1. Introduction

The inspiration and starting point for the current paper is an important, extensive study of anaphora in Vietnamese by

Đoàn (

2022):

Anaphoric dependencies in Vietnamese–a syntactic approach. In this work, Đoàn describes how the anaphor

mình is frequently paired with a pre-verbal reflexivizing morpheme,

tự, and presents the claim in (1):

| (1) | ‘… the anaphor mình cannot be locally bound unless accompanied by the element tự.’ |

| | (Đoàn, 2022, p. 114). |

An illustration of this restriction is shown in (2) below. In (2a),

tự is not present, and a reflexive interpretation between the subject and object of the embedded clause is not available—though a long-distance anaphoric relation is possible between

mình and the subject of the higher clause.

1 In (2b), by way of contrast,

tự occurs in the embedded clause, and this is shown to enable (and also force) a reflexive interpretation between

mình and the subject of the embedded clause.

| (2) | a | Nami | nghĩ | Lank | ngưỡng mộ | mìnhi/*k. |

| | | Nam | think | Lan | admire | body. |

| | | ‘Nam thinks Lan admires him/*herself.’ |

| | b | Nami | nghĩ | Lank | tự | ngưỡng mộ | mình*i/k. |

| | | Nam | think | Lan | tu | admire | body. |

| | | ‘Nam thinks Lan admires *him/herself.’ (Đoàn, 2022, p. 3) |

A consideration of the broader patterning of

mình might seem to suggest, however, that the characterization in (1) is actually too strict. Examples can regularly be found where

mình is used to refer back to a local subject without the accompaniment of

tự, as in (3):

2| (3a) | Mịch | rất | hối hận | giận | mình | sao | đã | quá | thật thà |

| | Mich | very | regret | mad | REFL | why | PST | too | honest |

| | đến nỗi | thú thật | với | Long | là | đi | ăn trộm. |

| | that | confess | with | Long | is | go | stealing. |

| | ‘Mịch deeply regretted angering herself for being so honest that she confessed to Long about stealing.’ |

| | Source: Giông tố (1936). Vũ Trọng Phụng. Tuyển tập Vũ Trọng Phụng, tập 1. Nhà xuất bản Văn học, Hà Nội, 1996. |

| (3b) | Cô | cố | giấu | mình | giữa | đám đông đảo | ồn ào. |

| | She | try | hide | REFL | middle | crowd | loud. |

| | ‘She tried to hide herself in the noisy crowd.’ |

| | Source: Thời xa vắng. Lê Lựu. |

| (3c) | Còn | lão | Hứng | thất kinh | sinh ra | hành tội | con mèo | vô tội |

| | As | old | Hung | terrified | so | frustrate | cat | innocent |

| | để | trấn an | mình. | | | | | |

| | to | calm | REFL. | | | | | |

| | ‘As for old Hứng, terrified, he took his frustration out on an innocent cat to calm himself down.’ |

| | Source: Côi cút giữa cảnh đời (1988). Ma Văn Kháng. |

| (3d) | Biết bao | kẻ | đang | hăm hở | chứng tỏ | mình | rên lên |

| | Many | people | PROG | eager | prove | REFL | groan |

| | như vậy. | | | | | | |

| | same. | | | | | | |

| | ‘Many people, eager to prove themselves, are groaning the same way!’ |

| | Source: Cơ hội của Chúa (3/1989–21/2/1997). Nguyễn Việt Hà. |

| (3e) | Biết bao | người | anh tuấn | còn | chôn | mình | trong |

| | Many | people | handsome | still | bury | REFL | in |

| | lau sậy | để | đợi | lúc gió mây. | | | |

| | reeds | to | wait | when it’s cloudy. | | | |

| | ‘So many handsome men still buried themselves in the reeds to wait for the cloudy weather.’ |

| | Source: Phan Khôi. Tác phẩm đăng báo 1928. Lại Nguyên Ân sưu tầm, biên soạn. Nhà xuất bản Đà Nẵng–2001. (lainguyenan.free.fr) |

Furthermore, the judgements of sentences with

tự-less local binding with

mình in

Đoàn (

2022) are not necessarily shared by all speakers. The author of the present paper who is a native speaker of Vietnamese finds the following examples from

Đoàn (

2022) to be acceptable with a local binding relation between

mình and the subject of the sentence, although such a dependency is starred as ungrammatical in

Đoàn (

2022):

| (4) | Namk | chỉ trích | mìnhk |

| | Nam | criticize | body |

| | ‘Nam criticizes himself.’ (* in Đoàn, 2022, p. 71) |

| (5) | Lank | trừng phạt | mìnhk |

| | Lan | punish | body |

| | ‘Lan punished herself.’ (* in Đoàn, 2022, p. 4) |

| (6) | Người | đàn ôngk | đã | khen | mìnhk. |

| | CL | man | PST | praise | body. |

| | ‘The man praised himself.’ (* in Đoàn, 2022, p. 116) |

In a subsequent paper focused on long-distance binding in Vietnamese,

Đoàn et al. (

2023, p. 1) acknowledge the following:

‘Like many languages, Vietnamese is not entirely homogeneous. The data in this article reflect the language spoken in the Center/Middle of the country … The reader should be aware that speakers from the Northern region or the Southern region might diverge in some of their judgments. So far, a comprehensive study of the variation within Vietnamese is not available.’

This raises the possibility that regional variation in the use of mình might perhaps underlie differences in acceptability judgments with examples that appear to violate (1), an issue examined in the current paper.

The question of whether there are speakers who permit local binding with

mình in the absence of

tự also has a broader significance, extending beyond Vietnamese to the cross-linguistic typology of binding relations and general theories of anaphora and reflexivity. It has frequently been suggested (

Cole et al., 1990;

Reinhart & Reuland, 1993;

Reuland, 2001) that local binding between a subject and an object (or other co-argument) requires an anaphor that is morpho-syntactically complex, and anaphors that are monomorphemic ‘simplex expressions/SEs’ have been described as rejecting local binding relations, as exemplified in Dutch (7).

