1. Introduction

This paper draws inspiration from the work of

Juselius (

2021) regarding the cointegration method and its variations within econometrics. Understanding the temporal behaviour of economic factors is essential for both theoretical and applied research. The objectives of this study are twofold: firstly, to develop a robust econometric model for tourism-related inflation based on price dynamics and secondly, to apply and expand upon the methodological insights presented by

Ross (

2021). Furthermore, this study contributes to the ongoing discussions surrounding methodology in economics that heavily depend on data obtained from secondary sources (

Couix, 2021).

The primary objective is to advance time series analysis in macroeconometric research by building on the foundations of

Haldrup (

1998);

Cubadda (

1999);

Busetti (

2006);

Fisher et al. (

2015);

Rahul et al. (

2018);

Ross (

2021);

Gil-Alana et al. (

2021) and others. In the context of tourism price dynamics, the methodological contributions of Juselius have been applied and critically assessed by

Archontakis and Mosconi (

2021). Building on this line of work, we focus on the role of seasonal effects, higher-order integration, and misspecification patterns in shaping tourism inflation (

Braun et al., 2013). The analysis concentrates on the Eurozone, using Slovenia as a case study, and applies an

I(2) cointegration framework to model long- and short-run interactions between tourism prices and inflation.

Section 3 outlines the methodological framework and data and presents the empirical

I(2) model.

Although the research gap has been acknowledged in the literature, most contributions remain theoretical, with relatively fewer applied case studies. We address this gap by demonstrating the importance of higher-order integrated variables in the dynamics of aggregate prices. While the GDP growth rate is typically treated as I(0) and inflation as I(1), prices are often I(2), requiring more sophisticated econometric treatment.

The novelty and contribution of this study lie in the application of an

I(2) cointegration framework to estimate the long- and short-run dynamics of tourism-related prices. Econometric methods are used to allow price spreads and seasonal effects to vary in response to shocks or to remain persistent during exceptional shocks (

Alghalith, 2007). A key contribution is the extension of theory and applied computational economics by explicitly modelling spillovers and persistent deviations in integrated markets.

The analysis focuses on the Eurozone, with a case study of Slovenia using monthly statistical time series data. Special attention is given to two sets of shocks: (i) Slovenia’s accession to the European Union in 2004 and adoption of the euro in 2007 and (ii) episodes of high food prices, economic crises, and subsequent recovery. The hospitality sector, as the most significant part of the tourism industry, provides the empirical setting.

The article’s broader goal is to examine how financial and price volatilities can be treated in econometrics beyond conventional misspecification tests. The motivation stems from ex-ante econometric modelling aimed at predicting future events that may have potentially adverse effects on economies and societies (

Gričar et al., 2021). The remainder of the paper is structured as follows:

Section 2 reviews the literature and develops the research questions;

Section 3 outlines the methods and data;

Section 4 presents the empirical results; and

Section 5 discusses the findings and concludes this paper.

2. Literature Review

The dynamics of tourism price inflation can be examined as a further development of the work by

Archontakis and Mosconi (

2021), who applied the

I(2) cointegration framework—a methodology available since the early 1990s but still underutilised in empirical applications (

Juselius, 2006;

Kongsted, 2005). As

Juselius (

2006) notes, cointegration provides a systematic process for capturing interactions among nonstationary variables, and the framework developed by Johansen & Juselius has become one of the most influential in modern econometrics. This research builds on that foundation by providing a step-by-step procedure for implementing

I(2) modelling in applied contexts, thereby establishing a robust statistical framework for predictive macroeconometrics.

At the same time, several studies have highlighted persistent misspecification problems in econometric time series (

Gjelsvik et al., 2020;

Harvey et al., 2012), including unreliable inference (

Trafimow, 2019), the treatment of shocks (

Pollock, 2020), and incorrect variable selection (

Błażejowski et al., 2020). Addressing these issues is crucial in tourism economics, where prices play a critical role in determining both industrial performance and financial stability. The application of an I(2) procedure to tourism price dynamics thus offers a methodological advance with strong practical relevance.

Distinct forces shape tourism price behaviour. First, the sector has been among the most severely affected by various crises (

Plzáková & Smeral, 2021), which have generated short-term ex-post inflationary pressures, echoing earlier findings on price volatility in the hospitality sector (

Gričar & Bojnec, 2013). Second, tourism is one of the most dynamic global industries (

Gričar & Bojnec, 2013), yet predictions in this field often lack robustness (

Teixeira & Fernandes, 2014). This underscores the importance of using advanced econometric tools to isolate variables and model persistent deviations. Building on earlier work (

Gričar & Bojnec, 2013;

Pacifico, 2021), we apply a vector autoregressive model with

I(2) integration, following the theoretical developments of

Franchi and Paruolo (

2021).

In addition, this study addresses often neglected econometric features. For instanc, normality in residuals has mainly been overlooked in applied time series (

Juselius, 2021), yet its treatment is crucial for reliable inference (

Braione & Scholtes, 2016;

Chen et al., 2021;

Desgagné & Lafaye de Micheaux, 2018). Similarly, recent advances in stationarity testing (

Hudecová et al., 2021) and autocorrelation procedures (

Vougas, 2021) provide complementary tools that strengthen the empirical framework.

