To delineate the complex interlinkages of ESG more clearly, disaster risk, and social inequality, our research divides the literature review into four sub-sections. Each sub-section canvases existing studies featuring one of the pairwise interlinkages—ESG and disaster (

Section 4.1), ESG and inequality (

Section 4.2), and disaster and inequality (

Section 4.3)—before moving to the triple nexus of the three dimensions (

Section 4.4). This structure will allow us to orderly trace the progression of academic debates along a wide range of interlinkages, identify where research has been comparatively mature, and highlight where gaps remain substantial. Through this stepwise procedure, we aspire to establish a clear foundation for understanding how ESG frameworks may facilitate equity-oriented disaster resilience and systematize where integration of the three domains is still lacking. The qualitative synthesis in

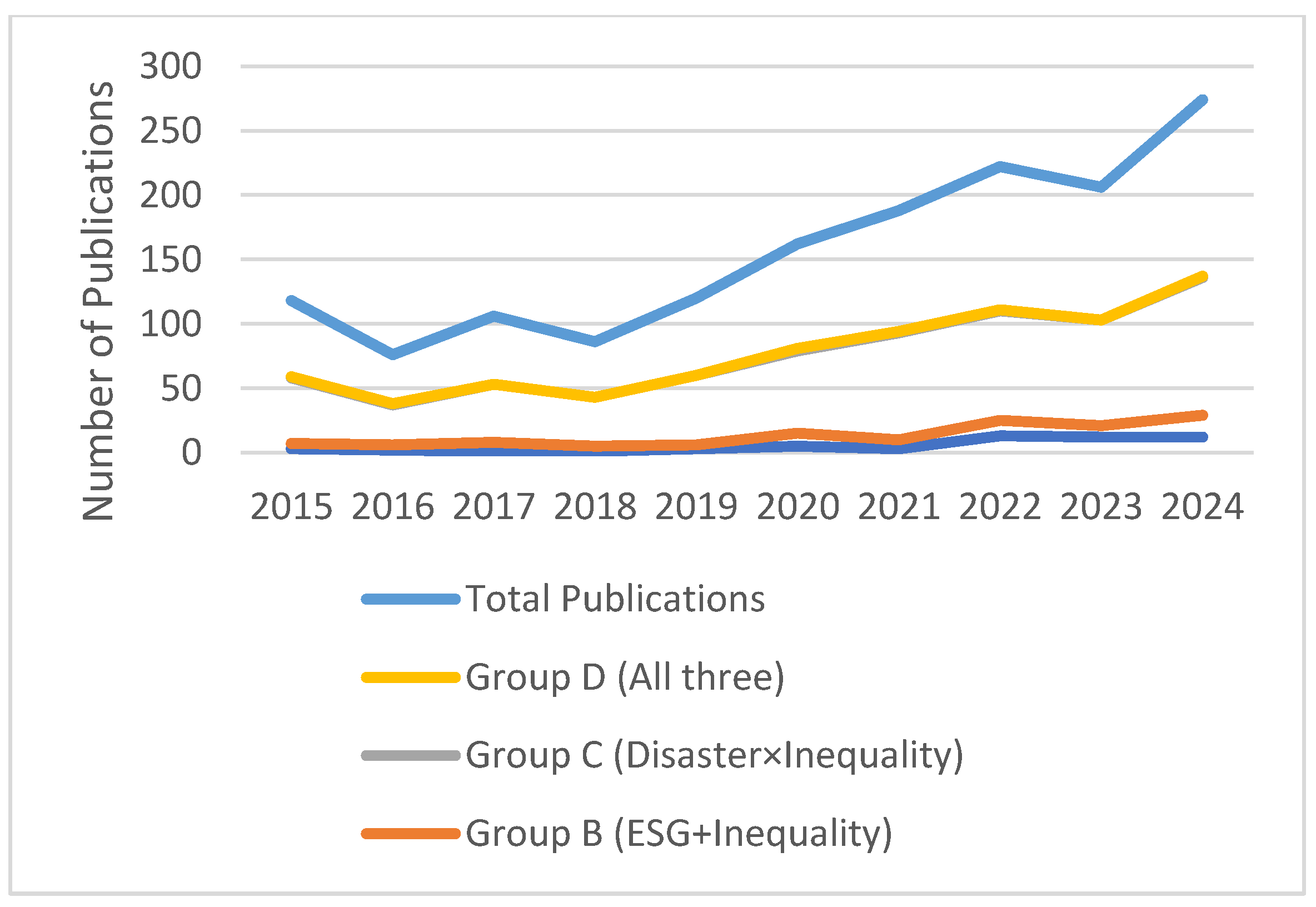

Section 4 builds directly on the bibliometric clusters identified in

Figure 3, where Motor Themes (ESG and Risk Disclosure), Niche Themes (Climate–Health Nexus), and Emerging Themes (Social Vulnerability and Equity) structure the subsequent discussion.

4.1. ESG and Disaster Risk: Insights and Gaps

The Environmental, Social, and Governance (ESG) framework was initially designed as a tool to assess corporate sustainability and transparency, primarily applied in investment and managerial contexts. As global climate change has led to more frequent extreme weather and natural disasters, the pressure on enterprises and society in risk management has intensified, and disaster risk—external and beyond managerial control—has gradually entered the ESG discussion. This is because disaster risk not only disrupts corporate assets and operational continuity but also affects investor confidence and social trust. Examining disaster risk within the ESG framework therefore offers new perspectives for corporate sustainable management and external communication.

To ensure evidentiary strength and comparability, this study employs empirical methods (e.g., event studies, panel regressions, and difference-in-differences) to analyze corporate ESG performance, risk disclosure, market reactions, and governance changes under natural disasters or extreme climate events, while maintaining diversity and representativeness in disaster types, industries, and regions. Within a unified framework, we focus on carbon disclosure and adaptation under the Environmental (E) dimension, climate governance and the embedding of disaster policy under the Governance (G) dimension, infrastructure, supply-chain resilience, and resource allocation, the actual degree of integration of disaster risk management into sustainability reporting and the applications and limitations of ESG tools across different disaster contexts. Overall, variation in ESG–disaster performance can be traced to firm-level preparedness, sectoral exposure, and regulatory density. Companies operating in hazard-prone industries tend to develop more advanced governance mechanisms, while those with weaker disclosure obligations show symbolic compliance. These findings suggest that national regulatory environments and disaster histories play a decisive role in shaping the depth of ESG–disaster integration, explaining the heterogeneity observed across cases.

Under the Environmental (E) dimension, ESG not only drives emissions-reduction policies and investments in disaster prevention and mitigation, but also requires adaptive strategies to enhance community disaster resilience in the face of extreme events induced by climate change such as floods, typhoons, and earthquakes. Liu et al. [

7] show that firms with stronger ESG performance exhibited greater organisational resilience during an extreme heat event, underscoring the role of ESG in adapting to climate-related hazards. A study of Chinese listed firms on the short-, medium-, and long-term impacts of earthquakes on corporate ESG performance finds that, in the short term, environmental and social performance improve, whereas in the medium to long term, social and governance performance improve [

8]. This suggests that, in the aftermath of disasters, firms initially channel resources toward environmental restoration and adaptation to resume production and respond to external scrutiny. Using China’s 2022 extreme heat as the empirical setting, another study shows that firms with higher ESG ratings displayed stronger market resilience following the event, with effects more pronounced among non-state-owned enterprises and firms in low-carbon pilot cities. This indicates that, under differing policy environments, adaptive actions on the environmental dimension can amplify ESG’s positive buffering effect against disaster shocks. Collectively, these findings suggest that post-disaster investment and recovery actions related to carbon disclosure and adaptation should place greater emphasis on building long-term environmental resilience—e.g., green infrastructure investment, ecosystem restoration, and low-carbon technology adoption—which not only mitigates firms’ post-disaster adverse impacts but also strengthens the broader community’s adaptive capacity.

On the other hand, the Governance (G) dimension is equally crucial in disaster contexts. Disasters often expose vulnerabilities in corporate governance, primarily in terms of information transparency and institutional improvement. Evidence from U.S. firms located near disaster zones shows that, post-disaster, these firms significantly increase the transparency of ESG disclosures, especially on social and governance topics [

9]. Such changes are not necessarily driven by intrinsic aspirations to improve governance; rather, they are often responses to investor demand, with managers adjusting ESG disclosures in line with shifts in investor risk perceptions—thus leading to governance information improvements under external pressure. By contrast, the case of the Morandi Bridge collapse in Italy shows that corporate ESG disclosure policies did not change significantly; the structure and content of reports evolved only marginally as part of routine progression, rather than as a systematic response to the disaster [

10]. This contrast indicates heterogeneity in post-disaster governance responses—ranging from passive increases in transparency to inertia in maintaining the status quo. Moreover, firms with more mature governance structures tend to make more proactive E and S responses when facing disaster and climate risks, reflecting that governance effects are often time-lagged and context-dependent; over the medium to long term, they gradually improve through adjustments to organizational processes and accountability structures. Consequently, assessments of the G dimension should not stop at quantifying disclosure outcomes; they should examine whether firms possess effective risk-governance mechanisms. Furthermore, existing research focuses more on post-disaster disclosure and governance responses, while paying less attention to pre-disaster prevention (e.g., risk investments, mitigation infrastructure) and mid-disaster response (resource allocation and supply-chain resilience). Disaster risk should be embedded in board and management decision-making processes, with effective communication mechanisms established for employees, investors, and communities. Regulators and firms should jointly adopt disaster-scenario disclosure checklists and promptly update them after major events so that ESG can truly contribute to resilience building in disaster contexts.

Infrastructure, supply-chain resilience, and resource allocation are core issues in responding to disaster risk, yet research remains limited. In manufacturing, Hsu [

11] finds that companies with higher levels of Corporate Social Responsibility (CSR) suffer smaller post-disaster performance losses, primarily via mechanisms of employee motivation and customer loyalty. This suggests that, even when supply chains are impaired, long-term investments in the S and G dimensions can facilitate faster recovery. At the urban scale, flood-resilience frameworks emphasize that only the integration of E (green infrastructure), S (social inclusion and infrastructure development), and G (transparent decision-making) can effectively address disasters; coordination between medical emergency services and transportation is also considered critical for resource allocation. From a sustainability-reporting perspective, whether disaster risk management is truly embedded in governance arrangements is equally crucial. Existing research suggests that merely mentioning disaster risks in reports is insufficient; what matters is institutionalization in practice. For example, explicitly disclosing targets and responsibilities for business continuity planning, recovery times for infrastructure and information systems, scenario analysis for major disasters, and early-warning and data-monitoring mechanisms all evidence substantive ESG-based resilience capabilities—helping firms maintain internal governance under disaster shocks while providing stronger trust foundations for employees, investors, and communities.

Regarding the role of ESG tools in disaster contexts, existing findings diverge across disaster scenarios. During COVID-19, firms with higher ESG scores performed more steadily, indicating that ESG information has some predictive power for long-term resilience. Conversely, in the face of catastrophic events, retail investors’ ESG awareness and preferences increased, yet short-term (five-day) returns were negative [

12]. This suggests that, amid market uncertainty, ESG is treated as a risk proxy after disasters, but realized returns do not align. In addition, Naffa [

13] finds that firms’ ESG management scores are negatively correlated with market performance during crises, hinting at a possible mismatch between ESG management levels and actual financial resilience. Therefore, the performance of ESG tools in disaster settings is jointly shaped by disaster type, time horizon, and regional context. For example, Adrian et al. [

14] examine how drought-related natural disasters influence corporate tax avoidance behaviour, showing that disaster shocks can reshape firms’ fiscal strategies beyond formal ESG commitments. Firm-level evidence also suggests that disaster experience heightens risk salience and leads managers to expand ESG disclosure, especially regarding environmental and social performance [

15].

Overall, although the role of ESG in disaster risk governance has attracted increasing attention, current research and practice remain insufficient. First, ESG disclosure and governance responses are largely concentrated in the post-disaster phase, with limited emphasis on pre-disaster prevention and resource allocation during the crisis, resulting in a resilience framework that lacks foresight. Second, corporate ESG performance in the context of disasters often shows short-term positive effects but diminishes in the medium to long term, indicating that ESG investment lacks sustained commitment in post-disaster recovery, particularly in extending from environmental restoration to systematic governance reform. Finally, the effectiveness of ESG tools varies across disaster scenarios: while positive buffering effects have been observed during pandemics or extreme heat events, there are also cases where ESG performance is misaligned with financial resilience in catastrophic events, reflecting the inadequacy of current ESG indicators in adapting to diverse disaster types and regional contexts.

4.2. ESG and Social Inequality: Corporate Responsibility and Equity Challenges

Environmental, Social, and Governance (ESG) reporting standards—such as the IFRS Sustainability Disclosure Standards IFRS S1

General Requirements for Disclosure of Sustainability-related Financial Information and IFRS S2

Climate-related Disclosures—have turned corporate responsibility from voluntary giving to standardized disclosure and investor stewardship [

16,

17]. Unlike CSR, which emphasizes moral responsibility and stakeholder legitimacy, ESG converts social and environmental values into quantifiable indicators that attract investor scrutiny. Classic CSR scholarship has long documented the structural challenges and constraints firms face when trying to integrate social responsibility into competitive markets [

18], which helps to explain why ESG implementation often falls short of its equity promises. One the one hand, this change democratizes sustainability evaluation. On the other hand, this shift risks narrowing the normative scope of corporate responsibility to what can be measured. Thus, ESG can be understood as the institutional codification of CSR ideals through the logic of market accountability. Compared to traditional CSR, ESG promises clearer measurement and market discipline but risks privileging what is easy to measure at the expense of the more socially valuable ones [

19]. New controversies thus center on whether ESG diminishes inequality—through equal pay and safer workplaces and transparent governance—or strengthens it through privileging resource-rich firms and regions. This review synthesizes evidence across three mechanisms that connect ESG and inequality: [

1] protections of labour and wage fairness; [

2] governance transparency and managers’ time horizons; and [

3] environmental initiatives and green finance. It also analyses structural frictions—rating divergence, metrics bias, and symbolic adoption—that blur the distributive impacts of ESG.

Recent literature also explores ESG’s relationship with inclusion and labor ethics, emphasizing workforce diversity, wage fairness, and social disclosure as equity indicators. Studies show that firms with inclusive governance exhibit higher resilience in post-disaster recovery, bridging the ESG–Inequality nexus.

While ESG has emerged as a dominant framework for corporate accountability, scholars note tensions between its financial and social logics. The symbolic adoption of ESG can itself be a legitimacy strategy, which deflects responsibility without changing practices substantively. These practices pose the risk of channeling attention away from regulatory enforcement and may perpetuate inequality themselves. Recent research distinguishes between instrumental ESG-driven by investor risk concerns-and normative ESG-anchored in justice and equity objectives. Recognition of this tension sheds light on why responses from ESG to disasters and inequalities remain patchy across sectors and regions.

First of all,

ESG’s Social pillar focuses on labour rights, workplace safety, inclusion, and fair pay—key levers to reducing both within-firm and economy-level inequality. But social outcomes depend on firms making meaningful changes rather than associative claims. In the garment business, where unequal value capture has been supported by exploitation of labour for centuries, experimental and survey evidence show that intangible, image-oriented announcements of labour-related CSR activities decrease credibility and trust, but verifiable, tangible commitments (such as living-wage policies and disclosure of third-party audits) improve evaluations and perceived legitimacy [

20]. That is, superficial ESG disclosure does very little to benefit the lives of workers; improvement takes place when policies actually raise wages, expand bargaining power, and improve safety.

At the level of the global value chains, research on “social upgrading” highlights that fairness gains to labour and small producers depend on governance structures that direct value downstream [

21]. Modelling work by Cao et al. [

22] further shows that collaborative ESG due diligence between buyers and suppliers can reduce responsibility gaps and distribute compliance costs more fairly along the supply chain. Supplier development, long-term contracts and credible monitoring improve the likelihood that ESG standards help generate higher and more stable incomes for vulnerable participants, rather than concentrating rents at the top. This is in line with investor-facing evidence: market actors emphasize financially material ESG issues [

19], that would marginalize complex, qualitative aspects of the dignity of work unless measurable and calculable (e.g., wage disclosure, accident rates). The literature implies that ESG’s “S” reduces inequality when it focuses on verifiable improvements in pay, safety and inclusion—and when purchasers and investors reward them rather than glossy narratives.

The Governance pillar defines distributional outcomes by restricting rent extraction, enhancing oversight, and extending time horizons. Evidence from Chinese bond markets indicates that stronger corporate social responsibility can improve firms’ access to unsecured debt financing, suggesting that lenders increasingly treat CSR as a form of risk mitigation [

23]. A classic quasi-experimental paper demonstrates media scrutiny can discipline corporate abuse: companies subject to international media coverage were more likely to correct governance transgressions, acting through reputational and regulatory mechanisms [

24]. Such “targeted transparency” mechanisms are reflected in sustainability reporting reforms. With a multi-country policy shock, a study discovers that compulsory corporate sustainability reporting fortifies internal controls and raises socially responsible management behaviors—such as employee training—with possible wage growth and safety spillovers [

25]. These outcomes suggest disclosure can shift managerial attention from the short-term bottom line to long-horizon investment which matters for social welfare.

Similar research demonstrates why the shift is necessary: short-termism constrains investment in intangibles with social returns (skills, safety, community assets). While policies and shareholder stewardship that concentrate on multi-year horizons (e.g., long-term pay, active ownership) are associated with superior environmental and social outcomes [

19]. The takeaway is that the “G” is more than a compliance add-on; it is the mechanism by which companies internalize stakeholder demands, reduce self-enrichment, and allocate resources to programs most beneficial for inequality.

Environmental pillar of ESG intersects with inequality because environmental harms disproportionately affect low-income communities, and green investment can create local co-benefits such as clean air, resilient infrastructure, eco-jobs. Corporate finance studies find that green bonds can shift firms’ capital allocation: issuers of green bonds increase environmental investment and environmental performance after the issue, consistent with restrictions on the use of proceeds and investor monitoring [

26]. These mechanisms could plausibly support equity when environmental advantages come where the harms are most focused, and projects take a thoughtful job-quality and community approach.

However, the sharing of green capital and compliance costs is important. Without inclusive design, strict standards and reporting burdens can favor big companies and exclude SMEs and smallholders from premium markets—creating a risk of a two-level economy. Literature of the “just transition” hold that government and corporate action to mitigate and adapt to climate change must accompany worker retraining and community benefit to avoid regressive outcomes [

27]. In the supply chain, social upgrading scholarship warns again that sustainability standards can raise producers up or leave them behind depending on whether purchasers invest in capability up-grading [

21]. In reality, the implication is that greening procurement and finance must make access dependent not only on environmental indicators but also on social co-benefits that can be tested and measured (local job creation, wage minimums, safety), and hence aligning E and S.

However, even when firms act in good faith, system-level frictions can dilute the equity effect of ESG. Firstly, ESG rating variation is large: scope, metric, and weighting variation between providers induces “aggregate confusion,” weakening the relationship between scores and actual performance and enabling firms to look “good” on one rating but neglecting social substance [

28]. Secondly, investors’ demand for comparable, numeric indicators may lead attention to move from challenging qualitative social issues (e.g., freedom of association) to easy metrics (e.g., carbon intensity) unless robust social metrics emerge [

19]. Thirdly, firms may engage in symbolic ESG—policy and disclosure but no actual operational change—most notably in reputationally vulnerable industries; evidence from fashion demonstrates that stakeholders spot that type of symbolism and punish credibility and leave inequality unaddressed [

20].

The literature supports conditional optimism: ESG reduces inequality when governance reform broadens the horizons of management and enforces accountability [

25], when environmental finance is associated with enforceable use-of-proceeds and with social co-benefits at the local level [

26], and when the social pillar is centered on verifiable improvements in workers’ remunerations, safety, and inclusion [

20,

21]. To deliver that promise, three design priorities keep recurring. First, improve the measurability of social outcomes (e.g., disclosure of the living wage, rates of injury, worker voice indexes) to allow investors to reward substance rather than signaling [

19]. Second, reduce rating confusion through the explanation of scopes and weights and through the prioritizing of impact-relevant indicators [

28]. Third, embed in green finance and procurement just-transition principles and supplier capability-building so that SMEs and weaker communities are not excluded from the sustainability dividend [

21,

29]. With these inclusions, ESG becomes not a box-ticking but an institutional connection between corporate strategy and social equity.

ESG–inequality outcomes are different because of institutional pressures and ownership structures. Firms embedded in stakeholder-oriented systems show stronger social inclusion commitments. In contrast, shareholder-dominated models emphasize disclosure over redistribution. Cross-country contrasts further indicate that labor and welfare regimes mediate whether ESG policies genuinely reduce inequality or merely enhance corporate reputation.

4.3. Disasters and Social Inequality: Vulnerability and Recovery Gaps

Disasters, whether triggered by natural hazards or human-made crises, do not affect all populations equally. Instead, they interact with pre-existing social vulnerabilities, such as gender, age, disability and migration status, thereby amplifying inequalities and undermining equitable recovery [

30,

31,

32]. Studies have shown that recovery trajectories differ significantly across social groups, often leaving marginalized populations further behind [

30,

32,

33,

34]. Seven key areas of social vulnerability emerge: infrastructure, education, disability, ethnicity, age, gender and economic status.

Despite global policy frameworks such as the Sendai Framework for Disaster Risk Reduction 2015–2030 [

35] emphasizing inclusivity, equity in recovery remains underdeveloped in practice. Recovery programs often prioritize efficiency and economic metrics while neglecting socially differentiated needs. Furthermore, Environmental, Social and Governance (ESG) frameworks, which are increasingly being adopted by corporations, rarely incorporate indicators that reflect social equity in disaster recovery.

This section builds on the identified gaps in recovery practices, such as the neglect of social groups, the lack of differentiated tracking, and the blind spots of ESG frameworks, before advancing policy recommendations. Drawing on recent scholarship and existing policy frameworks, it makes the case for the institutionalization of equity-centered recovery mechanisms.

The reviewed studies reveal that post-disaster inequalities persist not only because of uneven exposure but also due to institutional and governance asymmetries. Jurisdictions with participatory recovery mechanisms achieve more equitable outcomes than centralized systems. This explains why disaster responses in high-capacity welfare states reduce vulnerability faster, while market-oriented contexts reproduce pre-existing inequalities.

4.3.1. Neglect of Gender, Age, Disability, and Migrant Needs

Infrastructure and social vulnerability. Communities with poor infrastructure, particularly those in marginal areas close to bodies of water, face heightened risks. For example, block-level studies in China revealed that densely populated, low-income neighborhoods were disproportionately susceptible to the impacts of urban flooding due to inadequate infrastructure [

36]. Similarly, research in Brazil showed that households in areas with weaker infrastructure were more vulnerable to prolonged power outages [

37].

Education plays a dual role in vulnerability. On the one hand, disaster preparedness education increases awareness and adaptive capacity. Conversely, lower educational attainment correlates with a greater impact of disasters. For example, riverine communities in Bangladesh with lower levels of education experienced more severe losses during flooding, as knowledge gaps limited their ability to cope [

33].

Both physical and mental disabilities can increase vulnerability. People with disabilities often encounter communication barriers in warnings and mobility issues during evacuations. Martins et al. [

38] emphasize that disaster management frameworks which overlook disability perpetuate inequality rather than building resilience.

Ethnic minorities, migrants, the elderly and children are consistently identified as high-risk groups. New immigrants often encounter language and documentation barriers when trying to access aid, while elderly populations frequently lack mobility or consistent medical care [

39,

40]. Studies of drought in India reveal that marginalized caste and ethnic groups have slower recovery trajectories, demonstrating the intersection of social stratification and disaster exposure [

41].

The impact of disasters on different genders is acute. Evidence from earthquakes suggests that more women than men die in these catastrophes, with the gender gap widening in events of high magnitude. Zapata-Franco and Vargas-Alzate [

42] show how integrating gender perspectives into seismic risk assessment in Colombia can redirect resilience planning toward more equitable outcomes, illustrating what such integration could look like in practice. Furthermore, relief distribution often fails to consider women’s specific needs, with hygiene and feminine products frequently omitted from emergency aid packages. Qu [

34] further highlights that women bore a disproportionate share of the caregiving and economic burdens during the crisis caused by the COVID-19 underscoring how crises reinforce gender inequality. In many countries, women are expected to care for and protect children, the elderly, and the family home. This hinders their ability to rescue themselves in the event of a natural disaster [

43]. For instance, women’s unpaid caregiving responsibilities escalated during the UK’s response to the 2020–2021 pandemic, exacerbating existing gender inequalities [

34].

