On the Design of Aeroelastically Scaled Models of High Aspect-Ratio Wings

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Methodology

2.1. Aeroelastic Scaling

- 1.

- Density (), Velocity (v) and Span (b);

- 2.

- Frequency (), Mass (m) and Span (b);

- 3.

- Pressure (p), Density () and Span (b).

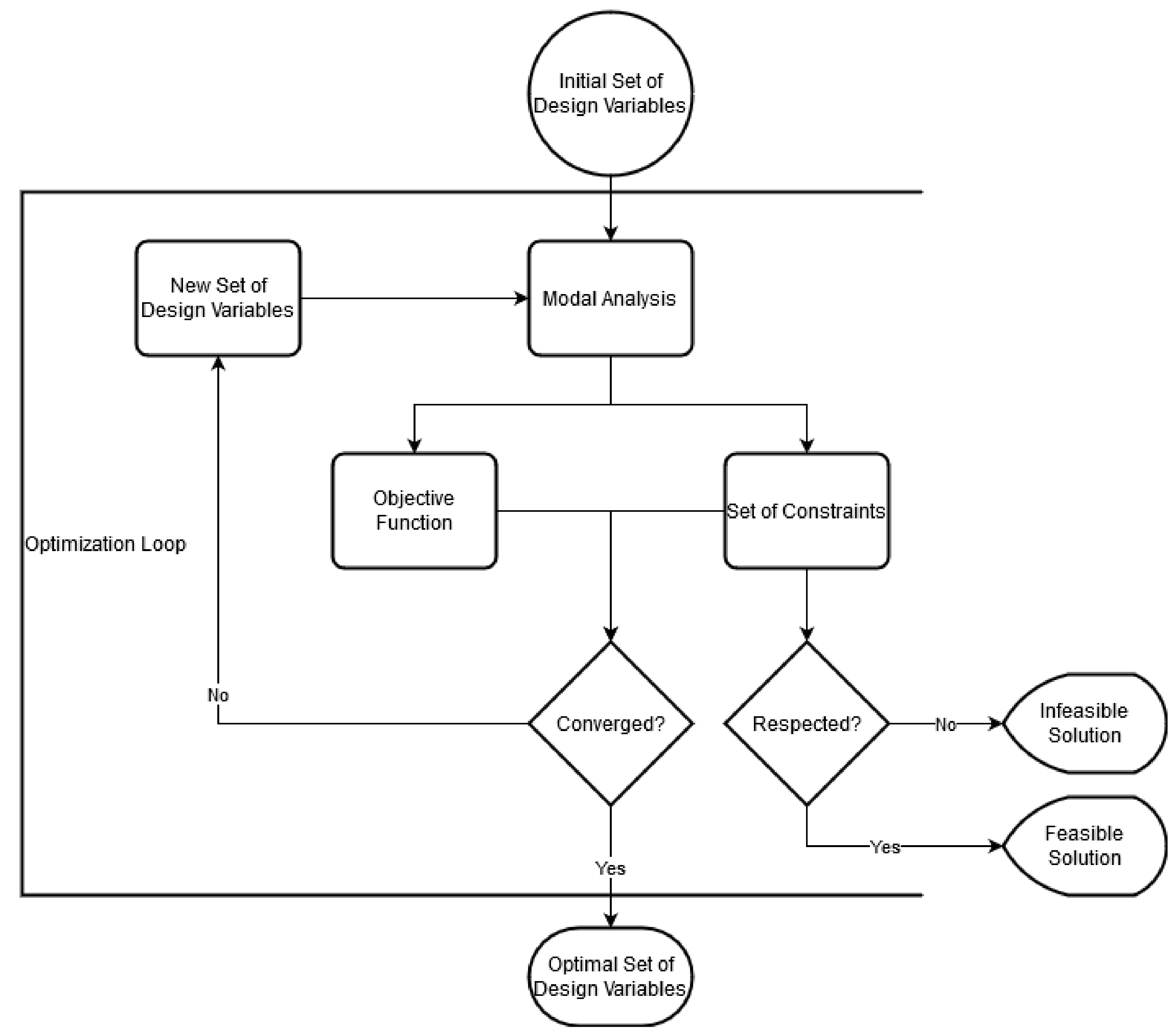

2.2. Methodology

- 1.

- Build a full size wing model in the aeroelastic framework and run time domain simulations for three flight conditions (cruise, hold and alternate);

- 2.

- Derive the scaling factors and the resulting target parameters to be matched by the sub-scale models, considering 3 different sets of primary quantities;

- 3.

- Apply a scaling methodology resorting to optimization with the aim at reaching the same dynamic scaling of the full size wing model;

- 4.