Against this backdrop, our study extends the application of

I(2) cointegration to tourism and inflation in the Eurozone, with Slovenia as a case study. This approach not only integrates methodological rigour but also responds to rising concerns about inflation risk in the Eurozone (

Hein, 2017;

Ruth, 2021). By incorporating past shocks—such as EU accession, euro adoption, and food price surges—into the econometric framework, we aim to demonstrate how

I(2) cointegration improves predictive performance.

Building on earlier cointegration research in tourism (

Kulendran, 1996;

Dritsakis, 2004), this paper models both general consumer price indices (CPIs) and tourism-related input price indices (hospitality and food and beverages). These time series exhibit long and persistent deviations from linear trends, which the

I(2) framework captures more effectively than fractional alternatives. This enables us to evaluate the homogeneity of price behaviour between Slovenia and the wider Eurozone (

Gričar & Bojnec, 2018), offering new insights into market integration.

Building on these theoretical advances, the main research question is: How much does using an I(2) cointegration model enhance our understanding of the long- and short-term relationships between tourism prices and inflation in small open economies like Slovenia within the Eurozone?

3. Materials and Methods

This section introduces a theoretical framework on tourism and prices, presents the cointegrating model, and the data used.

3.1. Tourism and Prices—Theoretical Framework

Gričar and Bojnec (

2013) analyse inflation and price trends in the hospitality sector through time series models. Given that tourism has a significant impact on the Eurozone economy and that prices are crucial for determining income and profitability for firms, our goal is to examine the roles of prices and inflation in time series data projections. Notably, to date, no study has addressed this issue in advanced time series models for Eurozone countries. Several studies deal with prices and demand or prices and exchange rates or prices and oil shocks (

Ahumada & Cornejo, 2021;

Gričar & Bojnec, 2018;

Katircioglu et al., 2018;

Meo et al., 2018), but no study deals with prices in the context of

cointegration and exclusively with price treatments and inflation. We first review the existing empirical studies on price spillovers in tourism and then apply

cointegration in modelling time series in tourism to enrich the high quality of quantitative analyses in tourism. This can provide valuable in-depth evidence on price as an essential management tool for firms, as it is the primary determinant of income (

Gričar & Bojnec, 2018). Therefore, it is essential to accurately explore input and output prices as inflation, as an external variable, determines firms’ input costs and output prices (

Cranage, 2003).

Juselius (

2006) has recognised that inflation in the economy is an essential variable in the empirical work and data vector. Therefore, the model must be built with this aspect in mind. Following the idea of

Gričar and Bojnec (

2013), the econometric explanation of prices can be expressed as a data vector consistent with the framework of

Castle et al. (

2021), where each variable maintains the integration of the chosen order I(d). Building on this foundation, the econometric framework applies the

I(2) cointegrated (C) vector autoregressive (VAR) approach, extending the conventional

I(1) model to variables whose second differences are stationary. This structure enables a coherent analysis of long-run equilibria among price indices with persistent trends while accounting for short-run adjustments. It distinguishes between permanent and transitory components of inflation and tourism-related prices, ensuring both are adequately represented in the model. Deterministic elements, such as constants and linear trends, capture gradual structural shifts, whereas stochastic shocks describe short-term fluctuations. This framework provides the theoretical basis for the empirical specification developed in

Section 3.2.

3.2. The I(2) Cointegration Model

Building on the preceding theoretical framework, the empirical model applies

Johansen’s (

1992,

1995) representation of the

I(2) CVAR system. This formulation extends the conventional

I(1) model by allowing variables whose second differences are stationary, thereby capturing both

I(1) and

I(2) components within the same structure. The model separates long-run equilibrium relations among price levels from the short-run dynamics of their changes, enabling analysis of how persistent price trends and transitory shocks interact. Deterministic terms, such as constants and linear trends, account for gradual structural shifts, while the stochastic error structure represents short-term fluctuations around equilibrium. This

I(2) framework is particularly suitable for modelling the joint evolution of tourism-related and consumer prices in Slovenia and the Eurozone, where sustained nominal growth and cross-market spillovers create higher-order stochastic trends. It thus provides the theoretical foundation for the empirical estimation that follows.

A VAR model incorporating

lags can be expressed as:

where

contains a vector of variables for period

t,

is a vector of dummy variables that may be included and

is an error term. It can be reformulated to a vector equilibrium correction model, such as:

where

,

,

(p is the number of variables in the data vector) for

, and

is given.

is a vector of dummy variables (if included), and

and

are constants. The trend is restricted to lie within the cointegrating space to avoid quadratic trends (i.e.,

and

). To simplify this, the trend is restricted to

, and the notation

is omitted. Additionally, the Vector Error Correction Model (VECM) described in (2) can be expressed in terms of acceleration rates, changes, and levels. For a lag length of

, this yields

This can be written using the maximum likelihood parameterisation (see

Johansen (

1992)), yielding

where

contains the adjustment coefficients, whilst

represents the parameters related to the long-run relationships among the

variables in the system. If the lag length is k = 3, we also have to add the term

to (3) and (4) with a negative sign, where

. This term will then represent short-run effects; see

Johansen (

1995). Following

Rahbek et al. (

1999) to avoid quadratic trends, the trend is restricted to be in

and the constant to be in

. See, e.g.,

Juselius (

2006, Chapter 17) for a more detailed description of the

I(2) cointegrated VAR model.

