5. Discussion

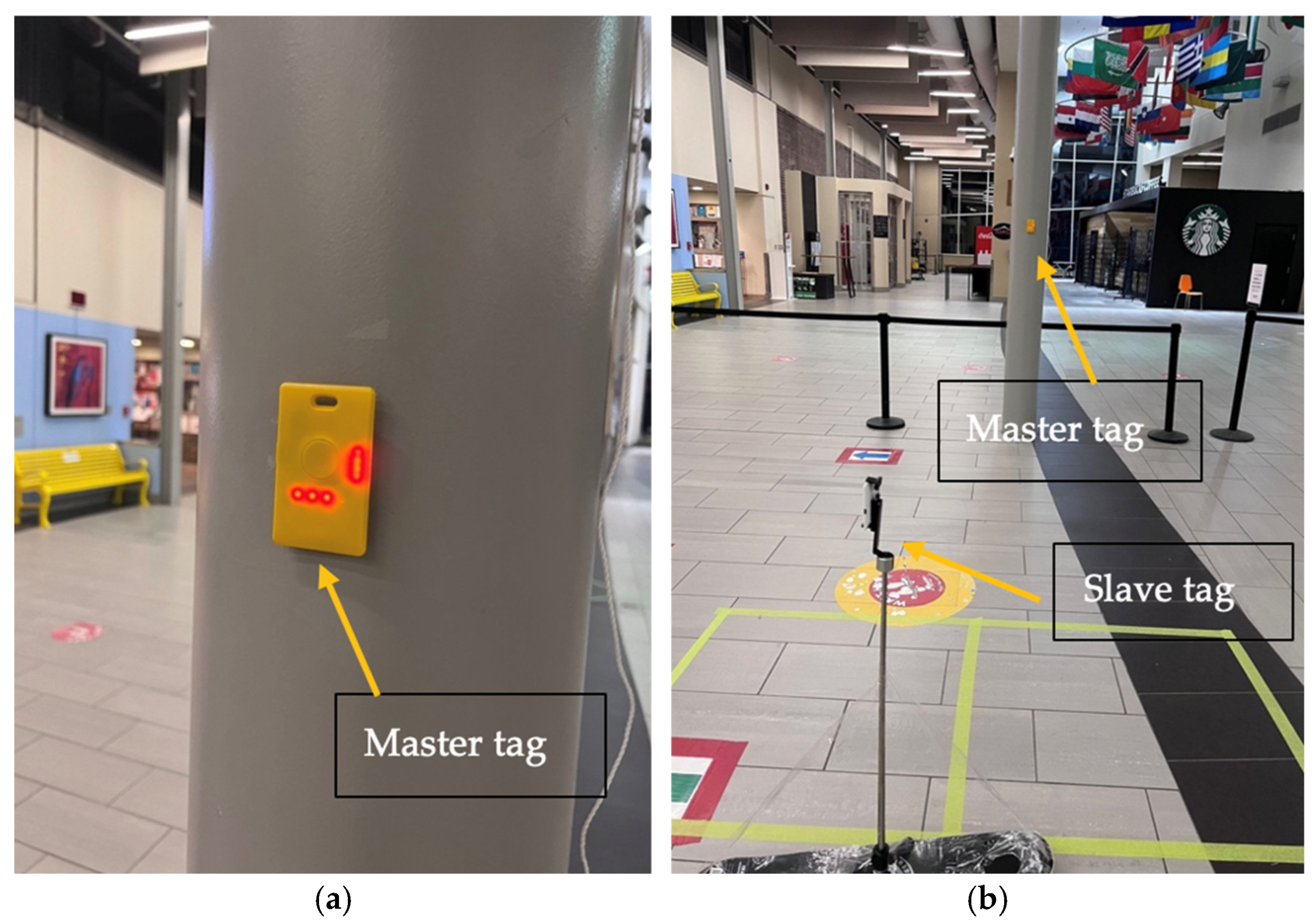

This study examined UWB technology through static and dynamic experiments conducted in an indoor controlled environment to estimate the PET. The purpose is to investigate the technology prior to utilizing it to study vehicle–pedestrian interactions. To avoid interference between devices, the study assigned two different PAN IDs to have two independent system networks. However, the study reported inaccurate distance measurements because the tags still detected PAN IDs from other networks and filtered out unwanted detections, leading to ranging delays. Wang, B et al. [

55] proposed a self-organizing network algorithm for UWB positioning systems to resolve challenges related to interference between multiple tags in close proximity. The study claims that the anchor dynamically manages PAN IDs by monitoring exchange messages and regenerating PAN IDs when interference is detected. Therefore, this needs to be investigated in depth in future research.

