Abstract

This study investigates the cross-linguistic priming effect in the syntactic written output of late bilingual Levantine Arabic speakers who learn English as a second language. In particular, we examined priming sentence type (simple vs. complex sentences) and priming language condition (Levantine Arabic vs. English). Forty-nine bilinguals (Mean age = 33.3, SD = 8.5), who learned Levantine Arabic as their L1 and English as their L2, were primed with a short paragraph presented on the computer screen in either English or Levantine Arabic and asked to produce a written response in the counterpart language. Logistic regression analysis revealed a significant cross-linguistic priming effect, suggesting that the syntactic structure of the prime in the participants’ first language (Levantine Arabic) predicts the participants’ written output in the second language (English), and the reverse is also true. However, there was no significant effect of priming sentence type (simple vs. complex) on the likelihood of producing primed res ponses, indicating that both priming conditions yielded similar levels of priming. In contrast, there was a significant effect of the priming language condition, with participants significantly more likely to produce syntactically primed responses when the priming language was Arabic compared to English. In addition, there was a significant interaction between the priming language condition and priming sentence type: Arabic priming led to more simple sentence production in English, whereas English priming did not significantly affect sentence complexity in Arabic. These findings align with the shared syntax account but highlight the need to consider factors such as language dominance in bilingual syntactic processing.

1. Introduction

This study aims to investigate if syntactic representations are shared across late bilinguals’ Arabic (L1) and English (L2) using a cross-linguistic priming task. Syntactic priming, a foundational concept in language production research, refers to the tendency for individuals to reproduce recently encountered sentence structures, often in response to exposure within the same language (Pickering & Ferreira, 2008). For example, after hearing a sentence in a subject–verb–object (SVO) structure, speakers are more likely to use an SVO structure in their own subsequent speech or writing. Cross-linguistic syntactic priming extends syntactic priming across languages, examining whether exposure to a structure in one language (e.g., Arabic) influences the production of a similar structure in another language (e.g., English) (Hartsuiker et al., 2004; Tooley & Traxler, 2010). Cross-linguistic syntactic priming, thus, enables researchers to investigate whether bilinguals share syntactic representations across their languages, providing insights into underlying cognitive mechanisms that may facilitate syntactic processing across languages.

A central question in this investigation is whether the syntactic representations are stored separately or shared across languages (Hartsuiker et al., 2016; Weber & Indefrey, 2009). The separate syntax account proposes that bilinguals maintain distinct syntactic systems for each language, leading to limited or no cross-linguistic priming effects, as syntactic structures are language-specific (e.g., Hartsuiker et al., 2004; Schoonbaert et al., 2007). Conversely, the shared syntax account posits that bilinguals share syntactic structures across languages, as evidenced by cross-linguistic priming effects in several syntactic structures such as word order, dative constructions, and relative clauses (Hartsuiker et al., 2004; Schoonbaert et al., 2007). This account suggests that exposure to certain syntactic patterns in one language can facilitate the use of analogous structures in another language, reflecting underlying shared representations.

Nevertheless, two specific methodological issues remain unresolved. One issue is that many studies examined bilinguals who learn two Indo-European languages (e.g., English and Spanish) that share some typological similarities (Tooley & Traxler, 2010). Typological similarity may allow bilinguals to rely on shared syntactic structures, thereby enhancing priming effects by making certain syntactic constructions more accessible across languages. Examining cross-linguistic priming in typologically distant languages, such as Arabic and English, allows us to probe whether priming effects occur without shared syntax, thereby suggesting a possible role for cognitive mechanisms beyond language-specific transfer. Theoretically, such cognitive mechanisms may include working memory to handle differing syntactic rules (Hartsuiker et al., 2004), cognitive control to inhibit interference from the non-target language (Green, 1998), and pattern generalization to abstract syntactic structures across typological boundaries (Hartsuiker & Bernolet, 2017). Investigating cross-linguistic influence in typologically diverse language pairs is crucial for understanding cognitive mechanisms in bilinguals.

Another issue is that the majority of cross-linguistic priming research has investigated spoken language (Hartsuiker et al., 2004). Relatively few studies have examined whether the cross-linguistic priming effect is evident in written language (Favier et al., 2019). The two modalities of language differ in cognitive and motor processes such as working memory demands, which might affect the priming outcomes (Niedo et al., 2014; Kim et al., 2020). The extent to which the syntactic representations are shared between bilinguals’ two languages in the written form is unsettled. Building on the literature on cross-linguistic priming, the current study intends to address these unresolved issues. This investigation particularly examined the effect of the primed structure’s sentence complexity (complexity vs. simplicity) on written responses in Arabic-English speakers. The two languages have considerably different orthographic conventions, typological features, and phylogenetic origins. The results could provide critical insight into the cross-linguistic interaction between a learner’s L1 and L2 syntactic representations and potentially contribute to our understanding of second-language acquisition and pedagogy.

2. Cross-Linguistic Syntactic Priming

Two primary theories—activation-based accounts and implicit learning mechanisms—offer insight into the cognitive processes underlying syntactic priming. Theorists of activation-based accounts proposed that exposure to a sentence activates the mental representation of its syntax, leading to more accessibility for subsequent processing (Pickering & Garrod, 2004; Pickering & Ferreira, 2008; Hartsuiker et al., 2004). In activation-based computational models, syntactic processing involves activating lexical nodes (representing nouns or verbs) and combinatorial nodes (representing the combination of lexical items). Syntactic priming is driven by the reactivation of syntactic structures in memory, facilitating their reuse in subsequent production (Hartsuiker et al., 2004; Schoonbaert et al., 2007; Hartsuiker & Westenberg, 2000). This theory underscores memory reactivation as a key cognitive mechanism in syntactic priming. On the other hand, the error-based implicit learning theory suggests that syntactic priming results from adjustments in syntactic expectations driven by prediction errors (Chang et al., 2006), leading to durable changes in syntactic preferences. It is important to note that the mechanisms under both models may operate simultaneously, with activation-based processes accounting for immediate priming, and implicit learning solidifying these effects over time. Together, these theories explain both short-term and lasting priming effects, offering a comprehensive framework for understanding how syntactic structures might be activated, maintained, and reinforced across languages among bilinguals.

3. The Syntactic-Complexity Priming Paradigm in Written Modality

The current study utilized a syntactic-complexity priming paradigm to examine whether the structure of primed sentences—specifically complex versus simple sentences—affects an individual’s subsequent cross-linguistic written output. A simple sentence is defined as a sentence with one independent clause; it contains a subject and a predicate and expresses a complete thought. For example, “He goes for a walk” is considered a simple sentence. Here, “He goes for a walk” is the main clause with a subject “he” and a predicate “goes for a walk” (Zhou, 2020). Semantically speaking, the purpose of this simple sentence is to convey a simple idea as indicated by the finite verb “goes” and the doer of the action “he”. This type of sentence is contrasted with complex sentences that include one independent clause and at least one dependent clause, such as the Arabic complex sentence “إذا بدك تجي, خبرني”. [ʔiðə baddak tɪd͡ʒi, xabbirni], which means “If you want to come, let me know”. This is equivalent to the English complex sentence “If you want to come, let me know”, where “If you want to come” is a dependent clause and “let me know” is the independent clause. The mastery of such sentence types can reflect the level of syntactic proficiency in both native and second languages, particularly in bilinguals. Prior research has indicated that sentence complexity can significantly impact linguistic processing and production, with complex sentences requiring more cognitive resources than simple sentences (Vogelzang et al., 2020). This distinction has motivated our study to explore how priming with either sentence type influences cross-linguistic syntactic choices in bilinguals.