Poverty remains a key vulnerability factor. Families with limited financial resources find it more difficult to rebuild their livelihoods after disasters. Spatial analyses in Brazil and Bangladesh demonstrate that households with low incomes located near rivers or on marginal land are most exposed and experience the longest recovery periods [

33,

37].

Taken together, these seven dimensions demonstrate that disaster vulnerability is socially constructed and multidimensional. Effective policy responses must therefore incorporate equity considerations into preparedness and recovery planning to prevent any group from being systematically disadvantaged.

4.3.2. Lack of Differentiated Tracking

Recovery monitoring mechanisms usually focus on aggregate statistics, such as GDP growth, housing reconstruction and restored infrastructure. However, these metrics can obscure the unequal pace of recovery experienced by different groups. For example, spatial analyses of drought recovery in West Bengal reveal the differential vulnerability of marginalized populations, demonstrating that recovery cannot be understood without social disaggregation [

41]. Similarly, studies of urban flooding demonstrate that analyses at the level of individual blocks can reveal disparities in exposure and recovery [

36].

ESG reporting has become central to how corporations and financial institutions demonstrate accountability in disaster contexts. However, ESG systems primarily focus on environmental impact, compliance, and governance structures. They rarely measure whether socially marginalized groups benefit equitably from recovery investments.

For example, resilience research emphasizes that community-engaged, equity-centered approaches are critical to sustainability [

44], yet these outcomes are absent from standard ESG metrics. Consequently, corporations may claim “resilient recovery” by restoring business continuity without addressing disparities among workers, contract laborers, or low-income households.

4.4. Integrating ESG, Disaster, and Inequality: Toward an Equitable Resilience Framework

Environmental, Social, and Governance (ESG) frameworks have emerged as key instruments in measuring corporate sustainability and guiding responsible investment. Originally designed to help firms internalize environmental externalities and improve corporate governance, ESG frameworks are increasingly expected to play a broader role in advancing societal resilience. However, their capacity to respond effectively to climate-related disasters, particularly in ways that count for underlying social inequalities, remains limited. This section explicitly connects the Motor, Niche, and Emerging clusters from

Figure 3 to demonstrate where conceptual fragmentation occurs across ESG scholarship.

Disasters disproportionately impact vulnerable populations, such as those with lower income, insecure housing, or existing marginalization. However, these factors are often excluded from ESG evaluations. While climate change is now central to many ESG disclosures, the intersection between disaster risk, environmental vulnerability, and social inequality remains critically under-addressed. The following discussion examines the integration gaps across these domains and outlines systemic policy interventions to reposition ESG as a tool for equitable climate resilience.

Figure 3’s thematic clusters illuminate where integration failures occur. For example, the

Health Inequities cluster remains disconnected from

ESG discussions, reflecting a disciplinary gap between public-health and corporate-finance research. Similarly, the

Social Vulnerability cluster aligns weakly with

Climate Risk Disclosure, indicating that equity dimensions are often omitted from climate-finance models. Addressing these divides requires cross-disciplinary frameworks that merge ESG reporting metrics with social-justice indicators.

A review of recent academic work reveals that while each of these domains—ESG, disaster response, and social inequality—has received individual attention, studies addressing their intersection are rare and fragmented. For example, Pagano et al. [

45] explore how traditional insurance mechanisms fail to adequately protect vulnerable populations from natural hazards. Their study, based on the Italian insurance context, demonstrates how information asymmetries between insurers and clients, especially regarding exposure and vulnerability, contribute to inequality in coverage. They suggest using ESG-aligned risk models to design more inclusive insurance policies, marking one of the few attempts to explicitly connect ESG mechanisms to both disaster risk and social equity.

Similarly, Owen et al. [

46] examine catastrophic tailings dam failures and the lack of transparent disaster risk disclosure in the global mining sector. Their study emphasizes the importance of “situated risk,” a concept that captures both the physical hazard and the social vulnerability of surrounding communities. They argue that ESG disclosures should not simply account for environmental or technical risks but must also consider land use conflicts, indigenous rights, and political fragility, which are typically neglected in standard ESG reporting.

Huyck et al. [

47] contribute to the discussion by introducing the Global Economic Disruption Index (GEDI), a tool designed to assess disaster-induced economic downtime. Although the GEDI framework includes ESG applications in theory, it is primarily used for evaluating supply chain continuity and financial resilience, rather than community-level social recovery. As such, it lacks integration with equity-oriented disaster metrics.

Other case studies further illustrate the disconnect between corporate ESG commitments and local disaster realities. In Diepsloot, South Africa, Bopape et al. [

48] highlight efforts by private companies to build disaster resilience in informal settlements. In the casino sector, Guan et al. [

49] show that post-disaster CSR reactions and disclosures are often driven by reputational pressure rather than by structural redistribution, reinforcing this disconnect. However, these efforts are framed through Corporate Social Responsibility (CSR) initiatives rather than formal ESG structures, making them vulnerable to fragmentation and inconsistent implementation.

A synthesis of the literature reveals three critical integration failures that limit the ability of ESG frameworks to meaningfully engage with disaster risk in a socially equitable way. These gaps are not merely technical oversights but structural deficiencies in how ESG frameworks are conceptualized, measured, and applied.

4.4.1. Fragmentation Across ESG Dimensions

In most ESG frameworks, the environmental, social, and governance pillars are treated as discrete domains rather than overlapping systems. At the sovereign level, Hasegawa et al. [

50] demonstrate how ESG evaluations are incorporated into market risk management for government bond investments, yet these metrics are rarely linked explicitly to disaster vulnerability or social inequality. Similarly, Helliar et al. [

29] map ESG risk exposures across mutual funds, but these portfolio-level measures seldom incorporate granular indicators of disaster vulnerability or distributional impacts on affected communities. Risk assessments typically isolate environmental exposure, such as flood zones or extreme heat, without factoring in the social vulnerabilities that determine the actual impact on affected communities. For instance, a company might disclose exposure to rising sea levels without acknowledging that its facilities are adjacent to informal settlements that lack drainage, insurance, or legal protection. This separation results in incomplete risk modeling and a failure to account for compounding effects.

The lack of intersectional data is a central barrier. Environmental disclosures may include carbon emissions or biodiversity impacts, but rarely contain indicators for displacement risk, income insecurity, or housing informality. As Huyck et al. [

47] suggest, economic disruption indices have potential ESG applications, yet they are still skewed toward asset loss and business continuity rather than community-level harm. This technical separation sustains a false sense of resilience, especially in low-income geographies.

4.4.2. Insufficient Attention to Post-Disaster Inequality

ESG frameworks often emphasize risk avoidance and disclosure prior to disasters, but they fail to account for how inequalities intensify during the recovery phase. Post-disaster vulnerability, such as unequal access to aid, exclusion from insurance, or forced displacement, is rarely addressed in ESG ratings or investor assessments. This results in a narrowed understanding of resilience focused on infrastructure and continuity rather than human outcomes.

Battikh et al. [

51] offer a striking example in their analysis of disaster response by ICT multinational corporations. Despite the global scope of these firms, their disaster aid is overwhelmingly concentrated in developed countries, with a declining share of support directed toward high-vulnerability developing regions. The geographic and economic biases embedded in these response patterns underscore how ESG mechanisms are still governed by investor proximity rather than vulnerability metrics. Without incentives to prioritize equitable recovery, ESG remains disconnected from actual disaster justice.

This underrepresentation suggests that ESG research has yet to evolve from firm-level resilience to system-level equity. Incorporating social vulnerability metrics into ESG disclosure could bridge this gap. Furthermore, it could help to transform ESG from a financial signal into a governance mechanism for equitable resilience.

4.4.3. Underdevelopment of Measurable Social Indicators

Among the three ESG components, the “S” remains the most ambiguous and underdeveloped. While companies are increasingly reporting on diversity, labor rights, and stakeholder engagement, there is no standardized approach to measuring how these factors intersect with disaster contexts. Metrics for displacement, informal housing conditions, or gendered vulnerability are absent in most ESG scorecards. The result is a symbolic or tokenistic treatment of social equity.

McDaniel et al. [

52] demonstrate how corporate social responsibility narratives can be strategically deployed for reputation management, especially in politically sensitive industries such as tobacco. A similar concern arises in disaster contexts. ESG-aligned firms may emphasize environmental compliance while downplaying harmful social impacts, particularly those related to marginalized populations. Without enforcement mechanisms or third-party validation, the “S” remains a narrative tool rather than a governance instrument.