Abstract

The present paper addresses the aspectual categories of modern Bulgarian: viewpoint aspect (imperfective vs. perfective), temporal aspect (imperfect vs. aorist), and perfect aspect. More precisely, it concerns their morphological encoding, hierarchical relation, semantic contributions, and interaction. Within a compositional interval-relational framework, the study puts forward a synthesis of existing accounts so as to capture the Bulgarian aspect system as a whole. Among other things, it reveals that ‘aorist’ is a largely illusional grammatical entity, and demonstrates how an interval-relational analysis of the perfect can solve some puzzles associated with the so-called evidential moods.

1. Introduction

“[I]n contrast to other Slavic languages, Bulgarian has no restrictions on the combination of tense and aspect, i.e. perfective verbs may be used in the imperfect tense as may imperfective verbs in the aorist (unlike Serbian and Croatian, for example) and all verbs, whether perfective or imperfective, have forms for the future tense (unlike Russian)”.(Manova, 2007, p. 22)

The forms I address in the present paper are the following:

- Aorist and imperfect past-tense forms like (na)pìsàhme and (na)pìšehme, ‘(we) wrote’;

- -l-participles like na/pìsàli and na/pìšeli, ‘written.pl’).

The literature offers numerous proposals to account for the semantics and morphosyntax of the relevant grammatical categories. A few of these are as follows:

- Situation/lexical aspect (Moens & Steedman, 1988; Smith, 1991; Vendler, 1957; Verkuyl, 1972, 1993);

- Viewpoint/grammatical aspect (Arregui et al., 2014; Comrie, 1976; Johanson, 2000; Klein, 1994);

- Viewpoint aspect in Slavic (Avilova, 1976; Biskup, 2019, 2024; Brecht, 1985; Breu, 2000, 2009; Corre, 2015; Dickey, 2000, 2015, 2024; Fiedler, 1999; Forsyth, 1970; Grønn, 2004; Gvozdanović, 2012; Klein, 1995; Lehmann, 1999; Mueller-Reichau, 2013; Sell, 1994; Sonnenhauser, 2006b);

- Viewpoint aspect in BG (Andrejčin, 1976; Aronson, 1977; Biskup, 2024; Ivančev, 1976; Karagjosova, 2024b; Lindstedt, 1985; Manova, 2007; Maslov, 1959; Stankov, 1980);

- Aorist and imperfect in BG (Andrejčin, 1938; Desclés & Guenchéva, 1990; Guenchéva, 1989; Rivero et al., 2017; Rivero & Slavkov, 2014; Sonnenhauser, 2006a; Stankov, 1965);

- Perfect (aspect/tense) (Grønn & von Stechow, 2020; Iatridou et al., 2001; Klein, 1994; Pancheva, 2003; Pancheva & von Stechow, 2004; Paslawska & von Stechow, 2003; von Stechow, 1999);

- Perfect forms in BG (Fici, 2005; Fiedler, 1999; Guenchéva & Desclés, 1982; Hristov, 2020; Levin-Steinmann, 2004; Lindstedt, 1994; Pancheva & von Stechow, 2004; Trummer, 1971);

- Tense (Comrie, 1985; Dyke, 2013; Grønn & von Stechow, 2016; Mezhevich, 2008; Prior, 1957; Thelin, 1978);

- Tense in BG (Lindstedt, 1985; Nicolova, 2017; Pašov, 1976; Penčev, 1967; Rivero, 1994);

- BG inflectional morphology (Aronson, 1968; Manova, 2007; Pitsch, 2024; Press, 2024; Stankov, 1967).

Needless to say, all these analyses are at least partially controversial. Moreover, most of the formal analyses focus on peculiar grammatical phenomena using different theoretical frameworks, which makes it difficult to evaluate their mutual compatibility in a possible overall picture. In the present paper, I combine selected formal analyses that address specific portions of the BG aspecto-temporal system. It goes without saying that the results of my proposal can only be one step towards a possible overall picture of the BG aspect and tense system.

A specific problem of BG grammar is the status of aorist and imperfect—do we deal with aspect or tense? The following quote sheds some light on how opinions diverge:

“If aorist/imperfect is treated as something purely temporal, the opposition between p[er]f[ective]/i[m]p[er]f[ective] is usually treated as aspectual. If aorist/imperfect is analyzed as an aspectual category, this opposition is seen as a second aspectual category alongside (Breu, 2000) or subordinate to (Lindstedt, 1985) pf/ipf. Other conceptions deny that the pf/ipf opposition has the status of grammatical aspect altogether. Thus, Sell (1994) considers pf/ipf in Bulgarian as lexical, just as Johanson (2000) who regards this opposition as an expression of terminativity, while he claims that grammatical aspect in Bulgarian is expressed by means of aorist/imperfect”.(Sonnenhauser, 2006a, p. 116; translation H.P.)

Lindstedt (1985, p. 279) offers a promising though enigmatic answer:

“The much-discussed problem of the semantic nature of the aorist: imperfect opposition in Bulgarian is solved: the opposition is temporal, and therefore aspectual; or aspectual, and therefore temporal”.

But problems abound with respect to the numerous BG perfect(oid) periphrases (present perfect, pluperfect, future perfect, past future perfect; plus alleged evidential moods called narrative, conclusive, etc.), too. All these periphrases contain the -l-participle in either of two variants: the aorist participle or the imperfect participle. The latter poses at least two questions: What exactly does the characteristic suffix -l- encode? And what is the status and role of aorist and imperfect in these participles?

In sum, the task is to put forward a uniform analysis covering the whole range of relevant forms and categories, beginning with situation aspect, touching fundamental issues of BG verbal morphosyntax, and finally also concerning confirmativity. The present paper aims at providing such an analysis, relying on numerous excellent existing proposals. The aim is therefore not to add another novel account but to unify existing theories in a fruitful way hitherto unpracticed for BG.

2. Theoretical Preliminaries

2.1. Situation and Viewpoint Aspect

In what follows, I use the interval-relational framework put forward in Klein (1994). In a nutshell, this approach employs different types of intervals (portions of time points on a linear time line) to analyze situational, aspectual, temporal, and even modal (e.g., Mezhevich, 2008) notions.

Moreover, I follow Vendler’s (1957) classification, according to which verbs belong to one of four basic time schemata: state, activity, achievement, and accomplishment. This distinction, which Smith (1991) calls situation aspect (also called the inner/lexical aspect), refers to the internal constitution of situations denoted by verbs or full verb phrases.

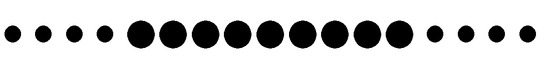

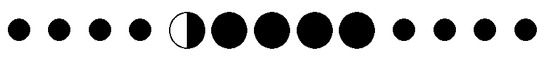

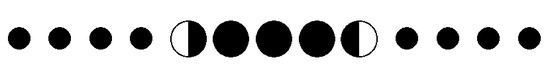

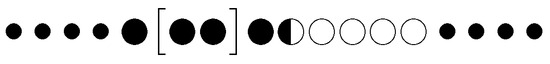

Achievements and accomplishments are telic as they consist of two sub-situations—a preparatory phase and a target state (Klein, 1994, speaks of “2-state contents”). In contrast, states and activities are atelic since they lack a target state.2 For the present investigation, it is sufficient to abstract away from the differences between states and activities, on the one hand, and accomplishments and achievements, on the other, and to merely distinguish between atelic and telic predicates, as schematized in Scheme 1 and Scheme 2, respectively.

Scheme 1.

Atelic predicates.

Scheme 2.

Telic predicates.

In Scheme 1 and Scheme 2, small bullets (•) represent time points forming the time line, while big bullets mark what Klein (1994, p. 2) calls situation time (ST), i.e., the interval for which the situation denoted by a verb holds true. In case of atelic predicates, ST consists of a single (designated) situation—represented above by big filled bullets (⬤). In case of telic predicates, ST has two subparts, the preparatory phase (⬤) and the target state (◯), the former giving rise to the latter. The semi-filled bullet (◐) marks the last time point (cessation) of the preparatory phase, which is identical to the first time point (inception) of the target state. I shall refer to this transition as culmination. Crucially, the culmination is a situation-internal (inherent) transition and must not be confused with cessation in time, which is a situation-external boundary.

It must be added that there are also situations which are atelic in the sense defined above (i.e., states or activities) but nonetheless include one or two situational boundaries. Such situations are usually derived, with said boundaries introduced by special affixes. Examples are inceptive and delimitative verbs like, e.g., začetjǎ, ’start reading’, and posèdjǎ, ’sit for a while’, respectively. Their lexical content does not include a target state, so they do not culminate and the term culmination cannot rightfully be applied to them. But still, they share with culminating situations the presence of at least one time point that delimits their run time and is thus comparable to the ◐-moment in Scheme 2; see the corresponding Scheme 3 and Scheme 4, respectively.

Scheme 3.

Inceptive predicates.

Scheme 4.

Delimitative predicates.

The category of viewpoint aspect (also called external/grammatical aspect) is usually taken to have two values: imperfective and perfective. Following Klein (1995, p. 689), perfective aspect denotes that the speaker asserts the transition from the preparatory phase to the target state. (In case of inceptives and delimitatives, the speaker asserts the relevant situational boundaries.) In other words, by choosing perfective aspect, the speaker asserts (to the addressee) the culmination of the relevant situation.3 To formalize this contribution from a cross-linguistic perspective, Klein (1994, p. 3) introduces a special interval he calls the assertion time (AT)—the time about which the speaker makes their utterance—which includes the culmination. In Scheme 5, I add the AT to Scheme 2, marking it with square brackets.4

Scheme 5.