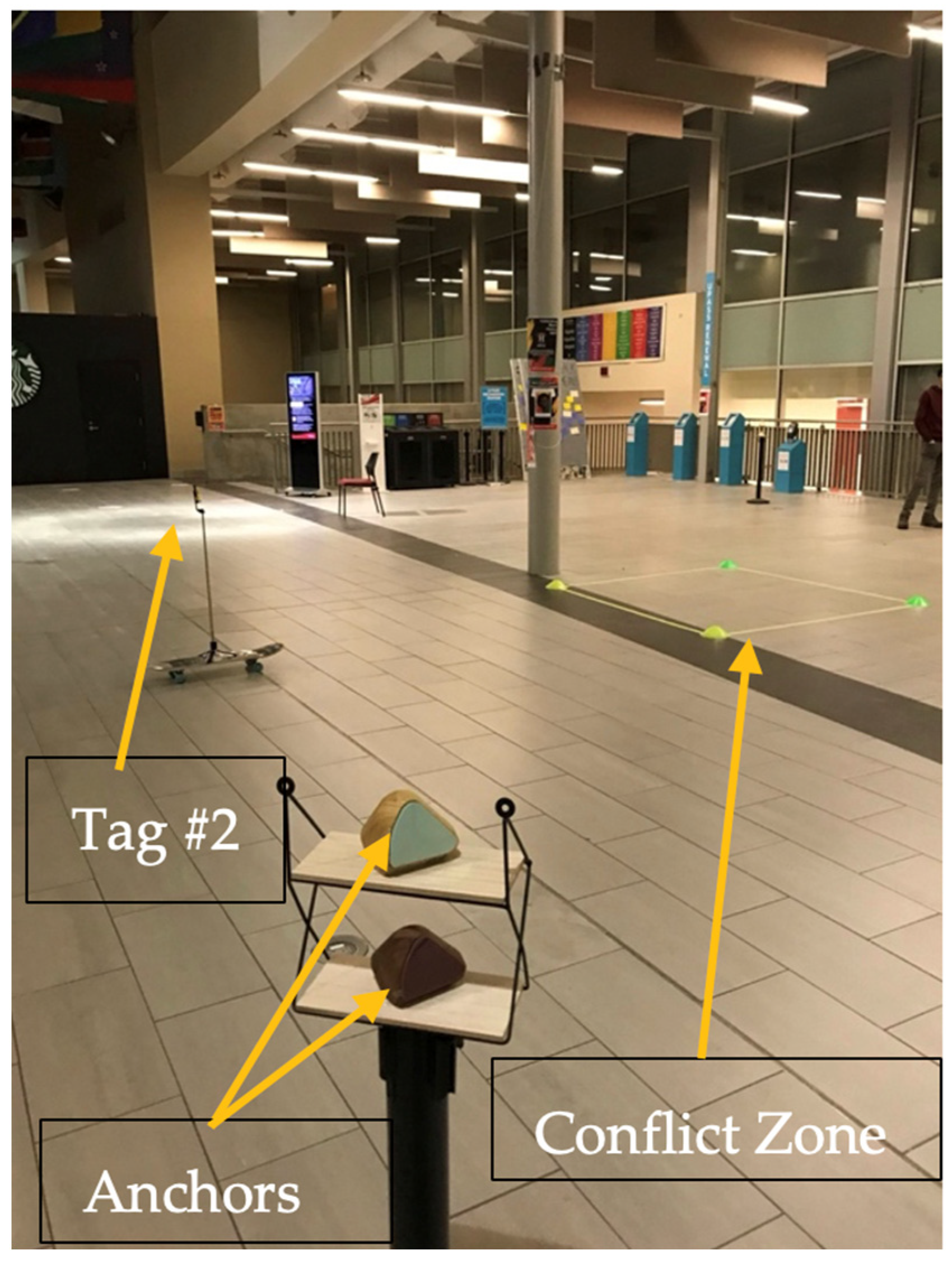

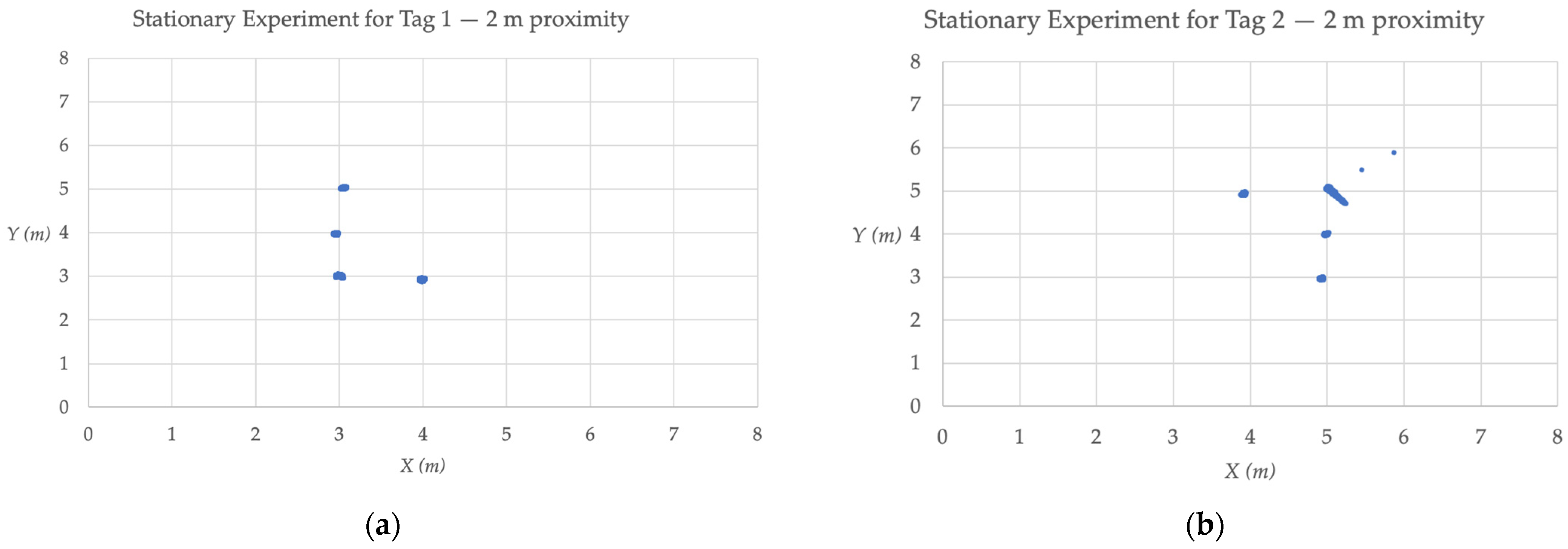

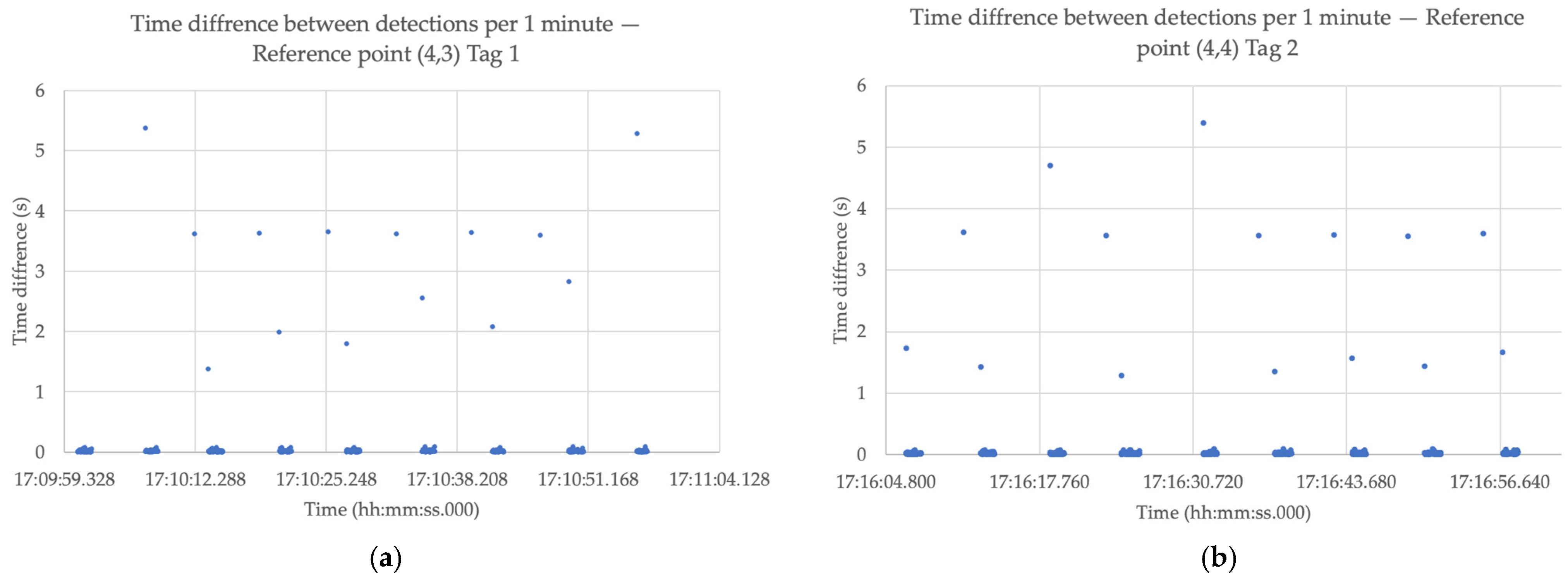

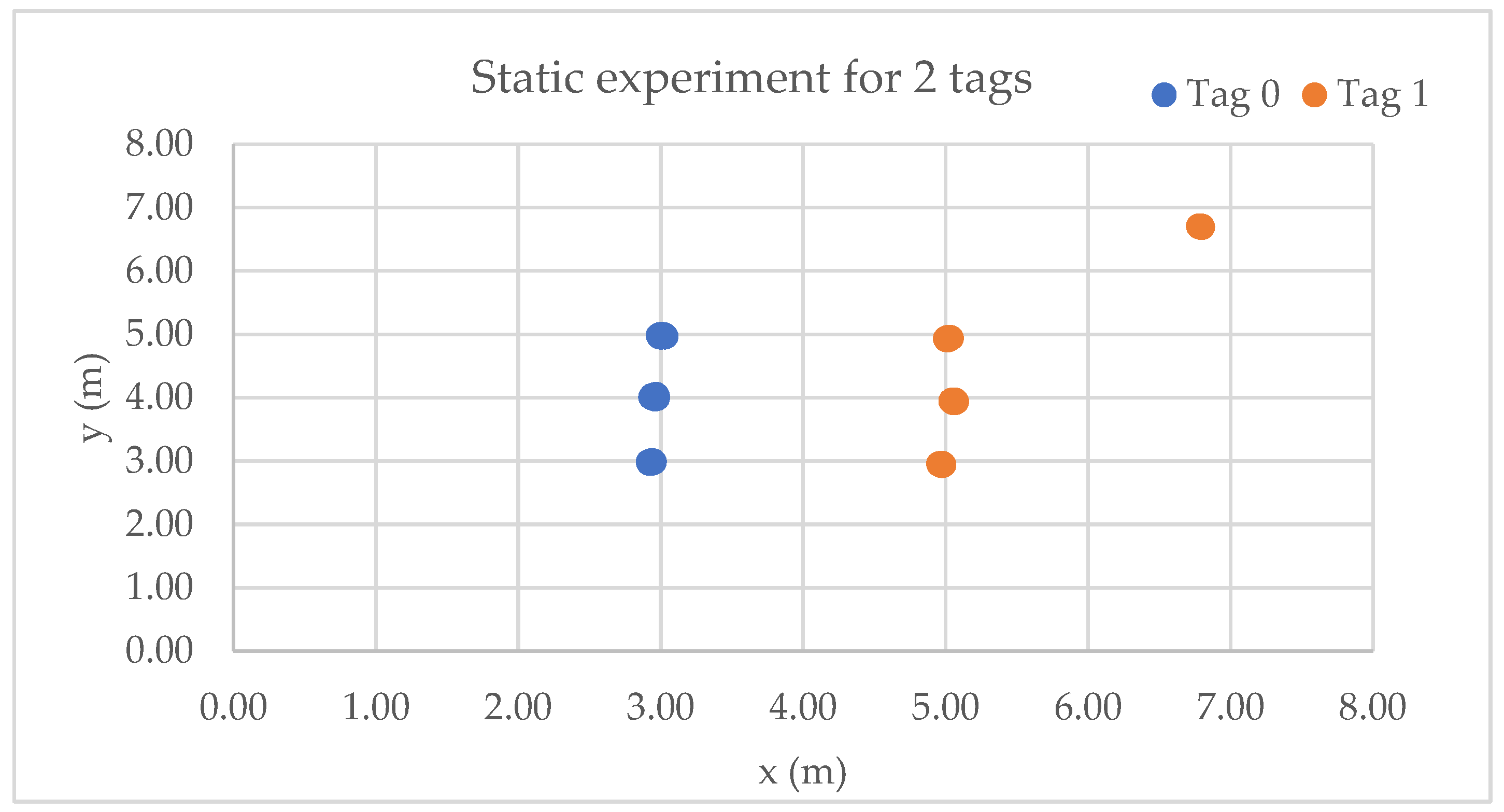

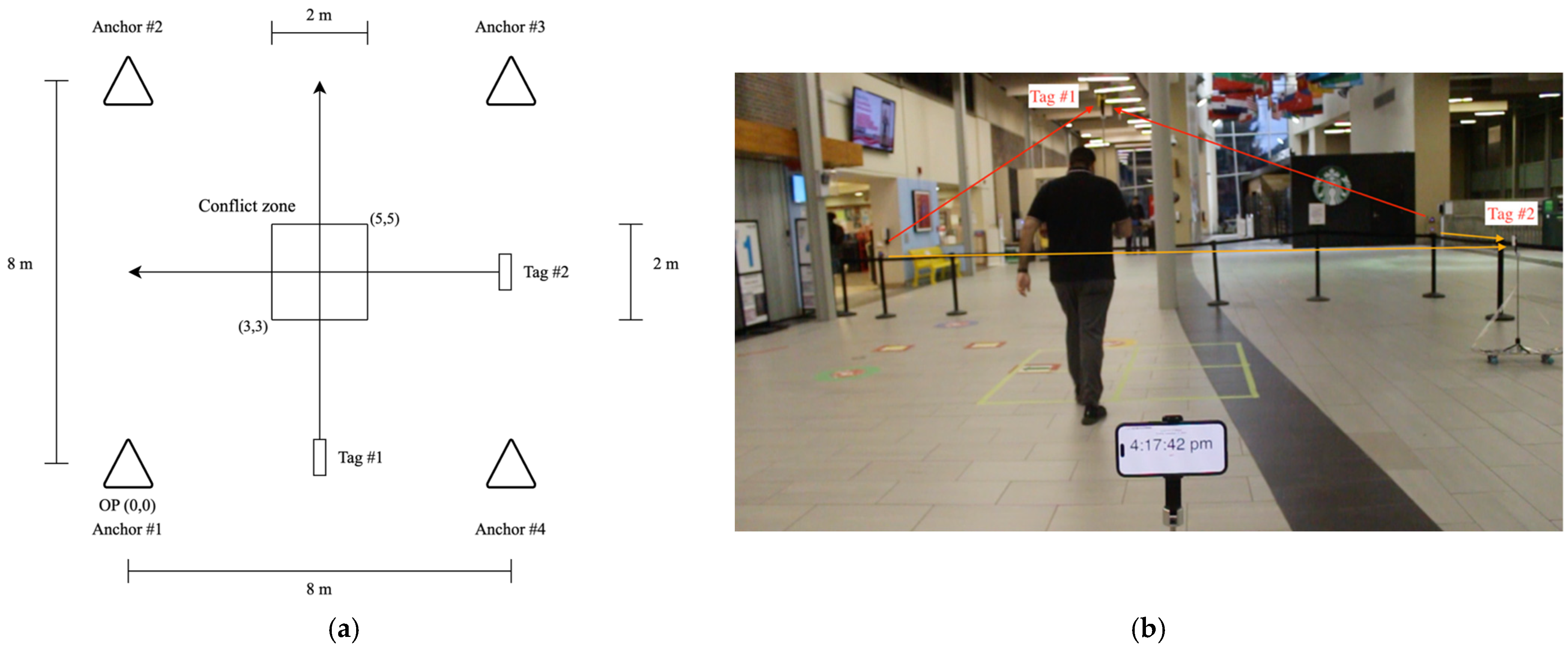

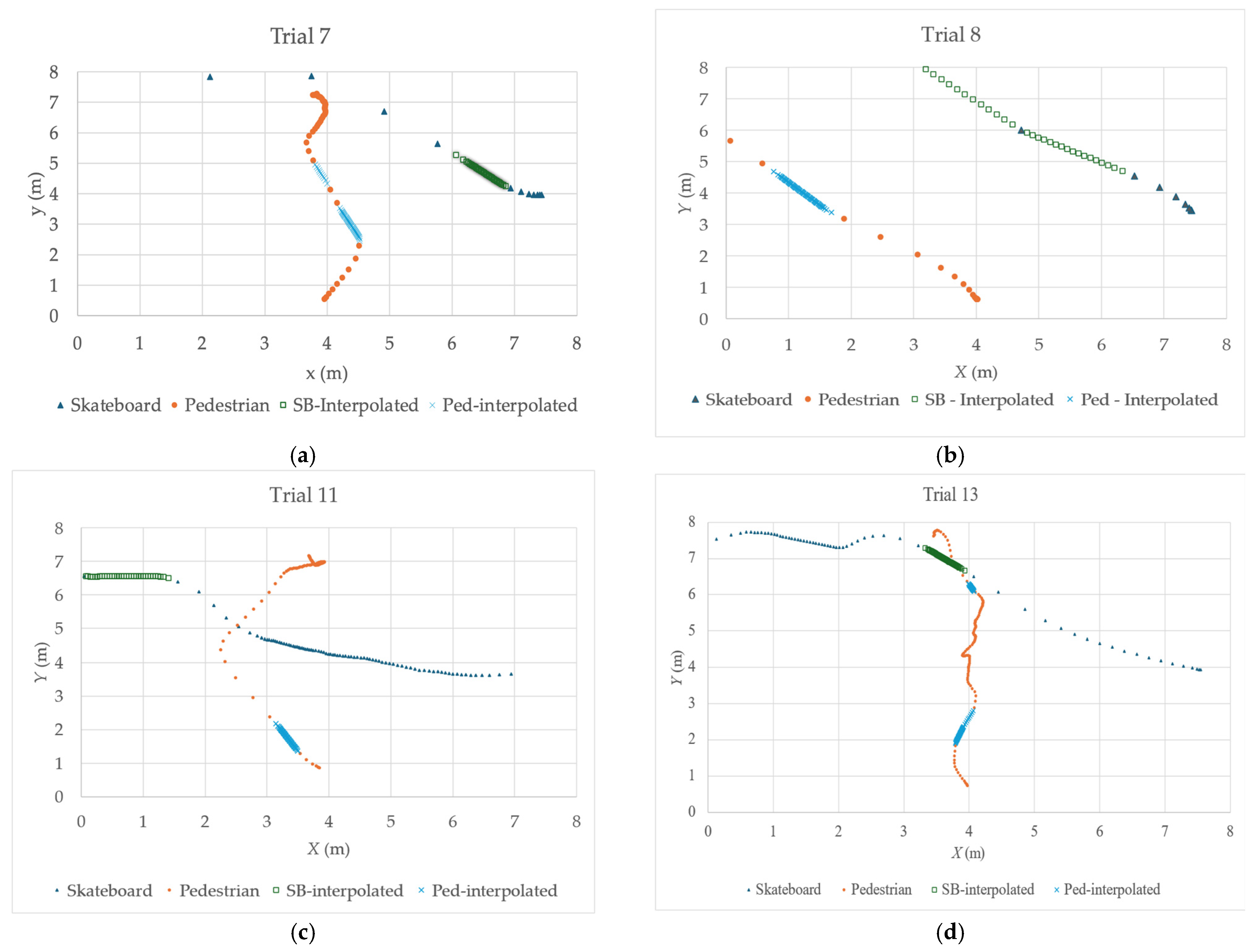

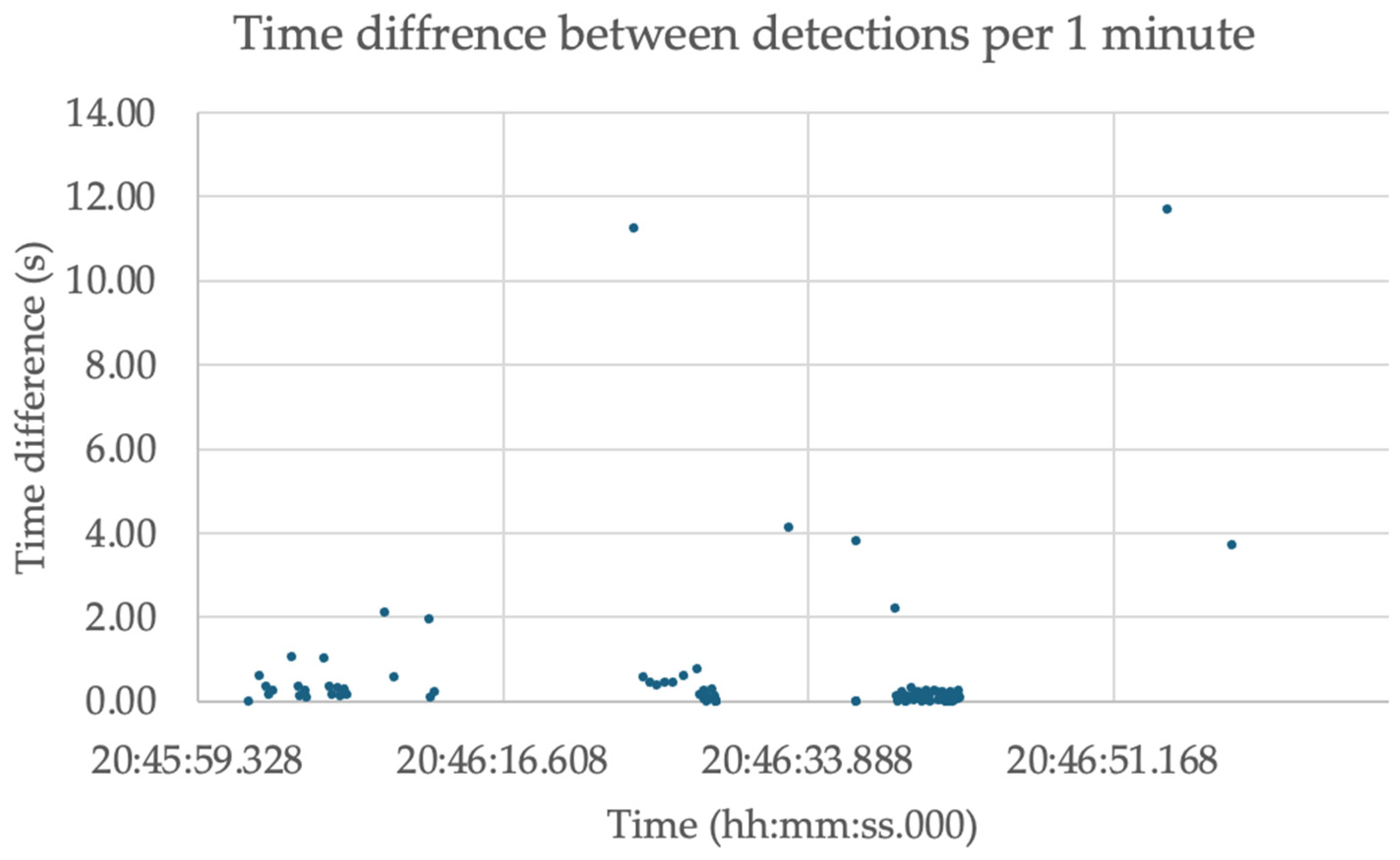

This study found that interference can affect the accuracy and latency. The results showed that UWB technology performs better in static positioning than in dynamic experiments under interference. However, across all scenarios, delays were observed due to signal interference and transmission collisions. This study found that the MAE of PET was 4.92 s between UWB-based and camera-based systems, due to multi-user interference. The results showed a pattern of an average delay of 4.5 s and 2.5 s when using two tags, but the detection rate was every 20 ms when excluding the 4.5 and 2.5 s delayed times. Moreover, when adding a third tag to broadcast the time for the master–slave technique, the results showed an increase in missed detections, with time gaps reaching almost 12 s, and a detection rate of 600 ms.

