Teasing Apart the Effects of Dominance, Transfer, and Processing in Reference Production by German–Italian Bilingual Adolescents

Abstract

1. Introduction

1.1. Bilingual Reference Production at the Crossroad of Transfer, Processing and Dominance: A Review of Previous Studies

| 1. | Lo | vuole | (* Vuole lo) | |

| CL.ACC.MASC.SG | want.3SG.PRES | |||

| ‘He wants it.’ | ||||

| 2. | (di) | voler-lo | (* Lo volere) | |

| to | want.INF.-CL.ACC.MASC.SG | |||

| ‘To want it.’ | ||||

| 3. | Lo | vuole | prendere | |

| CL.ACC.MASC.SG | want.3SG.PRES | take.INF | ||

| ‘He wants to take it.’ | ||||

| 4. | Vuole | prender-lo | ||

| want.3SG.PRES | take.INF.-CL.ACC.MASC.SG | |||

| ‘He wants to take it.’ | ||||

2. Methods and Materials

2.1. Participants

2.2. Assessing the Bilingual Index Score

2.3. Materials

2.4. Procedure

2.5. Analysis of the Narratives

2.5.1. Identifying Overspecified Referring Expressions

| 5. | a. | U1 | (F5: 12;5) | |||

| E il gioco | è | nell’acqua | ||||

| and the toy | be.3SG.PRES | in the water | ||||

| ‘And the toy is in the water.’ | ||||||

| b. | U2 | |||||

| E il grosso elefante | prende | il gioco | ||||

| and the big elephant | take.3SG.PRES | the toy | ||||

| ‘And the big elephant takes the toy.’ | ||||||

2.5.2. Analysis of Clitics

2.5.3. Syntactic Complexity and Word Orders in Main Clauses

3. Results

3.1. Production of Clitics

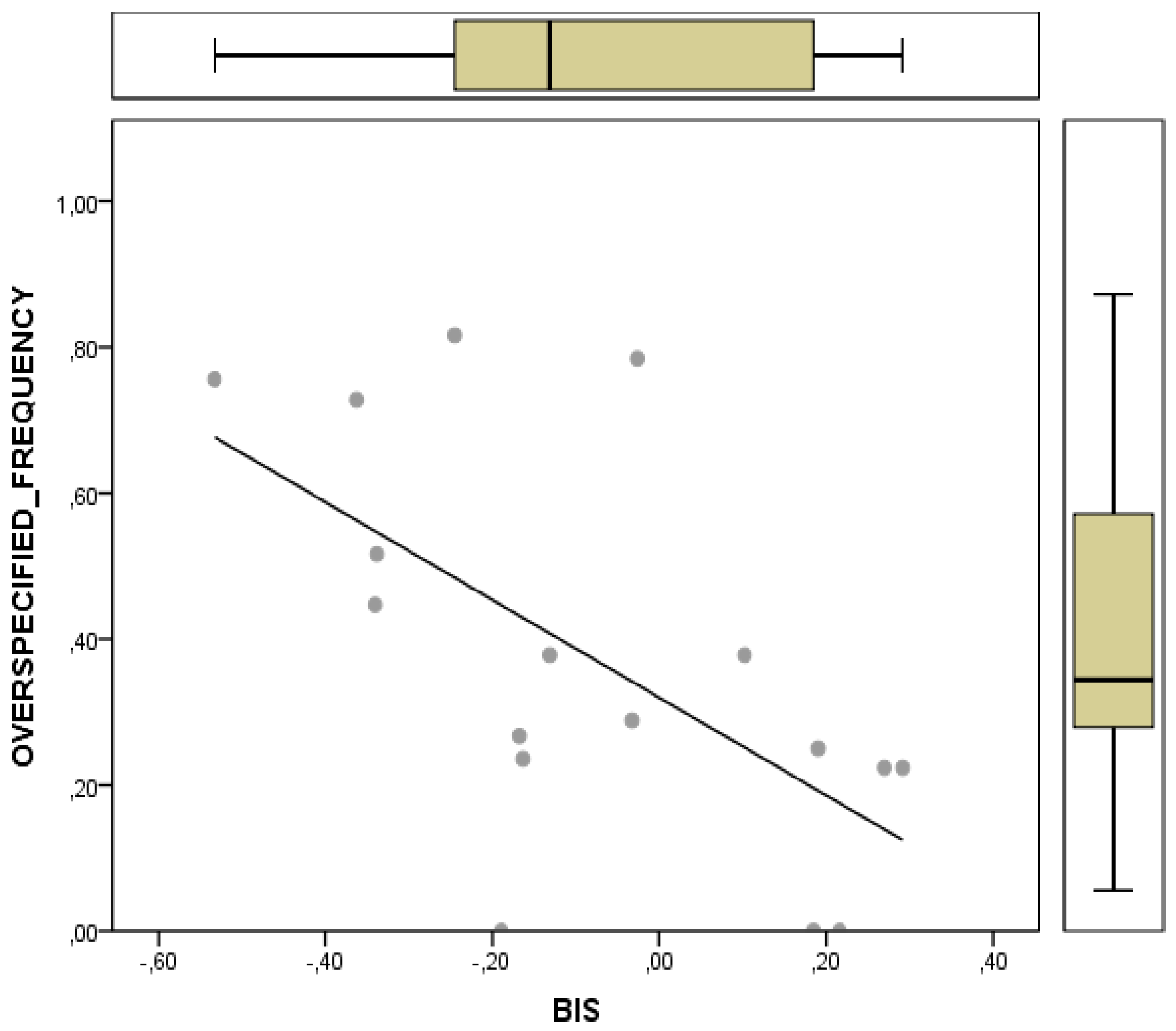

3.2. Production of Overspecified Forms

3.3. Omission of Clitics

3.4. Agreement Mismatches

3.5. Word Orders and Constituent-Verb-Subject-(Object) Structures

4. Discussion

| 6. | Poi | so’ | andati | quelli | |

| Then | AUX.3PP.PRES | gone | those | ||

| ‘Then those have gone.’ | |||||

| 7. | Poi | chiede | la femmina | alla giraffa | |

| Then | ask.3.SG.PRES | the girl | to the giraffe | ||

| ‘Then the girl asks the giraffe.’ | |||||

Author Contributions

Funding

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Aboh, Enoch. 2015. The Emergence of Hybrid Grammars. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Almor, Amit. 1999. Noun-phrase anaphora and focus: The informational load hypothesis. Psychological Review 106: 748–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ariel, Mira. 1990. Accessing Noun-Phrase Antecedents. London: Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Arnold, Jennifer. 2010. How speakers refer: The role of accessibility. Language and Linguistic Compass 4: 187–203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arnold, Jennifer E., and Zenzi M. Griffin. 2007. The effect of additional characters on choice of referring expression: Everyone counts. Journal of Memory and Language 56: 521–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Arnold, Jennifer E., Janet G. Eisenband, Sarah Brown-Schmidt, and John C. Trueswell. 2000. The rapid use of gender information: Evidence of the time course of pronoun resolution from eye tracking. Cognition 76: B13–B26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Balaban, Noga, Adriana Belletti, Naama Friedmann, and Luigi Rizzi. 2016. Disentangling Principle C: A contribution from individuals with brain damage. Lingua 169: 1–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Belletti, Adriana. 1999. Italian/Romance clitics: Structure and derivation. In Clitics in the Languages of Europe, Empirical Approaches to Language Typology. Edited by Henk van Riemsdijk. Berlin and New York: Mouton de Gruyter, pp. 543–79. [Google Scholar]

