Residual Dynamics of Fluopyram and Its Compound Formulations in Pinus massoniana and Their Efficacy in Preventing Pine Wilt Disease

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Results

2.1. Effects of Trunk Injection Agents on Pine Xylem

2.2. Transportability of Different Trunk Injection Agents in Trees

2.3. Vertical Distribution of Different Trunk Injection Agents in Pine Trees

2.4. Residual Dynamics of Different Trunk-Injection Agents in Pine Trees

2.5. Efficiency of Different Trunk-Injection Agents Against PWD

3. Discussion

4. Materials and Methods

4.1. PWN Material and Cultivation

4.2. Test Agent

4.3. Test Plots

4.4. Effects of Different Trunk-Injection Agents on the Growth of Pine Trees

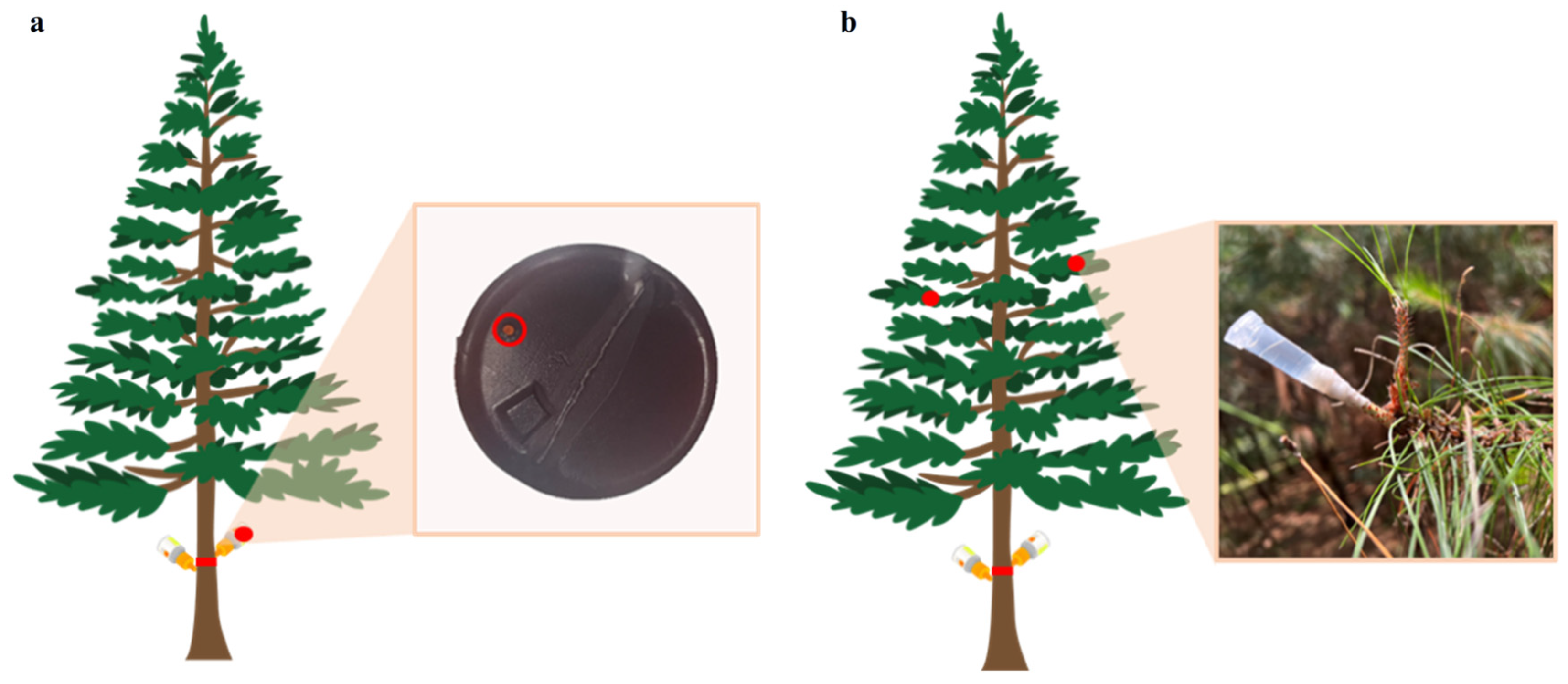

4.5. Distribution and Residue Dynamics of Different Trunk-Injection Agents in Trees

4.6. Processing and Extraction of Tree Samples

4.7. LC-MS Analysis

4.8. Efficacy of Different Trunk-Injection Agents Against PWD

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Feng, Y.-Q.; Rui, L.; Wang, X.-Y.; Wu, X.-Q. Adaptation of pine wood nematode, Bursaphelenchus xylophilus, early in its interaction with two Pinus species that differ in resistance. J. For. Res. 2022, 33, 1391–1400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, Q.-W.; Zhang, X.-J.; Li, J.-X.; Ren, J.-R.; Ren, L.-L.; Luo, Y.-Q. Pine wilt disease in northeast and northwest China: A comprehensive risk review. Forests 2023, 14, 174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, L.; Xu, S.-Y.; Xu, C.-M.; Lu, H.-B.; Zhang, Z.-Q.; Zhang, D.-X.; Mu, W.; Liu, F. Effects of trans-2-hexenal on reproduction, growth and behaviour and efficacy against the pine wood nematode, Bursaphelenchus xylophilus. Pest Manag. Sci. 2017, 73, 888–895. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yang, Z.-Q.; Wang, X.-Y.; Zhang, Y.-N. Recent advances in biological control of important native and invasive forest pests in China. Biol. Control 2014, 68, 117–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, F.; Guo, K.; Chen, A.-L.; Chen, S.-N.; Lin, H.-P.; Zhou, X. Transcriptomic profiling of effects of emamectin benzoate on the pine wood nematode Bursaphelenchus xylophilus. Pest Manag. Sci. 2020, 76, 747–757. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, W.-J.; Wu, X.-Q.; Ye, J.-R.; Li, C.-Q.; Hu, L.-J.; Rui, L.; Zhang, Y.; Shi, X.-F.; Wang, L. Toxicity of an emamectin benzoate microemulsion against Bursaphelenchus xylophilus and its effect on the prevention of pine wilt disease. Forests 2023, 14, 1476. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiang, F.; Liu, Y.-Z.; Ye, J.-R.; Zhang, W.-J. Study on the control of Bursaphelenchus xylophilus by trunk-injection with three kinds of agents. J. Nanjing For. Univ. (Nat. Sci. Ed.) 2025, 49, 95–101. [Google Scholar]

- Takai, K.; Suzuki, T.; Kawazu, K. Distribution and persistence of emamectin benzoate at efficacious concentrations in pine tissues after injection of a liquid formulation. Pest Manag. Sci. 2004, 60, 42–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jia, J.-W. Primary Research on Prevention Mechanism of Emamectin Benzoate Trunk Injection Against Pine Wilt Disease. Master’s Thesis, Zhejiang Agriculture and Forestry University, Hangzhou, China, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Su, C.-Y.; Ji, Y.-C.; Liu, S.-S.; Gao, S.