Annual Solar Geoengineering: Mitigating Yearly Global Warming Increases

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Methods and Data

2.1. Overview of the ASG Approach

2.2. ASG Temperature Reversal Estimate

2.3. Theory

- The reverse forcing of the target SRM area required is denoted by . We note that three things happen in SRM: (1) we increase the albedo reflectivity of a hotspot surface target, causing a reverse forcing of ; (2) this also reduces its associated greenhouse gas re-radiation background climate effect since there are fewer long wavelengths emitted from the SRM area, which means a reduction in re-radiation; and (3) there is also a reduction in water vapor GHG feedback due to the cooling of the hotspot target. Other feedback may also show some reversal.

- In this equation, we assume that feedback, which is dominated by water vapor, will also reverse as part of the background climate cooling effect. That is, SG reverse forcing causes a cooling effect and cooler air holds less water vapor. In Equation (4), the average feedback amplification factor, including water vapor feedback, is estimated in 2019 as [28,30]—see also Appendix D for the conversion to feedback units. We note that many other authors have anticipated that water vapor feedback likely has a doubling effect [31,32], so a factor of 2.15 is reasonable. Note that this value can be written with temperature dependence, and this is discussed in Appendix A.

2.3.1. SG Advantage and the Greenhouse Gas Equivalent Reduction from SRM

2.3.2. SRM Area Estimates for Annual Solar Geoengineering

- This SG physics-based equation indicates that in SRM, as anticipated, the reversal is proportional to the average solar energy over 24 h and is given by .

- The fractional albedo SRM target area change required is denoted as AT. This change is taken relative to the Earth’s area AE.

- The amount of irradiance Xc falling on the target has a global average of [29] of sunlight passing through the clouds. This can vary depending on the location. This value can be changed in the model depending on the target’s location.

- The amount of outgoing reflected transmission from the target is denoted by . This is primarily used in albedo Earth brightening applications (see Section 3.1). This is just the amount of reflected sunlight from Earth brightening that is anticipated to make it into outer space due to potential issues such as clouds and aerosol particulates. A Bayesian probability estimate for this value is provided in Section 3.1.

- The space irradiance factor denoted by (see Section 3.2) is typically 1 for non L1 space mirror applications. However, for L1 space mirror applications, the optimal L1 point rotates around the Sun with the same angular speed as the Earth, thus allowing constant sunshading. Then, the sunshading irradiance occurs 24 h a day and the Earth’s curvature is not a factor. This increases So/4 to So. To account for the increase in space irradiance, we can let XS = 4 in Equation (7) for L1 space mirror applications.

- The albedo change of the target is denoted as , where the target’s albedo originally has a value of , and when we apply an SRM, its albedo increases to a new value denoted by .

- Lastly, included is an UHI de-amplification factor . This is for targets in urban heat island (UHI) areas which can have UHI microclimate de-amplification effects, denoted by HT [2,33,34]. For example, in UHIs, the solar canyon effect amplifies warming when buildings reflect light onto pavements, increasing the irradiance and amplifying the temperature at the surface. Other amplification issues can include re-radiation due to the increase in local CO2 GHGs, local water vapor feedback, temperature inversions, loss of wind and evapotranspiration cooling, increases in the solar heating of impermeable surfaces from building sides, pavements heat fluxes, and so forth [2]. Some of these microclimate amplification effects could reverse and de-amplify in ASG urban applications, increasing cooling, and can be accounted for in Equation (7) with the HT variable. City heat flux amplification is often observed by the UHI’s dome and footprint. The footprint and dome growth are indications of amplified heat flux that is observed to spread beyond the boundaries of the city itself, both horizontally and vertically [2,34,35]. Using ASG, the footprint, dome effects, and city temperatures can be reduced.

3. Results

3.1. Earth Brightening Transmission Loss

3.1.1. Pavement and Roofs

3.2. L1 Space Sunshade Estimates

3.3. Annual Stratospheric Injection Estimates

3.4. Overview of Estimates

3.5. RCP ASG Cumulative Area Estimates

4. Discussion

4.1. Annual Solar Radiation Management

4.1.1. Annual Solar Geoengineering Allocation by Country

- The US’s mitigation = 31% × 120,158 mi2 = 37,249 mi2/Yr or 102 mi2/day

- The UK’s mitigation = 3.5% × 120,158 mi2 = 4205 mi2/Yr or 11.5 mi2/day

4.1.2. Implementation Using L1 Space Particle Clusters

4.1.3. Earth Brightening Advances

- The US’s mitigation goal for Earth brightening is 102 mi2/day

- The UK’s mitigation goal for Earth brightening is 11.5 mi2/day

- For the US’s mitigation goal, about 102 drones/day

- For the UK’s mitigation goal, about 12 drones/day

4.1.4. Natural Hotspots

- Flaming Mountains, China

- Bangkok in Thailand (the planet’s hottest city)

