1. Introduction

Static line airborne operations remain a cornerstone of rapid military deployment, enabling the insertion of large numbers of troops into contested or austere environments [

1]. While this method has been used extensively since World War II, the complex aerodynamic and structural interactions between the jumper, aircraft, and static line still present unresolved challenges. One of the high-risk scenarios for injury during static line airborne operations occurs when a jumper fails to fully separate from the aircraft, becoming suspended mid-exit in what is commonly referred to as a “towed jumper” condition. Such events impose highly transient loads on the jumper and extraction system, creating serious safety risks.

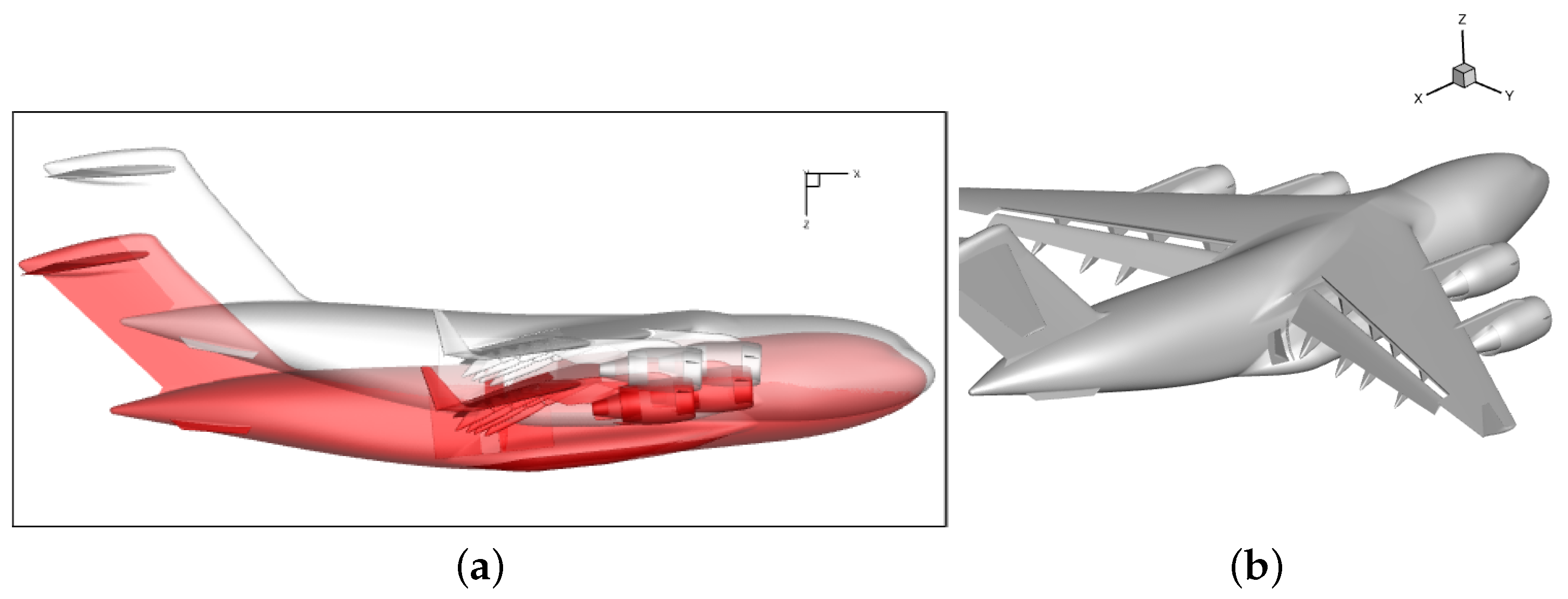

This computational analysis targets a malfunction scenario where a jumper transitions to a tow mode alongside an aircraft and is suspended from the troop door after experiencing a static line malfunction, which results in not deploying the main parachute properly. Three military transport aircraft are considered in this computational analysis and include: (1) C-17 Globemaster III, (2) C-130J Hercules, and (3) Airbus A400M Atlas. Each aircraft introduces distinct aerodynamic conditions at the troop door due to differences in fuselage geometry, propulsion configurations, and ramp designs. Notably, both the C-130J and A400M are equipped with spinning propellers, which generate highly three-dimensional unsteady wakes and blade-tip vortices that strongly interact within the troop door region. These propeller-induced flow structures introduce time-varying side forces, pitch-yaw moments, and asymmetric velocities that critically affect jumper dynamics.

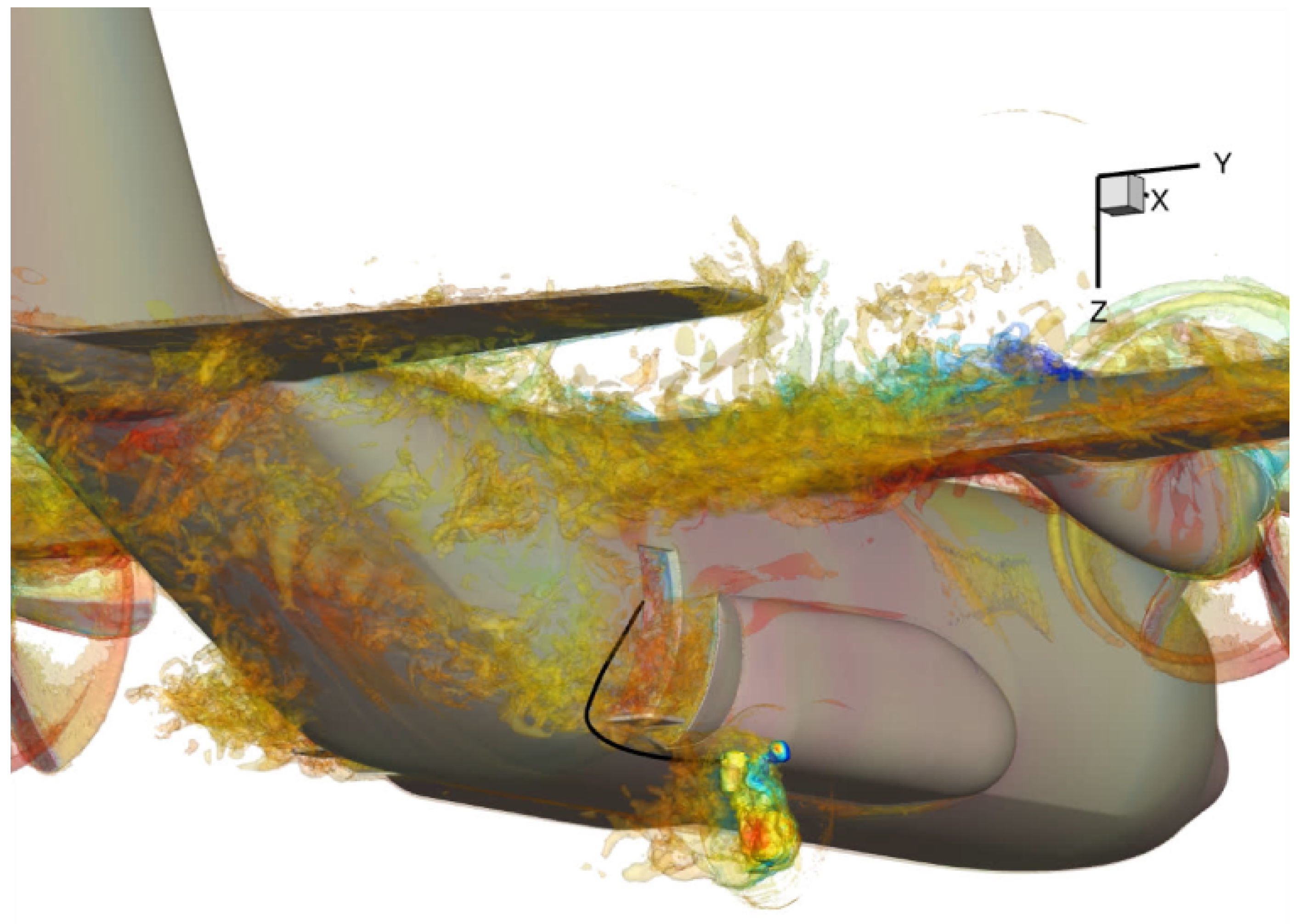

Figure 1 highlights the proximity turbulence near the troop door region and the propeller-induced flow structures from a C-130J. This simulation architecture represents the baseline case study that is investigated.

Furthermore, the region near the troop door features severe velocity gradients, as the local flow transitions abruptly from near-zero velocity inside the cabin to full freestream conditions just outside the air deflector [

2]. This abrupt transition forms a shear layer characterized by vortical structures and rapid pressure fluctuations. The air deflector, designed to mitigate this effect, can itself introduce new sources of unsteadiness, further complicating the flow field and increasing the risk of jumper-body or line-aircraft contact.

