Quantifying Experience with Accented Speech to Study Monolingual and Bilingual School-Aged Children’s Speech Processing

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Why Does Variability Matter?

3. Quantifying Experience with Languages and Accents

3.1. Quantifying Language Experience

3.2. Continuous Measures of Language Experience

3.3. Measuring Accent Experience

4. Directions for Future Research

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

| Study | Variety | Method(s) | Age (N) | Exposure | Key Result(s) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| (Buac, 2019) (Exp. 1) | Spanish- and Korean-accented English | Word learning (eye-tracking) | 4–5 yo (50) | Ordinal 5-point scale from ‘no experience’ to ‘daily home exposure’ | Experience with an L2 accent enhances learning from a speaker with the same accent but not from a speaker with a different L2 accent. |

| (Buac, 2019) (Exp. 2–3) | Spanish- and Korean-accented English | Word learning (eye-tracking) | 4–5 yo (95) | Length of bilingualism (child’s age minus age of acquisition), number of non-native speakers interacting with the child, strength of L2 accent in English | A high amount of Spanish accent experience reduces word learning from American English native speakers; a higher number of L2-accented speakers is associated with lower American English language skills. |

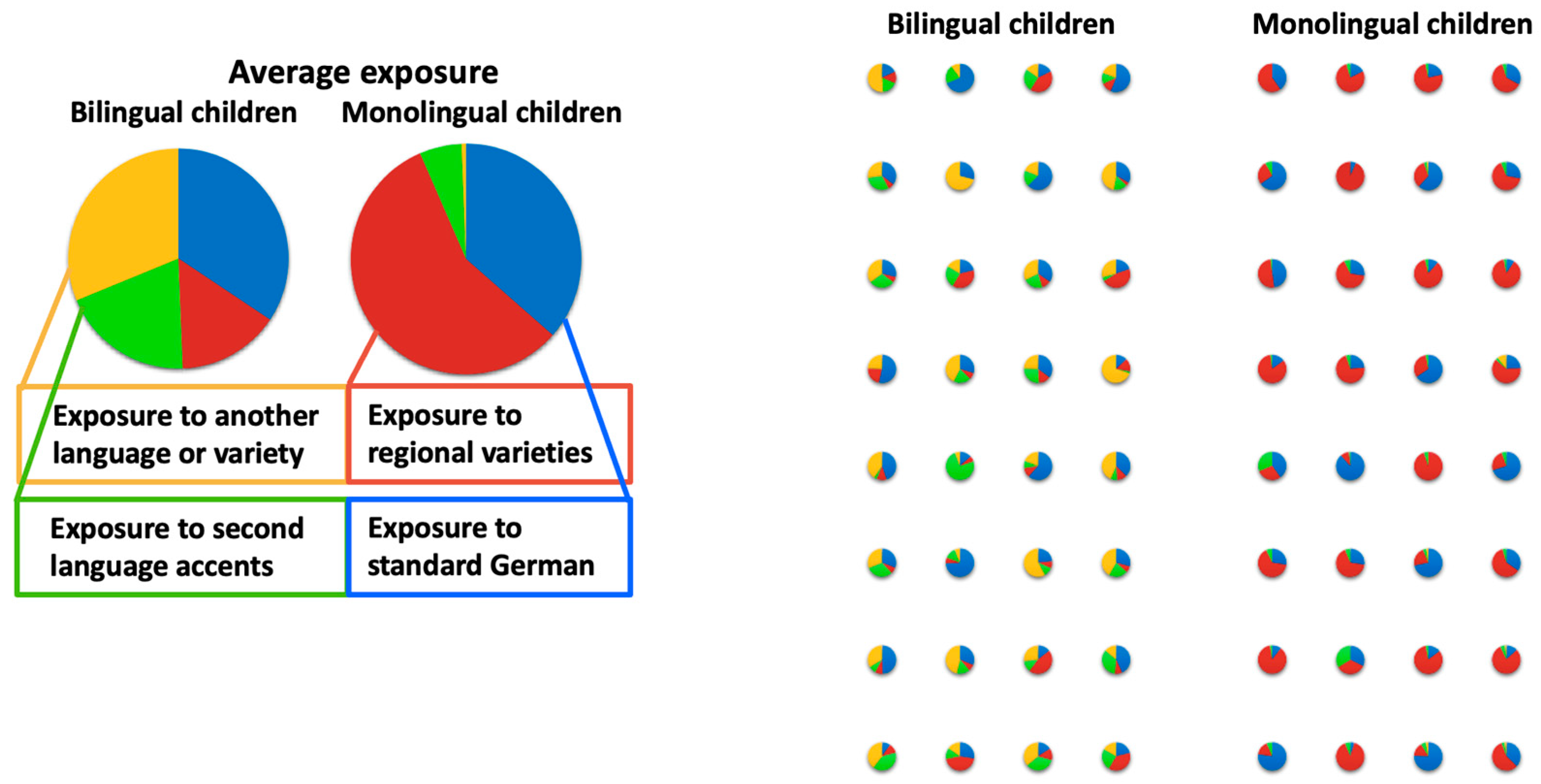

| (Levy et al., 2019) | Standard German, second-language- and regional-accented German | Speech intelligibility (sentence repetition) | 8–11 yo (33 monolinguals, 27 bilinguals) | Number of hours per week a child spends with Standard German, languages other than German, regional and L2 accents of German; information provided by parents and school-personnel for diverse activities and interactions at home, at school, during leisure time activities, and with media. | More experience with regional accents improved sentence repetition performance in the regional and in the standard accent. More experience with L2 accents did not help in either accent condition. |

| (Levy & Hanulíková, 2019) | Standard German L2- and regional-accented German | Vowel production (picture naming) | 8–11 yo (33 monolinguals, 27 bilinguals) | As in (Levy et al., 2019) | Increased exposure to input variability leads to greater variability in vowel production (measured by Euclidean distances). Bilinguals did not show greater variability compared to monolinguals, but there were some differences in F1 formant values. |

| (Levy & Hanulíková, 2023) | Standard German, L2- and regional-accented German | Word learning (spot-it-paradigm) | 7–11 yo (43 monolinguals, 45 bilinguals) | As in (Levy et al., 2019) | Successful word learning was predicted by the amount of input in regional and L2 accents but not by exposure to other languages (i.e., by bilingualism). |