Perfective aspect, telic.

It is impossible to do the same in Scheme 1 since atelic predicates lack a culmination. The only thing the speaker can assert in this case is some portion or the whole of the single (designated) state or activity; see Scheme 6. The speaker can do the same with (some portion or the whole of) the preparatory phase of telic predicates; see Scheme 7. In either case, this is the contribution of imperfective aspect.

Scheme 6.

Imperfective aspect, atelic.

Scheme 7.

Imperfective aspect, telic.

The distinction between atelic and telic predicates has a crucial implication for viewpoint aspect in BG: “Only telic verbs are represented in both perfective and imperfective aspect […], while atelic verbs are only imperfective” (Nicolova, 2017, p. 349). In other words, when a BG verb is perfective, the speaker necessarily asserts its culmination (if not its inception or delimitation as discussed above). In contrast, states and activities are always and exclusively imperfective.5

Using Smith’s (1991) typology of situation aspect, Table 1 summarizes what has been said so far about atelic and telic predicates in BG and their ability to be imperfective or perfective (cf. different features in Karagjosova, 2024a, 2024b).

Table 1.

Smith’s typology of situation-aspect and viewpoint-aspect options in BG.

Unlike situation aspect, which concerns the ST-interval, viewpoint aspect affects the AT-interval. More precisely, it relates AT and ST. The subsequent sections introduce two further categories that affect the AT-interval, though in another way: The first one I call temporal aspect—it encodes if AT is an open or closed interval. The second category is perfect aspect, which extends the AT-interval into the past (see Section 2.3).

2.2. Temporal Aspect

Following, e.g., Sonnenhauser (2006a), we need an additional aspectual category to account for BG data. This category encodes whether a situation ceased (finished) in an absolute or relative past (see also Section 3.4 and Section 3.5).

While cessation is clearly a temporal notion, Sonnenhauser (2006a) explains it by distinguishing between open and closed assertion-time (AT) intervals.6 Thus, we are faced with a category between aspect and tense, which is why I choose the term temporal aspect.

In mathematics, intervals are determined by their endpoints and whether the latter are part of the interval in question. Based on this, one distinguishes, i.a., open, half-open, and closed intervals, as defined in (1) (see Sonnenhauser, 2006a, p. 122).

| (1) | a. Open interval: no endpoint included; |

| b. Half-open interval: one endpoint included; | |

| c. Closed interval: both endpoints included. |

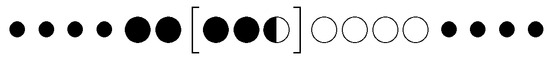

Now, let us assume a speaker chooses to assert the culmination of a telic situation in the past (e.g., ‘I wrote the letter’). They will use the perfective form of the corresponding BG verb (i.e., the prefixed root napìs-), so the addressee will perceive the situation as schematized in Scheme 5 above, which I repeat as Scheme 8.

Scheme 8.

Perfective aspect, telic.

Let us further assume that, when talking about the past, the speaker can, in their language, choose between presenting past situations as finished or unfinished. If the speaker wishes to present the situation as finished, they will have to choose a linguistic form that signals that AT is a closed or at least a half-open interval, which means that the last time point of the single designated state (of atelic predicates) or preparatory phase (of telic predicates) will be asserted. This is already the case in Scheme 8.7 Thus, the speaker asserts that the activity ceased. Using our example, this means that the writing of the letter culminated, so the letter was complete and available. There is no writing activity after this.

On the other hand, it the speaker wishes to present the same situation as unfinished, they will choose a linguistic form to signal that AT is an open interval, such that the endpoints of ST will not be asserted; see Scheme 9.

Scheme 9.

Open AT interval.

However, the speaker may also want to say that a situation ceased before it could even reach anypossible culmination; see Scheme 10.

Scheme 10.

Closed AT interval.

Since AT is a closed interval in Scheme 10, the preparatory phase does not continue and does not reach its possible culmination (if there is one). In other words, the writing activity ceased before the target state (‘letter complete’) could possibly be reached.

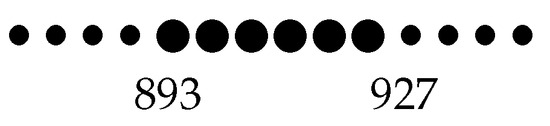

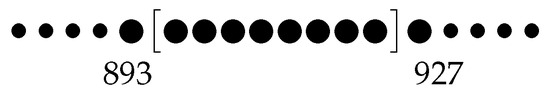

Let us consider an atelic example: It is recorded that Tsar Simeon ruled Bulgaria for 34 years, from 893 to 927. We can represent Simeon’s reign as the ST-interval in Scheme 11, whose left and right endpoints are the years 893 and 927, respectively.

Scheme 11.

Activity of ruling.

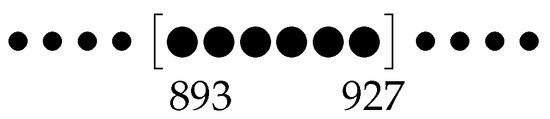

If a historian wishes to address Simeon’s rule in its totality, they cannot do so by resorting to the perfective aspect due to the fact ruling is atelic. However, they can choose to assert Simeon’s rule including its temporal boundaries as shown in Scheme 12. Here, AT is a closed interval, and Simeon’s rule is presented as a definite time period.

Scheme 12.

Activity of ruling, closed AT.

BG offers the aorist past tense form carùva to encode this meaning; see (2).

| (2) | Simeòn | carùva | ot | 893 | do | 927 | g. |

| S. | rule.pst.aor.3sg | from | 893 | until | 927 | y[ear]. | |

| ‘Simeon ruled from 893 to 927.’ | |||||||

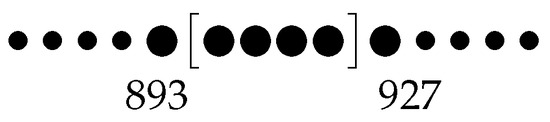

By contrast, if our historian wishes to present Simeon’s ruling as something going on in the past, say as a background for other events to be presented, they will exclude its temporal endpoints from their assertion, as depicted in Scheme 13.

Scheme 13.

Activity of ruling, open AT.

In Scheme 13, AT is an open interval. The BG verb form to encode this is the imperfect past tense, illustrated in (3).

| (3) | v | tovà | vrème, | kogàto | carùvaše | car | Simeòn, | … |

| in | this | time | when | rule.pst.ipf.3sg | tsar | S. | ||

| ‘in the time when tsar Simeon was ruling, …’ | ||||||||

As imperfect forms exclude temporal limits, the extent of the process or activity becomes vague. A possible effect of this is that the process or activity ‘grows wider’ in both the speaker’s and the addressee’s perspectives; cf. Scheme 14 to Scheme 13 above.

Scheme 14.

Activity of ruling, prolonged open AT.

Indeed, BG imperfect forms—both in the past and perfect (see Section 3.5)—tend to express long-lasting (‘open’) processes and activities.8 They may also denote ‘open’ chains that consist of multiple instances of the same process or activity.9,10

The aspecto-temporal difference encoded by the aorist and imperfect has been described earlier. Thus, Andrejčin (1938, p. 14) argues that the difference between imperfective and perfective (=viewpoint aspect) is a qualitative one (it refers to the internal quality of situations), whereas the difference between imperfect and aorist (=temporal aspect) is a quantitative one as it refers to the temporal extension of situations. In the same vein, Andrejčin et al. (1977, pp. 233–234) point out that one has to distinguish between aspectual and temporal completion, i.e., between presenting a situation as a complete whole, on the one hand, or as something finished before the time of utterance, on the other.

I address the morphology of aorist and imperfect past-tense forms in Section 3.4 and of their counterparts in perfect(oid) periphrases in Section 3.5, presenting multiple lines of evidence for the claim that the ‘open presentation’ of past situations (imperfect) is the marked choice while the ‘closed perspective’ (aorist) is the default.

2.3. Perfect Aspect

The third truly aspectual category is what Klein (1994) dubs perfect aspect (perf). Following Klein, the perfect locates AT in the post-time of ST; see (4).11,12

| (4) | - - - - - - - - - - - - ] - - - - - - |

Klein (1994) addresses primarily English and German data. But these languages do not encode viewpoint aspect in the same way as BG. In English, the perfect (in its diverse variants) can indeed be analyzed as a third aspect alongside imperfective/progressive and perfective. By contrast, BG perfect periphrases contain a main verb which is always already specified as either imperfective or perfective; see (5) and (6).

| (5) | Glèda-l-a | si | me, | počìta-l-a | si | me. |

| look.ipfv-perf-sg.f | be.2sg | me | respect.ipfv-perf-sg.f | be.2sg | me | |

| ‘You have looked after me, you have respected me.’ (Nicolova, 2017, p. 423) | ||||||

| (6) | Segà | săm | se | raz-căftjà-l | katò | jàbălka. |

| now | be.1sg | refl | pfv-blossom-perf.sg.m | like | apple.tree | |

| ‘Now I have blossomed like an apple tree.’ (Nicolova, 2017, p. 421) | ||||||

This means that either of the viewpoint aspects has already related ST and AT to each other when the perfect suffix -l- is added to the stem. In other words, the relevant BG clauses involve two hierarchically stacked aspectual categories. Therefore, the contribution of the BG perfect must be something other than what Klein (1994) is proposed for English.