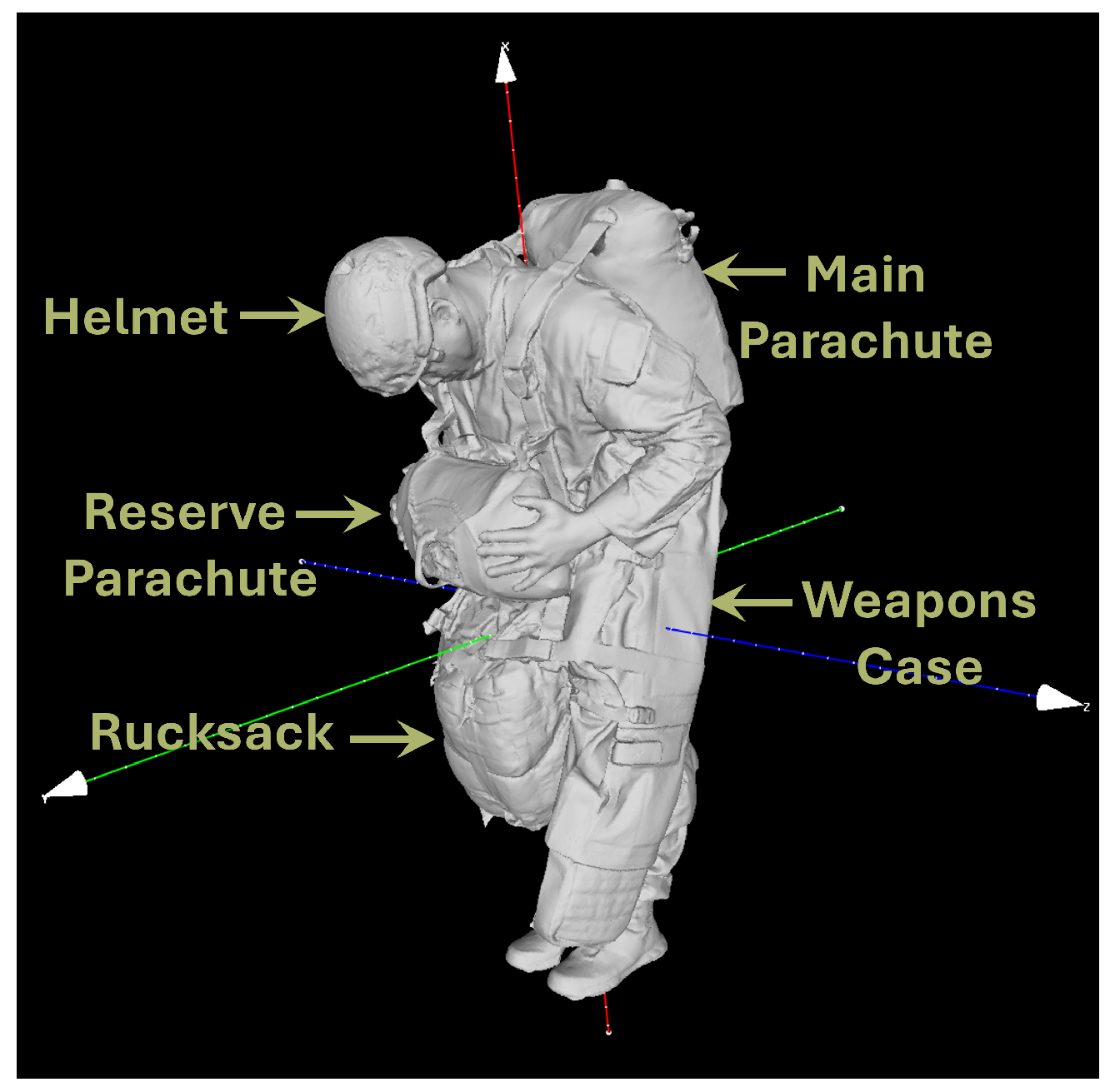

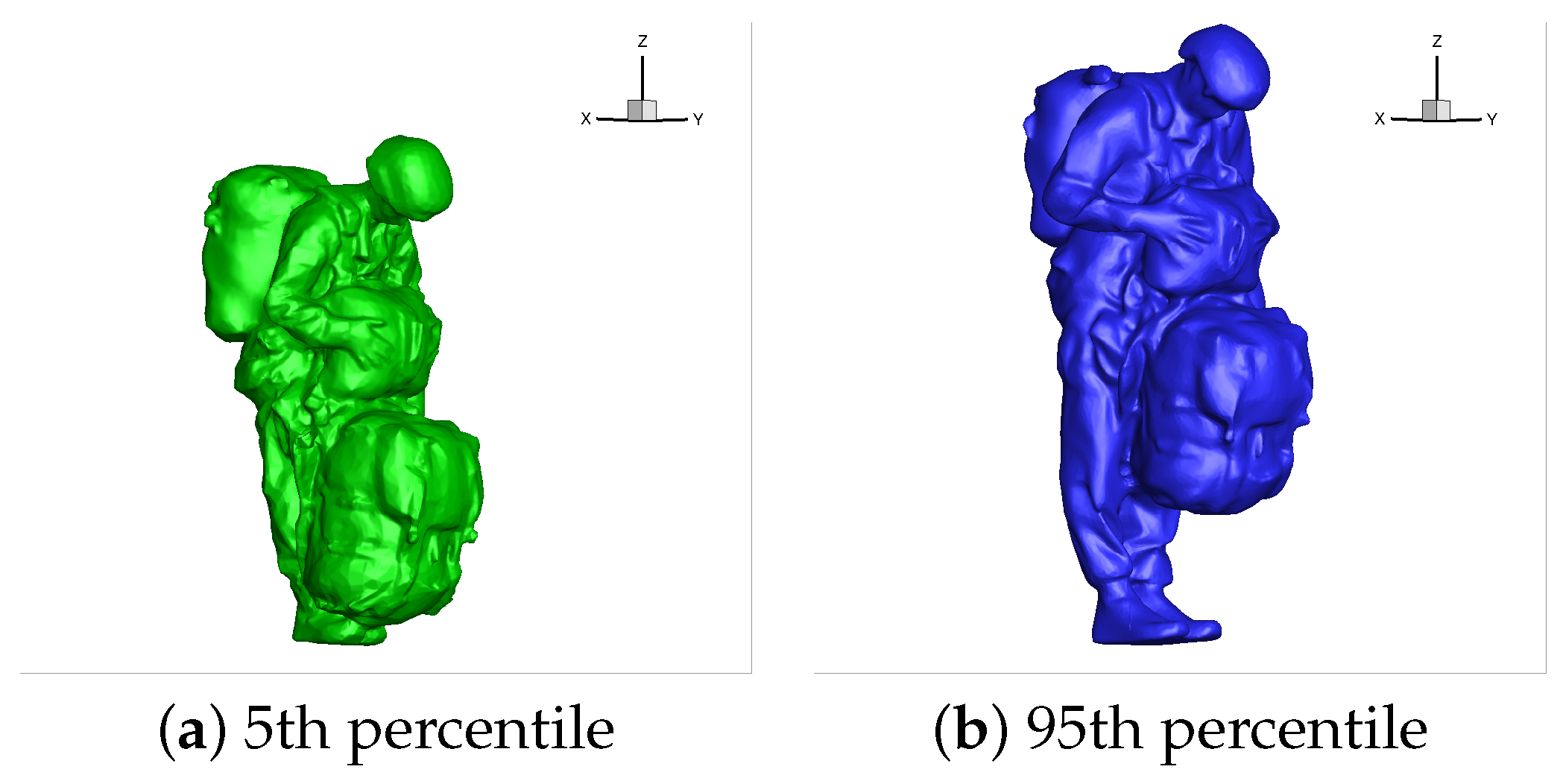

An additional layer of complexity is introduced to account for two areas of variability, which are physical characteristics and paratrooper equipment. Each paratrooper varies in height, weight and body shape ranging from the 5th percentile female to the 95th percentile male. During a static line airborne operation, a paratrooper requires standard equipment, which includes a main parachute, reserve parachute, weapons case, and rucksack.

Figure 2 shows a baseline paratrooper scan in full combat equipment with the weapons case on the left side in a nominal tight body position. Alternatively, off-nominal paratrooper scans were taken to consider the aerodynamic consequences for an improper exit. The combination of these variables introduces asymmetric shapes and off-center mass distributions. These first-order factors can lead to unpredictable rotation, tumbling or lateral drift immediately after exit.

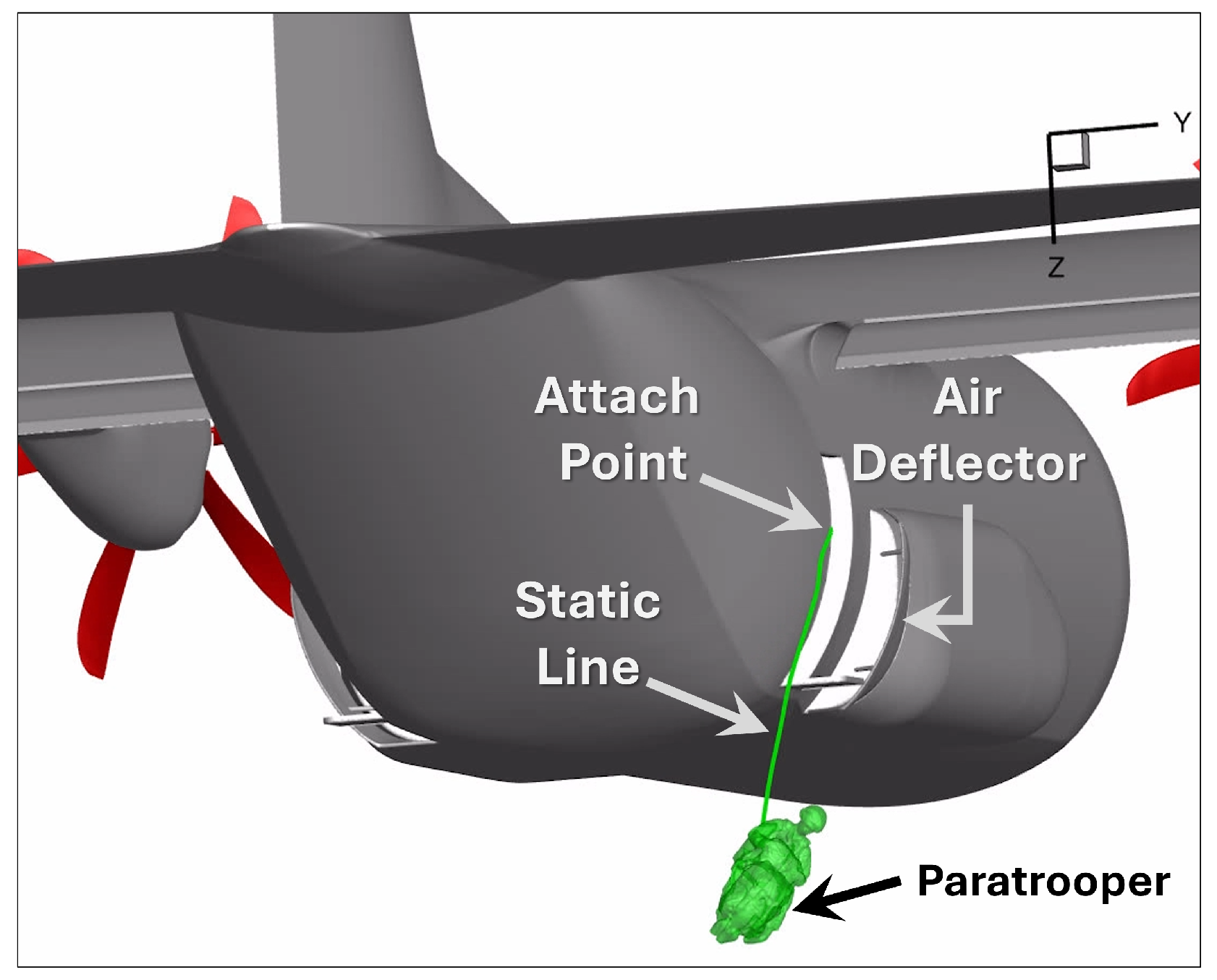

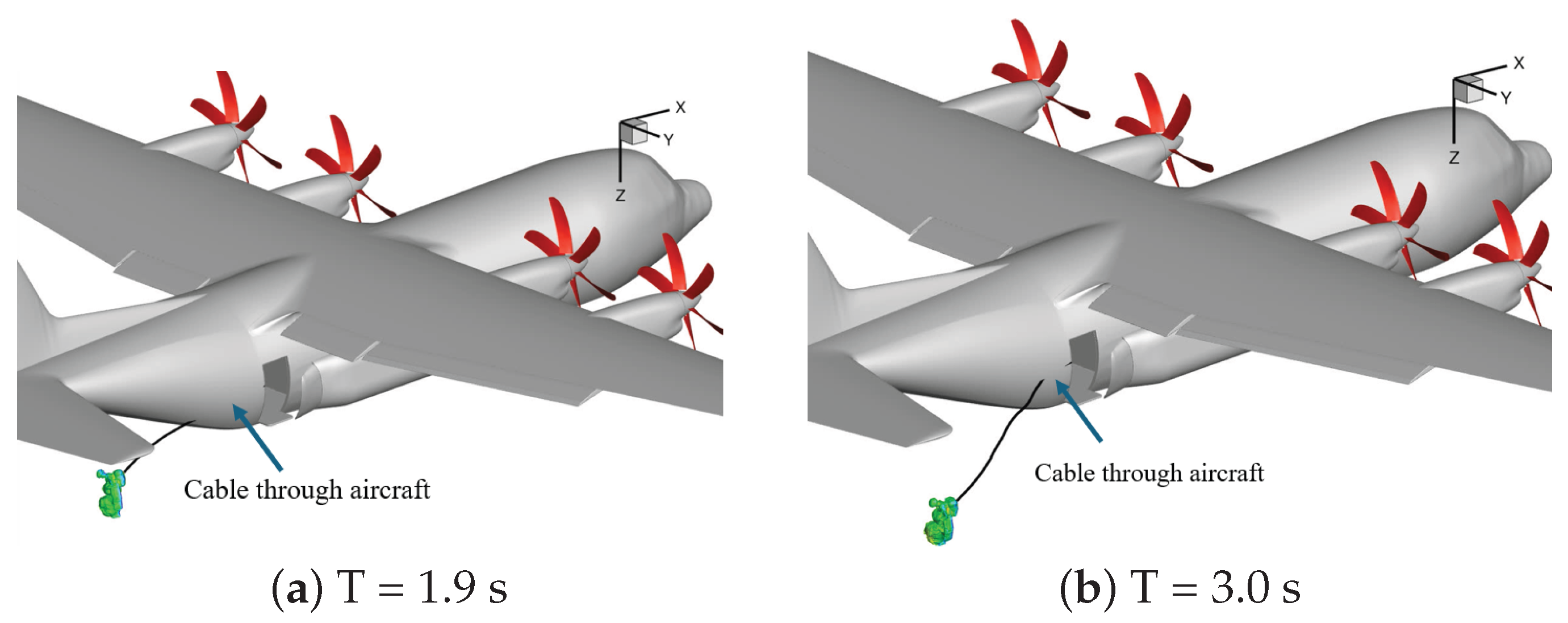

Kestrel, a high-fidelity time-accurate Computational Fluid Dynamics (CFD) simulation, is used to analyze the influencing factors and corresponding paratrooper responses in a towed configuration. The simulation capability incorporates 3D models that represent the paratrooper in full combat equipment plus comprehensive aircraft geometries with engines and, where applicable, rotating propellers. The paratrooper and aircraft are connected using a static line attached to the main parachute bag and at the troop door. Three general static line configurations are considered to help establish the workflow process for building and executing sensitivity studies using the following lengths: 15-ft, 17-ft and 20-ft. The static line behavior is modeled using Kestrel’s catenary model, which is viscoelastic and accounts for time-dependent deformation. The static line is comprised of a set of cables or discrete nodes connected end to end to an entity at a defined attach point, in this case, a paratrooper and aircraft troop door. The key inputs include cable diameter, mass, elastic modulus, and damping to capture representative material properties. The elastic modulus was initially tuned by performing a sensitivity study that focused on qualitatively correlating static line dynamics to the test video. The input modulus was systematically reduced from 100.0-GPa to 1.7-GPa to achieve realistic static line behavior. This approach was taken at the time due to the lack of available test data. The next study will incorporate stress-strain data to tune the input. A similar approach was taken to tune the static line damping after an elastic modulus was selected. Key developments that were accelerated to support this analysis included a body-cable contact model that prevented the static line from passing through the aircraft fuselage when engaged.

Figure 3 shows a nominal simulation run with the paratrooper in tow. The static line is attached to the troop door and the air deflector is active.

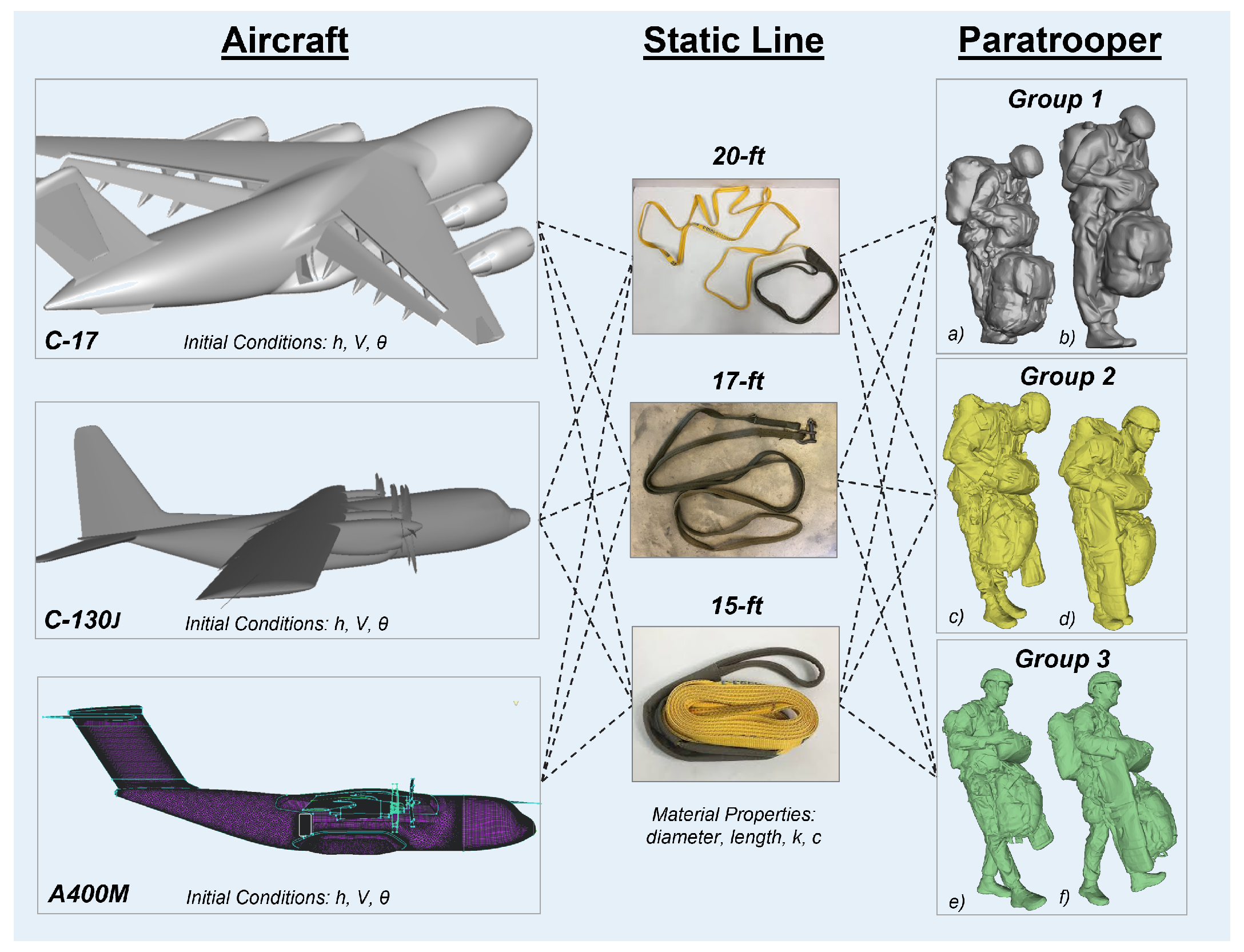

The fundamental performance questions from Army Personnel Airdrop and NATO Airdrop Interoperability stakeholders that enabled this analysis effort are: (1) Is there a Universal Static Line (USL) length that works across all aircraft types? (2) How does the USL performance vary from aircraft-to-aircraft? These questions are driving the development of an analysis matrix to identify the path needed to develop agile simulation capabilities that adapt to evolving analysis demands. A visual analysis matrix is shown in

