Hop(p)la in French and German

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Literature Review

3. Materials and Methods

4. Results

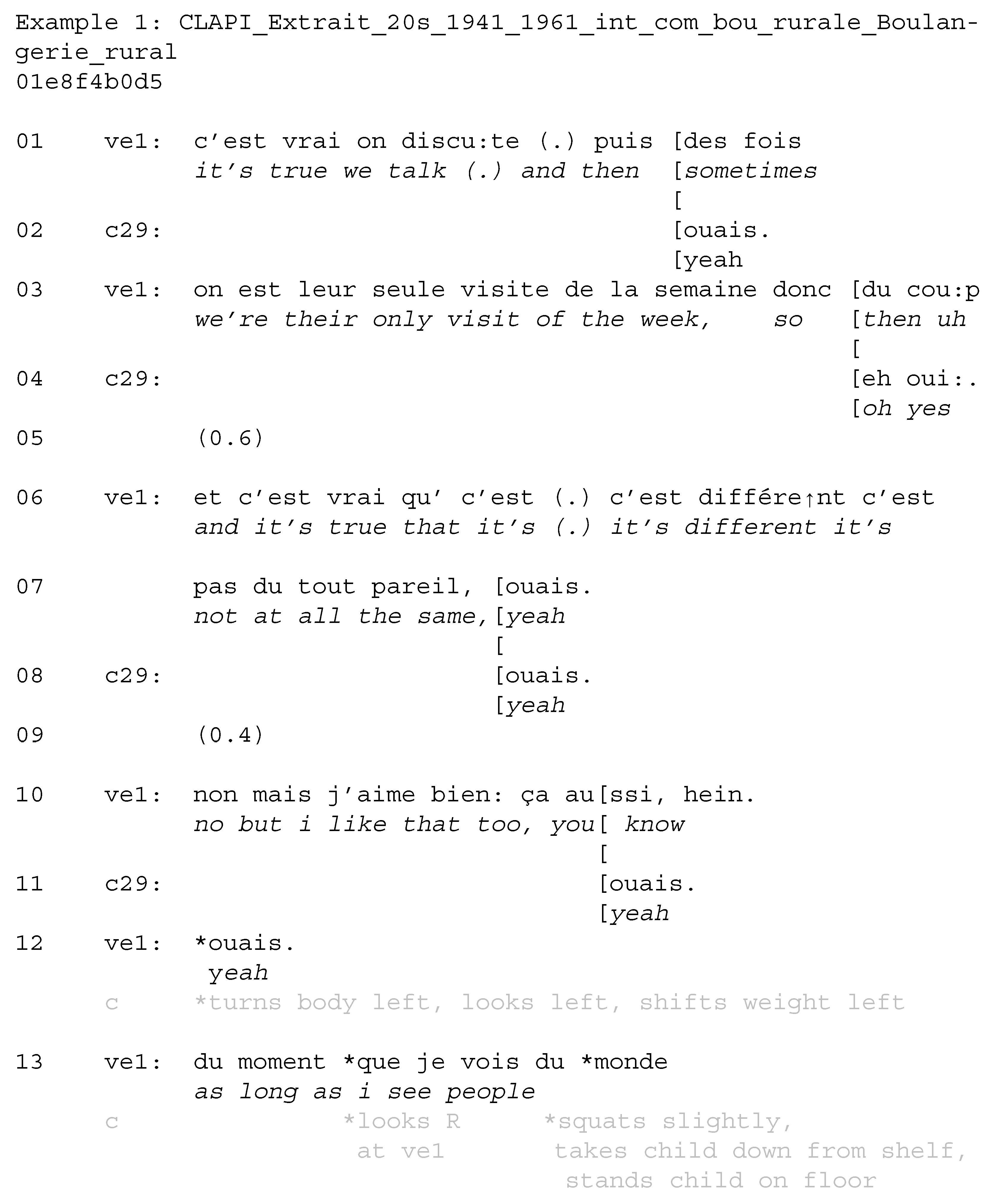

4.1. Hopla in French

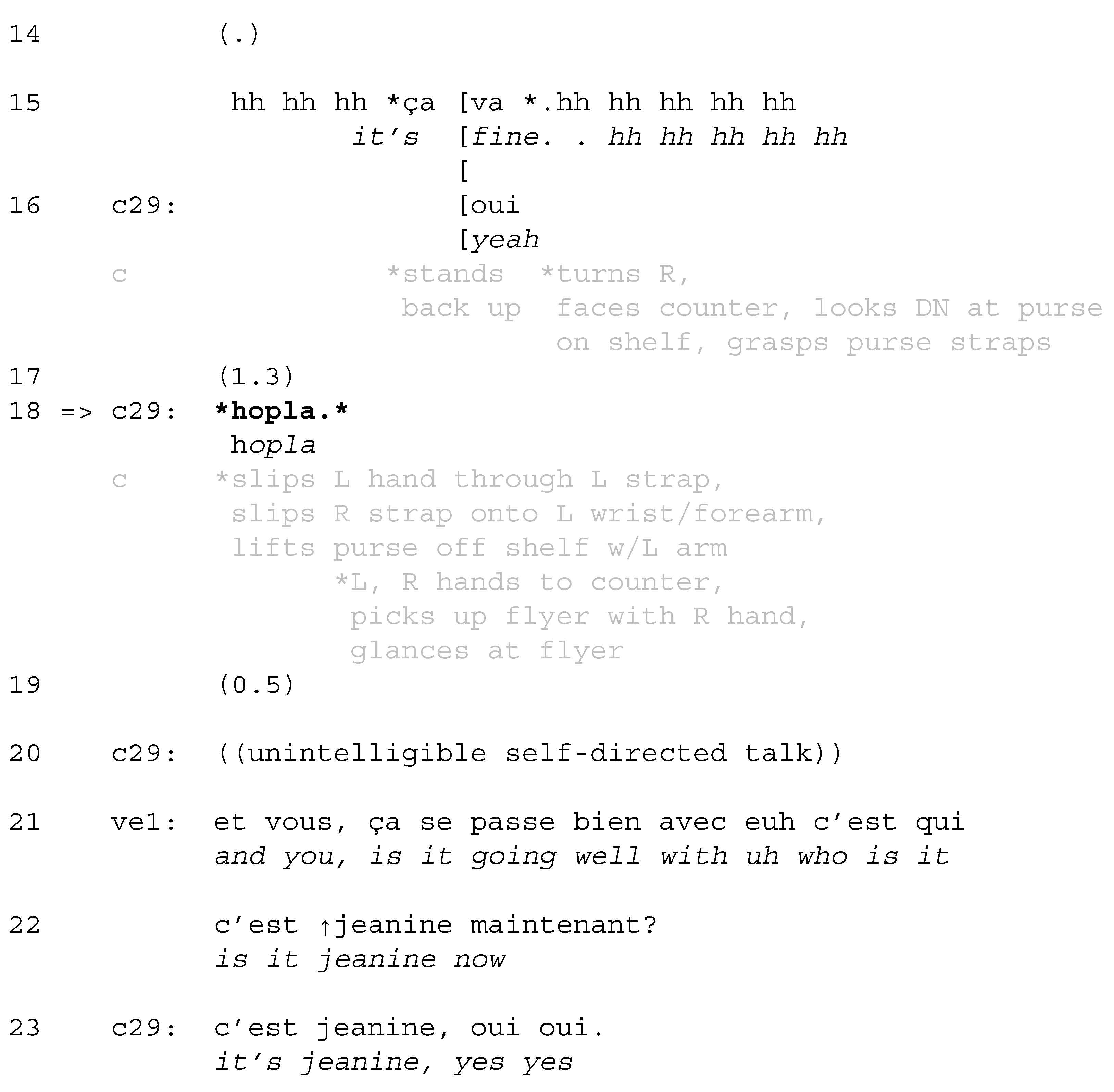

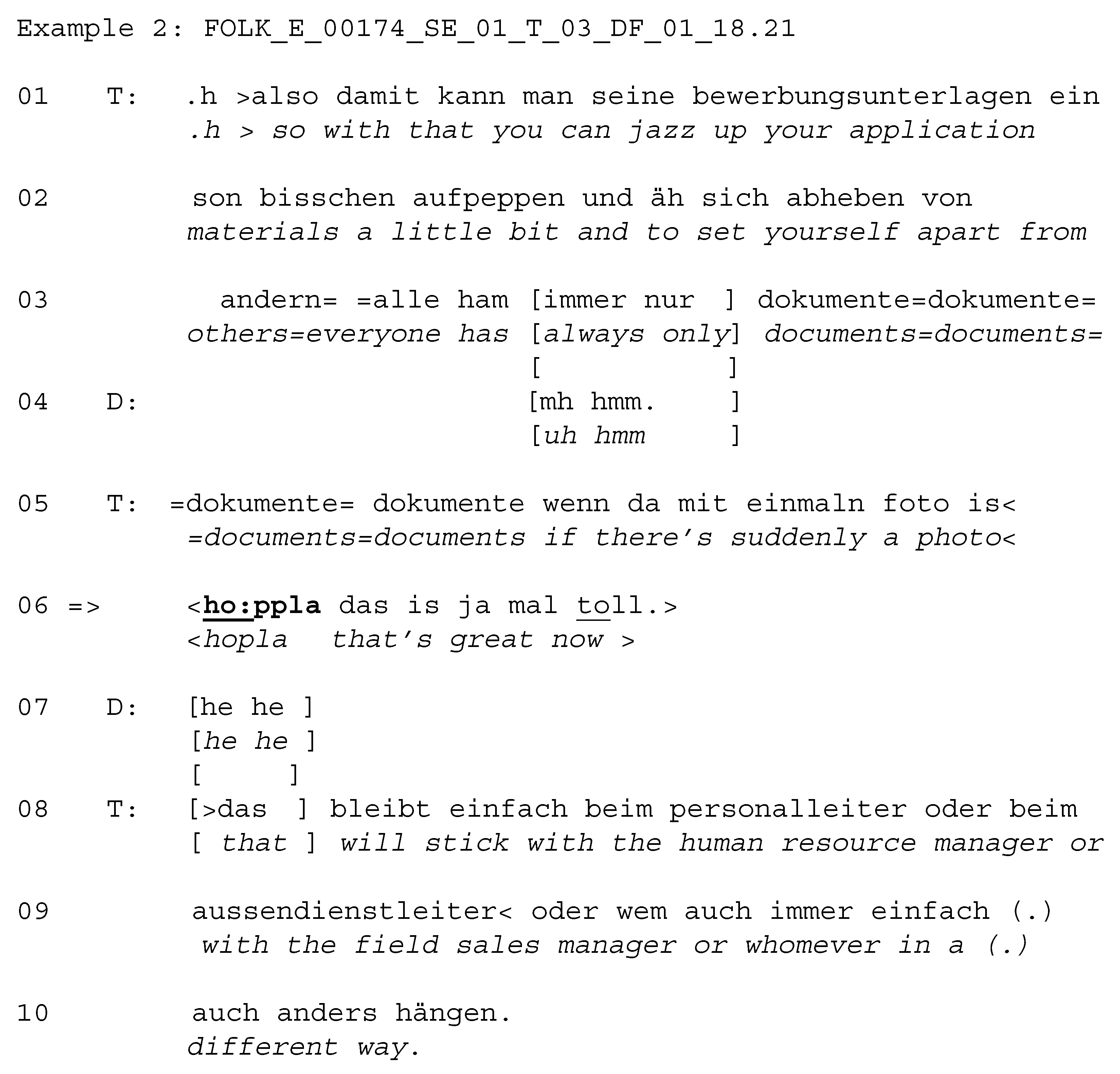

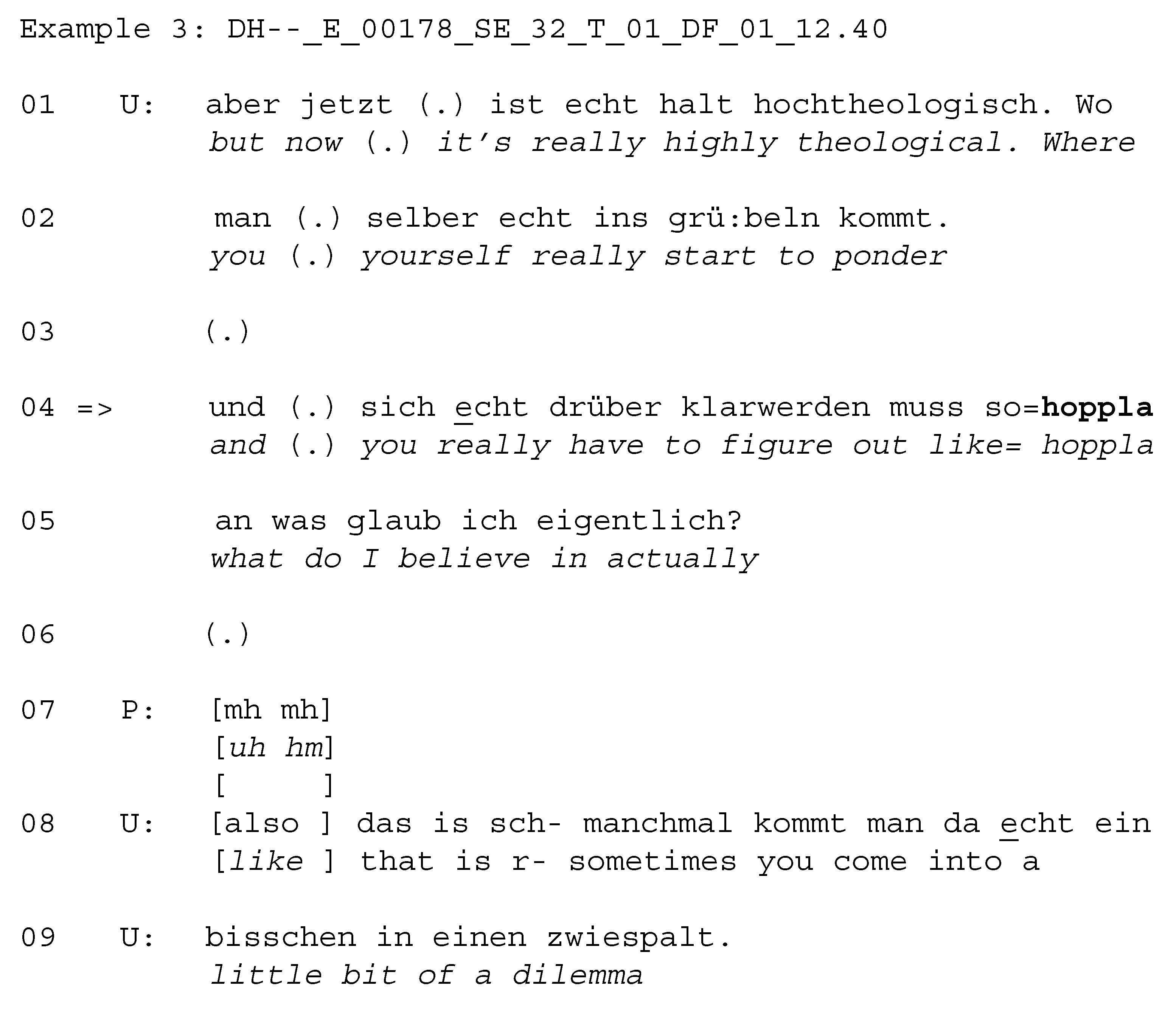

4.2. Hoppla in German

4.2.1. Surprise

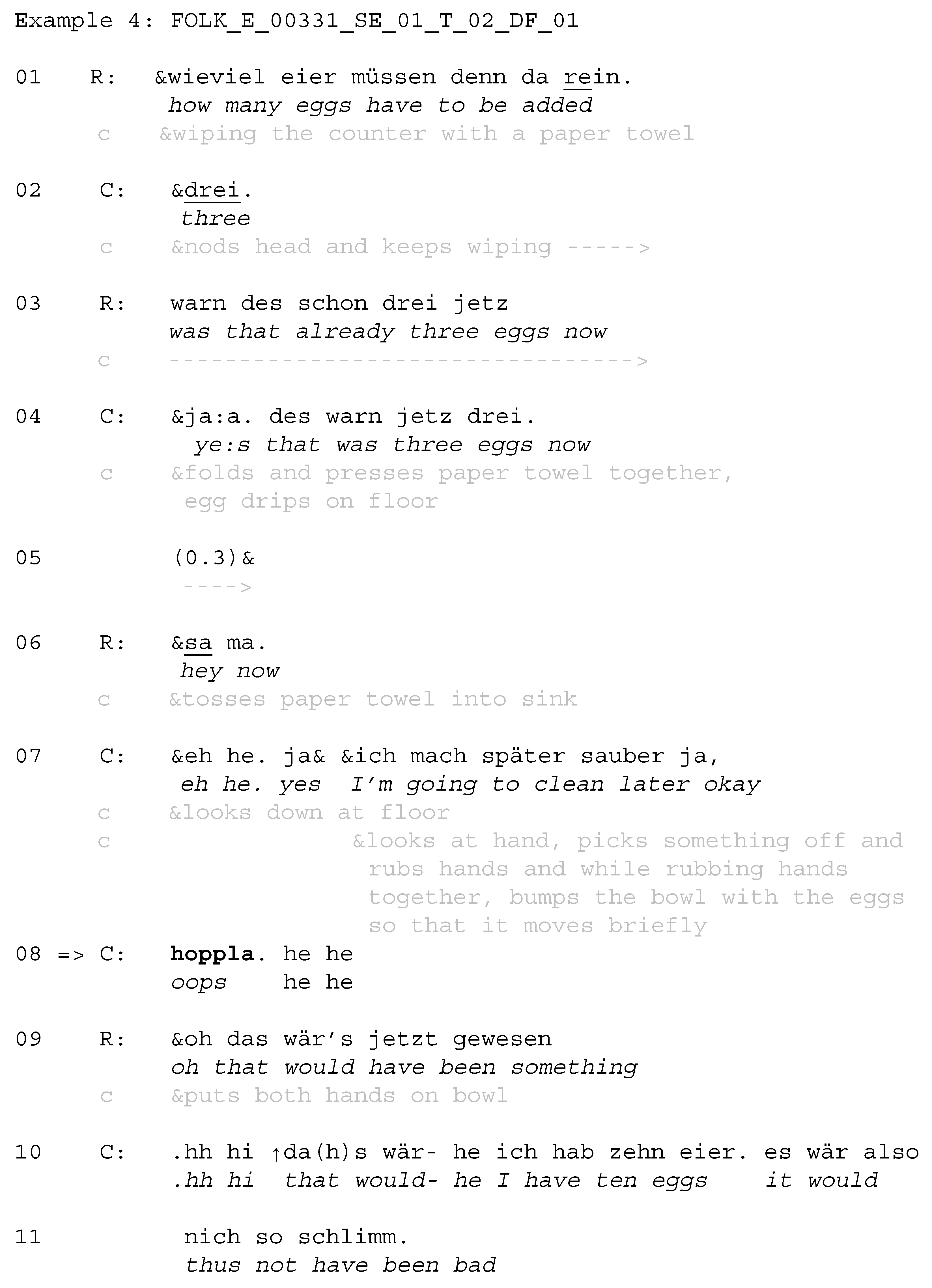

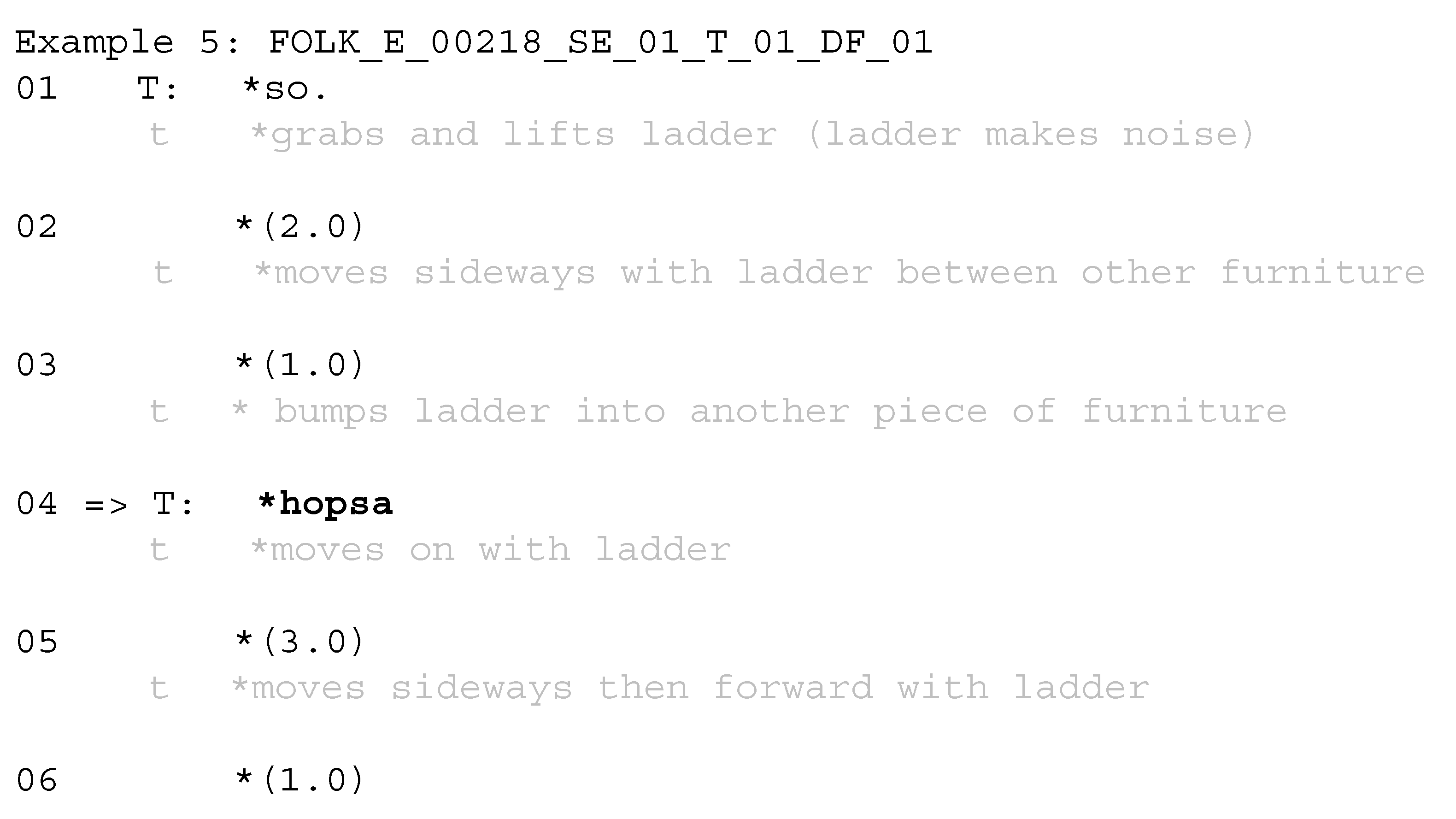

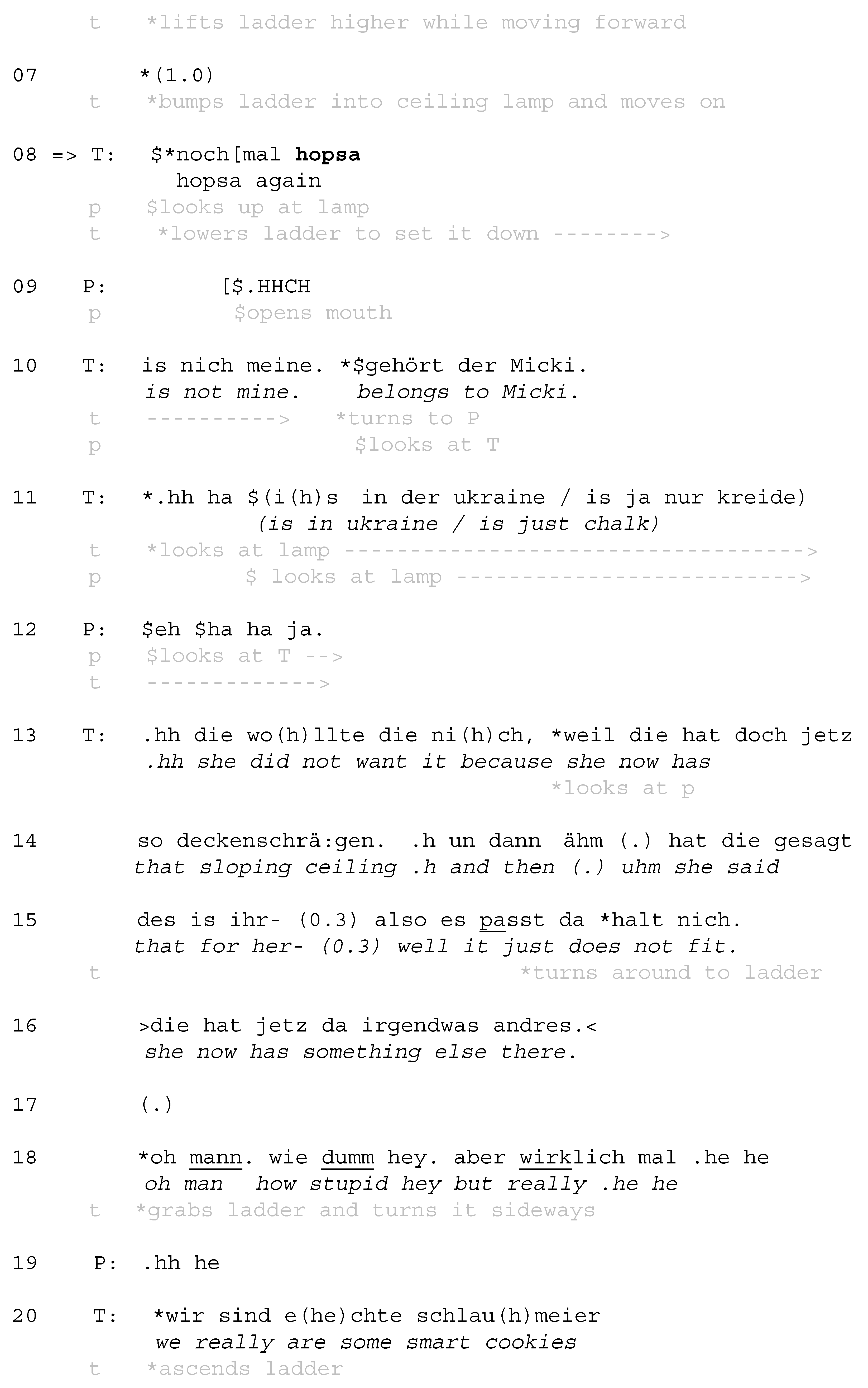

4.2.2. Unexpected Events of Minor Consequences

4.2.3. Summary of German Hoppla