Iatridou et al. (2001) (see also Pancheva, 2003) offer a formal alternative they call perfect time span (PTS). It consists of two AT-intervals: the basic interval AT-1 and a newly introduced AT-2, the latter located in the post-time of the former. Thus, one might say that AT-1 is pushed back into a relative past (see, e.g., Grønn & von Stechow, 2020).13 In addition, as viewpoint aspect (imperfective or perfective) relates AT-1 and ST, the latter is pushed back into a relative past, too. Eventually, we obtain Klein’s (1994) model enriched by an additional AT-interval, which allows us to account for the BG data.14

Iatridou et al. (2001, p. 284) assume that the perfect-operator in (7) contributes the PTS.

| (7) | ⟦perfect⟧’ PTS & |

| PTS if i is a final subinterval of |

The PTS-interval consists of two subintervals: (AT-1), which becomes existentially bound; and the newly introduced i (AT-2), which lies in the post-time of ; see (8).

| (8) | - - - - - - [AT-1 - - - ][AT-2 - - - ] - - - - - - |

In (9), I add an ST-interval that completely includes AT-1. This corresponds to the imperfective aspect as in the example počìtala, ‘respected’, in (5). I do not represent the right boundary of ST since the speaker does not assert it. In fact, the situation may still be in force at the time of utterance, and it may well continue after it. It is the distinction between aorist and imperfect that encodes whether situations in the past ceased (see Section 2.2).15

| (9) | - - - - - - {ST[AT-1 - - - ][AT-2 - - - ] - - - - - - |

Finally, the tense category determines the speaker’s (or, more generally, evaluator’s) position in time. It achieves this by relating the AT-interval to a time of evaluation (t*—the time of utterance in independent clauses) in either of the ways noted in (10) (see Klein, 1994, p. 124).

| (10) | Present tense: | t* incl AT |

| Past tense: | t* after AT | |

| Future tense: | t* before AT |

In case of the PTS as defined in (7), the AT-interval to be related to t* can only be AT-2, as AT-1 has been existentially bound. Thus, an imperfective present perfect can be schematized as in (11), where the bullet (⬤) represents t*.

| (11) | - - - - - - {ST[AT-1 - - - ][AT-2 - ⬤ - ] - - - - - - |

This means that, when the speaker makes their utterance, the subject of the clause is claimed to be in a state which temporally follows an interval from within a situation that started in the past (ST). Of the latter, the speaker asserts a portion excluding any possible internal boundaries (imperfective aspect). Ultimately, the speaker asserts the whole PTS-interval, which covers the stretch from the first moment of AT-1 up to the final moment of AT-2. Thus, the speaker makes a statement not only about some portion of the past situation denoted by the main verb, but also about the present state caused by that situation. The latter is reflected by a present-tense auxiliary verb.

Taking up example (5), the correspondence between the verb forms involved in a BG present–perfect periphrasis and the aspecto-temporal interpretations associated with them is sketched in (12).

| (12) | - - - - - - | {ST[AT-1 - - - ][AT-2 - | ⬤ - ] - - - - - - |

| počìtala | si |

Having thus outlined the theoretical basics necessary for my proposal, I turn to some fundamental assumptions regarding BG verbal morphology. After that, I present my proposal in Section 3 by addressing specific aspect and tense forms. In this, I also go into detail about more specific variants of the BG perfect.

2.4. Morphological Structure

Manova (2007, p. 24) proposes that a BG verb form has, in principle, the morphological slots in (13), which may host different types of affixes.16

| (13) | pref | – | base | – | dsuff | – | asuff | – | tm | – | isuff |

I modify this template: While Manova claims a separate slot for thematic markers (tm), I do not. On the other hand, I split Manova’s isuff-slot in two: a slot for tense suffixes (tns) and a slot for agreement suffixes (agr). Moreover, I rename Manova’s asuff-slot asp. Finally, I follow Manova in omitting the dsuff-slot since “Bulgarian verbal morphology […] exhibits very few derivational suffixes, and the derivational slot of a Bulgarian verb is empty by default” (Manova, 2007, p. 24). Thus, my representations of BG verb forms involve the slots in (14).

| (14) | pref | – | base | – | asp | – | tns | – | agr |

3. Bulgarian Tense–Aspect Forms

Within the Slavic branch, BG possesses a particularly rich and productive system of tense–aspect forms. Grammars usually count the nine tenses listed in Table 2, three of which are synthetic (S), while the rest are periphrastic (P) (Tilkov et al., 1983, p. 209; see also, e.g., Hauge, 1999; Krăstev, 2005; Nicolova, 2017; Scatton, 1984).

Table 2.

Bulgarian tenses.

The fact that the main verb in all tenses is necessarily either imperfective or perfective (see Section 3.2) documents that the categories of tense and viewpoint aspect are closely intertwined. Nonetheless, a strictly compositional analysis is possible.

In what follows, I describe the BG present tense, the two past tenses called aorist and imperfect, and some of the perfect periphrases. They are made up of the crucial aspecto-temporal ingredients present throughout the BG verbal system, so explaining them in a compositional way enables us to explain all remaining tenses, too.17

3.1. Conjugational Classes

BG verbs are commonly divided into three conjugational classes. This division relies on the vowel that precedes the present-tense (or rather agreement) inflections.18 Therefore, verbs from classes I, II, and III may also be referred to as e-verbs, i-verbs, and a-verbs, respectively.

Classes I and II have subclasses that reflect the differences between the present stem and the aorist stem (see Tilkov et al., 1983, p. 304; Scatton, 1993, p. 216). To show these differences, Table 3 and Table 4 (based on Manova, 2007, pp. 22–23) give full paradigms of the present and aorist past tense, respectively.

Table 3.

Present-tense paradigms.

Table 4.

Aorist past-tense paradigms.

It is a controversial question whether BG verbs are stored in the mental lexicon with one single underlying stem (see Aronson, 1968; Scatton, 1984; van Campen, 1963) or with two stem variants each (see, e.g., Hauge, 1999; Nicolova, 2017; Tilkov et al., 1983). In this study, I follow Scatton’s (1984) one-stem approach: He claims that, when suffixes are added to the single underlying stem, possibly illicit sound combinations become regularly adjusted by phonological rules such as truncation and augmentation. Moreover, softening or desoftening applies when the vowels /e/ and /i/ end up in a position following certain consonants. I elaborate on such operations when necessary.

3.2. Viewpoint-Aspect Distinctions

Like all Slavic languages, BG employs morphological means to encode the category of viewpoint aspect (see Section 2.1). Thus, for instance, the simplex verb in (15) is imperfective. Its perfective counterpart with (nearly) the same lexical meaning is the prefixed verb in (16a). Unlike (16a) where the prefix seems to be semantically vacuous,19 other perfectivizing prefixes obviously contribute meaning. The result is a new lexeme like (16b). Be that as it may, prefixation gives rise to perfective stems as a rule.

| (15) | pìšă | pìšeš | (imperfective) |

| write.prs.1sg | write.prs.2sg | ||

| ‘write’ | |||

| (16) | a. | na-pìšă | na-pìšeš | (perfective) |

| on-write.prs.1sg | on-write.prs.2sg | |||

| ‘write [down]’ | ||||

| b. | pre-pìšă | pre-pìšeš | ||

| over-write.prs.1sg | over-write.prs.2sg | |||

| ‘write [over] (i.e. copy)’ | ||||

Irrespective of whether the prefixed stem differs in meaning from the simplex base, it can further be regularly transformed into a so-called secondary imperfective by adding the productive suffix -va-.20 All resulting forms belong to conjugational class III (see Section 3.1). Examples are given in (17) (for more details, see Karagjosova, 2024b; Manova, 2007).

| (17) | a. | napìs-va-m | napìs-va-š | (sec. imperfective) |

| on.write-ipfv-prs.1sg | on.write-ipfv-prs.2sg | |||

| ‘write [down]’ | ||||

| b. | prepìs-va-m | prepìs-va-š | ||

| over.write-ipfv-prs.1sg | over.write-ipfv-prs.2sg | |||

| ‘write [over] (i.e. copy)’ | ||||

Secondary imperfectives with semantically vacuous prefixes are pragmatically marked, in that their range of use is restricted as compared to those with ‘meaningful’ prefixes.

