely acceptable’. The sentence you just saw would be ‘completely unacceptable’ because native speakers of English find this sentence very strange. It is perfectly understandable but there is something about its structure that sounds un-English.En cambio, the following sentence sounds completely fine:

- (2)

- There is someone in the garden.Ahora veamos un ejemplo en español:

- (3)

- Esa película le ha gustado a nadie.De nuevo, esta oración no es aceptable. Aunque la entendemos perfectamente, hay algo que suena raro en esta oración, no es una oración en español.Al contrario, esta oración es normalísima.

- (4)

- Juan compró el periódico.Y ahora comparemos two examples in code-switching:

- (5)

- John le bought una casa.Muchos hablantes bilingües de español/inglés who practice code-switching regularly or occasionally agree that sentence (5) sounds strange.Sentence (6), on the other hand, sounds completely fine para los hablantes bilingües.

- (6)

- Mis primos nadaron in the pool for three hours.In the survey, you might find that some sentences are neither perfect nor totally awful. Although we expect that you will evaluate most of the sentences you will read as ‘completely unacceptable’ or ‘completely acceptable’, te damos varias opciones por si hay dudas. We also provide you with an ‘unsure’ option, in case you really, really are not sure.Lee la siguiente oración.

- (7)

- I know my neighbor chewed gum yesterday.This sentence may sound odd because it doesn’t seem like something anyone would ever say or care about. The question is whether this is una oración posible en inglés. Si es el caso, es completamente aceptable.Now, take a moment to rate the following sentence:

- (8)

- He surprise that no one called yesterday.This sentence is comprehensible and the situation seems plausible (una posible situación: ayer él esperaba una llamada, pero al final no lo llamaron), but the sentence is not possible to say in English. It’s just not English, for whatever reason, and therefore it is completely unacceptable.Para juzgar cada oración, the question, then, is whether the sentence is possible in English, Spanish or code-switching, even if you don’t know why anyone would actually say the sentence.And let’s take a look at one final pair of sentences. First:

- (9)

- Compró Juan un nuevo libro for the party this week?En cuanto al significado, this sentence is a little odd. You don’t usually buy a book for a party. Pero como no hay nada raro en la forma de la oración, it would be completely acceptable.Second:

- (10)

- I want ir al mercado.Esta oración, on the other hand, se puede entender pero no se puede decir. Because of that, it would be completely unacceptable.

Appendix B

Complex-Sentence Switch Stimuli

Todos van a mojarse if it rains today.‘Everyone will get wet if it rains today.’Ella se esconde when he calls her.‘She hides when he calls her.’Voy a salir if I feel sick.‘I am going to leave if I feel sick.’Sometimes he’ll go to the store y olvida lo que estaba buscando.‘Sometimes he’ll go to the store and forget what he was looking for.’We’ll hear a sound si alguien toca el timbre.‘We’ll hear a sound if someone rings the doorbell.’We’ll tell him si lo vemos.‘We’ll tell him if we see him.’

Subject–Predicate Switch Stimuli

Casi nadie visits the museum.‘Almost no one visits the museum.’Ninguna persona aquí has a knife.‘No person here has a knife.’El mapa costs six dollars.‘The map costs six dollars.’Her entire family habla español.‘Her entire family speaks Spanish.’My brother está pescando.‘My brother is fishing.’The bear ya no ha muerto.The bear hasn’t died yet.

Direct-Object Switch Stimuli

Sólo tengo five dollars.‘I only have five dollars.’No les han dado an opportunity to leave.‘They haven’t given them an opportunity to leave.’Van a hacer a lot of different activities.‘They are going to do a lot of different activities.’He has una mala reputación.‘He has a bad reputation.’The earthquake destroyed la ciudad y los suburbios.‘The earthquake destroyed the city and the suburbs.The man ate un sándwich de atún.‘The man ate a tuna sandwich.’

Pronoun Switch Stimuli

Él met our grandmother.‘He met our grandmother.’He pidió una cerveza.‘He ordered a beer.’Ellos bought some peaches.‘They bought some peaches.’They compraron unas manzanas.‘They bought some apples.’Ellas started to sing.‘They started to sing.’She conoció a nuestro primo.‘She met our cousin.’

Present–Perfect Switch Stimuli

Su hermano ha trained at the gym every day.‘His brother has trained at the gym every day.’The students have prestado atención a la profesora hoy.‘The students have paid attention to the professor today.’Nuestra tía ha taught fourth grade at the elementary school.‘Our aunt has taught fourth grade at the elementary school.’Her colleagues have visto muchas películas this year.‘Her colleagues have seen many movies this year.’Sus amigas han gone shopping with their mothers recently.‘Their friends have gone shopping with their mothers recently.’Your neighbors have comido en ese restaurante varias veces.‘Your neighbors have eaten in that restaurant several times.’

