2. Verb Classes and the EC/LC Distinction

An LC is typically composed of posture verbs (such as

nằm ‘lie’,

ngồi ‘sit’, and

đứng ‘stand’), verbs of placement (such as

đặt ‘place’,

để ‘put, place’, and

treo ‘hang’) and dwell verbs (such as

ở and

sống ‘dwell’) as exemplified by (3).

| (3) | Trên | bàn | nằm/ | để | một | chồng | sách. |

| | on | table | lie | put | a | pile | book |

| | ‘On the table lies / is put a pile of books.’ |

These verbs must be used in their stative sense in LC, not their change-of-state sense, exhibiting “informational lightness” in the sense of

Birner (

1992). This property explains why LC is sometimes found accompanied by manner adverbs such as

lăn lóc ‘in a disordered/scattered manner’ and

lủng lẳng ‘in a dangling manner’ as in (4a) and (4b), respectively. These manner adverbs are incompatible with the dynamic/change-of-state interpretation of these verbs.

2| (4) | a. | Trên | mặt | bàn | nằm | lăn lóc | mấy | vỏ | chai | bia | 33.3 |

| | | on | surface | table | lie | disorderly | several | shell | bottle | beer | 33 |

| | | ‘On the table lie several empty “33” beer bottles in a disorderly manner.’ |

| | b. | Dọc theo | lan can | đò | treo | lủng lẳng | một số | áo phao.4 | |

| | | along | railing | boat | hang | danglingly | some | life.jacket | |

| | | ‘Along the railing of the boat hang several life jackets in a danglingly manner.’ |

Collectively referred to as locative verbs here, the verbs forming LC are intrinsically tied to a location, necessitating subcategorization for a locative phrase. The subcategorization requirement of the locative verbs can be jointly evidenced by the obligatory occurrence of the locative phrase in (5) and (6). First, (5) shows that an LC is grammatical only with the overt realization of the locative phrase. Next, although (6) indicates that the locative phrase can stay in situ within the VP hosting the locative verb when the theme DP moves to Spec,TP, its presence within VP is mandatory.

| (5) | The clause-initial locative phrase is obligatory in LC: |

| | *(Trên | bàn) | nằm | một | chồng | sách. | |

| | on | table | lie | a | pile | book | |

| (6) | The locative phrase is a core argument of the locative verb: |

| | Một | chồng | sách | nằm | *(trên | bàn.) | |

| | a | pile | book | lie | on | table | |

| | ‘A pile of books lies *(on the table).’ | |

On the other hand, an EC typically goes with verbs of existence, which denote general existence and duration, such as

có ‘exist’ and

còn ‘remain’ as in (7).

5 In principle, (7) allows two interpretations: it can be interpreted as a generic statement asserting the presence of water in general or as a contextualized statement asserting the presence of water in the specific speech context. Importantly, an EC remains grammatical without the overt presence of a clause-initial locative phrase, in contrast to (5). In addition, an EC allows both the theme DP and the locative phrase to appear post-verbally, as in (8). See the contrast between (8a) and its corresponding LC in (9).

| (7) | The locative phrase is optional in EC: |

| | Có/ | còn | nước. |

| | exist | remain | water |

| | ‘There is/ remains water.’ |

| (8) | EC allows a post-verbal locative phrase: |

| | a. | Có | một | chồng | sách | trên | bàn. |

| | | exist | a | pile | book | on | table |

| | | ‘There is a pile of books on the table.’ |

| | b. | Xuất hiện | băng | tuyết | tại | huyện | Bình Liêu, | Quảng Ninh.6 |

| | | appear | ice | snow | at | district | B.L. | Q.N. |

| | | ‘There appeared frost snow in Binh Lieu District of Quang Ninh Province.’ |

| (9) | *Nằm | một | chồng | sách | trên | bàn. | |

| | lie | a | pile | book | on | table | |

| | Intended: ‘There lied a pile of books on the table.’ | |

In view of the contrast between LC and EC with respect to the requirement of an overt locative phrase, we assume that the locative phrase is a core argument of the locative verb in LC (cf.

