1. Introduction

Climate change is an unprecedented global challenge that requires urgent efforts to reduce carbon emissions and promote sustainable development. To address this, climate transition bonds have emerged as an important financial instrument. Unlike green bonds, which finance projects with immediate environmental benefits, climate transition bonds are specifically designed for industries that are carbon-intensive but committed to long-term decarbonization. These bonds provide critical financial support for industries to transition to sustainable practices, ensuring economic resilience while mitigating environmental impacts.

The escalating urgency of climate change has underscored the need for comprehensive financial mechanisms capable of driving the transition to a low-carbon economy. Within this paradigm, green finance has emerged as an important approach that mobilizes capital for projects that directly contribute to environmental sustainability. Green finance includes instruments such as green loans and green bonds that target investments in renewable energy, energy efficiency, and pollution control. However, as economies pursue ambitious climate goals, traditional green finance instruments alone are often insufficient for high-emitting industries facing complex decarbonization pathways. Climate transition bonds fill this gap, helping sectors such as steel, cement and chemicals to achieve incremental reductions in carbon emissions even as they work towards more comprehensive sustainable practices. In the Japanese context, these bonds align with the country’s strategic climate goals by promoting sustainable transitions in the most carbon-intensive sectors.

Japan, which has committed to becoming carbon neutral by 2050, faces unique challenges in decarbonizing key sectors such as steel and chemicals. The Fukushima disaster in 2011 increased the country’s reliance on fossil fuels, highlighting the urgency of diversifying energy sources and reducing emissions. Climate transition bonds offer a viable mechanism to finance the technological innovation and infrastructure upgrades needed for Japan’s green transformation, particularly in industries where the transition is complex and costly.

Given the global urgency to reduce emissions, climate transition bonds are a strategic tool to bridge the gap between Japan’s current industrial framework and its long-term sustainability goals. These bonds play a key role in the country’s broader climate strategy by channeling investment into low-carbon technologies and projects.

This paper assesses the role of climate transition bonds in driving green transformations in several key Japanese sectors. It examines their effectiveness in reducing carbon emissions and promoting sustainable industrial practices. It also analyzes the collaborative governance models that facilitate their implementation, providing insights into Japan’s journey towards a low-carbon economy.

This paper begins with an in-depth literature review on climate transition bonds, examining their emergence as a central financial instrument within the sustainable finance framework. This section synthesizes existing research on the effectiveness of these bonds in promoting decarbonization in carbon-intensive industries, while identifying key theoretical gaps and contextualizing this study within the broader discourse on green finance and collaborative governance. The Methodology section then outlines the qualitative case study approach and explains the rationale for selecting Japan Government Bonds, MUFG Bonds, TEPCO Bonds, and SMBC Bonds as representative cases. These cases were chosen to illustrate the diverse applications of climate transition bonds in critical sectors of the Japanese economy, each playing a unique role in advancing green transformations. The Findings section provides a detailed analysis of these case studies, assessing each bond’s contribution to reducing greenhouse gas emissions, expanding renewable energy infrastructure, stimulating economic growth, and promoting technological innovation. In the Discussion, we critically evaluate these results and explore the policy implications and governance challenges associated with climate transition bonds. This section also proposes enhancements to the collaborative governance framework, emphasizing the need for transparency, stakeholder engagement, and accountability to optimize the bonds’ efficacy in achieving long-term sustainability goals. Finally, the Conclusion synthesizes the study’s contributions to the field of sustainable finance, acknowledges limitations, and proposes future research directions to further explore the potential and constraints of climate transition bonds in supporting green transformations.

The primary objective of this study is to critically evaluate the efficacy of climate transition bonds as a transformative financial instrument in advancing Japan’s decarbonization goals, particularly in high-emitting sectors. By analyzing the impact of these bonds on carbon emission reductions, renewable energy infrastructure, economic growth, and technological innovation, this study aims to illuminate their role in facilitating green transitions in sectors that face substantial sustainability barriers. Furthermore, the study investigates the collaborative governance frameworks that underpin the deployment of climate transition bonds, emphasizing mechanisms that enhance transparency, stakeholder engagement, and regulatory accountability.

In pursuit of these objectives, this study is guided by the following research questions:

To what extent are climate transition bonds effective in driving decarbonization in Japan’s carbon-intensive industries?

How do climate transition bonds contribute to the expansion of renewable energy capacity, economic benefits, and technological advancement in Japan?

How do collaborative governance models influence the effectiveness and accountability of climate transition bonds in achieving Japan’s climate objectives?

This study seeks to address notable gaps in the current literature on sustainable finance and green transitions. Despite the growing prominence of climate transition bonds, limited empirical research has examined their role and impact within Japan’s high-emission sectors. Additionally, the nexus between climate finance and collaborative governance remains underexplored, particularly in contexts that involve complex industrial transformations and stringent climate targets. By filling these gaps, this study contributes to a more comprehensive understanding of climate transition bonds as both a financial mechanism and a governance tool, providing insights with implications for policymakers, financial institutions, and industry stakeholders engaged in Japan’s pursuit of a low-carbon economy.

2. Literature Review

2.1. Theoretical Framework

This paper primarily addresses the concept of climate transition bonds and the role of collective governance in the Japanese context. Given the focus on Japan, the literature review is divided into four sections, with the objective of establishing a more coherent theoretical framework and tracing the evolution of this concept. The first section presents a general conceptual framework of climate transition bonds. The second section concludes the development and adoption of climate transition bonds in Japan. The third section outlines a general framework of collaborative governance models, while the fourth section delves into the collaborative governance models that have emerged in Japan.

2.2. Climate Transition Bonds

In the global shift towards decarbonization, industries are exploring innovative financial instruments to support their transition to greener practices. Among these instruments, climate transition bonds have emerged as a key tool for businesses in carbon-intensive sectors. Transition bonds offer a financing mechanism for sustainable projects, particularly for businesses that may not qualify to issue green bonds [

1]. Unlike green bonds, which primarily focus on the issuer’s environmental profile or the direct allocation of proceeds to eco-friendly projects, transition bonds emphasize the commitment of the issuer to progress towards sustainability. In the credit market, behavior-focused strategies have gained significant traction in recent years, with products such as sustainability-linked mortgages emerging as key examples [

2].

Sartzetakis explored how green bonds can support the transition to a low-carbon economy, identifying key ways in which central banks can address climate change concerns [

3]. Dill conducted a comparative analysis of low-carbon and renewable energy technologies in both developed and developing nations, finding that even in developing countries, speculators view climate transition bonds as “safe” investments [

4]. Klago assessed the financing gap in renewable energy across various Asian nations, highlighting that green bonds have been effective in narrowing this gap [

5]. However, for their widespread adoption, the development of robust financial markets and legislative frameworks ensuring competition among energy firms are necessary. Bhandary et al., building on the discrete-time intergenerational model used by Shishlov et al., demonstrated that green bonds are effective tools for environmental improvement as they enable current ecological investments, which future generations will benefit from and fund [

6,

7]. Additionally, Flammer showed that climate transition bonds not only enhance ecological outcomes but also improve profitability and attract eco-conscious investors through stock market event studies [

8]. They also investigated the impact of issue announcements while examining corporate green bonds and found that following the issuing of green bonds, there was an improvement in environmental outcomes, as well as a rise in long-term and green shareholder ownership. Anbumozhi et al. examined investor feelings when utilizing social networks and how these feelings affect the green bond market by using a network view on message sentiment [

9]. They essentially discovered a positive influence on green bond yields through posts using a panel data analysis that illustrates the public’s favorable perception of green bonds.

