1. Introduction

Local flood risk management depends on the provision of appropriate data and information to multiple stakeholders that need to take preventative and recovery actions [

1]. Data and information may be delivered through a variety of platforms and different sources which inform actors with the expectation that they will act on the information and be better prepared [

2]. Two commonly supplied information types are emergency warnings and risk awareness [

3]. These have distinct purposes as appropriate for their situation in different phases of the disaster cycle, response and preparedness, respectively. The effectiveness of these two information types in disaster risk reduction is highly interdependent as awareness is a pre-requisite for action on receipt of warning information. More importantly, knowledge of appropriate risk reduction strategies must accompany awareness for the most appropriate actions to be taken [

4].

Furthermore, different stakeholders require data at varying levels of detail, and different temporal- and spatial scales-depending on their role in risk reduction. Each actor perceives their need differently and may be influenced by their risk perception, preferred risk reduction strategy and expectation of quality and timeliness of available data and information. In many societies, those most vulnerable to climate hazards, such as flooding, are the urban poor particularly in developing countries [

5]. In the context of a lack of formal or technical information and limited capacity, households and businesses in developing countries are disproportionately affected by flooding [

6]. This means that new approaches to climate services providing flood risk information, involving data across scales and ensuring appropriate communication to end-users (households and businesses), are required if city dwellers in developing countries are to be made more resilient. To support these flood risk management goals, the research considers a broader conceptualisation of flood risk information that encompasses not just the potential national scale databases, but also those of how information is provided at the local scale.

Local communities will need more than just good information to adapt to flooding and build resilience. For households and businesses to get the most out of emergency and awareness information, there is the need to promote information provision in a manner that will be understandable and used by the recipient. The problem often is not of access, but of other factors such as the nature or the source of the information [

7]. Aspects of trust in organisations and individuals that supply information can also be instrumental in delivering effective warnings and in generating preparedness [

7,

8,

9,

10]. However, trust is a complex issue, trust in risk management authorities may encourage some preparedness activities (evacuation) while discouraging others (property level resilience). In addition, trust is a highly individual and subjective phenomenon [

11], unlikely to be uniform across different recipients of the same information from the same source.

While emergency warning and risk awareness information at the local scale, such as household and businesses, may have considerable impacts on risk reduction, it is often unclear how to address the need and importance of intermediaries in collating data and communicating information. Traditionally, disaster information is often seen as from the government and transmitted through the mainstream media. However, today with the multiplicity of actors in flood management and improvement in information technology other providers and sources are emerging. Communities may rely on both formal sources such as government departments and informal sources such as neighbours. While some attention has been paid to flood risk communication internationally, there are very few studies in Africa [

9].

Studies of flood management in the Sub-Saharan Africa region have highlighted the lack of, or paucity of relevant data that may be needed for example to identify risk factors [

12,

13]. Most of the countries do not have national databases [

14], although data exist for major disasters in global databases, such as EM-DAT from the Centre of Research on Epidemiology of Disasters and UNISDR DesInventar databases. According to Osuteye et al. [

12], the data on sub-Saharan Africa is too sparse to understand or make any reasonable connection or build trends to support flood management. Such information, if available, would assist decision-makers to make more informed and location-specific choices about flood risk management. It therefore becomes instructive to understand the opportunities and challenges and how stakeholders in these societies are responding to calls to enhance flood management data, information and knowledge.

More specifically, in Nigeria there is currently no database that organises key information on flooding either at a national or sub-national level. There are only records of selected recent floods which are by no means complete [

15]. In Nigeria, the lack of information and awareness is noted and general calls for improvement in awareness are made [

16]. Studies also call for improved large data sets needed for information in terms of modelling and improvements in reliability and integration [

17] for decision making at the national or regional scale. While these are important aspects of risk management, there is also a need to consider risk communication if the information is to be used effectively.

In the Nigerian context, specific knowledge of the requirements of stakeholders and communities is lacking. Little scientific attention has been given to understand how households and businesses acquire climate hazard information and the media they use. The majority of studies of climate risk are based on serving the needs of rural farming communities (see for example References [

18,

19]). For Lagos, a body of research has documented community, household and individual level flood management strategies (see Reference [

17,

20]). However, no study has considered a wide range of stakeholders simultaneously.

