Abstract

After its recent discovery in patients with serious pneumonia in Wuhan (China), the 2019 novel coronavirus (2019-nCoV), named also Severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome Coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2), has spread quickly. Unfortunately, no drug or vaccine for treating human this coronavirus infection is available yet. Numerous options for controlling or preventing emerging 2019-nCoV infections may be predicted, including vaccines, interferon therapies, and small-molecule drugs. However, new interventions are likely to require months to years to develop. In addition, most of the existing antiviral treatments frequently lead to the development of viral resistance combined with the problem of side effects, viral re-emergence, and viral dormancy. The pharmaceutical industry is progressively targeting phytochemical extracts, medicinal plants, and aromatic herbs with the aim of identifying lead compounds, focusing principally on appropriate alternative antiviral drugs. Spices, herbal medicines, essential oils (EOs), and distilled natural products provide a rich source of compounds for the discovery and production of novel antiviral drugs. The determination of the antiviral mechanisms of these natural products has revealed how they interfere with the viral life cycle, i.e., during viral entry, replication, assembly, or discharge, as well as virus-specific host targets. Presently, there are no appropriate or approved drugs against CoVs, but some potential natural treatments and cures have been proposed. Given the perseverance of the 2019-nCoV outbreak, this review paper will illustrate several of the potent antiviral chemical constituents extracted from medicinal and aromatic plants, natural products, and herbal medicines with recognized in vitro and in vivo effects, along with their structure–effect relationships. As this review shows, numerous potentially valuable aromatic herbs and phytochemicals are awaiting assessment and exploitation for therapeutic use against genetically and functionally different virus families, including coronaviruses.

1. Introduction

Viruses are responsible for several infections and diseases comprising cancer, while complex disorders such as Alzheimer’s illness and type 1 diabetes have also been linked to virus-related infections [1]. In addition, due to increased foreign travel and rapid urbanization, infectious outbreaks caused by emerging and re-emerging pathogens, including viruses, pose a serious danger to community health care, principally if antiviral treatment and protective vaccines are not available. Up to the present time, several viruses persist without potent immunization, and only limited virucidal molecules are approved for clinical use in humans [2].

In 1937, coronaviruses were identified from poultry and were considered extremely important pathogenic viruses in livestock, causing periodic cold or mild human digestive infections [3]. A new human coronavirus (CoV) became notably popular in spring 2003 because of an outbreak in South-East Asia and Canada [4].

At the time, the suspect virus was quickly recognized as the Severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome-Coronavirus (SARS-CoV) but did not bear a resemblance to the human CoVs. SARS-CoV worried the world because it sickened more than 7500 persons and killed more than 700 of them [5]. It was not until the SARS epidemic of 2002–2003 that research and investigation for particular anti-coronavirus vaccines or therapies started [6].

A novel coronavirus has caused severe mortality associated with a respiratory contagious disease. The virus is named Middle East Respiratory Syndrome Coronavirus (MERS-CoV). This novel MERS-CoV was first observed in different countries including Saudi Arabia [7]. A novel coronavirus with human-to-human contagion and causing a particularly serious illness, occurring in Wuhan, China, was confirmed towards the end of December 2019 [8]. The virus was named SARS-CoV-2 and the disease it causes was named Coronavirus Disease 2019 (abbreviated “COVID-19”).

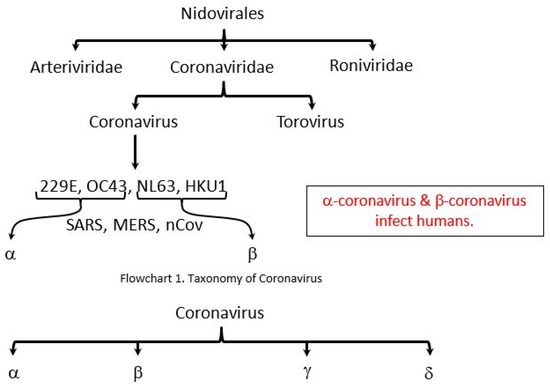

Early on, several of the patients at the epidemic center in Wuhan, Hubei Province (China), had some connection with a vast market of seafood and animals, implying the animal-to-person transmission. Afterward, an increasing number of patients apparently had no access to animal marketplaces, implying transmission from person to person [9]. The coronavirus group comprises numerous species (Figure 1) and induces respiratory tract and gastrointestinal infections in vertebrates; however, some CoVs such as SARS, MERS, and SARS-CoV-2 have been shown to be especially dangerous to humans [10]. Coronaviruses comprise an extensive collection of viruses, which commonly infect humans as well as numerous other mammalian species such as cattle, farm animals, household pets, and bats [11]. Infrequently, coronaviruses could infect humans from animals and subsequently expand among persons, as was observed for MERS-CoV, SARS-CoV, and now with SARS-CoV-2 [12].

Figure 1.

The taxonomy of the order Nidovirales. https://epomedicine.com/medical-students/coronavirus-disease-covid-2019/; (CSSE; FT research; Updated: 17 March 2020, 10:00 GMT). SARS, Severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome, MERS, Middle East Respiratory Syndrome Coronavirus, nCov, novel coronavirus. α: Alpha; β: Beta; γ: Gamma; δ: Delta.

There are no effective or approved therapies for CoV diseases, and protective vaccines are still being investigated. Therefore, it is necessary to discover potent antivirals for protection from and management of CoV infection in humans [13]. The novelty of the 2019 novel coronavirus (2019-nCoV) means that there are numerous uncertainties surrounding its behavior; consequently, it is too early to conclude whether herbal and medicinal plants, spices, or isolated compounds and molecules could be used as prophylactic/preventive drugs or as appropriate therapeutic compounds against COVID-19. Nevertheless, due to the high similarity of SARS-CoV-2 with the previously reported MERS-CoV and SARS-CoV viruses, previous research articles on phytomedicine and herbal compounds, which have been demonstrated to have anti-coronavirus properties, may be an appreciated guide to searching and discovering antiviral phytochemical extracts which may be effective against SARS-CoV-2 virus [14,15,16,17,18,19,20,21,22,23,24,25,26,27,28,29,30,31,32,33,34].