Recent studies emphasize the importance of climate transition bonds in facilitating long-term decarbonization within high-emission sectors [

3,

10]. Additionally, research by Tuhkanen and Vulturius explores the alignment of green debt with corporate climate goals, providing insights into how financial instruments can drive sustainable business practices [

11]. Alonso and Collender et al. further discuss digital innovations and climate risks in bond markets, underscoring the role of digital finance in enhancing green bond governance and resilience [

12,

13]. These studies inform the theoretical foundation for this paper, highlighting how climate transition bonds can support targeted decarbonization, while underscoring the need for robust governance.

Salim and Shafiei analyzed the impact of urban population growth on renewable and non-renewable energy use in OECD nations, finding that while urbanization generally increases non-renewable energy consumption, higher population density tends to reduce reliance on fossil fuels [

14]. Palmer, however, expressed concern about the insufficient investment in energy efficiency and renewable energy initiatives needed to meet international climate targets [

15]. He also pointed to fraudulent advertising as a significant issue undermining progress in the sector. Schumacher explored the complexities of independent judgment within green categories and conflicts of interest [

16]. Haszeldine, after a detailed investigation, found an absence of debt obligations in this area [

17]. A counterargument suggests that legislators could impose taxes or subsidies on oil and gas; however, Mahdavi et al. argued that this is not the most effective approach [

18]. Their empirical study showed that the same fiscal dynamics that govern other forms of taxation also apply to these charges and incentives, supporting a continued focus on financial instruments as a more effective policy tool.

Böhringer and Löschel investigated the optimal distribution of financial resources in emission financing [

19]. They found that, compared to a risk-free scenario, low-risk developing nations attract more projects and benefit from higher effective pricing per emission credit, while high-risk nations experience the opposite. Empirical evidence shows that risk factors significantly influence the financial outcomes of emission financing. Dorband et al. analyzed the impact of carbon pricing across various income levels in 87 predominantly low- and middle-income nations and found that in higher-income countries, carbon pricing tends to have a negative effect [

20]. However, they argued that addressing income inequality and combating global warming are not mutually exclusive, even in lower-income nations. Dong et al. examined renewable energy and highlighted concerns about the often-overlooked disparities in the relationship between emissions and renewable energy adoption across nations with differing socioeconomic levels [

21]. Their research indicates that per capita emissions from fossil fuels, as well as investments to reduce them, tend to disregard the macro-region’s GDP. Studies such as Chen’s, for example, focused on reducing emissions within a single nation—such as China—without considering global comparisons [

22]. Dong et al. argued that it is crucial to analyze emissions across various geographical regions, paying particular attention to factors such as population density [

21].

Lucchetta presented a study outlining how corporate social and environmental actions contribute to value creation for both corporations and their shareholders [

23]. Investors view the effective use of natural capital assets as a reliable indicator of management’s overall efficiency, particularly in the allocation of financial resources. As a result, such sustainable practices can lead to a significant improvement in corporate standards. However, Nicol et al. found that while businesses are increasingly attempting to link environmental initiatives to financial performance, they often struggle to make a compelling economic case for sustainability-related efforts [

24]. Alamgir and Cheng observe that, due to the substantial threat climate change poses to long-term economic growth, an increasing number of financial institutions are reducing the carbon emissions of their asset portfolios and reallocating resources toward environmentally sustainable investments [

25]. Banga similarly highlighted the crucial role that financial institutions are playing in driving ecological and energy transformation in response to mounting environmental challenges [

26].

Pietri argued that climate transition bonds are one of the most effective tools for raising capital for clean, sustainable initiatives, and that they have recently gained significant traction in financial markets [

27]. Their study examined how these bonds are priced and whether labeling a bond as “green” rather than non-green (conventional) could offer cost savings to issuers. In terms of corporate environmental practices, reporting serves two key functions. First, it builds trust by demonstrating to stakeholders, the public, and shareholders that businesses are committed to sustainability [

28]. Second, it plays a role in establishing new guidelines and practices, enabling companies to formulate well-defined strategies for addressing sustainability and climate change [

29]. Torvanger et al. further noted that issuing climate transition bonds helps companies develop new skills by fostering collaboration between the sustainability division and departments, such as finance, which traditionally do not engage with ethical, social, or governance issues [

30].

2.3. Development and Adoption of Climate Transition Bonds in Japan

Climate transition bonds are increasingly seen as an important part of the transition from carbon-intensive practices to more sustainable alternatives. In Japan, where the government has set a target date of 2050 for carbon neutrality, this financial instrument is even more timely. The 2011 Fukushima nuclear disaster led to an increased use of fossil fuels in Japan’s energy sector, accelerating the need for a transition to greener options [

31].

Unlike green bonds, which finance projects that already have sustainable renewable energy development in place, climate transition targets industries that purchase carbon-intensive products but which can act in an environmentally responsible manner. This is important in Japan, as the steel, cement, and chemical industries not only account for significant economic value, but also a large amount of carbon dioxide emissions [

32].

Japan is one of the governments that has actively been promoting climate transition bonds as an instrument in its strategy to decarbonize the economy. That financing, funneled through climate bonds, funds carbon capture and storage (CCS), renewable energy infrastructure, and retrofitting of industrial plants to cut emissions. In enacting this, Japan hopes that these bonds will be fully compliant with international standards in terms of transparency and green credentials [

33].