Such an understanding could inform a more targeted strategy for flood emergency warning and risk awareness and thereby foster planning and learning for enhanced resilience. Recognising that information-source organisations are not necessarily the information providers to the wider stakeholder community, decision makers can use such an understanding to identify appropriate sources for dissemination. Moreover, understanding any intra-group peculiarities within apparently homogenous groups in the communication of flood risk information is immensely valuable.

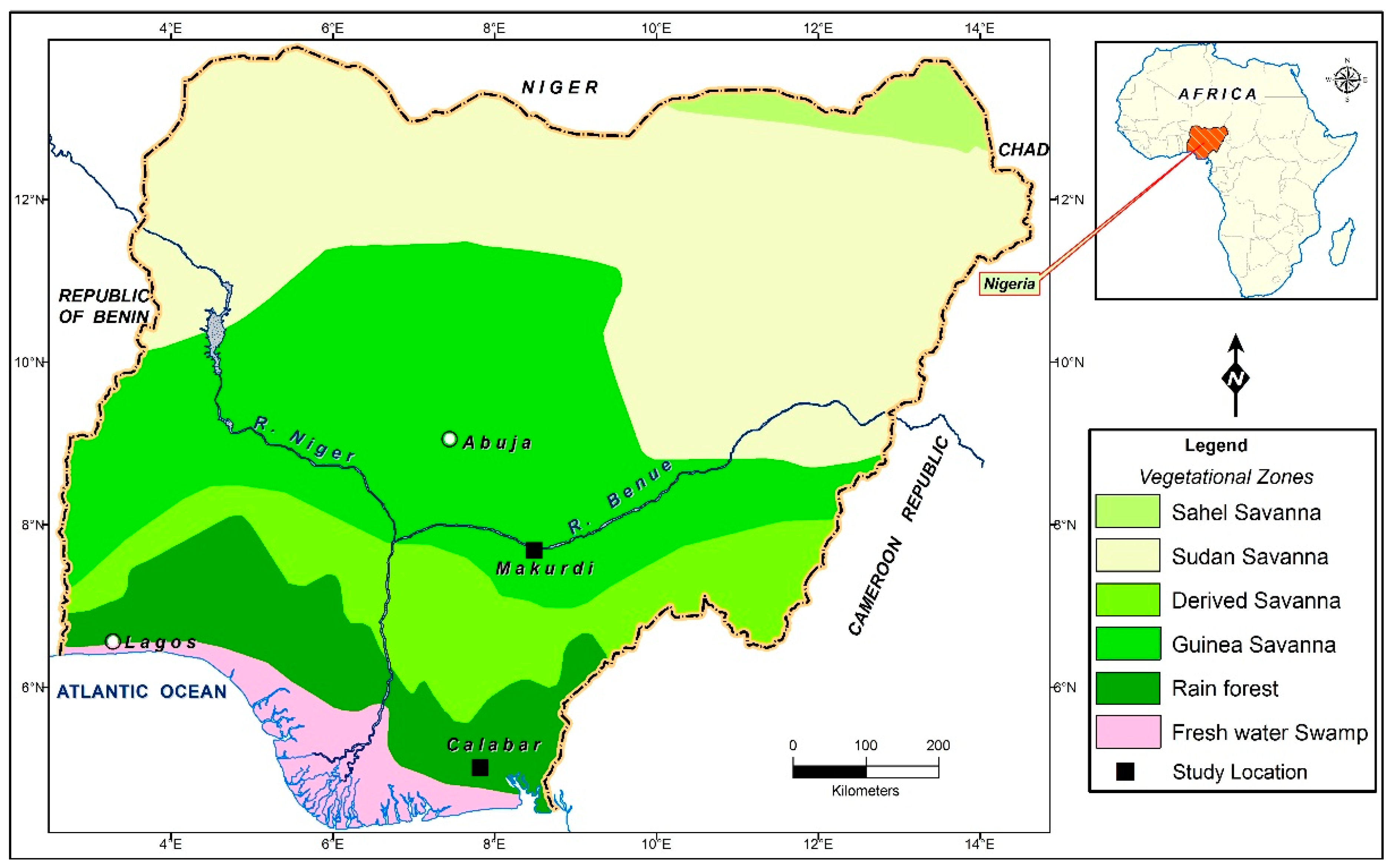

Given that there is very little available research on risk information for Nigerian urban populations outside of Lagos, and none that takes a multi-stakeholder view in a given city, the role of information in response and adaptation was explored in two smaller Nigerian cities as part of a wider study in climate resilience. The research sought