- Belletti, Adriana. 2004. Aspects of the low IP-area. In The structure of CP and IP. Edited by Luigi Rizzi. New York: Oxford University Press, pp. 16–51. [Google Scholar]

- Belletti, Adriana, and Maria Teresa Guasti. 2015. The Acquisition of Italian: Morphosyntax and Its Interfaces in Different Modes of Acquisition. Amsterdam: John Benjamins. [Google Scholar]

- Belletti, Adriana, Elisa Bennati, and Antonella Sorace. 2007. Theoretical and developmental issues in the syntax of subjects: Evidence from near-native Italian. Natural Language and Linguistic Theory 25: 657–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bennati, Elisa. 2007. Pronouns in Adult L2 Acquisition: Evidence from L2 Near-Native Italian. Ph.D. dissertation, University of Siena, Siena, Italy. [Google Scholar]

- Bernardini, Petra. 2003. Child and adult acquisition of word order in the Italian DP. In (In)vulnerable Domains in Multilingualism. Edited by Natascha Müller. Amsterdam: John Benjamins, pp. 41–81. [Google Scholar]

- Bialystok, Ellen, Fergus Craik, and Gigi Luk. 2008. Cognitive control and lexical access in younger and older bilinguals. Journal of Experimental Psychology: Learning, Memory and Cognition 34: 859–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bongartz, Christiane, and Jacopo Torregrossa. 2017. The effects of balanced biliteracy on Greek-German bilingual children’s secondary discourse ability. Journal of Bilingual Education and Bilingualism, 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burzio, Luigi. 1998. Anaphora and soft constraints. In Is the Best Good Enough? Optimality and Competition in Syntax. Edited by Pilar Barbosa, Daniel Fox, Paul Hagstrom, Martha McGinnis and David Pesetsky. Cambridge: MIT Press, pp. 93–114. [Google Scholar]

- Cardinaletti, Anna, and Michal Starke. 1999. The Typology of Structural Deficiency. A Case Study of the Three Classes of Pronouns. In Clitics in the Languages of Europe. Edited by Henk van Riemsdijk. Berlin: Mouton-De Gruyter, pp. 145–233. [Google Scholar]

- Carminati, Maria Nella. 2002. The Processing of Italian Subject Pronouns. Ph.D. dissertation, University of Massachusetts, Amherst, MA, USA. [Google Scholar]

- Cinque, Guglielmo. 2004. Restructuring and Functional Structure. In The Cartography of Syntactic Structure. Edited by Adriana Belletti. New York: Oxford University Press, vol. 3, pp. 132–91. [Google Scholar]

- Clahsen, Harald, and Claudia Felser. 2006. Grammatical processing in language learners. Applied Psycholinguistics 27: 3–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cook, Vivian, ed. 2003. Effects of the Second Language on the First. Second Language Acquisition Series; Clevedon: Multilingual Matters. [Google Scholar]

- De Houwer, Annick. 1990. The Acquisition of Two Languages from Birth: A Case Study. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Devlin, Megan, Raffaella Folli, Alison Henry, and Christina Sevdali. 2012. Clitic left dislocation in absence of clitics: A study in trilingual acquisition. University of Pennsylvania Working Papers in Linguistics 18: 41–50. [Google Scholar]

- Döpke, Susanne. 1998. Competing language structures: The acquisition of verb placement by bilingual German-English children. Journal of Child Language 25: 555–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Döpke, Susanne, ed. 2000. Cross-Linguistic Structures in Simultaneous Bilingualism. Amsterdam: John Benjamins. [Google Scholar]