Such typological observations have led on to the development of a highly prominent and influential approach to binding in

Reinhart and Reuland (

1993) and

Reuland (

2001,

2011,

2017), which sets out to explain why monomorphemic anaphors are uniformly unable to reflexivize a predicate. In a recent extension of this body of work,

Reuland et al. (

2020), it is noted that Mandarin Chinese might appear to constitute an exception to the crosslinguistic patterning of SEs, as both the complex anaphor

ta ziji and the (apparently) simplex anaphor

ziji allow for local binding:

| (8) | Zhangsank | changchang | piping | zijik/ta zijik. |

| | Zhangsan | often | criticize | 3 self |

| | ‘Zhangsan criticizes himself.’3 |

Reuland et al. (

2020, p. 800) write as follows: ‘If

zi-ji were truly simplex…its behavior would not fit the overall pattern observed, and it would pose a challenge to the approach in

Reuland (

2011)’.

Reuland et al. (

2020) then go on to argue that Mandarin

ziji is actually not monomorphemic and is instead a morphologically complex anaphor, consisting of two morphemes

zi- and -

ji, and that this explains its ‘exceptional’ behavior. However, the Vietnamese

mình cannot be analyzed as bi-morphemic, unlike the Mandarin

ziji. If

mình can be used to reflexive-mark a verb, it would therefore pose a clear empirical challenge to theories of reflexivity built on the assumption that local binding is not possible between a monomorphemic anaphor and a co-argument.

With this as background, the primary goal of the current experimental investigation of

mình is to achieve a better understanding of the cross-speaker patterning of

mình in configurations of local reflexivity and to probe what regional variation may potentially occur in the use of

mình as a reflexive object. We conclude that, for many speakers from different regions of Vietnam,

mình in object position may indeed be interpreted reflexively with the subject of the same clause without the need for

tự. On the basis of patterns involving ellipsis and quantificational subjects, it is further shown that this is a genuine binding relation and not simple co-reference. Such conclusions are then noted to have significant consequences for approaches to binding such as that of

Reuland (

2011).

The structure of the paper is as follows.

Section 2, the core of the paper, describes an experiment carried out with 95 speakers of Vietnamese from different parts of Vietnam, designed to examine the acceptability of local binding with

mình in combination with different types of predicate, and discusses the results of the experiment, which present a different picture of binding relations in Vietnamese than the patterning described in

Đoàn (

2022). As the results of the experiment also call into question assumptions held about SEs in

Reuland (

2001) and other works,

Section 3 considers whether and how it might be possible to reinterpret the current experimental data in ways that might avoid the conclusion that

mình is extensively used as a local anaphor.

Section 3 argues against such alternative analyses and for the conclusion that the patterns tested in the experiment display the properties of genuine syntactic binding.

Section 4 summarizes the findings of the paper for the study of anaphora in Vietnamese and also for binding theory in general.

2. An Experimental Investigation of the Local/Non-Local Interpretation of Mình

The focus of the current study is to determine whether speakers from different parts of Vietnam accept co-reference between the subject of a verb and

mình in object-of-verb position (or as the object of a preposition) without the occurrence of

tự, resulting in a reflexive interpretation, as schematized in (9):

In designing an experiment to examine the general acceptability of structures such as (9), we factored in considerations of the potential influence of predicate choice on the naturalness of reflexive interpretations. The verbs in Đoàn’s unacceptable examples (where

mình resists local co-reference in the configuration in (9)) all encode

heavily other-directed actions—the set of verbs listed in (10) and illustrated with (11). The actions represented by such predicates are all perceived as naturally being carried out on other individuals, and are difficult to imagine as being directed toward the initiator of the action, i.e., being reflexive in orientation.

| (10) | động viên–encourage |

| | khen–praise |

| | ngưỡng mộ–admire |

| | la mắng–scold |

| | xúc phạm–offend |

| (11) | Maii | nghĩ | Namj | sẽ | động viên | mìnhi/*j. |

| | Mai | think | Nam | FUT | encourage | self |

| | ‘Maii thought Namj would encourage heri/*himselfj.’ (Đoàn, 2022) |

With heavily other-directed verbs, hearers may not consider interpretations in which the subject acts on herself, i.e., reflexive interpretations. This might lead hearers to regularly ignore possible construals of

mình as referring to local subjects in favor of other available interpretations of

mình. As is well-known (

Bui, 2019;

Đoàn, 2022;

Phan & Chou, 2023), a significant complication in many sentences incorporating

mình is that

mình can frequently be interpreted as a first-person or second-person pronoun, referencing either the speaker or the hearer. Hence, in many instances, a [Subject Verb

mình] configuration will allow for

mình to be interpreted as either ‘me’ or ‘you’, as alternatives to any sentence-internal co-reference with the subject. It may be speculated that with heavily other-directed verbs, hearers might often discard potentially available reflexive interpretations of

mình due to the easier availability of construing

mình as representing the speaker or the hearer, an interpretation more readily in line with the typical use of heavily other-directed verbs. Such a confounding possibility suggests that the patterning of

mình with

động viên ‘encourage’,

ngưỡng mộ ‘admire’, etc., should not immediately be taken to be representative of the general distribution of

mình, and a broader range of predicates should be examined in any investigation of local binding in Vietnamese. Additionally, Đoàn’s example sentences demonstrating that

mình cannot be interpreted as co-referential with a local subject are presented in isolation from any embedding context, which may arguably increase the difficulties for hearers to access reflexive interpretations with heavily other-directed verbs. Considerations of this kind lead to two questions, which have guided the current experimental study of

mình. First, how do heavily other-directed verbs pattern (in the interpretations accepted for

mình) if a supporting context is added rather than sentences being presented in isolation, without any context? Second, what patterning is observed with

mình if one considers more neutral verbs rather than just heavily other-directed verbs?

