Generation Z Worries, Suffers and Acts against Climate Crisis—The Potential of Sensing Children’s and Young People’s Eco-Anxiety: A Critical Analysis Based on an Integrative Review

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Generation Z and Eco-Anxiety

3. Methodology

3.1. Identification of the Main Issue

3.2. Methodological Choices

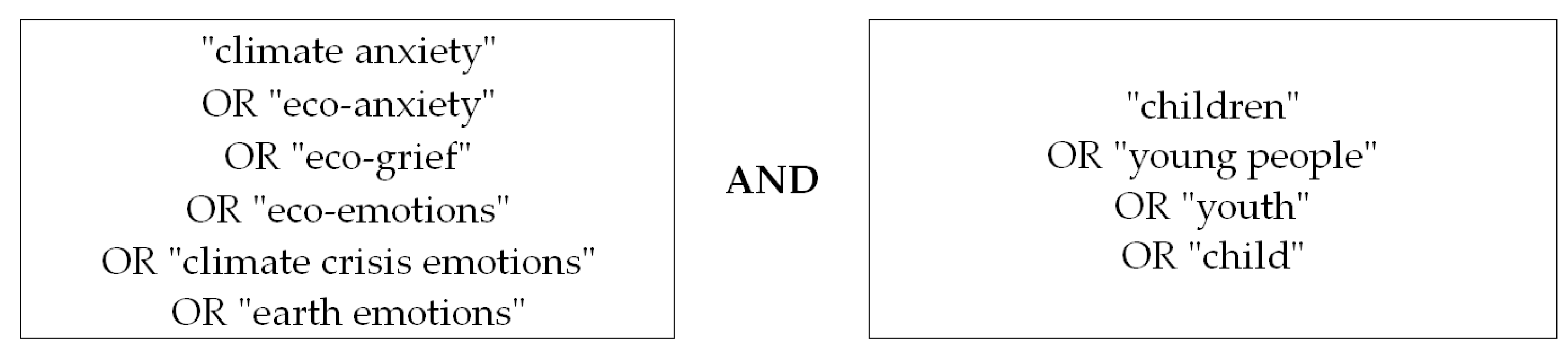

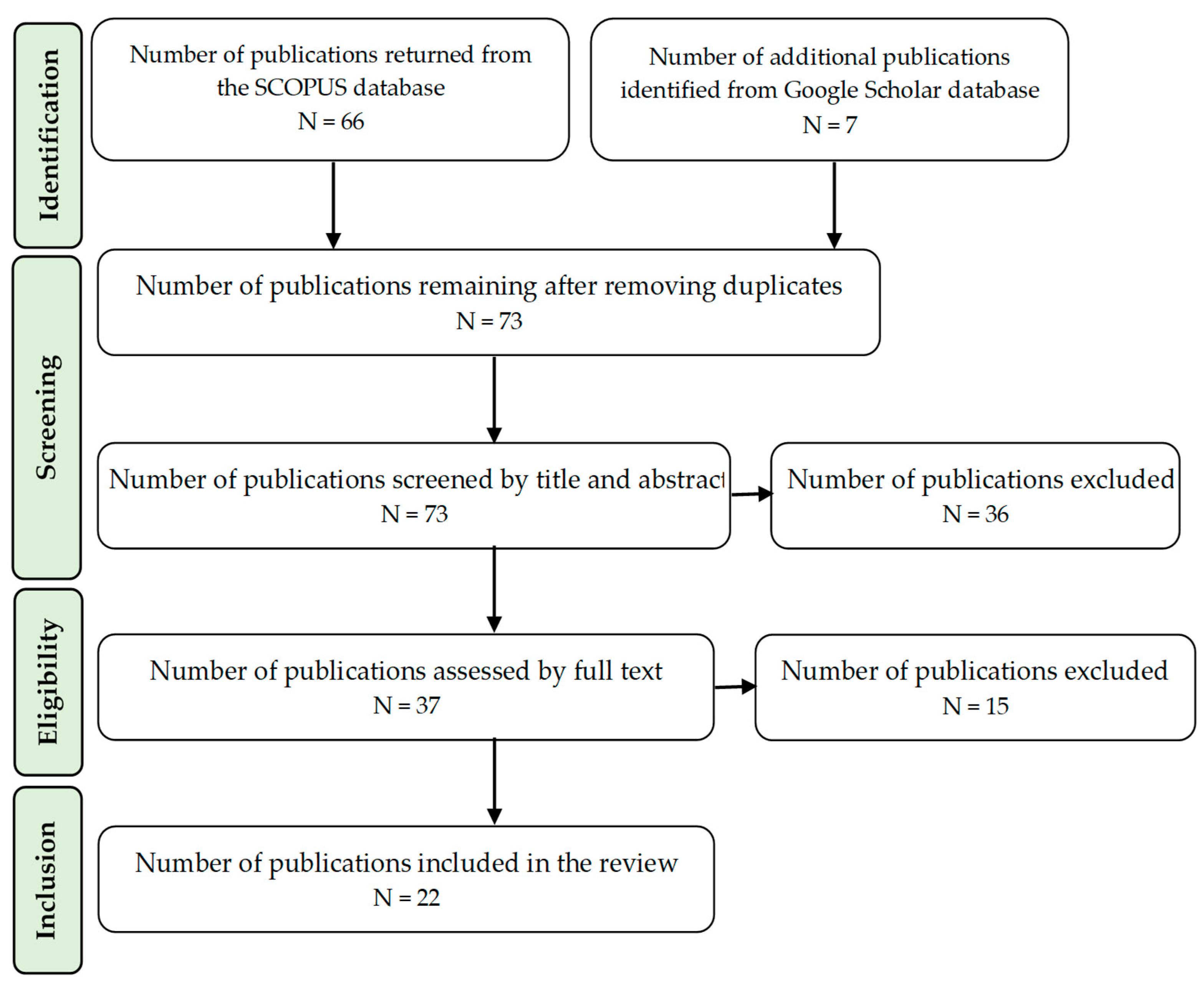

3.3. Literature Search Process

4. Results

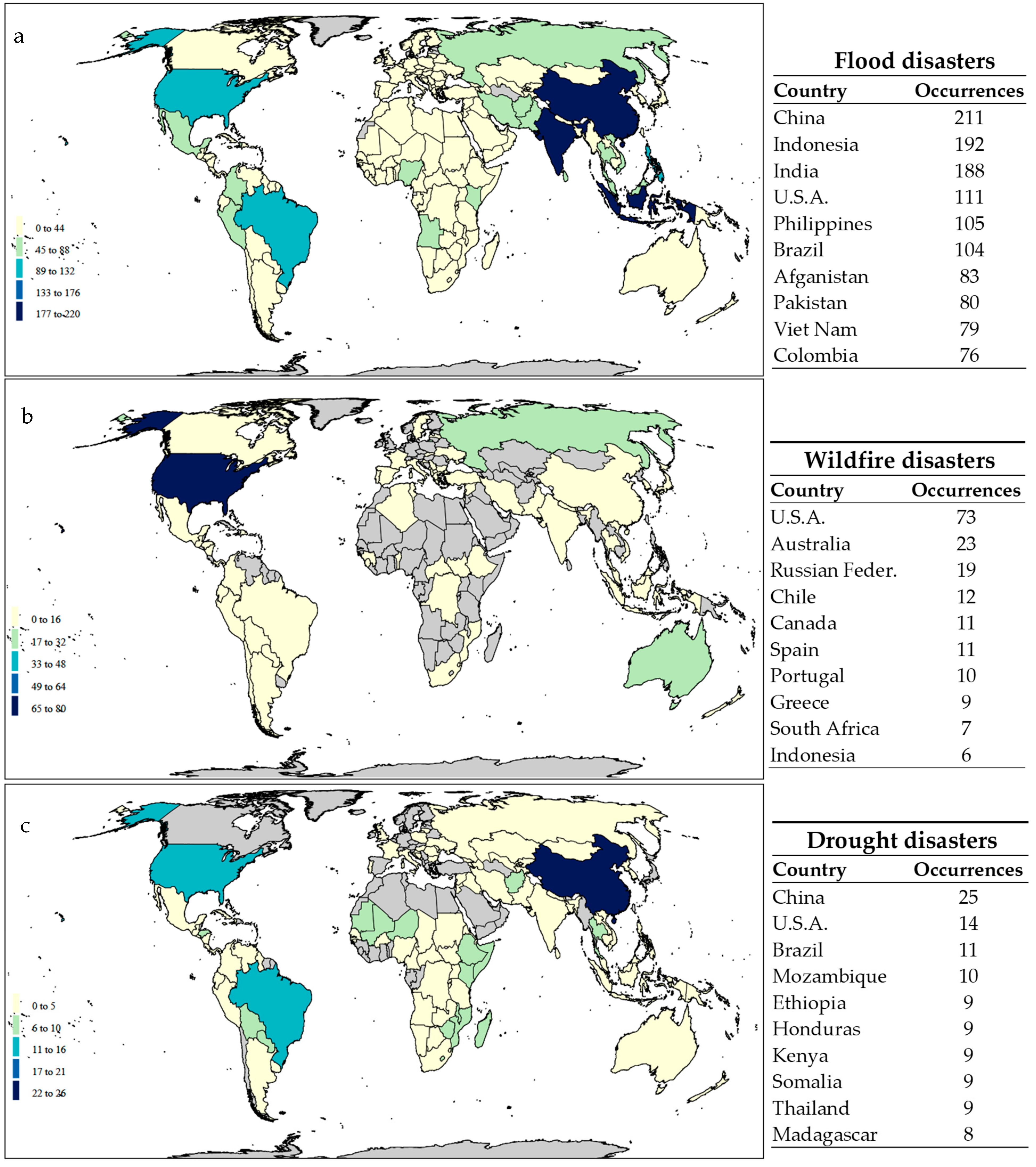

4.1. Generation Z Worries in the Global North and Suffers in the Global South

4.2. Generation Z Acts against Climate Change

4.3. The Existential Dimension of Eco-Anxiety

5. Discussion

6. Concluding Remarks

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- United Nations. The Climate Crisis—A Race We can Win. Available online: https://www.un.org/en/un75/climate-crisis-race-we-can-win (accessed on 20 May 2023).