Bresnan, 1994), while that in EC is a locative adjunct. Thus, we argue that the locative argument in LC is not base-generated in the clause-initial position as in (1). Rather, it is base-generated within VP as in (10). The derivation starting from the base structure in (10) may be followed by moving either the locative argument or the theme DP, resulting in (1) and (6), respectively.

7,8| (10) | The base structure of LC: |

| | [CP …… [vP v [VP DP V LP ]]] |

An alternative hypothesis assumes that the locative argument is base-generated at a position structurally higher than the theme DP in LC. This alternative poses a theoretical problem with respect to

Baker’s (

1997) Uniformity of Theta Assignment Hypothesis (UTAH): the locative phrase bears the oblique theta-role of Location, which should be lower than the Theme argument according to the UTAH’s hierarchy in (11) (cf.

Wu, 2008).

| (11) | Agent > Theme > Goal > Obliques (manner, location, time) |

We offer two more arguments for our proposal in (10) regarding the subcategorization requirement of the locative verbs forming LC. The first argument is related to the selectional restrictions of locative verbs in LC. If the locative phrase is an argument of the locative verb in LC, there should be a c-selection restriction on the kind of locative information that is permitted in LC. This prediction is borne out, as only locative phrases denoting a specified location via the use of a localizer are felicitous, while more general locations without a localizer are odd in LC, as in (12b). The contrast in (12) suggests that the locative verb in LC imposes a c-selection requirement on its locative argument. We assume that the c-selection requirement in (12) follows from the argument status of the locative phrase in LC.

| (12) | The localizer is necessary in LC: |

| | a. | Trong | công viên | ngồi | một | cụ già. | |

| | | in | park | sit | one | old.person | |

| | | ‘In the park sits an old person.’ |

| | b. | ??/*Công viên | ngồi | một | cụ già. | | |

| | | park | sit | one | old.person | | |

| | | Intended: ‘At the park sits an old person.’ |

By contrast, the locative information in EC can but does not need to be realized by a locative phrase, as shown in (13). Consequently, EC can express either a specified location as in (13a) or a general location in (13b) (which can be contextually determined).

| (13) | The localizer is optional in EC: |

| | a. | Trong | công viên | có / | xuất hiện | một | cụ già. |

| | | in | park | exist | appear | one | old.person |

| | | ‘In the park there is/ appears an old person.’ |

| | b. | Công viên | có / | xuất hiện | một | cụ già. |

| | | park | exist | appear | one | old.person |

| | | ‘At the park there is/ appears an old person.’ |

The second argument concerns the insertion of temporal adverbials or tense/aspectual markers in EC/LC. Specifically, note that although the locative phrase is optional in EC in (7), EC is most natural with some sort of overt temporal/locative anchoring.

9 In the absence of a locative phrase, the anchoring of EC can be achieved via temporal adverbials or tense/aspectual markers, as in (14) and (15), respectively.

| (14) | Anchoring of EC via temporal adverb(ial)s: |

| | a. | Sáng | nay | xuất hiện | một | bệnh nhân. | | | | | |

| | | morning | this | appear | one | patient | | | | | |

| | | ‘There appeared a patient this morning.’ |

| | b. | Hôm qua | rơi | nhiều | tuyết. | | | | |

| | | yesterday | fall | a.lot | snow | | | | |

| | | ‘Yesterday fell a lot of snow.’ |

| (15) | Anchoring of EC via tense/aspectual markers: |

| | a. | Vừa | đến | một | bệnh nhân. | | | | | | |

| | | just | arrive | one | patient | | | | | | |

| | | ‘A patient just arrived.’ |

| | b. | Đang | tan | nhiều | tuyết. | | | | |

| | | prog | melt | a.lot | snow | | | | |

| | | ‘A lot of snow is melting.’ |

However, temporal adverb(ial)s and tense/aspectual markers cannot salvage an LC without a locative phrase, as evidenced by (16). Again, the ungrammaticality of (16) highlights the necessity of the overt presence of a locative phrase in LC.