The examples in (15) to (17) illustrate what Manova (2002, 2007) calls aspectual triple opposition.21,22 In addition, Manova argues that the members of that triple are regularly derived from each other, as shown in (18).

| (18) | imperfective | → | perfective | → | secondary imperfective |

| pìšeš | na-pìšeš | napìs-va-š |

In template (14), aspectual prefixes occupy the pref-slot. However, it must be noted that the prefixes themselves are lexical rather than grammatical elements (which applies as well to seemingly vacuous prefixes; see note 19). Still, by turning atelic into telic predicates, the grammatical impact is that the resulting telic verbs become perfective in the first place. To capture this, Biskup (2017) makes the following claim:

“I take the position that prefixes […] contribute telicity, in addition to perfectivity. I analyze the connection between telicity and perfectivity in the way that the prefix (an incorporated preposition) introduces a causal relation between the verbal part and the prepositional part of the prefixed predicate and in addition has a perfective property […]. The incorporated preposition bears a Tense-feature with the value [perfective] and values the Tense-feature of the aspectual head […]”.(Biskup, 2017, p. 18)

Omitting details, this means that prefixes cause and reflect perfectivity without being aspect markers sensu stricto. By contrast, the imperfectivizing suffix -va- is such a marker and should therefore occupy the asp-slot. Thus, I analyze the secondary imperfective prepìsvame as in (19). Note that, according to (18), the -va-suffix must somehow overwrite/neutralize the perfectivity initially associated with the prefix. I take it that this neutralization affects only the formal pfv-feature, which is responsible for the perfective interpretation of prefixed forms. When this feature becomes annulled by -va-, there will also be no perfectivity. Instead, the ipfv-feature introduced by -va- causes the imperfective interpretation.

| (19) | pref | – | base | – | asp | – | tns | – | agr |

| pre | pìs | va | me | ||||||

| ‘write’ | ipf | (prs) | 1pl |

Note furthermore that round brackets around a grammatical feature denote that this feature lacks formal expression, so as to be interpreted by default. Thus, in (19), the absence of a dedicated tense suffix gives rise to the default value prs. Moreover, I claim that if there is an empty default slot as just described, the next suffix to its right adopts the function of realizing the relevant default feature in addition to its own feature(s). For (19), this means that the agreement suffix -me assumes the additional function of a tense marker; see (20).

| (20) | pref | – | base | – | asp | – | tns | – | agr |

| pre | pìs | va | me | ||||||

| ‘write’ | ipf | prs.1pl |

Having thus determined the place of aspect markers in BG, I address individual tense form(ation)s in the subsequent sections.

3.3. Present Tense

Table 5.

Present-tense paradigms.

Table 6.

Present-tense inflections.

This shows that 2sg, 3sg, and 2pl share the same inflectional suffixes across all conjugations, while class III has individual variants in 1sg, 1pl, and 3pl.

Table 5 shows that verbs from classes I and II employ the thematic vowels -e- and -i-, respectively, to build their present-tense forms. In my analysis, thematic vowels occupy the asp-slot, so it is likely that they encode some aspectual meaning. My claim is that they reflect the openness of the assertion-time (AT) interval, as proposed in Section 2.2.

In Section 3.1, I decided to follow Scatton’s (1984) approach, saying that BG verbs have one single underlying stem. Table 7 shows what this stem looks like for each of the illustrative verbs in Table 5.24

Table 7.

Single underlying stems.

To show how these theoretical ingredients interact to yield the surface forms in Table 5, I analyze present-tense forms from classes I and II in (21) and (22), respectively.25 The feature open reads ‘open AT-interval’.

| (21) | a. | base | – | asp | – | tns | – | agr | (class I.1) |

| /čet/ | /e/ | /š/ | |||||||

| čet | è | š | |||||||

| ‘read’ | open | prs.2sg | |||||||

| b. | base | – | asp | – | tns | – | agr | (class I.2) | |

| /pìjna/ | /e/ | /ă/ | |||||||

| pìjn | ă | ||||||||

| ‘sip’ | (open) | prs.1sg | |||||||

| c. | base | – | asp | – | tns | – | agr | (class I.3) | |

| /igrà/ | /e/ | ||||||||

| igrà | e | ||||||||

| ‘play’ | open | (prs.3sg) | |||||||

| d. | base | – | asp | – | tns | – | agr | (class I.3) | |

| /làja/ | /e/ | /ăt/ | |||||||

| làj | ăt | ||||||||

| ‘bark’ | (open) | prs.3pl |

| (22) | a. | base | – | asp | – | tns | – | agr | (class II.1) |

| /vis/ | /i/ | /š/ | |||||||

| vis | ì | š | |||||||

| ‘hang’ | open | prs.2sg | |||||||

| b. | base | – | asp | – | tns | – | agr | (class II.2) | |

| /stroì/ | /i/ | /ă/ | |||||||

| stroj | ă | ||||||||

| ‘build’ | (open) | prs.1sg | |||||||

| c. | base | – | asp | – | tns | – | agr | (class II.3) | |

| /mìsli/ | /i/ | ||||||||

| mìsl | i | ||||||||

| ‘think’ | open | (prs.3sg) |

While examples (21a), (21c), and (22c) are straightforward, the remaining examples involve the application of phonological operations to adjust illicit sound combinations. Thus, in (21b), the thematic vowel /e/ causes the deletion of the stem-final vowel /a/,26 while the vocalic agreement suffix /ă/ causes the same in turn with /e/. These subsequent truncations yield the surface form pìjnă. In the same vein, the theme /e/ in (21d) deletes the stem-final /a/ and is itself deleted by the agreement suffix /ăt/, which gives the surface form làjăt. Similarly, the stem-final // and /ì/ in (22a) and (22b), respectively, fall victim to the thematic vowel /i/, which inherits their lexical stress.

Class-III verbs differ as they are athematic. I claim that this corresponds to the absence of the asp-slot.27 As a result, the consonantal agreement suffixes can be added without adjustments. On the other hand, class-III verbs cannot encode aspectual semantics the way class-I and class-II do. I illustrate this analysis of class-III verbs in (23).

| (23) | a. | base | – | tns | – | agr | (class III: simplex) |

| /ìska/ | /š/ | ||||||

| vis | š | ||||||

| ‘want’ | prs.2sg | ||||||

| b. | base | – | tns | – | agr | (class III: secondary imperfective) | |

| /prepìsva/ | /š/ | ||||||

| vis | m | ||||||

| ‘copy’ | prs.1sg |

Note that (23b) is the analysis of the secondary imperfective prepìsvame, which I already analyzed in (19). The difference between the two analyses is only apparent: Focusing on their derivation—which I did in (19)—secondary imperfectives involve the addition of -va-, which undoubtedly occupies the asp-slot. On the other hand, the addition of -va- determines that the resulting verb belongs to conjugation III and therefore lacks the asp-slot—which is what analysis (23b) highlights. In other words, the asp-suffix -va- derives secondary imperfectives, at the same time excluding the addition of any further aspect suffix. This explains, among other things, why secondary imperfectives cannot repeatedly be imperfectivized by adding a second -va- (*prepìsvavam), and also why there can be no (underlying) thematic vowel in class-III verb forms.

There are two crucial implications following from the above analyses.

First, the thematic vowels in classes I and II reflect the openness of the AT-interval (Section 2.2). However, Nicolova (2017, p. 375) argues that this feature is non-distinctive since, in the present tense, there is no ‘closed’ (non-continuative) counterpart. As will be shown in Section 3.4 and Section 3.5, the situation is different in the past tense as well as in -l-periphrases, where the ‘open’ imperfect contrasts with the ‘closed’ aorist, which makes open a distinctive feature in these forms.28

Second, class-III verbs are generally incapable of encoding the openness of AT. This holds true not only for the present tense but also for the imperfect. Therefore, class-III verbs are largely ambiguous between aorist and imperfect in the past tense (Section 3.4) and in perfect periphrases (Section 3.5).

3.4. Past Tense

Regarding the past tense, BG stands out from all other Slavic languages in two respects: First, it retains and productively employs the synthetic past-tense forms aorist and imperfect. Second, it productively derives both the aorist and imperfect forms from either viewpoint aspect.29 In other words, BG has imperfective and perfective imperfects as well as imperfective and perfective aorists. This is illustrated in (24) and (25).

| (24) | a. | Kupìx | si | dnès | mnògo | knìgi, |

| buy.pfv.aor.1sg | refl | today | many | books | ||

| ‘I bought a lot of books today,’ | ||||||

| b. | kupùvax | gi | cjàl | čàs. | ||

| buy.ipfv.aor.1sg | them | whole | hour | |||

| ’I was buying them for a whole hour.’ (Andrejčin, 1978, p. 178) | ||||||

| (25) | Štom | napìšeše | pismò, | tòj | ti | otgovàrjaše. |

| as.soon.as | write.pfv.ipf.3sg | letter | he | you.dat | answer.ipfv.ipf.3sg | |

| ‘As soon as you wrote the letter, he would answer you.’ | ||||||

| (Bertinetto & Delfitto, 2000, p. 215) | ||||||

For the sake of comparability, I repeat Table 4 from Section 3.1 as Table 8 to supply the reader with full aorist past-tense paradigms.30 Table 9 gives the imperfect paradigms.

Table 8.

Aorist past-tense paradigms.

Table 9.

Imperfect past-tense paradigms.

Table 8 shows that to form the aorist past tense the vowels that underlie the division into conjugations (-e-, -i-, and -a-) are replaced by other vowels or no vowel at all in classes I.2, I.3, I.4, and II.1. By contrast, they are left unchanged in classes I.1, II.2, II.3, and III. In case of the imperfect past tense, the latter holds for classes I.2, I.3, I.4, and III. On the other hand, the vowels are replaced with -a- or -e- in class II and to some extent also in class I.1.

The morphological analysis of aorist and imperfect forms is controversial. However, most authors agree that imperfect forms have the marker /ě/31 added to the root or in place of the present-tense vowel (see, e.g., Tilkov et al., 1983, pp. 325–327; Scatton, 1984, p. 185; Krăstev, 2005, pp. 105–106; Hauge 1999, p. 98; Nicolova, 2017, p. 397). The resulting form is then usually called the imperfect stem.