- Kingsnorth, P. Confessions of a Recovering Environmentalist and Other Essays; Graywolf Press: Minneapolis, MN, USA, 2017; p. 286. [Google Scholar]

- Morton, T. Dark Ecology: For a Logic of Future Coexistence; Columbia University Press: New York, NY, USA, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Hickman, C.; Marks, E.; Pihkala, P.; Clayton, S.; Lewandowski, R.E.; Mayall, E.E.; Wray, B.; Mellor, C.; van Susteren, L. Climate anxiety in children and young people and their beliefs about government responses to climate change: A global survey. Lancet Planet. Health 2021, 5, e863–e873. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ogunbode, C.A.; Doran, R.; Hanss, D.; Ojala, M.; Salmela-Aro, K.; van den Broek, K.L.; Bhullar, N.; Aquino, S.D.; Marot, T.; Schermer, J.A.; et al. Climate anxiety, wellbeing and pro-environmental action: Correlates of negative emotional responses to climate change in 32 countries. J. Environ. Psychol. 2022, 84, 101887. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crutzen, P.J. Geology of mankind. Nature 2002, 415, 23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Albrecht, G. ‘Solastalgia’. A new concept in health and identity. PAN Philos. Act. Nat. 2005, 3, 41–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Albrecht, G.; Sartore, G.-M.; Connor, L.; Higginbotham, N.; Freeman, S.; Kelly, B.; Stain, H.; Tonna, A.; Pollard, G. Solastalgia: The distress caused by environmental change. Australas. Psychiatry 2007, 15, S95–S98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lertzman, R. Environmental Melancholia: Psychoanalytic Dimensions of Engagement; Routledge: East Sussex, UK; New York, NY, USA, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- UNICEF Office of Research. The Challenges of Climate Change: Children on the Front Line; UNICEF Office of Research: Florence, Italy, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Thunberg, G. The Climate Book: The Facts and the Solutions; Penguin Publishing Group: London, UK, 2022; p. 464. [Google Scholar]

