The Analysis of the Editing Defects in the dyw2 Mutant Provides New Clues for the Prediction of RNA Targets of Arabidopsis E+-Class PPR Proteins

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Results

2.1. The Editing Defects in the dyw2 Mutant Define 2 Classes of RNA Editing Targets

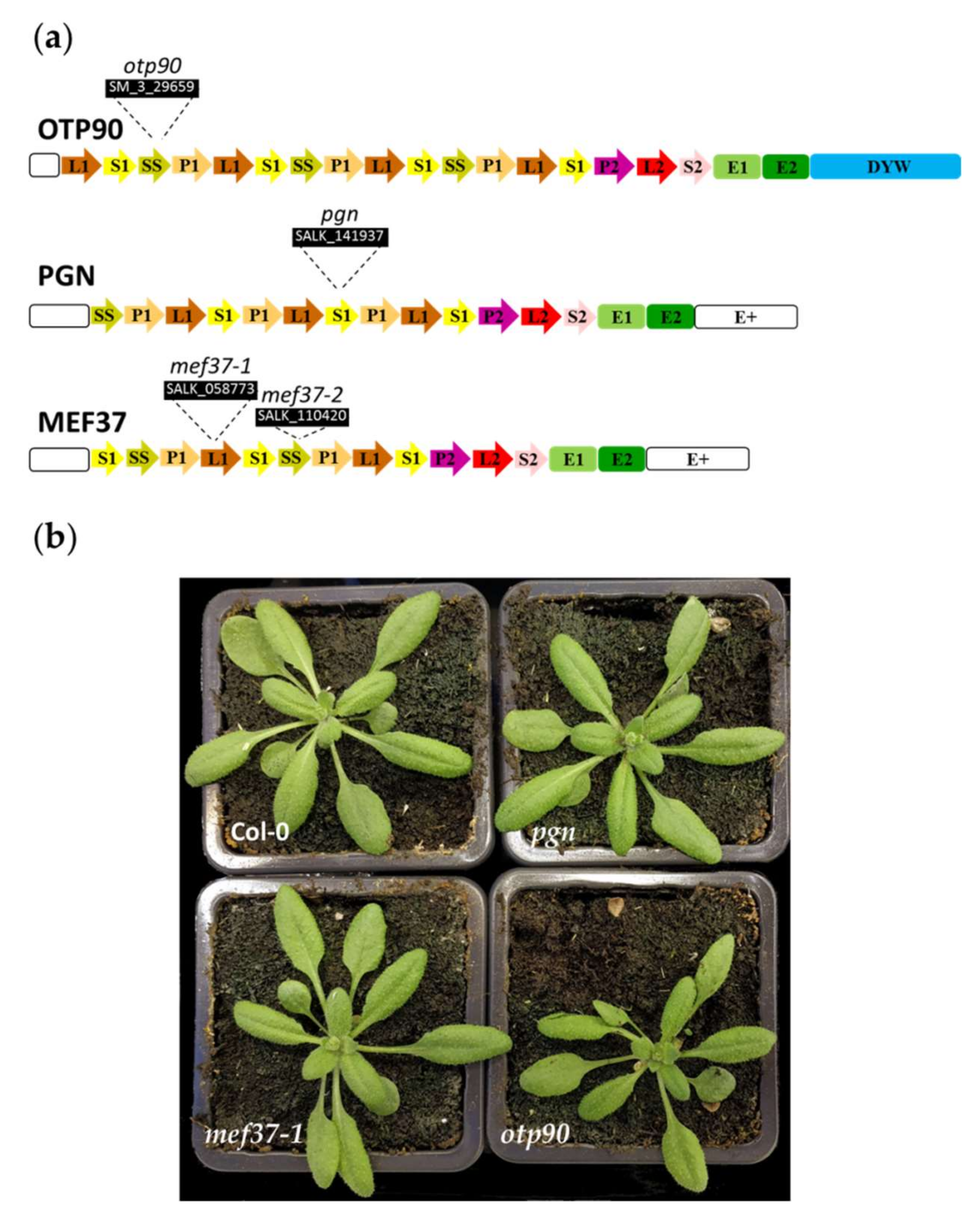

2.2. Characterization of AT1G56570 (PGN), AT5G08305 (MEF37) and AT1G25360 (OTP90)

2.3. pgn, mef37and otp90 Mutants Are Impaired in Mitochondrial C to U Editing

2.4. Using the dyw2 Editing Defects to Refine the PPR Code for PLS PPR Proteins

3. Discussion

3.1. OTP90, PGN and MEF37 Are Major Mitochondrial Editing Factors

3.2. OTP90, MEF37 and PGN Share Editing Sites with Several Other Editing Factors

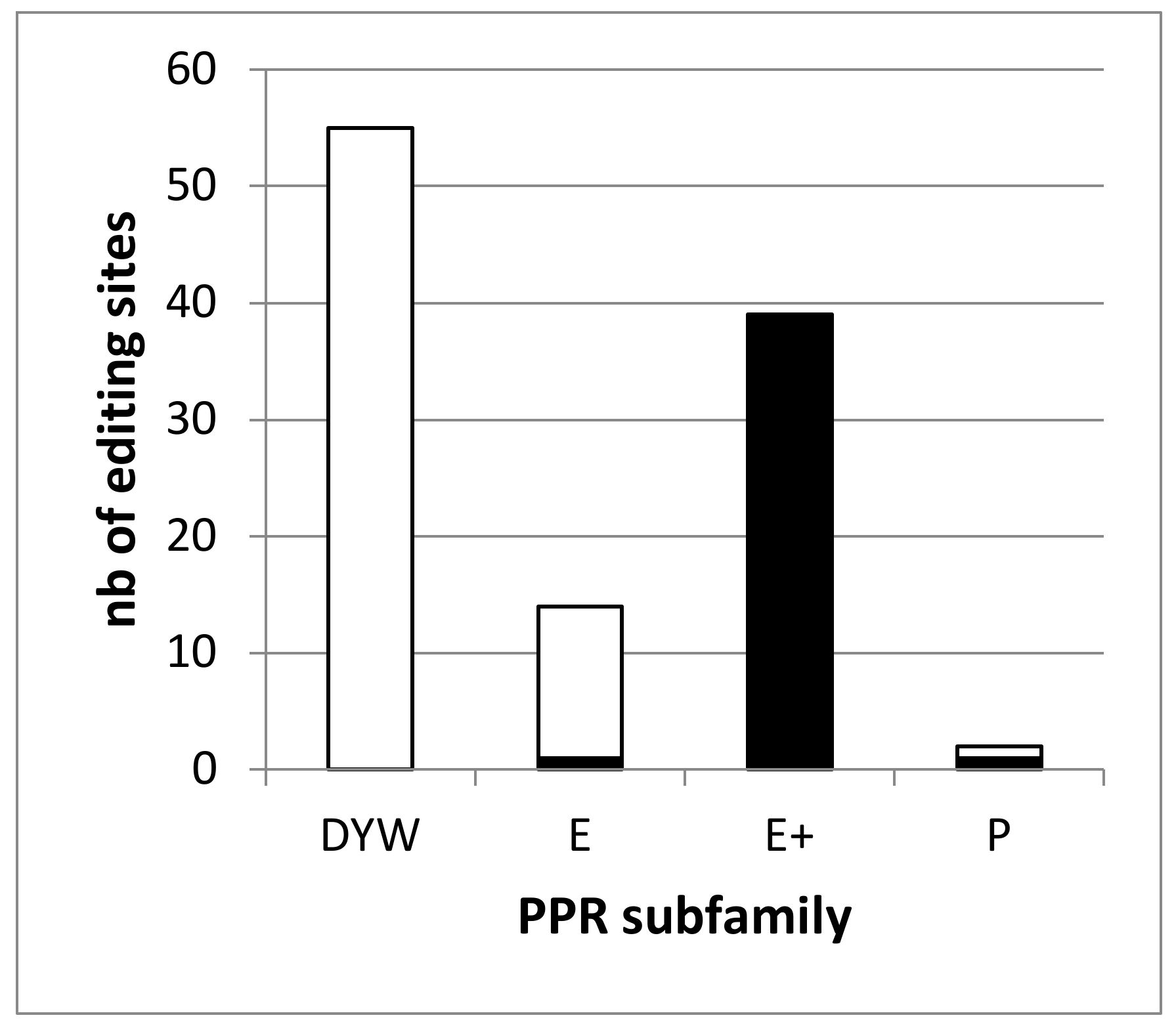

3.3. Specificity of DYW2 for E+ PPR Proteins

3.4. Limitations of the Code for PLS-Type PPR Proteins

4. Materials and Methods

4.1. Plant Material, Phenotype Characterization and Complementation Assay

4.2. RNA Analysis

4.3. Direct cDNA Sequence Analysis.

4.4. Subcellular Protein Localization

4.5. Yeast Two Hybrid Assays

4.6. In Vivo Protein–Protein Interaction Assay with BiFC Analysis

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Conflicts of Interest

Data Accessibility

References

- Small, I.D.; Rackham, O.; Filipovska, A. Organelle transcriptomes: Products of a deconstructed genome. Curr. Opin. Microbiol. 2013, 16, 652–658. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gualberto, J.M.; Lamattina, L.; Bonnard, G.; Weil, J.H.; Grienenberger, J.M. RNA editing in wheat mitochondria results in the conservation of protein sequences. Nature 1989, 341, 660–662. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoch, B.; Maier, R.M.; Appel, K.; Igloi, G.L.; Kössel, H. Editing of a chloroplast mRNA by creation of an initiation codon. Nature 1991, 353, 178–180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Edera, A.A.; Gandini, C.L.; Sanchez-Puerta, M.V. Towards a comprehensive picture of C-to-U RNA editing sites in angiosperm mitochondria. Plant Mol. Biol. 2018, 97, 215–231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Grewe, F.; Herres, S.; Viehöver, P.; Polsakiewicz, M.; Weisshaar, B.; Knoop, V. A unique transcriptome: 1782 positions of RNA editing alter 1406 codon identities in mitochondrial mRNAs of the lycophyte Isoetes engelmannii. Nucleic Acids Res. 2011, 39, 2890–2902. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Guillaumot, D.; Lopez-Obando, M.; Baudry, K.; Avon, A.; Rigaill, G.; Falcon De Longevialle, A.; Broche, B.; Takenaka, M.; Berthomé, R.; De Jaeger, G.; et al. Two interacting PPR proteins are major Arabidopsis editing factors in plastid and mitochondria. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2017, 114, 8877–8882. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Small, I.D.; Schallenberg-Rüdinger, M.; Takenaka, M.; Mireau, H.; Ostersetzer-Biran, O. Plant organellar RNA editing: What 30 years of research has revealed. Plant J. 2019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kotera, E.; Tasaka, M.; Shikanai, T. A pentatricopeptide repeat protein is essential for RNA editing in chloroplasts. Nature 2005, 433, 326–330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Small, I.D.; Peeters, N. The PPR motif—A TPR-related motif prevalent in plant organellar proteins. Trends Biochem. Sci. 2000, 25, 45–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Colcombet, J.; Lopez-Obando, M.; Heurtevin, L.; Bernard, C.; Martin, K.; Berthomé, R.; Lurin, C. Systematic study of subcellular localization of Arabidopsis PPR proteins confirms a massive targeting to organelles. RNA Biol. 2013, 10, 1557–1575. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yin, P.; Li, Q.; Yan, C.; Liu, Y.; Liu, J.; Yu, F.; Wang, Z.; Long, J.; He, J.; Wang, H.-W.; et al. Structural basis for the modular recognition of single-stranded RNA by PPR proteins. Nature 2013, 504, 168–171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shen, C.; Wang, X.; Liu, Y.; Li, Q.; Yang, Z.; Yan, N.; Zou, T.; Yin, P. Specific RNA recognition by designer pentatricopeptide repeat protein. Mol. Plant 2015, 8, 667–670. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kindgren, P.; Yap, A.; Bond, C.S.; Small, I. Predictable alteration of sequence recognition by RNA editing factors from Arabidopsis. Plant Cell 2015, 27, 403–416. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Barkan, A.; Rojas, M.; Fujii, S.; Yap, A.; Chong, Y.S.; Bond, C.S.; Small, I. A Combinatorial Amino Acid Code for RNA Recognition by Pentatricopeptide Repeat Proteins. PLoS Genet. 2012, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Takenaka, M.; Zehrmann, A.; Brennicke, A.; Graichen, K. Improved computational target site prediction for pentatricopeptide repeat RNA editing factors. PLoS ONE 2013, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, J.; Yao, Y.; Hong, S.; Yang, Y.; Shen, C.; Zhang, Q.; Zhang, D.; Zou, T.; Yin, P. Delineation of pentatricopeptide repeat codes for target RNA prediction. Nucleic Acids Res. 2019, 47, 3728–3738. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kobayashi, T.; Yagi, Y.; Nakamura, T. Comprehensive Prediction of Target RNA Editing Sites for PLS-Class PPR Proteins in Arabidopsis thaliana. Plant Cell Physiol. 2019, 60, 862–874. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bentolila, S.; Heller, W.P.; Sun, T.; Babina, A.M.; Friso, G.; Van Wijk, K.J.; Hanson, M.R. RIP1, a member of an Arabidopsis protein family, interacts with the protein RARE1 and broadly affects RNA editing. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2012, 109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bentolila, S.; Oh, J.; Hanson, M.R.; Bukowski, R. Comprehensive High-Resolution Analysis of the Role of an Arabidopsis Gene Family in RNA Editing. PLoS Genet. 2013, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Takenaka, M.; Zehrmann, A.; Verbitskiy, D.; Kugelmann, M.; Hartel, B.; Brennicke, A. Multiple organellar RNA editing factor (MORF) family proteins are required for RNA editing in mitochondria and plastids of plants. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2012, 109, 5104–5109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bayer-Császár, E.; Haag, S.; Jörg, A.; Glass, F.; Härtel, B.; Obata, T.; Meyer, E.H.; Brennicke, A.; Takenaka, M. The conserved domain in MORF proteins has distinct affinities to the PPR and E elements in PPR RNA editing factors. Biochim. Biophys. Acta Gene Regul. Mech. 2017, 1860, 813–828. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, J.; Zhang, Q.; Guan, Z.; Wang, Q.; Li, L.; Ruan, F.; Lin, R.; Zou, T.; Yin, P. MORF9 increases the RNA-binding activity of PLS-type pentatricopeptide repeat protein in plastid RNA editing. Nat. Plants 2017, 3, 17037. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lurin, C.; Andrés, C.; Aubourg, S.; Bellaoui, M.; Bitton, F.; Bruyère, C.; Caboche, M.; Debast, C.; Gualberto, J.; Hoffmann, B.; et al. Genome-wide analysis of Arabidopsis pentatricopeptide repeat proteins reveals their essential role in organelle biogenesis. Plant Cell 2004, 16, 2089–2103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cheng, S.; Gutmann, B.; Zhong, X.; Ye, Y.; Fisher, M.F.; Bai, F.; Castleden, I.; Song, Y.; Song, B.; Huang, J.; et al. Redefining the structural motifs that determine RNA binding and RNA editing by pentatricopeptide repeat proteins in land plants. Plant J. 2016, 85, 532–547. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Waltz, F.; Nguyen, T.T.; Arrivé, M.; Bochler, A.; Chicher, J.; Hammann, P.; Kuhn, L.; Quadrado, M.; Mireau, H.; Hashem, Y.; et al. Small is big in Arabidopsis mitochondrial ribosome. Nat. Plants 2019, 5, 106–117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Barkan, A.; Small, I. Pentatricopeptide Repeat Proteins in Plants. Annu. Rev. Plant Biol. 2014, 65, 415–442. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Salone, V.; Rüdinger, M.; Polsakiewicz, M.; Hoffmann, B.; Groth-Malonek, M.; Szurek, B.; Small, I.; Knoop, V.; Lurin, C. A hypothesis on the identification of the editing enzyme in plant organelles. FEBS Lett. 2007, 581, 4132–4138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boussardon, C.; Avon, A.; Kindgren, P.; Bond, C.S.; Challenor, M.; Lurin, C.; Small, I. The cytidine deaminase signature HxE(x)nCxxC of DYW1 binds zinc and is necessary for RNA editing of ndhD-1. New Phytol. 2014, 203, 1090–1095. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wagoner, J.A.; Sun, T.; Lin, L.; Hanson, M.R. Cytidine deaminase motifs within the DYW domain of two pentatricopeptide repeat-containing proteins are required for site-specific chloroplast RNA editing. J. Biol. Chem. 2015, 290, 2957–2968. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oldenkott, B.; Yang, Y.; Lesch, E.; Knoop, V.; Schallenberg-Rüdinger, M. Plant-type pentatricopeptide repeat proteins with a DYW domain drive C-to-U RNA editing in Escherichia coli. Commun. Biol. 2019, 2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boussardon, C.; Salone, V.; Avon, A.; Berthomé, R.; Hammani, K.; Okuda, K.; Shikanai, T.; Small, I.; Lurina, C. Two interacting proteins are necessary for the editing of the ndhD-1 site in Arabidopsis plastids. Plant Cell 2012, 24, 3684–3694. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Andrés-Colás, N.; Zhu, Q.; Takenaka, M.; De Rybel, B.; Weijers, D.; Van Der Straeten, D. Multiple PPR protein interactions are involved in the RNA editing system in Arabidopsis mitochondria and plastids. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2017, 114, 8883–8888. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Takenaka, M.; Verbitskiy, D.; Zehrmann, A.; Brennicke, A. Reverse genetic screening identifies five E-class PPR proteins involved in RNA editing in mitochondria of Arabidopsis thaliana. J. Biol. Chem. 2010, 285, 27122–27129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Leu, K.-C.; Hsieh, M.-H.; Wang, H.-J.; Hsieh, H.-L.; Jauh, G.