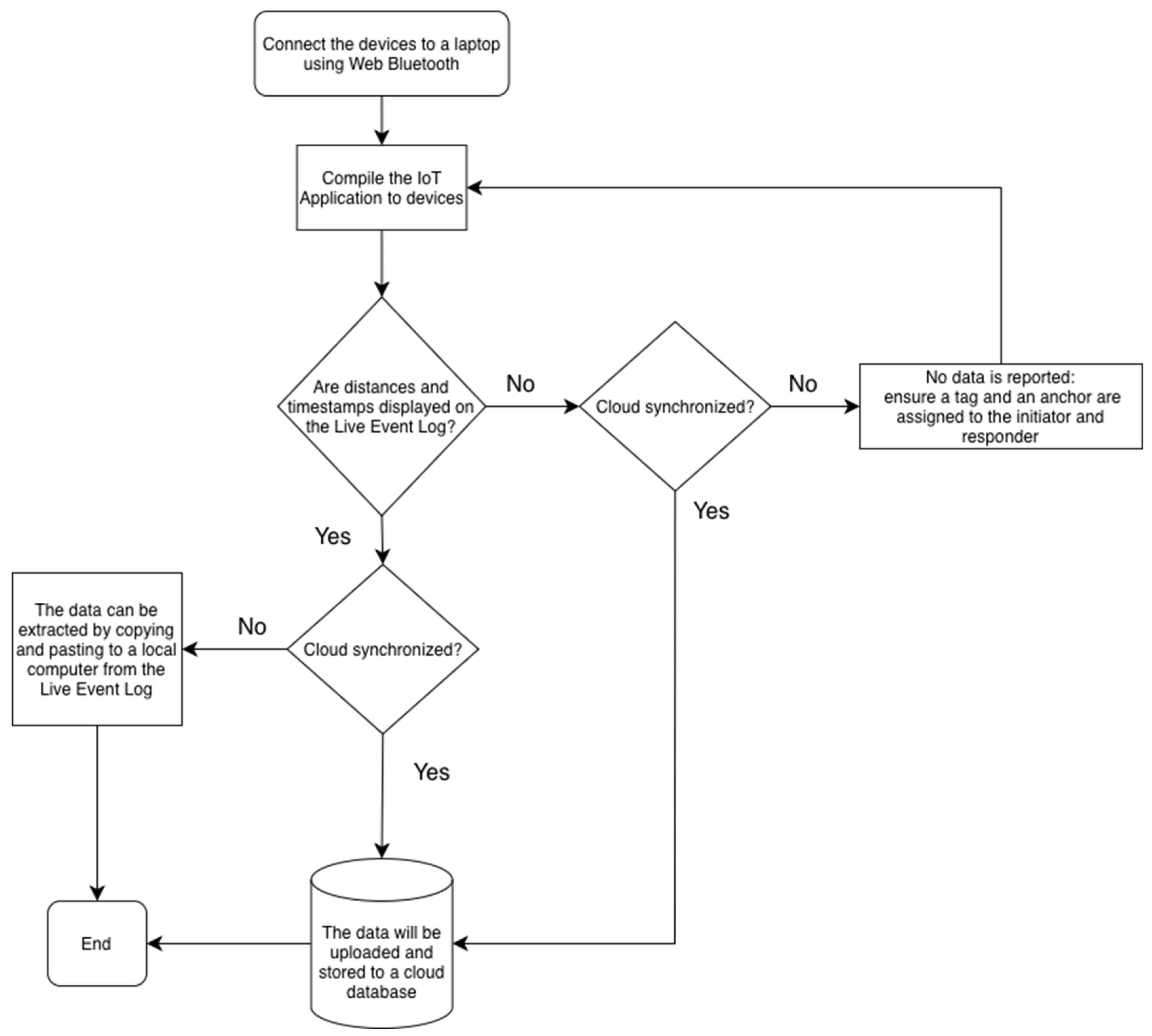

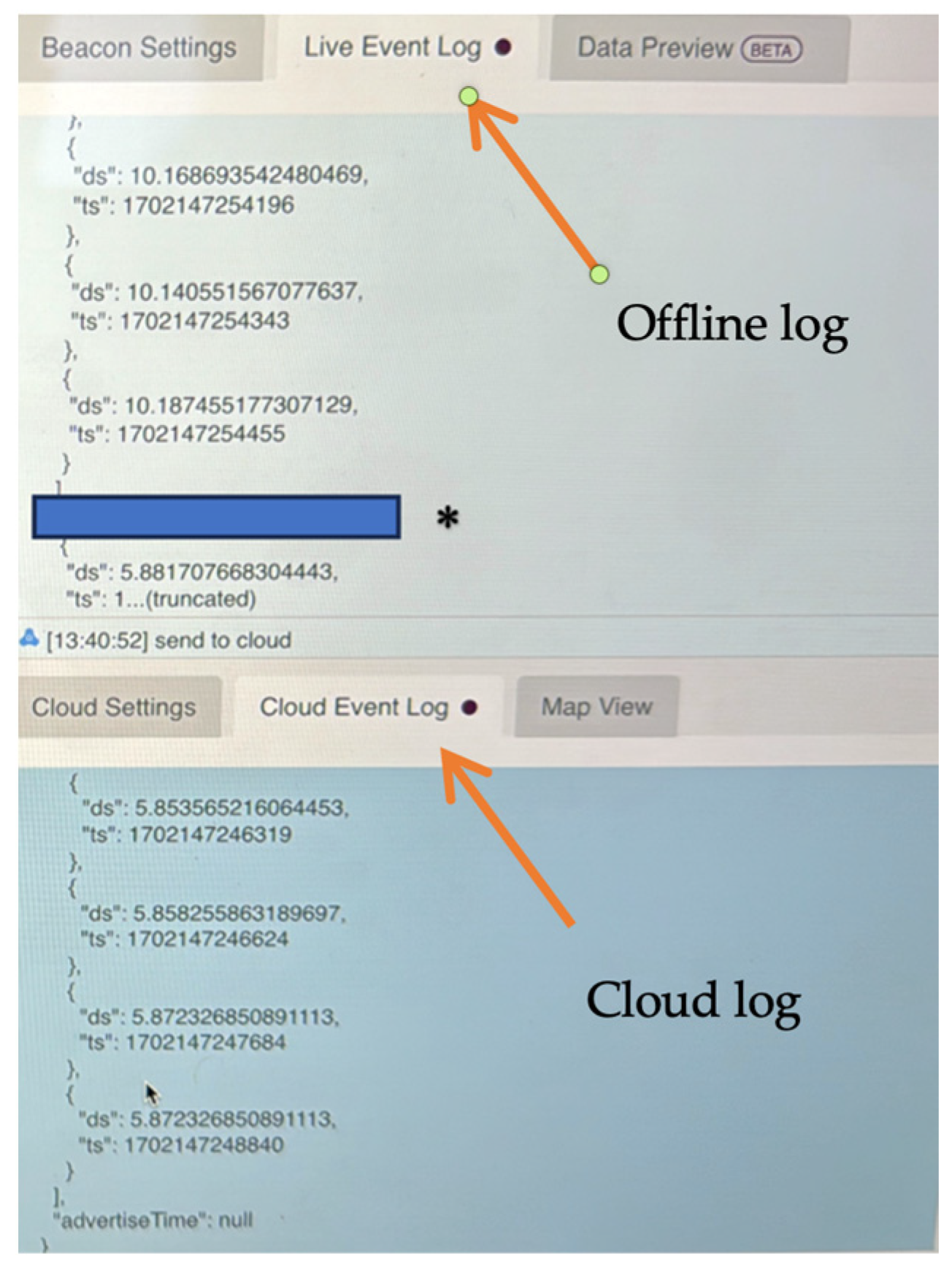

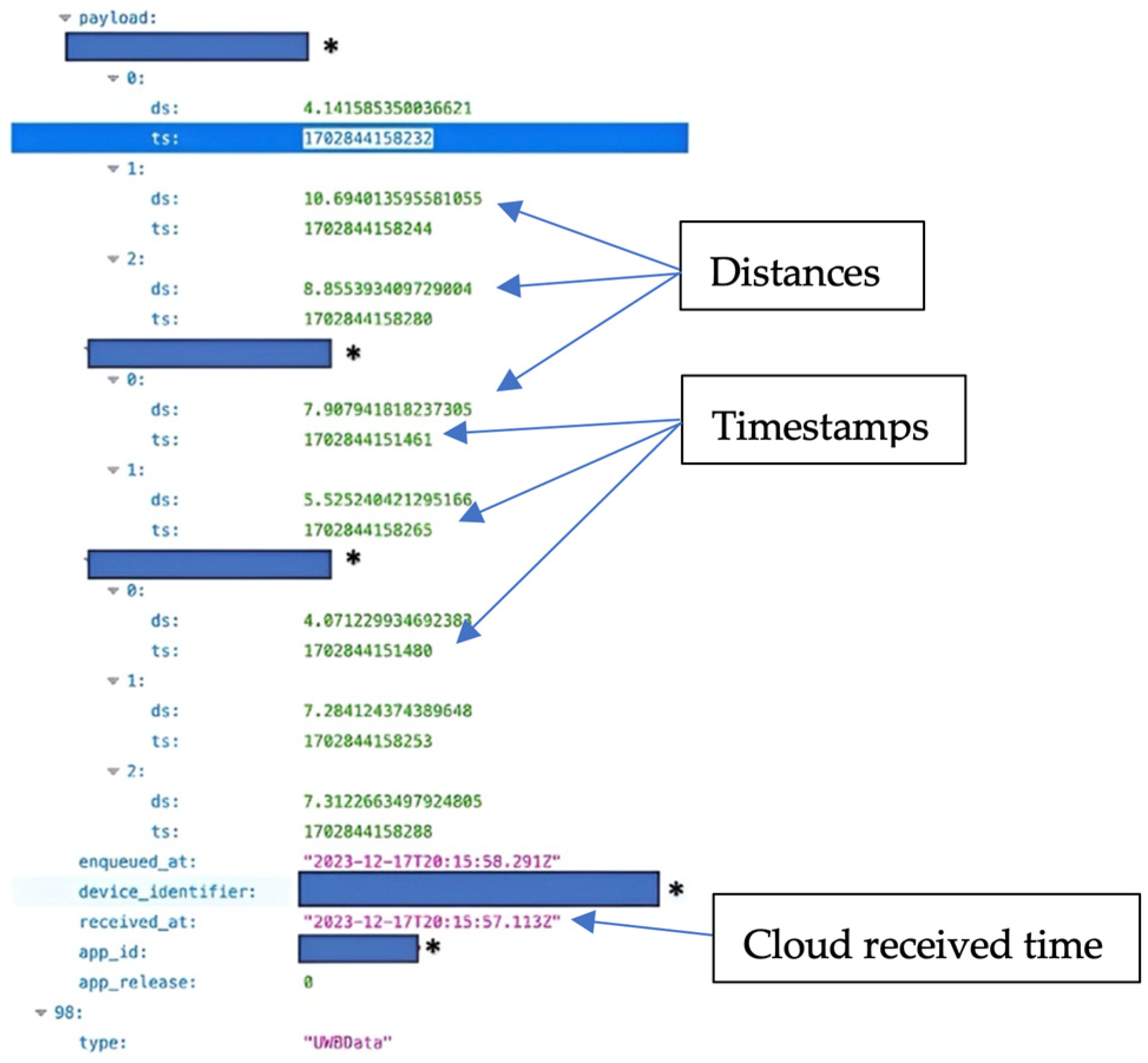

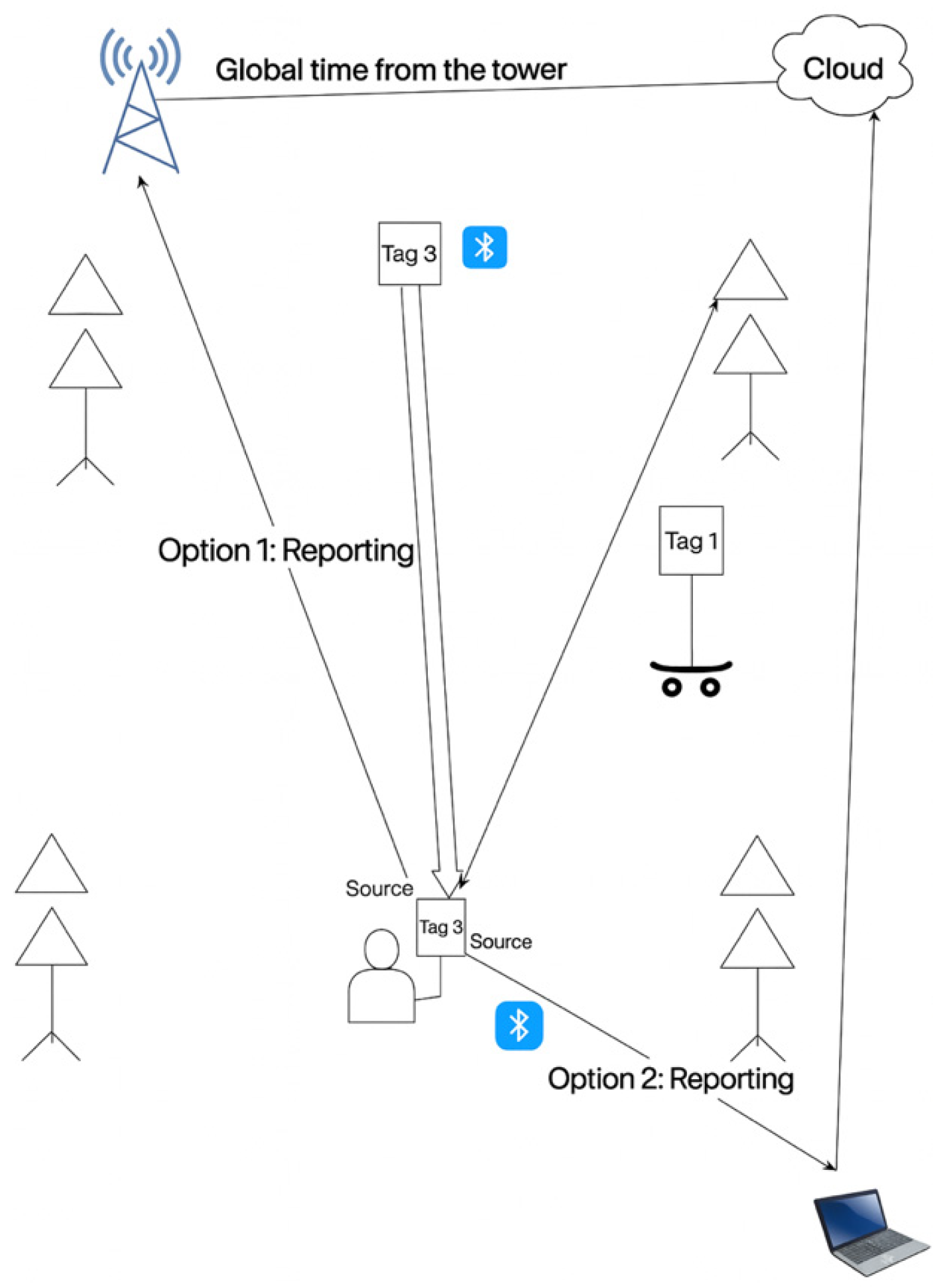

The study uploaded eight batches of detections to avoid data loss. However, signal interference caused delays in the detections, resulting in delays when the cloud received the eight batches. For instance, the delays occurred between the eight batches, resulting in delays in the time to the cloud. The challenge in this study is not only the range error but also synchronization when relying on the cloud’s global time. In later experiments, the study stored the data offline on a laptop and used the laptop’s global time as a common clock. This showed a suitable method to have synchronized detections.

In the master–slave synchronization technique, the tags’ latency increased, leading to longer time delays between detections. This is because the tags’ CPUs could not handle many tasks, such as scanning the time from the master tag, range, and uploading to the cloud. Fernando et al. [

56] proposed a framework, Edge-Fog-Cloud, that achieved up to 7.5-times lower latency and 80% battery savings. This approach can help process more data without overwhelming the tag’s CPU. For instance, at the edge layer, UWB devices communicate, collect raw data, and store it at a local gateway, such as a laptop. Then, the gateway attaches a timestamp to each detection. Fog focuses on cleaning up the extensive messages and deciding which important messages need to be uploaded to the system, such as PET values. Finally, the Cloud layer is for long-term storage, which focuses on safety data, not raw data.

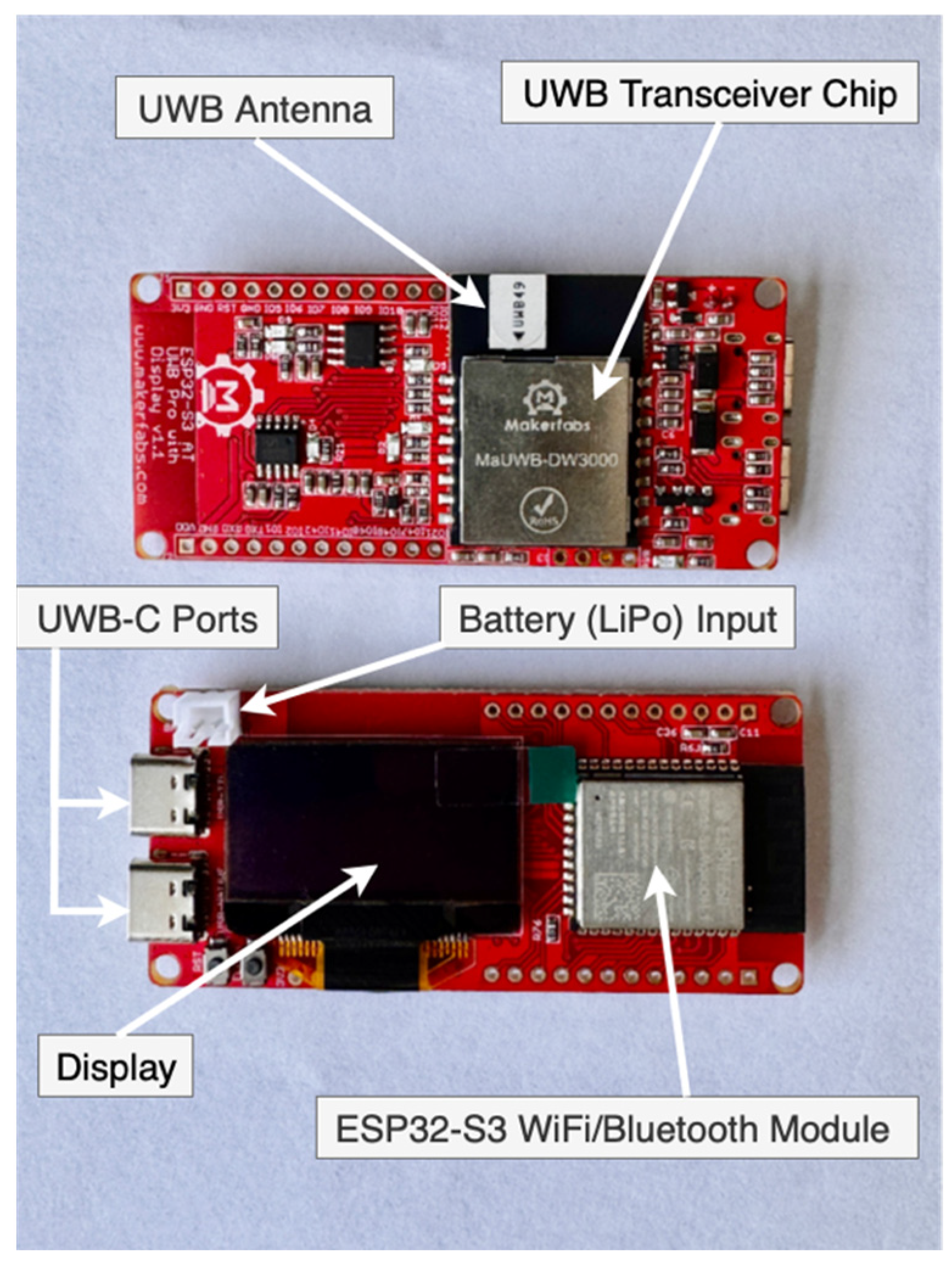

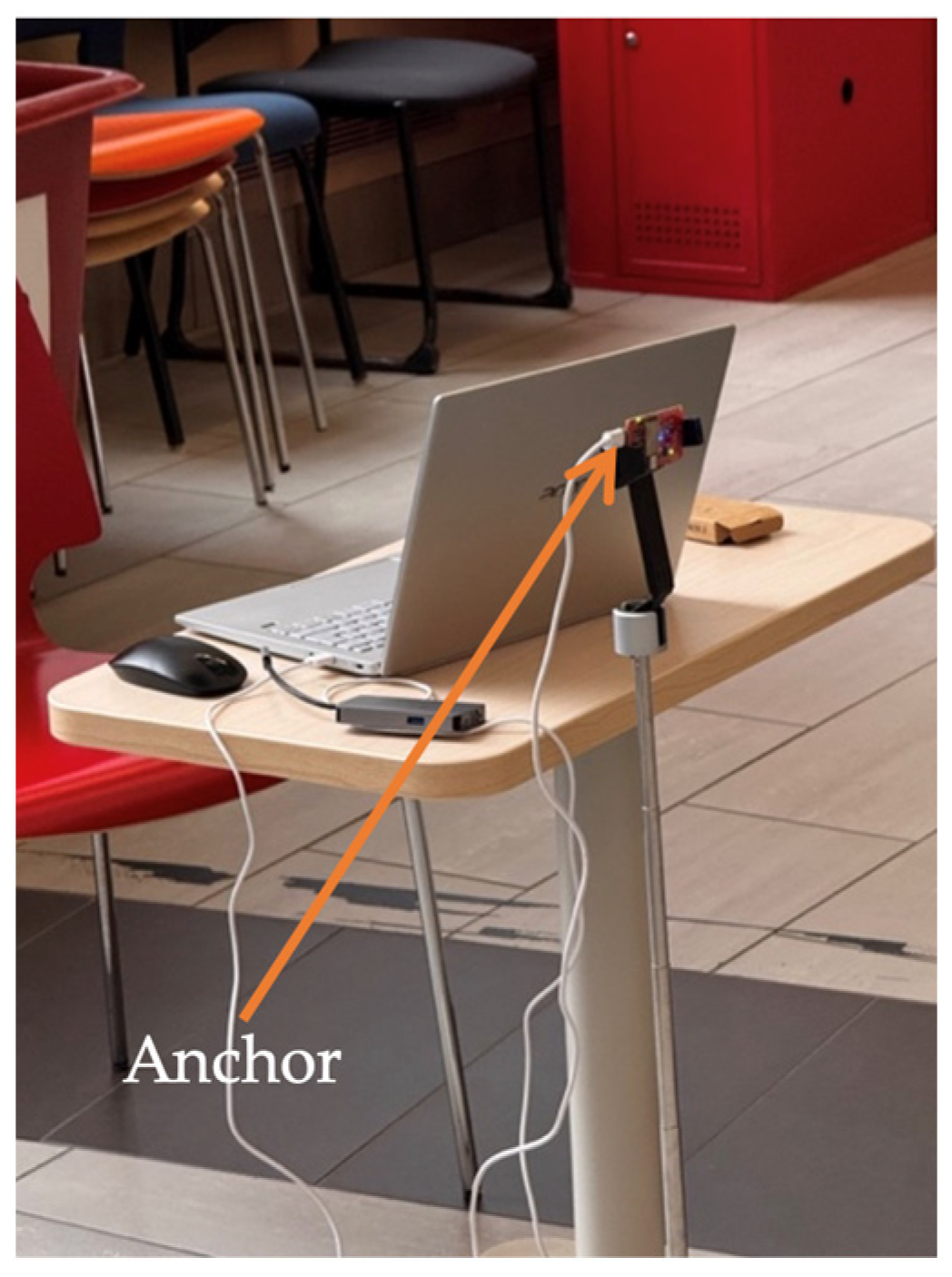

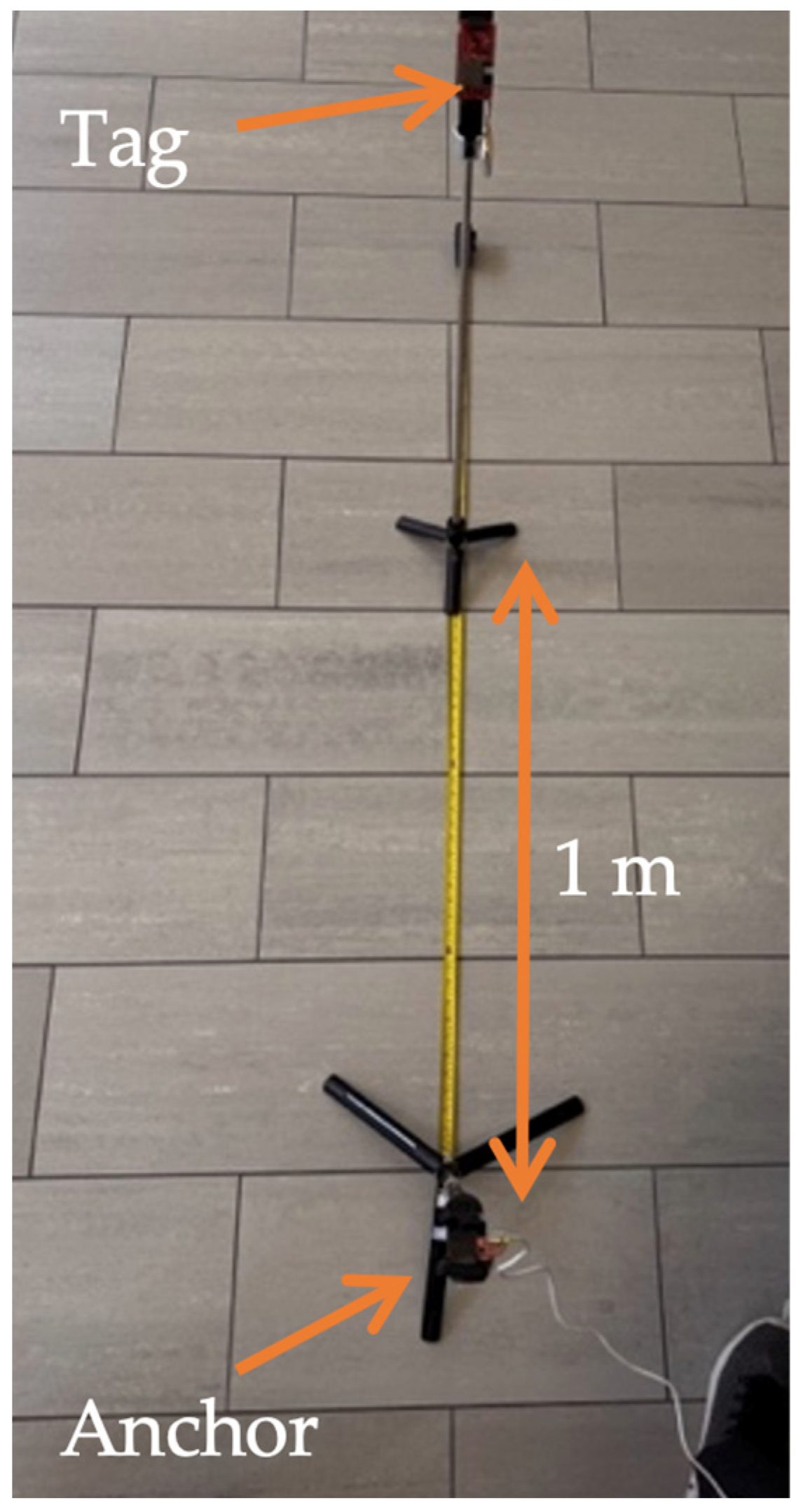

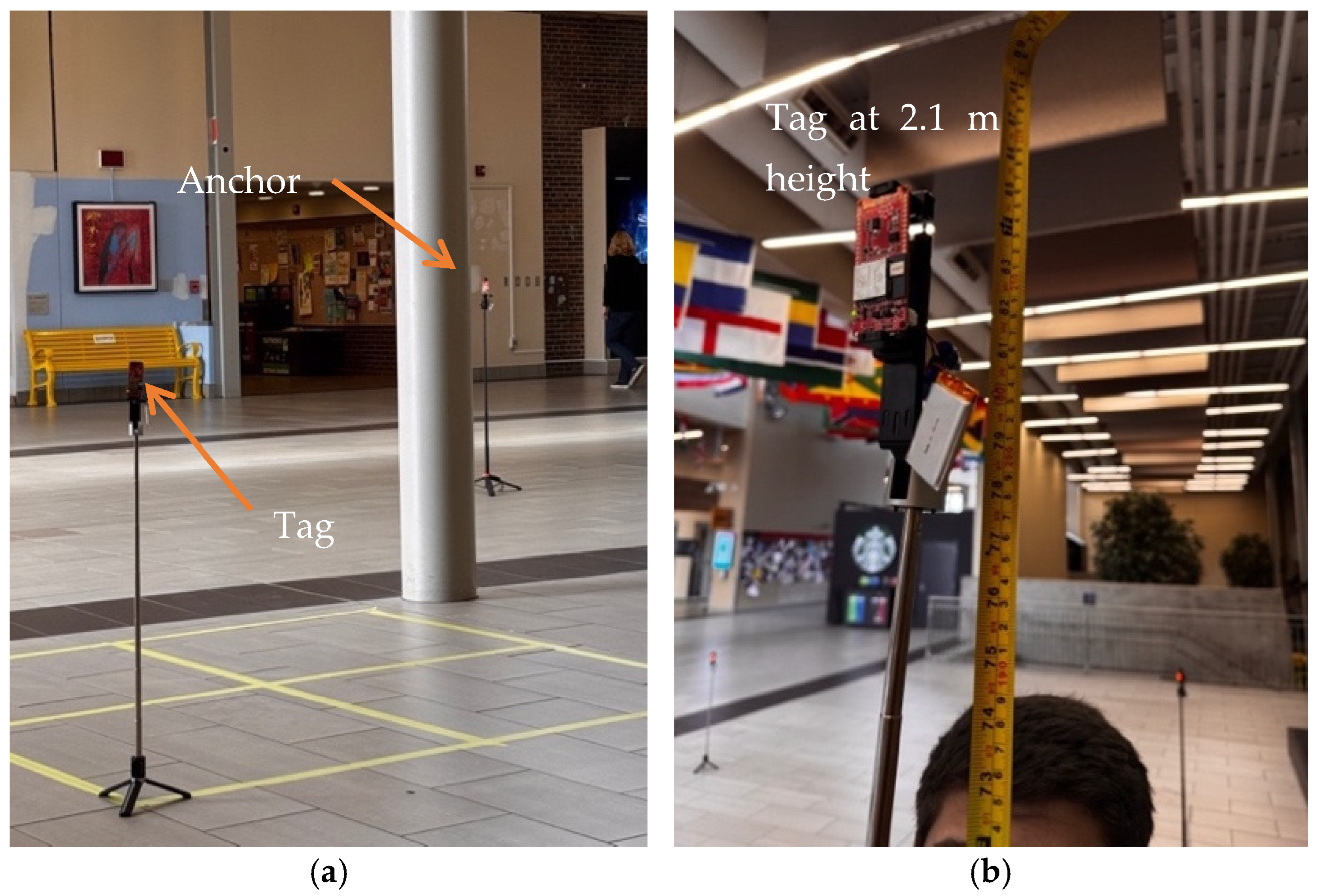

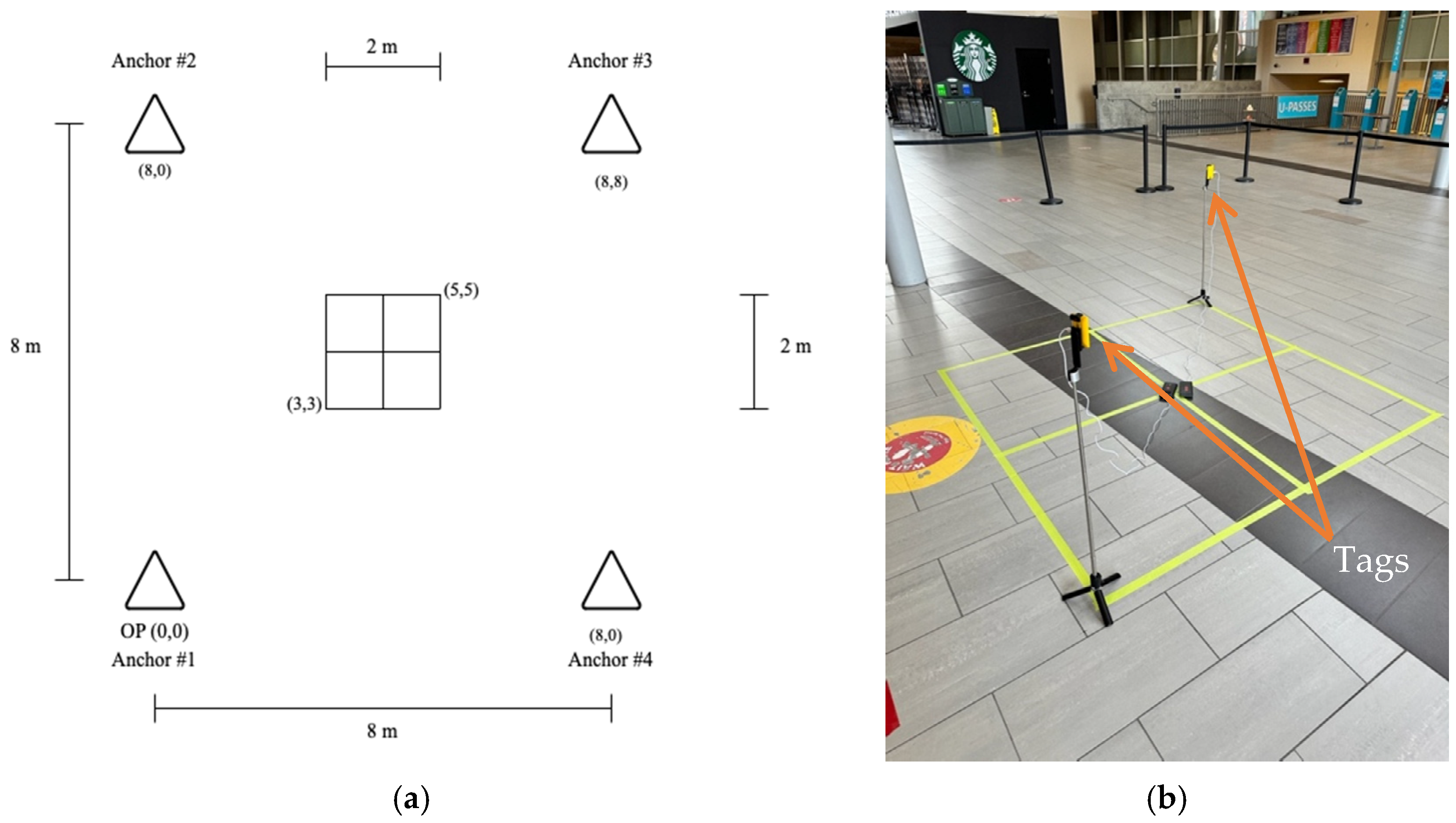

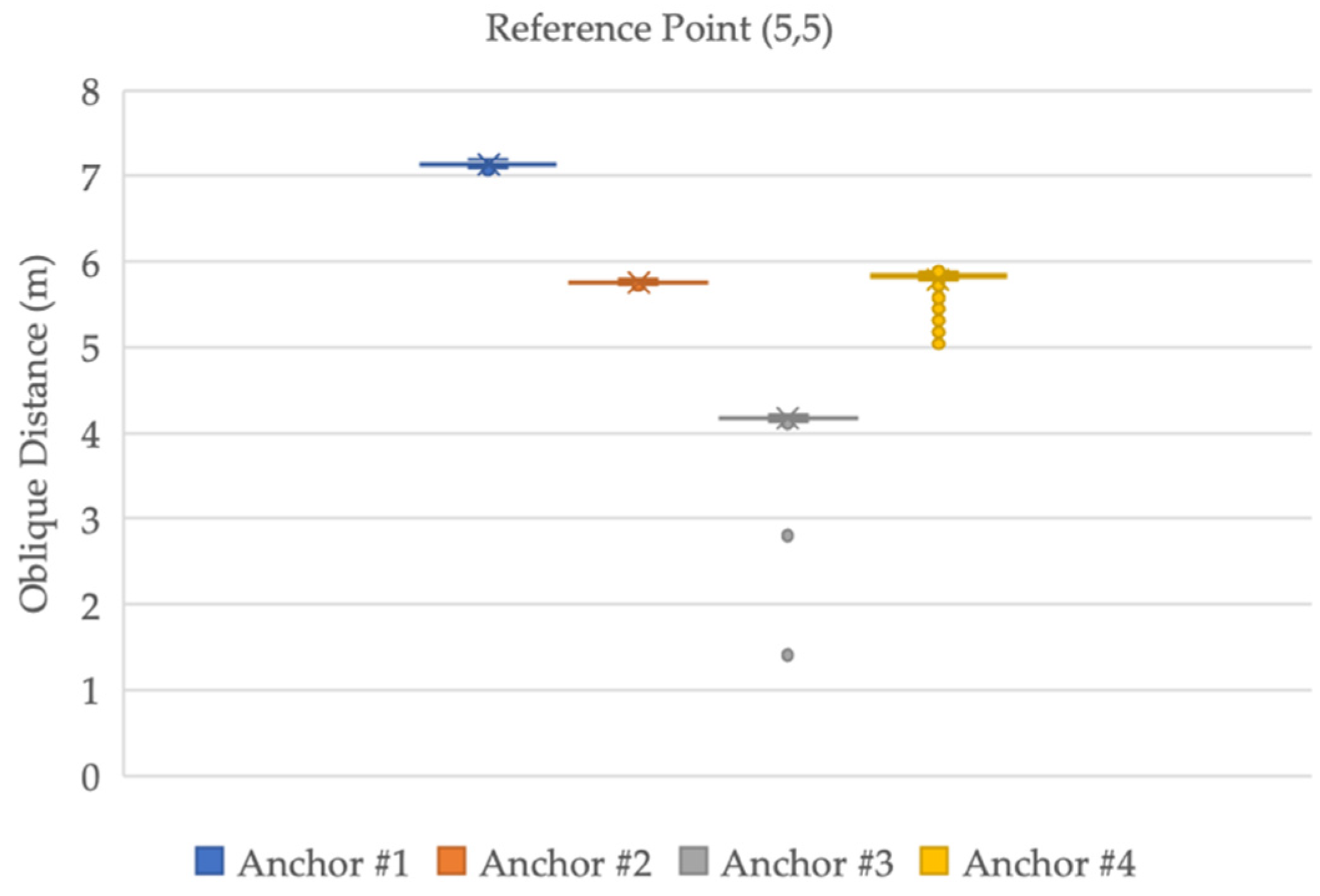

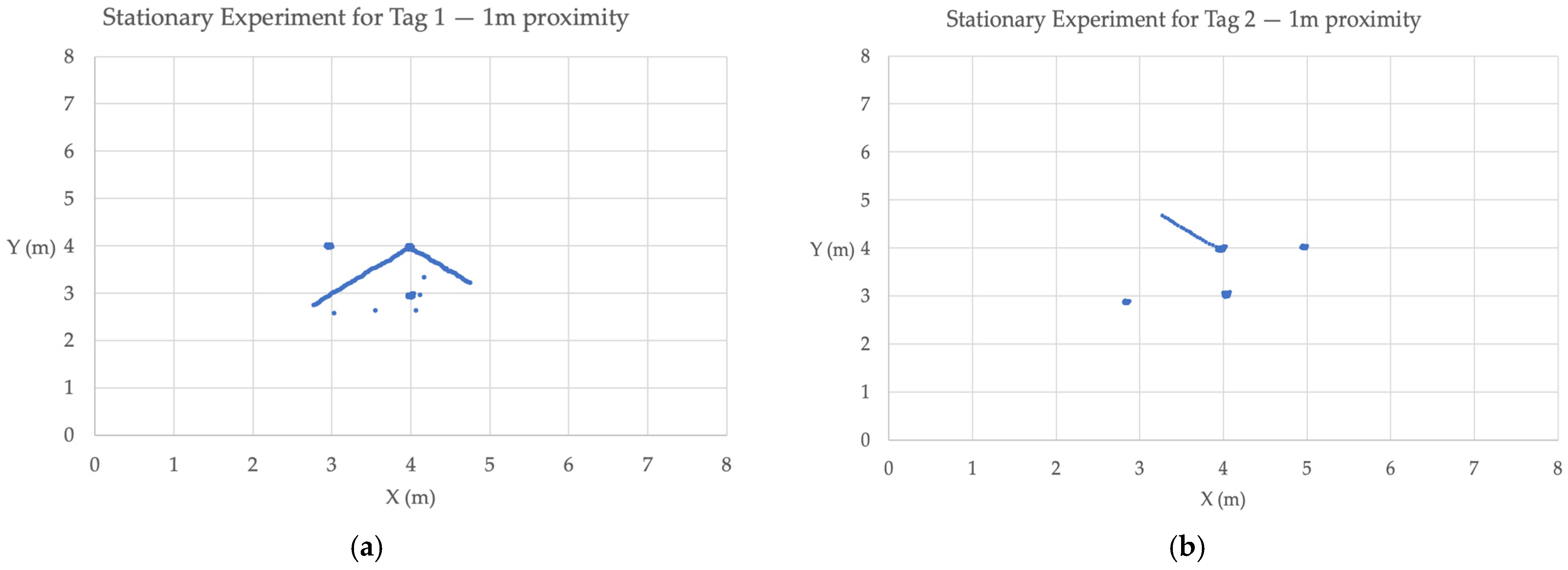

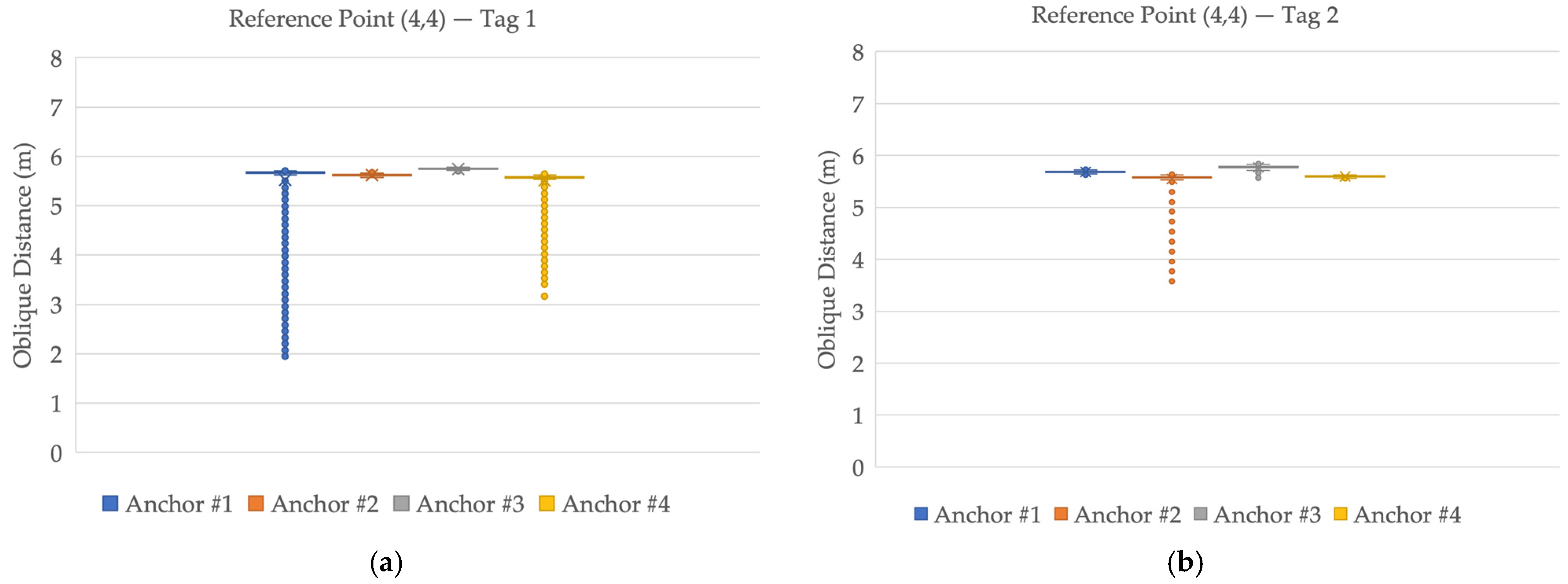

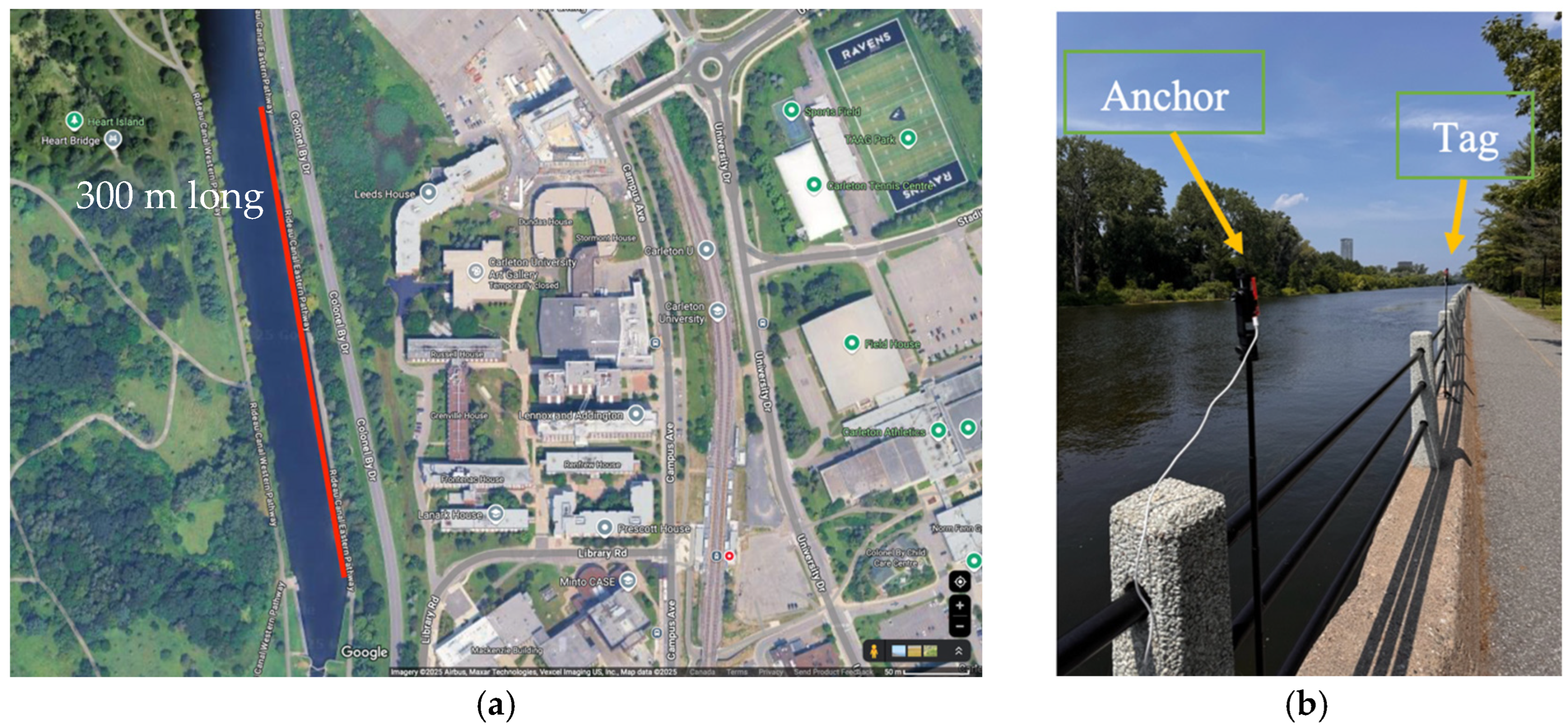

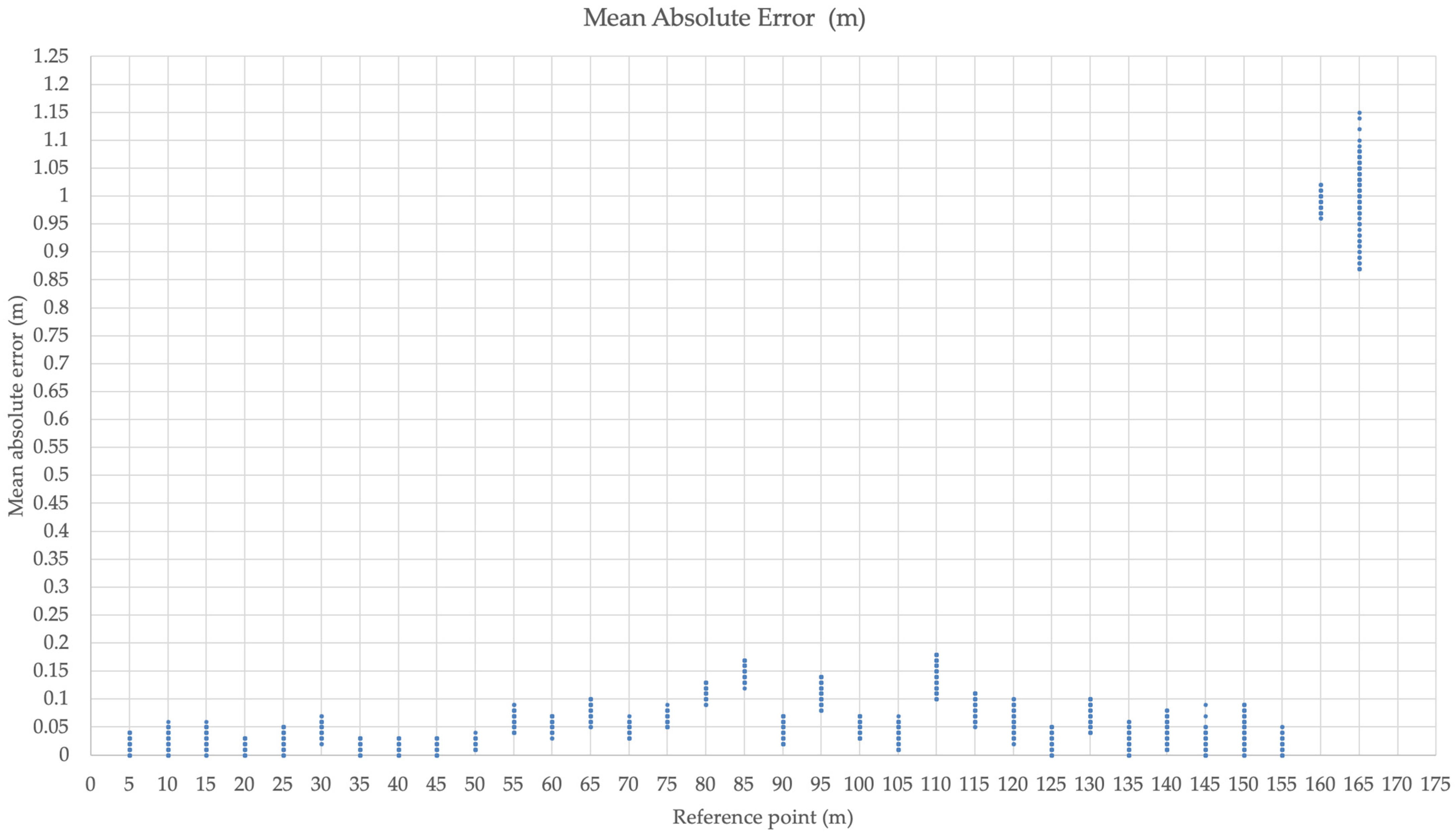

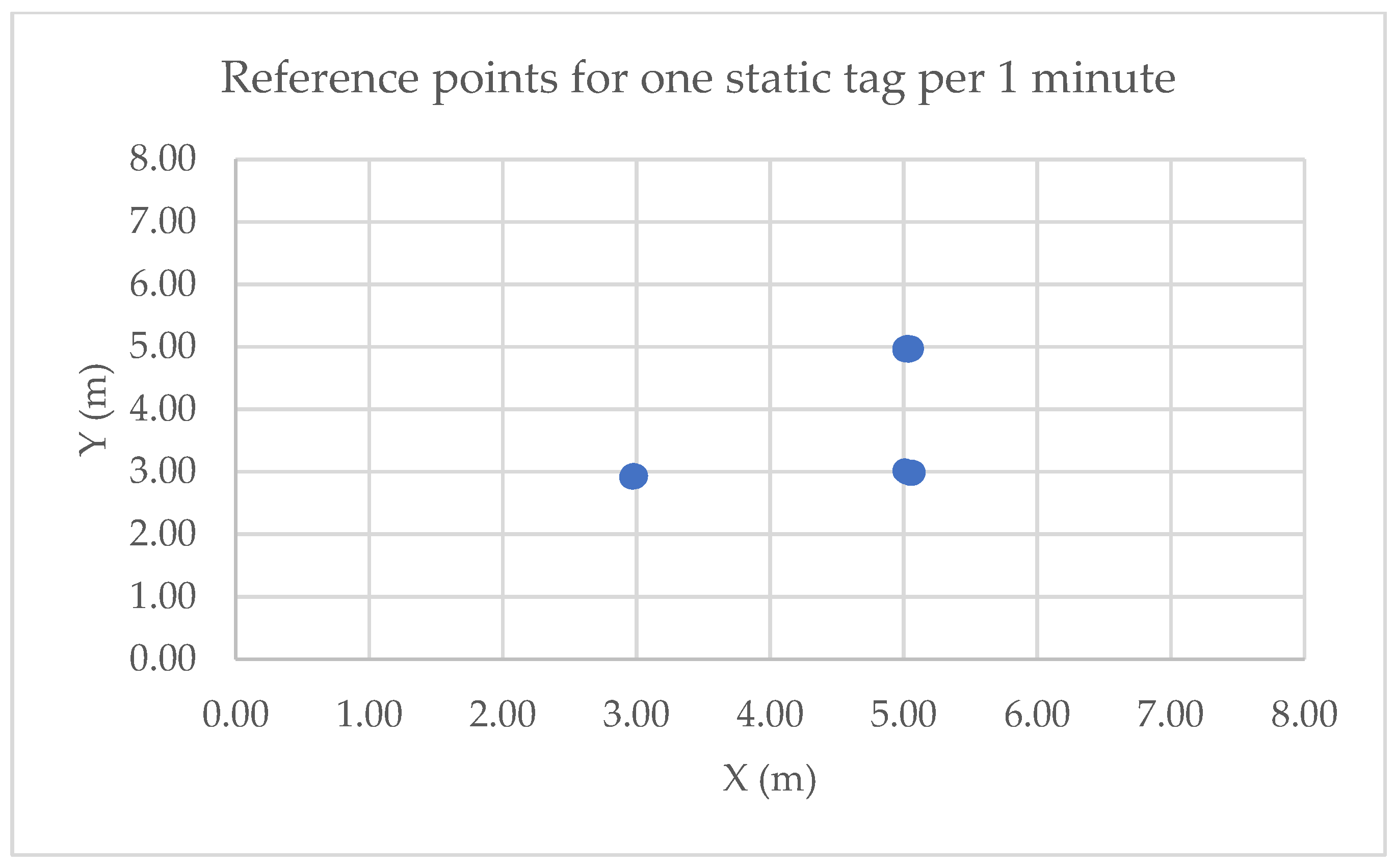

To address signal interference that causes unreliable positioning, an open-hardware UWB system was used to adjust the UWB parameters. After using the open hardware ESP32s3 UWB modules, the study found the need for antenna calibration to achieve a +/− 4 cm error in ranging accuracy. This was accomplished by placing an anchor and a tag at 1 and 2 m and comparing the UWB measurements with the actual distance. Furthermore, the study explored the maximum range between devices in an outdoor environment. The study found that at 1.7 m, the maximum range occurred at a 165 m reference point. Moreover, the detection rate started to reduce at the 145 m reference point. The minimum detection rate was achieved at the reference point at 160 m, with a detection every 463 ms. However, at the 165 m reference point, the detection rate increased to 120 ms. Although the devices stopped ranging beyond 165 m, the author increased the heights of the tag and anchor to 2.7 m, resulting in continuous ranging up to 300 m. Therefore, this opens up a direction for future work to study the ground effect in ranging.

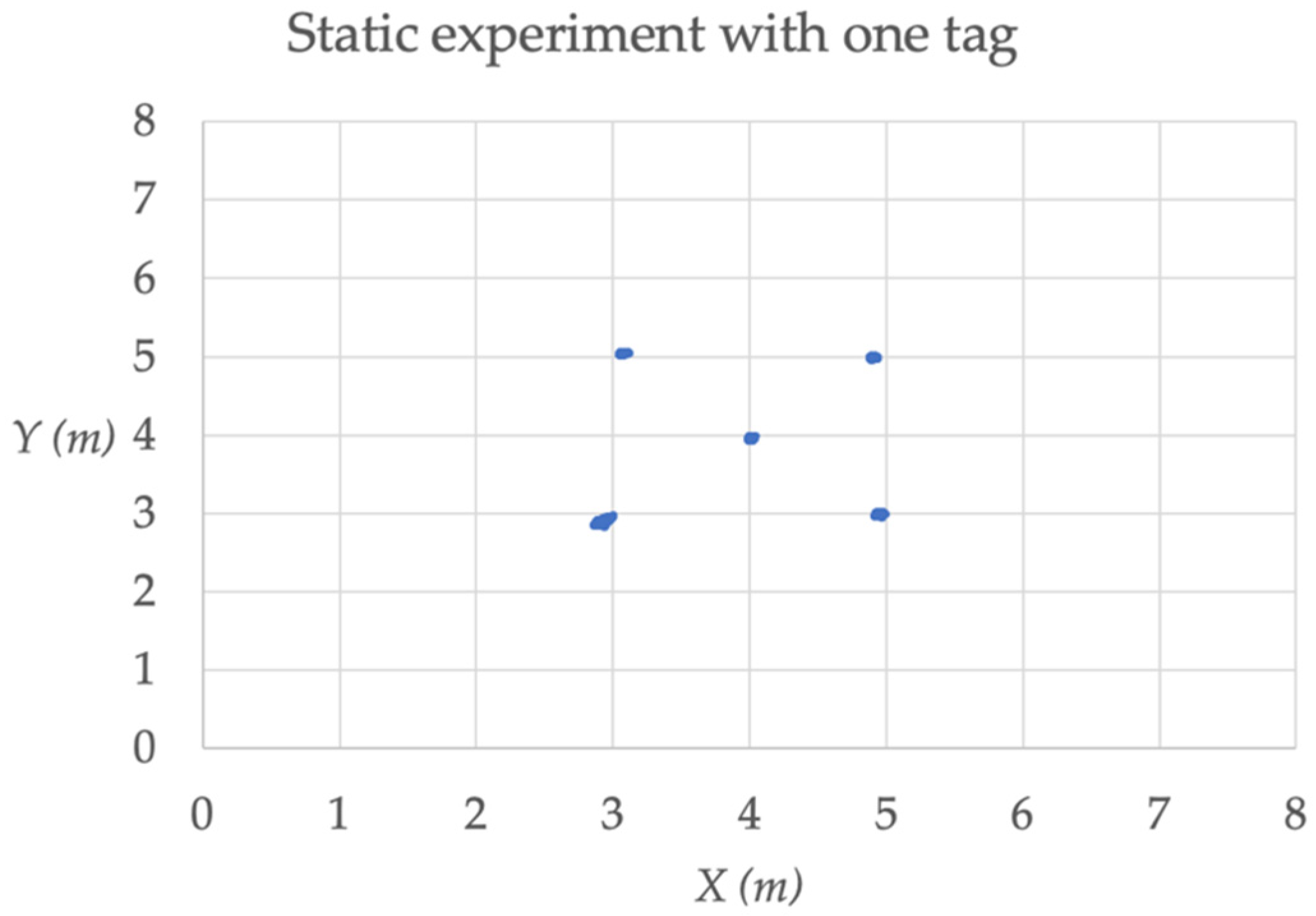

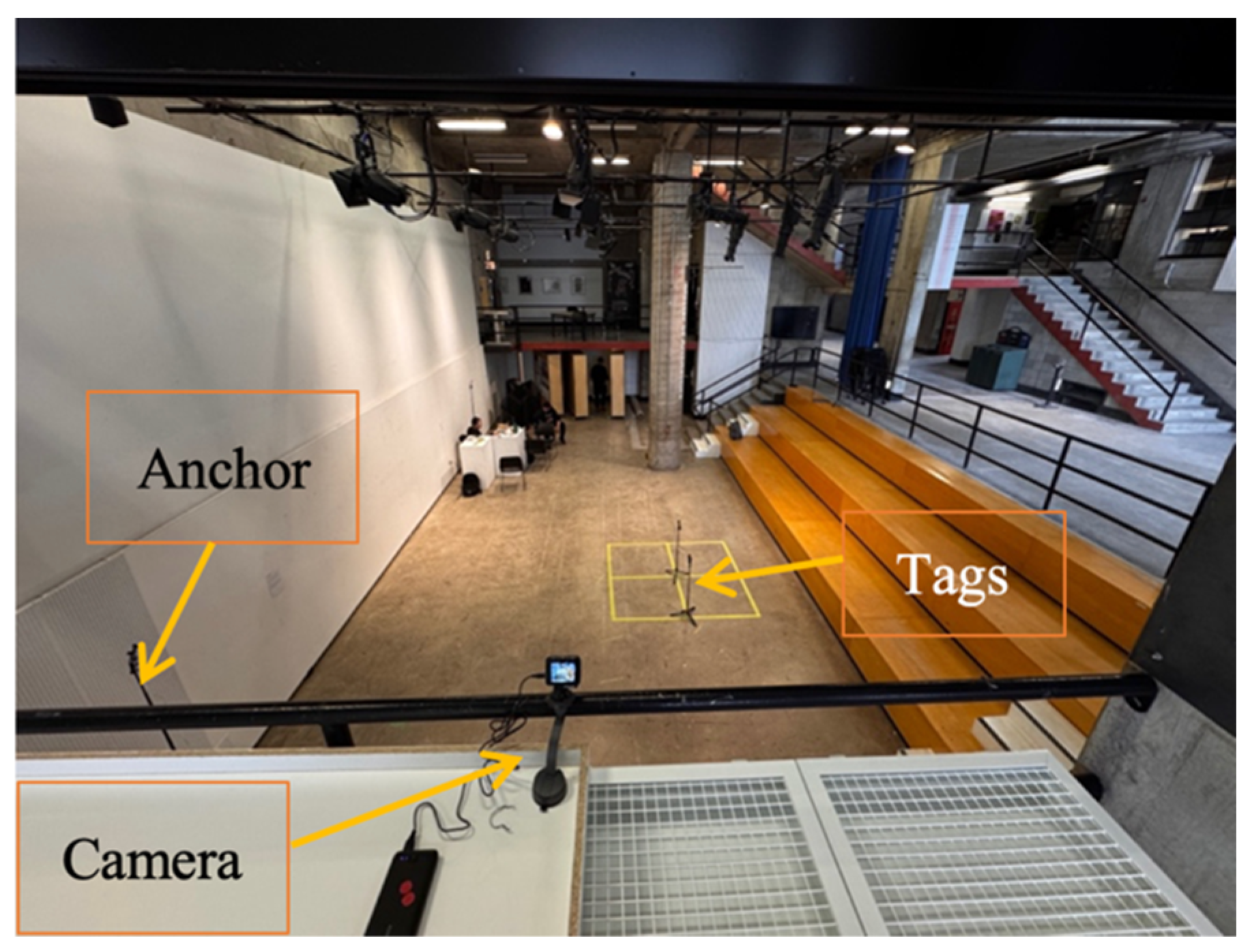

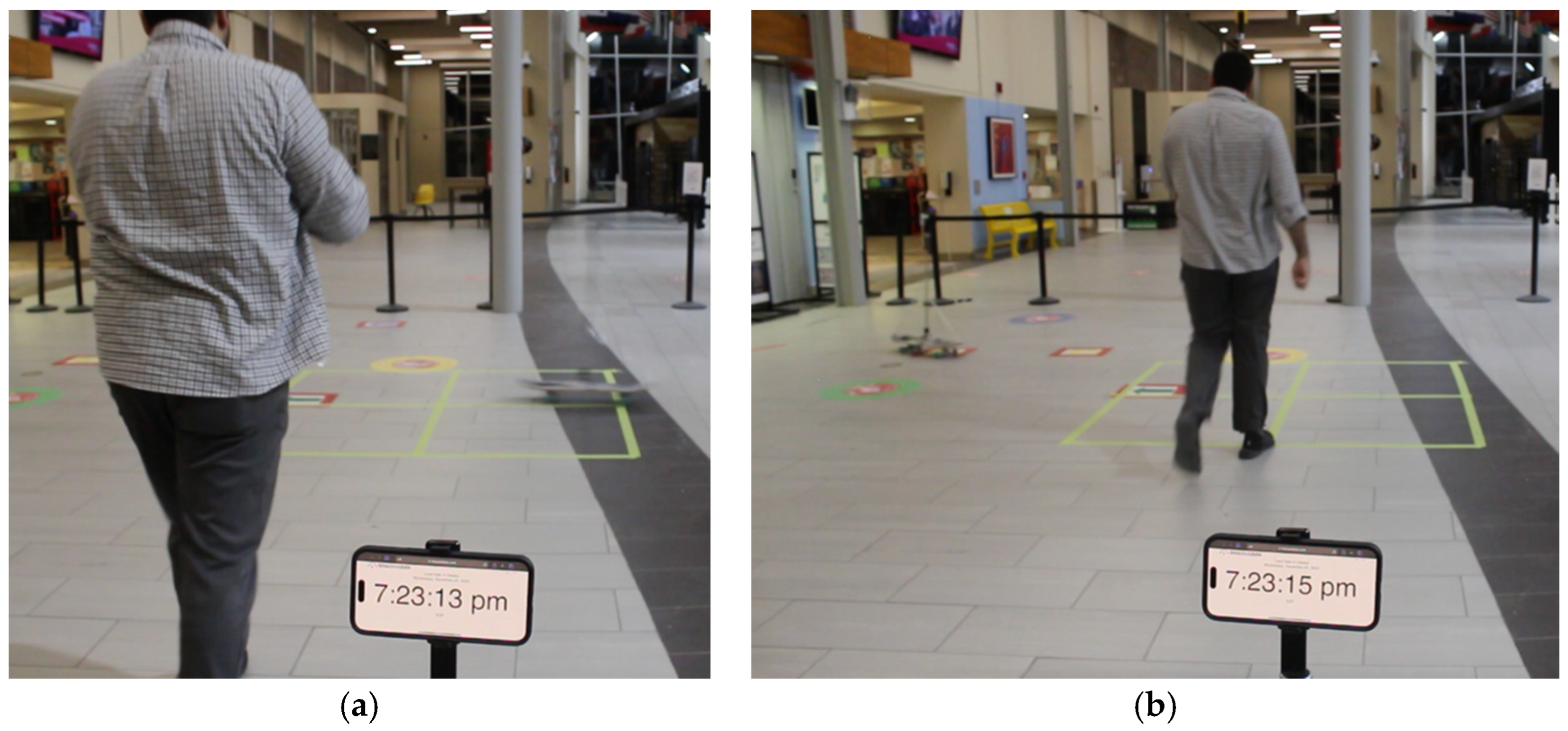

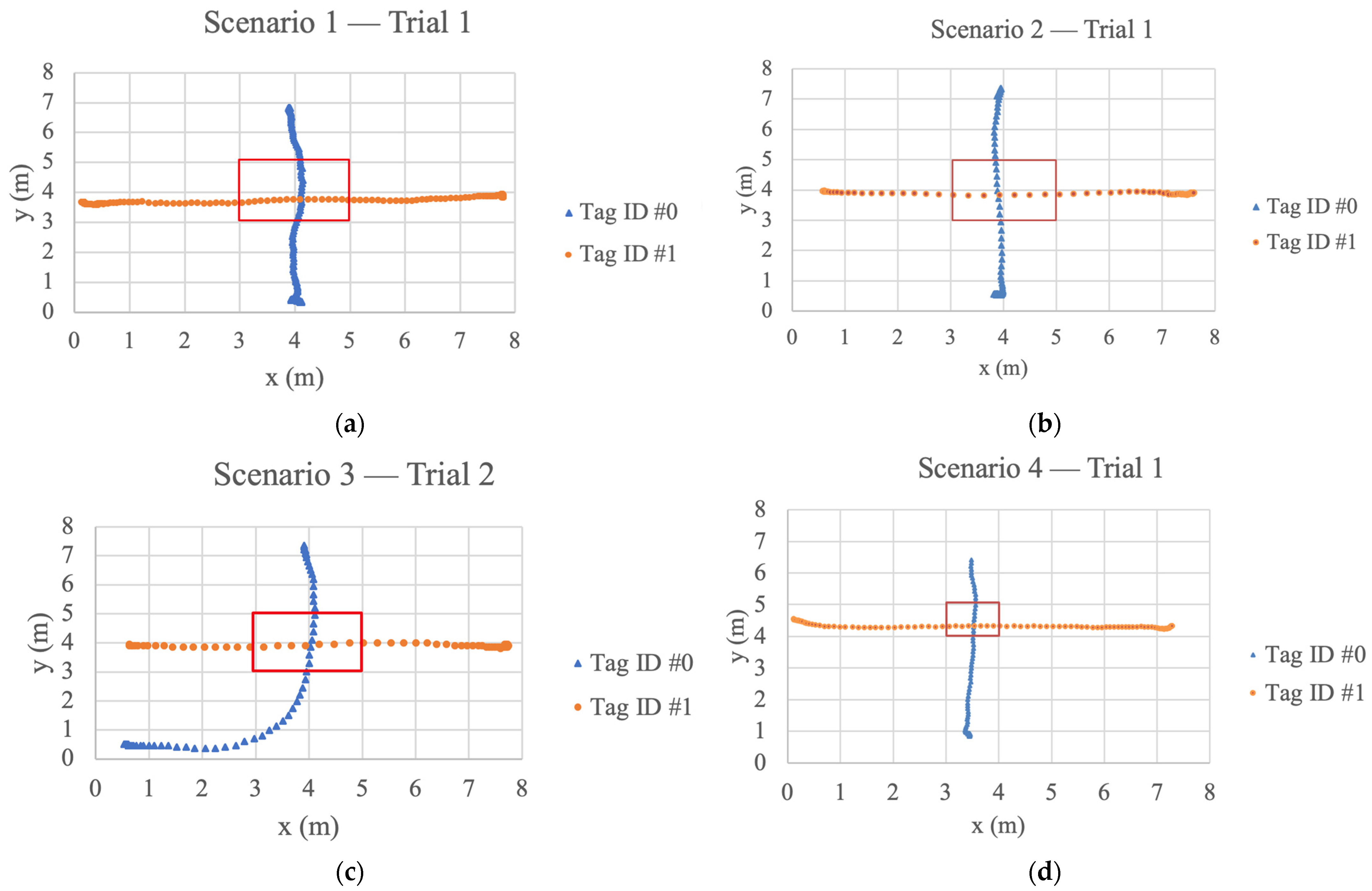

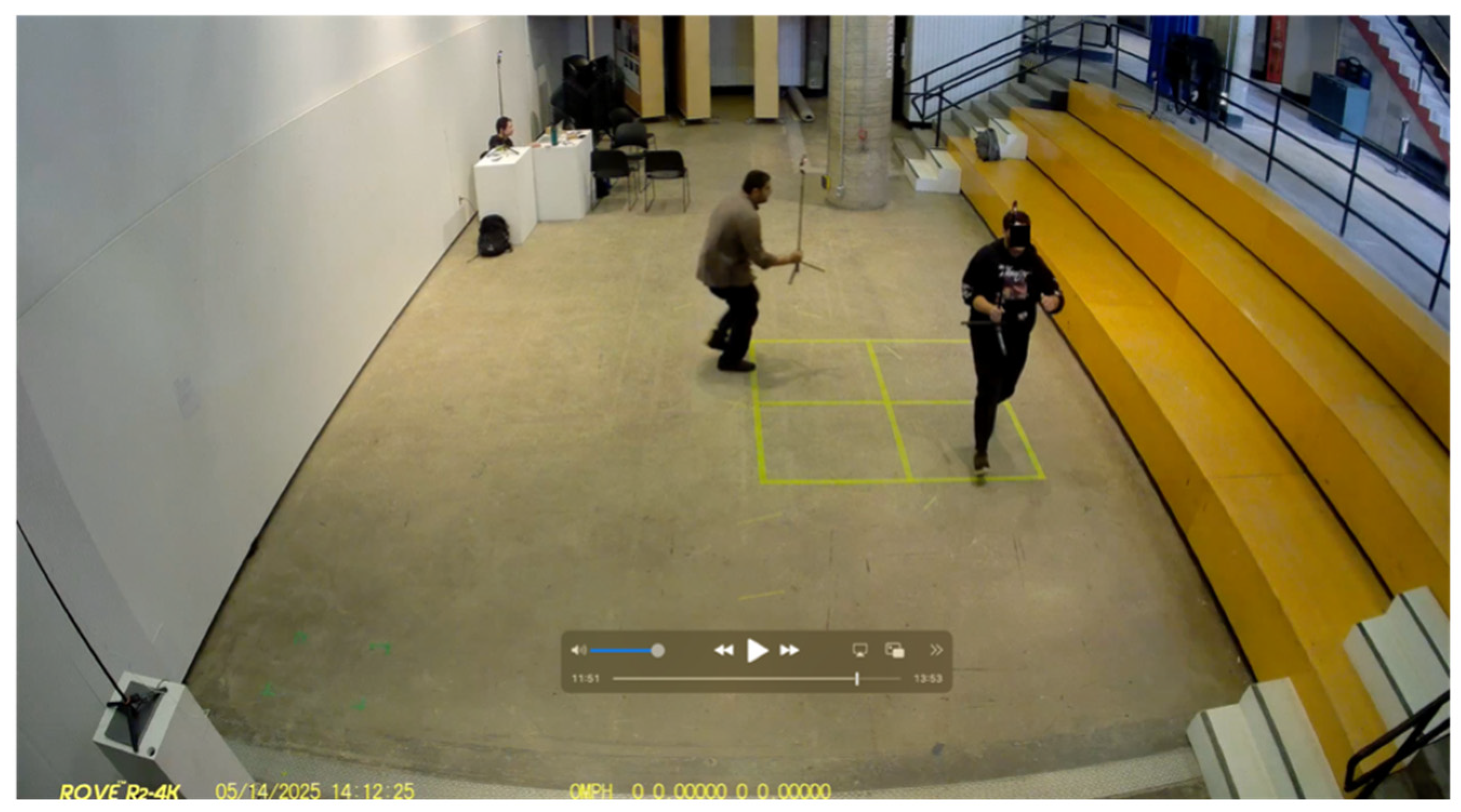

Static and dynamic experiments were conducted using ESP32s3 UWB modules. The TDMA approach was utilized. The study scheduled a 20 ms time slot for the tag to communicate with each anchor. This technique solved issues such as signal interference and transmission collisions, ensuring reliable communication among the devices. The PET was estimated with an MAE of 148 ms across all scenarios. As previously mentioned, the result was affected by the camera angle because the observation was taken from a single perspective. A recent study by Krebs and Herter [

57] claims that the number of anchors directly influences temporal performance, highlighting scalability as a critical concern. That study recommended transitioning from ToF to TDoA measurements or adopting a hybrid approach. In both approaches, time synchronization is essential. This will help in utilizing UWB in tracking multiple road users in heavy traffic.

Zhang et al. [

58] and Tiemann [

29] encountered the same multi-user interference challenges. Zhang et al. [

58] noted that a UWB sensor encounters challenges in an indoor environment due to signal interference. For instance, intense interference can cause unusual fluctuations, including time delays within the data and transmission collisions. This study aligned with the findings and faced the same challenges. Tiemann’s [

29] study resulted in errors in ranging and gaps in detections of up to 10 s and significantly reduced the ranging rate in TWR. Tiemann [

29] suggested using STS because of its capability of preventing errors in ranging, but it will decrease the ranging rate. However, implementing STS is challenging because it requires modifications at the physical layer by the device manufacturer. STS is different than TDMA for multi-user interference mitigation. For instance, TDMA assigns a fixed time slot, i.e., 20 ms, to communicate with the anchor. STS randomizes transmission sequences at the physical layer to reduce interference. More methods need to be investigated to reduce errors and increase the detection rate.

In this research, the local laptop was a MacBook Pro M2, supported with Wi-Fi 6e. This could have potentially affected the results of the experiments. For example, some studies showed the impact of Wi-Fi 6e interference on UWB. Brunner et al. [

59] claim that Wi-Fi 6e and UWB can operate in the 6 GHz frequency band, which may potentially disrupt communications and reduce the accuracy of ranging detections. Moreover, the researchers suggested investigating the impact of Wi-Fi 6e on different UWB hardware.

Future research should investigate further improvements in UWB technology. Coppens et al. [

60] outlined future research directions, such as antenna design challenges, physical layer challenges, data link layer challenges, application layer challenges, and UWB regulations. Lee et al. [

61] proposed a prototype UWB monocone antenna design suitable for vehicle-to-everything applications. The prototype has an omnidirectional radiation pattern and can cover a bandwidth of 0.75 GHz to 7.6 GHz. Field experiments conducted in the study showed a high communication range and lower packet error rates compared to other antennas.

The cost of UWB sensors is an important consideration for researchers and users. The technology should be affordable to the public. The reduction in costs is important for engineers, researchers, and innovators to conduct field experiments effectively. Wu, P. [

62] compared UWB and other technologies, such as Wi-Fi and Bluetooth, for cost-effective indoor positioning. Moreover, the researcher claimed that the cost of UWB equipment deployment is expensive because it requires multiple devices for positioning.

Key Limitations

The primary objective of this study was to evaluate UWB performance and explore its limitations in estimating the PET under controlled conditions before conducting experiments in real vehicle–pedestrian scenarios. The intention is to establish a safe and reliable system to localize multiple tags and overcome its limitations. Therefore, without prior validation, this could result in unacceptable risks for conflict-based experiments between pedestrians and vehicles.

The study did not utilize time synchronization techniques, such as master–slave and cloud global time, for the open hardware without interference, as offline storage was sufficient to achieve synchronization using laptop global time. Moreover, the study will investigate the technology in mixed traffic with different PET thresholds to identify future challenges, especially under NLOS conditions. Che et al. [

63] investigated the elimination of NLOS effects using machine learning techniques (ML), including Support Vector Machine (SVM), K-Nearest Neighbours, Decision Tree (DT), Naïve Bayes (NB), and Neural Network (NN), to reduce localization error. Therefore, future work will examine ML techniques to improve the accuracy of PET estimation.

Grosswindhager et al. [

