How Has Poets’ Reading Style Changed? A Phonetic Analysis of the Effects of Historical Phases and Gender on 20th Century Spanish Poetry Reading

Abstract

1. Introduction

1.1. Brief Overview of Phonetic Studies on Poetry Reading

1.2. Aims, Research Questions, and Hypotheses

2. Materials and Methods

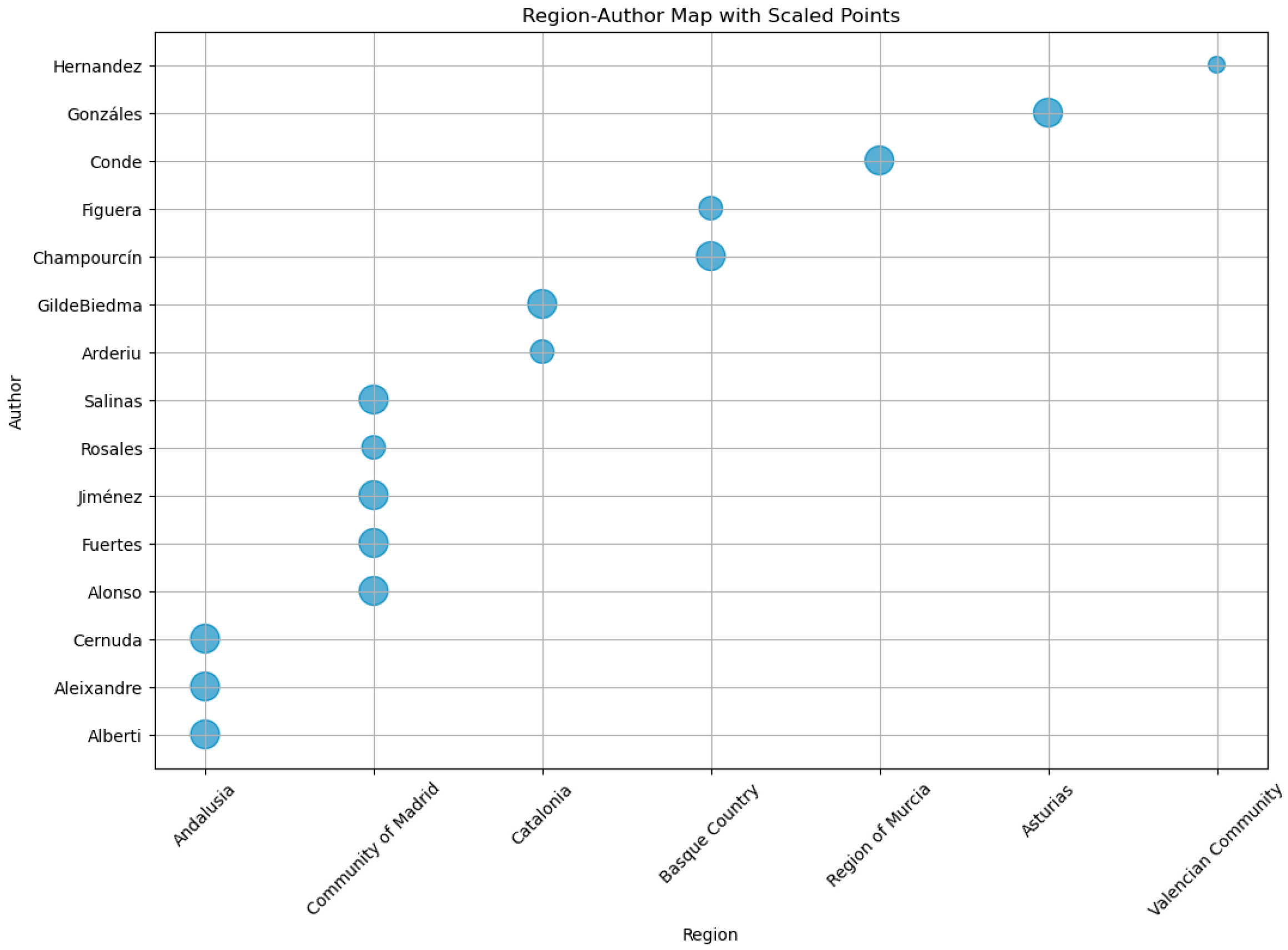

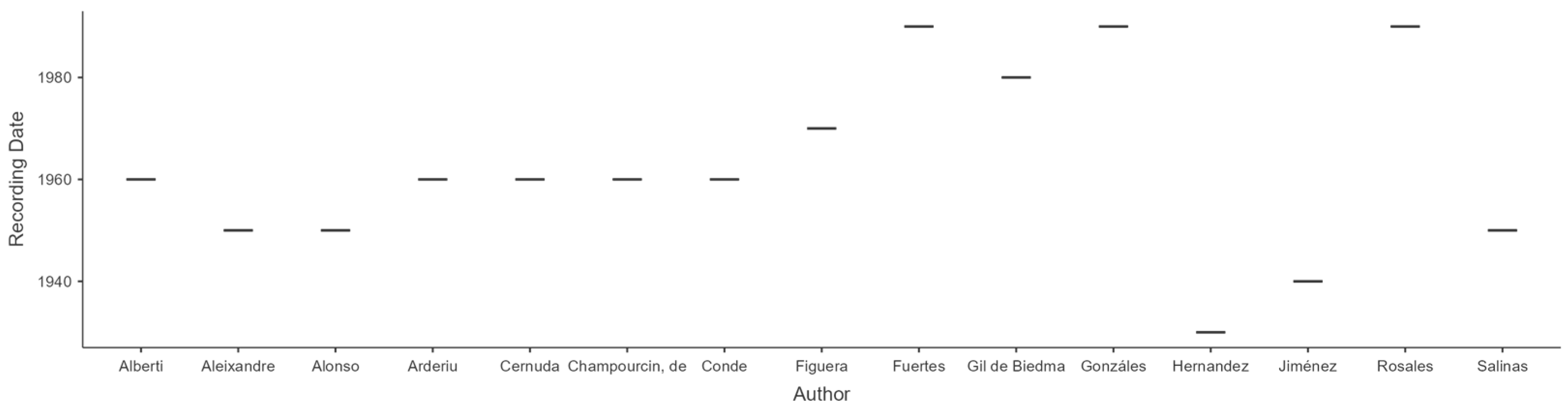

2.1. Recordings

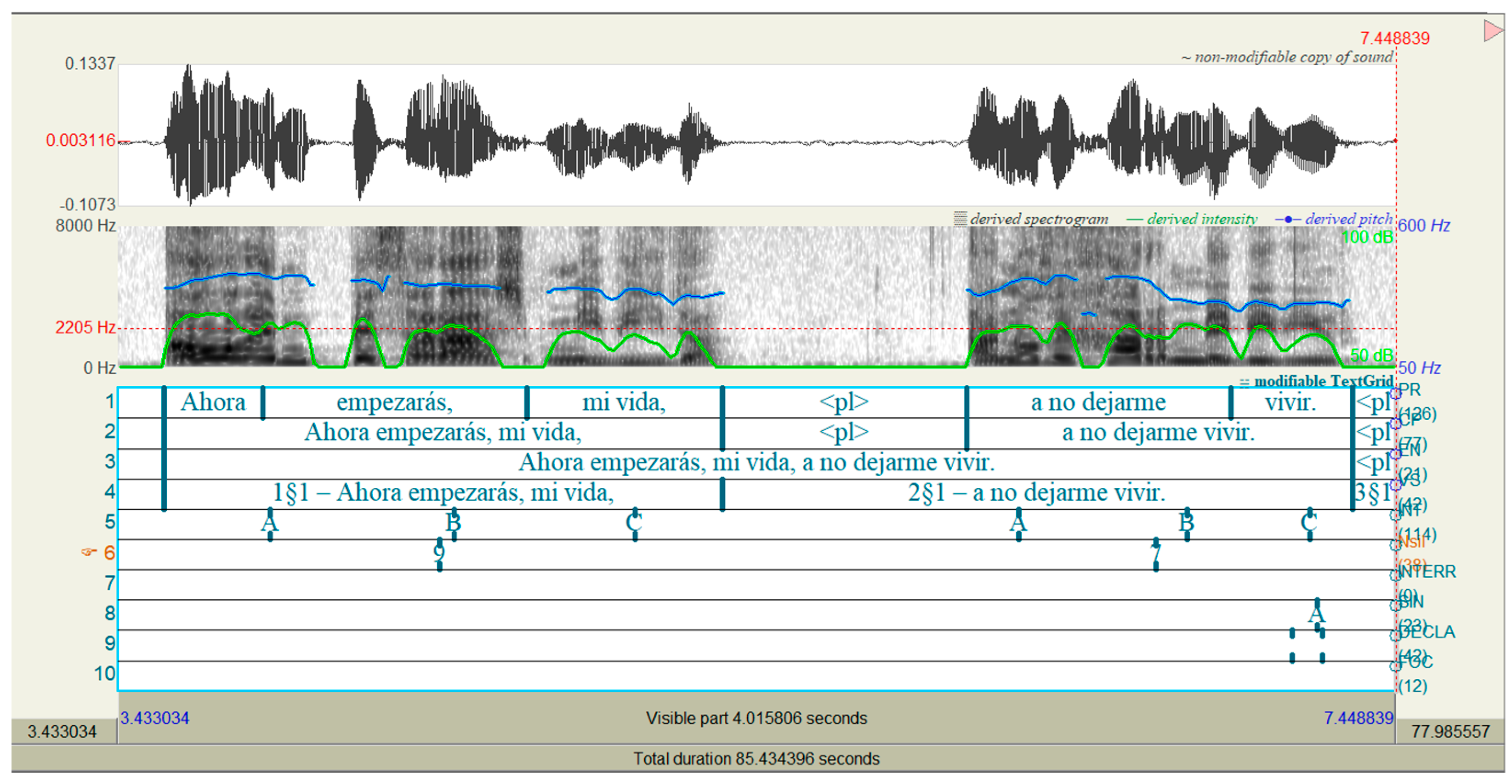

2.2. Annotation and Data Extraction

2.3. Data Description

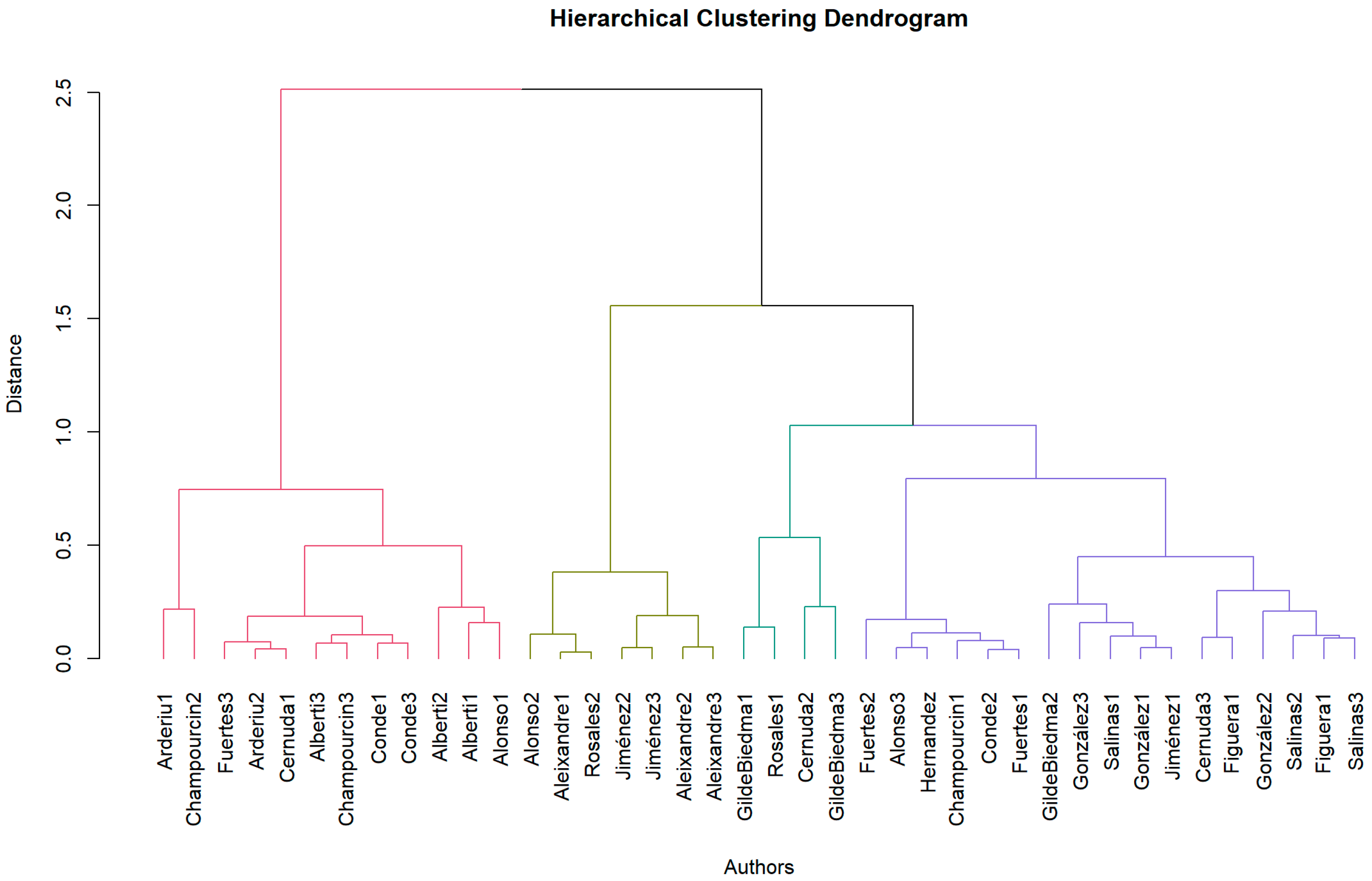

2.4. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

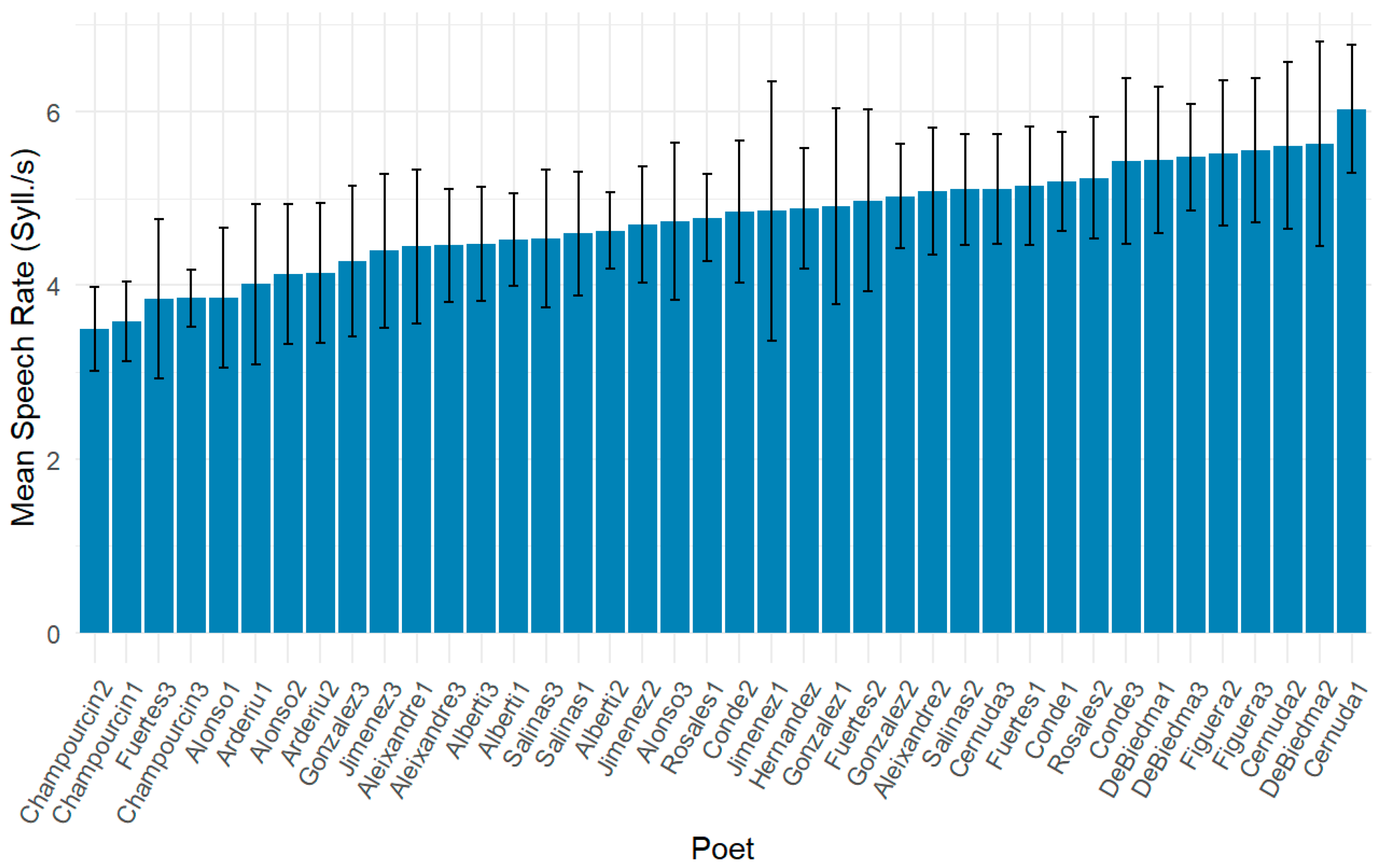

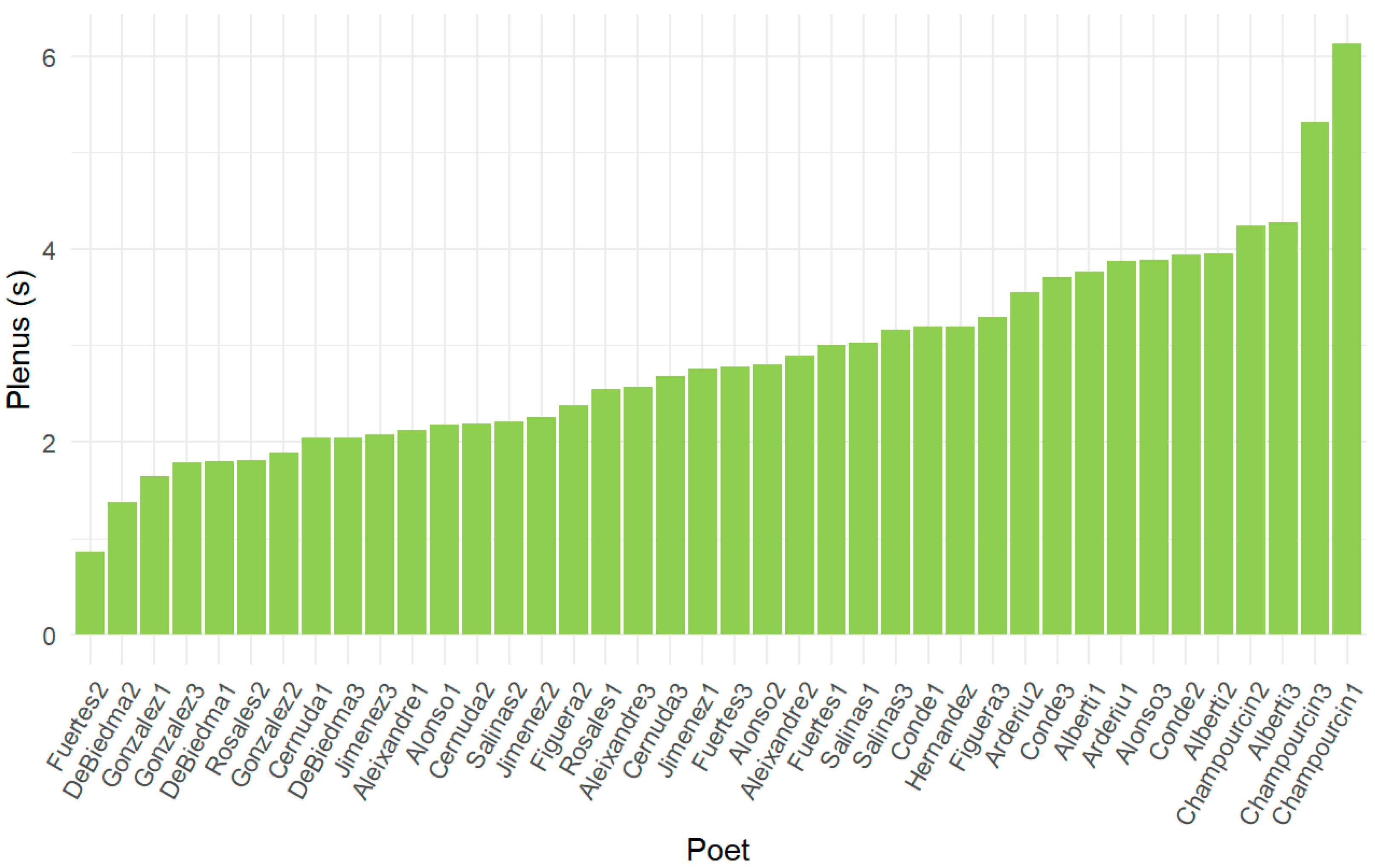

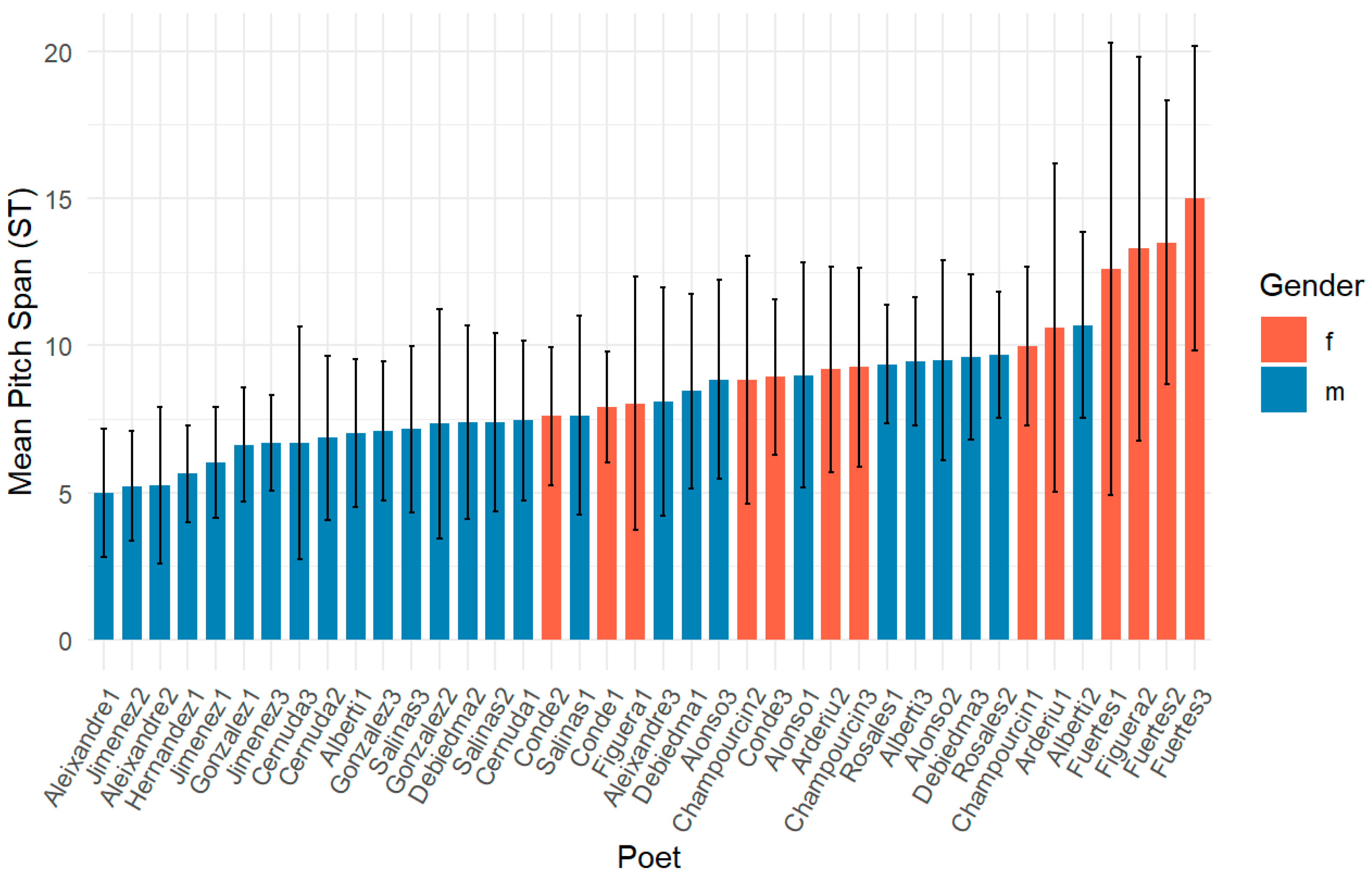