Present–Progressive Switch Stimuli

Su hermano está training at the gym right now.‘His brother is training at the gym right now.’The students are prestando atención a la profesora mucho.‘The students are paying attention to the professor a lot.’Nuestra tía está teaching biology at the high school.‘Our aunt is teaching biology at the high school.’Her colleagues are viendo muchas películas este mes.‘Her colleagues are watching many movies this month.’Sus amigas están going shopping with their mothers this weekend.‘Their friends are going shopping with their mothers this weekend.’Your neighbors are comiendo en ese restaurante ahora mismo.Your neighbors are eating in that restaurant right now.’

Filler Stimuli

Susana y él met our uncle.‘Susan and him met our uncle.’Ese chico met our cousin.‘That boy met our cousin.’Lisa and him pidieron dos copas de vino.‘Lisa and him ordered two glasses of wine.’That guy pidió un vaso de agua.‘That guy ordered a glass of water.’Tú y ellos bought some oranges.‘You and them bought some oranges.’Esos hombres bought some apples.Those guys bought some apples.’You and them compraron unas naranjas.‘You and them bought some oranges.’Those guys compraron unos duraznos.Those guys bought some peaches.’Esos chicos y ellas started to laugh.‘Those boys and them started to laugh.’Esas chicas started to dance.‘Those girls started to dance.’Michael and her conocieron a nuestra tía.‘Michael and her met our aunt.’That girl conoció a nuestra abuela.‘That girl met our grandmother.’Su hermano trains at the gym regularly.‘His brother trains at the gym regularly.’The students prestan atención a la profesora en clase.‘The students pay attention to the professor in class.’Nuestra tía teaches psychology at the community college.‘Our aunt teaches psychology at the community college.’Her colleagues ven muchas películas en el cine.‘Her colleagues see many movies in the theater.’Sus amigas go shopping with their mothers frequently.‘Their friends go shopping with their mothers frequently.’Your neighbors comen en ese restaurante todas las semanas.‘Your neighbors eat at that restaurant every week.’

References

- Badiola, Lucía, and Ariane Sande. 2018. Gender assignment in Basque/Spanish mixed Determiner Phrases: A study of simultaneous bilinguals. In Code-switching—Experimental Answers to Theoretical Questions: In Honor of Kay González-Vilbazo. Edited by Luis López. Philadelphia: John Benjamins, pp. 15–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Badiola, Lucía, Rodrigo Delgado, Ariane Sande, and Sara Stefanich. 2018. Code-switching attitudes and their effects on acceptability judgment tasks. Linguistic Approaches to Bilingualism 8: 5–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Balam, Osmer. 2016. Mixed verbs in contact Spanish: Patterns of use among emergent and dynamic bi/multilinguals. Languages 1: 3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bartlett, Laura, and Kay González-Vilbazo. 2010. Classifiers in Spanish-Taiwanese code-switching. In Proceedings from the Annual Meeting of the Chicago Linguistic Society. Chicago: Chicago Linguistic Society, pp. 1–15. [Google Scholar]

- Belazi, Hedi M., Edward J. Rubin, and Almeida Jacqueline Toribio. 1994. Code switching and X-bar theory: The functional head constraint. Linguistic Inquiry 25: 221–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bentahila, Abdelâli, and Eirlys E. Davies. 1983. The syntax of Arabic-French code-switching. Lingua 59: 301–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cantone, Katja Francesca, and Jeff MacSwan. 2009. Adjectives and word order: A focus on Italian-German codeswitching. In Multidisciplinary Approaches to Code Switching. Edited by Ludmila Isurin, Donald Winford and Kees de Bot. Amsterdam: John Benjamins, pp. 243–77. [Google Scholar]

- Cardinaletti, Anna, and Michal Starke. 1999. The typology of structural deficiency: A case study of the three classes of pronouns. In Clitics in the languages of Europe. Edited by Henk C. van Riemsdijk. Berlin: De Gruyter, pp. 145–233. [Google Scholar]

- Chomsky, Noam. 1986. Knowledge of Language: Its Nature, Origin, and Use. Westport: Greenwood Publishing Group. [Google Scholar]