| (Poarch et al., 2019) | Standard German and Swabian German | Executive function (Flanker & Simon tasks) | Adults (34) | Daily language usage with family, friends, at work/university, collapsed into one (%) variable, used together with proficiency measurements to create a Swabian dominance score * | Balanced bidialectals perform worse on two executive function tasks than Swabian-dominant bidialectals. |

| (Porretta et al., 2016) | Chinese-accented English | Cross-modal priming (visual world paradigm) | Adults (96) | Number of weekly interactions with non-native speakers of English on a scale from 0 (Never) to 10 (Daily), converted to a proportion by dividing by 10, multiplied by the percentage of those interactions including speakers with a Chinese accent (range = 0–100) | Accent experience leads to higher activation strength and improves the time course of word recognition in accented speech. |

| (Porretta & Tucker, 2019) | Chinese-accented English | Pupil dilation | Adults (85) | As in (Porretta et al., 2016) | Accent experience reduces processing effort. |

| (Porretta et al., 2020) | Chinese-accented English | Predictive processing (visual world paradigm) | Adults (60) | Participant estimation of their total experience interacting with speakers with a Chinese accent as a percentage of their lifetime interactions (range = 0–30) | Accent experience leads to an advantage in predictive processing in accented speech. |

| 1 | For 21.4% German is not the family language. The number of families in which another language than German is used as the dominant language at home differs depending on the geographical location and on the migration generation of the different members of the household (Rundfunk Berlin Brandenburg, 2020). |

References

- Auer, P. (2011). Dialect vs. standard: A typology of scenarios in Europe. In B. Kortmann, & J. Van der Auwera (Eds.), The languages and linguistics of Europe: A comprehensive guide (pp. 485–500). De Gruyter. [Google Scholar]

- Baker, W., & Trofimovich, P. (2005). Interaction of native-and second-language vowel system (s) in early and late bilinguals. Language and Speech, 48(1), 1–27. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Barcroft, J., & Sommers, M. S. (2005). Effects of acoustic variability on second language vocabulary learning. Studies in Second Language Acquisition, 27(3), 387–414. [Google Scholar]

- Barcroft, J., & Sommers, M. S. (2014). Effects of variability in fundamental frequency on L2 vocabulary learning: A comparison between learners who do and do not speak a tone language. Studies in Second Language Acquisition, 36(3), 423–449. [Google Scholar]

- Baum, S., & Titone, D. (2014). Moving toward a neuroplasticity view of bilingualism, executive control, and aging. Applied Psycholinguistics, 35(5), 857–894. [Google Scholar]

- Bedore, L. M., Peña, E. D., Summers, C. L., Boerger, K. M., Resendiz, M. D., Greene, K., Bohman, T., & Gillam, R. B. (2012). The measure matters: Language dominance profiles across measures in Spanish–English bilingual children. Bilingualism: Language and Cognition, 15(3), 616–629. [Google Scholar]