- Ellis, Nick C. 2005. At the interface: Dynamic interactions of explicit and implicit language knowledge. Studies in Second Language Acquisition 27: 305–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fernández, Eva M., Ricardo Augusto De Souza, and Agustina Carando. 2017. Bilingual innovation: Experimental evidence offers clues regarding the psycholinguistics of language change. Bilingualism: Language and Cognition 20: 251–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fernández-Fuertes, Raquel, and Juana M. Liceras. 2018. Bilingualism as a first language: Language dominance and cross-linguistic influence. In Language Acquisition and Contact in the Iberian Peninsula. Edited by Alejandro Cuza and Pedro Guijarro-Fuentes. Berlin: De Gruyter Mouton. [Google Scholar]

- Francis, Norbert. 2011. Bilingual Competence and Bilingual Proficiency in Child Development. Cambridge: The MIT Press. [Google Scholar]

- Gollan, Tamar H., Rosa I. Montoya, Cynthia Cera, and Tiffany C. Sandoval. 2008. More use almost always means a smaller frequency effect: Aging, bilingualism and the weaker links hypothesis. Journal of Memory and Language 58: 787–814. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hendriks, Petra. 2014. Asymmetries between Language Production and Comprehension. Studies in Theoretical Psycholinguistics. Dordrecht: Springer, vol. 42. [Google Scholar]

- Hopp, Holger. 2013. The development of L2 morphology. Second Language Research 29: 3–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hsin, Lisa, Géraldine Legendre, and Akira Omaki. 2013. Priming cross-linguistic interference in Spanish-English bilingual children. In BUCLD 37: Proceedings of the 37th Annual Boston University Conference on Language Development. Edited by Sarah Baiz, Nora Goldman and Rachel Hawkes. Somerville: Cascadilla Press, pp. 165–77. [Google Scholar]

- Hulk, Aafke, and Natascha Müller. 2000. Bilingual first language acquisition at the interface between syntax and pragmatics. Bilingualism: Language and Cognition 3: 227–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaplan, Edith, Harold Goodglass, and Sandra Weintraub. 1983. The Boston Naming Test. Philadelphia: Lea & Febiger. [Google Scholar]

- Kupisch, Tanja, and Jason Rothman. 2016. Terminology matters! Why difference is not incompleteness and how early child bilinguals are heritage speakers. International Journal of Bilingualism. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kupisch, Tanja, Tatjana Lein, Dagmar Barton, Dawn Judith Schröder, Ilse Stangen, and Antje Stoehr. 2014. Acquisition outcomes across domains in simultaneous bilinguals with French as weaker and stronger language. Journal of French Language Studies 24: 347–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Langacker, Ronald W. 1990. Concept, Image, and Symbol: The Cognitive Basis of Grammar. Berlin: Mouton de Gruyter. [Google Scholar]

- Lanza, Elizabeth. 2000. Concluding remarks: Language contact—A dilemma for the bilingual child or for the linguist? In Cross-Linguistic Structures in Simultaneous Bilingualism. Edited by Susanne Döpke. Amsterdam: John Benjamins, pp. 227–46. [Google Scholar]

- Liceras, Juana M., and Raquel Fernández Fuertes. 2016. Subject omission/production in child bilingual English and child bilingual Spanish: The view from linguistic theory. Probus 29: 1–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liceras, Juana M., Raquel Fernández Fuertes, and Anahí Alba de la Fuente. 2012. Overt subjects and copula omission in the Spanish and the English grammar of English-Spanish bilinguals: On the locus and directionality of interlinguistic influence. First Language 32: 88–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liceras, Juana M., Raquel Fernández Fuertes, and Rachel Klassen. 2016. Language dominance and language nativeness: The view from English-Spanish code-switching. In Spanish-English Codeswitching in the Caribbean and the US. Edited by Rosa E. Guzzardo Tamargo, Catherine M. Mazak and María del Carmen Parafita Couto. Amsterdam: John Benjamins, pp. 107–38. [Google Scholar]

- Lozano, Cristóbal. 2016. Pragmatic principles in anaphora resolution at the syntax-discourse interface: Advanced English learners of Spanish in the CEDEL2 corpus. In Spanish Learner Corpus Research: Current Trends and Future Perspectives. Edited by Margarita Alonso-Ramos. Amsterdam: John Benjamins, pp. 236–65. [Google Scholar]

- MacWhinney, Brian. 2000. The CHILDES Project: Tools for Analyzing Talk, 3rd ed. Mahwah: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates. [Google Scholar]

- Mateu, Victoria Eugenia. 2015. Object clitic omission in child Spanish: Evaluating representational and processing accounts. Language Acquisition 22: 240–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mattheoudakis, Marina, Aspasia Chatzidaki, Christina Maligkoudi, and Eleni Agathopoulou. 2016. Family and school language input: Their role in bilingual children’s vocabulary development. Journal of Applied Linguistics. [Google Scholar]

- Meisel, Jürgen M. 2011. Bilingual language acquisition and theories of diachronic change: Bilingualism as cause and effect of grammatical change. Bilingualism: Language and Cognition 14: 121–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meisel, Jürgen M., Martin Elsig, and Esther Rinke. 2013. Language Acquisition and Change: A Morphosyntactic Perspective. Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Merten, Thomas. 2004. Entwicklung einer deutschen Kurzform des Boston Naming Test. Neurologische Riabilitation 6: 305–11. [Google Scholar]

- Montrul, Silvina. 2010. How similar are L2 learners and heritage speakers? Spanish clitics and word order. Applied Psycholinguistics 31: 167–207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Montrul, Silvina. 2016. Dominance and proficiency in second language acquisition and bilingualism. In Measuring Dominance in Bilingualism. Edited by Carmen Silva-Corvalán and Jeanine Treffers-Daller. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, pp. 15–35. [Google Scholar]

