1. Introduction

Energy plays a pivotal role in shaping technology, life, society, and sustainable development. Utilising energy more efficiently today has become one of the main targets for many countries to face a dwindling of non-renewable resources. Consequently, regular revisions are made to the approved energy policies by taking vehement measures to reduce waste energy. The transportation sector is considered an essential consumer of fossil fuel energy and faces unprecedented challenges today due to growth in fuel demand and pressure to minimise emissions. The World Energy Council (WEC) reported that fuel demand over the next four decades, between 2010 and 2050, will increase by 30–82% relative to 2010 levels [

1]. Air travel is expected to grow faster than any other transportation mode, contributing significantly to nitrogen oxide emissions from aircraft engines. As a result, even minor improvements in jet engine performance can lead to substantial fuel savings and cost reductions. Enhancing engine efficiency can be achieved by optimizing component performance, modifying configurations, or adjusting operating conditions. Gas turbine engines, particularly turbojet, turboprop, and turbofan designs, are widely used in aviation due to their lightweight, compact structure and high power-to-size ratio. Among these, turbofan engines dominate modern commercial aviation, combining a turbojet’s high thrust with a turboprop’s efficiency [

2]. Airlines prefer turbofan engines because of their high propulsive and thermal efficiencies at moderate speeds, the absence of a propeller, and complex reduction gearing. Additionally, turbofan engines are known for their reliability, durability, adaptability, and ease of maintenance. However, designing propulsion systems for turbofan engines remains a complex challenge due to their intricate, multidimensional nature. Advancements in propulsion technology can significantly enhance efficiency, reducing fuel consumption and minimizing environmental impacts, particularly CO

2 emissions [

3]. Numerous studies and theoretical analyses support the claim that turbofan engines are among the most fuel-efficient propulsion systems ever developed. Given their widespread use in commercial aviation, even slight performance improvements can lead to significant energy savings and reduced environmental impact. Mohd Tobi and Ismail present a study on geared turbofan aero-engines, emphasizing their potential for enhanced fuel efficiency, reduced pollutant emissions, and lower noise levels. However, the study raises concerns about the reliability performance of these engines, which remains an area of uncertainty [

4]. Liu and Sirignano conducted an extensive thermodynamic analysis to compare traditional engines’ performance with turbine-burner engines’ performance. Their study explored various combustion strategies for both turbojet and turbofan configurations. The findings indicated that turbine-burner engines exhibit increasingly significant performance improvements as compressor pressure ratio, fan bypass ratio, and flight Mach number increase [

5]. Huff’s review of NASA-funded research on turbofan engine noise mitigation emphasizes that substantial noise reduction can be attained through modifications to the engine cycle. These enhancements primarily involve decreasing fan tip speed, lowering the fan pressure ratio, and reducing jet exhaust velocity [

6]. Svoboda, compiled a comprehensive database of modern turbofan engines, encompassing critical parameters like fan geometry and specific fuel consumption (at cruise and takeoff). These parameters are presented as functions of takeoff thrust, making this database a valuable resource for preliminary engine design [

7]. Homaifar et al. employed genetic algorithms (GA) to optimize complex turbofan engine performance, utilizing metrics such as thrust per unit mass flow rate and overall efficiency. Their findings corroborated previous research outcomes and established GA as a valuable tool for future engine design endeavors [

8]. Kuropatwa et al. examined historical trends in aircraft engine fuel efficiency, identifying critical factors influencing performance and highlighting future technological requirements. Their study underscored the importance of increasing the bypass ratio—achieved by enlarging fan diameters and lowering rotation speeds—as a key strategy for reducing fuel consumption [

9]. Turan and Aydin conducted an exergy and sustainability assessment of the JT8D low-bypass turbofan engine using six specific indicators. Their findings revealed an exergy efficiency of just 11% and determined that exergy recovery within the engine is impractical due to inevitable emissions from both the fan bypass duct and core engine exhaust. Turan also performed energy and exergy analyses on an MD-80 aircraft during takeoff, finding an energy efficiency of 29.8% and an exergy efficiency of 11.48% [

10]. Turgut et al. exergy analysis of a kerosene-powered turbofan engine with an afterburner (AB) showed significantly higher exergy destruction rates at sea level compared to those at an altitude of 11,000 m [

11]. Kaya et al. conducted a parametric analysis on the exergetic sustainability of a hydrogen-fueled high-altitude, long-endurance UAV as an alternative to kerosene. Their study found that exergy efficiency improves with altitude, thrust, and speed but highlighted the need for revised definitions of useful work and exergy efficiency [

12]. Balli introduced a new set of exergy-based sustainability metrics to evaluate the environmental impact of the PW4056 turbofan engine on a Boeing 747. The study found that the engine demonstrates higher sustainability at maximum takeoff power mode than at the takeoff reference power mode [

13]. Tona et al. performed an exergy and thermoeconomic analysis of a turbofan engine throughout a standard commercial flight. Their study showed notable fluctuations in exergy efficiency across different flight phases, with a maximum of 26.5% during cruise. The combustion chamber and mixer were identified as the main contributors to exergy destruction, accounting for 50–66% of the total losses [

14]. Tona et al. introduced an innovative ecological optimization method for a turbofan engine, defining the “Coefficient of Ecological Performance” (CEP) as the ratio of propulsive power to exergy destruction rate. Their analysis, focused on a single-spool turbofan with unmixed exhaust and finite-rate heat transfer, found that increasing turbine inlet temperatures enhances ecological performance, while lower temperatures improve overall efficiency [

15]. Tai et al. explore the use of genetic algorithm (GA) metaheuristics to optimize the design of two-spool separated-flow turbofan engines, incorporating energy and exergy principles. The findings indicate that integrating both energy and exergy efficiencies provides an optimal trade-off between fuel consumption and specific thrust, making it applicable to both military and commercial uses [

16]. Indriyati et al. perform an advanced exergy analysis on turbofan engines, identifying the combustion chamber as the primary source of exergy loss due to irreversibility caused by chemical reactions and heat transfer [

17]. Kalkan utilizes GasTurb 14 to create a model of the CFM56-5A3 turbofan engine and conducts an exergy analysis to assess its efficiency and performance. The results show a 14.0% and a 7.2% discrepancy in thrust and SFC between the modeled and actual engine, with maximum thrust and SFC occurring at the minimum bypass ratio [

18]. Recently, several researchers have analyzed turbofan engines using various approaches and computational techniques. Studies such as those by Korba et al. [

19], Aygun and Turan [

20], Nourianpou and Banitalebidehkordi [

21] and AlHarbi et al. [

22] demonstrate significant progress in enhancing the reliability and performance of turbofan engines for the aviation and aerospace industries.