3.1. PO and PRO Features: General Overview

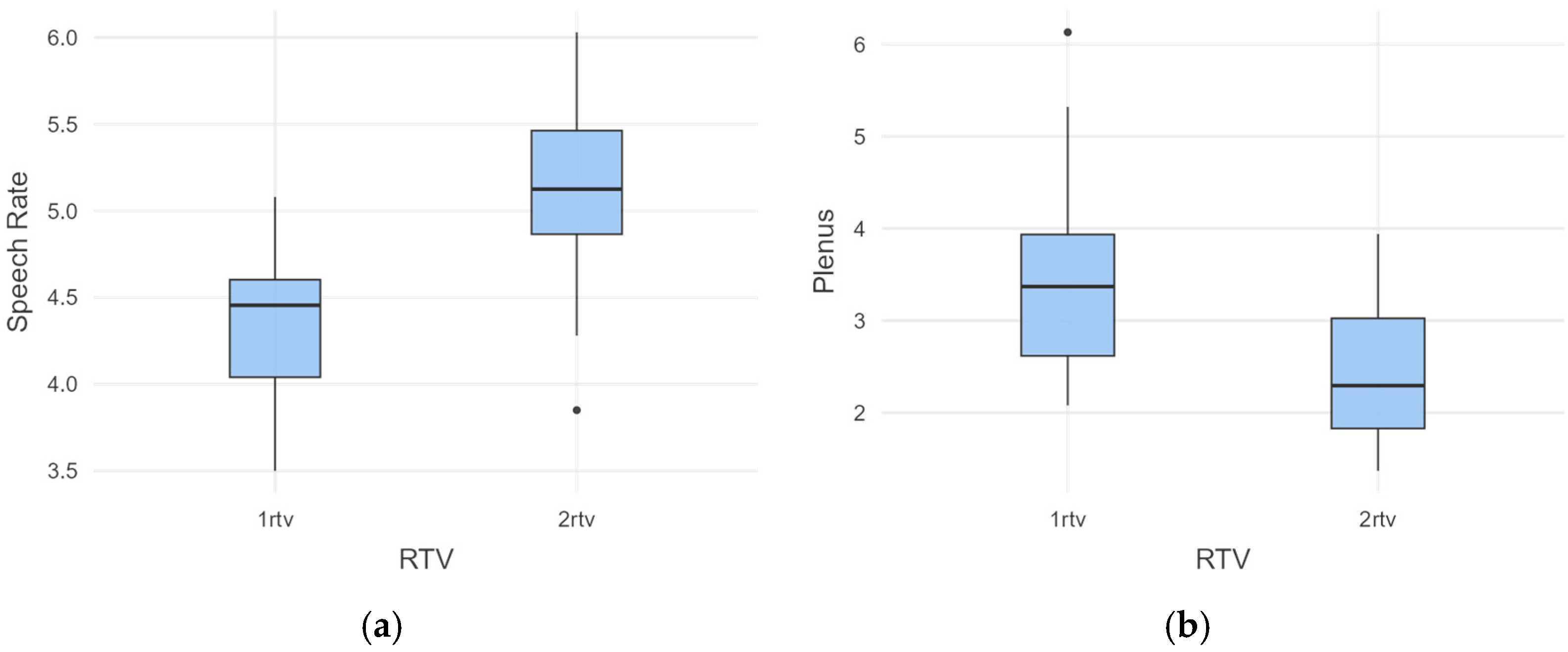

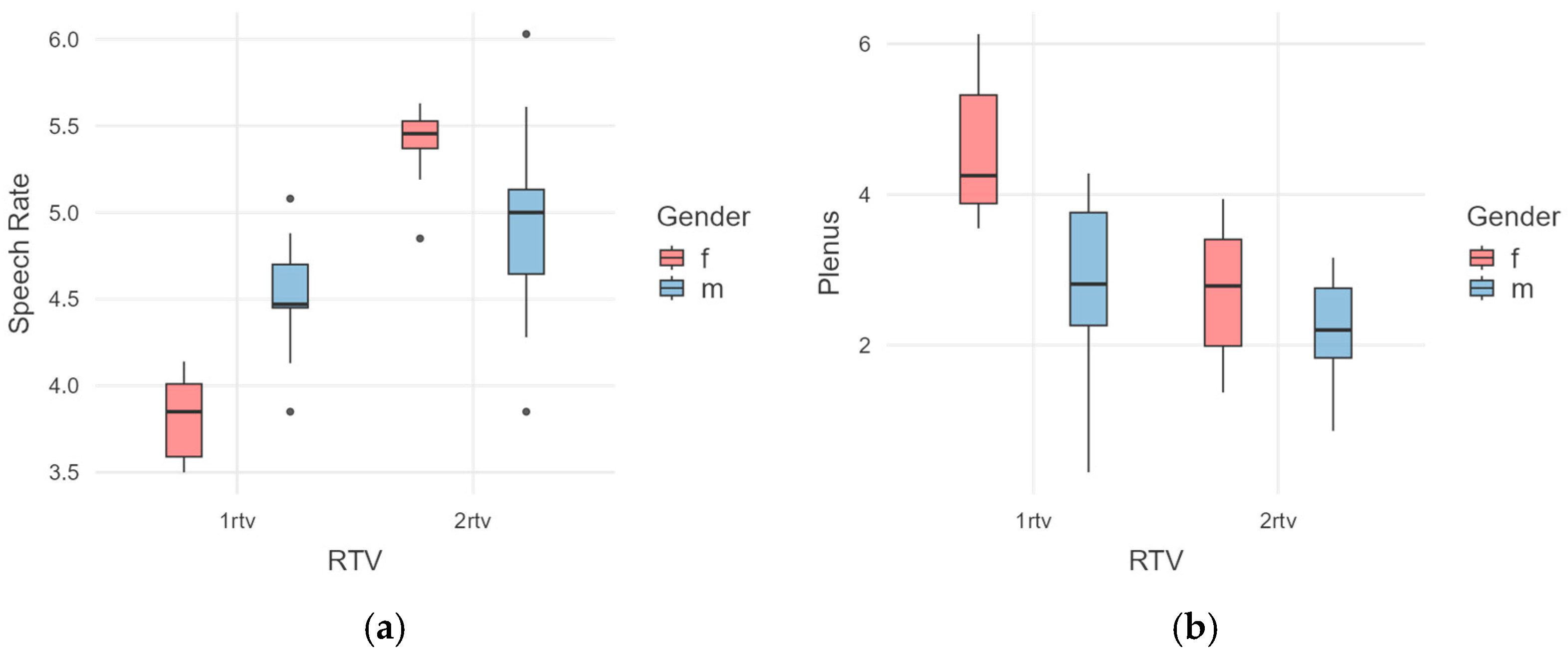

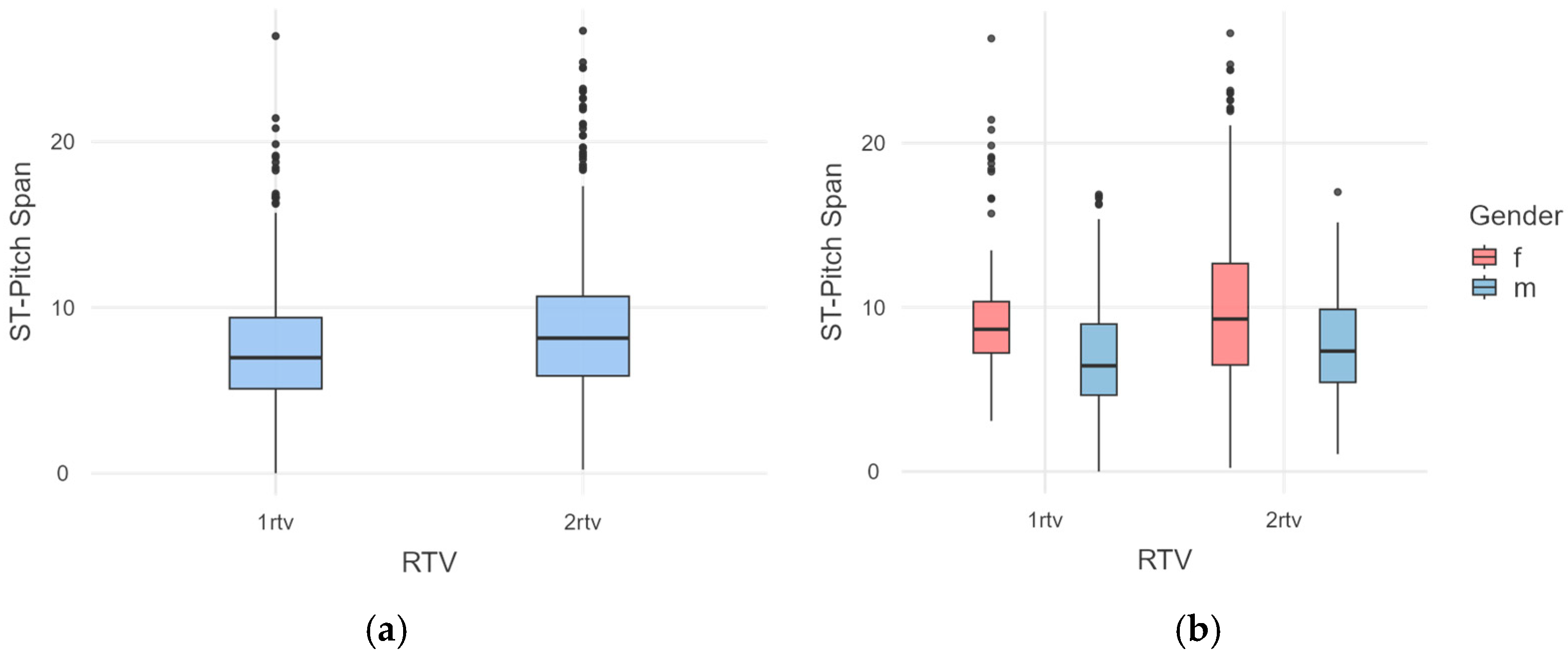

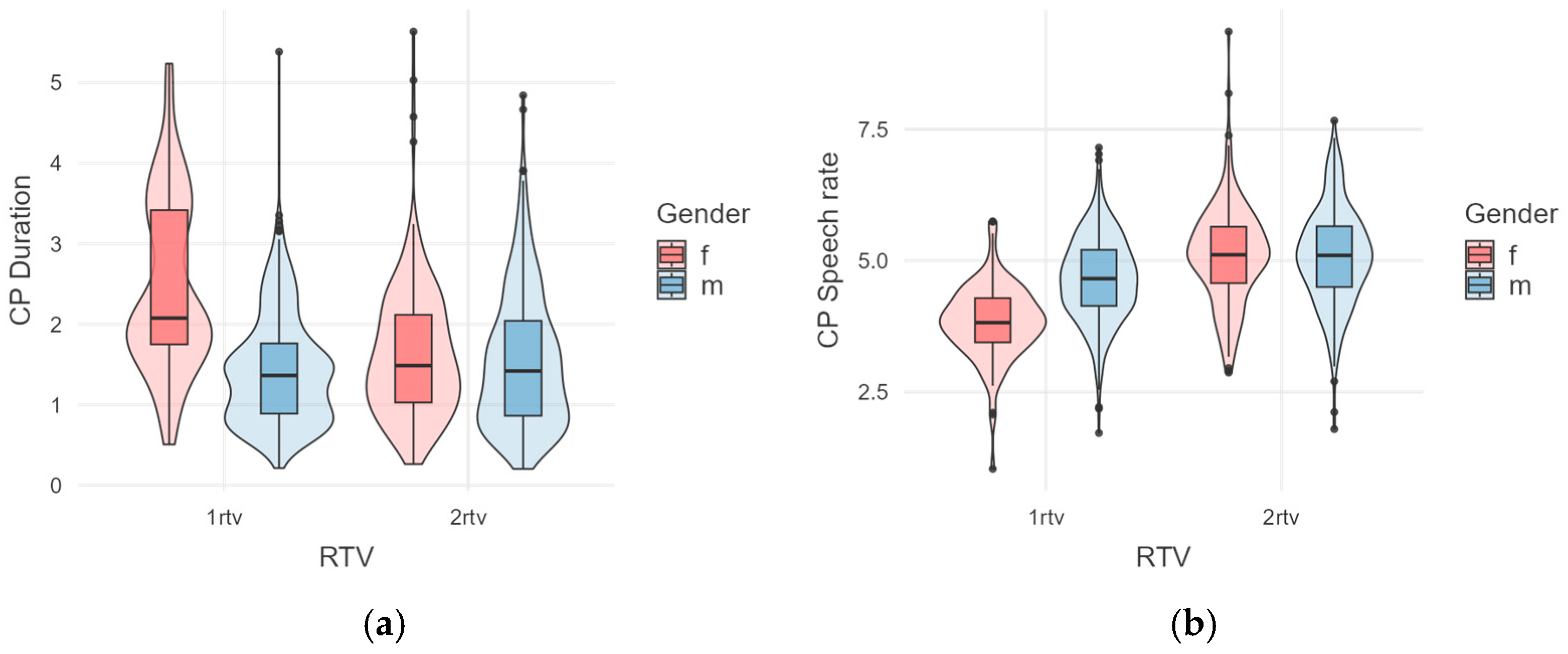

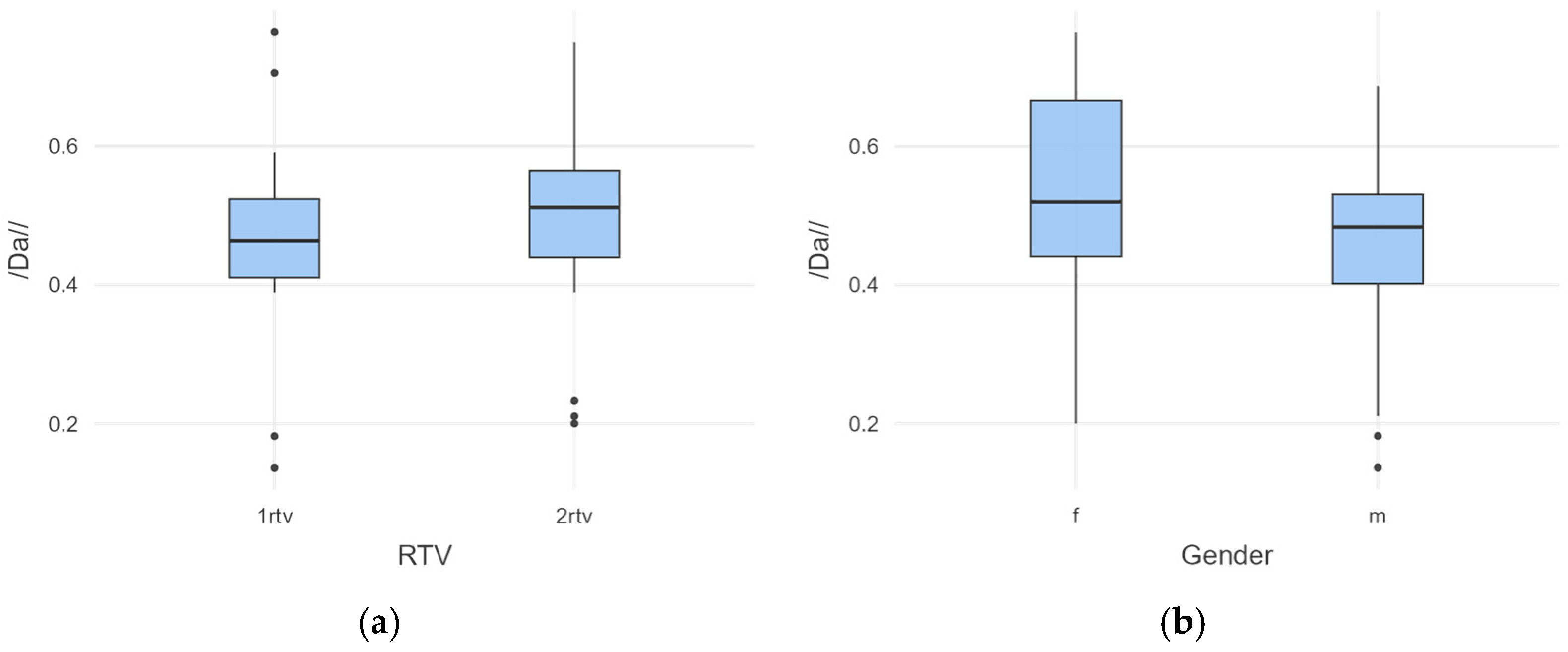

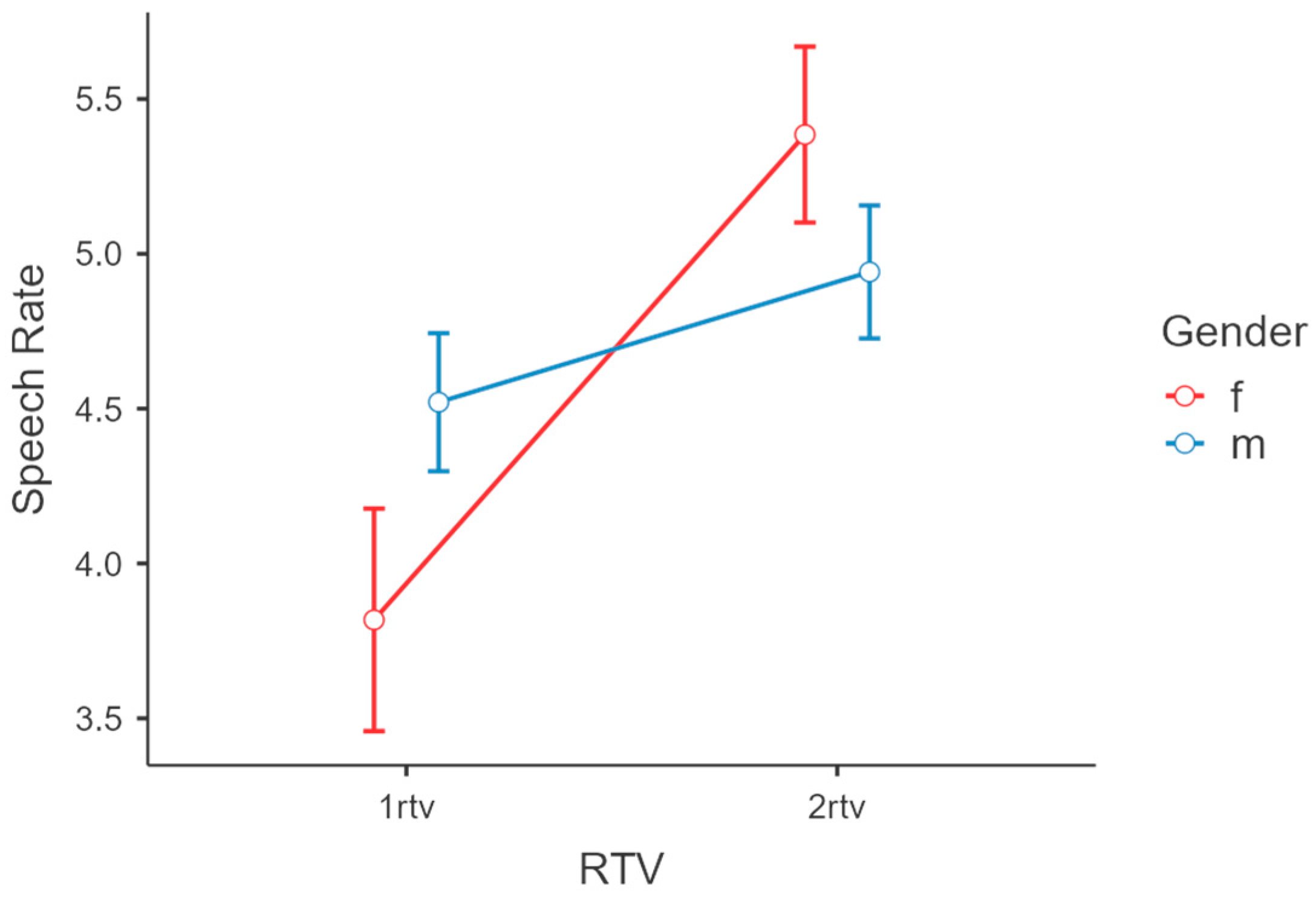

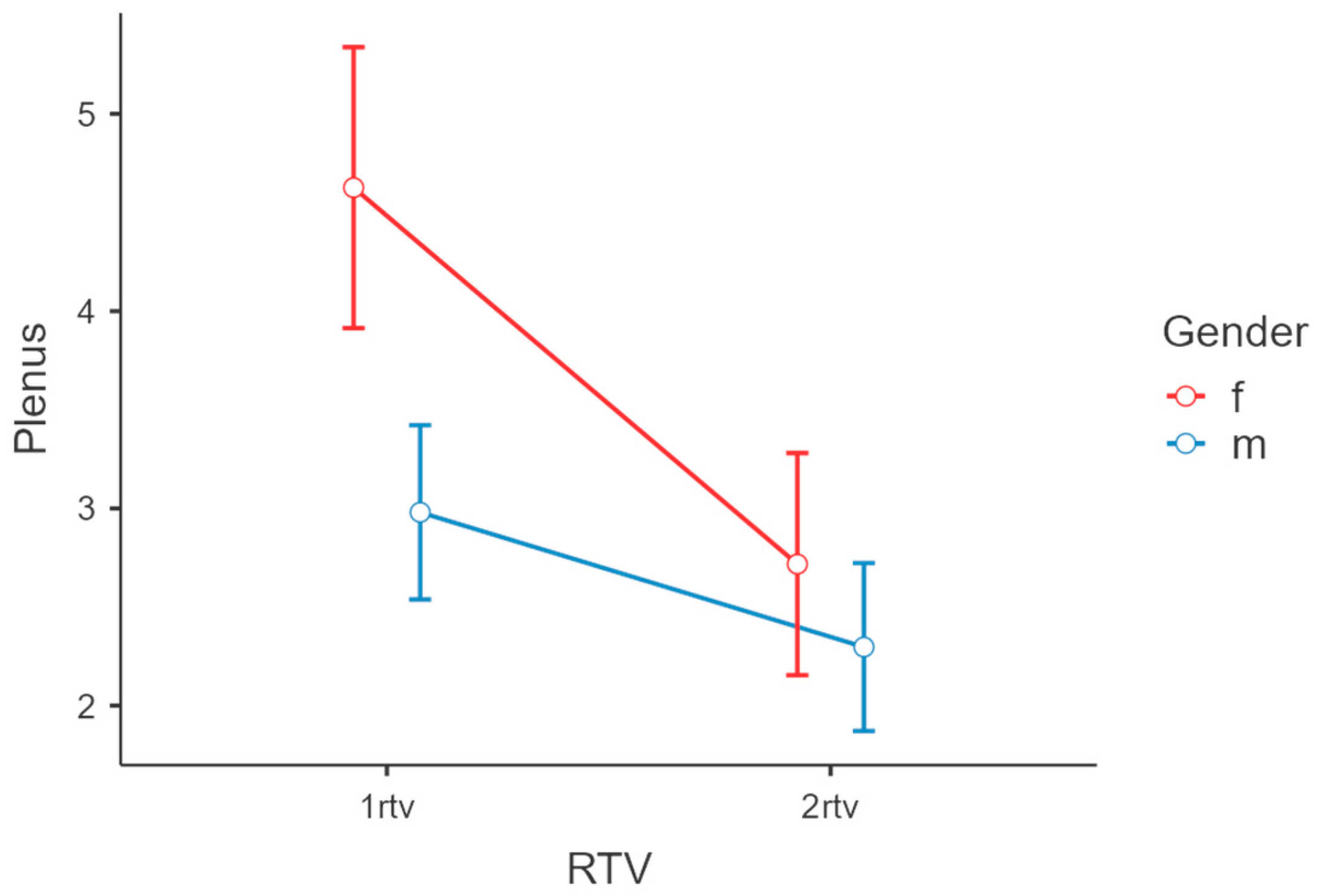

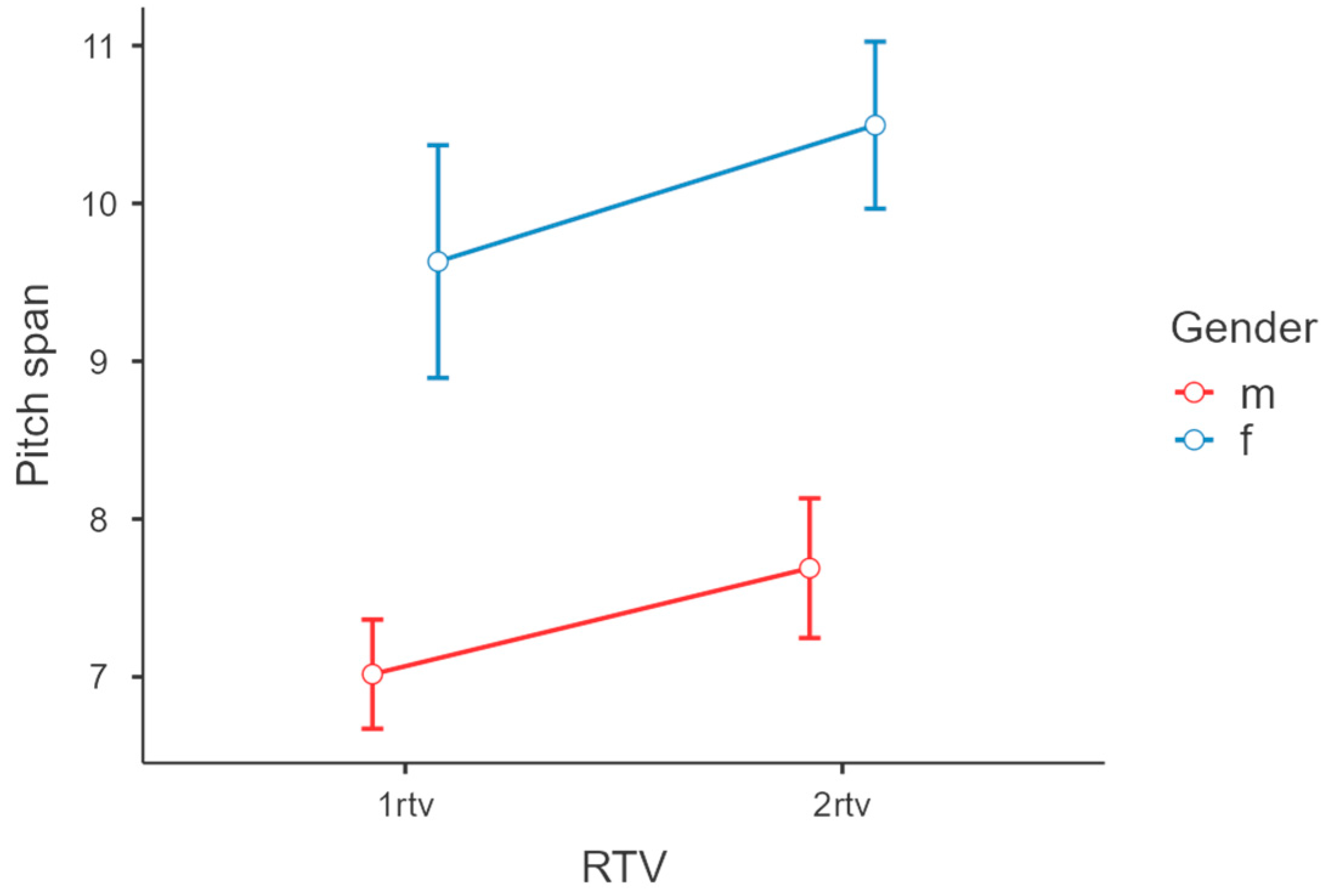

3.2. History of Spanish Poetry Reading: Radio-Television Eras and Gender

3.3. Periodization and Dates: A Stylistic–Chronological Framework

3.4. Effects of the Historical Phase and Gender on Poetry Reading

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

List of Poems

- Si mi voz muriera en tierra. In Marinero en tierra. Biblioteca Nueva, 1924.

- Balada del andaluz perdido. In Balada y canciones del Paraná. Losada, 1954.