- Müller, Natascha, and Aafke Hulk. 2001. Crosslinguistic influence in bilingual language acquisition: Italian and French as recipient languages. Bilingualism: Language and Cognition 4: 1–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Navarro, Müller, Fischer Susann, and Jorge Vega Vilanova. 2017. Reconstruyendo un ciclo: Doblado de clíticos y gramaticalización en las lenguas romances. In Investigaciones en Lingüística. vol. III: Sintaxis. Edited by Silvia Gumiel-Molina, Manuel Leonetti and Isabel Pérez-Jiménez. Alcalá de Henares: Publicaciones de la Universidad de Alcalá. [Google Scholar]

- Nicoladis, Elena. 2006. Cross-linguistic transfer in adjective-noun strings by preschool bilingual children. Bilingualism: Language and Cognition 9: 15–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Papadopoulou, Despina, Eleni Peristeri, Evagelia Plemenou, Theodoros Marinis, and Ianthi Maria Tsimpli. 2015. Pronoun ambiguity resolution in Greek: Evidence from monolingual adults and children. Lingua 155: 98–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paradis, Michel. 2009. Declarative and Procedural Determinants of Second Language. Amsterdam: John Benjamins. [Google Scholar]

- Petitto, Laura-Ann, and Ioulia Kovelman. 2003. The bilingual paradox: How signing-speaking bilingual children help us to resolve bilingual issues and teach us about the brain’s mechanisms underlying language acquisition. Learning Languages 8: 5–18. [Google Scholar]

- Pliatsikas, Christos, and Theodoros Marinis. 2013. Processing of regular and irregular past tense morphology in highly proficient second language learners of English: A self-paced reading study. Applied Psycholinguistics 34: 943–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prévost, Philippe, and Lydia White. 2000. Missing Surface Inflection or Impairment in second language acquisition? Evidence from tense and agreement. Second Language Research 16: 103–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Repetto, Valentina, and Natascha Müller. 2010. The acquisition of German V2 in bilingual Italian-German children residing in Germany and Italy: A case of acceleration? In Movement and Clitics: Adult and Child Grammar. Edited by Vicenç Torrens, Linda Escobar, Anna Gavarró and Juncal Gutiérrez. Newcastle upon Tyne: Cambridge Scholars Publishing, pp. 155–84. [Google Scholar]

- Rinke, Esther, and Cristina Flores. 2014. Morphosyntactic knowledge of clitics by Portuguese heritage bilinguals. Bilingualism: Language and Cognition 17: 681–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Riva, Daria, Francesca Nichelli, and Monica Devoti. 2000. Developmental aspects of verbal fluency and confrontation naming in children. Brain and Language 71: 267–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schmeißer, Anika, and Veronika Jansen. 2016. Finite verb placement in French language change and in bilingual German-French language acquisition. In The Acquisition of French in Its Different Constellations. Edited by Katrin Schmitz, Patuto Guijarro-Fuentes and Natascha Müller. Bristol: Multilingualism Matters. [Google Scholar]

- Schmitz, Katrin, Marisa Patuto, and Natascha Müller. 2012. The null-subject parameter at the interface between syntax and pragmatics: Evidence from bilingual German-Italian, German-French and Italian-French children. First Language 32: 205–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schneider, Phyllis, Rita V. Dubé, and Denyse Hayward. 2005. The Edmonton Narrative Norms Instrument. Available online: http://www.rehabresearch.ualberta.ca/enni (accessed on 25 May 2016).

- Serratrice, Ludovica. 2007. Referential cohesion in the narratives of bilingual English-Italian children and monolingual peers. Journal of Pragmatics 39: 1058–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Serratrice, Ludovica. 2013. Crosslinguistic influence in bilingual development: Determinants and mechanisms. Linguistic Approaches to Bilingualism 3: 3–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Serratrice, Ludovica, and Shanley E.M. Allen, eds. 2015. The Acquisition of Reference. Amsterdam: John Benjamins. [Google Scholar]

- Serratrice, Ludovica, Antonella Sorace, and Sandra Paoli. 2004. Crosslinguistic influence at the syntax-pragmatics interface: Subjects and objects in English-Italian bilingual and monolingual acquisition. Bilingualism: Language and Cognition 7: 183–205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silva-Corvalán, Carmen. 1994. Language Contact and Change. Oxford: Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Sorace, Antonella. 2004. Native language attrition and developmental instability at the syntax-discourse interface: Data, interpretations and methods. Bilingualism: Language and Cognition 7: 1–3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sorace, Antonella. 2011. Pinning down the concept of ‘interface’ in bilingualism. Linguistic Approaches to Bilingualism 1: 1–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sorace, Antonella, and Francesca Filiaci. 2006. Anaphora resolution in near-native speakers of Italian. Second Language Research 22: 339–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sorace, Antonella, and Ludovica Serratrice. 2009. Internal and external interfaces in bilingual language development: Beyond structural overlap. International Journal of Bilingualism 13: 195–210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Surrain, Sarah, and Gigi Luk. 2017. Describing bilinguals: A systematic review of labels and descriptions used in the literature between 2005–2015. Bilingualism: Language and Cognition, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thomason, Sarah Grey, and Terrence Kaufman. 1991. Language Contact, Creolization, and Genetic Linguistics. Berkeley: University of California Press. [Google Scholar]

- Torregrossa, Jacopo, and Christine Bongartz. In preparation. Bilingual narratives under cognitive load.