Figure 4. The analysis matrix provides a high-level overview of the sensitivity studies needed to inform solutions for the fundamental performance questions. The first selection is aircraft type, which requires aircraft settings inputs, such as altitude, h, airspeed, V, and deck angle,

. The second selection is static line configuration, which includes defining a diameter, D, length, L, elastic modulus, E, and damping, C. The third selection is the paratrooper configuration, which is divided into three Groups. Group 1 represents the original scans used to develop this study. Group 2 and Group 3 are the latest paratrooper scans that use a medium rucksack with the weapons case on the left and right sides for future comparisons. Group 3 is critical to future evaluations due to the unfavorable body positions with the left and right legs elevated during the exit. This Group will help provide insight and help quantify the severity of the dynamics attributed to this body position. The weapons case has also been switched to the right side and in some paratrooper exits acts like a “Sail”, which could worsen dynamic effects. The primary configuration that was applied for the initial developments included a C-130J with a 20-ft static line attached to the Group 1 (a) paratrooper. While the present study primarily focused on the 5th percentile jumper, we have clarified in the revised manuscript that additional simulations with the 95th percentile jumper are ongoing. A sensitivity discussion has been added to highlight expected trends in dynamic stability and cable tension, and we reference these as part of future work to generalize the universality of the results, additional simulations with the 95th percentile jumper are ongoing.

Another selection point not captured by

Figure 4 is the output required to effectively compare each study to make informed performance decisions. Kestrel is configured to export relevant output at each timestep to support paratrooper stability studies. The output is categorized by paratrooper kinematics, cable tension force and aerodynamic forces and moments. For this case study, paratrooper kinematics output includes translational displacement, velocity, rotational rates and acceleration to track stability throughout the simulation run. A contact model is active between the paratrooper and fuselage to monitor contact points and identify unfavorable static line lengths or aircraft settings. The static line tension force is monitored to verify that the line has not exceeded any physical limits that would indicate a failure. Output includes tension, stress and strain. Aerodynamic forces and moments on the paratrooper and aircraft are monitored to understand the magnitude of their effects and interactions under specified aircraft conditions. The purpose of defining the baseline output is to ensure the correct variables are saved to support projects evaluating design decisions to mitigate risk factors affecting a paratrooper during standard exits. A sample of the output generated is shown in

Figure 5 with a highlight on the paratrooper translational displacement and static line tension. During initial simulation functional checkouts, the displacement outputs identified a contact event between the paratrooper and fuselage. As a result, the event was analyzed, and a need was identified to consider integrating a contact definition between the static line and fuselage. Similarly, the peak load event confirmed additional tuning was required for the static line material properties to mitigate the transient load identified. Consequently, the paratrooper experienced transient acceleration, and an iterative approach was taken to tune input parameters to generate representative performance predictions. No measured test data was available during this development, and the test video was the primary source to qualitatively verify simulation performance. Additional data sources will be available on future static line airborne operations, such as an external camera door view for enhanced exit views to support simulation developments.

The output from the computational analysis will be used to evaluate key performance parameters (KPPs), monitor event sequences and contribute to the following objectives:

Identify contact risks for specified aircraft conditions.

Evaluate universal static line lengths to enhance operational performance.

Inform effectiveness of design selections to mitigate paratrooper risks.

Enhance Airborne Tactics, Techniques, and Procedures (TTP).

This work presents the first comprehensive computational study modeling a fully operational aircraft towing a paratrooper under failure conditions. The simulation incorporates true-to-scale paratrooper geometries and utilizes propeller-resolved flow fields across various aircraft models. Significant development and tuning were required for the catenary model to mitigate transient loading. Contact and damping features were implemented in the catenary model and used to qualitatively match static line behavior observed in test videos. This framework streamlines CFD analysis, accelerating setup, execution, and the delivery of results for performance insight gains. These insights aim to enhance the safety and effectiveness of airborne operations and establish a foundation for future work in paratrooper trajectory prediction, equipment design, and operational risk assessment.

The organization of this paper first takes a look back at the history of personnel exit simulations with a focus on modeling techniques, then describes the computational approach taken for this framework using specific test cases that were used to debug and impact current simulation developments. A sample of the simulation results will be reviewed along with a summary of the current state-of-the-simulation and future efforts that will enhance CFD analysis for this area of study.

2. Background

The reliability and safety of static line systems in military airborne operations have been the subject of extensive experimental and computational research. To make the progression of prior work explicit, we split the literature review into two concise tables.

Table 1 summarizes foundational studies on materials/operations and low-order dynamics.

Table 2 collects high-fidelity CFD efforts and positions the present work relative to them. Together, these tables clarify that earlier research addressed important components of the problem, while the current study is the first to couple time-accurate CFD with a viscoelastic static line (with damping/contact) for the towed-jumper malfunction across multiple aircraft.

Early efforts focused on material performance and protective hardware. Millette et al. [

3] conducted a detailed experimental program to evaluate the effective strength of static lines under conditions simulating towed jumper incidents. Tests compared standard Type VIII nylon webbing with the AbsorbEdge

TM material and demonstrated superior energy absorption and rupture resistance for the latter. However, line routing over aircraft structures, twisting, and abrasion at door edges or jump platforms significantly reduced strength. Protective measures such as cotton sleeves and platform interface boots mitigated some risks, underscoring the importance of both material enhancements and hardware design in accommodating heavier paratroopers.

Complementary work examined operational deployment of static line systems in realistic aircraft environments. Siiropaa et al. [

4] investigated the T-10 parachute system deployed from an NH90 helicopter. Their flight tests highlighted the influence of anchor point configuration on static line dynamics and safety. Ceiling-mounted anchors produced unpredictable motion and structural contact, whereas a floor-mounted PASI-1 anchor system provided greater control and reduced risk of entanglement. These results offered practical guidance on jumper positioning, anchor design, and exit procedures, confirming safe operations within airspeeds of 90–150 knots.

Building on these experimental insights, modeling studies have addressed the hazardous towed-jumper scenario. Furlani et al. [

5] developed a MATLAB-based dynamic model incorporating a nonlinear viscoelastic representation of the static line, calibrated with experimental data. Simulations showed that heavier jumpers and higher airspeeds substantially increased peak impact forces, often exceeding both human injury thresholds and the dynamic tensile strength of Type VIII webbing. The study emphasized the need for stronger static line materials and updated safety limits, while offering a framework for future validation with instrumented dummies.

At larger scales, Mariscal-Sánchez et al. [

8] advanced a comprehensive simulation framework for mass airdrop operations from the A400M aircraft. Their model integrated point-mass dynamics, finite-element methods, and semi-empirical canopy inflation models to capture the sequence from free fall to full canopy deployment. Aerodynamic inputs from CFD and wind-tunnel data allowed realistic treatment of the aircraft wake, while Monte Carlo analyses quantified variability due to paratrooper mass and flow conditions. The predictions aligned with flight imagery and provided valuable support for risk assessment and aircraft certification.

Theoretical advances in flexible-body modeling further strengthened these efforts. Newman and Karniadakis [

6] demonstrated how lift-induced vibrations and wake interactions influence cable dynamics, while Quisenberry and Arena [

7] compared lumped-mass and thin-rod models for aerial tow systems. Their work confirmed that thin-rod formulations achieve higher dynamic fidelity with fewer segments, offering computationally efficient tools for modeling static line dynamics.

High-fidelity computational fluid dynamics (CFD) has recently been brought to bear through the HPCMP CREATE

TM-AV Kestrel suite. Kestrel provides time-accurate simulations of personnel and cargo airdrops, integrating near-body structured and Cartesian off-body grids with adaptive mesh refinement. For cargo operations, catenary cable models capture interactions between payloads, extraction parachutes, and suspension lines [

9]. For personnel airdrops, human body models derived from 3D scans allow detailed six-degree-of-freedom simulations of jumper trajectories and interactions with aircraft wakes [

10]. Recent work by Ghoreyshi et al. [

11] demonstrated that even minor asymmetries in mass distribution or exit orientation can significantly alter jumper dynamics in the first seconds post-exit, heightening risks of entanglement or collision.

Overall, this body of work shows the progression from material testing and operational evaluations to dynamic modeling and high-fidelity CFD. Together, these studies highlight the complex interplay of static line strength, deployment mechanics, and unsteady wake aerodynamics, and they establish the foundation for future improvements in safety, design, and training for military airdrop systems.

3. Formulation

We solve the unsteady, three-dimensional, compressible Reynolds-Averaged Navier-Stokes (RANS) equations for a calorically perfect gas

where

is the vector of conservative variables,

and

are inviscid and viscous fluxes, and

collects source terms (e.g., gravity if included). Turbulence closure uses standard one- and two-equation models (Spalart-Allmaras, SA-RC, and SST), and selected runs employ hybrid RANS-LES (DDES) where separated wakes were noted. Farfield, wall, and moving overset interfaces follow conventional formulations.

For reproducibility, the simulations are executed with the HPCMP CREATE

TM-AV

Kestrel environment (v12.4), which provides the CFD—multibody coupling and mesh motion infrastructure used here [

12,

13,

14]. Specific discretization and solver internals (flux formulas, time integrators, etc.) follow the standard Kestrel defaults and are not central to the contributions of this work.

3.1. Rigid-Body and Multibody Dynamics

The aerodynamic loads from the flow solution are coupled to six-degree-of-freedom (6DOF) rigid-body equations for the jumper. In body axes,

with mass

m, inertia tensor

, translational velocity

, and angular rate

. The jumper body in this study undergoes a responding motion, where states advance under the coupled loads [

15].

3.2. Catenary Cable Model (Static Lines and Tethers)

Flexible tension members (static lines, suspension ropes, tow cables) are represented by a lumped-mass catenary chain. Nodes of mass

are connected by tension-only segments; nodal equations are

where

is the axial tension,

the weight,

c a local damping coefficient, and

the aerodynamic load. Axial tension follows a linear elastic law,

with Young’s modulus

E, area

A, rest length

, current length

, and unit vector

. Aerodynamic drag uses an inclined-cylinder approximation,

with local density

,

, and relative velocity

. Cable endpoints attach to moving bodies so that tensions transmit loads bidirectionally between the cable and the 6DOF system. Time marching is consistent with the multibody update used for responding motion. Cables are modeled as tension-only (no bending or torsion), do not shed wakes, and do not directly modify the CFD field; cable–surface contact is included where noted, while cable–cable contact is not modeled.

Please note that the present modeling framework incorporates cable elasticity, damping, and cable–airframe contact, but it does not explicitly resolve wake–cable interactions. This simplification may underpredict certain oscillatory behaviors or dynamic loading effects. In the revised manuscript, we have more explicitly acknowledged this limitation and outlined future directions for model development. Planned improvements include the introduction of torque damping to mitigate unrealistic angular excursions, incorporation of flow-induced vibration modeling, and enhanced cable–flow coupling strategies. These advancements are identified as priorities for upcoming work to improve the physical fidelity of the simulations and provide more accurate predictions of towed jumper dynamics.