In connection with the above, prior to creating stimuli for the experimental study, the authors hypothesized, on the basis of initial, casual, native-speaker intuitions, that there may be differences among verbs with regard to the availability of local binding with mình relating to the typical use of verbs as heavily other-directed vs. not other-directed, as described below.

Type I. Verbs which are typically/heavily other-directed. These may be expected to either favor or perhaps require the presence of tự for reflexive interpretations in the absence of a supporting context. Henceforth, we refer to this group of verbs as the ‘admire’ class. Examples of this posited group are the following:

ngưỡng mộ–admire

ghét–hate

chửi mắng–scold

bảo vệ–protect

Type II. Verbs which are not heavily other-directed/are more neutral. Such predicates might permit reflexive interpretations for certain speakers without the necessary/preferred presence of tự. We refer to this group as the ‘blame’ class. Examples posited in this group (as a result of preliminary intuitions gathered from other speakers prior to the experiment) are the following:

trách–blame

ngụy trang–disguise

bồi bổ–nourish

thể hiện–show off

The stimuli created for the experiment made use of predicates from both posited types, in order to be able to report on differences in local binding that might potentially occur as a function of typical verb orientation. The parameters of the experiment are described in

Section 2.1.

2.1. Experiment Design

2.1.1. Participants

One hundred and twelve Vietnamese native speakers were recruited online across three regions in exchange for a $2.05 gift card to the online store Tiki. Eighteen subjects having accuracy rates below 67% on the unambiguous conditions were excluded, leaving 94 subjects in the main data analysis. The study was reviewed and approved by the Institutional Review Board of the University of Southern California, which is fully accredited by the Association for the Accreditation of Human Research Protection Programs (AAHRPP).

Prior to the main experiment, the participants were asked to complete a questionnaire about their language background. The numbers of participants speaking different regional varieties of Vietnamese are summarized in

Table 1.

2.1.2. Procedure and Materials

The participants in the experiment were asked to read Vietnamese sentences in which two or more noun phrases were underlined in order to signal that these noun phrases should be construed as referring to the same individual/set of individuals. The participants were instructed to rate how natural the sentences were with the intended co-reference relation, using a 1–7 scale of naturalness, 1 being completely unnatural/unacceptable and 7 being completely natural/acceptable. Examples of items used in the experiment are presented in

Table 2. The experiment included sentences containing examples of verbs of Types I and II, as described in

Section 2. Eight of the test items made use of regularly other-directed verbs (Type I), with two of these items involving

mình following a preposition. Twelve test items used verbs encoding actions that are not so regularly other-directed—Type II ‘neutral’ verbs—with two of these examples involving

mình following a preposition, and two examples having quantificational subject antecedents for

mình. All of the test items containing Type I and Type II verbs occurred without the use of

tự.

All the test items occurred in linguistic contexts that would allow for a reflexive interpretation to be available and potentially natural. The set of test items involving Type I and Type II predicates specifically aimed to establish whether

mình could be interpreted reflexively (referring to its immediately preceding subject) in the absence of

tự, only assisted by a supportive, plausible context. In addition to the target sentences involving

mình with Type I and Type II verbs, the experiment also included sentences using the pronoun

nó ‘it’ in Vietnamese as fillers, with 10 acceptable and 10 unacceptable conditions (i.e., 10 instances in which participants should find co-reference between

nó and a second, underlined noun phrase acceptable, and 10 examples where such co-reference should not be acceptable). These fillers were used as catch trials to determine whether participants were concentrating on the study or not.