- Torregrossa, Jacopo, Christiane Bongartz, and Ianthi Maria Tsimpli. 2015. Testing accessibility: A cross-linguistic comparison of the syntax of referring expressions. Paper presented at the 89th Annual Meeting of the Linguistic Society of America, Portland, OR, USA, January 8–11. [Google Scholar]

- Torregrossa, Jacopo, Maria Andreou, Christian Bongartz, and Ianthi Maria Tsimpli. 2017. Pinning down the role of type of bilingualism in the development of referential strategies. Paper presented at the Generative Linguistics in the Old World (GLOW 40), Leiden, The Netherlands, March 15–17. [Google Scholar]

- Torregrossa, Jacopo, Christiane Bongartz, and Ianthi Maria Tsimpli. 2018. Bilingual reference production: A cognitive-computational account. Linguistic Approaches to Bilingualism, 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Treffers-Daller, Jeanine. 2013. Measuring lexical diversity among L2 learners of French: An exploration of the validity of D, MTLD and HD-D as measures of language ability. In Vocabulary Knowledge: Human Ratings and Automated Measures. Edited by Scott Jarvis and Michael Daller. Amsterdam: Benjamins, pp. 79–104. [Google Scholar]

- Treffers-Daller, Jeanine, and Vivienne Rogers. 2014. Grammatical Patterns and the L2 lexicon. In Dimensions of Vocabulary Knowledge. Edited by James Milton and Tess Fitzpatrick. London: Palgrave, pp. 106–22. [Google Scholar]

- Treffers-Daller, Jeanine, A. Sumru Özsoy, and Roeland Van Hout. 2007. (In)complete acquisition of Turkish among Turkish-German bilinguals in Germany and Turkey: An analysis of complex embeddings in narratives. International Journal of Bilingual Education and Bilingualism 10: 248–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsimpli, Ianthi Maria. 2014. Early, late or very late? Timing acquisition and bilingualism. Linguistic Approaches to Bilingualism 3: 283–313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsimpli, Ianthi Maria, and Antonella Sorace. 2006. Differentiating Interfaces: L2 performance in syntax-semantics and syntax-discourse phenomena. In BUCLD 30: Proceedings of the 30th annual Boston University Conference on Language Development. Edited by David Bamman, Tatiana Magnitskaia and Colleen Zaller. Somerville: Cascadilla Press, vol. 2, pp. 653–64. [Google Scholar]

- Tsimpli, Ianthi Maria, Antonella Sorace, Caroline Heycock, and Francesca Filiaci. 2004. First language attrition and syntactic subjects: A study of Greek and Italian near-native speakers of English. International Journal of Bilingualism 8: 257–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Unsworth, Sharon. 2013. Assessing the role of current and cumulative exposure in simultaneous bilingual acquisition: The case of Dutch gender. Bilingualism: Language and Cognition 16: 86–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vega Vilanova, Jorge, Mario Navarro, and Susann Fischer. 2018. The clitic doubling cycle. A diachronic reconstruction. In Comparative and Diachronic Perspectives on Romance Syntax. Edited by Gabriela Pană Dindelegan, Adina Dragomirescu, Irina Nicula and Alexandru Nicolae. Cambridge: Cambridge Scholars Publishing. [Google Scholar]

- Vernice, Mirta, and Maria Teresa Guasti. 2015. The acquisition of SV order in unaccusatives: Manipulating the definiteness of the NP. Journal of Child Language 42: 210–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yip, Virginia, and Stephen Matthews. 2000. Syntactic transfer in a Cantonese-English bilingual child. Bilingualism: Language and Cognition 3: 193–208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zdrojewski, Pablo, and Liliana Sánchez. 2014. Variation in accusative clitic doubling across three Spanish Dialects. Lingua 15: 162–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zuckerman, Shalom. 2001. The Acquisition of ‘Optional’ Movement. Ph.D. dissertation, University of Groningen, Groningen, The Netherlands. [Google Scholar]

| 1 | Recent studies—mainly based on code-mixing data—have formulated more clear-cut hypotheses on the relationship between language dominance and transfer, assuming a definition of dominance that is based on linguistic criteria. The dominant language is the one with the most salient (alias most grammaticized) morphosyntactic features (e.g., gender in Spanish vs. English)—see Fernández Fuertes and Liceras 2018 and Liceras et al. 2016. While this definition seems to account properly for young simultaneous bilinguals’ data, its predictive value for other types of bilinguals has not been assessed yet. Therefore, in this paper, we will consider dominance as a proxy for language experience and proficiency, which we believe is more relevant when analyzing language production by older bilingual children that have been exposed to a varying amount of input throughout the lifespan. | ||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 2 | The distinction between overt pronouns and clitics might appear not as motivated as the distinction between null and overt pronouns, given that clitics are overt too (in the sense of being realized phonologically). In the case of clitics, we consider “overt” as synonymous for “strong”, in compliance with the distinction between clitics and strong pronouns reported in Cardinaletti and Starke (1999). | ||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 3 | The morphosyntactic complexity account makes no prediction concerning the production of object pronouns in Italian by German-Italian children, as far as we understand the proposal. The two languages are equally complex, since both allow for two morphosyntactic exponents of object pronouns, i.e., clitics and overt pronouns in Italian, and nulls and overt pronouns in German. | ||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 4 | The studies of Sorace (2011) and Torregrossa et al. (2018) differ in the assumption of which forms count as default, i.e., overt pronouns for the former, nulls for the latter. The type of form used as default might be an effect of the type of bilingualism taken into account. The investigation of Torregrossa et al. (2018) considers only (relatively) balanced bilingual children. | ||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 5 | In Italian, OCC can occur only with certain verbs, i.e., modal (e.g., volere ‘to want’), aspectual (e.g., finire ‘to finish’) and motion verbs (e.g., andare ‘to go’). Cf. Cinque 2004. | ||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 6 | We refer to Bennati (2007), who shows that in the acquisition of these structures, L2-learners exhibit target like behavior only at near native levels. Moreover, several studies have shown that optional structures—like OCCs—are more difficult to acquire than ‘categorical’ ones (e.g., Zuckerman 2001). In this inventory of syntactic structures, causatives should also be mentioned (see (i)). As in the case of OCCs, causatives involve complex predicate formation (as in fa portare ‘(s/he) makes somebody bring something’ in (i)), but no optionality in the position of clitic, which has to precede the verb.