- Rallis, A. Mighty Afrin: In the Time of Floods. (Documentary) 2023. Available online: http://angelosrallis.com/films/mighty-afrin/ (accessed on 15 June 2023).

- Hart, R.A. Children’s Participation: The Theory and Practice of Involving Young Citizens in Community Development and Environmental Care; Routledge: London, UK, 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Hickman, C. We need to (find a way to) talk about… Eco-anxiety. J. Soc. Work. Pract. 2020, 34, 411–424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pihkala, P. Anxiety and the ecological crisis: An analysis of eco-anxiety and climate anxiety. Sustainability 2020, 12, 7836. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boluda-Verdu, I.; Senent-Valero, M.; Casas-Escolano, M.; Matijasevich, A.; Pastor-Valero, M. Fear for the future: Eco-anxiety and health implications, a systematic review. J. Environ. Psychol. 2022, 84, 101904. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clayton, S.; Manning, C.; Krygsman, K.; Speiser, M. Mental Health and our Changing Climate: Impacts, Implications, and Guidance; American Psychological Association and ecoAmerica: Washington, DC, USA, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Pihkala, P. Eco-Anxiety, Tragedy, and Hope: Psychological and spiritual dimensions of climate change. Zygon® 2018, 53, 545–569. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pihkala, P. Eco-anxiety and environmental education. Sustainability 2020, 12, 10149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ray, S.J. A Field Guide to Climate Anxiety: How to Keep Your Cool on a Warming Planet; University of California Press: Oakland, CA, USA, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Clayton, S. Climate anxiety: Psychological responses to climate change. J. Anxiety Disord. 2020, 74, 102263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Clayton, S.; Karazsia, B.T. Development and validation of a measure of climate change anxiety. J. Environ. Psychol. 2020, 69, 101434. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clayton, S.D.; Pihkala, P.; Wray, B.; Marks, E. Psychological and emotional responses to climate change among young people worldwide: Differences associated with gender, age, and country. Sustainability 2023, 15, 3540. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brophy, H.; Olson, J.; Paul, P. Eco-anxiety in youth: An integrative literature review. Int. J. Ment. Health Nurs. 2022, 32, 633–661. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Léger-Goodes, T.; Malboeuf-Hurtubise, C.; Hurtubise, K.; Simons, K.; Boucher, A.; Paradis, P.-O.; Herba, C.M.; Camden, C.; Généreux, M. How children make sense of climate change: A descriptive qualitative study of eco-anxiety in parent-child dyads. PLoS ONE 2023, 18, e0284774. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Léger-Goodes, T.; Malboeuf-Hurtubise, C.; Mastine, T.; Généreux, M.; Paradis, P.-O.; Camden, C. Eco-anxiety in children: A scoping review of the mental health impacts of the awareness of climate change. Front. Psychol. 2022, 13, 872544. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramadan, R.; Randell, A.; Lavoie, S.; Gao, C.X.; Manrique, P.C.; Anderson, R.; McDowell, C.; Zbukvic, I. Empirical evidence for climate concerns, negative emotions and climate-related mental ill-health in young people: A scoping review. Early Interv. Psychiatry 2023, 17, 537–563. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coffey, Y.; Bhullar, N.; Durkin, J.; Islam, M.S.; Usher, K. Understanding eco-anxiety: A systematic scoping review of current literature and identified knowledge gaps. J. Clim. Change Health 2021, 3, 100047. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gislason, M.K.; Kennedy, A.M.; Witham, S.M. The interplay between social and ecological determinants of mental health for children and youth in the climate crisis. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 4573. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pihkala, P. Eco-anxiety and pastoral care: Theoretical considerations and practical suggestions. Religions 2022, 13, 192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mayes, E. Young People Learning Climate Justice: Education Beyond Schooling Through Youth-Led Climate Justice Activism. In Handbook of Children and Youth Studies; Wyn, J., Cahill, H., Cuervo, H., Eds.; Springer: Singapore, 2023; pp. 1–14. [Google Scholar]