- A Pablo Neruda, con Chile en el corazón. In Fustigada Luz. Seix Barral, 1980.

- Niñez. In Ámbito. Imprenta Sur, 1928.

- Nacimiento del amor. In Sombra del Paraíso. Adán, 1944.

- Rostro final. In Poemas de la consumación. Plaza y Janés, 1968.

- Los contadores de estrellas. In Poemas puros. Poemillas de la ciudad. Galatea, 1921.

- ¿Cómo era?. In Poemas puros. Poemillas de la ciudad. Galatea, 1921.

- Monstruos. In Hijos de la ira. Revista de Occidente, 1944.

- Glossa. In L’esperança, encara. In Jo era en el cant. Obra poètica 1913-1972. Labutxaca, 2012.

- L’esperança. In L’esperança, encara. In Jo era en el cant. Obra poètica 1913-1972. Labutxaca, 2012.

- Déjame esta voz. In Los placeres prohibidos. Poi in La realidad y el deseo. Ediciones del Árbol/Cruz y Raya, 1936; Fondo de Cultura Económica, 1958.

- Hacia la tierra. In Como quien espera el alba. Poi in La realidad y el deseo. Losada, 1947; Fondo de Cultura Económica, 1958.

- La vida. In Con las horas contadas. Poi in La realidad y el deseo (3ª ed.). Ediciones del Árbol/Cruz y Raya, 1958; Fondo de Cultura Económica, 1958.

- Amor. In Cántico inútil. M. Aguilar, 1936.

- Soledad. In Cántico inútil. M. Aguilar, 1936.

- Seré tuya sin ti el día que los sueños.... In Poesía a través del tiempo. Anthropos, 1991.

- Hallazgo. In Ansia de la gracia. Editorial Hispánica, 1945.

- Suma transida. In Iluminada tierra. Talleres Tipográficos de Santiago Julián Rodríguez, 1951.