4. Test Cases

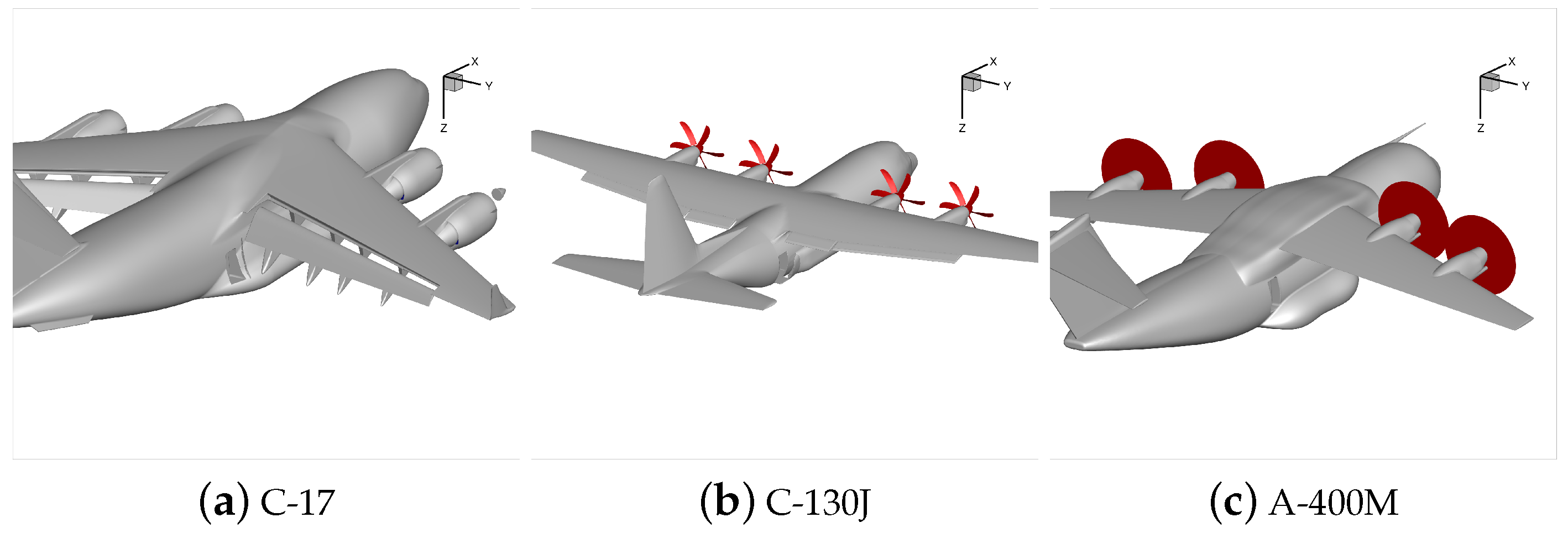

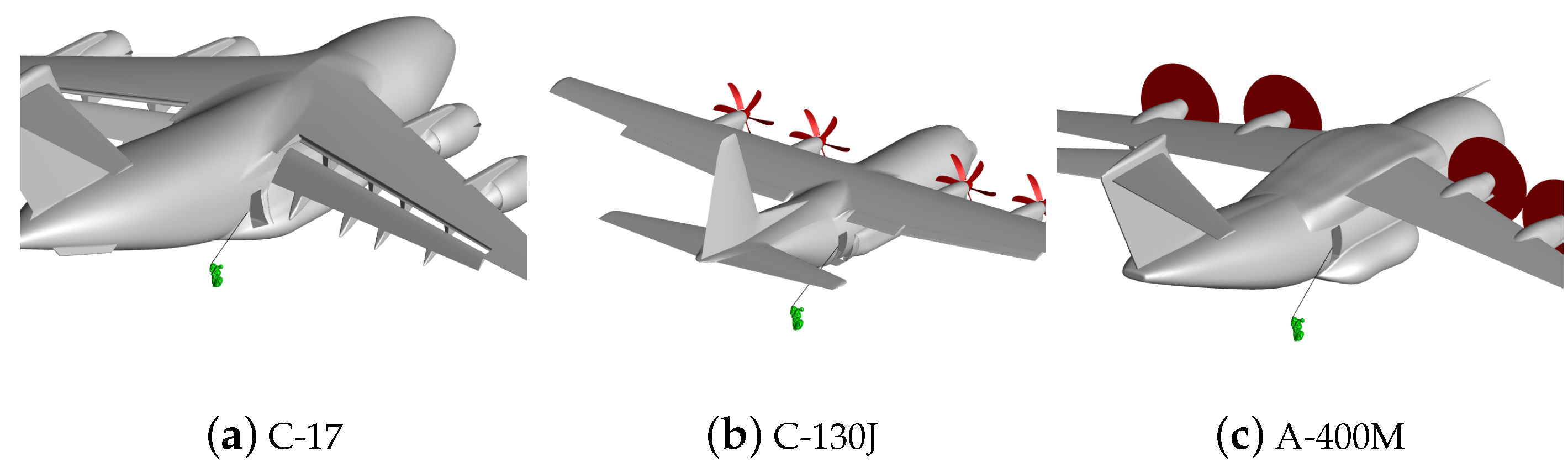

Airdrop configurations using a C-17 Globmaster, C130J, and A400M are considered. The computational models of these aircraft are shown in

Figure 6.

The C-17 configuration used in this study is similar to the one used in Refs. [

16,

17]. This geometry is shown in

Figure 7 and has a deck angle of six degrees. The C-17 aircraft model, used here, has four F117-PW-100 Turbofan engines, an open troop door, and flaps extended. This geometry includes the asymmetric fuselage resulting from the addition of the auxiliary power unit on the starboard side of the aircraft. For comparison, the C-17 initialized with a zero- and six-degree deck angle is shown in

Figure 7.

It is important to note that, in the computational models, each engine has an inlet plane modeled with a sink boundary condition, along with two exhaust planes incorporating source boundary conditions for both core (hot) and bypass (cold) exhaust flows. The engine exhaust conditions are set to correspond to Mach 0.78 and a bypass ratio of 5.9.

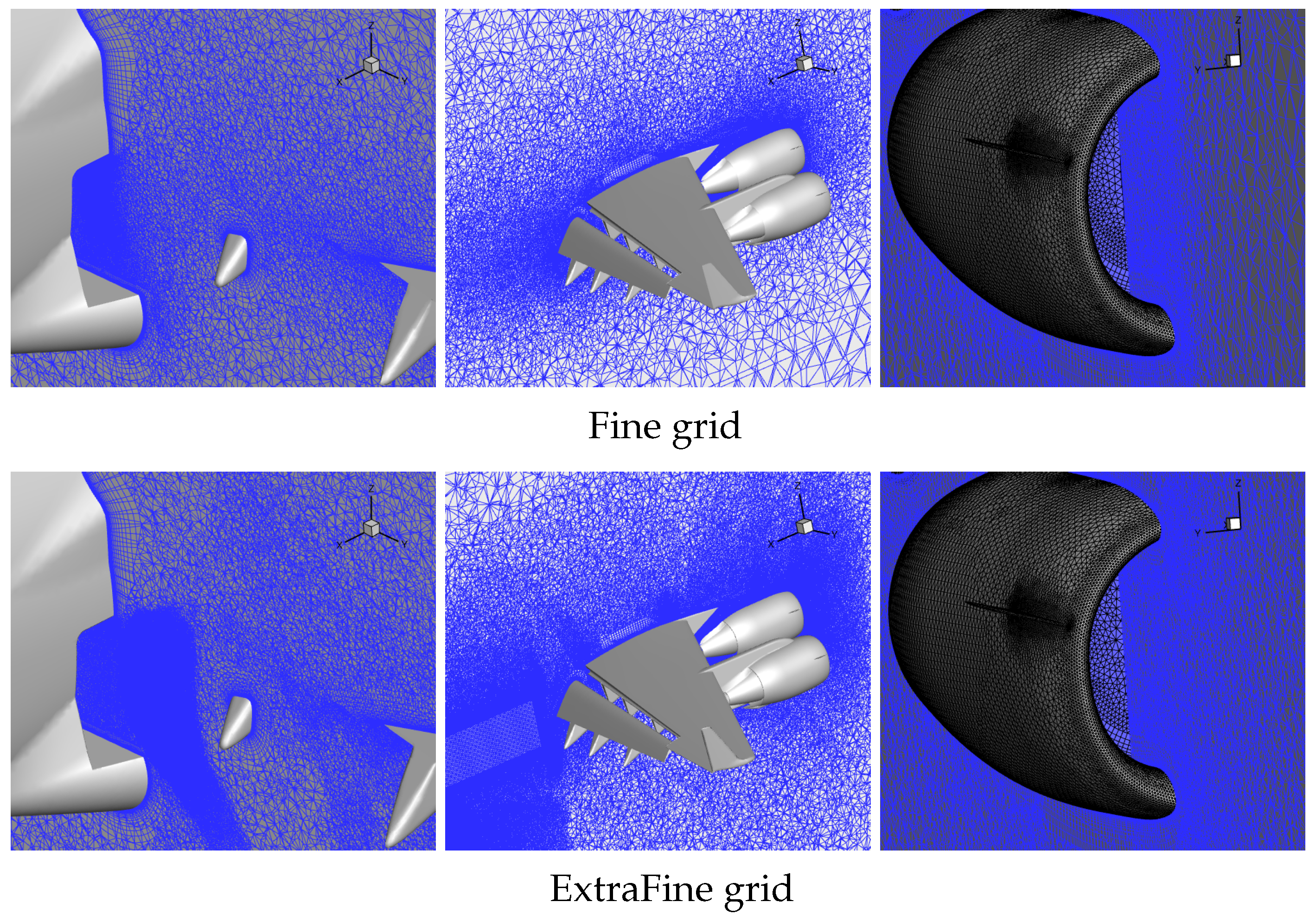

For this study, we developed several computational meshes. Two sets of computational grids were generated for C-17, a Fine and an ExtraFine grid. The Fine grid has 75.5 million cells. The ExtraFine Grids have regions of refined mesh around the troop door and behind the engine exhausts. This grid has approximately 274 million cells. These grids are compared in

Figure 8. The surface mesh remains identical to those used in previous studies [

16,

17]. However, compared to earlier meshes, we added several density boxes positioned behind the aircraft and around areas where we anticipate paratroopers. These density boxes consist of structured mesh blocks, which are easier to construct and provide higher-quality cells. This approach is particularly beneficial in regions of highly unsteady flow, such as the flow around a paratrooper. The size and placement of these blocks were informed by previous results, which indicated the likely positions of paratroopers over time.

For the A-400M, we designed a mesh incorporating similar density boxes as those used for the C-17. Since the two aircraft are comparable in size and shape, we could estimate the paratrooper’s position behind the aircraft and align the density boxes accordingly. The cell sizes within the density boxes are consistent with those used for the C-17. Due to the lack of detailed propeller geometry for the A-400M, we utilized propeller discs with the same diameter as the actual propellers. This consistency in density box topology across the C-17 and A-400M meshes allows for direct comparison of CFD results between the two aircraft.

Additionally, we embedded troop door geometries into the A-400M meshes. Three configurations were created: one with the troop door on the right side, one on the left side, and one with both doors modeled. The A400-M grid has about 193 million cells.

Similar density boxes were also added to the C-130J mesh to reduce variability across different meshes. This consistency minimizes mesh-induced variability, ensuring a more reliable comparison of results across the three aircraft. The C-130J grid has about 442 million cells. The propulsion systems considered were Dowty six-bladed R391 propellers. Propellers were resolved using full blade geometries. Each propeller contains about 50 million cells.

Jumper models are the product of a whole-body laser scanner system available at DEVCOM-SC which can generate high resolution data set of the outer surface of a human body [

18]. The Cyberware WB4 uses a 4 camera-laser system mounted on vertical posts to capture 1000 horizontal slices over a maximum height of 2 m during a 17 s sweep. The resulting data sets of between 300,000 and 500,000 points are post-processed to construct the watertight geometry shown.

Two jumper models were generated. The green model in

Figure 9 represents a 5th percentile paratrooper with several equipment containers, including the main parachute container on the back of the model and the reserve parachute container, which is below the hands of the model. While this configuration can serve to produce high-fidelity simulations for a general study, an additional set of models was produced in order to capture size, profile, center of gravity, and moment of inertia dependencies on exit dynamics. The blue model of

Figure 9 represents a 95th percentile paratrooper. For results reported in this project, the mass distribution throughout the model is assumed to be uniform, and therefore does not distinguish among the different densities associated with each of the components.

5. Computational Setup

All simulations were conducted using CREATETM-AV/Kestrelversion 12.9 with second-order accuracy in both space and time. The compressible Navier-Stokes solver was employed with the SA-RC turbulence model in Delayed Detached Eddy Simulation (DDES) mode. A fixed Newton sub-iteration count of eight was used throughout. The inviscid flux was computed using the HLLE++ scheme, paired with an Alpha-Damping viscous flux approach. The simulation used a Weighted gradient method, stencil type FN1, and enabled WallFunctions for near-wall resolution. Fluid gravity was neglected, and species transport was handled using a segregated strategy with area-weighted sliding interfaces.

Each aircraft model was stationary during the simulations, with propulsion modeling specific to the platform: the C-17 used prescribed inlet and exhaust boundary conditions, including hot/cold mass flow rates and temperatures; the C-130J featured rotating propeller blades and spinner via prescribed motion; and the A400M employed actuator disks driven by user-defined thrust values, distributions, and angular velocities.

The simulations were performed at an altitude of 1250 ft AGL, 130 KCAS, and a deck angle of 6°, with zero angle of attack and sideslip. The 5th percentile jumper was modeled with a total mass of approximately 243.7 lb, converted from 0.631 snail. The jumper’s moments of inertia in the body frame were: , , and . Products of inertia included , , and . The output reference point was located at (0.0, , ) in, typically near the jumper’s static line attachment.

Simulations began with 1500 startup iterations, during which time remained static and no motion or cable dynamics were activated. The dynamic simulation proceeded for an additional 10,000 iterations using a timestep of 0.001 s, totaling 10 s of physical time. At iteration 1500 (time zero), body motion for propellers and catenary dynamics were initiated. The jumper was permitted to move freely starting at iteration 2000 (0.5 s), at which point contact detection with the aircraft was enabled. Kestrel automatically detected and reported jumper-aircraft contact points.

The catenary model used a coordinate system xByRzU and operated in the ISS (Inch-Slug-Second) unit system. The static line was modeled as a cable with 60 links, 204 inches total length, 0.036 slugs mass, 0.5 inch diameter, and a modulus of elasticity of 1.7 GPa. The cable endpoints were fixed to the aircraft (C17Body) and jumper (JumperBody), enabling coupled motion via aerodynamic forces from the flow solution. Contact detection with the aircraft was activated using a 1.0 inch threshold. The solver applied a convergence tolerance of , with up to 200 iterations per time step and 5000 during initialization. A time-step limiter of 0.05 s was enforced with up to 500 limited iterations. Output was written in VTK Legacy format for visualization.

All simulations were executed on the DoD HPCMP ERDC Carpenter supercomputing facility. The primary test case investigated the dynamics of a jumper connected to a 17 ft static line attached between the aircraft troop door and the jumper’s main parachute deployment bag. Jumper initial positions, shown in

Figure 10, were varied to evaluate the effects of positioning on exit dynamics. These included uniform offsets in the

x,

y, and

z directions and alignment with an expected jumper exit trajectory.

6. Results and Discussions

A MATLAB-based code and graphical user interface (GUI) named Multi-Body Aerodynamics was developed to facilitate the analysis of towed-jumper simulations. The tool is designed to parse and interpret Kestrel-generated outputs, including log files, tracking data, and Catenary data.

From the log files, the code extracts freestream conditions and details of the CFD setup. It also identifies any jumper-to-aircraft contact events, reporting the contact times and corresponding locations on the aircraft surface. Additionally, the code summarizes the number of startup and main iterations performed during the simulation.

The tracking data is used to extract aerodynamic and external forces and moments acting on the jumper. If any contact events occurred, the corresponding contact points are highlighted using symbols in the generated plots. The tracking data also includes jumper motion information, from which translational and rotational kinematics are extracted. Velocities and accelerations are computed based on the translational displacement history.