insight on the perceived adequacy and usefulness of available data and information and the communication of information between stakeholders including the preferences of communities at risk. It also examined the level of provision of climate hazard information, either as warning or about what to do in the case of climate hazard. Data was collected from stakeholders, households and small businesses to shed light on the differences between the different actors. Attention was given to (i) understanding sources through which households and businesses receive information, (ii) assessing the level of trust of these sources and (iii) understanding local community’s preferred medium to receive climate hazard information.

3. Results

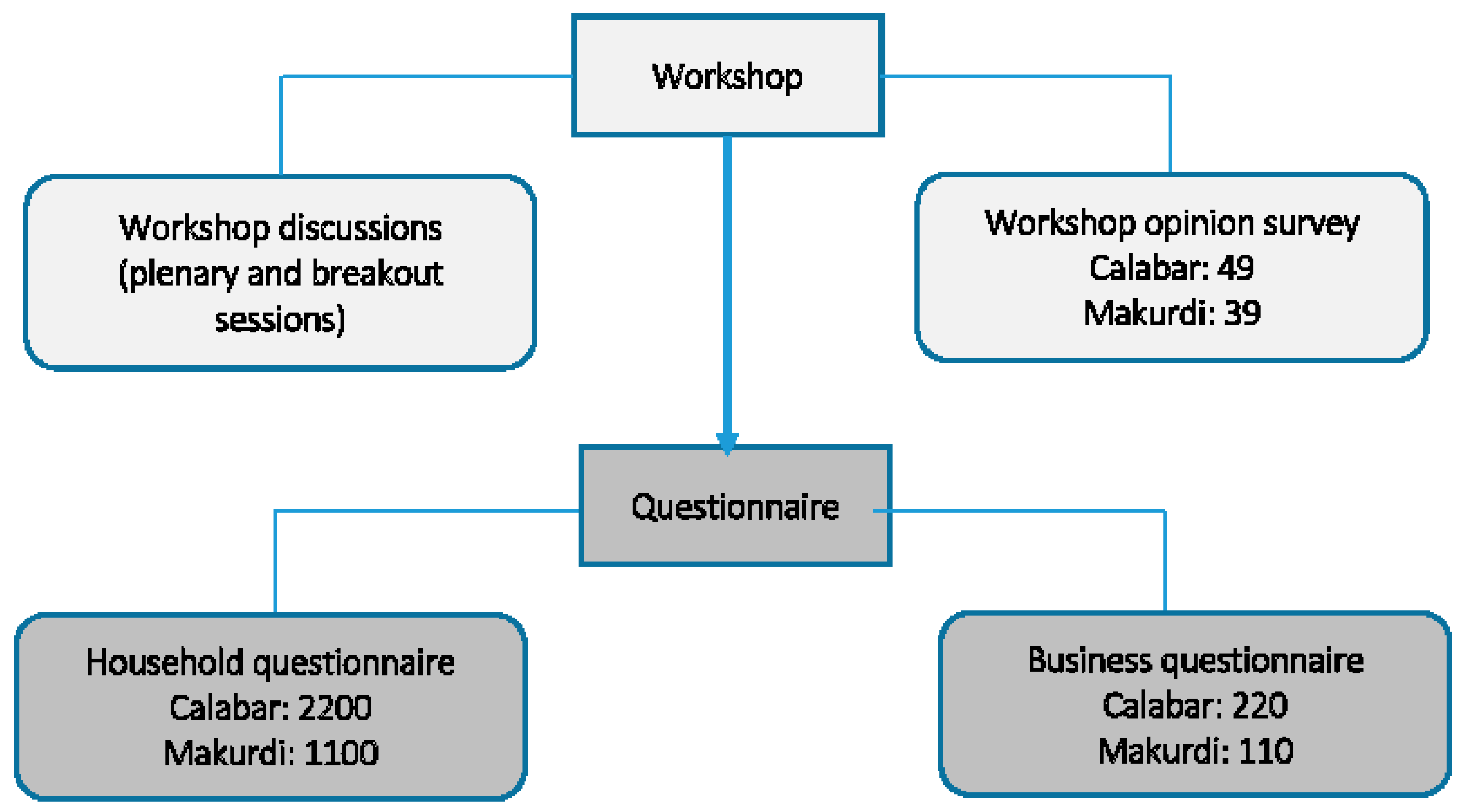

The results of the workshop discussions, opinion survey and household and business questionnaire are presented below under five themes related to the study objectives.