Johansen’s (

1992,

1995) representation of the

I(2) model extends the VECM to systems where some variables are integrated of order two. In such settings, the second-differenced vector

can be expressed as

where

captures the

I(1) cointegration relationships, and

represents the long-run

I(2) relations. The matrices

and

contain the adjustment coefficients that link deviations from equilibrium to short-run dynamics. This formulation enables the decomposition of the system into transient and permanent components, distinguishing between stationary relations in the first and second differences. The representation, therefore, generalises the standard

I(1) VECM to handle higher-order stochastic trends in non-stationary macroeconomic and price processes.

3.3. Data

We utilise six monthly price variables, unadjusted for seasonality, covering the period from January 2000 to December 2017. These are: the input costs for the hospitality industry include Slovenian prices (

), prices in the Eurozone’s hospitality sector (

), Slovenian consumer prices (

), consumer prices across the Eurozone (

), Slovenian food and beverages prices (

), and food and beverage prices in the rest of the Eurozone (

) as input costs for the hospitality industry. The original VAR method is used. Data are sourced from the Statistical Office of the Republic of Slovenia (

SORS, 2021) and

Eurostat (

2021).

Figure 1 displays the with base-10 indices, with January 2000 set as the baseline at 100.

Figure 1 shows the evolution of six-monthly price indices from 2000 to 2017, covering hospitality, consumer, and food and beverage prices for Slovenia and the Eurozone. All indices demonstrated clear upward trends, aligning with the long-term nominal price growth seen in both economies. The Slovenian indices (IPHI, CPI, IFB) experienced slightly stronger cumulative increases compared to the Eurozone indices, reflecting faster price convergence and domestic service-sector dynamics. Conversely, the Eurozone indices (IPHIEA, CPIEA, IFBEA) followed more stable paths, consistent with the larger and more diverse structure of the overall market. Despite some short-term fluctuations, all series showed significant persistence and co-movement, indicating a high level of integration between national and regional price systems. The combined movements of these indices supported using the

I(2) cointegration framework to analyse long- and short-term adjustments in tourism-related and consumer prices across both economies.

4. Results

4.1. Estimating the Unrestricted I(2) Model

By estimating a VAR(4) model, we obtain a model that is sufficiently well specified. The misspecification tests are shown in

Table 1.

As shown in

Table 1, residual diagnostics revealed minor deviations from normality and some evidence of ARCH effects. Additional analysis using residual plots, recursive estimates, and difference-of-log transformations in OxMetrics 8 (

J. Doornik & Juselius, 2017). suggested that these issues were primarily due to a few mild outliers around the 2008–2009 financial crisis and 2020, rather than structural breaks. Incorporating level-shift dummies and re-estimating the model produced nearly identical cointegration ranks and short-run dynamics. These results confirm that the minor non-normality and weak ARCH effects did not significantly impact the robustness of the findings.

There is no residual autocorrelation of orders 1 and 2 in the VAR(4) model, but some variables show ARCH effects and non-normality. Statistical inference is robust to moderate ARCH effects (

Rahbek et al., 2002), but non-normality may lead to problems. However, the non-normality appears to be primarily caused by kurtosis, rather than skewness. This is less of a concern for inference (

Juselius, 2006, Chapter 4.3), such that the non-normality we find in the residuals here is not sufficient to conclude that our model is not well specified. Including various dummy variables to control for events that may occur outside the model did not correct the non-normality caused by kurtosis or the ARCH effects; therefore, we proceed with the VAR(4) model without dummy variables.

As seen in

Table 2, the rank test suggests a rank of r = 2 and

I(2) trends when starting with the model in the top left corner of the table and going to the right before going to the next line. The first model being significant (having a

p-value above 0.05), is the model with a rank of r = 2 and

I(2) trends. We can thereby simplify the model since we find that there are two long-run multicointegrating relationships in the data, and two

I(2) trends, such that the model has reduced rank. Hence, we use this model in the analysis by reducing the rank to 2 and incorporating 2

I(2) trends.

4.2. The I(2) Model with Reduced Rank and Over-Identifying Restrictions

When estimating the reduced-rank model, we impose restrictions to obtain the identified long-run structure in

. First, we imposed restrictions that resulted in one beta vector for Slovenia and one for the rest of the Eurozone. However, these restrictions could not be accepted at a significance level higher than 3.3%, suggesting spillovers between Slovenia and the rest of the Eurozone By including the hospitality price index in the Eurozone for the long-run relationship related to Slovenia, we have restrictions that cannot be rejected (at the highest level of significance compared to including other variables in one of the two beta vectors). The identifying restrictions involves removing euro area CPI and food and beverage prices from the first cointegrating relationship and removing all Slovenian variables from the second cointegrating relationship. The first relationship can thus be interpreted as a relationship between Slovenian variables, which also includes euro area hospitality prices, while the second relationship can be interpreted as a relationship specific to the euro area. Since the euro area hospitality prices are significant in the first relationship, this indicates that long-run relationship exists between prices in Slovenia and the Eurozone. The identified structure suggests that hospitality prices in the rest of the Eurozone are important for hospitality prices in Slovenia in the long run. Estimates are shown in