The Catenary data provides time-resolved cable information, including total length, stress, and tension. The code reports maximum tension, stress, and strain values, along with their corresponding segment indices (link numbers).

When surface mesh data is available, the code also enables basic visualization capabilities for preliminary inspection of the jumper and cable configurations.

It should be noted that, while the present study demonstrates the ability of Kestrel to capture complex unsteady wake structures, we acknowledge the limitation that direct validation data remain limited for the troop door region. To address this gap, ongoing efforts are dedicated to acquiring high-quality flow visualization and test datasets, including external door camera imagery and supporting flight measurements. These forthcoming data will allow more direct comparisons with CFD predictions, strengthen the validation of wake dynamics such as tip vortices and shear layer fluctuations, and ultimately enhance operational confidence in the use of high-fidelity simulations for risk assessment and safety evaluation in airdrop operations.

6.1. Grid Sensitivity and Baseline Results (C-17 Case)

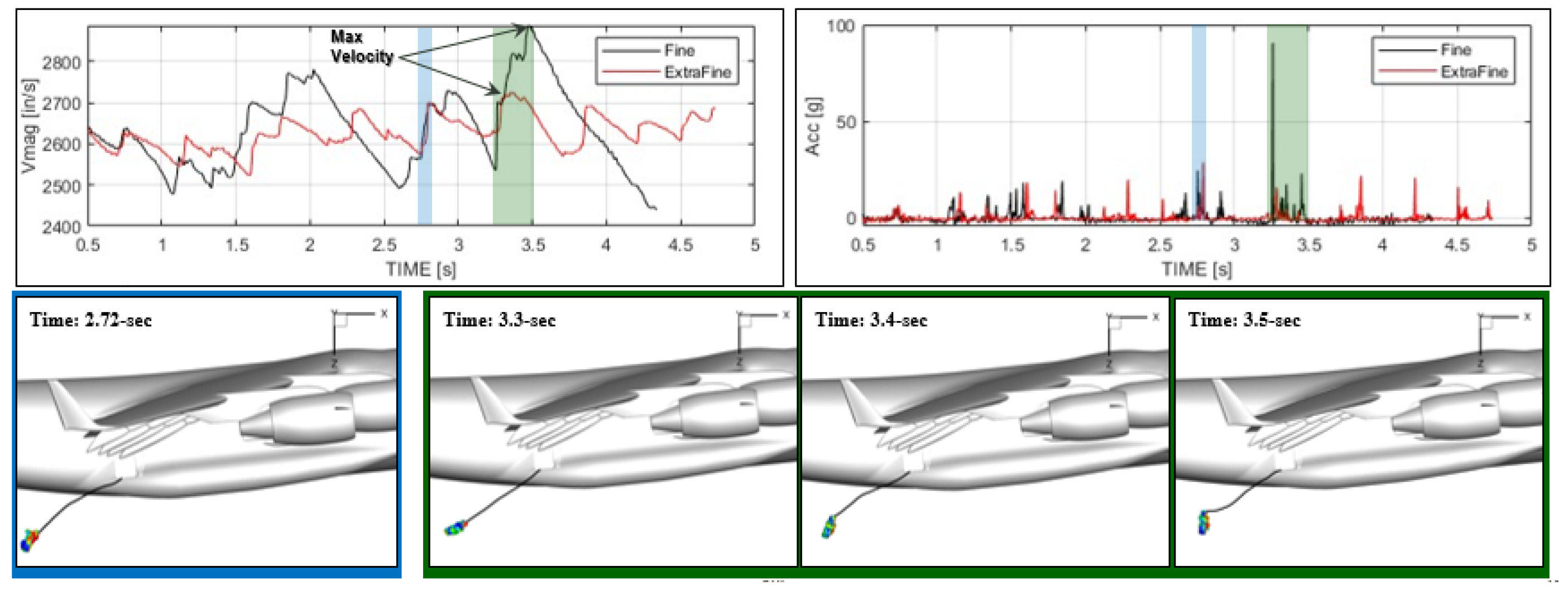

Initial results focus on the C-17 simulations involving a 5th percentile jumper connected via a 20-ft static line. Two computational grids were used: a Fine Grid and an ExtraFine Grid, with the second one refined near the troop door and behind the engine exhausts to better resolve local flow structures. The jumper begins from a prescribed initial position and responds dynamically to the aircraft’s near-field flow, gravity, and tension in the static line.

Figure 11 compares flow fields at the initial time, highlighting that the ExtraFine Grid better captures detailed flow features around the troop door and exhaust region.

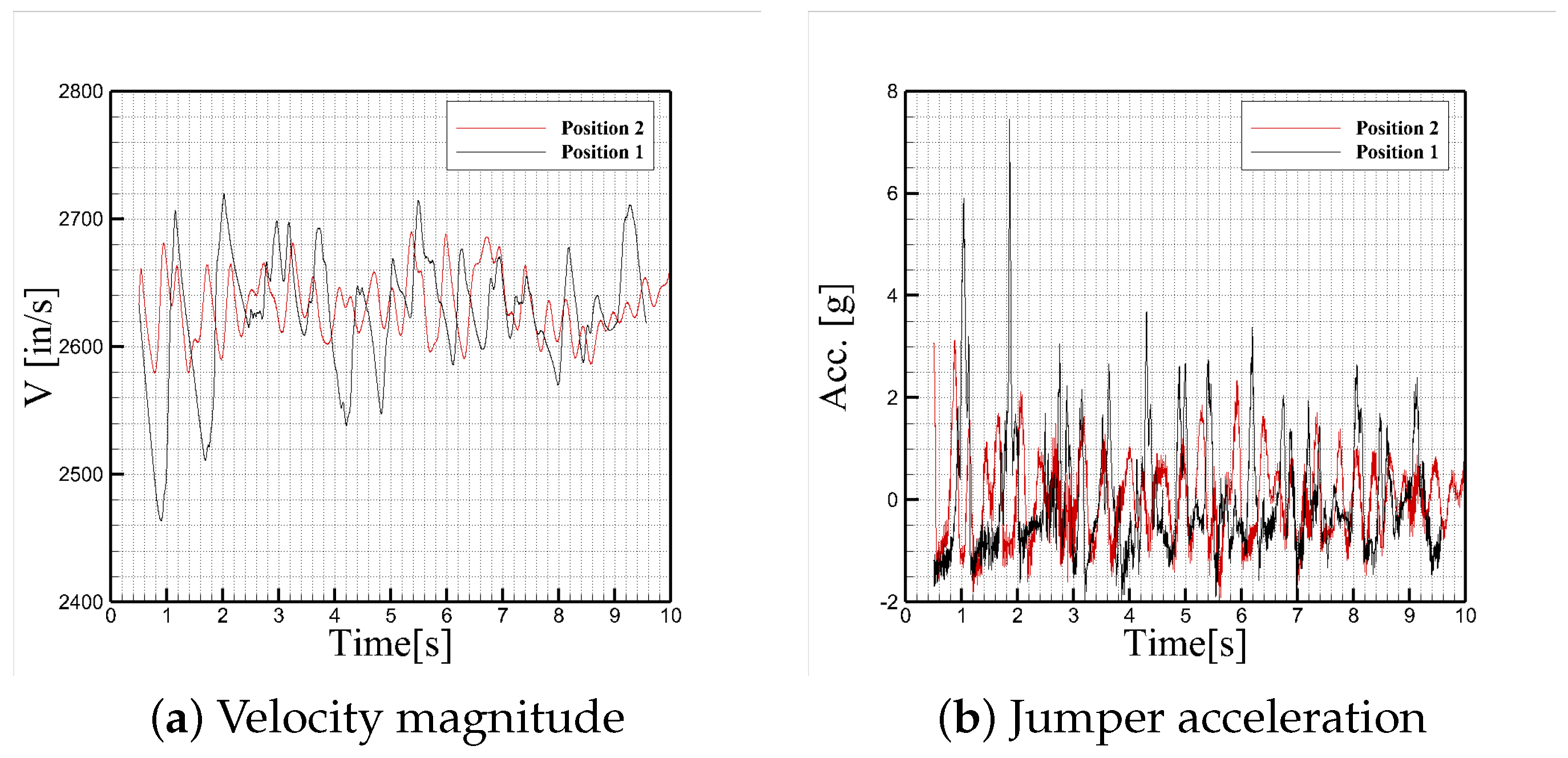

As the simulation progresses, the cable deforms in response to aerodynamic drag and jumper motion. The endpoints of the static line remain fixed—one attached to the aircraft and the other to the jumper’s main parachute deployment bag. Time histories of the jumper’s aerodynamic forces and moments, position relative to the initial location, velocity magnitude, acceleration, and cable strain and tension were extracted.

Figure 12 compares the jumper’s velocity and acceleration for both grid resolutions. The results indicate that jumper velocity increases when the static line becomes slack, while peak accelerations occur during directional changes when the line is taut. High drag forces are observed on the jumper’s body. The jumper exhibits continuous yaw rotation and a pitch-up response, drifting upward and toward the aircraft centerline; however, no contact with the aircraft structure was detected.

Based on these findings, the ExtraFine Grid was selected for all subsequent simulations, including those for the C-130J and A400M. Several issues identified in the initial runs were corrected: (1) the cable attachment point was incorrectly set at the ramp instead of the troop door, (2) the Young’s modulus used for the cable was unrealistically high (200 GPa), resulting in large transient accelerations, and (3) the jumper’s initial position relative to the aircraft introduced large initial disturbances. These issues are addressed in the following sections.

The next set of simulations focuses on the towed-jumper scenario from the C-130J aircraft, featuring spinning propellers and a 17-ft static line. The simulation setup is illustrated in

Figure 13. The static line is now attached at the midpoint of the troop door section, representing a more realistic deployment configuration. The jumper’s initial position was adjusted with specific displacements in the

x,

y, and

z directions to achieve an exact cable length of 17 ft.

An issue observed in early simulations of the static line configuration was that Kestrel version 12.9 did not support cable/body contact modeling. As a result, the static line was able to unrealistically pass through the C130J aircraft structure, as shown in

Figure 14 at simulation times

s and

s.

To address this, a Beta version of Kestrel was developed specifically for this project. This enhanced version includes cable-body contact modeling capabilities. Users can now specify the bodies that the cable may interact with, along with a user-defined contact distance. Furthermore, the updated model incorporates damping behavior within the cable to better capture dynamic effects during contact and motion. All subsequent simulations use the new Beta version.

6.2. Static Line Properties Sensitivity

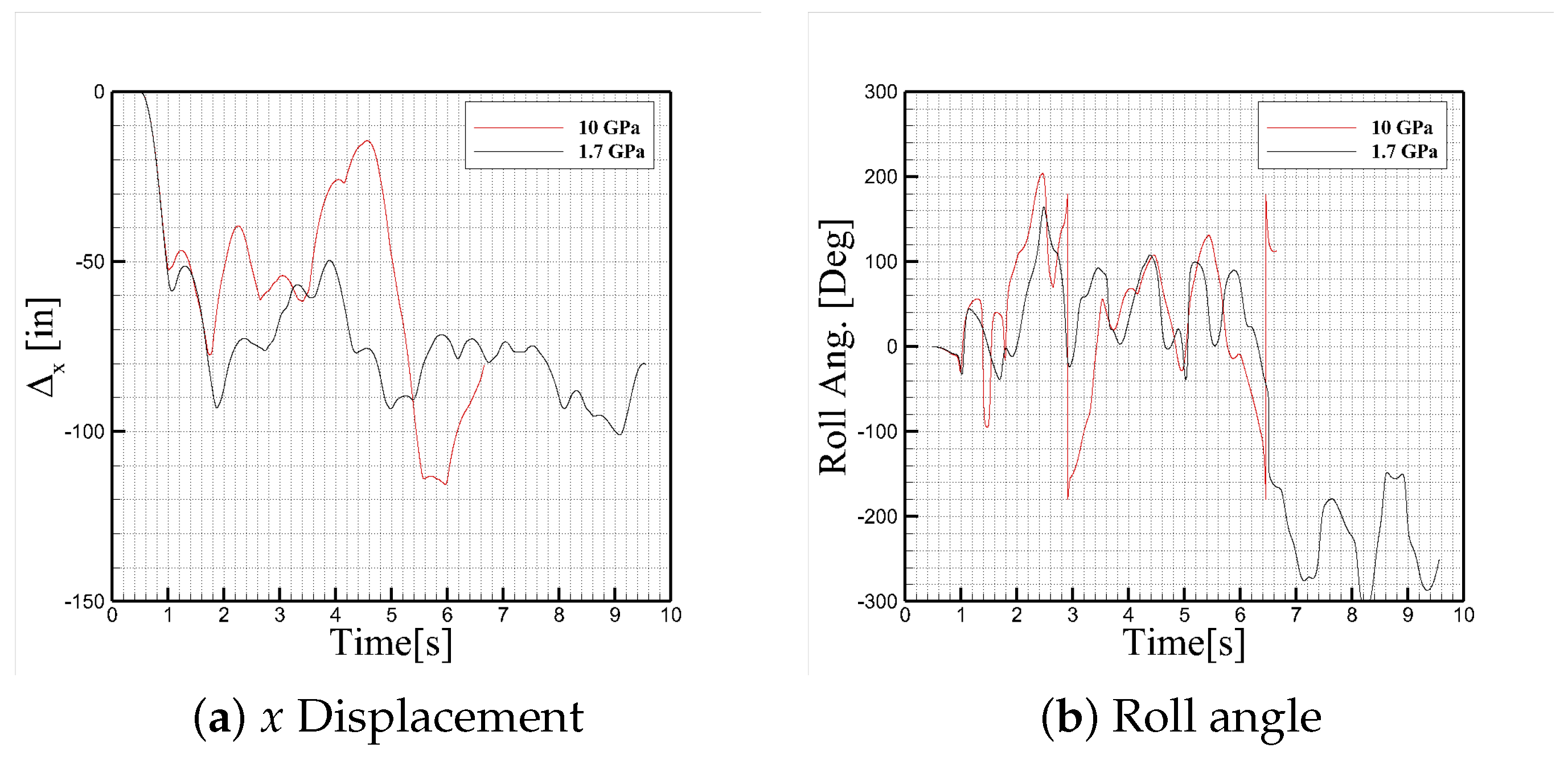

Two values of the cable’s Young’s modulus were tested to assess sensitivity to cable stiffness: 10 GPa and 1.7 GPa.