But opinions diverge as concerns the remaining inflectional material, and most crucially the overall analysis of aorist forms. Many descriptions present the inflections -x, -xme, -xte, and -xa as markers of both aor and ipf, with the exception of the 2/3sg -še and -⌀, which are peculiar for ipf and aor, respectively. This means that the burden of discriminating aorist from imperfect is primarily laid on the vowels that precede the inflections.

Scatton (1984) is more explicit as he isolates the suffix -x-, which he claims marks the past tense. Concerning /ě/, Scatton analyzes it as a dedicated imperfect suffix (his “*A”). Moreover, his compositional analysis implies that verb stems including /ě/ are specified as imperfect before they become specified as past tense—which will be helpful when analyzing imperfect participles in Section 3.5. In (26), I apply Scatton’s analysis to the imperfect past tense pìjnexme, ‘(we) sipped’ (class I.2), placing the imperfect suffix in the asp-slot.

| (26) | base | – | asp | – | tns | – | agr |

| /pìjna/ | /ě/ | /x/ | /me/ | ||||

| pìjn | e | x | me | ||||

| ‘sip’ | ipf | pst | 1pl |

Note that despite the fact that the surface imperfect stem pìjne- is identical to the present stem (see Table 3), the two stems differ in their underlying nature: The present stem involves the vowel /e/, whereas the imperfect stem contains /ě/. The same holds for classes I.3 and I.4. Thus, unlike stated above, the addition of the imperfect /ě/ takes place in all conjugations except class III. This receives a straightforward explanation under the assumption that these verbs are athematic and lack the asp-slot (see Section 3.3). In other words, there is no room for the imperfect suffix /ě/ in class-III verbs. As a consequence, they are ambiguous between imperfect and aorist, with the exception of the 2/3sg due to their specific inflections.

Unlike imperfects, aorists do not exhibit a uniform marker. As Table 8 shows, the slot where imperfects have /ě/ is occupied by one of the vowels -o- (-e-), -(j)a-, or -i-. Analyzing these vowels as dedicated aorist suffixes, one will hardly be able to find any systematic pattern to determine their choice. Moreover, it seems improbable that the same grammatical notion should be encoded by three vowels that can by no means be treated as allomorphs.

The one-stem approach (see Section 3.3) avoids this issue. The vowel that occurs in aorist forms is just the final vowel of the single underlying stem. This can be shown by comparing the ‘aorist stems’, as illustrated in Table 8, with the underlying stems listed in Table 7—see Table 10.

Table 10.

Single underlying stems vs. ‘aorist stems’.

There are only two differences that call for an explanation:

(i) The ‘aorist stem’ in class I.1 shows the vowel -o- (or -e-), while the underlying stem does not. A straightforward explanation is that the underlying stems of verbs from class I.1 are consonantal (another example is /pek/ ‘bake’). Since the aorist inflections are consonantal, too, their addition requires the insertion of a fill-in vowel.32 Consequently, the ‘aorist stem’ of the relevant verbs is actually identical with their underlying stem, and there is no exception whatsoever. The fill-in vowel is inserted to ensure pronounceability; see analysis (27) for the form čètoxme, ‘(we) read’.

| (27) | base | – | asp | – | tns | – | agr |

| /čet/ | /x/ | /me/ | |||||

| čèt+o | x | me | |||||

| ‘read’ | (aor) | pst | 1pl |

(ii) The above comparison shows that aorists can have their stress on the pre-inflectional vowel -a-, which serves to disambiguate them from imperfects primarily in cases where the two forms would otherwise be homonymous. Except for the 2/3sg, homonymy regularly occurs in class III due to the impossibility of adding the imperfect suffix (see Section 3.3 and above). Stress on the pre-inflectional -a- is strongly marked since the basic (lexical) stress position of class-III verbs is always on the syllable preceding it. I take it that the relevant stress shift is a post-morphological operation. (28) illustrates my analysis for the aorist iskàxme, ‘(we) wanted’. I add the aor-feature below the stem since it is the marked stress on -a- which reflects the aorist. Without stress shift (ìskaxme), there would be no encoding whatsoever of this category.

| (28) | base | – | tns | – | agr |

| /ìska/ | /x/ | /me/ | |||

| iskà | x | me | |||

| ‘want’ | pst | 1pl | |||

| aor |

To summarize, BG aorists are aspectually unspecified except for the—anyway ubiquitous—viewpoint-aspect category. In contrast, imperfects involve an additional aspectual specification (marked by /ě/) which does not assert that the past relevant situation ceased before the time of evaluation, as AT is an open interval (see Section 2.2).

All things considered, it is a reasonable conclusion that aorists encode that AT is a closed interval, i.e., that the situation denoted in the stem ceased before the time of evaluation (no current relevance). As aorists are morphologically unmarked, it is likely that the ‘closed perspective’ is the trivial default when speaking about past situations—as Klein (1994, p. 117) puts it: “It is just the nature of time. Things in the past are settled”. In other words, AT-intervals are closed by default when they are located in the past.33 The following observations provide further evidence for the claim (advocated by, e.g., Aronson, 1967; Maslov, 1959; Scatton, 1984; Sonnenhauser, 2006a) that the aorist is the unmarked member of the opposition.

- While the aorist is inherited from Late Proto-Indo-European, the imperfect is a Proto-Slavic innovation formed with the suffix -ěa-. Crucially, the suffix -x- was adopted from the aorist by analogy (see Bielfeldt, 1961, p. 281; Trunte, 2018, p. 43). In other words, the aorist was the basic past tense already in Proto-Slavic.

- It is imperfective aorists—not imperfects or perfects—which are used to express the so-called general-factual reading (see Sonnenhauser, 2006a, p. 141; Breu, 2003).

- While the imperfect past is an anaphoric tense requiring a referential anchor to hook up to in discourse, the aorist introduces such anchors (see, e.g., Becker, 2010; Becker & Egetenmeyer, 2018). Therefore, the aorist is the prototypical narrative tense in BG.

But aorist and imperfect stems are used not only to build past-tense forms, but also to derive participles to be used in the diverse perfect(oid) periphrases of BG.

3.5. Perfect(oid) Periphrases

BG has a wide range of periphrases based on participles formed with the suffix /l/ (“-l-participles”). But in addition to the ‘ordinary’ -l-participle available in all Slavic languages, BG has, as a rather recent innovation (see, e.g., Scatton, 1993, p. 215; Nicolova, 2017, p. 63), a second -l-participle based on the imperfect stem, which I refer to as the imperfect participle. By analogy with the opposition in the past tense, I refer to the ‘older’ -l-participle as the aorist participle.34 Table 11 give examples of the two.

Table 11.

Inflected forms of the aorist and imperfect participle of pìjna, ‘sip’.

The morphological formation of aorist participles parallels that of aorist past-tense forms, with the participial suffix /l/ taking the place of the past-tense marker /x/; see (29).

| (29) | base | – | asp | – | tns | – | agr |

| /pìjna/ | /l/ | /i/ | |||||

| pìjna | l | i | |||||

| ‘sip’ | (aor) | perf | pl |

Imperfect participles are formed in parallel to imperfect past-tense forms as they involve the same aspectual suffix /ě/; see (30).

| (30) | base | – | asp | – | tns | – | agr |

| /pìjna/ | /ě/ | /l/ | /i/ | ||||

| pìjna | e | l | i | ||||

| ‘sip’ | ipf | perf | pl |

While the respective past-tense forms are finite in the sense that they are specified for mood and tense (and person) and refer to real-world situations on their own, aorist and imperfect participles require the presence of the auxiliary săm, ‘be’.35 For instance, prescriptive grammars (starting at least as early as Andrejčin, 1944) state that the (present) perfect is built with an aorist participle and a present-tense form of săm, as shown in (31).36

| (31) | Postpil | săm | v | universitèta | na | 1.9.2000 g. |

| enter.pfv.ptcp.sg.m | be.prs.1sg | in | university.def | on | 1.9.2000 | |

| ‘I entered the university on 01.09.2000.’ (Nicolova, 2007, p. 419) | ||||||

However, perfect periphrases may also contain imperfect participles. An example is (32), dubbed the “perfect progressive” by Hauge (1999, p. 113). Hauge argues that speakers use this variant of the perfect in place of the imperfect past tense when they do not (wish to) vouch for the information conveyed.37

| (32) | Tuk | v | manastìra | e | ìmalo | učìlište, | v | koèto | vìnagi |

| here | in | monastery.def | be;prs.3sg | have.ipfv.ptcp.sg.n | school | in | which | always | |

| se | e govòrel | blgarski ezìk. | |||||||

| refl | be.3sg speak.ipfv.ipf.ptcp.sg.m | Bulgarian language | |||||||

| ‘Here in the monastery there has been a school where Bulgarian has always been spoken’. | |||||||||

| (Hauge, 1999, p. 113) | |||||||||

Much like the perfect, the pluperfect is formed with the aorist (or imperfect) participle plus an imperfect past-tense form of săm; see (33).38

| (33) | [À]rmijata | stoèše | bezpòmoštna, | sjàkaš | bè | pàdnala | v |

| army.def | stand.ipfv.ipf.3sg | helplessly | as if | be.ipf.3sg | fall.pfv.ptcp.sg.f | in | |

| plen. | |||||||

| captivity | |||||||

| ‘The army was standing still helpless as if it had been captured.’ | |||||||

| (Jordan Radičkov; cited from Nicolova, 2007, p. 430) | |||||||

Considering the fact that the morphological makeups of the participles have the same stems as the past-tense forms, it is reasonable to conclude that their semantics is the same, too. Therefore, I claim that aorist participles present the situation denoted in their verb stem as finished, whereas imperfect participles do not.