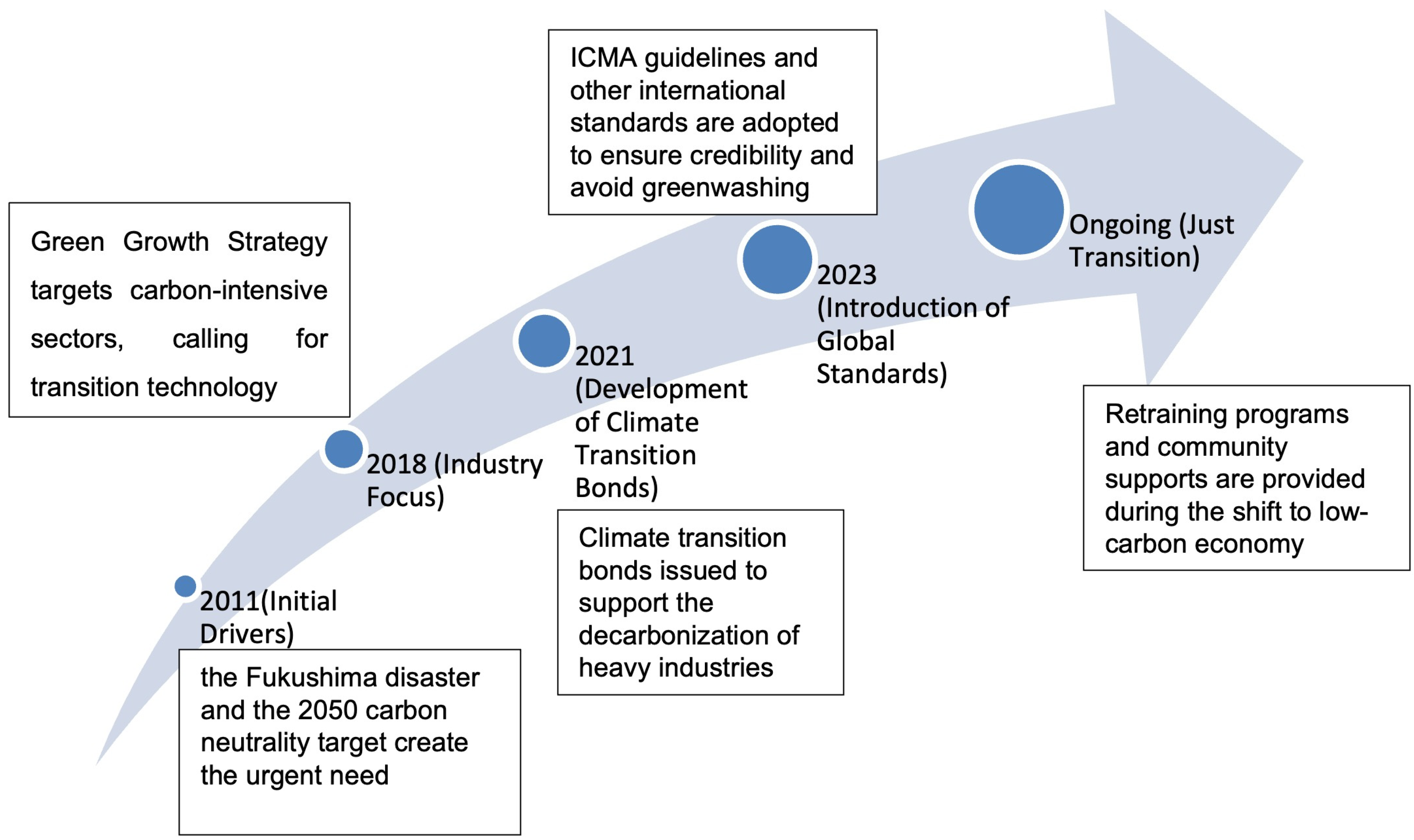

Figure 1 illustrates the evolution of climate transition bonds in Japan, providing a timeline of key developments and policy milestones.

The sustainability of climate transition bonds, both in terms of their environmental benefits and their overall contribution to climate transition, hinges on the regulatory frameworks that determine what qualifies as an eligible project. To ensure these bonds achieve meaningful impact, it is essential to implement strict eligibility criteria and require detailed reporting, which helps prevent greenwashing—where companies claim environmental progress without implementing substantial changes. The Climate Transition Finance Handbook further elaborates on these standards, and outlines how investments in sustainability-linked bonds (ISBs) can effectively contribute to measurable carbon emission reductions [

33]. This alignment with global standards would enhance the appeal of Japan’s climate transition bonds to international investors by increasing their credibility. As sustainable finance continues to grow, investors are seeking capital opportunities that align with their environmental, social, and governance (ESG) criteria. By adhering to these standards, Japan not only strengthens the credibility of its bonds but also attracts the critical capital required to finance its decarbonization efforts [

8].

Globally, green bonds have played a prominent role in supporting projects that deliver immediate environmental benefits, such as zero-carbon energy initiatives and energy efficiency improvements, as exemplified by Japan [

32]. However, climate transition bonds represent a distinct category. They are designed to support industries that are in the process of transitioning to more sustainable practices but have not yet fully adopted green solutions. This makes them particularly important for Japan’s heavy industries, which are both key drivers of the economy and significant contributors to CO

2 emissions [

31].

Climate transition bonds facilitate a phased approach within industries, rather than expecting immediate results, by financing projects that offer environmental benefits from the outset, such as solar or wind energy installations. This approach is particularly important for sectors in Japan that are heavily reliant on fossil fuels and require significant efforts to transition effectively. In the context of Japan’s carbon neutrality policy, climate transition bonds are even more important because of their role in financing the incremental improvements needed to modernize these industries [

33].

The success of climate transition bonds will largely depend on their contribution to a just transition. This principle emphasizes ensuring that the shift to a low-carbon economy does not disproportionately affect workers and communities dependent on traditional, carbon-intensive industries. Climate transition bonds can play a crucial role in mitigating the negative social and economic impacts of decarbonization by financing retraining programs, community development initiatives, and other efforts that support workers in transitioning to greener sectors [

8].

The successful practice of climate transition bonds relies not only on financial mechanisms but also on effective governance structures. Considering the complexity of decarbonizing industries and aligning the interests of diverse stakeholders, a collaborative governance model becomes essential. This model ensures that multiple actors—government agencies, private sector participants, and civil society—are engaged in the decision-making process, helping to align economic goals with environmental objectives [

36]. As climate transition bonds often involve projects across various sectors, coordinated governance is required to ensure that investments are directed towards meaningful and sustainable outcomes.

2.4. Collaborative Governance Model

Ananda and Proctor have defined governance as a component of collectively established standards and guidelines intended to control behavior on both an individual and group level when it comes to collective activity [

37]. The definition of governance given by Baumgartner et al. is the “means to stay the procedure that affects choices and behaviors across the private, public, and civic domains [

38]”. More precisely, according to Bryson et al., governance is “a set of organizing and tracking activities” that makes it possible for the cooperative partnership or organization to continue [

39].

Emerson and Nabatchi defined governance as “the act of controlling, or how participants use procedures and make selections to carry out control and oversight, grant leadership, implementation, and maintain performance” [

40]. With this concept of governance in mind, it is evident that CG is one of the various forms of governance, alongside authoritarian and market governance [

41]. It will be seen that CG takes place in the framework of networked connections. According to this perspective, networking is the framework that allows CG to occur. The processes used through networks produce CG. Networks also provide “noncollaborative” activities including principal-agent, financial markets, and rivalry. As a result, even while not all network ties are cooperative, all cooperation involves relationships among participants that are effectively the edges and nodes of the network.

The definition of collective governance (CG) provided by Ansell and Gash is “a regulating setup in which one or more government organizations involve outside stakeholders in an official, consensus-oriented, and contemplative collective decision-making procedure with the objective to develop or carry out public policy or oversee public services or assets [

36]”. They emphasized that the goal of their definition was to be sufficiently limited to allow for theory-building while also addressing the criticism of uncertainty that frequently arises when discussing governance in particular. Their definition makes it abundantly evident that public organizations must bridge the gap between the public and private sectors in addition to acting as catalysts for collaboration, keeping them somewhat “in the lead” and endowing them with particular responsibilities.

Emerson et al. defined CG as a specific, more official kind of multi-stakeholder collaboration involving the government, compared to less formal versions including conversations, discussions, and international networks [

42].

The paradigm developed by Bryson et al. acknowledged the shared constraints of authority and position by highlighting the possibility of disagreement and tension as well as the critical role that accountability performs [

39]. Their CG modelling mirrored elements of Ansell and Gash’s or Emerson and Nabatchi’s approach. Secondly, they highlighted the significant general antecedent conditions that might serve as motivators or as a means of determining if cooperation is the optimal course of action. Scholars adopted a dynamic perspective as well. To initiate the cooperation, they began by discussing how crucial it was to define the starting circumstances, drivers, and connection mechanisms.