Figure 15 through

Figure 16 present simulation results for a 5th percentile jumper towed behind a C-130J aircraft with a 17-ft static line. The coordinate system follows the convention where positive

X points forward (nose of the aircraft), positive

Y is toward the right wing, and positive

Z points downward. Therefore, a negative displacement in

implies the jumper moves aft, a negative displacement in

implies the jumper moves toward the aircraft, and a positive displacement in

implies the jumper falls; in addition, a negative aerodynamic force

denotes drag.

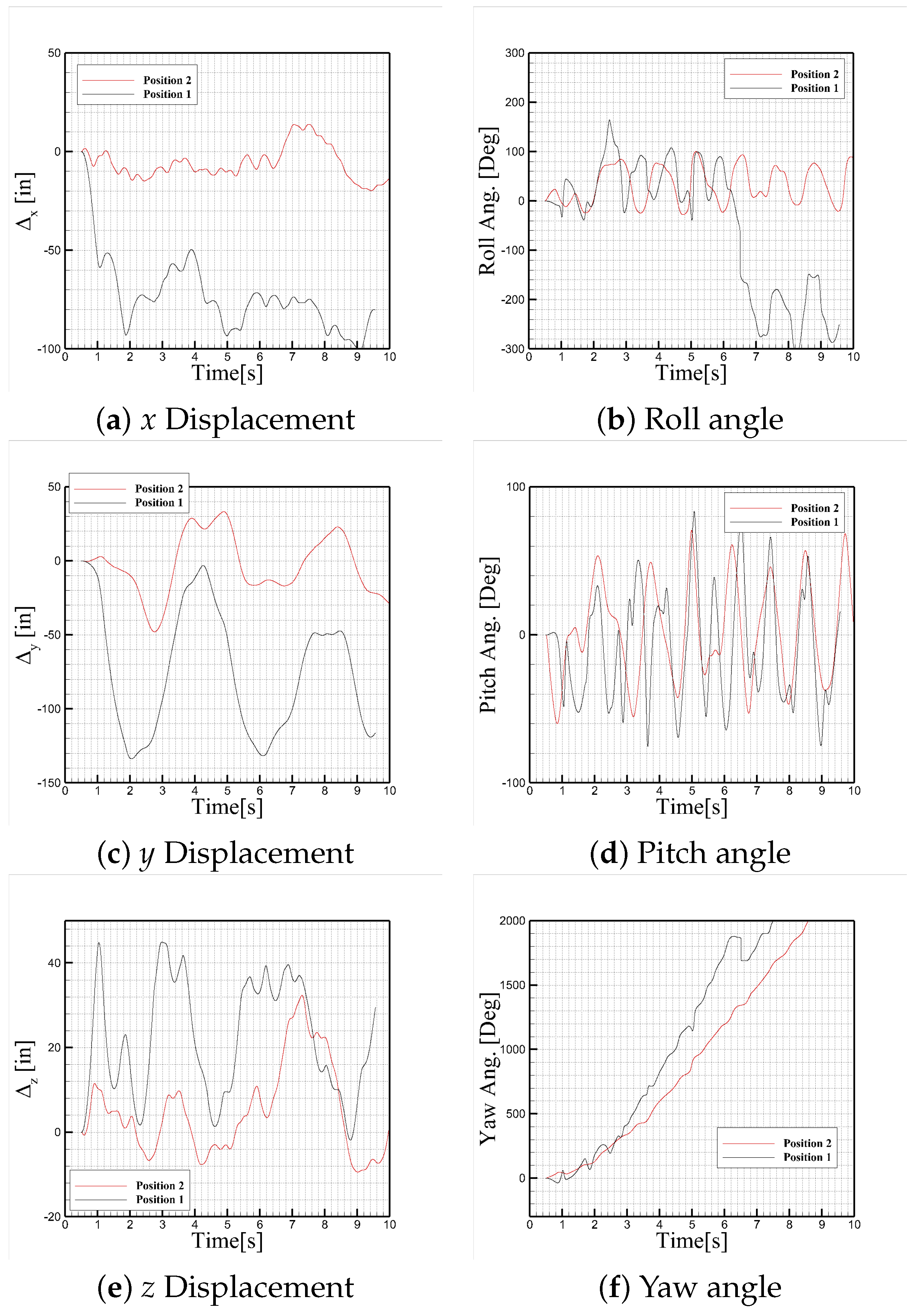

Figure 15 shows the time histories of jumper displacement components relative to the initial position. A rapid decrease in

is observed immediately after motion begins, indicating that the jumper is pulled aft due to slack removal and initial aerodynamic influence. The jumper’s

becomes more negative (i.e., upward motion) shortly afterward, likely due to lift and vertical acceleration from tension in the cable. The lateral displacement

grows more gradually, reflecting rightward drift caused by asymmetric wake and near-door flow disturbances. The trends in

,

, and

collectively capture the 3D trajectory of the jumper under complex aerodynamic and cable-induced forces.

In addition to translational kinematics and acceleration, the jumper’s rotational behavior is captured through time histories of Euler angles—pitch, yaw, and roll. The simulation results indicate that the jumper undergoes a continuous yawing motion, evidenced by a steady increase or oscillation in the yaw angle over time. This behavior suggests that asymmetric aerodynamic loading, likely caused by unsteady wake structures near the troop door or an off-center mass distribution, induces persistent torque about the vertical axis.

The pitch angle exhibits moderate oscillations, indicating dynamic coupling between vertical displacement and pitching moment, while the roll angle remains relatively small or bounded, implying limited rolling tendency in this particular configuration. The yaw dominance aligns with the flow asymmetry often encountered near open troop doors and confirms the necessity of high-fidelity modeling to capture directional instabilities in jumper trajectories.

The current Catenary model implementation in Kestrel does not include torque damping mechanism to resist jumper rotations. As a result, once initiated, yaw motion can accumulate unchecked, further emphasizing the importance of including rotational damping in future versions of the model to prevent unrealistic or exaggerated angular excursions.

Persistent yawing is of particular concern in towed jumper scenarios, as it may exacerbate cable entanglement risks or misalign jumper orientation prior to parachute deployment. These results highlight the importance of both accurate geometric modeling of the jumper and detailed resolution of the aircraft wake to predict such rotational instabilities reliably.

Figure 17 compares jumper acceleration for simulations using different values of Young’s modulus for the static line. The results show that a higher stiffness (e.g., 10 GPa) leads to more abrupt and larger acceleration spikes upon cable extension, indicating less damping and higher instantaneous load transfer to the jumper. In contrast, a lower stiffness (e.g., 1.7 GPa) produces smoother, less severe accelerations. These findings highlight the critical role of cable material properties in modulating the severity of towed-jumper dynamics. A stiffer cable may limit jumper motion but can increase the risk of injury due to sudden high-magnitude accelerations.