- Bent, T. (2018). Development of unfamiliar accent comprehension continues through adolescence. Journal of Child Language, 45, 1400–1411. [Google Scholar]

- Bent, T., Holt, R. F., Van Engen, K. J., Jamsek, I. A., Arzbecker, L. J., Liang, L., & Brown, E. (2021). How pronunciation distance impacts word recognition in children and adults. The Journal of the Acoustical Society of America, 150, 4103–4117. [Google Scholar]

- Bialystok, E. (2001). Bilingualism in development: Language, literacy, and cognition. Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Bialystok, E., & Feng, X. (2009). Language proficiency and executive control in proactive interference: Evidence from monolingual and bilingual children and adults. Brain and Language, 109(2–3), 93–100. [Google Scholar]

- Bialystok, E., Luk, G., Peets, K. F., & Yang, S. (2010). Receptive vocabulary differences in monolingual and bilingual children. Bilingualism: Language and Cognition, 13(4), 525–531. [Google Scholar]

- Birdsong, D. (2005). Interpreting age effects in second language acquisition. In J. Kroll, & A. de Groot (Eds.), Handbook of bilingualism (pp. 109–127). Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Blom, E. (2010). Effects of input on the early grammatical development of bilingual children. International Journal of Bilingualism, 14(4), 422–446. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blumenfeld, H. K., & Marian, V. (2007). Constraints on parallel activation in bilingual spoken language processing: Examining proficiency and lexical status using eye-tracking. Language and Cognitive Processes, 22(5), 633–660. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bodén, P. (2011). Adolescents’ pronunciation in multilingual Malmö, Gothenburg and Stockholm. In R. Källström, & I. Lindberg (Eds.), Göteborgsstudier I Nordisk Språkvetenskap 14 (pp. 35–48). Department of Swedish Language, University of Gothenburg. [Google Scholar]

- Bosch, L., & Ramon-Casas, M. (2011). Variability in vowel production by bilingual speakers: Can input properties hinder the early stabilization of contrastive categories? Journal of Phonetics, 39(4), 514–526. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bradlow, A., & Bent, T. (2008). Perceptual adaptation to non-native speech. Cognition, 106(2), 707–729. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Braun, B., Czeke, N., Rimpler, J., Zinn, C., Probst, J., Goldlücke, B., Kretschmer, J., & Zahner-Ritter, K. (2021). Remote testing of the familiar word effect with non-dialectal and dialectal German-learning 1–2-year-olds. Frontiers in Psychology, 12, 714363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brekelmans, G., Lavan, N., Saito, H., Clayards, M., & Wonnacott, E. (2022). Does high variability training improve the learning of non-native phoneme contrasts over low variability training? A replication. Journal of Memory and Language, 126, 104352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buac, M. (2019). Learning by monolingual and bilingual children: The role of non-native input [Doctoral dissertation, University of Wisconsin-Madison]. Retrieved from ProQuest Dissertations Publishing (13902725). [Google Scholar]

- Buac, M., Gross, M., & Kaushanskaya, M. (2016). Predictors of processing-based task performance in bilingual and monolingual children. Journal of Communication Disorders, 62, 12–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bürki, A., Ernestus, M., & Frauenfelder, U. H. (2010). Is there only one “fenêtre” in the production lexicon? On-line evidence on the nature of phonological representations of pronunciation variants for French schwa words. Journal of Memory and Language, 62(4), 421–437. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Casillas, M., & Cristia, A. (2019). A step-by-step guide to collecting and analyzing long-format speech environment (lfse) recordings. Collabra: Psychology, 5(1), 24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cattani, A., Abbot-Smith, K., Farag, R., Krott, A., Arreckx, F., Dennis, I., & Floccia, C. (2014). How much exposure to English is necessary for a bilingual toddler to perform like a monolingual peer in language tests? International Journal of Language & Communication Disorders, 49(6), 649–671. [Google Scholar]

- Chambers, J. K. (2002). Dynamics of dialect convergence. Journal of Sociolinguistics, 6(1), 117–130. [Google Scholar]

- Cheung, S., Kan, P. F., Winicour, E., & Yang, J. (2019). Effects of home language input on the vocabulary knowledge of sequential bilingual children. Bilingualism: Language and Cognition, 22(5), 986–1004. [Google Scholar]

- Clopper, C. G. (2014). Sound change in the individual: Effects of exposure on cross-dialect speech processing. Laboratory Phonology, 5(1), 69–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coco, M. I., Smith, G., Spelorzi, R., & Garraffa, M. (2025). Moving to continuous classifications of bilingualism through machine learning trained on language production. Bilingualism: Language and Cognition, 28, 248–256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cohen, C. (2016). Relating input factors and dual language proficiency in French–English bilingual children. International Journal of Bilingual Education and Bilingualism, 19(3), 296–313. [Google Scholar]