- Pickard, S. Young environmental activists are doing it themselves. Political Insight 2019, 10, 4–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pickard, S. Young environmental activists and Do-It-Ourselves (DIO) politics: Collective engagement, generational agency, efficacy, belonging and hope. J. Youth Stud. 2022, 25, 730–750. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oermann, M.H.; Knafl, K.A. Strategies for completing a successful integrative review. Nurse Author Ed. 2021, 31, 65–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dhollande, S.; Taylor, A.; Meyer, S.; Scott, M. Conducting integrative reviews: A guide for novice nursing researchers. J. Res. Nurs. 2021, 26, 427–438. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Patrick, R.; Snell, T.; Gunasiri, H.; Garad, R.; Meadows, G.; Enticott, J. Prevalence and determinants of mental health related to climate change in Australia. Aust. N. Z. J. Psychiatry 2023, 57, 710–724. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Strife, S.J. Children’s environmental concerns: Expressing ecophobia. J. Environ. Educ. 2012, 43, 37–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jones, V.; Whitehouse, S. “It Makes Me Angry. REALLY Angry”: Exploring Emotional Responses to Climate Change Education. J. Soc. Sci. Educ. 2021, 20, 93–119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aruta, J.J.B.R. Mental health efforts should pay attention to children and young people in climate-vulnerable countries. Child Adolesc. Ment. Health 2022, 27, 321–322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aruta, J.J.B.R.; Simon, P.D. Addressing climate anxiety among young people in the Philippines. Lancet Planet. Health 2022, 6, e81–e82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coppola, I.; Pihkala, P. Complex dynamics of climate emotions among environmentally active Finnish and American young people. Front. Political Sci. 2023, 4, 160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lehtonen, A.; Pihkala, P. Encounters with climate change and its psychosocial aspects through performance making among young people. Environ. Educ. Res. 2021, 27, 743–761. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gunasiri, H.; Wang, Y.; Watkins, E.-M.; Capetola, T.; Henderson-Wilson, C.; Patrick, R. Hope, coping and eco-anxiety: Young people’s mental health in a climate-impacted Australia. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 5528. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Galway, L.P.; Field, E. Climate emotions and anxiety among young people in Canada: A national survey and call to action. J. Clim. Chang. Health 2023, 9, 100204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, D.M.; Sales, J.; Williams, A.; Munro, S. Pregnancy intentions of young women in Canada in the era of climate change: A qualitative auto-photography study. BMC Public Health 2023, 23, 766. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ojala, M. How do children cope with global climate change? Coping strategies, engagement, and well-being. J. Environ. Psychol. 2012, 32, 225–233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Diffey, J.; Wright, S.; Uchendu, J.O.; Masithi, S.; Olude, A.; Juma, D.O.; Anya, L.H.; Salami, T.; Mogathala, P.R.; Agarwal, H.; et al. “Not about us without us”—The feelings and hopes of climate-concerned young people around the world. Int. Rev. Psychiatry 2022, 34, 499–509. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Helm, S.; Kemper, J.A.; White, S.K. No future, no kids–no kids, no future? An exploration of motivations to remain childfree in times of climate change. Popul. Environ. 2021, 43, 108–129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simon, P.D.; Pakingan, K.A.; Aruta, J.J.B.R. Measurement of climate change anxiety and its mediating effect between experience of climate change and mitigation actions of Filipino youth. Educ. Dev. Psychol. 2022, 39, 17–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Uchendu, J.O. Eco-anxiety and its divergent power holds: A youth climate activist’s perspective. S. Afr. J. Psychol. 2022, 52, 545–547. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bowman, B.; Pickard, S. Peace, protest and precarity: Making conceptual sense of young people’s non-violent dissent in a period of intersecting crises. J. Appl. Youth Stud. 2021, 4, 493–510. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pickard, S.; Bowman, B.; Arya, D. “We are radical in our kindness”: The political socialisation, motivations, demands and protest actions of young environmental activists in Britain. Youth Glob. 2020, 2, 251–280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kowasch, M.; Cruz, J.P.; Reis, P.; Gericke, N.; Kicker, K. Climate youth activism initiatives: Motivations and aims, and the potential to integrate climate activism into ESD and transformative learning. Sustainability 2021, 13, 11581. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Moor, J.; Uba, K.; Wahlström, M.; Wennerhag, M.; De Vydt, M. Protest for a Future II: Composition, Mobilization and Motives of the Participants in Fridays for Future Climate Protests on 20–27 September, 2019, in 19 Cities around the World. Available online: https://urn.kb.se/resolve?urn=urn%3Anbn%3Ase%3Ash%3Adiva-40271 (accessed on 10 May 2023).