- Death Valley, California

- Deserts

- The badlands of Australia

- The tropics and subtropics

4.1.5. ASG Methods Rated with Mixed Planning

4.1.6. Worldwide Negative Solar Geoengineering

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| Symbols | Description of General Terms |

| ASG | Annual solar geoengineering: mitigation of yearly global warming increases |

| CDR | Carbon dioxide removal |

| GCM | Global circulation model |

| GHG | Greenhouse gas |

| GW | Global warming |

| LW | Long wavelength |

| MSAT | Mean surface air temperature: Usually at a height of two meters |

| RCP | Representative concentration pathway |

| Reversal | Total mitigation required (in temperature or Wm−2 units) |

| Reverse Forcing | Reverse forcing portion of the reversal required to accomplish GW mitigation |

| SAI | Stratosphere aerosol injections |

| SG | Solar geoengineering: General term can include SRM and/or physics modeling |

| SRM | Solar radiation modification: Specific to albedo areas or solar reduction changes |

| UHI | Urban heat island |

| ZGWG | The observation of zero increases in GW for a period of time (1 Year for ASG) |

Appendix A. Earth Brightening of Hotspots and Its Influence on Water Vapor Feedback

Appendix B. Bayesian Estimate for Outgoing Transmission Loss in Earth Brightening

Appendix C. CaCO3 and SO2 Stratospheric Injections—Area Approach

Appendix D. Feedback Amplification Conversions

Appendix E. Recent Global Warming 2023 Trend

References

- Thomson, A.M.; Calvin, K.V.; Smith, S.J.; Kyle, G.P.; Volke, A.; Patel, P.; Delgado-Arias, S.; Bond-Lamberty, B.; Wise, M.A.; Clarke, L.E.; et al. RCP4.5: A pathway for stabilization of radiative forcing by 2100. Clim. Chang. 2011, 109, 77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feinberg, A. Urbanization Heat Flux Modeling Confirms it is a Likely Cause of Significant Global Warming: Urbanization Mitigation Requirements. Land 2023, 12, 1222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, P.; Ren, G.; Qin, Y.; Zhai, Y.; Zhai, T.; Tysa, S.K.; Xue, X.; Yang, G.; Sun, X. Urbanization effects on estimates of global trends in mean and extreme air temperature. J. Clim. 2021, 34, 1923–1945. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sánchez, J.; McInnes, C. Optimal Sunshade Configurations for Space-Based Geoengineering near the Sun-Earth L1 Point. PLoS ONE 2015, 10, e0136648. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Early, J. Space-based solar shield to offset greenhouse effect. J. Br. Interplanet. Soc. 1989, 42, 567–569. [Google Scholar]

- Govindasamy, B.; Caldeira, K. Geoengineering Earth’s radiation balance to mitigate CO2-induced climate change. Geophys. Res. Lett. 2000, 27, 2141–2144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Angel, R. Feasibility of cooling the Earth with a cloud of small spacecraft near the inner Lagrange point (L1). Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2006, 103, 17184–17189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fuglesang, C.; Miciano, M. Realistic sunshade system at L1 for global temperature control. Acta Astronaut. 2021, 186, 269–279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bromley, B.; Khan, S.; Kenyon, S. Dust as a solar shield. PLoS Clim. 2023, 2, e0000133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jones, A.C.; Haywood, J.M.; Jones, A. Climatic impacts of stratospheric geoengineering with sulfate, black carbon and titania injection. Atmos. Chem. Phys. 2016, 16, 2843–2862. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tilmes, S.; Sanderson, B.M.; O’Neill, B.C. Climate impacts of geoengineering in a delayed mitigation scenario. Geophys. Res. Lett. 2016, 43, 8222–8229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Izrael, Y.; Volodin, E.; Kostrykin, S.; Revokatova, A.; Ryaboshapko, A. The ability of stratospheric climate engineering in stabilizing global mean temperatures and an assessment of possible side effects. Atmos. Sci. Lett. 2014, 15, 140–148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Niemeier, U.; Timmreck, C. What is the limit of climate engineering by stratospheric injection of SO2? Atmos. Chem. Phys. 2015, 15, 9129–9141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jones, A.C.; Hawcroft, M.K.; Haywood, J.M.; Jones, A.; Guo, X.; Moore, J.C. Regional Climate Impacts of Stabilizing Global Warming at 1.5 K Using Solar Geoengineering. Earth’s Future 2018, 6, 230–251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wigley, T.M. A combined mitigation/geoengineering approach to climate stabilization. Science 2006, 314, 452–454. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kravitz, B.; Robock, A.; Forster, P.M.; Haywood, J.M.; Lawrence, M.G.; Schmidt, H. An overview of the Geoengineering Model Intercomparison Project (GeoMIP). JGR Atmos. 2013, 118, 13, 103–13, 107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barrett, S.; Lenton, T.M.; Millner, A.; Tavoni, A.; Carpenter, S.R.; Anderies, J.M.; Chapin III, F.S.; Crépin, A.S.; Daily, G.; Ehrlich, P.; et al. Climate engineering reconsidered. Nat. Clim. Chang. 2014, 4, 527–529. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, J.; Cao, L.; MacMartin, D.; Simpson, I.; Kravitz, B.; Cheng, W.; Visioni, D.; Tilmes, S.; Richter, J.; Mills, M. Stratospheric Sulfate Aerosol Geoengineering Could Alter the High-Latitude Seasonal Cycle. Geophys. Res. Lett. 2019, 46, 14153–14163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malik, A.; Nowack, P.J.; Haigh, J.D.; Cao, L.; Atique, L.; Plancherel, Y. Tropical Pacific climate variability under solar geoengineering: Impacts on ENSO extremes. Atmos. Chem. Phys. 2020, 20, 15461–15485. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine. Reflecting Sunlight: Recommendations for Solar Geoengineering Research and Research Governance; Consensus Study Report; National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine: Washington, DC, USA, 2021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, A.; Kemp, L. A Fate Worse Than Warming? Stratospheric Aerosol Injection and Global Catastrophic Risk. Front. Clim. 2021, 3, 720312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Diffenbaugh, N.; Barnes, E. Data-driven predictions of the time remaining until critical global warming thresholds are reached. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2023, 120, e2207183120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hansen, J.E.; Sato, M.; Simons, L.; Nazarenko, L.S.; Sangha, I.; Kharecha, P.; Zachos, J.C.; von Schuckmann, K.; Loeb, N.G.; Osman, M.B.; et al. Global warming in the pipeline. Oxf. Open Clim. Chang. 2023, 3, kgad008. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- MEER Project. Mirrors for Earth’s Energy Rebalancing. 2023. Available online: https://www.meer.org/ (accessed on 10 April 2023).