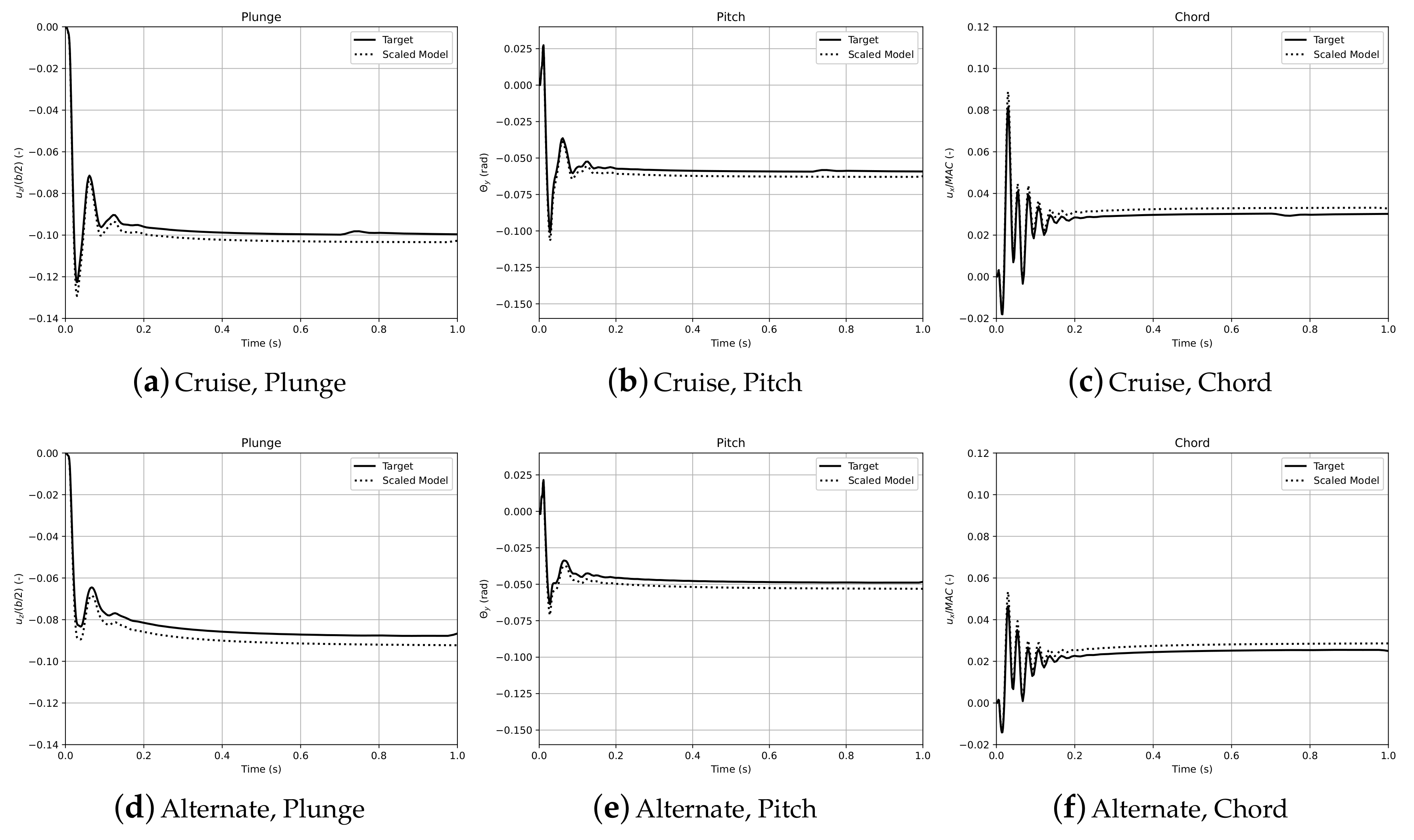

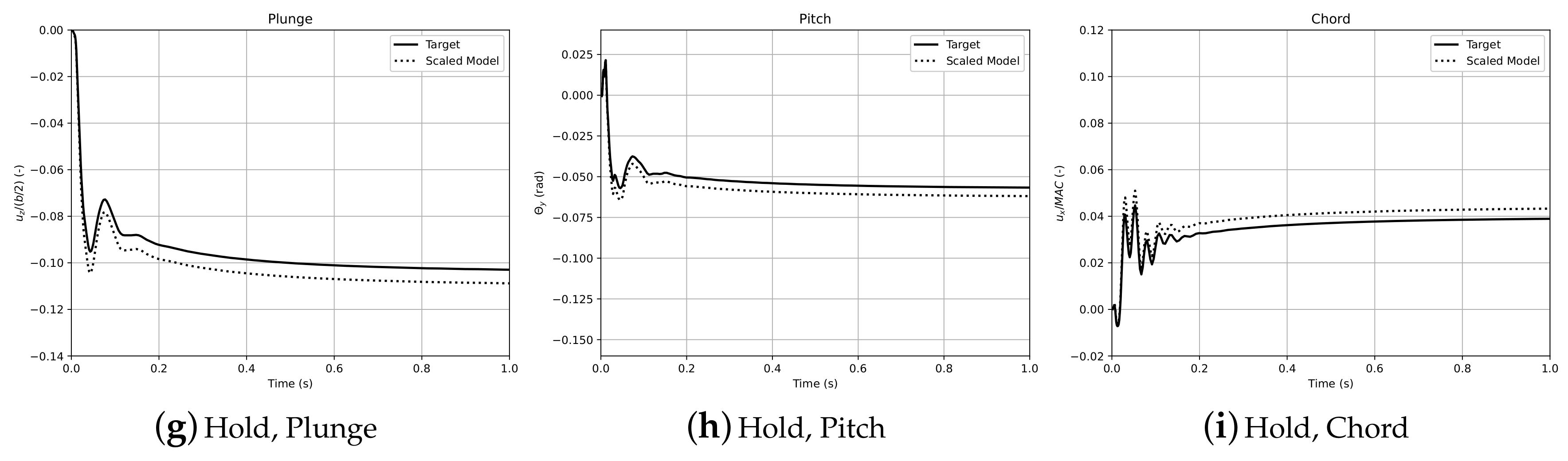

- Run nonlinear unsteady simulations to predict the nonlinear aeroelastic response of the 3 scaled models and compare with the responses estimated for the initial wing model, i.e., the target responses for cruise, hold and alternate flight conditions.