5. Results and Discussion

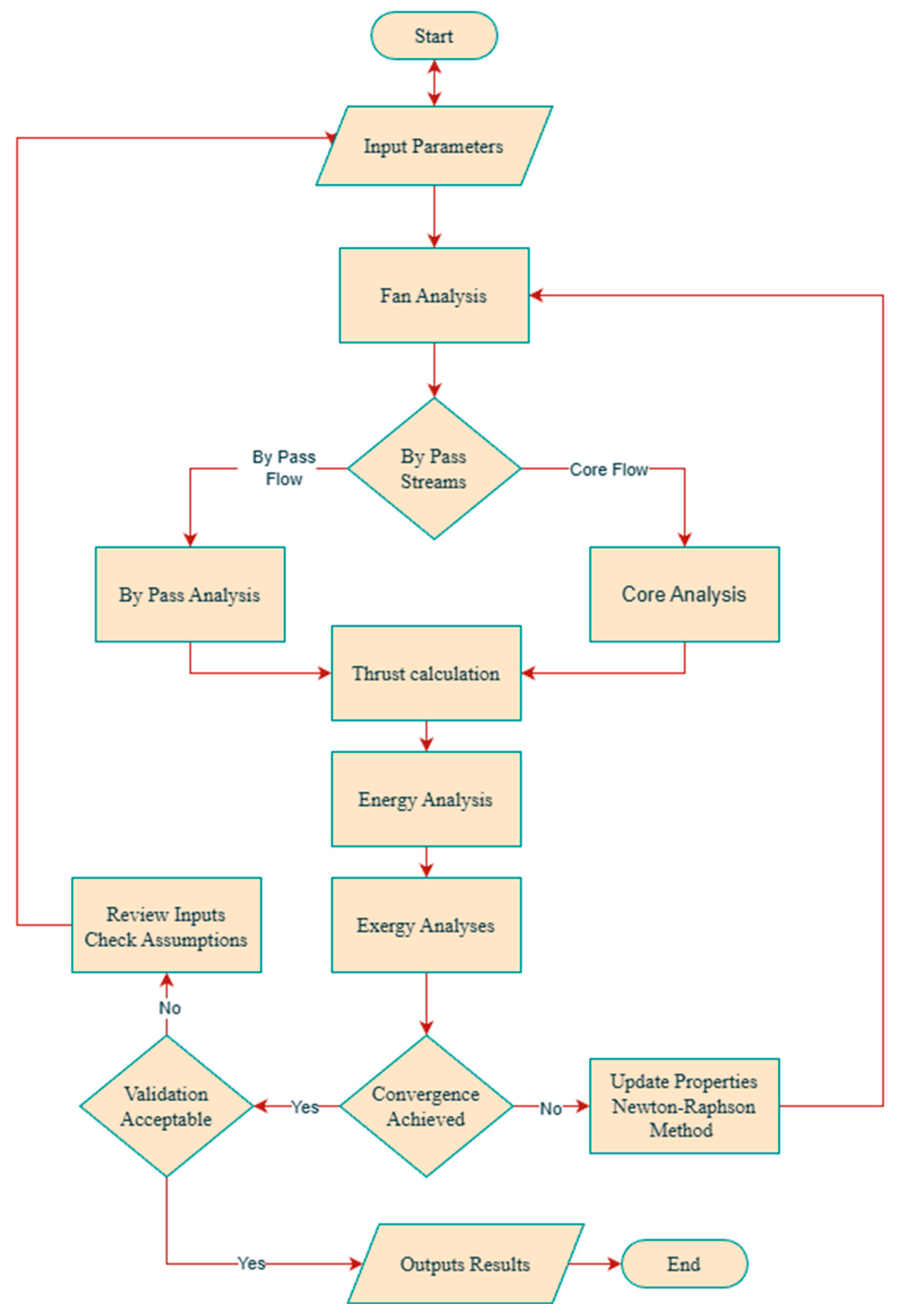

In this section, we present a detailed examination of the outcomes from our turbofan engine models. To better guarantee reliability and precision, our results were carefully compared with engine manufacturers’ published data and previous research results. We developed five individual models representing different types of turbofan engines. For consistency all engine performance assessments were conducted under standardized operational conditions. The takeoff condition corresponded to an ambient pressure of 101.3 kPa, an ambient temperature of 15 °C, and a relative humidity of 30%. The cruise condition was defined as Mach 0.8 at a flight altitude of 10,000 m, representing typical steady-state operating conditions for commercial turbofan engines.

A key element in our approach was the validation of our models by comparing their performance with published manufacturers’ data. This comparison revealed strong agreement between predicted and actual engine behaviors, confirming the accuracy of our models and their reliability, ensuring that subsequent performance evaluations are robust and credible.

Table 3 presents the GE-90 turbofan engine as a representative example, comparing the actual performance data provided by [

28,

37] with the results generated in this study under the same operational conditions. In

Appendix A, detailed validation results are presented for the remaining four turbofan engine configurations modeled in this study, evaluated at sea-level static takeoff conditions under International Standard Atmosphere (ISA) conditions All models were validated against manufacturer-provided specifications and published performance data.

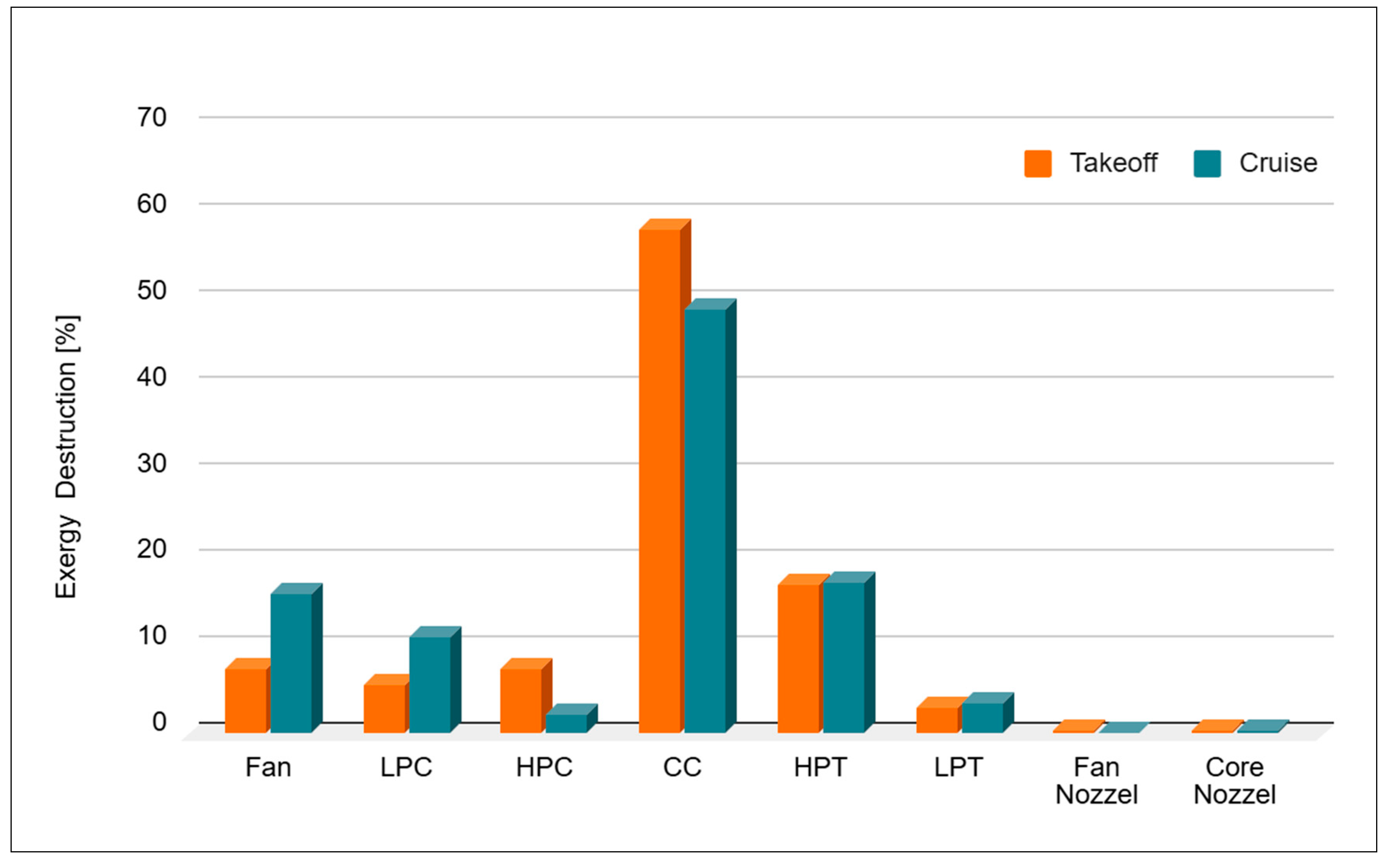

Figure 3 illustrates the distribution of exergy destruction across the main components of the turbofan engine, expressed as a percentage of the total exergy destruction rate, under takeoff and cruise conditions for Case-1. The results clearly demonstrate that the combustion chamber (CC) accounts for the largest share of exergy destruction of all components, approximately 59% during takeoff and 49% during cruise. This confirms that the combustion process remains the primary source of irreversibility in the engine cycle. The predominant exergy destruction within the combustor arises from the intrinsic irreversibilities of the combustion process. These include entropy generation due to finite-rate chemical kinetics and imperfect mixing of fuel and oxidizer streams, as well as the large thermal irreversibility associated with the steep temperature gradient across the flame front during exothermic heat release.

During takeoff, the elevated fuel flow rate and higher thermal loading intensify exergy destruction in the combustion chamber, leading to greater irreversibility than in cruise operation. Under takeoff conditions, the fuel-air ratio is significantly increased to satisfy the elevated thrust requirement. This leads to localized near-stoichiometric combustion zones where flame temperatures exceed 2000 K. The combination of these higher peak temperatures and substantially increased combustor mass flow rates intensifies viscous dissipation within the recirculation zones and markedly accentuates exergy destruction associated with irreversible heat transfer across the combustor liner walls.

Significant exergy destruction is also observed in the fan and the high-pressure turbine (HPT), accounting for about 8% and 17%, respectively. These losses can be attributed to aerodynamic inefficiencies, mechanical friction, and deviations from isentropic expansion and compression. In the fan, exergy destruction primarily occurs due to tip leakage vortices, secondary flows in the blade passages, and boundary layer losses on the blade surfaces, particularly at the high rotational speeds required during takeoff. The HPT exhibits substantial entropy production arising from multiple sources: the irreversible mixing of blade cooling air with the primary mainstream gas path flow, radial inefficiencies in work extraction due to non-uniform inlet temperature distributions, and aerodynamic losses including profile, secondary, and tip leakage effects.

Under cruise conditions, exergy destruction becomes more evenly distributed across the engine components. The fan (16.2%), HPT (17.4%), and low-pressure compressor LPC (11.4%) demonstrate greater relative contributions, reflecting the steady-state operational mode characterized by reduced fuel consumption and lower thermal gradients in the combustion chamber resulting in less relative exergy destruction. During cruise, the fan and compressors operate at lower speeds and away from their optimal design points, which increases flow separation and boundary layer losses, making these components relatively more important for total losses. The high-pressure compressor (HPC) and nozzle components show minimal exergy destruction (<5%), indicating relatively minor thermodynamic losses in these stages. The HPC operates with high isentropic efficiency close to its design point, benefiting from tight tip clearances that minimize leakage losses across the blade tips. The stator vanes and rotor blades are optimally designed to ensure smooth, shock-free flow acceleration and diffusion, effectively preventing boundary-layer separation and associated irreversibilities. Overall, the combustion chamber remains the dominant contributor to total exergy destruction, emphasizing its critical role in defining the engine’s overall irreversibility. Improvements in combustor design, including better fuel-air mixing and optimized film-cooling hole geometries, can substantially reduce peak flame temperatures and decrease exergy destruction arising from irreversible thermal and velocity mixing between cooling air and the mainstream flow, thereby significantly mitigating overall combustor losses. However, aerodynamic refinements in the fan and turbine stages would improve overall exergetic performance, particularly during cruise conditions.

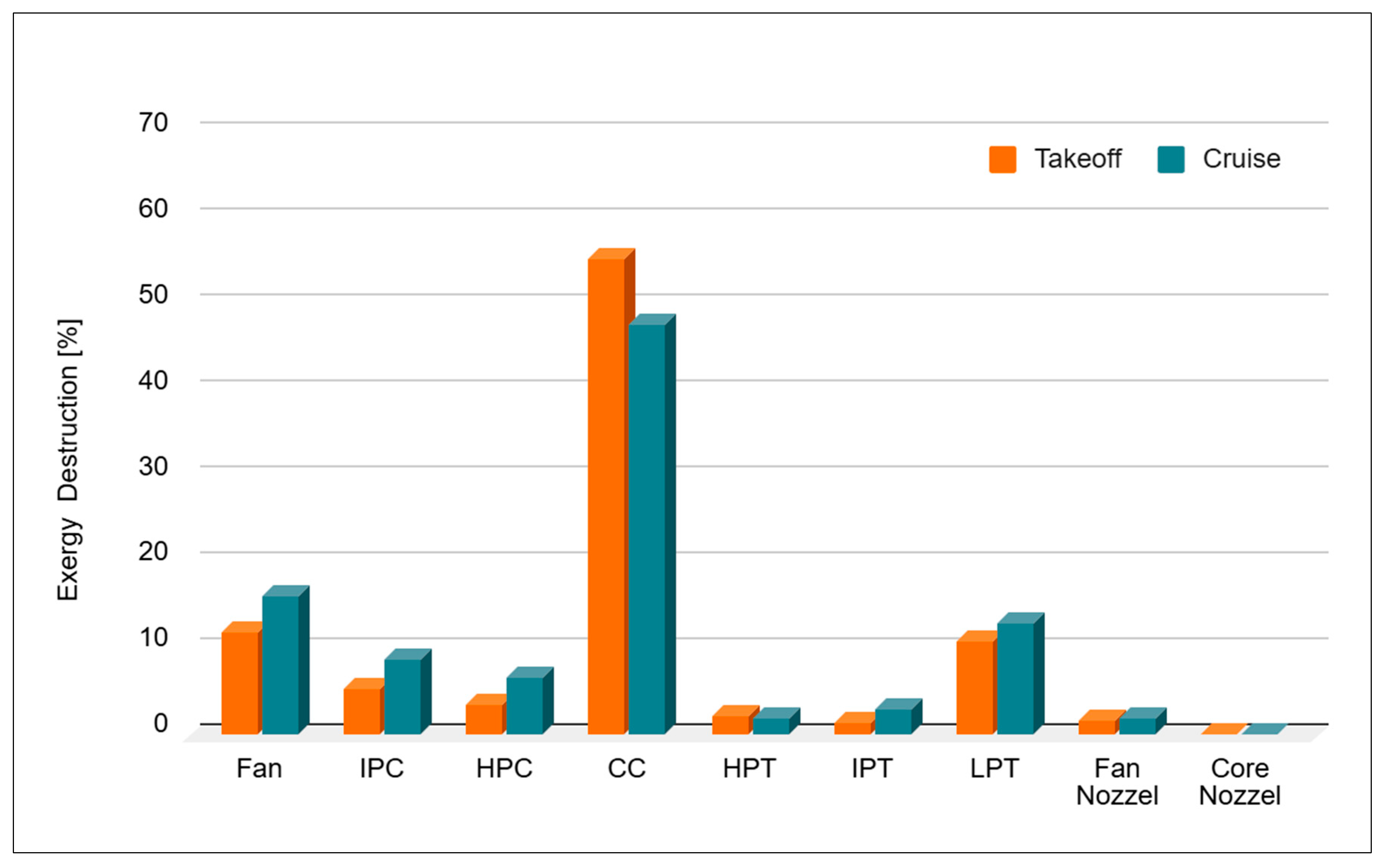

Figure 4 presents the exergy destruction distribution, expressed as a percentage of total exergy destruction, for a triple-spool engine configuration under takeoff and cruise conditions (Case-4). The combustion chamber (CC) is, again, the primary source of exergy destruction. A notable decrease of approximately 8% in the CC’s contribution to overall exergy destruction is observed from takeoff to cruise. In contrast, the fan’s contribution to total exergy destruction rises by about 5%. Compared to the dual-spool turbofan engine (

Figure 3), these variations are less pronounced, indicating improved load distribution and enhanced thermodynamic efficiency in the triple-spool configuration. The figure demonstrates that the low-pressure turbine (LPT) in the three-spool engine exhibits notably higher exergy destruction—approximately 11% at takeoff and 13% at cruise compared with 3.5% and 4.5%, respectively, in the two-spool case. This difference originates directly from the engine architecture and the resulting turbine work split. In a three-spool configuration, the LPT drives the fan alone via an independent shaft, requiring a substantially higher specific work output. This increases stage loading and pressure ratio across the LPT, which intensifies aerodynamic losses and entropy generation. The elevated stage loading in the low-pressure turbine (LPT) requires each stage to extract a greater amount of work, which imposes stronger adverse pressure gradients on the blade surfaces. These steep gradients promote boundary-layer separation, especially on the suction side near the hub and tip regions, and significantly intensify secondary flow losses driven by passage vortices and corner separations. Furthermore, the higher flow-turning angles necessary for increased work extraction strengthen tip-leakage flows across the blade-tip clearance gaps, generating powerful tip vortices that irreversibly mix with the main flow and thereby destroy a substantial portion of available work. Accordingly, the higher exergy destruction is a thermodynamically consistent consequence of the larger work extraction demanded from the LPT in the three-spool architecture. Conversely, two-spool engines use a single low-pressure shaft connecting the fan, LPC, and LPT, distributing work across more stages with lower specific work per stage, reduced pressure ratios, and fewer aerodynamic losses. In two-spool engines, the low-pressure turbine (LPT) typically incorporates fewer stages than in three-spool configurations. To meet power requirements, these stages are often designed with moderate specific work per stage, leading to lower flow velocities, reduced blade loading, and incidence angles that remain close to their optimal values. This design strategy minimizes profile losses, suppresses flow separation, and helps maintain attached flow over a wider operating range. This leads to lower exergy destruction despite broader mechanical responsibilities. The balance equations reveal that reduced fan speed in three-spool configurations forces a significant increase in LPT stage loading. To optimize engine mass and axial length, power extraction from the gas stream exiting the intermediate-pressure turbine (IPT) typically involves fewer stages, requiring higher aerodynamic work coefficients per stage to drive the substantially larger fan diameter while accommodating the rotational speed mismatch. The fan in Case-4 rotates at a much lower speed than the direct-drive two-spool fan (Case-1). To generate the same fan power at this reduced rotational speed, the low-pressure turbine must deliver significantly higher torque. This increases LPT stage loading, requiring more aggressive flow turning, which strengthens horseshoe vortices at the blade roots and tips and leads to elevated secondary-flow losses along the endwalls. Although the enthalpy differences due to fan size might partially offset this effect, the net result is elevated local entropy generation from increased secondary flows, shock losses, and tip clearance effects.

At cruise conditions, the flow exiting the low-pressure turbine (LPT) reaches high subsonic, near-sonic velocities. Under these conditions, localized regions of supersonic flow can develop on the blade surfaces and terminate in weak shock waves. These shocks increase aerodynamic losses by adding wave drag, thickening the boundary layers, and generating entropy in excess of conventional viscous losses. Consequently, the LPT contributes a substantially greater proportion to total exergy destruction compared to equivalent two-spool designs. This thermodynamic penalty underscores the trade-off between mechanical flexibility and aerodynamic efficiency in three-spool LPT systems. The exergy destruction analysis highlights a complex balance between the two- and three-spool engine configurations. Although both designs exhibit similar overall losses in the cold section, the distribution of exergy destruction within the hot section differs markedly. The three-spool arrangement demonstrates improved efficiency by reducing losses in the combustion chamber and HPT stages, indicating more effective energy utilization in these core components. In three-spool engines, splitting compression into low-, intermediate-, and high-pressure systems improves matching over the operating range and provides a more stable flow into the combustor. The independent high-pressure spool also allows the high-pressure turbine to run closer to its design point at different power settings, keeping flow angles near optimal and reducing off-design losses. This advantage, however, is offset by increased destruction in the LPT, which must supply the power needed to drive the large, slow-rotating fan characteristic of high-bypass-ratio engines. Overall, the three-spool design reflects a deliberate trade-off between reduced core losses and higher turbine work to support enhanced propulsive performance.

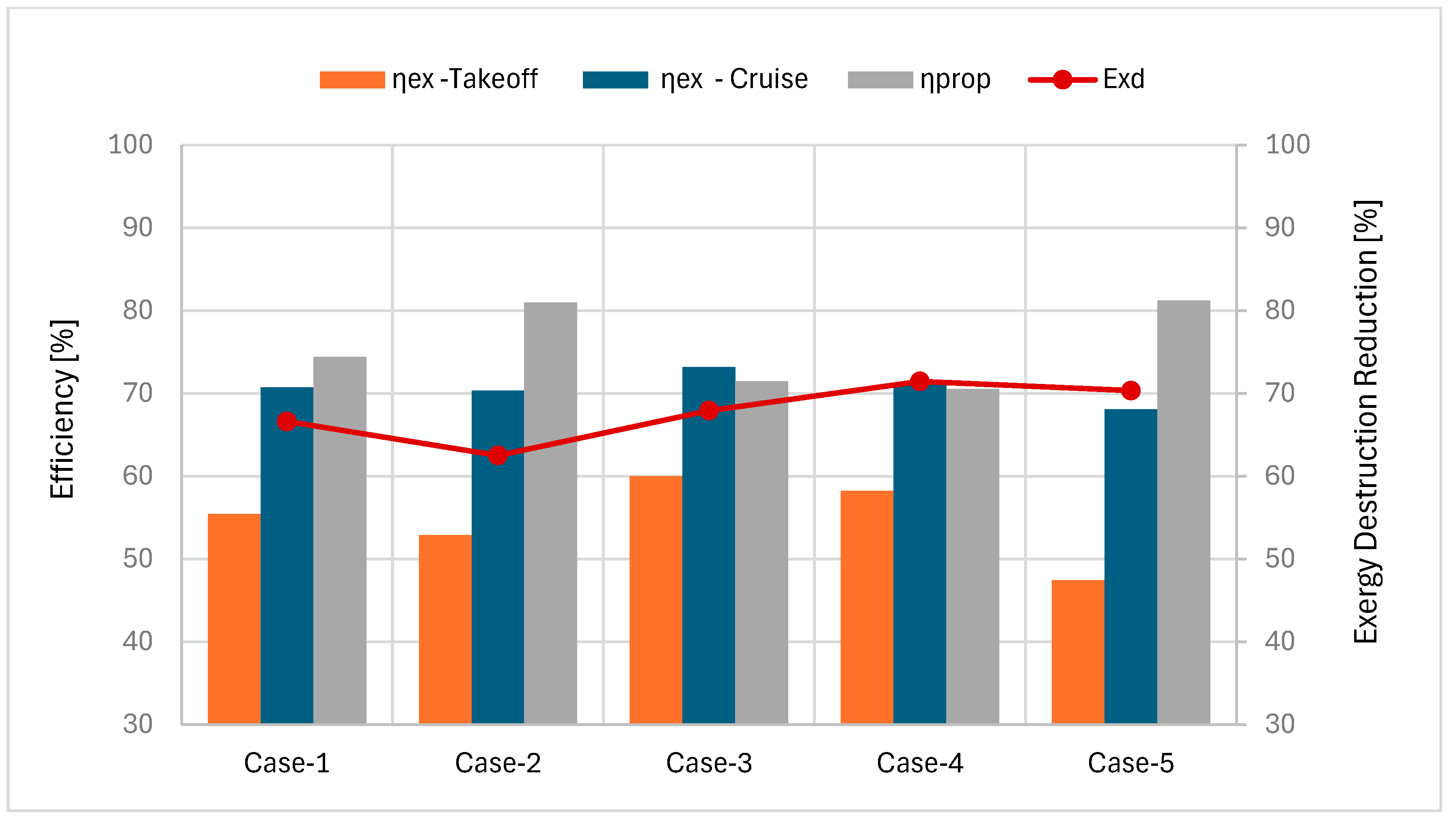

Figure 5 demonstrates a clear and consistent pattern in the exergetic efficiency between the two principal flight regimes evaluated in this investigation. The cruise operating condition exhibits a clearly superior exergetic performance, with efficiency values within the range 68–74% across all five test scenarios. The takeoff phase, characterized by high-thrust requirements, shows substantially lower efficiency metrics, between 47% and 60%. This noticeable difference in performance emphasizes the thermodynamic advantages of steady-state, lower-power cruise operations relative to the more demanding conditions met during takeoff, where enhanced power output and increased mass flow rates are essential for adequate thrust generation. During takeoff, high fuel flow and temperatures increase thermal irreversibility, while the fan and compressors operate near maximum speed, producing high tip Mach numbers. These conditions promote shock formation and increased tip leakage flow, leading to additional aerodynamic losses. The observed trend confirms that high-power operating regimes (takeoff) inherently generate greater irreversibilities within the propulsion system, thereby degrading overall exergetic performance relative to lower-power cruise flight conditions. At cruise, fuel flow and turbine temperatures are lower than at takeoff, reducing thermal irreversibility. Because cruise is a primary design condition, the blades operate with well-attached, stable flow, allowing the engine to run close to its peak efficiency.

A comparative analysis of engine configurations reveals that bypass ratio serves as the critical design parameter influencing exergetic performance across operating regimes. As illustrated in

Figure 5, Case-3’s high-bypass ratio (high-BPR), two-spool architecture achieves the highest takeoff exergetic efficiency at approximately 60%, reflecting optimal thermodynamic performance under high-thrust transient conditions. This behavior can be attributed to the favorable mass flow distribution in high-bypass configurations, where a larger proportion of core stream energy is transferred to the bypass stream with fewer irreversibilities. In high bypass ratio engines (BPR ≈ 11), roughly 90% of the air passes straight through the large fan and bypasses the hot core completely. This cool bypass air produces most of the thrust without ever going through the inefficient combustion process. Only about 10% of the air enters the core, where the majority of energy losses happen. By separating the airflow this way, the engine greatly reduces overall energy waste. Conversely, the moderate BPR design of Case-1 demonstrates competitive cruise performance, attaining an exergetic efficiency of approximately 70.7%. However, Case-1 exhibits superior takeoff performance with an exergetic efficiency of 55.4%, compared to Case-3’s 60.0%, suggesting that moderate bypass ratios balance core losses across different operating conditions, where varying specific thrust requirements allow for more efficient energy conversion within the thermodynamic cycle. Moderate BPR engines use a smaller fan that spins slower, reducing losses at the blade tips. However, they compensate by pushing more air through the hot engine core, which increases losses there instead. The reduction in exergy destruction from takeoff to cruise is noticeably greater in three-spool configurations. Specifically, Case-4 exhibits a reduction of 71.48%, while Case-5 achieves 70.34%. These results underline the enhanced thermodynamic efficiency and operational adaptability of the three-spool engine’s architecture across different flight conditions. Three-spool engines can adjust three independent shaft speeds, allowing each compressor and turbine section to run at their optimal speeds during cruise. As a result, the airflow hits every blade at the correct angle, keeping the flow smooth, attached, and with very low losses. Case-2, a two-spool configuration with a higher bypass ratio, demonstrates the least reduction in exergy destruction, 62.53% between takeoff and cruise. This indicates that, while an elevated bypass ratio improves propulsive efficiency, it may result in less efficient exergy utilization in other operating conditions relative to three-spool configurations. In two-spool engines, the fan and turbine must spin together at the same speed. At cruise, when less power is needed, the whole shaft slows down. This forces the fan to run far from its ideal design condition, so air hits the blades at poor angles, causing turbulence, flow separation, and extra energy waste. The three-spool design of Case-5, featuring a large-diameter fan, delivers superior propulsive efficiency (81%), aligning with its low TSFC values. This is driven by a high bypass ratio that lowers jet velocity, enhancing propulsive efficiency as per momentum theory. High-bypass-ratio engines generate thrust by accelerating a large mass of air to a low velocity, rather than a small mass of air to a high velocity. Because wasted kinetic energy in the exhaust grows with the square of velocity, moving more air more slowly dramatically reduces the energy left behind in the jet wake. This is the fundamental reason high-BPR engines achieve much higher efficiency. However, propulsive efficiency does not directly correspond to exergetic efficiency, as seen in Case-2, which achieves high propulsive efficiency (80%) but only moderate exergetic efficiency (70%) during cruise. This distinction underscores that propulsive efficiency evaluates only how effectively thrust is produced from the exhaust kinetic energy, whereas exergetic efficiency accounts for all energy degradation throughout the engine, including inefficient fuel combustion, frictional losses during air compression, irreversible mixing of hot and cold streams, and heat rejection through the casing walls. Consequently, an engine may exhibit high propulsive efficiency while still suffering substantial internal exergy destruction.