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 7 | The production of full DPs instead of clitic pronouns in Italian has already been observed among English‒Italian and German‒Italian bilingual children (Belletti and Guasti 2015, pp. 102–5 and reference quoted therein; Serratrice 2007). On the contrary, overt pronouns are rarely produced. The authors interpret the overproduction of full DPs as a strategy to avoid the use of object clitics, due to their complex morphosyntax. This analysis could be extended to the production of full DPs instead of nulls in subject position (as noted in Torregrossa et al. 2017), given that, for example, subject-verb agreement may not be fully mastered by some bilinguals. It should be noted that in the studies of Serratrice (2007) and Belletti and Guasti (2015), dominance is not taken into account as a factor motivating the overproduction of full DPs in object position, but it plays a crucial role in Torregrossa et al. (2017). | ||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 8 | The Boston Naming Test was originally designed for English, and later adapted to German and Italian with the reduced versions designed by Merten (2004) and Riva et al. (2000), respectively. | ||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 9 | This dataset has been collected and analyzed within the THALES project (principal investigator: Ianthi Maria Tsimpli) and the CoLiBi project—Cognition, Literacy and Bilingualism in Greek‒German-speaking children (principal investigators: Christiane Bongartz and Ianthi MariaTsimpli). | ||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 10 | The analysis relied on the assumption that vocabulary skills are a proxy for language proficiency (see Treffers-Daller 2013; Treffers-Daller and Rogers 2014 for a similar view). | ||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 11 | We included reference to both animate (e.g., the elephant and the giraffe) and inanimate characters (e.g., the helicopter). However, we decided not to include every inanimate character occurring in the stories, but to focus only on the most salient ones (i.e., the ones that are part of a reference chain). | ||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 12 | This kind of coding of REs has been evaluated against a set of data taken from different languages (Italian, Greek and German) and types of speakers (adults and bilingual and monolingual children). All the data were elicited by using the ENNI stories and are, thus, comparable with each other (see, e.g., Torregrossa et al. 2015; Torregrossa et al. 2018). In previous work, we coded REs also for the antecedent’s syntactic position (i.e., in a main or subordinate clause) and for distance between REs and their antecedent. Our decision to consider, for this study, only a subset of features depends on the observation (based on tentative analyses) that argument role of the antecedent and number of intervening characters (once the gender of the referents is taken into account) are the most relevant factors for referent’s activation. | ||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 13 | The REs in object position contained in the following narrative excerpt—produced by F2 (age: 13;2, BIS: −0.13)—are used to introduce referents (e.g., un aeroplanino ‘a small airplane toy’ in (ii) and l’amico, l’altro amico elefante ‘the friend, the other elephant friend’ in (vi)) and there is no instance of RE used to maintain reference in object position. Therefore, this narrative excerpt cannot verify the hypothesis concerning the use of overspecified forms in object position. Incidentally, it should be noted that in (vii) the participant omits the accusative masculine singular clitic pronoun lo, which refers to the airplane.

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 14 | One could argue that our study does not fully support this conclusion, since a monolingual control group is missing. The identification of overspecified DPs reported in this paper is based on a data-coding process that has been tested against several languages and validated for interrater agreement (e.g., Torregrossa et al. 2015; Torregrossa et al. 2017). Therefore, we are confident that our analysis includes only those full DPs that one could substitute with nulls or clitics without generating ambiguity. More in general, the present study shows that it is possible to account for (some aspects of) bilingual language production without resorting to monolingual control groups (Kupisch and Rothman 2016), which is done based on correlational analyses (between use of overspecified DPs and language experience in our case). It is not excluded that overspecification may occur in monolingual language production, too, due for instance to cognitive factors (see Arnold 2010 and references quoted therein). However, such cognitive constraints are supposed to influence monolingual and bilingual language production alike (cf. Torregrossa et al. 2017 for an analysis of how overspecification and underspecification result from the interaction between language experience and cognitive variables among different groups of bilinguals). | ||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 15 | However, Sorace’s (2011) claim that overt pronouns are default forms that counteract complex computations at the syntax-discourse interface cannot be maintained, since it does not comply with the observation that bilinguals tend to produce a greater amount of full DPs. Nor is it plausible that full DPs act as default forms (see the discussion in Section 1.1). | ||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 16 | The overuse of full DPs (instead of clitics and null subjects) has already been observed in the production of REs in Greek by Greek‒Albanian bilingual children, who are dominant in Albanian (see Torregrossa et al. 2017). Greek and Albanian are both null subject and clitic languages. | ||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 17 | It should be pointed out that the analysis of Müller and Hulk (2001) was formulated based on the production of very young bilinguals. Thus, transfer effects might still be visible in the early phases of bilingual language development, but cannot account for bilingual language production in later stages of acquisition. | ||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 18 | As suggested by one of the reviewers, another piece of evidence that grammatical knowledge is unaffected among the bilinguals considered in this study is the fact that in our corpus of narratives, we did not find any occurrence of “redundant” full DPs involving a violation of Principle C of Binding Theory. In other terms, the production of overspecified full DPs always occurs across clauses, not within clauses (or better said, not within the c-command domain of the antecedent). This observation is particularly relevant in view of the proposal by Balaban et al. (2016) to disentangle syntactic and discourse factors constraining the repetition of full DPs. | ||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 19 | Postverbal subjects may be licensed by a narrow-focus interpretation on the subject (followed by “emarginazione” (margination) of the object in the case of XP-V-S-O structures; see, a.o., Belletti 2004). In these contexts, the subject constituent is associated with intonational prominence. It should be pointed out that the narrow focus interpretation is not supported by the discourse context at stake. We will not discuss the possibility that in fact the bilinguals intended to express narrow focus, but did not master the prosodic means to mark it. | ||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 20 | It may be observed that a V2-grammar is not a necessary condition for XP-V-S orders. For example, Italian allows such structures in correspondence with the phenomena observed under footnote 16, wh-questions, frontings and unaccusative verbs followed by indefinite subjects (cf. Meisel et al. 2013 for discussion). However, as far as we know, the structural account by Müller and Hulk (2001) does not make any prediction concerning a situation in which two ambiguous languages (like German, which has VO and OV, and Italian, with VO and XP-V) enter in contact. | ||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Account | Prediction |

