Youth Perceptions of 1.5-Degree Lifestyle to Adapt to Climate Change: A Case Analysis of Japanese University Students

Abstract

1. Introduction

1.1. Japan’s Responses to Climate Change

1.2. The Potential of 1.5-Degree Lifestyles in Japan

1.3. Youth Perception of Climate Change

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Research Design

2.2. Data Collection

2.3. Technical Details

2.4. Data Analysis

2.5. Ethical Considerations

3. Results

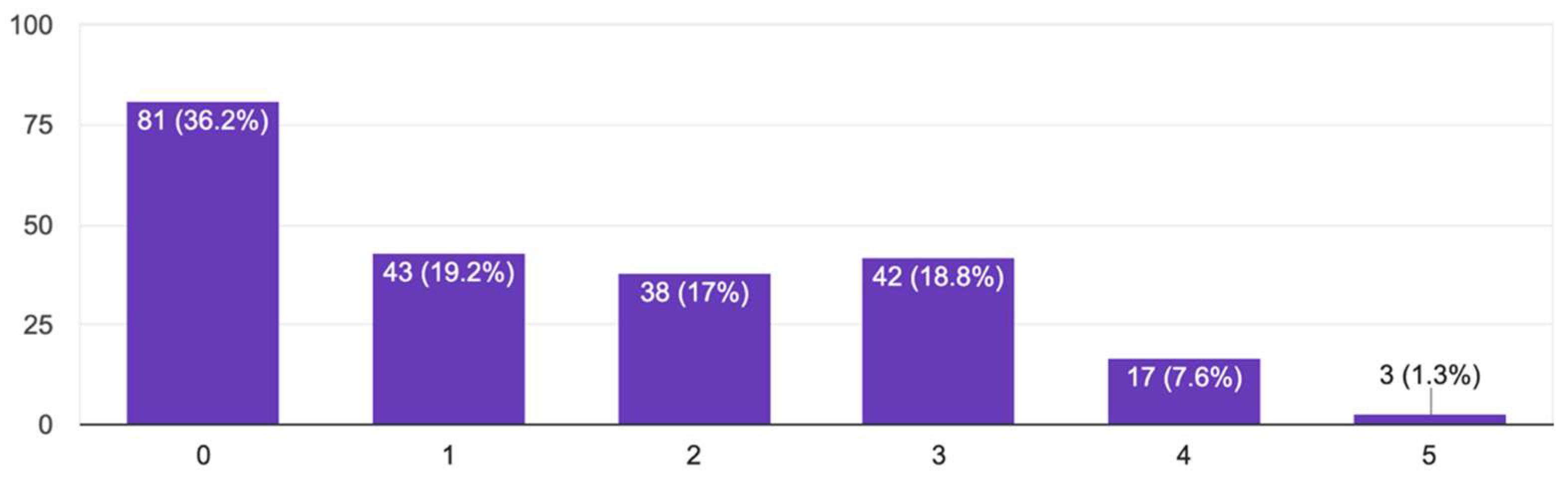

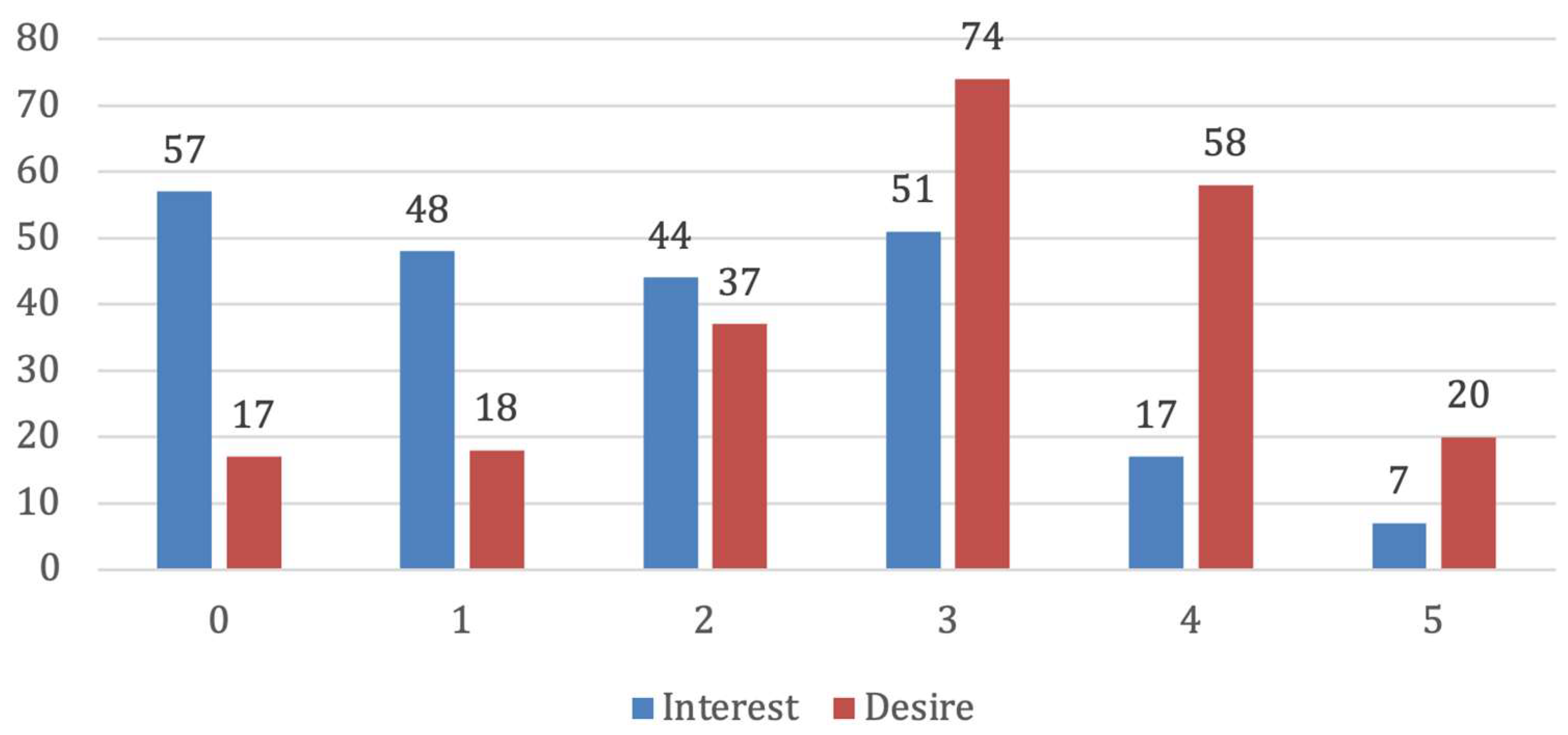

3.1. Recognition of 1.5-Degree Lifestyle

- Early education (elementary/middle school) shows the highest awareness levels (40–50% ‘Yes’), and awareness declines progressively through higher education levels.

- The non-educated group demonstrates significantly lower awareness (15%) and higher skepticism (75% ‘Not sure’).

- The Interest distribution remains relatively stable across education levels (40–45% low; 42–46% moderate). However, non-educated group shows markedly lower interest (75% ‘0–1’; 0% ‘4–5’).

- Desire strengthens significantly from elementary to higher education levels. Middle school through university show remarkably similar desire patterns. The non-educated group again demonstrates the weakest engagement in desire (50% ‘0–1’).