2.3. Aeroelastic Framework

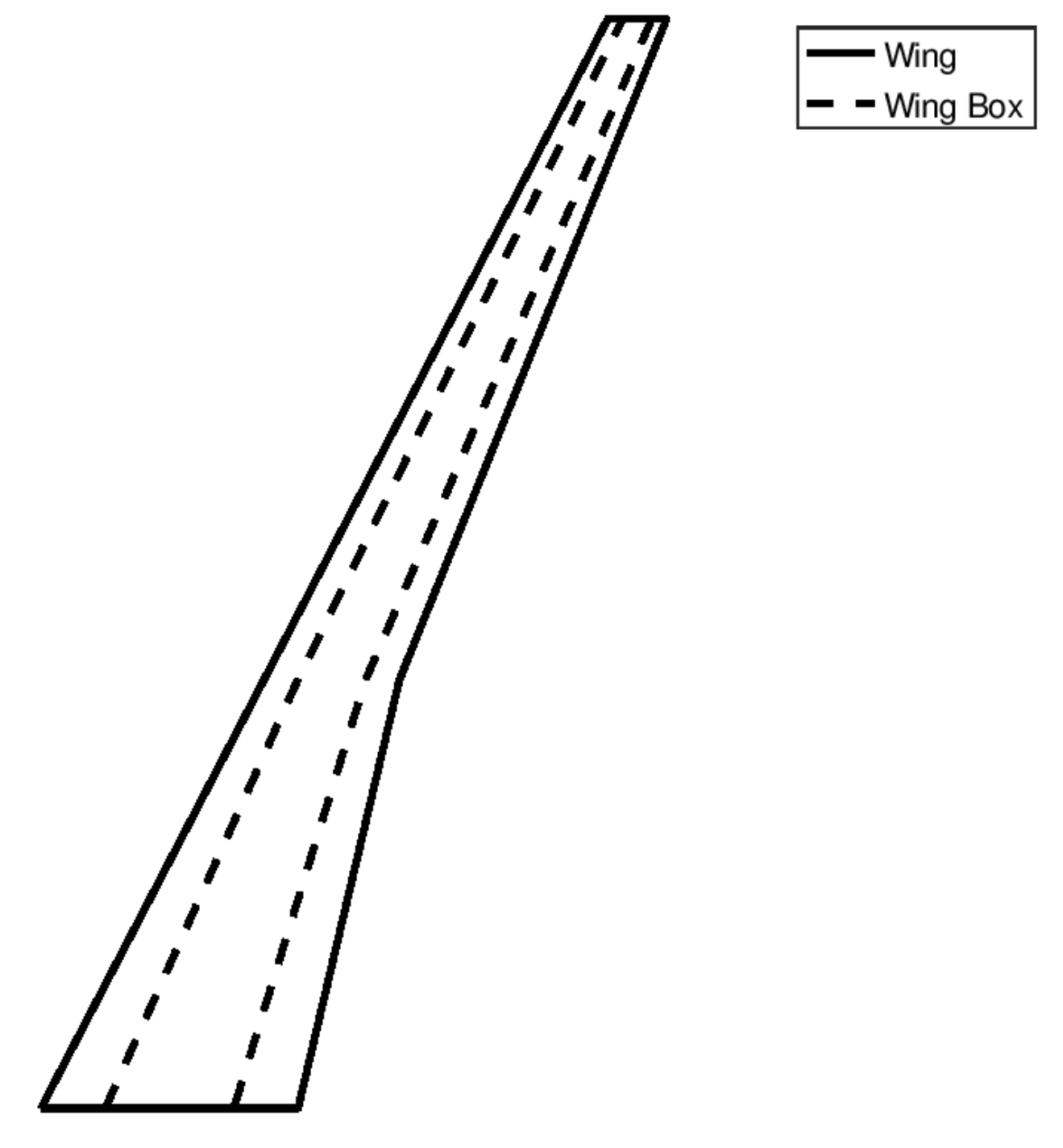

3. Wing Model

3.1. Full Size Model

3.2. Reduced Scale Models

- Geometric similarity is achieved with all the Sets of primary quantities at an external level, while only Set 3 provides internal geometric similarity due to the possibility of manufacturing the wing box structure using the same material (with thickness of 2.8 mm and 0.56 mm);

- Reynolds number is not matched using any of the Sets of primary quantities (Set 3 is the one that is closest to the full size model) which means that the viscous effects will not be sufficiently represented in the sub-scale models, especially for the Set 2 for which a low Reynolds number was derived; as mentioned before Reynolds number is not considered to be of major importance for aeroelastic problems on the wing [31], although if deemed important for a given flight condition skin roughness can be changed to induce transition to turbulent flow as suggested in [30];

- Compressibility effects will only be accurately represented when using Set 3; it is worth noting that the interaction between viscous and compressibility effects, if exists, will not be adequately captured since Reynolds number is not matched;

- Dynamic similarity is immediately achieved by using Set 3 of primary quantities, because besides geometric similarity being possible both pressure and density are selected as primary quantities which enables the usage of the same material as in the full size model;

- Froude number similarity is another similarity parameter that is not achieved with any of the Sets of primary quantities, although Set 2 provides the closest value.