4 2.1.3. Data Analysis and Results

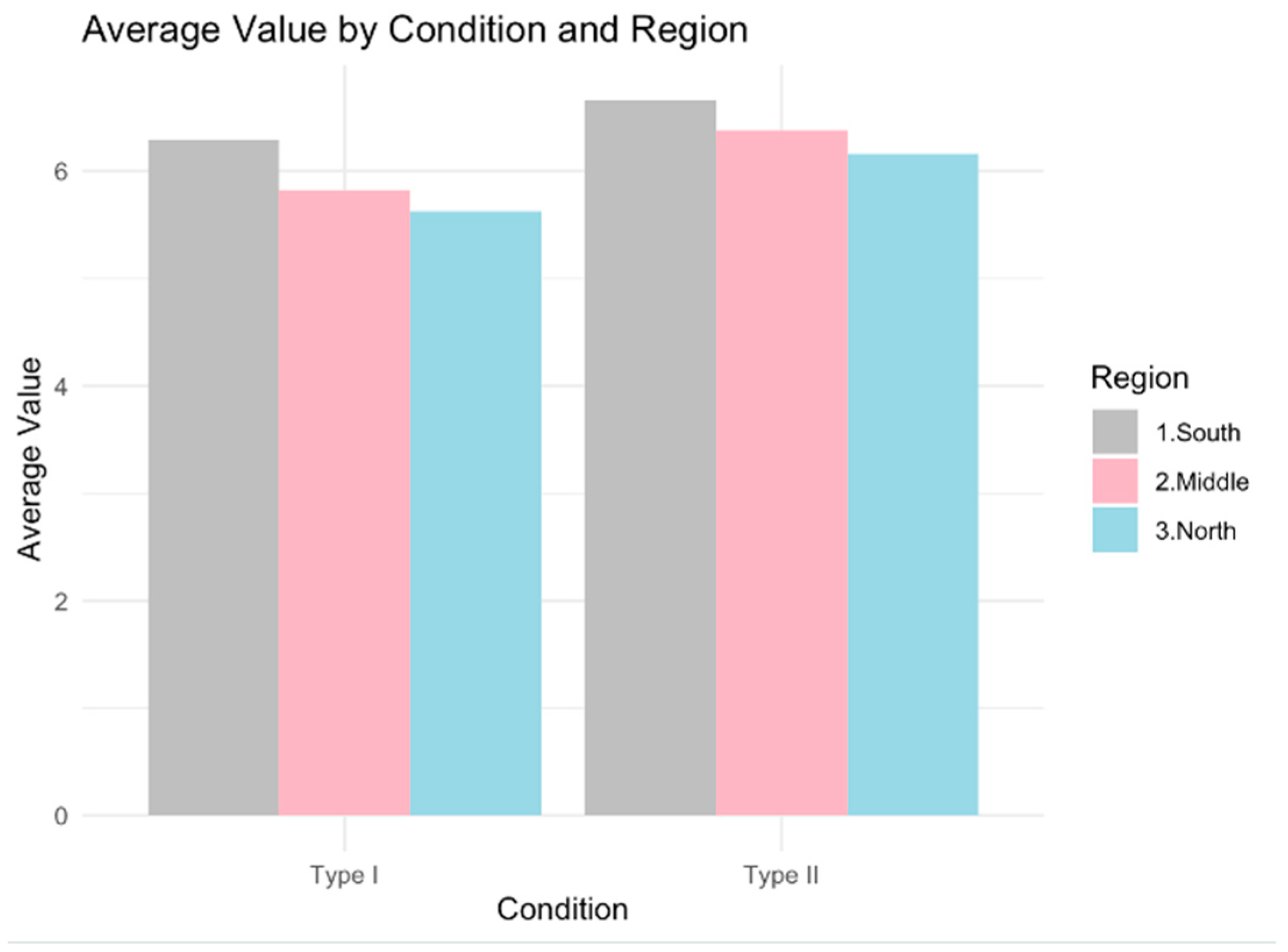

Figure 1 presents the results of the participants’ judgements on the acceptability of reflexive interpretations of

mình—where

mình in object-of-verb position is construed as co-referential with the subject of its own clause. As seen in

Figure 1, there was a very high level of acceptability/naturalness when

mình occurred as the object of Type II/neutral verbs and was interpreted as referring to its local subject, i.e., a reflexive interpretation. Participants from all three regions of Vietnam judged such examples to be very natural and acceptable, with average scores exceeding 6/7 for all regional participants. This provides clear, strong support for the conclusion that reflexive interpretations of

mình are both widely available and felt to be natural without the support of

tự, in contrast to

Đoàn’s (

2022) findings and generalization that such interpretations are only possible when licensed by the overt presence of

tự. Considering the participants’ judgements of examples involving Type I typically other-directed verbs, these also showed a high level of acceptability, exceeding 6/7 for speakers from southern Vietnam and close to 6/7 for speakers from central and northern Vietnam. These results confirm that reflexive interpretations of

mình with a local subject are generally possible in the absence of

tự even with typically other-oriented verbs once such predicates are embedded in plausible supporting contexts rather than being presented out of the blue as isolated sentences.

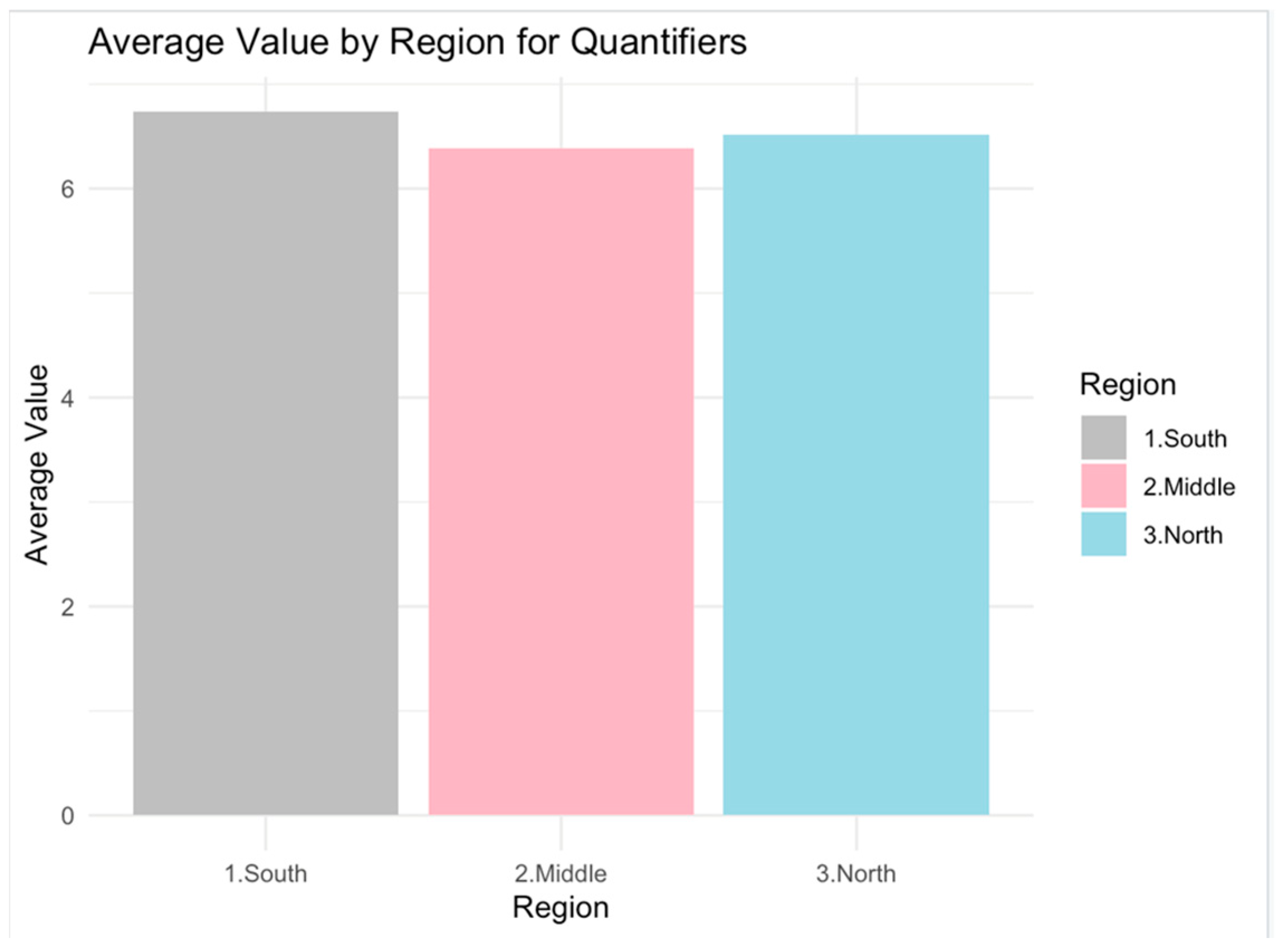

Figure 2 shows the acceptability values for the test items in which the subject in [