- Bowman, B. Imagining future worlds alongside young climate activists: A new framework for research. Fenn. Int. J. Geogr. 2019, 197, 295–305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Woodbury, Z. Climate Trauma, Reconciliation & Recovery. Independently Published. Available online: https://www.academia.edu/74639386/Climate_Trauma_Reconciliation_and_Recovery (accessed on 10 June 2023).

- Ferrarello, S. Solastalgia: Climatic Anxiety—An Emotional Geography to Find Our Way Out. J. Med. Philos. A Forum Bioeth. Philos. Med. 2023, 48, 151–160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Inclusion Criteria | Exclusion Criteria |

|---|---|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Thematic Categories of the Research Results | Sub-Categories of the Research Results | References |

|---|---|---|

| Generation Z worries in the Global North and suffers in the Global South |

| [4,25,36,37,38,39,40,41,42,43,44,45,46,47,49,50] |

| ||

| ||

| ||

| ||

| Generation Z acts against climate change |

| [32,33,38,41,54,55] |

| ||

| The existential dimension of eco-anxiety |

| [4,20,44,45] |

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Tsevreni, I.; Proutsos, N.; Tsevreni, M.; Tigkas, D. Generation Z Worries, Suffers and Acts against Climate Crisis—The Potential of Sensing Children’s and Young People’s Eco-Anxiety: A Critical Analysis Based on an Integrative Review. Climate 2023, 11, 171. https://doi.org/10.3390/cli11080171

Tsevreni I, Proutsos N, Tsevreni M, Tigkas D. Generation Z Worries, Suffers and Acts against Climate Crisis—The Potential of Sensing Children’s and Young People’s Eco-Anxiety: A Critical Analysis Based on an Integrative Review. Climate. 2023; 11(8):171. https://doi.org/10.3390/cli11080171

Chicago/Turabian StyleTsevreni, Irida, Nikolaos Proutsos, Magdalini Tsevreni, and Dimitris Tigkas. 2023. "Generation Z Worries, Suffers and Acts against Climate Crisis—The Potential of Sensing Children’s and Young People’s Eco-Anxiety: A Critical Analysis Based on an Integrative Review" Climate 11, no. 8: 171. https://doi.org/10.3390/cli11080171

APA StyleTsevreni, I., Proutsos, N., Tsevreni, M., & Tigkas, D. (2023). Generation Z Worries, Suffers and Acts against Climate Crisis—The Potential of Sensing Children’s and Young People’s Eco-Anxiety: A Critical Analysis Based on an Integrative Review. Climate, 11(8), 171. https://doi.org/10.3390/cli11080171