2.5. Collaborative Governance Models in Japan

According to Ansell and Gash, collaborative governance is key to the success of climate transition bonds in Japan and is characterized by the involvement of multiple stakeholders—government, private companies, financial institutions and civil society organizations—in the decision-making process [

36]. Recently, solutions have been proposed to earn triple-bottom-line returns by bonding tax-exempt local government or agency revenue with performance metrics and standards; these can be utilized as an alternative source of public capital, which has long been appealing but which has proven difficult for many existing impact investors [

38]. Bondholders rely on the disciplined operation of a project-financed special-purpose entity delivering goods or services efficiently over contract term(s) while embracing environmental stewardship, social equity obligations, and payor affordability constraints. As a result, Japan faces enormous decarbonization challenges that cannot be addressed without collaboration on governance. For instance, the Tokyo Metropolitan Government is applying a cooperative stance to its climate strategy, along with major companies and universities to move closer to carbon reduction targets. To finance projects for these ends, climate transition bonds have been issued to ensure that it is not only environmentally sustainable but also socially responsible [

32].

Climate transition bonds require a strong monitoring and evaluation process to be put in place, together with coordinated governance mechanisms. Income derives from monitoring schemes which follow the progression of funded projects and check if they have delivered the anticipated environmental benefits [

33]. The challenge is to align private sector interests with national public policy goals. Although collaborative governance could encourage discussion and cooperation among actors, the decisions of private companies may result in a trade-off between environmental sustainability and financial gains. As a result, Japanese regulators have effectively structured incentives that reward companies for achieving significant decarbonization—giving the private sector ample reason to stay on board with what climate transition bonds hope to achieve [

8].

In general, the literature highlights the multiple benefits of climate transition bonds, not only as a tool to promote environmental sustainability, but also as an emerging asset class in financial markets. They provide financial support to companies that may not be eligible to issue green bonds, to help them make an environmental transition and thus meet broader carbon reduction targets. In the Japanese context, Japan’s climate transition bonds reflects the government’s active role in responding to global climate change. Particularly in the context of energy structural transformation, climate transition bonds are a financing and strategic tool to promote the decarbonization of industry. The Japanese government has strengthened market confidence in the bonds by adopting transparent standards and compliance frameworks, and coordinating governance to ensure that investments are directed towards meaningful and sustainable outcomes. In this sense, the application of CG in climate transition bonds is significant, ensuring effective collaboration between different stakeholders to support the complex process of decarbonization. The success of CG relies on effective multi-stakeholder mechanisms to ensure that stakeholders have a voice in decision-making, thereby driving sustainable policy implementation. CG in Japan is reflected in government partnerships with business and academia, and in regulatory incentives to reward companies that achieve significant decarbonization. In the longer term, climate transition bonds will be successful to the extent with which they harmonize with international standards and integrate goals established in a global framework. With global initiatives, Japan can help build the administration and benefit from such domestic lessons on international platforms to improve its impact in reducing greenhouse gasses around the world through bonds.

The literature review provides a preliminary understanding of Japan’s climate transition bonds and CG models in Japan. Based on specific case studies, this paper evaluates the role of climate transition bonds in promoting the green transformation of several key sectors in Japan and their effectiveness in reducing emissions and promoting sustainable industrial practices, in order to contribute a more intuitive and critical analysis of Japan’s climate transition bonds and CG.

3. Methodology

This research adopts a qualitative case study methodology to explore the mechanisms by which climate transition bonds contribute to green transformations in Japan. The approach is designed to achieve two primary objectives:

To evaluate the effectiveness of climate transition bonds in mitigating carbon emissions and fostering the expansion of renewable energy infrastructure.

To analyze the collaborative governance frameworks that support the effective deployment and sustainability of these bonds.

The study applied an in-depth examination of four selected case studies: Japan Government Bonds, MUFG Bonds, TEPCO Bonds, and SMBC Bonds. The cases reflect the diverse applications and impacts of climate transition bonds across key sectors of Japan’s economy, each playing a pivotal role in the nation’s green transformation.

The research methodology is primarily grounded in the systematic collection and analysis of secondary data, sourced through the following means.

Document analysis was applied to involve a rigorous examination of government publications, bond issuance documents, project evaluations, and financial disclosures. A total of 7 documents were collected.

Literature reviews were conducted to provide a comprehensive review of the academic and industry literature that underpins the theoretical framework of this study. A total of 34 pieces of literature were collected. Key publications related to climate transition bonds, sustainable finance, and collaborative governance models were analyzed to contextualize the findings within broader scholarly and practical discourses. Quantitative and qualitative data were sourced from reputable organizations, such as the International Energy Agency (IEA), the Organization for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD), and the Climate Bonds Initiative [

34], as well as from the official reports from the corporations in order to assess the bonds’ contributions to Japan’s green transformation.

3.1. Data Collection and Validation Process

This study employed a rigorous approach to secondary data collection and validation to ensure relevance and reliability, particularly for assessing climate transition bonds’ impacts in Japan’s high-emission sectors.

Data were sourced from credible publications, including Japan’s Ministry of the Environment, financial regulatory bodies, and climate-focused organizations such as the Japan Climate Initiative and the Climate Bonds Initiative. Academic and industry sources were included to contextualize findings within both local and global frameworks. Each source was vetted for credibility, recentness, and methodological transparency.

Collected data were screened to ensure direct applicability to the study’s focus on emissions reduction, renewable energy growth, and governance structures. Quantitative metrics, such as emission reduction rates and bond issuance amounts, were prioritized. Outdated or methodologically unclear data were excluded to maintain consistency with Japan’s current climate commitments.

To confirm data accuracy, a structured validation process was used:

- (i)

Cross-Verification: Emissions and renewable energy data were cross-checked with independent sources, including reports from the Renewable Energy Institute and International Renewable Energy Agency.

- (ii)

Triangulation with Case Studies: Quantitative data were corroborated with qualitative insights from case studies, ensuring coherence between reported metrics and real-world impacts.

Quantitative metrics such as emissions reductions and renewable energy capacity were primarily derived from government and industry reports that provide standardized measurements based on established methodologies. For instance, emissions reductions associated with each bond issuance were cross-referenced with reports from environmental agencies, while renewable energy capacity expansion data were sourced from Japan’s Renewable Energy Institute and validated against sectoral averages to ensure reliability. In cases where multiple reports provided varying figures, data were triangulated to identify consistent patterns, minimizing the risk of discrepancies. Where necessary, assumptions made in secondary sources were carefully reviewed to ensure compatibility with the study’s objectives.

Recognizing limitations in secondary data, findings were cautiously interpreted and supplemented with additional credible sources where possible. Case studies were included to provide context and compensate for any gaps in quantitative data, offering a comprehensive view of the bonds’ impacts on Japan’s transition to a low-carbon economy.

3.2. Analytical Framework

To evaluate the effectiveness of these climate transition bonds, we selected the following metrics:

Emission Reduction: This is the most basic metric which will show directly whether Japan has kept its promise under the Paris Agreement. Climate transition bonds are considered effective if they finance large and long-lived projects that reduce greenhouse gas emissions in considerable amounts.

Renewable Energy Capacity: In order to reduce dependence on fossil fuels, it is essential to evaluate if Japan increases its capacity to produce renewable energy. This metric assesses the contribution of Climate Transition Bonds to increasing renewable energy infrastructure. It specifically measures the annual incremental growth in installed renewable energy capacity, both from internal initiatives and external investments.

Economic Impact: Beyond the environmental benefits, the economic outcomes of climate transition bonds are a critical metric. This includes evaluating their role in job creation, GDP growth, and the attraction of private capital investment, all of which contribute to the broader economic impact of these bonds.

