1. Introduction

Iris L. (family Iridaceae) is a diverse genus with over 300 taxa distributed worldwide, mostly in the northern hemisphere [

1,

2]. In addition to conservational importance, many wild and cultivated taxa provide great horticultural value [

3]. Phylogenetic and evolutionary studies of relationships of wild

Iris taxa have long been challenging for several reasons. Namely, wide distribution, morpho-ecological diversity, multiple hybridisations, and convergent evolution processes, make definitive statements of the origin and evolution of taxa in the genus

Iris very difficult [

4,

5]. To resolve a myriad of uncertainties and issues related to taxonomic and phylogenetic relationships within the genus

Iris, extensive work was performed on morpho-anatomical features, palynology, phytochemical constituents’ analysis, cytogenetic traits, and molecular analysis [

6,

7,

8,

9]. Despite different approaches to lower (and individual) taxonomic categories, most authors agree on the classification of the genus

Iris into six subgenera, which are divided into sections and series [

1,

10,

11].

Most of the European native taxa of the genus

Iris belong to the subgenus

Iris L., section

Iris L. (so-called “Pogoniris”), represented by numerous rhizomatous

Iris taxa characterised by bearded outer tepals. Less prevalent on the European territory are taxa from the subgenus

Limniris (Tausch) Spach, section

Limniris (Tausch) Spach (so-called “Apogoniris”), which are rhizomatous irises whose outer tepals are without a beard [

1,

3]. The broad Alpine-Dinaric, as well as the surrounding Mediterranean and Pannonian area of Europe (where irises for our study were sampled) is characterised by peculiar eco-climate conditions which have caused a great morphological variability of some

Iris populations and groups. Their variety has resulted in ambiguous systematic status of some regional, especially endemic,

Iris taxa [

5,

8]. Some of them are recognised in the national and regional floras [

12,

13] and still have an unclear phylogenetic and classification status. Some of them neither are accepted in the World Checklist of Selected Plant Families [

2], nor are molecularly researched in detail. Therefore we intended to molecularly study some, insufficiently researched and/or globally neglected taxa; namely:

I. x

croatica Horvat et M. D. Horvat (endemic in Croatia and Slovenia),

I. illyrica Tomm. ex Vis.(endemic in Croatia, Slovenia, and Italy),

I. sibirica L. subsp.

erirrhiza (Posp.) Wraber (endemic in Bosnia and Herzegovina, Croatia, and Slovenia) and

I. x

rotschildii Degen (endemic in Croatia). However, in this study we paid special attention to the validly described [

14] and accepted [

2], molecularly unexplored endemic species

I. adriatica Trinajstić ex Mitić (

Figure 1 and

Figure 2).