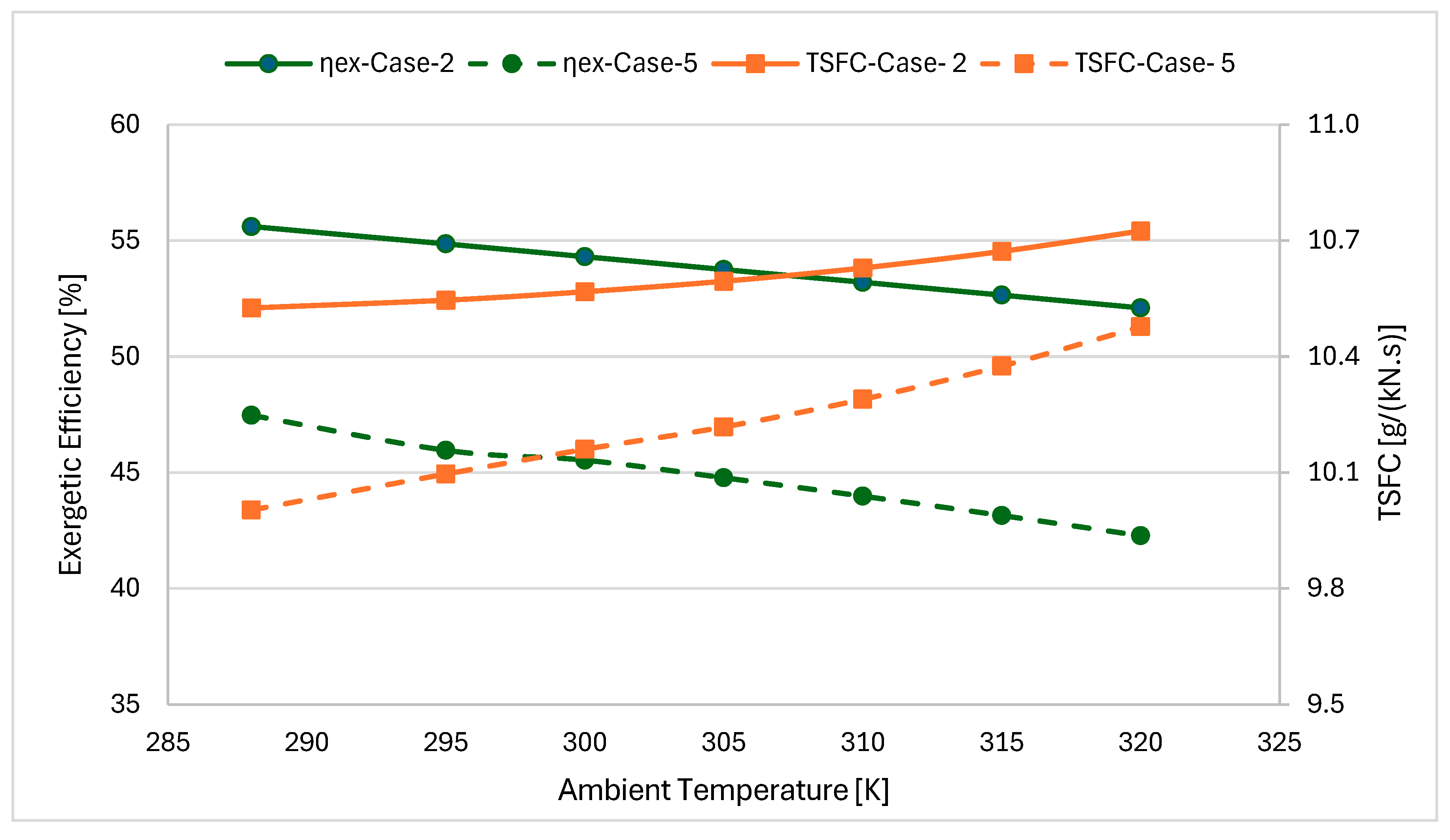

Figure 6 illustrates the influence of ambient conditions on exergetic efficiency and thrust-specific fuel consumption (TSFC) during takeoff for the Case-2 (two-spool) and Case-5 (three-spool) engine configurations, highlighting the impact of ambient temperature on engine performance. Ambient climatic conditions significantly affect turbofan engine performance, particularly relevant in regions like Kuwait, where temperatures range from −2 °C in winter to 55 °C in summer. Ambient temperature can be a key factor in assessing the influence of climatic variations on engine performance. For both engine configurations, as the ambient temperature rises from 288 K to 320 K, exergetic efficiency decreases nearly linearly, from 56.10% to 52.10% for Case-2, and from 47.47% to 42.28% for Case-5. Simultaneously, TSFC, a vital measure of fuel efficiency, increases from 10.52 g/(kN·s) to 10.74 g/(kN·s) for Case-2 and from 10.00 g/(kN·s) to 10.48 g/(kN·s) for Case-5. At higher ambient temperatures, lower air density reduces compressor mass flow, resulting in lower net thrust and higher TSFC. Hot air is less dense (roughly 10% lighter at 320 K than at 288 K), so the engine ingests less mass of air per second. With reduced mass flow, the compressor blades operate away from their design incidence angles, causing flow separation on the blade surfaces and generating turbulence. This separated, turbulent flow sharply lowers compressor efficiency and increases energy waste. This reduced mass flow exacerbates internal irreversibilities, necessitating greater work by the compressor to achieve the desired pressure ratio, thereby diminishing exergetic efficiency. To achieve the required pressure ratio with lower mass flow, the compressor must work harder. This forces the blades to operate at higher incidence angles, making the airflow fight against stronger adverse pressure gradients. As a result, boundary layers thicken and become highly turbulent, partially blocking the passage and generating intense swirling vortices that dissipate energy through friction and chaotic mixing. Moreover, maintaining a constant engine shaft speed in hot conditions means a reduced non-dimensional rotational speed (N/√Tₐ), thereby reducing temperature and pressure ratios. When the intake air is hotter, the same physical shaft speed (RPM) corresponds to a lower corrected speed for the compressor. As a result, the compressor produces a lower pressure ratio than on a cold day. To maintain the required thrust, the engine control system adds more fuel, which raises combustor and turbine temperatures further. The increased temperature difference between the very hot combustion gases and the (also warmer) cooling air leads to greater irreversibility when these streams mix, causing substantial additional exergy destruction inside the engine. This requires an increase in compressor power consumption and entropy production, further degrading overall engine performance. When the intake air is hot, the compressor demands significantly more power. First, the blades must deflect the thinner air at sharper angles to achieve the same pressure rise, which increases drag and friction losses. Second, compressing hot, low-density air inherently requires more work than compressing cool, dense air. Finally, in the rear stages where flow speeds approach sonic conditions, higher temperatures trigger small shock waves that thicken boundary layers and generate additional losses. As a result, the turbine must extract more energy from the hot gas, forcing the engine to burn extra fuel. From a fuel efficiency standpoint and for optimal performance in high-temperature climates, Case-5 (three-spool configuration) is the superior option due to its lower TSFC, higher thrust output, enhanced adaptability to diverse conditions, and operational benefits. The three-spool engine handles hot weather better because its three independent shafts can each adjust their speeds separately. The intermediate-pressure compressor can speed up slightly to compensate for the thin air, while the high-pressure compressor maintains optimal flow angles. This keeps airflow smooth and attached to blade surfaces across all compressor sections. Additionally, Case-5’s high bypass ratio means it does not need to work the core as hard—less fuel burning and lower temperatures—which reduces the heat-related losses that hurt performance on hot days. The reduced TSFC minimizes fuel use per unit of thrust, lowering operating costs and environmental impact, while its elevated thrust capacity supports larger aircraft or missions demanding robust performance in a hot environment.