In (29) and (30), I have located the participial suffix /l/ in the tns-slot. Indeed, the contribution of /l/ is temporal, but unlike the past-tense suffix /x/, which encodes an absolute past tense (i.e., the assertion time lies before the time of evaluation), the /l/ denotes a relative tense. More precisely, it produces the perfect time span (PTS), as defined in (7) in Section 2.3. In a nutshell, this means that /l/ locates the original assertion-time interval (AT-1) in the pre-time of a newly introduced second assertion time (AT-2); see (34). The semantics of /l/ is thus not only temporal but also aspectual.

| (34) | - - - - - - [AT-1 - - - ][AT-2 - - - ] - - - - - - | (PTS) |

To arrive at an absolute tense interpretation, an auxiliary must be used to determine the relation between AT-2 and the time of evaluation. Thus, for instance, a present-tense auxiliary will give rise to a present perfect, while a past-tense auxiliary yields a pluperfect.

Now, recall that the /l/-suffix is added to the stem after the latter has been specified as either imperfect or aorist. This means that the semantic contribution of aorist and imperfect affects AT-1, whereupon /l/ introduces AT-2. In Section 2.2, I argued that imperfect /ě/ specifies AT as an open interval, while its absence (=aorist) means that it is a closed interval. When applied to the PTS, this means that an aorist participle denotes a situation finished within AT-1. The latter interval lies in the pre-time of AT-2, from where the speaker views it in a kind of retrospection. Due to the fact that AT-1 and AT-2 form the overall PTS interval, the finished past situation is somehow still relevant in the state that obtains in AT-2.

To represent the category of viewpoint aspect in (34), we have to add the situation time (ST)-interval, which is represented in (35) using curly brackets.39

| (35) | a. | - - - - - - {ST - [AT-1 - - - ][AT-2 - - - ] - - - - - - | (imperfective aspect) |

| b. | - - - - - - {ST - [AT-1 - - }][AT-2 - - - ] - - - - - - | (perfective aspect) |

The prototypical candidate to combine with a closed AT-1 interval (aorist) is the perfective aspect—see example (31)—as at least the right boundary of ST is included in AT-1, as depicted in (35b). This is why aorist participles, just like aorist past-tense forms, are mostly perfective. However, aorist participles may also be imperfective, as in (36).

| (36) | Ivàn | e | stroìl | pjàsǎčnǎ | kùla | i | predì. |

| I. | be.prs.3sg | build.ipfv.ptcp.sg.m | sand | tower | also | before | |

| ‘Ivan has built a sandcastle before as well.’ (Pancheva, 2003, p. 297) | |||||||

This may seem contradictory at first sight given the assumption that AT-1 must include at least one boundary of ST so as to count as a closed (or half-open) interval, while it must not, at the same time, include the culmination within ST so as to be imperfective. But this only appears to be a contradiction: The culmination not asserted by the imperfective aspect is an internal boundary, whereas AT-1 must contain at least one external (temporal) boundary to count as a closed interval. In other words, an imperfective aorist stem (both in the past tense and the perfect) does not, on the one hand, assert the culmination of the situation, but does, on the other hand, assert at least its right temporal boundary (cessation). Thus, utterance (36) means that Ivan has been engaged in building a sandcastle at some time before the time of utterance, but apparently stopped the process before its completion. The focus is on the fact that the activity of building, as such, took place. Moreover, (36) is a present perfect, so the past situation is somehow relevant for the state that holds at the moment of speaking. We might paraphrase this relevance by saying that Ivan is (by now) experienced in building sandcastles.

To schematize this state of affairs, I add to (35a) the moment of cessation “/”, which lies before the possible culmination (which I do not represent); see (37).40

| (37) | - - - - - - {ST - [AT-1 - - - / ][AT-2 - - - ] - - - - - - | (imperfective aorist participle) |

Next, if we alter the viewpoint aspect in (36) to perfective, we obtain (38).

| (38) | Ivàn | e | postroìl | pjàsǎčnǎ | kùla. |

| I. | be.prs.3sg | build.pfv.ptcp.sg.m | sand | tower | |

| ‘Ivan has built a sandcastle.’ | |||||

The perfective aspect asserts the culmination “•”, while all else remains the same. Thus, the building of the sandcastle is both completed and finished and somehow connected to the time of utterance; see schema (39).

| (39) | - - - - - - [AT-1 - {ST - - • / } - ][AT-2 - - - ] - - - - - - | (perfective aorist participle) |

Tilkov et al. (1983, p. 320) characterize this variant of the perfect “statal” because it is the target state which is focused. Nicolova (2017, p. 421) adds that the auxiliary can be dropped, as in (40), when the speaker perceives only the result of the activity (here, the existence of the sandcastle).

| (40) | Ivàn | postroìl | pjàsǎčnǎ | kùla. |

| I. | build.pfv.ptcp.sg.m | sand | tower | |

| ‘Ivan (has) built a sandcastle [I conclude].’ | ||||

In such a situation, Nicolova claims, the speaker can only conclude that it was Ivan who built the sandcastle, which is why she dubs this variant “perfect of conclusion”. Moreover, Nicolova argues that this variant is the origin of some of the alleged evidential moods (see note 35). If the existence of such moods is accepted, aorist participles are described as referring to (reported) past situations. Note that this has a straightforward explanation considering the time structure in (39): As AT-1 is a closed interval, the situation must have ceased in the past, so can by no means be running at the time of utterance.

The next combination is illustrated by (41): The participle is imperfective and imperfect.

| (41) | Ivàn | e | strojàl | pjàsǎčnǎ | kùla. |

| I. | be.prs.3sg | build.ipfv.ipf.ptcp.sg.m | sand | tower | |

| ‘Ivan was/has been building a sandcastle [I infer].’ | |||||

This is what Hauge (1999) calls the “perfect progressive” as it denotes relatively long-lasting activities or processes. Indeed, (41) adds the nuance that the building of the sandcastle took quite a while—and is possibly still running at the time of utterance. Tilkov et al. (1983, p. 320) and Nicolova (2017, p. 423) use the term “actional perfect”, which is to say that the action or process denoted in the participle is in the speaker’s focus, combined with its relevance for the present. Thus, while the imperfect excludes any temporal boundaries from the assertion, the imperfective aspect excludes any possible culmination. Schema (42) is therefore void of any boundaries whatsoever.

| (42) | - - - - - - {ST - [AT-1 - - - ][AT-2 - - - ] - - - - - - | (imperfective imperfect participle) |

Like in the case of (38), the auxiliary may be dropped, as shown in (43). Again, the effect is a distance between the speaker and the information conveyed (see note 35).

| (43) | Ivàn | strojàl | pjàsǎčnǎ | kùla. |

| I. | build.ipfv.ipf.ptcp.sg.m | sand | tower | |

| ‘Ivan (has) built/is building a sandcastle [they say].’ | ||||

As far as grammars classify this as a special evidential mood (‘narrative’), they add that the imperfect participle is ambiguous between two temporal readings: past or present. The time structure proposed here has the potential to explain this ambiguity in temporal reference: (42) shows that nothing excludes the possibility that the building of the sandcastle is still running at the time of utterance and that the speaker refers to this very activity. On the other hand, the speaker may as well focus on the past portion of the PTS, i.e., on an activity running at some past time (in AT-1). Put differently, the exclusion of the right temporal boundary thanks to the imperfect renders this variant temporally ambiguous.

Finally, an imperfect participle may also be perfective, as in (44).

| (44) | Kogàto | Ivàn | postrojàl | pjàsǎčnǎ | kùla, | … |

| when | I. | build.pfv.ipf.ptcp.sg.m | sand | tower | ||

| ‘Whenever Ivan built a sandcastle, …’ | ||||||

The same combination can be found in the past tense; see (45).41

| (45) | Štom | napìšeše | pismò, | tòj | ti | otgovàrjaše. |

| as soon as | write.pfv.ipf.3sg | letter | he | you.dat | answer.ipfv.ipf.3sg | |

| ‘As soon as you wrote the letter, he would answer you.’ | ||||||

| (Bertinetto & Delfitto, 2000, p. 215) | ||||||

Many authors observe that this combination occurs almost exclusively in adverbial clauses being part of complex sentences whose main-clause verb is an imperfective imperfect, and that its interpretation is iterative or habitual (e.g., Comrie, 1976; Gvozdanović, 2012; Maslov, 1959; Pašov, 1999; Rivero et al., 2017). In other words, perfective imperfects denote multiple instances of the same situation. In the model proposed here, this can be explained in terms of an interpretive adjustment: The contradictory combination of imperfect (open AT-interval, i.e., no ST-boundary inside AT) and perfective aspect (AT includes culmination and right boundary of ST) can be resolved if the utterance is taken to be about multiple instances of the same eventuality, each culminated (perfective aspect). These instances form a chain, and it is this chain which the utterance is about. Crucially, AT-1 covers only a portion of this chain, so is an open interval (imperfect). I schematize this in (46).42

| (46) | - - - {ST - • } - [AT-1 - {ST′ - • } - {ST″ - • } - {ST‴ - • } - ][AT-2 - - - ] - - - | |

| (perfective imperfect participle) | ||

The same holds for perfective imperfects in the past tense. However, these involve only one AT-interval in the pre-time of the time of evaluation, as depicted in (47).

| (47) | - - - - • } - - - • } - - • } - - • } - ] - - • } - - - ⬤ - - - | |

| (perfective imperfect past tense) | ||

4. Conclusions

Of the many aspecto-temporal categories in BG, the category of viewpoint aspect is the most basic one: It is ubiquitous (present in any verb form, be it finite or non-finite, prior to whatever further grammatical specifications) and relates the situation-time with the assertion-time interval, so makes it possible for the speaker to present to the addressee a specific portion of the situation denoted in the verb stem.