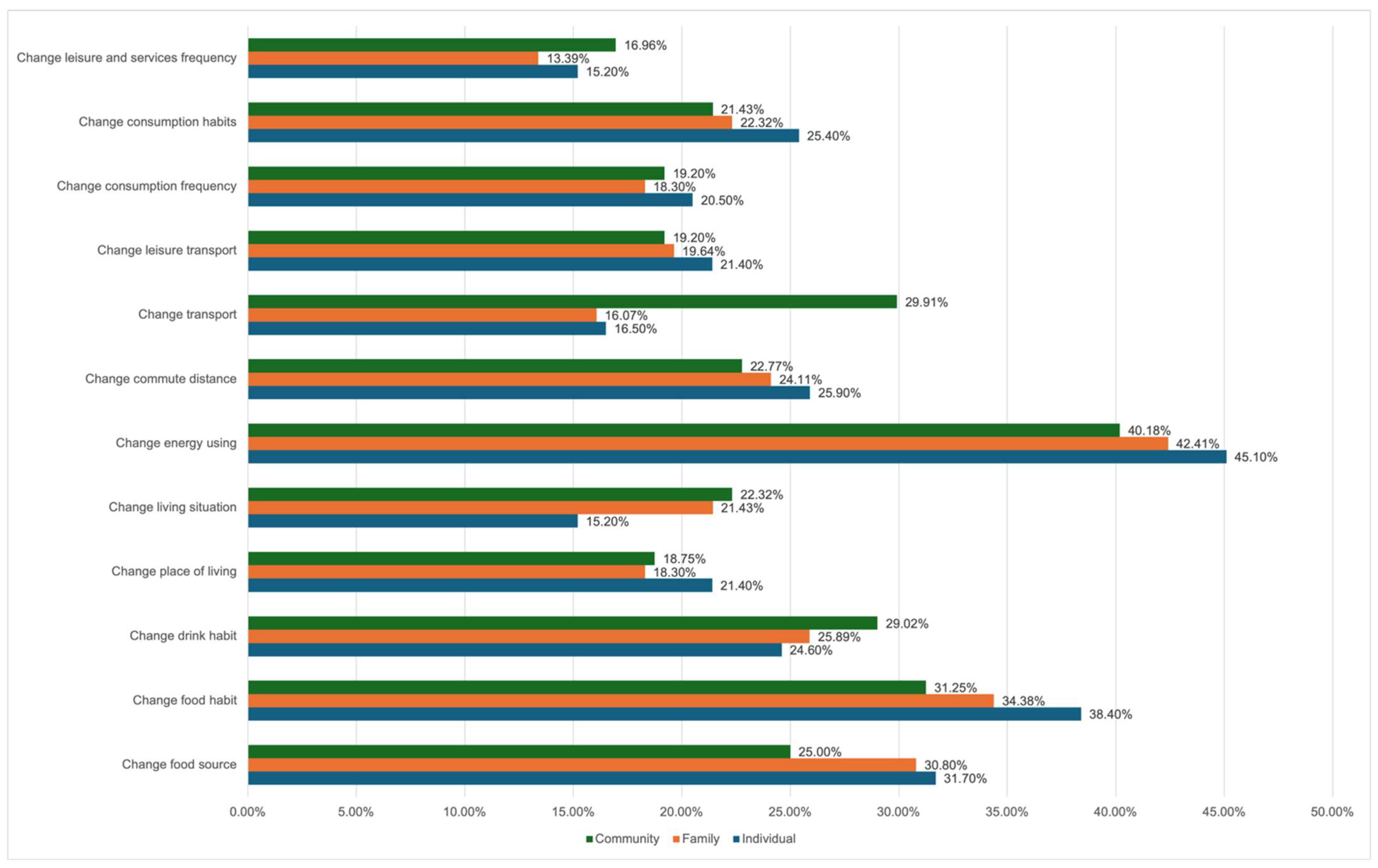

3.2. Preference for Actions to Change Lifestyle

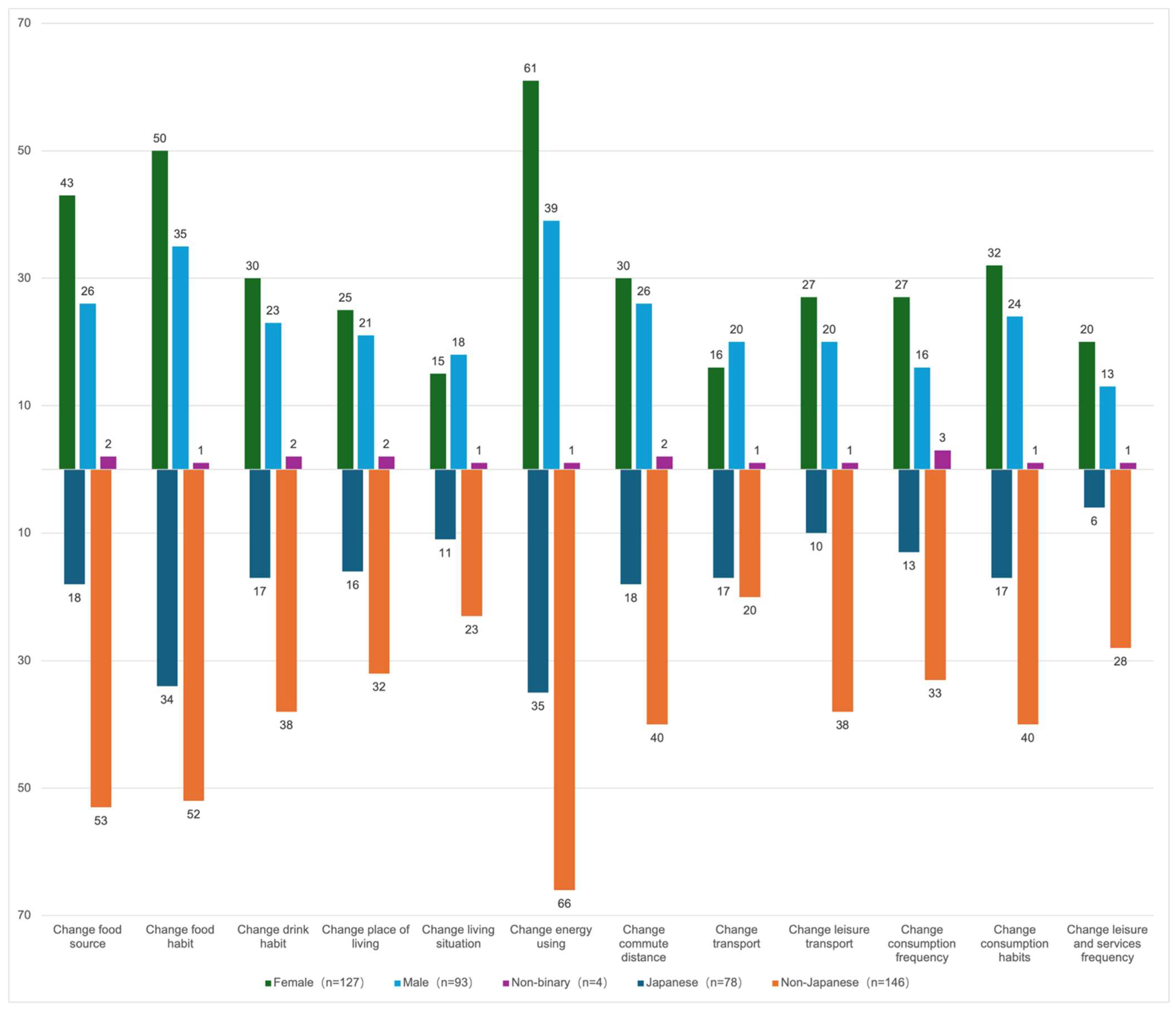

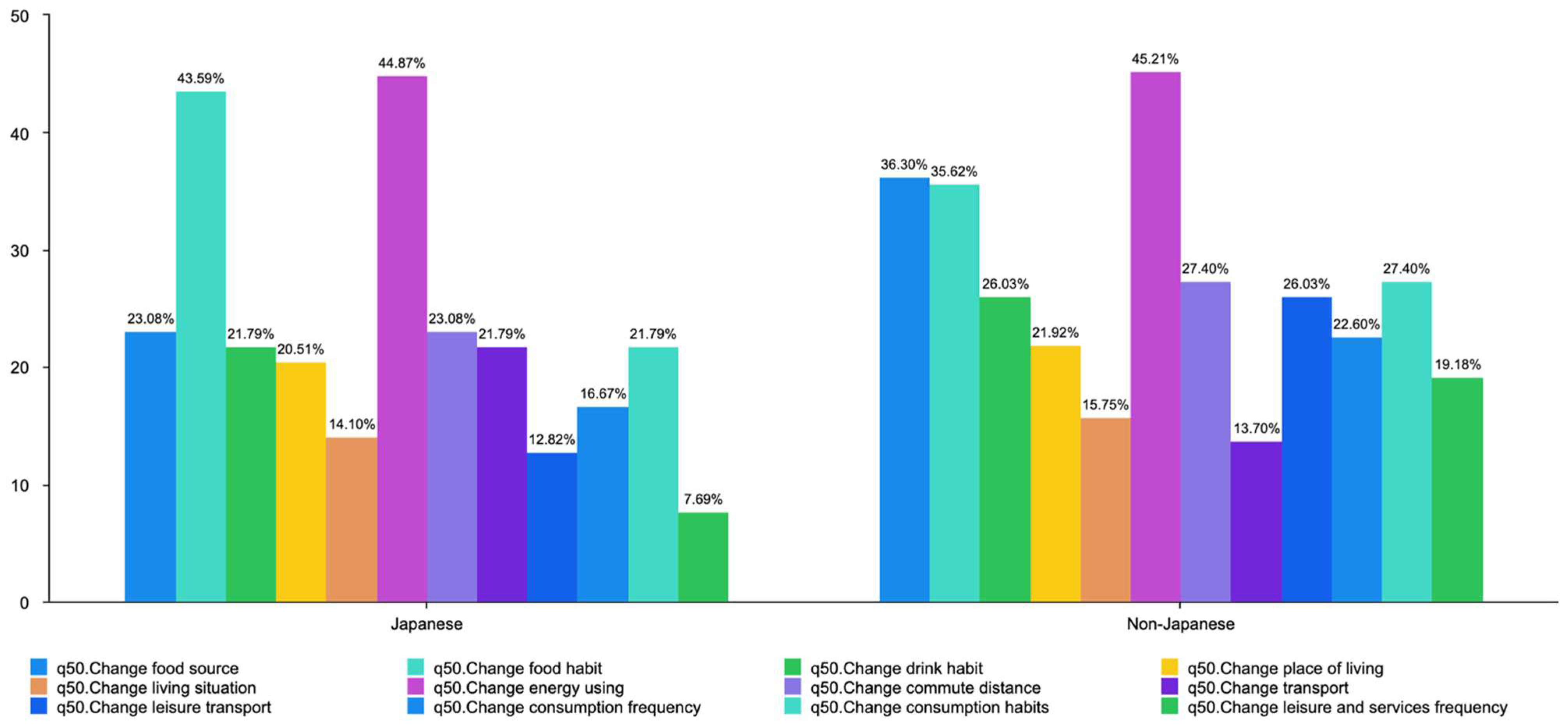

3.2.1. Differences in Nationality and Gender Regarding Lifestyle Change Preferences

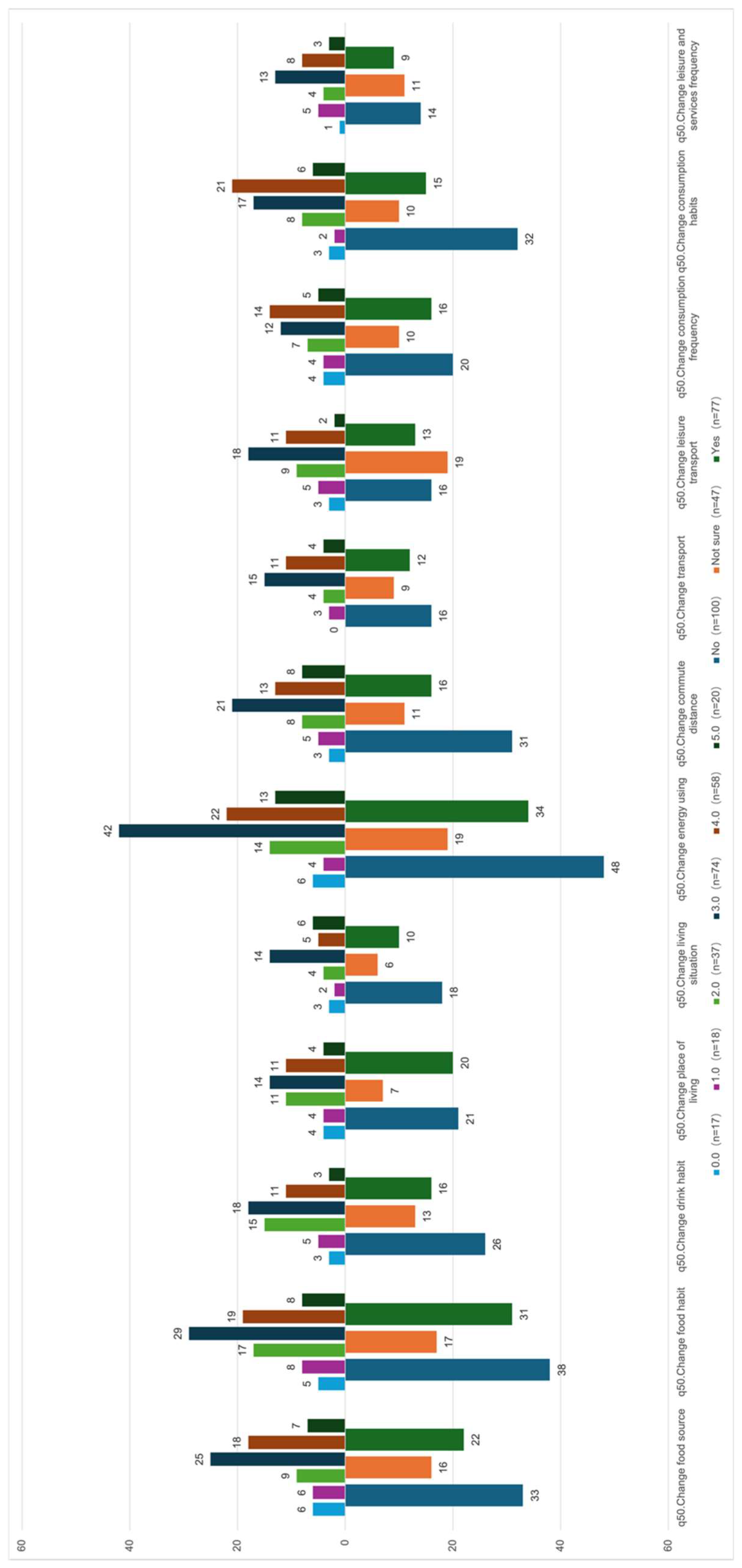

3.2.2. Analysis of Lifestyle Change Preferences Based on Knowledge Level and Desire