One unique aspect in the current study is the use of written language in the syntactic priming paradigm. Specifically, the participant is asked to read a short paragraph in one language (e.g., Arabic) before they type a short paragraph on another topic in the other language (e.g., English). It is important to note that the cognitive processes involved in the prime (reading) and the target output (writing in the digit format) are different from the processes involved in experiments that use spoken language. For the priming component in the experiment, reading processes in Arabic and in English are involved. According to the simple view of reading framework (Gough & Tunmer, 1986), reading a written text involves (1) the ability to decode printed words and (2) the skills of using language comprehension processes to make sense of the text. The ability to decode involves complex cognitive language skills such as working memory, attention, phonological awareness, morphological awareness, vocabulary, grammatical knowledge, and comprehension monitoring (Apel, 2022). In terms of the target output in the priming experiment in this study, participants are required to type a paragraph in either Arabic or English on the computer (Perkins & Salomon, 1988). The not-so-simple-view of writing suggests that writing performance is influenced by an individual’s spoken language skills, lower-level skills such as spelling/handwriting, and higher-level processes. These higher-level processes include planning (e.g., organizing ideas), self-regulation (e.g., monitoring progress), and general cognitive skills like attention and working memory. Central to these are executive functions, which encompass the ability to manage and coordinate these cognitive processes to achieve writing goals (Berninger & Winn, 2006; Hayes & Berninger, 2014). In the current study, the complex cognitive skills involved in reading (e.g., Arabic) and writing (e.g., English) during the cross-linguistic priming task would provide insights into the syntactic representation of bilinguals’ two languages (Marian et al., 2007).

In contrast to previous cross-linguistic priming studies, which focused on syntax at the sentence level (Arai, 2012; Chen, 2023), the current study investigates syntactic complexity at the paragraph level (approximately 10 sentences). Previous research suggests that paragraph-level tasks require more cognitive resources than sentence-level tasks, as they involve greater demands on working memory and thematic planning (Kellogg et al., 2007; Juffs & Harrington, 2011; Hayes, 2012). Paragraph-level tasks also require the simultaneous integration of multiple factors, such as content (e.g., story coherence, point of view), structure (e.g., writing system, grammar, orthography), and motor skills (e.g., typing using different keyboard layouts). Because the task in this study is carried out in the written modality, participants are allowed more time delay between stimulus and response (Oberauer, 2019). In this study, a critical distinction is drawn between the priming language conditions (Arabic and English), recognizing their unique contributions to bilingual language processing. This distinction is essential for a comprehensive understanding of how bilinguals navigate between different linguistic systems and the written modality. Language modalities, specifically written and spoken forms, offer distinct cognitive and linguistic landscapes. Written language, characterized by its permanence and structure, allows for more complex and deliberate syntactic constructions. In contrast, spoken language, marked by its immediacy and fluidity, often exhibits more colloquial and spontaneous linguistic patterns (Olson, 1994; Tannen, 1982). This study examines how the complexity of the written sentence at the paragraph level influences, if any, bilinguals’ language production and syntactic choices. In addition to sentence complexity, the study examines the impact of the priming language condition, here, Arabic and English, as typologically distinct languages, on the syntactic output of the participant.

4. Levantine Arabic Syntax

The theoretical framework of this study incorporates the complexities of syntactic structures in bilingual contexts. Levantine Arabic (LA) and Modern Standard Arabic (MSA) predominantly follow a verb–subject–object (VSO) order, contrasting with English’s subject–verb–object (SVO) pattern (Aoun et al., 2010; Benmamoun, 2017; Mohammad, 2000). This divergence in syntactic order between Arabic and English provides a unique landscape for examining cross-linguistic syntactic priming. The flexibility in word order in Levantine Arabic, attributed to nominative and accusative case marking, offers an additional layer of complexity compared to the more rigid syntactic structure of English (Aoun et al., 2010; Benmamoun, 2017). This flexibility in word order and the presence of zero-copula constructions in Levantine Arabic not only enriches its syntactic structure but also presents a unique challenge for syntactic processing in bilingual contexts (Aoun et al., 2010; Benmamoun, 2017). The zero-copula construction, which involves the omission of the copula verb, is typologically dissimilar to English, which consistently uses copula verbs. This disparity requires bilinguals to manage and switch between different syntactic frameworks, complicating cross-linguistic syntactic priming and processing. Therefore, understanding how these syntactic features interact in bilingual contexts is crucial for studying syntactic priming across typologically different languages (Aoun et al., 2010; Benmamoun, 2017). Furthermore, although simple sentences in Levantine Arabic like “ إجا ركض” [ʔɪʤa rakdˤ], which means “he came running” are parallel to those in English, Levantine Arabic simple sentences can traditionally be broken down into four types:

- Nominal Sentences: These consist of a subject and a predicate but do not include a verb. For example, “السماء صافية” [as-samaa’ safiya], which means “the sky is clear”.

- Verbal Sentences (Intransitive): These start with a verb followed by the subject, but no object. For example, “ذهب محمد إلى المدرسة” [dhahaba muhamad ila al-madrasah], which means “Muhammad went to school”.

- Verbal Sentences (Transitive): These must show one finite verb along with a direct object. For example, “كتب الطالب الدرس” [kataba atˤ -tˤalib ad-dars], which means “the student wrote the lesson”.

- Equational or Non-verbal Sentences: These express a state of being and do not necessarily include a verb. For example, “هو طبيب” [huwa tˤabiib], which means “he is a doctor”.

For the purposes of this study, only those types of simple sentences that contain one finite verb and have equivalents in English were considered for priming. This includes verbal sentences of both types: transitive and intransitive.

Historically and linguistically speaking, Levantine Arabic (LA) is a variety of Arabic spoken in the Levant—the area comprising Syria, Lebanon, Southeastern Turkey, Jordan, Palestine, and Israel (Mohammad, 2000). With around 30 million speakers worldwide, it is regarded today as one of the five main varieties of modern spoken Arabic (Versteegh, 2001). Levantine Arabic is made distinct from other varieties by a particular common marker, namely the use of the b-prefix at the beginning of present tense verbs. This consonantal addition has eliminated the standard vowels that denote the present tense (for both the plural and the singular) in some other varieties of Arabic. Levantine Arabic also retains a high degree of mutual intelligibility with other neighboring varieties and with standard dialects, particularly Modern Standard Arabic (MSA) and Classical Arabic (CA).

Unlike English, which has SVO word order, both the standard varieties and LA are VSO languages (Mohammad, 2000), though some scholars admittedly contend that it has a much more flexible word order (Aoun et al., 2010; Benmamoun, 2017). Setting these dissenting views aside, this would mean that the unmarked syntactical order of Levantine Arabic—as well as MSA and CA—in a simple sentence is: verb (V), subject (S), and object (O).

| Example 1: | ||||

| تَعَلَّمَ خَالِدٌ اللُّغَةَ العَرَبِيَّةَ بِسُرْعَةٍ | ||||

| [bɪsurʕah | ʔal-ʕarabijjah | ʔal-luɣah | Χaalɪd | taʕlam] |

| ǫᴜɪᴄᴋʟʏ | ᴀʀᴀʙɪᴄ | ʟᴀɴɢᴜᴀɢᴇ + ᴀᴄᴄ | ᴋʜᴀʟɪᴅ + ɴᴏᴍ | ʟᴇᴀʀɴ-ᴘᴀsᴛ |

| ᴀᴅᴠᴇʀʙ | ᴀᴅᴊᴇᴄᴛɪᴠᴇ | ᴏʙᴊᴇᴄᴛ | sᴜʙᴊᴇᴄᴛ | vᴇʀʙ.ᴘst |

| Khalid learnt Arabic quickly. | ||||

However, this is not the only difference between the two languages; while English has a strict syntactic structure, Levantine Arabic allows for freer word order, due to nominative and accusative case marking (Aoun et al., 2010; Benmamoun, 2017).

| Example 2: | ||||

| خَالِدٌ تَعَلَّمَ اللُّغَةَ العَرَبِيَّةَ بِسُرْعَةٍ | ||||

| [bɪsurʕah | ʔal-ʕarabijjah | ʔal-luɣah | taʕlam | Χaalɪd] |

| ǫᴜɪᴄᴋʟʏ | ᴀʀᴀʙɪᴄ | ʟᴀɴɢᴜᴀɢᴇ + ᴀᴄᴄ | ʟᴇᴀʀɴ-ᴘᴀsᴛ | ᴋʜᴀʟɪᴅ + ɴᴏᴍ |

| ᴀᴅᴠᴇʀʙ | ᴀᴅᴊᴇᴄᴛɪᴠᴇ | ᴏʙᴊᴇᴄᴛ | vᴇʀʙ.ᴘst | sᴜʙᴊᴇᴄᴛ |

| Khalid learnt Arabic quickly. | ||||

It should be noted here, however, that the use of the bi-prefix in present tense verbs in Levantine Arabic, as seen in the example “bi-taʕlam” (“he is learning”), is a distinguishing feature from other Arabic varieties. This prefix marks the present tense and exemplifies the morphosyntactic diversity within the Arabic language continuum. The presence of the bi-prefix can influence syntactic priming by providing additional morphological cues that help in the processing and production of syntactic structures. Understanding these syntactic nuances provides deeper insight into the cognitive processes involved in bilingual language processing and syntactic priming (Aoun et al., 2010; Versteegh, 2001).

| Example 3: | |||

| بتَعَلَّمَ خَالِدٌ اللُّغَةَ العَرَبِيَّةَ | |||

| [ʔal-ʕarabijjah | ʔal-luɣah | Χaalɪd | bitaʕlam] |

| ᴀʀᴀʙɪᴄ | ʟᴀɴɢᴜᴀɢᴇ + ᴀᴄᴄ | ᴋʜᴀʟɪᴅ + ɴᴏᴍ | ʟᴇᴀʀɴ.ᴘʀᴇs |

| ᴀᴅᴊᴇᴄᴛɪᴠᴇ | ᴏʙᴊᴇᴄᴛ | sᴜʙᴊᴇᴄᴛ | vᴇʀʙ.ᴘʀᴇs |

| Khalid is learning Arabic. | |||

A peculiarity of Levantine Arabic syntax is the traditionally called ‘nominal’ or ‘equative’ sentence, which uses a zero-copula construction. This is a type of predicative sentence that lacks a verb altogether and is—at least on the surface—just made up of two noun phrases, or NPs.

| Example 4: | |||

| إسحاق طالب ذكي | |||

| [ʔɪsħaːq | tˤˤaːlib | ðəkɪː] | |

| ɪsᴀᴀc + ɴᴏᴍ | sᴛᴜᴅᴇɴᴛ + ɴᴏᴍ | cʟᴇᴠᴇʀ + ɴᴏᴍ | |

| sᴜʙᴊᴇᴄᴛ | ᴘʀᴇᴅɪᴄᴀᴛᴇ | ᴀᴅᴊᴇᴄᴛɪᴠᴇ | |

| Isaac is a clever student. | |||

5. The Current Study

The purpose of this study is to investigate whether prior exposure to written sentences’ syntactic structures in a bilingual speaker’s L1 affects their written output in their L2 and vice versa through a written cross-linguistic priming paradigm. This study seeks to answer two main questions:

- Is there any priming effect of a speaker’s L1 syntactic written input on their L2 syntactic written output and vice versa? In other words, are bilinguals more likely to write simple sentences in their L2 when they are previously exposed to simple sentences in their L1 and vice versa? Symmetrically, are bilinguals more likely to write complex sentences in their L2 when they are previously exposed to complex sentences in their L1 and vice versa?

- Is there any effect of the priming language on the syntactic output? That is, are there any differences in the syntactic output between the syntactic priming from Arabic to English and the syntactic priming from English to Arabic?

In this study, we define bilingual individuals as those who actively and functionally use two languages in their daily lives, as described by Grosjean (2012). This delineation of bilingualism underscores the dynamic nature of language acquisition and usage, reflecting the complexity of navigating between languages with varying syntactic rules and structures. Our particular focus is on individuals who have acquired Levantine Arabic as their first language (L1) and subsequently acquired English as their second language (L2) at a later stage in life.

In accordance with shared syntax frameworks (Hartsuiker et al., 2004), this study hypothesizes that the syntactic structure of priming stimuli to which late bilinguals are exposed will be manifested in their cross-linguistic outcome (Fleischer et al., 2012; Lam & Sheng, 2016; Luo et al., 2014; Salamoura & Williams, 2007). That is, English and Arabic might use shared syntactic structures and, hence, activating a syntactic stimulus structure in one language will lead to activating the same syntactic structure in the target language (Elman, 1995; Fleischer et al., 2012; Son, 2020). However, if Arabic and English operate on the separate syntax account, then activating the syntactic structure of the priming language will not activate the syntactic structure of the target language. Consequently, the production of simple and complex sentences in the output would occur randomly, without a discernible pattern based on the syntactic structure of the priming stimuli. In addition to the previous hypothesis, our study also hypothesizes that the syntactic structure of the L2 learners’ output may depend on their language proficiency in each language. If L2 learners’ L1 is their stronger language, it is likely L1 might be more comprehensible than L2; that is, while their L1 syntactic structure may be an asset to their L2 syntactic structure, their L2 may not aid them in producing more syntactic structures in L1 in alignment with the L2 priming structure. Therefore, the hypothesis posits that the influence of priming language condition (Arabic vs. English) on syntactic choices in the written output will vary based on the bilingual’s language proficiency. Specifically, it anticipates that priming with the stronger language (L1) will lead to more pronounced cross-linguistic syntactic alignment than priming with the weaker language (L2), reflecting the differential impact of language dominance on syntactic priming effects (Hartsuiker & Bernolet, 2017).

6. Methods

The current study was approved by the institutional review board at the University of Colorado in accordance with the ethical standards of human subject research.

6.1. Participants

After obtaining the IRB approval from the University of Colorado, the recruitment process started on 9 July 2021 and ended on 31 December 2021. Participants were recruited from four different geographical locations: Colorado (US), Jeddah (Saudi Arabia), California (US), and Amman (Jordan) by word of mouth and by a virtual flyer posted on social media. These participants were born in Jordan, but they moved to Jeddah (Saudi Arabia) for school, work, or other business opportunities. Informed written consent was obtained from each participant prior to the start of the study. A total of 183 late bilingual speakers who speak Levantine Arabic (L1) and English (L2) expressed interest to take part in the study and completed a 30 min prescreening session online. The inclusion criteria were (a) being L1 speakers of Levantine Arabic aged 18–60 years old; (b) scoring 75% or higher on questions adapted from the ESL’s Proficiency Test (15 questions); (c) scoring 79% or higher on questions adapted from the ESL’s Arabic Proficiency Test (15 questions), and (d) having no history of hearing loss, neuro-developmental disorders, speech-language disorders, or learning disabilities. The Arabic proficiency cutoff of 79% reflects the average entry-level score for Arabic writing and rhetoric classes for a higher education institution in Jordan between 2018 and 2021, aligning with that institution’s writing proficiency standards and requirements. Each language test included 15 questions assessing writing only, covering cause-effect and relationship, conditional clauses, and verb conjugations. Out of 183, only 49 bilingual adults met the inclusion criteria and were eligible to participate in this study. Because the English and Arabic tests were adopted from ESL educational services, for the English test, we decided to go with the average writing score that Levantine Arabic speakers scored on the writing section of the TOEFL test for the past 5 years. The score was averaged to roughly 75%. Of the 49 adults, 23 were self-identified as females and 26 as males. The majority of the candidates were disqualified because they did not pass the English proficiency test. The 49 participants had higher scores on the Arabic Proficiency Test than on the English Proficiency Test, t(48) = 4.32, p < 0.001. Table 1 summarizes the participants’ characteristics.

Table 1.

Participant Characteristics (n = 49).

All 49 participants were asked to complete the Language Experience and Proficiency Questionnaire (LEAP-Q) (Marian et al., 2007) adapted for Arabic and English speakers. The LEAP-Q was used as a tool to obtain demographic and linguistic background information about each eligible participant. Table 2 shows the self-reported mean ages for language acquisition milestones. The median self-reported Arabic proficiency in LEAP-Q among participants was 10 for speaking (range = 8–10), 10 for understanding (range = 9–10), 10 for reading (range = 8–10), and 10 for writing (range = 9–10) out of 10, while the median self-reported English proficiency in LEAP-Q among participants was 8 for speaking (range = 7–10), 8 for understanding (range = 7–9), 9 for reading (range = 8–10), and 9 for writing (range = 8–10) out of 10. These proficiency ranges (e.g., 8–10 for Arabic speaking), shown in Table 3, correspond to the median ratings; these ratings present participants’ self-reported proficiency on a 0–10 scale. Table 3 also summarizes their reported language experiences and proficiency in Arabic and English, reflecting participants’ self-perceived proficiency levels and the influence of various factors on their language use, with higher values indicating greater proficiency, influence, or exposure. As the language proficiency tests and the LEAP-Q results show, Arabic was the participants’ stronger language among the two. In this study, “bilingual” refers to individuals who functionally use at least two languages in their lives—in this study, Levantine Arabic (L1) and English (L2). Language dominance was determined by comparing participants’ performance on pre-study language proficiency tests (English and Levantine Arabic), as well as their self-reported proficiency via the LEAP-Q. These measures consistently showed higher proficiency in Arabic, confirming it as the dominant language. However, the participants’ LEAP-Q input (as shown in Table 3) indicated that English and Arabic were used to carry out daily functions such as communicating with family members, hanging out with friends, reading, and watching movies. It should be pointed out here, however, that 51% of our participants socioeconomically identified with the working class and 49% identified with the middle class; it is also worth mentioning here that while 37% of our participants indicated that they had completed their high-school education, 63% of them completed, at least, four-year college education. These findings were reported in the participants’ LEAP-Q output. We are cognizant, however, that these self-reported socioeconomic and educational differences may affect language proficiency and task performance, though they were not controlled for in this study. This variability among participants highlights the need for future research to examine their influence on syntactic priming in bilinguals. Our participants also demonstrated good English and Arabic typing skills as they were able to type in English and Arabic and switch between the two languages using the keyboards on their computers.

Table 2.

LEAP-Q Results: Participants’ Language Acquisition.

Table 3.

LEAP-Q Results: Participants’ Proficiency, Contributing Factors, and Exposure.

6.2. Cross-Linguistic Syntactic Priming Task

The stimuli for the cross-linguistic syntactic priming consisted of four written paragraphs, each a personal story, with two types of priming sentence structures (complex and simple) and two priming languages (English and Arabic). Writing was chosen as the mode of the study due to its grammatical manifestations and to help enable deliberate syntactic production critical for priming. Participants wrote in Levantine Arabic when primed with English, and in English when primed with Levantine Arabic; and they were instructed to use Levantine Arabic when the prompt instructs them to do so. Orthographic and directional differences were controlled by selecting proficient bilinguals and allowing ample response time. Examples of these priming stimuli are provided in Appendix A. A complex sentence example, projected in the short English story titled ‘A Trip to the Bahamas’ is “Although at first, we didn’t know how to resolve the issue, my partner came up with a good solution”. Another example is the simple English sentence “They were very keen to study Arabic”, which was included in the English short story titled ‘Unforgettable Teaching Experience’. Additionally, an example of a simple sentence in Levantine Arabic from short Levantine Arabic story titled “رحلة ممتعة إلى العقبه” is “استمتعنا بالسباحة هناك”, meaning “we enjoyed swimming there.” These priming stimuli were written by four bilinguals proficient in speaking and writing Levantine Arabic and English. Each bilingual script writer contributed one personal story of the four personal stories used as priming stimuli. To ensure standardization and consistency across the paragraphs, the script writers normalized the stimuli for the number of sentences, types of verbs, the content of the story, reading level, and syntactic complexity. Additionally, the paragraphs were reviewed and judged by two external consultants who were also proficient in Levantine Arabic and English to ensure uniformity and appropriateness. The script writers of the priming stimuli were recruited through academic networks and personal contacts. They were provided with detailed instructions to write personal stories that adhered to specific linguistic criteria, including number of sentences, types of verbs, content, reading level, and syntactic complexity. The script writers were comparable to the participants in terms of demographic background; they all spoke Levantine Arabic as L1, they spoke English as L2, and they were born in Jordan.

To control for the length of the stimuli, each sentence-type stimulus (story) and its cross-linguistic counterpart were similarly lengthy. That is, the script written in complex English sentences was 14 sentences long, and its Arabic counterpart was also 14 sentences long. Similarly, the script written in simple English sentences was 13 sentences long, and its Arabic counterpart was also 13 sentences long. The stimuli, along with two trial items, were programmed using HTML and JavaScript, and they were hosted on a website affiliated with the Office of Information Technology Hosting System at the University of Colorado at Boulder.

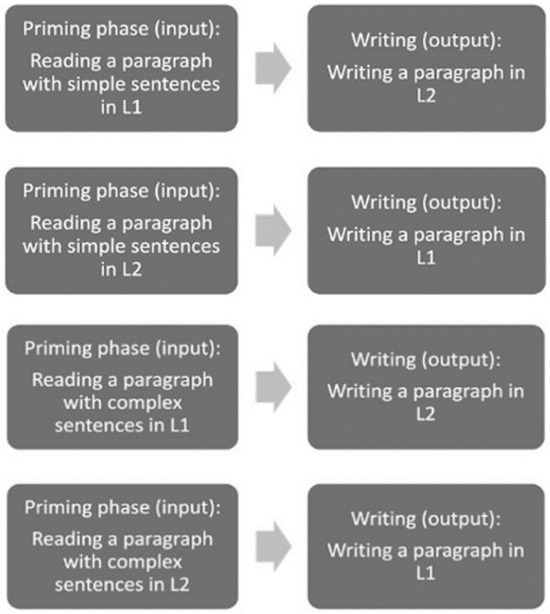

Testing was conducted remotely, with participants situated in a quiet room while interacting with the examiner via Zoom. The syntactic priming task involves two phases: (1) the practice phase and (2) the priming phase. During the practice phase, participants responded to two trial items: one presented in Arabic requiring a response in English, and vice versa. This phase aimed to familiarize participants with written responses. The two trial items were counterbalanced to prevent presentation order bias. After completing the practice phase, the participants were instructed to complete the task within one hour. In this phase, the four priming paragraphs randomly appeared on consecutive screens. For each stimulus, the participant was asked to read the stimulus in one language and respond by writing a personal story in the other language (see Figure 1). For example, one prompt asked participants “Read the following short Arabic story and write in English a similar personal story that happened to you.” Participants received no prompts or feedback on the syntactic structure of the story they read or the one they produced in their responses. They also could not revisit previously completed stimuli. After responding to the four stimuli, participants were prompted to submit their responses on the computer. The generated text data were saved in a confidential folder for manual coding (see Coding and Reliability below).

Figure 1.

Cross-linguistic Priming Phases (Randomized).

6.3. Coding and Reliability

Upon completion, each participant produced four written paragraphs, two in Arabic and two in English. To meet the correct output criteria, participants’ written output must be in the language opposite to that of the priming stimulus. In the coding process, we identified the simple and complex sentences in the participants’ output paragraphs. In this study, simple and complex sentences in Arabic and English were operationally defined based on specific criteria. A simple sentence is defined as containing only one finite verb, demonstrating a single action or idea. A finite verb must meet three criteria: it must show tense; it must show subject–verb agreement; and it must stand alone as the only verb element in the sentence. For example, in Arabic, “[خرجت مع والدي في عرض البحر]” [Al-baħr ʕardˤ fii walad-i maʕ xaraʤt], which means “my father and I took to the sea” and “he laughed at me” in English are considered simple sentences. An example in Arabic would be “[سافرنا سوياً إلى مدينة صديقتي التي تبعد حوالي ٣ ساعات بالسيارة عن مدينتي]” [saːfarnaː sawijjan ʔilaː madiːnat sˤadiːqatiː ʔallatiː tabʕudu ħawaːliː θalaːθ saːʕaːt bi-s-sajjaːrati ʕan madiːnatiː], which means “my friend and I traveled by car to her town, which was a three-hour drive from my hometown”. Similarly, in English, “once we arrived, we started unpacking our bags and settling into our new home”. In this English example, “once we arrived” is a dependent clause, while “we started unpacking our bags and settling into our new home” is the independent clause.

Since our participants were recruited from diverse regions globally, it was expected that their outputs would manifest in various English varieties. Thus, dialectal variations in written language were not considered errors. Cross-linguistic sentences meeting the criteria for simplicity or complexity, even if they contained semantic, spelling, or morphological errors, were still categorized accordingly. Although we did not encounter any case, lexical code-switching within the sentence would not have been considered an error as long as it did not compromise the judgment on the sentence type as defined above. Compound and compound-complex sentences were categorized as non-target sentences. While written English is generally standardized, syntactic variations can occur due to regional or cultural influences. These variations are less pronounced than in spoken dialects, as formal writing typically avoids dialect-specific syntax.

All participants completed all four items in the cross-linguistic syntactic priming task. None of the participants responded to any item using the same language as the priming language. For each participant, the total number of simple versus complex sentences was calculated for the priming sentence type and the priming language conditions. It is important to note that participants might have written varying lengths of paragraphs, making it difficult to directly compare the raw counts of simple and complex sentences between individuals. To address the variability in paragraph lengths among participants, we standardized the data by converting the raw counts of simple and complex sentences into percentages. To calculate the percentage for simple sentence output, we divided the total number of simple sentences by the total number of sentences within each priming condition. Similarly, for complex sentence output, we divided the count of complex sentences by the total number of sentences within each priming condition. The total number of sentences includes simple, complex, and nontarget sentences for each priming sentence type and priming language conditions. The outputs of five randomly selected participants were re-coded by a bilingual Arabic-English syntactician, who is aware of the definition of simple versus complex sentences resulting in a 98.7% agreement for inter-rater reliability. In total, participants generated 1476 cross-linguistic sentences, including 13 non-target sentences (e.g., compound sentences).

6.4. Data Analysis and Outcome Variable Dichotomization

Logistic Regression was used to analyze participants’ cross-linguistic written responses. The dependent variable was whether the written outcomes were primed (yes/no). The independent variables were the priming sentence type (simple or complex) and the priming language condition (Arabic or English). Given that there were differences between participants’ Arabic and English proficiency test scores, we included their Arabic and English Test scores as covariates.

To facilitate logistic regression analysis, we dichotomized the percentage of complex sentences within each participant’s response using a 55% cutoff. This 55% cutoff was determined based on kernel density estimation (Silverman, 2017), which identified an inflection point in the distribution of complex sentence percentages for the complex sentence priming condition, and a similar natural break in the distribution of simple sentence percentages for the simple sentence priming condition. Responses containing 55% or more complex sentences when primed with complex sentences, or 55% or more simple sentences when primed with simple sentences, were classified as ‘primed’ (coded as 1). Conversely, responses containing less than 55% complex sentences when primed with complex sentences, or less than 55% simple sentences when primed with simple sentences, were categorized as ‘not primed’ (coded as 0).

7. Results

Logistic regression analysis revealed a significant cross-linguistic priming effect, χ2(5) = 11.17, p < 0.05; R2 = 0.042; AICc = 268.88) suggesting that exposure to a particular sentence structure in one language was associated with the subsequent sentence production in another language. For instance, when Arabic-English bilinguals were presented with simple sentences in Arabic, they were more likely to produce simple sentences in English. Similarly, exposure to complex sentences in English led to the production of complex sentences in Arabic.

Table 4 summarizes their written responses by sentence type (simple vs. complex sentences) across priming sentence type (simple vs. complex) and priming language (Arabic and English) conditions.

Table 4.

Means and Standard Deviations (SD) of Participants’ Cross-linguistic Simple and Complex Sentences by Priming Sentence Type and by Priming Language condition.

Results showed that Priming Sentence Type was not significant, χ2(1) = 2.64, p > 0.05, suggesting both priming conditions (simple vs. complex sentences) yielded similar levels of primed responses. However, there was a significant effect of Priming Language condition, χ2(1) = 4.76, p = < 0.05, on the likelihood of producing primed responses. Specifically, participants demonstrated a greater likelihood of being primed when the priming language was Arabic compared to English. The interaction between Priming Language condition and Priming Sentence Type reached significance, χ2(1) = 4.14, p < 0.05, suggesting that the effect of priming sentence type on the likelihood of a primed response depended on the priming language. When the priming language was Arabic, participants exhibited a greater likelihood of producing simple English sentences when primed with simple Arabic sentences than producing complex English sentences when primed with complex Arabic sentences. In contrast, when the priming language was English, the complexity of the prime sentence did not significantly impact the production of simple or complex Arabic sentences. Additionally, participants’ Arabic and English proficiency test scores did not significantly affect the likelihood of primed responses (See Table 5 below). As shown in Table 5, the priming effect was more pronounced when Arabic was the priming language, with a higher percentage of primed responses in that condition compared to English.

Table 5.

Logistic Regression Results.

8. Discussion

This study investigated how the presentation of written syntactic structures in one language influenced subsequent production in another language. More specifically, the study targeted this cross-linguistic interaction in late bilinguals who learned Levantine Arabic as their first language (L1) and English as their second (L2). One unique contribution of the current study is the use of a paragraph-long written priming task to examine priming effect and how written syntactic structures could be transferred cross-linguistically. There are three important findings in this study. First, there was a significant cross-linguistic priming effect on participants’ output. That is, prior experience with a specific sentence pattern in one language influenced how the participants produced sentence patterns in the opposite language, which aligns with Hartsuiker and Bernolet’s (2017) theory about cross-language syntactic priming effects in highly proficient L2 users. Second, this effect was observed regardless of whether the priming sentences were simple or complex. Third, the priming effect exhibited an asymmetry: when the priming language was Arabic, the subsequent priming effect observed in English output was more pronounced compared to when the priming language was English and the output was in Arabic, consistent with previous studies (e.g., Bernolet et al., 2013). In what follows, we present the intricacies of syntactic processing in bilingual individuals, examining the roles of priming language and sentence type within the context of a cross-linguistic priming task, followed by a discussion of cross-linguistic syntactic priming in the written modality.

8.1. Syntactic Processing in Bilinguals

Our logistic regression analysis revealed a significant cross-linguistic priming effect on the syntactic structure of participants’ written responses. Our participants, when primed with complex sentences in one language (e.g., Arabic), were more likely to produce complex sentences in the opposite language (e.g., English). Similarly, when primed with simple sentences in one language, participants generated more simple sentences in the opposite language. That is, our participants were more likely to write sentences mirroring the structure of the priming text.

These results align with the shared syntax account, which proposes that bilinguals may possess a shared cognitive mechanism for syntactic representation (Hartsuiker et al., 2004). Although there are significant syntactic differences between Levantine Arabic and English, the results suggest that when bilinguals activate, for instance, a simple sentence in Arabic, the presentation temporarily retains some of its activation, resulting in cross-linguistic priming for this syntactic structure when a subsequent simple sentence is formulated in English. Our findings suggest that Arabic-English bilingual speakers appear to process syntactic structures of both languages, although the two languages are topologically, typologically, and typographically dissimilar. The findings provide further evidence for theories of shared syntactic representations between languages (Fleischer et al., 2012; Hartsuiker & Bernolet, 2017; Hartsuiker et al., 2004; Salamoura & Williams, 2007). In the same vein, the results are also in line with activation-based accounts of syntactic priming (Brennan & Clark, 1996, wherein exposure to a particular syntactic structure activates its mental representation, thereby influencing subsequent language production. The overall findings in this study could contribute to the framework for further studying cross-linguistic sentence processing in bilinguals, providing a deeper understanding of the complexities of bilingual syntactic processing.

Notably, the cross-linguistic priming effects in our study are in contrast with the results in the study by Grosvald and Khwaileh (2019) where robust evidence of syntactic priming was detected within each language but not across languages in Arabic-English bilingual speakers. One possible explanation for the discrepancy might be related to task difficulties. While their experiment looks at syntactic priming between English and Arabic in terms of voice-structure priming (i.e., passive vs. active voice), the current study examined sentence structure priming (i.e., simple vs. complex sentences). Another possible explanation for this difference could be attributed to the methodological differences between the current study and Grosvald and Khwaileh (2019). In contrast to the current study, participants’ Arabic and English skills in Grosvald and Khwaileh (2019) were not controlled for. In addition to self-reported bilingualism, they determined their participants’ eligibility based on The International English Language Testing System (IELTS) scores, which are typically used for academic, professional, or migration purposes. This approach was different from the language proficiency measures used in this study. Moreover, the range of Arabic and English proficiency levels among participants could be influenced by their varied Arabic dialects (e.g., Gulf Arabic, Levantine Arabic) and differing degrees of exposure to English.

8.2. The Role of Sentence-Type Priming

Although our analysis revealed a significant cross-linguistic priming effect, sentence type (simple vs. complex) did not significantly impact participants’ output; both priming conditions yielded similar levels of primed responses. The lack of a significant effect of priming sentence type (simple vs. complex) could be attributed to several factors. Firstly, the small sample size might have limited the statistical power to detect subtle differences in priming effects between simple and complex sentences. Secondly, the free-form nature of the paragraph writing task in this cross-linguistic priming study, while promoting natural language production, also introduces a high degree of variability in the written output. This variability, arising from individual differences in writing styles, cognitive processes, and the multifaceted nature of language production, could potentially obscure any underlying priming effects specifically related to sentence complexity. Increased sentence complexity is associated with higher working memory demands and processing difficulty (Kellogg et al., 2007; Vogelzang et al., 2020). It is possible that the priming effects observed in this study are influenced by cognitive effort rather than syntactic similarity. Future research should explore the role of cognitive load by incorporating additional measures, such as reaction time or eye-tracking, to distinguish syntactic priming effects from general processing ease or difficulty. Thirdly, individual differences in language proficiency and processing styles could further contribute to the lack of a clear sentence-type effect. From the perspectives of the transient activation theory, the temporary activation of syntactic structures might not discriminate strongly between simple and complex sentences, particularly in a delayed written production task where the priming effect might have decayed. However, the absence of significant effect of priming sentence type might suggest that, from a theoretical standpoint, the shared syntax account (Hartsuiker et al., 2004) is at play. Further research incorporating control conditions and larger sample sizes is needed to elucidate the nuanced relationship between sentence complexity and cross-linguistic priming effects.

8.3. The Role of Priming Language

One important finding of our study is the significant effect of the priming language condition on the likelihood of producing primed responses. More specifically, our participants demonstrated a greater tendency of being primed when the priming language was Arabic compared to English. While this asymmetry might seem to challenge the shared syntax account, prior research suggests that such asymmetrical priming effects are common in bilingual processing (e.g., Schoonbaert et al., 2007; Bernolet et al., 2013), where priming from L1 to L2 was stronger than from L2 to L1. For example, Dutch-English bilinguals (Schoonbaert et al., 2007), when priming occurred from L1 (Dutch) to L2 (English), the syntactic priming effect was enhanced. However, in the reverse direction, from L2 (English) to L1 (Dutch), there was no significant increase in the priming effect. Importantly, asymmetry does not negate shared syntactic representations; rather, it reflects variations in accessibility and cognitive resources required for processing each language.

Furthermore, our results showed an interaction between priming language and priming sentence type. When the priming language was Arabic, and the sentence type was simple, participants showed a greater tendency of producing simple English sentences than producing complex English sentences when the priming language was Arabic and the sentence type was complex. In contrast, when the priming language was English, the complexity of the prime sentence did not significantly impact the production of simple or complex Arabic sentences. This interaction suggests that the influence of priming language condition on syntactic output is modulated by sentence complexity, particularly when priming occurs from the stronger L1.

The observed stronger priming effect from Arabic (L1) to English (L2) can be attributed to several factors. First, participants demonstrated higher proficiency in Arabic, which likely facilitated the activation and retention of syntactic structures, leading to greater transfer to English. Second, cognitive load may play a role—processing complex structures in a less proficient language (L2) places greater demands on working memory, which may reduce the likelihood of priming effects. These findings are consistent with activation-based models of syntactic priming (Brennan & Clark, 1996), where L1 structures are more readily activated and transferred to L2 due to stronger memory representations. While the asymmetry in priming effects might suggest differences in accessibility between languages, it does not imply the absence of shared syntactic representations. Instead, it highlights the dynamic nature of bilingual syntactic processing, where proficiency, cognitive load, and language dominance interact to shape cross-linguistic influences. The results contribute to a more nuanced understanding of how syntactic structures are accessed and utilized in bilinguals, supporting the shared syntax account while acknowledging the influence of language-specific factors.

8.4. Cross-Linguistic Syntactic Priming in Written Modality

The use of written, rather than spoken, language marks another point of contrast and a useful comparison between this study and previous research on the topic. This is because, even though some forms of written language, such as instant messages and informal letters, can be closer to spoken language, written language is typically more formal, complex, and intricate than spoken language. Furthermore, participants were asked to respond in a paragraph length (not in a sentence length) to a paragraph they have already viewed in a language different from the language they are asked to write in. In this regard, cognitive processes involved in reading and writing in the digit format are different from those cognitive processes involved in the spoken form of the language. According to Gough and Tunmer (1986), reading a text includes the ability to decode the text and comprehend it. Because participants must interact with the written form, this involves cognitive language skills such as working memory, attention, phonological awareness, morphological awareness, vocabulary, grammatical knowledge, and comprehension monitoring (Apel, 2022). The priming task’s cognitive demands, including executive functions like planning and attention, provide insights into bilingual syntactic representation. Managing linguistic interference, sustaining attention, and integrating syntactic structures across languages are all essential cognitive processes at play. Given the written modality of the task, participants had to engage in complex linguistic processing, including reading comprehension, working memory, and structural planning, which likely influenced their syntactic choices.

Furthermore, written language can utilize typographical features—e.g., punctuation, headings, layouts, colors, etc.—to make a message clearer. Thus, written outputs are expected to contain longer sentences and more complex tenses than spoken outputs. Because of the lack of social pressures related to turn-taking, written language forms are typically produced slower than spoken ones, resulting in clearer and more grammatical outputs with a noticeable lack of repetitions, incomplete sentences, filler words, interruptions, corrections, and other disfluencies. That said, we believe that the complex cognitive skills involved in reading (e.g., Arabic) and writing (e.g., English) during the cross-linguistic priming task would provide insights into how syntactic representation of bilinguals’ two languages unfold in cross-linguistic settings.

8.5. Study Limitations

Although this study provides unique contributions to the field of research on cross-linguistic priming, it has several limitations. Firstly, the absence of conditions where the priming language and the language used for the written paragraph were the same (i.e., L1-L1 and L2-L2) limits a comprehensive understanding of how language proficiency interacts with priming effects. Secondly, while the dichotomization of continuous proportion data for logistic regression, it may have resulted in some loss of data nuance. Thirdly, while all participants demonstrated proficient English and Arabic typing skills, as evidenced by their ability to type and switch between the two languages using their computer keyboards, we acknowledge that we did not explicitly test their typing proficiency in L1 and L2. Given the potential impact of typing proficiency on production decisions—where participants less proficient in typing in their L2 might avoid longer and more complex sentences—we recognize the importance of including such assessments in future research. Tasks such as the Copy task—Inputlog can provide a more accurate measure of typing skills, allowing for a better understanding of their influence on syntactic priming effects. Fourthly, the sample size of participants, their linguistic background, and the use of virtual data collection should be taken into consideration. That is, the sample size of 49 participants is considered relatively small, considering that the worldwide population of Levantine Arabic speakers is estimated to be around 38 million people. Additionally, the age of the participants (ranging from 18 to 60) could affect the results, as cognitive processing and language abilities can change across the lifespan. Moreover, this study considered a single variety of Arabic—namely, Levantine Arabic. However, it is unknown whether the findings could generalize to other varieties of Arabic, like Gulf Arabic or Egyptian Arabic. Also, the different orthography and syntactic typology used in Levantine Arabic could potentially affect language processing. Prior work has demonstrated that such differences can significantly influence language processing (e.g., Taha, 2013; Saiegh-Haddad & Henkin-Roitfarb, 2014). Specifically, the diglossic nature of Arabic, where Modern Standard Arabic (MSA) and colloquial varieties like Levantine Arabic have distinct orthographic and syntactic systems, can pose additional cognitive demands on bilinguals. These factors must be considered when interpreting the results of syntactic priming studies involving Arabic and other languages. Lastly, the recruitment process targeted well-educated Arabic bilinguals with an average of just over 17 years of formal education and basic digital proficiency. The inclusion of participants with diverse educational backgrounds and varying levels of digital proficiency in future research would provide a more comprehensive understanding of syntactic priming effects, reflecting a wider spectrum of the bilingual population.

9. Conclusions

The current research explored cross-linguistic syntactic priming in late bilinguals whose native language was Levantine Arabic (L1) and English (L2) using a written production task. The aim was to clarify the effect of prime sentence types (simple vs. complex) and the language type under which the priming was administered (Levantine Arabic vs. English). The results showed a strong cross-linguistic priming effect, thus, showing that the syntactic structure of a prime within one language influences the syntactic structure within the respective other language. The findings are consistent with the shared syntax hypothesis that bilingual speakers maintain consistent syntactic representations for both languages despite the typological dissimilarity between Levantine Arabic and English. The fact that the effect was strong with both simple and complex sentences indicates that the shared syntactic system within this group is not limited by the complexity of the sentences.

The assessment, however, showed an important difference in the salience of the priming effect: the salience was considerably stronger with the use of the priming language being Levantine Arabic (L1) compared to English (L2). These outcomes are found to be consistent with previous research that has shown that a native or native language has a greater effect on syntactic production in a second language due to a higher competence or stronger cognitive representations that are caused by L1. Another important finding was the interaction that was seen between the language used for the prime and the complexity of the sentences, particularly in the case of Levantine Arabic. This finding suggests that the salience of a language interacts with syntactic complexity, thus modulating cross-linguistic priming effects and advancing our understanding of bilingual syntactic processing.

The integration of the written modality into this research extends the boundaries of syntactic priming research that has mostly focused on spontaneous speech. The persistence of cross-linguistic priming in written production emphasizes the widespread availability of common syntactic structures to linguistic production tasks. This finding has important implications for models of bilingual language production, showing that syntactic integration does not take place only within the spontaneous speech context but also within the more deliberate and structured context of writing.

Future investigations can focus on a range of possibilities for the extrapolation of the findings. Determining the extent to which the consequences of priming generalize to speech production would clarify modality-specific distinctions. The use of other language pairs composed of typologically dissimilar languages would strengthen the cross-linguistic generality of common syntactic representations. The examination of individual difference measures such as linguistic competence, control processes, or working memory with respect to cross-linguistic priming would strengthen the knowledge regarding cognitive processes. The use of within-language priming tasks (e.g., English-English, Arabic-Arabic) would allow direct comparisons to be made with cross-linguistic tasks and further clarify syntactic processing within bilingual speakers.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, J.A.K.; methodology, J.A.K. and P.F.K.; software, J.A.K.; validation, J.A.K. and P.F.K.; formal analysis, J.A.K. and P.F.K.; investigation, J.A.K.; resources, J.A.K.; data curation, J.A.K. and P.F.K.; writing—original draft preparation, J.A.K.; writing—review and editing, J.A.K. and P.F.K.; visualization, J.A.K. and P.F.K.; supervision, P.F.K.; project administration, J.A.K. and P.F.K. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The current study was conducted in accordance with the ethical standards of human subject research, including the principles outlined in the Declaration of Helsinki, and was approved by the institutional review board at the University of Colorado (protocol code 21-0203).

Informed Consent Statement

Written informed consent has been obtained from the patient(s) to publish this paper.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in this study are included in the article. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Appendix A

Each of the four priming texts below is either in English or Arabic and uses either complex or simple sentence structure.

- English Text, Complex Sentences

- “A Trip to Bahamas”

My friend and I decided that we should go on a field trip from my hometown to the Bahamas. The trip was not an easy one since it needs a lot of preparation and big budget. We were not able to find a car that would take us all the way to Florida from which we will depart to the island. Although at first, we didn’t know how resolve the issue, my partner came up with a good solution, which was inviting another friend who owns a comfortable car to travel with us. We drove across the country from San Diego, California all the way to Miami, Florida where we started our ocean trip from Miami to the Bahamas. This was my first time that I went on a cruise trip on the East Coast, which was a wonderful experience. The ship itself was a small town that had all of the luxury services. It has all of the fun games that you could enjoy during the cruising time. Although we aimed to enjoy our time when we arrive to the island, we actually spent a quality time in the ship itself where we danced, played cards, gambled, and swam. We also enjoyed the sunrise in the middle of the ocean where you could smell the breeze of the ocean and watch the dolphins swim and dance. Once we arrived in the island, we packed out backpacks with some swimming clothes, water, snacks, and—of course—my professional camera. We rented a small cart to drive around the island and visit some of the remote areas that I thought we would enjoy seeing. It was an amazing trip that I have never experienced before.

- English Text, Simple Sentences

- “Unforgettable Teaching Experience”

Last year, I had a chance to teach Arabic for L2 speakers of Arabic in my university in Bloomington. It was my first time to teach that type of classes. In that class, I met many wonderful students. They were very keen to study Arabic. Arabic was not their first language. It was supposed to be a very difficult language for them to learn. During that class, I had many fruitful conversations in Arabic with my Arabic learners. I was very surprised and impressed by their Arabic proficiency. In fact, their willingness to learn Arabic impressed me the most. They also asked many questions about Arabic and the Middle-Eastern culture. Preciously, I learned a lot from my students during that experience. That was really a great unforgettable experience for me. I will always miss that opportunity.

- Arabic Text, Complex Sentences

“يوم عيد الشكر مع عائلة أمريكية”

ذات يوم عندما كنت ادرس في ولاية انديانا، دعتني احدى صديقاتي لزيارة اسرتها والبقاء معهم طيلة الإجازة. كنت سعيدة جدا اني سوف ازور وأتعرف على جميع أفراد اسرتها. سافرنا سويًا الى مدينة صديقتي التي تبعد حوالي ٣ ساعات سيرا بالسيارة عن مدينتي. ورغم ان السماء كانت تثلج الا ان الرحلة كانت ممتعة. عندما وصلنا الى البيت صديقتي بعد الظهر، استقبلتنا والدة صديقتي بحفاوة شديدة. ثم بدأت تعرفني صديقتي بأخواتها التسعة. كانت اسرة أمريكية كبيرة على غير عادة الأمر الذي جعلني مندهشاً. وبينما قضينا وقتا جميلا نطبخ وناكل سويًا،شاهدنا أيضاً بعض التلفاز. وكذلك أتيحت لنا الفرصة أن نتناقش في بعض الأمور من بينها اختلاف الثقافات. لقد تبادلنا كثير من النقاشات التي تعرفنا من خلالها على ثقافات وعقليات بعضنا البعضا لأمر الذي جعلنا سعداء جدا بهذا.وأثناء الرحلة إلى مدينتي، كنت افكر كم هو جميل ان يكون هناك حوار حضارات وتوافق انساني راقي رغم اختلاف ثقافاتنا وديننا احيانا. وصلت الى بيتي الذي اشتقت اليه كثيرا.و رغم أني كنت متعبة، كنت سعيدة بهذة الخبرة الانسانية الرائعة

- Arabic Text, Simple Sentences

“رحلة ممتعة إلى العقبه”

في شتاء السنة الماضية، ذهبت أنا وأصدقائي إلى العقبة في رحلة مدرسية. و بينما هناك، تحدثنا أنا وأصدقائي عن خططنا. فقررنا أالذهاب إلى الشاطئ. لقد استمتعنا بالسباحة هناك.ثم قام اثنان من أصدقائي بالتسابق في البحر. و بعد ذلك ذهبنا إلى السوق. وقمنا بشراء احتياجاتنا الأساسية. ومن ثم ذهبنا إلى احدى المطاعم لتناول الغداء. و بعد الغداء ,تسكعنا بالسوق قليلا. ومن ثم اتصل المعلم بنا. و طلب منا الاجتماع عند السارية. عند وصولنا, قام البعض من أصدقائي بركوب الدراجات الهوائية. بصراحة, كانت تلك الرحلة من أجمل الرحلات

References

- Aoun, J., Benmamoun, E., & Sportiche, D. (2010). The syntax of Arabic. Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Apel, K. (2022). A different view on the simple view of reading. Remedial and Special Education, 43(6), 434–447. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arai, M. (2012). What can head-final languages tell us about syntactic priming (and vice versa)? Language and Linguistics Compass, 6(9), 545–559. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benmamoun, E. (2017). VSO word order, primarily in Arabic languages. In M. Everaert, & H. van Riemsdijk (Eds.), The Wiley Blackwell companion to syntax (2nd ed., pp. 1–30). Wiley-Blackwell. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berninger, V. W., & Winn, W. D. (2006). Implications of advancements in brain research and technology for writing development, writing instruction, and educational evolution. In C. A. MacArthur, S. Graham, & J. Fitzgerald (Eds.), Handbook of writing research (pp. 96–114). The Guilford Press. [Google Scholar]

- Bernolet, S., Hartsuiker, R. J., & Pickering, M. J. (2013). From language-specific to shared syntactic representations: The influence of second language proficiency on syntactic sharing in bilinguals. Cognition, 127(3), 287–306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brennan, S. E., & Clark, H. H. (1996). Conceptual pacts and lexical choice in conversation. Journal of Experimental Psychology: Learning, Memory, and Cognition, 22(6), 1482–1493. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chang, F., Dell, G. S., & Bock, K. (2006). Becoming syntactic. Psychological Review, 113(2), 234–272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, T. (2023). The effects of syntactic priming on language processing and learning. Lecture Notes in Education Psychology and Public Media, 6, 102–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Desmet, T., & Declercq, M. (2006). Cross-linguistic priming of syntactic hierarchical configuration information. Journal of Memory and Language, 54(4), 610–632. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elman, J. L. (1995). Language as a dynamical system. In R. F. Port, & T. van Gelder (Eds.), Mind as motion: Explorations in the dynamics of cognition (pp. 195–223). MIT Press. [Google Scholar]

- Favier, S., Wright, A., Meyer, A., & Huettig, F. (2019). Proficiency modulates between- but not within-language structural priming. Journal of Cultural Cognitive Science, 3(Suppl. 1), 105–124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fleischer, Z., Pickering, M. J., & Mclean, J. F. (2012). Shared information structure: Evidence from cross-linguistic priming. Bilingualism: Language and Cognition, 15(3), 568–579. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gollan, T. H., Sandoval, T., & Salmon, D. P. (2011). Cross-language intrusion errors in aging bilinguals reveal the link between executive control and language selection. Psychological Science, 22(9), 1155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gough, P. B., & Tunmer, W. E. (1986). Decoding, reading, and reading disability. Remedial and Special Education, 7(1), 6–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Green, D. W. (1998). Mental control of the bilingual lexico-semantic system. Bilingualism: Language and Cognition, 1(2), 67–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grosjean, F. (2012). Bilingualism: A short introduction. In F. Grosjean, & P. Li (Eds.), The psycholinguistics of bilingualism (pp. 5–25). John Wiley & Sons. [Google Scholar]

- Grosvald, M., & Khwaileh, T. (2019). Processing passive constructions in Arabic and English: A crosslanguage priming study. Al-’Arabiyya, 52, 1–28. [Google Scholar]

- Hartsuiker, R. J., Beerts, S., Loncke, M., Desmet, T., & Bernolet, S. (2016). Cross-linguistic structural priming in multilinguals: Further evidence for shared syntax. Journal of Memory and Language, 90, 14–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hartsuiker, R. J., & Bernolet, S. (2017). The development of shared syntax in second language learning. Bilingualism: Language and Cognition, 20(2), 219–234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hartsuiker, R. J., Pickering, M. J., & Veltkamp, E. (2004). Is syntax separate or shared between languages? Cross-linguistic syntactic priming in Spanish–English bilinguals. Psychological Science, 15(6), 409–414. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hartsuiker, R. J., & Westenberg, C. (2000). Word order priming in written and spoken sentence production. Cognition, 75(2), B27–B39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hayes, J. R. (2012). Modelling and remodelling writing. Written Communication, 29(3), 369–388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hayes, J. R., & Berninger, V. W. (2014). Cognitive processes in writing. In T. A. Sills, L. K. Wolbers, & L. A. Melton (Eds.), Writing development in children with hearing loss, dyslexia, or oral language problems: Implications for assessment and instruction (pp. 3–15). Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hsieh, Y. (2017). Structural priming during sentence comprehension in Chinese–English bilinguals. Applied Psycholinguistics, 38(3), 657–678. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jackson, C. N., & Hopp, H. (2020). Prediction error and implicit learning in L1 and L2 syntactic priming. International Journal of Bilingualism, 24(5–6), 895–911. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Juffs, A., & Harrington, M. (2011). Aspects of working memory in L2 learning. Language Teaching, 44(2), 137–166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kellogg, R. T., Olive, T., & Piolat, A. (2007). Verbal, visual, and spatial working memory in written language production. Acta Psychologica, 124(3), 382–397. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kim, S. Y., Liu, L., Liu, L., & Cao, F. (2020). Neural representational similarity between L1 and L2 in spoken and written language processing. Human Brain Mapping, 41(17), 4935–4951. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lam, B. P. W., & Sheng, L. (2016). The development of morphological awareness in young bilinguals: Effects of age and L1 background. Journal of Speech, Language, and Hearing Research, 59(4), 732–744. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, Y. C., Chen, X., & Geva, E. (2014). Concurrent and longitudinal cross-linguistic transfer of phonological awareness and morphological awareness in Chinese-English bilingual children. Written Language and Literacy, 17(1), 89–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marian, V., Blumenfeld, H. K., & Kaushanskaya, M. (2007). The language experience and proficiency questionnaire (LEAP-Q): Assessing language profiles in bilinguals and multilinguals. Journal of Speech, Language, and Hearing Research, 50(4), 940–967. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohammad, M. A. (2000). Word order, agreement and pronominalization in standard and Palestinian Arabic. John Benjamins Publishing Company. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Niedo, J., Abbott, R. D., & Berninger, V. W. (2014). Predicting levels of reading and writing achievement in typically developing, English-speaking 2nd and 5th graders. Learning and Individual Differences, 32, 54–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Oberauer, K. (2019). Working memory and attention—A conceptual analysis and review. Journal of Cognition, 2(1), 36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olson, D. R. (1994). The world on paper: The conceptual and cognitive implications of writing and reading. Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Perkins, D. N., & Salomon, G. (1988). Teaching for transfer. Educational Leadership, 46(1), 22–32. [Google Scholar]

- Pickering, M. J., & Ferreira, V. S. (2008). Structural priming: A critical review. Psychological Bulletin, 134(3), 427–459. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pickering, M. J., & Garrod, S. (2004). Toward a mechanistic psychology of dialogue. Behavioral and Brain Sciences, 27(2), 169–190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Saiegh-Haddad, E., & Henkin-Roitfarb, R. (2014). The structure of Arabic language and orthography and its implications for reading instruction. In E. Saiegh-Haddad, & R. M. Joshi (Eds.), Handbook of Arabic literacy: Insights and perspectives (pp. 3–28). Springer. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salamoura, A., & Williams, J. N. (2007). Processing verb argument structure across languages: Evidence for shared representations in the bilingual lexicon. Applied Psycholinguistics, 28(4), 627–660. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schoonbaert, S., Hartsuiker, R. J., & Pickering, M. J. (2007). The representation of lexical and syntactic information in bilinguals: Evidence from syntactic priming. Journal of Memory and Language, 56(2), 153–171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silverman, B. W. (2017). Density estimation for statistics and data analysis (1st ed.). Routledge. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Son, M. (2020). Cross-linguistic syntactic priming in Korean learners of English. Applied Psycholinguistics, 41(5), 1223–1247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, Y., & Do, Y. (2018). Cross-linguistic structural priming in bilinguals: Priming of the subject-to-object raising construction between English and Korean. Bilingualism: Language and Cognition, 21(1), 47–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taha, H. (2013). Reading and spelling in Arabic: Linguistic and orthographic complexity. Theory and Practice in Language Studies, 3, 721–727. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tannen, D. (1982). Spoken and written language: Exploring orality and literacy. Praeger. [Google Scholar]

- Tooley, K., & Traxler, M. (2010). Syntactic priming effects in comprehension: A critical review. Language and Linguistics Compass, 4(10), 925–937. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Versteegh, K. (2001). The Arabic language. Edinburgh University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Vogelzang, M., Thiel, C. M., Rosemann, S., Rieger, J. W., & Ruigendijk, E. (2020). Neural mechanisms underlying the processing of complex sentences: An fMRI study. Neurobiology of Language, 1(2), 226–248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weber, K., & Indefrey, P. (2009). Syntactic priming in German-English bilinguals during sentence comprehension. NeuroImage, 46(4), 1164–1172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, W. (2020). Structural priming: A new perspective of language learning. American Journal of Applied Psychology, 9(4), 124–130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).