- Core, C. (2020). Effects of nonnative input on language abilities in Spanish-English bilinguals. Child Bilingualism and Second Language Learning: Multidisciplinary Perspectives, 10, 87. [Google Scholar]

- Cutler, A. (2012). Native listening: Language experience and the recognition of spoken words. MIT Press. [Google Scholar]

- Darcy, I., & Krüger, F. (2012). Vowel perception and production in Turkish children acquiring L2 German. Journal of Phonetics, 40, 568–581. [Google Scholar]

- DeAnda, S., Poulin-Dubois, D., Zesiger, P., & Friend, M. (2016). Lexical processing and organization in bilingual first language acquisition: Guiding future research. Psychological Bulletin, 142(6), 655–667. [Google Scholar]

- De Bree, E., Verhagen, J., Kerkhoff, A., Doedens, W., & Unsworth, S. (2017). Language learning from inconsistent input: Bilingual and monolingual toddlers compared. Infant and Child Development, 26(4), 1–15. [Google Scholar]

- De Bruin, A. (2019). Not all bilinguals are the same: A call for more detailed assessments and descriptions of bilingual experiences. Behavioral Sciences, 9(3), 33. [Google Scholar]

- De Cat, C. (2020). Predicting language proficiency in bilingual children. Studies in Second Language Acquisition, 42(2), 279–325. [Google Scholar]

- De Houwer, A. (2021). Bilingual development in childhood. University Press. [Google Scholar]

- DeLuca, V., Rothman, J., Bialystok, E., & Pliatsikas, C. (2020). Duration and extent of bilingual experience modulate neurocognitive outcomes. NeuroImage, 204, 116222. [Google Scholar]

- Deutsches Jugendinstitut e.V., D., Lochner, S., & Jähnert, A. (2020). DJI-Kinder-und Jugendmigrationsreport 2020: Datenanalyse zur Situation junger Menschen in Deutschland. wbv Media. Available online: https://www.dji.de/fileadmin/user_upload/dasdji/news/2020/DJI_Migrationsreport_2020.pdf (accessed on 12 June 2024).

- Dong, J. (2018). Language and identity construction of China’s rural-urban migrant children: An ethnographic study in an urban public school. Journal of Language, Identity & Education, 17(5), 336–349. [Google Scholar]

- Durrant, S. (2014). The influence of long-term exposure to dialect variation on representation specificity and word learning in toddlers [Doctoral dissertation, University of Plymouth]. Pearl. Available online: https://pearl.plymouth.ac.uk (accessed on 20 January 2024).

- Engel, A., & Hanulíková, A. (2020). Speaking style modulates morphosyntactic expectations in young and older adults: Evidence from a sentence repetition task. Discourse Processes, 57(9), 749–769. [Google Scholar]

- Evans, B. G., & Lourido, G. T. (2019). Effects of language background on the development of sociolinguistic awareness: The perception of accent variation in monolingual and multilingual 5-to 7-year-old children. Phonetica, 76(2–3), 142–162. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Fiedler, S., Keller, C., & Hanulíková, A. (2019, August 5–9). Social expectations and intelligibility of Arabic-accented speech in noise. International Congress of Phonetic Sciences (pp. 3085–3089), Melbourne, Australia. [Google Scholar]

- Flege, J. E. (2009). Give input a chance! In T. Piske, & M. Young-Scholten (Eds.), Input matters in SLA (pp. 175–190). Multilingual Matters. [Google Scholar]

- Flege, J. E., Frieda, E. M., & Nozawa, T. (1997). Amount of native-language (L1) use affects the pronunciation of an L2. Journal of Phonetics, 25(2), 169–186. [Google Scholar]

- Flege, J. E., & Wayland, R. (2019). The role of input in native Spanish Late learners’ production and perception of English phonetic segments. Journal of Second Language Studies, 2(1), 1–44. [Google Scholar]

- Flege, J. E., Yeni-Komshian, G. H., & Liu, S. (1999). Age constraints on second-language acquisition. Journal of Memory and Language, 41(1), 78–104. [Google Scholar]

- Floccia, C., Delle Luche, C., Durrant, S., Butler, J., & Goslin, J. (2012). Parent or community: Where do 20-month-olds exposed to two accents acquire their representation of words? Cognition, 124(1), 95–100. [Google Scholar]