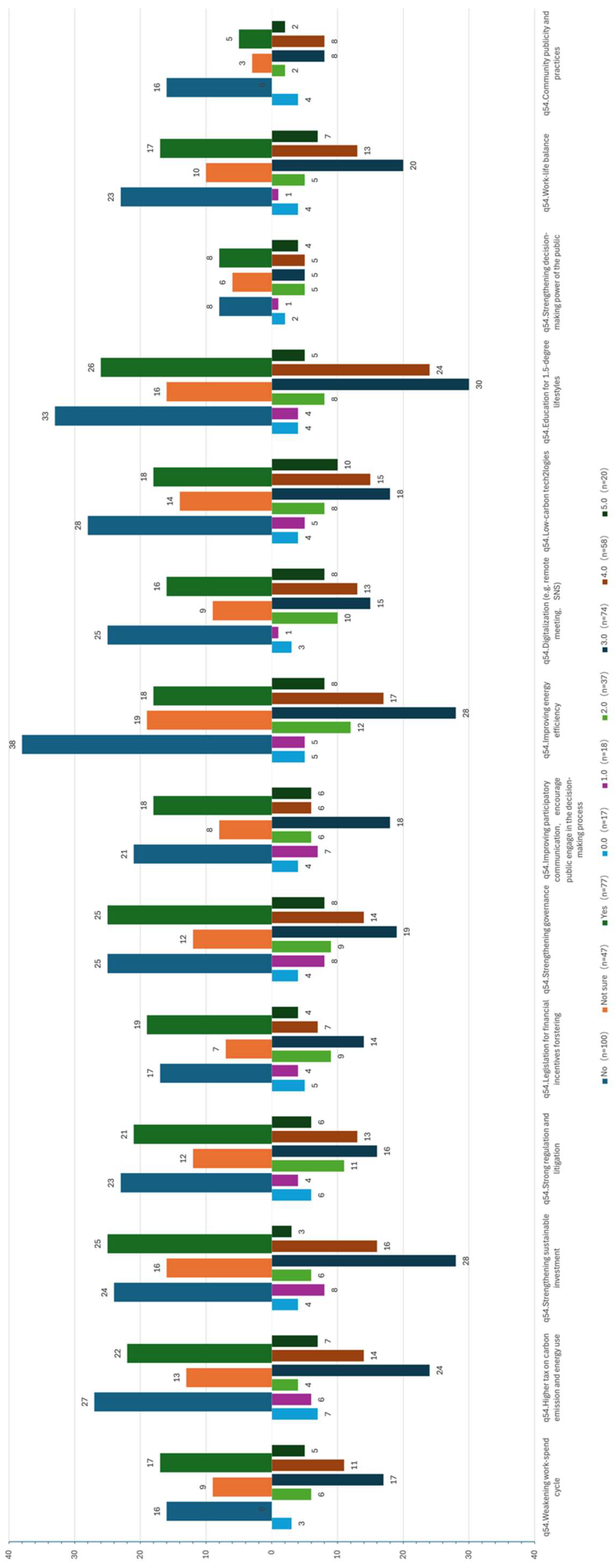

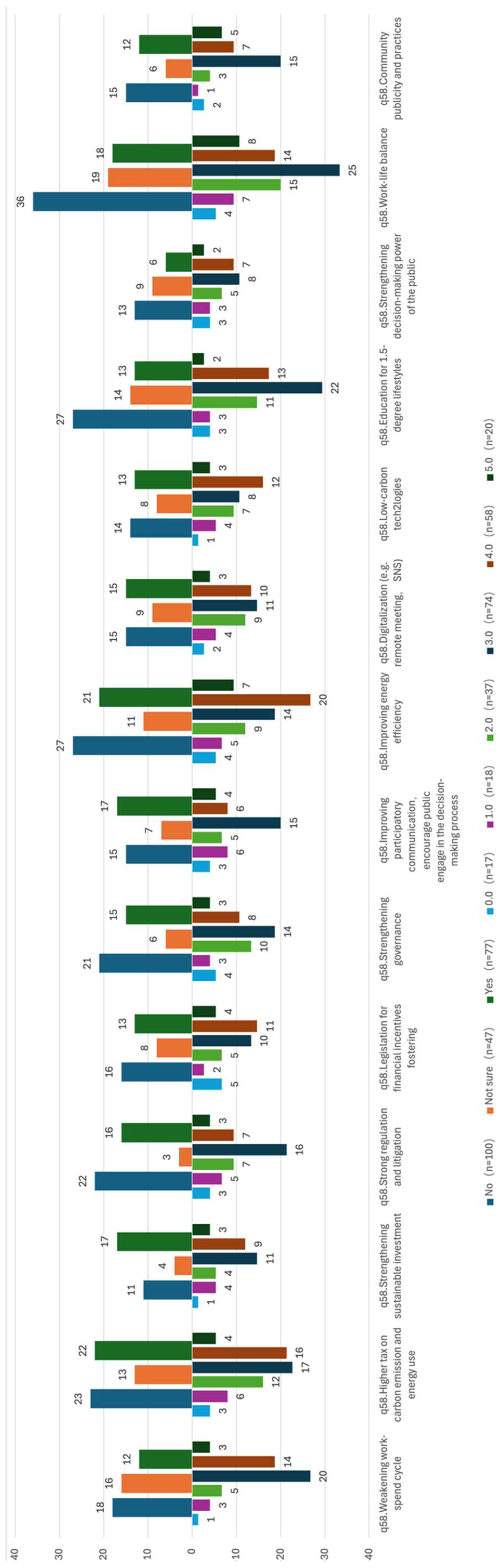

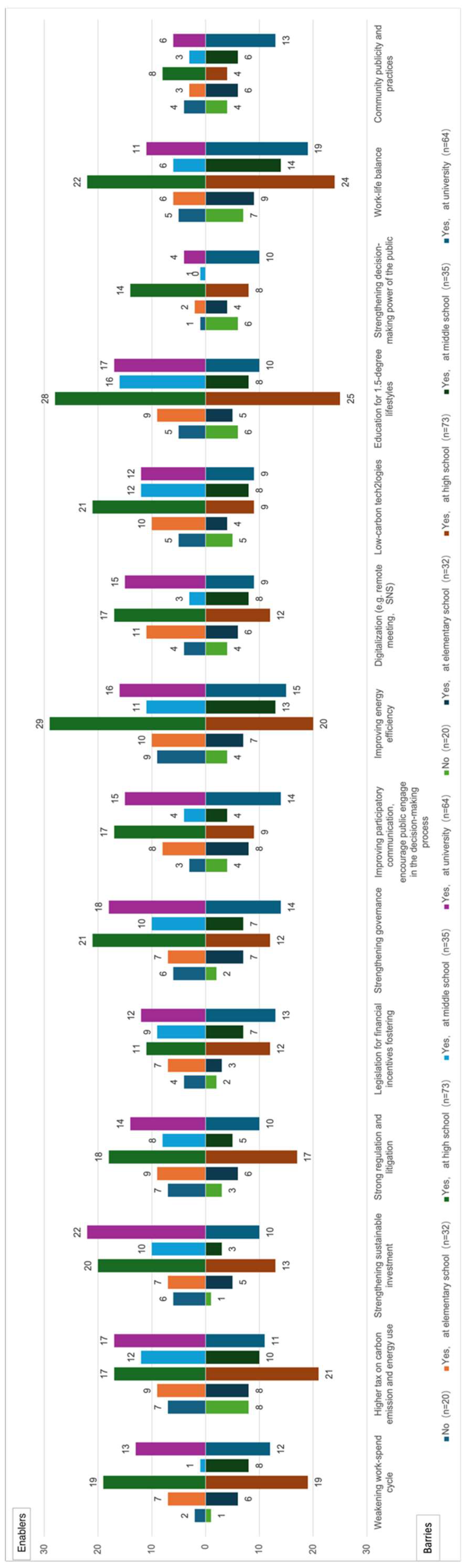

3.3. Enablers and Barriers to Adopting a 1.5-Degree Lifestyle

3.3.1. Nationality and Gender Preferences for Enabling Factors

3.3.2. Enablers and Barriers for 1.5-Degree Lifestyles: Analysis Based on Where Participants Received Environmental Education

4. Discussion

4.1. Recognition of 1.5-Degree Lifestyle

4.2. Actions for Changing Lifestyle

- Promote food habits and energy use as key behavioral changes based on Figure 4. For example, launch campaigns in supermarkets to encourage greener food options and collaborate with restaurants to promote low-carbon menus.