3.1. Information for Better Hazard Management and Governance

Stakeholders at the workshops agreed in discussion that information is critical for better management of hazards and perceived the need for more data and information on climate and weather (temperature, rainfall and wind), and physical and environmental conditions (river hydrology, land degradation, soils, land use) to inform hazard mapping. Furthermore, they recognised the need to combine this environmental information with data on socio-economic and preparedness data. There are national agencies that hold national and local climate data, and participants felt confident that this information could be sourced locally, although very few examples of actual data access and use were cited either in the discussion or in the opinion survey; the availability of detailed environmental, social and preparedness data to create hazard and risk maps was seen as more problematic with nearly 80% of respondents calling for more information in the opinion survey. Projections of the impact of changing climates and urban growth are considered as not available with further information on climate uncertainties called for by 90% of respondents.

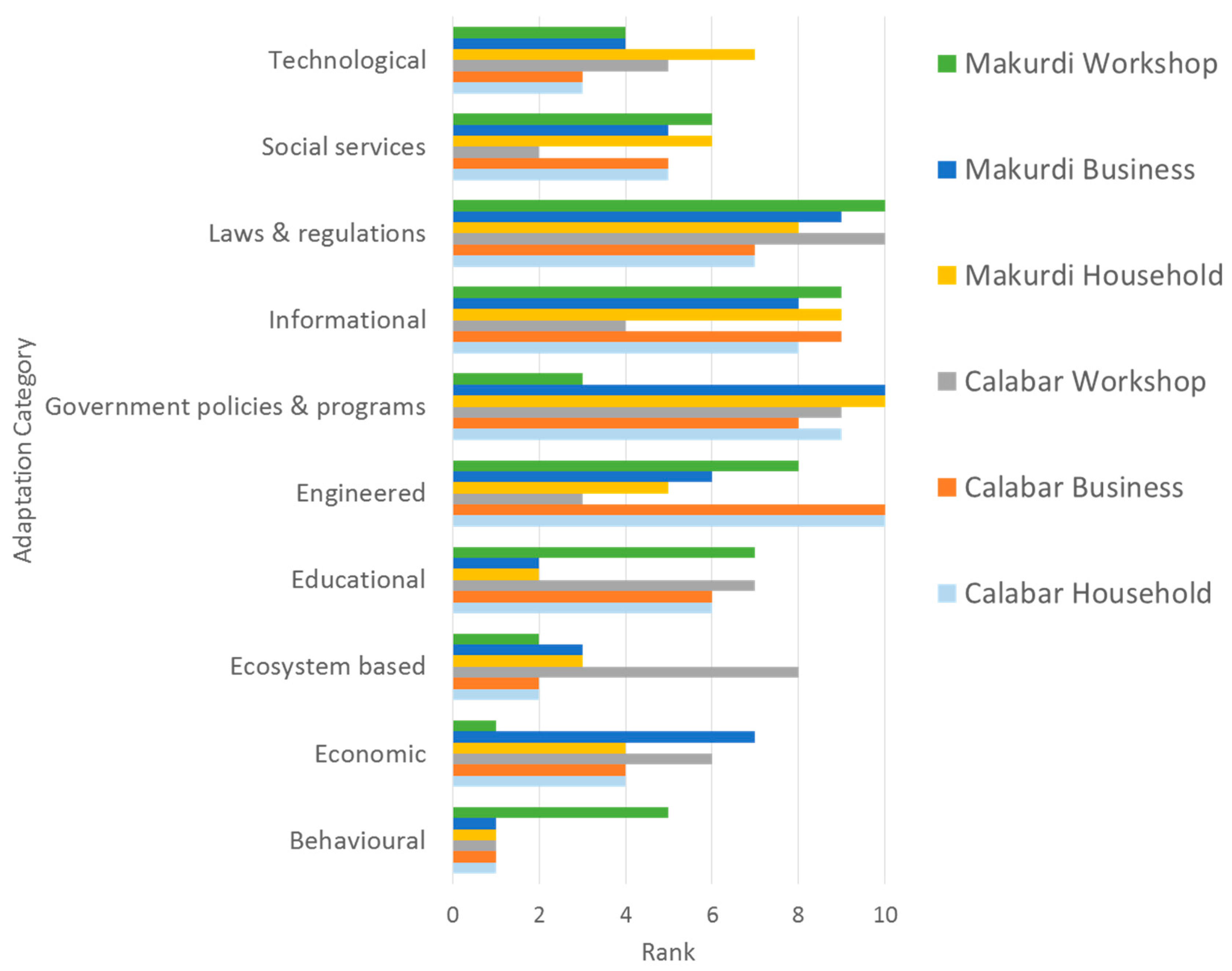

Aside from data requirements, the skills required to provide information and knowledge from the available data were perceived to be lacking in relevant agencies. Stakeholders recognised in the discussion that adaptation strategies such as laws and regulations, informational approaches and even engineered approaches require detailed hazard and vulnerability information. Through the opinion survey, they also ranked these approaches as important as shown in

Figure 3. Individuals were confident in their own ability to manage data and information in their current prescribed roles with almost 60% of the opinion survey respondents having high confidence in understanding probabilities and over 80% understanding risk assessment in both cities. However, more training and greater expertise was called for in general to support adaptation including climate change mitigation and adaptation; GIS skills and impact assessment; and understanding the links between waste management, drainage and hazards, emergency management and response, forecast and early warning, environmental communication and enlightenment, United Nations frameworks, and solar and clean energy technology.

The paucity of data and skills is seen to be compounded by the lack of synergy between departments within government and between government and other agencies and individuals. In the Makurdi opinion survey, only 17% and in the Calabar opinion survey, only 25% of respondents felt there was adequate exchange and interaction among stakeholders. Participants felt that available data and skills are not always exploited or sufficiently joined up. For example, the states do not have ongoing contact with the relevant agency, the National Space Research and Development Agency (NSRDA), a Federal agency responsible for Nigeria satellites and warehouse for the nation’s geospatial data useful for managing disaster preparedness and response [

27]. Additionally, the planning review committees are perceived by some as lacking in technical planning expertise and being overly political. Furthermore, communities are rarely consulted. Therefore, both experts and lay voices outside the existing relevant governance structures may be ignored.

Households and businesses also ranked adaptation categories during the questionnaire survey. These responses reinforced the relative importance of information. While there are differences as to the main approach to be used, informational approaches are generally highly ranked by households and businesses. Laws and regulations and government policies (highly dependent on climate information for planning and enforcement) are also highly ranked (

Figure 3).

Given the perceptions of stakeholders that more data and information is required to properly plan, manage, adapt and respond to hazards in Nigeria (as expressed in the workshop discussions and opinion survey), workshop participants in discussion suggested that, at the moment, there is little in the way of educating households and businesses on ways to adapt to climate-related hazards. They believe people are resorting to self-help which may be even more damaging and ineffective. The next section explores the provision of information in more detail from the perspective of households and communities.

3.2. Receipt of Information on Hazards and Adaptation for Communities (Households and Businesses)

In terms of the information supply for communities in Calabar and Makurdi, the questionnaires revealed that receiving information was not a universal experience. Households and businesses were asked to report whether they had received climate hazard information in the last 12 months. Less than 60% reported receiving information in any community. There was also significant variability observed between the cities and between the different communities within them.

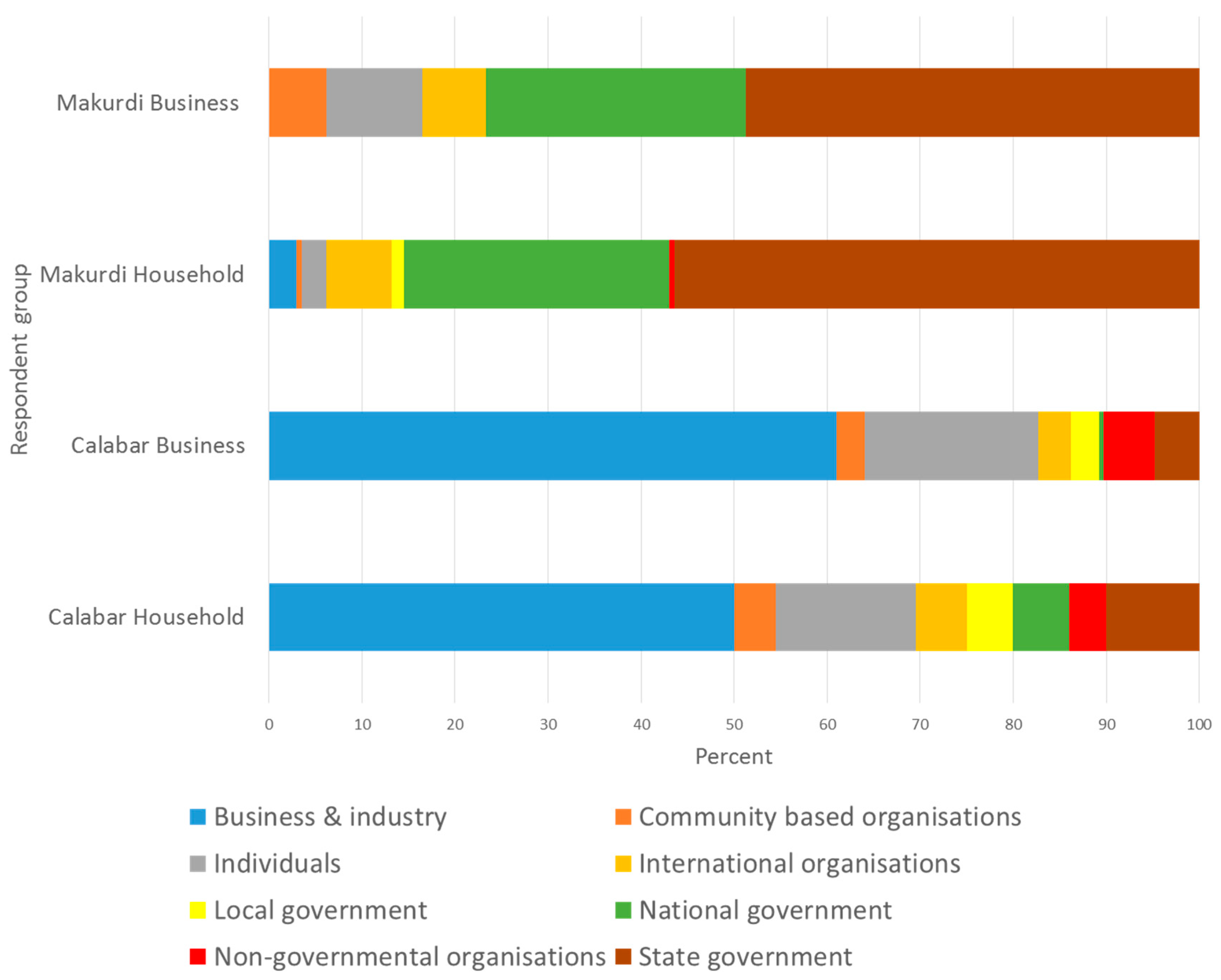

Businesses and households in Calabar were more likely to have received climate hazard information in the last 12 months (58.2% of households and 49.5% of businesses) than in Makurdi (27.4% households and 26.4% businesses). Information sourced from business and industry, including the media, may be part of the explanation for this discrepancy since this is the main source of information in Calabar as opposed to government information in Makurdi for both households and businesses (see

Figure 4).

The influence of household characteristics both on the receipt of information and the preferences of households for mode and source of information was explored through the household questionnaire data. This analysis suggests that in general demographic characteristics have a greater association with perceptions of and access to information in Makurdi than in Calabar.

In Calabar, income had a small but statistically significant association with the receipt of information (4% less received information in low income households) as indicated in

Table 4. However, in Makurdi, those with lower than average income were much less likely to have received information. Only 6.8% of low income households have received information compared to 34.1% of higher income households. Coupled with the fact that, in general, households in Makurdi were less likely to receive information than those in Calabar, further investigation into the source of such information appears to be important.

Differences between households include the larger contribution of business and industry to information provision in Calabar regardless of income level; most provision in Makurdi is governmental with a small amount from international organisations. There is almost a complete absence of receipt of community-based provision of information in Makurdi, with low income households in Makurdi receiving no information except that from business and industry, and national and state government.

The gender of the head of household has very little impact on the likelihood of receiving information; although slightly more female headed households received information (6% in Makurdi, 1% in Calabar), this is not a statistically significant difference.

Age had a small but statistically significant association with receipt of information (Makurdi, Kruskall-Wallis significant at 5%, Calabar, Kruskall-Wallis significant at 1%). Those with a head of household in the dependent age group were less likely than others to have received information (lower by 9% in Makurdi and 2% in Calabar). Households in Makurdi with heads within the dependent age group received information from four sources only, business and industry, international organisations, national government and state government.

The more educated a household head is, the more likely that member of their household will receive climate hazard information (Kruskall-Wallis & Median test, significant at 1%). In Makurdi, 4% of those with no schooling, 9% with primary, 13% with secondary and 41% of those with educational level above secondary level have received climate hazard information. In Calabar, the educational level also made a difference with 52% of those with up to secondary level education and 63% of those with education above secondary receiving information. However, the range of sources of information was also greater for those without schooling.

There were differences by religion in terms of level and sources of information (Makurdi, Kruskall-Wallis significant at 1%, Calabar, Kruskall-Wallis significant at 1%). In Calabar and Makurdi, respondents who were Christians were in the majority. Christians were also the most likely to have received information in Makurdi but least likely in Calabar. Those with traditional religious affiliation were more likely to get their information from friends, neighbours and community sources and less likely to get information from business and industry than Christians as were Muslims.

The occupation of the head of household was also associated with differences in receipt of climate hazard information (Makurdi, Kruskall-Wallis significant at 1%, Calabar, Kruskall-Wallis significant at 1%). Agricultural workers were least likely to receive information in both Makurdi and Calabar, and health and education, public service workers and business workers were more likely to be informed.

Housing tenure does not have any major or statistically significant effect on the ability to receive climate hazard information in either site.

3.3. Preferences and Trust

The top three most trusted sources of information in Calabar are business and industry, state government and national government, respectively (for both households and business respondents). State government and national government are also in the top three in Makurdi. However, business and industry which ranked highest in Calabar was the least trusted among households in Makurdi. In Makurdi, international organisations and neighbours/individuals were more readily trusted. In Makurdi 77% and in Calabar 59% of households received the information from their most trusted organisation. Those receiving the information from organisations they trusted less would usually trust a government source above their current source. In Makurdi, the government was the main source and those receiving information from international sources also trusted that source the most. Makurdi businesses similarly relied on and trusted government information. Among Calabar households and businesses, only one third of those receiving information from friends and neighbours trusted this source the most. Those receiving information from business and media in Calabar generally trusted it (67% of households and 75% of businesses trusting it the most).

Differences in trust that relate to household income are shown in

Table 5. Although those on lower incomes in Makurdi showed some tendency to trust local and neighbourhood sources more than those on higher incomes, still state or national provision was more trusted. In Calabar, the pattern in preferences related to income are less clear and are not statistically significant; state government was more trusted by lower income households. However, business and industry was most trusted.

Radio and television are the most preferred medium to receive information across cities and for both households and businesses, with radio being the top choice. The proportion is higher in Makurdi than Calabar i.e., 79.3% of households and 78.2% of businesses in Makurdi favour this medium while 56.7% of households and 62.3% of businesses in Calabar favour it. SMS/text messaging was the third most preferred medium among both groups in both sites. These differences are not statistically significant. Female heads of household were slightly more likely to prefer radio compared to males who use newspapers and digital sources. Households with dependent aged heads were most likely to prefer radio and word of mouth than those with independent aged households.

3.4. The Importance of Information for Warning and Adaptation

Households and businesses were asked about their coping strategies; respondents could select multiple actions from a predetermined list derived from the literature or state “other” (see

Figure 5). The majority of community members indicated that they listened to media to get information and this appeared to be in order to move people and belongings to safety. They also indicated that they followed laws and regulations, another activity that relies on the provision of information such as hazard maps. To a great extent, during a hazard event, communities rely on government action in terms of provision of warnings and emergency management.

Adaptation strategies such as flood boards and elevating homes are less widely practiced although reasonably common. Coping strategies that were seen by significant numbers of households and businesses as not effective included: flood gates and barriers, and relying on the goodwill of neighbours. Ecosystems and behavioural adaptation are not selected as preferred approaches to adaptation by respondents, but planting trees was seen as a helpful strategy for flooding.

Linked to this, it is apparent that community capital and community-based resilience is low in the studied communities. Individuals take actions but do not appear to be able to rely on others for help or support; more respondents would rely on prayer than on their neighbours. These findings imply that the most economically vulnerable are likely to be least resilient since they cannot rely on social or other capital. They also reinforce the findings from the stakeholder workshops that suggest a lack of synergy and consultation is a barrier to management of climate adaptation.

3.5. Suggested Way Forward

Suggestions from the stakeholder workshops discussions to address informational gaps included the establishment of new government agencies with a mandate to provide coordination of data and information on risk management. Such data could be made widely available and subjected to validation by non-governmental experts. This was suggested to be enabled through widening participation in climate debates of stakeholder groups, professional organisations and academics during regular deliberative meetings and consultations. Increased training for professionals was also called for.

There was also a perceived need to constantly educate and sensitise residents to risk and adaptation opportunities. Many participants in the workshops believed that greater involvement of professionals in raising environmental awareness would bring in valuable skills and knowledge and that local government could establish units to encourage environmental education, manned by professionals in the field.

5. Conclusions

The study sought to explore the adequacy and use of information by stakeholders and communities in two Nigerian cities with a view to understanding future requirements and preferences.

The study found that there is a perceived need for improved data and information for all local actors in that they required improved information to pursue their current risk management strategies. However, it was also clear that the current range of strategies employed was constrained by the available information. Improved information together with capacity building for state and local government could allow implementation of more adaptive risk management strategies such as risk zoning and risk communication.

Communities rated information very highly within their adaptation strategies, however, the study underscores the often observed disconnect in climate hazard information provision to local communities. Differences in the receipt and trust in information between cities and groups within cities were found, and this demonstrates that risk communication and adaptation strategies will need to be cognisant of the needs of diverse communities. There is a need to institutionalise climate hazard information at a local level.

The study suggested that widening participation in risk management to include professionals, experts, academics and communities could increase focus on preparedness and increase compliance with government strategies. Increased synergy between governmental actors is also required to exploit the available data.

Both cities are well positioned to access promising resources to draw on in responding to the findings of this study. For instance, in Makurdi, the presence of two universities, the Lower-Benue River Basin Development Agency and the Nigerian Air Force base with expertise and some longitudinal climate data. Differences in information provided to communities (households and businesses) between cities also appears to suggest a wider role for business, industry and media which might improve risk communication. Although this study has indicated a direction of travel in the provision of climate services, further research is required to determine the appropriate roles for governmental and non-governmental organisations in providing warning and preparedness information that is reliable and trusted.

However, when designing improved climate information services, care must be taken to ensure that this information is available to the most vulnerable in a form that they can use and that they trust. This could be facilitated through the involvement of community representatives from the very early stages to define appropriate end user requirements.

The questionnaire results presented here are highly innovative. By asking the same questions in two Nigerian cities within one study, they can reveal similarities and differences not usually captured. The results show some remarkable similarities in respect to the preferred strategies for adaptation, indicating some common attitudes and perceptions that are slightly tempered by differences in hazard experience. These also accord broadly with results of previous studies on preferred strategies. However, there are much greater differences in responses related to the receipt of climate hazard information. Based on this finding, it would be unwise to generalise to other Nigerian cities regarding details of the availability of information or preferences of local communities. What can be learned from this study is the requirement to consult communities and stakeholders on their needs before assuming a national approach to climate information provision. While this study has been conducted with the case study of Makurdi and Calabar, other studies could focus on other developing cities in Nigeria or elsewhere to identify climate hazard information needs and availability to a wide range of stakeholders.