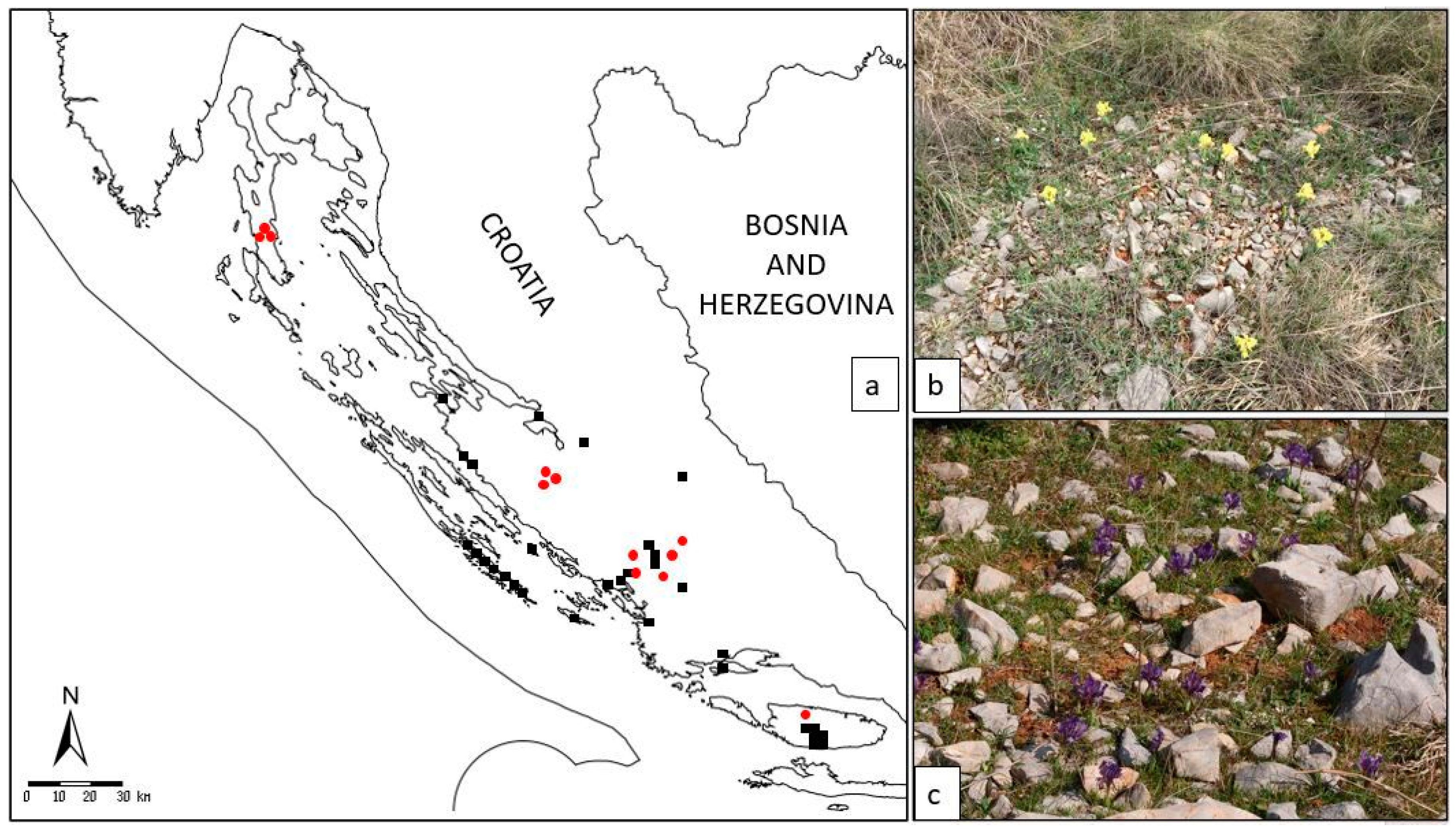

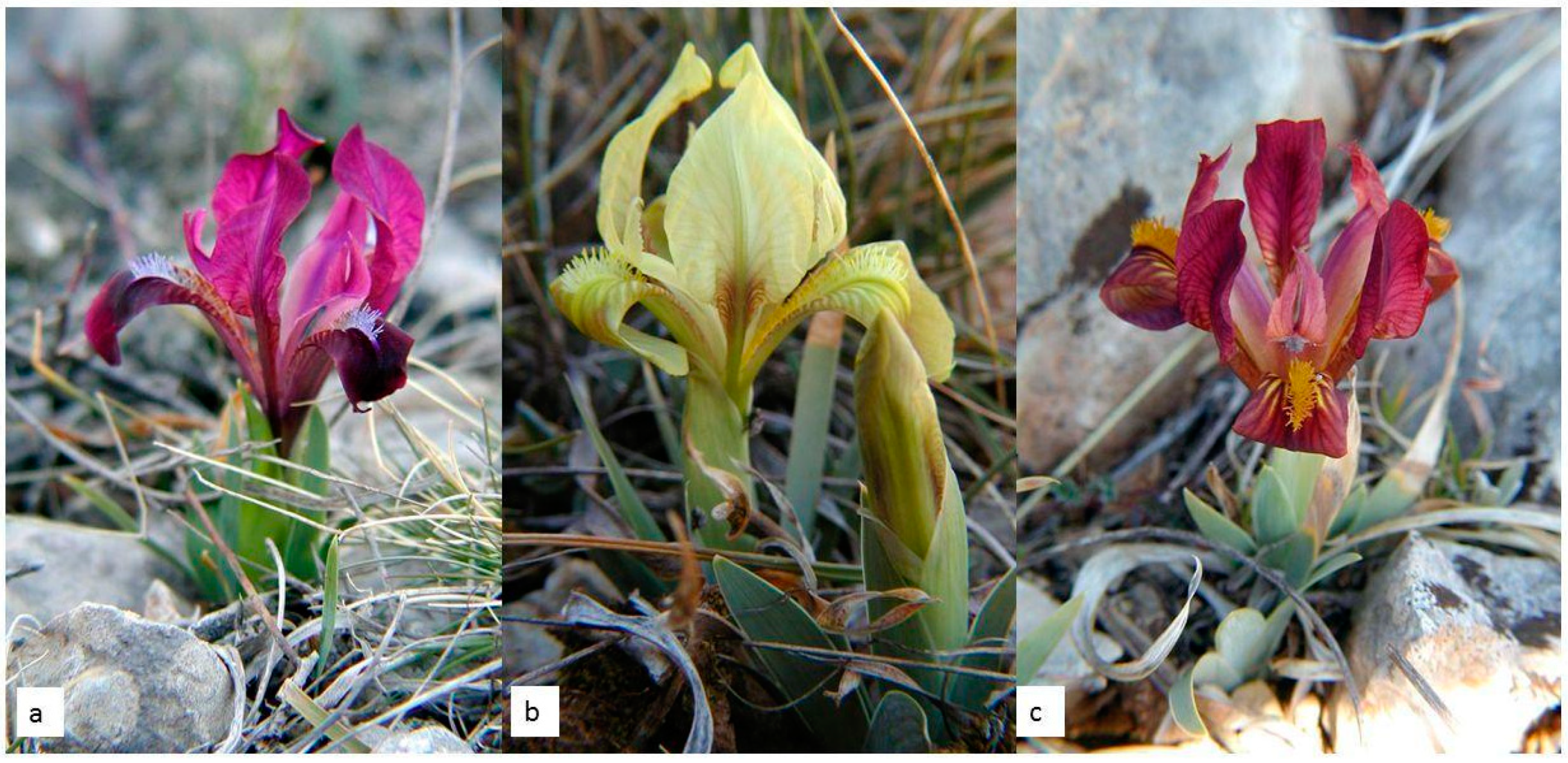

I. adriatica (

Figure 1a–c) is a narrow endemic plant from the

I. pumila complex, characterised by an extremely dwarf stem (one of the smallest species within the genus

Iris) and relatively large yellow, violet, or purple solitary flowers (

Figure 1a–c) [

14].

It is confined to a few Croatian localities in the wider area of Dalmatia and classified as a NT (near threatened) species [

13]. Given that the localities newly recorded by authors are spatially distant from the previously catalogued specimens (

Figure 2), questions of subspeciation or higher-level genetic divergence can arise. All the more so as the recent metabolic profiling [

15] revealed a notable diversity between the ecotypes and their pharmacological and chemotaxonomic potential.