-Y. Distinct role of Arabidopsis mitochondrial P-type pentatricopeptide repeat protein-modulating editing protein, PPME, in nad1 RNA editing. RNA Biol. 2016, 13, 593–604. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Laluk, K.; Abuqamar, S.; Mengiste, T. The Arabidopsis mitochondria-localized pentatricopeptide repeat protein PGN functions in defense against necrotrophic fungi and abiotic stress tolerance. Plant Physiol. 2011, 156, 2053–2068. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hooper, C.M.; Castleden, I.R.; Tanz, S.K.; Aryamanesh, N.; Millar, A.H. SUBA4: The interactive data analysis centre for Arabidopsis subcellular protein locations. Nucleic Acids Res. 2017, 45, D1064–D1074. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gutmann, B.; Royan, S.; Schallenberg-Rüdinger, M.; Lenz, H.; Castleden, I.R.; McDowell, R.; Vacher, M.A.; Tonti-Filippini, J.; Bond, C.S.; Knoop, V.; et al. The expansion and diversification of pentatricopeptide repeat RNA editing factors in plants. Mol. Plant 2019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hashimoto, M.; Endo, T.; Peltier, G.; Tasaka, M.; Shikanai, T. A nucleus-encoded factor, CRR2, is essential for the expression of chloroplast ndhB in Arabidopsis. Plant J. 2003, 36, 541–549. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hammani, K.; Des Francs-Small, C.C.; Takenaka, M.; Tanz, S.K.; Okuda, K.; Shikanai, T.; Brennicke, A.; Small, I. The pentatricopeptide repeat protein OTP87 is essential for RNA editing of nad7 and atp1 transcripts in Arabidopsis mitochondria. J. Biol. Chem. 2011, 286, 21361–21371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Glass, F.; Härtel, B.; Zehrmann, A.; Verbitskiy, D.; Takenaka, M. MEF13 requires MORF3 and MORF8 for RNA editing at eight targets in mitochondrial mRNAs in Arabidopsis thaliana. Mol. Plant 2015, 8, 1466–1477. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tasaki, E.; Hattori, M.; Sugita, M. The moss pentatricopeptide repeat protein with a DYW domain is responsible for RNA editing of mitochondrial ccmFc transcript. Plant J. 2010, 62, 560–570. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ichinose, M.; Sugita, C.; Yagi, Y.; Nakamura, T.; Sugita, M. Two DYW subclass PPR proteins are involved in RNA editing of ccmFc and atp9 transcripts in the moss Physcomitrella patens: First complete set of PPR editing factors in plant mitochondria. Plant Cell Physiol. 2013, 54, 1907–1916. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Diaz, M.F.; Bentolila, S.; Hayes, M.L.; Hanson, M.R.; Mulligan, R.M. A protein with an unusually short PPR domain, MEF8, affects editing at over 60 Arabidopsis mitochondrial C targets of RNA editing. Plant J. 2017, 92, 638–649. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yagi, Y.; Hayashi, S.; Kobayashi, K.; Hirayama, T.; Nakamura, T. Elucidation of the RNA recognition code for pentatricopeptide repeat proteins involved in organelle RNA editing in plants. PLoS ONE 2013, 8, e57286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Okuda, K.; Shoki, H.; Arai, M.; Shikanai, T.; Small, I.; Nakamura, T. Quantitative analysis of motifs contributing to the interaction between PLS-subfamily members and their target RNA sequences in plastid RNA editing. Plant J. 2014, 80, 870–882. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chateigner-Boutin, A.