Table 3. These restrictions cannot be rejected at a

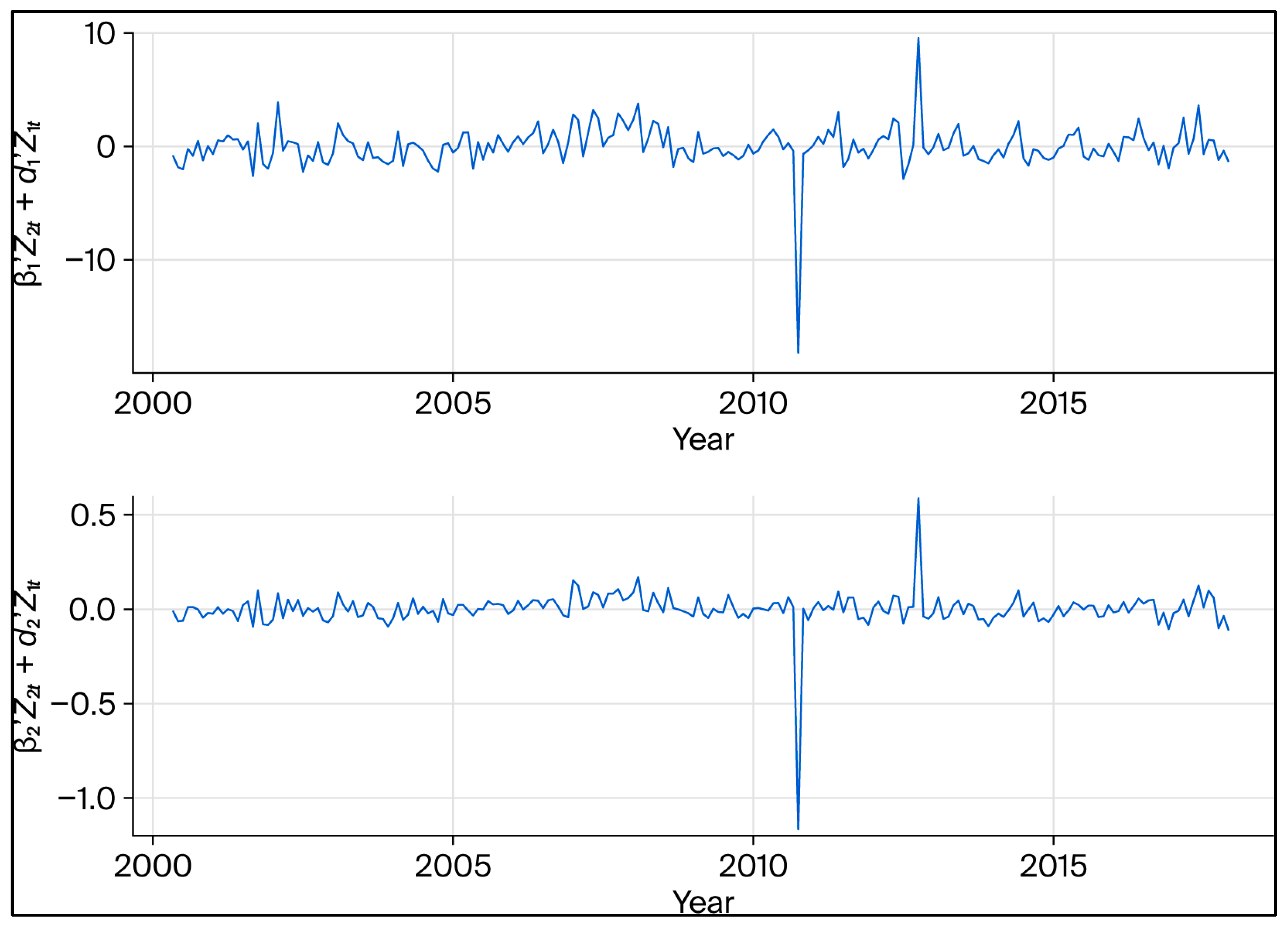

p-value of 0.37. The two cointegrating relationships (with identifying restrictions applied) are also shown in

Figure 2, where we observe stationary relationships with some outliers.

To further investigate the pushing and pulling forces of the variables in our system and understand how Slovenia and the rest of the Eurozone interact with each other in the long, medium, and short term, we examine the estimated parameters.

Suppose we label the first long-run relationship as the Slovenian and the second as the relationship for the rest of the Eurozone. In that case, we can look at whether the estimated products of < 0 and/or for error correction in the long run and for error-correcting in the medium run are given significant (or error increasing behaviour for the opposite inequality signs) to see which variables are error increasing or error-correcting the system, respectively.

For the Slovenian relationship (the first cointegrating relationship), we observe an error-increasing behaviour related to Slovenian CPI since 0 for this, while the Eurozone CPI is error increasing in the Eurozone relationship. Slovenian CPI and food and beverage prices are also error increasing in the medium run for the Slovenian relationship since for these, and food and beverage prices in the Eurozone are increasing error in the medium run for the Eurozone relationship for the same reason. Hence, Slovenian prices do not seem to influence the rest of the Eurozone, or vice versa, in the long or medium run related to the long-run relationships.

The stationary dynamic long-run relations

then become

for the Slovenian relationship and

for the rest of the Eurozone.