-K.; Cao, S.-H.; Xu, X.-Y.; Zhou, C.-G.; Liu, Y.-C. Fluorescence-labeled abamectin nanopesticide for comprehensive control of pine wood nematode and Monochamus alternatus Hope. ACS Sustain. Chem. Eng. 2020, 8, 16555–16564. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cabrera, J.A.; Menjivar, R.D.; Dababat, A.E.F.A.; Sikora, R.A. Properties and nematicide performance of avermectins. J. Phytopathol. 2013, 161, 65–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shen, J.; Zhang, C.; Zhang, S.-Y.; Chen, F.; Pei, F.; Zhou, S.; Lin, H.-P. Screening, isolation and mechanism of a nematicidal extract from actinomycetes against the pine wood nematode Bursaphelenchus xylophilus. Heliyon 2022, 8, e11713. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Claassen, B.J.; Wolfenbarger, S.N.; Gent, D.H. Fungicide physical mode of action: Impacts on suppression of hop powdery mildew. Plant Dis. 2022, 106, 1244–1252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Veloukas, T.; Karaoglanidis, G.S. Biological activity of the succinate dehydrogenase inhibitor fluopyram against Botrytis cinerea and fungal baseline sensitivity. Pest Manag. Sci. 2012, 68, 858–864. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, J.; Hu, B.-Y.; Gao, X.-H.; Cui, Y.-Y.; Qian, L.; Xu, J.-Q.; Liu, S.-M. In vitro determination of the sensitivity of Fusarium graminearum to fungicide fluopyram and investigation of the resistance mechanism. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2025, 73, 4001–4011. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.; Sun, S.-Y.; Guo, Y.; Ren, F.-H.; Sheng, G.-L.; Wu, H.; Zhao, H.-Q.; Cai, Y.-Q.; Gu, C.-Y.; Duan, Y.-B. Risk assessment and resistant mechanism of Fusarium graminearum to fluopyram. Pestic. Biochem. Physiol. 2025, 212, 106449. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schleker, A.S.S.; Rist, M.; Matera, C.; Damijonaitis, A.; Collienne, U.; Matsuoka, K.; Habash, S.S.; Twelker, K.; Gutbrod, O.; Saalwächter, C.; et al. Author correction: Mode of action of fluopyram in plant-parasitic nematodes. Sci. Rep. 2023, 13, 13748. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei, P.; Liu, Y.-A.; Li, W.-Z.; Qian, Y.; Nie, Y.-X.; Kim, D.; Wang, M.-C. Metabolic and dynamic profiling for risk assessment of fluopyram, a typical phenylamide fungicide widely applied in vegetable ecosystem. Sci. Rep. 2016, 7, 33898. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Avenot, H.F.; Thomas, A.; Gitaitis, R.D.; Langston, D.B., Jr.; Stevenson, K.L. Molecular characterization of boscalid and penthiopyrad resistant isolates of didymella bryoniae and assessment of their sensitivity to fluopyram. Pest Manag. Sci. 2012, 68, 645–651. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sierotzki, H.; Scalliet, G. A review of current knowledge of resistance aspects for the next generation succinate dehydrogenase inhibitor fungicides. Phytopathology 2013, 103, 880–887. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ji, X.-X.; Li, J.-J.; Dong, B.; Zhang, H.; Zhang, S.-A.; Qiao, K. Evaluation of fluopyram for southern root-knot nematode management in tomato production in China. Crop Prot. 2019, 122, 84–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Faske, T.R.; Hurd, K. Sensitivity of Meloidogyne incognita and Rotylenchulus reniformis to fluopyram. J. Nematol. 2015, 47, 316–321. [Google Scholar]