In the past tense (marked by the suffix /x/), a second aspectual category is available (and in fact mandatory), which allows the speaker to encode the distinction between finished (aorist) and unfinished (imperfect) situations. Of aorist and imperfect, the latter is marked both morphologically (suffix /ě/) and semantically (open AT-interval). Actually, the aorist lives up to its name (Ancient Greek aóristos, ‘undefined’) in that it represents the default interpretation of past situations (finished, i.e., closed AT-interval) and lacks additional aspectual marking. Thus, in a sense, it is the imperfect alone that constitutes the higher-order aspecto-temporal category I call temporal aspect.

However, ‘aorist’ and ‘imperfect’ are actually only the names of specific verb stems which are not, as such, restricted to the past-tense domain: They also occur in participles marked with the perfect suffix /l/. The perfect, too, is an aspecto-temporal category as it expresses a relative past by locating a newly introduced second AT-interval in the post-time of the original one. The relevant -l-participles occur in a range of perfect(oid) periphrases, a subset of which is traditionally classified, not as variants of the perfect, but as independent non-confirmative (evidential) moods. Of this subset, all those periphrases with imperfect participles give rise to either a past- or a present-tense interpretation. This, too, can be explained assuming that the imperfect encodes an open AT-interval, which allows for the possibility that the situation is still running at the time of evaluation (Pitsch, 2021).

Thus, speakers of BG have available a second set of verbal forms to refer to situations in the past or in the present, respectively. If they do not choose to utilize these forms in their basic perfect meaning, they may use them as non-confirmative alternatives to the synthetic past-tense forms, traditionally called aorist and imperfect. This allows BG speakers to vouch for the truth of the information conveyed in the sentence or to stay neutral as to this truth: While the ‘old’ synthetic past tenses are confirmative, the ‘younger’ perfect(oid) periphrases are not (see also Pitsch, 2020).

In the light of the fact that the imperfect option can be chosen both in the past and the perfect, a more adequate way of describing the facts is to say that, if speakers choose the imperfect, this implies the subsequent choice of either the past (/x/) or the perfect (/l/). On the other hand, if the speaker does not choose the imperfect, the past or perfect may be chosen but do not have to be. Only in the former choice gives rise to ‘aorists’.

To sum up, (48) represents the hierarchy of BG aspectual categories.

| (48) | verbal base] viewpoint aspect ] temporal aspect ] {past/perfect} ] |

In addition, Table 12 summarizes the semantic contributions of the three aspectual categories. It shows that the imperfective imperfect past tense marks no internal or external boundaries whatsoever, while perfective perfect periphrases mark all of them.

Table 12.

Semantic contribution of BG aspectual and aspecto-temporal categories.

I hope to have shown how BG utilizes the forms available to express a wide range of aspecto-temporal distinctions, unseen in the remaining members of the Slavic branch (even Macedonian). To formalize the relevant meanings, I made use of the interval-relational approach as well as of the distinction between closed and open intervals. None of these theoretical ingredients is new, but their joint application to explain and formalize all aspecto-temporal categories of BG has, to the best of my knowledge, not been attempted so far.

Quite a few words could be said as to the syntax underlying the categories discussed above, but this is beyond the scope and possibilities of the present paper. In principle, all the categories investigated here might be represented in syntax by individual functional projections, or they might be considered to be purely morphological and thus be utterly absent from syntax. Finally, an intermediate position would be to claim that only those aspectual values that are fully grammaticalized (regular) are also present in syntax (these are the imperfective aspect encoded by /va/, the imperfect encoded by /ě/, and the perfect encoded by /l/). I leave it for future research to address these intriguing questions, hopeful that the present contribution adds its part to the big picture.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in this study are included in the article. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Acknowledgments

Thanks are due to the organizers, participants, and audience of the workshop Aspectual Architecture of the Slavic Verb: Analogies in Different Languages and Other Grammatical Domains held at Leipzig University between the 6 and 8 November 2023. Moreover, I would like to express my sincere thanks to three anonymous reviewers for their valuable and insightful comments and suggestions. The paper has greatly benefited from their advice.

Conflicts of Interest

The author declares no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The glosses used in linguistic examples in this manuscript follow the Leipzig Glossing Rules (https://www.eva.mpg.de/lingua/pdf/Glossing-Rules.pdf (accessed on 14 April 2025)) except the following abbreviations:

| after | Is after |

| agr | Agreement |

| asp | Aspect |

| asuff | Aspectual suffix |

| AT | Assertion time (interval) |

| before | Is before |

| dsuff | Derivational suffix |

| incl | Is included in |

| ipf | Imperfect |

| isuff | Inflectional suffix |

| pref | Prefix |

| PTS | Perfect time span |

| ST | Situation time (interval) |

| tm | Thematic marker |

| tns | Tense |

| t* | Time of evaluation |

Notes

| 1 | Grave accents mark word stress. Variation in stress assignment is marked by two accents in the same word. Stress shift in prefixed verbs occurs in dialects only but is not accepted in standard pronunciation. |

| 2 | I disregard the special atelic class of points or semelfactives as distinguished by Moens and Steedman (1988) and Smith (1991), respectively. |

| 3 | See similar formalizations in Paslawska and von Stechow (2003, p. 7), Geist (2006, pp. 99–100), Becker (2010, p. 84), Mueller-Reichau (2013, p. 200), and Zimmermann (2013, p. 221). If a telic situation (namely its preparatory phase) is presented as ongoing at the assertion time (i.e., the time about which the speaker makes their utterance), its culmination cannot take place at the same time. This is the reason why perfective present-tense verbs are excluded from independent clauses. They can only be used in subordinate clauses whose temporal interpretation depends on the matrix. Here, perfective forms have future reference. |

| 4 | The exact extension of the AT-interval can only be established by temporal adverbials in the clause, the wider context, or world knowledge. What is crucial is that AT includes the culmination point as it marks that the inception of the (target) state. |

| 5 | “Some verbs are aspectually deficient. These are primarily imperfective verbs denoting actions that cannot, due to the lexical meaning of the verb, be presented as (being) synthetic, i.e., as (being) an indivisible whole”. (Tilkov et al., 1983, p. 259; translation H.P.) By contrast, aspectually deficient perfective verbs are rare. Examples are posăvètvam ‘give a piece of advice’, zamìlvam ‘start caressing’ (Tilkov et al., 1983, p. 259). |

| 6 | Sonnenhauser refers to, e.g., Desclés and Guenchéva (1990); Guenchéva (1989). |

| 7 | Sonnenhauser (2006a) employs half-open intervals to explain the perfect (right-open) and pluperfect (left-open) readings of the perfective aspect in Russian. In BG, the latter two require a more complex analysis that involves a second AT-interval (see Section 2.3. On the other hand, cessation minimally demands that the AT-interval be closed on the right edge, while it may well be open on the left edge if the speaker is not particularly interested in the beginning of the preparatory phase. |

| 8 | An example for this is (32) below. |

| 9 | An example for this is (25) below. |

| 10 | Rivero et al. (2017) propose an impf operator for BG which they claim is the result of grammaticalization of ‘big’ situations. In Sonnenhauser’s (2006a) model, the latter are situations viewed without their temporal boundaries. |

| 11 | From here on, I use a less fine-grained way of representing intervals because the internal structure of situations is of minor relevance. |

| 12 | An anonymous reviewer notes that AT is in the post-time of ST only in case of the perfect of current relevance (resultative perfect) but not necessarily in case of the existential (experiential) and universal perfect. Iatridou et al. (2001) account for this by claiming that the two relevant intervals merge into one overall interval, the Perfect Time Span (see (7) below). |

| 13 | This also means that the perfect-operator turns the information if the target state is reached or not from the realm of assertion into that of presupposition. I thank Olav Mueller-Reichau for bringing this to my attention. |

| 14 | Iatridou et al.’s proposal refines McCoard’s (1978) Extended Now, which says that the perfect provides an interval whose right boundary is the reference time (time of evaluation/utterance) and which stretches leftwards into the past up to some contextually or adverbially specified boundary. See von Stechow (1999) with regard to the German perfect. |

| 15 | Počìtala, which belongs to conjugational class III, is ambiguous between aorist and imperfect (see Section 3.1). |