Equations (6) and (7) present the estimated stationary long-run relations obtained from the cointegrated I(2) system. The coefficients describe how hospitality prices in Slovenia and the Eurozone adjust to long-term equilibrium levels in response to movements in consumer and food-and-beverage prices, both domestically and regionally. The significant parameters confirm the existence of two stable cointegration relationships linking national and Eurozone price dynamics. The inclusion of deterministic terms and first-difference variables captures gradual structural shifts and short-run adjustments within the system. Overall, the estimated β-relations suggest a strong interdependence between the Slovenian and Eurozone price indices, consistent with the hypothesis of price convergence in integrated tourism and consumer markets.

4.3. Moving Average Representation

We can estimate the common trends and their loadings. They are shown in

Table 4.

From the common trends and their loadings in

Table 4, we observe from the alphas that the first

I(2) trend is generated from cumulated shocks to food and beverage prices, Euro Area hospitality prices and CPI both in Slovenia and the Eurozone and thereby represents an

I(2) trend related to general price levels in the entire Eurozone. However, this trend primarily affects Slovenian food and beverage prices and CPI, since these are the estimated beta coefficients with the highest loadings at 0.06. The second

I(2) trend is generated from all Euro area price indices and primarily affects Slovenian hospitality prices, as well as CPI in Slovenia and the Eurozone and Slovenian food and beverage prices to a lesser extent. This suggests that hospitality, as well as food and beverage prices in the Eurozone, may impact Slovenian hospitality prices in the long run through twice-cumulated shocks.

4.4. Short-Run Effects

While there are few long-run effects between Slovenia and the rest of the Eurozone, there are more short-run effects, especially effects from Slovenia on the Eurozone. There are short-term effects on the Eurozone and the Slovenian CPI from the changes in Slovenian hospitality prices. The Eurozone’s food and beverage price index is affected by both Slovenian hospitality prices and Slovenian food and beverage prices in the short run. The estimated one-period effects on the acceleration rates are shown in

Table 5.

From

Table 5, we see significant short-run effects on Slovenian hospitality prices from hospitality prices in the rest of the Eurozone and Slovenian food and beverage prices, as well as food and beverage prices in the Eurozone from two months earlier. Food and beverage prices in the Eurozone impact Slovenian CPI and hospitality prices, while Slovenian food and beverage prices influence the Eurozone CPI. Hence Slovenian prices have a short-term impact on the rest of the Eurozone. This contrasts with the long- and medium-term effects, where Slovenia did not have a significant impact on the rest of the Eurozone, but rather, we observed effects from the Eurozone on Slovenia. There are thus significant short-term effects on prices in the rest of the Eurozone from the Slovenian restaurant industry. This may suggest a spillover effect of the Slovenian sector on the Eurozone, by Slovenian tourism demand having a cost-push effect on Eurozone prices.

5. Discussion

The study explores how using the I(2) cointegration framework can enhance the modelling of tourism prices and inflation dynamics between Slovenia and the broader Eurozone. By examining both long- and short-term relationships, it shows that the I(2) method effectively detects persistent deviations, spillover effects, and asymmetric adjustments across economies of different sizes and structures. This approach enables more precise identification of equilibrium relationships and short-term shocks that traditional I(1) methods might miss. As a result, the findings suggest that accounting for higher-order integration offers a better understanding of inflation transmission in tourism-dependent economies, directly addressing the research question and highlighting the relevance of the I(2) approach both methodologically and practically.

This study’s empirical findings offer fresh insights into the behaviour of tourism prices and inflation trends in Slovenia and the Eurozone, emphasising the significance of employing an I(2) cointegration framework. Although much of the existing tourism price research relies on I(1) methods, our results show that ignoring I(2) processes can conceal long-term equilibrium relationships and distort short-term spillover effects. The I(2) model effectively captures persistent deviations, shared trends, and seasonal shock interactions, providing a more comprehensive and dependable econometric foundation for assessing inflation risks in interconnected markets.

A key finding is the asymmetry between long-term and short-term impacts. Over the long run, Slovenian hospitality and input prices are primarily affected by Eurozone-wide shocks, reinforcing the significant influence of the larger integrated market. This supports the theoretical view that small, open economies adapt to macroeconomic conditions driven by their larger trading partners. Conversely, the short-term analysis shows that Slovenian prices have a tangible spillover effect on Eurozone consumer and hospitality prices. These results highlight the dual nature of small economies. Although they generally accept prices as given in the long run, they can temporarily induce shocks that spread through the regional system. In practice, price changes in Slovenian tourism sectors, particularly in food and beverages, can impact regional inflation, serving as a cost-push factor in both domestic and European markets.

This duality highlights the importance of differentiating between short-term and long-term effects when formulating policy. For Slovenian policymakers, the findings suggest that managing domestic tourism and hospitality prices cannot be performed in isolation from broader Eurozone conditions, as structural shocks from larger economies impact long-term price trends. Conversely, Slovenian authorities should also acknowledge that domestic tourism demand and pricing strategies can have a spillover effect, temporarily influencing Eurozone-wide inflation expectations. These results align with broader macroeconomic discussions about the relationship between small open economies and larger integrated systems, particularly within monetary unions where exchange rate adjustments are no longer possible.