- Francot, R. J., Van den Heuij, K., Blom, E., Heeringa, W., & Cornips, L. (2017). Inter-individual variation among young children growing up in a bidialectal community: The acquisition of dialect and standard Dutch vocabulary. In Language variation–European perspectives VI (pp. 85–98). John Benjamins Publishing Company. [Google Scholar]

- Frank, M. C., Braginsky, M., Yurovsky, D., & Marchman, V. A. (2021). Variability and consistency in early language learning: The Wordbank project. MIT Press. [Google Scholar]

- Gertken, L. M., Amengual, M., & Birdsong, D. (2014). Assessing language dominance with the bilingual language profile. In P. Leclercq, A. Edmonds, & H. Hilton (Eds.), Measuring L2 proficiency: Perspectives from SLA (pp. 208–225). Multilingual Matters. [Google Scholar]

- Gildersleeve-Neumann, C. E., Kester, E. S., Davis, B. L., & Peña, E. D. (2008). English speech sound development in preschool-aged children from bilingual English–Spanish environments. Language, Speech, and Hearing Services in Schools, 39(3), 314–328. [Google Scholar]

- Grosjean, F. (2010). Bilingual: Life and reality. Harvard University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Gullifer, J. W., Kousaie, S., Gilbert, A. C., Grant, A., Giroud, N., Coulter, K., Klein, D., Baum, S., Phillips, N., & Titone, D. (2021). Bilingual language experience as a multidimensional spectrum: Associations with objective and subjective language proficiency. Applied Psycholinguistics, 42(2), 245–278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gullifer, J. W., & Titone, D. (2019). The impact of a momentary language switch on bilingual reading: Intense at the switch but merciful downstream for L2 but not L1 readers. Journal of Experimental Psychology: Learning, Memory, and Cognition, 45(11), 2036. [Google Scholar]

- Gutiérrez-Clellen, V. F., & Kreiter, J. (2003). Understanding child bilingual acquisition using parent and teacher reports. Applied Psycholinguistics, 24(2), 267–288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hanulíková, A. (2019). Bewertung und Grammatikalität regionaler Syntax. Eine empirische Untersuchung zur Rolle der SprecherInnen und HörerInnen [Evaluation and grammaticality of regional syntax. An empirical study of the role of speakers and listeners]. Linguistik Online 98, 197–218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hanulíková, A. (2021). Do faces speak volumes? Social expectations in speech comprehension and evaluation across three age groups. PLoS ONE, 16, e0259230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hanulíková, A. (2023, August 7–11). Learning phonotactically complex L3 words: Are bilinguals more successful? 20th International Congress of Phonetic Sciences (ICPhS) (pp. 2701–2705), Prague, Czech Republic. [Google Scholar]

- Hanulíková, A. (2024). Navigating accent bias in German: Children’s social preferences for a second-language accent over a first-language regional accent. Frontiers of Language Sciences, 3, 1357682. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hanulíková, A., & Ekström, J. (2017, August 20–24). Lexical adaptation to a novel accent in German: A comparison between German, Swedish, and Finnish listeners. Proceedings of Interspeech 2017 (pp. 1784–1788), Stockholm, Sweden. [Google Scholar]

- Hanulíková, A., van Alphen, P. M., van Goch, M. M., & Weber, A. (2012). When one person’s mistake is another’s standard usage: The effect of foreign accent on syntactic processing. Journal of Cognitive Neuroscience, 24(4), 878–887. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hanulíková, A., & Weber, A. (2012). Sink positive: Linguistic experience with th substitutions influences nonnative word recognition. Attention, Perception, & Psychophysics, 74(3), 613–629. [Google Scholar]

- Hoff, E., & Shanks, K. F. (2020). The quality of child-directed speech depends on the speaker’s language proficiency. Journal of Child Language, 47(1), 132–145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jeffries, E. (2016). Children’s developing awareness of regional accents: A socioperceptual investigation of pre-school and primary school children in York [Doctoral dissertation, University of York]. Whiterose eTheses. Available online: https://etheses.whiterose.ac.uk/13966/ (accessed on 10 December 2023).