- Feinberg, A. Solar Geoengineering Modeling and Applications for Mitigating Global Warming: Assessing Key Parameters and the Urban Heat Island Influence. Front. Clim. 2022, 4, 870071. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- NASA Vital Signs. Global Temperature|Vital Signs—Climate Change: Vital Signs of the Planet. 2023. Available online: https://climate.nasa.gov/vital-signs/global-temperature/ (accessed on 10 April 2023).

- NOAA. Climate at a Glance Time Series (Land and Ocean Data). Available online: https://www.ncei.noaa.gov/access/monitoring/climate-at-a-glance/global/time-series/globe/ocean/12/12/1975-2023?filter=true&filterType=binomial (accessed on 10 April 2023).

- Feinberg, A. A Re-radiation Model for the Earth’s Energy Budget and the Albedo Advantage in Global Warming Mitigation. Dyn. Atmos. Ocean. 2021, 97, 101267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hartmann, D.L.; Klein, A.M.G.; Tank, M.; Rusticucci, L.V.; Alexander, S.; Brönnimann, Y.; Charabi, F.J.; Dentener, E.J.; Dlugokencky, D.; Easterling, D.R.; et al. Observations: Atmosphere and Surface. In Climate Change 2013: The Physical Science Basis: Contribution of Working Group I to the Fifth Assessment Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change; Stocker, T.F., Qin, D., Plattner, G.-K., Tignor, M., Allen, S.K., Boschung, J., Nauels, A., Xia, Y., Bex, V., Midgley, P.M., Eds.; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK; New York, NY, USA, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Feinberg, A. Climate Sensitivity and Feedback Estimates Using Correlated Rates: Consideration of an Urbanization Influence. 2024. Available online: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/368601957_Climate_sensitivity_and_feedback_estimates_using_correlated_rates_Consideration_of_an_urbanization_influence (accessed on 12 March 2023).

- Dessler, A.; Zhan, Z.; Yang, P. Water-vapor climate feedback inferred from climate fluctuations, 2003–2008. Geophys. Res. Lett. 2008, 35, 20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, R.; Su, H.; Liou, K.; Jiang, J.; Gu, Y.; Liu, S.; Shiu, C. An Assessment of Tropospheric Water Vapor Feedback Using Radiative Kernels. JGR Atmos. 2018, 123, 1499–1509. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feinberg, A. Urban Heat Island High Water-Vapor Feedback Estimates and Heatwave Issues: A Temperature Difference Approach to Feedback Assessments. Sci 2022, 4, 44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feinberg, A. Urban heat island amplification estimates on global warming using an albedo model. SN Appl. Sci. 2020, 2, 2178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, D.; Zhao, S.; Zhang, L.; Sun, G.; Liu, Y. The footprint of urban heat island effect in China. Sci. Rep. 2015, 5, 11160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Smoliak, B.; Gelobter, M.; Haley, J. Mapping potential surface contributions to reflected solar radiation. Environ. Res. Commun. 2022, 4, 065003. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Keutsch, F. The Stratospheric Controlled Perturbation Experiment (SCoPEx); Harvard University: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2020; Available online: https://scopexac.com/wp-content/uploads/2021/03/1.-Scientific-and-Technical-Review-Foundational-Document.pdf (accessed on 10 April 2023).