| 16 | The base is either a verbal root or a derived verbal stem. |

| 17 | Where the present perfect combines an -l-participle (see Section 3.5) with the present-tense auxiliary sǎm ‘be’ (e.g., sǎm na/pìsala ‘(I) have written’), the pluperfect combines it with the same auxiliary in the imperfect past tense (e.g., bjàx na/pìsala ‘(I) had written’). On the other hand, the future consists of the future particle šte plus a present-tense form (e.g., šte na/pìšǎ ‘(I) will write’), just like the future perfect consists of the same particle combined with the present perfect (e.g., šte sǎm na/pìsala ‘(I) will have written’). Finally, the past future and past future perfect combine the imperfect past-tense of štǎ ‘want’ with the present tense (e.g., štjǎx da na/pìšǎ ‘(I) would write’) and the present perfect (e.g., štjǎx da sǎm na/pìsala ‘(I) would have written’), respectively. |

| 18 | The 1sg and 3pl in classes I and II do not show the relevant vowel at the surface. I adopt Nicolova’s (2017, p. 383) view that this is because “the thematic vowel merges with the inflection”. |

| 19 | There is no consent that verbs like napìša are synonymous with their simplex base. Some authors claim that the prefix does add semantic content, but that the latter amounts to little more than telicization. Regarding (16a), this means that na- introduces a local path leading to a goal (the written product). |

| 20 | Besides -va-, secondary imperfectives exhibit -ava-, -uva-, or just -a-. Of these, only -va- and -ava- are productive (see Manova, 2007, p. 33). |

| 21 | The idea of aspectual “triads” can already be found in Maslov (1982, 1984). However, as an anonymous reviewer points out, it is a much-debated issue in BG linguistics whether basic imperfectives and prefixed perfectives form an aspectual pair, the prevailing opinion being that an aspectual pair should exclude the basic imperfective. |

| 22 | Recently, Klimek-Jankowska and Simeonova (2025) put forward a more fine-grained analysis that takes into account the distinction between lexical and purely perfectivizing prefixes. The authors conclude that BG has two homonymous secondary-imperfective morphemes and thus explain why secondary imperfectivization in BG—unlike in other Slavic languages—applies nearly without restrictions. |

| 23 | The transcriptions -ă and -ăt for the 1sg and 3pl, respectively, in classes I and II diverge from BG orthography (which uses -a and -at) to reflect their actual pronunciation. |

| 24 | The class-I.2 stem /pìjna/ ‘sip’ is a derived semelfactive based on the root /pij/ ‘drink’. Its semelfactive semantics is contributed by the suffix -n- which occupies the dsuff-slot in Manova’s template in (13) above. Below in (21b), I the derived stem /pìjna/ is treated like a base. |

| 25 | The second line gives the single underlying stem and affixes in phonemic transcription, while the third line shows the surface realization as resulting from the application of phonological rules (see below). |

| 26 | Only stressed /à/ ‘survives’ before /e/ as, for instance, in (22c) igràe ‘(s/he) plays’. |

| 27 | A diachronic explanation for the unavailability of the slot is that the stem-final /a/ of class-III verbs emerged from the contraction of the original sound sequence -aje- into -ā- which later lost its length. The vowel -e- in the original sequence was the same thematic vowel as in modern conjugational class I, so the contraction fused it–and with it the asp-slot–with the verb stem. |

| 28 | Aronson (1967, p. 85) doubts that the BG present tense is tightly associated with continuativity (i.e., openness of AT). He refers to the historical present where present-tense forms are used in place of the aorist past tense. However, the historical present is a transposition, i.e., a use of the present tense in a context sharply contradicting its basic meaning. It is likely that the violation of its openness-feature is just as intended. |

| 29 | While the former holds true for Bosnian-Croatian-Montenegrin-Serbian (BCMS), Macedonian, and Sorbian, too, the latter does not: While aorist forms are nearly always perfective, imperfect forms are necessarily imperfective in these languages. Moreover, in BCMS, the imperfect past tense is virtually obsolete. |

| 30 | Prescriptively, aorist forms of classes I.2, I.4, II.3, and III have their word stress on the stem, whereas stress on the ending is considered colloquial or dialectal (e.g., in napisàhme which occurs in Western dialects). Crucially, however, in class III (which contains all secondary imperfectives), word stress on the ending discriminates aorist from imperfect forms which would otherwise be completely homonymous. |

| 31 | Roughly, /ě/ surfaces as -e- when unstressed (e.g., /pìjnaěx/ →pìjnex ‘(I) sipped’) and as -jà- when stressed (/četěx/ → četjàx ‘(I) read’). Both allomorphs are reflexes of Proto-Slavic *ě (jat’). |

| 32 | The status of -o- and -e- as mere fill-in vowels is corroborated by the fact that they cannot bear stress. I take it that fill-in vowels are phonology-based stem extensions. Put differently, they are invisible on the morphological level. |

| 33 | By contrast, the intervals are open by default in the present. As noted above, Nicolova (2017, p. 375) argues that to be open for AT is non-distinctive in the present tense in the absence of a closed counterpart. |

| 34 | At least from a cross-Slavic and diachronic perspective, aorist participles are not associated with anything to be dubbed ‘aorist’. The name used in BG grammar reflects the opposition to the imperfect. The stem of aorist participles is actually the ‘infinitive stem’ which equals, according to the one-stem approach, the single underlying stem. |

| 35 | The auxiliary may be absent, which triggers non-confirmative readings (see, e.g., Friedman, 2001; Pitsch, 2020; Sonnenhauser, 2012). There is debate about whether auxiliary-less structures are variants of the perfect (indicative) or special ‘evidential’ moods (‘narrative’, ‘mirative’, etc.). The former view is advocated by, e.g., Chvany (1988); Fici (2005); Fielder (1995, 1999, 2000); Friedman (2004); Levin-Steinmann (2004); Sonnenhauser (2012, 2015). Roughly, these authors argue that auxiliary drop (iconically) reflects distance between the speaker and the content of their message. I share their view. |

| 36 | I gloss aorist participles with ptcp only since their formation involves nothing but the participial suffix /l/. |

| 37 | This is close, though not identical, to what other authors claim, namely, that the relevant periphrasis constitutes a special ‘conclusive’ mood by which speakers mark the information as their conjecture or inference from available facts (e.g., Tilkov et al. 1983, p. 324). A reviewer points out that the imperfect participle is believed to have emerged in connection with the category of evidentiality in BG to express evidential present and imperfect, and that the perfect is formed only with the aorist participle. The reviewer believes that instances of the perfect containing imperfect participles are due to a general trend in BG towards mixing of the aorist and the imperfect (see, e.g., Fetvadžieva, 2018), the use of the imperfect instead of the aorist participle being an attempt to ‘reinforce’ the imperfective semantics – and that this is the case also in (32). While I see the logic behind connecting evidentiality and the emergence of the imperfect participle in BG, I believe that the latter may well also be due to the persistence of the aorist/imperfect distinction in BG, and that the resulting rich paradigm of -l-periphrases may have been the ideal means for expressing non-confirmativity. So, (32) is maybe a ‘true’ perfect (progressive) and a non-confirmative imperfect at the same time. |

| 38 | Aorist and imperfect participles occur in further periphrases (future perfect, past future perfect), each involving specific auxiliaries or auxiliary forms. In addition, many grammars list several ‘evidential’ mood periphrases based on -l-participles. I do not address these forms in detail but propose a possible general source of the relevant interpretations below. |

| 39 | See the discussion concerning example (9) as to the missing right boundary of the ST-interval in (35a). |

| 40 | I take it that, although the speaker asserts that the building of the sandcastle was interrupted, it may well be resumed (and culminate in a complete castle) at some time thereafter. |

| 41 | The difference between perfect -l-forms like (44) and past-tense forms like (45) concerns confirmativity: While the past tense is confirmative (the speaker vouches for the truth of the information), the perfect -l-form is not (the speaker stays neutral; see, e.g., Hauge 1999; Pitsch 2020). If evidential moods are accepted, (44) is classified as ‘narrative’ (the speaker marks that their message as second-hand information). Crucially, the non-confirmative interpretation of utterances like (41), (43), or (44) is not necessarily inscribed in the semantics of these constructions. It may as well arise as a consequence of not choosing their markedly confirmative alternatives. |

| 42 | The chain of instances may well continue in and after AT-2, which allows a non-confirmative (evidential) present-tense reading. Irrespective of whether the reading is present- or past-tense, it will always be non-confirmative if the verb is an imperfect participle. |

References

- Andrejčin, L. D. (1938). Kategorie znaczeniowe konjugacji bułgarskiej [Prace Komisji Językowej 26]. Nakładem Polskiej Akademii Umiejętności. [Google Scholar]

- Andrejčin, L. D. (1944). Osnovna bǎlgarska gramatika. Chemus. [Google Scholar]

- Andrejčin, L. D. (1976). Kǎm morfologičnata charakteristika na vidovata sistema v sǎvremennija bǎlgarski ezik. In P. Pašov, & R. Nicolova (Eds.), Pomagalo po bǎlgarska morfologija (pp. 129–133). Nauka i Izkustvo. [Google Scholar]

- Andrejčin, L. D. (1978). Osnovna bǎlgarska gramatika. Nauka i Izskustvo. [Google Scholar]

- Andrejčin, L. D., Popov, K., & Stojanov, S. (1977). Gramatika na bǎlgarskija ezik. Nauka i Izskustvo. [Google Scholar]