- Johnson, E. K., & White, K. S. (2020). Developmental sociolinguistics: Children’s acquisition of language variation. WIREs Cognitive Science, 11, e1515. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johnson, J. S., & Newport, E. L. (1989). Critical period effects in second language learning: The influence of maturational state on the acquisition of English as a second language. Cognitive Psychology, 21(1), 60–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaushanskaya, M., Gross, M., & Buac, M. (2014). Effects of classroom bilingualism on task-shifting, verbal memory, and word learning in children. Developmental Science, 17(4), 564–583. [Google Scholar]

- Khattab, G. (2007). Variation in vowel production by English-Arabic bilinguals. In J. Cole, & J. Hualde (Eds.), Laboratory phonology 9 (pp. 383–410). Mouton de Gruyter. [Google Scholar]

- Kidd, E., Donnelly, S., & Christiansen, M. H. (2018). Individual differences in language acquisition and processing. Trends in Cognitive Sciences, 22, 154–169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- König, W., Pfeiffer, C., & Maitz, P. (2020). Regional Dialect in Kindergarten: The results of a questionnaire survey in Bavaria-Swabia. Zeitschrift für Dialektologie und Linguistik, 86(3), 247–283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kroll, J. F., & Bialystok, E. (2013). Understanding the consequences of bilingualism for language processing and cognition. Journal of Cognitive Psychology, 25(5), 497–514. [Google Scholar]

- Lee, S. A. S., & Iverson, G. K. (2012). Vowel category formation in Korean–English bilingual children. Journal of Speech, Language, and Hearing Research, 55(5), 1449–1462. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee-James, R., & Washington, J. A. (2018). Language skills of bidialectal and bilingual children. Topics in Language Disorders, 38(1), 5–26. [Google Scholar]

- Lehtonen, M., Soveri, A., Laine, A., Järvenpää, J., De Bruin, A., & Antfolk, J. (2018). Is bilingualism associated with enhanced executive functioning in adults? A meta-analytic review. Psychological Bulletin, 144(4), 394. [Google Scholar]

- Leung, A. H. C. (2012). Bad influence?—An investigation into the purported negative influence of foreign domestic helpers on children’s second language English acquisition. Journal of Multilingual and Multicultural Development, 33(2), 133–148. [Google Scholar]

- Lev-Ari, S. (2018). The influence of social network size on speech perception. Quarterly Journal of Experimental Psychology, 71(2), 133–148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Levy, H., & Hanulíková, A. (2019). Variation in children’s vowel production: Effects of language exposure and lexical frequency. Journal of Laboratory Phonology, 10, 9. [Google Scholar]

- Levy, H., & Hanulíková, A. (2022). Language input effects on children’s words and vowels: An accent categorization and rating study. Language Sciences, 89, 101447. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Levy, H., & Hanulíková, A. (2023). Spot it and learn it! Word learning in virtual peer-group interactions using a novel paradigm for school-aged children. Language Learning, 73, 197–230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Levy, H., Konieczny, L., & Hanulíková, A. (2019). Processing of unfamiliar accents in monolingual and bilingual children: Effects of type and amount of accent experience. Journal of Child Language, 46, 368–392. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lloyd-Smith, A., Einfeldt, M., & Kupisch, T. (2020). Italian-German bilinguals: The effects of heritage language use on accent in early-acquired languages. International Journal of Bilingualism, 24(2), 289–304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marecka, M., Wrembel, M., Otwinowska-Kasztelanic, A., & Zembrzuski, D. (2015). Do early bilinguals speak differently than their monolingual peers? Predictors of phonological performance of Polish-English bilingual children. In E. Babatsouli, & D. Ingram (Eds.), Proceedings of the international symposium on monolingual and bilingual speech 2015 (pp. 207–213). Institute of Monolingual and Bilingual Speech. [Google Scholar]

- Marian, V., Blumenfeld, H. K., & Kaushanskaya, M. (2007). The Language Experience and Proficiency Questionnaire (LEAP-Q): Assessing language profiles in bilinguals and multilinguals. Journal of Speech Language and Hearing Research, 50, 940–967. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Marian, V., & Hayakawa, S. (2021). Measuring bilingualism: The quest for a “bilingualism quotient”. Applied Psycholinguistics, 42(2), 527–548. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McCarthy, K. M., & Evans, B. (2019). The perception of familiar and unfamiliar accents by bilingual and monolingual children. In S. Calhoun, P. Escudero, M. Tabain, & P. Warren (Eds.), Proceedings of the international congress of phonetic sciences (pp. 2203–2207). International Phonetic Association. [Google Scholar]

- McCarthy, K. M., Mahon, M., Rosen, S., & Evans, B. G. (2014). Speech perception and production by sequential bilingual children: A longitudinal study of voice onset time acquisition. Child Development, 85(5), 1965–1980. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McDonald, M., Gross, M., Buac, M., Batko, M., & Kaushanskaya, M. (2018). Processing and comprehension of accented speech by monolingual and bilingual children. Language Learning and Development, 14(2), 113–129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McQueen, J. M. (2005). Speech perception. In K. Lamberts, & R. Goldstone (Eds.), The handbook of cognition (pp. 255–275). Sage Publications. [Google Scholar]