- Keith, D.; Weisenstein, D.; Dykema, J.; Keutsch, F. Stratospheric Solar Geoengineering without Ozone Loss. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2016, 113, 14910–14914. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tollefson, J. First sun-dimming experiment will test a way to cool the Earth. Nature 2018, 563, 613–615. Available online: https://www.nature.com/articles/d41586-018-07533-4 (accessed on 15 April 2023). [CrossRef]

- Ferraro, A.; Charlton-Perez, A.; Highwood, E. Stratospheric dynamics and midlatitude jets under geoengineering with space mirrors and sulfate and titania aerosols. J. Geophys. Res. Atmos. 2015, 120, 414–429. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dykema, J.; Keith, D.; Anderson, J.; Weisenstein, D. Stratospheric controlled perturbation experiment: A small-scale experiment to improve understanding of the risks of solar geoengineering. Phil. Trans. R. Soc. A 2014, 372, 20140059. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crutzen, P. Albedo Enhancement by Stratospheric Sulfur Injections: A Contribution to Resolve a Policy Dilemma? Clim. Chang. 2006, 77, 211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clifford, C. White House Is Pushing Ahead Research to Cool Earth by Reflecting Back Sunlight. CNBC. 2022. Available online: https://www.cnbc.com/2022/10/13/what-is-solar-geoengineering-sunlight-reflection-risks-and-benefits.html (accessed on 18 September 2023).

- Van Vuuren, D.P.; Edmonds, J.; Kainuma, M.; Riahi, K.; Thomson, A.; Hibbard, K.; Hurtt, G.C.; Kram, T.; Kram, V.; Lamarque, J.-F.; et al. The representative concentration pathways: An overview. Clim. Chang. 2011, 109, 5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Held, M.; Winton, M.; Takahashi, K.; Delworth, T.; Zeng, F. Probing the fast and slow components of global warming by returning abruptly to preindustrial forcing. J. Clim. 2010, 23, 2418–2427. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wikipedia. List of Countries by Total Wealth. 2022. Available online: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/List_of_countries_by_total_wealth (accessed on 17 September 2023).

- Mautner, M.N. A space-based solar screen against climatic warming. J. Br. Interplanet. Soc. 1991, 44, 135–138. [Google Scholar]

- Maghazel, O.; Netland, T. Drones in manufacturing: Exploring opportunities for research and practice. J. Manuf. Technol. Manag. 2019, 31, 1237–1259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klauser, F.; Pauschinger, D. Entrepreneurs of the air: Sprayer drones as mediators of volumetric agriculture. J. Rural Stud. 2021, 84, 55–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agri Spray Drones. How Many Acres per Hour or Day Can a Spray Drone Spray? Available online: https://agrispraydrones.com/how-many-acres-per-hour-or-day-can-a-spray-drone-spray/ (accessed on 9 June 2023).

- Li, X.; Peoples, J.; Yao, P.; Ruan, X. Ultrawhite BaSO4 Paints and Films for Remarkable Daytime Subambient Radiative Cooling. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2021, 13, 21733–21739. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Felicelli, A.; Katsamba, I.; Barrios, F.; Zhang, Y.; Guo, Z.; Peoples, J.; Chiu, G.; Ruan, X. Thin layer lightweight and ultrawhite hexagonal boron nitride nanoporous paints for daytime radiative cooling. Cell Rep. Phys. Sci. 2022, 3, 101058. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grossman, D. With Sawdust and Paint, Locals Fight to Save Peru’s Glaciers. 2012. Available online: https://theworld.org/stories/2012-09-25/sawdust-and-paint-locals-fight-save-perus-glaciers (accessed on 3 March 2023).

- Huang, X.; Yang, J.; Wang, W.; Liu, Z. Mapping 10 m global impervious surface area (GISA-10m) using multi-source geospatial data. Earth Syst. Sci. Data 2022, 14, 3649–3672. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, Z.; Du, W.; Jiang, H.; Weng, Q.; Guo, H.; Han, Y.; Xing, Q.; Ma, Y. Global 10-m impervious surface area mapping: A big earth data based extraction and updating approach. Int. J. Appl. Earth Obs. Geoinf. 2022, 109, 102800. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Azari Jafari, H.; Kirchain, R.; Gregory, J. Mitigating Climate Change with Reflective Pavements. MIT Study on Roads. CSHub Topic Summary. 2020. Available online: https://cshub.mit.edu/sites/default/files/images/Albedo%201113_0.pdf (accessed on 25 November 2022).

- Wikipedia. Gasoline Gallon Equivalent. 2021. Available online: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Gasoline_gallon_equivalent (accessed on 4 December 2021).

- Ong, S.; Campbell, C.; Denholm, P.; Magolis, R.; Heath, G. Land-Use Requirements for Solar Power Plants in the United States; Technical Report NREL/TP-6A20-56290; National Renewable Energy Lab. (NREL): Golden, CO, USA, 2013. Available online: https://www.nrel.gov/docs/fy13osti/56290.pdf (accessed on 11 November 2023).

- Zhao, L.; Lee, X.; Smith, R.; Oleson, K. Strong, contributions of local background climate to urban heat islands. Nature 2014, 511, 216–219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- EPA. Study Cambridge Systematics. Cool Pavement Report, Heat Island Reduction Initiative. 2005. Available online: https://citeseerx.ist.psu.edu/viewdoc/download?doi=10.1.1.648.3147&rep=rep1&type=pd (accessed on 12 March 2023).

- Smart Surfaces Coalition. Available online: https://smartsurfacescoalition.org/smart-surfaces (accessed on 12 March 2023).

- ScienceDirect, Calcium Carbonate. Available online: https://www.sciencedirect.com/topics/chemistry/calcium-carbonate (accessed on 23 April 2023).

- AmericanElements, Calcium Carbonate Nanoparticles. Available online: https://www.americanelements.com/calcium-carbonate-nanoparticles-471-34-1#:~:text=About%20Calcium%20Carbonate%20Nanoparticles,60%20m2%2Fg%20range (accessed on 23 April 2023).

- Urupina, D.; Lasne, J.; Romanias, M.N.; Thiery, V.; Dagsson-Waldhauserova, P.; Thevenet, F. Uptake and surface chemistry of SO2 on natural volcanic dusts. Atmos. Environ. 2019, 217, 116942. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Forster, P.; Storelvmo, T.; Armour, K.; Collins, W.; Dufresne, J.L.; Frame, D.; Lunt, D.J.; Mauritsen, T.; Palmer, M.D.; Watanabe, M.; et al. The Earth’s Energy Budget, Climate Feedbacks, and Climate Sensitivity. In Climate Change 2021: The Physical Science Basis: Contribution of Working Group I to the Sixth Assessment Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change; Masson-Delmotte, V., Zhai, P., Pirani, A., Connors, S.L., Péan, C., Berger, S., Caud, N., Chen, Y., Goldfarb, L., Gomis, M.I., et al., Eds.; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK; New York, NY, USA, 2023; pp. 923–1054. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Objective | Section | Highlighted Results | Other Reference(s) |

|---|---|---|---|

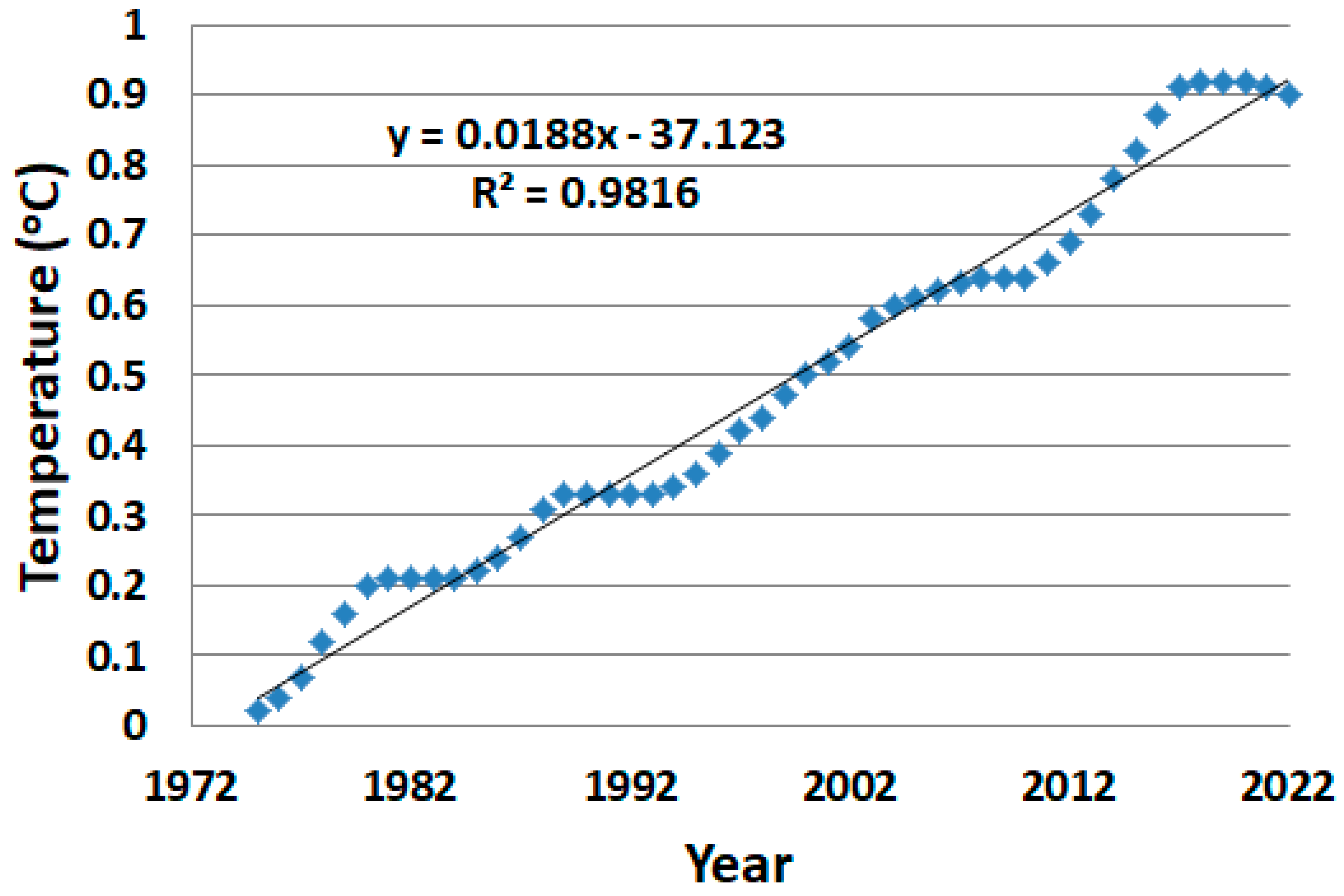

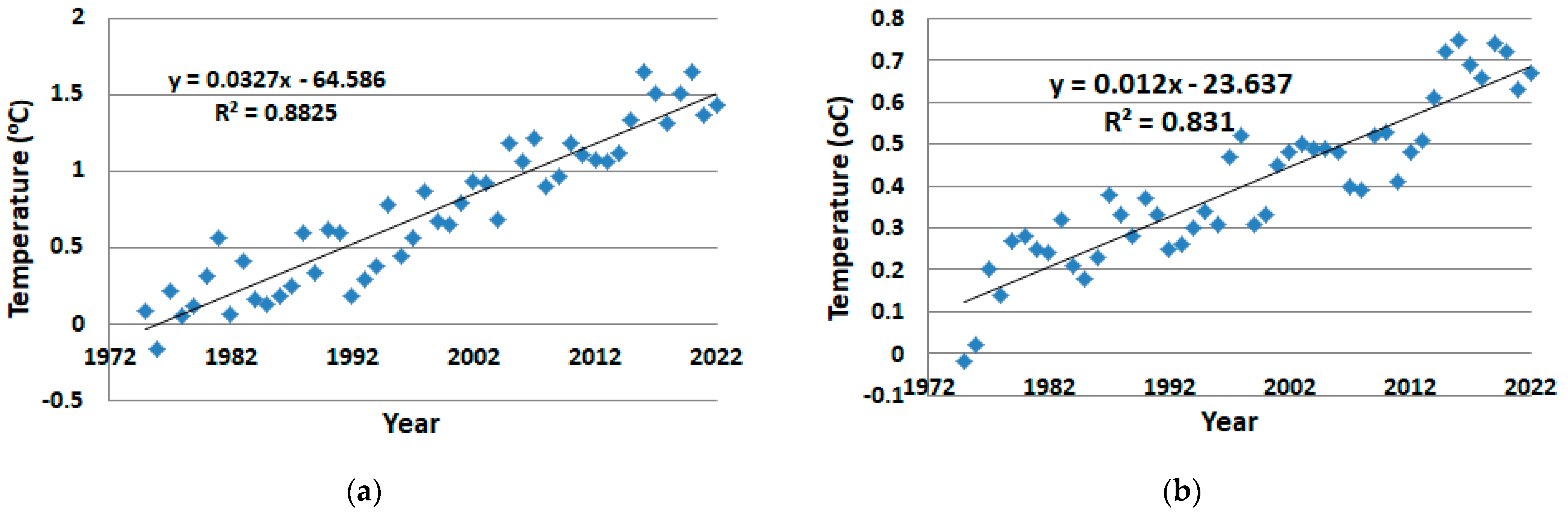

| ASG temperature reversal | 2.2, Equation (1) | −0.0188 °C/year This is the estimated yearly temperature reversal goal. | NASA [26]; NOAA [27] |

| ASG energy reversal | 2.3, Equation (6) | −0.0293 Wm−2/year This is the estimated yearly reverse forcing requirement to achieve the temperature reversal. | Findings, Feinberg [25] |

| SG savings and greenhouse gas equivalency | 2.3.1 | Results indicate an estimated 38% work saving for climate mitigation using SG compared to CDR. | Feinberg [28], Findings |

| SRM area estimate equation | 2.3.2 | SRM area estimates can be determined using this equation. | Findings, Feinberg [25] |

| Earth brightening transmission loss | 3.1 | The probability of clear sky transmission is 78%. This helps to provide estimates since not all of the SRM reflected radiation escapes to outer space. | Findings |

| Earth brightening cool pavement example | 3.1.1 | AT is the area modification relative to the area of the Earth AE | Findings |

| L1 Space sunshade estimates | 3.2 | This is the required area for a space disc at L1 | Findings |

| Annual stratospheric injection estimates | 3.3 | Table 3, 0.313 Mt[SO2]Yr−1 This is the amount of SO2 injection per year for ASG | Findings |

| Overview of estimates | 3.4 | Table 4 and Table 5 provide a concise summary of the area requirements for different SRM methods | Findings |

| RCP ASG cumulative area estimates | 3.5 | ASG cumulative estimates anticipated with different RCP scenarios | Findings |

| ASR management—recommendations | 4.1.1, 4.1.2, 4.1.3, 4.1.4, 4.1.5, 4.1.6 | 4.1.1: Allocation by country 4.1.2: L1 Space clusters 4.1.3 Earth brightening 4.1.4: Natural hotspots 4.1.5: Mixed planning and ratings 4.1.6: Negative SG | Findings |

| Conclusions | 5 | Findings | |

| Earth brightening of hotspots and water vapor feedback | Appendix A | The results find that feedback reductions can be increased in some hotspot areas, further reducing the SRM area. In this example, the SG goal is cut in half. | Findings |

| Bayesian estimate for outgoing transmission | Appendix B | TrClear = 1 − 0.22 = 0.78 This is the Bayes estimate for the probability of the reflected sunlight from an SRM area to reach outer space. | Findings |

| CaCO3 and SO2 stratospheric injections—area approach | Appendix C | This is the area coverage estimated for these aerosols and depends on their reflection efficiencies. | Findings |

| Feedback conversions | Appendix D | Converts feedback amplification to feedback units. | Estimates |

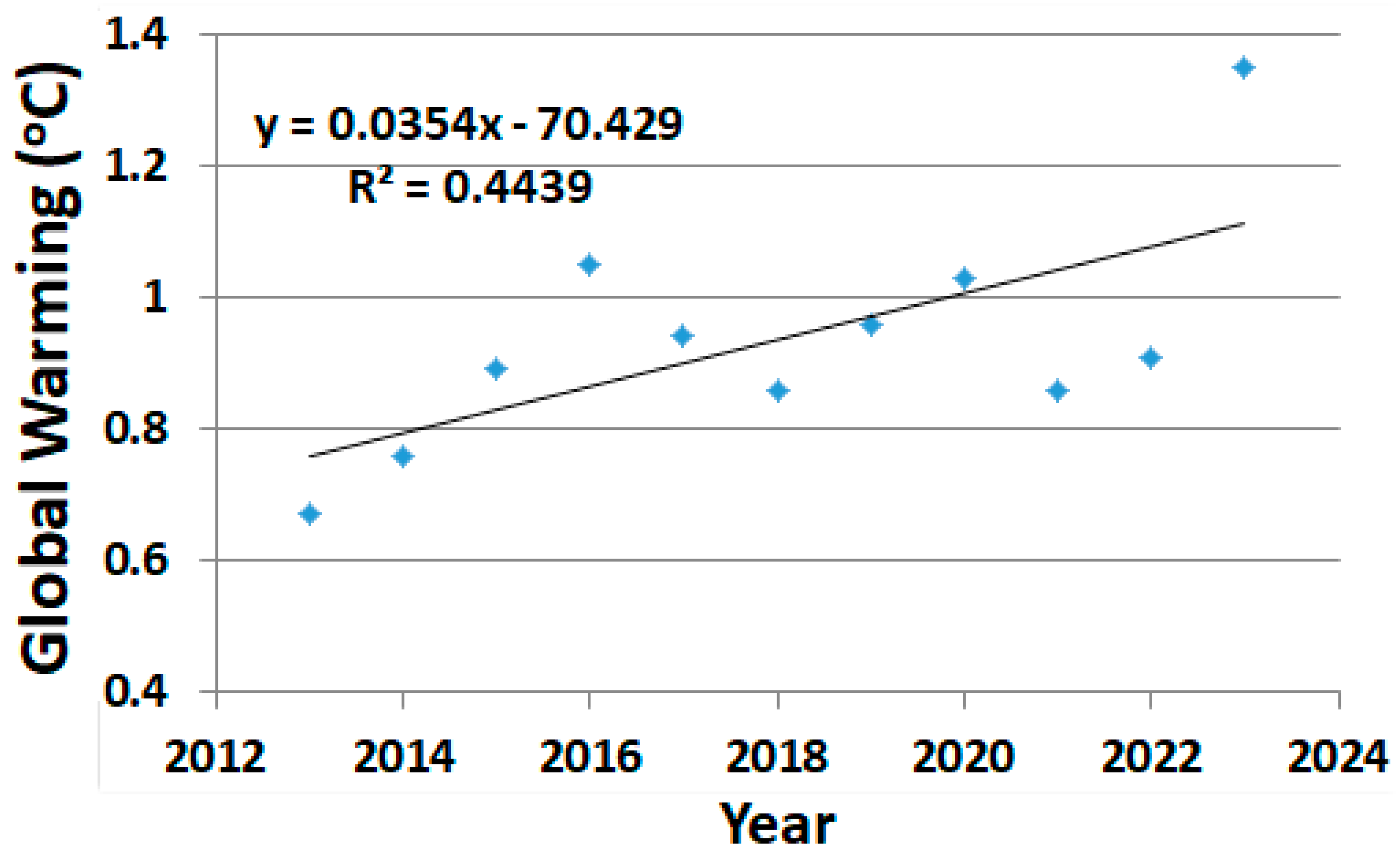

| Recent GW 2023 trends | Appendix E | Recent trends due to a 2023 GW jump | Estimates |

| SG calculator | Supplementary Materials | SG helpful calculator is provided for the results. | Findings |

| Symbol | Definition |

|---|---|

| Target area: This is the area for which an SRM albedo modification is to be applied | |

| Earth’s area | |

| AF | Feedback amplification with average taken as AF = 2.15: A unit less number, to convert to feedback units see Appendix D |

| CC | Clausius–Clapeyron relation |

| , | SG target’s albedo modification: is before, is after SRM (Equations (7) and (8)) |

| f = 62% | Re-radiation factor: Average re-radiation occurring in the atmosphere |

| HT | UHI microclimate amplification factor |

| SO2 injection rate | |

| Radiation change at the TOA | |

| ∆PASG | Annual reversal in Watts/m2: Reverse forcing to mitigate annual yearly increase in GW (this does not include feedback which is assumed to reverse the amount required |

| ∆PRev | Reversal change in Watts/m2: Full GW reversal required (includes reverse forcing and feedback) |

| Reverse forcing albedo change from a target area T in Watts/m2: This is the reverse forcing required assuming the feedback portion would also reverse | |

| Average solar radiation | |

| TR | Temperature reversal: ASG goal to reverse this temperature rise (Equation (1)) |

| TR | Transmissibility: This is applied to a small reduction in the incoming solar radiation from the sun (1361 Wm−2) |

| TOA | Top of the atmosphere |

| XS | Solar irradiance averaging 47% |

| XS | Space irradiance: If at L1 in space, XS = 4, if in other areas, XS = 1 |

| Stratosphere Injection | Full Reversal | Annual Reversal |

|---|---|---|

| ΔRTOA (Wm−2) | 1.47 | 0.0293 |

| (Mt[SO2]Yr−1) | 6.85 | 0.313 |

| Savings | 5.7 * | 22 ** |

| Earth Brightening | Space | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Parameters | Pavements Roofs | Desert Treatment | UHIs | Earth (Sea) Mirrors ** | L1 Space Sunshading Parameters | Stratosphere Injections | |

| ∆PASG (Wm−2) | −0.0293 | −0.0293 | −0.0293 | −0.0293 | ∆PASG (Wm−2) | −0.0293 | −0.0293 |

| XS = 1, XO = 1, XC = | 0.47 | 0.92 | 0.47 | 0.7 (0.85) | XC = 1, XS = | 4 | 1 |

| 0.3 | 0.44 | 0.1 | 0.75 | 0.7 | 0.3 | ||

| HT | 1 | 1 | 3 | 2 (1) | HT | 1 | 1 |

| 2.15 | 2.15 | 2.15 | 2.15 | 2.15 | 2.15 | ||

| Earth Brightening Minimal Results | L1 Space Disc Results | SO2, CaCO3 Injec. | |||||

| AT/AE | 0.061% | 0.0212% | 0.062% | 0.0082% (0.0144%) | AT/AE Earth Shade | 0.00308% | 0.0288%/eff (0.31 Mt[SO2]Yr−1) |

| AT (Mi2) | 120,070 | 41,880 | 120,070 | 16,122 (28,350) | Shade AT (Mi2, km2) | 6046, 15,586 | 55,848, 148,644 |

| Radius (Mi) | 196 | 115 | 196 | 72 (95) | Shade Radius (Mi, km) | 43, 71 | 133, 218 |

| AT (km2) | 3.1 × 105 | 1.08 × 105 | 3.1 × 105 | 4.2 × 104 (7.3 × 104) | Disc Area (Mi2, km2) * | 6046, 15,586 | - |

| Radius (km) | 315 | 131 | 315 | 116 (153) | Disc Radius (Mi, km) * | 43, 71 | - |

| T2, T1 XC | 61 °C, 33 °C 0.5, 0.47 |

| AF | 4.3 |

| ΔPASG (Wm−2) | −0.0293 |

| AT/AE | 0.0184% |

| AT (Mi2) | 36,022 |

| Radius (Mi) | 107 |

| AT (km2) | 0.9 × 105 |

| Radius (km) | 169 |

| RCP Scenarios | Peak Year, (CO2 ppm) | Peak Plus 10-Year Lag for ASG (Starting in 2023) Years | Earth Surface Brightening * AT/AE | L1 Space Disc Size * AT/AE | * (Mt[SO2]Yr−1) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| RCP 2.6 | 2025 (430 ppm) | 12 | 0.061% × 12 = 0.73% | 0.003% × 12 = 0.036% | 0.313 × 12 = 3.8 |

| RCP 4.5 | 2045 (475 ppm) | 32 | 0.061% × 32 = 1.95% | 0.003% × 32 = 0.1% | 0.313 × 32 = 10 |

| ASG SRM Method | Cost Rating | Political-Governance Rating | Likely Success Rating | Main- Tenance Cost | Average Rating | Key Issues | US Agencies That May Be Involved * |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Earth Brightening | 1 | 1–4 (4 for SRM of natural hotspot) | 3 | 3 | 2.0–2.8 | Will require technological advances in AI drones for many paint applications | DOT, NASA, Space-X, city building codes |

| SAI | 5 | 9 | 6 | 10 | 7.5 | Highly political | NASA, Space-X |

| L1 Space Mirrors | 10 | 3 | 1–3 | 3–5 | 4.3–5.3 | High costs and difficulty | NASA, Space-X |

| L1 Moon Dust | 9 | 4 | 2–7 | 10 | 6.3–7.5 | High costs and difficulty | NASA, Space-X |

| Mixed Method | 5 | 4.5 | 3 | 5.5 | 4.5 | Same as above | Same as above |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Feinberg, A. Annual Solar Geoengineering: Mitigating Yearly Global Warming Increases. Climate 2024, 12, 26. https://doi.org/10.3390/cli12020026

Feinberg A. Annual Solar Geoengineering: Mitigating Yearly Global Warming Increases. Climate. 2024; 12(2):26. https://doi.org/10.3390/cli12020026

Chicago/Turabian StyleFeinberg, Alec. 2024. "Annual Solar Geoengineering: Mitigating Yearly Global Warming Increases" Climate 12, no. 2: 26. https://doi.org/10.3390/cli12020026

APA StyleFeinberg, A. (2024). Annual Solar Geoengineering: Mitigating Yearly Global Warming Increases. Climate, 12(2), 26. https://doi.org/10.3390/cli12020026