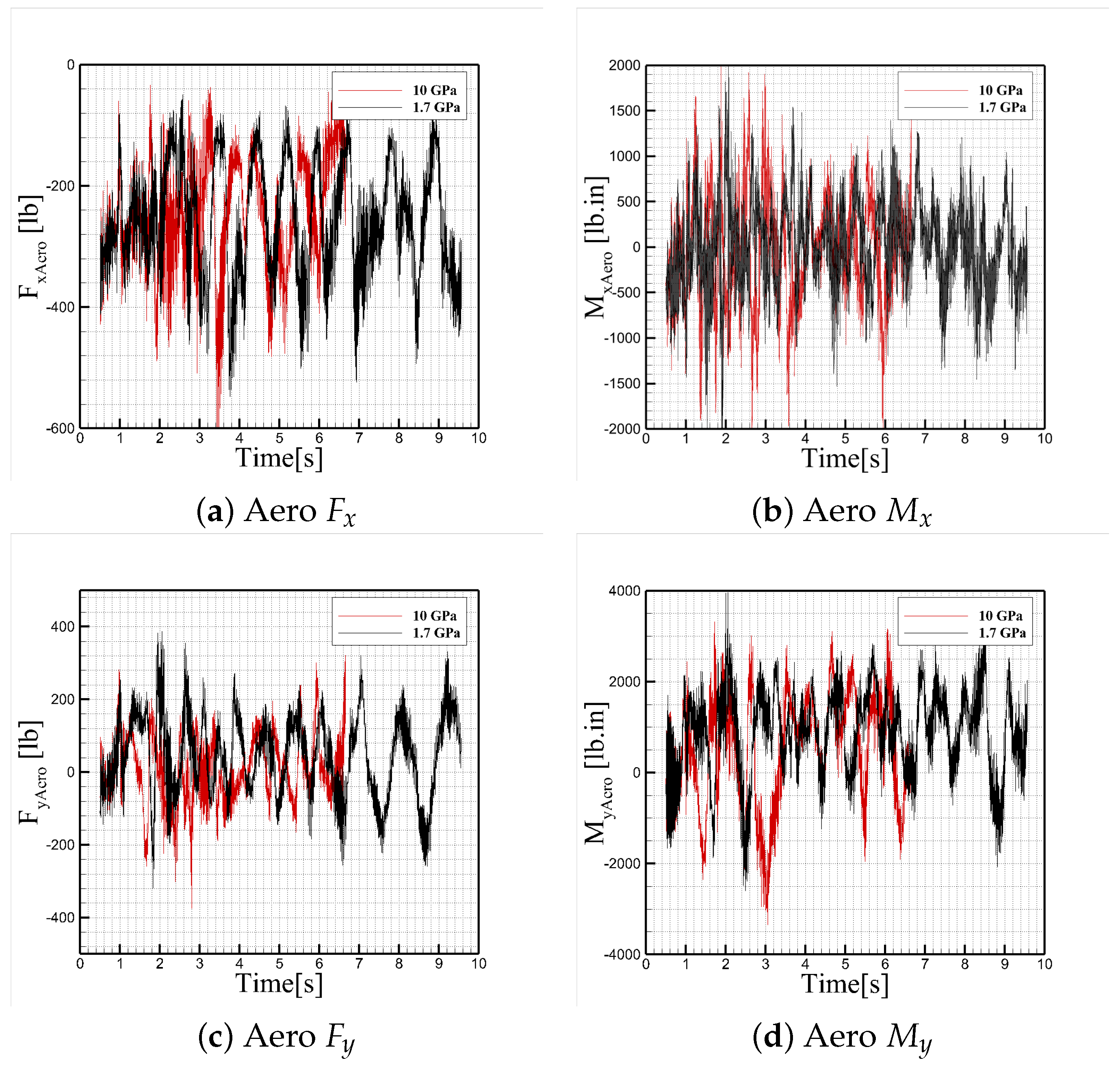

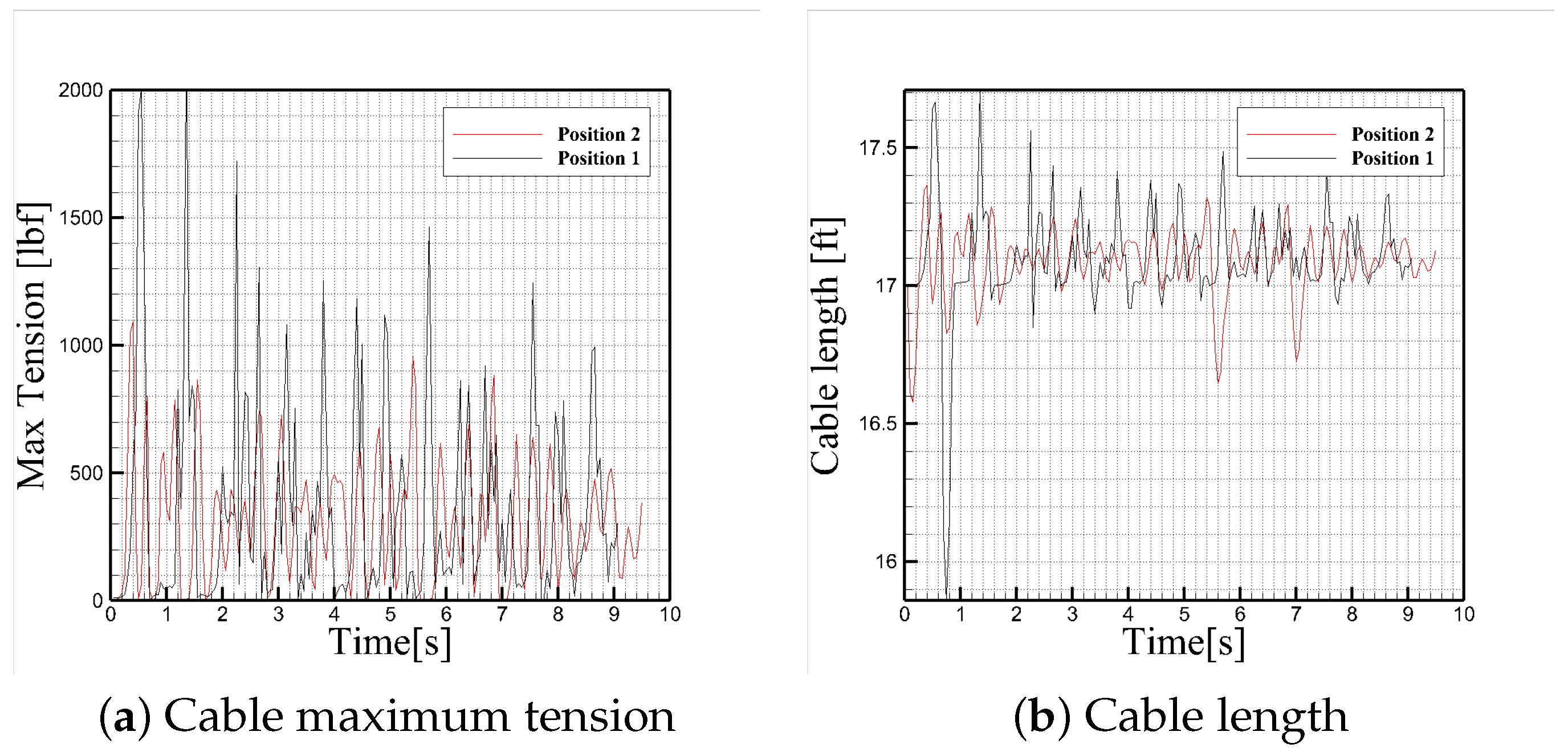

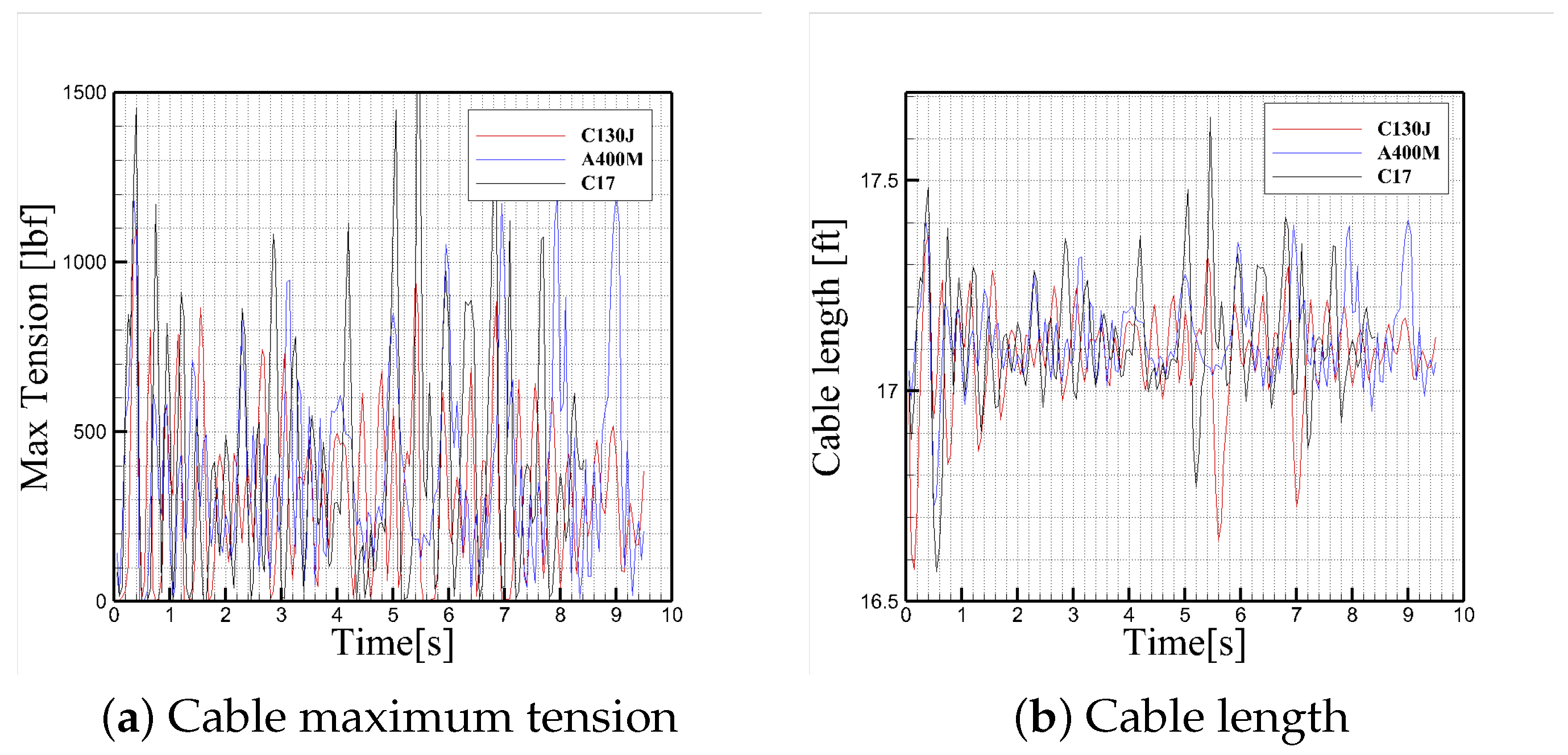

In

Figure 18, the cable tension sharply rises as the static line becomes taut following initial jumper displacement. The peak tension corresponds closely to the point of maximum negative

, marking the transition from slack to fully stretched cable. Once taut, the cable length stabilizes around its design value of 17 ft. This figure clearly illustrates the dynamic coupling between jumper aft motion and the rapid buildup of static line tension. These transient peaks represent critical loading conditions for both the jumper and attachment hardware.

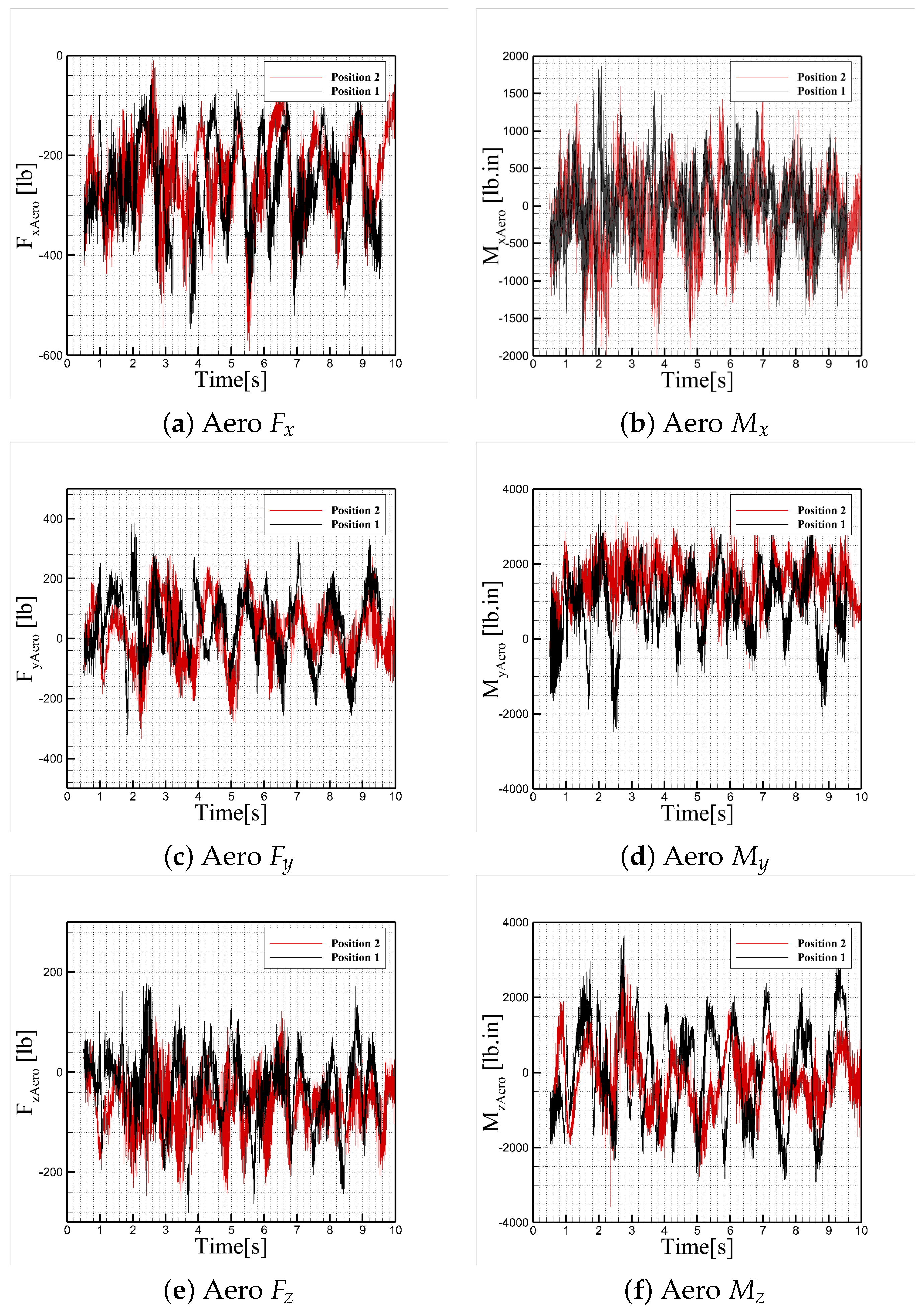

Figure 16 presents the aerodynamic force components acting on the jumper. The longitudinal force

remains negative throughout the simulation, corresponding to aerodynamic drag. Pronounced spikes in drag occur in tandem with sharp changes in jumper motion, particularly during deceleration phases, when the cable becomes taut. The vertical force

and lateral force

exhibit significant fluctuations, driven by unsteady flow in the wake of the aircraft and the jumper’s changing orientation. These aerodynamic loads play a major role in shaping jumper kinematics and structural response.

Together, these figures demonstrate the importance of modeling both aerodynamic and cable dynamics in evaluating jumper safety during static line operations. The correlations between jumper motion, cable tension, and aerodynamic forces reveal how changes in jumper position directly influence dynamic loading. Furthermore, the selection of cable material properties, especially Young’s modulus, has a significant impact on acceleration levels experienced by the jumper, and thus on operational safety and equipment design.

6.3. Influence of Jumper Initial Position

Figure 19 compares two initial jumper positions for a C-130J simulation with a 17-ft static line. Both positions maintain the same cable length and stiffness (1.7 GPa), but differ in their spatial configuration. Position 1 corresponds to the earlier configuration in which the jumper was placed at an equal displacement from the attach point in all directions (

). This placement results in the cable initially being misaligned with the local flow direction, leading to visible aerodynamic deflection. The cable bows outward due to drag forces acting on it, indicating significant initial loads and an unrealistic tension orientation. In contrast, Position 2 aligns the cable closer to the streamline direction expected in a real jumper exit path. This improved configuration significantly reduces cable deflection at startup, indicating a more physical initial condition with minimal artificial loading.

In the previous setup (Position 1), the initial jumper displacement was defined such that , creating a symmetric vector consistent with the 17-ft cable length. However, this configuration placed the jumper farther away laterally and vertically from the aircraft, introducing artificial motion early in the simulation as the jumper quickly adjusted to find a dynamically stable position.

In the Position 2, the jumper is placed further aft (larger negative ), closer to the aircraft body (smaller ), and slightly lower (less negative ). This revised position reflects a more physical jumper release path and avoids the need for significant early adjustment in the simulation.

Figure 20 confirms that the jumper with the new initial position has smoother velocity profiles and lower peaks in translational accelerations, especially in the longitudinal and lateral directions.

Figure 21 confirms that the cable tension and overall

strain energy remain lower and more consistent throughout the simulation when the new jumper position is used.

As shown in

Figure 22, the jumper’s translational motion—especially in the

and

directions—exhibits substantially fewer fluctuations for the new position, indicating improved initial stability.

Figure 23 shows that the aerodynamic forces are also more stable in the new setup, with drag and side force showing reduced amplitude in their time histories. This correlates with less abrupt cable re-tensioning events.

These results emphasize the importance of carefully selecting jumper initial conditions for physically representative modeling. The refined position minimizes nonphysical transients, better reflects realistic jumper exit trajectories, and reduces both structural loading and numerical oscillations in early simulation phases.

6.4. Aircraft Configuration Effects

Next results are focused on the effects of aircraft on the jumper motion and cable dynamics. The same 5th percentile jumper towed by three different aircraft platforms: the C-130J with spinning propellers, the A400M with propellers modeled as actuator disks, and the C-17 with fully modeled engine inlet and exhaust flow. In all cases, a 17-ft static line was used, with a Young’s modulus of 1.7 GPa. The static line was connected between a fixed point on the troop door and the jumper’s parachute bag. The jumper was initialized using the refined Position 2 in all three cases, ensuring a realistic and comparable starting condition across simulations. The jumper with all aircraft is shown in

Figure 24.

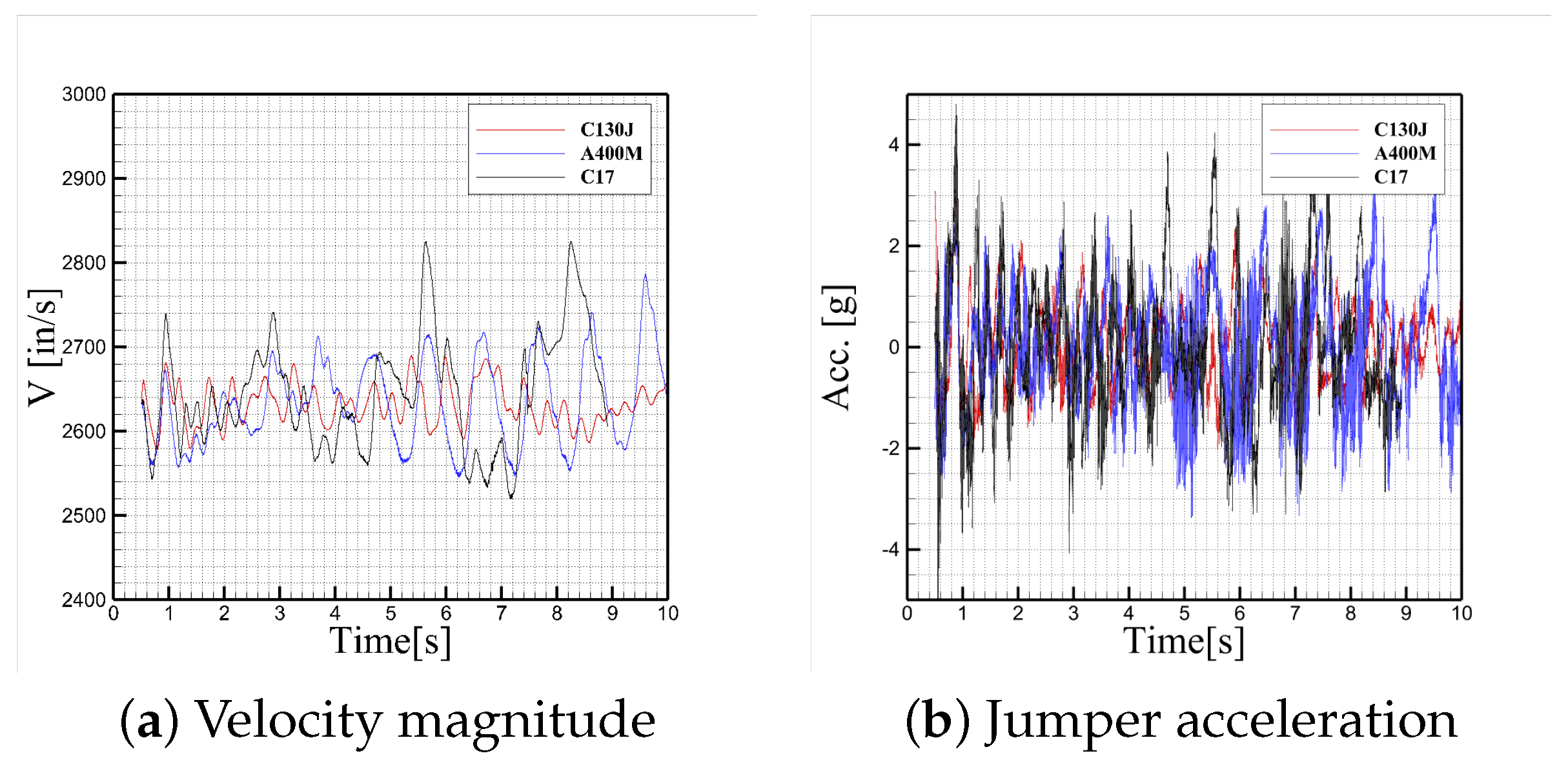

Figure 25 through

Figure 26 compare the dynamic response of the jumpers.