Since the 1990s, when molecular biology techniques have become widely accessible, taxonomical biology has been driven towards using molecular methods to establish and re-establish evolutionary relationships between species [

16,

17]. Tang et al. [

18] developed 400 ortholog-specific EST-SSR (Expressed Sequence Tag—Simple Sequence Repeats) markers, which can be reliably used to distinguish between the species in the

Iris genus, providing a cheap and efficient way to resolve taxonomical discrepancies. Simple Sequence Repeats or microsatellites are present in most species; they are usually locus-specific, multiallelic, polymorphic, and co-dominant and are as such ideal candidates for discriminating between

Iris species [

19].

AChloroplast gene sequences are often used for plant phylogenetic studies and DNA barcoding because of the relatively low evolutionary mutation rates, their uniparental inheritance, high level of genetic diversity, and absence of recombination. Many candidate plastid regions have been suggested as the plant barcode and have as such been extensively tested [

20,

21,

22]. However, to this end, a single marker has not yet been found which could reliably distinguish between a majority of plant species. Different combinatorial approaches have been used in different instances, to set on a final consortium [

23]. Plastid DNA regions

rpoC1 and

ndhJ used previously to evaluate plant phylogeny with low taxonomic variation [

22] seemed appropriate for our study.

One of the basic genomic parameters that characterise the species and represent one of the important plant traits is the total amount of DNA in the unreplicated haploid or gametic cell nuclei, referred to as the C value or genome size [

24]. Genome size data have numerous applications: They can be used in comparative studies on genome evolution, or as a tool to estimate the cost of whole-genome sequencing programs [

25]. Currently, the largest updated plant genome size database—Plant DNA C-values database contains data for 12,273 species and among them 65 C-values for 44 species of genus

Iris [

26]. For most species involved in our study C-values are measured in several studies [

27,

28,

29]. Different methods were used for the measurement of plant DNA content, but flow cytometry has become the method of choice due to its reliability, simplicity, and relatively low cost [

30,

31].

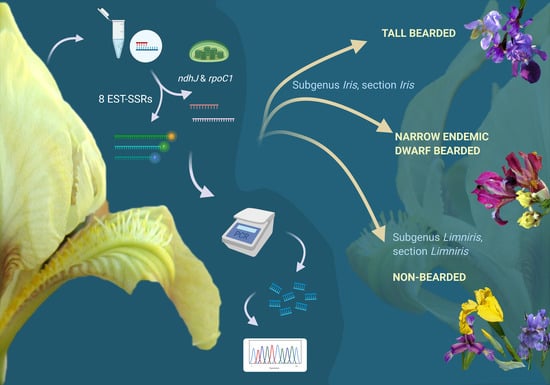

A noticeable lack of efforts to molecularly resolve remaining issues in Iris phylogeny and taxonomy on the Alpine-Dinaric area (including the adjacent areas of Mediterranean and the Pannonian Plain) in the context of conservation was extremely important when designing the study. Hence, to provide molecular insights into phylogenetic relationships of selected wild Iris taxa of the wider Alpine-Dinaric area, with a special emphasis on regional endemics and molecular evidence for their conservation, the aims of our research were: (i) To characterise representative and critical Iris taxa from the wider Alpine-Dinaric area by nuclear (SSR) markers; (ii) to clarify the genetic divergence within and between several wild (local endemic) and cultivated Iris populations through chloroplast DNA (cpDNA) markers; (iii) to present the first molecular description of a nearly threatened narrow endemic dwarf species I. adriatica; and (iv) contribute to the efforts of establishing optimal molecular markers for detecting taxonomic and phylogenetic relationships within critical taxa of the genus Iris.

3. Discussion

In our study, we applied 8 SSR markers developed by Tang et al. [

18] which proved to be highly polymorphic and amplified alleles across the 39

Iris ecotypes and cultivars. We were not able to utilise the IM61 marker recommended but the remaining markers provided sufficient resolution to distinguish between our samples. We observed the greatest allelic diversity on IM196 and IM327 in concurrence with the aforementioned study; however, the observed number of alleles per locus in our study was significantly lower (average 8.8) suggesting greater phylogenetic similarity across all of our samples. Although it is comparable with the average number of alleles per locus observed within the group of 13 yellow-flag, Siberian, and tall-bearded

Iris cultivars analysed by [

18]. In our case, a small population size could be the reason for low allele frequency. Genetic similarity ranged from 0.23 to 0.8 and 0.26 to 1.00 among Alpine-Dinaric taxa from the subgenus

Iris (section

Iris) grouped in the UPGMA clusters I and II, respectively. The highest genetic similarity was intraspecific (Dice = 1; I19 and I21; I13 and I19; I30 and I31), whilst the lowest were interspecific (Dice = 0.23; I22 and I41 in cluster I; Dice = 0.26; I16 and I10; I16 and I11 in cluster II). Genetic similarity between endemic dwarf ecotypes of

I. adriatica grouped within a separate subcluster, and correlated with the locations of origin, ranged from 0.55 to 1.00, implying significant and disperse genetic diversity among ecotypes. Taxa from the subgenus

Limniris (section

Limniris) displayed genetic similarity in a range from 0.07 to 0.72, the highest between samples of

I. sibirica subsp.

erirrhiza. Only a few SSR markers were needed to identify (distinguish) ecotypes and species.