Technological Innovation: Technological advancement is another metric used to evaluate Japan’s transition towards greater reliance on green energy technologies. This metric assesses the effectiveness of climate transition bonds in fostering innovations that enhance energy efficiency and reduce emissions, signaling progress in the adoption of green technologies.

Collaborative Governance Effectiveness: The effectiveness of governance surrounding climate transition bonds is vital to their success. This measure evaluates how well collaborative governance frameworks ensure transparency, accountability, and stakeholder engagement in the decision-making process, which are crucial for the successful implementation of these bonds.

4. In-Depth Case Study Analysis

Driven by global leadership and sustainability ambitions, climate transition bonds have become a crucial tool for Japan in its efforts to meet national climate targets. These bonds are designed to finance projects that promote and facilitate the transition from high-emission activities to more sustainable practices, thereby supporting Japan’s broader green transformation agenda. The case studies selected for this research highlight key sectors of the Japanese economy and examine the financial instruments employed within these sectors. The selection of Japan Government Bonds, MUFG Bonds, TEPCO Bonds, and SMBC Bonds as case studies was guided by several key criteria to ensure relevance and representativeness. First, these bonds are closely linked to Japan’s carbon-intensive sectors, such as energy and heavy industry, which are critical to the nation’s decarbonization strategy. Second, the chosen bonds reflect diversity in issuer types, covering both public (government-issued) and private (corporate-issued) bonds. This range allows for a comparative view of how governance and impact differ across sectors and issuer types. Third, these cases were selected based on data availability and accessibility, with each bond offering well-documented records on emissions reduction targets, governance frameworks, and economic performance. These criteria ensure that the selected cases provide a representative sample of climate transition bonds in Japan’s green finance market, capturing a comprehensive view of their effectiveness in high-emission industries. However, it should be noted that cases were limited as the climate transition bonds are still at the early and emerging stage in Japan as discussed in

Section 3.1. The following section provides a detailed analysis of each case study, assessing them using specific progress indicators related to green transformations as shown in

Table 1.

4.1. Japan Government Bonds

Japan Government Bonds have played a leading role in funding efforts to achieve large-scale reductions of greenhouse gas emissions, which include deploying hydrogen technologies for steel manufacture and offshore wind energy. Collectively, the projects represent a decrease in about 25 million tons of CO

2/y by 2030—making it around half as much compared to Japan’s overall goal for emission reduction in that year [

43]. Yet achieving these ambitious goals will require significant technical and economic challenges to be overcome, and the high costs that currently come with them and their infrastructural demands are significant obstacles to their fast deployment, leading many to question whether it is even feasible at all given the amount of CO

2 reduction that would allow this scale of emission cuts in such a short window.

Government Bonds have most encouraged investments including offshore wind energy concerning renewable energy capacity (all figures since 2000). Such investments are expected to contribute 7 GW into the energy grid of Japan by the year 2030 [

44], which is important for moving the country slightly away from fossil fuels and increasing the security of supply—particularly post-Fukushima. Economically, the bonds have been a boon—especially in terms of job creation and GDP expansion. The green energy sector has created about 20,000 jobs and is responsible for an estimated annual contribution to the GDP of Japan of 1.2% [

45].

A result of these bonds has been the technologies that were integrated and developed—hydrogen technologies or even smart grids are at the cutting edge. Such innovations are essential to improve energy efficiency and the more effective integration of renewable energies into Spain’s national grid. Yet for success at scale and real-world economics, these technologies need to go much further. If those innovations cannot be adopted in scale or cost-competitiveness, their influence on Japan’s energy transition might accordingly be limited [

31].

The government has been successful in forming robust public–private partnerships, a key factor in ensuring that individual actors with different interests, such as companies, local communities, and governmental agencies are all working more or less together. Clear, transparent communication and visibility are provided throughout the project lifecycle. Fostering the inclusivity of voices from smaller stakeholders and local communities is also considered as key to the long-term sustainability of these projects [

46].

4.1.1. MUFG Bonds

Bonds from MUFG have been used to finance emission reduction projects in transportation—one of Japan’s biggest producers of greenhouse gases. According to the IEA, these bonds are also expected to help save over 15 million tons of CO

2 in support of electric vehicle infrastructure by 2030 [

31]. However, this benefit can only be realized if the incentive and low GHG fuel use activates an EV boom. The paper notes that to deliver the projected benefits, key factors ranging from consumer acceptance and charging infrastructure availability through government incentives will heavily influence emissions reductions. More importantly, these bonds could also face constraints to the extent that EV adoption lags behind light vehicle market growth in Japan.

In addition to cutting emissions, MUFG Bonds have contributed to some of the largest investments in renewable energy—especially solar and wind. It is projected that these investments will contribute 3 GW to Japan’s renewable energy grid by the year 2030, which is considered to be quite a considerable portion of the energy needed to wean Japan entirely from fossil fuels [

47]. Removing the technical and financial barriers in the way to massive deployment of renewable energy technologies is crucial for ensuring long-term sustainability.

A remarkable feature is that the economic benefits of MUFG Bonds have been estimated at JPY 200 billion, which has led to investments in green energy and 15,000 jobs [

32]. But the danger stands that such economic gains could favor specific industries like construction and renewable energy, bankrupting outgoing suppliers of traditional energies: oil and gas. Moreover, the types of jobs created by these bonds may not be sustainable—in many cases, they will be related to building new renewable projects rather than running them for years after commissioning when questions arise about their long-term survival. When it comes to technological innovation, MUFG has been an early adopter in using blockchain in green finance and this has begun a new trend for the transparency, as well as efficiency of bond transactions. The system is especially beneficial in providing trust and security to green finance initiatives from scams. However, for blockchain technology to have its biggest effect, it will need the general adoption of this technology on a broader basis within the financial industry. The long-term success of this technology in achieving sustainability goals remains to be fully tested, and its ability to integrate with existing financial systems will be critical [

48].

MUFG uses a governance model predicated on broad-stakeholder participation and features robust auditing and reporting tools in order to ensure that the projects these bonds finance are consistent with both financial and sustainability goals. Nevertheless, the inclusiveness and transparency of such governance processes could be enhanced. The viability and relevance of these efforts in the long run also require that there is an authentic voice available for smaller stakeholders to shape public debates [

48].

4.1.2. TEPCO Bonds

TEPCO Bonds are focused on reducing emissions through the development of offshore wind projects, which are projected to reduce CO

2 emissions by 10 million tons annually by 2030 [

32]. These projects are part of Japan’s efforts to broaden its energy sources and move away from fossil fuels. However Japan comes with inherent natural risks, and the long-term sustainability of these projects can be greatly affected by how they are able to withstand such forces. This stability is therefore under threat from a combination of earthquakes, tsunamis, and typhoons which have the potential to disrupt these installations. All of these projects are developed to achieve 100% zero-emission levels in the future, so it is necessary that disaster-resistant technologies and infrastructures are developed accordingly.

TEPCO forecasts that its offshore wind projects will deliver 4 GW of additional renewable energy capacity to the national grid by 2030 [

31]. This growth is an important part of Japan’s policy for renewable energy, which helps to cut its reliance on fossil fuels and strengthen energy independence while adding this new capacity to Japan’s legacy energy grid, which will serve as a demonstration of the need for smart grids and stationary storage. However, integrating this new capacity into Japan’s existing energy grid will require significant upgrades, including the development of smart grids and energy storage solutions. Effectively managing these technical challenges will be crucial for the stable integration of renewable energy into Japan’s energy infrastructure.

TEPCO Bonds have been an important economic tool, improving regional economies along coastal areas through projects like the offshore wind project driving a relative 0.8% increase in GDP [

32]. This has also delivered many jobs in the green energy space, boosting local economies. However, the sustainability of these economic benefits is closely tied to the continued success of the offshore wind projects. Any disruptions, whether due to natural disasters or technical failures, could have serious economic consequences for the affected regions.

TEPCO is also investing heavily in advanced offshore wind and smart grid technology, both of which are necessary to help enable the full integration of renewables into Japan’s national grid and guarantee energy stability. However, the long-term success of these technologies will depend on their ability to withstand the environmental challenges posed by Japan’s natural landscape. The development of disaster-resistant technologies will be crucial for ensuring the sustainability of these investments and their contribution to Japan’s energy transition [

31].

The governance of TEPCO is discussed within the context of centralized forms and proportional representation through stakeholder decision-making with particular emphasis on local, industry, and government group alliances. It has been vital for increasing public acceptance of OWE and facilitating its deployment [

32]. Nonetheless, continued assessment of these governance models is necessary if they are to remain stakeholder-oriented and flexible in light of possible natural disasters.

4.1.3. SMBC Bonds

SMBC bonds reduce emissions by improving energy efficiency in the industrial sector. Flammer states these bonds have led to funded projects that have decreased industrial energy usage by 20%, supporting Japan’s overall emission reduction objective [

8]. Nonetheless, the overall impact of these bonds would still be subject to technological scalability. However, their potential to reduce emissions holistically could be stunted if these technologies are unable to gain widespread adoption across industry.

Recognising its core activity as the provision of energy-efficient facilities, SMBC Bonds also believes it has catalyzed renewable energies by shrinking overall energy demand and encouraging industry to rely on renewable sources. However, this contribution is modest compared to the direct investments in renewable energy made by other bonds analyzed here.

Economically, SMBC Bonds have had a significant impact by enhancing industrial competitiveness and contributing to a 1% increase in sector GDP. However, this growth is concentrated in specific industries, raising questions about the broader economic impact of these bonds. The potential for creating new industries and jobs in energy efficiency is also an important consideration. The long-term economic benefits of these bonds will depend on the ability of the industrial sector to sustain and build upon the initial improvements in energy efficiency.

SMBC Bonds’ innovation in the industrial sector has also been driven by investments towards technology but mainly focused on financing for energy-efficient technologies and green certifications. SMBC Bonds has been instrumental in the promotion of technological innovation, especially within industry through green certifications and funding mechanisms for energy-efficient technologies. These projects have resulted in substantial improvements to Japan’s industrial activities, improving both sustainability and competitiveness. But their promise long-term is only as good as how widespread they become, not just for mobility or transportation, but in other sectors too.

5. Findings

Crucially, an examination of Japan Government Bonds (JGB), MUFG Bonds, TEPCO Bonds, and SMBC bonds provides key insights into how climate transition bonds operate in achieving green transitions in the main sectors forming the Japanese economic system. Although the bonds themselves are varied in their emphasis and objectives, they can help Japan reach its broader goals of reducing emissions, increasing renewable energy deployment and promoting economic development. However, whether these are effective depends on several factors, such as the scalability of funded technologies or inclusivity in governance models and overcoming significant technical, as well as financial, challenges.

5.1. Role of Climate Transition Bonds in Advancing Green Transformations

Climate transition bonds played a substantial role in driving emission reductions across all four case studies. Notably, the government has used Japan Government Bonds to finance megaprojects related to hydrogen technologies and renewables for mitigating global warming. Not only do they represent a significant reduction in emissions, but these projects also go towards contributing to Japan’s obligations under the Paris Agreement. In a related announcement, MUFG Bonds have been seeking to support the transportation space through efforts aimed at electric vehicle infrastructure development in Japan—considered one of the nation’s most carbon-heavy sectors.

Nevertheless, the carbon mitigation delivered to date has not been without problems. Hydrogen technology still has issues with scalability. For many of them, 2030 is a long-term target; if it do not become widespread but consumer behavior changes as expected, reported reductions in emissions may be qualified. Furthermore, the distribution of benefits in certain sectors or regions might produce disparate results that could detract from a more holistic aim for sustainable growth nationwide.

Another big area where climate transition bonds have made a difference is in increasing the amount of renewable energy capacity. Japan Government Bonds and TEPCO Bonds, in particular, have become the top products channeling a large amount of money to support offshore wind energy investment, which helps Japan diversify its energy mix from fossil fuel. This is an important investment in Japan’s energy futures, to both increase the security of its supply and provide a more reliable renewable source.

Japan recognizes that the integration of new renewable energy capacity into its national grid is not without challenges. Significant upgrades to energy infrastructure, including smart grids and energy storage solutions, face both technical limitations and financial constraints. Given Japan’s vulnerability to natural disasters, the resilience of renewable energy projects—particularly those financed through TEPCO Bonds—remains uncertain. The key to achieving long-term sustainability lies in these innovations, alongside the development of disaster-resistant technologies.

Similarly, the growth of climate transition bonds has resulted in economic development primarily due to job generation and luring private investments, too. For example, MUFG Bonds have successfully received over JPY 200 billion in private investment and aided thousands of jobs in the green energy sector. Also, TEPCO Bonds conducted some good trade in terms of economics due to the offshore wind projects which have given a boost to local economies around coasts.

However, the regions of Japan are not equally benefiting economically from these bonds. This could further concentrate projects in certain regions or sectors, and increase regional economic disparities. There is also a concern about the number of jobs held up by these bonds; most are linked to phases involving only construction and installation as opposed to operations further down the line. These findings seem to contradict the earlier study which depicted the critical role climate transition bonds can play, not just in advancing the climate transition in the given society or environment, but also in mitigating the negative impacts pertaining to the transition, by supporting initiatives such as retraining programs and community development initiatives [

8]. However, considering that green transition bonds are relatively new in Japan and projects under such bonds are still ongoing on the ground, it is too early to make any judgment at this stage. Rather, it calls for the need for continuous monitoring and evaluation of climate transition bonds. The climate benefits and co-benefits, including economic gains, need to be sustainable and inclusive to ensure longer-term impacts and successful outcomes of climate transition.

The bonds examined in this study have catalyzed significant technological innovation, particularly in areas such as hydrogen energy, smart grids, and blockchain-powered green finance. These innovations are critical for enhancing energy efficiency, integrating renewable energy into the national grid, and ensuring transparency and accountability in green finance. The broader impact of these technologies, however, depends on their scalability and economic viability. If these innovations are deployed at scale and cost-effectively within Japan, they are likely to play a much more prominent role in the country’s energy transition. Furthermore, widespread deployment across other sectors and regions will be essential to fully realize the economic benefits of these technologies.

5.2. The Role of Collaborative Governance Models in Enhancing the Effectiveness and Impact of Climate Transition Bonds

Collaborative governance models are central to the successful implementation of climate transition bonds, as they not only accelerate green transformation but also promote social and environmental justice, transparency, and long-term sustainability. The effectiveness of these bonds, and their governance frameworks, in advancing Japan’s ambitious climate goals depends on how well they incorporate stakeholder engagement, accountability, and the alignment of diverse interests.

Collaborative governance models are designed to integrate a diverse range of stakeholders, including government actors, at both state and local levels, private sector entities such as businesses, local community members, and non-governmental organizations. In the case of Japan Government Bonds, the Japanese government established highly effective public-private partnerships (PPPs), aligning corporate interests with local community concerns. These partnerships have played a key role in facilitating the implementation of large-scale projects, ensuring that decision-making processes include all relevant stakeholders.

MUFG Bonds are supported by a governance structure that measures stakeholder engagement with meticulous precision. These bonds undergo frequent audits and are structured with progressively time-bound financing mechanisms, ensuring that the disclosing procedures confirm the alignment of funds with both financial and sustainability objectives. This process reflects stakeholder perspectives where demand meets supply. However, a notable concern with these governance models is the degree to which smaller stakeholders and local communities are genuinely engaged. Ultimately, the long-term sustainability, credibility, and inclusivity of the projects will only be ensured if these groups have a meaningful role in decision-making processes.

Transparency and accountability are central to every effective post-pandemic governance model, particularly in the context of climate transition bonds, which are especially vulnerable to greenwashing. When projects claim to be ‘green’ without meeting genuine sustainability criteria, it undermines trust in the bond’s integrity. These risks can be mitigated through collaborative efforts that establish clear criteria for project selection, implementation, and monitoring, alongside the enforcement of stringent oversight mechanisms. The TEPCO governance model is a participatory decision-making process in which academic cooperations, law, local people, and other stakeholders are engaged directly through project planning until execution, which not only increases the visibility of the project but also makes more accountable stakeholders and which can provide smooth sailing for anyone in charge of a big project.

The governance models in all four case studies must undergo continuous evaluation and adjustment to remain effective. As projects evolve and new challenges arise—such as TEPCO’s initiative to integrate disaster-resilient technologies into its networks—governance frameworks must be flexible and adaptive to meet emerging needs. Another essential function of collaborative governance models is to represent the diverse interests of stakeholders and effectively manage any conflicts that may arise during the execution of projects financed by climate transition bonds. In sectors like the industrial investments tied to SMBC Bonds, stakeholders may have varying priorities—for example, large profitable corporations may have different objectives compared to small local communities concerned about environmental impacts.

The SMBC Bonds governance model is structured to achieve an optimal balance between economic growth and environmental sustainability by uniting industry leaders, government regulators, and local communities. This model facilitates stakeholder dialogue and negotiation, helps prevent conflicts of interest, and ensures that projects are implemented effectively and equitably.

The success and sustainability of projects financed by climate transition bonds depend heavily on the governance standards under which they are developed. Inclusive, transparent, and accountable collaborative governance models are more likely to produce resilient projects capable of withstanding the challenges associated with transformative initiatives. TEPCO’s governance model, for instance, emphasizes the importance of local community engagement and disaster resilience—critical factors for the survival of offshore wind projects in Japan, given its natural landscape.

Similarly, as MUFG explores leveraging blockchain technology for green finance, the effectiveness of this innovation will rely on complementary governance frameworks that ensure its integrity. As these technologies evolve, governance models must remain flexible, adapting to emerging risks and opportunities to keep projects aligned with Japan’s broader climate objectives.

5.3. Political Implications of Climate Transition Bonds and Collaborative Governance Models

The deployment of climate transition bonds in Japan and the associated collaborative governance models have significant political implications, both domestically and internationally. These implications reflect the intersection of environmental policy, economic strategy, and international relations, as Japan seeks to balance its ambitious climate goals with economic growth and global competitiveness.

5.3.1. Domestic Political Implications

The success of climate transition bonds is closely tied to the Japanese government’s ability to deliver on its climate commitments. By effectively mobilizing capital through these bonds and implementing projects that lead to tangible environmental benefits, the government can strengthen its credibility both domestically and internationally. This is particularly important in a country like Japan, where public trust in government institutions has been challenged by past crises, such as the Fukushima disaster.

On the one hand, this requires political reactivity and flexibility from the government—making sure that these bonds will come with economic benefits shared evenly between regions and other sectors. Failure to tackle regional inequalities could incite political backlash by communities that feel sidelined in their efforts to transition towards a greener economy. This has implications in terms of political fallout—we are likely to see more regional angst, and the government needs policies that can ensure a just transition for all regions and communities.

Climate transition bonds need to be implemented in coordination between the Ministry of Environment (MOE), METI, and the Ministry of Finance. It is imperative that the climate policies are in tandem with economic and industrial strategies, thereby making this inter-ministerial cooperation key. This represents a partisan strategic window of opportunity but also has provided for less than optimal coordination—which could lead to more organized and consistent policy enactment on the one hand or decentralized non-coordinated policy fragmentation on the other.

Aside from this, the broader economic regulations in Japan may also need some tweaking to incorporate climate-transition bonds. This may require the setting of new rules or changing existing ones to ensure that projects financed by these bonds are not only environmentally sustainable but also part of broader economic and industrial policies in Japan. The consequences of these kinds of changes are political in nature and include possible industry pushback as a result of increased environmental controls, and the need for governments to walk an environmental–economic tightrope.

The future of climate transition bonds and their companion collaborative governance models depends on continuing to enjoy wide public acceptance of Japan’s transformation into a green society. This means not only making sure the projects funded by these bonds deliver tangible environmental and economic benefits but also managing the negative social impacts of this transition, such as potential job losses in traditional industries.

If the transition to a green economy is perceived as uneven or unfair, it could lead to political backlash, particularly from regions or sectors that are adversely affected. This could manifest in increased political pressure on the government to slow down or modify its green transformation agenda. Conversely, successful management of the transition, with policies that ensure a just and equitable distribution of benefits, could enhance public support for further climate action and strengthen the government’s political mandate.

5.3.2. International Political Implications

Through the practice of climate transition bonds on an international scale, Japan has solidified its standing as a premier country in climate finance and sustainable development. The successful implementation and demonstration of these bonds in Japan through driving green transformations can potentially advance international climate negotiations (such as the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change or G7).

Above all, these implications are political in nature as they pave the way for Japan to determine internationally recognized norms and standards around climate finance. Experience in Japan may offer a model, especially for the countries and regions in the Asia–Pacific, which they can follow to attract private capital for their green transitions. Yet this leadership role also entails obligations: Japan will need to show that it is seriously endeavoring for high climate action and ensure its domestic policies actually deliver on the country’s international promises. To situate Japan’s climate transition bond practices within a global context, it is valuable to compare findings with similar instruments implemented internationally. Studies from other high-emission economies, such as Germany and the United States, indicate that while climate transition bonds have garnered support for decarbonizing heavy industries, the success of these bonds is closely tied to robust governance and transparency standards. For instance, in Germany, climate transition bonds have effectively financed emissions reduction in the steel sector, aided by stringent regulatory oversight and mandatory reporting. Conversely, in the United States, the relatively flexible governance frameworks of climate bonds have raised concerns regarding accountability and greenwashing. Japan’s approach, which combines public–private collaboration with strict emissions tracking, offers a model that balances transparency with practical sectoral support. By integrating insights from these international experiences, Japan can further refine its governance frameworks to enhance the effectiveness and credibility of climate transition bonds, contributing valuable lessons to global sustainable finance practices.

These climate transition bonds of Japan also have geopolitical implications as they are based on how Japan’s economy functions and some other countries which factor the economy similarly. For instance, if Japan were to invest in renewable energy projects through these financing instruments it could increase economic ties with export powerhouses of renewable technologies like Germany or China. On the flip side, Japan moving away from using fossil fuels might adjust its relationship with Middle Eastern oil-exporting countries.

Japan could make use of its pioneering status in climate finance as a way of expanding economic diplomacy and encouraging developing countries to adopt similar financing tools. It can strengthen Japan’s relationship in the Global South, and help realize its overall foreign policy goals by assisting sustainable development activities as well as lowering global greenhouse gas emissions.

6. Discussion

This study elucidates the role of climate transition bonds as a strategic financing tool within Japan’s broader framework for achieving its 2050 carbon neutrality commitment. The findings indicate that climate transition bonds contribute not only to emissions reduction and renewable energy expansion but also to fostering innovation within Japan’s high-emission sectors. Each case—Japan Government Bonds, MUFG Bonds, TEPCO Bonds, and SMBC Bonds—provides unique insights into the bonds’ impact across varied industries, highlighting the potential of these financial instruments to bridge the funding gap in sectors facing structural and technological barriers to decarbonization.

6.1. Governance Complexities

The case analyses reveal a recurring theme of governance complexities in the deployment of climate transition bonds. Effective governance structures are crucial to uphold transparency, accountability, and stakeholder trust, particularly given the long-term commitments involved in decarbonization. However, inconsistencies in stakeholder engagement and regulatory oversight present challenges. For instance, while MUFG Bonds exhibited robust monitoring frameworks, gaps in consistent stakeholder involvement were noted across other cases. This divergence suggests a need for a standardized governance model to strengthen coordination among regulators, industry stakeholders, and financial institutions, ensuring that these bonds are managed in alignment with Japan’s climate objectives.

6.2. Sectoral Differentiation in Bond Impact

A key pattern observed is the sector-specific variability in the effectiveness of climate transition bonds. The findings reveal that sectors such as energy (as demonstrated by TEPCO Bonds) show more immediate progress in terms of renewable energy expansion, while sectors like steel and chemicals experience slower transitions due to technological constraints and higher capital requirements. This underscores the importance of designing bond structures that are tailored to the unique characteristics of each sector, enabling climate transition bonds to address specific barriers and enhance their impact on sectoral decarbonization. This sectoral differentiation aligns with the notion of “just transition”, ensuring that financial support is adapted to the readiness and requirements of each industry.

6.3. Economic–Environmental Interplay and Trade-Offs

The analysis also reveals an inherent tension between economic resilience and environmental benefits, a recurring theme in the deployment of climate transition bonds. These bonds facilitate not only environmental goals but also economic gains through employment generation, technological innovation, and industrial growth. However, trade-offs emerge, particularly in sectors where gradual decarbonization is prioritized over rapid environmental impact. For example, while bonds have been instrumental in supporting transitional stages, the incremental nature of these improvements may slow the attainment of immediate sustainability goals. This trade-off points to the need for dual-focused financial frameworks that balance economic resilience with stringent environmental objectives.

6.4. Comparative Insights with the Existing Literature

The study’s findings resonate with the extant literature on green finance, particularly in affirming the transformative role of financial instruments like climate transition bonds in enabling decarbonization. Unlike conventional green bonds, which are generally directed towards established sustainable projects, climate transition bonds provide a mechanism for supporting industries that are not yet “green” but are on the path to sustainability. This study contributes novel insights by examining the specific challenges and adaptations required in Japan’s context, where energy security concerns post-Fukushima and a heavy industrial base create unique obstacles to decarbonization. These insights add depth to the literature on climate finance by exploring the potential of adaptive, sector-specific governance models tailored to complex national contexts.

6.5. Policy Implications and Practical Applications

The findings underscore the importance of enhancing policy frameworks to support the effective deployment of climate transition bonds. Policy measures could include the establishment of standardized reporting and accountability guidelines, thus ensuring uniformity and transparency across bond issuances. Furthermore, fostering multi-stakeholder partnerships between the government, financial institutions, and industry leaders may enhance collaborative governance, creating a more cohesive approach to achieving long-term sustainability goals. By incentivizing measurable outcomes and rewarding incremental progress, Japan could enhance the appeal and effectiveness of climate transition bonds, positioning them as integral instruments within its sustainable finance strategy.

6.6. Limitations and Future Research Directions

This study acknowledges certain limitations inherent in its qualitative case study approach, which, while providing in-depth insights, may limit generalizability to broader contexts. Future research could benefit from a quantitative approach to assess the financial and environmental impacts of climate transition bonds over extended periods. Comparative studies across different countries or within varying regulatory environments could further elucidate best practices for structuring and governing climate transition bonds. Expanding research to encompass additional sectors and bond types would also provide a more holistic view, deepening our understanding of how climate finance can effectively support complex industrial transformations towards sustainability.

7. Conclusions

The findings indicate that climate transition bonds are integral to Japan’s strategy for achieving its ambitious climate goals, including the reduction of greenhouse gas emissions and the expansion of renewable energy capacity. These bonds have enabled Japan to make substantial progress toward its commitments under the Paris Agreement and its overarching objective of carbon neutrality by 2050. The projects financed by these bonds, ranging from the development of hydrogen technologies to the implementation of offshore wind energy, represent significant strides in Japan’s green transformation. However, the scalability and economic viability of these technologies present substantial challenges. The transition to a low-carbon economy necessitates overcoming technological and infrastructural barriers, particularly in integrating renewable energy into Japan’s existing grid and scaling emerging technologies like hydrogen at a competitive cost.

Moreover, the economic benefits generated by climate transition bonds, while substantial, are unevenly distributed across Japan. This raises concerns about regional disparities and the sustainability of employment opportunities created through these projects. The concentration of economic gains in specific sectors and regions could exacerbate existing inequalities, necessitating targeted policies to ensure a more equitable distribution of benefits.

Collaborative governance models are identified as critical to the effectiveness of climate transition bonds. These models facilitate the alignment of diverse stakeholder interests, enhance transparency and accountability, and ensure that projects funded by these bonds are implemented in a manner that is both inclusive and responsive to the needs of various constituencies. However, the research also highlights variations in the effectiveness of these governance frameworks across the case studies. While some models demonstrate strong stakeholder inclusion and adaptability, others may require further refinement to address emerging challenges and ensure long-term sustainability.

It should be also noted that there were several limitations to this study. Due to availability, the study had to rely heavily on the self-prepared reports developed by the respective institutions themselves, which may have impacted the comprehensiveness of the findings. In addition, while the study leveraged five metrics to capture different aspects of the climate transition bonds, as elaborated in the methodology section of this paper, considering the nature of climate projects having broad and various implications, the study might not have captured the impacts of climate transition bonds in full. Moreover, as climate transition bonds are relatively new initiatives in Japan, the study has yet to capture its long-term impacts, particularly for technological advancements and economic growth. Therefore, the continuous evaluation and adaptation of these governance models will be critical, particularly as the landscape of climate finance and environmental policy evolves.

In conclusion, while climate transition bonds represent a powerful mechanism for advancing Japan’s green transformation, their success is contingent upon addressing significant challenges related to technology, governance, and equity. As Japan continues to leverage climate finance to achieve its climate objectives, the insights gained from this research can inform the development of more effective and inclusive strategies.