Published patent applications and academic investigations on the most relevant compounds and methods for the treatment of coronaviruses are reviewed, focusing on those strategies that attack one particular phase of the development cycle of coronaviruses, because they have greater potential as lead structural templates for further development.

In this review article, we summarize the antiviral properties from numerous phytochemical extracts, aromatic herbs, and medicinal plants against different CoV. These medicinal plants and phytochemical extracts offer an important source for innovative and effective antiviral drug discovery, allowing inexpensive and relatively safe drug development.

2. COVID-19 Is Now Officially a Pandemic

The coronavirus 2019-nCoV has infected numerous people in China and spread to other regions in a short period. On 30 January, 2020, the World Health Organization (WHO) confirmed that the epidemic of 2019-nCoV is a global health crisis and delivered initial suggestions [34,35]. On 2 February 2020, and according to China’s National Health Commission’s report, 14,488 clinical infections were found in China, comprising 304 deaths.

As we write this and according to the WHO, COVID-19 threatens 200 nations and regions across the planet and two multinational transports: the luxury ship Diamond Princess harbored in Yokohama, Japan, and the cruise ship MS Zaandam from Holland America [36]. The COVID-19 viral infection resulted in the deaths of more than 182,000 individuals and is now officially considered to be a pandemic. This viral infection is considered to be the first pandemic due to a coronavirus. In addition, it is the first time the WHO has called an infectious outbreak a pandemic since the H1N1 “swine flu” in 2009. Furthermore, different American, Asian, and European countries are now each recording more than 800,000 cases of COVID-19, caused by the 2019-nCoV that has infected more than 5,000,000 people worldwide. In the past three weeks, the number of affected countries has tripled, and the number of human cases of COVID-19 outside China has increased 15-fold. The WHO is profoundly worried, both with the disturbing degrees of seriousness of the infection and the dissemination of the disease and with the disturbing degrees of indecision and complacency of many world leaders in reaction to the epidemic. Therefore, COVID-19 is now recognized as a pandemic. In the previous pandemic, according to the WHO, the H1N1 influenza virus infected more than 18,000 people in more than 214 territories and nations.

3. An Overview of COVID-19

The entire medical picture of COVID-19 is not completely known. Recorded illnesses have oscillated from very minor (even those with no clinical symptoms) to serious, including deadly infection. Although clinical reports have shown that most infections with COVID-19 are mild to date, a recent investigation [37] from China indicates that severe illness occurs in 16% of cases. Older individuals and different age groups with serious chronic medical conditions such as respiratory disease, cardiovascular disease, and diabetes tend to be at higher risk of contracting extreme COVID-19 [38,39,40]. As individuals, practicing prevention measures and good hygiene as well as applying actions of social distancing, including avoiding crowded places, remain to be very essential [34,41].

The pandemic is persisting, and discovering innovative prevention and medicinal medicines or vaccinations as early as possible is vital and necessary. In addition, effective measures for early identification, exclusion, and diagnosis of individual patients, as well as reducing exposure and dissemination by social contact and activities must be implemented.

Although successful vaccinations and antiviral medicines are the most potent means of combating or avoiding virus diseases and contaminations, there are no cures yet for 2019-nCoV infection. The creation and production of such medications may take several months or years, thereby indicating the need for finding alternative rapid treatment or control strategies.

7. Future Prospects

It is necessary to continue the development of efficacious antiviral chemotherapeutics that are cost-effective and with minimal side effects and which can also be used in combination with other drugs to improve the therapy of coronavirus-infected subjects. As protective vaccines and active antiviral drugs are not available for the treatment of several viruses, eliminating these viral infections seems hard and problematic. However, natural products serve as a tremendous source of biodiversity for developing innovative antivirals, with new structure–activity relationships, and potent medical and therapeutic approaches against viral infections.

A main problem surrounding antiviral drugs targeting specific viral proteins or genes is the capacity of a virus to rapidly mutate during replication, as observed for HIV and HSV [106], oseltamivir-resistant influenza viruses [107], and acyclovir- and nucleoside/nucleotide analog-resistant hepatitis B viruses [108]. There are several aspects that should be taken into account when assessing the antiviral activity of preparations of medicinal herbs, such as the extraction techniques used, since the highest level of antiviral activity is attained with acetone extracts or methanol fractions [109]. It is therefore appropriate, at the outset of a prospective study on aromatic herbal medicines, to identify the correct methodology for the preparation of the extracts, the parts of the plants to be used, the suitable season(s) for the collection of the materials, and the details of the application modality [110].

Although most research studies in this area are in their initial stages, additional research on the identification of active substances, the description of underlying mechanisms, as well as the analysis of efficiency and probable in vivo applications is recommended in order to assist the exploration of potent antiviral chemotherapeutics. Additional research should also investigate the possibility of combining these treatments with other natural ingredients or with standard medicines, as a multiple-target solution may help diminish the infection potential of drug-resistant virus strains. We trust that natural remedies, such as aromatic herbs, essential oils derived from medicinal plants, and pure oil compounds, will continue to play an important role and participate in the development and advancement of anti-coronavirus drugs.

8. Conclusions

Many viral infections are still lethal and/or are not yet treatable, even though some can be kept under control with life-prolonging agents, which, however, are expensive and outside the reach of most people. Thus, the discovery and development of safe, effective, and low-cost antiviral molecules is among the top universal urgencies of drug research.