The importance of this study extends beyond its methodological contributions. For Eastern European nations like Slovenia, empirical research on the factors influencing tourism prices remains scarce, despite the sector’s growing role in inflation patterns. The results presented here offer a valuable contribution, especially amid the 2022–2023 inflation spike, driven primarily by rising service and hospitality costs across Europe. By illustrating the link between tourism prices and overall price movements in the Eurozone, the study shows how cost increases in small, tourism-dependent economies can spread into broader inflation trends. Therefore, the I(2) framework enhances econometric analysis and provides a valuable basis for understanding recent inflation trends driven by the service sector.

In comparison to earlier research (

Cró & Martins, 2024;

Singh & Alam, 2024;

Xie et al., 2025;

Pérez-Rodríguez et al., 2024), this study presents several new contributions to the existing knowledge base. It is among the few empirical studies applying the

I(2) cointegration model to tourism price trends, illustrating its usefulness for analysing higher-order integration in service sectors. Additionally, it emphasises the crucial role of food and beverage prices as channels transmitting inflationary pressures in tourism-reliant economies, thereby broadening the understanding of sector-specific price interactions. Furthermore, it adds to hospitality management and competitiveness research by demonstrating how price changes in small open economies can affect regional inflation trends. Overall, these findings combine methodological innovation with practical policy implications, offering fresh insights into price movements within integrated European markets.

Although the

I(2) cointegration framework used in this study provides a strong foundation for analysing long- and short-term dynamics, several methodological extensions could further enhance future research. In particular, expanding the model to include tourism or consumer prices from other Mediterranean countries, such as Italy, Greece, or Spain, would enable a more accurate identification of regional spillover channels and could test whether the observed short-term causality from Slovenian to Eurozone food and beverage prices reflects a broader pattern in Southern Europe. Additionally, future work could analyse impulse–response functions within ±2 standard deviation bands and perform variance decomposition of residuals to assess the size and longevity of short-term shocks. Incorporating controls for wage dynamics could also improve the explanation of price adjustments, as labour costs influence both service inflation and tourism demand. Finally, sensitivity analyses with longer lag lengths or quarterly data could verify the stability of the VAR estimates and account for possible quadratic trends linked to seasonality in tourism prices (

Lozano et al., 2021).

6. Conclusions

The study’s conclusions align with the empirical evidence from I(2) cointegration and VAR analysis, directly answering the main research question about the interaction between tourism prices and inflation in the Eurozone.

This study employs an I(2) cointegration framework to analyse the dynamics of tourism and inflation in Slovenia and the Eurozone. It shows that higher-order integration is crucial for capturing persistent deviations and complex price interactions. The findings indicate that, in the long run, Eurozone-wide shocks are dominant, but Slovenian hospitality and input prices have significant short-term spillover effects on regional inflation. Neglecting I(2) structures could lead to model misspecification and misinterpretation of these dynamics.

The contributions are threefold: scientifically, this study offers a rare empirical application of I(2) cointegration in tourism economics, combining methodological innovation with practical evidence; for policy, it emphasises food and beverage prices as channels for inflationary pressures, highlighting the need for coordinated Eurozone responses; and practically, it guides hospitality price management and competitiveness, showing that pricing strategies must consider domestic shocks and market integration.

This study’s main methodological contribution is in showing how the I(2) cointegration framework improves econometric analysis, especially in settings with persistent deviations and multiple stochastic trends. Unlike traditional I(1) models, the I(2) approach captures more complex nonstationarity and structural changes, leading to more accurate long-term equilibria and short-term adjustments in interconnected markets. This allows us to analyse long-run, medium-run, and short-term effects in the same model framework. We may also use the nominal data directly, rather than transforming these variables by deflating or detrending them, which is often performed in empirical analysis. Hence, all of the information in the data is contained within the empirical framework. By explicitly modelling higher-order integration and spillover effects, it enhances macroeconometric theory and extends the use of cointegration to price system analysis. This advancement not only enhances predictive accuracy but also bridges the gap between theoretical econometrics and practical policy analysis. The framework provided can be adopted by other small, open economies or sectors with complex price interactions, making the findings more broadly applicable and improving the understanding of dynamic relationships in tourism and inflation research. The robust checks further confirmed that minor deviations from normality and weak ARCH effects had no material impact on the validity or stability of the estimated relationships.

Future research should expand to comparative analysis with other small Eurozone economies, explicitly model structural breaks such as EU accession and the adoption of the euro, and incorporate recent shocks, including COVID-19 and the inflation surge of the 2020s.

Overall, the study emphasises the methodological and practical importance of I(2) cointegration for understanding tourism prices and inflation. By integrating theory, empirical findings, and policy implications, it reinforces the value of advanced macroeconometric models in explaining the dynamics of tourism-dependent economies within the monetary union.