The unique microsatellite profiles were established as described in the method section below, nevertheless, we acknowledge that the SSR analysis can differ from lab to lab as the method inherently produces high numbers of edge cases where a judgment call has to be made. An example of an edge case is the apparent presence of 3 alleles in what we presumed (and confirmed for

I. adriatica) to be 2n = 2x species. As described, this was resolved by establishing a common SSR profile for those particular samples, since our subsequent analysis methods rely on the binary presence or absence of a particular allele and a presence of 3 alleles would likely confound the result and be factually incorrect. To resolve such an edge case a full sequencing run could reveal genomic mutations, such as translocation, or perhaps other properties of the genome at that position which would allow the probes to bind in this particular way. Further, as

I. x

germanica is a suspect tetraploid [

5,

18,

33], the additional genetic information could skew the subsequent phylogenetic analysis as additional peaks appeared in positions only in one individual and could thus not be compared to any other values in the study, carrying an extremely low PIC. For our analysis such peaks were considered to be outliers; however, we are not suggesting they are not valid data in different subsamples.

This means that for any analysis the attribution of a particular profile needs to be internally consistent and cannot be used at face value form any further studies which want to include the same dataset. In our case, we employed the algorithm described in the methods to come to a conclusion which was cross-examined within the research group to preserve the established logic of sorting different cases. The final analysis of genetic relationship relies on the presence and absence of specific alleles so for our purposes the aim was to obtain the same profiles for the same species when attributing an SSR profile, without knowing which species the profile belongs to. Since a matching algorithm can only be established ad-hoc after accessing the reads, there is a potential to introduce some bias into edge-case decision making. Nevertheless, we are confident in our results several reasons; sample duplicates were included as an internal control and independently produced the same profiles using the same “blind” determination method, the chloroplast marker analysis largely produced the same clustering, profile differences between presumed same species are minimal, our described SSR relationship mirrors the relationships which were confirmed or predicted using taxonomic, botanical or other methods.

Different combination of chloroplast genome sequences were proposed for species discrimination, such as

rpoC1,

rpoB, and

matK;

rpoC1,

matK, and

psbA-trnH; [

34] and

rbcL and

trnH-

psbA [

35]. In a recent review [

23], authors Saddhe and Kumar discussed the utility of plastid markers to differentiate between different species within plant divisions, where they establish

ndhJ as a good candidate marker for barcoding angiosperms. Additionally,

rpoC1 is often used as a supplementary marker to increase the barcoding depth of samples [

36]. Plant Working Group (PWG) of the Consortium for the Barcoding of Life (CBOL) recommended the combination of

rbcL and

matK as the plant barcode [

20], while

rpoB and here applied

rpoC1 showed markedly lower discriminatory power. Chloroplast marker

matK is recommended as one of the best DNA barcoding candidates for species discrimination [

20,

37]. However, this chloroplast region proved to be difficult to amplify and sequence in certain taxa, and additional universal primers and optimisation of PCR reactions were necessary [

38,

39]. In our study, the preliminary amplification of

matK sequences was unsuccessful and the testing of additional plastid markers is foreseen. However, the combination of

ndhJ and

rpoC1 revealed to be adequate for discrimination up to the series taxonomic level, indicating the possibility of applying additional candidates for the species discrimination. As discussed, a plastid marker with sufficient resolution would be operationally favourable for widespread utility in discriminating between different species. Up to date a few phylogenetic studies based on chloroplast markers were carried out on

Iris [

6,

40,

41,

42]. Neither

ndhJ nor

rpoC1 was not tested in any

Iris genus study.