| (16) | a. | *Sáng | nay | nằm | một | bệnh nhân. | | | | | |

| | | morning | this | lie | one | patient | | | | | |

| | | Intended: ‘This morning lied a pile of books.’ |

| | b. | *Vừa | nằm | một | chồng | sách. | | | |

| | | just | lie | one | pile | book | | | |

| | | Intended: ‘Just lied a pile of books.’ |

In summary, the optional presence of a locative phrase in existential constructions (EC), as shown in examples (7), (14), and (15), supports its status as an adjunct. In contrast, the predicates forming an LC require a locative argument, as demonstrated by the grammatical occurrence of the locative phrase within the VP in (6), the c-selection requirement in (12), and the mandatory inclusion of the locative phrase in (16). This distinction highlights the subcategorization differences between EC and LC with regard to the locative phrases.

3. The Raising of the Locative Argument in LC

Given the conclusion established in the previous section, note that adding the locative phrase at the post-verbal position, as in (17), does not save (16).

| (17) | a. | *Sáng | nay | nằm | một | chồng | sách | trên | bàn. | | |

| | | morning | this | lie | one | pile | book | on | table | | |

| | | Intended: ‘This morning lied a pile of books on the table.’ |

| | b. | Vừa | nằm | một | chồng | sách | trên | bàn. | |

| | | just | lie | one | pile | book | on | Table | |

| | | Intended: ‘Just lied a pile of books on the table.’ |

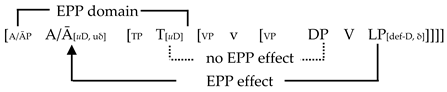

The ungrammaticality of (17) indicates that the locative argument of the locative verb has to raise out of the vP domain to construct a grammatical LC. Now, the question comes down to the landing site of the movement of the locative argument in LC. Two avenues can be envisaged to identify the nature of the position(s) targeted by the fronting locative argument in LC, as shown in (18): it raises either to the canonical subject position Spec,TP, or to a syntactic position other than Spec,TP.

| (18) | Possible analyses of the movement of the locative phrase in LC: |

| | a. | It targets Spec,TP, |

| | b. | It raises to a position other than Spec,TP. |

The possibility in (18a) encounters two analytical challenges. The first challenge concerns the minimality of the movement. In particular, suppose the raising to Spec,TP is triggered by the satisfaction of a D-feature on T in Vietnamese as in (19); the raising of the locative argument to Spec,TP across the theme DP runs afoul of the relativized minimality constraint (

Rizzi, 1990). This is due to the fact that both the locative argument and the theme DP can grammatically occupy this position according to the hypothesis in (18a); however, the theme DP is situated closer to T than the locative argument. This raises the question of how the locative argument can move to Spec,TP, surpassing the theme DP, which typically occupies that position.

| (19) | ![Languages 10 00050 i001]() |

Second, if we assume that vP is a phase (

Legate, 2003), the locative phrase may move to the edge of the vP phase to become a closer goal to T than the theme DP is, as in (20). However, given that this type of raising to the phase edge is typically considered as an instance of Ā-movement, it is unclear how a subsequent raising to Spec,TP (as a canonical instance of A-movement triggered by D/φ-features) in (20) circumvents the constraint on improper movement which prohibits an Ā-A sequence of derivation (

May, 1979;

Chomsky, 1981;

Abels, 2007;

Neeleman & Van De Koot, 2010;

Williams, 2011).

| (20) | ![Languages 10 00050 i005]() |

Due to the minimality issue in (19) and the ban on improper movement in (20), we do not assume that the locative argument in LC raises to Spec,TP. In

Section 4, we will see an additional empirical problem of the hypothesis in (18a): the raising of the theme DP and that of the locative argument in LC exhibit different semantic/pragmatic properties in terms of specificity.