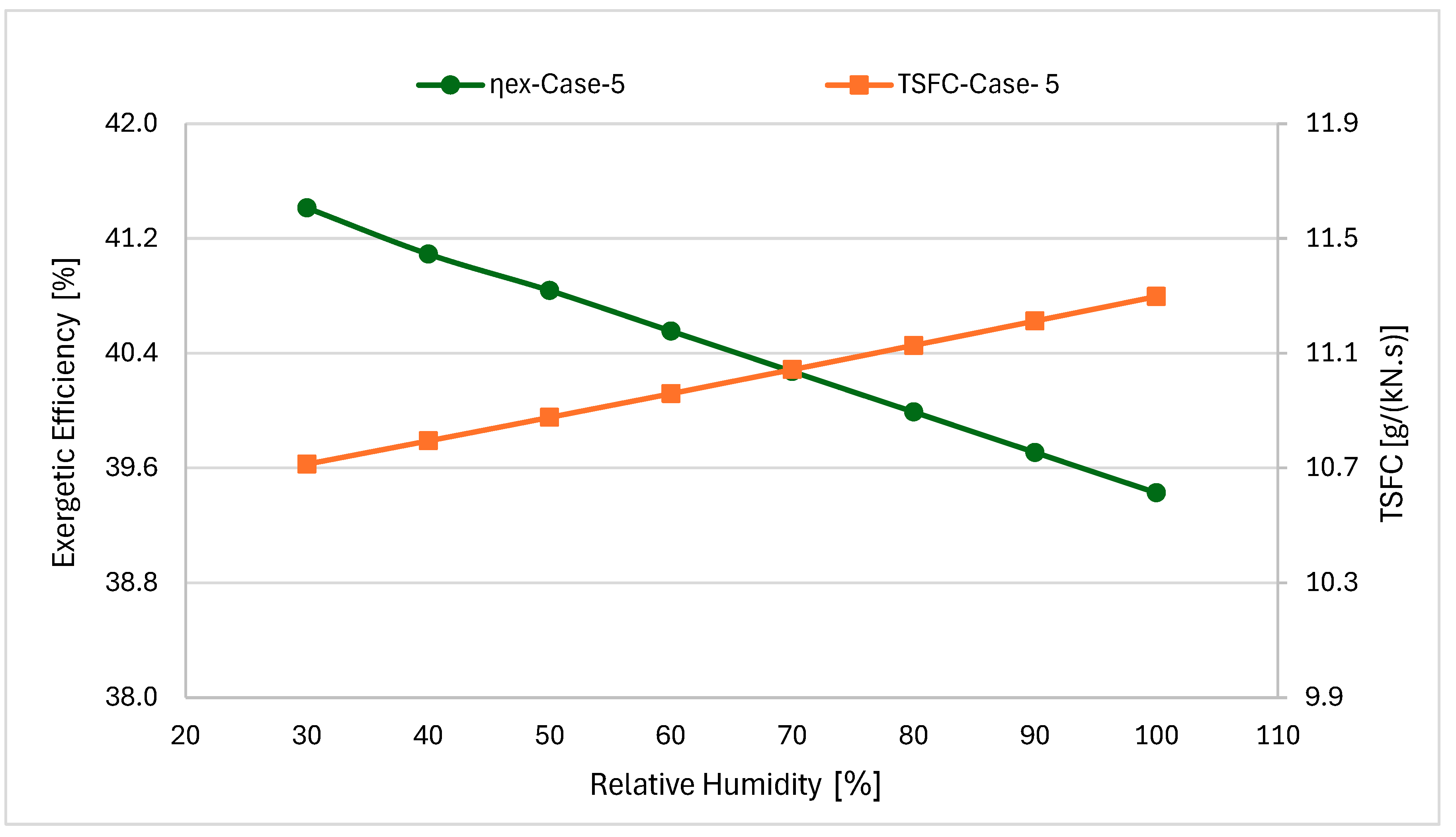

Figure 7 illustrates the effect of relative humidity on exergetic efficiency (ηex) and TSFC at T = 320 K, representing typical hot climatic conditions encountered in the Gulf region during summer operations. The study examines humidity variations from 30% to 100% to assess engine performance degradation under the challenging environmental conditions characteristic of Middle Eastern airports, where high temperatures combined with elevated moisture content, particularly during early morning and evening hours, significantly impact aircraft propulsion system efficiency. The results for Case-5 demonstrate an inverse relationship between the performance metrics as atmospheric moisture increases. Exergetic efficiency declines monotonically from 41.4% to 39.4%, while TSFC increases from 10.7 to 11.3 g/(kN·s). These changes are due to reduced air density (less oxygen/m

3), increase in specific heat capacity with humidity of the air, and enhanced thermodynamic irreversibilities in combustion and expansion processes. Humid air is less dense and contains water vapor that has high specific heat capacity but produces no thrust. The compressor therefore works harder yet achieves less pressure rise, the combustor must burn more fuel to reach the same temperature, and the turbine extracts less work from the wetter gas. Overall, humidity noticeably reduces thrust and increases specific fuel consumption. The near-linear trends indicate systematic performance degradation driven by fundamental thermodynamic property changes rather than discrete threshold effects. The steady, linear decline shows that each 10% increase in humidity adds more water vapor that progressively dilutes the oxygen and absorbs more heat energy. This continuous accumulation causes proportional losses throughout the engine. These findings are particularly relevant for Gulf region operations, where ambient conditions frequently combine temperatures of 320 K (47 °C) with relative humidity exceeding 70–80% during critical takeoff phases, resulting in significant reduction in the thrust margin and increased fuel consumption that must be accounted for in mission planning and aircraft performance calculations. On humid mornings (80–90% relative humidity), engines typically lose 8–10% of takeoff thrust compared to dry conditions. This reduction often forces pilots to reduce payload or extend the takeoff roll. Additionally, the 5.6% increase in TSFC during takeoff results in the engine consuming approximately 3–5 kg more fuel per takeoff phase than in dry air.

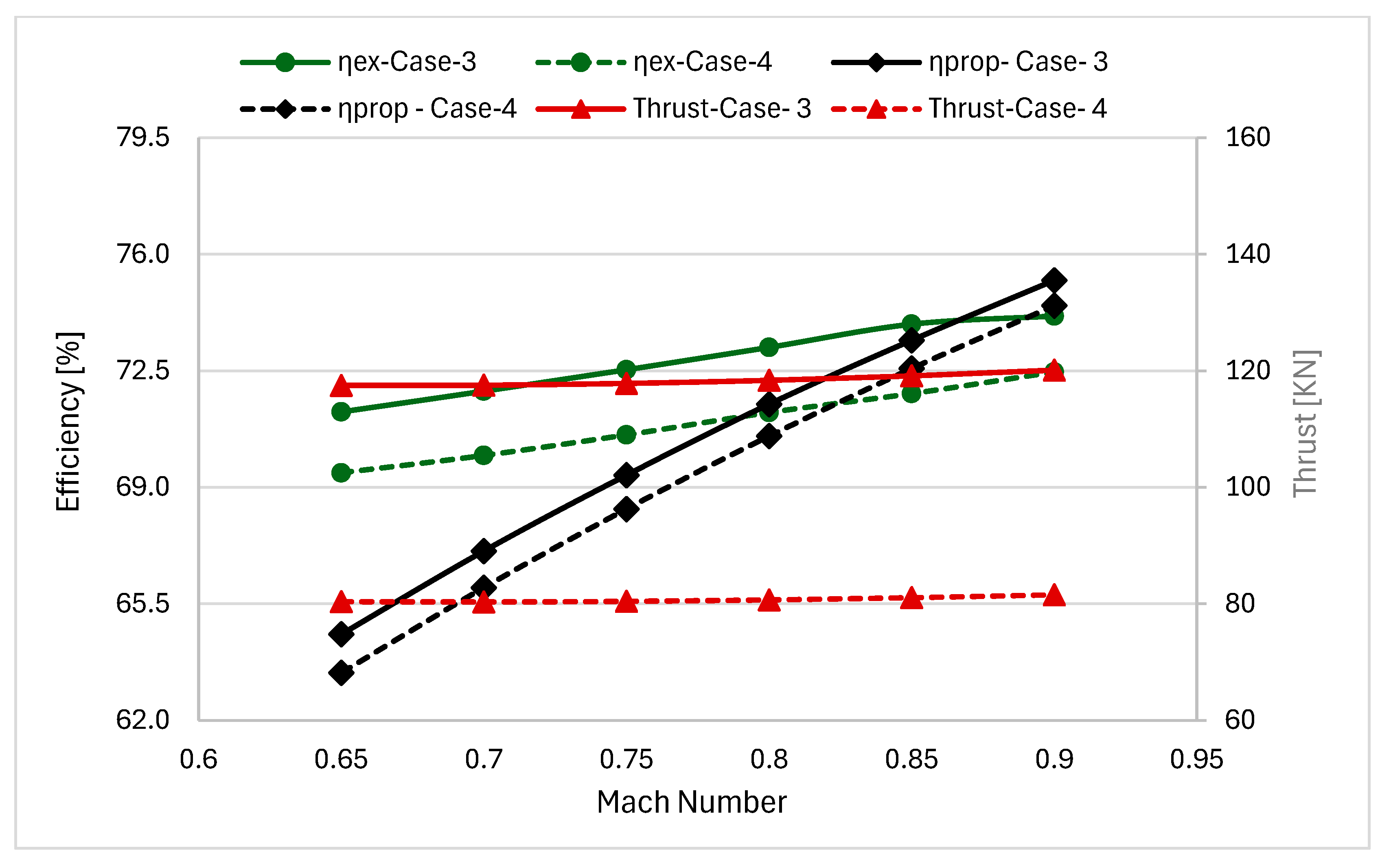

Figure 8 presents how flight Mach number (over the range 0.65 to 0.9) affects exergetic efficiency, propulsive efficiency, and thrust output for two turbofan engine configurations Case-3 (two-spool, high bypass ratio) and Case-4 (three-spool, moderate bypass ratio) during subsonic cruise at a fixed altitude of 10,000 m, constant shaft speed, and full nozzle expansion. It is clear from both these observations and the literature [

38] that three key aerothermodynamic factors drive the observed trends: momentum drag, ram compression, and ram temperature rise.

Momentum drag reduces net thrust as flight speed increases because the momentum change in the airflow is less significant, but it improves propulsive efficiency by enhancing momentum transfer, especially in high-BPR designs. To produce the same thrust at a higher flight speed, the engine must add less additional velocity per kilogram of air. Although the higher speed also increases mass flow through ram compression, the smaller velocity increment dominates, resulting in much less kinetic energy wasted in the exhaust jet. This is the primary reason propulsive efficiency rises with increasing aircraft speed. Ram compression improves performance by increasing inlet pressure and mass flow, boosting the nozzle pressure ratio. Flying faster rams more air into the engine inlet, providing free ram compression before the air even reaches the fan or compressor. At Mach 0.9, this ram effect alone raises inlet pressure by roughly 50–60% and increases air mass flow by 15–20%, delivering a significant thrust boost without any additional work from the compressor blades. It also allows the exhaust nozzle to expand the gases over a larger pressure ratio, improving nozzle efficiency and further increasing propulsive efficiency. Conversely, a rise in ram temperature increases the compressor inlet temperature, lowering both non-dimensional corrected speed (N/√Ta) and thermal efficiency, partially counteracting the ram compression benefits at higher Mach numbers. Compressing air heats it up—at M = 0.9, the air temperature rises about 50–70 K. This hot air is less dense (reducing some compression benefits) and makes the compressor less effective, decreasing efficiency by 2–3%. For Case-3, exergetic efficiency improves from about 71% to 74%, propulsive efficiency rises from 64% to 75%, and thrust increases slightly from 117 kN to 120 kN across the given Mach range. The gains resulting from increased ram compression outweigh momentum drag and temperature penalties, with the high-BPR design naturally favoring better propulsive efficiency due to a lower jet-to-freestream velocity ratio. Case-3’s large fan produces exhaust at 400–450 m/s. At slow cruise (M = 0.65), the jet is twice as fast as the plane. At fast cruise (M = 0.9), the jet is only 1.6 times faster. This better speed matching means less wasted energy, improving propulsive efficiency from 64% to 75%. For Case-4, exergetic efficiency increases from 69% to 72%, propulsive efficiency from 63% to 74%, though thrust remains stable at 80.0–81.5 kN, demonstrating the three-spool design’s ability to maintain aerodynamic performance across varying ram conditions despite lower overall thrust. Case-4’s three independent shafts allow each spool to run at its own optimum speed as flight conditions change. This keeps the fan, intermediate, and high-pressure compressor blades at their best flow angles despite varying inlet pressure and temperature, delivering consistent thrust and high efficiency across the entire speed range.