-L.; des Francs-Small, C.C.; Delannoy, E.; Kahlau, S.; Tanz, S.K.S.K.; de Longevialle, A.F.; Fujii, S.; Small, I. OTP70 is a pentatricopeptide repeat protein of the E subgroup involved in splicing of the plastid transcript rpoC1. Plant J. 2011, 65, 532–542. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hammani, K.; Takenaka, M.; Miranda, R.; Barkan, A. A PPR protein in the PLS subfamily stabilizes the 5’-end of processed rpl16 mRNAs in maize chloroplasts. Nucleic Acids Res. 2016, 44, 4278–4288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ruwe, H.; Gutmann, B.; Schmitz-Linneweber, C.; Small, I.; Kindgren, P. The E domain of CRR2 participates in sequence-specific recognition of RNA in plastids. New Phytol. 2019, 222, 218–229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McDermott, J.J.; Civic, B.; Barkan, A. Effects of RNA structure and salt concentration on the affinity and kinetics of interactions between pentatricopeptide repeat proteins and their RNA ligands. PLoS ONE 2018, 13, e0209713. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miranda, R.G.; Rojas, M.; Montgomery, M.P.; Gribbin, K.P.; Barkan, A. RNA-binding specificity landscape of the pentatricopeptide repeat protein PPR10. RNA 2017, 23, 586–599. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Williams-Carrier, R.; Kroeger, T.; Barkan, A. Sequence-specific binding of a chloroplast pentatricopeptide repeat protein to its native group II intron ligand. RNA 2008, 14, 1930–1941. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Prikryl, J.; Rojas, M.; Schuster, G.; Barkan, A. Mechanism of RNA stabilization and translational activation by a pentatricopeptide repeat protein. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2011, 108, 415–420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Armengaud, P.; Zambaux, K.; Hills, A.; Sulpice, R.; Pattison, R.J.; Blatt, M.R.; Amtmann, A. EZ-Rhizo: Integrated software for the fast and accurate measurement of root system architecture. Plant J. 2009, 57, 945–956. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nakagawa, T.; Suzuki, T.; Murata, S.; Nakamura, S.; Hino, T.; Maeo, K.; Tabata, R.; Kawai, T.; Tanaka, K.; Niwa, Y.; et al. Improved gateway binary vectors: High-performance vectors for creation of fusion constructs in transgenic analysis of plants. Biosci. Biotechnol. Biochem. 2007, 71, 2095–2100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nakagawa, T.; Kurose, T.; Hino, T.; Tanaka, K.; Kawamukai, M.; Niwa, Y.; Toyooka, K.; Matsuoka, K.; Jinbo, T.; Kimura, T. Development of series of gateway binary vectors, pGWBs, for realizing efficient construction of fusion genes for plant transformation. J. Biosci. Bioeng. 2007, 104, 34–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ishizaki, K.; Nishihama, R.; Ueda, M.; Inoue, K.; Ishida, S.; Nishimura, Y.; Shikanai, T.; Kohchi, T. Development of gateway binary vector series with four different selection markers for the liverwort marchantia polymorpha. PLoS ONE 2015, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Malbert, B.; Rigaill, G.; Brunaud, V.; Lurin, C.; Delannoy, E. Bioinformatic Analysis of Chloroplast Gene Expression and RNA Posttranscriptional Maturations Using RNA Sequencing. In Plastids; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2018; Volume 1829. [Google Scholar]

- Dobin, A.; Davis, C.A.; Schlesinger, F.; Drenkow, J.; Zaleski, C.; Jha, S.; Batut, P.; Chaisson, M.; Gingeras, T.R. STAR: Ultrafast universal RNA-seq aligner. Bioinformatics 2013, 29, 15–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Curtis, M.D.; Grossniklaus, U. A Gateway Cloning Vector Set for High-Throughput Functional Analysis of Genes in Planta. Plant Physiol. 2003, 133, 462–469. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Mutant | Position 1 | Site Name 2 | WT 3 | Mutant 4 | ΔEE 5 | Padj. 6 | dyw27 | ΔEE dyw2 8 | Padj. dyw2 9 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| mef37-1 | M17869 | ccmB_566 | 90.5% | 6.6% | −93% | 0.000 | 13% | −86% | 0.000 |

| M17884 | ccmB_551 | 96.4% | 1.4% | −99% | 0.000 | 4% | −96% | 0.000 | |

| M23217 | rps3_1470 | 72.4% | 0.0% | −100% | 0.000 | 1% | −99% | 0.000 | |

| M49473 | atp6_71 | 0.6% | 0.0% | −100% | 0.002 | ND | ND | ND | |

| M189896 | ccmFc_414 | 3.5% | 0.0% | −100% | 0.002 | 0% | −98% | 0.000 | |

| M215126 | nad4_437 | 98.1% | 48.5% | −51% | 0.000 | 71% | −28% | 0.000 | |

| M219378 | mttb_387 | 42.8% | 5.7% | −87% | 0.000 | 1% | −96% | 0.000 | |

| M308476 | ccmC_179 | 95.7% | 0.9% | −99% | 0.000 | 2% | −97% | 0.000 | |

| M362007 | nad4L_trailer_72 | 90.2% | 1.8% | −98% | 0.000 | 2% | −97% | 0.000 | |