Therefore, scientists and researchers from divergent medical fields are studying aromatic herbs and ethnomedicinal plants, with an eye to their applicability as antiviral drugs. Widespread research on ethnopharmacology and phytomedicine for the last 50 years resulted in the discovery of antivirals from natural products. Various traditional aromatic herbs and medicinal plants have been described as having strong and potent antiviral properties. Volatile oils, aqueous and organic extracts have, in general, demonstrated similar successful properties.

Considering the significant number of traditional medicinal plants that have provided good outcomes, it would seem reasonable to assume that these products contain different types of antiviral compounds. A characterization of secondary metabolites will reveal further health benefits. Therefore, the common usage of many traditional medicines for the prevention of viral infections is warranted. Eventually, the discovery and development of new antiviral agents from medicinal plants and herbs to control the threats presented by certain pathogenic viruses, such as the 2019-nCoV, is critical.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, M.N.B.; investigation, M.N.B.; writing—original draft preparation, M.N.B. and W.N.S.; writing—review and editing, M.N.B. and W.N.S. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Abbreviations

ACE2: Angiotensin-Converting Enzyme 2; BCV: Bovine Coronavirus; CDC: US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention; CoV: Coronavirus; COVID-19: Coronavirus Disease 2019; EC50: half maximal effective concentration; EOs: Essential Oils; H1N1: Hemagglutinin Type 1 and Neuraminidase Type 1; HIV: Human Immunodeficiency Virus; HSV: Herpes Simplex Virus; IBV: Infectious Bronchitis Virus; IC50: Median Inhibitory Concentration; MERS-CoV: Middle East Respiratory Syndrome Coronavirus; nsP13: non-structural protein 13; RNA: RiboNucleic Acid; RSV: Respiratory Syncytial Virus; SARS-CoV: Severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome-Coronavirus; WHO: World Health Organization.

References

- Vehik, K.; Dabelea, D. The changing epidemiology of type 1 diabetes: Why is it going through the roof? Diab. Metabol. Res. Rev. 2011, 27, 3–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Clercq, E.; Li, G. Approved antiviral drugs over the past 50 years. Clin. Microbiol. Rev. 2016, 29, 695–747. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, W.; Lin, X.D.; Guo, W.P.; Zhou, R.H.; Wang, M.R.; Wang, C.Q.; Holmes, E.C. Discovery, diversity and evolution of novel coronaviruses sampled from rodents in China. Virology 2015, 474, 19–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Drosten, C.; Günther, S.; Preiser, W.; Van Der Werf, S.; Brodt, H.R.; Becker, S.; Berger, A. Identification of a novel coronavirus in patients with severe acute respiratory syndrome. N. Engl. J. Med. 2003, 348, 1967–1976. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liang, G.; Chen, Q.; Xu, J.; Liu, Y.; Lim, W.; Peiris, J.S.M.; Di, B. Laboratory diagnosis of four recent sporadic cases of community-acquired SARS, Guangdong Province, China. Emerg. Infect. Dis. 2004, 10, 1774. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hilgenfeld, R.; Peiris, M. From SARS to MERS: 10 years of research on highly pathogenic human coronaviruses. Antivir. Res. 2013, 100, 286–295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zaki, A.M.; Van Boheemen, S.; Bestebroer, T.M.; Osterhaus, A.D.; Fouchier, R.A. Isolation of a novel coronavirus from a man with pneumonia in Saudi Arabia. N. Engl. J. Med. 2012, 367, 1814–1820. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Paraskevis, D.; Kostaki, E.G.; Magiorkinis, G.; Panayiotakopoulos, G.; Sourvinos, G.; Tsiodras, S. Full-genome evolutionary analysis of the novel corona virus (2019-nCoV) rejects the hypothesis of emergence as a result of a recent recombination event. Infect. Genet. Evol. 2020, 79, 104212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Roosa, K.; Lee, Y.; Luo, R.; Kirpich, A.; Rothenberg, R.; Hyman, J.M.; Chowell, G. Real-time forecasts of the COVID-19 epidemic in China from February 5 to 24 February 2020. Infect. Dis. Model. 2020, 5, 256–263. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Guo, Y.R.; Cao, Q.D.; Hong, Z.S.; Tan, Y.Y.; Chen, S.D.; Jin, H.J.; Yan, Y. The origin, transmission and clinical therapies on coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) outbreak–an update on the status. Milit. Med. Res. 2020, 7, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, B.; Ge, X.; Wang, L.F.; Shi, Z. Bat origin of human coronaviruses. Virol. J. 2015, 12, 221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yang, Y.; Peng, F.; Wang, R.; Guan, K.; Jiang, T.; Xu, G.; Chang, C. The deadly coronaviruses: The 2003 SARS pandemic and the 2020 novel coronavirus epidemic in China. J. Autoimmun. 2020, 109, 102434. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhou, Y.; Hou, Y.; Shen, J.; Huang, Y.; Martin, W.; Cheng, F. Network-based drug repurposing for novel coronavirus 2019-nCoV/SARS-CoV-2. Cell. Discov. 2020, 6, 1–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, F.R.; Yen, C.T.; Ei-Shazly, M.; Lin, W.H.; Yen, M.H.; Lin, K.H.; Wu, Y.C. Anti-human coronavirus (anti-HCoV) triterpenoids from the leaves of Euphorbia neriifolia. Nat. Prod Comm. 2012, 7, 1934578X1200701103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, F.; Chan, K.H.; Jiang, Y.; Kao, R.Y.T.; Lu, H.T.; Fan, K.W.; Guan, Y. In vitro susceptibility of 10 clinical isolates of SARS coronavirus to selected antiviral compounds. J. Clin. Virol. 2004, 31, 69–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, Z.; Nakamura, T. Statistical evidence for the usefulness of Chinese medicine in the treatment of SARS. Phytother. Res. 2004, 18, 592–594. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