|---|---|

| a. Structural account (e.g., Müller and Hulk 2001) | overuse of overt pronouns in subject position and production of null objects (alias, clitic omissions) |

| b. Morphosyntactic complexity account (e.g., Liceras et al. 2012). | no overuse of overt pronouns in subject position (for objects, see footnote 3). |

| c. Processing account (Sorace 2011) | overuse of overt pronouns in subject and object position |

| d. Computational complexity account (Mateu 2015) | clitic omission in association with complex structures |

| e. Dominance-related account (Torregrossa et al. 2017) | overuse of full DPs in subject and object position |

| f. Language change account (e.g., Devlin et al. 2012) | use of invariable clitic forms |

| Measure | Mean | SD |

|---|---|---|

| Italian vocabulary | 11.7 | 6.3 |

| German vocabulary | 14.6 | 3.7 |

| Difference in vocabulary | −3 | 8.5 |

| Italian syntactic proficiency | 0.29 | 0.22 |

| Bilingual Index Score (BIS) | −0.08 | 0.25 |

| Units | Transcription (1) | Chain (2) | Type (3) | Gramm (4) | Ant-Gramm (5) | Characters (6) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| U1 | C’era un elefante e una giraffa [There was an elephant and a giraffe] | 1 | INDEF | SUBJ | INTRO | INTRO |

| U1 | C’era un elefante e una giraffa [There was an elephant and a giraffe] | 2 | INDEF | SUBJ | INTRO | INTRO |

| U2 | che stavano vicino [//] che stanno vicino a una piscina. [who were near [//] who are by a swimming pool] | 1 + 2 | RELPRO | SUBJ | SUBJ | 0 |

| U3 | La giraffa aveva un bel aerocottero [The giraffe had a nice helicopter] | 2 | DEFDP | SUBJ | SUBJ | 1D |

| U3 | La giraffa aveva un bel aerocottero [The giraffe had a nice helicopter] | 3 | INDEF | OBJECT | INTRO | INTRO |

| U4 | e ehm la giraffa non voleva dare l’aerocottero all’elefante [and ehm the giraffe did not want to give the helicopter to the elephant] | 2 | DEFDP | SUBJ | SUBJ | 1D |

| U4 | e ehm la giraffa non voleva dare l’aerocottero all’elefante [and ehm the giraffe did not want to give the helicopter to the elephant] | 3 | DEFDP | OBJECT | OBJECT | 1D |

| U4 | e ehm la giraffa non voleva dare l’aerocottero all’elefante [and ehm the giraffe did not want to give the helicopter to the elephant] | 1 | DEFDP | OBJECT | SUBJ | 2S |

| Type of Referring Expression | Frequency |

|---|---|

| Nulls | 98 |

| Clitics | 59 |

| overt pronouns | 13 |

| full DPs | 128 |

| Syntactic Configuration | Example | Frequency |

|---|---|---|

| a. clitic + verb | (1) La dà alla giraffa. CL.ACC.FEM.SG. give.3SG. to the giraffe (2) E le ha chiesto. and CL.DAT.FEM.SG. AUX.3SG. asked | 26 |

| b. cluster + verb | (3) glie-lo ridà alla giraffa. CL.DAT.FEM.SG.-CL.ACC.MASC.SG. give back.3SG. to the giraffe | 16 |

| c. verb + clitic | (4) a prender-lo. to take.INF. CL.ACC.MASC.SG. | 3 |

| d. causative | (5) e lo ha fatto volare. and CL. ACC.MASC.SG. AUX.3SG. made fly | 2 |

| e. OCC_low | (6) quindi non puó comprar-lo. therefore NEG can buy.INF.-CL.ACC.MASC.SG. | 4 |

| f. OCC_high | (7) il coniglio lo vuole prendere. the rabbit CL.ACC.MASC.SG. want take | 8 |

| Syntactic Position | Overt Pronouns | Full DPs |

|---|---|---|

| Subject position | 3 | 12 |

| Object position | 2 | 17 |

| Total | 5 | 29 |

| Child | BIS | Sentence | Type of Structure |

|---|---|---|---|

| F2 | −0.13 (low BIS) | (1) E ∅ ha preso con una […] [and has taken ∅ with one […]] | AUX + past participle |