Subject Verb

mình] examples was a quantifier phrase/QP. Four different quantifiers occurred in subjects in these test items:

tất cả ‘all’,

mỗi ‘every’,

ít nhất ‘at least’, and

hơn mười ‘more than ten’. As seen in

Figure 2, a very high level of acceptability was recorded by speakers from all three regions for sentences in which

mình occurred in a reflexive interpretation with a quantificational subject in the absence of

tự, averaging over 6/7 for speakers from all regions.

5 The experiment also included sentences in which

mình occurred following a preposition in sequences of [

Subject Verb [P

mình]], rather than as the direct object of the verb. The expectation was that reflexive interpretations of

mình with the subject in such examples might perhaps be found to have a higher level of acceptability than in configurations where

mình was the direct object of the verb. The reason for such an expectation was the suggestion in

Đoàn (

2022) that the embedding of

mình in PPs permits reflexive interpretations with a local subject which are not available when

mình occurs as the direct object of the verb (in the absence of

tự)—see the discussion in

Section 3.2 below. Interestingly, the results of the experiment did not align with this expectation and present a clear difference in acceptability when

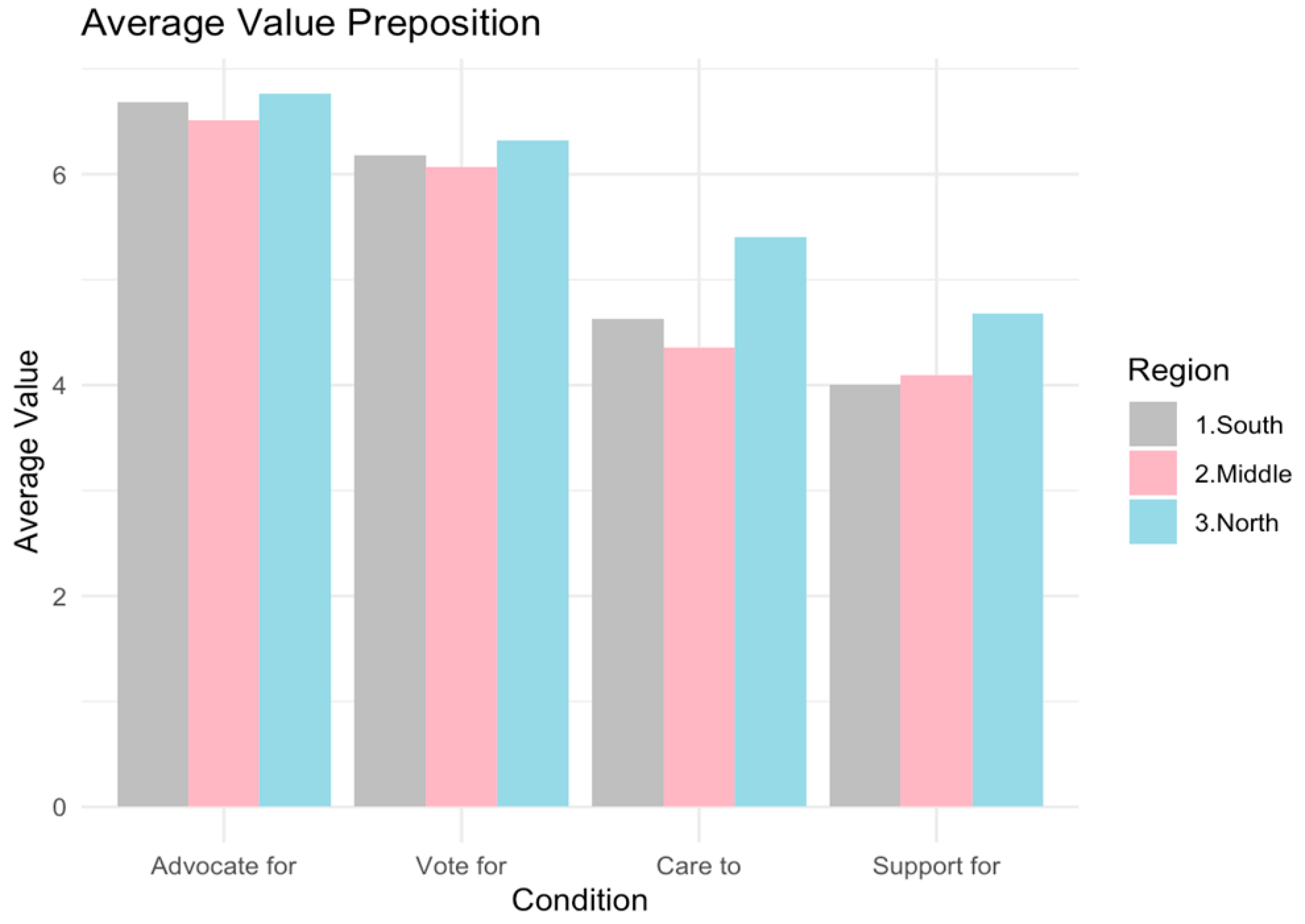

mình occurred in PPs with Type I and Type II verbs. As shown in

Figure 3, with Type II verbs, acceptability ratings with

mình following prepositions were as high as those in examples where

mình occurred as the direct object of the verb, over 6/7. However, with Type I verbs, there was a significantly lower level of acceptability, ranging from 4–5/7.

This reduced acceptability rate relates to specific combinations of verb + preposition. The four pairs of verb + preposition used in examples in the experiment were

biện hộ cho ‘advocate for’,

bình chọn cho ‘vote for’,

quan tâm đến ‘care for’, and

hỗ trợ cho ‘support’. As shown in

Figure 4, acceptability ratings with the former two V + P combinations were as high as in examples where

mình occurred as the direct object of the verb: over 6/7 for speakers from all regions. However, ratings for examples with

quan tâm đến ‘care for’ and

hỗ trợ cho ‘support’ were much lower: 4–5.5/7. This lower acceptability with certain [Subject Verb [P

mình]] combinations casts doubt on there being a fully general, structural licensing of reflexive interpretations of

mình when

mình is ‘protected’ by a PP shell (see

Section 3.2 below).

6While the variable licensing of reflexive interpretations with

mình in PPs may warrant further useful investigation, in general, the experiment presents strong evidence for the availability of reflexive interpretations with

mình in (at least) object-of-verb configurations without any necessary presence of

tự to license such interpretations, when relevant examples are presented in supportive contexts, both with ‘neutral’ Type II verbs and with typically other-directed Type I verbs, for speakers from different regions of Vietnam.

7 Section 3 considers these findings further, in the light of general theories of binding and reflexivity.

3. Mình—A Monomorphemic Anaphor Allowing Local Binding?

The results of the experiment reported in

Section 2 present a clear challenge to claims that

monomorphemic anaphors cannot be used in local binding relations between a subject and an object, to reflexivize the verb (

Reuland, 2011), i.e., the configuration in (12) below. [Subject

k Verb

mìnhk] patterns indeed appear to be robustly accepted by many speakers of Vietnamese.

| (12) | *Subjectk Verb Objectk | Where Object = monomorphemic anaphor |

A question that arises now is whether it might be possible to reinterpret the results of the experiment in ways that might preserve (12) as a cross-linguistic generalization in order to maintain theories of reflexivity built on (12) as a valid, cross-linguistic description. Here we will consider three potential counter-proposals that might be made in response to the conclusion that mình permits a local binding relation with the subject of its clause. In each case, it will be argued that such potential reinterpretations of the experimental data are not well supported.

3.1. Inherent Lexical Reflexives

In English, verbs such as

wash, shower, and

shave have been classified as inherently reflexive predicates (

Reinhart & Reuland, 1993;

Reuland, 2001), because such verbs can occur without an object and still be construed as self-directed actions:

| (13) | John washed/shaved/showered. |

However, an overt anaphor can also be added to such verbs, as seen in (14):

| (14) | John washed/shaved/showered himself. |

One conceivable approach to the alternation in (13/14) might be to suggest that the anaphor object in (14) actually does not function to reflexivize the predicate, as

wash/shave/shower are already lexically listed as having a potentially reflexive meaning.

8 Such a hypothetical approach to

wash/shave/shower-type verbs in English would raise the question whether a similar analysis and categorization might be made of Vietnamese verbs which allow for local binding with

mình. If

mình were to be assumed not to have a reflexivizing function in these cases, similar to

himself in (14), because the verbs that

mình is combined with are lexically specified as reflexive predicates, it might be possible to avoid the conclusion that Vietnamese allows local binding with a monomorphemic anaphor.

However, such an approach appears implausible as a potential ‘explanation’ for the apparent well-formedness of sequences corresponding to (13) in Vietnamese, for the simple reason that many of the verbs which allow for (13) in Vietnamese do not exhibit properties typically found with lexically reflexive verbs.

Vietnamese has two clear types of lexical reflexives, as described in

Đoàn (

2022), and these show different patterns to the use of

mình described so far and examined in the experiment.

The first set of lexical reflexives is made up of pairings of

tự and a verbal root, as exemplified in (15).

| (15) | Type I lexical reflexives: tự + verb combinations |

| | tự sát | tự vệ | tự chủ |

| | SELF kill | SELF guard | SELF control |

| | ‘commit suicide’ | ‘protect onself’ | ‘control oneself’ |

| | | | |

| | tự nhủ | tự phê | tự cấp |

| | SELF say | SELF critique | SELF provide |

| | ‘wonder’ | ‘criticize oneself’ | ‘be self-sufficient’ |

Significantly, lexicalized combinations of this type do not permit the realization of an object—they are lexically detransitivized by the presence of

tự, hence

mình cannot be added:

| (16) | Nam | tự sát/ | tự phê/ | tự vệ | (*/??mình). |

| | Nam | self-kill/ | self-criticize/ | self-protect | self |

| | ‘Nam killed himself/criticized himself/protected himself.’ |

This property distinguishes such compound reflexives from regular verbs such as

trách ‘blame’,

bồi bổ ‘nourish’,

thể hiện ‘show off’, which, for many speakers, allow for local binding and interpretations of reflexivity with

mình in object-of-verb position, either with or without

tự:

| (17) | Nam | (tự) | trách | mình. |

| | Nam | tự | blame | self |

| | ‘Nam blamed himself.’ |

The set of lexical reflexives of the tự sát type is, furthermore, very restricted and has a small membership, whereas verbs which allow local binding with mình in object position are not obviously restricted in number. The latter consequently do not show the typical characteristics of lexical reflexives across languages, which are often found to be restricted to a small number of verbs that describe self-directed actions.

A second type of lexical reflexive described in

Đoàn (

2022:109 fn8) consists in simple combinations of a verb and

mình, as illustrated in (18):

| (18) | Type II: verb + mình combinations |

| | giật mình | cúi mình | thẹn mình |

| | jerk body | bend body | shy body |

| | ‘be startled’ | ‘bow’ | ‘be ashamed’ |

These lexically reflexive predicates are again different from the patterns with

trách ‘blame’, etc., as they do not permit objects which are not

mình, and hence they must be reflexive—they are lexically listed as reflexive-only predicates:

| (19) | *Nam | thẹn/ | giật/ | cúi | Nga. |

| | Nam | shame/ | shake/ | bend | Nga |

| | Intended: ‘Nam shamed/shook/bent Nga.’ |

This patterning is quite unlike

trách ‘blame’ and other verbs investigated in the current study, which readily permit objects that do not result in reflexive interpretations:

| (20) | a | Nam trách Nga | b | Nam ghét Nga. |

| | | Nam blame Nga | | Nam hate Nga |

| | | ‘Nam blames Nga.’ | | ‘Nam hates Nga.’ |

We conclude that verbs such as

trách ‘blame’,

trừng phạt ‘punish’, and

ghét ‘hate’, which, for many speakers, allow for local binding with

mình, are not inherently reflexive, as they display properties that clearly distinguish them from lexicalized reflexives. A reviewer of this paper also helpfully notes that subject-experiencer verbs have thus far never been found to allow lexical reflexivization (

Reinhart & Siloni, 2005), providing a further reason to reject a lexical reflexive analysis of verbs such as

ghét ‘hate’ when they occur in local binding configurations.

3.2. Mình Is Covertly Complex and Not Monomorphemic

A second potential way to avoid the conclusion that

mình is a monomorphemic anaphor allowing local binding might be to suggest that

mình is part of a more complex nominal expression and hence not monomorphemic, despite appearances. It has been proposed that additional structural complexity allows monomorphemic anaphors to be legitimately used in reflexive configurations (the idea of ‘protection’ to avoid a constraint referred to in

Reuland (

2011,

2017) as the ‘Inability to Distinguish Indistinguishables’). In Vietnamese,

Đoàn (

2022) suggests that the embedding of

mình within a PP provides a structural way for

mình to be able to refer reflexively to a local subject in the absence of

tự: ‘when

mình is in a locative PP, it can be bound without the element

tự’ (

Đoàn, 2022, p. 71). This is illustrated in (21):

| (21) | Nami | đặt | quyển | sách | phía sau | mìnhi. |

| | Nam | put | CL | book | behind | self. |

| | ‘Nam put the book behind him(self).’ (Đoàn, 2022, p. 71) |

It might therefore, perhaps, be speculated that, for speakers who regularly accept local binding with

mình (without

tự),

mình is actually part of a more complex nominal structure enabling its apparent reflexive use. Given the commonly assumed origin of

mình from the noun ‘body’, a prime candidate for such an analysis could be the possibility that

mình occurs as the head of a DP which also projects a

pro possessor, as schematized in (22):

The interpretation of (23) below, for speakers who accept local binding, might therefore be licensed by such a complex protective structure and be loosely translated as ‘Nam criticized his self/body.’

| (23) | Namk trách [DP prok [NP mình]]. |

| | Nam blame PRN body |

| | ‘Nam blames himself.’ |

However, if

mình were to project a larger, covert structure with a pro possessor, it might naturally be expected that this null element could be overtly lexicalized, but this is not possible, as shown in (22a/b):

| (24) | a. | *Nam | trách | [DP nó | [NP mình]]. | |

| | | Nam | blame | 3 | body | |

| | b. | *Nam | trách | [DP [NP mình] | (của) | nó] |

| | | Nam | blame | body | of | 3 |

There is consequently no evidence that might support the assumption of a covert, complex structure with

mình in such cases, so we continue to assume that

mình is indeed a monomorphemic anaphor (as also maintained in (

Bui, 2019) and (

Đoàn, 2022)).

3.3. The Interpretation of Mình with Local Subjects Is Co-Reference, Not Binding

A final way to deflect the current conclusion that

mình permits local binding, for many speakers, in the absence of

tự, might be to suggest that the relation of

mình to its local subject in such cases is actually ‘co-reference’ rather than ‘binding’. In previous work on binding relations, it has been noted that the interpretation of objects as referring to the same individual/entity as a local subject (or some other sentence-internal c-commanding element) should sometimes be attributed to contextually licensed ‘co-reference’ rather than syntactically mediated binding, as in (112), where Principle C appears to be violated:

| (25) | Nobody likes John. Even John doesn’t like John. |

In order to rule out the possibility that two sentence-internal elements are interpretationally related to each other via simple discourse-dependent co-reference rather than binding, two kinds of test have been proposed to identify true instances of binding, involving the use of quantificational antecedents and the potential availability of sloppy interpretations in ellipsis(-type) structures.

If a quantifier phrase may legitimately occur as the antecedent for a pronoun/anaphor, as illustrated in (26), this is taken to signal that the relation between pronoun/anaphor and antecedent is one of genuine binding (

Reinhart, 1983):

| (26) | a. | Every soldierk abandoned hisk position. |

| | b. | Nobodyk gave away hisk secret. |

| | c. | At least three studentsk will submit theirk assignment late. |

Where sloppy interpretations of pronouns/anaphors may arise in the interpretation of ellipsis patterns, this is similarly assumed to require and indicate a true variable-binding relation, as, for example, in (27) (

Sag, 1976;

Williams, 1977 among others):

| (27) | John likes his teacher. Bill does too. |

In assessing the results of the present experimental investigation of mình, it is important to check and confirm that the construal of mình with a local subject is due to binding rather than discourse-mediated co-reference. In order to do this, we consequently need to examine whether mình accepts quantificational antecedents in local configurations, and whether interpretations of sloppy identity are locally possible with mình.