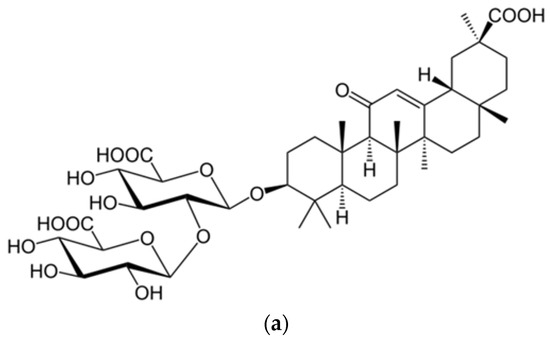

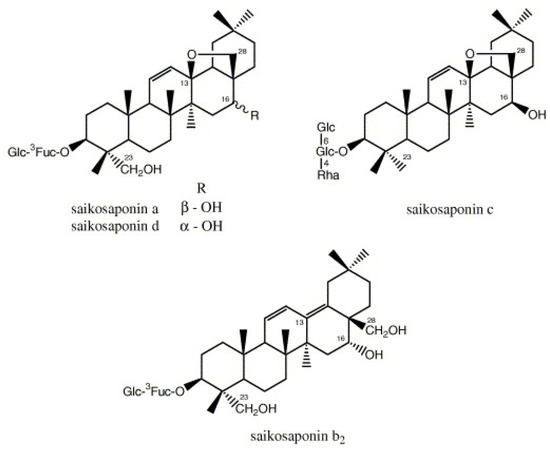

- Cheng, P.W.; Ng, L.T.; Chiang, L.C.; Lin, C.C. Antiviral effects of saikosaponins on human coronavirus 229E in vitro. Clin. Experim. Pharmacol. Physiol. 2006, 33, 612–616. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoever, G.; Baltina, L.; Michaelis, M.; Kondratenko, R.; Baltina, L.; Tolstikov, G.A.; Cinatl, J. Antiviral Activity of Glycyrrhizic Acid Derivatives against SARS− Coronavirus. J. Med. Chem. 2005, 48, 1256–1259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jassim, S.A.A.; Naji, M.A. Novel antiviral agents: A medicinal plant perspective. J. Appl. Microbiol. 2003, 95, 412–427. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, H.Y.; Shin, H.S.; Park, H.; Kim, Y.C.; Yun, Y.G.; Park, S.; Kim, K. In vitro inhibition of coronavirus replications by the traditionally used medicinal herbal extracts, Cimicifuga rhizoma, Meliae cortex, Coptidis rhizoma, and Phellodendron cortex. J. Clin. Virol. 2008, 41, 122–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, H.Y.; Eo, E.Y.; Park, H.; Kim, Y.C.; Park, S.; Shin, H.J.; Kim, K. Medicinal herbal extracts of Sophorae radix, Acanthopanacis cortex, Sanguisorbae radix and Torilis fructus inhibit coronavirus replication in vitro. Antivir. Therap. 2010, 15, 697–709. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kim, D.E.; Min, J.S.; Jang, M.S.; Lee, J.Y.; Shin, Y.S.; Park, C.M.; Kwon, S. Natural Bis-Benzylisoquinoline Alkaloids-Tetrandrine, Fangchinoline, and Cepharanthine, Inhibit Human Coronavirus OC43 Infection of MRC-5 Human Lung Cells. Biomolecules 2019, 9, 696. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, S.Y.; Chen, C.; Zhang, H.Q.; Guo, H.Y.; Wang, H.; Wang, L.; Li, R.S. Identification of natural compounds with antiviral activities against SARS-associated coronavirus. Antivir. Res. 2005, 67, 18–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

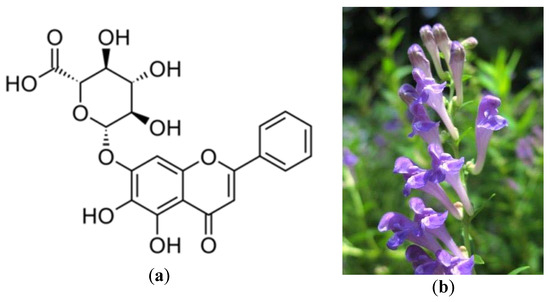

- Li, B.Q.; Fu, T.; Dongyan, Y.; Mikovits, J.A.; Ruscetti, F.W.; Wang, J.M. Flavonoid baicalin inhibits HIV-1 infection at the level of viral entry. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 2000, 276, 534–538. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, X.Q.; Song, Y.N.; Wang, S.J.; Rahman, K.; Zhu, J.Y.; Zhang, H. Saikosaponins: A review of pharmacological effects. J. Asian Nat. Prod. Res. 2018, 20, 399–411. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, C.W.; Tsai, F.J.; Tsai, C.H.; Lai, C.C.; Wan, L.; Ho, T.Y.; Chao, P.D.L. Anti-SARS coronavirus 3C-like protease effects of Isatis indigotica root and plant-derived phenolic compounds. Antivir. Res. 2005, 68, 36–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, L.T.; Hsu, W.C.; Lin, C.C. Antiviral natural products and herbal medicines. J. Trad. Complement. Med. 2014, 4, 24–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, X.; Zhang, M.; He, L.; Li, Y. Chinese herbs combined with Western medicine for severe acute respiratory syndrome (SARS). Cochr. Database. Syst. Rev. 2012, 10, 1–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McCutcheon, A.R.; Roberts, T.E.; Gibbons, E.; Ellis, S.M.; Babiuk, L.A.; Hancock, R.E.W.; Towers, G.H.N. Antiviral screening of British Columbian medicinal plants. J. Ethnopharmacol. 1995, 49, 101–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsai, Y.C.; Lee, C.L.; Yen, H.R.; Chang, Y.S.; Lin, Y.P.; Huang, S.H.; Lin, C.W. Antiviral Action of Tryptanthrin Isolated from Strobilanthes cusia Leaf against Human Coronavirus NL63. Biomolecules 2020, 10, 366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, C.Y.; Jan, J.T.; Ma, S.H.; Kuo, C.J.; Juan, H.F.; Cheng, Y.S.E.; Liang, F.S. Small molecules targeting severe acute respiratory syndrome human coronavirus. Proc. Nat. Acad. Sci. USA 2004, 101, 10012–10017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yang, Y.; Islam, M.S.; Wang, J.; Li, Y.; Chen, X. Traditional Chinese medicine in the treatment of patients infected with 2019-new coronavirus (SARS-CoV-2): A review and perspective. Int. J. Biol. Sci. 2020, 16, 1708. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Boukhatem, M.N. Effective Antiviral Activity of Essential Oils and their Characteristics Terpenes against Coronaviruses: An Update. J. Pharmacol. Clin. Toxicol. 2020, 8, 1138. [Google Scholar]

- Boukhatem, M.N. Novel Coronavirus Disease 2019 (COVID-19) Outbreak in Algeria: A New Challenge for Prevention. J. Community Med. Health Care 2020, 5, 1035. [Google Scholar]

- World Health Organization (WHO). Statement on the Second Meeting of the International Health Regulations Emergency Committee Regarding the Outbreak of Novel Coronavirus (2019-nCoV). Available online: www.who.int/news-room/detail/30-01-2020-statement-on-the-second-meeting-of-the-international-health-regulations-(2005)-emergency-committee-regarding-the-outbreak-of-novel-coronavirus-(2019-ncov) (accessed on 2 February 2020).

- COVID-19 Coronavirus Pandemic. Available online: www.worldometers.info/coronavirus/ (accessed on 23 May 2020).

- Guan, W.J.; Ni, Z.Y.; Hu, Y.; Liang, W.H.; Ou, C.Q.; He, J.X.; Du, B. Clinical characteristics of coronavirus disease 2019 in China. N. Engl. J. Med. 2020, 382, 1708–1720. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zheng, Y.Y.; Ma, Y.T.; Zhang, J.Y.; Xie, X. COVID-19 and the cardiovascular system. Nat. Rev. Cardiol. 2020, 17, 259–260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- The Novel Coronavirus Pneumonia Emergency Response Epidemiology Team. The epidemiological characteristics of an outbreak of 2019 novel coronavirus diseases (COVID-19)—China, 2020. China CDC Wkly. 2020, 2, 113–122. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, Y.; Yan, L.M.; Wan, L.; Xiang, T.X.; Le, A.; Liu, J.M.; Zhang, W. Viral dynamics in mild and severe cases of COVID-19. Lancet. Infect. Dis. 2020, 20, 656–657. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dalton, C.; Corbett, S.; Katelaris, A. Pre-emptive low cost social distancing and enhanced hygiene implemented before local COVID-19 transmission could decrease the number and severity of cases. Med. J. Aust. 2020, 212, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- CDC SARS Response Timeline. Available online: www.cdc.gov/about/history/sars/timeline.htm (accessed on 18 March 2020).

- Yang, Q.Y.; Tian, X.Y.; Fang, W.S. Bioactive coumarins from Boenninghausenia sessilicarpa. J. Asian Nat. Prod. Res. 2007, 9, 59–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wen, C.C.; Shyur, L.F.; Jan, J.T.; Liang, P.H.; Kuo, C.J.; Arulselvan, P.; Yang, N.S. Traditional Chinese medicine herbal extracts of Cibotium barometz, Gentiana scabra, Dioscorea batatas, Cassia tora, and Taxillus chinensis inhibit SARS-CoV replication. J. Tradit. Complement. Med. 2011, 1, 41–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thabti, I.; Albert, Q.; Philippot, S.; Dupire, F.; Westerhuis, B.; Fontanay, S.; Varbanov, M. Advances on Antiviral Activity of Morus spp. Plant Extracts: Human Coronavirus and Virus-Related Respiratory Tract Infections in the Spotlight. Molecules 2020, 25, 1876. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shen, Y.C.; Wang, L.T.; Khalil, A.T.; Chiang, L.C.; Cheng, P.W. Bioactive pyranoxanthones from the roots of Calophyllum blancoi. Chem. Pharm. Bull. 2005, 53, 244–247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Michaelis, M.; Doerr, H.W.; Cinatl, J., Jr. Investigation of the influence of EPs® 7630, a herbal drug preparation from Pelargonium sidoides, on replication of a broad panel of respiratory viruses. Phytomedicine 2011, 18, 384–386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yi, L.; Li, Z.; Yuan, K.; Qu, X.; Chen, J.; Wang, G.; Chen, L. Small molecules blocking the entry of severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus into host cells. J. Virol. 2004, 78, 11334–11339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Loizzo, M.R.; Saab, A.M.; Tundis, R.; Statti, G.A.; Menichini, F.; Lampronti, I.; Doerr, H.W. Phytochemical analysis and in vitro antiviral activities of the essential oils of seven Lebanon species. Chem. Biodiv. 2008, 5, 461–470. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhuang, M.; Jiang, H.; Suzuki, Y.; Li, X.; Xiao, P.; Tanaka, T.; Qin, C. Procyanidins and butanol extract of Cinnamomi Cortex inhibit SARS-CoV infection. Antivir. Res. 2009, 82, 73–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

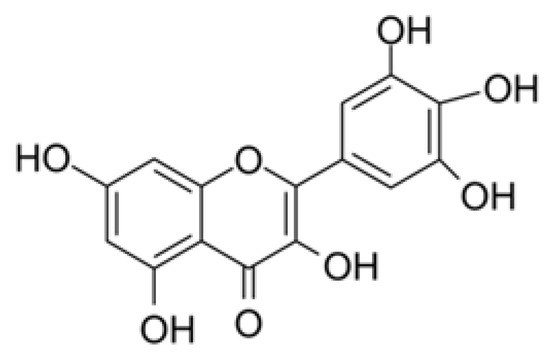

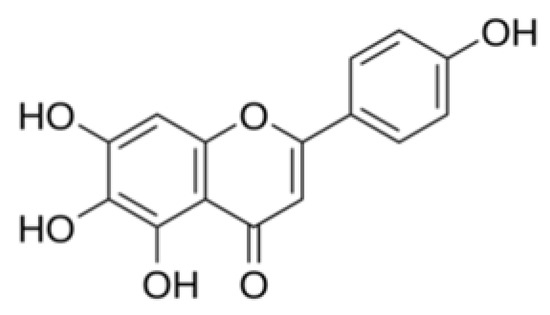

- Yu, M.S.; Lee, J.; Lee, J.M.; Kim, Y.; Chin, Y.W.; Jee, J.G.; Jeong, Y.J. Identification of marketing and scutellarein as novel chemical inhibitors of the SARS coronavirus helicase, nsP13. Bioorg. Med. Chem. Lett. 2012, 22, 4049–4054. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, W.; Su, X.; Gong, S.; Qin, Y.; Liu, W.; Li, J.; Xu, Q. Anti-SARS coronavirus 3C-like protease effects of Rheum palmatum L. extracts. Biosci. Trends. 2009, 3, 124–126. [Google Scholar]

- Lau, K.M.; Lee, K.M.; Koon, C.M.; Cheung, C.S.F.; Lau, C.P.; Ho, H.M.; Tsui, S.K.W. Immunomodulatory and anti-SARS activities of Houttuynia cordata. J. Ethnopharmacol. 2008, 118, 79–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, J.Y.; Kim, J.H.; Kim, Y.M.; Jeong, H.J.; Kim, D.W.; Park, K.H.; Ryu, Y.B. Tanshinones as selective and slow-binding inhibitors for SARS-CoV cysteine proteases. Bioorg. Med. Chem. 2012, 20, 5928–5935. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

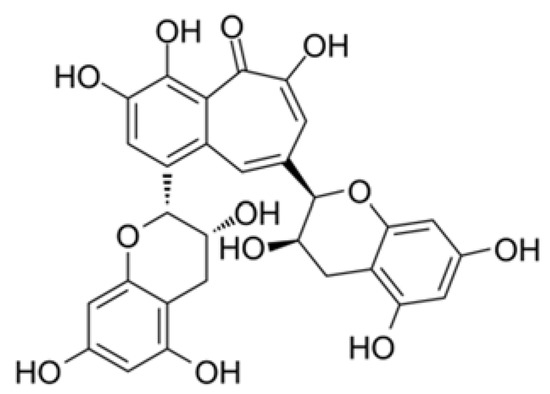

- Ryu, Y.B.; Jeong, H.J.; Kim, J.H.; Kim, Y.M.; Park, J.Y.; Kim, D.; Rho, M.C. Biflavonoids from Torreya nucifera displaying SARS-CoV 3CLpro inhibition. Bioorg. Med. Chem. 2010, 18, 7940–7947. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Park, J.Y.; Yuk, H.J.; Ryu, H.W.; Lim, S.H.; Kim, K.S.; Park, K.H.; Lee, W.S. Evaluation of polyphenols from Broussonetia papyrifera as coronavirus protease inhibitors. J. Enzym. Inhib. Med. Chem. 2017, 32, 504–512. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kim, D.W.; Seo, K.H.; Curtis-Long, M.J.; Oh, K.Y.; Oh, J.W.; Cho, J.K.; Park, K.H. Phenolic phytochemical displaying SARS-CoV papain-like protease inhibition from the seeds of Psoralea corylifolia. J. Enzym. Inhib. Med. Chem. 2014, 29, 59–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Weng, J.R.; Lin, C.S.; Lai, H.C.; Lin, Y.P.; Wang, C.Y.; Tsai, Y.C.; Lin, C.W. Antiviral activity of Sambucus FormosanaNakai ethanol extract and related phenolic acid constituents against human coronavirus NL63. Virus. Res. 2019, 273, 197767. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- O’Keefe, B.R.; Giomarelli, B.; Barnard, D.L.; Shenoy, S.R.; Chan, P.K.; McMahon, J.B.; McCray, P.B. Broad-spectrum in vitro activity and in vivo efficacy of the antiviral protein griffithsin against emerging viruses of the family Coronaviridae. J. Virol. 2010, 84, 2511–2521. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pyrrosia Lingua. Available online: https://www.flickr.com/photos/harumkoh/17118611672/ (accessed on 16 June 2020).

- Artemisia annua. Available online: https://www.flickr.com/photos/47108884@N07/4738072658 (accessed on 16 June 2020).

- Cinatl, J.; Morgenstern, B.; Bauer, G.; Chandra, P.; Rabenau, H.; Doerr, H.W. Glycyrrhizin, an active component of liquorice roots, and replication of SARS-associated coronavirus. Lancet 2003, 361, 2045–2046. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Graebin, C.S. The pharmacological activities of glycyrrhizinic acid (“glycyrrhizin”) and glycyrrhetinic acid. In Sweeteners, 1st ed.; Mérillon, J.M., Ramawat, K.G., Eds.; Springer International Publishing: Gewerbestrasse, Switzerland, 2018; pp. 245–261. [Google Scholar]

- Glycyrrhiza Glabra Linn. Available online: https://www.flickr.com/photos/valdelobos/4657830744 (accessed on 16 June 2020).

- Kitamura, K.; Honda, M.; Yoshizaki, H.; Yamamoto, S.; Nakane, H.; Fukushima, M.; Tokunaga, T. Baicalin, an inhibitor of HIV-1 production in vitro. Antivir. Res. 1998, 37, 131–140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scutellaria Baicalensis. Available online: https://www.flickr.com/photos/tanaka_juuyoh/2718717267 (accessed on 16 June 2020).

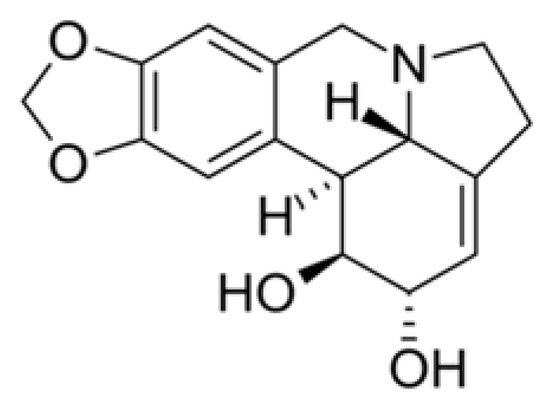

- Renard-Nozaki, J.; Kim, T.; Imakura, Y.; Kihara, M.; Kobayashi, S. Effect of alkaloids isolated from Amaryllidaceae on herpes simplex virus. Res. Virol. 1989, 140, 115–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ieven, M.; Vlietinick, A.J.; Berghe, D.V.; Totte, J.; Dommisse, R.; Esmans, E.; Alderweireldt, F. Plant antiviral agents. III. Isolation of alkaloids from Clivia miniata Regel (Amaryl-lidaceae). J. Nat. Prod. 1982, 45, 564–573. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Çitoğlu, G.S.; Acıkara, Ö.B.; Yılmaz, B.S.; Özbek, H. Evaluation of analgesic, anti-inflammatory and hepatoprotective effects of lycorine from Sternbergia fisheriana (Herbert) Rupr. Fitoterapia 2012, 83, 81–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lonicera japonica ‘Japanese Honeysuckle’. Available online: https://www.flickr.com/photos/89906643@N06/9892035994/ (accessed on 27 April 2020).

- Ginseng (Panax ginseng). Available online: https://www.flickr.com/photos/eekim/4145898809 (accessed on 16 June 2020).

- Wild Rose-Rosa nutkana. Available online: https://www.flickr.com/photos/nordique/7188593733 (accessed on 22 April 2020).

- Potentilla arguta. Available online: https://www.flickr.com/photos/glaciernps/23703091762 (accessed on 16 June 2020).

- Red elderberry. Available online: https://www.flickr.com/photos/brewbooks/217464248 (accessed on 16 June 2020).

- Tsuchiya, Y.; Shimizu, M.; Hiyama, Y.; Itoh, K.; Hashimoto, Y.; Nakayama, M.; Morita, N. Antiviral activity of natural occurring flavonoids in vitro. Chem. Pharmac. Bull. 1985, 33, 3881–3886. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Clark, K.J.; Grant, P.G.; Sarr, A.B.; Belakere, J.R.; Swaggerty, C.L.; Phillips, T.D.; Woode, G.N. An in vitro study of theaflavins extracted from black tea to neutralize bovine rotavirus and bovine coronavirus infections. Veterin. Microbiol. 1998, 63, 147–157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, G.Y.; Liu, Z.; Seril, D.N.; Liao, J.; Ding, W.; Kim, S.; Yang, C.S. Black tea constituents, theaflavins, inhibit 4-(methylnitrosamino)-1-(3-pyridyl)-1-butanone (NNK)-induced lung tumorigenesis in A/J mice. Carcinogenesis 1997, 18, 2361–2365. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed][Green Version]

- Parthasarathy, K.; Ng, L.; Lin, X.; Liu, D.X.; Pervushin, K.; Gong, X.; Torres, J. Structural flexibility of the pentameric SARS coronavirus envelope protein ion channel. Biophys. J. 2008, 95, L39–L41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Notka, F.; Meier, G.; Wagner, R. Concerted inhibitory activities of Phyllanthus amarus on HIV replication in vitro and ex vivo. Antivir. Res. 2004, 64, 93–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ganesan, S.; Faris, A.N.; Comstock, A.T.; Wang, Q.; Nanua, S.; Hershenson, M.B.; Sajjan, U.S. Quercetin inhibits rhinovirus replication in vitro and in vivo. Antivir. Res. 2012, 94, 258–271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reichling, J.; Koch, C.; Stahl-Biskup, E.; Sojka, C.; Schnitzler, P. Virucidal activity of a β-triketone-rich essential oil of Leptospermum scoparium (manuka oil) against HSV-1 and HSV-2 in cell culture. Planta Med. 2005, 71, 1123–1127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schnitzler, P.; Koch, C.; Reichling, J. Susceptibility of drug-resistant clinical herpes simplex virus type 1 strains to essential oils of ginger, thyme, hyssop, and sandalwood. Antimicrob. Agents. Chemother. 2007, 51, 1859–1862. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jang, J.H.; Lee, S.H.; Jung, K.; Yoo, H.; Park, G. Inhibitory Effects of Myricetin on Lipo- polysaccharide-Induced Neuroinflammation. Brain Sci. 2020, 10, 32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, Y.; Ren, N.; Li, S.; Chen, M.; Pu, P. Novel anti-obesity effect of scutellarein and potential underlying mechanism of actions. Biomed. Pharmacother. 2019, 117, 109042. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Woad Root (Ban Lan Gen), Isatis Indigotica-Radix Isatidis. Available online: https://www.flickr.com/photos/nhq9801/9216111022/in/photostream/ (accessed on 16 June 2020).

- Hughes, K. A Plant a Day: Japanese Nutmeg-Yew (Torreya nucifera, T. spp.). Available online: https://www.flickr.com/photos/138014579@N08/35706702426 (accessed on 16 June 2020).

- Houttuynia cordata. Available online: https://www.flickr.com/photos/dakiny/34949957600 (accessed on 16 June 2020).

- Zhu, H.; Zhang, Y.; Ye, G.; Li, Z.; Zhou, P.; Huang, C. In vivo and in vitro antiviral activities of calycosin-7-O-beta-D-glucopyranoside against coxsackie virus B3. Biol. Pharm. Bull. 2009, 32, 68–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, C.N.; Lin, C.P.; Huang, K.K.; Chen, W.C.; Hsieh, H.P.; Liang, P.H.; Hsu, J.T.A. Inhibition of SARS-CoV 3C-like protease activity by theaflavin-3, 3′-digallate (TF3). Evid Based Complement Alternat Med. 2005, 2, 209–215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yuan, S.L.; Piao, X.S.; Li, D.F.; Kim, S.W.; Lee, H.S.; Guo, P.F. Effects of dietary Astragalus polysaccharide on growth performance and immune function in weaned pigs. Anim. Sci. 2006, 82, 501–507. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wen, C.C.; Kuo, Y.H.; Jan, J.T.; Liang, P.H.; Wang, S.Y.; Liu, H.G.; Hou, C.C. Specific plant terpenoids and lignoids possess potent antiviral activities against severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus. J. Med. Chem. 2007, 50, 4087–4095. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ho, T.Y.; Wu, S.L.; Chen, J.C.; Li, C.C.; Hsiang, C.Y. Emodin blocks the SARS coronavirus spike protein and angiotensin-converting enzyme 2 interaction. Antivir. Res. 2007, 74, 92–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, V.; Tan, K.P.; Wang, Y.M.; Lin, S.W.; Liang, P.H. Identification, synthesis and evaluation of SARS-CoV and MERS-CoV 3C-like protease inhibitors. Bioorg. Med. Chem. 2016, 24, 3035–3042. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Speranza, L.; Franceschelli, S.; Pesce, M.; Reale, M.; Menghini, L.; Vinciguerra, I.; Grilli, A. Antiinflammatory effects in THP-1 cells treated with verbascoside. Phytother. Res. 2010, 24, 1398–1404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chu, X.; Ci, X.; Wei, M.; Yang, X.; Cao, Q.; Guan, M.; Deng, X. Licochalcone a inhibits lipopolysaccharide-induced inflammatory response in vitro and in vivo. J. Agr. Food. Chem. 2012, 60, 3947–3954. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, Q.; Chen, L.; Gao, M.; Jiang, W.; Shao, F.; Li, J.; Yu, B. Ruscogenin inhibits lipopolysaccharide-induced acute lung injury in mice: Involvement of tissue factor, inducible NO synthase and nuclear factor (NF)-κB. Int. Immunopharmacol. 2012, 12, 88–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, C.; Zuckerman, D.M.; Brantley, S.; Sharpe, M.; Childress, K.; Hoiczyk, E.; Pendleton, A.R. Sambucus nigra extracts inhibit infectious bronchitis virus at an early point during replication. BMC Veter. Res. 2014, 10, 24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, H.; Muhammad, I.; Zhang, Y.; Ren, Y.; Zhang, R.; Huang, X.; Abbas, G. Antiviral Activity Against Infectious Bronchitis Virus and Bioactive Components of Hypericum perforatum L. Front. Pharmacol. 2019, 10, 1272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shen, L.; Niu, J.; Wang, C.; Huang, B.; Wang, W.; Zhu, N.; Tan, W. High-throughput screening and identification of potent broad-spectrum inhibitors of coronaviruses. J. Virol. 2019, 93, e00023-19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Maxmen, A. More than 80 clinical trials launch to test coronavirus treatments. Nature 2020, 578, 347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vellingiri, B.; Jayaramayya, K.; Iyer, M.; Narayanasamy, A.; Govindasamy, V.; Giridharan, B.; Rajagopalan, K. COVID-19: A promising cure for the global panic. Sci. Total. Environ. 2020, 138277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, H.; Tang, Q.L.; Shang, Y.X.; Liang, S.B.; Yang, M.; Robinson, N.; Liu, J.P. Can Chinese medicine be used for prevention of corona virus disease 2019 (COVID-19)? A review of historical classics, research evidence and current prevention programs. Chinese. J. Integr. Med. 2020, 26, 1–8. [Google Scholar]

- Astragalus Membranaceus. Available online: https://www.flickr.com/photos/jennyhsu47/4539175733 (accessed on 16 June 2020).

- Rhizoma Atractylodes macrocephalae. Available online: https://www.flickr.com/photos/jennyhsu47/4539818092 (accessed on 16 June 2020).

- Wan, S.; Xiang, Y.; Fang, W.; Zheng, Y.; Li, B.; Hu, Y.; Huang, X. Clinical Features and Treatment of COVID-19 Patients in Northeast Chongqing. J. Med. Virol. 2020, 7, 797–806. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McMahon, M.A.; Siliciano, J.D.; Lai, J.; Liu, J.O.; Stivers, J.T.; Siliciano, R.F.; Kohli, R.M. The antiherpetic drug acyclovir inhibits HIV replication and selects the V75I reverse transcriptase multidrug resistance mutation. J. Biol. Chem. 2008, 283, 31289–31293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Collins, P.J.; Haire, L.F.; Lin, Y.P.; Liu, J.; Russell, R.J.; Walker, P.A.; Gamblin, S.J. Crystal structures of oseltamivir-resistant influenza virus neuraminidase mutants. Nature 2008, 453, 1258–1261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Delaney, W.E., IV; Borroto-Esoda, K. Therapy of chronic hepatitis B: Trends and developments. Curr. Opinion. Pharmacol. 2008, 8, 532–540. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Asres, K.; Bucar, F.; Kartnig, T.; Witvrouw, M.; Pannecouque, C.; De Clercq, E. Antiviral activity against human immunodeficiency virus type 1 (HIV-1) and type 2 (HIV-2) of ethnobotanically selected Ethiopian medicinal plants. Phytother. Res. 2001, 15, 62–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hudson, J.B. Antiviral Compounds from Plants; CRC Press: Boston, MA, USA, 1990. [Google Scholar]

© 2020 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).