- Menjivar, J., & Akhtar, N. (2017). Language experience and preschoolers’ foreign word learning. Bilingualism: Language and Cognition, 20(3), 642–648. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muench, K. (2011). Word learning under accent variability in monolinguals and bilinguals. 2010–2011. [Unpublished Honors Project Language Acquisition and Sound Recognition]. Department of Cognitive Science, University of California. [Google Scholar]

- Mulík, S., Amengual, M., Maldonado, R., & Carrasco-Ortíz, H. (2021). Hablantes de herencia: ¿una noción aplicable para los indígenas de México? Estudios de Lingüística Aplicada, 73, 7–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paradis, J., Emmerzael, K., & Duncan, T. S. (2010). Assessment of English language learners: Using parent report on first language development. Journal of Communication Disorders, 43(6), 474–497. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pearson, B. Z. (2007). Social factors in childhood bilingualism in the United States. Applied Psycholinguistics, 28(3), 399–410. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perry, L. K., Samuelson, L. K., Malloy, L. M., & Schiffer, R. N. (2010). Learn locally, think globally: Exemplar variability supports higher-order generalization and word learning. Psychological Science, 21(12), 1894–1902. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Piske, T., MacKay, I. R., & Flege, J. E. (2001). Factors affecting degree of foreign accent in an L2: A review. Journal of Phonetics, 29(2), 191–215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Place, S., & Hoff, E. (2016). Effects and noneffects of input in bilingual environments on dual language skills in 2 1⁄2-year-olds. Bilingualism: Language and Cognition, 19(5), 1023–1041. [Google Scholar]

- Poarch, G. J., Vanhove, J., & Berthele, R. (2019). The effect of bidialectalism on executive function. International Journal of Bilingualism, 23(2), 612–628. [Google Scholar]

- Porretta, V., Buchanan, L., & Järvikivi, J. (2020). When processing costs impact predictive processing: The case of foreign-accented speech and accent experience. Attention, Perception, & Psychophysics, 82, 1558–1565. [Google Scholar]

- Porretta, V., & Tucker, B. (2019). Eyes wide open: Pupillary response to a foreign accent varying in intelligibility. Frontiers in Communication, 4, 8. [Google Scholar]

- Porretta, V., Tucker, B., & Järvikivi, J. (2016). The influence of gradient foreign accentedness and listener experience on word recognition. Journal of Phonetics, 58, 1–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramon-Casas, M., Cortés, S., Benet, A., Conxita, L. L. E. Ó., & Bosch, L. (2023). Connecting perception and production in early Catalan–Spanish bilingual children: Language dominance and quality of input effects. Journal of Child Language, 50(1), 155–176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raviv, L., Lupyan, G., & Green, S. C. (2022). How variability shapes learning and generalization. Trends in Cognitive Science, 26(6), 462–483. [Google Scholar]

- Ribot, K. M., Hoff, E., & Burridge, A. (2018). Language use contributes to expressive language growth: Evidence from bilingual children. Child Development, 89(3), 929–940. [Google Scholar]

- Ross, J., & Melinger, A. (2017). Bilingual advantage, bidialectal advantage or neither? Comparing performance across three tests of executive function in middle childhood. Developmental Science, 20(4), 1–21. [Google Scholar]

- Rost, G. C., & Murray, B. (2010). Finding the signal by adding noise: The role of noncontrastive phonetic variability in early word learning. Infancy, 15(6), 608–635. [Google Scholar]

- Rundfunk Berlin Brandenburg. (2020). Mehrsprachigkeit ist ein wertvolles Gut. Available online: https://www.rbb24.de/politik/beitrag/2020/09/erziehung-kinder-kita-zweisprachig-aufwachsen-interview.html (accessed on 12 June 2022).

- Rydland, V., & Grøver, V. (2021). Language use, home literacy environment, and demography: Predicting vocabulary skills among diverse young dual language learners in Norway. Journal of Child Language, 48(4), 717–736. [Google Scholar]

- Sadakata, M., & McQueen, J. M. (2013). High stimulus variability in nonnative speech learning supports formation of abstract categories: Evidence from Japanese geminates. The Journal of the Acoustical Society of America, 134(2), 1324–1335. [Google Scholar]

- Satyanath, S. (2015). Language variation and change. In Globalising sociolinguistics: Challenging and expanding theory (pp. 107–122). Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Singh, L., Fu, C. S., Tay, Z. W., & Golinkoff, R. M. (2018). Novel word learning in bilingual and monolingual infants: Evidence for a bilingual advantage. Child Development, 89(3), e183–e198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Skoruppa, K. (2019). Novel noun and verb learning in mono-and multilingual children. Travaux Neuchâtelois de Linguistique, 71, 109–123. [Google Scholar]