- Oka, Y.; Saroya, Y. Effect of fluensulfone and fluopyram on the mobility and infection of second-stage juveniles of Meloidogyne incognita and M. javanica. Pest Manag. Sci. 2019, 75, 2095–2106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vosberg, S.K.; Marburger, D.A.; Smith, D.L.; Conley, S.P. Planting date and fluopyram seed treatment effect on soybean sudden death syndrome and seed yield. Agron. J. 2017, 109, 2570–2578. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, Y.-J.; Ma, J.-Y.; Sun, Y.-Z.; Carballar-Lejarazú, R.; Weng, M.-Q.; Shi, W.-C.; Wu, J.-Q.; Hu, X.; Wang, R.; Zhang, F.-P.; et al. Spatiotemporal dynamics of fluopyram trunk-injection in Pinus massoniana and its efficacy against pine wilt disease. Pest Manag. Sci. 2023, 79, 2230–2238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, Y.-J.; Ma, J.-Y.; Weng, M.-Q.; Carballar-Lejarazú, R.; Jiao, W.-L.; Wu, J.-Q.; Zhang, F.-P.; Wu, S.-Q. Control efficacy and persistence of fluopyram dust against pine wilt disease. J. For. Res. 2025, 36, 48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, G.-Y.; Lin, X.; Xu, S.-Y.; Liu, G.; Liu, Z.-Y.; Liu, F.; Mu, W. Efficacy of fluopyram as a candidate trunk-injection agent against Bursaphelenchus xylophilus. Eur. J. Plant Pathol. 2020, 157, 403–411. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rathod, P.H.; Shah, P.G.; Parmar, K.D.; Kalasariya, R.L. The fate of fluopyram in the soil-water-plant ecosystem: A review. Rev. Environ. Contam. Toxicol. 2022, 260, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shen, Y.-C.; Yang, H.-X. Development and characteristics of avermectin, an insecticide antibiotic. World Pestic. 1994, 3, 1–13. [Google Scholar]

- Ni, A.-S.; Wang, Y.-C.; Yang, D.; Sun, X.-S.; Ye, J.-R. Toxicity of a new compound medicament 2% avermectin. 6% fluopyram on Bursaphelenchus xylophilus. Sci. Silvae Sin. 2022, 58, 18–25. [Google Scholar]

- Cyndel, B.; François, L. Trunk injection of plant protection products to protect trees from pests and diseases. Crop Prot. 2019, 124, 104831. [Google Scholar]

- Yang, D.-C.; Hao, F.-F.; Zhang, Y.; Zhang, L.-P.; Luan, F.-G.; Zeng, J.-P. Effect of trunk injection of pesticides on physiological properties and protective enzymes in leaves of Pinus massoniana. J. Zhejiang For. Sci. Technol. 2018, 38, 27–32. [Google Scholar]

- Song, X.-S.; Deng, X.; Yu, W.-J.; Ma, X.-Q.; Shen, G.-T. Effect of tree trunk injection on the main physiological indexes of Pinus koraiensis needles. Jilin Agric. 2012, 272, 187–189. [Google Scholar]