In the range Mach 0.65–0.9 during subsonic cruise, both Case-3 (two-spool, high BPR) and Case-4 (three-spool, moderate BPR) turbofan engines benefit from efficiency gains driven by ram compression, which outweighs moderate momentum drag and thermal penalties. Propulsive efficiencies for both converge to ~74–75% at higher Mach numbers, showing practical effects of high-subsonic flight dynamics. At high speeds (M = 0.9), both engines achieve similar jet-to-flight speed ratios despite different designs, so their propulsive efficiencies become nearly identical. Case-3 achieves slightly higher exergetic efficiency (74% vs. 72% at M = 0.9) fundamentally due to its lower specific thrust resulting from the high-BPR design, which directly enhances propulsive efficiency through reduced exhaust velocity and improved momentum transfer. Conversely, Case-4’s moderate-BPR configuration operates at higher specific thrust, yielding a more compact engine architecture but with inherently lower propulsive efficiency. Case-3 processes only 10% of air through the hot core where most losses occur, while Case-4 processes 15–18% through the core at higher temperatures. This means Case-4 has more combustion and heat losses per unit of thrust, resulting in 2% lower exergetic efficiency. Case-3’s high-BPR design optimizes bypass stream momentum transfer, while Case-4’s three-spool configuration maintains stable thrust (±2% variation), indicating lower sensitivity to speed changes and easier thrust management. Case-4’s three-shaft control system can reduce fuel flow as ram pressure increases, keeping thrust constant. Case-3 has less control flexibility, so thrust increases 2.2% as speed benefits accumulate. The increase in airspeed over the range M = 0.65–0.9 is aerodynamically favorable, with both Case-3 and Case-4 showing significant increases in propulsive efficiency (10.63% and 11.03%, respectively) and small but significant increases in exergetic efficiency (3.95% and 3.03%, respectively). Case 3 increased thrust by a mere 2.2% while Case-4 maintained thrust with an increase in only 1.47%.

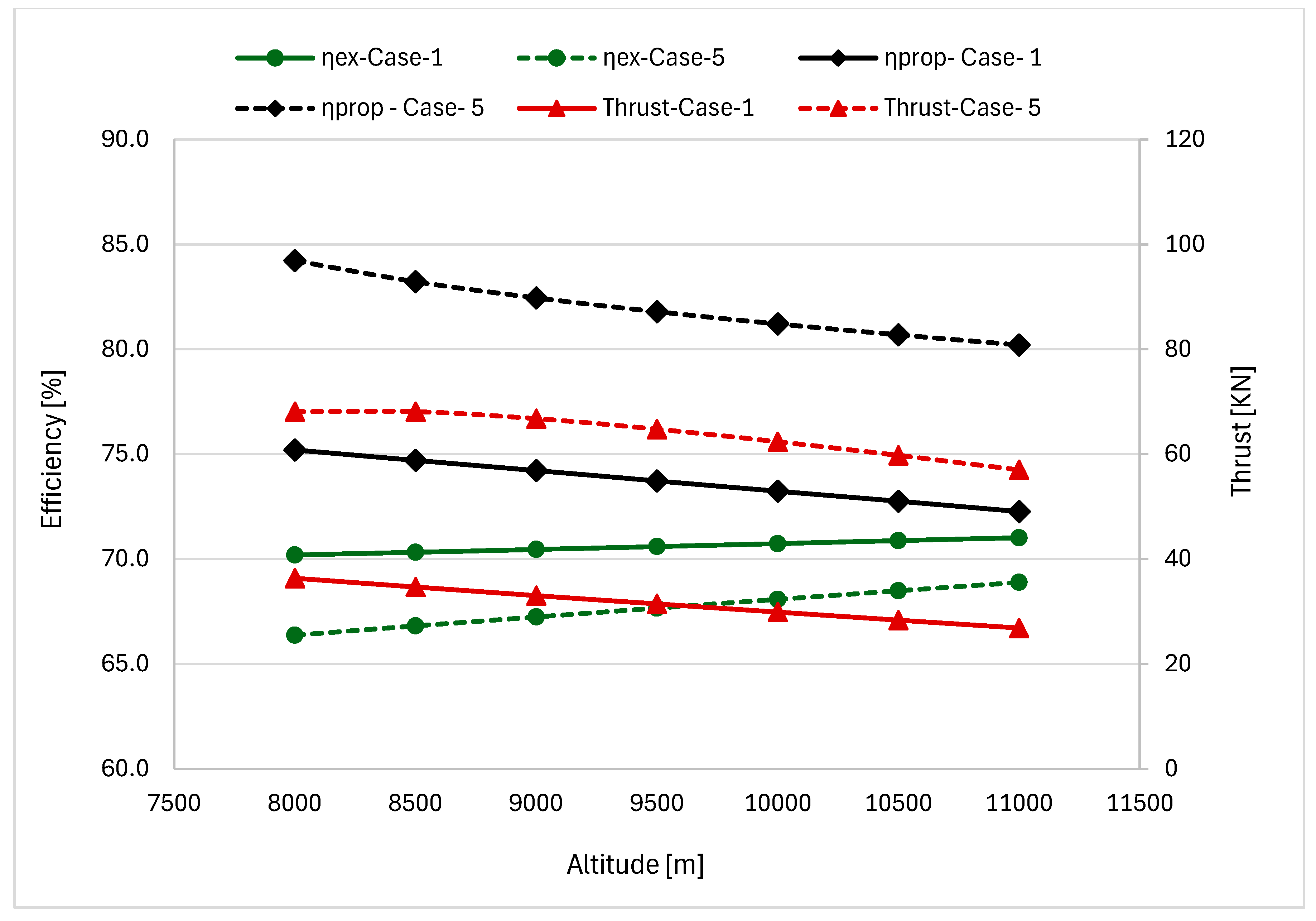

Figure 9 depicts the effects of altitude over the range 8000–11,000 m on exergetic efficiency, propulsive efficiency, and thrust output for Case-1 (two-spool, moderate bypass ratio) and Case-5 (three-spool, high bypass ratio) during subsonic cruise at a fixed Mach number (M = 0.8). The results reveal distinct performance characteristics and differing altitude sensitivities between the two engines. For Case-1, exergetic efficiency remains very stable across the altitude range, exhibiting minimal variation from 70.20% at 8000 m to 71% at 11,000 m. This near-constant behavior indicates robust exergy conversion and effective thermodynamic performance despite changing atmospheric conditions. Exergetic efficiency remains nearly constant with increasing altitude because two opposing effects cancel each other out: the thinner air at high altitude reduces engine mass flow, which tends to lower efficiency, while the much colder air significantly improves compressor and cycle efficiency, which tends to raise it. These two influences roughly balance, resulting in stable overall efficiency across the cruise altitude range. Propulsive efficiency decreases by only about 3% from approximately 75.2% at 8000 m to 72.3% at 11,000 m. This reduction reflects a modest diminution in propulsive effectiveness as altitude increases. At higher altitudes, less air goes through the engine, but the jet still shoots out at about the same speed. That means the exhaust is now moving much faster than the plane, so a bit more energy is wasted dropping propulsive efficiency by roughly 2–4%. From 8000 m to 11,000 m, air becomes about 30% less dense. Since thrust depends on mass flow, this reduces thrust, but only by around 26% because lower temperatures improve compressor efficiency, partially compensating for the density loss.