- Confusión. In Iluminada tierra. Talleres Tipográficos de Santiago Julián Rodríguez, 1951.

- Carne de mi amante. In Poesía completa. Hiperión, 1986.

- Si no has muerto un instante. In Belleza Cruel. Torremozas, 1958.

- Nota autobiográfica. In Antología y poemas del suburbio, 1954.

- Tren de Tercera Edad. In Historia de Gloria. Editorial Cátedra, 1980.

- La manguera. In Un cuento, dos cuentos, tres cuentos. Os cuenta cuentos. Susaeta, 1995.

- Mañana de ayer, de hoy. In Moralidades. Joaquín Mortiz, 1966.

- Las afueras—4. In Compañeros de viaje. Joaquín Horta Editor, 1959.

- Las afueras—1. In Compañeros de viaje. Joaquín Horta Editor, 1959.

- A qué mirar. A qué permanecer. In Áspero mundo. Adonais, 1958.

- Muerte en el olvido. In Áspero mundo. Adonais, 1958.

- Ya nada ahora. In Deixis en fantasma. Hiperión, 1992.

- Canción del esposo soldado. In Viento del pueblo. Cátedra, [1936-37] 2006.

- Al soneto con mi alma. In Sonetos espirituales. Casa Editorial Calleja, 1917.

- El otoñado. In La estación total con Las canciones de la nueva luz (1923–1936). Visor, 2006.

- La perdida (Con la flor más alta, I). In La estación total con Las canciones de la nueva luz (1923–1936). Visor, 2006.

- De cómo y por qué se juntaron para llorar los ángeles y los pastores. In Poesía (Obras completas/1). Trotta, 1996.

- Me estoy quedando involuntario. In Poesía (Obras completas/1). Trotta, 1996.

- 2—Presagios. In Presagios. Biblioteca de Índice, 1924.

- Sin voz, desnuda. In Seguro azar. Revista de Occidente, 1929.

- Las oyes cómo piden realidades. In La voz a ti debida. Signo, 1933.

| 1 | Seven of them were previously considered for a preliminary qualitative and statistical study in Colonna et al. (2024). |

| 2 | https://voicesofspanishpoets.ugr.es/ (accessed on 19 April 2025). |

| 3 | The formula used is the following: (ΔE = i∈C1∑(xi − μ1)2 + i∈C2∑(xi − μ2)2 − i∈C∑(xi − μ)2). |

| 4 | We categorized by gender, considering the sexual division of voices, to ensure a proper classification of vocal types. |

| 5 | The formula used is the following: Y = β0 + β1(RTV) + β2(Gender). |

| 6 | The innovation started some twenty years earlier with authors like Salinas, Cernuda, and Conde we think corresponds to individual style and reception of the cultural surrounding contexts. In fact, their readings are dated to the period of the U.S. economic boom and the Mexican Stabilizing Development of the 1950s (Salinas and Cernuda) and the Spanish economic boom of the 1960s. These readings are contemporary with those of other authors whose reading style remained faithful to their time (such as Alonso, Alberti, Aleixandre, Arderiu, and de Champourcín). |

| 7 | The explicit reference to radio broadcasting in poems such as En el nombre de hoy [In Today’s Name] by Gil de Biedma and Alocución a las 23 [Address at 11 p.m.] by González provides further confirmation of the role played by radio in these authors. |

References

- Bagant, M. B., & Arboledas, L. (2011). The European exception: Historical evolution of Spanish radio as a cultural industry. Media International Australia, 141(1), 38–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Balsebre, M. (1994). El lenguaje radiofónico. Ediciones Cátedra. [Google Scholar]

- Barbosa, P. A. (2022). Pleasantness and wellbeing in poem declamation in European and Brazilian Portuguese depends mostly on pausing and voice quality. Frontiers in Communication, 7, 855177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barbosa, P. A. (2023). The dance of pauses in poetry declamation. Languages, 8(1), 76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barney, T. (1998). Style in performance: The prosody of poetic recitation [Ph.D. thesis, University of Lancaster]. [Google Scholar]

- Barney, T. (1999). Readers as text processors and performers: A new formula for poetic intonation. Discourse Processes, 28(2), 155–167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baumann, T., Hussein, H., & Meyer-Sickendiek, B. (2023). Free verse prosodies: Identifying and classifying spoken poetry using literary and computational perspectives (Rhythmicalizer). Digital Humanities Research, 7, 167–186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boersma, P., & Weenink, D. (1992–2025). Praat: Doing phonetics by computer (Version 6.4.27). [Computer software]. Available online: http://www.praat.org/ (accessed on 10 April 2025).

- Brazil, D. (1992). Listening to people reading. In M. Coulthard (Ed.), Advances in spoken discourse analysis (pp. 209–241). Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Byers, P. P. (1977). The contribution of intonation to the rhythm and melody of non-metrical English poetry [Ph.D. thesis, University of Wisconsin–Milwaukee]. [Google Scholar]

- Byers, P. P. (1979). A formula for poetic intonation. Poetics, 8, 367–380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Byers, P. P. (1980). Intonation prediction and the sound of poetry. Language and Style, 13(1), 3–14. [Google Scholar]

- Cauldwell, R. (1994). Discourse intonation and recordings of poetry: Philip Larkin reads “Mr Bleaney” [Ph.D. thesis, University of Birmingham]. [Google Scholar]

- Cauldwell, R., & Schourup, L. (1988). Discourse intonation and recordings of poetry: A study of Yeats’s readings. Language and Style, 21(4), 411–426. [Google Scholar]

- Chatman, S. (1956). Robert Frost’s Mowing: An inquiry into prosodic structure. Kenyon Review, 18, 421–428. [Google Scholar]

- Chatman, S. (1966). On the intonational fallacy. Quarterly Journal of Speech, 52, 283–286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clement, T. (2013). Distant Listening or Playing Visualisations Pleasantly with the Eyes and Ears. Digital Studies/le Champ Numérique, 3(2). [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cohen, J. (1966). Structures du langage poétique. Flammarion. [Google Scholar]

- Colonna, V. (2017). Prosodie del «Congedo»: Analisi fonetica comparativa di dodici letture [Unpublished Master’s thesis, University of Turin]. [Google Scholar]

- Colonna, V. (2022). Voices of Italian Poets: Storia e analisi fonetica della lettura della poesia italiana del Novecento. Dell’Orso. [Google Scholar]

- Colonna, V. (2024). Voices of Spanish poets. Available online: https://voicesofspanishpoets.ugr.es/ (accessed on 1 April 2025).

- Colonna, V. (in press). Le Modèle «Voices of Italian Poets» Adapté Aux Poètes Français: Yves Bonnefoy, Jean-Pierre Lemaire, Anne Portugal et Jacqueline Risset. In A. Lang, M. Murat, & C. Pardo (Eds.), Archives sonores de la poésie II. Les Presses du réel. [Manuscript accepted for publication].

- Colonna, V., Pamies Bertrán, A., & Damato, S. (2024). Towards a phonetic history of the voices of Spanish poets. Journal of Experimental Phonetics, 33, 7–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Colonna, V., & Romano, A. (2023a). Prose or poetry? A perceptive phonetic study. In R. Skarnitzl, & J. Volín (Eds.), Proceedings of the 20th International Congress of Phonetic Sciences (ICPhS), Prague, Czech Republic, 7–11 August 2003 (pp. 347–351). Guarant International. Available online: https://hdl.handle.net/2318/1935853 (accessed on 10 March 2025).

- Colonna, V., & Romano, A. (2023b). The prosody of Seamus Heaney: A phonetic study on some original readings. In Proceedings of the 13th Nordic Prosody Conference: Applied and Multimodal Prosody Research (pp. 238–244). Sciendo/de Gruyter. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Colonna, V., & Romano, A. (2023c). VIP—RADAR: A model for the phonetic study of poetry reading. In R. Skarnitzl, & J. Volín (Eds.), Proceedings of the 20th International Congress of Phonetic Sciences (ICPhS) (pp. 594–598). Guarant International. Available online: https://iris.unito.it/handle/2318/1935854 (accessed on 10 March 2025).

- Colonna, V., Romano, A., & De Iacovo, V. (2019). Prosodic features of the Italian poetry: A phonetic study on some readings. In S. Calhoun, P. Escudero, M. Tabain, & P. Warren (Eds.), Proceedings of the 19th International Congress of Phonetic Sciences, Melbourne, Australia, 5–9 August 2019 (pp. 3383–3387). Australasian Speech Science and Technology Association Inc. Available online: http://hdl.handle.net/2318/1713480 (accessed on 10 March 2025).

- Colonna, V., & Román Montes de Oca, D. (2024a). Aggregation of 6 PRAAT tiers. Praat script. Available online: https://github.com/DomingoRomanMontesDeOca/vip_vsp_colonna_valentina/ (accessed on 19 April 2025).

- Colonna, V., & Román Montes de Oca, D. (2024b, July 3–5). El desafío de la prosodia: Un estudio fonético-métrico sobre 30 lecturas de Lorca. 1st International Conference on Lyric Theory and Comparative Poetics, Salamanca, Spain. [Google Scholar]

- Colonna, V., & Román Montes de Oca, D. (2024c). VIP-VSP-radar data extraction for poem phonetic analysis. Praat script. Available online: https://github.com/DomingoRomanMontesDeOca/vip_vsp_colonna_valentina/ (accessed on 19 April 2025).

- Colonna, V., & Román Montes de Oca, D. (2024d). VIP-VSP label correction. Praat script. Available online: https://github.com/DomingoRomanMontesDeOca/vip_vsp_colonna_valentina/ (accessed on 19 April 2025).

- Crystal, D. (1975). Intonation and metrical theory. In The English tone of voice: Essays in intonation, prosody and paralanguage (pp. 105–124). Edward Arnold. [Google Scholar]

- Dotto, S. (2019). Voci d’Archivio. Fonografia e culture dell’ascolto nell’Italia tra le due guerre. Maltemi. [Google Scholar]

- Eco, U. (1983). La moltiplicazione dei media. In Sette anni di desiderio (pp. 212–216). Bompiani. [Google Scholar]

- Eco, U. (1990). A guide to the neo-television of the 1980s. In Z. G. Barański, & R. Lumley (Eds.), Culture and conflict in postwar Italy (pp. 234–248). Palgrave Macmillan. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elmer, D. (2013). The Milman Parry collection of oral literature. Oral Tradition, 2, 341–354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fabb, N., & Halle, M. (2008). Meter in poetry: A new theory. Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fabb, N., & Halle, M. (2012). Grouping in the stressing of words, in metrical verse, and in music. In P. Rebuschat, M. Rohrmeier, J. A. Hawkins, & I. Cross (Eds.), Language and music as cognitive systems (pp. 4–21). Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Fant, G., Kruckenberg, A., & Nord, L. (1991). Stress patterns and rhythm in the reading of prose and poetry with analogies to music performance. In J. Sundberg, L. Nord, & R. Carlson (Eds.), Music, language, speech and brain (pp. 380–407). Macmillan. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fox, J., & Weisberg, S. (2023). car: Companion to Applied Regression [R package]. Available online: https://cran.r-project.org/package=car (accessed on 30 March 2025).

- Fónagy, I. (1983). La vive voix. Essay de psycho-phonétique. Payot. [Google Scholar]

- Fónagy, I. (2000). Languages and iconicity. In P. Violi (Ed.), Phonosymbolism and poetic language (pp. 123–138). Brepols. [Google Scholar]

- Funkhouser, L. B. (1979). Acoustic rhythm in Randall Jarrell’s “The death of the ball turret gunner”. Poetics, 8, 381–403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gafni, C., & Tsur, R. (2017). Softened voice quality in poetry reading: An acoustic study. Style, 51(4), 456–481. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giannini, A. (2004). Analisi acustica del parlato televisivo: Implicazioni nei modelli linguistici. In P. Cosi (Ed.), I Convegno nazionale dell’Associazione italiana di Scienze della voce (AISV) (pp. 49–61). EDK Editore. [Google Scholar]

- Giannini, A., & Pettorino, M. (1999). I cambiamenti dell’italiano radiofonico negli ultimi 50 anni: Aspetti ritmico-prosodici e segmentali. In R. Delmonte, & A. Bristot (Eds.), “Aspetti computazionali in fonetica, linguistica e didattica delle lingue: Modelli e algoritmi”. Atti delle 9e Giornate di Studio del GFS, 29 (pp. 65–81). Esagrafica. [Google Scholar]

- Grammont, M. (1913). Le vers français: Ses moyens d’expression, son harmonie. Delagrave. [Google Scholar]

- Grammont, M. (1933). Traité de phonétique. Delagrave. [Google Scholar]

- Greenwood, P. E., & Nikulin, M. S. (1996). A guide to chi-squared testing. Wiley-Interscience. [Google Scholar]

- Jakobson, R. (1966). Saggi di linguistica generale. Feltrinelli. [Google Scholar]

- Jamovi Project. (2024). Jamovi (Version 2.5) [Computer software]. Available online: https://www.jamovi.org/ (accessed on 30 March 2025).

- Kruckenberg, A., Fant, G., & Nord, L. (1991). Rhythmical structures in poetry reading. In J. Sundberg, L. Nord, & R. Carlson (Eds.), Music, language, speech and brain (pp. 34–47). Macmillan Education. [Google Scholar]

- Lang, A. (2019). Why we need online archives of recorded poetry. RiCognizioni, 6(11), 169–176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lenth, R. (2023). emmeans: Estimated marginal means, aka least-squares means [R package]. Available online: https://cran.r-project.org/package=emmeans (accessed on 30 March 2025).

- Lerdahl, F. (2003). Essay: Two ways in which music relates to the world. Music Theory Spectrum, 25(2), 367–373. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lerdahl, F., & Halle, J. (1991). Some lines of poetry viewed as music. In J. Sundberg, L. Nord, & R. Carlson (Eds.), Music, language, speech and brain (pp. 43–67). Palgrave Macmillan. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Loesch, K. T. (1965). Literary ambiguity and oral performance. Quarterly Journal of Speech, 51, 258–267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Loesch, K. T. (1966). A reply to Mr. Chatman. Quarterly Journal of Speech, 52, 286–289. [Google Scholar]

- López-Escobar, E., & Faus-Belau, A. (1985). Broadcasting in Spain: A history of heavy-handed state control. West European Politics, 8(2), 122–136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- MacArthur, M. (2016). Monotony, the churches of poetry reading, and sound studies. PMLA, 131(1), 38–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- MacArthur, M., Zellou, G., & Miller, L. M. (2018). Beyond poet voice: Sampling the (non-) performance styles of 100 American poets. Journal of Cultural Analytics, 3(1). [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Merlo, P. (2010). Peces en la tierra: Antología de mujeres poetas en torno a la Generación del 27. Fundación José Manuel Lara. [Google Scholar]

- Meyer-Sickendiek, B., Hussein, H., & Baumann, T. (2017). Rhythmicalizer: Data analysis for the identification of rhythmic patterns in readout poetry. In M. Eibl, & M. Gaedke (Eds.), INFORMATIK 2017 (pp. 2189–2200). Gesellschaft für Informatik. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meza Valdez, A. (2020). Sound works: Prototyping a digital audio repository for sound poetics in Mexico [Ph.D. thesis, Concordia University]. [Google Scholar]

- Mistrorigo, A. (2018). Phonodia: La voz de los poetas, uso crítico de sus grabaciones y entrevistas. Ca’ Foscari. [Google Scholar]

- Mukafovsky, J. (1933). Intonation comme facteur de rythme poétique. Archives Neerlandaises de Phonétique Expérimentale, 8–9, 153–165. [Google Scholar]

- Mustazza, C. (2019). Speech labs: Language experiments, early poetry audio archives, and the poetic record [Ph.D. thesis, University of Pennsylvania]. Available online: https://repository.upenn.edu/handle/20.500.14332/30493 (accessed on 10 March 2025).

- Navarro Tomás, T. (1973a). La inscripción de El Contemplado de Pedro Salinas. In Los poetas en sus versos: Desde Jorge Manrique a García Lorca (pp. 337–344). Maior. [Google Scholar]

- Navarro Tomás, T. (1973b). La intuición rítmica de Federico García Lorca. In Los poetas en sus versos: Desde Jorge Manrique a García Lorca (pp. 355–378). Maior. [Google Scholar]

- Nord, L., Kruckenberg, A., & Fant, G. (1990). Some timing studies of prose, poetry, and music. Speech Communication, 9(5/6), 477–483. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ong, W. J. (1967). The presence of the word: Some prolegomena for cultural and religious history. Yale University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Pamies Bertrán, A. (1999). Prosodic typology. Language Design, 2, 103–131. [Google Scholar]

- Pamies Bertrán, A. (2010). Quelques malentendus à propos du concept de rythme en linguistique. In M. Russo (Ed.), Prosodic universals: Comparative studies in rhythmic modeling and rhythm typology (pp. 45–60). Aracne. [Google Scholar]

- Pettorino, M., & Giannini, A. (1994). Aspetti prosodici del parlato radiofonico. In Gli aspetti prosodici dell’italiano. Atti delle IV Giornate di Studio del Gruppo di Fonetica Sperimentale (GFS), 21 (pp. 19–28). Esagrafica. [Google Scholar]

- R Core Team. (2023). R: A language and environment for statistical computing (Version 4.3) [Computer software]. Available online: https://cran.r-project.org (accessed on 30 March 2025).

- Robin, R., & Herring, E. (2019, July 9–11). Post-Soviet newscast intonation. V Congreso Internacional «Jornadas Andaluzas de Eslavística», Granada, Spain. [Google Scholar]

- Rodero Antón, E. (2003). Locución radiofónica. Instituto Oficial de Radio y Televisión. [Google Scholar]

- Rodero Antón, E. (2012). A comparative analysis of speech rate and perception in radio bulletins. Text & Talk, 32(3), 391–411. Available online: http://hdl.handle.net/10230/27802 (accessed on 30 March 2025).

- Rumsey, L. (2015). Da-DA-da-da-da: Intonation and poetic form. Thinking Verse, 5, 15–49. [Google Scholar]

- Schauffler, N., Schubö, F., Bernhart, T., Eschenbach, G., Koch, J., Richter, S., Viehhauser, G., Vu, T., Wesemann, L., & Kuhn, J. (2022). Prosodic realisation of enjambment in recitations of German poetry. In S. Frota, M. Cruz, & M. Vigário (Eds.), Proceedings of speech prosody 2022, Lisbon, Portugal, 23–26 May 2022 (pp. 530–534). ISCA. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schirru, G. (2002). Correlati acustici del ritmo linguistico. In F. Buffoni (Ed.), Ritmologia (pp. 267–306). Marcos y Marcos. [Google Scholar]

- Servien, P. (1930). Les rythmes comme introduction physique à l’esthétique. Boivin. [Google Scholar]

- Sievers, E. (1912). Rhythmisch-melodische Studien. Teubner. [Google Scholar]

- Taglicht, J. (1971). The function of intonation in English verse. Language and Style, 4, 116–122. [Google Scholar]

- Tivadar, H. (2017). Speech rate in phonetic-phonological analysis of public speech (Using the example of political and media speech). Journal of Linguistics/Jazykovedný časopis, 68(1), 23–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsur, R. (1997a). Douglas Hodge reading Keats’s Elgin Marbles sonnet. Style, 31(1), 34–57. [Google Scholar]

- Tsur, R. (1997b). Sound affects of poetry: Critical impressionism, reductionism and cognitive poetics. Pragmatics and Cognition, 5(2), 283–304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsur, R. (1997c). To be or not to be—That is the rhythm: A cognitive-empirical study of poetry in the theatre. Assaph, 13, 95–122. [Google Scholar]

- Tsur, R., & Gafni, C. (2022). Sound-emotion interaction in poetry: Rhythm, phonemes, voice quality. John Benjamins Publishing Company. [Google Scholar]

- Wagner, P. (2012). Meter specific timing and prominence in German poetry and prose. In O. Niebuhr (Ed.), Prosodies—Context, function, communication (pp. 219–236). De Gruyter. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wagner, P., & Betz, S. (2023). Effects of meter, genre, and experience on pausing, lengthening, and prosodic phrasing in German poetry reading. In N. Harte, J. Carson-Berndsen, & G. Jones (Eds.), Proceedings of Interspeech 2023, Dublin, Ireland, 20–24 August 2023 (pp. 2538–2542). ISCA. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zumthor, P. (1983). Introduction à la poésie orale. Éditions du Seuil. [Google Scholar]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Colonna, V. How Has Poets’ Reading Style Changed? A Phonetic Analysis of the Effects of Historical Phases and Gender on 20th Century Spanish Poetry Reading. Languages 2025, 10, 255. https://doi.org/10.3390/languages10100255

Colonna V. How Has Poets’ Reading Style Changed? A Phonetic Analysis of the Effects of Historical Phases and Gender on 20th Century Spanish Poetry Reading. Languages. 2025; 10(10):255. https://doi.org/10.3390/languages10100255

Chicago/Turabian StyleColonna, Valentina. 2025. "How Has Poets’ Reading Style Changed? A Phonetic Analysis of the Effects of Historical Phases and Gender on 20th Century Spanish Poetry Reading" Languages 10, no. 10: 255. https://doi.org/10.3390/languages10100255

APA StyleColonna, V. (2025). How Has Poets’ Reading Style Changed? A Phonetic Analysis of the Effects of Historical Phases and Gender on 20th Century Spanish Poetry Reading. Languages, 10(10), 255. https://doi.org/10.3390/languages10100255