- Use nationality and gender differences to guide targeted engagement [44]. Promote energy-efficient transportation for foreigners in Japan. Develop community-led sustainability networks for women and encourage technological sustainability for men, as they tend to show more interest in methods.

- Address gaps in knowledge and motivation. To better encourage people with low desire or limited awareness, campaigns should emphasize personal benefits like cost savings and better health. High-desire individuals would gain from more advanced, action-focused resources to support deeper lifestyle changes.

- Develop community-based strategies, especially for transportation and consumption habits. Improve public transit infrastructure and promote greener commuting options at schools and workplaces. Organize second-hand goods exchanges or buying markets and support sustainable brands.

- Strengthen community and political support. Structural barriers, such as limited infrastructure, high costs of green products, and lack of incentives, should be tackled through better policy coordination and collaboration among municipalities.

4.3. Enablers and Barriers to 1.5-Degree Lifestyle Living

5. Conclusions

Limitations and Recommendations for Future Studies

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A. (Made by Authors)

- What is your gender?

- Female

- Male

- Non-binary

- What program are you in?

- Undergraduate

- Master

- Doctoral

- Other

- Please fill in your nationality.

- (Open-ended response) ________________

- Which prefecture in Japan are you from? (International students, please write down your prefecture of residence).

- (Open-ended response) ________________

- Have you received any environmental education in school?

- Yes, at elementary school

- Yes, at middle school

- Yes, at high school

- Yes, at university

- No

- Have you ever participated in any environmental-related activities? (Multiple answers are accepted.)

- Have attended lectures

- Participated in volunteer activities

- Participated in environmental theme activities

- Delivered relevant presentations in class or elsewhere

- No, never participated in any relevant events

- Other: ________________

- If ‘other’ is selected in question 6, please elaborate the activity.

- (Open-ended response) ________________

- 8.

- Are you aware of the concept of the 1.5-degree lifestyles?

- Yes

- No

- Not sure

- 9.

- How familiar are you with the 1.5-degree lifestyles?

- 10.

- Where did you first learn about the 1.5-degree lifestyles?

- News media

- Educational institutions

- Social media

- Advertisement

- Family

- Take part in the survey

- 11.

- Do you usually hear about the 1.5-degree lifestyles in your life?

- 12.

- To what extent do you understand the meaning and purpose of the 1.5-degree lifestyles?

- 13.

- How often do you have the opportunity to access topics and news related to the 1.5-degree lifestyles and climate change?

- 14.

- Where do you usually read about the 1.5-degree lifestyles?

- News media

- Educational institutions

- Social media

- Advertisement

- Family

- Take part in the survey

- 15.

- To what extent do you want to learn about the 1.5-degree lifestyles?

- 16.

- How do you feel about living in the 1.5-degree lifestyles?

- 17.

- Can you identify some action that is consistent with a 1.5-degree lifestyle?

- 18.

- Can you identify the government strategies for dealing with climate change or promoting the 1.5-degree lifestyles?

- 19.

- Have you ever discussed the 1.5-degree lifestyle (related topics also count) with others?

- Yes

- No

- Not sure

- 20.

- Will you introduce 1.5-degree lifestyles to your friends, family, etc.

- Yes

- No

- Maybe

- 21.

- Source: How do you manage your daily meal?

- At home (Self-cooked food)

- Eat outside

- Delivery food

- 22.

- Food habit: What do you prefer for meals?

- Vegetables

- Meats

- I am vegan.

- 23.

- Drink habit: What do you usually have for drinks?

- Water

- Alcohol

- Soft drink

- 24.

- Based on the proposed actions in this survey, please choose the one action you (individual) would most like to make changes.

- Change food source

- Change food habit

- Change drink habit

- 25.

- Based on the proposed actions in this survey, please choose the one action your (family) would most like to make changes.

- Change food source

- Change food habit

- Change drink habit

- 26.

- Based on the proposed actions in this survey, please choose the one action your (community) would most like to make changes.

- Change food source

- Change food habit

- Change drink habit

- 27.

- Place of living: Where do you live?

- City center

- Suburbs

- 28.

- Living situation: Who do you live with?

- Live alone

- Live with friends/partners.

- Live with family

- 29.

- Energy using: What energy are you consciously conserving?

- Electricity

- Water

- Waste sorting

- 30.

- Based on the proposed actions in this survey, please choose the one action you (individual) would most like to make changes.

- Change place of living

- Change living situation

- Change energy using

- 31.

- Based on the proposed actions in this survey, please choose the one action your (family) would most like to make changes.

- Change place of living

- Change living situation

- Change energy using

- 32.

- Based on the proposed actions in this survey, please choose the one action your (community) would most like to make changes.

- Change place of living

- Change living situation

- Change energy using

- 33.

- Commute distance: How long is your commute?

- Within 30 min

- 30 min to 1 h

- More than 1 h

- 34.

- Commute transport: How do you commute to the university/work?

- Own transport equipment

- Public transport

- Both

- 35.

- Leisure transport: What kind of transport do you take for leisure?

- Own transport equipment

- Public transport

- Both

- 36.

- What is your most frequent means of transport?

- Bicycle

- Motorcycle

- Car

- Bus

- Train

- Walking

- 37.

- Based on the proposed actions in this survey, please choose the one action you (individual) would most like to make changes.

- Change commute distance

- Change commute transport

- Change leisure transport

- 38.

- Based on the proposed actions in this survey, please choose the one action your (family) would most like to make changes.

- Change commute distance

- Change commute transport

- Change leisure transport

- 39.

- Based on the proposed actions in this survey, please choose the one action your (community) would most like to make changes.

- Change commute distance

- Change commute transport

- Change leisure transport

- 40.

- Consumption frequency: How long do you usually consume for daily necessities?

- Everyday

- Multiple time a week

- Multiple time a month

- Multiple time a year

- 41.

- Consumption Habit: What do you usually consume?

- Daily consumable

- Non-daily consumable

- Both

- 42.

- Based on the proposed actions in this survey, please choose the one action you (individual) would most like to make changes.

- Change consumption frequency

- Change consumption habits

- 43.

- Based on the proposed actions in this survey, please choose the one action your (family) would most like to make changes.

- Change consumption frequency

- Change consumption habits

- 44.

- Based on the proposed actions in this survey, please choose the one action your (community) would most like to make changes.

- Change consumption frequency

- Change consumption habits

- 45.

- Leisure Activity & Use of Services Frequency: How often do you consume for your leisure?

- Everyday

- Multiple time a week

- Multiple time a month

- Multiple time a year

- 46.

- Most Frequent Leisure & Service: What do you usually purchase for your leisure and services?

- Sports

- Entertainment

- Culture

- Health check/medicine

- Insurance

- Financial items (e.g., stock, etc.)

- Others

- 47.

- Based on the proposed actions in this survey, please choose the one action you (individual) would most like to make changes.

- Change leisure & services frequency

- Change the most frequent leisure & services

- 48.

- Based on the proposed actions in this survey, please choose the one action your (family) would most like to make changes.

- Change leisure & services frequency

- Change the most frequent leisure & services

- 49.

- Based on the proposed actions in this survey, please choose the one action your (community) would most like to make changes.

- Change leisure & services frequency

- Change the most frequent leisure & services

- 50.

- Based on the proposed actions in this survey, please choose the three action you (individual) would most like to make changes.

- Change food source

- Change food habit

- Change drink habit

- Change place of living

- Change living situation

- Change energy using

- Change commute distance

- Change transport

- Change leisure transport

- Change consumption frequency

- Change consumption habits

- Change leisure and services frequency

- 51.

- Based on the proposed actions in this survey, please choose the three action your (family) would most like to make changes.

- Change food source

- Change food habit

- Change drink habit

- Change place of living

- Change living situation

- Change energy using

- Change commute distance

- Change transport

- Change leisure transport

- Change consumption frequency

- Change consumption habits

- Change leisure and services frequency

- 52.

- Based on the proposed actions in this survey, please choose the three action your (community) would most like to make changes.

- Change food source

- Change food habit

- Change drink habit

- Change place of living

- Change living situation

- Change energy using

- Change commute distance

- Change transport

- Change leisure transport

- Change consumption frequency

- Change consumption habits

- Change leisure and services frequency

- 53.

- What enabling factors do you think help you the most to 1.5-degree lifestyles?

- Economic

- Political

- Technological

- Societal

- 54.

- What are enabling factors do you think help you (individual) the most to 1.5-degree lifestyles?

- Weakening work-spend cycle

- Higher tax on carbon emission and energy use

- Strengthening sustainable investment

- Strong regulation and litigation

- Legislation for financial incentives fostering

- Strengthening governance

- Improving participatory communication, encourage public engage in the decision-making process

- Improving energy efficiency

- Digitalization (e.g., remote meeting, SNS)

- Low-carbon technologies

- Education for 1.5-degree lifestyles

- Strengthening decision-making power of the public

- Work-life balance

- Community publicity and practices

- 55.

- What are enabling factors do you think help your (family) the most to 1.5-degree lifestyles?

- Weakening work-spend cycle

- Higher tax on carbon emission and energy use

- Strengthening sustainable investment

- Strong regulation and litigation

- Legislation for financial incentives fostering

- Strengthening governance

- Improving participatory communication, encourage public engage in the decision-making process

- Improving energy efficiency

- Digitalization (e.g., remote meeting, SNS)

- Low-carbon technologies

- Education for 1.5-degree lifestyles

- Strengthening decision-making power of the public

- Work-life balance

- Community publicity and practices

- 56.

- What are enabling factors do you think help your (community) the most to 1.5-degree lifestyles?

- Weakening work-spend cycle

- Higher tax on carbon emission and energy use

- Strengthening sustainable investment

- Strong regulation and litigation

- Legislation for financial incentives fostering

- Strengthening governance

- Improving participatory communication, encourage public engage in the decision-making process

- Improving energy efficiency

- Digitalization (e.g., remote meeting, SNS)

- Low-carbon technologies

- Education for 1.5-degree lifestyles

- Strengthening decision-making power of the public

- Work-life balance

- Community publicity and practices

- 57.

- What do you think are the biggest barriers to a 1.5-degree lifestyle?

- Economic

- Political

- Technological

- Societal

- 58.

- What do you think are the three biggest barriers to your (individual) 1.5-degree lifestyles?

- Weakening work-spend cycle

- Higher tax on carbon emission and energy use

- Strengthening sustainable investment

- Strong regulation and litigation

- Legislation for financial incentives fostering

- Strengthening governance

- Improving participatory communication, encourage public engage in the decision-making process

- Improving energy efficiency

- Digitalization (e.g., remote meeting, SNS)

- Low-carbon technologies

- Education for 1.5-degree lifestyles

- Strengthening decision-making power of the public

- Work-life balance

- Community publicity and practices

- 59.

- What do you think are the three biggest barriers to your (family’s) 1.5-degree lifestyles?

- Weakening work-spend cycle

- Higher tax on carbon emission and energy use

- Strengthening sustainable investment

- Strong regulation and litigation

- Legislation for financial incentives fostering

- Strengthening governance

- Improving participatory communication, encourage public engage in the decision-making process

- Improving energy efficiency

- Digitalization (e.g., remote meeting, SNS)

- Low-carbon technologies

- Education for 1.5-degree lifestyles

- Strengthening decision-making power of the public

- Work-life balance

- Community publicity and practices

- 60.

- What do you think are the three biggest barriers to your (community’s) 1.5-degree lifestyles?

- Weakening work-spend cycle

- Higher tax on carbon emission and energy use

- Strengthening sustainable investment

- Strong regulation and litigation

- Legislation for financial incentives fostering

- Strengthening governance

- Improving participatory communication, encourage public engage in the decision-making process

- Improving energy efficiency

- Digitalization (e.g., remote meeting, SNS)

- Low-carbon technologies

- Education for 1.5-degree lifestyles

- Strengthening decision-making power of the public

- Work-life balance

- Community publicity and practices

References

- World Meteorological Organization. 2024 is on Track to be Hottest Year on Record as Warming Temporarily Hits 1.5 °C; World Meteorological Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2024; Available online: https://wmo.int/news/media-centre/2024-track-be-hottest-year-record-warming-temporarily-hits-15degc (accessed on 11 June 2025).

- Japan Meteorological Agency. The weather in the summer of 2024 (from June to August); Japan Meteorological Agency: Tokyo, Japan, 2024. Available online: https://www.data.jma.go.jp/cpd/longfcst/seasonal/202408/202408s.html (accessed on 11 June 2025).

- IPCC. Global Warming of 1.5 °C: An IPCC Special Report on the Impacts of Global Warming of 1.5 °C Above Pre-Industrial Levels and Related Global Greenhouse Gas Emission Pathways, in the Context of Strengthening the Global Response to the Threat of Climate Change, Sustainable Development, and Effort to Eradicate Poverty; Masson-Delmotte, V., Zhai, P., Pörtner, H.-O., Roberts, D., Skea, J., Shukla, P.R., Pirani, A., Moufouma-Okia, W., Péan, C., Pidcock, R., et al., Eds.; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK; New York, NY, USA, 2018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- IGES. 1.5-Degree Lifestyles: Targets and Options for Reducing Lifestyle Carbon Footprints; IGES: Hayama, Japan, 2019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guan, Y.; Shan, Y.; Hang, Y.; Nie, Q.; Liu, Y.; Hubacek, K. Unlocking global carbon reduction potential by embracing low-carbon lifestyles. Nat. Commun. 2025, 16, 4599. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wiedmann, T.; Minx, J. A Definition of ‘Carbon Footprint’. Ecol. Econ. Res. Trends 2008, 1, 1–11. Available online: https://wiki.epfl.ch/hdstudio/documents/articles/a%20definition%20of%20carbon%20footprint.pdf (accessed on 11 June 2025).

- HotorCool. 1.5-Degree Lifestyles: Towards A Fair Consumption Space for All; HotorCool: Berlin, Germany, 2021; Available online: https://hotorcool.org/wp-content/uploads/2021/10/Hot_or_Cool_1_5_lifestyles_FULL_REPORT_AND_ANNEX_B.pdf (accessed on 11 June 2025).

- O’Brien, K.; Selboe, E.; Hayward, B. Exploring youth activism on climate change: Dutiful, disruptive, and dangerous dissent. Ecol. Soc. 2018, 23, 42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- United Nation. Kyoto Protocol to the United Nations Framework; United Nation: New York, NY, USA, 1998. [Google Scholar]

- The Government of Japan. Submission of Japan’s Intended Nationally Determined Contribution (INDC); The Government of Japan: Tokyo, Japan, 2015. Available online: https://www.mofa.go.jp/files/000090898.pdf (accessed on 11 June 2025).

- United Nation. The Paris Agreement; United Nation: New York, NY, USA, 2015; Available online: https://unfccc.int/process-and-meetings/the-paris-agreement (accessed on 11 June 2025).

- Cabinet Office. Environment Innovation Strategy; Cabinet Office: Sydney, Australia, 2020. Available online: https://www8.cao.go.jp/cstp/tougosenryaku/kankyo_en.pdf (accessed on 11 June 2025).

- Ministry of Economy, Trade and Industry. Green Innovation Fund; Ministry of Economy, Trade and Industry: Tokyo, Japan, 2022. Available online: https://www.meti.go.jp/english/policy/energy_environment/global_warming/gifund/index.html (accessed on 11 June 2025).

- Ministry of Finance, Japan. Japan Climate Transition Bonds; Ministry of Finance, Japan: Tokyo, Japan, 2023. Available online: https://www.mof.go.jp/english/policy/jgbs/topics/JapanClimateTransitionBonds/index.html (accessed on 11 June 2025).

- Zhao, Z.; Huang, R.; Zhang, Y.; Shiga, Y.; Shaw, R. Assessing the Role of Climate Transition Bonds in Advancing Green Transformations in Japan. Climate 2024, 12, 201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ohta, H.; Barrett, B.F. Politics of climate change and energy policy in Japan: Is green transformation likely? Earth Syst. Gov. 2023, 17, 100187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nielsen, S. Initiating Transitions Towards 1.5-Degree Lifestyles: An Action Research Study on a Design Game. 2020. Available online: https://aaltodoc.aalto.fi/items/7814c696-6ab6-466e-82b3-d89876b3c8b3 (accessed on 11 June 2025).

- Liu, C.; Yamabe-Ledoux, A.M. Challenges in Achieving 1.5-Degree Lifestyle Mitigation Options—Insights from a Citizen-Participatory Household Experiment in Japan. Sustainability 2023, 15, 11949. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vadovics, E.; Richter, J.L.; Tornow, M.; Ozcelik, N.; Coscieme, L.; Lettenmeier, M.; Scherer, L. Preferences, enablers, and barriers for 1.5° C lifestyle options: Findings from Citizen Thinking Labs in five European Union countries. Sustain. Sci. Pract. Policy 2024, 20, 2375806. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Watabe, A.; Yamabe-Ledoux, A.M. Low-carbon lifestyles beyond decarbonisation: Toward a more creative use of the carbon footprinting method. Sustainability 2023, 15, 4681. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neumann, K.; Hirschnitz-Garbers, M. Material efficiency and global pathways towards 100% renewable energy systems–system dynamics findings on potentials and constraints. J. Sustain. Dev. Energy Water Environ. Syst. 2022, 10, 1100427. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Levesque, A.; Pietzcker, R.C.; Luderer, G. Halving energy demand from buildings: The impact of low consumption practices. Technol. Forecast. Soc. Change 2019, 146, 253–266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lettenmeier, M.; Wackernagel, M. Implications of the 1.5-degree target for lifestyles. Prog. Towards Resour. Revolut. 2019, 236, 43–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matthews, H.D.; Wynes, S. Current global efforts are insufficient to limit warming to 1.5 °C. Science 2022, 376, 1404–1409. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dean, J.G.; Stain, H.J. Mental health impact for adolescents living with prolonged drought. Aust. J. Rural. Health 2010, 18, 32–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Majeed, H.; Lee, J. The impact of climate change on youth depression and mental health. Lancet Planet. Health 2017, 1, e94–e95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clemens, V.; von Hirschhausen, E.; Fegert, J.M. Report of the intergovernmental panel on climate change: Implications for the mental health policy of children and adolescents in Europe—A scoping review. Eur. Child Adolesc. Psychiatry 2022, 31, 701–713. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hickman, C.; Marks, E.; Pihkala, P.; Clayton, S.; Lewandowski, R.E.; Mayall, E.E.; Van Susteren, L. Climate anxiety in children and young people and their beliefs about government responses to climate change: A global survey. Lancet Planet. Health 2021, 5, e863–e873. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thomas, I.; Martin, A.; Wicker, A.; Benoit, L. Understanding youths’ concerns about climate change: A binational qualitative study of ecological burden and resilience. Child Adolesc. Psychiatry Ment. Health 2022, 16, 110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sabherwal, A.; Ballew, M.T.; van Der Linden, S.; Gustafson, A.; Goldberg, M.H.; Maibach, E.W.; Leiserowitz, A. The Greta Thunberg Effect: Familiarity with Greta Thunberg predicts intentions to engage in climate activism in the United States. J. Appl. Soc. Psychol. 2021, 51, 321–333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schwartz, S.E.; Benoit, L.; Clayton, S.; Parnes, M.F.; Swenson, L.; Lowe, S.R. Climate change anxiety and mental health: Environmental activism as buffer. Curr. Psychol. 2023, 42, 16708–16721. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Costanza-Chock, S. Youth and social movements: Key lessons for allies. Berkman Cent. Res. Publ. 2012, 2013–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Azzopardi, A. Youth Activism: Social Movements in the Making or in the Taking? In Youth: Responding to Lives; Brill: Leiden, The Netherlands, 2013; pp. 45–56. [Google Scholar]

- Sanson, A.V.; Wachs, T.D.; Koller, S.H.; Salmela-Aro, K. Young people and climate change: The role of developmental science. In Developmental Science and Sustainable Development Goals for Children and Youth; Verma, S., Petersen, A., Eds.; Social Indicators Research Series; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2018; Volume 74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pereira, T.; Freire, T. Positive youth development in the context of climate change: A systematic review. Front. Psychol. 2021, 12, 786119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- The Nippon Foundation. Climate Change “Has an Impact on Life”—More Than Half of the Respondents Learned Through Their Studies That “It Is Not Clear” and This “Uncertainty” Decreased Among 18-Year-Olds in the Awareness Survey. The Asahi Shimbun: Tokyo, Japan; Osaka, Japan. 2025. Available online: https://www.asahi.com/sdgs/article/15833286 (accessed on 11 June 2025).

- Ministry of the Environment. (n.d.).; Environmental Education. Available online: https://www.env.go.jp/earth/coop/coop/document/08-ttmnce/08-ttmnce-6.pdf (accessed on 11 June 2025).

- Shaw, R.; Takeuchi, Y.; Shiwaku, K.; Fernandez, G.; Ru, Q.; Yang, B. 1-2-3 of Disaster Education. UNDRR. 2009. Available online: https://www.preventionweb.net/publication/1-2-3-disaster-eduction (accessed on 11 June 2025).

- Yildiz, A.; Shaw, R. Disaster and Climate Risk Education; Springer Nature: Singapore, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Aiken, L.S. Multiple Regression: Testing and Interpreting Interactions; Sage: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 1991. [Google Scholar]

- Cohen, J. Statistical Power Analysis for the Behavioral Sciences; Routledge: Abingdon, UK, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Burchell, K.; Rettie, R.; Roberts, T.C. Householder Engagement with Energy Consumption Feedback: The Role of Community Action and Communications. Energy Policy 2016, 88, 168–177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- IGES. IGES 1.5 °C Roadmap: An Action Plan for Japan—More Ambitious Emissions Reduction and a Prosperous, Vibrant Society; IGES: Hayama, Japan, 2023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hirth, S.; Kreinin, H.; Fuchs, D.; Blossey, N.; Mamut, P.; Philipp, J.; EU1. 5° Lifestyles Consortium. Barriers and enablers of 1.5° lifestyles: Shallow and deep structural factors shaping the potential for sustainable consumption. Front. Sustain. 2023, 4, 1014662. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goodman, A.; Sianesi, B. Early education and children’s outcomes: How long do the impacts last? Fisc. Stud. 2005, 26, 513–548. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Robertson, D.A.; Padesky, C.J. Keeping students interested: Interest-based instruction as a tool to engage. Read. Teach. 2020, 73, 575–586. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kollmuss, A.; Agyeman, J. Mind the gap: Why do people act environmentally and what are the barriers to pro-environmental behavior? Environ. Educ. Res. 2002, 8, 239–260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, C.; Fang, Z. The impact of education expenditure on environmental innovation. Heliyon 2024, 10, e32446. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, S.; Mbanyele, W.; Feng, T.; Fan, S. Bridging the knowledge-action divide: Environmental awareness and low-carbon behaviors of Chinese university students. Humanit. Soc. Sci. Commun. 2025, 12, 925. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Analytical Framework | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Literature Review | Japan’s responses to climate change. | |||||||

| The potential of 1.5-degree lifestyles in Japan. | ||||||||

| Youth perception of climate change. | ||||||||

| ➕ | ||||||||

| Questionnaire Data (KIDA Framework) | Key Feature | Objects | Knowledge | Interest | Desire | Action | Enablers | Barriers |

| Gender; Japanese/International students; Whether received environmental education | Individual | Are you aware of the concept of the 1.5-degree lifestyles? | To what extent do you understand the meaning and purpose of the 1.5-degree lifestyles? | To what extent do you want to learn about the 1.5-degree lifestyles? | Food Housing Mobility Consumer Goods Leisure and Services | Economic Political Technological Societal | Economic Political Technological Societal | |

| Family | ||||||||

| Community | ||||||||

| Correlation Analysis, Regression Analysis, and Questionnaire Analysis | Preferred List | |||||||

| ⬇️ | ||||||||

| Reflection/Recommendation | Individual | How to raise youth awareness of 1.5-degree lifestyles? How to effectively improve youth action change? | ||||||

| Family | ||||||||

| Community | ||||||||

| Results of Regression Analysis (n = 224) | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Unstandardized Coefficients | Standardized Coefficients | Collinearity Diagnosis | |||||||

| Model | B | Std. Error | Beta | t | p | VIF | Tol. | ||

| (Constant) | 1.224 | 0.592 | - | 2.1882 | 0.003 | - | - | ||

| Independent variable | Knowledge | Yes | −0.086 | 0.241 | −0.031 | −0.357 | 0.721 | 2.176 | 0.46 |

| No | 0.132 | 0.215 | 0.049 | 0.613 | 0.54 | 1.902 | 0.526 | ||

| Not sure | 0 | ||||||||

| Interest | 0.428 | 0.071 | 0.453 | 5.99 | 0 | 1.686 | 0.593 | ||

| Control variable | Gender | Female | 0.076 | 0.3 | 0.03 | 0.255 | 0.799 | 4.005 | 0.25 |

| Male | 0.334 | 0.313 | 0.124 | 1.068 | 0.287 | 3.987 | 0.251 | ||

| Non-binary | 0 | ||||||||

| Nationality | Non-Japanese | −0.332 | 0.172 | −0.119 | −1.933 | 0.055 | 1.115 | 0.897 | |

| Japanese | 0 | ||||||||

| Whether received environmental education | Yes, at university | 1.136 | 0.34 | 0.386 | 3.341 | 0.001 | 3.93 | 0.254 | |

| Yes, at high school | 1.014 | 0.336 | 0.357 | 3.021 | 0.003 | 4.117 | 0.243 | ||

| Yes, at middle school | 1.05 | 0.362 | 0.286 | 2.899 | 0.004 | 2.878 | 0.347 | ||

| Yes, at elementary school | 0.63 | 0.366 | 0.166 | 1.719 | 0.087 | 2.736 | 0.365 | ||

| No | 0 | ||||||||

| R2 | 0.278 | ||||||||

| F | 8.202 | ||||||||

| p | <0.01 | ||||||||

| Dependent variable: Desire | |||||||||

| Gender | Number of People | Knowledge (Awareness) | Interest | Desire | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Yes | No | Not Sure | 0–1 | 2–3 | 4–5 | 0–1 | 2–3 | 4–5 | ||

| Female | 127 (57%) | 45 (35.5%) | 49 (38.5%) | 33 (26%) | 57 (45%) | 55 (43%) | 15 (12%) | 15 (12%) | 64 (50%) | 48 (38%) |

| Male | 93 (42%) | 32 (34%) | 48 (52%) | 13 (14%) | 46 (49%) | 38 (41%) | 0 (0%) | 19 (21%) | 44 (47%) | 30 (32%) |

| Non-binary | 4 (1%) | 0 (0%) | 3 (75%) | 1 (25%) | 2 (50%) | 2 (50%) | 0 (0%) | 1 (25%) | 3 (75%) | 0 (0%) |

| Receive Environmental Education | Number of People | Knowledge (Awareness) | Interest | Desire | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Yes | No | Not Sure | 0–1 | 2–3 | 4–5 | 0–1 | 2–3 | 4–5 | |||

| Yes | At elementary school | 32 (14%) | 16 (50%) | 11 (34%) | 5 (16%) | 13 (41%) | 15 (47%) | 4 (12%) | 7 (22%) | 16 (50%) | 9 (28%) |

| At middle school | 35 (16%) | 14 (50%) | 12 (24%) | 9 (26%) | 15 (43%) | 15 (43%) | 5 (14%) | 4 (11%) | 17 (49%) | 14 (40%) | |

| At high school | 73 (32%) | 25 (34%) | 36 (49%) | 12 (17%) | 33 (45%) | 31 (43%) | 9 (12%) | 6 (8%) | 38 (52%) | 29 (40%) | |

| At university | 64 (29%) | 19 (30%) | 26 (40%) | 19 (30%) | 29 (45%) | 29 (45%) | 6 (10%) | 7 (11%) | 33 (51.5%) | 24 (37.5%) | |

| Total | 204 (91%) | 74 (36%) | 85 (42%) | 45 (22%) | 90 (44.5%) | 90 (44.5%) | 24 (12%) | 24 (12%) | 104 (51%) | 76 (37%) | |

| No | 20 (9%) | 3 (15%) | 15 (75%) | 2 (10%) | 15 (75%) | 5 (25%) | 0 (0%) | 10 (50%) | 8 (40%) | 2 (10%) | |

| Total | 224 (100%) | 77 (34%) | 100 (45%) | 47 (21%) | 105 (47%) | 95 (42%) | 24 (11%) | 34 (15%) | 112 (50%) | 78 (35%) | |

| p | Individual Action Change (Q50) | Family Action Change (Q51) | Community Action Change (Q52) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Gender | 0.95 | 0.724 | 0.677 |

| Nationality | 0.242 | 0.005 ** | 0.095 |

| Whether Ed. | 0.916 | 0.916 | 0.759 |

| Interest | 0.988 | 0.44 | 0.835 |

| Desire | 0.957 | 0.9 | 0.359 |

| Enablers | Barriers | |

|---|---|---|

| Individual |

|

|

| Family |

|

|

| Community |

|

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Huang, R.; Shaw, R. Youth Perceptions of 1.5-Degree Lifestyle to Adapt to Climate Change: A Case Analysis of Japanese University Students. Climate 2025, 13, 171. https://doi.org/10.3390/cli13090171

Huang R, Shaw R. Youth Perceptions of 1.5-Degree Lifestyle to Adapt to Climate Change: A Case Analysis of Japanese University Students. Climate. 2025; 13(9):171. https://doi.org/10.3390/cli13090171

Chicago/Turabian StyleHuang, Rong, and Rajib Shaw. 2025. "Youth Perceptions of 1.5-Degree Lifestyle to Adapt to Climate Change: A Case Analysis of Japanese University Students" Climate 13, no. 9: 171. https://doi.org/10.3390/cli13090171

APA StyleHuang, R., & Shaw, R. (2025). Youth Perceptions of 1.5-Degree Lifestyle to Adapt to Climate Change: A Case Analysis of Japanese University Students. Climate, 13(9), 171. https://doi.org/10.3390/cli13090171