For Case-5, exergetic efficiency exhibits a modest but consistent upward trend, rising from approximately 67% at 8000 m to 69% at 11,000 m a relative improvement of ~2%. However, these values remain notably lower than for Case-1 over the entire altitude range, indicating that while the three-spool, high-BPR design shows improving thermodynamic efficiency with altitude, it operates at lower exergetic efficiency than the two-spool, moderate-BPR configuration. Case-5 performs better at higher altitudes because its large fan benefits from cold air: lower tip Mach numbers reduce shock and energy losses. Additionally, the three independent shafts allow each spool to adjust, maintaining efficient operation in thinner, colder air. Propulsive efficiency demonstrates superior absolute performance compared to Case-1, starting at approximately 84% at 8000 m and declining to 80% at 11,000 m. Despite this ~4% relative decrease—which is more pronounced than Case-1’s decline—Case-5 maintains substantially higher propulsive efficiency at all altitudes, highlighting the fundamental advantage of high-BPR designs in converting thermal energy into effective propulsive work. Thrust decreases significantly from approximately 70 kN at 8000 m to about 56 kN at 11,000 m, reflecting a notable ~20% reduction. While Case-5 generates higher thrust at lower altitudes compared to Case-1 (70 kN vs. 42 kN at 8000 m), its thrust reduces more sharply with altitude, resulting in lower thrust at 11,000 m (56 kN vs. 30 kN). This demonstrates that Case-5 is the more sensitive to altitude-related reductions in mass flow.

The two turbofan engines exhibit distinct responses to altitude variation, as described by the International Standard Atmosphere model. As altitude rises above sea level to the tropopause, decreasing air density reduces mass flow into the engine, leading to a notable decrease in thrust for both engines; with Case-1 showing a smaller reduction than Case-5. Falling temperatures increase the corrected speed, thereby enhancing compressor pressure and specific thrust, partially mitigating the thrust loss. Colder air improves compressor performance, allowing higher pressure ratios at the same shaft speed. This increases thrust per unit of air, partially offsetting the reduced mass flow and limiting the overall thrust loss at altitude. The performance differences between these configurations are fundamentally driven by specific thrust levels: Case-5’s high-BPR design operates at lower specific thrust, which directly enhances propulsive efficiency (80–84%) through reduced exhaust velocity and superior momentum transfer, resulting in improved fuel economy. Conversely, Case-1’s moderate-BPR configuration operates at higher specific thrust, yielding a more compact engine with higher exergetic efficiency (70–71%) but inherently lower propulsive efficiency (72–75%). Case-5 moves a large volume of air slowly, wasting little energy, while Case-1 moves less air faster, which wastes more energy but uses a smaller, simpler engine.

Case-1 delivers higher exergetic efficiency across altitudes, making it well-suited for diverse mission profiles. In contrast, Case-5 delivers enhanced propulsive efficiency, resulting in improved fuel economy at lower altitudes. Case-1 focuses on maximising exergetic efficiency, whereas Case-5 emphasises fuel conservation; however, both configurations demand precise thrust control at higher altitudes.

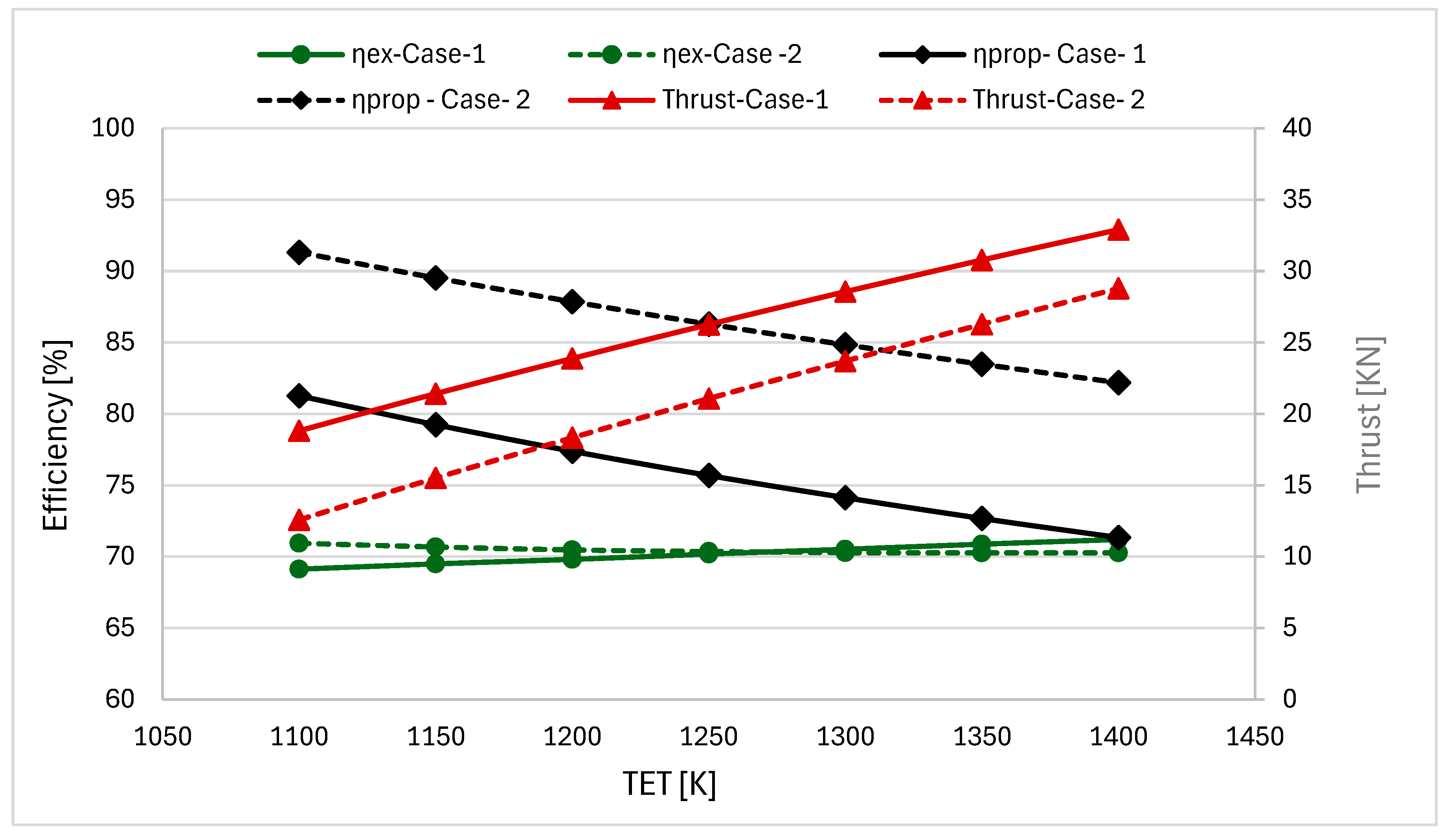

Figure 10 shows the performance characteristics of two turbofan engine configurations operating under cruise conditions (M = 0.8, altitude = 10,000 m).The solid and dotted lines represent Case-1 (OPR = 31, BPR = 5.7) and Case-2 (OPR = 43, BPR = 11), respectively. Both configurations exhibit a linear increase in thrust with turbine entry temperature (TET) across the investigated range of 1100 K to 1400 K. A higher TET results in more heat energy being added to the gas, leading to greater expansion and higher exhaust kinetic energy. Burning more fuel raises gas temperature, increasing turbine power proportionally and allowing the fan to accelerate more air, producing proportional thrust increases across the TET range.

In Case 1, the propulsive efficiency decreases from 81.2% to 71.3% because the jet velocity relative to the flight velocity increases, leading to greater energy loss in the exhaust stream. As TET increases, turbine power rises, causing the fan to rotate faster and increasing exhaust jet velocity. With flight speed remaining constant, the growing mismatch between jet and aircraft speeds leads to higher kinetic energy losses, reducing propulsive efficiency. The exergetic efficiency remains nearly constant at 69.1–71.2%, producing thrust levels of 18.8–32.9 kN. Over the examined TET range, exergetic efficiency shows little variation, indicating that the increases in fuel exergy input and useful propulsive output scale similarly, despite the significant rise in thrust. Case 2 achieves higher propulsive efficiency (91–83%) due to its larger bypass ratio, which reduces jet-velocity-mismatch losses. Case-2’s very high bypass ratio means that most of the airflow bypasses the core, keeping the exhaust jet speed relatively low even at high TET. Because the jet velocity remains closer to the flight speed, kinetic energy losses are reduced, allowing propulsive efficiency to remain high However, this improvement comes at the cost of lower absolute thrust output (14–30 kN) and the exergetic efficiency remains nearly constant at a slightly lower range of ~70–71%.The performance differences between Case-1 and Case-2 are fundamentally attributable to their distinct specific thrust levels: Case-2’s high-BPR design (BPR = 11) operates at lower specific thrust, directly enhancing propulsive efficiency (83–91%) through reduced exhaust velocity and minimized kinetic energy losses. In contrast, Case-1’s moderate-BPR configuration (BPR = 5.7) operates at higher specific thrust, delivering greater absolute thrust output but with inherently lower propulsive efficiency (71–81%). Case-1 produces thrust by accelerating a smaller mass of air to higher speeds, generating higher thrust but with greater energy losses. Case-2 accelerates a larger mass of air more slowly, producing lower thrust but with higher propulsive efficiency. The minimal variation in exergetic efficiency with change in TET for both cases indicates that it is the overall pressure ratio that primarily governs the thermodynamic performance under such cruise conditions. Exergetic efficiency is primarily governed by the overall pressure ratio, which sets the cycle’s efficiency ceiling. Since OPR remains constant for each case (31 for Case-1, 43 for Case-2) as TET varies, this ceiling does not change. Increasing TET mainly raises the energy throughput and thrust level without substantially altering the conversion efficiency, explaining why exergetic efficiency remains approximately constant (~70%) while thrust increases proportionally.