10Given the challenges facing (18a), we pursue the possibility in (18b) to derive the fronting of the locative argument in LC. Our discussion of (18b) focuses on the relative order of the fronting locative argument and two elements: the complementizer in the left periphery and the expletive

nó in the high TP-domain (

Greco et al., 2017,

2018). We discuss the relative order with the complementizers

là and

rằng in this section. Note that the locative adjunct in EC may either precede or follow the complementizers

là as in (21).

| (21) | a. | Rõ ràng | là | trên | giường | có | một | bệnh nhân. | | | |

| | | clearly | c | on | bed | exist | a | patient | | | |

| | | ‘Clearly on the bed there is a patient.’ |

| | b. | Trên | giường | rõ ràng | là | có | một | bệnh nhân. | |

| | | on | bed | clearly | c | exist | a | patient | |

| | | ‘On the bed there clearly is a patient.’ |

Phan (

2024) observes that the complementizer

là can occur in main clauses only if it is immediately preceded by CP-level sentential mood and modal markers such as the evidential phrases

rõ ràng ‘clearly’ and

hình như ‘seemingly’. He proposes that

là heads the Finiteness Phrase, marking the lowest bound of the Split-CP

à la Rizzi (

1997), and is licensed by these sentential mood/modal items. The grammaticality of the pair in (21) with respect to the relative order with

là indicates that the locative adjunct in EC is adjoined TP-internally in (21a)

11 and may undergo optional topicalization to the left periphery above the FinP in (21b). Note that the locative adjunct is not inherently a topic. The non-topical nature of the locative adjunct in EC can be evidenced by its occurrence in out-of-the-blue contexts as a felicitous reply to a global ‘what-happened’ question as in (22a), unlike the topicalized variation in (22b) (see

Rizzi, 2004;

Belletti & Rizzi, 2017).

| (22) | Q: | Chuyện | gì | vậy? | | | | |

| | | matter | what | sfp | | | | |

| | | ‘What happened?’ |

| | a. | Trên | bàn | có/ | xuất hiện | một | chồng | sách. |

| | | on | table | exist | appear | a | pile | book |

| | | ‘On the table there is/ appears a pile of books.’ |

| | b. | #Trên | bàn | thì | có/ | xuất hiện | một | chồng | sách. | | |

| | | on | table | top | exist | appear | a | pile | book | | |

Similarly, notice that the position of locative adjunct in relation to

là has a crucial effect on the grammaticality of the insertion of the topic marker, as shown by (23). The insertion of the topic marker

thì is allowed only when the locative adjunct precedes the complementizer, as in (23a), suggesting that the topic marker is available only for topic expressions moving to the left periphery.

| (23) | The topic marker thì is available only for a topicalized phrase: |

| | a. | Trên | giường | thì | có lẽ/ | rõ ràng | là | có | một | bệnh nhân. | |

| | | on | bed | top | perhaps | clearly | c | exist | a | patient | |

| | | ‘Perhaps/ clearly on the bed there is a patient.’ |

| | b. | *Có lẽ/ | rõ ràng | là | trên | giường | thì | có | một | bệnh nhân. | |

| | | perhaps | clearly | c | on | bed | top | exist | a | patient | |

On the other hand, the pair in (24) shows that an LC sounds degraded if the locative argument precedes the head of FinP and its licensers but not when it follows them, in contrast to (21).

12 This suggests that the fronting of the locative argument in LC lands below CP and cannot keep moving to CP-level projections such as the Topic Phrase.

| (24) | a. | Rõ ràng | là | trên | giường | nằm | một | bệnh nhân. | | | |

| | | clearly | c | on | bed | lie | a | patient | | | |

| | | ‘Clearly on the bed lies a patient.’ |

| | b. | ??Trên | giường | rõ ràng | là | nằm | một | bệnh nhân. | | | |

| | | on | bed | clearly | c | lie | a | patient | | | |

| | | Intended: ‘On the bed there clearly lies a patient.’ |

Our analysis of the locative phrases in LC and EC occupying different syntactic positions can be further supported by the insertion of the topic marker

thì in Vietnamese. Note that the fronting locative argument in LC cannot be followed by the topic marker

thì as in (25a), while the locative adjunct in EC is not subject to this constraint as in (25b).

13 The contrast between (25a) and (25b) clearly indicates that the fronting of the locative argument in LC is not an instance of Ā-topicalization to the left periphery.

14 Moreover, the ungrammaticality of (17) indicates the obligatory character of the fronting of the locative argument in LC, which is incompatible with the optionality of Ā-topicalization in general. This incompatibility makes an Ā-topicalization analysis of the fronting locative argument in LC difficult to maintain.

| (25) | a. | *Trên | giường | thì | nằm | một | bệnh nhân. | (LC) |

| | | on | bed | top | lie | a | patient | |

| | | Intended: ‘On the bed is lying a patient.’ |

| | b. | Trên | giường | thì | có | một | bệnh nhân. | (EC) |

| | | on | bed | top | exist | a | patient | |

| | | ‘On the bed there is a patient.’ |

Another argument against the Ā-topicalization analysis of the fronting locative argument in LC concerns hyperraising. Several languages have been demonstrated to allow for A-movement from the subject position out of a finite CP, which is referred to as hyperraising since

Ura (

1994). Hyperraising can be demonstrated by Zulu in (26), where the subject DP

Zinhle of the embedded predicate

xova ”make” moves out of the finite CP complement across the matrix raising predicate

bonakala “seem” (see also

Ferreira, 2000,

2004,

2009;

Rodrigues, 2004;

Martins & Nunes, 2005,

2009,

2010;

Nunes, 2008;

Deal, 2017;

Fong, 2019;

Zyman, 2023).

| (26) | Hyper-raising in Zulu: (Halpert, 2019, ex.3b) |

| | uZinhle1 | u-bonakala | [CP | ukuthi ___1 | u-zo-xova | ujeqe]. |

| | aug.1.Zinhle | 1s-seem | | that | 1s-fut-make | aug.1steamed.bread |

| | ‘It seems that Zinhle will make steamed bread.’ |

Lee and Yip (

2024) argue that hyper-raising exists in Vietnamese in constructions involving (raising) attitude verbs such as

nghe nói ‘hear’, as exemplified by (27b) (see their

Section 3 for evidence for an A-movement analysis of (27b) and the finiteness of the CP complement).

| (27) | Hyperraising in Vietnamese: |

| | a. | Nghe nói | [CP | rằng/ là | cơn | mưa | này | sẽ | không | dừng.] |

| | | hear | | c | cl | rain | this | fut | not | stop |

| | | ‘It is heard that the rain will not stop.’ |

| | b. | Cơn | mưa | này | nghe nói | [CP | rằng/ là | sẽ | không | dừng.] |

| | | cl | rain | this | hear | | c | fut | not | stop |

| | | ‘It is heard that the rain will not stop.’ (adapted from Lee & Yip, 2024, p. 3) |

What makes hyperraising relevant to our discussion is that LC is allowed to occur in the complement clause of

nghe nói, as shown by (28a). More importantly, the locative argument is allowed to move out of the complement clause as in (28b).

15| (28) | Hyperraising of the locative argument: |

| | a. | Nghe nói | [CP | rằng/ là | [trên | giường] 1 | nằm | một | bệnh nhân. | t1.] |

| | | hear | | c | on | bed | lie | one | patient | |

| | | ‘It is heard that on the bed lies a patient.’ |

| | b. | [Trên | giường]1 | nghe nói | [CP | rằng/ là | nằm | một | bệnh nhân. | t1.] |

| | | on | bed | hear | | c | lie | one | patient | |

| | | ‘It is heard that on the bed lies a patient.’ |

Notice that the movement of the locative argument in (28b) cannot be analyzed as Ā-topicalization, as evidenced by the ungrammaticality of the insertion of

thì (the marker of the Topic head in the left periphery) in (29).

16| (29) | *[Trên | giường]1 | thì | nghe nói | [CP | rằng/ là | nằm | một | bệnh nhân. | t1.] |

| | on | bed | top | hear | | c | lie | one | patient | |

| | Intended: ‘It is heard that on the bed lies a patient.’ |

The hyperraising of the locative argument lends further support to our analysis that the fronting of the locative argument in LC cannot be analyzed as Ā-topicalization. If the fronting of the locative argument in LC were Ā-topicalization, the subsequent A-movement of hyperraising in (28b) would constitute a violation of the ban on improper movement, which prohibits an Ā-A sequence of derivation (

May, 1979;

Chomsky, 1981;

Abels, 2007;

Neeleman & Van De Koot, 2010;

Williams, 2011).

17Given the resistance of topic marking by

thì shown in (25a), one may assume that the movement of the locative argument in LC can be analyzed as an A-movement. Aside from functioning as the grammatical subject in LC, the raising of the locative argument does not show a Weak Crossover effect (WCO) as in (30), indicating a typical feature of A-movement (see

Culicover & Levine, 2001, pp. 289–290 for the same line of reasoning regarding the A-property of English locative inversion).

18| (30) | [Trên | giường | của | mỗi | đứa | trẻ2]1 | đều | để | [sách | của | nó2 | t1]. |

| | on | bed | poss | each | cl | child | all | place | book | poss | he | |

| | ‘On every child2’s bed are placed his2 books.’ |

Although the raising locative argument in LC resists overt topic marking by

thì in (25a) and does not exhibit WCO

19, it aligns with an Ā-topicalized phrase with respect to topic island effects and the specificity requirement of indefinite nominals. Let us begin with the topic island effects. It is well-known that locative inversion in English parallels Ā-topicalization in inducing island effects that block

wh-movement, as illustrated in (31a) and (31b/c), respectively. This parallelism has been cited to support the Ā-properties of English locative inversion (

Bresnan, 1994, p. 87;

den Dikken, 2006, p. 100;

Rizzi & Shlonsky, 2006, p. 344).

| (31) | Topic island effects: |

| | a. *Wheni did he say that into the room walked Jack ti? |

| | b. *When1 did to Lee Robin give the pencil t1? |

| | c. *When1 did this book everyone read t1? |

The same reasoning can be applied to demonstrate the Ā-properties of the fronted locative phrase in LCs. Since Vietnamese is a

wh-in-situ language, Ā-focalization, as shown in (32a), is employed to construct the relevant argument. Notably, the Ā-topicalization of the locative adjunct in ECs blocks Ā-focalization, as illustrated in (32b).

| (32) | a. | Là | [sách ngôn ngữ học]1 | Tí nghĩ [CP rằng có [một chồng t1] trên bàn]. |

| | | foc | book linguistics | Tí think c exist a pile on table |

| | | Literal: ‘It is linguistics books that Tí thinks there is a pile of on the table.’ |

| | b. | *Là | [sách ngôn ngữ học]1 | Tí nghĩ [CP rằng [trên bàn]2 có [một chồng t1] t2]. |

| | | foc | book linguistics | Tí think c on table exist a pile |

| | | Intended: ‘It is linguistics books that Tí thinks on the table is a pile of.’ |

Crucially, the fronting of the locative argument in LCs similarly induces a topic island effect, as shown in (33). The parallelism between (32b) and (33) indicates that the fronting of the locative phrase in LCs and ECS, though targeting different structural positions, exhibits the same Ā-property in terms of the topic island effects.