- De Houwer, Annick. 1998. By way of introduction: Methods in studies of bilingual first language acquisition. International Journal of Bilingualism 2: 249–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Delgado, Rodrigo. 2018. The familiar and the strange: Gender assignment in Spanish/English mixed DPs. In Code-Switching—Experimental Answers to Theoretical Questions: In honor of Kay González-Vilbazo. Edited by Luis López. Philadelphia: John Benjamins, pp. 39–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Nicolás, Irati, and Jon Robledo. 2018. Adjective placement in Spanish and Basque mixed DPs. In Code-Switching—Experimental Answers to Theoretical Questions: In Honor of Kay González-Vilbazo. Edited by Luis López. Philadelphia: John Benjamins, pp. 63–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ebert, Shane. 2014. The Morphosyntax of Wh-questions: Evidence from Spanish-English Code-Switching. Ph.D. dissertation, University of Illinois at Chicago, Chicago, IL, USA, May 7. [Google Scholar]

- Ebert, Shane, and Bradley Hoot. 2018. That-trace effects in Spanish-English code-switching. In Code-Switching—Experimental Answers to Theoretical Questions: In Honor of Kay González-Vilbazo. Edited by Luis López. Philadelphia: John Benjamins, pp. 101–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ebert, Shane, and Bryan Koronkiewicz. 2018. Monolingual stimuli as a foundation for analyzing code-switching data. Linguistic Approaches to Bilingualism 8: 25–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Finer, Daniel L. 2014. Movement triggers and reflexivization in Korean-English codeswitching. In Grammatical Theory and Bilingual Codeswitching. Edited by Jeff MacSwan. Cambridge: MIT Press, pp. 37–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giancaspro, David. 2015. Code-switching at the auxiliary-VP boundary. Linguistic Approaches to Bilingualism 5: 379–407. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- González-Vilbazo, Kay, and Bryan Koronkiewicz. 2016. Tú y yo can codeswitch, nosotros cannot: Pronouns in Spanish-English codeswitching. In Spanish-English Codeswitching in the Caribbean and the US. Edited by Rosa E. Guzzardo Tamargo, Catherine M. Mazak and M. Carmen Parafita Couto. Philadelphia: John Benjamins, pp. 237–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- González-Vilbazo, Kay, and Luis López. 2011. Some properties of light verbs in code-switching. Lingua 121: 832–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- González-Vilbazo, Kay, and Luis López. 2012. Little v and parametric variation. Natural Language & Linguistic Theory 30: 33–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- González-Vilbazo, Kay, and Sergio E. Ramos. 2018. Codeswitching. In The Oxford Handbook of Ellipsis. Edited by Jeroen van Craenenbroeck and Tanja Temmerman. Oxford: Oxford University Press, pp. 458–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- González-Vilbazo, Kay, Laura Bartlett, Sarah Downey, Shane Ebert, Jeanne Heil, Bradley Hoot, Bryan Koronkiewicz, and Sergio E. Ramos. 2013. Methodological considerations in code-switching research. Studies in Hispanic and Lusophone Linguistics 6: 119–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grimstad, Maren Berg, Brita Ramsevik Riksem, Terje Lohndal, and Tor A. Åfarli. 2018. Lexicalist vs. exoskeletal approaches to language mixing. The Linguistic Review 35: 187–218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grosjean, François. 1998. Studying bilinguals: Methodological and conceptual issues. Bilingualism: Language and Cognition 1: 131–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gullberg, Marianne, Peter Indefrey, and Pieter Muysken. 2009. Research techniques for the study of code-switching. In The Cambridge Handbook of Linguistic Code-Switching. Edited by Barbara E. Bullock and Almeida Jacqueline Toribio. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, pp. 21–39. [Google Scholar]

- Guzzardo Tamargo, Rosa E., and Paola E. Dussias. 2013. Processing of Spanish-English code-switches by late bilinguals. In BUCLD 37: Proceedings of the 37th Annual Boston University Conference on Language Development. Edited by Sarah Baiz, Nora Goldman and Rachel Hawkes. Boston: Cascadilla Press, pp. 134–46. [Google Scholar]

- Jansen, Veronika, Jasmin Müller, and Natascha Müller. 2012. Code-switching between an OV and a VO language: Evidence from German-Italian, German-French and German-Spanish children. Linguistic Approaches to Bilingualism 2: 337–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koronkiewicz, Bryan. 2014. Pronoun Categorization: Evidence from Spanish/English Code-Switching. Ph.D. dissertation, University of Illinois at Chicago, Chicago, IL, USA, April 21. [Google Scholar]

- Koronkiewicz, Bryan, and Shane Ebert. 2018. Modality in experimental code-switching research. In Code-switching—Experimental Answers to Theoretical Questions: In Honor of Kay González-Vilbazo. Edited by Luis López. Amsterdam: John Benjamins Publishing, pp. 147–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liceras, Juana M., Raquel Fernández Fuertes, Susana Perales, Rocío Pérez-Tattam, and Kenton Todd Spradlin. 2008. Gender and gender agreement in bilingual native and non-native grammars: A view from child and adult functional-lexical mixings. Lingua 118: 827–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- MacSwan, Jeff. 1999. A Minimalist Approach to Intrasentential Code Switching. New York: Garland. [Google Scholar]