5. Discussion and Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Ameka, F. (1992). Interjections: The universal yet neglected part of speech. Journal of Pragmatics, 18, 101–118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Atkinson, J. M., & Heritage, J. (Eds.). (1984). Structures of social action. Studies in conversation analysis. Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Barske, T., & Golato, A. (2010). German so: Managing sequence and action. Text & Talk, 30(3), 245–266. [Google Scholar]

- Brown, P., & Levinson, S. C. (1987). Politeness: Some universals in language usage. Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Daddi, S. (2019). Oups, hop, paf: French mini expressions that say a lot. The Connexion. French News in English since 2002. Available online: https://www.connexionfrance.com/magazine/oups-hop-paf-french-mini-expressions-that-say-a-lot/471722 (accessed on 6 June 2024).

- Dingemanse, M. (2024). Interjections at the heart of language. Annual Review of Linguistics, 10, 257–277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Drescher, M. (1997). French interjections and their use in discourse. In S. Niemeier, & R. Dirven (Eds.), The language of emotions. Conceptualization, expression, and theoretical foundation (pp. 233–246). John Benjamins. [Google Scholar]

- Drew, P., & Heritage, J. (2006). Editor’s introduction. In P. Drew, & J. Heritage (Eds.), Conversation analysis (Vol. 1, pp. xxi–xxvii). Sage. [Google Scholar]

- Duden. (1999). Das groβe Wörterbuch der deutschen Sprache. Dudenverlag. [Google Scholar]

- Eastman, C. M. (1992). Swahili interjections: Blurring language-use/gesture-use boundaries. Journal of Pragmatics, 18, 273–287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fiedler, S. (2024). The Grammar-in-use of direct reported thought in French and German: An interactional and multimodal analysis. Verlag für Gesprächsforschung. [Google Scholar]

- French word of the day: Hopla! The local France. (2020). Available online: https://www.thelocal.fr/20200106/french-word-of-the-day-hopla (accessed on 15 February 2025).

- Goffman, E. (1974). Frame analysis. Harper. [Google Scholar]

- Goffman, E. (1978). Response cries. Language, 54, 787–815. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Golato, A. (2003). Studying compliment responses: A comparison of DCTs and recordings of naturally occurring talk. Applied Linguistics, 24(1), 90–121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Golato, A. (2012a). German oh: Marking an emotional change-of-state. Research on Language and Social Interaction, 45(3), 1–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Golato, A. (2012b). Impersonal quotation and hypothetical discourse. In I. Buchstaller, & I. van Alphen (Eds.), Quotatives: Cross-linguistic and cross-disciplinary perspectives (pp. 3–36). John Benjamins. [Google Scholar]

- Golato, A. (2018). Turn-initial naja in German. In M.-L. Sorjonen, & J. Heritage (Eds.), At the intersection of turn and sequence: Turn-initial particles across languages (pp. 403–432). John Benjamins. [Google Scholar]

- Golato, P., & Golato, A. (n.d.). The use of interjections in French: The case of hopla, hop, and tac [Unpublished manuscript]. Department of World Languages and Literatures, Texas State University. [Google Scholar]

- Haileselassie, A. (2015). Study of the use and function of the discourse marker voilà in spoken French from a conversation analytic perspective [Ph.D. dissertation, University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign]. [Google Scholar]

- Heritage, J., & Sorjonen, M.-L. (Eds.). (2018). Between turn and sequence: Turn-initial particles across languages. John Benjamins. [Google Scholar]

- Hutchby, I., & Wooffitt, R. (2008). Conversation analysis (2nd ed.). Polity Press. [Google Scholar]

- James, D. (1972). Some aspects of the syntax and semantics of interjections. Chicago Linguistic Society, 8, 162–172. [Google Scholar]

- James, D. (1974). Another look at, say, some grammatical constraints on, oh, interjections and hesitations. Chicago Linguistic Society, 10, 242–251. [Google Scholar]

- Josep Cuenca, M. (2006). Interjections and pragmatic errors in dubbing. Meta, 51(1), 20–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Keevallik, L. (2018). Sequence initiation or self-talk? Commenting on the surroundings while mucking out a sheep stable. Research on Language and Social Interaction, 51(3), 313–328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Keevallik, L., & Ogden, R. (2020). Sounds on the margins of language at the heart of interaction. Research on Language and Social Interaction, 53(1), 1–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liddicoat, A. (2007). An introduction to conversation analysis. Bloomsbury Publishing. [Google Scholar]

- Meng, K., & Schrabback, S. (1999). Interjections in adult-child discourse: The cases of German HM and NA. Journal of Pragmatics, 31, 1263–1287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mondada, L. (2018a). Multiple temporalities of language and body in interaction: Challenges for transcribing multimodality. Research on Language and Social Interaction, 51(1), 85–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mondada, L. (2018b). Turn-initial voilà in closings in French: Reaffirming authority and responsibility over the sequence. In J. Heritage, & M.-L. Sorjonen (Eds.), Between turn and sequence: Turn-initial particles across language (pp. 371–412). John Benjamins. [Google Scholar]

- Nübling, D. (2001). Von oh mein Jesus! zu oje!: Der interjektionalisierungspfad von der sekundären zur primären Interjektion. Deutsche Sprache, 29, 20–45. [Google Scholar]

- Nübling, D. (2004). Die prototypische Interjekton: Ein Definierungsvorschlag. Zeitschrift für Semiotik, 26(1/2), 11–45. [Google Scholar]

- Padilla Cruz, M. (2017). On the origin and meaning of secondary interjections: A relevance-theoretic proposal. In A. Piskorska, & E. Wałaszewska (Eds.), Applications of relevance theory: From discourse to morphemes (pp. 299–326). Cambridge Scholars Publishing. [Google Scholar]

- Padilla Cruz, M. (2023). Paralanguage and ad hoc concepts. Pragmatics, 33(3), 343–367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reber, E. (2012). Affectivity in interaction: Sound objects in English. John Benjamins. [Google Scholar]

- Reber, E., & Couper-Kuhlen, E. (2010). Interjektionen zwischen Lexikon und Vokalität: Lexem oder Lautobjekt? In A. Deppermann, & A. Linke (Eds.), Sprache intermedial. Stimme und Schrift, Bild und Ton (pp. 69–96). de Gruyter. [Google Scholar]

- Rézeau, P. (Ed.). (2001). Dictionnaire des régionalismes de France. Géographie et histoire d’un patrimoine linguistique. De Boeck & Larcier—Éditions Duculot. [Google Scholar]

- Schegloff, E. A. (1995). Sequence organization. Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Schegloff, E. A. (1996). Some practices for referring to persons in talk-in-interaction: A partial sketch of a systematics. In B. A. Fox (Ed.), Studies in anaphora (pp. 437–485). John Benjamins. [Google Scholar]

- Schegloff, E. A. (2007). Sequence organization in interaction. A primer in conversation analysis (Vol. 1). Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Schulze, B., & Tabakowska, E. (2004). Interjections as a translation problem. In H. Kittel, A. P. Frank, N. Greiner, T. Hermans, W. Koller, J. Lambert, & F. Paul (Eds.), Übersetzung, translation, traduction (pp. 555–562). de Gruyter. [Google Scholar]

- Sheehan, B., Jin, H. S., Martin, B., & Kim, H. J. (2024). Wow! Interjections improve chatbot performance: The mediating role of anthropomorphism and perceived listening. Communication Research, 51(7), 891–917. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sidnell, J. (2010). Conversation analyis: An introduction. Wiley-Blackwell. [Google Scholar]

- Traverso, V. (2008). Cadres, espaces, objets et multimodalité. In C. Kerbrat-Orecchioni, & V. Traverso (Eds.), Les interactions en site commercial (pp. 45–76). ENS Éditions. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wierzbicka, A. (1992). The semantics of interjection. Journal of Pragmatics, 18, 159–192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wilkins, D. P. (1992). Interjections as deictics. Journal of Pragmatics, 18, 119–158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Golato, A.; Golato, P.S. Hop(p)la in French and German. Languages 2025, 10, 196. https://doi.org/10.3390/languages10080196

Golato A, Golato PS. Hop(p)la in French and German. Languages. 2025; 10(8):196. https://doi.org/10.3390/languages10080196

Chicago/Turabian StyleGolato, Andrea, and Peter S. Golato. 2025. "Hop(p)la in French and German" Languages 10, no. 8: 196. https://doi.org/10.3390/languages10080196

APA StyleGolato, A., & Golato, P. S. (2025). Hop(p)la in French and German. Languages, 10(8), 196. https://doi.org/10.3390/languages10080196