Abstract

The brevity maxim of Gricean pragmatics states that unnecessary prolixity should be avoided. We report a case in which 5-year-old children’s performance conforms better to Grice’s maxim than adults’ behavior. Our data come from a semi-spontaneous German relative clause production study that we carried out with 5- and 7-year-old children as well as adults. In particular, we focus on the pragmatics of the passive predicates that were produced. These constituted about a third of both child and adult productions in items that targeted an object relative clause structure. Since the expression of the agent is syntactically optional with passive predicates, the brevity maxim predicts that the agent should only be expressed when it is informative. We compare two conditions to test this prediction: one where the agent is informative and one where it is not. We find that 5-year-old children display significantly greater sensitivity to the brevity maxim than adults do. In two follow-up studies, we show that adults’ violations of brevity cannot be explained by priming of by-phrases expressing the agent and that there is an effect of age within children as well.

1. Introduction

Competent speakers of a language use language in pragmatically efficient ways. (Grice 1975, 1989) initiated a research program to formulate general principles that he called maxims that describe what is meant by pragmatic efficiency. Of particular relevance to the present paper are three of Grice’s maxims that we refer to as Quantity 1, Quantity 2, and Brevity in the following. Grice’s maxims of quantity state that both underinformative (Quantity 1) and overinformative (Quantity 2) utterances are not felicitous. Brevity, Grice’s third maxim of manner, states that shorter utterances should be preferred over longer ones. Although Grice’s research concerned adults, his results have also been useful for investigating other populations, especially since the experimental methods became more accessible for linguistic research (Chemla and Singh 2014; Noveck and Reboul 2008; Sauerland and Schumacher 2016).

Children’s pragmatic abilities have been a focus of research since soon after Grice’s groundbreaking work. Most of the work has focused on Grice’s maxims of quantity and quality. Specifically, Noveck (2001) claims that children behave more logically (and thereby less pragmatically) than adults with respect to quantity. One of Noveck’s (2001) experiments shows that children as old as 10 accept underinformative sentences more frequently than adults do. Noveck applies a truth value judgment paradigm in his experiments. Underinformative sentences in this context are semantically true but pragmatically odd sentences, such as Some giraffes have long necks. For such sentences, Noveck reports higher rates of acceptance among children. Many recent experiments using different experimental techniques targeting children’s comprehension confirm Noveck’s general result across more than 30 languages (Barner et al. 2011; Gualmini et al. 2001; Guasti et al. 2005; Huang and Snedeker 2009; Katsos and Bishop 2011; Katsos et al. 2016; Papafragou and Musolino 2003) that children—for the most part, children aged 3 to 6—are less sensitive to underinformativity in some language comprehension tasks. Davies and Katsos (2010) also corroborate Noveck’s finding in the course of a production study involving children. The findings from quantity raise the question of whether children in general are less sensitive to pragmatics and more logical than adults or whether a factor other than sensitivity to pragmatics causes children’s performance.1 One way of addressing this question is to look at the other maxims of Grice in language acquisition.

In this paper, we report data from three experiments that we carried out to examine whether children are sensitive to brevity, one of Grice’s Manner Maxims, using an elicitation experiment of relative clauses. Grice (Grice 1975, p. 46) states the brevity maxim as follows: Be brief (avoid unnecessary prolixity). One example showing the effect of the maxim is (1).2

- (1)

- Mary wrote a book that she wrote.

In (1), the relative clause that she wrote is not informative because the main clause already specifies that the book was written by Mary. The information that (1) conveys could be conveyed by the shorter sentence Mary wrote a book. For this reason, (1) is felt to be slightly odd.3 Recent theoretical work by Meyer (2013) and Marty (2017) and, within a relevant theoretic perspective, the contributions in (Goldstein 2013) identify brevity as playing an important role in sentence pragmatics, but it has hardly been investigated at all in acquisition.

The Manner Maxims overall have not been investigated as much as the first quantity maxim within child language, as Clark and Kurumada (2013) and Wilson (2017) report. More specifically, to the best of our knowledge, the maxim of brevity has not been investigated experimentally in first-language acquisition at all: Clark and Kurumada (2013) discuss brevity solely based on child language corpora, and restrict their attention to general correlations of utterance length and vocabulary size. What did they find? Clark and Kurumada (2013) report that the mean length of utterance (MLU) of 3-, 4-, and 5-year-old children is highest in the 4-year-old group in the corpora they investigated, but that the ratio between the number of different words that were used and the total number of words used increases monotonically with age. They suggest that their finding supports the claim that 5-year-olds are more capable of making their utterances concise, i.e. an increasing adherence to brevity. The data Clark and Kurumada (2013) are consistent with their interpretation, but in our view other explanations are possible. For example, children’s adherence to brevity may be constant, or even decline, but as their expressive vocabulary grows, they may have more lexical resources at their disposal to express themselves concisely. We therefore put aside further discussion on Clark and Kurumada (2013) in the following, but heed to their call to conduct more research in the domain of brevity.

A more advanced line of research related to brevity addresses overinformativity. Overinformativity violates Grice’s second maxim of quantity (Do not make your contribution more informative than required.) Brevity and overinformativity are closely related, and Grice (1975) already notes that some cases of the violation of the second quantity maxim may be subsumed under the brevity maxim.4 We discuss previous studies on overinformativity (Davies and Katsos 2010 2013; Engelhardt et al. 2006) in Section 4.

This paper is structured as follows: In Section 2, we introduce the necessary linguistic background on German relative clauses and passives in the context of Grice’s pragmatic maxims. In Section 4, Section 5 and Section 6, we present three experimental studies investigating children’s and adults’ use of passives in relative clauses. In particular, we investigate to what extent brevity constrains the production of the optional by-phrase expressing the agent in all three experiments. The first experiment compares 5-year-old children with adults in the same design, eliciting more pragmatic performance from children with respect to brevity. We discuss three different potential analyses of the finding from Experiment 1 and, in the following section, report two follow-up experiments designed to test the three analyses. Experiment 2 applies a slightly modified version of Experiment 1 to adults to rule out a possible confounding factor for adult performance. Finally, in Experiment 3, we apply the design from Experiment 1 to slightly older children.

In the concluding Section 7, we summarize our finding that the difference between children’s and adults’ behavior in Experiment 1 shows that children appear to be more sensitive to brevity than adults. Our finding seems therefore in direct conflict with the established finding that children appear to be less sensitive to pragmatics when it comes to quantity (Noveck 2001 and others). The conflict between quantity and brevity shows that general pragmatic sensitivity cannot explain the children’s behavior. Following Noveck (2001), we propose that an underlying factor of cognitive resources and, for our results specifically, working memory underly the divergence between children’s and adults’ pragmatic behavior. The maxims of quantity and brevity access cognitive resources differently. Roughly speaking, whereas the derivation of an implicature from quantity requires cognitive resources (De Neys and Schaeken 2007; Noveck 2001), the consideration of brevity saves cognitive resources. We propose that children are more inclined than adults to apply brevity because children have more limited cognitive resources, and hence, derive benefits from being brief.5

2. The Pragmatics of Passives in Relative Clauses in German

The three experiments we report in the present paper all concern passives in German relative clauses. German differs from English with respect to case morphology present in German, word-order differences, and in other ways, but overall German is quite similar to English. We briefly introduce the relevant syntactic and pragmatic properties as well as the morpho-syntactic terminology most relevant for our purposes.6

Let us first discuss the structure of relative clauses. Consider (2). The object of the verb kennen ‘know’ in (2) is the relative clause das Mädchen, das den Papa umarmt “the girl that hugs the papa”. The German relative clause consists of an external head of the relative clause (das Mädchen), the relative pronoun that matches in gender and number with the head of the relative clause, and matches in case with the argument position where the gap is (das), and the relative clause (___ den Papa umarmt). We indicate where the gap is with an underscore.

- (2)

- Ich kenne das Mädchen, das ___ den Papa umarmt.I know the.neut girl, who.neut the.acc papa hugs“I know the girl who hugs Papa.”

It is also possible to relativize the object of the relative clause in German. The object relative counterpart of (2) is shown in (3).

- (3)

- Ich kenne das Mädchen, das der Papa ___ umarmt.I know the.neut girl, who.neut the.nom papa hugs“I know the girl whom Papa hugs.”

Please note that German is a verb-final language, and the tensed verb appears at the end of the clause in embedded clauses. Because of this, the relative clause, when it contains nothing other than the in situ argument and the verb, the surface word order is always argument-verb, regardless of whether the argument is subject or object.

Because of syncretism, definite determiners and relative pronouns share the same morphological forms in nominative and accusative case, as shown in (4). Definite determiners and relative pronouns are identical for singular nouns in nominative, accusative, and dative forms in all genders. In the plural, nominative and accusative are homophonous, although the dative differs (den [definite determiner] vs. denen [relative pronoun]).7

| (4) | Nominative | Accusative | Dative | |

| Masculine, singular | der | den | dem | |

| Feminine, singular | die | die | der | |

| Neuter, singular | das | das | dem | |

| Plural | die | die | den/denen |

The combination of the word order and the head of the relative clause being ambiguous between nominative and accusative creates a temporary ambiguity when the head of the relative clause is a singular feminine or singular neuter noun, which could be resolved by the case of the relative clause-internal argument in (2) and (3), if the argument is a singular masculine noun, or by verbal morphology (singular vs. plural), if the head of the relative clause and the relative clause-internal argument do not match in number.

It was observed that both adults and children have difficulties comprehending relative clauses with a gap in the object position of the relative clause (object relatives) as compared with those with a gap in the subject position (subject relatives) in languages such as English and German (adults: (Bader and Meng 1999; Frazier 1987; Schriefers et al. 1995), and others cited therein; children: (Arosio et al. 2012; de Villiers et al. 1979; Friedmann et al. 2009), among others). Furthermore, Arosio et al. (2012) found that the type of morphosyntactic cue that disambiguates subject relatives from object relatives affects the comprehension of an object relative clause, modulated by the amount of phonological working memory, measured by forward digit span.

Let us next consider the passive construction. German, like English, has (at least) two forms of passives: one with the von-phrase (by-phrase) and one without, as shown in (5). Again, putting aside the exact syntactic analysis of the passive construction, what is important for our purposes is that the passive construction can be characterized as follows: (i) the theme/patient argument raises to the subject position from the object position; (ii) the agent argument becomes optional; and (iii) when the agent argument is overtly expressed, it is accompanied by the preposition von in German, as shown in (5-a).

| (5) | a. | Das Mädchen wird von dem Papa geküsst. | |

| the.neut girl become.3.sg by the.masc.dat Papa part.kiss | |||

| “The girl is kissed by the father.” | Full Passive | ||

| b. | Das Mädchen wird geküsst. | ||

| the.neut girl become.3sg part.kiss | |||

| “The girl is kissed.” | Short Passive |

Previous studies observe that (i) children’s acquisition of passive structures seems delayed compared to that of actives (Armon-Lotem et al. (2016); Gordon and Chafetz (1990); Turner and Rommetveit (1967) and many others), and (ii) full passives may be acquired later than short passives (Armon-Lotem et al. (2016); Fox and Grodzinsky (1998)) in comprehension as well as production (although see Crain et al. (2009) who show that even children as young as 3–4 produced full passives in their elicitation experiment). Corpus studies show that passives are very infrequent in both input by adults (0.36% of all utterances; Crawford (2012); Gordon and Chafetz (1990)) and output by children (0.12% of all utterances; Crawford (2012); Pinker et al. (1987)), although elicitation/production experiments have shown that infrequencies in corpus data do not implicate lack of acquisition of passive structures (Crain et al. (2009) and others).

In this paper, we are interested in whether we could predict the use of a by-phrase by speakers. At first glance, the use of a by-phrase in the passive construction seems optional: The sentence is grammatical with or without the by-phrase. In what follows, let us call the passive construction with the by/von-phrase the Full Passive (e.g., (5-a)) and the passive construction without a by/von-phrase the Short Passive (e.g., (5-b))8

How does a speaker decide whether to use the by-phrase? Let us assume that, in general, whenever there are alternatives to choose from (here, the full and the short passive), a speaker chooses the sentence that satisfies pragmatic principles. Although different concrete theoretical proposals exist regarding what these pragmatic principles may be (e.g., (Horn 1984) Q and R maxims, Relevance theory (Sperber and Wilson 1986), or (Meyer 2013; 2015) Efficiency), we adopt the approach of Grice (1989) for the ease of exposition. Specifically, as we discussed above, the two pragmatic Gricean Maxims govern the choice between structures with and without a by-phrase:

- Quantity 1: Make your contribution as informative as is required

- Brevity (Manner 3): Be brief (avoid unnecessary prolixity)

The maxim of Quantity 1, on the one hand, tells the speaker to provide as much information as he/she can, without being false. This maxim requires speakers not to be underinformative. The brevity maxim, on the other hand, tells the speaker to use as short an expression as possible. This requirement, then, tells the speaker not to use words that are not necessary. Furthermore, Grice’s restriction of unnecessary prolixity establishes that Quantity 1 takes precedence over brevity when the two conflict. The need for this ranking of the two maxims is obvious from the observation that no utterances at all are predicted if brevity was ranked higher than Quantity 1, since brevity is maximally satisfied if the speaker does not say anything. Grice’s two principles combined as above make predictions about when the full and short passives should be used, as we explain in the following.

2.1. Full Passive Context

Let us assume that there are two potential agents (the father and the grandfather), one potential action (kiss), and one potential patient (a boy). Let us further assume that the following two situations are equally likely and that the speaker must report which event happened.

| (6) | a. | The father kisses a boy. |

| b. | The grandfather kisses a boy. |

When a speaker chooses to describe the event with an active sentence, he/she would utter either (6-a) or (6-b). There is no option with respect to whether the agent or patient would be overtly expressed, because kiss is a transitive verb that requires two overt arguments in an active voice. When the speaker uses the passive construction, on the other hand, he/she has an option to choose from either a full passive with a by-phrase or a short passive, as in (7-a) and (7-b), respectively.

| (7) | a. | A boy is kissed by the father. |

| b. | A boy is kissed. |

Please note that the short passive in (7-b) is true in both possible situations in (6). The full passive (7-a), on the other hand, is compatible only with situation (6-a) in which the agent is the father. Quantity 1 says that enough information must be provided. Given that (7-b) is compatible with the situation in which the agent is the father, as well as the situation in which the agent is the grandfather, (7-b) does not distinguish the two situations. To disambiguate the two situations, the by-phrase is necessary. Brevity does not rule out (7-a), either, because a by-phrase is necessary to describe the situation uniquely.

In other words, pragmatic maxims dictate that the by-phrase is necessary for disambiguation in certain contexts, and only then should its use be licensed. This is when there are two potential agents, and overtly expressing the agent is necessary for disambiguation.

2.2. Short Passive Context

Let us now assume that there is only one potential agent (the father), two potential actions (kiss and hug), and one patient (a boy). In this context, the two possible situations are as follows:

| (8) | a. | The father kisses a boy |

| b. | The father hugs a boy |

Again, if a speaker chooses to describe the event with an active sentence, he/she must overtly express both the subject and the object. How about in the passive voice, though? Let us assume that (8-a) is true. Then the two types of passives that could be uttered are as in (9).

| (9) | a. | A boy is kissed by the father. |

| b. | A boy is kissed. |

Now, the lexical item that distinguishes one situation from the other is not the agent but the verb. Both (9-a) and (9-b) are true in (8-a), and neither is true in the (8-b) situation. From this perspective, the use of a by-phrase is not necessary for disambiguation. When the by-phrase is not necessary for disambiguation purposes, the brevity maxim says that speakers should use the shorter expression with still enough information to describe the situation uniquely—namely, the short passive.

To summarize, if the choice between full and short passives is determined by pragmatic principles (Quantity 1 and Brevity), we expect that a speaker should produce:

- the short passive when the addition of a by-phrase does not add to the informativeness of the sentence; and

- the full passive when the addition of the by-phrase adds to the informativeness.

We conducted an experiment to examine whether these predictions are corroborated as described in Section 4.

3. Previous Studies

To test the predictions of Quantity 1 and brevity in the production of passive/by-phrase, we used an experimental design that elicits production of relative clauses in controlled contexts.

Our work on brevity is related to previous work that investigates to what extent adults producing overinformative referential expressions, such as the description the apple on the towel instead of simply the apple in a scenario where there is only one apple that could be referred to (Engelhardt et al. 2006). First, consider the question of how this work relates to Grice’s theory. The previous studies on the use of unnecessary material in reference appeal to the Quantity 2 maxim. As we mentioned above, brevity and Quantity 2 often overlap in their effects but there are cases in which the two make different predictions. Considering such cases, we feel that it may be more appropriate to appeal to brevity in cases of reference as well for the following reason. Consider a scenario where there is a single referent, a fresh apple. Compare the two definite descriptions the apple and the fresh apple in such a one-referent scenario. The two definite descriptions differ not in the novel information they provide but in their presupposition. Therefore, neither of the two descriptions is actually more informative. Furthermore, when adjectives contribute novel information they are generally acceptable even in one-referent scenarios. For example, evaluative adjectives such as tasty tend to be interpreted as part of the presupposition even when then occur in definite descriptions, and their content is not used for referent identification, but can provide new information. Correspondingly, evaluative adjectives can be used in definite descriptions when their evaluative content is relevant, as in Where did you find the tasty apple? (Marty 2017 and others). In addition, finally, the Quantity 2 account predicts that the fruit (or even the fruit or animal) should be preferred over the apple in a scenario containing only a single fruit, but possibly other non-fruit items. However, the description the fruit is not actually used in such scenarios, as Davies and Katsos (2013) show in their Experiment 3. An appeal to brevity, on the other hand, correctly does not predict that fruit should be preferred over apple.

Putting aside the question of whether Quantity 2 or brevity is the correct theoretical account for the choice of referential expressions, the previous literature on reference is also inconclusive because of conflicting results. Engelhardt et al. (2006) was one of the first studies to experimentally investigate whether speakers would use an expression (prepositional phrase) that is overinformative, on the one hand, and whether hearers’ processing would be affected by overinformative expressions, on the other. Davies and Katsos (2010, 2013) investigated the production and processing of redundant adjectives. Specifically, they test whether adults use an adjective such as red to describe an apple that is red when there is only one apple in the context. In contrast to (Engelhardt et al. 2006), they report that the adjective red is not used when it is not necessary for unambiguously identifying which apple the speaker is talking about. However, Davies and Katsos (2013) can only speculate about why Engelhardt et al. (2006) arrived at different findings. Specifically, they mention that the salience of specific features in the visual displays that both Engelhardt et al. (2006) and Davies and Katsos (2013) used in their studies affect the results of these studies. Since our study did not use visual stimuli, this discussion does not apply to our method. Because of the conflicting findings reported by Engelhardt et al. (2006) and Davies and Katsos (2013), we leave it for another opportunity to address these results in detail; here, we focus on our own results.

Now, consider previous work on passive elicitation with children. There were previous studies that observed children’s production of passives. Regarding English, Crain et al. (2009) used a wh-question production task to elicit full passives. In their study, there were two or three characters in a story, as illustrated in (10) and (11). One experimenter asked the child to ask a question to the second experimenter, as shown in (10) and (11). Crain et al. (2009) report that 29 of 32 children used a full passive (as in (10) and (11)) at least once in their study, but the authors did not focus on the difference between the two- and three-character designs that may trigger different types of passives.

| (10) | two-character design, (Crain et al. 2009, p. 126) | |

| Exp.: | OK, there is this big heavy bus, and it is coming along and it crashes into one of the cars. You ask Keiko which car. | |

| Child: | Which car gets crashen by the big bus? (adult: Which car gets crashed into by the big bus.) | |

| (11) | three-character design, (Crain et al. 2009, p. 126) | |

| Exp.: | See, the Incredible Hulk is hitting one of the soldiers. Look over here. Darth Vader goes over and hits a soldier. So Darth Vader is also hitting one of the soldiers. You ask Keiko which one. | |

| Child: | Which soldier is getting hit by Darth Vader? | |

Regarding Italian, Guasti et al. (2012) use a similar design to that of Crain et al. and observe that both adults and children seem to avoid producing wh-questions that involve an extraction from the object position in Italian. In their study, however, only adults used passive structures, whereas children used resumptive pronouns.

The other environment in which speakers have been observed to produce passive structures is the relative clause. For our design, the most directly relevant previous study was carried out by Belletti (2014). Belletti (2014) observed that Italian children use passives when they are prompted to produce an object relative clause, in a similar fashion as they do with wh-questions, as in (12).

- (12)

- The boy that is kissed by the father

Additionally, Adani et al. (2016) observe that German-speaking children also produce passive structures. None of the previous studies investigated the exact environment in which the by-phrase is produced by adults and children, however.

Why do both children and adults produce passive structures with relative clauses and wh-questions? Previous studies (Avrutin 2000; Sauerland et al. 2016; Seidl et al. 2003, and others) show that sentences involving an A’-extraction from an object position are more difficult for children to comprehend. It could be, then, that producing sentences involving A’-extraction are difficult for speakers as well. This is the direction that Belletti (2014) takes. Following Grillo (2008; 2009) and Friedmann et al. (2009), Belletti (2014) proposes that children have difficulties producing object relative clauses because of the relativized minimality effect. According to this analysis, when children try to extract a DP from the object position, there is another DP with a matching feature ([+N]), namely, the subject. Although the existence of another DP does not result in ungrammaticality for adults, this constrains what can be extracted/moved for children. When the extraction is from the subject position, by contrast, there is no intervening DP, and as a result, children manage to produce/comprehend sentences involving A′-extraction from the subject position. There is an alternative structure for the object relative clauses and object wh-questions, however—namely, passivizing the clause. In a passive sentence, the theme or patient is expressed in the subject position. From this position, then, the extraction to the higher position is possible without the need to cross an intervening DP.

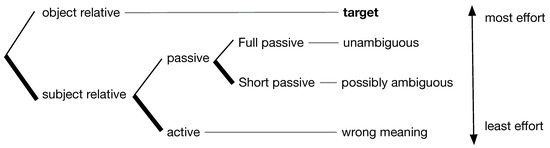

In Figure 1 below, we marked the option that incurs less speaker effort with a thicker line, based on the previous studies we reviewed above: between the object and the subject relatives, production of a subject relative requires less effort; between the active and the passive sentences, the active version requires less effort; between the short and the full passives, the short passive requires less effort.

Figure 1.

Overview of the main structures produced in an elicitation task that targets object relative structure. The structures are ordered by the amount of speaker effort they incur according to the assumptions we justified in the text.

The question we ask is the following: If short passives require less effort (and satisfies brevity), would young children, to whom the effort to produce complex structures matters more, produce mostly short passives? Or would they produce a costlier option, the full passive? The short passives may result in ambiguity, as described in Section 2.1, and because of this, the by-phrase is necessary information in certain environments for disambiguation.

In the following experiments, we adopted a design combining the insights of Crain et al. (2009) and Belletti (2014). As with Crain et al. (2009), we used two types of contexts: one where a short passive suffices to identify a referent (i.e., satisfy quantity), and another where a full passive is required.

4. Experiment 1

4.1. Participants

A total of 20 monolingual German-speaking adults (13 females, 7 males, = 30.4) and 20 monolingual German-speaking 5-year-old children (9 females, 11 males, = 5;6, age range 5;1–5;11) participated in this study. Children were recruited at two daycare centers in Berlin, Germany. Adult participants were recruited at universities in Berlin, Germany, and were personal connections of researchers. All the testing for children was conducted in a quiet room at the daycare center that they attended. For their participation, adult participants received 5 euro, and children received a small toy (such as stickers).9

4.2. Materials and Procedure

We conducted an elicitation experiment of relative clauses, based on the method designed by Labelle (1990) as refined by Novogrodsky and Friedmann (2006). In this task, each participant was told a series of 20 short stories involving two girls/boys (in the case of adults, two women/men). Female participants heard stories about two girls, and male participants heard stories about boys. In each story, the two girls/boys were involved in two different activities (e.g., the grandpa kissing the girl vs. the grandpa hugging the girl). After each story, the participant was asked which girl/boy she/he would rather be and to start their response with Ich möchte lieber das Mädchen/der Junge sein ... (“I would rather be the girl/the boy ...”).10 The items were designed in such a way that the most salient way to continue the sentence would be to produce a relative clause. The instruction to respond in a certain way was repeated after each story to remind the participants of the structure that they were supposed to use. The full list of items that we used for girls can be seen in the Appendix A.

There were two parameters (subject vs. object relatives; change of protagonists vs. change of verbs), resulting in four conditions. There were five items per condition, resulting in 20 test items in total per participant. The order of the items was randomized, and all the participants received the same order. The testing was done individually in a quiet room.

The two conditions that elicited object relatives targeted different types of passives. When two different verbs were used to describe two different propositions, the agent remained the same, and hence, the participants were expected to produce short passives, if they resorted to producing passives to avoid producing the target object relatives (the short passive context). When two different agents were used to describe two different propositions, the verb remained the same, and hence, the expected passive would be the full passive (the full passive context).

The whole experiment was recorded on a digital audio recorder. After the experimental session was finished, the produced responses, which were written down during the sessions, were entered on a spreadsheet. A trained native speaker from our staff then listened to the audio recordings to check the transcriptions and correct them if necessary.

After checking the recorded and handwritten data, we went through the data and labeled whether the produced form was (i) a target relative clause (active, with a gap in the expected slot in the sentence); (ii) short passive; (iii) full passive; (iv) other types of errors, such as theta-role reversal, in which the theta-role of the gap and the relative clause-internal argument were reversed, among others.

4.3. Results

4.3.1. Overall Results

Of interest are the responses to the items designed to elicit object relatives. Let us first focus on children’s responses. There were 200 tokens in total for which the target response was an object relative clause. Among the 200 tokens, only 9 were of the target form of the relative clause with a gap in the object position as illustrated in (13).

Among the nontarget structures, 61 tokens were what we call the theta-role reversal error, illustrated in (14); 51 tokens were one of the forms of the passive construction as illustrated in (15-a) and (15-b).11 With the theta-role reversal error, participants switched the theta-roles of the relative head and the relative clause-internal argument, and as a result, the produced form was a subject relative clause, rather than the target object relative clause, as shown in (14). With the passive construction, the passivization moves the base-generated object to the subject position, and as a result, what is extracted is the subject of the relative clause, rather than the object.

| (13) | Target | |

| das Mädchen, das der Papa ___ umarmt | ||

| the girl that.neut the.nom.masc Papa hugs | ||

| “the girl that the papa hugs” | ||

| (14) | Theta-role reversal error | |

| das Mädchen, das ___ den Papa umarmt | ||

| the girl that.neut the.acc.masc papa hugs | ||

| “the girl that hugs the papa” | ||

| (15) | Passives | |

| a. | Full passive | |

| das Mädchen, das ___ vom Papa umarmt wird | ||

| the girl that by Papa hugged werden.3.sg | ||

| “the girl that was hugged by the Papa” | ||

| b. | Short passive | |

| das Mädchen, das ___ umarmt wird | ||

| the girl that hugged werden.3.sg | ||

| “the girl that is hugged” | ||

4.3.2. Passive Relatives

Our main interest in this paper is the use of a by-phrase in a passive response. Among the 20 children, 12 children used at least one passive structure. The distribution of the use of passives is shown in Table 1. The eight children who did not produce a single passive construction are not included in Table 1.

Table 1.

Children (5-year-olds): Use of each type of passives per child.

Let us now turn our attention to the environment in which these passives were used. Recall that the use of a by-phrase is obligatory (if the participant uses the passive structure) when there are two potential agents (full passive contexts). The use of a by-phrase is not obligatory when there is only one potential referent and there is no need for disambiguation. The manner maxim would predict that the short passives should be preferred in such a context (short passive contexts). The results for children are summarized in Table 2.

Table 2.

Children (5-year-olds); counts of full and short passive in the full and short passive contexts.

In the full passive context, children produced full passives 25 times and short passives twice. The fact that children used short passives only twice in the full passive context suggests that children used the by-phrase when it was necessary for disambiguating the referent.12 In short passive contexts, however, the picture is somewhat reversed: children produced full passives 9 times, and short passives 15 times. Although more than half of the passives produced in the short passive contexts were short passives, the use of a by-phrase seems not to be completely ruled out in this context.

Fisher’s exact test shows that the difference in distribution of short and full passives in these two contexts is significant (). This suggests that children are making a distinction between the contexts that require the use of a by-phrase from those that do not, which shows sensitivity to the combined effect of quantity and brevity: When the short passive would not have been informative, children produced the full passive as predicted by Quantity 1.

Let us next consider the results from adults. Among the 200 items for eliciting object relatives, the participants produced the target object relatives 63 times and produced one of the passive forms 121 times (60.5%). The distribution of each type of passive in the two types of contexts is shown in Table 3.

Table 3.

Adults, counts of full and short passive in the full and short passive contexts.

Fisher’s exact test shows that the difference in distribution of short and full passives in these two contexts is significant for adults as well (). The data are surprising, though, because adults produce full passives close to two thirds of the time in the short passive construction. The adult data still show a statistical effect of brevity since adults produced 19 short passives in the short passive context. However, 37 full passives were produced in short passive context, violating brevity. If the brevity maxim were at issue here, we would expect them to use only the short passives, when the by-phrase is not required for disambiguation.

Is it the case that children’s and adults’ results show a similar pattern, if both groups show sensitivity to the contexts where the by-phrase is obligatory? When we compared the results from children and adults with respect to whether they used the full or short passives in each context, there was a significant difference between children and adults (Fisher’s exact test: ). Specifically, we see that children produce significantly fewer violations of the brevity principle than adults.

When we compared the results from the short passive context for adults and children, children showed a significantly stronger preference than adults for the short passive in this context (Fisher’s exact test: ). Recall that in the short passive context, only the brevity maxim is at issue. Overtly expressing the by-phrase does not increase the informativity, compared to the short passive alternative, and hence, the use of the short passive should be preferred.

How about the use of a by-phrase when it is obligatory for uniquely identifying the referent? We predicted that adults must use a by-phrase in the full passive context, because without a by-phrase, the relative clause would not have a unique referent. Our result shows that children and adults did not differ significantly in this respect (Fisher’s exact test: ), suggesting that children are also sensitive to the Quantity 1 maxim.

The most interesting finding from Experiment 1 is that children display a significantly stronger effect of brevity than adults. Our next question is why adults frequently used a by-phrase even when it is not necessary in violation of brevity. In the following, we consider three possible explanations for the result of experiment:

- Memory capacity hypothesis: Working memory is shown to affect comprehension of relative clauses for adults and children ((Friederici et al. 1998; Just and Carpenter 1992) among others for adults, measured by reading span task, and (Arosio et al. 20052012; Booth et al. 2000) for children, measured by forward/backward digit-span task.) Our hypothesis is that memory affects production of relative clauses. Adults have more working memory capacity than small children (Gathercole et al. 2004). The reason for the difference between adults’ and children’s production patterns is that because producing the relative clauses is costly, young children need to be economical with respect to the length of the relative clause, in general, but specifically with respect to the use of by-phrases.The length of a sentence is not as critical for adults as it is for children, because adults have more cognitive resources (specifically, working memory) than 5-year-old children (Gathercole et al. 2004).

- Priming hypothesis: The first use of the full passive primes adults to continue using the full passive even in short passive environments, as a spill-over effect.13

- Task effect hypothesis: Another property of the experimental paradigm affects children and adults differently, leading only adults to produce full passives in violation of brevity.

For explanation 2, what may be relevant is that the order of the items in this experiment was pseudo-randomized and balanced. The items eliciting object relatives were interspersed by those eliciting subject relatives, and among the object relative eliciting items, the full and short passive contexts were randomized. It is possible, then, that the first use of the full passive primed the adult speakers to keep using the full passives even when it is not necessary. To address this question, we conducted Experiment 2.

Explanation 3 does not make any specific predictions since it itself is unspecific. But hypothesis 1 makes further testable predictions. As we noted earlier, it was observed that memory capacity develops as children get older. We tested slightly older children (6–8-year-olds) to compare whether a developmental pattern could be observed in experiment 3. We selected this age group because a previous study by Arosio et al. (2012) showed that comprehension of object relative clauses in this age group is modulated by working memory as measured by forward digit-span score. If a prediction of hypothesis 1 is correct, it corroborates hypothesis 1. But it remains possible that the reason adults produce more full passives is due to more than one of the explanations above.

5. Experiment 2

5.1. Participants, Materials, and Procedure

A total of 20 adults (10 female, 10 male) participated in this study. The participants were recruited at universities in Berlin, Germany, and personal connections of researchers and received 5 euro for participation. The procedure of the study was the same as that of Experiment 1. The items that were used for Experiment 2 were also identical to that of Experiment 1, except for the order of presentation, which was changed in the following way.

In the second experiment, we presented two types of conditions in two separate blocks. In the first block, all the short passive stories/contexts (along with half of the items that elicited subject relatives) were presented. Afterwards, all the full passive contexts and the other half of the subject relative eliciting stories were given. This ordering was chosen so that the production of a full passive toward the beginning of the experiment would not prime the speaker to use only the full passives for the rest of the experiment. The contexts/stories used in this experiment were identical to the ones used in the Experiment 1.

As in Experiment 1, the whole experiment was recorded on a digital audio recorder. After the experimental session was finished, the produced responses, which were written down during the sessions, were entered on a spreadsheet. A native speaker then listened to the audio recordings to check for discrepancies.

After checking the recorded and handwritten data, we went through the data and labeled whether the produced form was (i) a target relative clause (active, with a gap in the expected slot in the sentence); (ii) short passive; (iii) full passive; (iv) other types of errors, such as theta-role reversal, in which the theta-role of the gap and the relative clause-internal argument were reversed, among others.

5.2. Results

There were 400 responses all together (200 items eliciting subject relatives, and 200 items eliciting object relatives). Overall, the adult participants of Experiment 2 produced the target subject relative clause 195 times out of the 200 responses and the target object relative clause 32 times of the 200 responses.

Among the nontarget responses for the items that elicited object relatives, 145 had the grammatical passive form. There were 127 tokens of full passives and 18 tokens of short passives produced. The distribution of these passives is shown in Table 4.

Table 4.

Adults, counts of full and short passives in Experiment 2.

Experiment 2 was conducted to find out whether the adults produced a disproportionately large number of full passives because of the priming effect: once the full passive was elicited, the participants may be producing only the full passive for the subsequent items that elicited object relatives. Therefore, we presented only the short passive contexts in the first block and only the full passive contexts in the second block. This did not cause the results to be visibly different from each other, at least not in terms of the number of tokens produced for each context.

Fisher’s exact test shows that the results of Experiment 2 do not differ from those of Experiment 1 significantly (). This suggests that the difference between children’s production of a by-phrase, which resembles what we expect from adults more closely, on the one hand, and what adults actually do, on the other, is not because of priming: even without being preceded by items that should elicit full passives, adult speakers produce more full passives than short passives compared to children.

In summary, the comparison of results from the adult participants in Experiments 1 and 2 shows that adults are not affected by priming of full passives. This leaves the two other hypotheses we mentioned above in contention: memory capacity hypothesis and task effect hypothesis.

6. Experiment 3

We now set out to distinguish between memory capacity hypothesis and task effect hypothesis. Task effect hypothesis says that an independent property of the experimental paradigm causes the difference in behavior between children and adults. One such property may be that adults feel obliged to mention all the items mentioned in the story told by the experimenter, but other properties may be equally likely. Without having a specific factor in mind, we address this hypothesis by investigating the behavior of slightly older children than the 5-year-olds in Experiment 1. Since the working memory of 6- and 7-year-old children is greater than that of 5-year-olds, the memory capacity hypothesis predicts that the rate of full passives produced in violation of brevity might grow according to the age of the children, if it is the working memory limitation that controls the use of the by-phrase. In contrast, the hypothesis that another experimental factor, such as a hypothetical convention to mention all introduced entities, is at issue makes no specific prediction for 6- and 7-year-olds—their awareness and desire to conform to such a convention cannot be predicted by their age.

6.1. Participants

A total of 25 children (6–8; = 7 years 1 month) participated in the third experiment.14 Children were recruited at two daycare centers and one primary school in Berlin, Germany. All the testing for children was conducted in a quiet room at the day care center or school that they attended.

6.2. Materials and Procedure

The materials and procedure were the same as Experiment 1. There were 10 items that elicited subject relatives, and 10 items that elicited object relatives. Among the 10 items that elicited object relatives 5 were full passive contexts, and 5 were short passive contexts. The order of the items was randomized and was the same for all the participants.

As in Experiment 1, the whole experiment was recorded on a digital audio recorder. After the experimental session was finished, the produced responses, which were written down during the sessions, were entered on a spreadsheet. A native speaker then listened to the audio recordings to check for discrepancies.

After checking the recorded and handwritten data, we went through the data and labeled whether the produced form was (i) a target relative clause (active, with a gap in the expected slot in the sentence); (ii) short passive; (iii) full passive; (iv) other types of errors, such as theta-role reversal, in which the theta-role of the gap and the relative clause-internal argument were reversed, among others.

6.3. Results

There were 500 responses elicited. Among the items that elicited subject relatives (250 responses), participants produced 210 tokens (84%) of target subject relatives. Among the items that elicited object relatives, 40 tokens (16%) were target object relatives. As in Experiment 1, there were many nontarget responses, including theta-role reversal (53 tokens) and 59 passives.

Among the 25 children in this experiment, 15 children produced at least one passive structure among the contexts that elicited object relatives. As before, overall, there were more full passives produced (46 tokens) among children than short passives (13 tokens). Recall, however that among the 5-year-old children, there were more short passives produced in the short passive contexts than full passives. Among this slightly older group, however, an approximately equal number of tokens was produced for both types of passives. The distribution of the use of each type of passive structures is shown in Table 5.

Table 5.

Children’s (6–8 years old) use of passives in the two contexts.

Although Fisher’s exact test shows that 6- and 7-year-old children’s use of full and short passives in two contexts differ (p < 0.01), this is not surprising, given that both 5-year-old children’s and adults’ responses showed a similar pattern. What we predict is that if some type of grammatical or cognitive development helps a participant to produce full passives in the relative clause, we should see that 6- and 7-year-old children’s production resembles that of adults’, more than 5-year-old children’s production did. To verify this, we compared the ratio of the production of full and short passives in the short passive contexts between 5-year-olds and 6- and 7-year-olds, on the one hand, and between 6- and 7-year-olds and adults, on the other.

We used Fisher’s exact test to compare the ratios among the three groups. Neither the comparison between 5-year-olds and 6- and 7-year-olds nor that between 6- and 7-year-olds and adults resulted in statistical significance (p = 0.3416 and p = 0.2776, respectively.) The results of these comparisons suggest that 6- and 7-year-olds are more likely to use full passives even in the short passive contexts than 5-year-olds, although the ratio does not yet significantly differ from that of 5-year-olds.

The results of Experiment 3 support a prediction made by the explanation of Experiment 1 based on memory capacity, although more work should be done to support this explanation fully. Although the result does not exclude the possibility of the specific experimental task used in this series of experiments actually being responsible for the difference between children and adults that we observed in Experiment 1, it restricts this possibility to other factors that change between the age of 5 and that of 6 or 7 years.

7. Discussion

Our study investigated the use of by-phrases in passive relative clauses when participants were prompted to produce object relative clauses. As in previous studies in other languages, both adults and children frequently produced passive sentences rather than the target object relative clauses.

Our main empirical finding is that adults produce by-phrases at a significantly higher rate than children in environments where it is pragmatically odd.15 Specifically, these were cases in which the agent of the passivized verb was known and therefore expressing the agency by means of a by-phrase was redundant. The maxim of brevity predicts that both children and adults uniformly should not express the agent in these cases, but we found empirically that the predicted effect of brevity was significantly stronger in children than in adults. Our Experiment 1 shows, therefore, that children are more pragmatic than adults with respect to brevity. Our findings contrast with those of several researchers concerning the maxim of quantity (Barner et al. 2011; Gualmini et al. 2001; Noveck 2001; Guasti et al. 2005; Huang and Snedeker 2009; Katsos and Bishop 2011; Papafragou and Musolino 2003, and others). For quantity, previous studies have found that children exhibit less pragmatic behavior than adults in experiments on the comprehension of underinformative sentences.

Our finding from Experiment 1 raises the question of why adults seem to frequently violate brevity whereas children do not. We raised three possible explanations at the end of Section 2: first, we suggest that adults might have working memory capacity, and therefore brevity is less important for adults than for children. We also considered two alternative hypotheses. One alternative explanation would be that adults are more sensitive to a priming effect. In Experiment 1, priming could occur because the order of the items was pseudo-randomized, blind to the two conditions (the short passive and the full passive contexts). It could be, therefore that adults tended to keep producing full passives after producing the first full passive. Finally, it could be that a task-specific effect triggered the use of a by-phrase by adults. For example, it could be that adults seek to display their language competence by producing full passives with a by-phrase. We eliminated both alternative hypotheses in Experiments 2 and 3. In Experiment 2, we tested adults with a design that was modified to eliminate the possibility of priming and found that adults still produced a high number of full passives. Given that the priming hypothesis would have predicted that in Experiment 2 the number of full passives should have been lower than in the experiment, our finding argues against Hypothesis 2. Hypothesis 3 is more difficult to address, and we focused on task-specific effects that would be specific to adults. Therefore, we tested children who were slightly older than those tested in Experiment 1—namely, 7-year-olds rather than the 5-year-olds in Experiment 1. If adult behavior was caused by a task-specific effect that applies only to adults, Hypothesis 3 would predict that 7-year-olds should also differ significantly from adults, just like the 5-year-olds in Experiment 1 did. Our empirical finding, however, shows no significant difference between 7-year-olds and adults. Rather, 7-year-olds exhibit a rate of full passives in between that of the younger children and that of adults. Our finding from Experiment 3 would not be predicted if the significant effect in Experiment 1 was due to task-specific effects that apply only to adults.

The results of all three experiments are predicted by our main hypothesis that children’s more limited cognitive resources make brevity more important for them.16 The comprehension of full passive sentences has been found to be more difficult than that of short passives in 5-year-old children (Armon-Lotem et al. 2016). Therefore, it is plausible that the production of a full passive is cognitively more demanding for children than the production of a short passive. At the same time, working memory resources have been found to correlate with relative clause understanding in children (Arosio et al. 2012). We propose, therefore, that children’s limited working memory resources cause them to value the maxim of brevity more highly than adults do. Furthermore, we propose that at the same time there is another factor that acts in the opposite direction of brevity, which we call full passive (FP) preference. The specific nature of FP preference we leave up to future research, given that our studies were not designed to do so. For example, FP preference may be the result of a preference to mention all entities that were mentioned in the question in an answer to that question, or it may be a general preference to name the agent even in passives where grammar does not require it. FP preference, we assume, applies uniformly to both adults and children and causes them to prefer the production of a full passive over a short passive even in trials in which the full passive violates brevity.17 However, the relative weight that children and adults assign to brevity and FP preference differs as the strength of brevity depends on an individual’s working memory resources.18 For adults, brevity is weak and therefore FP preference causes them to produce full passives frequently, even in violation of brevity. For 5-year-old children, however, brevity is stronger because of their smaller working memory, and therefore brevity almost always leads to a violation of FP preference. The different strength of brevity, therefore, explains the significant difference between adults and 5-year-olds that we report in Experiment 1. Also, the finding from Experiments 2 and 3 is predicted. Specifically, a 7-year-old’s working memory capacity lies between that of a 5-year-old’s and an adult’s (Gathercole et al. 2004), and therefore the strength of brevity for 7-year-olds is predicted to also lie between that of 5-year-olds and adults.

In conclusion, we have shown that 5-year-old children’s and adults’ sensitivity to brevity differs significantly in data from the production of passive sentences. Children only produce the FP form when it is necessary to express the agent, whereas adults frequently produce FP forms even when the agent of the action is already known. This finding can be summarized as follows: children behave more pragmatically than adults with respect to the maxim of brevity. Our finding seems to conflict with previous findings suggesting that children are less sensitive to pragmatic principles that adults (Barner et al. 2011; Gualmini et al. 2001; Guasti et al. 2005; Huang and Snedeker 2009; Katsos and Bishop 2011; Noveck 2001; Papafragou and Musolino 2003, and others). However these previous studies focused exclusively on the maxim of Quantity-1. We suggest that the seemingly conflicting findings from quantity-1 and brevity are in fact consistent: Both can be explained by children’s limited cognitive resources, in particular working memory. Quantity tasks have been shown to demand cognitive resources (De Neys and Schaeken 2007), and this can explain children’s difficulty with such tasks. However, we propose that obeying brevity saves cognitive resources and, therefore, that brevity is a stronger preference for individuals with more limited cognitive resources—specifically 5-year-old children. This explains why children are more logical than adults when it comes to quantity but more pragmatic when it comes to brevity.

Author Contributions

K.Y. and U.S. conceived and designed the experiments, K.Y. supervised the experiments being carried out and analyzed the data, and K.Y. and U.S. wrote the paper.

Funding

This work benefitted from financial support from the Federal Ministry for Education and Research (BMBF) grant 01UG1411 and the German Research Council (DFG), grants SA 925/11-1 and SA 925/11-2.

Acknowledgments

We thank Maria Teresa Guasti, Napoleon Katsos and Marie Christine Meyer for their helpful comments, and Elizabeth Laurencot for her editorial help.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest. The funding sponsors had no role in the design of the study; in the collection, analyses, or interpretation of data; in the writing of the manuscript, and in the decision to publish the results.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| ACC | accusative case |

| FEM | feminine gender |

| GEN | genitive case |

| FP | full passive (see (4)) |

| MASC | masculine gender |

| MEUT | neuter gender |

| NOM | nominative case |

| PART | participle |

| SG | singular number |

| SP | short passive (see (4)) |

Appendix A. Experimental Items

Appendix A.1. Subject Relative-Eliciting Stories

Reversible:

| (16) | a. | Ein Mädchen ärgert einen Freund und ein |

| a.neut.sg.nom girl anger.3sg a.masc.sg.acc friend and a.neut.sg.nom | ||

| Mädchen malt einen Freund | ||

| girl draw.3sg a.masc.sg.acc friend | ||

| “One girl angers a friend and one girl draws a friend.” | ||

| b. | Ein Mädchen trifft einen Erzieher und ein | |

| a.neut.sg.nom girl meet.3sg a.masc.sg.acc caretaker and a.neut.sg.nom | ||

| Mädchen trifft einen Freund. | ||

| girl meet.3sg a.masc.sg.acc friend | ||

| “One girl meets one day care teacher, and one girl meets one friend.” | ||

| c. | Ein Mädchen malt einen Polizisten und ein | |

| a.neut.sg.nom girl draw.3sg a.masc.sg.acc police and a.neut.sg.nom | ||

| Mädchen malt einen Tänzer. | ||

| girl draw.3sg a.masc.sg.acc dancer | ||

| “One girl draws a police, and a girl draws a dancer.” | ||

| d. | Ein Mädchen besucht seinen Onkel und ein | |

| a.neut.sg.nom girl visit.3sg it.neut.sg.gen uncle and a.neut.sg.nom | ||

| Mädchen lädt seinen Onkel ein. | ||

| girl invite.3sg it.neut.sg.acc uncle in | ||

| “One girl visits her uncle, and one girl invites her uncle.” | ||

| e. | Ein Mädchen filmt einen Mann und ein | |

| a.neut.sg.nom film.3sg a.masc.sg.acc man and a.neut.sg.nom film.3sg | ||

| Mädchen filmt einen Jungen. | ||

| a.masc.sg.acc boy | ||

| “One girl films one man and one girl films one boy.” | ||

| f. | Ein Mädchen umarmt seinen Vater und ein | |

| a.neut.sg.nom hug.3sg it.neut.sg.gen father and a.masc.sg.nom girl | ||

| Mädchen malt seinen Vater. | ||

| draw.3sgit.neut.sg.gen father | ||

| “A girl hugs her father and a girl draws her father.” | ||

| g. | Ein Mädchen isst Eiscreme und ein Mädchen isst | |

| a.neut.sg.nom girl eat.3sg ice cream and a.neut.sg.nom eat.3sg | ||

| Schokolade. | ||

| chocolate | ||

| “One girl eats ice cream and one girl eats chocolate.” |

Irreversible:

| (17) | a. | Ein Mädchen trinkt Milch und ein Mädchen trinkt |

| a.neut.sg.nom girl drink.3sg milk and a.sg.Neu.nom girl drink.3sg | ||

| Wasser. | ||

| water | ||

| “One girl drinks milk and one girl drinks water” | ||

| b. | Ein Mädchen bekommt einen Ring und ein | |

| a.neut.sg.nom girl receive.3sg a.masc.sg.acc ring and a.neut.sg.nom | ||

| Mädchen verschenkt einen Ring. | ||

| girl give.3sg a.masc.sg.acc right | ||

| “One girl receives a ring and one girl gives a present.” | ||

| c. | Ein Mädchen findet einen Ball und ein Mädchen | |

| a.neut.sg.nom girl find.3sg a.masc.sg.nom ball and a.neut.sg.nom girl | ||

| kauft einen Ball. | ||

| buy.3sg a.masc.sg.acc ball | ||

| “One girl finds a ball and one girl buys a ball.” |

Appendix A.2. Object Relative-Eliciting Stories

Reversible:

| (18) | a. | Sein Vater umarmt ein Mädchen und sein Vater |

| it.neut.sg.gen father hug.3sg a.neut.sg.acc girl and it.neut.sg.gen father | ||

| küsst ein Mädchen. | ||

| kiss.3sg a.sg.neut.acc girl | ||

| “Her father hugs one girl and her father kisses one girl.” | ||

| b. | Der Erzieher photographiert ein Mädchen und | |

| the.masc.sg.nom caretaker photograph.3sg a.neut.sg.acc girl and | ||

| der Opa photographiert ein Mädchen. | ||

| the.masc.sg.nom grandpa photograph.3sg a.neut.sg.acc girl | ||

| “The day care teacher photographs one girl and the grandpa photographs one girl.” | ||

| c. | Sein Opa sucht ein Mädchen und sein | |

| it.neut.sg.nom grandpa search.3sg a.neut.sg.acc girl and it.neut.sg.nom | ||

| Opa findet ein Mädchen. | ||

| grandpa find.3sg a.neut.sg.acc girl | ||

| “Her grandpa searches one girl, and her grandpa finds one girl.” | ||

| d. | Der Freund umarmt ein Mädchen und der | |

| the.masc.sg.nom friend hug.3sg a.neut.sg.acc girl and the.masc.sg.nom | ||

| Vater umarmt ein Mädchen. | ||

| father hug.3sg a.neut.sg.acc girl | ||

| “The friend hugs one girl and the father hugs one girl.” | ||

| e. | Sein Onkel fotografiert ein Mädchen und sein Onkel malt ein | |

| it.neut.sg.gen uncle photograph.3sg a.masc.sg.nom girl and it.neut.sg.gen | ||

| Onkel malt ein Mädchen. | ||

| uncle draw.3sg a.masc.sg.nom girl | ||

| “Her uncle photographs one girl, and her uncle draws one girl.” | ||

| f. | Der Nachbar kämmt ein Mädchen und | |

| the.masc.sg.nom neighbor comb.3sg a.masc.sg.nom and the.masc.sg.nom | ||

| der Onkel kämmt ein Mädchen. | ||

| uncle comb.3sg a.masc.sg.nom | ||

| “The neighbor combs one girl and the uncle combs one girl.” |

Irreversible:

| (19) | a. | Der Krach stört ein Mädchen und der |

| the.masc.sg.nom noise disturb.3sg a.neut.sg.acc girl and the.masc.sg.nom | ||

| Gestank stört ein Mädchen. | ||

| smell disturb.3sg a.neut.sg.acc | ||

| “The noise disturbs one girl and the small disturbs one girl.” | ||

| b. | Ein Film freut ein Mädchen und ein | |

| a.masc.sg.nom movie please.3sg a.neut.sg.acc girl and a.masc.sg.nom | ||

| Film erschreckt ein Mädchen. | ||

| movie scare.3sg a.neut.sg.acc girl | ||

| “One movie pleases one girl and one movie scares one girl.” | ||

| c. | Ein Elefant besprüht ein Mädchen und ein | |

| a.masc.sg.nom elephant spray.3sg a.masc.sg.nom girl and a.masc.sg.nom | ||

| Elefant trägt ein Mädchen. | ||

| elephant carry.3sg a.masc.sg.nom | ||

| “One elephant sprays (water) one girl and one elephant carries one girl.” | ||

| d. | Der Arzt untersucht ein Mädchen und der | |

| the.masc.sg.nom doctor examine.3sg a.neut.sg.acc girl and the.masc.sg.nom | ||

| Vater untersucht ein Mädchen. | ||

| father examine.3sg a.neut.sg.acc girl | ||

| “The doctor examines one girl, and the father examines one girl.” |

References

- Adani, Flavia, Maja Stegenwallner-Schütz, Yair Haendler, and Andrea Zukowski. 2016. Elicited production of relative clauses in German: Evidence from typically developing children and children with specific language imprairment. First Language 36: 203–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Armon-Lotem, Sharon, Ewa Haman, Kristine Jensen de Lopez, Magdalena Smoczynska, Kazuko Yatsushiro, Marcin Szczerbinski, Angeliek van Hout, Ineta Dabasinskiene, Anna Gavarro, Erin Hobbs, and et al. 2016. A large-scale crosslinguistic investigation of the acquisition of passive. Language Acquisition 23: 27–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arosio, Fabrizio, Flavia Adani, and Maria Teresa Guasti. 2005. Processing grammatical features by Italian children. Paper present at the A Supplement to the 30th Boston University Conference on Language Development, Boston, MA, USA; Edited by Bamman David, Tatiana Magnitskaia and Colleen Zaller. pp. 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arosio, Fabrizio, Kazuko Yatsushiro, Matteo Forgiarini, and Maria Teresa Guasti. 2012. Morphological information and memory resources in the acquisition of German relative clauses. Language Learning and Development 3: 340–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Avrutin, Sergey. 2000. Comprehension of discourse-linked and non-discourse-linked questions by children and Broca’s aphasics. In Language and the Brain: Representation and Processing. Edited by Grodzinsky Yosef, Lewis P. Shapiro and David Swinney. San Diego: Academic Press, pp. 295–313. [Google Scholar]

- Bader, Markus, and Michael Meng. 1999. Subject-object ambiguities in German embedded clauses: An across-the board comparison. Journal of Psycholinguistic Research 28: 121–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barner, David, Neon Brooks, and Alan Bale. 2011. Accessing the unsaid: The role of scalar alternatives in children’s pragmatic inference. Cognition 118: 87–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Belletti, Adriana. 2014. Notes on passive object relatives. In Functional Structure from Top to Toe: The Cartography of Syntactic Structures. Oxford: Oxford University Press, vol. 9, pp. 97–114. [Google Scholar]

- Booth, James R., Brian Whinney, and Ysuaki Harasaki. 2000. Developmental differences in visual and auditory processing of complex sentences. Child Development 71: 981–1003. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bott, Lewis, Todd M. Bailey, and Daniel Grodner. 2012. Distinguishing speed from accuracy in scalar implicatures. Journal of Memory and Language 66: 123–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bott, Lewis, and Ira A. Noveck. 2004. Some utterances are underinformative: The onset and time course of scalar inferences. Journal of Memory and Language 51: 437–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chemla, Emmanuel, and Raj Singh. 2014. Remarks on the experimental turn in the study of scalar implicature, part i. Language and Linguistics Compass 8: 373–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chevallier, Coralie, Ira A. Noveck, Tatjana Nazir, Lewis Bott, Valentina Lanzetti, and Dan Sperber. 2008. Making disjunctions exclusive. Quarterly Journal of Experimental Psychology 61: 1741–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clark, Eve V., and Chigusa Kurumada. 2013. Be brief: From necessity to choice. In Brevity. Edited by Goldstein Laurence. Oxford: Oxford University Press, pp. 233–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crain, Stephen, Rosalind Thornton, and Keiko Murasugi. 2009. Capturing the evasive passive. Language Acquisition 16: 123–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crawford, Jean. 2012. Developmental Perspectives on the Acquisition of the Passive. Ph.D. thesis, University of Connecticut, Storrs, CT, USA. [Google Scholar]

- Davies, Catherine, and Napoleon Katsos. 2010. Over-informative children: Production/comprehension asymmetry or tolerance to pragmatic violations? Lingua 120: 1956–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davies, Catherine, and Napoleon Katsos. 2013. Are speakers and listeners ‘only moderately Gricean’? an empirical response to Engelhardt et al. (2006). Journal of Pragmatics 49: 78–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Neys, Wim, and Walter Schaeken. 2007. When people are more logical under cognitive load. Experimental Psychology (formerly Zeitschrift für Experimentelle Psychologie) 54: 128–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Villiers, Jill, Helen Tager-Flusberg, Kenji Hakuta, and Michael Cohen. 1979. Children’s comprehension of relative clauses. Journal of Psycholinguistic Research 8: 499–518. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Engelhardt, Paul E., Karl G. D. Bailey, and Fernanda Ferreira. 2006. Do speakers and listeners observe the Gricean maxim of quantity? Journal of Memory and Language 54: 554–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fox, Danny, and Yosef Grodzinsky. 1998. Children’s passive: A view from the by-phrase. Linguistic Inquiry 28: 311–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frazier, Lyn. 1987. Syntactic processing: Evidence from Dutch. Natural Language and Linguistic Theory 5: 519–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Friederici, Angela, Karsten Steinhauer, Axel Mecklinger, and Martin Meyer. 1998. Working memory ä on syntactic ambiguity resolution as revealed by electrical brain responses. Biological Psychology 47: 193–221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Friedmann, Naama, Adriana Belletti, and Luigi Rizzi. 2009. Relativized relatives: Types of intervention in the acquisition of A-bar dependencies. Lingua 119: 67–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gathercole, Susan E., Susan J. Pickering, Benjamin Ambridge, and Hannah Wearing. 2004. The structure of working memory from 4 to 15 years of age. Developmental Psychology 40: 177–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goldstein, Laurence, ed. 2013. Brevity. Oxford: Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gordon, Peter, and Jill Chafetz. 1990. Verb-based versus class-based accounts of actionality effects in children’s comprehension of passives. Cognition 36: 227–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grice, H. Paul. 1975. Logic and conversation. In Speech Acts. Syntax and Semantics. Edited by Cole Peter and Jerry L. Morgan. New York: Academic Press, vol. 3, pp. 41–58. [Google Scholar]

- Grice, H. Paul. 1989. Studies in the Way of Words. Cambridge: Harvard University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Grillo, Nino. 2008. Generalized Minimality: Syntactic Underspercification in Broca’s Aphasia. Ph.D. thesis, University Utrecht, Utrecht, The Netherlands. [Google Scholar]

- Grillo, Nino. 2009. Generalized minimality: Feature impoverishment and comprehension deficits in agrammatism. Lingua 119: 1426–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gualmini, Andrea, Stephen Crain, Luisa Meroni, Gennaro Chierchia, and Maria Teresa Guasti. 2001. At the semantics/pragmatics interface in child language. In Proceedings of SALT 11. Ithaca: CLC-Publications, Cornell University, pp. 231–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guasti, Maria Teresa, Chiara Branchini, and Fabrizio Arosio. 2012. Interference in the production of Italian subject and object wh-questions. Applied Psycholinguistics 33: 185–223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guasti, Maria Teresa, Gennaro Chierchia, Stephen Crain, Francesca Foppolo, Andrea Gualmini, and Luisa Meroni. 2005. Why children and adults sometimes (but not always) compute implicatures. Language and Cognitive Processes 20: 667–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haider, Hubert. 2010. The Syntax of German. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Horn, Laurence R. 1984. Toward a new taxonomy for pragmatic inference: Q-based and R-based implicature. In Meaning, Form, and Use in Context: Linguistic Applications. Edited by D. Schiffrin. Washington, DC: Georgetown University Press, pp. 11–42. [Google Scholar]

- Huang, Yi Ting, and Jesse Snedeker. 2009. Semantic meaning and pragmatic interpretation in 5-year-olds: Evidence from real-time spoken language comprehension. Developmental Psychology 45: 1723–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hulsey, Sarah, and Uli Sauerland. 2006. Sorting out relative clauses. Natural Language Semantics 10: 111–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Just, Marcel A., and Patricia A. Carpenter. 1992. A capacity theory of comprehension: Individual differences in working memory. Psychological Review 99: 122–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Katsos, Napoleon, and Dorothy V. M. Bishop. 2011. Pragmatic tolerance: Implications for the acquisition of informativeness and implicature. Cognition 120: 67–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Katsos, Napoleon, Chris Cummins, Maria-José Ezeizabarrena, Anna Gavarró, Jelena Kuvač Kraljević, Gordana Hrzica, Kleanthes K. Grohmann, Athina Skordi, Kristine Jensen de López, Lone Sundahl, and et al. 2016. Cross-linguistic patterns in the acquisition of quantifiers. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 113: 9244–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krifka, Manfred. 2009. Approximate interpretations of number words: A case for strategic communication. In Theory and Evidence in Semantics. Edited by Hinrichs Erhard and John A. Nerbonne. Stanford: CSLI Publications, pp. 109–32. [Google Scholar]

- Labelle, Marie. 1990. Predication, wh-movement, and the development of relative clauses. Language Acquisition 1: 95–119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marty, Paul P. 2017. Implicatures in the DP Domain. Ph.D. thesis, Massachusetts Institute of Technology, Cambridge, MA, USA. [Google Scholar]

- Meyer, Marie-Christine. 2013. Ignorance and Grammar. Ph.D. thesis, Massachusetts Institute of Technology, Cambridge, MA, USA. [Google Scholar]

- Meyer, Marie-Christine. 2015. Redundancy and embedded exhaustification. Proceedings of SALT, 491–511. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Noveck, Ira. 2001. When children are more logical than adults: Experimental investigations of scalar implicature. Cognition 78: 165–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Noveck, Ira A., and Anne Reboul. 2008. Experimental pragmatics: A Gricean turn in the study of language. Trends in Cognitive Sciences 12: 425–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Novogrodsky, Rama, and Naama Friedmann. 2006. The production of relative clauses in syntactic SLI: A window to the nature of the impairment. Advances in Speech Language Pathology 8: 364–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Papafragou, Anna, and Julien Musolino. 2003. Scalar implicatures: Experiments at the semantics-pragmatics interface. Cognition 86: 253–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Papafragou, Anna, and Niki Tantalou. 2004. Children’s computation of implicatures. Language Acquisition 12: 71–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pinker, Steven, David Lebeaux, and Loren Frost. 1987. Productivity and ä in the acquisition of the passive. Cognition 26: 195–267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sauerland, Uli. 2018. The thought uniqueness hypothesis. Proceedings of SALT 28: 289–306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sauerland, Uli, and Nicole Gotzner. 2013. Familial sinistrals avoid exact numbers. PLoS ONE 8: e59103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sauerland, Uli, Kleanthes K. Grohmann, Maria Teresa Guasti, Darinka Anđelković, Reili Argus, Sharon Armon-Lotem, Fabrizio Arosio, Larisa Avram, João Costa, Ineta Dabašinskienė, Kristina de López, and et al. 2016. How do 5-year-olds understand questions? Differences in languages across Europe. First Language 36: 169–202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sauerland, Uli, and Petra Schumacher. 2016. Pragmatics: Theory and experiment growing together. Linguistische Berichte 245: 3–24. [Google Scholar]

- Schriefers, Hubert, Angela D. Friederici, and Katja Kühn. 1995. The processing of locally ambiguous relative clauses in German. Journal of Memory and Language 8: 499–520. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seidl, Amanda, George Hollich, and Peter W. Jusczyk. 2003. Early understanding of subject and object wh-questions. Infancy 4: 423–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Solt, Stephanie. 2015. Vagueness and imprecision: Empirical foundations. Annual Review of Linguistics 1: 107–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sperber, Dan, and Deirdre Wilson. 1986. Relevance: Communication and Cognition. Cambridge: Harvard University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Turner, Elizabeth A., and Ragnar Rommetveit. 1967. The acquisition of sentence voice and reversibility. Child Development 38: 649–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]