| F3 | −0.34 (low BIS) | (2) Un coniglio ∅ voleva mettere al carrello. [A rabbit wanted to bind ∅ to the cart] | OCC |

| F4 | −0.36 (low BIS) | (3) e ∅ fa volando [and makes ∅ flying] | Causative |

| M4 | −0.53 (low BIS) | (4) e ∅ vole prendere [and wants to take ∅] | OCC |

| M3 | −0.03 (high BIS) | (5) e in pratica loro ∅ volevano uno nuovo [and basically they wanted one new ∅ (of it)] | NE-clitic |

| F8 | 0.018 (high BIS) | (6) peró non ∅ arriva [but not ∅ arrives (there)] | CI-clitic |

| M6 | 0.19 (high BIS) | (7) che ∅ ha fatto il nodino/il fiocchetto [that ∅ has tied the knot/the bow (there)] | (1) CI-clitic |

| (8) se ∅ potrebbe avere due [if he could have two (of them)] | (2) NE-clitic |

| Child | BIS | Sentence | Type of Structure/Type of Mismatch |

|---|---|---|---|

| M1 | −0.16 (low BIS) | (1) che lo vende, i palloni that it.ACC.MASC.SG. sells, the balloons.MASC.PLUR. | subordinate clause with clitic right dislocation (masc. acc. sing. > masc. acc. plur.) |

| F4 | −0.36 (low BIS) | (2) e la (l’aereo) dà alla giraffa and it ACC.FEM.SG. (the airplane.MASC.SG.) gives to the giraffe | ditransitive verb (fem. acc. sing. > masc. acc. sing.) |

| M5 | −0.11 (low BIS) | (3) e l’ ha fatto una treccia (al pallone) and it.ACC.MASC.SG. has tied a bow (to the balloon) | ditransitive verb (acc. masc. sing. > dat. masc. sing.) |

| M6 | −0.17 (low BIS) | (4) e la (l’aereo) sta provando per prender-la and it ACC.FEM.SG. (the airplane.MASC.SG.) is trying to take it ACC.FEM.SG. | OCC (fem. acc. sing. > masc. acc. sing.) |

| F1 | −0.03 (high BIS) | (5) che il // l’elefante la (l’aeroplanino) toccasse that the // the elephant it. ACC.FEM.SG. the airplane.MASC.SG. touches | (5) subordinate clause with subjunctive (fem. acc. sing. > masc. acc. sing.) |

| (6) e le (la giraffa e l’elefante) voleva aiutare and them.ACC.FEM.PL. (the giraffe FEM.SG. and the elephant MASC.SG.) wanted to help | (6) OCC (fem. acc. plur. > masc. acc. plur.) | ||

| F6 | 0.10 (high BIS) | (7) perché la butta là dentro (il pallone) because it.ACC.FEM.SG. throws there inside (the balloon.MASC.SG. ) | subordinate clause (fem. acc. sing. > masc. acc. sing.) |

| Word Order | Example | Frequency |

|---|---|---|

| a. presentative | (1) C’erano due conigli, un maschio e una femmina (M2) [There were two rabbits, a male and a female] | 19 |

| b. (neg) cl-V(O) | (2) La dà alla giraffa (F4) [CL.ACC.FEM.SG. gives to the giraffe] | 27 |

| (3) Non l’ ha fatta (M5) [NEG. CL.ACC.FEM.SG. has made] | ||

| c. (neg) V (O/S) | (4) ha chiesto (M6) [has asked] | 58 |

| (5) è arrivato un coniglio [has arrived a rabbit] | ||

| (6) ma non aveva i soldi [but NEG had the money] | ||

| d. S (neg/cl) VO | (7) Il papà l’ ha aiutati [the father CL.ACC.MASC.PL. has helped] | 22 |

| (8) però iddo non aveva cinque euro [but that one NEG had five euros] | ||

| e. XP SV(O) | (9) Poi la giraffa si arrabbia [Then the giraffe gets mad] | 12 |

| (10) Poi l’elefante ha chiamato l’amico // l’ altro amico elefante [Then the elephant has called the friend the other friend elephant] | ||

| f. SV(O) | (11) Il maschio ha visto ehm un negozio [the male has seen ehm a shop] | 74 |

| (12) e il coniglio va [and the rabbit goes] | ||

| g. XP VS(O) | (13) E dopo arriva la mamma [and then comes the mother] | 21 |

| (14) E poi ha visto il maschio un altro coniglio [and then has seen the male another rabbit] |

© 2018 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Torregrossa, J.; Bongartz, C. Teasing Apart the Effects of Dominance, Transfer, and Processing in Reference Production by German–Italian Bilingual Adolescents. Languages 2018, 3, 36. https://doi.org/10.3390/languages3030036

Torregrossa J, Bongartz C. Teasing Apart the Effects of Dominance, Transfer, and Processing in Reference Production by German–Italian Bilingual Adolescents. Languages. 2018; 3(3):36. https://doi.org/10.3390/languages3030036

Chicago/Turabian StyleTorregrossa, Jacopo, and Christiane Bongartz. 2018. "Teasing Apart the Effects of Dominance, Transfer, and Processing in Reference Production by German–Italian Bilingual Adolescents" Languages 3, no. 3: 36. https://doi.org/10.3390/languages3030036

APA StyleTorregrossa, J., & Bongartz, C. (2018). Teasing Apart the Effects of Dominance, Transfer, and Processing in Reference Production by German–Italian Bilingual Adolescents. Languages, 3(3), 36. https://doi.org/10.3390/languages3030036