| (33) | The fronting locative argument in LC creates a topic island: |

| | *Là | [sách | ngôn ngữ học]1 | Tí | nghĩ | [CP rằng [trên bàn]2 | nằm | [một chồng t1] t2]. |

| | foc | book | linguistics | Tí | think | c on table | lie | a pile |

Next, we turn to the argument concerning the specific reading for indefinite nominals. Note that nominal phrases that feature the indefinite article

một ‘a/an’ followed by a classifier-noun sequence allow both a specific and a nonspecific/generic interpretation (see also

Phan & Chierchia, 2022;

Enç, 1991). For instance, the subject

một bệnh nhân ‘a patient’ in (34) is allowed either a specific reading or a nonspecific/generic reading. The two possible interpretations of an indefinite NP with

một can be further demonstrated by the two possible continuations in (35a) and (35b) (see

Fodor & Sag, 1982, p. 355;

Von Heusinger, 2002, p. 245).

| (34) | Một | bệnh nhân | nằm | trên | một | cái | giường. | |

| | a | patient | lie | on | A | cl | bed | |

| | a. | ‘A specific patient lies on a bed.’ | (specific) |

| | b | ‘A/any patient lies on a bed.’ | (nonspecific/generic) |

| (35) | Một | sinh viên | lớp | Cú pháp | gian lận | trong | giờ | thi. |

| | a | student | class | syntax | cheat | in | time | test |

| | ‘A student in Syntax cheated on the exam.’ |

| | a. | Tên | sinh viên | đó | là | Tí. | (specific) | |

| | | name | student | that | be | Tí | | |

| | | ‘The student’s name is Tí.’ |

| | b. | Chúng tôi | đang | điều tra | xem | đó | là | ai. | (nonspecific) | |

| | | we | prog | investigate | see | that | be | who | | |

| | | ‘We are trying to figure out who it was.’ |

Notice that the specificity ambiguity of indefinite nominals disappears under Ā-topicalization as in (36) because topics display definiteness/specificity effects (

Enç, 1991;

Erteschik-Shir, 1997, a.o.).

20 Similarly,

Phan and Lander (

2015, fn.3) suggest that topicality is a function of specificity (cf.

Cresti, 1995;

Portner, 2002) and that the topic particle

thì is one of the specificity markers in Vietnamese. Thus, the topicalized indefinite nominal marked by

thì in (36) receives only the specific reading.

| (36) | A topicalized indefinite nominal must receive a specific reading: |

| | Context: Professor A is telling about his three favorite students… |

| | Một | sinh viên | thì | rất | giỏi | cú pháp. | |

| | a | student | top | very | good | syntax | |

| | ‘As for one student, s/he is really good at syntax.’ (specific/*nonspecific/*generic) |

The specificity ambiguity of indefinite nominals is carried over to locative phrases containing indefinite NPs, as demonstrated by (37). When the locative phrase containing an indefinite NP stays within vP as in (37), it patterns with the indefinite NPs in (34)/(35) in displaying ambiguity with respect to specificity.

| (37) | Một | bệnh nhân | nằm | trên | một | cái | giường. | |

| | a | patient | lie | on | a | cl | bed | |

| | a. | ‘A patient lies on a specific bed.’ | (specific) |

| | b | ‘A patient lies on a/any bed.’ | (nonspecific/generic) |

Importantly, the ambiguity in (37) disappears when the locative phrase is fronted as in (38): the fronted LP is necessarily interpreted as being specific, relating to a specific bed in the speaker’s mind. This specific spatial coordinate helps anchor the eventuality reported in the LC to a specific context.

| (38) | Trên | một | cái | giường | nằm | một | bệnh nhân. | |

| | on | a | cl | bed | lie | a | patient | |

| | a. | ‘On a specific bed lies a patient.’ | (specific) |

| | b | #‘On a/any bed lies a patient.’ | (*nonspecific/*generic) |

Now, we encounter a dilemma in the analysis of the trigger of the movement of the locative argument in LC. On the one hand, the fronting locative argument in LC patterns with a topicalized phrase in terms of the topic island effects and the specificity requirement of indefinite nominals. On the other hand, the fronting locative argument resists the topic marker thì and does not show WCO. How do we capture the fact that the movement of the locative argument, though not a case of Ā-topicalization to the left periphery, exhibits the specificity requirement seen in Ā-topicalization? What makes this problem trickier is the contrast between (34) and (38). The indefinite subject NP in the categorical sentence in (34) allows either a nonspecific/generic or a specific reading, while the fronted locative argument in (38) permits only a specific interpretation. This contrast indicates that the movement of the indefinite subject NP in (34) and that of the locative argument in LC in (38) are driven by two distinct motivations and target different syntactic positions such that only the former retains the specificity ambiguity of an indefinite NP.