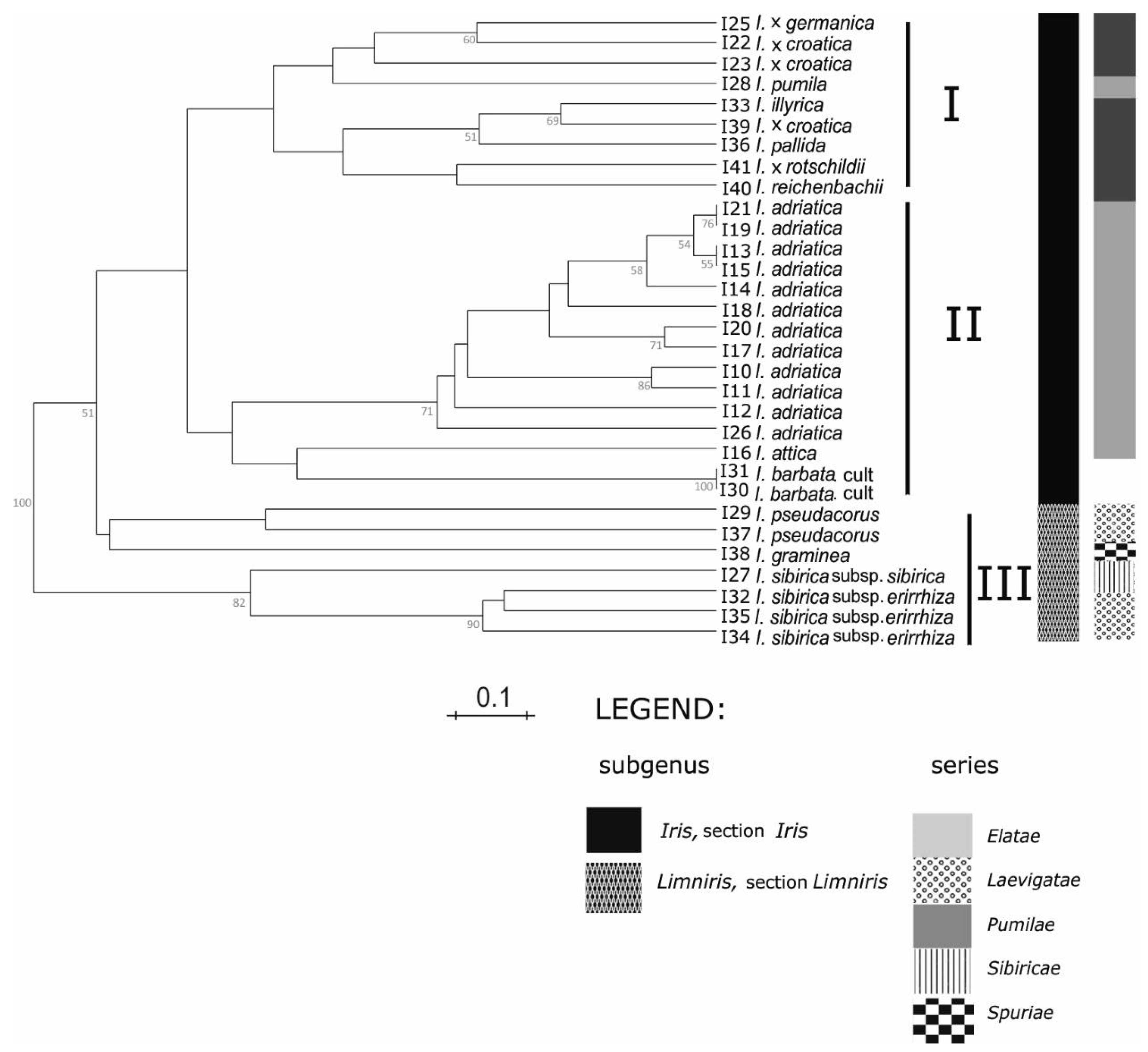

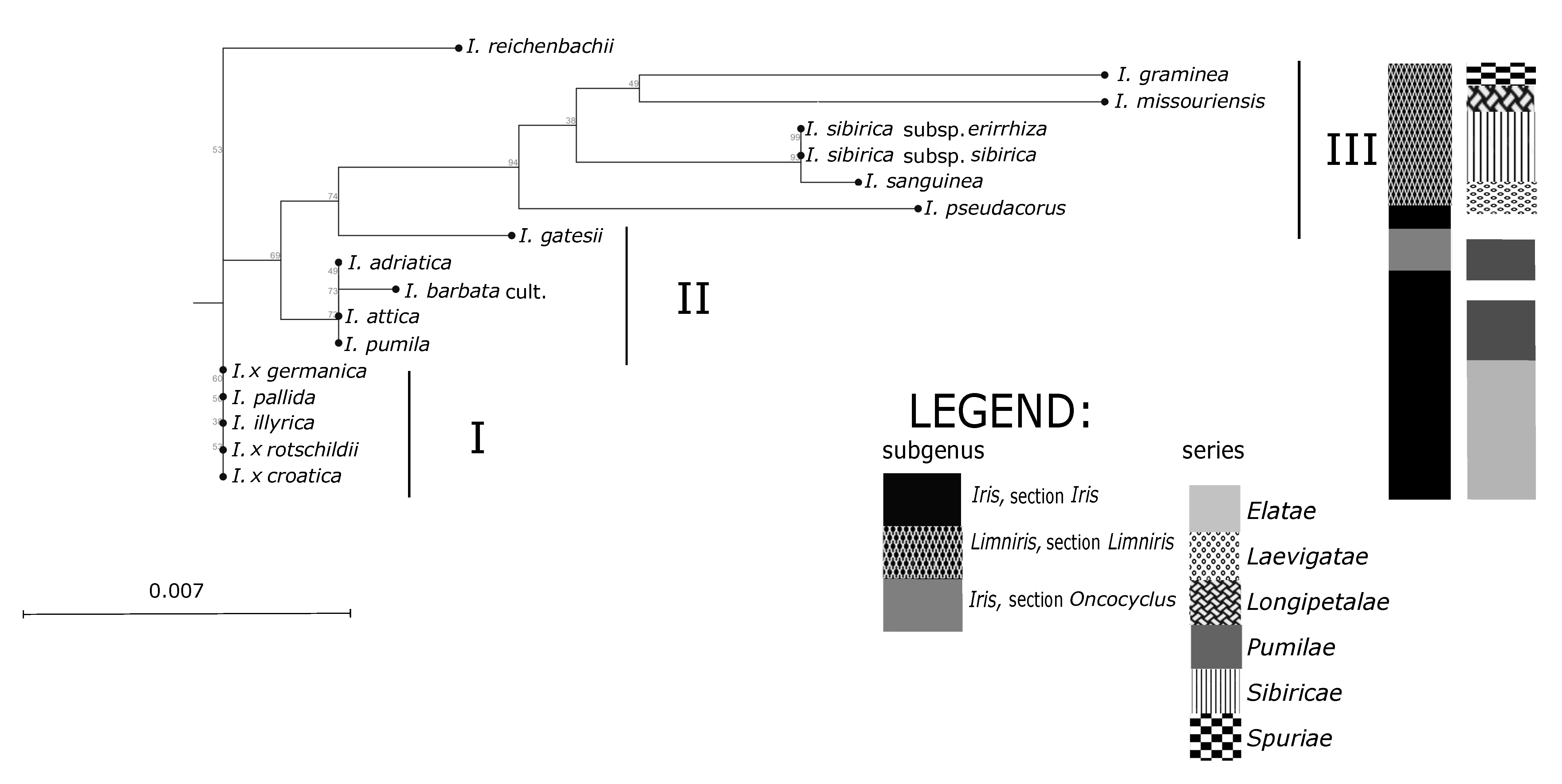

Groupings of the

Iris taxa from the broader Alpine-Dinaric area, observed in our research by both sets of molecular markers (

Figure 3 and

Figure 4), mostly correspond to proposed phylogenetic relationships based on palynological features [

8]; a clear distinction between the subgenera

Limniris and

Iris and within the majority of the lower taxonomic

Iris categories of sections and series emerges. The anticipated exception is the position of analysed NCBI sequence of Middle Eastern species

I. gatesii (

Figure 4), which separated within the subgenus

Iris in an individual cluster, as it belongs to the different series

Oncocyclus (Siemssen) Baker [

1]. However, the unexpected exceptions are positions of the species

I. pumila based on SSR markers (

Figure 3), and of

I. reichenbachii based on ML analysis (

Figure 4). Molecular analysis of both sets of markers (

Figure 3 and

Figure 4) in principle resulted in the creation of three main clusters: Two of three clusters covering rhizomatous taxa from the subgenus

Iris, section

Iris, with a beard (“Pogoniris”, [

3]), while the taxa from the subgenus

Limniris, section

Limniris, rhizomatous irises with falls without a beard (“Apogoniris”, [

3]) were grouped in the third cluster (

Figure 3 and

Figure 4). For the ML analysis control NCBI sequences: Of

I. sanguinea (subgenus

Limniris; sect.

Limniris, series

Sibiricae (Diels) Lawrence) and

I. missouriensis (subgenus

Limniris; sect.

Limniris, series

Longipetalae (Diels) Lawrence), grouped with other members of the same subgenus (

Figure 4); and of

I. gatesii (subgenus

Iris; section

Oncocyclus) made a separate branch between samples of “Apogoniris” and the rest of the “Pogoniris” (

Figure 4). Such results are in agreement with previous studies and monographs of the genus

Iris [

1,

3,

11,

41,

43].

Within the subgenus

Iris, section

Iris, on the series level, one cluster (based on both sets of molecular markers;

Figure 3 and

Figure 4) comprises the group of mostly tall bearded irises and covers the series

Elatae Lawr. [

10]. The second cluster covers the group of dwarf bearded irises and matches the series

Pumilae Lawr. [

10], except for

I. pumila grouping in the first cluster based on SSR markers analysis (

Figure 3). However, plastid markers (

Figure 4) did not discriminate analysed taxa within neither series

Elatae (the only exception is

I. reichenbachii) nor

Pumilae. In our study chloroplast markers

ndhJ and

rpoC1 provide a weaker resolution into the species, concurrent with other authors [

22]; however, we acknowledge that the analysis of sequence data is quicker and much less prone to human error and enables clustering comparison across different studies if the sequences are made publicly available. Further, our study looked at only two plastid regions, as compared to eight microsatellite loci. Therefore, we would recommend the utilisation of SSR markers for subsequent analysis supplemented by a plastid marker combination for the genus

Iris, until a single plastid marker combination is established as a convention.

According to SSR markers analysis (

Figure 3), within the cluster I, two subgroups were formed: In the first are two samples of tall bearded

I. x

croatica,

I. x

germanica, and, unexpectedly, dwarf bearded

I. pumila, whereas one sample of

I. x

croatica is grouped with other analysed tall bearded irises within the second subgroup. Although its taxonomic position is critical and still unresolved, the taxon

I. x

croatica is considered as a native endemic taxon in northern Croatia and Slovenia [

12,

13,

44]. Likely due to morphological similarities, it is often mixed with and named as a synonym for

I. x

germanica [

1,

2,

5,

13], which is, in our opinion, distributed worldwide only as a cultivated hybrid species [

1,

9]. The fact that the WCSP [

2] wrongly “declares”

I. croatica Horvat & M.D. Horvat as an illegitimate name, due to an incorrect replacement with

I. croatica Prodan, provokes further taxonomic confusion [

45], explained in detail in [

5]. The close relationship between

I. x

croatica and

I. x

germanica was noticed by examining both plant and pollen morphology [

8] (B. Mitić, personal observations) and is confirmed with our results—their joint sub clustering (

Figure 3). However, they are both tetraploids of yet unresolved origin with reported chromosome numbers of 2n = 44 for

I. x

germanica, and 2n = 48 for

I. x

croatica [

5,

46]. Two earlier speculations about (auto) tetraploid origin of

I. x

croatica both agreed that the progenitor species for that hybrid is

I. pallida, although this is yet to be cytogenetically confirmed [

5,

8]. Grouping a sample of

I. x

croatica together with

I. pallida and

I. illyrica within the second subgroup in our results (

Figure 3) confirms the proximity of tetraploid

I. x

croatica and presumed progenitor species

I. pallida.

Considering the clear discrimination within lower taxonomic subgroups such as series, obtained by the applied marker systems (

Figure 3), the status of other closely related taxa from the so-called

I. pallida complex could be discussed. Taxonomic relationships within the complex have not been fully explored and it is not yet clear whether the taxa of this complex have the status of species or subspecies. Namely, the majority of taxa from this complex (including representatives from our research—

I. pallida and

I. illyrica) were defined at the species level and extracted, apart from the series

Elatae into the new series

Pallidae (A. Kern.) Trinajstić [

47]. Although earlier taxonomic researches of

I. pallida complex [

48,

49] have supported such taxonomic treatment of its taxa, a later palynological study [

8] indicated their return into the status of subspecies level (as classified by WCSP [

2]), and of the series

Pallidae back into the series

Elatae. Results of our study are in accordance with the last hypothesis as both marker systems (

Figure 3 and

Figure 4) grouped members of those series closely together.

The taxon

I. x

rotschildii from the series

Elatae also garners considerable attention in the context of this study. So far, this narrow endemic iris is known from a single locality on Mt. Velebit (Croatia). It is described as a natural hybrid between species

I. illyrica and

I. variegata L. [

1,

50] with observed morphological, palynological, and cytogenetic variabilities [

46]. Some of the mentioned features confirm the hybridogenous origin of this taxon. Despite this, no further molecular studies have been done on the taxon to confirm its claimed status. This is the likely reason it was recently considered as a synonym of

I. x

germanica by WCSP [

2]. Unfortunately, due to hard-to-reach mountainous terrain (with mines still present in the area) and the small number of specimens in the only known population on Mt. Velebit (B. Mitić, personal observations), only one sample of this taxon was included in our analysis. Bearing this in mind, the SSR profile of

I. x

rotschildii that shares at least one allele on all analysed loci with

I. illyrica as well as their position in the same UPGMA subcluster additionally support their parent-sibling relationship (

Figure 3). Moreover, although

I. x

germanica and

I. x

rotschildii are presumed synonyms [

2], their discrimination by SSR could disprove that assumption and would favour the placement of

I. x

rotschildii within a separate taxonomic position. However, further extensive detailed molecular study of

I. x

rotschildii and its presumed parents is needed to confirm both its separate taxonomic status and its difference with

I. x

germanica.

Furthermore, unexpected discrepancies occur in the placement of

I. reichenbachii, which was positioned in the same UPGMA subcluster as

I. illyrica,

I. pallida, and

I. x

rotschildii (

Figure 3) and also as an outgroup in ML dendrogram (

Figure 4). Namely,

I. reichenbachii is native in mountainous regions of the Balkan Peninsula and SW Romania, known as parental species of some natural hybrids [

5], and according to [

10] was firstly placed in the series

Pumilae. However, according to both chromosome numbers 2n = 24, 48 [

43] and pollen analyses [

8] it seemed to fit better in the series

Elatae. Nevertheless, outgrouping of

I. reichenbachii in our ML analysis (

Figure 4) might indicate its specific position between two series that still needs to be explored, as it has the same number of chromosomes [

5] and pollen grains [

8] as tall bearded irises and is morphologically quite dwarfish [

43]. Further, its genome size (1C value) is intermediate between some members of both series

Elatae and

Pumilae [

33].

Cluster II in our study (

Figure 3 and

Figure 4) covers mostly dwarf bearded irises. However, except for

I. pumila based on SSR markers, grouping within the first cluster (

Figure 3), together with tall bearded

I. x

croatica and

I. x

germanica. Given current evidence, we speculate that the grouping may have happened due to the normalisation of the chromosomal content applied, and treatment of SSR data as codominant, with maximally two alleles counted. An additional element could be genetic variability of

I. pumila, evident from genome size of this tetraploid species (2n = 32), differing in several previous studies (e.g., 1C = 13.20 pg [

27]; 1C = 6.81 pg [

33]; 1C = 10.64 pg [

51]). Furthermore, this taxon is supposed to have the same hypothetical ancestor as tall bearded irises (with x = 4 [

3,

43]), and is often known as the parental species (together with some tall bearded irises as second parents) of many native and artificial hybrids [

43].

On the contrary, all other investigated samples of dwarf bearded irises of the series

Pumilae [

10] grouped in a separate cluster II based on plastid markers (

Figure 4). Such results are in accordance with pollen morphology of dwarf bearded irises [

8,

52] and confirm their separate taxonomic position, and belonging to the same

I. pumila complex [

14]. Since

I. attica is the only member of the complex with the status of a subspecies, and with others having equal rank of species in the WCSP [

2], our results (

Figure 3 and

Figure 4) suggest that they should be treated at the same taxonomic rank. Therefore, further research is needed to corroborate (or disprove) our statement about taxonomic relationships within the whole

I. pumila complex.

Meanwhile, special attention in our study was dedicated to one member of the complex—a relatively-recently described diploid (2n = 16) species

I. adriatica [

14], native and endemic to Croatia. Namely, to prepare the basis for its conservation, because of its nearly threatened species status [

13], we were particularly focused on its molecular features. Evidence about taxonomic and phylogenetic values of palynological and phytochemical features of

I. adriatica are well documented [

8,

15]. However, thus far, this species has not been researched on a molecular level. In the present results (

Figure 3) we documented diversity of different populations of the species

I. adriatica, showing the existence of geographical ecotypes. In particular, the UPGMA grouping (

Figure 3) of established ecotypes corresponds well with the geographical origins of the samples (

Figure 2,

Supplementary Table S1): The island populations (sample numbers I26 island of Brač; I10, I11, and I12 island of Cres) have separated from the land coastal populations (

Figure 3,

Supplementary Table S1, other samples). Therefore, we assume that island populations might be a specific ecotype of the typical species. Within inland populations, we were particularly interested in the population of the hinterland population “Brnjica-Pokrovnik”, which has been singled out as an ecotype based on phytochemical analysis [

15]. In our analysis (

Figure 3, sample no. I18) it has a separate branch in the dendrogram, although it is “surrounded” by other inland populations. Therefore, it is obvious that potential inland ecotype(s) require additional investigations. One more reason in favour of the separation of ecotypes is the fact that “Brnjica-Pokrovnik” population is growing on an open calcareous meadows (mainly belonging to the

Festuco-Koelerietum splendentis Horvatić 1963 association), whilst the rest of the researched populations grow on limited rocky pastures and hills (mainly belonging to the

Stipo-Salvietum officinalis Horvatić 1985 association), very often endangered by the succession, i.e., overgrowth with macchia.