Author Contributions

Conceptualisation, S.G., B.K.K. and Š.B.; methodology, B.K.K.; software, B.K.K.; validation, S.G., B.K.K. and Š.B.; formal analysis, B.K.K.; investigation, S.G. and B.K.K.; resources, S.G.; data curation, S.G.; writing—original draft preparation, S.G. and B.K.K.; writing—review and editing, Š.B.; visualisation, S.G., B.K.K. and Š.B.; supervision, Š.B.; project administration, S.G. and B.K.K.; funding acquisition, Š.B. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by the Slovenian Research and Innovation Agency, grant numbers BI-NO/20/22-004 and BI-NO/25-27-003.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The data are publicly available, and the relevant sources are cited in the text. However, the data can be obtained by contacting the corresponding author.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Ahumada, H., & Cornejo, M. (2021). Are soybean yields getting a free ride from climate change? Evidence from Argentine time series data. Econometrics, 9(2), 24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alghalith, M. (2007). Estimation and econometric tests under price and output uncertainties. Applied Stochastic Models in Business and Industry, 23(6), 531–536. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Archontakis, F., & Mosconi, R. (2021). Søren Johansen and Katarina Juselius: A bibliometric analysis of citations through multivariate Bass models. Econometrics, 9(3), 30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Błażejowski, M., Kwiatkowski, J., & Kufel, P. (2020). BACE and BMA variable selection and forecasting for UK money demand and inflation with Gretl. Econometrics, 8(2), 21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Braione, M., & Scholtes, N. K. (2016). Forecasting value-at-risk under different distributional assumptions. Econometrics, 4(1), 3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Braun, M. T., Kuljanin, G., & DeShon, R. P. (2013). Spurious results in the analysis of longitudinal data in organizational research. Organizational Research Methods, 16(2), 302–330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Busetti, F. (2006). Tests of seasonal integration and cointegration in multivariate unobserved component models. Journal of Applied Econometrics, 21(4), 419–438. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Castle, J. L., Doornik, J. A., & Hendry, D. F. (2021). Selecting a model for forecasting. Econometrics, 9(3), 26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, L., Galvao, A. F., & Song, S. (2021). Quantile regression with generated regressors. Econometrics, 9(2), 16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Couix, Q. (2021). Models as “analytical similes”: On Nicholas Georgescu-Roegen’s contribution to economic methodology. Journal of Economic Methodology, 28(2), 165–185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cranage, D. (2003). Practical time series forecasting for the hospitality manager. International Journal of Contemporary Hospitality Management, 15(2), 86–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cró, S., & Martins, A. M. (2024). Tourism activity affects house price dynamics? Evidence for countries dependent on tourism. Current Issues in Tourism, 27(9), 1362–1380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cubadda, G. (1999). Common cycles in seasonal non-stationary time series. Journal of Applied Econometrics, 14(3), 273–291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Desgagné, A., & Lafaye de Micheaux, P. (2018). A powerful and interpretable alternative to the Jarque–Bera test of normality based on second-power skewness and kurtosis, using the Rao’s score test on the APD family. Journal of Applied Statistics, 45(13), 2307–2327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Doornik, J., & Juselius, K. (2017). Cointegration analysis of time series using CATS 3 for OxMetrics. Timberlake Consultants Ltd. [Google Scholar]

- Doornik, J. A., & Hansen, H. (1994). A practical test for univariate and multivariate normality. Discussion Paper. Nuffield College, University of Oxford. [Google Scholar]

- Dritsakis, N. (2004). Cointegration analysis of German and British tourism demand for Greece. Tourism Management, 25(1), 111–119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eurostat. (2021). Statistics database. Available online: https://ec.europa.eu/eurostat/data/database (accessed on 1 February 2025).

- Fisher, L. A., Huh, H.-S., & Pagan, A. R. (2015). Econometric methods for modelling systems with a mixture of I(1) and I(0) variables. Journal of Applied Econometrics, 31(5), 892–911. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Franchi, M., & Paruolo, P. (2021). Cointegration, root functions and minimal bases. Econometrics, 9(3), 31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gil-Alana, L. A., Mudida, R., Yaya, O. S., Osuolale, K. A., & Ogbonna, A. E. (2021). Mapping US presidential terms with S&P 500 index: Time series analysis approach. International Journal of Finance & Economics, 26(2), 1938–1954. [Google Scholar]

- Gjelsvik, M., Nymoen, R., & Sparrman, V. (2020). Cointegration and structure in Norwegian wage–price dynamics. Econometrics, 8(3), 29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Godfrey, L. G. (1988). Misspecification tests in econometrics: The Lagrange multiplier principle and other approaches (No. 16). Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Gričar, S., Baldigara, T., & Šugar, V. (2021). Sustainable determinants that affect tourist arrival forecasting. Sustainability, 13(17), 9659. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gričar, S., & Bojnec, Š. (2013). Inflation and hospitality industry prices: Time-series approach. Eastern European Economics, 51(3), 91–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gričar, S., & Bojnec, Š. (2018). Tourism price causalities: Case of an Adriatic country. International Journal of Tourism Research, 20(1), 82–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haldrup, N. (1998). An econometric analysis of I(2) variables. Journal of Economic Surveys, 12(5), 595–650. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harvey, D. I., Leybourne, S. J., & Taylor, A. M. R. (2012). Testing for unit roots in the presence of uncertainty over both the trend and initial condition. Journal of Econometrics, 169(2), 188–195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hein, E. (2017). An alternative macroeconomic policy approach for the Eurozone. In H. Herr, J. Priewe, & A. Watt (Eds.), Saving the Euro—Redesigning Euro Area economic governance (pp. 61–81). SE Publishing. [Google Scholar]