- Li, C.-Q.; Ye, J.-R.; Zhang, W.-J.; Tang, Y.-W.; Shi, J.-W. Study on the control efficacy of trunk injection with emamectin benzoate microemulsion against pine wilt disease. China Plant Prot. 2022, 42, 16–19. [Google Scholar]

- Matsuura, K. Control of the pine wilt disease caused by pinewood nematodes [Bursaphelenchus xylophilus] with trunk-injection. Shokubutsu Boeki 1984, 38, 27–31. [Google Scholar]

- Huang, S.-F.; Wang, Z.-L.; Li, K.-S.; Zhang, D.-F.; Cao, P.-P. Distribution and variation dynamic of avermectin in jujube trees with trunk injection. For. Pest Dis. 2019, 38, 15–24. [Google Scholar]

- Ding, X.-L.; Ye, J.-R.; Lin, S.-X.; Wu, X.-Q.; Li, D.-W.; Nian, B. Deciphering the molecular variations of pine wood nematode Bursaphelenchus xylophilus with different virulence. PLoS ONE 2016, 11, e0156040. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, H.-B.; Wu, X.-Q.; Feng, Y.-Q.; Rui, L. Autophagy contributes to the feeding, reproduction, and mobility of Bursaphelenchus xylophilus at low temperatures. Acta Biochim. Biophys. Sin. 2019, 51, 864–872. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deng, H.-F.; Zhang, J.-Y.; Huang, K.; Zhong, T.-T.; Lin, L.-M. Determination of 105 pesticide residues in vegetables by QuEChERS-liquid chromatography-tandem mass spectrometry. Chin. J. Chromatogr. 2018, 36, 1211–1222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- GB/T 20769-2008; Determination of 450 Pesticides and Related Chemicals Residues in Fruits and Vegetables—LC-MS-MS Method. Standards Press of China: Beijing, China, 2008.

| Treatment | Injection Volume (mL) | Disease Severity Index (DSI) | Efficacy Against PWD | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 20 dpi | 40 dpi | 70 dpi | 270 dpi | |||

| CK | / | 8.33 | 58.33 | 83.33 | 100 | / |

| 5% FLU | 30 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 100 |

| ME | 60 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 100 |

| 5% EB | 30 | 0 | 16.67 | 50 | 66.67 | 33.33 |

| ME | 60 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 25 | 75 |

| 5% AVM | 30 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 16.67 | 83.33 |

| EC | 60 | 0 | 8.33 | 16.67 | 41.67 | 58.33 |

| 2% AVM + 6% FLU ME | 20 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 100 |

| 40 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 8.33 | 91.67 | |

| Treatment | Injection Volume (mL) | Disease Severity Index (DSI) | Efficacy Against PWD | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 60 dpi | 150 dpi | 220 dpi | |||

| 5% FLU ME | 30 | 16.67 | 33.33 | 50.00 | 25 |

| 60 | 8.33 | 33.33 | 50.00 | 25 | |

| 2% AVM + 6% FLU ME | 20 | 8.33 | 16.67 | 33.33 | 50 |

| 40 | 8.33 | 8.33 | 33.33 | 50 | |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Zhang, W.; Ni, A.; Zhang, J.; Sun, G.; Xiang, F.; Cheng, H.; Chen, T.; Ye, J. Residual Dynamics of Fluopyram and Its Compound Formulations in Pinus massoniana and Their Efficacy in Preventing Pine Wilt Disease. Plants 2026, 15, 302. https://doi.org/10.3390/plants15020302

Zhang W, Ni A, Zhang J, Sun G, Xiang F, Cheng H, Chen T, Ye J. Residual Dynamics of Fluopyram and Its Compound Formulations in Pinus massoniana and Their Efficacy in Preventing Pine Wilt Disease. Plants. 2026; 15(2):302. https://doi.org/10.3390/plants15020302

Chicago/Turabian StyleZhang, Wanjun, Anshun Ni, Jiao Zhang, Guohong Sun, Fan Xiang, Hao Cheng, Tingting Chen, and Jianren Ye. 2026. "Residual Dynamics of Fluopyram and Its Compound Formulations in Pinus massoniana and Their Efficacy in Preventing Pine Wilt Disease" Plants 15, no. 2: 302. https://doi.org/10.3390/plants15020302

APA StyleZhang, W., Ni, A., Zhang, J., Sun, G., Xiang, F., Cheng, H., Chen, T., & Ye, J. (2026). Residual Dynamics of Fluopyram and Its Compound Formulations in Pinus massoniana and Their Efficacy in Preventing Pine Wilt Disease. Plants, 15(2), 302. https://doi.org/10.3390/plants15020302