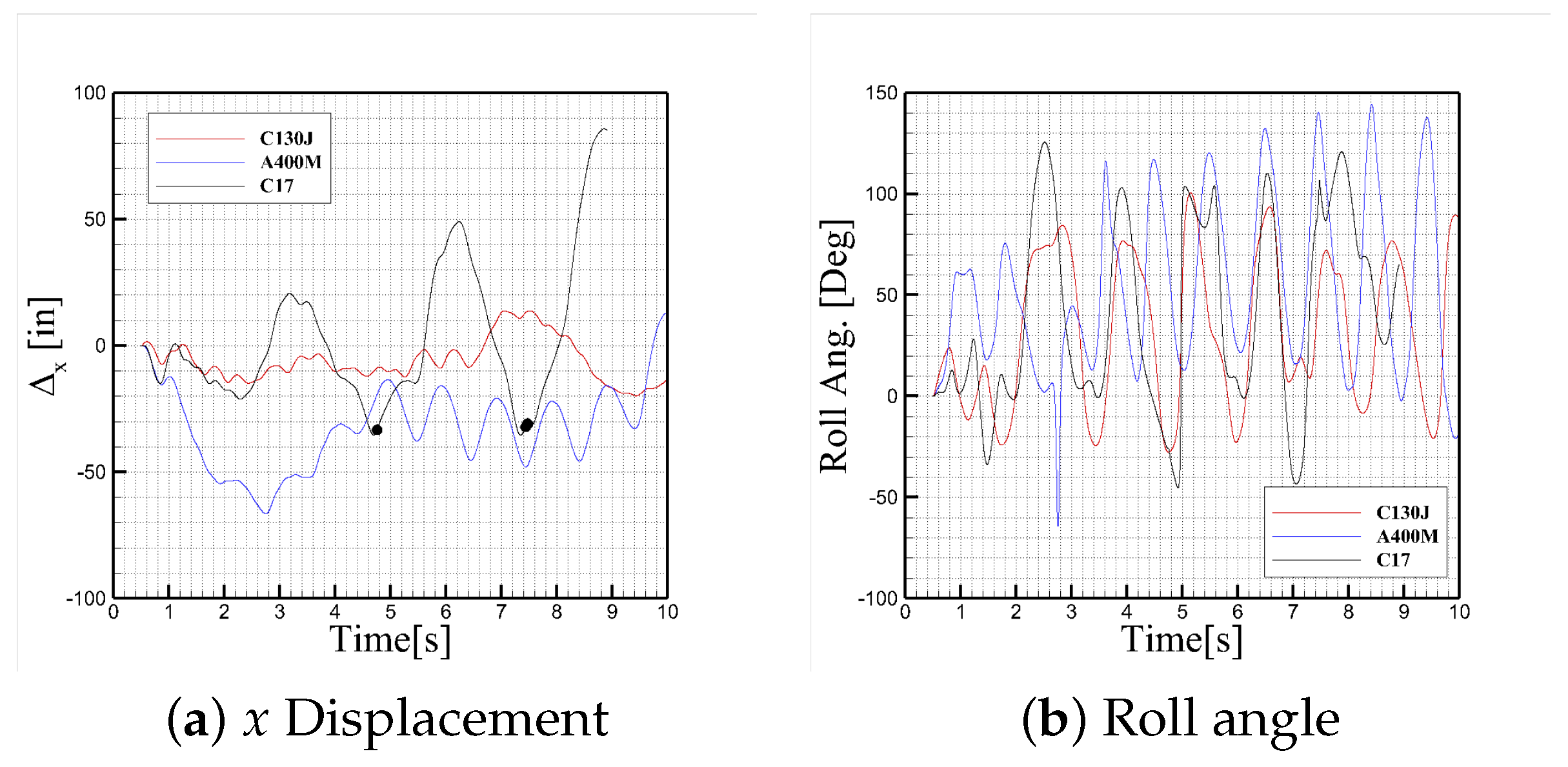

Figure 26 presents the translational and rotational motion histories of a 5th percentile jumper towed by three different aircraft configurations—C-17, C-130J, and A400M—each using a 17-ft static line with a Young’s modulus of 1.7 GPa. Among the three platforms, only the C-17 case exhibited jumper contact with the aircraft, as indicated by circular markers in the translational displacement plots (subfigures (a), (c), and (e)). Four distinct contact instances were recorded for the C-17 configuration, with the final three occurring in rapid succession, suggesting repeated impacts during a short time window when the jumper remained in close proximity to the aircraft fuselage. In addition,

Figure 27 compares cable maximum tension and cable lengths for three different simulated aircraft. The cable attached to the towed jumper in proximity of C-17 shows higher tensions and more cable length variations compared with cables used in other aircraft.

Notably, these contact events coincide with simultaneous negative values of both lateral () and vertical () displacements. A negative indicates that the jumper moved laterally toward the aircraft body, rather than away from it, while a negative signifies upward motion toward the fuselage. This combined motion pattern suggests that the jumper was pulled inward and upward by a complex interplay of cable tension and asymmetric aerodynamic forces, ultimately leading to direct collisions with the airframe.

6.5. Contact Events and Safety Implications

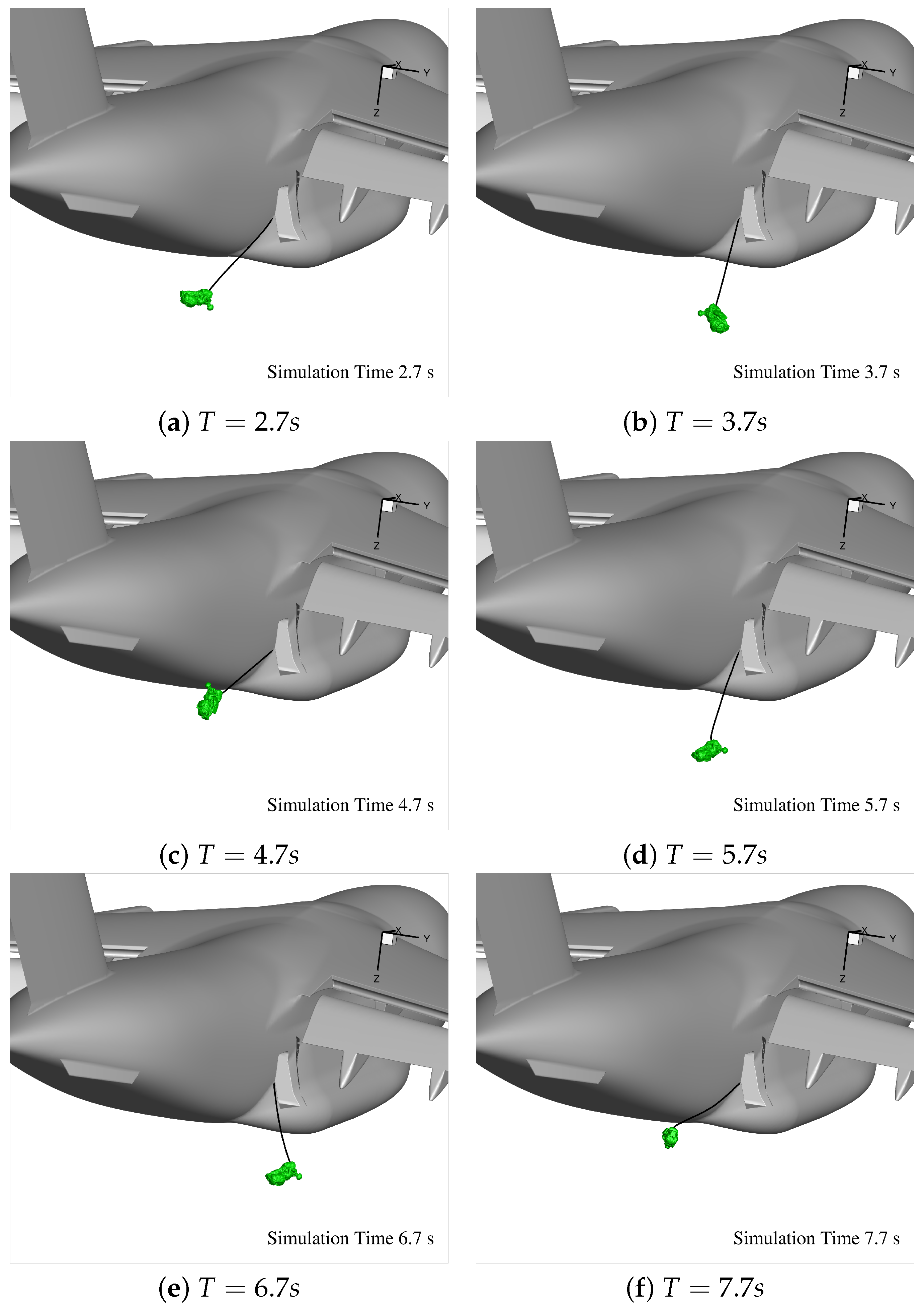

In more detail,

Figure 28 provides a time sequence of visual snapshots depicting the dynamic behavior of a towed jumper attached to the C-17 aircraft via a 17-ft static line. The images are captured at simulation times

,

,

,

,

, and

s. These frames illustrate the jumper’s evolving posture and spatial relationship with the aircraft as influenced by near-field aerodynamics, cable forces, and body dynamics. Notably, jumper-aircraft contact is clearly visible at

s and again at

s. During these time instants, the jumper drifts laterally and vertically toward the fuselage. These collision events highlight moments when the jumper is drawn inward and upward—likely driven by a combination of cable retensioning, unsteady aerodynamic loading, and insufficient torque damping.

Across all three aircraft, the general trends in displacement and orientation are consistent, with similar amplitudes and directional response patterns. However, a key distinction is observed in the yaw angle history (

Figure 26f), where the A400M case exhibits significantly reduced yaw rotation compared to the C-130J and C-17 cases. This difference may stem from two primary factors. First, the C-130J and C-17 configurations used in this study include large flap deflections representative of operational airdrop conditions, which can generate strong trailing vortices and asymmetric flow structures near the troop door. In contrast, the A400M model in these simulations did not include flap deflection, resulting in a more symmetric and less rotationally biased flow field. Second, the A400M simulations used a simplified actuator disk model to represent propeller effects, which does not resolve blade-induced swirl and slipstream dynamics. This modeling simplification may have further reduced yaw-inducing aerodynamic moments on the jumper.

In addition, as shown in

Figure 26a,c,e, the jumper towed behind the C-17 exhibits oscillatory motion in all three translational directions—longitudinal (

), lateral (

), and vertical (

). The displacement time histories reveal that the jumper’s position alternates between positive and negative values, indicating back-and-forth motion relative to the initial location. This behavior reflects a dynamic response driven by the combined effects of the unsteady aerodynamic wake, gravity, and tension forces from the viscoelastic static line. The oscillations are especially significant in the C-17 case, which is the only configuration to show multiple contact instances with the aircraft fuselage. The continued sign changes in the displacement components confirm that the jumper does not settle into a stable equilibrium, but instead remains in a dynamically active, oscillatory state throughout the simulation.

These comparisons highlight the influence of aircraft-specific flow features—such as propeller slipstream structure, flap deflection, and engine wake effects on jumper.

7. Conclusions

This study presented a high-fidelity computational framework for simulating towed jumper dynamics during static line airborne operations using the CREATETM-AV/Kestrel flow solver. Key features of the modeling approach include a flexible catenary cable model with adjustable stiffness, damping in tension, and an initial capability for contact force detection between the jumper and aircraft. The simulation environment resolves aircraft near-field aerodynamics using static line attachments and jumper mass properties tailored to percentile-based anthropometric data.

Comparative simulations were performed across multiple aircraft configurations, including the C-130J with spinning propellers, the A400M with actuator disk-modeled propellers, and the C-17 with resolved engine inlet and exhaust flows. In all cases, a consistent 5th percentile jumper and a 17-ft static line with 1.7 GPa Young’s modulus were used, with jumper initial conditions aligned to a physically realistic exit trajectory (Position 2).

The results confirm that jumper motion and cable tension dynamics are highly sensitive to both the jumper’s initial position and the flowfield fidelity of the aircraft. Specifically, positioning the jumper along a realistic path (Position 2) significantly reduces unphysical transients, oscillatory accelerations, and cable re-tensioning events. Among aircraft cases, C-17 simulations showed four instances of jumper contact, while C-130J and A400M exhibited no contact. Interestingly, yaw motion was significantly damped in the A400M simulation, likely due to the absence of flap-induced vortices and the use of actuator disk propeller modeling—highlighting the role of both geometry and propulsion fidelity in predicting rotational behavior.

Overall, the study demonstrates the capability of Kestrel to capture detailed aerodynamic-structural coupling during parachute deployment scenarios and to identify platform-specific risks, such as jumper-aircraft contact and excessive body rotation. The modeling framework serves as a valuable tool for operational planning, equipment design, and validation of reduced-order models. Future work will expand contact modeling capabilities by incorporating torque damping and advanced collision detection algorithms, and will include systematic validation against flight tests and wind tunnel data.