4. Results

4.1. Aeroelastic Scaling

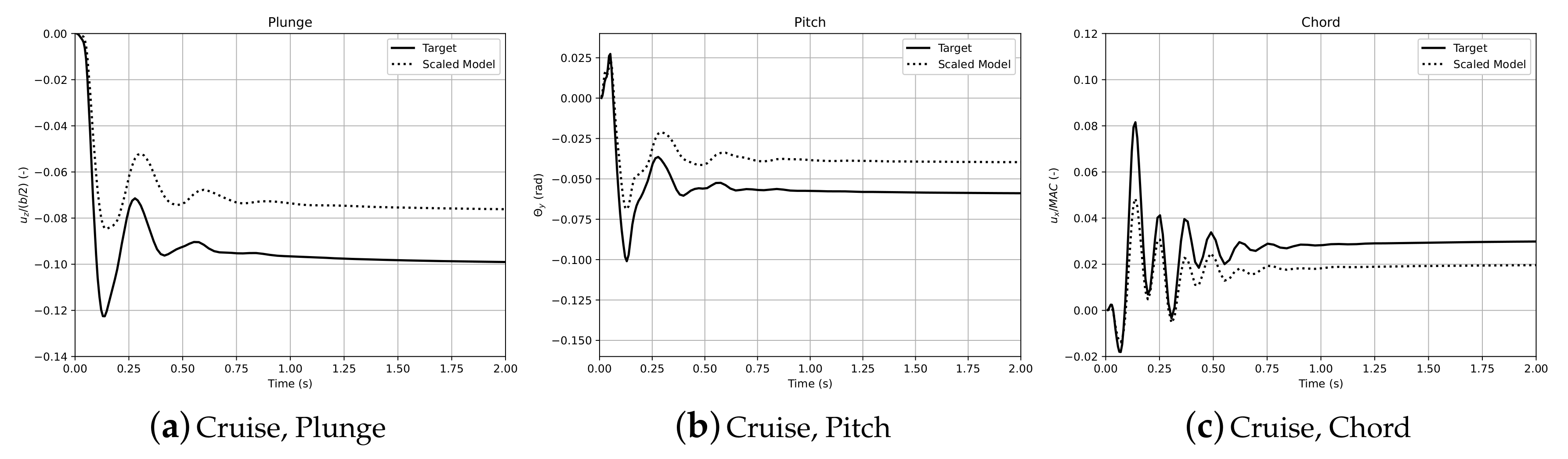

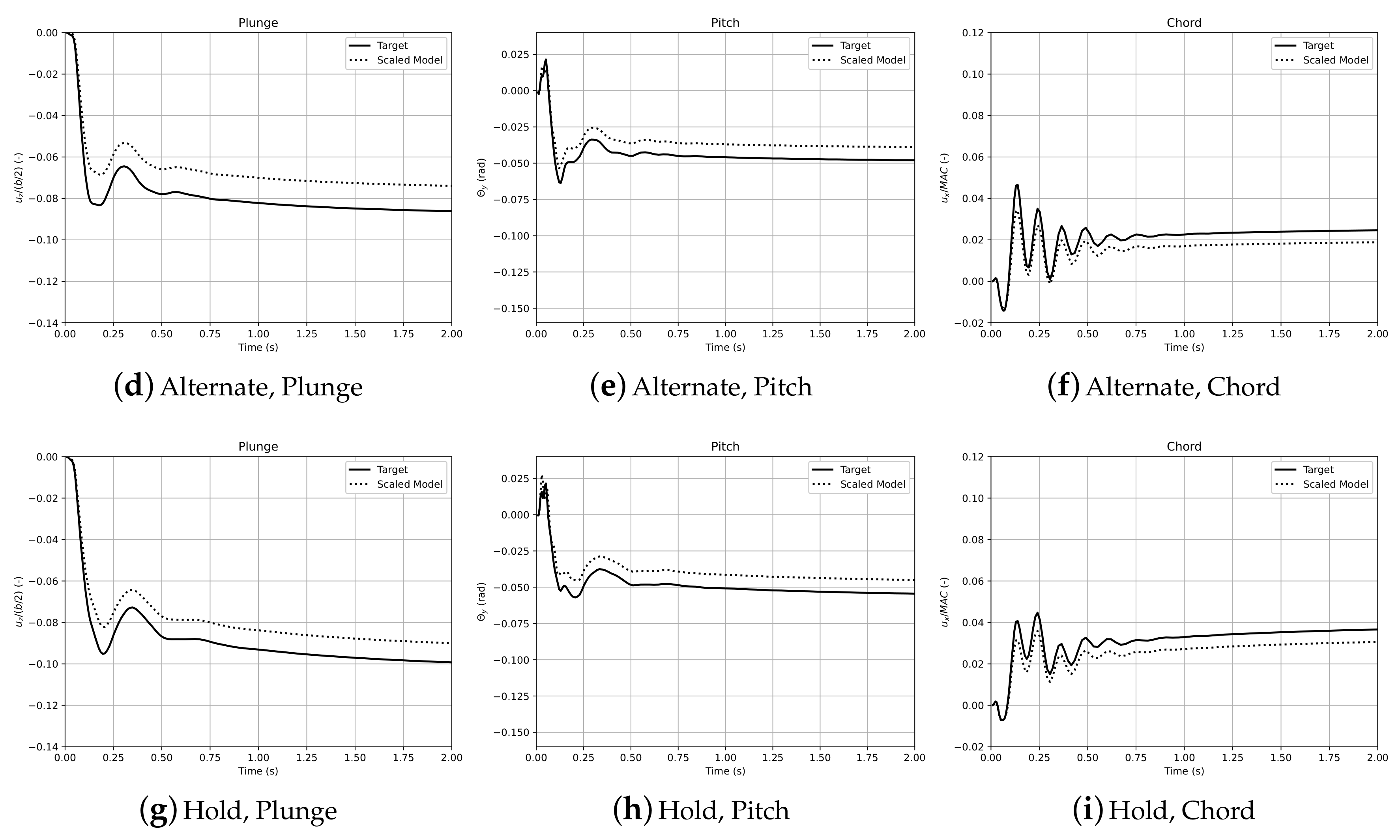

4.2. Aeroelastic Response

5. Concluding Remarks

Author Contributions

Funding

Conflicts of Interest

Nomenclature

| aerodynamic damping matrix | |

| aerodynamic stiffness matrix | |

| aerodynamic mass matrix | |

| b | wing span |

| damping matrix | |

| moment scaling factors | |

| f | frequency |

| F | force |

| Fr | Froude number |

| g | gravity acceleration |

| I | inertia |

| k | scaling factors |

| force scaling factors | |

| inertia scaling factors | |

| length scaling factors | |

| mass scaling factors | |

| moment scaling factors | |

| pressure scaling factors | |

| time scaling factors | |

| velocity scaling factors | |

| density scaling factors | |

| frequency scaling factors | |

| stiffness matrix | |

| m | mass |

| M | moment |

| mass matrix | |

| Ma | Mach number |

| MAC | Modal Assurance Criteria |

| p | pressure |

| Re | Reynolds number |

| t | time |

| v | velocity |

| x | set of design variables |

| vector of displacements | |

| vector of velocities | |

| vector of accelerations | |

| reduced frequency | |

| density | |

| matrix with a set of mode shapes | |

| natural frequency |

References

- Patil, M.; Hodges, D. On the importance of aerodynamic and structural geometrical nonlinearities in aeroelastic behavior of high-aspect-ratio wings. J. Fluids Struct. 2004, 19, 905–915. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, D.; Dowell, E. Effects of geometric structural nonlinearity on flutter and limit cycle oscillations of high-aspect-ratio wings. J. Fluids Struct. 2004, 19, 291–306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cesnik, C.E.; Palacios, R.; Reichenbach, E.Y. Reexamined Structural Design Procedures for Very Flexible Aircraft. J. Aircr. 2014, 51, 1580–1591. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsushima, N.; Su, W. Flutter suppression for highly flexible wings using passive and active piezoelectric effects. Aerosp. Sci. Technol. 2017, 65, 78–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Souza Siqueira Versiani, T.; Silvestre, F.J.; Guimarães Neto, A.B.; Rade, D.A.; Annes da Silva, R.G.; Donadon, M.V.; Bertolin, R.M.; Silva, G.C. Gust load alleviation in a flexible smart idealized wing. Aerosp. Sci. Technol. 2019, 86, 762–774. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Modaress-Aval, A.H.; Bakhtiari-Nejad, F.; Dowell, E.H.; Peters, D.A.; Shahverdi, H. A comparative study of nonlinear aeroelastic models for high aspect ratio wings. J. Fluids Struct. 2019, 85, 249–274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amato, E.; Polsinelli, C.; Cestino, E.; Frulla, G.; Joseph, N.; Carrese, R.; Marzocca, P. HALE wing experiments and computational models to predict nonlinear flutter and dynamic response. Aeronaut. J. 2019, 123, 912–946. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cestino, E.; Frulla, G.; Spina, M.; Catelani, D.; Linari, M. Numerical simulation and experimental validation of slender wings flutter behaviour. Proc. Inst. Mech. Eng. Part G J. Aerosp. Eng. 2019, 233, 5913–5928. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Riso, C.; Ghadami, A.; Cesnik, C.E.S.; Epureanu, B.I. Data-Driven Forecasting of Postflutter Responses of Geometrically Nonlinear Wings. AIAA J. 2020, 58, 2726–2736. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Afonso, F.; Vale, J.; Oliveira, É.; Lau, F.; Suleman, A. A review on non-linear aeroelasticity of high aspect-ratio wings. Prog. Aerosp. Sci. 2017, 89, 40–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jonsson, E.; Riso, C.; Lupp, C.A.; Cesnik, C.E.; Martins, J.R.; Epureanu, B.I. Flutter and post-flutter constraints in aircraft design optimization. Prog. Aerosp. Sci. 2019, 109, 100537. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, C.; Zhang, W. Transonic aeroelasticity: A new perspective from the fluid mode. Prog. Aerosp. Sci. 2020, 113, 100596. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coutinho, C.P.; Baptista, A.J.; Dias Rodrigues, J. Reduced scale models based on similitude theory: A review up to 2015. Eng. Struct. 2016, 119, 81–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Casaburo, A.; Petrone, G.; Franco, F.; De Rosa, S. A Review of Similitude Methods for Structural Engineering. Appl. Mech. Rev. 2019, 71, 030802. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, W. Models for wind tunnel tests based on additive manufacturing technology. Prog. Aerosp. Sci. 2019, 110, 100541. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blair, M.; Garmann, D.; Canfield, R.; Bond, V.; Pereira, P.; Suleman, A. Non-Linear Aeroelastic Scaling of a Joined-Wing Concept. In Proceedings of the 48th AIAA/ASME/ASCE/AHS/ASC Structures, Structural Dynamics, and Materials Conference, Honolulu, HI, USA, 23–26 April 2007. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Richards, J.; Suleman, A. Aeroelastic scaling of unconventional joined wing concept for exploration of gust load response. In Proceedings of the International Forum on Aeroelasticity and Structural Dynamics IFASD, Seattle, WA, USA, 21–25 June 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Bond, V.L.; Canfield, R.A.; Suleman, A.; Blair, M. Aeroelastic Scaling of a Joined Wing for Nonlinear Geometric Stiffness. AIAA J. 2012, 50, 513–522. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wan, Z.; Cesnik, C.E.S. Geometrically Nonlinear Aeroelastic Scaling for Very Flexible Aircraft. AIAA J. 2014, 52, 2251–2260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pereira, P.; Almeida, L.; Suleman, A.; Bond, V.; Canfield, R.; Blair, M. Aeroelastic scaling and optimization of a joined wing aircraft concept. In Proceedings of the 48th AIAA/ASME/ASCE/AHS/ASC Structures, Structural Dynamics, and Materials Conference, Honolulu, HI, USA, 23–26 April 2007. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coelho, M.; Afonso, F.; Lau, F.; Suleman, A. Nonlinear aeroelastic scaling studies on high aspect ratio wings. In Proceedings of the 6th EASN International Conference on Innovation in European Aeronautics Research, Porto, Portugal, 18–21 October 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Yusuf, S.Y.; Hayes, D.; Pontillo, A.; Carrizales, M.A.; Dussart, G.X.; Lone, M.M. Aeroelastic Scaling for Flexible High Aspect Ratio Wings. In Proceedings of the AIAA Scitech 2019 Forum, San Diego, CA, USA, 7–11 January 2019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- French, M. An application of structural optimization in wind tunnel model design. In Proceedings of the 31st Structures, Structural Dynamics and Materials Conference, Long Beach, CA, USA, 2–4 April 1990. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- French, M.; Eastep, F.E. Aeroelastic model design using parameter identification. J. Aircr. 1996, 33, 198–202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ricciardi, A.P.; Eger, C.A.G.; Canfield, R.A.; Patil, M.J. Nonlinear Aeroelastic-Scaled-Model Optimization Using Equivalent Static Loads. J. Aircr. 2014, 51, 1842–1851. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ricciardi, A.P.; Canfield, R.A.; Patil, M.J.; Lindsley, N. Nonlinear Aeroelastic Scaled-Model Design. J. Aircr. 2016, 53, 20–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spada, C.; Afonso, F.; Lau, F.; Suleman, A. Nonlinear aeroelastic scaling of high aspect-ratio wings. Aerosp. Sci. Technol. 2017, 63, 363–371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Banazadeh, A.; Hajipouzadeh, P. Using approximate similitude to design dynamic similar models. Aerosp. Sci. Technol. 2019, 94, 105375. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buckingham, E. On Physically Similar Systems; Illustrations of the Use of Dimensional Equations. Phys. Rev. 1914, 4, 345–376. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ouellette, J.; Patil, M.; Kapania, R. Scaling Laws for Flight Control Development and Testing in the Presence of Aeroservoelastic Interactions. In Proceedings of the AIAA Atmospheric Flight Mechanics Conference, Minneapolis, MN, USA, 13–16 August 2012. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pittit, C.L.; Canfield, R.A.; Ghanem, R.L. Stochastic analysis of a aeroelastic system. In Proceedings of the 15th ASCE Engineering Mechanics Conference, New York, NY, USA, 2–5 June 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Bisplinghoff, R.L.; Ashley, H.; Halfman, R.L. Aeroelasticity; Dover Publications: Mineola, NY, USA, 1996. [Google Scholar]

- Suleman, A.; Afonso, F.; Vale, J.; Oliveira, E.; Lau, F. Non-linear aeroelastic analysis in the time domain of high-aspect-ratio wings: Effect of chord and taper-ratio variation. Aeronaut. J. 2017, 121, 21–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Afonso, F.; Leal, G.; Vale, J.; Oliveira, E.; Lau, F.; Suleman, A. The effect of stiffness and geometric parameters on the nonlinear aeroelastic performance of high aspect ratio wings. Proc. Inst. Mech. Eng. Part G J. Aerosp. Eng. 2017, 231, 1824–1850. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Howcroft, C.; Neild, S.; Lowenberg, M.; Cooper, J. Efficient aeroelastic beam modelling and the selection of a structural shape basis. Int. J. Non-Linear Mech. 2019, 112, 73–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rajpal, D.; Gillebaart, E.; De Breuker, R. Preliminary aeroelastic design of composite wings subjected to critical gust loads. Aerosp. Sci. Technol. 2019, 85, 96–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Afonso, F.; Vale, J.; Lau, F.; Suleman, A. Performance based multidisciplinary design optimization of morphing aircraft. Aerosp. Sci. Technol. 2017, 67, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Gaspari, A.; Ricci, S.; Antunes, A.; Odaguil, F.; Lima, G. Chapter 6-Expected Performances. In Morphing Wing Technologies; Concilio, A., Dimino, I., Lecce, L., Pecora, R., Eds.; Butterworth-Heinemann: Oxford, UK, 2018; pp. 175–203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ngo, T.D.; Kashani, A.; Imbalzano, G.; Nguyen, K.T.; Hui, D. Additive manufacturing (3D printing): A review of materials, methods, applications and challenges. Compos. Part B Eng. 2018, 143, 172–196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, W.; Zhang, X.; Li, D. Flexible all-plastic aircraft models built by additive manufacturing for transonic wind tunnel tests. Aerosp. Sci. Technol. 2019, 84, 237–244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Parameter | Set 1 | Set 2 | Set 3 |

|---|---|---|---|

| Length, | |||

| Time, | |||

| Frequency, | |||

| Mass, | |||

| Density, | |||

| Velocity, | |||

| Pressure, | |||

| Force, | |||

| Moment, | |||

| Inertia, |

| Characteristic | Value |

|---|---|

| Area (m) | 110 |

| Aspect-ratio (-) | 16 |

| Span (m) | 41.95 |

| Mean Aerodynamic Chord (m) | 2.62 |

| Root Chord (m) | 4.95 |

| Inboard Wing Half Semi-span (m) | 8.24 |

| Break Chord (m) | 2.61 |

| Outboard Wing Half Semi-span (m) | 12.73 |

| Tip Chord (m) | 1.13 |

| Dihedral Angle (deg) | 4.4 |

| Leading Edge Sweep Angle (deg) | 27.5 |

| Cruise | Hold | Alternate | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Mach (-) | 0.78 | 0.5 | 0.3 |

| Altitude (m) | 11582 | 5486 | 610 |

| Air density (kg/m) | 0.332 | 0.698 | 1.155 |

| Velocity (m/s) | 230 | 159 | 101 |

| Trim lift coefficient (-) | 0.588 | 0.584 | 0.872 |

| Trim angle of attack (deg) | 5.36 | 5.33 | 7.95 |

| Parameter | Set 1 | Set 2 | Set 3 |

|---|---|---|---|

| Length, | 0.1 | 0.1 | 0.1 |

| Time, | 0.4603 | 0.4541 | 0.1 |

| Frequency, | 2.1725 | 2.2023 | 10 |

| Mass, | 0.0037 | 3.7407 × 10 | 0.001 |

| Density, | 1 | 0.3741 | 1 |

| Velocity, | 0.2172 | 0.2202 | 0.3162 |

| Pressure, | 0.1741 | 0.0181 | 1 |

| Force, | 0.0017 | 1.8143 × 10 | 0.01 |

| Moment, | 0.0002 | 1.8143 × 10 | 0.001 |

| Inertia, | 3.6899 × 10 | 3.7407 × 10 | 1.0 × 10 |

| Parameter | Full-Size | Set 1 | Set 2 | Set 3 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Wing semi-span (m) | 20.975 | 2.0975 | 2.0975 | 2.975 |

| Mean aerodynamic chord (m) | 2.62 | 0.262 | 0.262 | 0.262 |

| Wing area (m) | 110 | 1.1 | 1.1 | 1.1 |

| Air density (kg/m) | 0.332 | 1.225 | 0.124 | 0.332 |

| Air speed (m/s) | 230 | 50 | 51 | 230 |

| Mach number (-) | 0.78 | 0.15 | 0.17 | 0.78 |

| Reynolds number (-) | 13,987,903 | 1,121,297 | 115,235 | 1,398,790 |

| Trim lift coefficient (-) | 0.588 | 0.588 | 0.588 | 0.588 |

| Trim angle of attack (deg) | 5.36 | 5.36 | 5.36 | 5.36 |

| Mass (kg) | 1874 | 6.915 | 0.701 | 1.874 |

| I (kg.m) | 183,312 | 6.764 | 0.686 | 1.833 |

| I (kg.m) | 59,838 | 2.208 | 0.224 | 0.598 |

| I (kg.m) | 240,147 | 8.861 | 0.898 | 2.401 |

| I (kg.m) | −100,368 | −3.704 | −0.375 | −1.004 |

| I (kg.m) | 8915 | 0.329 | 0.033 | 0.089 |

| I (kg.m) | −16,459 | −0.607 | −0.062 | −0.165 |

| Froude number (-) | 11.4 | 20.3 | 7.9 | 35.9 |

| Parameter | Full Size | Target | Scaled | Difference (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| @ cruise (-) | 0.779 | 0.779 | 0.614 | 21.2 |

| @ cruise (-) | 0.067 | 0.067 | 0.011 | 83.7 |

| @ cruise (-) | 1.305 | 1.305 | 0.954 | 26.9 |

| @ alternate (-) | 0.697 | 0.697 | 0.607 | 12.9 |

| @ alternate (-) | 0.014 | 0.014 | 0.011 | 24.2 |

| @ alternate (-) | 1.082 | 1.082 | 0.943 | 12.9 |

| @ hold (-) | 0.871 | 0.871 | 0.833 | 4.4 |

| @ hold (-) | 0.021 | 0.021 | 0.018 | 11.3 |

| @ hold (-) | 1.381 | 1.381 | 1.321 | 4.4 |

| 1st Flap (Hz) | 1.263 | 2.745 | 3.845 | 40.2 |

| 2nd Flap (Hz) | 5.155 | 11.198 | 11.321 | 1.1 |

| 1st Chord (Hz) | 5.228 | 11.357 | 11.635 | 2.5 |

| 3rd Flap (Hz) | 11.677 | 25.368 | 23.100 | 8.9 |

| 2nd Chord (Hz) | 20.904 | 45.414 | 24.030 | 47.1 |

| 4th Flap (Hz) | 21.211 | 46.080 | 36.705 | 20.4 |

| 1st Torsion (Hz) | 27.660 | 60.090 | 41.495 | 30.9 |

| 5th Flap (Hz) | 34.253 | 74.412 | 45.931 | 38.3 |

| 3rd Chord (Hz) | 47.553 | 103.308 | 65.918 | 36.2 |

| 6th Flap (Hz) | 50.178 | 109.009 | 70.851 | 35.0 |

| Mass (kg) | 1874 | 6.915 | 7.281 | 5.3 |

| I (kg.m) | 183,312 | 6.764 | 6.015 | 11.1 |

| I (kg.m) | 59,838 | 2.208 | 2.008 | 9.1 |

| I (kg.m) | 240,147 | 8.861 | 7.926 | 10.6 |

| I (kg.m) | −100,368 | −3.704 | −3.300 | 10.9 |

| I (kg.m) | 8915 | 0.329 | 0.288 | 12.4 |

| I (kg.m) | −16,459 | −0.607 | −0.536 | 11.8 |

| Parameter | Full size | Target | Scaled | Difference (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| @ cruise (-) | 0.779 | 0.779 | 0.628 | 19.5 |