The first question is therefore whether

mình in object-of-verb position can be interpreted as referring to a quantificational subject (without the presence of

tự). The answer to this question is a clear ‘yes’. It is both possible and natural for

mình to refer to a local QP subject, as illustrated in (28) and (29), which were part of the experimental data and well accepted by participants in the experiment, as already reported in

Section 2.

| (28) | Cuộc thi | sắc đẹp | diễn ra | rất căng thẳng. |

| | NZL contest | beauty | occur | very competitive |

| | ‘The beauty contest is very competitive.’ |

| | Mỗi | ứng viên | đều | cố gắng | thể hiện | mình |

| | Every | candidate | all | try | show off | REFL |

| | trước | ban giám khảo | | | | |

| | in front of | judge | | | | |

| | ‘Every candidate is trying to show themselves off in front of the judges.’ |

| (29) | Chủ nhật | tuần rồi | đội tuyển quốc gia | đã | thua | trận bóng. |

| | Sunday | last week | team national | PST | lose | game |

| | ‘Last Sunday, the national team lost the game.’ |

| | Mỗi | cầu thủ | đều trách | mình | vì | đã | bỏ lỡ | cơ hội | vào | vòng bán kết. |

| | Every | player | all blame | self | because | PST | miss | opportunity | enter | semi-final |

| | ‘Every player blamed himself because they missed the opportunity to be in the semi-final game.’ |

The second issue is whether

mình (without

tự) permits interpretations of sloppy reference in ellipsis-type constructions. Here we considered the interpretation of [Subject cũng vậy] ‘subject also thus’ structures, in which content from a preceding clause/sentence is associated with a different subject in a following

cũng vậy clause, in a way similar to VP-ellipsis constructions in English. The critical question is whether an instance of

mình in the antecedent clause can be interpreted as referring to the subject of the

cũng vậy clause (via variable binding)—a sloppy interpretation.

9 Such construals are indeed judged to be very natural and straightforward, as shown in (30–31).

| (30) | Năm học này, | toàn bộ | học sinh | đã | rớt | môn. | | |

| | Year study | all | student | PST | fail | exam | | |

| | ‘This year, the students all failed their exams.’ |

| | Thầy | Nam | trách | mình, | và | cô | Nga | cũng vậy. |

| | Teacher | Nam | blame | self, | and | teacher | Nga | also thus |

| | ‘Teacher Nam blames himself and Teacher Nga does too.’ |

| | Sloppy interpretation: Teacher Nga blames herself.’ |

| (31) | Trong | buổi bầu cử | trưởng thôn, Nam | đã | bầu chọn | cho | mình |

| | In | election | village chief, Nam | PST | vote | for | self |

| | và | Tâm | cũng vậy. | | | | |

| | and | Tam | also thus | | | | |

| | ‘In the elections for village headman, Nam voted for himself and Tam also did.’ |

| | Sloppy interpretation: Tam voted for himself. |

A consideration of quantificational antecedents and the availability of sloppy identity therefore both unequivocally support the conclusion that the construal of mình with a local subject is/can be genuine binding and cannot be dismissed as ‘simple co-reference’. The element mình in Vietnamese consequently represents a genuine counter-example to assumptions underpinning certain prominent approaches to binding—mình is an anaphor which, for many speakers, permits local binding with the subject of its clause, despite its monomorphemic nature.

4. Summary and General Conclusions

The primary goal of the present investigation has been to examine and clarify the status of certain basic binding patterns in Vietnamese involving the anaphor

mình. While the important study of anaphoric relations made by

Đoàn (

2022) reports that

mình may only refer to the subject of its containing clause if paired with the element

tự (32), the current paper has endeavored to probe whether such an intuition is fully shared by other speakers, or whether

mình may perhaps allow for local binding in the configuration in (33), without the support of

tự:

| (32) | subjectk *(tự) verb mìnhk (Đoàn, 2022) |

| (33) | subjectk verb mìnhk |

We also aimed to examine whether there might be any consistent regional differences in speakers’ acceptance of

mình in local binding relations without

tự. Our experiment consequently involved 94 participants from north, central, and south Vietnam and tested speakers’ reactions to

mình presented in structures corresponding to (32) with a variety of predicate types. We would like to stress that the current study involved a different approach to

Đoàn (

2022), testing the acceptability/naturalness of examples in supportive contexts rather than as isolated sentences. Consequently, the present study is not directly comparable to the judgements recorded by

Đoàn (

2022), though it can be assessed relative to the generalizations about possible/impossible anaphoric structures in Vietnamese which Đoàn draws from her findings. The results of the experiment show that binding between

mình and its local subject (without

tự) appears, in fact, to be widely accepted by speakers from all areas of Vietnam when presented in a natural, supporting context. Participants in the experiment from all regions also regularly accepted the variable construal of

mình with a local quantificational phrase subject, confirming that the relation between

mình and its local subject is binding rather than simple accidental co-reference. Such a conclusion is further supported by the occurrence of sloppy identity readings involving

mình in

cũng vậy constructions.

Taken together, the results of the experiment provide strong support for the position that

mình can indeed engage in a binding relation with a local subject in the absence of

tự for many speakers of Vietnamese. Such a conclusion will, we believe, be useful for future studies of anaphoric relations in Vietnamese and the use of binding patterns to investigate other aspects of Vietnamese syntactic structures. As noted earlier in the Introduction, it also has potentially broader importance for the cross-linguistic typology of binding by means of anaphors that are simplex expressions/SEs. In a series of works by

Reinhart and Reuland (

1993),

Reuland (

2001), and

Reuland et al. (

2020), the assumption is made that SEs/monomorphemic anaphors are either heavily restricted to a set of self-directed actions (

washing oneself,

shaving oneself, etc.) or require the support of some other element (such as

tự) in order to reflexivize a predicate. This does not seem to be the case in Vietnamese, where there are no obvious restrictions on verbs that can be interpreted reflexively with the use of

mình, including verbs that are typically other-directed. Vietnamese therefore presents an interesting empirical challenge to theories of binding that assume that local binding via SEs should not be found in any language—such patterns were robustly attested in the current experimental investigation of

mình. How such ‘exceptionality’ in Vietnamese may be accommodated with the patterning of SEs reported for other languages, and whether Vietnamese is truly exceptional among languages with monomorphemic anaphors, we must leave for future work.