64] questioned whether existing solutions can properly scale with demand. They state that “Unfortunately, most of the existing solutions based on UWB technology focus on achieving a high localization accuracy, often disregarding properties such as multi-tag support and high update rates”. Therefore, the focus on accuracy results with limited tag capacity due to extensive message exchange and collision-avoidance scheduling should be expanded.

Other wireless sensors, including Bluetooth/BLE and Wi-Fi, use channel hopping to mitigate interference. For instance, BLE uses 40 channels; the first 26 are used for general connections, and the remaining are used for advertising. The BLE sensors are known for channel hopping for interference mitigation [

65]. Channel hopping is a communication technique where a device switches between multiple frequency channels during operation. Bluetooth Classic utilizes 80 channels and employs Frequency Hopping Spread Spectrum (FHSS) to minimize interference. The Bluetooth Classic’s channel hopping switches 1600 times per second [

66]. The 2.5 GHz Wi-Fi band uses 14 channels, but only three are non-overlapping: 1, 6, and 11. Although wireless sensors, including Wi-Fi, BLE, and Bluetooth Classic, use multiple narrow frequency channels to reduce interference, UWB uses only two main channels, 5 and 9, because each channel occupies a very wide bandwidth, resulting in limited non-overlapping channels that can fit within the frequency range. UWB communication can be separated by a time domain [

67,

68]. Charlier et al. [

69] explored the potential of using time-slotted channel hopping for UWB technology. The study achieved a slot rate of 400 slots per second and a duration of 2.5 ms for each time slot, reaching a packet delivery ratio greater than 99.999% by using Time-Difference of Arrival (TDoA). As a result, the study can potentially allow high-density indoor positioning. The researchers suggested applying the technique to DS-TWR.

This study only explored a fixed anchor and tag roles as initiators and responders. Sakr et al. [

44] looked at fixed-role networks and dynamic-role networks. In a fixed-role network, each node, such as a tag and anchor, is assigned a fixed role (initiator or responder). In a dynamic role network, anchors and tags represent the change in role between initiator and responder. Therefore, this will be investigated in future work.

6. Conclusions

This study assessed UWB-based positioning systems in both static and dynamic indoor environments using two tags. The research explored three methods to establish a common clock. Initially, the study examined the performance of UWB in ranging when using two tags to track their trajectories. This initial experiment highlighted the importance of time synchronization, but it required changes in the hardware to achieve time synchronization between the tags. Secondly, the study utilized a clock reference as a common time source for PET estimation between the devices. Finally, the master–slave synchronization technique was utilized by dedicating a third tag as a master clock. The study showed that many challenges, including signal interference and transmission collisions, resulted in time gaps between detections.

Later, an open hardware “ESP32s3 UWB module” was used to overcome these challenges. The study employed the TDMA approach by allocating a 20 ms time slot for communication between UWB devices. This helped mitigate signal interference and improve trajectories. The antenna calibration process was utilized to improve range measurement accuracy. The research showed that the MAE of PET was 148 ms across all scenarios. Ranging experiments were conducted to evaluate the maximum range between devices. The study found the maximum range between devices reached 165 m at a height of 1.7 m. However, after reaching a height of 2.7 m, the maximum range increased to 300 m.

Future research should explore additional techniques to achieve time synchronization between the devices using open hardware. Researchers should focus on addressing future technical limitations, such as using multi-tag scenarios. Time synchronization should be considered by broadcasting the time from one master device to other UWB devices. Future studies should investigate the ground effect on ranging with multiple road surfaces, such as concrete or pavement. Future studies will investigate methods for self-calibrating and optimizing scheduling time slots and channel hopping to improve communication and reduce signal interference when multiple tags are used. Once a reliable system is established under a controlled environment, the system can be utilized for mixed traffic and scenarios between road users.

Future research should expand the estimation of the time-to-collision and PET at higher speeds and in different trajectory scenarios using anchors and tags. Other SSM indicators should also be explored. Future work could apply advanced smoothing techniques to enhance trajectories. Additional studies can be conducted involving various road users at signalized intersections or roundabouts with different smoothing filters to enhance accuracy. AV–pedestrian interactions should be investigated by integrating UWB to play a significant role in ensuring efficient and safe transportation systems.