- MacSwan, Jeff, ed. 2014. Programs and proposals in codeswitching research: Unconstraining theories of bilingual language mixing. In Grammatical Theory and Bilingual Codeswitching. Cambridge: MIT Press, pp. 1–33. [Google Scholar]

- MacSwan, Jeff, and Kara T. McAlister. 2010. Naturalistic and elicited data in grammatical studies of codeswitching. Studies in Hispanic and Lusophone Linguistics 3: 521–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Montrul, Silvina, and Roumyana Slabakova. 2003. Competence similarities between native and near-native speakers: An investigation of the preterite/imperfect contrast in Spanish. Studies in Second Language Acquisition 25: 351–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Neill, Robert, Edwin T. Cornelius, and Gay N. Washburn. 1981. American Kernal Lessons: Advanced Student’s Book. London: Longman. [Google Scholar]

- Poplack, Shana. 1980. Sometimes I’ll start a sentence in Spanish y termino en español: Toward a typology of code-switching. Linguistics 18: 581–618. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sande, Ariane. 2018. C Plus T as a Necessary Condition for pro-drop: Evidence from Code-Switching. Ph.D. dissertation, University of Illinois at Chicago, Chicago, IL, USA, November 7. [Google Scholar]

- Sprouse, Jon. 2007. Continuous acceptability, categorical grammaticality, and experimental syntax. Biolinguistics 1: 123–34. [Google Scholar]

- Sprouse, Jon. 2008. Magnitude estimation and the non-linearity of acceptability judgments. In Proceedings of the 27th West Coast Conference on Formal Linguistics. Edited by Natasha Abner and Jason Bishop. Somerville: Cascadilla Proceedings Project, pp. 397–403. [Google Scholar]

- Sprouse, Jon, and Diogo Almeida. 2012. Assessing the reliability of textbook data in syntax: Adger’s Core Syntax. Journal of Linguistics 48: 609–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sprouse, Jon, Carson T. Schütze, and Diogo Almeida. 2013. A comparison of informal and formal acceptability judgments using a random sample from Linguistic Inquiry 2001–2010. Lingua 134: 219–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stadthagen-González, Hans, Luis López, and M. Carmen Parafita Couto. 2018. Using two-alternative forced choice tasks and Thurstones’s law of comparative judgments for code-switching research. Linguistic Approaches to Bilingualism 8: 67–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Timm, Lenora A. 1975. Spanish-English code-switching: El porque and how-not-to. Romance Philology 28: 473–82. [Google Scholar]

- van Hell, Janet G., Carla B. Fernández, Gerrit Jan Kootstra, Kaitlyn A. Litcofsky, and Caitlin Y. Ting. 2018. Electrophysiological and experimental-behavioral approaches to the study of intra-sentential code-switching. Linguistic Approaches to Bilingualism 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Woolford, Ellen. 1983. Bilingual code-switching and syntactic theory. Linguistic Inquiry 14: 520–36. [Google Scholar]

| 1 | See Koronkiewicz and Ebert (2018) for evidence against such a potential bias presenting itself in an experimental CS context. |

| 2 | See the aforementioned work on methodological concerns for discussion of how specifically such factors can affect research, including De Houwer (1998), González-Vilbazo et al. (2013), Grosjean (1998), Gullberg et al. (2009), and others. |

| 3 | Given that stimuli were presented visually, not aurally, the prosody of the sentences was left uncontrolled. However, following Koronkiewicz and Ebert (2018), there is evidence to suggest that the modality of presentation does not affect the participants’ acceptability judgments, including pronouns. |

| 4 | Examination found no pronoun or present–perfect switches in the Bangor Miami corpus. |

| 5 | It is worth noting that switches with haber as a light verb are prevalent in some bilingual communities, such as in Northern Belize (Balam 2016), but such a switch is a distinct syntactic construction to the one discussed here. |

| 6 | All filler stimuli included subject–predicate switches, with the subject being either a lexical Determiner Phrase or a pair of coordinated pronouns. The fact that they were all the same type of switch was unintentional. |

| 7 | The error bars in all of the figures represent the standard error for each respective mean rating. |

| 8 | See Badiola et al. (2018) for more details about how CS attitudes can affect AJT ratings. |

| 9 | It is possible that the specific language pair(s) being tested may require the exclusion of one or more of these types for syntactic reasons specific to the grammar(s) of one or more languages involved. |

© 2019 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).