| M362343 | atp4_138 | 92.1% | 1.3% | −99% | 0.000 | 5% | −95% | 0.000 | |

| M362349 | atp4_144 | 7.7% | 27.3% | 253% | 0.000 | 46% | 331% | 0.000 | |

| pgn | M8348 | cox2_742 | 99.6% | 0.0% | −100% | 0.000 | 11% | −89% | 0.000 |

| M165765 | nad6_leader_-73 | 84.4% | 0.2% | −100% | 0.000 | 3% | −97% | 0.000 | |

| otp90 | M17839 | ccmB_596 | 81.8% | 23.0% | −72% | 0.000 | 93% | 11% | 0.000 |

| M18355 | ccmB_80 | 83.9% | 5.9% | −93% | 0.000 | 89% | 12% | 0.000 | |

| M59321 | nad1_500 | 73.9% | 0.0% | −100% | 0.000 | 87% | −3% | 1.000 | |

| M191687 | ccmFc_1246 | 67.6% | 12.7% | −81% | 0,000 | 77% | 26% | 0.000 | |

| M209816 | nad4_194 | 9.6% | 14.7% | 54% | 0.027 | 2% | −72% | 0.000 | |

| M209909 | nad4_111 | 68.9% | 84.6% | 23% | 0.000 | 92% | 5% | 0.000 | |

| M219657 | mttb_108 | 4.8% | 0.2% | −95% | 0.006 | 0% | −97% | 0.000 | |

| M219668 | mttb_97 | 81.6% | 1.9% | −98% | 0.000 | 77% | −4% | 1.000 | |

| M233590 | matR_1950 | 3.1% | 7.8% | 149% | 0.049 | 0% | −94% | 0.000 | |

| M308481 | ccmC_184 | 83.3% | 5.6% | −93% | 0.000 | 87% | 4% | 1.000 | |

| M329728 | cox3_trailer_248 | 0.6% | 0.0% | −92% | 0.000 | 2% | 257% | 0.000 | |

| M362007 | nad4L_trailer_72 | 86.9% | 92.6% | 7% | 0.000 | 2% | −97% | 0.000 |

| Mutant | Position | Site Name | WT 1 | Mutant 2 | Compl 3 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| mef37-2 | M17869 | ccmB_566 | 100% | <5% | 100% |

| M17884 | ccmB_551 | 100% | <5% | 100% | |

| M23217 | rps3_1470 | 85% | <5% | 100% | |

| M215126 | nad4_437 | 100% | 70% | 100% | |

| M219378 | mttb_387 | 40% | <5% | 50% | |

| M308476 | ccmC_179 | 100% | <5% | 100% | |

| M362343 | atp4_138 | 100% | <5% | 100% | |

| M362349 | atp4_144 | <5% | 35% | <5% | |

| pgn | M8348 | cox2_742 | 85–90% | 40–45% | 85–90% |

| M165765 | nad6_leader_-73 | 85–90% | 15% | 85–90% | |

| otp90 | M17839 | ccmB_596 | 100% | 30-35% | 100% |

| M18355 | ccmB_80 | 85–90% | <5% | 75% | |

| M59321 | nad1_500 | 100% | <5% | 100% | |

| M191687 | ccmFc_1246 | 55% | 15% | 90% | |

| M219668 | mttb_97 | 80% | <5% | 80–85%. | |

| M308481 | ccmC_184 | 70% | <5% | 85% |

| PPR | Position 1 | Site Name 2 | Rank 3 | Rank DYW2 4 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| AEF1 | M26928 | nad5_1580 | 1 | 1 |

| AEF1 | P12707 | atpF_92 | 18 | 6 |

| AHG11 | M215187 | nad4_376 | 1 | 1 |

| CLB19 | P69942 | clpP_559 | 2 | 2 |

| CLB19 | P78691 | rpoA_200 | 5 | 5 |

| COD1 | M6961 | cox2_698 | 6 | 2 |

| COD1 | M6516 | cox2_253 | 8 | 4 |

| COD1 | M209881 | nad4_1129 | 34 | 14 |

| CRR21 | P116785 | ndhD_383 | 1 | 1 |

| CWM1 | M235780 | nad5_598 | 2 | 1 |

| CWM1 | M18007 | ccmB_428 | 4 | 2 |

| CWM1 | M308760 | ccmC_463 | 12 | 6 |

| GRS1 | M165940 | nad6_103 | 1 | 1 |

| GRS1 | M361691 | nad4L_55 | 2 | 2 |

| GRS1 | M160356 | rps4_377 | 33 | 14 |

| GRS1 | M83057 | nad1_265 | 109 | 41 |

| MEF12 | M235556 | nad5_374 | 1 | 1 |

| MEF13 | M189532 | ccmFc_50 | 1 | 1 |

| MEF13 | M189897 | ccmFc_415 | 2 | 2 |

| MEF13 | M161857 | nad2_59 | 3 | 3 |

| MEF13 | M215405 | nad4_158 | 4 | 4 |

| MEF13 | M28242 | nad5_1916 | 5 | 5 |

| MEF13 | M330460 | cox3_314 | 6 | 6 |

| MEF13 | M27013 | nad5_1665 | 47 | 21 |

| MEF21 | M330517 | cox3_257 | 1 | 1 |

| MEF25 | M83014 | nad1_308 | 12 | 7 |

| MEF37 | M215126 | nad4_437 | 1 | 1 |

| MEF37 | M17884 | ccmB_551 | 3 | 2 |

| MEF37 | M17869 | ccmB_566 | 12 | 5 |

| MEF37 | M23217 | rps3_1470 | 17 | 8 |

| MEF37 | M308476 | ccmC_179 | 46 | 22 |

| MEF37 | M362343 | atp4_138 | 57 | 24 |

| MEF37 | M219378 | mttB_387 | 70 | 31 |

| OTP72 | M23724 | rpl16_440 | 1 | 1 |

| OTP80 | P86055 | rpl23_89 | 1 | 1 |

| PGN | M8348 | cox2_742 | 1 | 1 |

| PGN | M165765 | nad6_leader_-73 | 2 | 2 |

| SLG1 | M288290 | nad3_250 | 1 | 1 |

| SLO1 | M215114 | nad4_449 | 1 | 1 |

| SLO1 | M24992 | nad9_328 | 2 | 2 |

| SLO2 | M241512 | nad7_739 | 2 | 1 |

| SLO2 | M219621 | mttB_144 | 4 | 2 |

| SLO2 | M361746 | nad4L_110 | 76 | 23 |

| SLO2 | M219099 | mttB_666 | 139 | 47 |

| SLO2 | M219620 | mttB_145 | 177 | 65 |

© 2020 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Malbert, B.; Burger, M.; Lopez-Obando, M.; Baudry, K.; Launay-Avon, A.; Härtel, B.; Verbitskiy, D.; Jörg, A.; Berthomé, R.; Lurin, C.; et al. The Analysis of the Editing Defects in the dyw2 Mutant Provides New Clues for the Prediction of RNA Targets of Arabidopsis E+-Class PPR Proteins. Plants 2020, 9, 280. https://doi.org/10.3390/plants9020280

Malbert B, Burger M, Lopez-Obando M, Baudry K, Launay-Avon A, Härtel B, Verbitskiy D, Jörg A, Berthomé R, Lurin C, et al. The Analysis of the Editing Defects in the dyw2 Mutant Provides New Clues for the Prediction of RNA Targets of Arabidopsis E+-Class PPR Proteins. Plants. 2020; 9(2):280. https://doi.org/10.3390/plants9020280

Chicago/Turabian StyleMalbert, Bastien, Matthias Burger, Mauricio Lopez-Obando, Kevin Baudry, Alexandra Launay-Avon, Barbara Härtel, Daniil Verbitskiy, Anja Jörg, Richard Berthomé, Claire Lurin, and et al. 2020. "The Analysis of the Editing Defects in the dyw2 Mutant Provides New Clues for the Prediction of RNA Targets of Arabidopsis E+-Class PPR Proteins" Plants 9, no. 2: 280. https://doi.org/10.3390/plants9020280

APA StyleMalbert, B., Burger, M., Lopez-Obando, M., Baudry, K., Launay-Avon, A., Härtel, B., Verbitskiy, D., Jörg, A., Berthomé, R., Lurin, C., Takenaka, M., & Delannoy, E. (2020). The Analysis of the Editing Defects in the dyw2 Mutant Provides New Clues for the Prediction of RNA Targets of Arabidopsis E+-Class PPR Proteins. Plants, 9(2), 280. https://doi.org/10.3390/plants9020280