- Soto-Corominas, A., Daskalaki, E., Paradis, J., Winters-Difani, M., & Al Janaideh, R. (2022). Sources of variation at the onset of bilingualism: The differential effect of input factors, AOA, and cognitive skills on HL Arabic and L2 English systax. Journal of Child Language, 49, 741–773. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Staubhaar, T. (2018, September 5). Auch zu Hause muss deutsch gesprochen werden. Welt. Online Newspaper Commentary. Available online: https://www.welt.de/wirtschaft/article181429532/Integration-Auch-zu-Hause-muss-deutsch-gesprochen-werden.html (accessed on 13 January 2024).

- Sulpizio, S., Del Maschio, N., Del Mauro, G., Fedeli, D., & Abutalebi, J. (2020). Bilingualism as a gradient measure modulates functional connectivity of language and control networks. NeuroImage, 205, 1–11. [Google Scholar]

- Sumner, M. (2011). The role of variation in the perception of accented speech. Cognition, 119(1), 131–136. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Sumner, M., & Samuel, A. G. (2009). The effect of experience on the perception and representation of dialect variants. Journal of Memory and Language, 60(4), 487–501. [Google Scholar]

- Surrain, S., & Luk, G. (2019). Describing bilinguals: A systematic review of labels and descriptions used in the literature between 2005–2015. Bilingualism: Language and Cognition, 22(2), 401–441. [Google Scholar]

- Tagliamonte, S. A., & Molfenter, S. (2007). How’d you get that accent? Acquiring a second dialect of the same language. Language in Society, 36(5), 649–675. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tuller, L. (2015). Clinical use of parental questionnaires in multilingual contexts. In S. Armon-Lotem, J. De Jong, & N. Meir (Eds.), Assessing multilingual children: Disentangling bilingualism from language impairment (Vol. 13, pp. 301–330). Multilingual Matters. [Google Scholar]

- Unsworth, S. (2016). Early child L2 acquisition: Age or input effects? Neither, or both? Journal of Child Language, 43(5), 649–675. [Google Scholar]

- Unsworth, S., Brouwer, S., de Bree, E., & Verhagen, J. (2019). Predicting bilingual preschoolers’ patterns of language development: Degree of non-native input matters. Applied Psycholinguistics, 40(5), 1189–1219. [Google Scholar]

- Uzal, M., Peltonen, T., Huotilainen, M., & Aaltonen, O. (2015). Degree of perceived accent in Finnish as a second language for Turkish children born in Finland. Language Learning, 65(3), 477–503. [Google Scholar]

- Van Engen, K. J., & Peelle, J. E. (2014). Listening effort and accented speech. Frontiers in Human Neuroscience, 8, 577. [Google Scholar]

- Van Hell, J. G., & Poarch, G. J. (2014). How much bilingual experience is needed to affect executive control? Applied Psycholinguistics, 35(5), 925–928. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Heugten, M., & Johnson, E. K. (2014). Learning to contend with accents in infancy: Benefits of brief speaker exposure. Journal of Experimental Psychology: General, 143(1), 340. [Google Scholar]

- Weatherhead, D., Friedman, O., & White, K. S. (2019). Preschoolers are sensitive to accent distance. Journal of Child Language, 46, 1058–1072. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Yow, W. Q., & Li, X. (2015). Balanced bilingualism and early age of second language acquisition as the underlying mechanisms of a bilingual executive control advantage: Why variations in bilingual experiences matter. Frontiers in Psychology, 6, 164. [Google Scholar]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Hanulíková, A.; Levy, H. Quantifying Experience with Accented Speech to Study Monolingual and Bilingual School-Aged Children’s Speech Processing. Languages 2025, 10, 80. https://doi.org/10.3390/languages10040080

Hanulíková A, Levy H. Quantifying Experience with Accented Speech to Study Monolingual and Bilingual School-Aged Children’s Speech Processing. Languages. 2025; 10(4):80. https://doi.org/10.3390/languages10040080

Chicago/Turabian StyleHanulíková, Adriana, and Helena Levy. 2025. "Quantifying Experience with Accented Speech to Study Monolingual and Bilingual School-Aged Children’s Speech Processing" Languages 10, no. 4: 80. https://doi.org/10.3390/languages10040080

APA StyleHanulíková, A., & Levy, H. (2025). Quantifying Experience with Accented Speech to Study Monolingual and Bilingual School-Aged Children’s Speech Processing. Languages, 10(4), 80. https://doi.org/10.3390/languages10040080