- Hetland, A., & Hetland, S. (2017). Short-term expectation formation versus long-term equilibrium conditions: The Danish housing market. Econometrics, 5(3), 40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hudecová, Š., Hušková, M., & Meintanis, S. G. (2021). Goodness-of-fit tests for bivariate time series of counts. Econometrics, 9(1), 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johansen, S. (1992). A representation of vector autoregressive processes integrated of order 2. Econometric Theory, 8(2), 188–202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johansen, S. (1995). Likelihood-based inference in cointegrated vector autoregressive models. Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Juselius, K. (2006). The cointegrated VAR model: Methodology and applications. Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Juselius, K. (2017). Using a theory-consistent CVAR scenario to test an exchange rate model based on imperfect knowledge. Econometrics, 5(3), 30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Juselius, K. (2021). Searching for a theory that fits the data: A personal research odyssey. Econometrics, 9(1), 5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Juselius, K., & Assenmacher, K. (2017). Real exchange rate persistence and the excess return puzzle: The case of Switzerland versus the US. Journal of Applied Econometrics, 32(6), 1145–1155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Juselius, K., & Dimelis, S. (2019). The Greek crisis: A story of self-reinforcing feedback mechanisms. Economics, 13(11), 1–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Juselius, K., & Stillwagon, J. R. (2018). Are outcomes driving expectations or the other way around? An I(2) CVAR analysis of interest rate expectations in the dollar/pound market. Journal of International Money and Finance, 83, 93–105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Katircioglu, S., Katircioglu, S., & Altun, O. (2018). The moderating role of oil price changes in the effects of service trade and tourism on growth: The case of Turkey. Environmental Science and Pollution Research, 25, 35266–35275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kivedal, B. K. (2023). Long run non-linearity in CO2 emissions: The I(2) cointegration model and the environmental Kuznets curve. Empirica, 50(4), 899–931. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kongsted, H. C. (2005). Testing the nominal-to-real transformation. Journal of Econometrics, 124(2), 205–225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kulendran, N. (1996). Modelling quarterly tourist flows to Australia using cointegration analysis. Tourism Economics, 2(3), 203–222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lozano, J., Rey-Maquieira, J., & Sastre, F. (2021). An integrated analysis of tourism seasonality in prices and quantities, with an application to the Spanish hotel industry. Journal of Travel Research, 60(7), 1581–1597. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meo, M. S., Chowdhury, M. A. F., Shaikh, G. M., Ali, M., & Sheikh, S. M. (2018). Asymmetric impact of oil prices, exchange rate, and inflation on tourism demand in Pakistan: New evidence from nonlinear ARDL. Asia Pacific Journal of Tourism Research, 23(4), 408–422. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pacifico, A. (2021). Structural panel Bayesian VAR with multivariate time-varying volatility to jointly deal with structural changes, policy regime shifts, and endogeneity issues. Econometrics, 9(2), 20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pérez-Rodríguez, J. V., Rachinger, H., & Suárez-Vega, R. (2024). Is peer-to-peer demand cointegrated at the listing level? Empirical Economics, 66(5), 2249–2275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Plzáková, L., & Smeral, E. (2021). Impact of the COVID-19 crisis on European tourism. Tourism Economics, 28(1), 91–109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pollock, D. S. G. (2020). Linear stochastic models in discrete and continuous time. Econometrics, 8(3), 35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rahbek, A., Christian Kongsted, H., & Jorgensen, C. (1999). Trend stationarity in the I(2) cointegration model. Journal of Econometrics, 90, 265–289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rahbek, A., Hansen, E., & Dennis, J. G. (2002). ARCH innovations and their impact on cointegration rank testing. Working Paper. Department of Theoretical Statistics, University of Copenhagen. [Google Scholar]

- Rahul, T., Balakrishnan, N., & Balakrishna, N. (2018). Time series with Birnbaum–Saunders marginal distributions. Applied Stochastic Models in Business and Industry, 34(4), 562–581. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ross, D. (2021). Economic methodology in 2020: Looking forward, looking back. Journal of Economic Methodology, 28(1), 32–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ruth, L. (2021). CPI inflation picks up further in June, increasing concerns over rising inflationary pressures. Perspectives. Available online: https://www.arbuthnotlatham.co.uk/sites/default/files/documents/19th%20July%202021.pdf (accessed on 1 February 2025).

- Singh, D., & Alam, Q. (2024). Is tourism expansion the key to economic growth in India? An aggregate-level time series analysis. Annals of Tourism Research Empirical Insights, 5(2), 100126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- SORS. (2021). Statistical office of the Republic of Slovenia. Database. Available online: http://pxweb.stat.si/pxweb/dialog/statfile2.asp (accessed on 1 February 2025).

- Teixeira, J. P., & Fernandes, P. O. (2014). Tourism time series forecast with artificial neural networks. Tékhne, 12(1–2), 26–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trafimow, D. (2019). A frequentist alternative to significance testing, p-values, and confidence intervals. Econometrics, 7(2), 26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vougas, D. V. (2021). Prais–Winsten algorithm for regression with second or higher order autoregressive errors. Econometrics, 9(3), 32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, J., Tveteraas, S., & Kidane, D. G. (2025). Assessing Airbnb’s impact on hotels through an analysis of price linkages. Tourism Economics. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |