2.1. The Semantics of Dutch Present Participle MAs

The main focus of this paper is Dutch present participles like those in (2) that specify the manner of an event. These participial patterns share this meaning with the MAs in (1); all bold-faced constituents in (1–2) answer the question of how (i.e., in what way) an action was carried out. As

Piñón (

2007) argues, MAs do this as predicates over manner objects of type

m, which are ontologically dependent on events of the verbal projections they modify.

In discussing the semantics of Dutch present participle MAs, it is important to note that Dutch adverbial participles like

lopend (which I may refer to as ‘bare’ present participles because they are not suffixed with -

erwijs) are ambiguous between such a manner reading and a temporal reading like that of a secondary predicate; (2a) could alternatively be translated as ‘Reinder goes home

while walking’, which puts focus on the simultaneity of a going-home event and a walking event. These two readings of the bare Dutch present participle can be difficult to tell apart. However, the context of the sentence in which the participle occurs can make either of the manner or temporal readings more or less prominent/well formed; as

Van de Velde (

2005, p. 120) notes, in (3) (adapted from

Van de Velde (

2005), my glosses and translations, grammaticality judgments original) the bare participle

spelend in (3a) is slightly degraded in a context where the manner of learning is under discussion.

| (3) | Context: on the ways actors used to learn scripts |

| | a. | ?Vroeger ging het teksten leren spel-end […] |

| | | previously went the texts learning play-ptcp |

| | b. | Vroeger ging het teksten leren spel-end-erwijs […] |

| | | previously went the texts learning play-ptcp-erwijs |

| | | Both intended: ‘Previously, learning of scripts happened by way of playing…’ |

I agree with Van de Velde’s assessment that this is likely due to the fact that the bare participle is not interpreted with a relevant manner but a temporal reading, which is less relevant to the context under discussion. In contrast to the bare present participle, the Dutch present participle form marked with -erwijs has only a manner reading in (3b) and is well formed as a result.

As a final note on the semantics of Dutch bare present participle MAs, an anonymous reviewer points out that the examples in (4) suggest that there is a difference in terms of eventivity between the participle MA

zingend and the adjectival MA

vrolijk; while

zingend suggests an event of singing simultaneous to the talking event,

vrolijk does not. However, I disagree with the reviewer that the manner reading they provide (see the translation, adopted verbatim) suggests this difference; the only reading that (4a) has to my native ear is one in which there is a single event of talking, which takes place in a sing-song tone of voice or manner. To put it differently, an event of talking singingly does not entail an event of singing. In fact, I cannot construe (4a) to have a reading where the subject is both talking and singing simultaneously: doing one excludes doing the other. Thus, here we find an example of how the sentential context disambiguates between the two possible readings of bare Dutch present participle adverbials. To illustrate that the different readings of bare Dutch present participle adverbials also have an impact on their morpho-syntax, consider how adding the

al ‘while’ particle, signaling progressive aspect, yields a degraded result in (5). As I discuss in

Section 2.2, the

al particle is generally well formed with (temporal) present participles. The fact that (5) is ill-formed despite this suggests to me that (4a) cannot be construed with two overlapping events and that a manner reading of the participle is forced (as the reviewer’s translation suggests). Thus, instead of illustrating a contrast in eventivity between the participle MA in (4a) and the adjective in (4b), these data show they are semantically parallel in entailing only a single event, and the morpho-syntactic data in (5) support this.

| (4) | a. | Ze praatte zingend tegen Klaas. |

| | | she talked singing to Klaas |

| | | ‘She talked to Klaas in a singing manner.’ |

| b. | Ze praatte vrolijk tegen Klaas. |

| | | she talked merrily to Klaas |

| | | ‘She talked to Klaas merrily.’ |

| (5) | ??Ze praatte al zingend tegen Klaas. |

| | she talked while singing to Klaas |

| | Intended: ‘She talked to Klaas while she was singing.’ |

Dutch present participles marked with -

erwijs are also ambiguous between a temporal and a manner reading. In their study of Dutch adverbs formed with -

erwijs,

De Belder and Vanden Wyngaerd (

2024) show that Dutch present participles with -

erwijs can realise different adverbial projections in the Cinquean hierarchy (

Cinque, 1999); they can realise an adverbial projection marking a progressive aspect (with a reading I have so far called a temporal reading), as in (6a), or an adverbial projection marking manner (labelled Voice in

Cinque, 1999), as in (6b) ((6ab) both taken from

De Belder and Vanden Wyngaerd (

2024, p. 8), gloss and translations original). The contrast in the well-formedness of

al in (6a) and (6b) mirrors that of the well-formedness of

al with bare Dutch present participles observed between (5) and (4a): the well-formedness of

al is contingent on the temporal, eventive reading of the present participle adverbial, and it is ill-formed under a non-eventive manner reading of a Dutch present participle (regardless of whether or not the participle is bare or marked with -

erwijs).

| (6) | a. | (Al) zingend-erwijs kwam Mathilde de trap af. |

| | | PRT singing-ERWIJZE came Mathilde the stairs down |

| | | ‘Mathilde came down the stairs singing.’ |

| b. | (*Al) subtiel-erwijze liet hij merken dat die uitkomst hem niet beviel. |

| | | PRT subtly-erwijs let he know that that outcome him not pleased |

| | | ‘He subtly made it known that he was not pleased with the outcome.’ |

The discussion in this section shows that Dutch present participles are potentially ambiguous between a manner or a temporal reading and that care must be taken to control for the manner reading that I am concerned with here. As we have seen, sentential context can promote one of the two readings over the other or outright rule out one of them because they only imply one event, resulting in disambiguation. In addition, the different readings of both bare Dutch present participle adverbials and those marked with -erwijs have repercussions for their morpho-syntactic properties: only under a temporal reading do they support al. In the next section, I discuss more morpho-syntactic as well as phonological properties of Dutch present participle MAs and how they allow us to tell them apart from temporal adverbial participles. The main thrust of it is that Dutch present participle MAs exhibit adjectival properties and not verbal ones.

2.2. Dutch Present Participle MAs Exhibit Adjectival, Not Verbal Properties

Concerning the syntactic properties of Dutch present participles,

Bennis and Wehrmann (

1990) argue that they constitute a diverse class that exhibits mixed adjectival and verbal properties. The point of departure for them are observations about the distribution of participles in adjunct and complement positions: while they appear rather freely as attributive adjectives in NPs (7a) and adverbs in VPs (7b), not all of them appear freely in the complement position—compare

huilend in (8a), which cannot appear in the copular construction like the adjective

zielig, with

ontroerend ‘moving’ in (8b), which can be ((7–8) adapted from

Bennis & Wehrmann, 1990).

| (7) | a. | de zing-end-e detective |

| | | the sing-ptcp-agr detective |

| b. | Ik dans zing-end in de regen. |

| | | I dance sing-ptcp in the rain |

| (8) | a. | Reinder is zielig/*huil-end. |

| | | Reinder is pitiful/cry-ptcp |

| b. | Dat argument is ontroer-end. |

| | | that argument is move-ptcp |

As Bennis and Wehrmann observe, in particular, those present participles derived from Experiencer verbs are well-formed adjectives in complement or predicative position as in (8b). As finite verbs, these Experiencer verbs realise their Experiencer arguments differently from adjectives with an Experiencer argument, witness (9): the Experiencer argument of the verb in (9a) surfaces as a pronoun which cannot be introduced by the preposition voor, but the Experiencer argument of painful in (9b) must surface as a PP headed by voor.

| (9) | a. | Dat argument ontroert (*voor) mij. |

| | | that argument moves for me |

| b. | Dat argument is pijnlijk *(voor) mij. |

| | | that argument is painful for me |

Bennis and Wehrmann go on to observe that participles derived from Experiencer verbs display variable argument structure properties when they appear as attributive adjectives with nouns: the Experiencer argument pronoun of ontroerende in (10) can be introduced by the preposition voor but need not be.

| (10) | Het (voor) mij ontroer-end-e argument. |

| | the for me move-ptcp-agr argument |

Given this mixed adjectival vs. verbal behaviour of Dutch present participles, the question arises as to whether the relevant present participles in Dutch MAs are adjectival or verbal. I argue, based on facts about the stress patterns of present participle MAs of separable particle verbs, that they are adjectival as follows:

5 as

De Belder and Vanden Wyngaerd (

2024, p. 12), citing

Bennis and Wehrmann (

1990), note, Dutch separable particle verbs like

uitvoeren ‘implement’ typically carry the main stress on the particle (

úit-voeren), but adjectivising derivational morphology shifts this stress to the right (

uit-vóér-baar, ‘implementable’). Taking a look now at the stress pattern of the present participle of the Experiencer verb

op-vallen ‘strike’ (lit.: up-fall) used as an attributive modifier in (11), we see again that its Experiencer argument can be realized variably as a pronoun or a PP embedding a pronoun. In addition, we see that the stress pattern on the present participle correlates to the realization of the Experiencer argument: in (11a), the Experiencer argument is realized as a pronoun, like in (9a) with the Experiencer verb, and in (11b), the Experiencer argument is realized as a PP, like in (9b) with the Experiencer adjective.

| (11) | a. | het mij óp-vall-end-e argument |

| | | the me up-fall-ptcp-agr argument |

| b. | het voor mij op-váll-end-e argument |

| | | the for me up-fall-ptcp-agr argument |

| | | Both: ‘the argument that stands out to me’ |

The present participle that realises its Experiencer like the verb carries stress on the particle

op, and the present participle that realises its Experiencer like the adjective has its main stress shifted to the right. This suggests that the stress pattern we observe on the present participle is an indication as to its adjectival vs. verbal nature. Turning now to the present participle MA

opvallend in (12), we see that, used as an MA, the stress pattern of the participle is consistent with that of an adjectival analysis of the participle: it is shifted from the particle to the right, and the MA is ill-formed if stress falls on the particle itself. To confirm we are dealing with a manner reading of the present participle, we can test if

al is grammatical or not (recall from

Section 2.1 that

al is ill-formed with present participle MAs): the ill-formedness of

al in (12) confirms that the present participle has a manner interpretation and not a temporal one. The pattern in (12) can be replicated with a present participle MA derived from the non-Experiencer particle verb

afkeuren ‘reject/disapprove’, in (13). I take this as evidence that the participle in bare Dutch present participle MAs featuring a particle are adjectival, not verbal.

| (12) | Reinder zingt (*al) op-váll-end. |

| | Reinder sings prt prt-fall-ptcp |

| ‘Reinder sings in a striking manner.’ |

| (13) | Reinder schudt (*al) af-kéúr-end zijn hoofd. |

| | Reinder shakes al prt-approve-ptcp his head |

| ‘Reinder shakes his head disapprovingly/in a disapproving way.’ |

This finding about the structure of Dutch particle participles can be generalized to that of non-particle participles; as (14) shows, a Dutch participle MA with a particle can be coordinated with a Dutch participle MA without a particle. Under the assumption that only like categories/constituents can be coordinated (cf.

Broekhuis & Corver, 2019, sect. 1.3. for discussion), I take this as evidence that the participles in bare Dutch present participle MAs like

zingend and

lopend are also adjectival.

| (14) | Reinder spreekt hem (*al) zing-end en op-béúr-end toe. |

| | Reinder speaks him prt sing-ptcp and prt-bear-ptcp prt |

| ‘Reinder addresses him in a sing-song and encouraging way.’ |

Now, I turn to the syntactic properties of Dutch present participle MAs ending in -

erwijs. Two relevant facts are the following: first, -

erwijs participle MAs are ill-formed as attributive or predicative adjectives (as opposed to (some) bare Dutch present participles). This is seen in (15); compared to

zingende and

ontroerend (see (7a) and (8b)), neither

zingenderwijze nor

ontroerenderwijs are well-formed attributive/predicative adjectives, respectively. To me, this indicates that the adjectival present participle that forms part of Dutch -

erwijs MAs is part of a larger word-internal structure that is not adjectival as a whole.

6 In other words, Dutch -

erwijs participles contain an adjectival substructure but are not adjectives themselves, a conclusion

De Belder and Vanden Wyngaerd (

2024) reach as well. In my analysis in

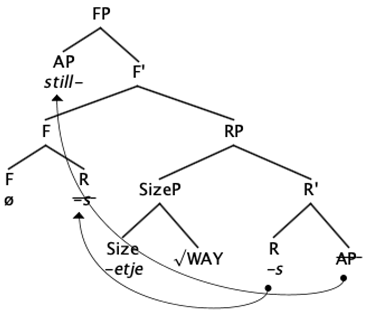

Section 3.3, I argue that the -

erwijs suffix gives evidence for this larger word-internal structure.

| (15) | a. | *de zing-end-erwijz-e detective |

| | | the sing-ptcp-ERWIJS-AGR detective |

| b. | *Dat argument is ontroer-end-erwijs. |

| | | that argument is move-ptcp-erwijs |

Second, as

De Belder and Vanden Wyngaerd (

2024) demonstrate, Dutch -

erwijs participles do not contain any verbal projections. They illustrate this using several tests for argument/event structure, due originally to

Alexiadou et al. (

2015), which indicate a total lack of related verbal projections. The tests and data they discuss are the following ((16–23) all taken from

De Belder & Vanden Wyngaerd, 2024, pp. 14–16): (16) shows that, in contrast to a bare present participle, the -

erwijs adverb

schreeuwenderwijs cannot control the null subject PRO of an infinitival clause. The ability to control PRO indicates that the bare present participle has an external argument; since it is able to control PRO, it must have a Voice projection hosting this external argument. Since the present participle marked with -

erwijs cannot control PRO, it must lack this projection.

| (16) | a. | Schreeuwend om PRO hulp te krijgen rende ze door de stad. |

| | | screaming to PRO help to receive ran she through the city |

| | | ‘Screaming to receive help she ran through the city.’ |

| b. | *Schreeuwend-erwijs om PRO hulp te krijgen rende ze door de stad. |

| | | screaming-erwijs to PRO help to receive ran she through the city |

(17) shows that, in contrast to a bare present participle, the -erwijs adverb zingenderwijs cannot be modified by the agentive adverb vrijwillig. Since agentive adverbs are contingent on an (implicit) external argument, this constitutes further evidence that the -erwijs marked present participle does not have an external argument.

| (17) | a. | Vrijwillig zingend liep ze door de stad. |

| | | voluntarily singing walked she through the city |

| | | ‘Voluntarily singing she walked through the city.’ |

| b. | *Vrijwillig zingend-erwijs liep ze door de stad. |

| | | voluntarily singing-erwijs walked she through the city |

In (18), we find the bare present participle passes another test for agentivity, which the -erwijs marked participle fails. The ability to license an instrumental adjunct is contingent on the presence of an external argument. This too indicates that the bare present participle has an external argument and that schreeuwenderwijs does not.

| (18) | a. | Schreeuwend met een megafoon liep ze door de stad. |

| | | shouting with a megaphone walked she through the city |

| | | ‘Shouting with a megaphone she walked through the city.’ |

| b. | *Schreeuwend-erwijs met een megafoon liep ze door de stad. |

| | | shouting-erwijs with a megaphone walked she through the city |

The anaphoric modifier vanzelf in (19) must be licensed by an Agent or Causer thematic role. Since the bare present participle can be modified by it, this indicates again that it has an external argument. Since brekenderwijs cannot be modified by it, this indicates a lack of external argument.

| (19) | a. | Vanzelf brekend zakte het ijs weg. |

| | | of.self breaking dropped the ice away |

| | | ‘Breaking by itself the ice fell through.’ |

| b. | *Vanzelf brekend-erwijs zakte het ijs weg. |

| | | of.self breaking-erwijs dropped the ice away |

In (20), we see that the bare present participle can select an object (in casu, the prepositional object tegen haar vader), which brullenderwijs cannot. This shows the bare present participle can host an internal argument, while the -erwijs marked participle cannot.

| (20) | a. | Brullend tegen haar vader rende zij het huis uit. |

| | | screaming at her father ran she the house out |

| | | ‘Screaming at her father she ran out of the house.’ |

| b. | *Brullend-erwijs tegen haar vader rende zij het huis uit. |

| | | screaming-erwijs at her father ran she the house out |

The test in (21) shows the event of the bare present participle spelend can be modified by the temporal adjunct urenlang. (21b) is ill-formed since spelenderwijs has no event for urenlang to modify. This indicates that the -erwijs participle does not have the verbal substructure responsible for projecting an event variable.

| (21) | a. | Urenlang spelend brachten de kinderen de zomer door op het strand. |

| | | for.hours playing brought the children the summer prt at the beach |

| | | ‘Playing for hours the children spent their summer at the beach.’ |

| b. | *Urenlang spelend-erwijs brachten de kinderen de zomer door op het strand. |

| | | for.hours playing-erwijs brought the children the summer prt at the beach |

In (22), we see that the incorporation of the noun

piano into the bare present participle

spelend is well formed, but that incorporation into

spelenderwijs is not. Since incorporation (along the lines of

Baker, 1988) is contingent on verbal structure, this indicates the bare present participle has verbal substructure, whereas the -

erwijs participle does not.

| (22) | a. | Pianospelend verleidde hij de Amerikaanse gast. |

| | | piano.playing seduced he the American guest |

| | | ‘Playing the piano he seduced the American guest.’ |

| b. | *Pianospelend-erwijs verleidde hij de Amerikaanse gast. |

| | | piano.playing-erwijs seduced he the American guest |

Finally, in (23), we see that bare present participles can be built on the basis of inherently reflexive verbs like zich schamen but not an -erwijs marked participle.

| (23) | a. | Zich schamend over zijn belabberde prestatie verliet de speler het veld. |

| | | rfl shaming about his dismal performance left the player the court |

| | | ‘Ashamed about his dismal performance, the player left the court.’ |

| b. | *Zich schamend-erwijs (over zijn belabberde prestatie) verliet de speler het veld. |

| | | rfl

shaming-erwijs about his dismal performance left the player the court |

Taken together, these tests show that -

erwijs participles lack the verbal projections that bare present participles have. What

De Belder and Vanden Wyngaerd (

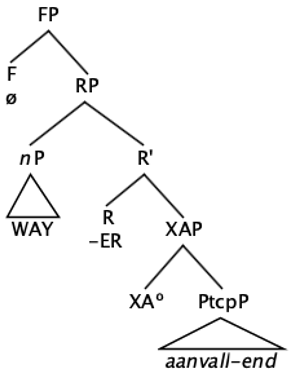

2024) do not discuss (presumably because it is not the focus of their inquiry) is that the bare present participles in the (a) examples in (16–23) are not MAs. This can be shown on the basis of stress patterns on bare participles of particle verbs under the same tests. As (24–29) show, the same tests for agentivity, external and internal arguments, and eventivity only yield well-formed results if stress falls on the particle of the bare present participle and yield ill-formed results if stress falls to the right of the particle.

7| (24) | a. | Áán-vallend

om PRO de overwinning binnen te slepen, bestormde de menigte het kasteel. |

| | | prt-falling to PRO the victory inside to drag stormed the crowd the castle |

| | | ‘Attacking in order to secure victory, the crowd stormed the castle.’ |

| b. | *Aan-vállend om PRO de overwinning binnen te slepen, bestormde de menigte het kasteel. |

| (25) | Context: in a game of chess, the grandmaster makes an unforced move (i.e., the move is not forced because she is in check). A reporter reports the move as follows: |

| a. | Vrijwillig áán-vallend sloeg de grootmeester een stuk van wit. |

| | | voluntarily prt-falling struck the grandmaster a piece of white |

| | | ‘Voluntarily attacking, the grandmaster takes a piece of the white player.’ |

| b. | *Vrijwillig aan-vállend sloeg de grootmeester een stuk van wit. |

| (26) | a. | Áán-vallend met een paard nam de grootmeester een groot risico. |

| | | prt-falling with a horse took the grandmaster a great risk |

| | | ‘Attacking with a knight, the grandmaster took a big risk.’ |

| b. | *Aan-vállend met een paard nam de grootmeester een groot risico. |

| (27) | Context: in a series of test matches with a grandmaster, a new chess computer is tested in various modes. At first, the computer is programmed never to take a piece without consulting its programmer about the move and loses. In a second match, the computer plays without this constraint, gets to take pieces by itself, and wins. A reporter says the following: |

| a. | Vanzelf áán-vallend won de computer de partij in zes zetten. |

| | | of.self prt-falling won the computer the match in six moves |

| | | ‘Attacking by itself, the computer won the match in six moves.’ |

| b. | *Vanzelf aan-vállend won de computer de partij in zes zetten. |

| (28) | a. | Elkaar áán-vallend zetten ze de discussie voort. |

| | | each.other prt-falling put they the discussion prt |

| | | ‘They continued the discussion attacking each other.’ |

| b. | *Elkaar aan-vállend zetten ze de discussie voort. |

| (29) | a. | Urenlang áán-vallend boekte de menigte vooruitgang in de richting van het kasteel. |

| | | for.hours prt-falling booked the crowd progress in the direction of the castle |

| | | ‘Attacking for hours, the crowd made progress in the direction of the castle.’ |

| b. | *Urenlang aan-vállend boekte de menigte vooruitgang in de richting van het kasteel. |

To demonstrate that

aanvallend is well formed as an MA in the first place (and that the (b) examples in (24–29) are thus not ill-formed because

aanvallend is ill-formed as an MA in general), see (30); the ill-formedness of

al demonstrates that, of the two possible guises of the Dutch bare present participle, we are dealing here with the MA one. Note that if the bare present participle bears stress on the particle, it combines perfectly with

al (see (31)), which only combines with temporal present participles, as we have seen in

Section 2.1.

| (30) | De man sprak de vrouw (*al) aan-vállend toe. |

| | the man spoke the woman prt prt-falling prt |

| | ‘The man addressed the woman aggressively.’ |

| (31) | De man sprak de vrouw al áán-vallend toe. |

| | the man spoke the woman prt prt-falling prt |

| | ‘The man addressed the woman while attacking.’ |

I take the data in (24–29), combined with (30–31), to show that bare temporal present participle adverbials with a particle are structurally distinct from bare present participle MAs: Dutch present participles yield grammatical examples under the various tests for verbal substructure only with a stress pattern that bare present participle MAs with particles cannot have (as discussed above in (12–13)). On the contrary, with the stress pattern found on bare present participle MAs with particles, they yield ungrammatical examples under the same tests across the board. Furthermore, al, as another diagnostic that distinguishes between present participles with manner and temporal readings, combines to form a well-formed result only with a bare present participle if stress falls on its particle, and not to the right of it, showing this diagnostic is sensitive to the differences in the underlying structure of Dutch present participle adverbials as made apparent by their stress pattern.

These data show that Dutch bare present participle MAs with particles do not have verbal substructure and that the bare present participle forms of particle verbs that pass

De Belder and Vanden Wyngaerd (

2024)’s tests thus are not MAs. Since there is reason to believe that Dutch bare present participles without particles do not differ relevantly from those with particles (recall the coordination data in (14) that suggest they form structurally parallel constituents), I conclude that Dutch bare present participle MAs in general lack a verbal substructure.