| @ cruise (-) | 0.067 | 0.067 | 0.014 | 79.1 |

| @ cruise (-) | 1.305 | 1.305 | 0.974 | 25.4 |

| @ alternate (-) | 0.697 | 0.697 | 0.614 | 11.9 |

| @ alternate (-) | 0.014 | 0.014 | 0.013 | 9.5 |

| @ alternate (-) | 1.082 | 1.082 | 0.953 | 12.0 |

| @ hold (-) | 0.871 | 0.871 | 0.836 | 4.0 |

| @ hold (-) | 0.021 | 0.021 | 0.019 | 5.7 |

| @ hold (-) | 1.381 | 1.381 | 1.326 | 4.0 |

| 1st Flap (Hz) | 1.263 | 2.784 | 2.781 | 0.1 |

| 2nd Flap (Hz) | 5.155 | 11.295 | 11.350 | 0.5 |

| 1st Chord (Hz) | 5.228 | 11.490 | 11.503 | 0.1 |

| 3rd Flap (Hz) | 11.677 | 25.621 | 25.710 | 0.4 |

| 2nd Chord (Hz) | 20.904 | 45.788 | 45.988 | 0.4 |

| 4th Flap (Hz) | 21.211 | 46.630 | 46.648 | 0.0 |

| 1st Torsion (Hz) | 27.660 | 60.921 | 47.821 | 21.5 |

| 5th Flap (Hz) | 34.253 | 75.151 | 75.429 | 0.4 |

| 3rd Chord (Hz) | 47.553 | 104.341 | 105.147 | 0.8 |

| 6th Flap (Hz) | 50.178 | 110.321 | 110.619 | 0.3 |

| Mass (kg) | 1874 | 0.701 | 0.702 | 0.2 |

| I (kg.m) | 183,312 | 0.686 | 0.687 | 0.1 |

| I (kg.m) | 59,838 | 0.224 | 0.224 | 0.1 |

| I (kg.m) | 240,147 | 0.898 | 0.899 | 0.1 |

| I (kg.m) | −100,368 | −0.375 | −0.376 | 0.1 |

| I (kg.m) | 8915 | 0.033 | 0.033 | 0.1 |

| I (kg.m) | −16,459 | −0.062 | −0.062 | 0.2 |

| Parameter | Full Size | Target | Scaled | Difference (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| @ cruise (-) | 0.779 | 0.779 | 0.779 | 0.0 |

| @ cruise (-) | 0.067 | 0.067 | 0.066 | 2.1 |

| @ cruise (-) | 1.305 | 1.305 | 1.305 | 0.4 |

| @ alternate (-) | 0.697 | 0.697 | 0.699 | 0.2 |

| @ alternate (-) | 0.014 | 0.014 | 0.013 | 6.1 |

| @ alternate (-) | 1.082 | 1.082 | 1.085 | 0.2 |

| @ hold (-) | 0.871 | 0.871 | 0.872 | 0.1 |

| @ hold (-) | 0.021 | 0.021 | 0.020 | 5.3 |

| @ hold (-) | 1.381 | 1.381 | 1.382 | 0.1 |

| 1st Flap (Hz) | 1.263 | 12.642 | 12.642 | 0.0 |

| 2nd Flap (Hz) | 5.155 | 51.285 | 51.285 | 0.0 |

| 1st Chord (Hz) | 5.228 | 52.174 | 52.174 | 0.0 |

| 3rd Flap (Hz) | 11.677 | 116.340 | 116.340 | 0.0 |

| 2nd Chord (Hz) | 20.904 | 207.912 | 207.912 | 0.0 |

| 4th Flap (Hz) | 21.211 | 211.734 | 211.734 | 0.0 |

| 1st Torsion (Hz) | 27.660 | 276.627 | 276.662 | 0.0 |

| 5th Flap (Hz) | 34.253 | 341.240 | 341.240 | 0.0 |

| 3rd Chord (Hz) | 47.553 | 473.783 | 473.786 | 0.0 |

| 6th Flap (Hz) | 50.178 | 500.939 | 500.942 | 0.0 |

| Mass (kg) | 1874 | 1.874 | 1.874 | 0.0 |

| I (kg.m) | 183,312 | 1.833 | 1.833 | 0.0 |

| I (kg.m) | 59,838 | 0.598 | 0.598 | 0.0 |

| I (kg.m) | 240,147 | 2.401 | 2.401 | 0.0 |

| I (kg.m) | −100,368 | −1.004 | −1.004 | 0.0 |

| I (kg.m) | 8915 | 0.089 | 0.089 | 0.0 |

| I (kg.m) | −16,459 | −0.165 | −0.165 | 0.0 |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2020 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Afonso, F.; Coelho, M.; Vale, J.; Lau, F.; Suleman, A. On the Design of Aeroelastically Scaled Models of High Aspect-Ratio Wings. Aerospace 2020, 7, 166. https://doi.org/10.3390/aerospace7110166

Afonso F, Coelho M, Vale J, Lau F, Suleman A. On the Design of Aeroelastically Scaled Models of High Aspect-Ratio Wings. Aerospace. 2020; 7(11):166. https://doi.org/10.3390/aerospace7110166

Chicago/Turabian StyleAfonso, Frederico, Mónica Coelho, José Vale, Fernando Lau, and Afzal Suleman. 2020. "On the Design of Aeroelastically Scaled Models of High Aspect-Ratio Wings" Aerospace 7, no. 11: 166. https://doi.org/10.3390/aerospace7110166

APA StyleAfonso, F., Coelho, M., Vale, J., Lau, F., & Suleman, A. (2020). On the Design of Aeroelastically Scaled Models of High Aspect-Ratio Wings. Aerospace, 7(11), 166. https://doi.org/10.3390/aerospace7110166