Summing up, the ungrammaticality of (25a), the contrast in (23)/(24), and the grammatical hyperraising of the locative argument in (28b) corroborate our analysis that the fronting locative argument in LC stays below the CP level (more precisely, the FinP headed by the complementizer

là), whereas the locative adjunct in EC may undergo optional topicalization to the left periphery. Thus, the fronting locative argument does not target Spec,TP, and it cannot be analyzed as Ā-topicalization. Now the question is where exactly in the high TP-domain the fronting locative argument in LC moves to. In the next section, we propose that the locative argument in LCs moves to the specifier position of a hybrid A/Ā-projection in the high TP-domain extensively investigated by

Bošković (

2024a). Our proposal will be empirically corroborated by the similarities of the locative argument in LCs and the non-referential expletive

nó (lit. ‘it’) in Vietnamese.

6. Conclusions

The hybrid A/Ā properties of English locative inversion present a notable analytical challenge within the generative framework. For instance,

Bresnan (

1994) argues that English locative inversion cannot be adequately derived within Chomsky’s generative framework, which posits that all human languages utilize universal syntactic operations on underlying structures (see also

Postal, 2004). Two major analytical challenges posed by English locative inversion are (i) why the fronting locative phrase does not behave as a canonical subject (e.g., lack of agreement; see

Bruening, 2010 for further discussion), and (ii) how the movement of the locative phrase, if analyzed as an instance of A-movement targeting Spec,TP, is able to move across the structurally higher theme DP, which canonically does so. To address these puzzles, some researchers have proposed a null expletive analysis, suggesting that Spec,TP is occupied by a null expletive, with the locative phrase undergoing Ā-topicalization (e.g.,

Postal, 1977,

2004;

Maruta, 1985;

Coopmans, 1989;

Hoekstra & Mulder, 1990;

Bruening, 2010).

In this paper, we demonstrate that the null expletive analysis cannot be extended to account for the derivation of LC in Vietnamese. Specifically, the fronting locative argument in LC resists marking by

thì, representing the Topic head in the left periphery (see (25a)). Moreover, the postulation of a null expletive in Vietnamese is implausible in light of the incompatibility of LC and the expletive

nó (see (45)). After establishing that the null expletive analysis is unsuitable for LC in Vietnamese (see

Diercks, 2017 for cross-linguistic considerations), we explore parallels between the fronting locative argument and the expletive

nó with regard to their shared specificity requirement (see

Section 4.2). These findings lead us to a dilemma: the fronting locative argument in LC is not a topic in the left periphery, yet it patterns with the expletive

nó regarding the specificity requirement, a property that is aligned with Ā-topicalization. We suggest a solution based on three assumptions. First, we adopt

Bošković’s (

2024a) proposal of three distinct subject positions between TP and CP across languages and argue that both the fronting locative argument and

nó target the specifier position of the A/ĀP, the uppermost of these subject positions. Second, to clarify the derivational process of locative inversion in LC, we adopt the featural characterization of the A/Ā-distinction (

Obata & Epstein, 2011;

Van Urk, 2015;

Fong, 2019) and assume a composite probe [D, δ] on the head of the A/ĀP. Finally, we show that

Coon and Bale’s (

2014) formal calculus of minimality enables the composite probe to target and move the locative argument to Spec,A/ĀP over the structurally higher theme DP, achieving the desired derivation.