Furthermore, in this study we present the first genome size estimation of

I. adriatica measured by flow cytometry and expressed according to [

24] as 2C value = 12.639 ± 0.202 pg. Observed value of genome size for

I. adriatica we could hardly compare with values of all other members of the complex

I. pumila, since the data are known only for tetraploid species

I. pumila [

27,

33,

51]. However, as previously mentioned, data for this tetraploid species indicates its variability. Our results of genome size value for diploid species

I. adriatica are the first data about genome size for this strictly endemic, near threatened species and should contribute to its future conservation. The 1C value of

I. adriatica is similar to that of tetraploid

I. pumila obtained by [

33]. Such results should confirm belonging of both species to the same complex. Additionally, similar deviations in 1C values as in the species

I. pumila, were observed for the species

I. x

germanica: Our results of 2C = 24.249 pg for this “control” species could be compared to the result (1C = 12.45) of [

27], while the value of 1C = 5.87 for the same species was observed by [

33]. Therefore, the genome sizes of critical taxa of the genus

Iris require further, more complex research.

In our results within the third cluster (

Figure 3 and

Figure 4) all samples of so-called “Apogoniris” taxa [

3] grouped together, further all are representatives of the subgenus

Limniris, section

Limniris. Such results are in accordance with some previous research of molecular phylogeny of these taxa [

40,

53,

54]. Additionally, our analysis based on both sets of markers (

Figure 3 and

Figure 4) resulted with different subclusters within the subgenus

Limniris. Namely, mentioned subgroups correspond well to the series as a lower taxonomic level (according to [

1,

10]):

Laevigatae (Diels) Lawrence (

I. pseudacorus),

Sibiricae (Diels) Lawrence (both subspecies of

I. sibirica), and

Spuriae (Diels) Lawrence (

I. graminea). The analysed NCBI sequences of “Apogoniris” taxa (

I. missouriensis and

I. sanguinea) additionally support that distinction (

Figure 4), they grouped with other members of the subgenus

Limniris, section

Limniris. Moreover,

I. sanguinea, which belongs to the series

Sibiricae [

1], grouped close to other members of this series.

Furthermore, all samples of

I. sibirica sensu lato (series

Sibiricae) grouped apart from other members of the subgenus

Limniris (

Figure 3 and

Figure 4), and created further subclusters (

Figure 3). This was especially interesting because of the still unclear position of the Alpine-Dinaric mountain populations described as subspecies of the typical

I. sibirica species [

55]. Although plastid markers (

Figure 4) did not discriminate

I. sibirica subspecies, the results of SSR analysis (

Figure 3) confirmed their differentiation. This is also in accordance with the presumption that

I. sibirica subsp.

erirrhiza might be a mountain ecotype [

46], which differs from the typical lowland subspecies

I. sibirica subsp.

sibirica [

55]. This is particularly interesting for further conservation of wild, especially endemic irises from that area. Namely,

I. sibirica subsp.

erirrhiza was found only in several localities in Bosnia and Herzegovina, Croatia, and Slovenia where it might be an endemic taxon [

46,

55]. The subclustering of

I. sibirica subsp.

erirrhiza samples in our research and an extra subcluster of typical

I. sibirica subsp.

sibirica (

Figure 3) additionally confirms this distinction of subspecies as ecotypes. Unfortunately, in our study we did not have a sample of the population of

I. sibirica subsp.

erirrhiza from Mt. Bjelolasica (Croatia), the supposed link between the subgenera

Limniris and

Iris in the territory of Southern Europe [

8]. Further research focused on broader ecotype samples of

I. sibirica sensu lato is needed to give a better insight into the phylogenetic structure within this complex taxon.

Regarding other representatives of the subgenus

Limniris in our study, we can comment on the specific position of the species

I. graminea, which separated in the distinct cluster in both trees (

Figure 3 and

Figure 4). Therefore, our results might support the hypothesis that the species

I. graminea is probably the most primitive member of the subgenus

Limniris on the Southern European territory [

8]. Besides this, our analysis of microsatellites (

Figure 3) might also confirm the opinion based on palynological observations, that the subgenus

Iris is more advanced than the subgenus

Limniris [

8,

56].

In closure, we can confirm that our results of the molecular study of Alpine-Dinaric taxa of the genus

Iris correspond well with their positions within the subgenera

Iris and

Limniris, and are in accordance with some other recent molecular researches of taxa of the genus

Iris [

41,

57]. Additionally, our results present the first molecular data on narrow endemic and near threatened species

I. adriatica and also support the separate taxonomic status of investigated ambiguous regional taxa (e.g.,

I. sibirica subsp.

erirrhiza,

I. x

croatica and

I. x

rotschildii).

—earlier data from the FCD;

—earlier data from the FCD;  —localities of collected specimens in our study); (b) habitat on the locality Brnjica-Pokrovnik; (c) habitat on the island of Cres.

—localities of collected specimens in our study); (b) habitat on the locality Brnjica-Pokrovnik; (c) habitat on the island of Cres.

—earlier data from the FCD;

—earlier data from the FCD;  —localities of collected specimens in our study); (b) habitat on the locality Brnjica-Pokrovnik; (c) habitat on the island of Cres.

—localities of collected specimens in our study); (b) habitat on the locality Brnjica-Pokrovnik; (c) habitat on the island of Cres.